Chinese Studies 2012. Vol.1, No.3, 9-17 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/chnstd) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/chnstd.2012.13003 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 9 Theorizing Social Capital in Entrepreneurship—An Empirical Study in the Pearl River Delta, China Chiu-Yin Leung, Jiang Xu Department of Geography and Resource Management, The Chine s e U n i v e rsity of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Email: chiuyin@cuhk.edu.hk, jiangxu@cuhk.edu.hk Received October 8th, 2012; revised Novem ber 10th, 2012; accepted November 20th, 2012 In this paper, a social capital framework is brought in to explore the dynamics of Chinese entrepreneur- ship with respect to the social and institutional conditions in the post-reform China. Based on data col- lected from field interviews, it analyzes how enterprise social capital impacts upon the Hong Kong affili- ated manufacturing operations in the Pearl River Delta region. In regard to the “embeddedness-accessi- bility-use” framework, it is suggested that some trivial difference in the configuration of “guanxi (關係)” network could work specifically upon the divergent path of individual entrepreneurs during the early re- form period of the Pearl River Delta. As China enters another stage of marketization, firms that have been over-embedded and poorly-positioned in the network are now forcing their way out of the region. Alter- natively, recent institutional development across the border has boosted the significance of nurturing en- terprise social capital in the formal coordinating channels. The renewal in the stock of enterprise social capital is crucial in reconfiguring the network dynamics and entrepreneurial action to influence the future trajectory of industrial development in the Pearl River Delta. Keywords: Social Capital; Guanxi; Chinese Entrepreneurship Introduction The enquiries into the dynamics of entrepreneurship have long been a central task in economic geography. Departed from the rational or other somewhat “under-socialized” approaches, the social capital thesis emphasizes the embedding role of so- cial relations in shaping economic process. In this paper, a so- cial capital framework is brought in to explore the dynamics of Chinese entrepreneurship with respect to social and institutional changes in the reform period. It is argued that the re-configura- tion in the form and function of social network as embedded in the industrial context has led to tremendous shift in the opera- tion logic of Chinese entrepreneurs in the post-WTO era. Drawing from the ethnographic interviews of several Hong Kong entrepreneurs who engage in manufacturing activities in the Pearl River Delta (PRD), this paper studies the coupling of socio-institutional advancement and entrepreneurial action in the early reform and lately-restructuring periods respectively. The organization of this paper is as follows. Following this introduction, Section 2 reviews the conception of social capital and discusses its applicability in the context of Chinese entre- preneurship. An analytical framework is then put forth as an attempt to conceptualize the network dynamics in the captioned context in broad terms. Following that, Section 3 offers a few empirical cases for illustrating the significance of such dynam- ics on individual firms. Finally, the paper critically evaluates the potential of appropriating social capital perspective in studying Chinese entrepreneurship. Situating the Study of Social Capital in Chinese Entrepreneurship The notion of social capital arises as a critical component in modern society where its accumulation could boost economic prosperity and its suffering might derive ineffective governance. It is initially theorized by Bourdieu (1986: p. 249) as intangible asset of investment strategies “aimed at establishing or repro- ducing social relationships that are directly usable in the short or long term”. The scholarship is subsequently radiated across multiple disciplines, notably the fields of ethnic entrepreneur- ship and comparative institutionalism, in addressing the role of social relations for economic development at both the micro and macro level (Woolcock, 1998). Shortly put, social capital comprises a bunch of social assets that could affect certain economic actions and developmental outcome, which includes community network, cultural norm and practice, state-society relations, and institutional capacity (Taylor & Leonard, 2002 ). In the study of entrepreneurship, social capital is often per- ceived as the socially-embedded business networks that are accessible to and utilized by individual firms. Drawing on the embeddedness framework, a vast of literature has suggested the role of social network in channelizing inter-firm transactions and acquiring extra-firm resources in different situations (Tay- lor & Leonard, 2002). In particular, social capital forms simul- taneously as glue for network structure and functions as lubri- cate in network utilization, exemplifying its nature as both the medium and message of social relations (Chen, 2000). Taking a similar strand of view, the notion of “guanxi (關係)” is also widely articulated as an invaluable asset of network building and exploitation in achieving success in the transitional econ- omy (Hsing, 1996; Yang, 2002). Despite its magnitude and functions could vary by contexts, the importance of social net- works to individual entrepreneurs is almost acknowledged as a universal rule of law (Woolcock, 1998). Inevitably, the microscopic view of social capital outlined  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU above receives considerable challenges by opponent critics. The prominent charge comes from the plausible ambiguities in con- ceptualizing the form and function of social network, which sinks the notion into a tautology or logical circularity that the stock of the resource itself is only fixed in accordance to its eventual outcome arbitrarily (Lin, 2001). Likewise in the dis- course of guanxi in Chinese entrepreneurship, there is an ob- session of depreciating the significance of guanxi with its rele- vant change in stock neglected (e.g., please see Guthrie, 1998). Another accusation lies on the ground that social capital is not without its limit, and might even generate negative return at times. The debate on over-embeddedness is then brought to the scene, which suggests that too much closely-knitted ties and obligations within a preexisting community accumulated over time could lead to devastating effects and inhibit sustained growth (Woolcock, 1998). Alternatively, it is also noted that the utopia of social networks beneficial to all is found nowhere in real world, where players in the disadvantaged position of net- work could be subject to persistent exploitation (Taylor & Leonard, 2002). Adding the dimensions of evolution and com- petition in social networks, these thoughts address the signifi- cance of social capital as a collective asset in scarcity. In sum, the missing link between the theorized significance of social network and its empirical application is inadequately discussed as a knowledge gap in the literature. As driven by the state-society relations at macro level, the notions of social capital and embeddedness could bring dialec- tic implications in policy-making. The controversy over state intervention is inherited from the divergence in development ideology across political spectrum. As Woolcock (1998: pp. 156-158) identifies, the communitarians are faithful in the po- wer of the authority as welfare state whereas the conservatives strike for the dismantling of the state in empowering civic vir- tue at the other end, sandwiching both the path-dependent ad- vocates who claim the society’s indifference to government action, and the liberal enthusiasts who mediate a sophisticated “check-and-balance” in the state-society relations at a moderate fashion. Just as entrepreneurial process is embodied in interac- tion and transaction among the social networks, altogether they are further restrained by a set of intangible rules and institu- tional infrastructure in context. In empirical term, there show an abundant case of which suggests that local economic growth could be complemented by either way of the state-led initiatives or deregulated governance regime (Guthrie, 1998). However, the informal social networks and formal institutional infra- structure could sometimes be conflictive as they move at the opposite directions. In the context of developing economies, the overreliance on privileged network resources (e.g. guanxi in China’s economy) is often alleged as collusive and corruptive, stumbling the built-up of legal-rational system in shape. Rather than analyzing the inter-firm networks only, locating firms as “networks within networks” could then associate the embed- ding relationship between the organization of firms and the industrial territory in a more holistic view. The scholarship of social capital has its shallow root of em- pirical reference in the developing economies of China. The extant literature in Chinese entrepreneurship has conventionally followed the tagline of guanxi, which praises the significance of personal and informal social networks in the economic domain in the early reform era (Yang, 2002). For instance, Leung (199 3) emphasizes the role of personal contacts in manipulating quasi-legal arrangements for efficient production and subcon- tracting activities across the Hong Kong-PRD border. Never- theless, the antecedent discourse of guanxi renders itself too simplistic and ego-centric as a cultural mechanism playing at the community level exclusively, which could fail to compro- mise the state initiatives in marketization and institutionalize- tion of late. In result, there shows a stern bottleneck for theo- retical advancement in the study of Chinese entrepreneurship. Inspired by the alternative view of Guthrie (1998: p. 255) which takes guanxi as an institutionally-defined system, this paper conceives the study of Chinese entrepreneurship shall only proceed by transcending the guanxi discourse into a more advanced framework that could negotiate with both social and institutional changes. Accordingly, this paper postulates guanxi as a variety of so- cial capital in reconciling the complementary forces of social network and institutional infrastructure in Chinese entrepre- neurship. Conventionally speaking, the form and function of social network is a core component of social capital, which comprises the object of focus in this paper. The notion of social capital is then conceptualized as an embedding mechanism which negotiates the network dynamics between entrepreneurs and the broader context. At aggregate term, it is the socially- embedded resource contributed by both the community partici- pants and state authority of a place. At the individual level, it could be regarded as an accumulation of “investment in social relations with expected returns” (Lin, 2001: p. 19). In this pa- per, social capital is defined as a collective asset of state-society relations variably appropriated to individual entrepreneurs for purposive action. Adapting the “embeddedness-accessibility- use” framework from N. Lin (2001), this paper attempts to analyze the how the stock of social capital impacts upon the Hong Kong entrepreneurs who operate manufacturing activities in the PRD. Research Framework As constructed for an analytical framework, the notion of so- cial capital captures three intersecting dimensions in em- beddedness, accessibility, and use. In here, “embeddedness” determines the influence of overall network resources and op- portunities available in the social structure, which is condi- tioned by both the community integration and state integrity (Uzzi, 1997; Woolcock, 1998). Simply put, a backward society under weak institutional infrastructure could foster repeated exchanges among strong ties through informal channel in the early reform China . Whilst the level of embeddedness could be sensitive to state intervention, its influence upon individuals is relatively macroscopic and chronic. At the micro level, “acces- sibility” to social resources by individuals, according to N. Lin (2001), is appropriated by one’s position in the hierarchical or horizontal network structure. It is commonly postulated that network typology and the corresponding position of entrepre- neurs could in part influence their exposure and perception to business opportunities and thus their relative competitiveness in the community (Ardic hvili, Cardoso, & Ray, 2003; Uzzi, 1997), in which Taylor and Leonard (2002) explicitly warn that pe- riphery actors in an inclined network could easily be exploited or marginalized by network hegemony. The “use” dimension in this framework refers to action-oriented aspect which enables entrepreneurs to acquire the embedded resources from their network access (Lin, 2001). Altogether, the “embeddedness” and “accessibility” concurrently define the form of social net- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 10  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU work and the resources opened to individual entrepreneurs, while “use” or mobilization of these resources determines the function of such social network, which is also hinted as the returns to social capital. The “embeddedness-accessibility-use” framework in this paper could be tailored for clarifying two distinctive theoretical misconceptions in the existing literature. On one hand, it con- sciously separates the form and function of social network as independent entities against any mistreat of confusion or asso- ciation in conceptualizing their relationship. On the other, it embodies the dimensions of social capital from an intermediate perspective across state-society domains. The prevailing litera- ture in studying entrepreneurial network often fail to delineate the policy impact in general and upon individual actors, which might distort the effectiveness of policy evaluation in result. In response, the framework could enhance the responsiveness of policy research by fully utilizing the information gathered from a small sample in a more precise way. By delineating the ag- gregated network structure and the individual position in re- spective network, the framework enables thorough investiga- tion upon the magnitude of independent events (e.g. policy change) at individual and aggregate terms. Meanwhile, it also shows the prospect to evaluate the respective role of social and institutional changes in a compromised manner. After all, the “embeddedness-accessibility -use” framework signifies a trial in advancing the social capital thesis in both the theoretical and empirical aspects. Methodology Drawing from the theoretical and empirical considerations mentioned above, this paper intends to study the impacts of network dynamics and the latest socio-institutional changes on entrepreneurial action in the lately-restructuring PRD. Parti- cularly, the study narrows its scope down to the Hong Kong affiliated manufacturing operations in the region, whose iden- tity and competitiveness have recently been challenged. Field interviews were made with a dozen of Hong Kong entrepre- neurs and also professionals from the associated institutions in the field from 2010 to 2011. Interviews were conducted with open-ended questions at every first encounter, whereas the follow-up interviews and factory visits were arranged selec- tively for more detailed information according to specific the- matic interests. Furthermore, these first-hand data are also sup- plemented by archival review of official documents and Indus- try reports as a triangulated source of reference. Despite the small sample size could provide only a lesser degree of gener- alizability, the in-depth field methods are preferred in appropri- ating the analytical framework of social capital as an empirical case. As for an extract of the research in a limited length, this pa- per gives an investigation into two of the selected entrepreneurs from the sample, Mr. Cheung and Mr. Yeung, for analysis by the “embeddedness-accessibility-use” framework in the fol- lowing section. These two cases are chosen for their typical but outstanding experiences in entrepreneurship from the past to the present, which could provide a prolific profile of network dy- namics and entrepreneurial actions by life stage, particularly after firm emergence and in the subsequent encounters upon socio-institutional changes. The analysis starts with an over- view of the entrepreneurial profile, in the illustration of how the form and function of social network evolves with entrepreneur- rial process throughout the period. A conceptual analysis of social network, which depicts the entrepreneurs’ personal reach and their respective relationship in diagrams of nodes and ties, is conducted to help illustrate the state and impacts of social capital for the Hong Kong entrepreneurs in the PRD. As gath- ered from our interview, the actors involved in the everyday entrepreneurial action are recorded as nodes; whereas the rela- tionship and flow of exchange are represented by ties and ar- rows in the network diagram. Particular intention is put on how far the overall structure (embeddedness) and specific position (accessibility) of one’s network could be realized into pur- posive action (use) and thus for firm growth over time. The analysis is then followed by a discussion over the impacts of recent social and institutional changes in the midst of restruc- turing process. Unless specified otherwise, all information pre- sented below is gathered from our personal interviews. Social Capital and Entrepreneurial Action in the Ever-Changing PRD To put forth the analytical framework of social capital in the study of Chinese entrepreneurship, this paper focuses on the ever-changing process of manufacturing activities in the PRD as case study. As a world-leading manufacturing base today, the nine prefectural cities in the PRD have experienced tre- mendous economic growth since the commencement of reform in 1978. In retrospect, the growth was associated with the proc- ess of manufacturing transplantation from the overseas Chinese diaspora. When the institutional infrastructure was still weak at the early reform stage, the manufacturing activities were pre- dominately supported by “a socially, rather than bureaucrati- cally, mediated form of foreign investment used by small (and some larger) Hong Kong investors” as reckoned by J. Smart and A. Smart (1991: p. 169). In result, the rule of guanxi net- works had boosted the growth of labor intensive manufacturing activities in the PRD throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. Whereas the retreat of state fostered the use of informal so- cial relations (guanxi) in Chinese entrepreneurship in the early reform stage, the development pattern of PRD has experienced further dynamic changes in recent years. Accompanied by China’s accession into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, the PRD has entered a new stage of marketization and institutionalization. Concurrently, the central and provincial governments have initiated the second wave of industrial re- structuring nation-wide, in the hope of promoting a knowledge based economy in the PRD. As explicated by “The Outline of the Plan for the Reform and Development of the PRD 2008- 2020”, those labor intensive and low-end manufacturing active- ties in the prosperous cities are pushed to transform and up- grade themselves into a higher value-added one, otherwise in less capable situation they should soon relocate away to other remote regions (NDRC, 2009). Alternatively, there have been swift socio-economic changes in the PRD after a sustained growth for years. With respect to their respective development paths and closer economic integration between them, the trans- border relationship between the PRD and Hong Kong has also changed at an escalated level after Hong Kong returned to China’s rule in 1997. Altogether, these social and institutional changes in the midst of restructuring process could affect the dynamics of social capital in the region and pose a huge influ- ence on the entrepreneurial action at individual level. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 11  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU The Cases Mr. Cheung has just entered his retirement life after working in mainland China as a factory boss for almost 30 years. His paper box business with local cadres was first started in Huizhou in 1982 and then relocated to Foshan in the 1990s. Mr. Cheung went through many up-and-downs in his business ad- venture, which peaked immediately after establishment but suddenly tumbled afterward. As a joint venture practitioner, he has accumulated so much skill and knowledge in guanxi prac- tice from his observation and experience in mainland China. As illustrated in Figure 1, Mr. Cheung spanned through his friend in Hong Kong to enter the business field in PRD. The local cadres in Huizhou as his first partnering agent helped him in mediating the necessary production factors, including land and labor, against institutional barriers. However, the replace- ment in political leadership cut off the access to all these re- sources. Then Mr. Cheung relied on the intermediate connec- tions in bureaucracy in establishing his next two factories in Foshan in the same way. Inter-firm business connections had persistently been found from both sides of the border which support stable growth in routine operation. Although the tight- ening of pollution standards had forced their way out, Mr. Cheung and his long-serving assistant was able to shut down the business smoothly with the help of the cadre in Foshan. Meanwhile, Mr. Yeung is now one of the industry leaders with his reputed enterprise in the printing sector. As early in 1971, he originated his first printing factory in Hong Kong and only moved to mainland China since 1995. Despite of the per- sistent adversity in the beginning, his business in Dongguan grew steadily and even expanded with new branches beyond the Pearl River Delta in recent y ears. Mr. Yeung has been a chro- ni c innovator and missionary in the industry even after stepping down from major managerial role in his own firm now. Figure 1. Egocentric network of Mr . Cheung. The case of Mr. Yeung pictures an alternative path of enter- prise development as shown in Figure 2. Shortly after gradua- tion, Mr. Yeung did not join his father who ran a small elec- tronics business in their hometown in Fujian. Instead he worked as a clerk in a printing firm which he later acquired. In 1991, he was approached by a township cadre to invest into a joint ven- ture in the Pearl River Delta but the proposal fell down at the end. Two years later, Mr. Yeung resumed the plan and estab- lished a Processing Trade factory in Shenzhen formally under the name of a township and village enterprise in the locality. However, he found the factory could not handle the quota re- ceived from his overseas customers. Introduced by his col- leagues in a banquet, Mr. Yeung was aided by another local leader to register a Wholly-owned Foreign Enterprise for full- scale production in Dongguan in 1995. In recent years, Mr. Yeung stretched the reach of business into his hometown in Fujian through a group visit with the industry association be- fore conveying all of the authority to his children. Embeddedness Embeddedness refers to the typology of overall network and thereby the resources available in the social structure, which could be identified by the presence of other actors and opportu- nities derived from the broader business environment where the entrepreneurs are connected within. In the network diagram of Mr. Cheung (Figure 1 above), it is convenient to figure out the indispensable node of local cadres both as the intermediaries to introduce new acquaintances (the bold lines) for the Hong Kong entrepreneurs, and as the mediators to smooth everyday operation of the firm (the arrow towards “Cheung”) through their bureaucratic affiliations (dotted lines) in the local firm- environment nexus. It is noted that the establishment process Figure 2. Egocentric network of Mr. Yeung. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 12  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU and organization structure of Mr. Cheung’s enterprise was un- der the omnipresent influence of the local authority in mainland at that time. They dictated the site and construction of the fac- tory. Their sugar business firm was the designated source sup- plier in priority, while they also helped bridging Mr. Cheung to some downstream customers maintained with gift connection in the domestic market. In the registration procedures, the invest- ing cadres sheltered the enterprise from red tape by various bureaucratic departments. They had also been powerful in set- tling resource and institutional constraints for daily entrepre- neurial processes. When asked about the key aspects to the business environment in the 1980s, Mr. Cheung recalled the resource constraints in the underdeveloped China. The locality in Huizhou suffered from the shortage of raw materials and infrastructure. With the referral from his cadre-partners, he often rang the responsible bureaucrats up for the grant of extra electricity in frequent cases of power cut. Transportation was difficult with undulating roads and inadequate vehicles. When ordinary carriers were unavailable, he had to borrow military trucks in the purpose of logistics. Workers were also hired at an illegitimate basis as sheltered by the local bureaucracy. It was reported that many of these transactions and business processes were not governed by formal contract or open market. Instead, they were more often acquired at the expense of gift payment, and endured by the use of informal personal guanxi. The grey area and loophole in the business field had created much room for flexible implementation of policy which was subsequently filled with the rent-seeking behavior by local cadres. Being the official resource allocator, the bureaucratic coalition was so powerful that could monopolize local economy in almost every aspect without any other check in balance. Two major implications could then be drawn from here. In the first place, it cost Mr. Cheung and other entrepreneurs much time and efforts in negotiating and cultivating informal guanxi with their bureaucratic affiliates (the arrow towards “local cadre- partners”), which could justify the simple internal structure of these small family enterprises and underline their limits in management practice and innovation capacities. Secondly, it is noted that many transborder enterprises like Mr. Cheung’s were over-embedded by specific informal social ties around a few cadre-affiliates but not the others, which made the industrial linkage and market coverage in the loca lity particularly na rrow and fragile. Sometimes Mr. Cheung called for help from the mainland officials directly. At many other times, Mr. Cheung was benefited from the network reach of his cadre-partners without getting know the real person-in-charge directly, in which the structural holes between Mr. Cheung and other actors (e.g. Labor authority), that could only brokered by the cadres without extra assurance, are shown in the open network of Fig- ure 1. An open and imbalanced network structure predomi- nantly inclined towards local cadres might then be consolidated and reinforced in a path-dependent manner, which will be fur- ther discussed later. As illustrated in Figure 2, the network diagram of Mr. Ye- ung also reflects the significance of personal access with local bureaucracy for many entrepreneurial processes. Local cadres at the township and village level had been actively inviting overseas Chinese manufacturers for business ventures, and the case of Mr. Yeung finds no exception, as his first venture was also approached by the local cadres, featuring a “passive search” process of business opportunity discovery in an acci- dental manner (Ardichvili et al., 2003). Meanwhile, the case of Mr. Yeung also demonstrates how the entrepreneurial action of Hong Kong investors could be limited or discriminated by the institutional system at the other side of the border. As derived from the different venturing models of his two firms, their or- ganization structure and operation flexibility were confined in various ways. The processing trade factory was formally owned by the mainland township corporation and its cadre-affiliate was the board of directors in effect. But Mr. Yeung was in practice the in-charge for all the inputs and process manage- ment of the factory, an entity which he might also bear the re- sponsibility in circumstances. Although the “sanlaiyibu (三來 一補)” establishments were granted preferential tax and cus- toms payments and other procedural treatments, they suffered from the risk of incomplete property rights and quasi-formal regulation in comparison to his Wholly-owned Foreign Enter- prise. For the Wholly-owned Foreign Enterprise, Mr. Yeung was the sole owner-and-manager and most of the key positions in the factory were also the appointees of his. Its major source suppliers and downstream customers, however, were all from overseas market maintained with repeated transactions and offers, as the equal-status participation of foreign enterprises in domestic economy was explicitly confined by the protectionist regulatory regime which prohibited local market entry. Seem- ingly it could be an all-or-nothing scenario for Mr. Yeung— either fully embedded into the social network inclined to local cadres with the sanlaiyibu operation, or entirely disconnected from the network of local economy with the export-oriented foreign enterprise. Observing from a long-range perspective, however, a slightly different form of network embeddedness could be identified. Mr. Yeung did not solely count on the local bureaucracy for the convenience in regulation and resource supply in his operation. Alternatively, he had been networking in an extensive pool of business acquaintances for vast overseas market and other op- portunities. The Industrial chamber is one of the major channels to acquire latest market information and production technology through arm-length ties. It does not imply the closely embedded ties were totally abandoned, as he is currently consolidating the familial business with the help of his family members. He sim- ply did not stick with all of the preexisted bonding ties, but kept actively and directly in touch with key acquaintances like the head figures in the Bureau of Press who take charge of censor- ship and publishing. Such strategy of network diversification spearheading the growth of the firm since late 1990s verifies the scholarly emphasis on both embedded ties and arm-length ties in achieving success (Uzzi, 1997). As concomitantly emphasized by various scholars, govern- ment cadres and their affiliates at the grassroots level had been the very monopoly governing almost all aspects of local eco- nomic activities ranging from labor relation to custodial ar- rangement (Yang, 2002). With a lack of trust in institution due to partial reform, guanxi networks were often built, after re- peated plays of reciprocal exchange and socialization, among individual persons across the border which smoothed the ven- turing and operation processes in the transition economy. In this regard, it could be seen that entrepreneurial networks in the PRD were deeply embedded in a hierarchical structure centered on local cadres, which offered quasi-legal opportunities for economic gains. Accessibility Accessibility could be better interpreted as the specific net- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 13  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU work position of entrepreneurs acquired in the social structure network, which indicates the relevant opportunities accessible by the individuals for purposive action accordingly. The pair of cases by Mr. Cheung and Mr. Yeung could well illustrate how network position matters in guanxi relationship and for entre- preneurial action. Mr. Cheung, as an enthusiast in socialization, was very progressive in attending banquets and sending gift. He thought it was the indispensable way to make up his foreign identity and be accepted by the local officials. When Mr. Cheung and the representatives from a locality in Huizhou met at the very first few contacts, they exchanged gifts of tobacco and alcohol and took turns in paying the entertainment to show their esteem and friendliness for each other accumulatively. Such early process of gift exchange matched with the guanxi building model which aimed at nurturing mutually beneficial relationship in long term (Yang, 2002). The state of reciprocity persisted until the agreement over a joint venture formation that turned their preexisted piecemeal transactions into a legitimate organization. The mutually reciprocal relationship at start was however soon dispatched by a parasitic exploitation under power ine- quality after the venture in Huizhou formed. Instead of an equal partnership, however, the joint venture bound Mr. Cheung to work for his cadre-partners as a subordinated agent in the net- work (represented by the imbalanced weight of lines in Figure 1). Whereas Mr. Cheung attained a smaller company share irrespective to his actual investment, the previous scene of re- ciprocal gift exchange also disappeared and was replaced by constant payment to the cadre-affiliates as “entertainment al- lowance” in the firm’s expenditure account. Mr. Cheung failed to resist his cadre-partners and they aggressively colluded in various rent-seeking moves, which included tax evasion, par- ticipation in black market, and smuggling. Although he profited from such embedded tie with far greater income than his pre- vious occupation, he should have attained it with the enterprise if he could allocate the resource in optimizing firm’s operation instead of pouring them all-in for socialization. The monthly expenditure in “entertainment allowance” was up to six digits, an amount quintuple to his salary and bonus. The efforts in maintaining guanxi with the cadre-affiliates were so intensive and costly that inhibited any further attempts to diversify his network reach and identify new business opportunities. Yet Mr. Cheung could not live without the parasites as they were row- ing in the same boat. When his cadre-partners were forced out of the local office in Huizhou and the first venture had to close down without alternative support (indicated by the cross in Figure 1), Mr. Cheung could only count on the tie as brokerage for new factory ventures in Foshan (the dotted node in Figure 1). Accordingly, another embedded tie was built with the local cadres which Mr. Cheung claimed he “really good friends there after a period of time”, the “reciprocation-exploitation” cycle repeated until the ventures were blown off by a new current of policy regulation in recent years. By wearing down the prospect of upgrading and opting for immediate benefit, it was the dis- advantaged position of Mr. Cheung, over-embedded in the asymmetric structure, which later spoiled the ventures eventu- ally. The case of Mr. Yeung demonstrates an alternative way of how network position evolved over time and its implications to entrepreneurial action. As mentioned, Mr. Yeung still regards personal access with the bureaucracy important but he seldom drowned within any specific embedded ties. He always showed up in banquets and events hosted by colleagues in the industry and greeted almost every cadre with gifts directly. In setting up the Processing Trade factory as a pioneer attempt, Mr. Yeung promised the local cadres to contribute a processing fee at pre- mium in order to skip the registration procedures. From this onward, he kept a longer distance for these ties and rejected many of the incoming offers that were all tempting in retrospect —neither undertaking the guaranteed domestic orders by means joint venture, nor involving himself in the underground transac- tions of printing machinery. It is admitted that the unwilling- ness to speculate with the embedded guanxi ties led to the many inconvenient treatments received in return, which explained the obstructed growth of Mr. Yeung’s factories in the first few years. In line with the strategy of diversifying network aforemen- tioned, meanwhile, Mr. Yeung did reciprocate in all different accounts of guanxi ties (represented by the more balanced weight of lines in Figure 2). At times of festival every year, he had been sending gifts to key acquaintances, including the head figures in the Bureau of Press, to solidify the continual support from these embedding ties. At the same time, he did not attempt to exploit premium value from these actors for any further in- termediary assistance. In result, most useful ties have been connected to Mr. Yeung directly without the problem of struc- tural hole and thus any over-reliance on specific brokers. On the other hand, although Mr. Yeung was neither involved in domestic market transaction nor any colluding moves for the transfer of benefits in the local economy directly, he still bene- fited the whole community in two major aspects—infrastruc- ture improvement and technology transfer. These actions did not help consolidated any specific ties within the network, but definitely strengthened his own reputation in the locality. In reward, his influence in the industry chamber and all those arm’s length bargains rose significantly in later years. Accord- ingly, the tradition of reciprocity here did not evolve into forms of exploitation that beset Mr. Cheung in the preceding case. Mr. Yeung did not lose his fairly proximate position in the network and was seldom stumbled by specific guanxi ties in accessing extra-firm resources. Use Finer analysis suggests several implications to the function of social capital in Chinese entrepreneurship. Based on the empirical findings gathered from the above cases, it could be concluded that having a good guanxi network, especially with the local bureaucracy, was crucial in achieving greater entre- preneurial success in the early-reforming PRD, which was al- ready suggested elsewhere in the preexisting literature (Chen, 2000). This study, however, further spots that the enterprise development in long-term and the embedding relationship with- in firm-environment nexus could not be merely explained by the stock of social network or the level of embeddedness. The rifts in the utilization of structural embeddedness and network position as said, therefore, constituted the ultimate crux of con- verting the accessible social resources into purposive action for individual benefits. Originated as a relational asset in the society, the theoretical construction of social capital in entrepreneurship could only be tenable if it is genuinely captured by an individual entrepre- neurrial unit through the mediation of value in the networks. In this regard, the conduct of gift exchange in the Chinese busi- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 14  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU ness context is conceptualized as the intricate basis in achieving mutual trust beyond immediate material benefits (Hsing, 1996; Smart, 1993). However, evaluating the accumulation of trust by equating it to the stock in social capital or embedding ties is far too simplistic away from the practical world. Just as the gifts and favor invested in the interaction have often been unrecip- rocated, the apparent guanxi networks and trust nurtured as part of social capital are not always readily convertible into real benefits for individual entrepreneurs. To make it clear and pre- cise, it is worthwhile to recall that “social capital can never be more than potentiality: once cashed in, it becomes something else (e.g., economic capital)” (Smart, 1993: p. 396). The answer key to the variance in competitiveness and performance among enterprises is, thus, a matter of efficaciousness in utilizing guanxi and conveying social capital rather than the accumula- tion of the stock solely. Derived from a different set of network structure and position, entrepreneurs could have different types of function and use value for their social capital. As illustrated in the above cases, the enterprises of Mr. Yeung have slow but solid long-term development as he manipulated social relations into the establishing of reputation as symbolic capital for fur- ther growth of the firm, whereas Mr. Cheung could capture immediate but exhaustive revenue despite of his enthusiasm in building guanxi. As shown in above, Mr. Cheung in this study could only capture a slice of immediate but occasional revenue in the cadre-driven coalition, which was disproportional to his persis- tent investment in the guanxi ties. At the beginning, it was true that the cadres were able to shelter Mr. Cheung from the unau- thorized act for black money apart from facilitating supply against resource constraints. One example is the illegitimate premium profited from the dual track currency system until 1994. As the official exchange value of “Renminbi (人民幣)” was set unrealistically lower than the market price, the differen- tials were captured by local cadres and the sheltered enterprises through black market transactions stealthily. Experience told that profit of the enterprise was more often acquired from the exclusive preferential treatment external to concrete factory process. The immediate revenue at individual level cashed-in from the cadre-entrepreneur coalition could also be regarded as an economic capital otherwise. Whereas the underneath incen- tive scheme facilitating the cooperative efforts was seemingly reinforced after successful trials repeatedly, they further pushed many of the entrepreneurs to re-invest and even raise the stake in these embedded ties instead of developing weak ties. As proven in the case, the cost of socialization for them paradoxi- cally increased over time, despite of the deeper relationship as expected and the diminishing margin of rent-seeking profits from collusion and cooperative efforts. Again, power relation and entrepreneurial position in the network structure is of a critical importance in the process of opportunity conversion and profit re-appropriation among the agents. As argued by Taylor and Leonard (2002), agents at a disadvantaged position in the social structure could be exploited as the “labor” working for social capital and thus resistless in reverting but reinforcing the status quo. In the coupling of the cadre-entrepreneurial network, Mr. Cheung showed the inability to convert the stock of guanxi into favorable functions for their own firms. In contrast, the enterprises of Mr. Yeung have a more solid and prosperous long-term development with his better utiliza- tion of network. Despite his lack of devotion in liaising strong ties with the privileged class in mainland, Mr. Yeung could still mobilize and turn the diversified encounters of socialization into foreseeable opportunities for establishing the reputation of his firms. In such case, the premium to the socialization upon the initial guanxi base is articulated in the slowly-accumulated stock of interpersonal guanxi but also the emergence of organi- zation-based ties and, more importantly, the firm-specific repu- tation established, which is a function or return converted in the form of symbolic capital. Symbolic capital, or the “resources that are generalized as the attribution to individuals” as sug- gested by Smart (1993: p. 393), is differentiated from guanxi which necessarily depends on particular dyadic ties and rela- tionships. Such symbolic capital, once internalized, is built as the trustworthiness and goodwill of the firm exclusively, which in turn helped avoiding the cost and potential trouble incurred with bureaucratic red tape, and offered new opportunities for the endogenous growth of the firm. As in the words of N. Lin (2001), the giver of the favor was gratified by the reputation as a social return. The Latest Institutional Changes in the Post-WTO Pearl River Delta Whereas the above “embeddedness-accessibility-use” frame- work suggests how the trivial difference in the configuration of social network could work specifically upon the divergent path of entrepreneurship in the early reform period of the PRD, such impacts could become even more significant to the individual firms and aggregated development as time goes by. As China now enters another stage of marketization, the decentralized local economic autonomy has been gradually by a better-exe- cuted regulatory regime with highly standardized requirement. Stiff embeddedness or too much guanxi bonding might, how- ever, restrain the old-fashioned enterprises from optimizing operation as introduced above, thus hindering the state’s inten- tion towards techno-economic restructuring. Given their highly- polluting and labor-intensive characters in manufacturing proc- ess, and the incomprehensive linkages with local industries (except with the key cadre-partners) in community embedding, some entrepreneurs like Mr. Cheung could become so vulner- able and isolated when the advantageous institutional environ- ment was gradually unleashed by changes in policy direction from the central government as summarized in Table 1 below. As a matter of fact, C. Yang (2010), in a resembling scenario, argues the lock-in effect arose in the locality as a phenomenon of “institutional inertia” due to compiling entanglement. This study agrees with the statement and further proposes the fol- lowing implications. The institutional turn, together with the shift in techno-eco- nomic production paradigm, did pose unprecedented challenges to the survival of many transborder enterprises which are small to medium in size (SMEs). Sheltered from ineffective market and institutional governance, these resource-deficient firms were operated under an old incentive scheme mediated by in- formal guanxi networks which often favored short-term specu- lation and rent-seeking behavior. Though efficient in practicing mass production and promoting local economic growth, the competitiveness of these firms were often built at the expense of labor exploitation and bureaucratic corruption. It is undeni- able that the phenomenon of “institutional inertia” has ob- structed the state’s latest policy to remove the processing trade industry out of the PRD. The transborder enterprises could not be easily transformed or relocated under the tradition of protec- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 15  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU Table 1. Key changes in institutional environment in the 21st century. Date Key Event 2001 China’s accession into the World Trade Organization Relaxed controls on operation of Foreign-funded enterprises 2003 Opening up the foreign trade sector 2004 Implementation of <Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement > 2005 Reform & appreciation of Renminbi exchange rate 2007 Tightened restrictions on products for Processing Trade 2008 Commencement of < Labor Contract Law> Union of corporate income tax system on domestic and foreign enterprises Proclamation of <The Outline of the Plan for the Re for m and Development of the Pearl River Delta 2008-20 20> Global Financial Tsunami a nd economic recession 2010 Proclamation of <The Framework Agreement on Hong Kong and Guangdong Cooperation> tionism and entangled guanxi relations in the localities. The problem of incapability in innovation and expansion were also commonly found among the respondents in this study. Taking Mr. Yeung as an example, when the overseas exporting market become stagnant, he has thus been consciously breaking into local market but found inferior to the domestic competitors in terms of local marketing coverage and even financial founda- tion. As production cost has been increasing along with wage inflation and appreciation of Renminbi, many SMEs living on the margin have no choice but to terminate operation. Latest report from the Hong Kong Trade Development Council shows that a quarter of the Hong Kong-invested manufacturing firms interviewed in 2007 are currently considering close-down in counteracting the prolonged loss. The representative of Hong Kong Productivity Council also suggests in an interview that over one-third of the Hong Kong-invested SMEs in the PRD are currently forced to retract or idle in withstanding the hard- ship. As a matter of fact, Mr. Cheung is in this prototype whose factories failed to adapt the latest current of state regulations in pollution and employment. If there has ever been an accumula- tion of social capital in Mr. Cheung’s case, the stock was never converted into his own possession but left in the embedded ties or dyads exogenous to the firm, although the lucky bet on the right trustee to some extent still helped him out of the trouble until the end. More importantly, the over-reliance on local bu- reaucracy, voluntary or involuntarily, have detached them from the experience and logic of normative exchange with other actors in a direct way that would have promoted other potential relationships and coordinated adaptation in the locality (Uzzi, 1997). Many of these ethnically-linked transborder firms could not be regarded as having truly embedded in the arena until autonomous participation in the domestic market or local in- dustrial chain is achieved. Nevertheless, Mr. Cheung complained official support was far from adequate. With a foreign personal identity regardless of their venturing forms, these transborder entrepreneurs were discriminated in applying equity loan for financial assistance in mainland. The Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in Guangdong, which is meant to be the main official body in dealing with transborder economic issues, seldom intervened in genuine economic affairs (except the personal security of citi- zens) until some pilot efforts recently. Records showed a slight chance for the majority of them to upgrade or relocate success- fully in short term, and more and more are opting into liquida- tion when the global economy went down and the production cost rose simultaneously (FHKI, 2010). The resulting decline in productivity of these individual enterprises could even encum- ber the overall competitiveness of those industrial regions where foreign investment from Hong Kong and other ethnic Chinese dominated a major share. The rise of institutional regulation, which contributed to the close-down of those poorly-equipped factories like the one in the case study of Mr. Cheung above, should give some glimpse of hope in converting the situation. The tightening decree from the central state towards institutional standardization since China’s entry into WTO has squeezed the room for flexible interpretation and thus the potential benefits of informal social exchange. Although the local cadres still preserved limited right in relaxed implementation, the institution regime has gained the momentum in leading the economy in a bright direction with less uncertainty. In other words, the situation of over-em- beddedness in the PRD localities have been on the verge of change, if not collapse, by the re-entry and intervention efforts of the central and provincial governments from top-down. Meanwhile, further implications could be derived from the case of Mr. Yeung about the impacts of institutional changes in recent years. Since China’s entry into WTO, there have been extensive institutional moves in reregulating the printing Indus- try which aim to standardize the monitoring mechanism and heighten the requirements in pollution control and labor welfare. The processes of censoring and custody were integrated among various government departments, which now favor those re- puted and qualified enterprises. Restrictions on the processing trade activities and the use of highly-polluting materials have been tightened to drive out the weaker firms. Apart from insti- tutional advancement by the mainland government, there have also been pilot attempts for transborder coordination. Collabo- rating efforts were established by the municipal governments in the PRD to facilitate upgrading, transformation and relocation for the transborder enterprises. The “Cleaner Production Part- nership Program” was jointly launched by the environmental authorities in Guangdong and Hong Kong in April 2008 to promote voluntary practice in lowering pollution. Mr. Yeung is one of the early participants having benefited from the subsidi- ary assistance and but also contributed as the modeling plants of the scheme for future reference. Such a series of efforts expose the importance of enterprises in utilizing their social capital accumulated earlier. The adap- tion and readjustment made were positive as indicated in the case of Mr. Yeung, who utilized his network position to access the new institutional support. Meanwhile, Mr. Yeung expressed that many of his colleagues had a huge setback when they re- ceived the new order to forbid the use of specific printing mate- rials immediately, and it was after direct negotiation between the industry representative and the Bureau of Press which the policy was temporarily suspended and a severe loss was avoided. Communication with and accessibility to formal insti- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 16  C.-Y. LEUNG, J. XU Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 17 tutions, thus, became an indispensable channel to follow if not advance the market and policy trend nowadays. Whereas those who have been in a better network position continue to thrive, some others were stumbled by the “institutional inertia” they had depended on, and thus failed to survive the threats subse- quently. All in all, the configuration of social capital in Chinese en- trepreneurship is ever changing at an escalated level. Firms that have been over-embedded and poorly-positioned in the infor- mal guanxi networks are now forcing their way out of the ad- vanced region in the PRD accordingly. Alternatively, recent institutional breakthrough across the border has boosted the significance of converting earlier entrepreneurial attention about guanxi networks into formal coordinating channels in fu- ture. It further promotes the profitability for individuals to nur- ture enterprise social capital in the institutional arena and thus the re-building of embeddedness in the region. From a different perspective, it could be regarded as an institution-led initiative of market elimination according to the network position of enterprises, accompanied with a painstaking process of recy- cling in the stock of enterprise social capital. Wise coordinating efforts, by government authorities and associated organizations on both sides of the border, are required to smooth the trans- formation process and rule out the adversity of hollowing-out in the region. Conclusion This paper acknowledges that social capital had been an in- valuable source of collective asset in Chinese entrepreneurship. Interview results from a pair of detailed cases in two Hong Kong entrepreneurs operating in the PRD provide an evidence of association between network dynamics and entrepreneurial action as illustrated by the “embeddedness-accessibility-use”. Finer analysis shows long-term reputation building and imme- diate rent-seeking behavior could be two distinctive functions of enterprise social capital. Meanwhile, the paper also investi- gates the impacts of recent socio-institutional changes upon the Hong Kong entrepreneurs. It is argued that a more formal and institution-led regime is being nurtured as a new source of competitiveness in the region. The renewal in the stock of en- terprise social capital could then be crucial in reconfiguring the network dynamics and entrepreneurial action, and projecting future trajectory of industrial development in the PRD. This paper recalls the notion of social capital as a promising but underdeveloped approach in theorizing the new economic ge- ographies in the transitional period of China. REFERENCES Ardichvili, A., Cardoso, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneu- rial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 105-123. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4 Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). New York: Greenwood Press. Chen, X. (2000). Both glue and lubricant: Transnational ethnic social capital as a source of Asia-Pacific subregionalism. Policy Sciences, 33, 269-287. doi:10.1023/A:1004882907559 FHKI (Federation of Hong Kong Industry) (2010). Made in PRD re- search series III: Hong Kong manufacturing SMEs: Preparing for the future. URL (last checked 17 A pril 2011). http://www.industryhk.org/english/survey/files/MadeInPRD_III_EN G_2010.pdf Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 481-510. doi:10.1086/228311 Guthrie, D. (1998). The declining significance of guanxi in China’s economic transition. The China Quarterly, 154, 254-282. doi:10.1017/S0305741000002034 Hsing, Y. (1996). Blood, thick than water: Interpersonal relations and Taiwanese investment in southern China. Environment and Planning A, 28, 2241-2261. doi:10.1068/a282241 Leung, C. (1993). Personal contacts, subcontracting linkages, and de- velopment in the Hong Kong-Zhujiang Delta region. Annals of the Association of American Geogra p hers, 83, 272-302. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1993.tb01935.x Lin, N. (2001). Social capital: Networks and embedded resources. In N. Lin, K. Cook, & R. Burt (Eds.), Social capital: Theory and research (pp. 3-30). London: Aldine Transaction. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511815447.002 NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission) (2009). The outline of the plan for the reform and development of the Pearl River Delta (2008-2020). No . 1. URL (last checked 11 October 2012). http://en.ndrc.gov.cn Smart, A. (1993). Gift, bribes, and guanxi: A reconsideration of Bourd- ieu’s social capital. Cultural Anthropology, 8, 388-408. doi:10.1525/can.1993.8.3.02a00060 Smart, J., & Smart, A. (1991). Personal Relations and divergent econo- mies: A case study of Hong Kong investment in south China. Inter- national Journal of Urban and R egional Research, 15, 216-233. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.1991.tb00631.x Taylor, M., & Leonard, S. (2002). Embedded enterprise and social capital: International perspectives. Aldershot: Ashgate. Uzzi, B. (1997). Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 35-67. doi:10.2307/2393808 Woolcock, S. (1998). Social capital and economic development: To- wards a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and So- ciety, 27, 151-208. doi:10.1023/A:1006884930135 Yang, C. (2010). Restructuring the export-oriented industrialization in the Pearl River Delta, China: Institutional evolution and emerging tension. Applied Geography, 32, 143-157. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.10.013 Yang, M. (2002). The resilience of guanxi and its new deployments: A critique of some new guanxi scholarship. The China Quarterly, 170, 459-476.

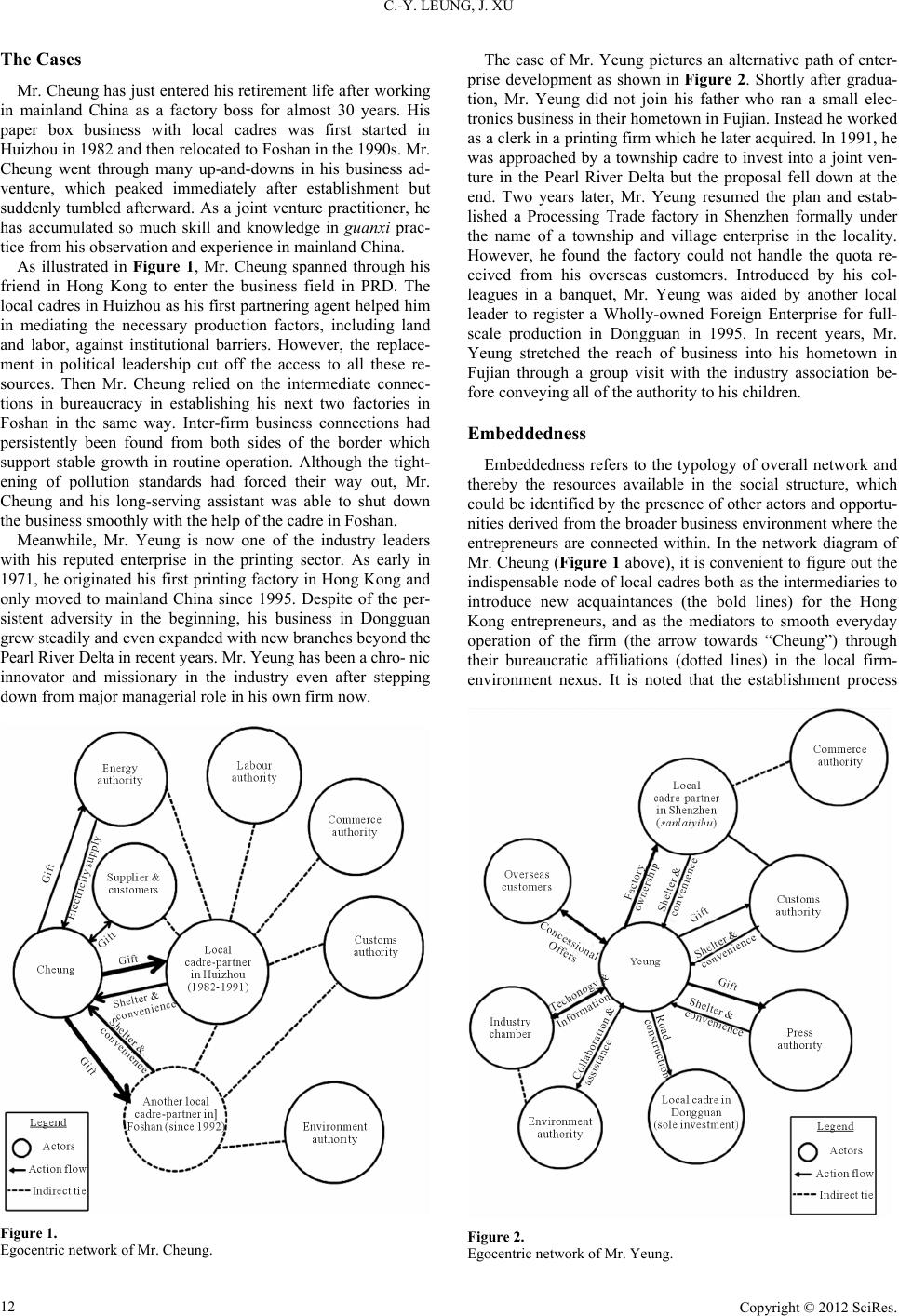

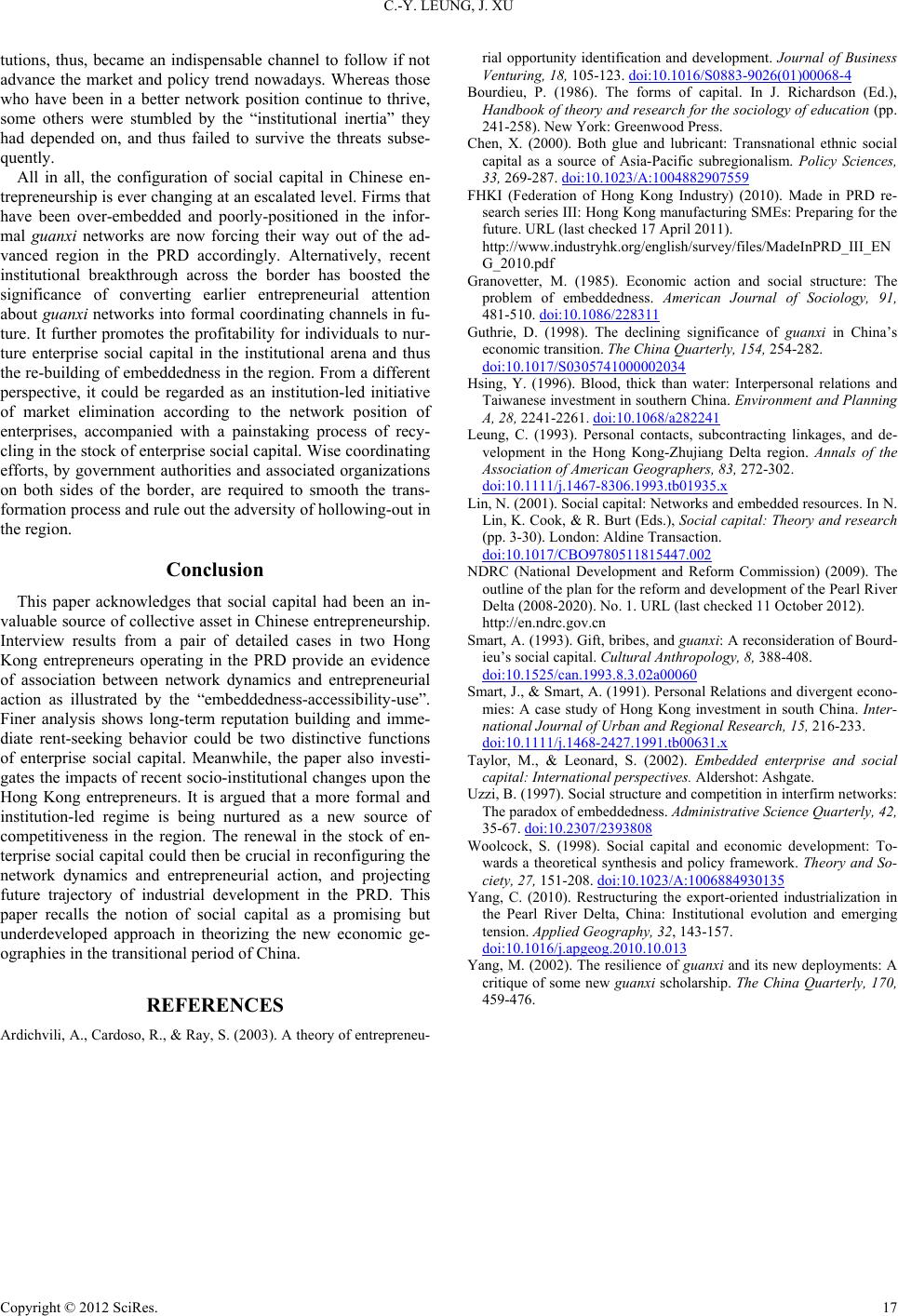

|