Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

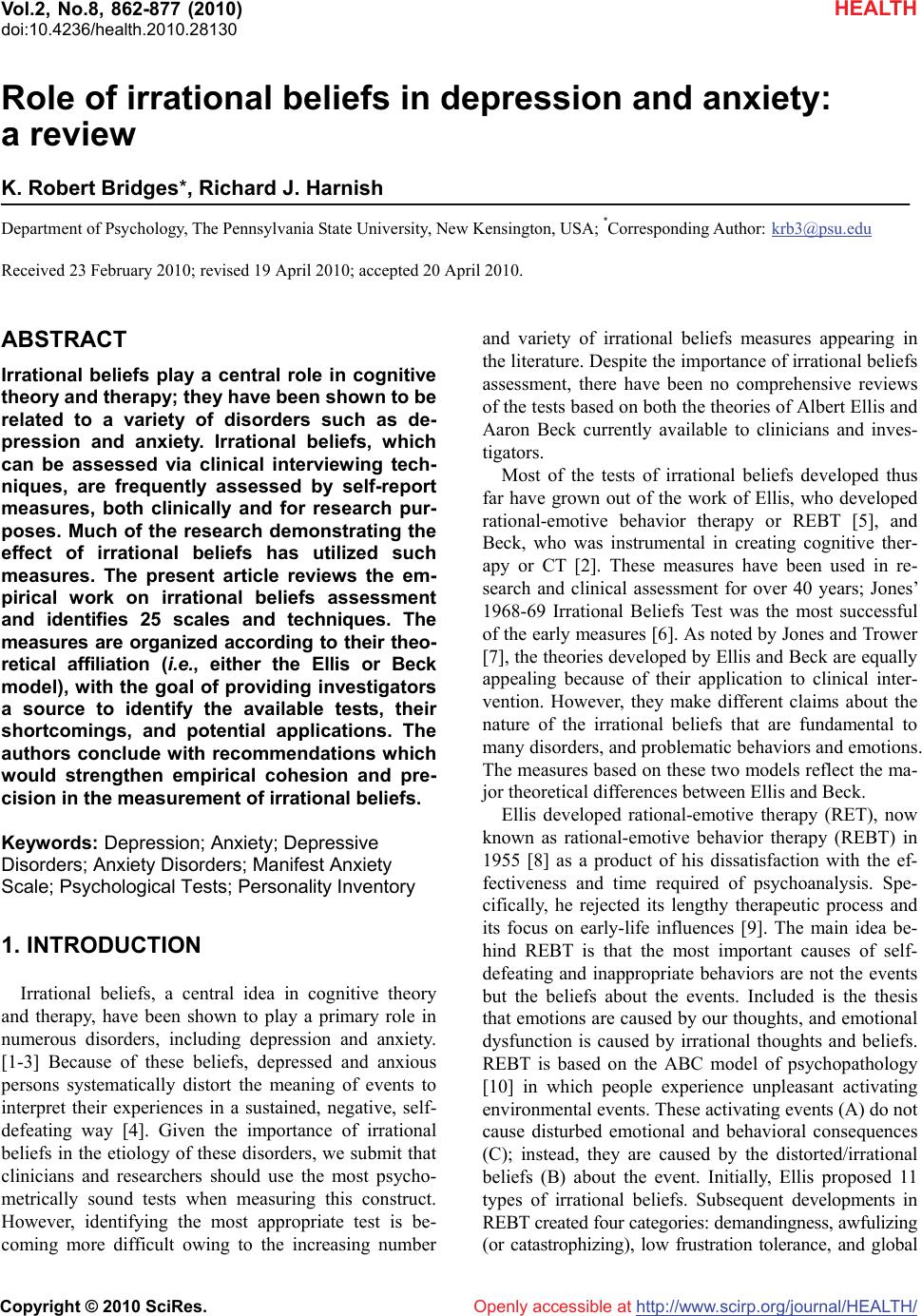

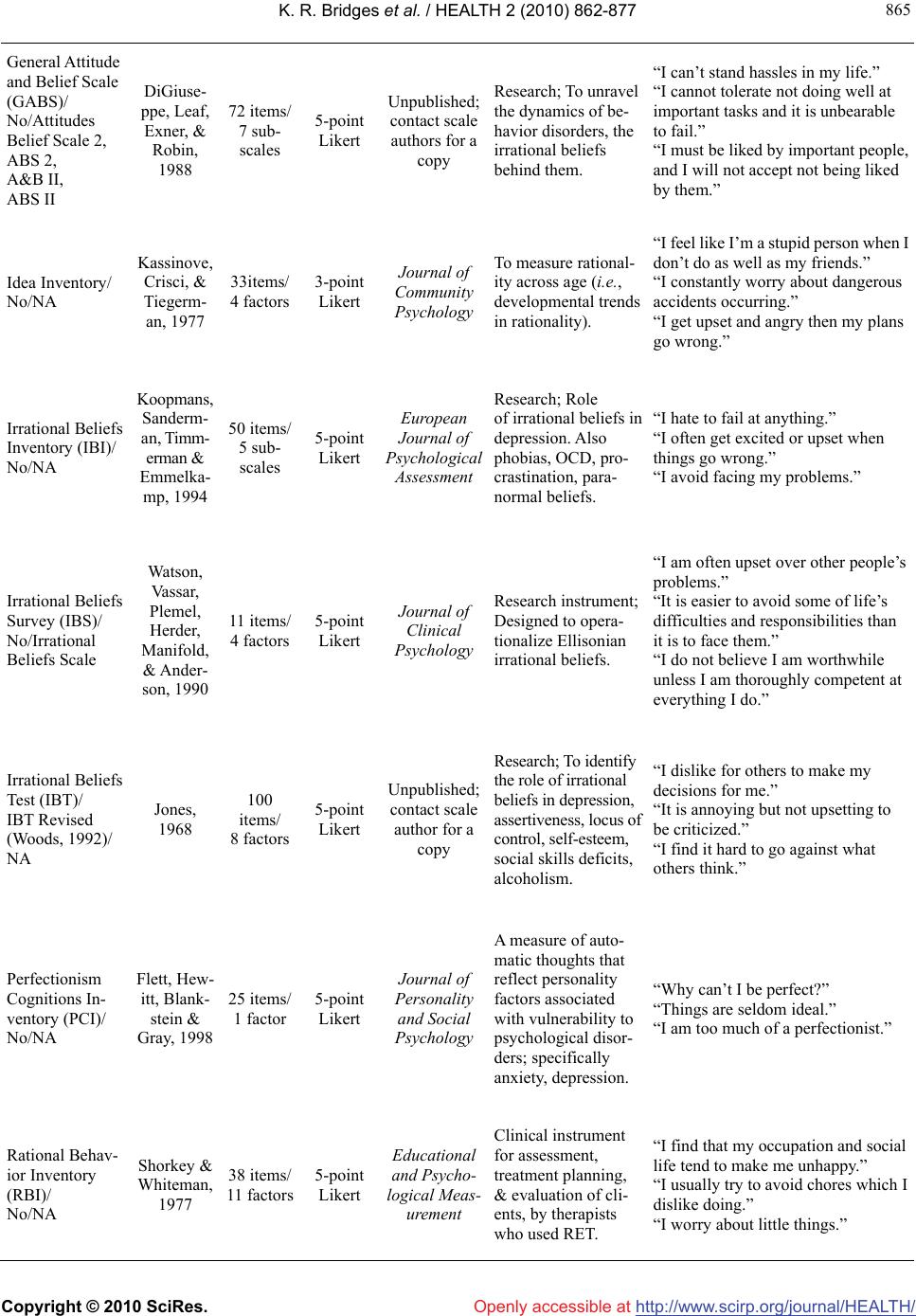

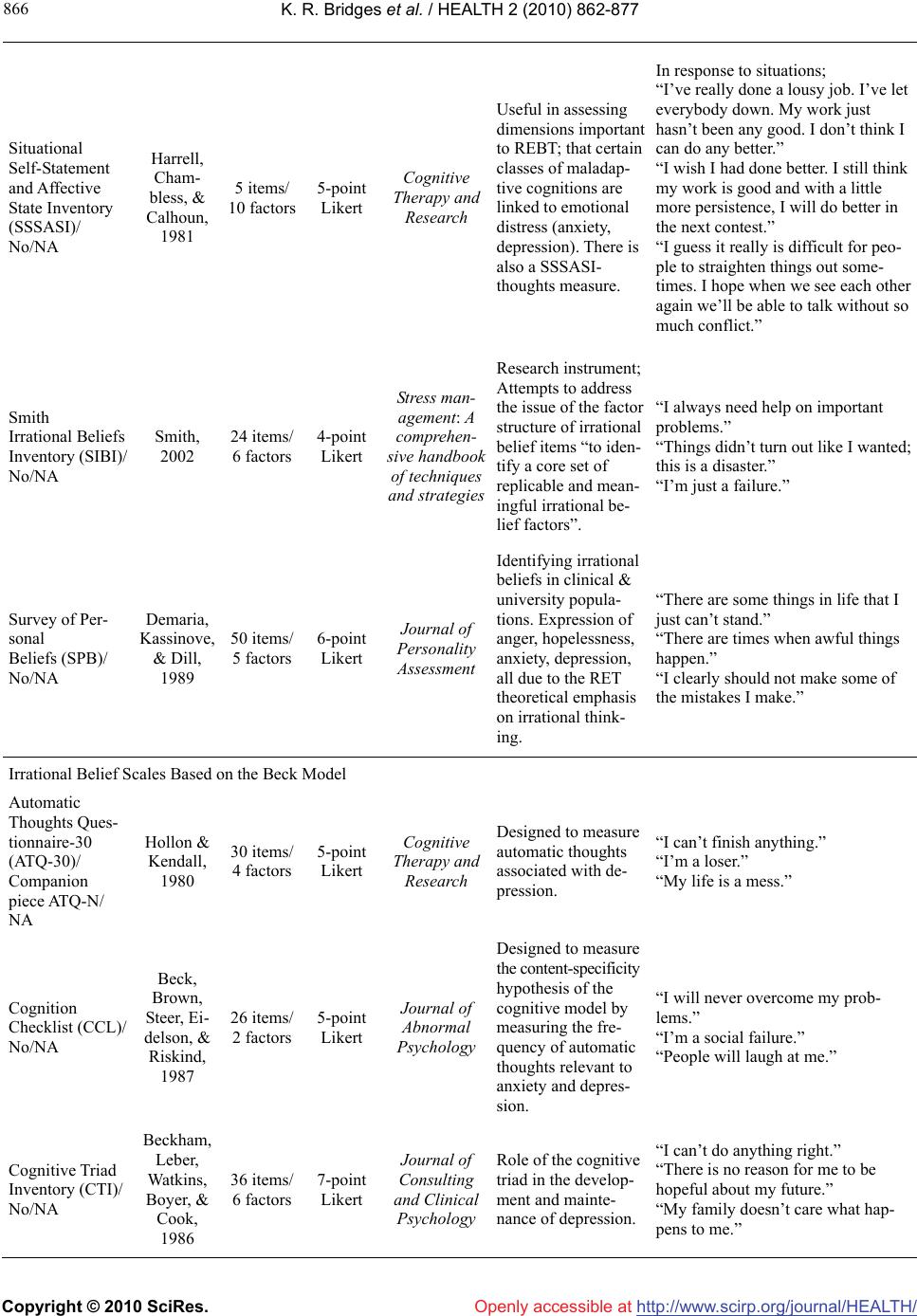

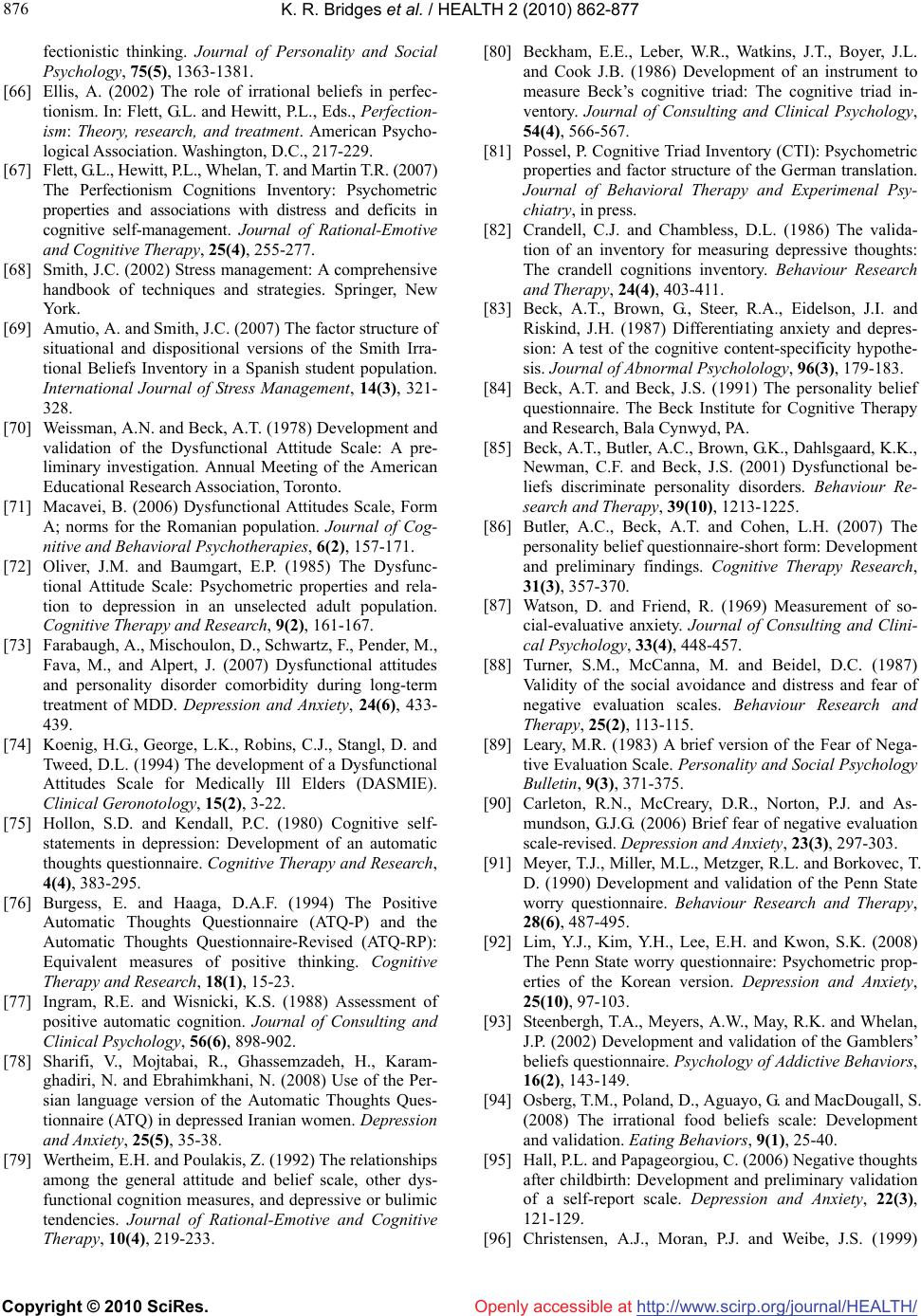

Vol.2, No.8, 862-877 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.28130 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ HEALTH Openly accessible at Role of irrational beliefs in depression and anxiety: a review K. Robert Bridges*, Richard J. Harnish Department of Psychology, The Pennsylvania State University, New Kensington, USA; *Corresponding Author: krb3@psu.edu Received 23 February 2010; revised 19 April 2010; accepted 20 April 2010. ABSTRACT Irrational beliefs play a central role in cognitive theory and therapy; they have been shown to be related to a variety of disorders such as de- pression and anxiety. Irrational beliefs, which can be assessed via clinical interviewing tech- niques, are frequently assessed by self-report measures, both clinically and for research pur- poses. Much of the research demonstrating the effect of irrational beliefs has utilized such measures. The present article reviews the em- pirical work on irrational beliefs assessment and identifies 25 scales and techniques. The measures are organized according to their theo- retical affiliation (i.e., either the Ellis or Beck model), with the goal of providing investigators a source to identify the available tests, their shortcomings, and potential applications. The authors conclude with recommendations which would strengthen empirical cohesion and pre- cision in the measurement of irrational beliefs. Keywords: Depression; Anxiety; Depressive Disorders; Anxiety Disorders; Manifest Anxiety Scale; Psychological Tests; Personality Inventory 1. INTRODUCTION Irrational beliefs, a central idea in cognitive theory and therapy, have been shown to play a primary role in numerous disorders, including depression and anxiety. [1-3] Because of these beliefs, depressed and anxious persons systematically distort the meaning of events to interpret their experiences in a sustained, negative, self- defeating way [4]. Given the importance of irrational beliefs in the etiology of these disorders, we submit that clinicians and researchers should use the most psycho- metrically sound tests when measuring this construct. However, identifying the most appropriate test is be- coming more difficult owing to the increasing number and variety of irrational beliefs measures appearing in the literature. Despite the importance of irrational beliefs assessment, there have been no comprehensive reviews of the tests based on both the theories of Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck currently available to clinicians and inves- tigators. Most of the tests of irrational beliefs developed thus far have grown out of the work of Ellis, who developed rational-emotive behavior therapy or REBT [5], and Beck, who was instrumental in creating cognitive ther- apy or CT [2]. These measures have been used in re- search and clinical assessment for over 40 years; Jones’ 1968-69 Irrational Beliefs Test was the most successful of the early measures [6]. As noted by Jones and Trower [7], the theories developed by Ellis and Beck are equally appealing because of their application to clinical inter- vention. However, they make different claims about the nature of the irrational beliefs that are fundamental to many disorders, and problematic behaviors and emotions. The measures based on these two models reflect the ma- jor theoretical differences between Ellis and Beck. Ellis developed rational-emotive therapy (RET), now known as rational-emotive behavior therapy (REBT) in 1955 [8] as a product of his dissatisfaction with the ef- fectiveness and time required of psychoanalysis. Spe- cifically, he rejected its lengthy therapeutic process and its focus on early-life influences [9]. The main idea be- hind REBT is that the most important causes of self- defeating and inappropriate behaviors are not the events but the beliefs about the events. Included is the thesis that emotions are caused by our thoughts, and emotional dysfunction is caused by irrational thoughts and beliefs. REBT is based on the ABC model of psychopathology [10] in which people experience unpleasant activating environmental events. These activating events (A) do not cause disturbed emotional and behavioral consequences (C); instead, they are caused by the distorted/irrational beliefs (B) about the event. Initially, Ellis proposed 11 types of irrational beliefs. Subsequent developments in REBT created four categories: demandingness, awfulizing (or catastrophizing), low frustration tolerance, and global  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 863 863 evaluation (or self-downing) [11]. The core irrational belief in REBT is demandingness [12]. It refers to absolutistic requirements expressed in terms of “must’s”, “have to’s”, “ought’s”, and “should’s”. The other beliefs include: awfulizing beliefs, which refer to the evaluation of a bad event as worse than it should be; low frustration tolerance, the belief that it is not pos- sible to bear certain circumstances (which makes a situa- tion intolerable); and global evaluation, which describes pervasive negative ratings about the world and oneself. These four irrational beliefs are considered to be the fundamental etiological factors in emotional and behav- ior disorders. Like Ellis, Beck [13] was disenchanted with psycho- analysis and developed another version of the ABC model. Beck, who was instrumental in creating cognitive therapy (CT), believed that many disorders are produced and maintained by negative beliefs and thinking styles that people have about themselves, their circumstances, and their future. Such cognitive errors include a belief in excessive personal causality for negative events and the belief that the worst possible outcome is the most likely. These cognitive distortions guide a person’s interpreta- tion of new experiences and increase the likelihood of behavior disorders. For Beck, negative life events acti- vate this cognitive triad of irrational beliefs: negative be- liefs about oneself (“I’m not good enough.”), the world (“This is an awful place.”), and the future (“Something bad will always happen.”). These irrational beliefs are activated by negative life events and produce systematic errors in thinking. The most frequent errors include “all or nothing” thinking (the tendency to view the event in only two ways, versus a continuum), arbitrary inference (a predisposition to reach negative conclusions without supporting evidence), selective abstraction (the tendency to pay attention to one negative detail as opposed to the whole picture), magnification/minimization (unreasona- bly minimizing the positive and maximizing the negative when evaluating a situation), and labeling (globally evaluating things negatively while dismissing any evi- dence that supports a less extreme view). While the theories of Beck and Ellis share fundamen- tal ideas about the basic reasons for psychological dis- orders (i.e., Ellis and Beck proposed therapies that are a mixture of cognitive and behavior therapy, both use an ABC model that posits dysfunctional cognitions cause psychopathology, and that such cognitions are distorted, inaccurate or irrational), slight differences emerge be- tween the two. Specifically, the theories make different claims about the nature of irrational beliefs that are fun- damental to the development of many disorders [5]. For Ellis, psychopathology is due to repeated focusing on distress-producing thoughts (e.g., I should be liked by everyone), while Beck proposed psychopathology is caused by illogical thought processes (e.g., all or nothing thinking). That is Ellis’ theory seems to be more focused on the particular thoughts that cause emotional distress; whereas, Beck’s theory seems to be more focused on the thought processes themselves that produce emotional upset. (See Dryden and Ellis [5] for a more detailed analysis of these differences.). The two theories have generated numerous measures of irrational beliefs. Some of the tests of irrational be- liefs generated by these theories have been widely used and have undergone numerous revisions, while others have seen only limited use. What follows is a review of 25 measures of irrational beliefs from their date of in- ception, including their theoretical affiliation, evidence of their reliability and validity, and their revision history. 2. METHOD 2.1. How the Measures Were Selected To identify the measures to be included in this review, a literature search was performed on PsycINFO, an elec- tronic database of the psychological literature that spans work published from the 1800s to the present. PsycINFO searches included such terms as “measures of irrational thoughts”, “thinking”, “cognitions”, and “beliefs”. Once articles were identified, we narrowed our review through the following criteria: 1) the measure was published or completed after 1968, when the Irrational Beliefs Test [14], noted earlier as the most successful early test, first appeared; 2) the measure, along with a scoring key, was readily available; and 3) the measure was written in English or had an English language version available. Of the 31 articles describing an irrational belief measure we found, six were eliminated based on our aforementioned criteria resulting in a review of 25 measures. See Table 1 for an alphabetical list of measures reviewed, including their authors, type of scale or response, and sample items. Below in the body of the text, the measures are pre- sented in their chronological order. In Table 1, the measures are presented in alphabetical order so that in- vestigators may readily locate the measures reviewed. 2.2. Evaluation Criteria For each measure of irrational beliefs, we evaluated and reviewed the measure’s reliability and validity. Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure while validity refers to how well a test measures the characteristics it claims to measure. We rated measures that possessed a reliability coefficient of 0.90 or higher as excellent, those with a reli- ability coefficient of 0.80 to 0.89 as very good, those with a reliability coefficient of 0.70 to 0.79 as good, and those with a reliability coefficient of 0.60 to 0.69 as suspect.  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 864 Table 1. Description of Irrational Belief Scales. Name of Scale/Other Forms/Also Known As Author(s) Number of Items/ Number of Fators or Sub- scales Rating Scale Source Original Purpose Sample Items Irrational Belief Scales Based on the Ellis Model Belief Scale (BS)/No/ M.S. Belief Scale, MSBS, Irrational Belief Scale, IBS Malouff & Schutte, 1986 20 items/ 1 factor 5-point Likert Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Depression, neuroti- cism. “It is terrible when things do not go the way I would like.” “Life should be easier than it is.” “To be happy, I must maintain the approval of all the persons I consider significant.” Camatta & Na- goshi Scale/No/ NA Camatta & Nagoshi, 1995 10 items/ Not re- ported Not re- ported Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research Research; Predictor of alcohol use problems. “It is awful and catastrophic when things are not the way I’d like them to be.” “I have little or no ability to control the sorrows and disturbances in my life.” “Some people are wicked and should be severely blamed and punished for their wickedness.” Child and Ado- lescent Scale of Irrationality (CASI)/ Short form (CASI- Revised)/ NA Bernard & Laws, 1987 44 items/ 6 sub- scales 5-point Likert Journal of Cognitive Psychother- apy: An In- ternational Quarterly Emotional problems; Anxiety, depression in younger popula- tions. “I can’t stand having to behave well and follow rules.” “It’s really awful to have lots of homework to do.” “Teachers should really act fairly all the time.” Common Beliefs Survey-III (CBS-III)/ Short form Ex- ists (CBS-II SF)/ NA Bessai, 1977 54 items/ 9 sub- scales 5-point Likert Unpublished; contact scale author for a copy Clinical instrument to distinguish clients from non-clients (clinical population not identified); Anxi- ety, depression. “There is a right way to do every- thing.” “Being approved by others is very important.” “A person can’t help feeling guilty about wrongdoings.” Ellis Emotional Efficiency In- ventory (EEEI)/ No/NA Ellis, 1992 60 items/ 3 factors 5-point Likert Question- naire: The elegant solu- tion to emo- tional and behavioral problems Designed to measure an individual’s abil- ity to cope with emo- tional dysfunction associated with awfu- lizing, ego-disturbance and discomfort dis- turbance. “I often pity myself when people treat me unfairly.” “I am quite pessimistic and often see things in a bad or hopeless light.” “I often feel insulted and embar- rassed.” Evaluative Be- liefs Scale (EBS)/No/ NA Chadwick, Trower, & Dagnan, 1999 18 items/ 3 factors 5-point Likert Cognitive Therapy and Research Research; Nature of evaluative beliefs in individuals with anger disorders. “I am a total failure.” “People think I’m a bad person.” “Other people are worthless.”  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 865 865 General Attitude and Belief Scale (GABS)/ No/Attitudes Belief Scale 2, ABS 2, A&B II, ABS II DiGiuse- ppe, Leaf, Exner, & Robin, 1988 72 items/ 7 sub- scales 5-point Likert Unpublished; contact scale authors for a copy Research; To unravel the dynamics of be- havior disorders, the irrational beliefs behind them. “I can’t stand hassles in my life.” “I cannot tolerate not doing well at important tasks and it is unbearable to fail.” “I must be liked by important people, and I will not accept not being liked by them.” Idea Inventory/ No/NA Kassinove, Crisci, & Tiegerm- an, 1977 33items/ 4 factors 3-point Likert Journal of Community Psychology To measure rational- ity across age (i.e., developmental trends in rationality). “I feel like I’m a stupid person when I don’t do as well as my friends.” “I constantly worry about dangerous accidents occurring.” “I get upset and angry then my plans go wrong.” Irrational Beliefs Inventory (IBI)/ No/NA Koopmans, Sanderm- an, Timm- erman & Emmelka- mp, 1994 50 items/ 5 sub- scales 5-point Likert European Journal of Psychological Assessment Research; Role of irrational beliefs in depression. Also phobias, OCD, pro- crastination, para- normal beliefs. “I hate to fail at anything.” “I often get excited or upset when things go wrong.” “I avoid facing my problems.” Irrational Beliefs Survey (IBS)/ No/Irrational Beliefs Scale Watson, Vassar, Plemel, Herder, Manifold, & Ander- son, 1990 11 items/ 4 factors 5-point Likert Journal of Clinical Psychology Research instrument; Designed to opera- tionalize Ellisonian irrational beliefs. “I am often upset over other people’s problems.” “It is easier to avoid some of life’s difficulties and responsibilities than it is to face them.” “I do not believe I am worthwhile unless I am thoroughly competent at everything I do.” Irrational Beliefs Test (IBT)/ IBT Revised (Woods, 1992)/ NA Jones, 1968 100 items/ 8 factors 5-point Likert Unpublished; contact scale author for a copy Research; To identify the role of irrational beliefs in depression, assertiveness, locus of control, self-esteem, social skills deficits, alcoholism. “I dislike for others to make my decisions for me.” “It is annoying but not upsetting to be criticized.” “I find it hard to go against what others think.” Perfectionism Cognitions In- ventory (PCI)/ No/NA Flett, Hew- itt, Blank- stein & Gray, 1998 25 items/ 1 factor 5-point Likert Journal of Personality and Social Psychology A measure of auto- matic thoughts that reflect personality factors associated with vulnerability to psychological disor- ders; specifically anxiety, depression. “Why can’t I be perfect?” “Things are seldom ideal.” “I am too much of a perfectionist.” Rational Behav- ior Inventory (RBI)/ No/NA Shorkey & Whiteman, 1977 38 items/ 11 factors 5-point Likert Educational and Psycho- logical Meas- urement Clinical instrument for assessment, treatment planning, & evaluation of cli- ents, by therapists who used RET. “I find that my occupation and social life tend to make me unhappy.” “I usually try to avoid chores which I dislike doing.” “I worry about little things.”  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 866 Situational Self-Statement and Affective State Inventory (SSSASI)/ No/NA Harrell, Cham- bless, & Calhoun, 1981 5 items/ 10 factors 5-point Likert Cognitive Therapy and Research Useful in assessing dimensions important to REBT; that certain classes of maladap- tive cognitions are linked to emotional distress (anxiety, depression). There is also a SSSASI- thoughts measure. In response to situations; “I’ve really done a lousy job. I’ve let everybody down. My work just hasn’t been any good. I don’t think I can do any better.” “I wish I had done better. I still think my work is good and with a little more persistence, I will do better in the next contest.” “I guess it really is difficult for peo- ple to straighten things out some- times. I hope when we see each other again we’ll be able to talk without so much conflict.” Smith Irrational Beliefs Inventory (SIBI)/ No/NA Smith, 2002 24 items/ 6 factors 4-point Likert Stress man- agement: A comprehen- sive handbook of techniques and strategies Research instrument; Attempts to address the issue of the factor structure of irrational belief items “to iden- tify a core set of replicable and mean- ingful irrational be- lief factors”. “I always need help on important problems.” “Things didn’t turn out like I wanted; this is a disaster.” “I’m just a failure.” Survey of Per- sonal Beliefs (SPB)/ No/NA Demaria, Kassinove, & Dill, 1989 50 items/ 5 factors 6-point Likert Journal of Personality Assessment Identifying irrational beliefs in clinical & university popula- tions. Expression of anger, hopelessness, anxiety, depression, all due to the RET theoretical emphasis on irrational think- ing. “There are some things in life that I just can’t stand.” “There are times when awful things happen.” “I clearly should not make some of the mistakes I make.” Irrational Belief Scales Based on the Beck Model Automatic Thoughts Ques- tionnaire-30 (ATQ-30)/ Companion piece ATQ-N/ NA Hollon & Kendall, 1980 30 items/ 4 factors 5-point Likert Cognitive Therapy and Research Designed to measure automatic thoughts associated with de- pression. “I can’t finish anything.” “I’m a loser.” “My life is a mess.” Cognition Checklist (CCL)/ No/NA Beck, Brown, Steer, Ei- delson, & Riskind, 1987 26 items/ 2 factors 5-point Likert Journal of Abnormal Psychology Designed to measure the content-specificity hypothesis of the cognitive model by measuring the fre- quency of automatic thoughts relevant to anxiety and depres- sion. “I will never overcome my prob- lems.” “I’m a social failure.” “People will laugh at me.” Cognitive Triad Inventory (CTI)/ No/NA Beckham, Leber, Watkins, Boyer, & Cook, 1986 36 items/ 6 factors 7-point Likert Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Role of the cognitive triad in the develop- ment and mainte- nance of depression. “I can’t do anything right.” “There is no reason for me to be hopeful about my future.” “My family doesn’t care what hap- pens to me.”  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 867 867 Crandell Cogni- tions Inventory (CCI)/ No/NA Crandell & Cham- bless, 1986 45 items/ 4 factors 5-point Likert Behaviour Research and Therapy A measure of fre- quency of depressive thoughts; designed to measure self-referent statements associated with depression. “Everything I do is a failure.” “I’ll never do as well as others.” “Nothing seems exciting anymore.” Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS)/ Two parallel 40-item forms DAS-A, DAS-B/ NA Weissman & Beck, 1978 100 items/ 9 factors 7-point Likert Unpublished; contact scale authors for copy Designed to measure Depressionogenic schemas constituting predispositions to depression. “Being alone leads to unhappiness.” “If I ask a question, it makes me look stupid.” “I am nothing if a person I love doesn’t love me.” General Cognitive Error Questionnaire (CEQ)/ No/NA LeFebvre, 1981 24 vi- gnettes/ NA 5-point Likert Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Measures cognitive errors linked to de- pression; Also looked at levels of depres- sion in bulimia. “Last time you went skiing, you took a hard fall and got shook up. You’re supposed to go skiing this weekend but think, ‘I’ll probably fall and break my leg and there will be no one to help me.’” “You have been working for six months as a car salesperson. You had never been a salesperson before and were just fired because you were not meeting your quotas. You thought, ‘Why try to get another job, I’ll just get fired. ’” “Last night your spouse said s/he thought you should have a serious discussion about sex. You think to yourself, ‘S/he hates the way we make love.’” Personality Be- lief Question- naire (PBQ)/ PBQ-Short Form/NA Beck & Beck, 1991 126 items/ 9 sub- scales 5-point Likert Unpublished; contact scale authors for a copy Examines role of irrational beliefs in personality disorders: Avoidant, obses- sive-compulsive, dependent, narcissis- tic, paranoid, and borderline. “I am socially inept and socially undesirable in work or social situa- tions.” “Unpleasant feelings will escalate and get out of control.” “I am helpless when I’m left on my own.” Irrational Belief Scales Not Linked to Either the Ellis or Beck Model Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (FNE)/No/NA Watson & Friend, 1969 30 items/2 factors True/ False Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Assess degree of apprehension at the prospect of being evaluated negatively. “I often worry that I will say or do wrong things.” “I am frequently afraid of other peo- ple noticing my shortcomings.” “I worry about what kind of impres- sion I make on people.” Penn State Worry Scale/ No/NA Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990 16 items/1 factor 5-point Likert Behavior Research and Therapy Identify the role of worry in anxiety disorders “I worry all the time.” “My worries overwhelm me.” “Once I start worrying, I can’t stop.” Next, we were interested in evaluating the measure’s reported validity or how well the measure assesses what it claims to measure. More specifically, three dimensions of a measure’s validity were explored: 1) concurrent validity or how well the measure correlates with another related measure; 2) discriminant validity or how well the  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 868 measure fails to correlate with other measures, and 3) construct validity or how well the measure has been op- erationalized. Table 2 presents a summary of our psy- chometric evaluation for each measure of irrational be- liefs. The measures are ordered in such a way that those that possess the strongest psychometric properties are presented first, followed by those that possess weaker psychometric properties. Given the large number of irra- tional beliefs measures appearing in the literature, we recommend that investigators utilize only those with the most psychometric support. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Measures Based on the Ellis Model Irrational Beliefs Test (IBT). Jones [14] developed the 100-item IBT which requires respondents to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with each of the items on a 5-point scale. Half of the items indicate the presence of a particular irrational belief, the other half its absence. Lohr and Parkinson[15] reported that the IBT demonstrated positive correlations with measures of anxiety and depression. Whereas the IBT initially was one of the most popular measures of irrational beliefs, its use has gradually diminished due to criticisms that these beliefs were not measured independently of the emo- tional consequences they were hypothesized to cause [16]. Nonetheless, it still sees occasional use (see Munoz- Eguileta [17]). Woods [18] argued that a modified IBT could be useful; he identified 47 IBT items that meas- ured beliefs and found that these items were related to emotional distress, psychosomatic symptoms, and suici- dal contemplation. Rational Behavior Inventory (RBI). Developed by Shorkey and Whiteman [19], the RBI is a 38-item in- strument designed for use in the assessment and treat- ment planning of REBT clients. The answers range from strongly agree to strongly disagree on a 5-point Likert scale which results in 11 rationality factors plus a total rationality score. The RBI has been shown to correlate highly with self-report measures of depression and anxi- ety [20]. Along with the IBT, the RBI has been the most frequently used measure of irrational cognitions [21] but suffers from the same psychometric inadequacies as the IBI: low reliabilities of its subscales and the confusion of irrational cognitions with negative affect [22]. Indeed, Keinhorst, van den Bout, and de Wilde [23] found that only those items on the RBI that are emotion-bearing correlate with emotional distress. Additional research on the factor structure of the RBI suggested discarding some of the items that loaded poorly in order to improve the purity of RBI factors [24]. Idea Inventory. The Idea Inventory [25] is a 33-item, 3-point Likert scale comprised of the 11 original Ellis irrational beliefs. The items are presented as an irrational idea, and any disagreement represents rational thinking. The measure results in a total irrationality score plus scores on each individual belief. While Smith [26] noted that this scale has shortcomings in that it does not meas- ure ideas independently of emotional consequences, Jacobsen, Tamkin, and Hyer [27] found that the inven- tory had excellent internal consistency and strong dis- criminant validity. However, Kassinove (personal com- munication June 26, 2009) suggested that the Idea In- ventory no longer be used as it is based on the original Ellis formulation and was “very old.” Common Beliefs Survey-III (CBS-III). The CBS-III [28] is a 54-item measure with six, 9-item subscales; each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Agree- ment indicates irrationality for 29 items and rationality for 25 items. The CBS-III has demonstrated very good psychometric properties [29] including satisfactory in- ternal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity. For example, irrational beliefs as measured by the CBS-III were found to be related to substantial variance in two negative indices of well- being, depression and anxiety [30]. Additionally, there is the CBS-III SF (short form) with 19 items, which has also demonstrated good psychometric properties [31]. The CBS-III continues to be used extensively. The Situational Self-Statement and Affective State In- ventory (SS SASI). The SSSASI [32] presents respon- dents with five hypothetical irritating events and disap- pointing outcomes; each vignette is followed by five possible thoughts and five possible emotions the indi- vidual might experience following the vignette. Having read a vignette, the subject responds to five feeling statements (angry, anxious, suspicious, depressed, and hopeful) and five self-statements, indicating the level of agreement with each one. Higher scores indicate greater irrationality. The SSSASI is a measure of thoughts and feelings that permits the determination of the relation between cognitions and affective state, a central REBT tenet (i.e., that maladaptive cognitions are linked to emotional distress). Such correlations were found in clinical and non-clinical populations [33]; clinical re- spondents endorsed negative irrational thoughts signifi- cantly more than non-clinical participants [34]. The SSSASI has been found to have satisfactory internal consistency and test-retest reliability, although lower than that of the CBS-III, perhaps due to its assessment of reactions to highly specific situations [34]. The Belief Scale (BS). The BS [35] is a 20-item meas- ure of Ellis’ original list of irrational beliefs. It was de- signed to correct the content validity problems of previ- ous measures such as the IBT and RBI. Each item is ated on a 5-point scale, and item ratings are summed to r  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 869 869 Table 2. Comparison of Psychometric Properties. Name of Scale/Other Forms/Also Known As Author(s) Reliabilitya Concurrent Validityb Discriminant Validityc Construct Validityd Irrational Belief Scales Based on the Ellis Model Child and Adolescent Scale of Irrationality (CASI)/Short form (CASI-Revised)/NA Bernard & Laws, 1987**** ++ †† General Attitude and Belief Scale (GABS)/No/Attitudes Belief Scale 2, ABS 2,A&B II, ABS II DiGiuseppe, Leaf, Exner, & Robin, 1988**** ++ †† Perfectionism Cognitions Inven- tory (PCI)/No/NA Flett, Hewitt, Blank- stein, & Gray, 1998 **** ++ †† Situational Self-Statement and Affective State Inventory (SSSASI)/No/NA Harrell, Chambless, & Calhoun, 1981 **** Belief Scale (BS)/No/M.S. Belief Scale, MSBS, Irrational Belief Scale, IBS Malouff & Schutte, 1986 *** ++ †† Common Beliefs Survey-III (CBS-III)/ Short form Exists (CBS-II SF)/NA Bessai, 1977 *** ++ †† Irrational Beliefs Inventory (IBI)/ No/NA Koopmans, Sander- man, Timmerman & Emmelkamp, 1994 *** ++ †† Survey of Personal Beliefs (SPB)/No/NA Demaria, Kassinove, & Dill, 1989 *** ++ † Idea Inventory /No/NA Kassinove, Crisci, & Tiegerman, 1977 Split-half, first third-second third = 0.84, first third-final third = 0.90, second third-final third = 0.91 + † Evaluative Beliefs Scale (EBS)/No/NA Chadwick, Trower, & Dagnan, 1999 *** + † Irrational Beliefs Test (IBT)/IBT Revised (Woods, 1992)/NA Jones, 1968 ** ++ †† Irrational Beliefs Survey (IBS)/No/Irrational Beliefs Scale Watson, Vassar, Ple- mel, Herder, Manifold, & Anderson, 1990 ** + † Camatta & Nagoshi Scale/No/NA Camatta & Nagoshi, 1995 ** + † Ellis Emotional Efficiency In- ventory (EEEI)/No/NA Ellis, 1992 ** + † Rational Behavior Inventory (RBI)/No/NA Shorkey & Whiteman, 1977 Split half = 0.73 + †  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 870 Smith Irrational Beliefs Inven- tory (SIBI)/No/NA Smith, 2002 * Irrational Belief Scales Based on the Beck Model Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-30 (ATQ-30)/Companion piece ATQ-N/NA Hollon & Kendall, 1980 **** ++ †† Personality Belief Questionnaire (PBQ)/ PBQ-Short Form/NA Beck & Beck, 1991 **** ++ †† Cognitive Triad Inventory (CTI)/No/NA Beckham, Leber, Wat- kins, Boyer, & Cook, 1986 **** + † Crandell Cognitions Inventory (CCI)/ No/NA Crandell & Chambless, 1986 **** + † Cognition Checklist (CCL)/ No/NA Beck, Brown, Steer, Eidelson, & Riskind, 1987 **** Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS)/ Two parallel 40-item forms DAS-A, DAS- B/NA Weissman & Beck, 1978 *** ++ †† General Cognitive Error Ques- tionnaire (CEQ)/No/NA LeFebvre, 1981 *** + † Irrational Belief Scales Not Linked to Either the Ellis or Beck Model Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (FNE)/No/NA Watson & Friend, 1969**** ++ †† Penn State Worry Scale/ No/NA Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990 **** ++ †† Note: Within a group, measures are ordered based on the strength of their psychometric properties; aCronbach’s alpha for total scale; subscales may have lower Cronbach’s alpha (**** ≥ 0.9; *** ≥ 0.8, ** ≥ 0.7; * ≤ 0.7); bSignificant correlations with three types of measures that should be related were examined: self-reported psychopathology, clinical ratings, and behavior or performance ratings. ++ at least two of the three types of concurrent validity reported in the literature; + at least one type of concurrent validity reported in the literature; cSignificant differences between the measure and other, theoretically distinct measures. at least two studies reported adequate discriminant validity; at least one study reported adequate dis- criminant validity; dSignificant differences between participants high and low on the symptomatology or those who have differences in symptomatol- ogy, or diagnosed and undiagnosed participants. †† at least two studies reported adequate construct validity; † at least one study reported adequate construct validity. produce a total score. The Belief Scale is referred to by several titles in the literature, including the MSB and M.S. Belief Scale [36], the MSBS [37], and the Irra- tional Beliefs Scale or IBS [38]. The BS has shown good internal consistency and stability, and the scale has cor- related highly with other measures of irrational beliefs. BS scores were positively correlated with levels of de- pression and anxiety in psychiatric patients [36]. The Child and Adolescent Scale of Irrationality (CASI). The CASI [39] was designed to assess adoles- cents’ overall level of irrational thinking; it consists of 44 statements set in a Likert-type format, which yields six sub-scores and a total irrationality score. There are three clusters of general irrational ideas and two irra- tional belief scales within each of the three clusters for examples see Burnett [40]. An abridged version with 25 items, the CASI-Revised, was developed by Burnett.[41] There is evidence, provided by Burnett [40], of sound  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 871 871 reliability and construct validity. Bernard and Cronan [12] found significant correlations between the CASI and trait anxiety. The General Attitude and Belief Scale (GABS). The GABS [42] was developed to take account of three con- tent domains which are recurrent themes in irrational beliefs (achievement, approval, and comfort), and four processes of irrational thinking (demandingness, awfu- lizing, self-downing, and low frustration tolerance). Ac- cording to Bernard [43] the GABS has good reliability and convergent/discriminant validity. Using this scale, investigators found a direct relationship between irra- tional beliefs and depression [44]. The literature is not always clear about the name and history of this measure, however. It has been referred to as the Attitudes and Be- liefs Scale 2 or ABS 2 [45], the A & B II [18], and the ABS II [46] with DiGiuseppe et al. [42] as its authors. The Attitude and Belief Scale has been attributed to Bur- gess [47] as well as DiGiuseppe & Leaf [48]. Research- ers have reported on a 72-item version [43] and a 55- item version [49] of the GABS. This measure does re- quire the permission of its authors for use (i.e., Fulop, personal communication, June 30, 2009). The Survey of Personal Beliefs (SPB). The SPB [50] is occasionally referred to as the Personal Beliefs Test or PBT [51] in the literature. They are in fact the same test (H. Kassinove, personal communication, June 29, 2009). The SPB contains 50 items which are scored on a 6- point Likert scale and is designed for people over 16 years of age. It includes items from the PBT which were reworded to conform more clearly to REBT theory. Ini- tial results with the SPB indicated satisfactory total and scale reliability [50]. Validity research indicated that total rationality was related to negative affect [52]. Irrational Beliefs Survey (IBS). The IBS [53] is an 11-item scale which, using simplified language, grew out of an earlier measure of irrational thinking [54]. The original test was based on an early formulation of Elli- sonian [55] theory. Respondents answer via a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Maltby and Day [56] found one factor in a non-clinical population resulting in one composite score; while addi- tion research [57] found a significant correlation be- tween IBS scores and a depressive attributional style. The IBS was not initially named by Watson et al. [53]; Day and Maltby [57] referred to it as the Irrational Be- liefs Survey, while Egan, Canale, del Rosario, and White [58] referred to it as the Irrational Beliefs Scale. The Ellis Emotional Efficiency Inventory (EEEI). The EEEI [59-60] assesses irrational and rational coping re- sponses to past irrational beliefs instead of latent irra- tional beliefs. The 60-item instrument is scored on a 5- point Likert scale. It measures overall levels of REBT disputing as well as three main factors: anti-awfulizing, anti-self-downing, and anti-low-frustration tolerance dis- putes. Poor coping on the EEEI is indicative of higher long-term levels of emotional dysfunction. The EEEI demonstrated a stable three-factor structure and strong convergent/divergent validity [61]. Irrational Beliefs Inventory (IBI). This 50-item scale, developed in the Netherlands by Koopmans, Sanderman, Timmerman, and Emmelkamp [22], is based on the item pool of the IBT and the RBI. The IBI is distinguishable from these scales in that it measures cognitions rather than negative affect, a criticism leveled at the IBT and RBI. The IBI is answered via a 5-point scale and con- sists of five subscales (worrying, rigidity, need for ap- proval, problem avoidance, and emotional irresponsibil- ity) plus a total score. Research has demonstrated con- sistent psychometric properties across several cultures, including the American version [62]; internal consis- tency was found to be of an acceptable magnitude, and the five subscales were found to be independent of each other. The IBI has been used to investigate the role of irrational beliefs in obsessive-compulsive disorder, so- cial phobias, and therapy for depression [62]. Camatta and Nagoshi Scale. The irrational beliefs scale of Camatta and Nagoshi [63], which is unnamed, was designed to be a brief test of a respondent’s prone- ness to Ellisonian irrational beliefs. According to its au- thors, each of the 10 items describe one irrational belief identified by Ellis [55]. The test was found to have good internal reliability and to be a good predictor of alcohol use problems [64]. The Perfectionism Cognitions Inventory (PCI). The PCI [65] is a 25-item measure of automatic thoughts and beliefs that perfection must be attained; the thoughts assessed via the PCI are consistent with the observations by Ellis [66] about irrational thinking and perfectionism. The PCI differs from other measures in that it assesses the frequency of these thoughts which had occurred during the previous week. Respondents rate statements about the need to be perfect on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). Scores may fluctuate based on recent experiences. The PCI was found to have an adequate degree of internal consistency and validity [67]. Dys- functional thinking as measured by the PCI has been shown to be associated with higher levels of depressive symptomatology and anxiety [67]. Evaluative Beliefs Scale (EBS). The EBS [3], devel- oped in response to criticisms of earlier irrational beliefs tests, is a distinctively cognitive measure of purely nega- tive evaluative beliefs. It is an 18-item, self-report in- strument constructed to measure negative person evalua- tions across three dimensions: where an individual be- lieves others are making evaluations of them, where the  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 872 individual makes an evaluation of him- or herself, and where the individual evaluates others. The EBS was de- signed to identify an individual’s global negative evalua- tive beliefs. Item responses are made on a five-point scale. The EBS was found to have good internal reliabil- ity, an adequate factor structure, and good predictive validity for anxiety and depressive symptoms [3]. Smith Irrational Beliefs Inventory (SIBI). The 24-item SIBI [68] is situation specific in that it asks respondents to rate on a 4-point Likert scale how much they dis- played irrational thinking during a recent recalled stressful situation. This format is used in order to be consistent with Ellis’ [55] original conceptualization of irrational beliefs as higher-order cognitions inaccessible through simple self-report scales. Amutio and Smith [69] found that the SIBI displayed a consistent seven-factor structure across situational formats and cultures. 3.2. Measures Based on the Beck Model The Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS). The DAS [70], a 100-item, self-report instrument answered on a 7-point Likert scale, was developed to assess dysfunctional be- liefs and thoughts posited by Beck and his colleagues as being associated with vulnerability to depression. It was later transformed into two parallel 40-item forms, the DAS-A and the DAS-B [71]. Reliability and validity data for the DAS support its use as a measure of depres- sionistic beliefs [72]; it has been argued that the DAS-A is one of the most efficient instruments for measuring the cognitive distortions associated with depression. [71] DAS scores for outpatients being treated for depressive disorders decreased following treatment [73]. The Dys- functional Attitudes Scale for Medically Ill Elders or DASMIE [74] incorporated items from the DAS along with new items to measure dysfunctional attitudes among the medically ill elderly. Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-30 (ATQ-30). In the ATQ-30 [75], respondents indicate for each of 30 specific, negative thoughts how frequently the thought has occurred to them during the past week. The ATQ-30 has high internal consistency and discriminates depressed from non-depressed samples [76]. There are companion pieces to the ATQ-30: the Automatic Thoughts Question- naire-Positive or ATQ-P and the ATQ-N (Negative) [77]. The ATQ correlates inversely with depressive symptoms; it distinguishes patients with depression from non- patients in both frequency of negative thoughts and de- gree of belief in these thoughts [78]. The General Cognitive Error Questionnaire (CEQ). The CEQ [4], designed to measure cognitive errors re- lated to general life experiences, provides 24 vignettes followed by a dysfunctional cognition about the vignette. Respondents rate, via a 5-point scale, how similar the thought is to what they would think. Vignettes are cate- gorized according to four types of cognitive errors iden- tified by Beck, including catastrophizing, overgeneraliz- ing, personalizing, and selective abstraction. High test-retest, alternate form, and internal consistency reli- abilities have been found, along with moderate correla- tions with other depressive cognitions inventories [79]. The Cognitive Triad Inventory (CTI). The 36-item CTI [80] utilizes a 7-point Likert-type scale to measure a central component of Beck’s cognitive theory of depres- sion, the cognitive triad. This includes negative views of the self, the world, and the future. The CTI was devel- oped to measure these negative views, which have been empirically linked to depression [1]. The CTI, which has items phrased in positive and negative directions, shows good to excellent internal consistency, and the total score correlates highly with measures of depression [81]. The Crandell Cognitions Inventory (CCI). The CCI [82] is a 45-item self-report measure of the frequency of depressive thoughts. Respondents rate on a 5-point scale how frequently they think each self-statement. Higher total scores indicate a higher frequency of depressive thinking. A strength of the CCI is that it was developed and normed with a clinical population. It has been dem- onstrated to discriminate among depressed, non-de- pressed psychiatric, and normal respondents, and has high internal reliability [82]. The Cognition Checklist (CCL). The CCL [83] was developed to measure the frequency of automatic thoughts relevant to anxiety and depression. The CCL has a 12-item subscale of anxious cognitions and a 14- item subscale of depressed cognitions rated on a 5-point scale. The measure contains irrational cognitions related to danger, thought to be a characteristic of anxiety, plus irrational cognitions related to depression to test explic- itly the content-specificity hypothesis of the Beck model. Patients diagnosed with anxiety disorders had higher mean CCL anxiety scores while patients diagnosed with depressive disorders had higher mean depression scores supporting the validity of the CCL [83]. The Personality Belief Questionnaire (PBQ). The PBQ [84] is a 126-item, self-report measure of beliefs related to personality disorders. The PBQ includes 14 items, each representing nine scales: Avoidant, Dependent, Ob- sessive-Compulsive, Histrionic, Passive-Aggressive, Nar- cissistic, Paranoid, Schizoid, and Antisocial personality disorders. Good test-retest reliability and internal con- sistency estimates were found for all of the PBQ scales, and patients with specific personality disorders endorsed dysfunctional beliefs consistent with their disorder [85]. The PBQ-Short Form (SF), a shorter and more refined version [86], was found to be more desirable for clinical and research purposes.  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 873 873 3.3. Measures not Linked to either the Ellis or Beck Model Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (FNE). The 30- item, true-false, FNE [87] was developed to determine the degree to which individuals experience apprehension due to the possibility of being unfavorably evaluated. Performance on the FNE has been shown to be corre- lated significantly with measures of anxiety and depres- sion [88]. A Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation or BFNE [89] changed the response format to a 5-point scale and reduced the measure to 12 items. Results from a revised version of the BFNE suggested that the different factor structures reported in the literature may reflect related but distinct constructs, and that more research is needed on its factor structure [90]. Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ). The PSWQ [91] is a 16-item inventory, based on a 5-point Likert scale, assesses the frequency of pathological worry. The PSWQ possesses high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability, and was found to significantly dis- criminate samples who met the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder. Cognitive therapy pro- duced reductions in PSWQ scores. Lim, Kim, Lee, and Kwon [92] observed that, as with the BFNE above, there is still some debate regarding the factor structure of the PSWQ. 3.4. Discussion and Recommendations Inasmuch as irrational beliefs play a central role in cog- nitive theory and therapy, they are a major focus in treatment and, consequently, are a primary intervention target. As noted by Beck et al. [85], these irrational be- liefs, if they are correctly identified, are a key conceptual theme linking an individual’s dysfunctional responses to the present situation. With the continued proliferation of irrational beliefs measures, we feel that it is essential that investigators continue to assess and reassess the psy- chometric properties of these tests and to determine if there is indeed a need for additional tests which appear to be measuring the same concept. This reassessment is all the more critical given the role of irrational thinking, as measured by traditional and newer context specific measures, in behaviors and cognitions which while pro- blematic, are not always considered to be pathological: gambling [93], obesity [94], postpartum depression [95], health practices [96], procrastination [97], exam-related distress [98], and even belief in the paranormal [99]. However, we did not include these measures in this re- view as we limited it to measures related only to depres- sion and anxiety. Several problems in the evaluation of extant tests of irrational beliefs became apparent during the course of conducting this review. The authors of the tests were frequently the sole source of reliability and validity evi- dence which varied considerably among published work. This makes it difficult to reach objective conclusions about the tests. Additionally, investigators incorporating these measures in their research are inconsistent in nam- ing and describing the development of the tests, which causes unnecessary confusion for investigators attempt- ing to replicate the original research. Unfortunately, it appears many of the early measures whose psychometric properties are in doubt are still used today; the Irrational Beliefs Test [14], the Rational Be- havior Inventory [19], and the Idea Inventory [25] still see occasional use in research and appear in the litera- ture. These tests contained many items that in fact did not measure beliefs; only 63% of the items in the IBT actually measured beliefs and only 57% of items in the RBI measured beliefs [100]. This raises an important point regarding the psychometric properties of measures of irrational beliefs: Such measures should assess beliefs -both irrational and rational-and not emotional or behavioral responses. Newer assessment measures have since evolved out of the theories of Ellis and Beck. Such measures include the Perfectionism Cognitions Inventory [65], the Smith Irrational Beliefs Inventory [68], the Ellis Emotional Efficiency Inventory [59], the Evaluative Beliefs Scale [3], and the Irrational Beliefs Inventory [22]. Although some of the newer tests are not used in research or cited in the literature as frequently, they should be used be- cause they possess better psychometric properties com- pared to the earlier, more frequently used, scales. Some of the most commonly used irrational beliefs tests still contain items that measure emotions and be- haviors rather than beliefs. These tests are used based on popularity and convenience even though newly devel- oped tests may have higher validity. Thus, our recom- mendation for clinicians and researchers interested in assessing irrational beliefs are to use the newer and more specialized measures of irrationality. These newer meas- ures should not be overshadowed by more commonly used tests which have less sound psychometric qualities. Finally, the theories of Ellis and Beck have been applied more recently to specific problems involving irrational thought; while these scales were not included in this review for reasons noted earlier, we find the Academic Rational Beliefs Scale [58], the Gambler’s Beliefs Ques- tionnaire [93], and the Irrational Food Beliefs Scale [94] to possess excellent psychometric properties and should be more widely used when assessing context specific problems involving irrational beliefs. There are promising new developments in the assess- ment of irrational beliefs, as well as challenges. Many popular assessment tools do not have the best psycho-  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 874 metric support yet continue to be used because of con- venience and commonality. Newer, more narrowly fo- cused measures are being developed which appear to possess better psychometric properties (e.g., the Perfec- tionism Cognitions Inventory). Whatever the future holds for measurement of irrational beliefs, the contin- ued improvement of these tests is essential to the study and treatment of depression, anxiety, and other disorders. REFERENCES [1] Haaga, D.A.F., Dyck, M.J. and Ernst, D. (1991) Empiri- cal status of cognitive theory of depression. Psychologi- cal Bulletin, 11 0(2), 215-236. [2] Beck, A.T., Rush, A.J., Shaw, B.F. and Emery, G. (1979) Cognitive therapy of depression. Guilford, New York. [3] Chadwick, P., Trower, P. and Dagnan, D. (1999) Meas- uring negative person evaluations: The evaluative beliefs scale. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23(5), 549-559. [4] Lefebvre, M.F. (1981) Cognitive distortion and cognitive errors in depressed and low back pain patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 49(4), 517-525. [5] Dryden, W. and Ellis, A. (2001) Rational emotive therapy. 2nd Edition, Guilford, New York, 295-348. [6] Woods, P.J. (1984) Further indications on the validity and usefulness of the Jones irrational beliefs test. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 2(2), 3-6. [7] Jones, J. and Trower, P. (2004) Irrational and evaluative beliefs in individuals with anger disorders. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 22(3), 153-169. [8] Watter, D.N. (1988) Rational-Emotive education: a re- view of the literature. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 6(3), 139-145. [9] Farley, F. (2009) Albert Ellis. American Psychologist, 64(3), 215-216. [10] Ellis. A. (1997) RET as a personality theory, therapy approach, and philosophy of life. In: Wolfe, J.L. and Brand, E., Eds., Twenty Years of Rational Therapy, Insti- tute for Rational Living, New York. [11] Ellis, A. (2000) Rational-emotive therapy. In: Corsini, R.J. and Wedding, D., Eds., Current Psychotherapies, 6th Edition, Peacock, Itasca, 168-204. [12] Bernard, M.E. and Cronan, F. (1999) The child and ado- lescent scale of irrationality: Validation data and mental health correlates. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 13(2), 121-132. [13] Beck, A.T. (1976) Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press, New York. [14] Jones, R.A. (1968) A factored measure of Ellis’ irrational belief system with personality and maladjustment corre- lates. Dissertation Abstracts International, 29 ( 11-B), 4379- 4380. [15] Lohr, J.M. and Parkinson, D.L. (1989) Irrational beliefs and bulimia symptoms. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 7(4), 253-262. [16] Demaria, T. and Kassinove, H. (1988) Predicting guilt from irrational beliefs, religious affiliation, and religios- ity. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 6(4), 259-272. [17] Munoz-Eguileta, A. (2007) Irrational beliefs as predictors of emotional adjustment after divorce. Journal of Ra- tional-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 25(1), 1-16. [18] Woods, P.J. (1992) A study of “belief” and “non-belief” items from the Jones Irrational Beliefs Test with implica- tions for the theory of RET. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 10(1), 41-52. [19] Shorkey, C. and Whiteman, V. (1977) Development of the rational behavior inventory. Educational and Psy- chological Measurement, 37(2), 527-533. [20] Zurawski, R.M. and Smith, T.W. (1987) Assessing irra- tional beliefs and emotional distress: Evidence and im- plications of limited discriminant validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34(2), 224-227. [21] McDermut, J.F., Haaga, D.A.F. and Bilek, L.A. (1997) Cognitive bias and irrational beliefs in major depression and dysphoria. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 21(4), 459-476. [22] Koopmans, P.C., Sanderman, R., Timmerman, I. and Emmelkamp, P.M.G. (1994) The Irrational Beliefs In- ventory (IBI): Development and psychometric evaluation. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 10(1), 15- 27. [23] Keinhorst, C.W.M., van den Bout, J. and de Wilde, E.J. (1993) Does the Rational Behavior Inventory (RBI) as- sess irrationality or emotional distress? Personality and Individual Differences, 14(2), 375-379. [24] Himle, D.P., Hnat, S., Thyer, B. and Papsdorf, J. (1985) Factor structure of the rational behavior inventory. Jour- nal of Clinical Psychology, 41(3), 368-371. [25] Kassinove, H., Crisci, R. and Tiegerman, S. (1977) De- velopmental trends in rational thinking: Implications for rational-emotive school mental health programs. Journal of Community Psychology, 5(3), 273-277. [26] Smith, T. (1982) Irrational beliefs in the cause and treat- ment of emotional distress: A critical review of the ra- tional-emotive model. Clinical Psychology Review, 2(4), 389-397. [27] Jacobsen, R., Tamkin, A. and Hyer, L. (1988) Factor analytic study of irrational beliefs. Psychological Reports, 63(3), 803-809 [28] Bessai, J.L. (1977) A factored measure of irrational be- liefs. 2nd National Conference on Rational-Emotive Therapy, Chicago. [29] Thorpe, G.L., Parker, J.D. and Barnes, G.S. (1992) The Common Beliefs Survey III and its subscales: Discrimi- nant validity in clinical and nonclinical subjects. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 10(2), 95-104. [30] Ciarrochi, J. (2004) Relationships between dysfunctional beliefs and positive and negative indices of well-being: A critical evaluation of the common beliefs survey III. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 22(3), 171-188. [31] Thorpe, G.L. and Frey, R.B. (1996) A short form of the common beliefs survey III. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 14(3), 193-198. [32] Harrell, T.H, Chambless, D.L. and Calhoun, J.F. (1981)  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 875 875 Correlational relationships between self-statements and affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 5(2), 159- 173. [33] Thorpe, G.L., Barnes, G.S., Hunter, J.E and Hines, D. (1983) Thoughts and feelings: Correlations in two clini- cal and two non-clinical samples. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 7(6), 565-574. [34] Thorpe, G.L., Walter, M.I., Kingery, L.R. and Nay, W.T. (2001) The common beliefs survey III and the situational self-statement and affective state inventory: Test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and further psychometric considerations. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cogni- tive-Behavior Therapy, 19(2), 89-103. [35] Malouff, J. and Schutte, N. (1986) Development and validation of a measure of irrational belief. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(6), 860-862. [36] Templeman, T.T. (1990) Relationship of M.S. Belief Scale scores to depression and anxiety in hospitalized psychiatric patients. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 8(4), 267-274. [37] Culhane, S.E. and Watson, P.J. (2003) Alexithymia, irra- tional beliefs, and the rational-emotive explanation of emotional disturbance. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 21(1), 57-71. [38] Davies, M.F. (2008) Irrational beliefs and unconditional self-acceptance. II. Experimental evidence for a causal link between two key features of REBT. Journal of Ra- tional-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 26(2), 89-101. [39] Bernard, M.E. and Laws, W. (1987) Child and adolescent scale of irrationality. University of Melbourne. [40] Burnett, P.C. (1994) Self-talk in upper elementary school children: Its relationship with irrational beliefs, self- esteem, and depression. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 12(3), 181-188. [41] Burnett, P.C. (1995) Irrational beliefs and self-esteem: Predictors of depressive symptoms in children. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 13(3), 193-201. [42] DiGiuseppe, R., Leaf, R., Exner, T. and Robin, M.W. (1988) The development of a measure of irrational/ rational thinking. World Congress on Behavior Therapy. Edinburgh, Scotland. [43] Bernard, M.E. (1998) Validation of the general attitude and belief scale. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cogni- tive-Behavior Therapy, 16(3), 183-196. [44] Szentagotal, A. and Freeman, A. (2007) An analysis of the relationship between irrational beliefs and automatic thoughts in predicting distress. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 7(1), 1-9. [45] Fulop, I.E. (2007). A confirmatory factor analysis of the attitudes and belief scale 2. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 7(2), 159-170. [46] Braunstein, J.W. (2004) An investigation of irrational beliefs and death anxiety as a function of HIV status. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 22(1), 21-37. [47] Burgess, P. (1986) Belief systems and emotional distur- bance: An evaluation of the rational-emotive model. University of Melbourne, Parkville. [48] DiGiuseppe, R. and Leaf, R.C. (1990) The endorsement of irrational beliefs in a general clinical population. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 8(4), 235-247. [49] Addis, J. and Bernard, M.E. (2002) Marital adjustment and irrational beliefs. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 20(1), 3-16. [50] Demaria, T., Kassinove, H. and Dill, C.A. (1989) Psy- chometric properties of the survey of personal beliefs: A rational-emotive measure of irrational thinking. Journal of Personality Assessment, 53(2), 329-341. [51] Kassinove, H. (1986) Self-reported affect and core irrational thinking: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Rational- Emotive and Cognitive Therapy, 4(2), 119-130. [52] Kassinove, H. and Eckhardt, C.I. (1994) Irrational beliefs and self-reported affect in Russia and America. Person- ality and Individual Differences, 16(1), 133-142. [53] Watson, C.G., Vassar, P., Plemel, D., Herder, J., Manifold, V. and Anderson, D. (1990) A factor analysis of Ellis’ irrational beliefs. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(4), 412-415. [54] McDonald, A.P. and Games, R.G. (1972) Ellis’ irrational values. Rational Living, 7(2), 25-28. [55] Ellis, A. (1962) Reason and emotion in psychotherapy. Citadel, Secaucus. [56] Maltby, J. and Day, L. (2001) The irrational beliefs sur- vey, one factor or four? A replication of Mahoney’s find- ings. Journal of Psychology, 135(4), 462-464. [57] Day, L. and Maltby, J. (2003) Belief in good luck and psychological well-being: The mediating role of opti- mism and irrational beliefs. Journal of Psychology, 137(1), 99-110. [58] Egan, P.J., Canale, J.R., del Rosario, P.M. and White, R. M. (2007) The academic irrational beliefs scale: Devel- opment, validation, and implications for college counsel- ors. Journal of College Counseling, 10(2), 175- 183. [59] Ellis, A. (1992) Questionnaire: The elegant solution to emotional and behavioral problems. Albert Ellis Institute, New York. [60] Blau, S. (2001) A three-factor model of emotional effi- ciency: Demandingness, ego-disturbance, and discom- fort-disturbance. Union Institute and University, Cincin- nati, OH. [61] Blau, S., Fuller, J.R. and Vaccaro, T.P. (2006) Rational- emotive disputing and the five-factor model: Personality dimensions of the Ellis Emotional Inventory. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive Therapy, 24(2), 87-99. [62] Bridges, K.R. and Sanderman, R. (2002) The irrational beliefs inventory: Cross-cultural comparisons between American and Dutch samples. Journal of Rational- Emotive and Cognitive Therapy, 20(1), 65-71. [63] Camatta, C.D. and Nagoshi, C.T. (1995) Stress, depres- sion, irrational beliefs, and alcohol use and problems in a college sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 19(1), 143-146. [64] Hutchinson, G.T., Patock-Peckham, J.A., Cheong, J. and Nagoshi, C.T. (1998) Irrational beliefs and behavioral misregulation in the role of alcohol abuse among college students. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive Therapy, 16(1), 61-74. [65] Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Blankstein, K.R. and Gray, L. (1998) Psychological distress and the frequency of per-  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 876 fectionistic thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(5), 1363-1381. [66] Ellis, A. (2002) The role of irrational beliefs in perfec- tionism. In: Flett, G.L. and Hewitt, P.L., Eds., Perfection- ism: Theory, research, and treatment. American Psycho- logical Association. Washington, D.C., 217-229. [67] Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Whelan, T. and Martin T.R. (2007) The Perfectionism Cognitions Inventory: Psychometric properties and associations with distress and deficits in cognitive self-management. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive Therapy, 25(4), 255-277. [68] Smith, J.C. (2002) Stress management: A comprehensive handbook of techniques and strategies. Springer, New Yor k. [69] Amutio, A. and Smith, J.C. (2007) The factor structure of situational and dispositional versions of the Smith Irra- tional Beliefs Inventory in a Spanish student population. International Journal of Stress Management, 14(3), 321- 328. [70] Weissman, A.N. and Beck, A.T. (1978) Development and validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A pre- liminary investigation. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Toronto. [71] Macavei, B. (2006) Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale, Form A; norms for the Romanian population. Journal of Cog- nitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 6(2), 157-171. [72] Oliver, J.M. and Baumgart, E.P. (1985) The Dysfunc- tional Attitude Scale: Psychometric properties and rela- tion to depression in an unselected adult population. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 9(2), 161-167. [73] Farabaugh, A., Mischoulon, D., Schwartz, F., Pender, M., Fava, M., and Alpert, J. (2007) Dysfunctional attitudes and personality disorder comorbidity during long-term treatment of MDD. Depression and Anxiety, 24(6), 433- 439. [74] Koenig, H.G., George, L.K., Robins, C.J., Stangl, D. and Tweed, D.L. (1994) The development of a Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale for Medically Ill Elders (DASMIE). Clinical Geronotology, 15(2), 3-22. [75] Hollon, S.D. and Kendall, P.C. (1980) Cognitive self- statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4(4), 383-295. [76] Burgess, E. and Haaga, D.A.F. (1994) The Positive Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ-P) and the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire-Revised (ATQ-RP): Equivalent measures of positive thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 18(1), 15-23. [77] Ingram, R.E. and Wisnicki, K.S. (1988) Assessment of positive automatic cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 898-902. [78] Sharifi, V., Mojtabai, R., Ghassemzadeh, H., Karam- ghadiri, N. and Ebrahimkhani, N. (2008) Use of the Per- sian language version of the Automatic Thoughts Ques- tionnaire (ATQ) in depressed Iranian women. Depression and Anxiety, 25(5), 35-38. [79] Wertheim, E.H. and Poulakis, Z. (1992) The relationships among the general attitude and belief scale, other dys- functional cognition measures, and depressive or bulimic tendencies. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive Therapy, 10(4), 219-233. [80] Beckham, E.E., Leber, W.R., Watkins, J.T., Boyer, J.L. and Cook J.B. (1986) Development of an instrument to measure Beck’s cognitive triad: The cognitive triad in- ventory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 566-567. [81] Possel, P. Cognitive Triad Inventory (CTI): Psychometric properties and factor structure of the German translation. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimenal Psy- chiatry, in press. [82] Crandell, C.J. and Chambless, D.L. (1986) The valida- tion of an inventory for measuring depressive thoughts: The crandell cognitions inventory. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(4), 403-411. [83] Beck, A.T., Brown, G., Steer, R.A., Eidelson, J.I. and Riskind, J.H. (1987) Differentiating anxiety and depres- sion: A test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothe- sis. Journal of Abnormal Psycholology, 96(3), 179-183. [84] Beck, A.T. and Beck, J.S. (1991) The personality belief questionnaire. The Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research, Bala Cynwyd, PA. [85] Beck, A.T., Butler, A.C., Brown, G.K., Dahlsgaard, K.K., Newman, C.F. and Beck, J.S. (2001) Dysfunctional be- liefs discriminate personality disorders. Behaviour Re- search and Therapy, 39(10), 1213-1225. [86] Butler, A.C., Beck, A.T. and Cohen, L.H. (2007) The personality belief questionnaire-short form: Development and preliminary findings. Cognitive Therapy Research, 31(3), 357-370. [87] Watson, D. and Friend, R. (1969) Measurement of so- cial-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clini- cal Psychology, 33(4), 448-457. [88] Turner, S.M., McCanna, M. and Beidel, D.C. (1987) Validity of the social avoidance and distress and fear of negative evaluation scales. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25(2), 113-115. [89] Leary, M.R. (1983) A brief version of the Fear of Nega- tive Evaluation Scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371-375. [90] Carleton, R.N., McCreary, D.R., Norton, P.J. and As- mundson, G.J.G. (2006) Brief fear of negative evaluation scale-revised. Depression and Anxiety, 23(3), 297-303. [91] Meyer, T.J., Miller, M.L., Metzger, R.L. and Borkovec, T. D. (1990) Development and validation of the Penn State worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487-495. [92] Lim, Y.J., Kim, Y.H., Lee, E.H. and Kwon, S.K. (2008) The Penn State worry questionnaire: Psychometric prop- erties of the Korean version. Depression and Anxiety, 25(10), 97-103. [93] Steenbergh, T.A., Meyers, A.W., May, R.K. and Whelan, J.P. (2002) Development and validation of the Gamblers’ beliefs questionnaire. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(2), 143-149. [94] Osberg, T.M., Poland, D., Aguayo, G. and MacDougall, S. (2008) The irrational food beliefs scale: Development and validation. Eating Behaviors, 9(1), 25-40. [95] Hall, P.L. and Papageorgiou, C. (2006) Negative thoughts after childbirth: Development and preliminary validation of a self-report scale. Depression and Anxiety, 22(3), 121-129. [96] Christensen, A.J., Moran, P.J. and Weibe, J.S. (1999)  K. R. Bridges et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 862-877 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 877 877 Assessment of irrational health beliefs: Relation to health practices and medical regimen adherence. Health Psy- chology, 18(3), 169-176. [97] Bridges, K.R. and Roig, M. (1997) Academic procrasti- nation and irrational thinking: A re-examination with context controlled. Personality and Individual Differ- ences, 22(6), 941-944. [98] Montgomery, G.H., David, D., DiLorenzo, T.A. and Schnur, J.B. (2007) Response expectancies and irrational beliefs predict exam-related distress. Journal of Rational- Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 25(1), 17-34. [99] Roig, M., Bridges, K.R., Renner, C.H. and Jackson, C.R. (1998) Belief in the paranormal and its association with irrational thinking controlled for context effects. Person- ality and Individual Differences, 24(2), 229-236. [100] Robb, H.B. and Warren, R. (1990) Irrational beliefs tests: New insights, new directions. Journal of Cognitive Psy- chotherapy: An International Quarterly, 4(3), 303-311. |