Open Journal of Political Science 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 45-58 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojps) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2012.23006 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 45 Common Origin, Common Power, or Common Life: The Changing Landscape of Nationalisms Agnes Katalin K oos Political Science Department, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada Email: agnes_koos@sfu.ca Received June 21st, 2012; r evised July 11th, 2012; accepted Au g u st 1 1 th, 2012 Socio-territorial psychic constructs, such as national identities, are perhaps the most important psychic phenomena for political science, with their strength so consequential for wars and inter-ethnic conflicts. The construction of the EU has faced scholars and practitioners with two identity-related problems: (i) whether the socio-territorial identities can be conceptualized as being multi-layered (nested, hyphenated, with non-conflictual relationships among the components), and (ii) whether the higher levels of these identity constructs can be confined to civic aspects (e.g. to a Habermasian constitutional patriotism), as opposed to traditional nationalisms relying on assumptions of common origin, and shared culture. The most entrenched classification of nationalisms relies on an obvious difference between the kinds of na- tionalisms endorsed by the Irish and Germans, on one hand, and the French and white immigrant coun- tries like the US, on the other hand. These versions are generally labeled “ethnocultural,” involving the consciousness of a shared ancestry and history, and “civic”, relying on the idea of belonging to the same state. My argument is that a schism within the “civic” approach to nationalism can theoretically be ex- pected and empirically supported on the basis of the ISSP 2003, Eurobarometer 57.2 and 73.3 surveys. These datasets confirm the existence of three principal components of nationalism, which can be labeled “ethnocultural”, “great-power-civic” and “welfare-civic”. While the great-power-civic approach is con- cerned with and takes pride in the country’s military strength, international influence, sovereignty, and national character, the welfare-civic approach takes a more civilian stance and it is concerned with com- mon rights, fair treatment of groups, social security, and welfare within the country. In addition, support has been found for the assumption that people tend to construct their supra-national identity layer accord- ing to the molds for their national identity. Keywords: Socio-Territorial Identities; Nationalism; European Identity Introduction Socio-territorial psychic constructs, such as national identi- ties, are perhaps the most important psychic phenomena for political science, with their strength so consequential for wars and inter-ethnic conflicts. Yet, political science joined in the scholarly preoccupation with socio-territorial identities only recently. Among the great political science paradigms, interna- tional relations realism has taken nati onali sms for u ncha llenge d givens, though of different intensity in different states. Interna- tional relations liberalism, after a short but significant concern with the self-determination of ethnic groups after the 1st World War, only renewed interest in ethnic and minority arrangements toward the end of the 20th century. In comparative politics, Modernists relegated nation formation to a pre-mass politics and pre-democracy era, thus concern with it has been dropped from the study of modern political systems. Nationalism in advanced settings became an important topic when the func- tionalist dreams about the formation of a European identity started to become true. In the previous decades, though, scho- lars and politicians were confronted with the opposing propos- als of Donald Horowitz and Arend Lijphart with regard to con- stitutional engineering in divided societies1. The major theoretical debates on socio-territorial identities have been unfolding in other social sciences, particularly soci- ology. By the 1990s the “foundational” debate of the field be- tween primordialist and constructivist positions was largely concluded. Political science tended to import constructivist viewpoints, but these had a difficult time in making their way into the core theoretical and methodological frames of the dis- cipline focused on a Westphalian state system. We may recall Kanchan Chandra’s (2001) amazement that the findings of the modernist-constructivist camp “are being conspicuously and comprehensively ignored in new research linking ethnic groups to political and economic outcomes” (p. 7). From a political science point of view, the time horizon adopted by alternative explanations is very important. For pri- mordialists (perennialists), socio-territorial identities are im- mutable, exogenous to all other social phenomena, and they are 1Horowitz, in the true spirit of Modernism, looked for possibilities to reduce the impact o f et hni c cleav ages on pol itical o u tco mes. Ass umin g t hat deepen - ing cleavages threaten political stability, he championed systems that i) reward moderation and penalize extremism; ii) encourage cross-ethnic cooperation, such as channel ethnic tensions in two large parties along the Left/Right dimension; and iii) divide state power along non-ethniclines. Horowitz thought that cross-cutting cleavages mitigated ethnic conflict, but many other theorists doubted that his formulas were conducive to inter- ethnic accommodation. Lijphart, for instance, proposed “consociational” mechanisms, t hat is , p ow er s har ing along eth ni c lin es. I n th is t heo r y, so lvin g conflicts, rather than artificially silencing them, is the key to long-term political stability and inter-ethnic peace. There is an ongoing debate about whether consociationalism reinforces ethnic divides or not. It does not seem to fuel furthe r animosity; but it may boost ethnic (group) consciousnesses.  A. K. KOOS master identities in relation to other collective identities. For constructivists2, identities are malleable, subjected to a number of social influences, including political institutions, and people may have non-hierarchically ranked multiple collective identi- ties, among them multiple socio-territorial identities. The lite- rature focused on socio-territorial identities regularly takes sides in this debate, and slowly a dimension with many inter- mediate values has come about, for instance, Anthony Smith’s ethno-symbolism being placed at the middle of the scale. The perennialist versus constructivist stance has a bearing on how nation is defined, and on estimates of time necessary for na- tion-formation. The basic schism in the conceptualization of nation, traditionally mapped out as ethnocultural nationalism versus civic nationalism, is inherently related to the paradig- matic divide. Ethnocultural nationalisms tend to see themselves as perennial entities, and assign a much longer time scale to nation-formation than civic nationalisms do. Accepting the idea that collective identities are subject to change, we have to assume that they do so constantly. In the case of national identities, it is their original creation that has received the most attention. But the maintenance of national identities does also suppose a coherent social discourse that places a premium on being a patriot. In the words of Ernest Renan, “nations are daily plebiscites”. With changing interna- tional and domestic institutions, 21st century nationalisms can- not be identical with 19th century nationalisms. They are also likely to have another status within the individual psyches than in the previous centuries. Accurately taken, it is not only the nationalisms, but the whole complex of socio-territorial identi- ties that are changing. The socio-territorial identity complex may be described as including, besides nationalism, the “lo- cal-patriotism” of attitudes toward locality and region, includ- ing minority group consciousnesses, either ethnocultural or of an other type, as well as attitudes toward the above-national fora such as the United Nations. In general, I would argue that in today’s world, and mainly in its more developed parts, i) the salience of socio-territorial identities, in general, declines; 3ii) the need for a unique master identity is less and less supported; and iii) the role of nationa- lism within the socio-territorial identity complex retrogrades. The emotional attachment to locality and region has always been measured as being very close to patriotism values. Also, with globalization and with regional integrations, people do not believe anymore that all decisions pertinent to their lives should or could be taken on the nation-state level. This relates to the cognitive component of socio-territorial identities. The impor- tance of a group for an individual hinges on the tasks that the respective group is supposed to address. State abilities have been eclipsed by globalization, no wonder people reformulate their expectations toward it. More narrowly, this paper aims at studying the types or ver- sions of national identity, by gauging their historical dynamics, as well. The empirical data for analyses comes from the Inter- national Social Survey Program’s (ISSP) 2003 round on Na- tional Identities and two Eurobarometer surveys, namely EB 57.2 (of 2002), and EB 73.3 (of 2010). The EU construction is a great opportunity for studying changes of socio-territorial identities, their causes and consequences. First, there are large scale changes of institutions, the state attributions being dele- gated onto lower and higher levels, that is, to sub-national and supra-national fora. And second, there is a conscious concern with stimulating the formation of a European identity, widely regarded as a requisite of democratization within the super- polity. Hypotheses National identities may be constructed in many ways, and their meanings (both denotation and connotation) vary across individuals. Yet, they may be deemed to display typical pat- terns across countries or across some groups, such as minorities, classes, and professional groups. The overwhelming majority of the literature authorizes a distinction between “ethnocultural” and “civic” versions of nationalism. While the first focuses on common ancestry and common (language and literature related-) culture, the second focuses on being citizens of the same state. Often, the ethnocultural version is taken for being more primi- tive and more dangerous, than civic nationalism. Yet, civic nationalisms (most typically in white immigrant countries) can be blamed for other things, such as, i) failure to generate levels of social solidarity comparable with those in ethnically ho- mogenous countries, in order to achieve welfare states; and ii) expected and implemented assimilationism, which might have been called a “melting pot” effect, but has always been carried out under the domination of a certain culture, such as white Anglo-Saxon Protestant in the US. Finally, there is no evidence that any of the nationalism versions would be more peaceful; high levels of militarism can occur in both4. In his 2000 book, David Brown forwarded a comprehensive scheme to classify nationalisms, which includes a third version, “multicultural”, as well (Figure 1). The scheme seems to be drawn from the point of view of majority policy makers taking into account the ethnic composition of their societies. In terms of constitutional engineering, civic nationalism endorses a Horowitzian, while multicultural nationalism, a Lijphartian pro- gram. Multicultural nationalism has been an answer to the social fact of ethnic fragmentation, leading to institutional transforma- tions such as “pillarization” in the Benelux states. But the causal arrows run both ways: the political institutions affect nationalisms, as well. Socio-territorial identities have to incor- 2We may conceive of the constructivist school in the field of collective identities as of a middle-range sociological theory. It is supported by such distinct comprehensive paradigms as functionalism/Modernism, Marxism, feminism, postmodernism, and institutionalism. Weberianism seems to be ambiguous w ith rega r d t o it . 3My emphasis is not on the strength of nationalist feelings (though I assume that these decrease, as well), but on the relationship of nationalism with other collective identities, such as social class or professional group. I be- lieve that this relative importance of national belonging is decreasing with time. This belief can survive counterexamples such as the outburst of na- tionalisms in former Yugoslavia and parts of former Soviet Union in the 1990s. On the one hand, I tend to endorse Tilly’s explanation that crumbling olitical authority triggers communal rivalry. And on the other hand, it is to be noted that all successor nation-states chose to join “federations” later: they became ei t h er p ar t s of t h e CI S, or members of t h e EU, o r can d id at es f o r EU membership. 4Still in the constructivist tradition, we should admit that the endorsement o kinds of nationalisms in different states is not accidental, but can be ren- dered meaningful by national histories. I would suggest that it is related to the presence of minorities within, or absence of co-nationals from a given state. Ethno-cultural nationalism has been endorsed by peoples with large proportion of co-nationals living abroad (Former West-Germany, Ireland, Hungary, Greece), while the civic- atriotic version has been promoted by countries without significant percentage of co-ethnics living abroad as mi- norities, but significant regional and ethnic variation inside the country (France, It aly, and t h e immigrant countries). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 46  A. K. KOOS Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 47 a: Figure 1. Brown’s (2000) class i f ic a tion scheme of nationalisms. porate notions of territorial institutions, most notably a notion of state. Since states have changed a great deal in the contem- porary world, socio-territorial identities are bound to rely on different meanings of state-ness. Of the above mentioned ver- sions of nationalism, it is the civic-type that may be expected to be the most susceptible to changes of state-ness. Basically, civic nationalism can be assumed to co-vary with transforma- tions of the state. being constructed. Democratic Welfare Nationalism It has been a distinctive feature of international relations libe- ralism, particularly of the democratic peace proposal, to point out the impact of domestic regimes on the behavior of states in the international arena. International relations constructivists assisted liberals with the claim that institutions influence the ways in which states (or their representatives in foreign policy decision-making) perceive their “national interest”, and define their relations with other states. Yet, none of the theories showed particular interest in the content and strength of nationa- lisms, and none has traditionally elaborated on the idea that in an era of mass democracy, people’s national identities may become causally consequential for developments in interna- tional relations5. The functionalist proposal for European inte- gration in the original Mitrany tradition, and as articulated by Deutsch, came very close to this thesis, but later neo-functiona- list turns dropped the interest in mass opinion on behalf of the interest in elite behavior. It was only in the 1990s that political science renewed its explorations in socio-territorial identities, ostensibly related to developments within the EU, as the most advanced regional integration. In the post-Maastricht world, little opposition remained to the idea that the future of integra- tion hinges on popular support for the project, both for enlargement and deepening of the cooperation among the “ever closer” states. Further, this popular support has increasingly come to be conceptualized in terms of European identity versus national identity. Alternative explanations, such as utilitarian ones, cannot circumvent the issue of whether people cling more to payoffs to the nation, the individual, or maybe to some par- ticular group, in their cost-benefit calculi? Opinion survey data show that people tend to place as much premium on payoffs to their nation as on benefits to themselves as individuals (Koos, 2007), while minorities such as Catalans in Spain and Scots in But we know little about what changes in state structures and in state roles affect socio-territorial identities, and how they affect them. The EU construction shed light on some related concerns, but has not led to a systematic inquiry in this sense. The major problems raised by integration are: 1) whether socio-territorial identities can be conceptualized as being multi- layered (nested, hyphenated, with non-conflictual relationships among the components); and 2) whether the higher levels of these identity constructs can be confined to civic aspects (such as to a Habermasian constitutional patriotism), as opposed to ethnocultural nationalisms relying on assumptions of common origin and shared culture, but also civic nationalisms premised on a unitary state language and some shared political under- standings. From the other side, changes of state-ness in the world have mainly been analyzed in two types of literature: effects of globa- lization, on the one hand, and regional integration, on the other. In Caporaso’s account of Westphalian, regulatory and post- modern states (1996), the two seem to come together. An im- portant insight of this study was that in both regulatory and postmodern states, labor’s bargaining power decreases. Other evidence also suggests that labor is at its best political efficacy and most likely to a chieve full-fledged welfare arrangements in smaller, homogenous nation-states, that is, in the traditional Westphalian states. This paper argues for two related claims: 1) once a welfare state is achieved, it has an impact on how people construct their nationalism; and 2) predominant senses of nationalism (and/or of sub-national socio-territorial identities) in a state have an impact on how supranational socio-territorial identities are 5Obviously within institutional settings that turn the principle into reality, such as increasing reliance on r eferenda in f oreign policy decision making.  A. K. KOOS Britain may be, in addition, grateful to the EU for fostering decentralization policies in the Member States. Renewed interest in socio-territorial identities does not mean, however, either the comeback of a single dominant paradigm in this field, or the existence of a generally accepted corpus of accumulating knowledge. The fundamental cleavage between primordialism and constructivism persists6, and inquiries into the content, forms, and causes of nationalism follow several paradigms. I would claim that there is a mainstream scholarship endorsing the idea that nationalism comes in several versions, and an important distinction can be made between its ethno-cultural and civic forms, a creed promoted by Brubaker (1992, 1996) and Greenfeld & Eastwood (2007), for instance. Yet, we have to allow for the existence of some opposition to this thesis. There have been arguments forwarded, for instance, to de-emphasize the importance of this cleavage on grounds that the two versions are each other’s strategic alternative in determined conditions (Niklas, 1999). Greenfeld (1992) found a cross-cutting cleavage, called individualism versus collectivism. And this paper intends to argue for the existence of an increas- ing difference between two types of civic nationalism. I subscribe to the constructivist tradition, and in this tradition we cannot exclude the political institutions from the determi- nants of socio-territorial identities. The content of national identity is rightly expected to be functional for the interests and political goals of the collectivity for which it has been elabo- rated, while the salience of national identity, to vary in function of the social-political tensions faced by that collectivity. Cross- country differences of ethnic fragmentation, regime, and insti- tutions have led to obvious differences of the ways in which people construct their national identities. The last great trans- formation of the nation-state—previous to the triumph of glob- alization and the postmodern governance of regional integra- tions—has been the implementation of the democratic welfare state in many developed countries. The consequences of this institutional change can be expected to be in the direction of “butter rather than guns”. There are many arguments supporting this expectation. i) Democracies do not fight each other, they have been shown to be inherently more peaceful and/or more circumspect with regard to war; and ii) The number and depth of treaties tying together the developed countries creates an international safety belt around them, which is regarded with much less skepticism by the large masses than by international relations realists. Actually, since the 1960s, Western Europe has consistently refused to increase its military spending, and after the end of the Cold War, both NATO and the OECD group reduced it7. Corresponding to these changes, and in an intricate two-way relationship with the institutional evolution, nationalisms in democratic welfare states can be expected to be (H1) less fueled by military imagery and by notions of necessary confrontation with other countries, and (H2) incorporate more sense of socio-economic solidarity. It is to be noted that militarism is a very potent cement to tie people together, as Raymond Aron’s maxim that “wars are the midwives of nations” put it. In wel- fare states, the militarist appeal is replaced with the possibility of a participatory political culture, and belongingness to a “from cradle to grave” welfare system. Other phenomena of importance, such as the ascension of a by default international environmentalism, and concern for the Third World, or at least for their own former colonies, may nuance the picture of new nationalisms. Layers of Socio-Territorial Identities Socio-territorial identities can be described as being verti- cally multi-layered. Most of the literature allows for types of complex and non-conflictual relationship between loyalty to locality, region, and country. This has also been measured re- peatedly, and sub-national loyalties in general have been found to co-vary with national attachment. There was no serious theoretical challenge formulated against these claims until the emergence of the problem of supra- (or post, or inter, or trans-) national indentities. The extension of the non-conflictual multi- layered structure in order to incorporate continent-wide polities has met severe resistance. Euroskepticism denies the possibility of a potent European identity, and challenges the whole theory allowing for multiple identities, as claimed, for instance, by functionalists. The main argument of the skeptics, as formu- lated, for instance, by Spiering (1999), is that people may have only one “layer” of identity, which is really salient and domi- nates all others. Actually, Spiering posits that people may have only one core identity, while they may identify themselves, very superficially, with many other groups. Spiering fails to distinguish between personal identity and master identity. Ob- viously, none denies the centrality of personal identities. Con- structivist supporters of multiple and multi-layered identity challenge the necessity of a master identity among collective identities. Marc Glendening (2005), a leader of the Euroskeptic Democracy Movement, argues for the necessity of a master identity on grounds that we have to unambiguously locate po- litical power at some level8. I do not think that psychology supports that locating power is a prerequisite for forming socio-territorial allegiances. Nevertheless, the modern world has made it difficult to locate: there are multiple power struc- tures in each society (such as economic, religious, and scientific, besides the governmental authority) and the pure governmental authority itself tends to be divided, horizontally in consocia- tional arrangements, and vertically in federalism, decentraliza- tion and subsidiarity. All opinion surveys show that people are able to have and do have multiple collective identities. Yet, there is a seed of truth in relating attachment and power. We may expect people to emotionally endorse only a polity over which they may have some influence9. But deeply felt lack of 8In Glending’s own words: “The other great political virtual reality claim the PMAs [Post-Modern Authoritarianism] make is that in the globalised world we can have “multiple identities”. We can simultaneously be citizens of our regions , countries, the EU and the Wor ld . I t ’s no t a cas e of “either /o r ”, t hat’s old-fashioned dualistic thinking, apparently. Political identity is dishonestly being spun here as if it was directly analogous to one’s capacity to appreci- ate the contrasting joys of both, say, thrash metal and trad jazz. As members of governed societies, we have to choose where we believe ultimate, end o the line, political authority should lie and which is the political community we give our allegiance to. Music lovers don’t face such necessary choices.” 9In order to be equ al with oth ers in that polit y, no t margin alized, and not alien ated This is an asp ect of the probl em of legitimac y, largel y debated wit hin and out side the EU. 6Yet, the cleavage is often labeled with other terms, such as primordialism versus instrumentalism, or perennialism versus Modernism. Though the constructivist/Modernist/instrumentalist camp seems larger, it is more di- vided, and there are well known primordialists opposing it, such as S. Van Evera. 7On a global scale, the big ex ception is the US, whi ch, despite some red uc- tion around 1990, kept increasing its military expenditures up to the latest years. For instance, in 1994 the US devoted 4.3 percent of its GNP to de- fense while the Non-US OECD average was only 1.8 percent and the on-US NATO average was 2.4 percent. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 48  A. K. KOOS Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 49 the ways in which people tend to construct their European iden- tity, and efficacy (or a feeling of alienation) can be shown to be associa- ted with preference for the lowest levels of decision (local and regional), not for the national level. (H4) The relationship between national identities and Euro- pean identity hinges on the type of nationalism endorsed. Even if we allow for the possibility of multiple collective identities, and within them, for multiple socio-territorial identi- ties, the concrete organization of component allegiances re- mains open for discussion. Belief in the existence of (non-tri- vial) multiple socio-territorial identity structures is regularly associated with the creed that the component allegiances are not in zero-sum terms. Evidence shows, for instance, that the sub-national and national “layers” tend to co-vary across coun- tries and age groups. In certain cases all three are weaker, in other cases all three are stronger; they do not threaten each other. Yet, beyond non-conflictuality, there is not much con- sensus with regard to the relations among the elements of a socio-territorial loyalty structure. Walzer (1990) prefers the term “hyphenated”, while others elaborate on “nested” socio- territorial identities, in which the levels subsume each other (Herb & Kaplan, 1999; Medrano & Gutierrez, 2001). Though my basic insight of socio-territorial identity structures is very close to a nested model, I prefer to call it “multilayered”. In some cases, the “layers” are not overlapping or including each other, but rather cross-cutting. For instance, Germans in Alsace may feel attached to their region, to France and to the EU, but their attachment to a German culture protrudes from this loyalty structure, fortunately not beyond the upper (EU) level. The next section intends to bring empirical support for these hypotheses. The two most comprehensive datasets to rely on are a Eurobarometer of 2002 (#57.2) and the International So- cial Survey Program’s 2003 round on National Identities. There is no newer cross-national data allowing for a comprehensive test of my claims. A Eurobarometer of 2010 (73.3), which has inquired about national identities, may support previous find- ings, but with a questionnaire much more reduced in compari- son to the two main sources of data. Data and Findings (A) Eurobarometer 57.2 (2002) was carried out in 21 coun- tries, but the battery on national identities was asked in 10 countries only: in West Germany, Greece, Italy, Spain, Great Britain, East Germany, Austria, Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. The questions of interest clustered under the numbers Q25 - Q27. Question 25 asked about “how close10 do you feel the following groups of people”, the alternatives including local, regional, national, and continent-wide groups (Illustration 1 ). Findings on the question battery Q25 reinforce previous re- sults obtained with similar questionnaires (Figure 2). One more theoretical concern with the nested identity struc- tures was raised by Risse (2005). What if the identity compo- nents influence each other, mesh and blend into each other? Risse calls this a “marble-cake” model of identity. I am sure that this is the case. Concretely, in the case of the EU, a form- ing European identity changes the meanings and emphases of national and sub-national identities, though not necessarily the strength of attachment to them. And the causal arrows run both ways. The existing national and other socio-territorial identities and perceived interests shape the ways in which people relate to the EU. Part of Risse’s insight about a marble-cake model of socio-territorial identity structure can be operationalized for the EU with two hypotheses: Attachment to locality, region and nationality co-vary closely. Attachment to EU citizens and Europeans is significantly farther Illustration 1. Questions on socio-t erritorial attachments in EB 57.2. 1) The in ha bit a nt s of the c ity or village where you live/have lived most of your life 2) The inhabitants of the region where you live (e.g. in UK: Scotland) 3) Fellow (NATIONALITY) 4) European Union citizens 5) Fellow Europeans (including European Union citizens and people living in countries that are part of the European continent but which may not make up part of the European Union) 6) People from Central and Eastern Europe 10 United States’citizens (H3) Traditions of nationalism-constructs in countries shape F eelin g clo se to ... 0.00 0.50 1.00 1.50 2.00 2.50 3.00 3.50 4.00 GREAT BRITAIN WEST GERMA NY CZECH REPUBLIC EAST GERMA NY AUSTRIAAverageITALYGREECESPAINPOLAND HUNGARY CITY/ VILLAGE REGION NAT IONALIT Y EU CITIZENS EUROPEA NS E.STN EUROPEANS US CITIZENS Feeling close to… Figure 2. Country means of variable battery Q25, “F ee li n g cl o se t o… ” . 10Very clo s e 1, Quite close 2, Not very close 3, Not at all close 4.  A. K. KOOS from the attachment to this triad. Yet, these latter also seem to show a co-varying pattern with the local and regional attach- ments, that is, in some countries the socio-territorial loyalties are stronger than in others in general. For instance, in Italy, Spain and Hungary, attachment to EU citizens comes close to what the British feel for their co-nationals. Questions 26 and 27 asked about the reasons for feeling close to certain groups, namely, to someone’s national group and to Euro- peans (Illustration 2). The lists of alternatives given to respondents paralleled each other to a considerable exten t, though not perfectly. The question battery Q26 was subjected to a principal com- ponent analysis. The results of a Varimax rotation of three fac- tors cumulatively explaining 74.44 percent of variance are dis- played in Table 1. Illustration 2. Questions on national and European identity in EB 57.2. Q.26. Different things or feelings are crucial to people in their sense of belonging to a nation. To what extent do you agree with the following statements? 11 “I feel (Nationality) because I share with my fellow (Nationa- lity)...” Q.27. Different things or feelings are crucial to people in their sense of belonging to Europe. To what extent do you agree with the following state- ments? Q.26 Q.27 1. I do not feel (Nationality) 1. I do not feel European 2. a common culture, customs & traditions 2. a common c ivilisation 3. a common language 3. membership in a European society with many languages and cultures 4. comm on ancestry 4. comm on ancestry 5. a common history and a common destiny 5. a common history and a common destiny 6. a common political and legal syste m 6. the EU institutions and an emerging common political and legal system 7. comm on r igh ts and dutie s 7. comm on r igh ts and dutie s 8. a comm on s ystem of social security/welfare 8. a common system of social protection within the EU 9. a nationa l economy 9. the right to free movement a nd residence in any part of th e EU 14a/14b. a common EU currency 10. a national army 10. an emerging EU defe n ce system 11. comm on borders 11. a common European homeland 12. a feelin g of nationa l pride 12. a feeling of pride for being European 13. national in dependence and sovereign t y 13. sovere ignty of the EU 14. our national character 15. our national symbols (the flag, the national anthem, etc.) 15. a set of EU symbols (flag, anthem, etc.) Although all variables have loadings on each factor, the three principal components are clearly and meaningfully outlined. On the basis of the loadings, it is easy to label them as “Ethnocul- tural” (with above-average loadings of the variables of common culture, language, ancestry and history); “Welfare civic” (with above-average loadings of the variables of political system, common rights, welfare system and economy), and “Great power civic” (with above-average loadings of the variables of army, borders, national pride, sovereignty, national character and national symbols). This last label possibly needs some ex- planation. Emphasis on the things belonging to this group re- flects a concern with a state at continuous conflict with other states, in the spirit of international relations realism. And this discipline is focused on giving advice to great powers, not to small and weak countries12. Interestingly, variables on national character do not load heavily on the “Ethnocultural” factor. Although primordialists claim that common culture, language, ancestry and history shape people similarly, theories of national character have been developed within a political competition-centered context, rather than within the descriptive context characteristic of the original Herderian ethno-cultural primordialism13. If the con- cept of national character has become politicized during the centuries, national symbols have constantly been adjusted to the political reality of borders and institutions in place. No wonder they load much heavier on the great-power-civic than on the ethno-cultural factor. Next, a similar principal component analysis, with a Varimax rotation, has been performed on the answers given to question #27, that is, to the question about experiencing a feeling of belonging to Europe. In this case, the first three factors explain 69.58 percent of variance. Though the principal components are less sharply outlined than for the national loyalty, the results suggest that the schisms and differences in constructing na- tional identities continue in the realm of European identity, as well. Otherwise, as shown in Table 2, European identity seems to obey the rules of construction of other socio-territorial iden- tities. The next interesting question is whether there is any relationship between the ways in which people construct their national iden- tities, on one hand, and their European identity, on the other. This may be studied with a correlation matrix of the two ques- tion batteries, in which we arrange the variables according to the three groups received with principal component analysis. In such a matrix, higher values along the main diagonal mean higher association between ethno-cultural national identity and ethno-cultural European identity, or welfare-civic national identity and welfare-civic European identity, as compared to the associations within variables belonging to different princi- pal components. It can be shown, that indeed, the average value of the correlation coefficients along the main diagonal is 0.26 as ompared to the average of 0.19 of the off-diagonal correlation c 12Small and weak countries can hardly benefit of the bullying tactics rou- tinely recommended by international relations realism. For economic as well as for security reasons, these countries are better off near cooperative alli- ance syst ems, includi ng regional integrations. 13Writing on the national character in 18th century France, historian P. Kra (2002) notices the transition of the concept from descriptive to politically activist: “At the beginning of the century national character was observed as a histor ical fact; towards t he end it was regar ded as an active pol itical force that must be fostered as the basis for reform. Thus national character moved from the realm of speculation to that of theory with immediate practical applications.” 11Strongly agree 1, Tend to agree 2, Tend to disagree 3, Strongly disagree 4. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 50  A. K. KOOS Table 1. Rotated Component Matrix of National Identity (N.ID). Principal componen t Component variable Great power civic 28.92% Welfare civi c 23.35% Ethnocultural 22.18% N.ID: comm on culture 0.261 0.220 0.774 N.ID: common language 0.212 0.237 0.786 N.ID: comm on ancestry 0.301 0.234 0.789 N.ID: common history 0.313 0.301 0.714 N.ID: political system 0.260 0.737 0.372 N.ID: common rights 0.232 0.784 0.326 N.ID: welfare system 0.256 0.839 0.212 N.ID: national economy 0.381 0.759 0.202 N.ID: national army 0.688 0.470 0.115 N.ID: common borders 0.660 0.384 0.233 N.ID: national pride 0.821 0.212 0.291 N.ID: national sove reignty 0.763 0.304 0.265 N.ID: national character 0.781 0.226 0.331 N.ID: national symbols 0.800 0.155 0.303 Table 2. Rotated Component Matrix of European Identity (EU.ID). Principal componen t Component variable Welfare civi c 24.13% Great power civic 23.48% Ethnocultural 21.97% EU.ID: common civilisation 0.317 0.186 0.738 EU.ID: common ancestry 0.149 0.301 0.823 EU.ID: common history 0.209 0.293 0.784 EU.ID: society membership 0.478 0.196 0.616 EU.ID: political system 0.654 0.330 0.383 EU.ID: common rights 0.736 0.270 0.340 EU.ID: welfare system 0.696 0.292 0.348 EU.ID: free movement 0.765 0.281 0.160 EU.ID: common currency 0.504 0.598 0.046 EU.ID: common defence 0.568 0.515 0.208 EU.ID: common home land 0.366 0.618 0.334 EU.ID: pride 0.242 0.753 0.372 EU.ID: EU sovereignty 0.368 0.716 0.280 EU.ID: symbols 0.204 0.780 0.278 coefficients, which supports the claim that people socialized to certain ways to construct their national identities tend to con- struct their European identity along the same criteria of sali- ence. (B) ISSP 2003 on National Identities included 33 countries, offering a larger base for generalizations than EB 57.2, but the questions asked are less suitable for reconstructing the under- lying dimensions of nationalist attitudes. Originally I intended to rely on the battery concerning reasons for national pride, but I had to realize that this battery lacks references to an ethno- cultural construction of national allegiance. Thus, I merged the battery on pride with a battery asking about the importance of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 51  A. K. KOOS certain features for being “a good national”14. The questions are presented in Illustration 3. The right column in Illustration 3 refers to the way in which the variables have been assessed when interpreting the principal components. While some of the answers are clearly pertinent to the dimensions sought for (that is, ethnocultural, welfare, and great-power civic) others may be associated with more of them. On one hand, they are not very relevant for my tripartite classi- fication, and on the other, they express commonsensical knowledge (included either in expectations, or in reasons of pride). For instance, “to be able to speak [country language]” may sound like an ethnocultural requirement, but it also ex- presses real, pragmatic concerns with communication. Respon- dents have not been given the opportunity to distinguish be- tween “speaking country language” and “being able to commu- nicate with country nationals”. On the pride battery, the items “Its scientific and technological achievements”, “Its achieve- ments in sports”, and “Its achievements in the arts and litera- ture” have become pragmatic in virtue of their wording, that is, because of their containing t h e word “achievem ents”15. In a first exploratory step I asked for comparing the country means on these eighteen variables, and for clustering the coun- tries on the basis of their means. All country means differences have been found significant, and the clustering returned four meaningful groups that reproduce the geographical zones in- volved in this opinion survey. The following four groups have emerged: 1) White immigrant/Anglo-Saxon, including the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Great Britain, Ireland, with three odd ones: Austria, Spain, and Japan. 2) Western European & Nordic, including France, Ger- many-East, Germany-West, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Nor- way, Switzerland, with two odd ones: Taiwan, and Israel Arabs. 3) Eastern European, including Slovenia, Czech Republic, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Poland, Russia, with two odd ones: Portugal, and South Korea. 4) Latin-American, including Chile, Uruguay, Venezuela, with two odd ones: Philippines, and Israel Jews16. Illustration 3. Questions about content of nationalit y & reasons for pride in ISSP 2003. Pertinent dimension(s) Q.3: Some people say that the following things are i mportant for b eing truly [ nationality]. Others say they are no t i mportant. How important do you think each of the following is...a To have [c ou ntry nationality] ancestry ethnocultural To have been born in [country] ethnocultural To be a [religio n ] [of the dominant religion] ethnocultural To have lived in [c. try] for most of one’s life ethnocultural/pragmatic To be able t o s peak [countr y language] pragmatic/ethnocultural To have [c o u n try nationality] citizenship civic/pragmatic To respect... political institutions and laws civic/pragmatic To feel [country nationality] pragmatic Q.5: How proud are you of [country] in each of the following?b [Country’s] a rmed forces great-power-civic Its history great-power-civic Its politica l i nf luence in the world great-power-civic/pragmatic [Country’s] economic achievements pragmatic The way democracy works welfare-civic/pragmatic Its fair & equal treatment of all groups... welfare-civic Its social security system welfare-civic Its scientific and technolo gy achievements pragmatic Its achievements in sports pragmatic Its achievements in the arts and literature pragmatic Note: aT he answer categories were: 1. Very im porta nt; 2. Fairly impor tant; 3. Not very important; 4. Not important at all; 8. DK ; 9. NA, refused. bThe answer categories were: 1. Very proud; 2. Somewhat pr oud; 3. Not very proud; 4. Not proud at all; 8. DK; 9. NA, refused. 14This battery on “Importance”, on the other hand, lacks questions about military, glorious past and so on. I definitely needed both batteries in order to cover the whole range of theoretically possible identity constructs. Yet, the juxtaposition of questions of two different types risks obtaining the answers belonging to the same battery clustering together against the other battery, an artifice induced by the number of answer possibilities, wording, and so on. Some “cluster- ing-together” effect seems to have emerged, indeed, but finally the meaning of the answers came through despite these technical hurdles . 15If it is an achievement, it is a reason for pride by default, independent of the domain. In the beginning, I hoped that the “achievements in the arts and litera- ture” item can be used for measuring ethnocultural loyalty, but it turned out that that it shows high correlations only with the other “achievement” measures, and not with the ethnocultural items (such as importance of ancestry) on the “Importance” battery. 16Bulgaria an d Latvia could not be i ncluded because of the lack of the cruci al question on ances try. In the 6-cluster resolution Taiwan and Israel Arabs b reak free from the West-European/Nordic group, and so do Israel Jews from the Latin American group. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 52  A. K. KOOS As my main concern here lies with the difference between the ways in which populations of the advanced countries con- struct their national identity, the principal component analysis below presented is confined to seventeen countries with their GDP per capita in purchase power parity above $25,000 in 2005. This means the first two groups without South Africa and Israel, roughly half of the overall sample. In order to assure that the seventeen peoples contribute to the factors in equal rates, I used, in addition to the design weight provided by the authors of the dataset, a sample correction weight, which rounded up all national samples to 10,000. In all factor resolutions conducted, a tension between focus on military and focus on social security system could be ob- served. Yet, because of their variegated associations with the neutral (pragmatic) variables, the rank order of the factors be- came easily reversed in function of the rotation technique (such as Varimax or Quartimax) used. I sharpened and stabilized the factors by cutting four variables from among the eighteen initial ones. I renounced the “Important to feel national” item, and the three “Pride-in-achievement” questions. On the basis of fourteen variables, an SPSS Equamax rotation reported five principal components cumulatively explaining 6 5.05% of variance. For t he sake of visibility, Figure 3 summarizes the weight of the factors and displays the factor loadings above 0.4 on each. Variables belonging to the ethnocultural imagery are colored with shades of blue, variables pertaining to a welfare-civic vision are shades of red, and the great-power outlook-related variables are brown. Undoubtedly, the opposition and tension between wel- fare-civic and great-power civic outlooks exists in this sample of seventeen developed countries. So as to connect these results to the previous findings on the European Union, we may check on the distribution of factor scores across countries. The coun- try means of the factor-scores calculated by SPSS with the Bartlett method are convergent with the initial clustering of the countries into White immigrant & Anglo-Saxon and West- European & Nordic (Table 3). Here it is mainly the “great power civic” variable that shows a polarization in this sense. No surprise that the US and Great Britain are the highest, and the Germans and Nordics the lowest on it. The “welfare civic” variable is topped by Canada, an immigrant country, but among the countries with an above-average score on it we may notice Switzerland, Denmark, Finland and Norway. Sweden, which we could expect to score high on this variable, satisfies all other related expectations (very low on great power civic, on ethnic, and on religious factors), but here it scores mediocre. We may wonder whether this is related to Sweden’s very high pragmati- cism or not. It is beyond the reach of this paper to speculate about the further evolution of nationalism, after its welfare- civic type. A pure pragmatic approach to socio-territorial com- munities, such as “my fellow men who respect the law and with whom I can communicate”, is one of the possibilities. It falls in the direction of a Habermasian constitutional patriotism, but leaves open the question of the source and content of laws to be respected. (C) The standard Eurobarometer of spring 2010, labeled EB 73.3, asked questions about national identity (QB1), European identity (QB2), and also about whether the respondent felt as- signed by others to any particular group based on his/her skin color, ethnicity, religion, accent, lifestyle and so on (QB15). In principle, these question batteries could have offered the possi- bility to conduct an extensive factor analysis based on all three batteries, but practically, the questions did not cover the whole gamut of possibilities, such as the “great power” imagery has completely been neglected, and the batteries did not well com- plement each other to make comparisons possible. Illustration 4 presents these questions and the frequency with which the respondents chose a certain answer, while Table 4 summarizes the results of the principal component analysis. All questions were formulated as yes/no dichotomies, thus the value of the group mean of each equals the proportion of respondents choosing that particular characteristic. This made possible a fast review of the choices specific to certain coun- tries, and the results are close to what could be expected. Table 5 provides a few examples in this sense. Social protection is 0.805 0.831 0.508 0.747 0.575 0.805 0.601 0.599 0.498 0. 447 0. 850 0. 695 0.594 0.452 0.505 0.655 0.443 0.754 0.788 0.415 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 00% Ethnic - 18.48% Welfare civ ic - 13.06% Great power civic - 11.6 8%R eligious - 11.07% Pragm a tic - 10.77% Factor loadings on the first five principal components P_milit P_histry P_p_infl P_econ P_demcry I_citizn I_rpi nst P_fair P_socss I_speak I_livein I_relig I_bornin I_ancstry Factor load ings on the firs t five princ ipa l compo ne nts Figure 3. Factor loadings above 0.4 on the f irst five principal components Data sourc e: ISSP 2003. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 53  A. K. KOOS Table 3. Country means of the fact o r scores calculat e d fo r the principal com p o n en t re s o l u ti o n i n Figure 3, based on ISSP 2003. Ethnic Welfare civic Great power civic Religious Pragmatic Austria (AT) –0.44 CA –0.41 US –0.75 US –0.76 SE –0.67 Ireland (IE) –0.42 AT –0.30 GB –0.64 IE –0.59 US –0.49 Japan (JP) –0.36 CH –0.29 IE –0.48 AU –0.26 NO –0.47 Spain (ES) –0.28 DK –0.28 AU –0.31 NZ –0.18 FR –0.46 New Zealand (NZ) –0.15 FI –0.14 CA –0.20 DE –0.06 DK –0.41 United States (U S) –0.10 NO –0.13 FR –0.18 GB –0.05 CA –0.35 Taiwan (TW) –0.04 ES –0.13 FI –0.14 ES –0.05 NZ –0.15 Denmark (DK) 0.02 AU 0.00 NZ –0.07 DK –0.05 AU –0.11 Canada (CA) 0.07 IE 0.04 ES 0.05 CH –0.04 AT –0.01 Norway (NO) 0.08 SE 0.11 JP 0.10 AT –0.02 DE 0.01 Germany (DE) 0.09 US 0.12 AT 0.24 CA 0.13 CH 0.04 Finland (FI) 0.13 DE 0.13 CH 0.27 NO 0.22 GB 0.04 Great Britain (GB) 0.13 NZ 0.15 TW 0.35 JP 0.32 FI 0.15 France (FR) 0.22 FR 0.16 DK 0.36 FI 0.32 TW 0.36 Switzerland (CH) 0.28 JP 0.16 NO 0.39 SE 0.47 ES 0.48 Australia (AU) 0.31 GB 0.25 SE 0.46 TW 0.53 JP 0.70 Sweden (SE) 0.58 TW 0.65 DE 0.94 FR 0. 55 IE 1.21 Illustration 4. Socio-territorial identity questions in Eurobarometer 73.3. National identity (QB1) Mentioned % European identity (QB2) Mentioned % Minority identity (QB15) perceived assignment to specific group Mentioned % To have at least one (Nationality) parents 17.9 Your skin color or ethn ic origin 22.0 Your physic al condition or appearance 14.3 Your name 14.8 To be a Chris ti an 8.8 Common religio u s heritage 5.4 Your religion 17.1 To share (Nati o nality) cultural traditions 32.7 Common culture 22.3 Your culture, values, lifestyle 29.8 Your clothe s , the way you are dressed 9.1 To be born in (Our Country) 48.9 Geography 22.4 To have been brought up in (Country) 28.0 Common history 17.3 Your social background 1 4.2 To master (CNTRY/OFF) language 34.0 Your language or accent 34.1 To feel (Nati o nality) 34.4 The single currency, the Euro 36.4 To exercise citizens’ rights, e.g. vot- ing 33.0 Democratic values 31.8 Being active in any association or organization 3.5 A high level of social protection 13.0 Symbols: flag, hymn and motto 10.8 The area where you live 19.1 Your occupation 7.1 Your age 6.9 Note: Sourc e: EB 73.3, frequenc ies calcula ted by applying w22. The sample included 27 countries w/26, 602 respondents; multiple answers were allowed on all 3 items. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 54  A. K. KOOS Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 55 Table 4. Principal component analysis of the Eurobarometer 73.3’s questions about national and European identity. Component 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 QB1 be Christian –0.004 0.000 0.102 0.754 –0.014 0.072 –0.163 –0.057 –0.003 QB1 place of birth –0.114 –0.173 –0.218 –0.015 0.417 0.050 –0.385 –0.346 0.008 QB1 feel nationality 0.011 0.062 0.076 –0.121 –0.881 0.069 –0.106 –0.132 0.050 QB1 cultural traditions 0.003 –0.037 0.426 0.051 –0.074 –0.467 0.126 0.027 –0.221 QB1 parentage 0.003 0.339 0.211 –0.201 0.449 0.325 –0.236 –0.228 0.098 QB1 country/official language 0.042 0.016 –0.029 –0.039 0.045 0.070 0.883 –0.107 0.024 QB1 citizens’ rights 0.111 –0.143 0.441 –0.178 0.115 –0.011 0.107 0.482 0.125 QB1 been brought up 0.006 –0.015 –0.792 –0.101 0.079 –0.071 0.059 0.058 –0.032 QB1 participation 0.006 0.055 –0.099 0.039 0.015 0.033 –0.125 0.825 –0.019 QB2 common history –0.251 0.627 0.031 0.032 –0.022 –0.069 0.074 0.044 0.042 QB2 geography –0.405 0.096 0.029 –0.135 –0.095 0.427 0.029 0.028 –0.628 QB2 democratic val u e s 0.604 –0.054 0.244 –0.136 0.044 –0.096 0.223 0.013 –0.090 QB2 social protection 0.747 0.020 –0.126 0.030 –0.081 0.173 –0.072 0.058 –0.019 QB2 common culture –0.121 0.252 –0.104 –0.093 0.040 –0.743 –0.134 –0.046 0.012 QB2 religious heritage –0.043 0.107 –0. 02 5 0.691 0.074 –0.040 0.112 0.040 0.023 QB2 common currency –0.236 –0.775 0.084 –0.121 0.043 0.112 0.024 0.008 0.088 QB2 symbols –0.211 0.011 0.027 –0.027 –0.068 0.177 0.034 0.034 0.783 Note: Source: EB 73.3. Results obtained with V arimax rotation, while weight w22 has been applied. mainly valued in the Nordic and Post-communist countries, but the Nordics add a strong desire for democracy to this. Religion is more important in the Catholic and Orthodox world, than in the Protestant areas. Since the frequencies by countries are congruent with our as- sumptions related to the construction of national and Euro- pean identity in some countries, we had reasons to expect a principal component analysis also confirming the related hy- potheses. Indeed, Table 4 shows some support for them. Yet, this time it took nine principal components to explain 63.3% of variance, each component being responsible for 6% - 7% of it, which means a quite dispersed distribution. Since there were not questions probing the “great-power civic” attitude, here we only may observe the tension between the “welfare-civic” choices (components 1 and 8) and religious/cultural (compo- nents 4 and 6). The other five principal components can be described as centered on pragmatic things, such as common currency and mastering the country’s official language. Conclusion and Questions for Further Research The principal component analyses confirmed that nationa- lism constructs in the EU and in the advanced countries in ge- neral, have more significant factors than the generally expected two, ethnocultural and civic. They reveal the existence of a kind of nationalism based on the nation conceived of as a self-go- verning community. This factor has emerged as one of the three most important and meaningful principal components in analy- ses. It is civic, as it does not involve the myth of common ori- gin and ancestry, but the concept of state on which it relies diverges from the international relations realist conception of state. The findings have also revealed a specific case of “institu- tional inertia” or “path-dependence”. Traditions of national- ism-constructs in countries shape the ways in which people tend to construct their European identity. The supra-national layers are being cast in the old molds for national-and possibly sub-national, an issue not tested here-identity, though these latter do also change in time. Overall, the findings in this regard do justice to Risse’s “marble cake” model. In addition, as people show more attachment to EU citizens, than to Europeans, it is possible to claim that a civic versus ethnocultural construction of European identity is already preponderant in the EU. Unfor- tunately, the data fails to provide conclusive evidence whether the we-feeling toward EU citizens tends to be of the wel- fare-civic or of the great-power-civic type. I think that the de- gree of compatibility of ethnocultural nationalisms with a Eu- ropean identity involves considerations about the role of the EU in solving ethnic tensions. For instance, Irish ethnocultural na- tionalism is not anti-European, as the EU has had a role in mitigating the conflict in Norther Ireland. n  A. K. KOOS Table 5. Proportion of respondents choosing certain elements of European identity, by country. Qb2 Social protection Qb2 Democratic values Qb2 Religious heritage Mean Mean Mean Lituania 0.29 Sweden 0.71 Poland 0.11 Sweden 0.26 Denmark 0.65 Italy 0.10 Latvia 0.25 Cyprus 0.51 Greece 0.09 Denmark 0.24 Germany W0. 0.47 Romania 0.09 Austria 0.23 Netherlands 0.46 Malta 0.08 Estonia 0.23 Luxembourg 0.44 Austria 0.06 Germany Easta 0.21 Austria 0.40 N0. Ireland 0.06 Germany West 0.20 Belgium 0.40 Cyprus 0.06 Cyprus 0.19 Germany E0. 0.38 Hungary 0.05 Finland 0.18 Finland 0.36 Slovakia 0.05 Luxembourg 0.17 France 0.35 Gr0. Britain 0.05 Netherlands 0.17 Lituania 0.34 Lithuania 0.04 Malta 0.16 Italy 0.32 Germany W0. 0.04 Belgium 0.16 Malta 0.32 Finland 0.04 Bulgaria 0.15 Czech Rep0. 0.31 Slovenia 0.04 Czech Rep0. 0.14 Hungary 0.31 Bulgaria 0.04 Hungary 0.14 Estonia 0.29 Germany E0. 0.03 Romania 0.14 N0. Ireland 0.29 Denmark 0.03 Slovakia 0.13 Bulgaria 0.28 Czech Rep0. 0.03 Italy 0.12 Slovakia 0.27 France 0.03 N0. Ireland 0.12 N0. Ireland 0.26 Netherlan ds 0.03 Greece 0.11 Gr0. Britain 0.25 Ireland 0.03 Ireland 0.10 Slovenia 0.25 Belgium 0.03 Slovenia 0.10 Latvia 0.23 Estonia 0.03 Gr0. Britain 0.10 Romania 0.23 Luxembour g 0.02 France 0.09 Greece 0.19 Spain 0.02 Spain 0.07 Portugal 0.18 Latvia 0.02 Poland 0.06 Poland 0.18 Portugal 0.02 Portugal 0.06 Spain 0.16 Sweden 0.02 EU average 0.16 EU average 0.33 EU average 0.05 Note: aThe Eurobarometer surveys still distinguish between East and West German samples, which may occasionally be very useful for tracing the heritage of a communist ast. In this table, for instance, a “less-interest-in-democratic-values” effect comes through convincingly. p Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 56  A. K. KOOS The practical consequences of these findings for regional, particularly European, integration are that a historical shift from great-power civic nationalisms to welfare-civic nationalisms works for the smooth inclusion of a supra-national layer into the socio-territorial allegiance structure. The constitutional patriot- ism-type European identity (as proposed by Habermas (2003)) may be the most successful in countries with a tradition of wel- fare-civic nationalism. Countries with ethnocultural nationalism traditions may experience more difficulty in integrating a consti- tutional-patriotism-type European identity, but they won’t turn against the EU until it is a solution to their ethnic problems. Unfortunately, there is a serious tension arising from the fact that citizens of the countries with the best welfare arrangements are the most opposed to the neoliberal economic policies push- ed forward by Brussels. Fear of downsizing the welfare system has been at the heart of Nordic Euroskepticism. It seems that the EU is seriously incapacitated in benefiting of the “cultural match” between some countries welfare-civic nationalist out- look and the shared values promoted in the self-definition of the superpolity, and enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights. Yet, the presence or absence of similar “cultural matches” should not be omitted from the research agenda on which European policies are based. Since we may claim that existing types of nationalisms constrain the way in which European identity is being constructed, logically we should admit that types of nationalisms constrain the images of European integra- tion, that is, the bl u ep ri n ts for integration endorsed by people. As for further research in this domain, the empirical work is constrained by the availability of survey data. Eurobarometer 57.2 is a unique dataset in the sense that it has been the only one asking about the structure of a European allegiance thus far. Unfortunately, it is confined to a small selection of European countries, and its results cannot be safely generalized, not even for the whole of the EU, let alone for beyond the continent. ISSP 2003 provides more information about the emergence of a welfare-civic nationalism in the global arena. Yet, despite the much larger sample, ISSP does not contain really poor and backward countries, or Muslim countries, for comprehensive comparisons17. In addition, the survey questions are less suit- able for reconstructing the underlying dimensions. On the positive side, ISSP has the potential that the 2003 findings be compared with the earlier ISSP of 1995 on National Identities, and with new results expected in 2013, when ISSP intends to carry out a third wave of national identity research. These analyses could give us clues about the temporal direction and speed of change of nationalisms. Socio-territorial loyalties are strong forces with a sad his- torical record of having authorized deadly violence, as well as other inhuman means applied to “outgroups”. We cannot over-emphasize the importance of obtaining unbiased, reliable knowledge about the nature and dynamics of these allegiances. Less dramatically, within the EU, more knowledge about na- tionalisms and their relationship with a supranational identity, can rightly be expected to foster sounder policies of integration. REFERENCES Brown, D. (2000). Contemporary nationalism: Civic, ethnocultural, and multicultural politics. London: Rou tle dg e. Brubaker, R. (1992). Citizenship and nationhood in France and Ger- many. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511558764 Brubaker, R. (1996). Nationalism reframed: Nationhood and the na- tional question in the New Europe. Cambridge, MA: Cambridg e Un i- versity Press. Caporaso, J. (1996). The European Union and forms of state: West- phalian, regulatory or post-modern? Journal of Common Market Stu- dies, 34, 29-52. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5965.1996.tb00559.x Chandra, K. (2001). Introduction: Constructivist findings and their non-incorporation. Symposium: Cumulative Findings in the Study of Ethnic Politics, 12, 7-11. Glendening, M. (2005). Post-modernism & the silent revolution. Euro- pean Journal, 2005. http://www.democracymovement.org.uk/postmod Greenfeld, L. (1992). Nationalism: Five roads to modernity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Greenfeld, L., & Eastwood, J. (2007). National identity. In C. Boix, & S. Stokes (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative politics, New York: Oxford. Habermas, J., & Derrida, J. (2003). February 15, or what binds Euro- peans together: A plea for a common foreign policy, beginning in the core of Europe, Constellations: An International Journal of Critical & Democratic Theory, 10, 291-298. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.00333 Herb G. H., & Kaplan D. H. (1999). Nested identities, nationalism, territory, and scale. New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. Koos, A. K. (2007). Utilitarian explanations of support for the Euro- pean Union. Paper presented at the midwestern political science as- sociation’s annual conference in Chicago. http://www.mpsanet.org/Conference/ConferencePaperArchive/tabid/ 681/Default.aspx Kra, P. (2002). The concept of national character in 18th century France. Cromohs, 7, 1-6. http://www.cromohs.unifi.it/7_2002/kra.html Lijphart, A. (1999). Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press. Medrano, J. D., & Gutiérrez, P. (2001). Nested identities: National and European identity in Spain. Ethnic & Racial Studies, 24, 753-780. doi:10.1080/01419870120063963 Nikolas, M. M. (1999). False opposites in nationalism: An examination of the dichotomy of civic nationalism and ethnic nationalism in modern Europe. www.nationalismproject.org/pdf/Nikolas.pdf Özkirimli, Umut (2000). Theories of nationalism. London: Macmillan Press. Reicher, S., & Hopkins, N. (2001). Self and nation: Categorization, contestation and mobilization. New York: Sage Publishers. Risse, T. (2005). Neofunctionalism, European identity, and the puzzles of European integration. Journal of European Public Policy, 12, 291-309. Robyn, R. (2005). The changing face of European identity. London: Routledge. Smith, A. D. (1998). Nationalism and modernism: A critical survey of recent theories of nations and nationalism. London: Routledg e. Spiering, M. (1999). The future of national identity in the European Union. National Identities, 1, 151-159. doi:10.1080/14608944.1999.9728108 Tilly, C. (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states, AD 990-1990. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Van Evera, S. (2001). Primordialism lives! APSA-CP: Newsletter of the Organized Section in Comparative Politics of the American Political Science Association , 12, 20-22. Walzer, M. (1990). What it means to be an American. Social Research, 57, 591-614. Yashar, D. (2005). Contesting citizenship in Latin America: Indigenous movements and the postliberal challenge. Cambridge, MA: Cam- bridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511790966 17In this sample o f 33 countries, the trends d etected for the advanced group hold for others as well, though the principal components are less crisp for the whole sample. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 57  A. K. KOOS Appendix Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y. M., Johnston, A. I., & McDermott, R. (2006). Identity as a variable. Perspectives on Politics, 4, 695-711. doi:10.1017/S1537592706060440 Anderson, B. (1983). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. New York: Verso. Bendix, R. (1964). Nation-building and citizenship: Studies in our changing political order. New York: Wiley. Breakwell, G. M. (2004). Identity change in the context of the growing influence of European union institutions. In R. K. Herrmann, T. Risse, & M. B. Brewer (Eds.), Transnational identities: Becoming European in the EU (pp. 25-39). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. Brewer, M. B. (2007). The importance of being we: Human nature and intergroup relations. American Psychologist, 62, 728-738. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.728 Bruter, M. (2003). Winning hearts and minds for europe. Comparative Political Studies, 36, 1148-1180. doi:10.1177/0010414003257609 Bruter, M. (2004). On what citizens mean in feeling “Euro- pean”: Perceptions of news, symbols and borderless-ness. Journal of Ethnic & Migration Studies, 30, 21-40. doi:10.1080/1369183032000170150 Caporaso, J. A. (2005). The possibilities of a European iden- tity. Brown Journal of World Affairs, 12, 65-75. Chandra, K. (2006). What is ethnic identity and does it mat- ter? Annual Review of Political Science, 9, 397-424. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.062404.170715 Chatterjee, P. (1993). The nation and its fragments: Colonial and postcolonial histories. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Checkel, J. T. (1999). Norms, institutions and national iden- tity in contemporary Europe. International Studies Quarterly, 43, 83-114. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00112 Delanty, G. (2005). What does it mean to be a “European”? Innovation: The European Journal of Social Sciences, 18, 11- 22. Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and nationalism. Oxford: Black- well. Gellner, E. (1997) Nationalism. New York: New York Uni- versity Press. Haas, E. (1986). What is Nationalism and why should we study it? International Organization, 40, 707-744. doi:10.1017/S0020818300027326 Herrmann, R. K., Risse , T., & Brewer, M. B. (2004). Trans- national identities: Becoming European in the EU. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. Hobsbawm, E. J. (1992). Nations and nationalism since 1780: Programme, myth, reality (2nd ed.) Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Horowitz, D. L. (1985). Ethnic groups in conflict: Theories, patterns, and policies. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Horowitz, D. L. (1991). A democratic south Africa? Consti- tutional engineering in a divided society. Berkeley, CA: Uni- versity of California Press. Lecours, A. (2005) Structuring nationalism. In A. Lecours (Ed.), New institutionalism: Theory and analysis. Toronto: Uni- versity of Toronto Press. McLaren, L. (2006). Identity, interests and attitudes to Eu- ropean integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Moore, M. (2001). The ethics of nationalism. Oxford Univer- sity Press. Oommen, T. K. (1997). Citizenship, nationality and ethnicity: Reconciling co mpe ti ng identities. New York: Polity Press. Shulman, S. (2002). Nationalist sentiments and globalization preferences in five great powers. Global Society, 16, 47-68. doi:10.1080/09537320120111906 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 58

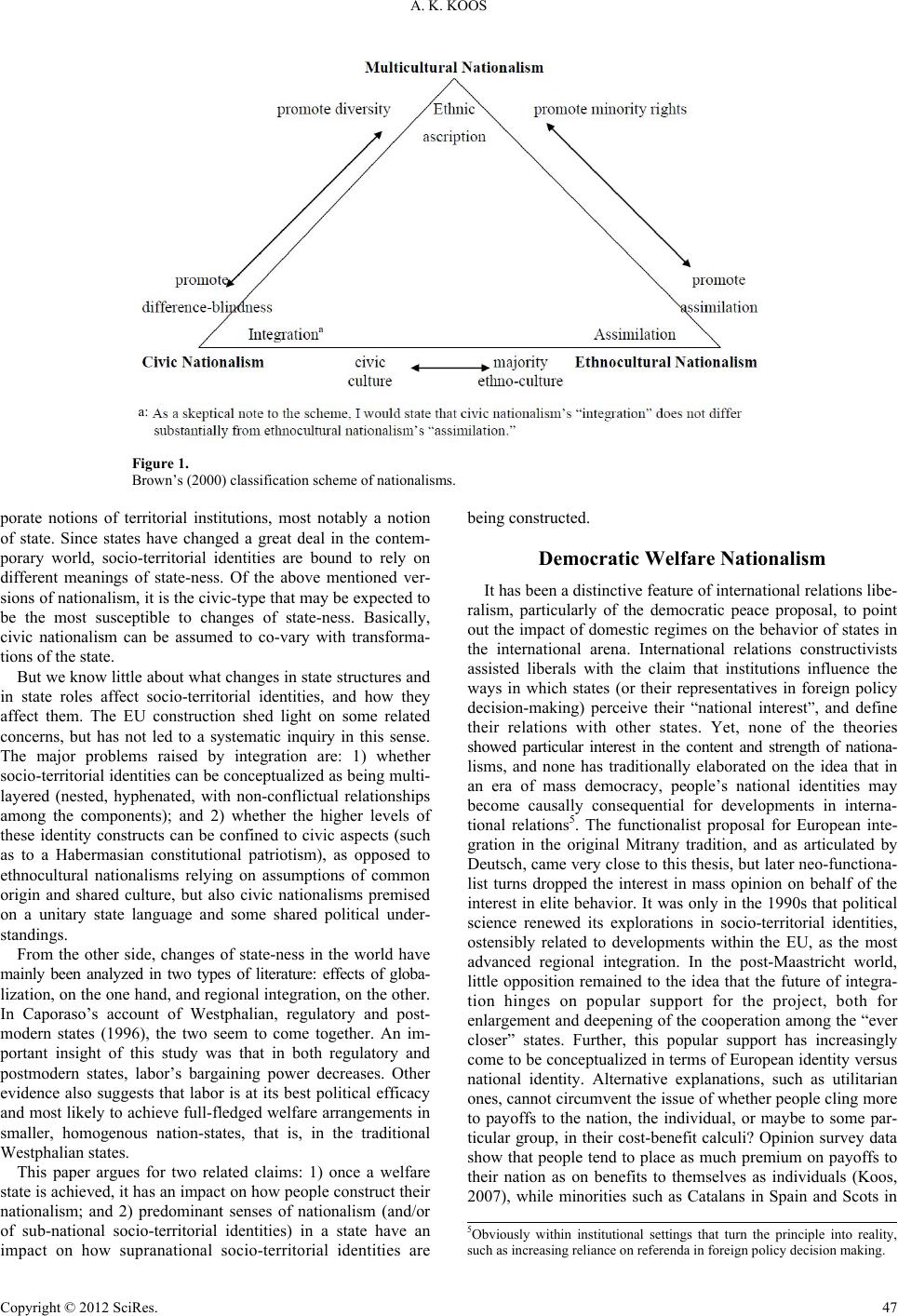

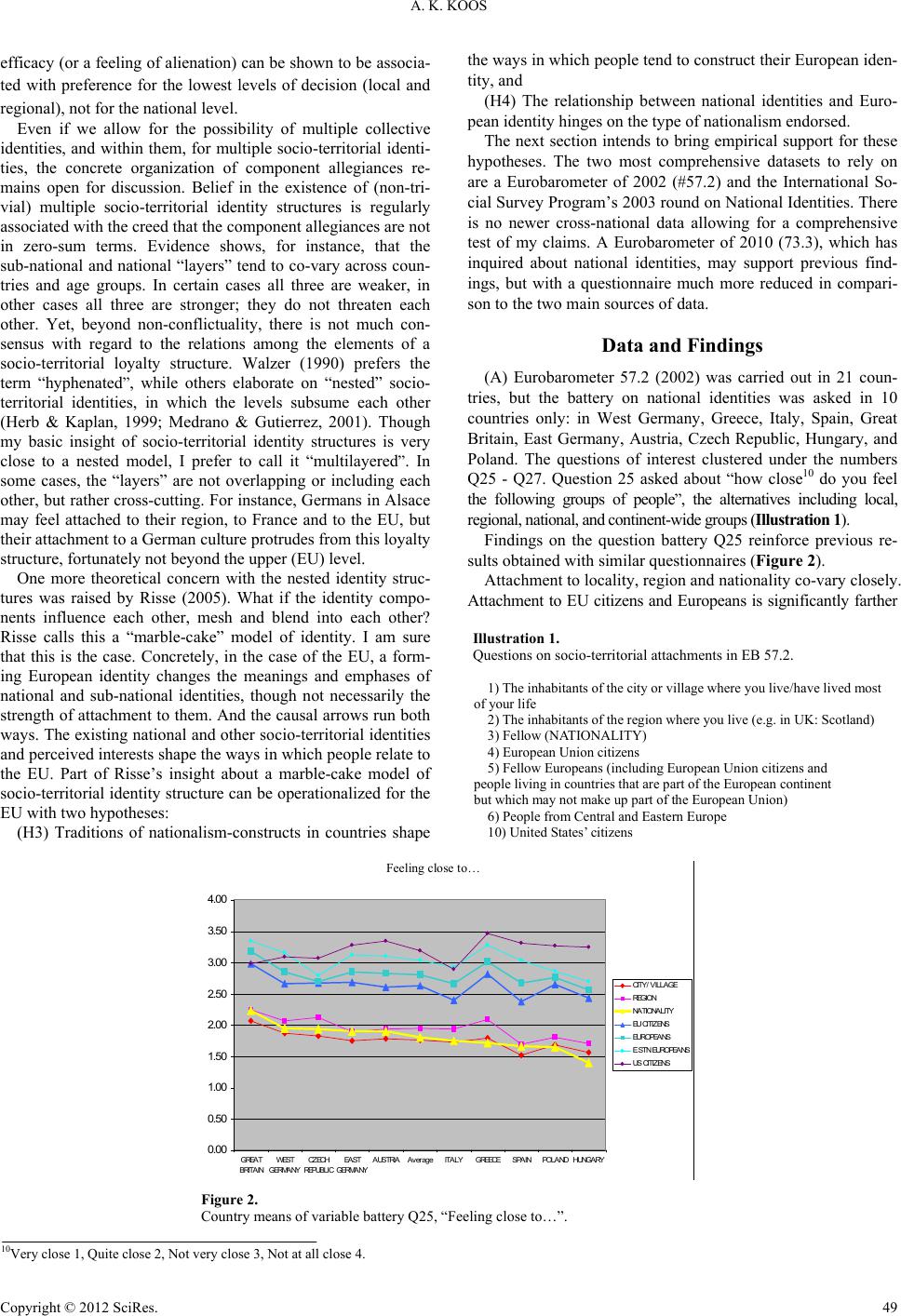

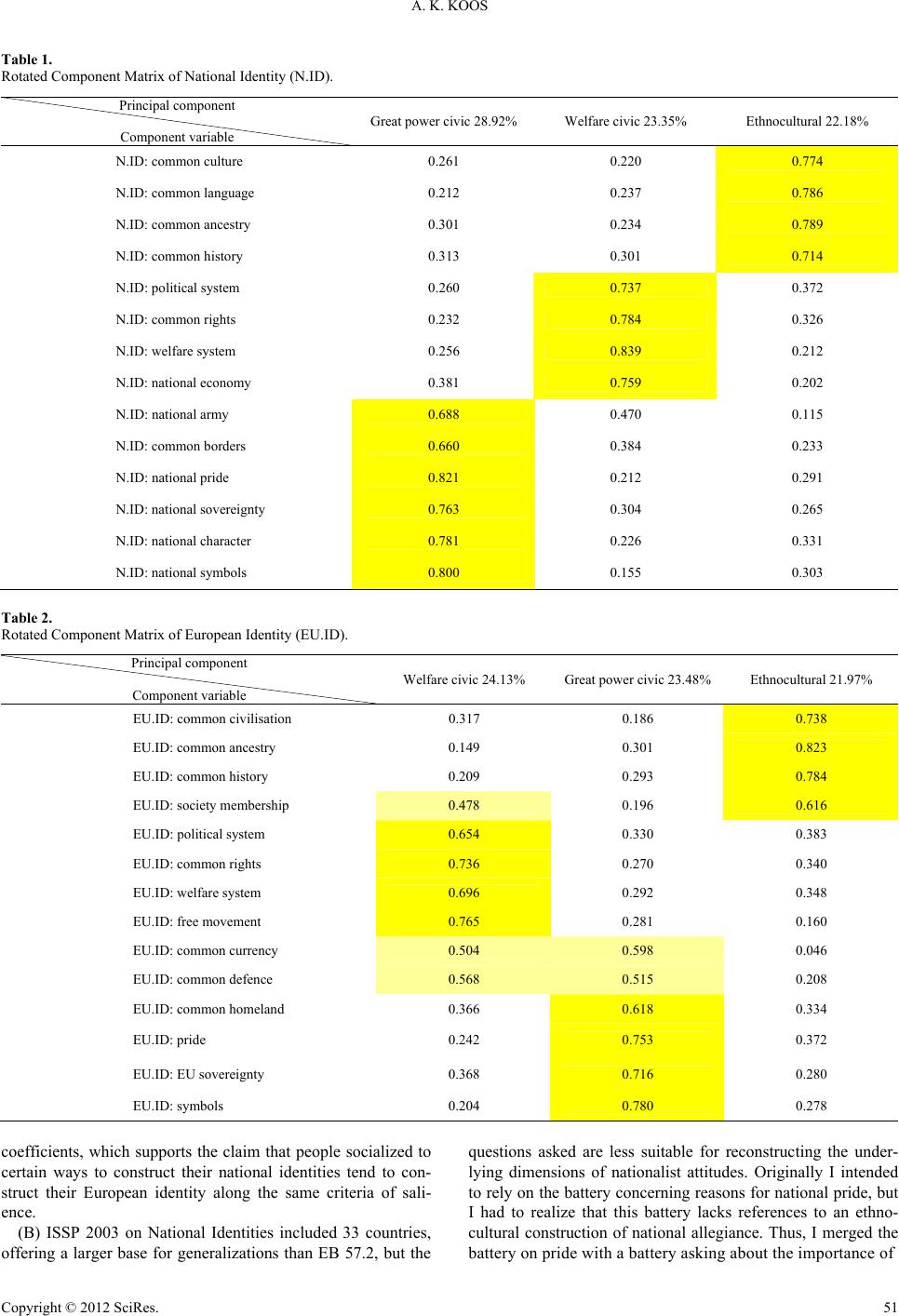

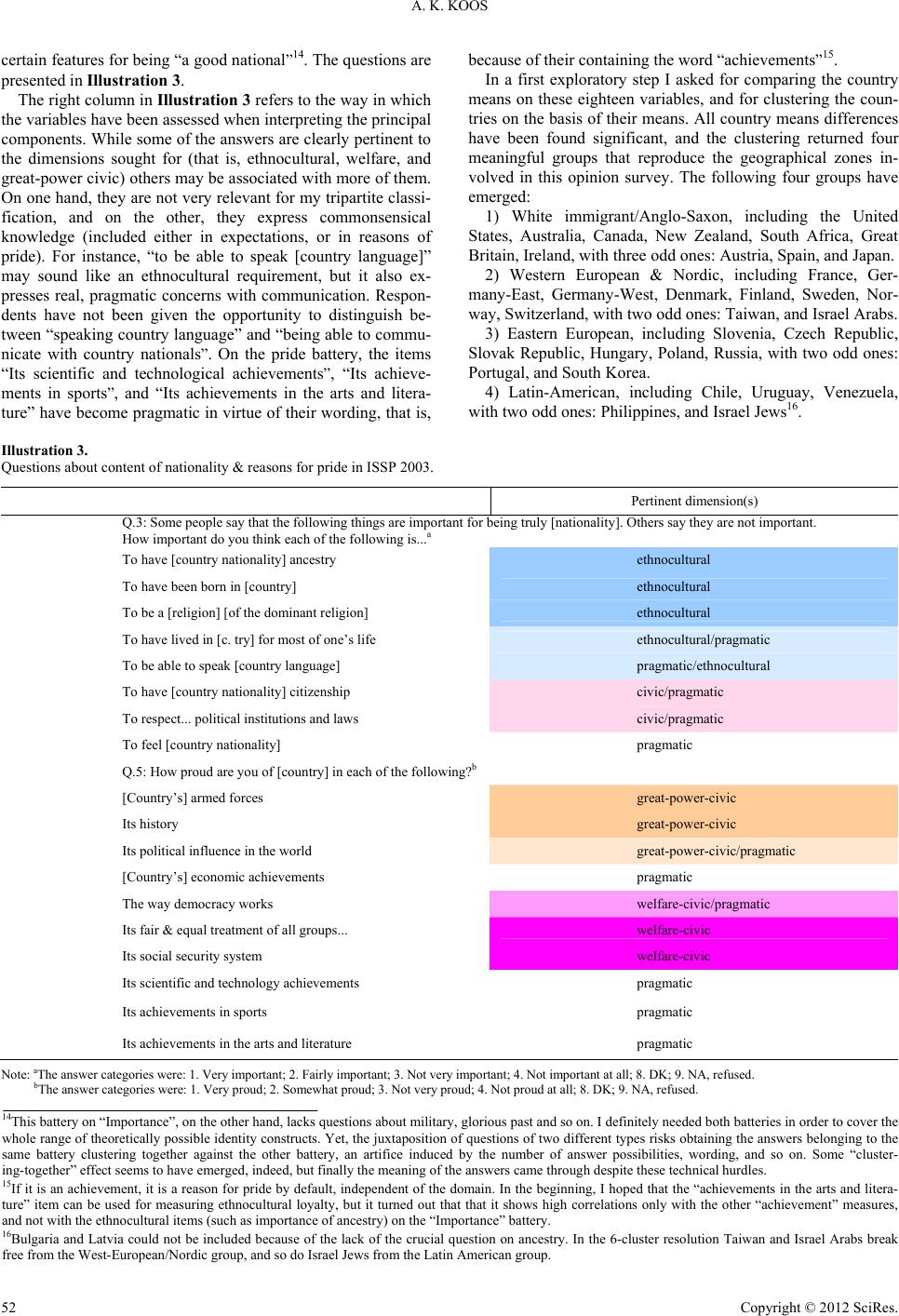

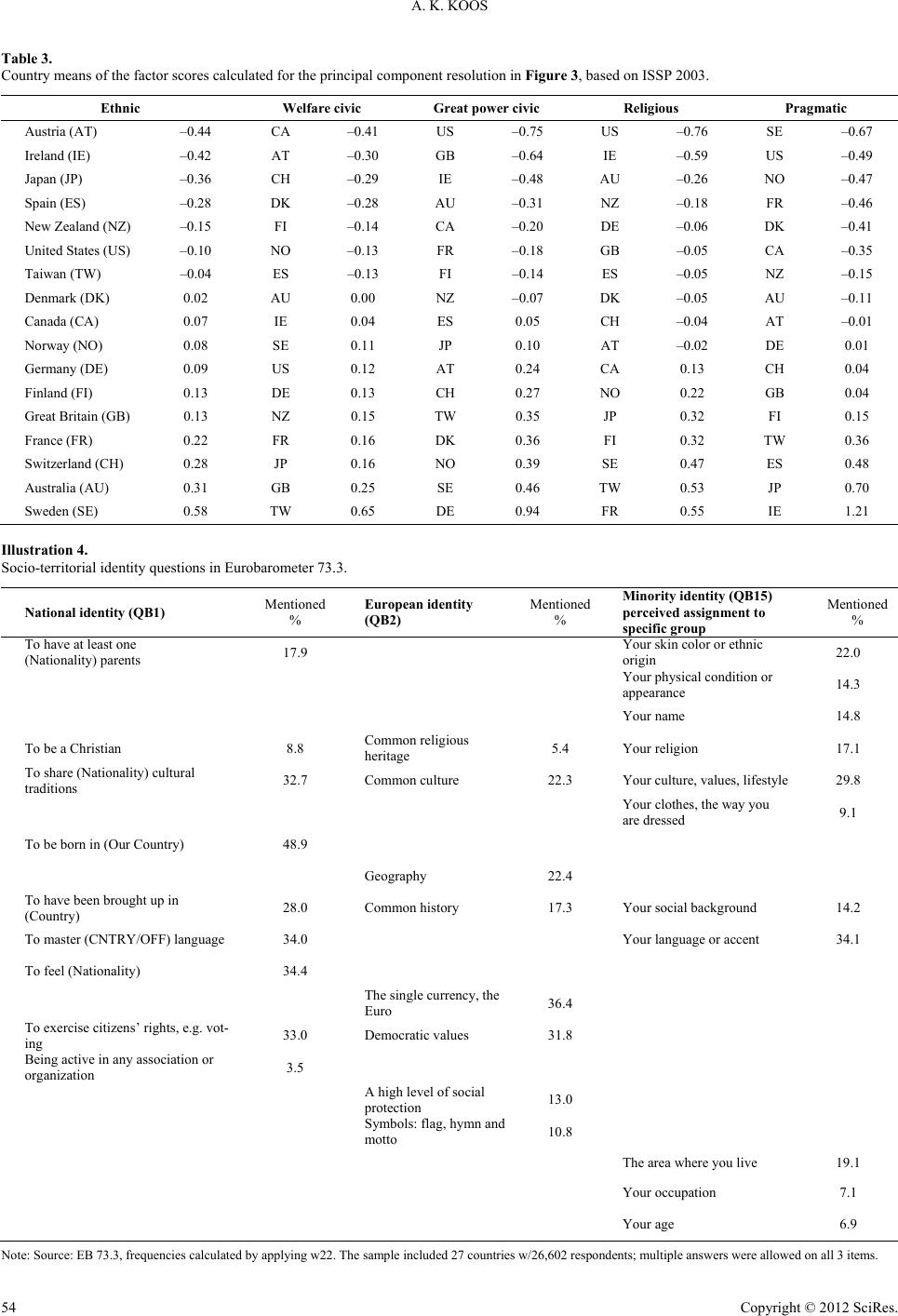

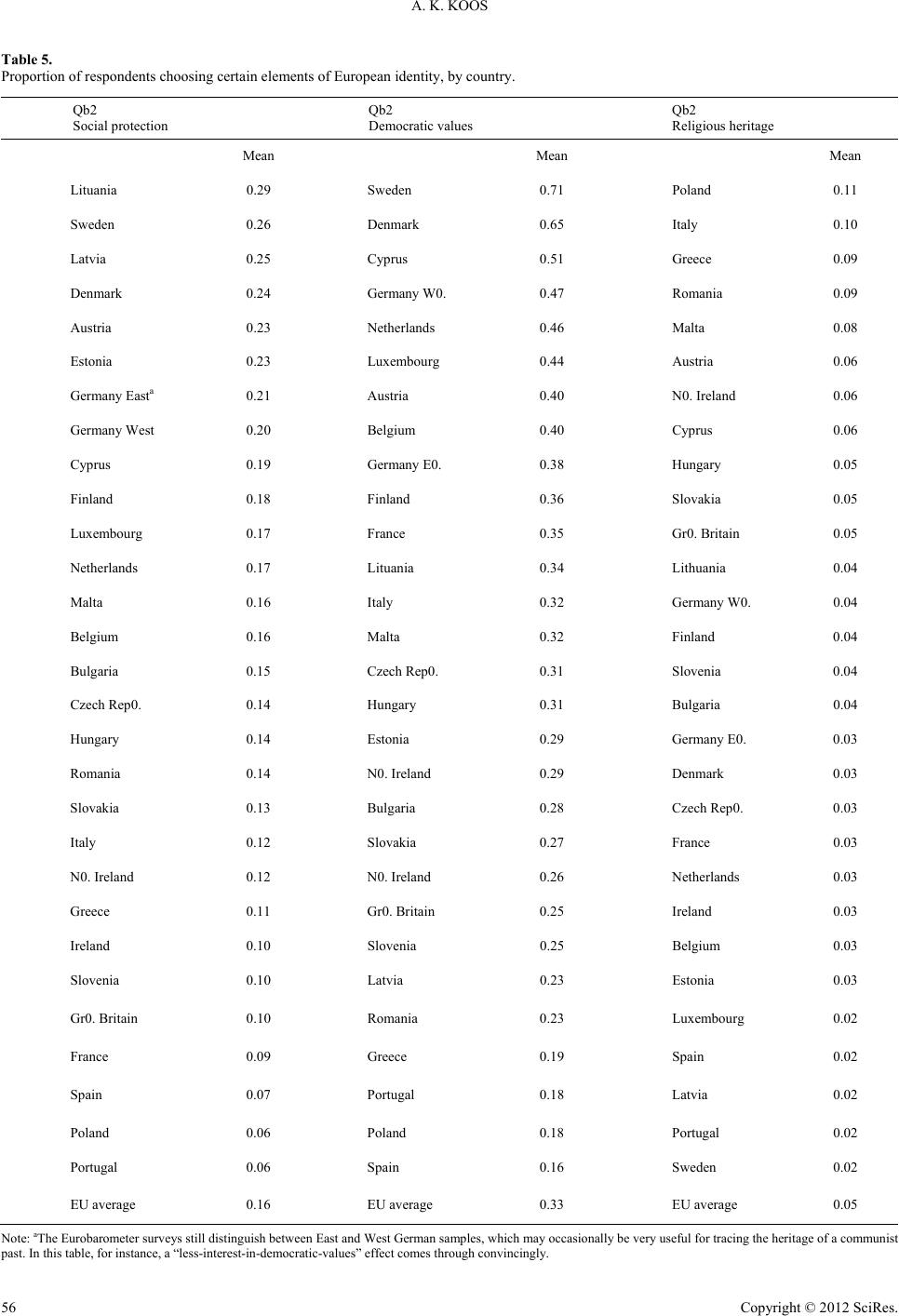

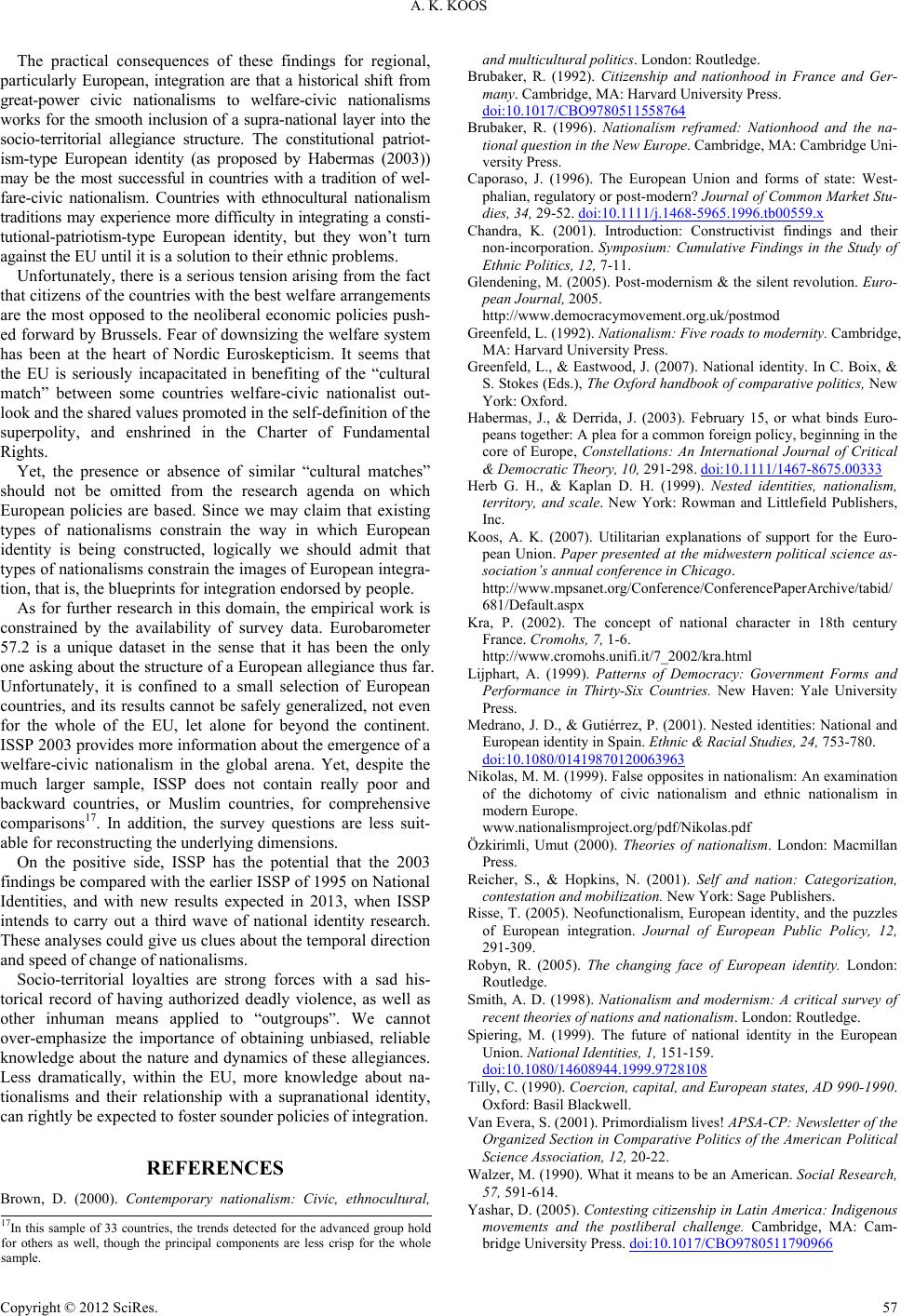

|