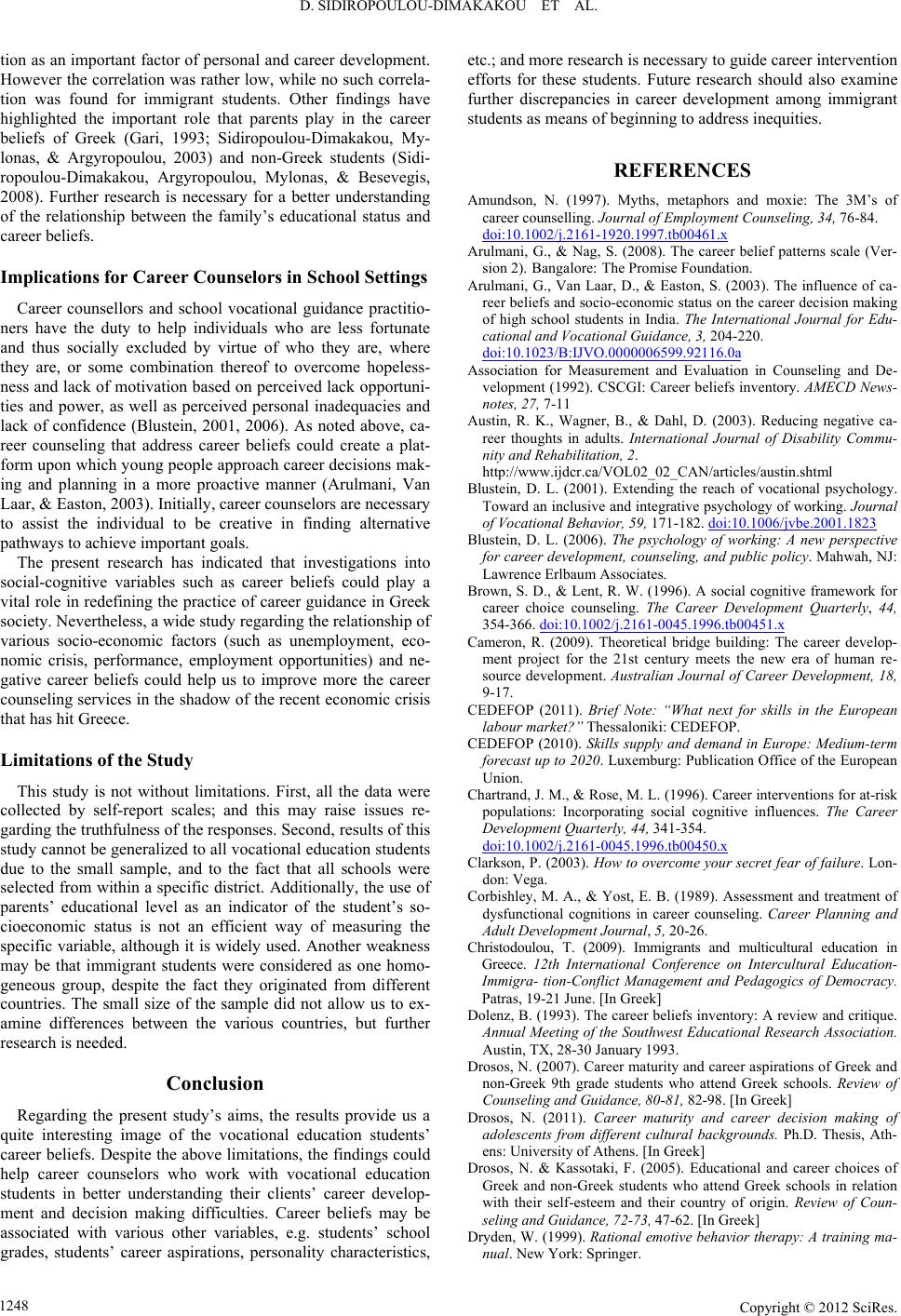

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.7, 1241-1250 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.37183 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1241 Career Beliefs of Greek and Non-Greek Vocational Education Students Despina Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, Katerina Argyropoulou, Nikos Drosos, Maria Terzaki Career Counseling Research and Assessment Center, Department of Psychology, University of Athens, Athens, Greece Email: dsidirop@psych.uoa.gr Received September 5th, 2012; revised October 2nd, 2012; accepted October 17th, 2012 The present study aims at investigating Greek and non-Greek Vocational Education students’ career be- liefs. The sample consists of 238 students who attend Greek Secondary Vocational Education schools in the region of Attica. The study also investigates whether various demographic variables (e.g. gender, im- migrant status, parents’ educational level) differentiate these beliefs. Career beliefs were assessed by Ca- reer Beliefs Patterns Scale-2. Five factors were found to contribute to career beliefs: Culture & common practice, Proficiency beliefs, Control & self-direction beliefs, Persistence beliefs, Fatalism & Socioeco- nomic status impact. The results revealed statistically significant relationships between the level of career beliefs and gender and immigrant status. Findings are discussed in terms of their practical applications for career counseling. Keywords: Career Beliefs; Vocational Education; Immigrants Introduction Over the two last decades, a significant amount of attention has been directed toward researching career beliefs. Career be- liefs are a “conglomerate of attitudes, opinions, convictions and notion, (which) seem to cohere together to create mind-sets and beliefs that underlie people’s orientation to the idea of a career” (Arulmani & Nag, 2008: p. 5; Arulmani, Van Laar, & Easton, 2003: p. 194). Career beliefs are defined as positive and nega- tive thoughts or assumptions people hold about themselves, oc- cupations, and the career development process (Roll & Arthur, 2002). Career guidance practitioners can often identify several beliefs of their clients, which influence career decision making. Negative thoughts prevent the person to think in a systematic and organized way to solve a problem or to make a favorable decision. By contrast, positive thoughts help the person to suc- cessfully combine his knowledge of himself and the world of work and solve career related problems (Saunders, Peterson, Sampson, & Reardon, 2000). All career choices or changes in career behavior require some kind of cognitive intermediation, and career beliefs operate as the intermediate factors that direct these changes in a certain direction (Keller et al., 1982). The present paper, after introducing readers to the theoretical concept of career beliefs and the high importance of people’s cultural background, presents the results of a research regarding career beliefs of Greek and immigrant students who attend Se- condary Vocational Education Schools in Greece. The major role of career beliefs in career development has been demonstrated in several studies (Amundson 1997; Char- trand & Rose, 1996; Mitchell & Krumboltz, 1996). People’s beliefs about themselves and the world of work influence their approach to learning new skills, developing new interests, set- ting career goals, making career decisions, and taking action towards career goals. Career beliefs may also, be manifested in various ways during the different stages of the career decision- making process affecting individual’s aspirations and actions (Austin, Wagner, & Dahl, 2003), which can lead to making ca- reer decisions in a certain manner (Clarkson, 2003). The major- ity of researches regarding career beliefs focus on negative beliefs that can result in lack of satisfaction with the particular choice, reduced self-esteem and low confidence in his ability to take effective decisions (Santos, 2001). The various researchers have used several different terms to describe these negative career beliefs, such as: misconceptions (Thompson, 1976), dys- functional career beliefs (Krumboltz, 1990), self-defeating as- sumptions (Dryden, 1999), irrational expectations (Nevo, 1987), dysfunctional cognitions (Corbishley & Yost, 1989), faulty self- efficacy beliefs (Brown & Lent, 1996) and dysfunctional career thoughts (Peterson, Sampson, & Reardon, 1991). According to the theoretical principles of the Social Cogni- tive Career Theory (SCCT) (Lent, Brown, & Hackett, 1994) and the Social Learning Theory (Mitchell, Jones, & Krumboltz, 1996) career behavior is largely determined by a person’s be- liefs and thoughts. Career counselors may help individuals to recognize, challenge and change such beliefs and to develop readiness to respond to opportunities in a more rational way (Nathan & Hill, 2006). In recent years, career decision-making is a difficult and confusing process, as career moves away from the older, linear model based on a network of professional and educational be- liefs and experiences (Cameron, 2009). Rising unemployment and economic insecurity lead to psychosocial problems and maximize negative and dysfunctional thoughts. Cultural Diversity and Career Beliefs A growing number of published international studies indicate that cultural diversity affects career beliefs. Minority popula- tions confront significantly more problems in their career de- velopment (Luzzo & McWhirter, 2001; Perrone, Sedlacek, &  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Alexander, 2001). Groups of culturally diverse population seem to avoid systematic long term planning and tend to aspire for careers that are considered lower in prestige (Misra & Jain, 1988). According to Gloria and Hird (1999) minority students might have the skills and abilities to successfully compete with majority students and make career decisions, but they may not believe that they will be allowed to enter or to be accepted in the labor force under the same terms with the majority students. It is much more likely for minority population to consider their race as an obstacle in their career development (Luzzo, 1993). Recent researches in minority students showed that they antici- pated more obstacles in their future career than the majority students (McWhirter, 1997), and had much lower self-efficacy beliefs regarding their ability to overpower these obstacles (Lu- zzo & McWhirter, 2001). Beliefs incorporated in the culture of community are likely to be transferred to the younger members through a process of social learning, while the appeared models of career opportuni- ties, the limited representative experiences, and failures play an important role in the development of self-efficacy for the career planning (Frost & Marten, 1990). When these beliefs function as a barrier and do not permit the individuals to engage in ca- reer decision making, career counseling should focus in chan- ging these beliefs to more functioning ones. Many researchers focused on minority groups’ ability to overcome the various social, educational, and economical ob- stacles, highlighting the importance of social support, family, socioeconomic status, and intervention programs (Stewart et al., 2008). The great significance of feeling that their significant others (parents, teachers, etc.) support them and have faith in their abilities and possibilities has been noted by many resear- ches (Fisher & Padmawidjaja, 1999; Juntunen, Barraclough, Broneck, Seibel, Winrow, & Morin, 2001). Greece hosts a large number of foreign students. Immigrants are estimated in about two millions (in an eleven million popu- lation country) and they represent a 10% of students in Greek schools (IPODE, 2009), while in many schools of Athens im- migrant students exceed 80%.1 They are vulnerable to dis- crimination, poverty and exploitation. The large percentages of immigrants create a new situation: research has to be conducted to determine their needs in order to see what kind of interven- tion programs should be implemented. It is important to take into consideration that they do not constitute a homogeneous group and therefore the various subgroups have different char- acteristics (Drosos, 2011; Motti et al., 2005, 2008a, 2008b). The underlying assumption of various studies regarding cultural diversity and career development in Greece, was that the cul- turally diverse students face problems in career decision mak- ing as they have lower level of world of work knowledge (Dro- sos, 2007, 2011), tend to have problems in career exploration (Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, 2003) and seem to exhibit negative and unhelpful beliefs to the affective dimension of career deci- sion making (Drosos, 2007, 2011; Drosos & Kassotaki, 2005; Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, Argyropoulou, Mylonas, & Beseve- gis, 2008). Additionally immigrant students in Greece tend to aspire for careers that are considered lower in prestige (Drosos, 2007; Drosos & Kassotaki, 2005; Papadopoulou, 2005; Sidiro- poulou-Dimakakou & Drosos, 2010). Their aspirations reflect Greek society’s career stereotypes regarding minority popula- tion and their own negative career beliefs, as well as the actual image of labor market, and as Sidiropoulou, Argyropoulou and Drosos (2008) have stated “there is a tendency for the devel- opment of an opinion in society regarding which careers are considered suitable for Greeks and which for immigrants, simi- lar to the stereotypes regarding the men’s and women’s careers”. The highest proportions of foreign students appear in Secon- dary Vocational Education. According to the statistics of the Greek Ministry of Education2 for the academic year 2007-2008, a percentage of 12.8% of non-Greek students attended Voca- tional High Schools while the percentage of those attended General Education schools was only 4.3%. Secondary Voca- tional Education is provided by Vocational High Schools and Vocational Schools, and seeks to combine general education with technical vocational knowledge, in order to develop skills, initiative, creativity, and critical thinking of students. The cur- ricula of the Vocational High Schools include a limited number of general education courses, and a larger number of technical- professional and laboratory exercises. The main reasons of non- Greek students to continue their studies in vocational rather than general education are the following: a) there are only a few language courses in the curriculum of vocational schools and b) the degree of specificity allows access to the labor market with- out further studies (Skipitari-Vantsioti, 2011). The connection of Secondary Vocational Education with the labor market (if supported by governmental policies) will be crucial in address- ing the problem of unemployment. In accordance with the pro- visions of CEDEFOP3 on developments in the field of em- ployment in Greece, there will be a growth in jobs that need middle-level skills workers, such as the graduates of secondary vocational education. It should also be noted that in countries where Technical-Vocational education is widespread, the youth unemployment rate is lower. Finally, CEDEFOP emphasizes the need of assistance and rehabilitation programs for the guid- ance of students so that students can expand their options and capabilities. The Present Study The specific goals of the present study are to investigate the career beliefs of Greek and non-Greek Vocational Education students; and the effect of demographic variables (e.g. gender, immigrant status, parents’ educational level) in these beliefs. The findings of the present study should be regarded as a first stage exploratory attempt. We believe that the results may contribute to the understanding of students’ career development and decision-making process and have practice implications for the design of career guidance activities which focus on the spe- cific needs of Vocational Education students. Method Participants The present study consists of a total sample of 238 students who attend Greek Secondary Vocational Education schools in 2www.antigone.gr/en/stats/files/081101.pdf 3CEDEFOP (02/2011). Brief Note: “What next for skills in the Euro- ean Labour Market?” See also CEDEFOP (2010). Skills supply and demand in Europe: Medium-term forcast up to 2020. Publication Of- fice of the Euro ean Union. Luxembur . 1Christodoulou Theodoros (2009 June). Immigrants and Multicultural Education in Greece. Paper presented at the 12th International Confer- ence “Intercultural Education-Immigration-Conflict Management and Pedagogics of Democracy. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1242  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1243 the region of Attica. The sample comprises 184 (77.3%) male and 54 (22.7%) female respondents. The average age is 16.36 years (SD = 1.30). 165 participants (69.3%) are Greek, while 73 (30.7%) are immigrants. Regarding the participants’ parents educational level it was found that the majority has completed the nine years compul- sory education, whereas a large percentage consists of Univer- sity graduates and of Primary Education graduates (Table 1). Instrumentation Career beliefs were assessed by Career Beliefs Patterns Scale (2) (Arulmani & Nag, 2008), which is consisted of 32 vignettes. The items are representing as vignettes describing life situations and are designed to understand negative career beliefs among students. Responses are recorded on a 7 point Likert response continuum of I would not agree with this at all (1) to I agree completely (7). Seven factors are obtained from the factor ana- lysis of the CBPS, which are called Proficiency Beliefs, Control and Self-Direction Beliefs, Culture and Common Practice, Self- worth, Persistence Beliefs, Fatalism Beliefs Scale and Caste Beliefs Scale. Proficiency Beliefs Scale (8 items): The vignettes in this fac- tor appear to tap the respondent’s beliefs about the importance of acquiring qualifications and skills that enhance personal proficiency for an occupation before entering the world of work. They describe the willingness to submit to the rigors of a for- mal training programme and spend resources (time, effort and finances) to achieve the distinction of being formally quailfied as per the norms of their society. Control and Self-Direction Beliefs Scale (8 items): These items describe circumstances reflecting the individual’s sense of control over his or her life situation and orientation to di- recting his or her life. Mind-sets in this category are linked to the career aspirant’s belief that he or she could deal with the exigencies presented by life situations and the orientation to direct and take charge of the way in which his or her life pro- gresses. These vignettes reflect the confidence to manage the trajectory of one’s life. Culture and Common Practice (5 items): These items de- scribe culturally embedded attitudes to career preparation. They reflect common practice and unwritten norms that orient the people of a community and shape their career preparation be- haviour. Self-Worth (2 items): These items refer to beliefs related to personal ability for career preparation. The items reflect an overall orientation to being able to prepare for a career. The items also tap the respondents’ self-worth in relation to aca- demic performance and career preparation. Persistence Beliefs (3 items): The vignettes in this factor are reflecting the determination to work toward future career goals in spite of difficulties and barriers encountered during the pro- cess of career preparation. Beliefs within this category reflect the resolve to persevere with determination toward career goals. These items also reflect a sense of purposefulness and resolve to strive for positive outcomes in the future. To this end they reflect the quality of the respondent’s orientation to the future. Fatalism (4 items): The items portray a sense of resignation and a passive acceptance of one’s life situation. These vignettes are coloured by the feeling of pessimism and a sense that noth- ing can be changed and that matters are preordained by more powerful forces. Caste Beliefs (2 items): Caste by its very nature is based on occupational structures and hierarchies that are deeply embed- ded in India culture. It is possible that while a person from a “lower caste” may be able to break through the material disad- vantages inflicted by caste, socio-cultural forces may continue to influence mind sets which in turn could have an impact on career preparation. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to estimate the internal reliability of the seven sub scales, measured from 0.44 to 0.69 for each one of the 7 factors (Arulmani & Nag, 2008). Following a review of available career beliefs measures, the Career Beliefs Pattern Scale was selected to be translated into Greek and used. The selection was made based on the follow- ing theoretical and psychometric evidence: 1) In the present study we were interested to measure a num- ber of beliefs tapped by this instrument e.g. culturally embed- ded attitudes to career preparation, socio-cultural forces that in- fluence career beliefs. 2) Construction and standardization samples of CBPS in- cluded a number of 1253 students of vocational institutions, and the mean age of the total sample was 16.40 years. 3) CBPS is consisted of vignettes which are describing life situations and are designed to understand negative career be- liefs among students. The use of vignettes has been found to be a credible research device in situations when the re-creation of real life event is difficult (Wilson & While, 1998), while it seems to offer enjoyment and creativity for the informant (Schoenberg & Raydal, 2000). 4) As an alternative tool we studied the CBI (Krumboltz, 1991, 1999) and decided not to use it in the present research. Table 1. Frequencies of participants’ immigrant status and parents’ educational level. Father Mother Parents’ education level/ Immigrant status Greek Non-Greek Total Greek Non-Greek Total Primary Education 41 (25.3%) 18 (25.0%) 59 (25.2%) 29 (17.9%) 11 (15.1%) 40 (17%) Secondary Education 79 (48.8%) 33 (45.8%) 112 (47.9%) 100 (61.7%) 41 (56.2%) 141 (60%) University 28 (17.3%) 16 (22.2%) 44 (18.8%) 22 (13.6%) 14 (19.2%) 36 (15.3%) MSc/PhD 14 (8.6%) 5 (6.9%) 19 (8.1%) 11 (6.8%) 7 (9.6%) 18 (7.7%) Total 162 (69.2%) 72 (30.8%) 234 (100%) 162 (68.9%) 73 (31.1%) 235 (100%)  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Our skepticism had to do partly with the fact that many of the beliefs measured by this instrument were not of our scientific interest. Besides, concerns have been expressed regarding in- ternal consistency of some scales (AMECD Newsnotes, 1992; Dolenz, 1993; Fuqua & Newman, 1994; Turner, 2011), and suggestions have been done for reorganizing scales to improve reliability and validity (Dolenz, 1993; Fuqua & Newman, 1994). Also, it has been stated that it is not clear how beliefs are de- fined in the CBI framework (Walsh, 1994), and that it has not been established how the scale scores relate to career progress or development (Wall, 1994). In order for the instrument to correspond to the Greek educa- tional system and the Greek society structure we translated it into Greek and adapted several items. During this phase peri- odic e-mail communication between the translator and the au- thor of the English version were established. In a pilot study the translated CBPS was administered to a small sample of Greek (N = 10) and non-Greek (N = 10) vocational high school stu- dents to seek feedback on the meaning of the items. Based on the participants’ responses and general comments, further chan- ges were made to the CBPS. Procedure The Greek version of the CBPS was administered during regular class hours. Students were asked to read the instructions carefully and after the administration they had a short debrief- ing about the purpose of the study and were thanked for their participation. Results Exploratory factor analysis was conducted to categorize the scale’s items into larger homogeneous groups, in order to better describe the internal structure of the students’ responses. Factor analysis included 32 items for the 238 students. Principal Component Analysis with varimax rotation was used as extrac- tion method. Through repeated iterations, it was decided to dis- miss 4 items that did not fulfill the statistical conditions to be included in the factorial structure. The following criteria were used to determine the extraction of the factors: a) The Kaiser criterion indicating Eigen values greater than 1.0; b) Cattell’s scree test; c) The interpretability of the solution. The final solution for the 28 remaining items (having as the cut point loading the 0.35) revealed five (5) factors, to which 43.44% of the variance can be attributed. For this analysis ΚΜΟ = 0.79, χ² for the Bartlett’s test of sphericity = 1553.44 (df = 378, p < 0.001). All loadings of the measurements in the five factors based on this solution are presented in Table 2. The five factors can be described as following: Table 2. Results of the factor analysis for the 28 items of the Career Belief Patterns Scale. Factors Items 1 2 3 4 5 20. Some careers have a low status in society. I cannot choose such a career because this choice will upset my family and will affect other aspects of my life. 0.63 –0.05 0.06 0.04 0.08 21. Talent and career may not go together. I may be talented in something but my family and others may expect me to do something else. It is difficult for me to go against them. 0.60 0.21 0.10 –0.04 0.01 19. There are some careers a person cannot choose. For example a boy cannot become a nurse or a girl cannot become a carpenter. If I choose a career that is different from my friends, then I will be left out of the group. So it is best that I choose what others choose. 0.60 0.22 –0.00 0.02 0.01 22. I often make mistakes and I have many weaknesses. I think I make so many mistakes that I will not be able to be well prepared for my career. 0.55 0.01 0.28 0.24 –0.09 29. I cannot make a career choice that is completely different from what my family expects me to do.0.52 0.11 –0.21 0.32 0.12 18. Girls can get educated up to a certain level and then they have to stop. Their basic responsibility is their family. 0.48 0.31 –0.13 –0.05 0.11 15. E. lives in a village. In order for him/ her to prepare for his career E. has to go to the city. This movement is very difficult for him/her. So, E. won’t manage to get a good job. 0.45 0.24 0.27 0.12 0.02 17. Boys are better at earning a living and girls are better at taking care of the family. So career preparation is mainly for boys. 0.40 0.30 0.18 –0.18 0.29 6. In school we don’t learn much. So rather than studying for a long time, it is better to find a job and get work experience. That way we start learning the job and earning income quickly. 0.08 0.70 0.10 –0.05 0.01 2. Exams for entering University are too difficult for me to pass. So, it is better to try for a job without trying to pass these exams. 0.02 0.66 0.12 0.21 0.03 3. I can get a job after High School and earn almost 800 € per month. So there is no need for me to get a degree. 0.22 0.65 –0.01 0.13 –0,05 1. G. studied and got a degree. Nevertheless, G. still doesn’t have a job. Therefore studying after high school is no use. 0.00 0.57 0.21 0.17 –0.03 8. Studying is for certain kinds of people. If you are not that type of person it is better to stop your studies as soon as possible. 0.30 0.45 0.12 0.12 –0.06 5. F. failed in High School, but luckily he/ she got a job that pays him/ her well. Since F. has a job, there is no need for him/ her to try to complete High School. 0.30 0.44 –0.01 0.22 0.06 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1244  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Continued 13. Working hard is not enough. Luck and other factors are important. Without that success in life may not become a reality. –0.06 0.06 0.64 0.09 0.11 14. The responsibility to find a job is not mine alone. Society and the government must also give me opportunities and support me in my job and my welfare. –0.22 –0.04 0.62 –0.01 0.16 16. There are too many factors beyond my control that I have to take into consideration for the prepara- tion of my future career. I do not know what will happen in the future. So planning my career is too difficult for me. 0.22 0.12 0.55 –0.01 0.20 11. Many things are not in our control. I do not know what kinds of difficulties I may face if I pre are for a career. Therefore I may not be successful in planning my future career. 0.30 0.12 0.54 0.04 –0.00 10. All people may become rich through hard work. Nevertheless, a person originated from a family with low socioeconomic status will always face difficulties in getting accepted by society. 0.13 0.11 0.47 0.02 0.08 9. P. has the potential to do well. But he/ she comes from a very poor family, and his/ her father is an unqualified worker. Therefore, it would be very difficult for him/ her to build a secure future. 0.32 0.14 0.38 0.24 –0.16 24. S. joined an institute where he/ she is studying many subjects. If S. finishes, he/ she will get a goo job, but he/ she finds some of the subjects very difficult. S. feels it is too much for him and that he should drop out of the course. 0.16 0.19 –0.08 0.61 0.08 25. D. joined a course in basic computer skills for beginners. The course was hard and D. finds it boring. D. feels this course is not suitable for him/ her and is thinking of stopping. –0.12 0.13 0.17 0.61 0.17 26. E. has taken up a course that will give him/ her a good job. But after joining E. found that the course is taught in English. His/ her English is poor. So E. is thinking of dropping out of the course. 0.03 0.09 0.04 0.62 0.14 27. In my life there are many situations and factors beyond my control. Therefore I cannot think abou the future and my career. 0.37 0.01 0.13 0.58 –0.04 32. According to the law, no discrimination in the world of work is allowed. But this does not work in reality. Socioeconomic status plays a very strong role in career development. –0.02 –0.02 0.06 0.08 0.78 28. Life situations have such a strong impact in career choice that in reality we cannot “choose” ou careers. We can only take what is offered to us and do the best with that. 0.06 0.24 0.13 0.15 0.59 30. I have seen how others have tried to develop their lives. I realise that building a career is difficult. I think one should choose what he can and manage. –0.11 –0.22 0.22 –0.00 0.57 31. I think that the socioeconomic status of my family has a strong influence on my career development.0.25 0.01 0.08 0.18 0.54 Variance explained (total: 43.44%) 11.39% 10.24% 7.99% 7.08% 6.73% Internal Consistency Coefficients 0.75 0.73 0.63 0.60 0.60 1) Culture and Common Practice: This factor refers to career beliefs and to attitudes regarding career preparation that have been developed through society’s and culture’s unwritten norms and rules (e.g. gender issues: Girls can get educated up to a certain level and then they have to stop. Their basic re- sponsibility is their family). A high score in this factor indicates the great significance of these unwritten norms. 2) Proficiency Beliefs: This factor refers to a person’s beliefs regarding the necessity of acquiring qualifications and skills that will maximize his/her performance at work, or will allow him/her to search for a more suitable occupation (e.g. Exams for entering University are too difficult for me to pass. So, it is better to try for a job without trying to pass these exams). Peo- ple with high scores in this factor have great willingness to undertake the necessary training in order to acquire qualifica- tions and skills. 3) Control and Self Direction Beliefs: This factor refers to the level of the confidence to manage the trajectory of one’s life. Situations and experiences influence the direction that one’s life can take. The items in this Factor describe circumstances re- flecting the individual’s sense of control over his or her life situation and orientation to directing his or her life (e.g. Work- ing hard is not enough. Luck and other factors are important. Without that success in life may not become a reality). A high score in this factor indicates that the person feels that he/ she is in control of his/ her life. 4) Persistence Beliefs: This factor refers to the person’s de- termination to achieve his/her career goals and overcome all possible barriers and problems that will occur during career preparation (e.g. E. has taken up a course that will give him/ her a good job. But after joining E. found that the course is taught in English. His/ her English is poor. So E. is thinking of dropping out of the course). A high score in this factor indi- cates high level of determination to fulfill career goals and a sense of purposefulness. 5) Fatalism and Socioeconomic Status Impact: This factor refers to a passive attitude towards life, and a feeling of pessi- mism that nothing can be changed as everything is already pre- ordained. The factor also reflects the feeling that the person’s socioeconomic status has a major role in his career develop- ment and determines his career future (e.g. I think that the so- cioeconomic status of my family has a strong influence on my career development). A high score in this factor indicates that the person has a high level of pessimism and he/she attributes a great importance to his/her socioeconomic status regarding his/her career future. The estimated internal consistency coefficients of the afore- mentioned categories of CBPS were 0.75, 0.73, 0.63, 0.60 and 0.60 respectively. While in the original Indian version of CBPS “higher scores indicate higher negativity in the content of career beliefs” (Arulmani & Nag, 2008: p. 16), we have chosen to calculate the scores in each factor having in mind that higher scores will indicate higher degree of the particular characteristic (e.g. a Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1245  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. high score in the “Proficiency beliefs” subscale indicates great willingness to acquire qualifications and skills, a high score in the “Control and self-direction beliefs” subscale indicates that the person feels that he/ she is in control of his/her life, etc.). Subsequently, we tested for normality of the distributions using the K-S test in order to determine whether we should use parametrical criteria or not. All distributions were normal. We also calculated the mean scores and standard deviations of the five career beliefs factors (c). The minimum possible score in each category is 1 and represents low level of the factor while the maximum possible score is 7 and represents high level of the factor. Most of the factors had rather high scores. The highest score was on “Proficiency Beliefs” (M = 5.18, SD = 1.20). Subse- quently, quite high scores were achieved in “Persistency Be- liefs” (M = 4.79, SD = 1.22) and in “Control and Self-Direction Beliefs” (M = 4.32, SD = 1.11). Finally, the lowest scores were in “Fatalism and Socioeconomic Status Impact” (M = 4.09, SD = 1.28) and in “Culture and Common Practice” (M = 2.87, SD = 1.15). Two-way ANOVAs were used to assess the effects of both gender and immigrant status on career beliefs’ levels. The analyses comprised a 2 (gender: male vs female) × 2 (immi- grant status Greek vs Non-Greek) between-participants design with the career beliefs’ factors as dependent variables. The ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect for gender regarding “Culture & Common Practice” [F(1,234) = 6.89, p < 0.01]. Male students had significantly higher scores (M = 3.04, SD = 1.13) than female students (M = 2.31, SD = 1.03) in “Culture & Common Practice”. No significant gender main effects were found regarding the other career beliefs factors. Immigrant status had significant main effects in all career be- liefs factors. Greek students had significantly higher scores than immigrant students in “Proficiency Beliefs” [F(1,234) = 18.86, p < 0.001], “Control & Self Direction Beliefs” [F(1,234) = 13.08, p < 0.001], and “Persistency Beliefs” [F(1,234) = 4.63, p < 0.05]. They had lower scores than immigrant students in “Culture & Common Practice” [F(1,234) = 18.31, p < 0.001], and “Fatalism & Socioeconomic Status Impact” [F(1,234) = 6.72, p = 0.01]. Table 3 presents the F ratios, mean scores and standard deviations of career belief factors for the Greek and immigrant students. No significant interactions between gender and immigrant status were revealed. The correlations matrix between career beliefs factors scores, students’ age and parents’ educational level is displayed in Table 4. As expected, there are many low or medium but sig- nificant correlations between the factors (in the expected direc- tion). This is a supporting evidence for the factors’ independ- ence. Age is not correlated with any career belief factor. Finally, parents’ educational level is positively correlated with “Profi- ciency Beliefs” (r[father] = 0.22, p < 0.01, and r[mother] = 0.13, p < 0.05 ), but the correlation is quite low. Further analyses to examine parents’ educational level and career beliefs relation- ship separately for Greek and immigrant students revealed no significant correlations for immigrant students, while for Greek students there were: a) low positive significant correlation with “Proficiency Beliefs” (r[father] = 0.32, p < 0.001, and r[mother] = 0.24, p < 0.01) and b) low negative correlation between fa- ther’s level and “Culture and Common Practice” (r[father] = –0.22, p < 0.01). Discussion The results of our research suggest that the following five factors contribute to career beliefs of students who attend Sec- ondary Vocational Education schools in Greece: “Culture & Common Practice”, “Proficiency Beliefs”, “Control & Self Direction Beliefs”, “Persistence Beliefs”, “Fatalism & Socio- economic Status Impact”. Career Beliefs Patterns Scale (2) seems to be a reliable measure of negative career beliefs in the Greek context. There is a great coincidence of the factors found in the pre- sent study with the factors of the initial research in India. We can see that the original factors “Fatalism” and “Caste Beliefs” (proposed by CBPS authors) constitute a new factor which was labeled “Fatalism & Socioeconomic Status”. Additionally, the original factor “Self-Worth Beliefs” was not foundby the Factor Analysis. It should be mentioned that the original factors “Caste Beliefs” and “Self-Worth Beliefs” were comprised by only two Table 3. F ratios, mean scores and standard deviations for the five factors of CBPS for the Greek and immigrants students Factors Status N Mean Std. DeviationF df p Greek 165 2.59 1.04 Culture & Common Practice Immigrant 73 3.35 1.16 18.31 1, 234 <0.001 Greek 165 5.53 1.05 Proficiency Beliefs Immigrant 73 4.50 1.13 18.86 1, 234 <0.001 Greek 165 4.53 1.10 Control & Self Direction Beliefs Immigrant 73 3.90 1.03 13.08 1, 234 <0.001 Greek 165 4.94 1.20 Persistency Beliefs Immigrant 73 4.49 1.26 4.63 1, 234 <0.05 Greek 165 3.96 1.27 Fatalism & Socioeconomic Status Impact Immigrant 73 4.38 1.25 6.72 1, 234 0.01 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1246  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Table 4. Descriptive statistics and person correlations coefficients of career belief patterns, parents’ educational level, and age. M1 SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1. Culture and Common Practice 2.87 1.15 1 –0.54** –0.31** –0.33** 0.16** 0.03 –0.10 –0.02 2. Proficiency Beliefs 5.18 1.20 1 0.30** 0.35** –0.10 –0.01 0.22** 0.13* 3. Control and Self-Direction Beliefs 4.32 1.11 1 0.25** –0.30** –0.07 0.01 0.00 4. Persistence Beliefs 4.79 1.22 1 –0.25** –0.00 0.11 0.07 5. Fatalism and Socioeconomic Status Impact 4.09 1.28 1 0.10 –0.05 –0.09 6. Age 16.37 1.30 1 –0.09 –0.05 7. Father’s Educational Level 2.09 0.87 1 0.54** 8. Mother’s Educational Level 2.13 0.78 1 Notes: 1: Career Beliefs Factors: 1 = low level, 7 = high level, Educational level: 1 = Primary Education, 2 = Secondary Education, 3 = University/College, **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). vignettes and they had quite low reliability coefficients (0.44 and 0.46) (Arulmani & Nag, 2008). Despite the small differences in the factorial structure, the results of our research seem to be the most prominent and provide us the best description of the internal structure of the students’ responses. The factors “Proficiency Beliefs” and “Persistence Beliefs” were quite high for the students of the sample. High scores in “Proficiency Beliefs” shows students’ willingness to submit to the rigors of a formal training program and spend resources (time, effort and finances) to achieve the distinction of being formally qualified as per the norms of their society. Accord- ingly, high scores in “Persistence Beliefs” reflect a sense of purposefulness and resolve to strive for positive outcomes in the future. Therefore, our results suggest that a high proportion of students attending secondary vocational education in our country has understand the importance of obtaining certifica- tion and qualifications for entering the world of work and rec- ognizes the existence of difficulties due to learning, social, employment conditions, so as to adopt positive beliefs to ad- dress them. We should also highlight the quite low score in the “Culture and Common Practice” factor, which indicate that unwritten norms are of low significance for the students. Culturally em- bedded attitudes, such as gender issues, regarding career prepa- ration do not work very negatively for the students of our re- search orienting them to certain careers and shaping their career behavior4. Although immigrant students had a higher score than natives, their level of these dysfunctional thoughts was rela- tively low as well. The present research found also significant relationships be- tween students’ gender and the level of career beliefs’ factors. In “Culture and Common Practice” males reported higher scores than their female classmates. This means that in the aforementioned factors males revealed more negatives career beliefs to culturally embedded attitudes regarding career prepa- ration. Males seem harder to reject beliefs and practices on education and vocational rehabilitation that are considered cul- turally established in our country, compared with females. This comes as no surprise, considering that female students in voca- tional schools have already made a choice (attending vocational education) that seems to be the first major confrontation with the prevailing perception “describing” the sector of vocational education as more suitable for males. Greek students were found to have fewer negatives career beliefs than immigrant students. These differences existed in all the career beliefs factors. These findings may be associated with immigrant students’ adjustment difficulties to the demands of the Greek educational system, and difficulties of integration and acceptance by the entire educational community. Contem- porary studies indicate that the “immigrant status” is associated with the person’s self-perception, the way he/she understands his/her career opportunities, and his/her self-restricted beliefs (Drosos, 2011; Luzzo, 1993, Luzzo & McWhirter, 2001; McWhirter, 1997; Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2005; Sidiropoulou & Drosos, 2010). According to Gloria and Hird (1999) minority students might think that they will not be accepted in the world of work under the same terms with the majority students, al- though they may have the abilities and skills to successfully compete with them. There is a distinction between the career opportunities that a person has; and the career opportunities that he believes he has (Griffith, 1980). Our results are consistent with various researches in Greece and abroad. Luzzo (1993) reports that it is much more likely for African-Americans, Asian-Americans, Hispanic-Americans and Philippian-Americans to perceive their race as an obstacle to their career development in comparison to European-Americans. McWhirter (1997) found that Mexican-American students an- ticipated more barriers in their future careers than Euro- pean- Americans. According to Luzzo and McWhirter (2001) minor- ity populations not only anticipate more obstacles, but they also have less self-efficacy beliefs regarding their ability to surpass them. Finally, recent researches in Greece found that immigrant students have lower levels of self-efficacy (Motti-Stefanidi et al., 2005) and report a higher level of dysfunctional career thoughts (Drosos, 2011; Sidiropoulou & Drosos, 2010) than their native classmates. Finally, a significant relationship was revealed between par- ents’ educational level and “Proficiency Beliefs” for Greek students, suggesting that parents with higher education level convey positive values to their children, which estimate educa- 4It should be noted that female students scored lower than their male classmates. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1247  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. tion as an important factor of personal and career development. However the correlation was rather low, while no such correla- tion was found for immigrant students. Other findings have highlighted the important role that parents play in the career beliefs of Greek (Gari, 1993; Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, My- lonas, & Argyropoulou, 2003) and non-Greek students (Sidi- ropoulou-Dimakakou, Argyropoulou, Mylonas, & Besevegis, 2008). Further research is necessary for a better understanding of the relationship between the family’s educational status and career beliefs. Implications for Career Counselors in School Settings Career counsellors and school vocational guidance practitio- ners have the duty to help individuals who are less fortunate and thus socially excluded by virtue of who they are, where they are, or some combination thereof to overcome hopeless- ness and lack of motivation based on perceived lack opportuni- ties and power, as well as perceived personal inadequacies and lack of confidence (Blustein, 2001, 2006). As noted above, ca- reer counseling that address career beliefs could create a plat- form upon which young people approach career decisions mak- ing and planning in a more proactive manner (Arulmani, Van Laar, & Easton, 2003). Initially, career counselors are necessary to assist the individual to be creative in finding alternative pathways to achieve important goals. The present research has indicated that investigations into social-cognitive variables such as career beliefs could play a vital role in redefining the practice of career guidance in Greek society. Nevertheless, a wide study regarding the relationship of various socio-economic factors (such as unemployment, eco- nomic crisis, performance, employment opportunities) and ne- gative career beliefs could help us to improve more the career counseling services in the shadow of the recent economic crisis that has hit Greece. Limitations of the Study This study is not without limitations. First, all the data were collected by self-report scales; and this may raise issues re- garding the truthfulness of the responses. Second, results of this study cannot be generalized to all vocational education students due to the small sample, and to the fact that all schools were selected from within a specific district. Additionally, the use of parents’ educational level as an indicator of the student’s so- cioeconomic status is not an efficient way of measuring the specific variable, although it is widely used. Another weakness may be that immigrant students were considered as one homo- geneous group, despite the fact they originated from different countries. The small size of the sample did not allow us to ex- amine differences between the various countries, but further research is needed. Conclusion Regarding the present study’s aims, the results provide us a quite interesting image of the vocational education students’ career beliefs. Despite the above limitations, the findings could help career counselors who work with vocational education students in better understanding their clients’ career develop- ment and decision making difficulties. Career beliefs may be associated with various other variables, e.g. students’ school grades, students’ career aspirations, personality characteristics, etc.; and more research is necessary to guide career intervention efforts for these students. Future research should also examine further discrepancies in career development among immigrant students as means of beginning to address inequities. REFERENCES Amundson, N. (1997). Myths, metaphors and moxie: The 3M’s of career counselling. Journal of Employment Counseling, 34, 76-84. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1920.1997.tb00461.x Arulmani, G., & Nag, S. (2008). The career belief patterns scale (Ver- sion 2). Bangalore: The Promise Foundation. Arulmani, G., Van Laar, D., & Easton, S. (2003). The influence of ca- reer beliefs and socio-economic status on the career decision making of high school students in India. The International Journal for Edu- cational and Vocationa l Guidance, 3, 204-220. doi:10.1023/B:IJVO.0000006599.92116.0a Association for Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and De- velopment (1992). CSCGI: Career beliefs inventory. AMECD News- notes, 27, 7-11 Austin, R. K., Wagner, B., & Dahl, D. (2003). Reducing negative ca- reer thoughts in adults. International Journal of Disability Commu- nity and Rehabilitation, 2. http://www.ijdcr.ca/VOL02_02_CAN/articles/austin.shtml Blustein, D. L. (2001). Extending the reach of vocational psychology. Toward an inclusive and integrative psychology of working. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 171-182. doi:10.1006/jvbe.2001.1823 Blustein, D. L. (2006). The psychology of working: A new perspective for career development, counseling, and public policy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1996). A social cognitive framework for career choice counseling. The Career Development Quarterly, 44, 354-366. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00451.x Cameron, R. (2009). Theoretical bridge building: The career develop- ment project for the 21st century meets the new era of human re- source development. Australian Journal of Career Development, 18, 9-17. CEDEFOP (2011). Brief Note: “What next for skills in the European labour market?” Thessaloniki: CEDEFOP. CEDEFOP (2010). Skills supply and demand in Europe: Medium-term forecast up to 2020. Luxemburg: Publication Office of the European Union. Chartrand, J. M., & Rose, M. L. (1996). Career interventions for at-risk populations: Incorporating social cognitive influences. The Career Development Quarterly, 44, 341-354. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1996.tb00450.x Clarkson, P. (2003). How to overcome your secret fear of failure. Lon- don: Vega. Corbishley, M. A., & Yost, E. B. (1989). Assessment and treatment of dysfunctional cognitions in career counseling. Career Planning and Adult Development Journal, 5, 20-26. Christodoulou, T. (2009). Immigrants and multicultural education in Greece. 12th International Conference on Intercultural Education- Immigra- tion-Conflict Management and Pedagogics of Democracy. Patras, 19-21 June. [In Greek] Dolenz, B. (1993). The career beliefs inventory: A review and critique. Annual Meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association. Austin, TX, 28-30 January 1993. Drosos, N. (2007). Career maturity and career aspirations of Greek and non-Greek 9th grade students who attend Greek schools. Review of Counseling and Guidance, 80-81, 82-98. [In Greek] Drosos, N. (2011). Career maturity and career decision making of adolescents from different cultural backgrounds. Ph.D. Thesis, Ath- ens: University of Athens. [In Greek] Drosos, N. & Kassotaki, F. (2005). Educational and career choices of Greek and non-Greek students who attend Greek schools in relation with their self-esteem and their country of origin. Review of Coun- seling and Guidance, 7 2-73, 47-62. [In Greek] Dryden, W. (1999). Rational emotive behavior therapy: A training ma- nual. New York: Springer. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1248  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Fisher, T. A., & Padmawidjaja, I. (1999). Parental influences on career development perceived by African American and Mexican American college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Develop- ment, 27, 136-152. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.1999.tb00220.x Frost, R. O., & Marten, P. A. (1990). Perfectionism and evaluative threat. Cognitive Therapy and R esearch, 14, 559-572. doi:10.1007/BF01173364 Fuqua, D., & Newman, J. (1994). An evaluation of the career beliefs inventory. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72, 429-430. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb00963.x Gari, A. (1993). Attitudes and opinions of students in Greece on edu- cational institutions and educational and career decisions. Ph.D. Thesis, Athens: University of Athens. [In Greek] Gloria, A., & Hird, J. (1999). Influences of ethnic and non-ethnic vari- ables on career decision self-efficacy of college students. The Career Development Quarterly, 48, 157-174. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1999.tb00282.x Griffith, A. R. (1980). Justification for a black career development. Counselor Education and S u per vis ion, 19, 301-309. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.1980.tb01629.x Juntunen, C. L., Barraclough, D. J., Broneck, C. L., Seibel, G. A., Win- row, S. A., & Morin, P. M. (2001). American Indian perspectives on the career journey. Journal of Counseling Psycho lo gy , 48, 274-285. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.48.3.274 IPODE (2009). Distribution data of immigrant and repatriated students in Greek schools. Athens: Institute for Intercultural Education (Insti- touto Paideias Omogenon kai Diapolitismikis Ekpaidefsis-IPODE). [In Greek] Keller , K. E., Biggs, D. A., & Gysbers , N. C. (1982). Career counsel- ing from a cognitive perspective. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60, 367-371. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4918.1982.tb00689.x Krumboltz, J. D. (1990). Helping clients change dysfunctional career beliefs. The Annual Meeting of the American Association of Coun- seling and Development. Cincinnati, OH. Krumboltz, J. D. (1991). Manual for the career beliefs inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press. Krumboltz, J. D. (1994). Improving career development theory from a social learning perspective. In M. L. Savickas, & R. L. Lent (Eds.), Convergence in career development theories. Palo Alto, CA: CPP Books. Krumboltz, J. D. (1999). Career beliefs inventory: Applications and te- chnical guide. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press. Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45, 79-122. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027 Luzzo, D. A. (1993). Career decision-making differences between tra- ditional and nontraditional college students. Journal of Career De- velopment, 20, 113-120. Luzzo, D. A., & McWhirter, E. H. (2001). Sex and ethnic differences in the perception of education and career-related barriers and levels of copying efficacy. Journal of Counseling and Development, 79, 61-67. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2001.tb01944.x McWhirter, E. H. (1997). Perceived barriers to education and career: Ethnic and gender differences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 124-140. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1995.1536 Mitchell, L. K. & Krumboltz, J. D. (1996). Krumboltz’s learning theory of career choice and development. In D. Brown, & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Mitchell, A. M., Jones, G. B., & Krumboltz, J. D. (1996). Social learn- ing and career decision m a k in g. Cranston, RI: Carroll Press. Misra, G., & Jain, U. (1988). Achievement cognitions in deprived groups: An attributional analysis. Indian Journal of Current Psychological Research, 3, 45-54. Motti-Stefanidi, F., Pavlopoulos, V., Takis, N., Ntalla, M., Papathana- siou, A.-H., & Masten, A. S. (2005). Hardiness and self-efficacy ex- pectations: A survey among immigrant and repatriated adolescents. Psychology, 12, 349-367. [In Greek] Motti-Stefanidi, F., Pavlopoulos, V., Obradovic, J., Dalla, M., Takis, N., Papathanasiou, A., & Masten, A. (2008a). Immigration as a risk fac- tor for adolescent adaptation in Greek urban schools. European Jour- nal of Developmental Psychology, 5, 235-261. doi:10.1080/17405620701556417 Motti-Stefanidi, F., Pavlopoulos, V., Obradovic, J., & Masten, A. (2008b). Acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents in Greek ur- ban schools. Internat i o n a l Journal of Psychology, 43, 45-48. doi:10.1080/00207590701804412 Nathan, R., & Hill, L. (2006). Career counseling. London: Sage. Nevo, O. (1987). Irrational expectations in career counseling and their confronting arguments. The Career Development Quarterly, 35, 239- 250. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.1987.tb00918.x Papadopoulou, P. (2005). The profile of students of senior high schools’ students with high rates of immigrants-repatriated students, investi- gation of educational-occupational choices after the end of compul- sory education. The role of career guidance and counseling. Thesis, Athens: University of Athens. [In Greek] Perrone, K. M., Sedlacek, W. E., & Alexander, C. M. (2001). Gender and ethnic difference in career goal attainment. Career Development Quarterly, 50, 168-178. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2001.tb00981.x Peterson, G. W., Sampson, J. P., & Reardon, R. C. (1991). Career de- velopment and services: A cognitive approach. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Roll, T., & Arthur, N. (2002). Beliefs in career counselling. Calgary: University of Calgary. Santos, P. J. (2001). Predictors of generalized indecision among Portu- guese secondary school students. Journal of Career Assessment, 9, 381-396. doi:10.1177/106907270100900405 Saunders, D., Peterson, G., Sampson, J., & Reardon, R. (2000). Rela- tion of depression and dysfunctional career thinking to career indeci- sion. Journal of Vo ca t io na l Behavior, 56, 288-298. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1999.1715 Schoenberg, N. E., & Ravdal, H. (2000). Using vignettes in awareness and attitudinal research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3, 63-74. doi:10.1080/136455700294932 Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D. (2003). Career counseling and cultural di- versity. Psychology, 10, 399-413. [In Greek] Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Mylonas, K., & Argyropoulou, K. (2003). Opinions of adolescents on the influence of parents on their pro- fessional choices. Review of Counselling and Guidance, 64-65, 95- 108. [In Greek] Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Argyropoulou, K., & Drosos, N. (2008). Inclusion of students with different cultural backgrounds in the edu- cational society: Teachers’ and counselors’ skills and special exer- cises. “Respect to Diversity” Conference of Career Counseling & Guidance Centre (KESYP) of Arcadia. Tripoli. [In Greek] Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Argyropoulou, K., Mylonas, K., & Be- sevegis, E. G. (2008). Individual differences in career choices among foreign high school students: The role of identity and career decision making. 1st Panhellenic Conference of Developmental Psychology. Athens, 29 May-1 June 2008. Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., & Drosos, N. (2010). Career decision making and career maturity of culturally diversed adolescents: A pi- lot survey among 9th grade students. Review of Counselling and Gui- dance, 92-93, 122-136. [In Greek] Skipitari-Vantsioti, E. (2011). Difficulties in career decision making of Greek and immigrants students of professional high schools in the framework of school career counseling. Review of Counselling and Guidance, 94-95, 293-295. Stewart, M., Anderson, J., Beiser, M., Mwakarimba, E., Neufeld, A., Simich, L., & Spitzer, D. (2008). Multicultural meanings of social support among immigrants and refugees. International Migration, 46, 123-159. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00464.x Thompson, A. P. (1976). Client misconceptions in vocational coun- seling. The Pers o n n e l an d G u i d a n ce Journal, 54, 30-33. doi:10.1002/j.2164-4918.1976.tb04607.x Trusty, J. (2002). Counseling for career development with persons of color. In S. Niles (Ed.), Adult career development: Concepts, issues, and practices. Tulsa, OK: National Career Development Association. Turner, S. L. (2011). The career beliefs of inner-city adolescent. Pro- fessional School Counseling. http://www.readperiodicals.com/201110/2501924721.html Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1249  D. SIDIROPOULOU-DIMAKAKOU ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 1250 Wall, J. (1994). Career interest inventory. In J. K. Kapes, M. M. Mastie, & E. A. Whifield (Eds.), A counselor’s guide to career assessment instruments (3rd ed., pp. 254-257). Alexandria, VA: NCDA. Walsh, W. B. (1994). The Career beliefs inventory: Reactions to Krum- boltz. Journal of Counseli nd and Development, 72, 431. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb00964.x Wilson, J., & While, A. E. (1998). Methodological issues surrounding the use of vignettes in qualitative research. Journal of Interprofes- sional Care, 12, 79-87. doi:10.3109/13561829809014090

|