Open Journal of Psychiatry, 2012, 2, 284-291 OJPsych http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2012.24040 Published Online October 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojpsych/) Depression as a risk factor for coronary heart disease—How strong is the evidence? Hans G. Stampfer, Dana A. Hince, Simon B. Dimmitt School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience and School of Medicine and Pharmacology, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia Email: hans.stampfer@uwa.edu.au Received 9 July 2012; revised 12 August 2012; accepted 23 August 2012 ABSTRACT A critical appraisal is made of the evidence that de- pression is a causal risk factor for coronary heart disease. PubMed and Science Citation Index were searched for relevant papers. Forty eight papers sa- tisfying inclusion criteria and reporting an associa- tion between a measure of depression and a coronary disease outcome were compared in terms of baseline assessment, exposure and endpoint definition, covari- ates measured and whether changes in, or treatment of, depression was assessed during follow-up. There was considerable variation in the definition of de- pression and coronary heart disease and contradic- tory findings are reported. Conventional risk factors for coronary heart disease were not assessed consis- tently or adequately. Only three of the forty-eight pa- pers gave consideration to the time course of depres- sion during follow-up and prior to study entry. Po- tentially confounding variables such as anxiety, per- sonality traits and other psychiatric disorders were not taken into consideratio n in the majority of papers. Treatment of depression during the follow-up period was not mentioned in any of the papers. In light of identified methodological shortcomings and the incon- sistent findings reported we suggest that there is as yet no convincing evidence that depression is an inde- pendent causal risk factor for coronary heart disease. Keywords: R eview; Depression; C or o nary Heart Disease (CHD) 1. INTRODUCTION Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of “quality fil- tered” prospective studies have repeatedly concluded that depression is a risk factor for coronary heart disease (CHD) [1-4] and although the validity of this conclusion has been challenged [5-9] the majority of published re- ports support it. In 2003, a “position statement” by a panel of experts [10] asserted that depression is an inde- pendent risk factor for CHD, equal in magnitude to es- tablished risk factors such as hypertension and obesity. Depression is a high prevalence disorder and the World Health Organization has predicted that by 2020, depres- sion and CHD will be the two leading causes of disability- adjusted life years in developed countries. If this predic- tion proves to be correct and depression is a proven risk factor for CHD, it follows that depression will contribute substantially to the incidence of CHD. The suggested causal link between depression and CHD should not af- fect expected diligence in the diagnosis and treatment of depression—any reduction in CHD resulting from effec- tive treatment of depression should simply be an added benefit. However there is a risk that awareness and en- dorsement of the suggested link might contribute to an over-diagnosis/treatment of depression and worry about CHD by individuals diagnosed with depression. These consequences would be particularly unfortunate if there was no justification for the endorsement and the aim here is to show that the evidence in support of the suggested link is far from conclusive. 2. SEARCH STRATEGY AND SELECTION CRITERIA 2.1. Study Eligibility Studies were included if they described a prospective cohort design, considered the relationship between depres- sion and CHD and reported an association statistic for this relationship. Selected studies treated “depression” as the primary exposure or covariate and included fatal and non-fatal outcomes of CHD. Selected studies defined “de- pression” by self-report, symptom scale score, question- naire-based personality dimension or clinical diagnostic criteria defined in “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual” (DSM) and “International Classification of Diseases” (ICD). Studies relying on antidepressant prescription as a proxy for depressio n [11] were excluded, as were studies that included combined cardiovascular endpoints (e.g. CHD and stroke) or non-specific “heart disease” [12,13]. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 285 2.2. Search Strategy We used a modified version of the search strategy adopted by Kuper et al. [1]. This strategy combines a conven- tional subject-heading search in PubMed with citation tracking through the Science Citation Index (SCI). The citation tracking includes a forward search (finding pa- pers citing those identified in an index review) and a backward search (finding papers citing studies listed in the reference lists of papers identified in the index re- view). This strategy has been shown to identify more relevant papers than a PubMed search alone, particularly papers reporting a null result [1]. We limited the SCI search to the forward citation-tracking component. Nicho- lson et al. [5] was taken as the index review. Papers ref- erenced in this review that met the selection criteria de- fined above were entered into the SCI to identify papers that cited these studies. Both the SCI and PubMed sear- ches were limited to English publications. 2.3. Data Extraction Information about the following variables was extracted from selected studies: Cohort details; positive/null trial (“positive” if association statistic p < 0.05 was found in at least one of the relevant analyses); association statistic; duration of follow-up; exposure details; wheth er existing CHD or cardiovascular disease (CVD) was excluded at baseline; endpoint details; whether depression was as- sessed during follow-up and covariates measured. A meta- analysis was not attempted, as we were not interested in the combined effect size across studies, but in the details of the individual studies that are often obscured in meta- analyses but are of vital importance to understanding the significance of a reported association. 3. RESULTS The number of studies identified by each search strategy and the number meeting inclusion criteria are shown be- low in Table 1. The study variables considered in this review are summar ized below in Tabl e 2. Forty-eight published arti- cles based on 36 cohorts were included. Depression was considered a covariate in 5 studies [14-18] and the prim ary or one of the primary exposures in the remaining 43 studies. Sample size varied from 76 [19] to 73,098 [20]. The populations studied varied considerably in age and included “healthy” men and women, war veterans, hy- pertensive and diabetic patients. Thirty seven percent (37%) of papers included in this review reported a posi- tive result for all relevant endpoints/group analyses, 29% reported mixed results and 33% found no relationship between depr ession and CHD. No association was found between positive findings and whether CHD/CVD was excluded at baseline ( 2 1 = 0.39, p = 0.53) or whether depression was treated as a primary exposure variable or covariate ( 2 1 = 0.05, p = 0.82). However there was an association between positive findings (as defined above) and the definition of “depression”, with 100% positive findings in the 17% of studies that used DSM or ICD diagnostic criteria, rather than symptom scale/self report scores. ( 2 1 = 5.27, p = 0.02). Positive findings were also related to sample size. Seventy five percent (75%) of studies with n < 3000 but only 47% with n > 3000 showed a positive relation ship ( 2 1 = 3.74, p = 0.051). 3.1. Exposure and Endpoint Definitions The definition of depression and CHD varied considerab- ly across studies. Only 17% of studies used DSM or ICD diagnostic criteria and/or clinical interview to determine depression. The remaining 83% of studies used various symptom rating scales. The most common were the Cen- tre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES- D), (29%) and various subscales of the Minnesota Mul- tiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) (15%). CHD was measured by fatal (e.g. myocardial infarc- tion, MI), non-fatal (e.g. angina, angioplasty, coronary artery bypass grafting) and combined endpoints that were based on medical records, death certificates, self-report and/or hospital records. Multiple endpoints were often considered in a single study, resulting at times in con- flicting results [27,45]. 3.2. Removal of CHD at Baseline Twenty percent (20%) of studies did not report the ex- clusion of participants with evidence for CHD/CVD at baseline, although three of these studies [18,51,54] at- tempted to control for this by using baseline eviden ce of Table 1. Number of papers identified and meeting eligibility criteria for the review from the 3 sources accessed. Source No. papers identified No. papers included Index papers - 23 PubMed 1691 20 SCI 1084 35 Total number of papersa - 48 a13 papers were included through SCI a n d PubMed searches; 17 pape rs were included t hrough both the index review and SCI searches. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 286 Table 2. Definition of depression and covariates included in studies. Number of studies reporting: % (n) References At least one significant associationa 65% (31) [14,15,18,19,21-47] Depression defined by: DSM/ICD criteria 17% (8) [19,21,23,32,3 7-39,42] Single question self-report 6% (3) [17,18,46] Symptom scale 77% (37) [14-16,20,22,24-31,33-36,40,41,43-45,47-61] Controlled for CHD/CVD at baselineb 81% (39) [14-17,20-27,29-37,39-43,45-49,52,53,55-59,61] Covariates measuredc: Anxiety (symptom/personality scale) 12% (6) [15,16,30,49,52,56] Other psychiatric comorbidity 2% (1) [39] Other psychological constructs 19% (9) [15-17,27,30,48,49,52,56] Lipids/Cholesterol 58% (28) [15,16,19,20,22-24,26,30,32-35,38,40,41,43,46-53,56,57,61] Blood pressure 81% (39) [15-17,19,20, 22-26,30,32-43,45-58,60,61] Diabetes/BGL 60% (29) [15,17-20,22-26,32-40,42,45,46,49,50,54,55,57,59,61] Other medical comorbidity 40% (19) [17,18,22-26,29,34,39,40,42,46,51,54,55,57,59, 6 0 ] BMI 65% (31) [17-20,22,23,25,30,32-38,41-43,45-47,49,50,52-54,56-58,60,61] Waist-hip or waist circumference 10% (5) [23,24,26,37,58] Physical activity 37% (18) [17,20,22-2 4,26,32,33,35 ,40,41,45,47 ,50,53,56,57,60] Smoking 83% (40) [15,17-20,22-26,30,32-43,45-61] Alcohol and/or substance u s e 52% (25) [17,22,25,30,32-35,37-40,42,43,45-47,51,53,54,56-58,60,61] Antidepressant use at baseline 10% (5) [32,37- 3 9,45] Family Hx CHD 12% (6) [22,30,35,38,43,57] Age 83% (40) [14-20,22,24-26,29-37,39-44,46-49,51,52,54-61] Sexd 96% (46) [14-43,45-49,51-61] Ethnicity 21% (10) [14,20,33,40,45-47,51,55,59] Marital status 31% (15) [16,18,23,31,33,34,36,37, 39 ,40,45-47,55,60] Education 40% (19) [16,20,30,34-37,39,40,42,46,47,51,53,55,57-60] SES 17% (8) [20,23,32,36,45,52,55,56] Change in depression across follow-u p period 6% (3) [38,40,59] Change in other risk factors across follow-up period 2% (1) [38] Treatment for depression during follow-up period 0% (0) N/A aStudies often report separate analyses for different groups or have multiple relevant endpoints. Only one association (based on the multivariate adjusted asso- ciation if reported) needed to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) in order to be considered a positive study; bSome attempt was made in at least one analysis to exclude p articipants with evidence of C HD at baseline; cAll covariates measu red are reported in the table, i rrespective of whet her it was in cluded in the fi nal model reported; dSex w as cons id ered a co var iat e ( n = 2 3) OR on ly on e s ex was included in the study (n = 18) OR men and women were analysed separately (n = 6). CHD as a covariate. The definition of “evidence of CHD/ CVD at baseline” was highly variable across studies as were criteria for exclusion. For example, in some stud- ies participants were excluded if there was a history or evidence of angina, previous MI, ischemia on ECG, coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous translu- minal coronary angioplasty [36]. In other studies, indi- viduals with self-report of previously diagnosed heart disease were included [47]. The criteria used to deter- mine whether CHD was present at baseline were not always stated. 3.3. Control for Recognized Risk Factors Figure 1 shows the percentage of studies that controlled for indicated risk factors. It can be seen that hypertension, smoking and family history of CHD were controlled for in around 80% of studies but that significantly less con- sideration was given to other recognized risk factors and potentially relevant variables. Some studies measured a covariate but did not take it into consideration in the re- ported model or in any analysis relevant here. Hence Figure 1 probably overestimates the degree of control for possible confounding factors. In addition, interactions Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 287 % Figure 1. Percentage of studies that controlled for indicated risk factors for CHD. between covariates were rarely considered [56]. This is probably due to insufficient sample size for assessing potential interactions but the resulting lack of informa- tion regarding the relationship between confounding variables limits understanding of the primary association of interest. 3.4. Control for Psychosocial Variables Apart from Depression Figure 2 shows the percentage of studies that controlled for the broadly termed “psychosocial” variables indicated. Psychological variables including anger, hostility, g eneral distress, vital exhaustion, social support and several measures of anxiety were considered as potential covari- ates in only 21% of studies. The failure to control for anxiety in 85% studies is surprising considering the fre- quent co-morbidity of anxiety and depression [62]. Pratt [39] found that the addition of panic disorder, phobia and alcohol and drug dependence did not significantly affect the depression/CHD association. Davidson [15] found depressive symptoms (CES-D) to significantly predict CHD events when anxiety (among other covariates) was included in the model. On the other hand Shen et al. [16] reported that the significant association between anxiety (MMPI scale) and CHD remained when depression and other personality/emotional variables were included as a covariate in the analyses and that depression was not sig- nificant in the model. Kubzansky [30] report ed de press ion (MMPI-derived scale) did not predict CHD when entered into the model alone, or in the prese nce of anxiet y, ang er or general distress measures (also MMPI-derived). Boyle et al. [49] found that in men CHD was signifi- cantly associated with depression, anxiety, anger and hostility in individual models. However a single model including these four potential predictors did not find any of them significant. A composite score accounting for 66% of the shared variance between the four variables did significantly predict CHD and was a better predictor than depression. Two studies [52,56] did not include anxiety as a covariate because the association between % Figure 2. Percentage of studies that controlled for indicated psychosocial variables. depression and CHD was not significant in initial analy- ses. 3.5. Variations in Depression Prior to and during Follow-Up Only 8% of studies measured changes in depression across the follow up period, only 4% gave consideration to depression prior to baseline and no studies gave con- sideration to the treatment of depression during follow- up. The poverty of information about depression apart from a baseline rating with considerable variation in rat- ing methods precludes any firm conclusion about a dose- effect relationship that would support a causal role of depression in CHD. 4. DISCUSSION A critical examination of the inconsistencies and meth- odological shortcomings in primary studies along with the contradictory findings reported leaves serious doubt about the extent to which depression can be regarded as an independent risk factor for CHD. As noted by other authors [5,6] and recognized in this review, inadequate control for conventional risk factors fails to rule out a mediating factor or factors for the suggested relationship and inadequate removal of CHD cases at baseline fails to rule out reverse causality, two pre-requisites for reaching any firm conclusion about a causal role for depression. Furthermore no systematic attention has been given to co-morbid psychological variables or psychiatric disor- ders that may have contributed to, or better accounted for, the association between depression and CHD. Reported findings are contradictory and difficult to integrate given the variation in statistical approaches and exposure defi- nition, which is a likely consequence of most studies not being designed specifically to question the role of de- pression in CHD. This review gave emphasis to anxiety, as it is highly comorbid with depression, but other psy- chological and psychiatric variables might also have con- tributed a confounding effect. Inconsistencies are evident in the definition and mea- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 288 sure of exposure and endpoints. In particular, there is he- terogeneity in exposure measures (different scales, cli- nically or symptom defined, differing cut-offs, dichoto- mous v continuous), endpoint definitions (e.g. fatal CHD, angina, non-fatal MI, or combination outcomes) and in subgroup analyses (usually based on gender). This situ- ation is further complicated by the fact that these be- tween study differences are sometimes observed within studies, where separate analyses for different outcomes, different exposure categorizations, or different subgroups are reported and on occasion yield conflicting results [43,45]. It is also worth noting that there is substantial variability between studies in how covariates are mea- sured (e.g. blood pressure: clinical cut-offs, categorical or continuous measure and SES: Income or composite poverty index) and the impact of this on any observed relationship is unknown. Meta-analyses [4,5] have re- ported that depression satisfying DSM- or ICD-diagnos- tic criteria has a stronger association with CHD than symptom based measures. We also found evidence of such a stronger association but suggest that this does not automatically imply a causal relationship. Given reports that a shared variance between negative emotions shows a stronger association with CHD than depression alone [49] there is reason to doubt the causal role attributed solely to depression since most studies have failed to control for possible confounding psychological and psy- chiatric variables. Only 6% of studies gave consideration to changes in depression during follow up (variation in severity and duration) and only 2% gave consideration to changes in other risk factors. Apart from the mention of antidepres- sant use at baseline in 10% of studies, there is no men- tion of treatment at baseline or during follow up in 93% of the studies. Seemingly there was insufficient concern about the severity of baseline depression in these studies to refer anyone for treatment—if there was, one would expect mention of it. This wou ld suggest relativ ely min o r depression in by far the majority of subjects and without further information of worsening depression during fol- low-up it might be difficult to explain a causal relation- ship between “depression not requiring treatment” and CHD on physiological grounds. The lack of information about changes in depression during follow up would also question the validity of any conclusions about “dose- effect” in the suggested relationship. This review cannot exclude th e possibility that depres- sion does play a causal role in the development of CHD. It does, however, highlight the fact that there are good reasons for questioning the validity of the supporting evi- dence. Many of these reasons (inadequate covariate con- trol, reverse causality) may not be adequately addressed with prospective cohort designs because the studies re- quired (very large sample sizes, very long duration of follow-up, intense contact during follow up, extensive baseline testing etc.) may seem daunting. However, the question is important and deserves more systematic in- vestigation. More aggressive treatment of depression/ depressive symptoms may be warranted if a causal role is established. The conclusion in this review of the evi- dence is that it remains to be shown that depression is a causal risk factor for CHD. REFERENCES [1] Kuper, H., Nicholson, A. and He mingway H. (2006) Sea r- ching for observational studies: What does citation track- ing add to PubMed? A case study in depression and coronary heart disease. BMC Medical Research Method- ology, 6, 4. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-6-4 [2] Frasure-Smith, N. and Lesperance, F. (2006) Recent evi- dence linking coronary heart disease and depression. Ca- nadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 730-737. [3] Van der Koy, K., van Hout, H., Marwijk, H., Marten, H., Stehouwer, C. and Beekman, A. (2007) Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review and meta analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psy- chiatry, 22, 613-626. doi:10.1002/gps.1723 [4] Rugulies, R. (2002) Depression as a predictor for coro- nary heart disease. A review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 23, 51-61. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00439-7 [5] Nicholson, A., Kuper, H. and Hemingway, H. (2006) De- pression as an aetiologic and prognostic factor in coro- nary heart disease: A meta-analysis of 6362 events among 146,538 participants in 54 observational studies. Euro- pean Heart Journal, 27, 2763-2774. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehl338 [6] Khan, F.M., Kulaksizoglu, B. and Cilingiroglu, M. (2010) Depression and coronary heart disease. Current Athero- sclerosis Reports, 12, 105-109. doi:10.1007/s11883-010-0096-5 [7] Kuper, H., et al. (2009) Evaluating the causal relevance of diverse risk markers: Horizontal systematic review. BMJ, 339, b4265. doi:10.1136/bmj.b4265 [8] Wulsin, L.R. (2004) Is depression a major risk factor for coronary disease? A systematic review of the epidemi- ologic evidence. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12, 79- 93. doi:10.1080/10673220490447191 [9] Smith, D.F. (2001) Negative emotions and coronary heart disease: Causally related or merely coexiste nt? A review. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 42, 57-69. doi:10.1111/ 1467-9450.00214 [10] Bunker, S.J., et al. (2003) “Stress” and coronary heart disease: Psychosocial risk factors. Medical Journal of Australia, 178, 272-276. [11] Cohen, H.W., Gibson, G. and Alderman, M.H. (2000) Excess risk of myocardial infarction in patients treated with antidepressant medications: Association with use of tricyclic agents. American Journal of Medicine, 108, 2-8. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00301-0 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 289 [12] Kawamura, T.L., Shioiri, T., Takahashi, K., Ozdemir, V. and Someya, T. (2007) Survival rate and causes of mor- tality in the elderly with depression: A 15-year prospec- tive study of a Japanese community sample, the Matsu- noyama—Niigata Suicide Prevention Project. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 55, 106-114. doi:10.2310/6650.2007.06040 [13] Mausbach, B.T., Patterson, T.L., Rabinowitz, Y.G. and Grant, I. (2007) Depression and distress predict time to cardiovascular disease in dementia caregivers. Health Psychology, 26, 539-544. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.539 [14] Schwartz, S.W., Cornoni-Huntley, J., Cole, S.R., Hays, J.C., Blazer, D.G. and Schocken, D.D. (1998) Are sleep complaints an independent risk factor for myocardial in- farction? Annals of Epidemiology, 8, 384-392. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(97)00238-X [15] Davidson, K.W. and Mostofsky, E. (2010) Anger expres- sion and risk of coronary heart disease: Evidence from the Nova Scotia Health Survey. American Heart Journal, 159, 199-206. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.007 [16] Shen, B.-J., et al. (2008) Anxiety characteristics indepen- dently and prospectively predict myocardial infarction in men the unique contribution of anxiety among psycholo- gic factors. Journal of the American College of Cardiol- ogy, 51, 113-119. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.033 [17] Cole, S.R., Kawachi, I., Sesso, H.D., Paffenbarger, R.S. and Lee, I.M. (1999) Sense of exhaustion and coronary heart disease among college alumni. American Journal of Cardiology, 84, 1401-1405. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(99)00585-8 [18] Mallon, L., Broman, J.E. and Hetta, J. (2002) Sleep com- plaints predict coronary artery disease mortality in males: A 12-year follow-up study of a middle-aged Swedish population. Journal of Internal Medicine, 251, 207-216. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.00941.x [19] Clouse, R.E.M., Lustman, P.J.P., Freedland, K.E.P., Grif- fith, L.S.M., McGill, J.B.M. and Carney, R.M.P. (2003) Depression and coronary heart disease in women with diabetes. Psychosoma tic M edicine, 65, 376-383. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000041624.96580.1F [20] Wassertheil-Smoller, S., et al. (2004) Depression and car- diovascular sequelae in postmenopausal women—The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). Archives of Internal Medicine, 164, 289-298. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.3.289 [21] Kendler, K.S., Gardner, C.O., Fiske, A. and Gatz, M. (2009) Major depression and coronary artery disease in the Swedish twin registry: Phenotypic, genetic, and envi- ronmental sources of comorbidity. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 857-863. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.94 [22] Whang, W., et al. (2009) Depression and risk of sudden cardiac death and coronary heart disease in women: Re- sults from the nurses’ health study. Journal of the Ame- rican College of Cardiology, 53, 950-958. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.060 [23] Hallstrom, T., Lapidus, L., Bengtsson, C. and Edstrom, K. (1986) Psychosocial factors and risk of ischaemic heart disease and death in women: A twelve-year follow-up of participants in the population study of women in Goth- enburg, Sweden. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 30, 451-459. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(86)90084-X [24] Orchard, T.J., et al. (2003) Insulin resistance-related fac- tors, but not glycemia, predict coronary artery disease in type 1 diabetes—10-year follow-up data from the Pitts- burgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complications study. Diabetes Care, 26, 1374-1379. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.5.1374 [25] Penninx, B.W.J.H., et al. (1998) Cardiovascular events and mortality in newly and chronically depressed persons >70 years of age. American Journal of Cardiology, 81, 988- 994. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00077-0 [26] Lloyd, C.E., Kuller, L.H., Ellis, D., Becker, D.J., Wing, R.R. and Orchard, T.J. (1996) Coronary artery disease in IDDM—Gender differences in risk factors but not risk. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 16, 720-726. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.16.6.720 [27] Sykes, D.H., et al. (2002) Psychosocial risk factors for heart disease in France and Northern Ireland: The Pro- spective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction (PRIME). International Journal of Epidemiology, 31, 1227- 1234. doi:10.1093/ije/31.6.1227 [28] Gromova, H.A., Gafarov, V.V. and Gagulin, I.V. (2007) Depression and risk of cardiovascular diseases among males aged 25 - 64 (WHO MONICA—Psychosocial). Alaska Medicine, 49, 255-258. [29] Davidson, K.W., et al. (2009) Relation of inflammation to depression and incident coronary heart disease (from the Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey [NSHS95] Pro- spective Population Study). American Journal of Cardi- ology, 103, 755-761. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.11.035 [30] Kubzansky, L.D., Cole, S.R., Kawachi, I., Vokonas, P. and Sparrow, D. (2006) Shared and unique contributions of anger, anxiety, and depression to coronary heart dis- ease: A prospective study in the normative aging study. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 21-29. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm3101_5 [31] Klabbers, G., Bosma, H. , Van Lent he, F.J., Kempen, G. I., Van Eijk, J.T. and Mackenbach, J.P. (2009) The relative contributions of hostility and depressive symptoms to the income gradient in hospital-based incidence of ischaemic heart disease: 12-year follow-up f indings f rom the GLOBE study. Social Science & Medicine, 69, 1272-1280. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.031 [32] Surtees, P.G., Wainwright, N.W., Luben, R.N., Wareham, N.J., Bingham, S.A. and Khaw, K.T. (2008) Depression and ischemic heart disease mortality: Evidence from the EPIC-Norfolk United Kingdom prospective cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 515-523. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07061018 [33] Thurston, R.C., Kubzansky, L.D., Kawachi, I. and Berk- man, L.F. (2006) Do depression and anxiety mediate the link between educational attainment and CHD? Psycho- somatic M edicine, 68, 25-32. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000195883.68888.68 [34] Marzari, C., et al. (2005) Depressive symptoms and de- velopment of coronary heart disease events: The Italian longitudinal study on aging. The Journals of Gerontology Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 290 Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 60, 85-92. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.1.85 [35] Rowan, P.J., Haas, D., Campbell, J.A., MaClean, D.R. and Davidson, K.W. (2005) Depressive symptoms have an independent, gradient risk for coronary heart disease incidence in a random, population-based sample. Annals of Epidemiology, 15, 316-320. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.08.006 [36] Ahto, M., Isoaho, R., Puolijoki, H., Vahlberg, T. and Kivela, S.L. (2007) Stronger symptoms of depression predict high coronary heart disease mortality in older men and women. International Journal of Geriatric Psychia- try, 22, 757-763. doi:10.1002/gps.1735 [37] Bremmer, M.A., Hoogendijk, W.J.G., Deeg, D.J.H., Scho- evers, R.A., Schalk, B.W.M. and Beekman, A.T.F. (2006) Depression in older age is a risk factor for first ischemic cardiac events. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 523-530. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000216172.31735.d5 [38] Ford, D.E., Mead, L.A., Chang, P.P., Cooper-Patrick, L., Wang, N.Y. and Klag, M.J. (1998) Depression is a risk factor for coronary crtery disease in men: The precursors study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1422-1426. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.13.1422 [39] Pratt, L.A., Ford, D.E., Crum, R.M., Armenian, H.K., Gallo, J.J. and Eaton, W.W. (1996) Depression, psycho- tropic medication and risk of myocardial infarction: Pro- spective data from the Baltimore ECA follow-up. Circu- lation, 94, 3123-3129. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.94.12.3123 [40] Ariyo, A.A., et al. (2000) Depressive symptoms and risks of coronary heart disease and mortality in elderly Ameri- cans. Circulation, 102, 1773-1779. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.102.15.1773 [41] Barefoot, J.C. and Schroll, M. (1996) Symptoms of de- pression, acute myocardial infarction and total mortality in a community sampl e. Circulation, 93, 1976-1980. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.93.11.1976 [42] Penninx, B.W.J.H., et al. (2001) Depression and cardiac mortality: Results from a community-based longitudinal study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58, 221-227. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.221 [43] Sesso, H.D., Kawachi, I., Vokonas, P.S. and Sparrow, D. (1998) Depression and the risk of coronary heart disease in the normative aging study. American Journal of Car- diology, 82, 851-856. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00491-3 [44] Joukamaa, M., Heliovarra, M., Knekt, P., Aromaa, A., Raitasalo, R. and Lehtinen, V. (2001) Mental disorders and cause-specific mortality. The British Journal of Psy- chiatry, 179, 498-502. doi:10.1192/bjp.179.6.498 [45] Ferketich, A.K., Schwartzbaum, J.A., Frid, D.J. and Moes- chberger, M.L. (2000) Depression as an antecedent to heart disease among women and men in the NHANES I study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 160, 1261-1268. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.9.1261 [46] Cohen, H.W.D, Madhavan, S.D. and Alderman, M.H.M. (2001) History of treatment for depression: Risk factor for myocardial infarction in hypertensive patients. Psy- chosomatic Medicine, 63, 203-209. doi:10.1097/00001648-199307000-00003 [47] Anda, R., et al. (1993) Depressed affect, hopelessness and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of US adults. Epidemiology, 4, 285-294. [48] Appels, A., Kop, W.J. and Schouten, E. (2000) The na- ture of depressive symptomatology preceeding myocar- dial infarction. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 86- 89. doi:10.1080/08964280009595756 [49] Boyle, S.H., Michalek, J.E. and Suarez, E.C. (2006) Co- variation of psychological attributes and incident coro- nary heart disease in US. Air force veterans of the Viet- nam war. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 844-850. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000240779.55022.ff [50] Chang, M.H., Hahn, R.A., Teutsch, S.M. and Hutwagner, L.C. (2001) Multiple risk factors and population attribut- able risk for ischemic heart disease mortality in the United States, 1971-1992. Journal of Clinical Epidemi- ology, 54, 634-644. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00343-7 [51] Gump, B.B., Matthews, K.A., Eberly, L.E. and Chang, Y.F. (2005) Depressive symptoms and mortality in men results from the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Stroke, 36, 98-102. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000149626.50127.d0 [52] Haines, A., Cooper, J. and Meade, T.W. (2001) Psycho- logical characteristics and fatal ischaemic heart disease. Heart, 85, 385-389. doi:10.1136/heart.85.4.385 [53] Kamphuis, M.H., et al. (2006) Depressive symptoms as risk factor of cardiovascular mortality in older European men: The Finland, Italy and Netherlands Elderly (FINE) study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, 13, 199-206. doi:10.1097/01.hjr.0000188242.64590.92 [54] Luukinen, H., Laippala, P. and Huikuri, H.V. (2003) De- pressive symptoms and the risk of sudden cardiac death among the elderly. European Heart Journal, 24, 2021- 2026. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2003.09.003 [55] Mendes de Leon, C.F., et al. (1998) Depression and risk of coronary heart disease in elderly men and women: New Haven EPESE, 1982-1991. Archives of Internal Me- dicine, 158, 2341-2348. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.21.2341 [56] Nicholson, A., Fuhrer, R. and Marmot, M. (2005) Psy- chological distress as a predictor of CHD events in men: The effect of persistence and components of risk. Psy- chosomatic Medicine, 67, 522-530. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000171159.86446.9e [57] Sturmer, T., Hasselbach, P. and Amelang, M. (2006) Per- sonality, lifestyle, and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer: Follow-up of population based cohort. BMJ, 332, 1359. doi:10.1136/bmj.38833.479560.80 [58] Todaro, J.F., Shen, B.J., Niaura, R., Spiro, A. and Ward, K.D. (2003) Effect of negative emotions on frequency of coronary heart disease (The Normative Aging Study). American Journal of Cardiology, 92, 901-906. doi:10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00967-6 [59] Wassertheil-Smoller, S., et al. (1996) Change in depres- sion as a precursor of cardiovascular events. SHEP Co- operative Research Group (Systolic Hypertension in the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  H. G. Stampfer et al. / Open Journal of Psychiatry 2 (2012) 284-291 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 291 OPEN ACCESS elderly). Archives of Internal Medicine, 156, 553-561. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.5.553 [60] Whooley, M.A.M. and Browner, W.S.M.M. (1998) As- sociation between depressive symptoms and mortality in older women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 2129- 2135. doi:10.1001/archinte.158.19.2129 [61] Wulsin, L.R., Evans, J.C., Vasan, R.S., Murabito, J.M., Kelly-Hayes, M. and Benjamin, E.J. (2005) Depressive symptoms, coronary heart disease, and overall mortality in the Framingham Heart Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67, 697-702. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000181274.56785.28 [62] Sartorius, N., Ustun, T.B., Lecrubier, Y., Wittchen, H.U. (1996) Depression comorbid with anxiety: Results from the WHO study on psychological disorders in primary health care. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 38-43.

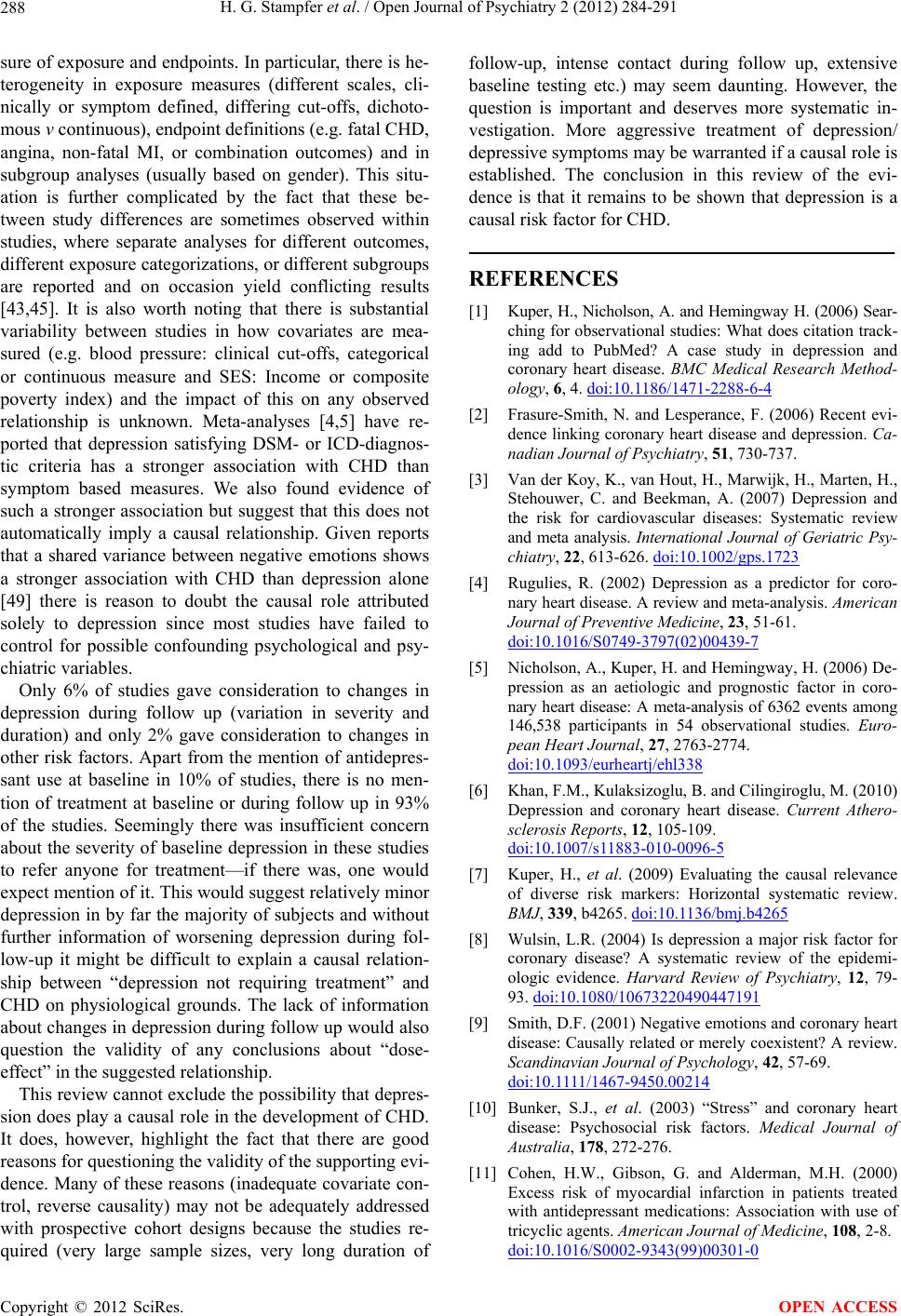

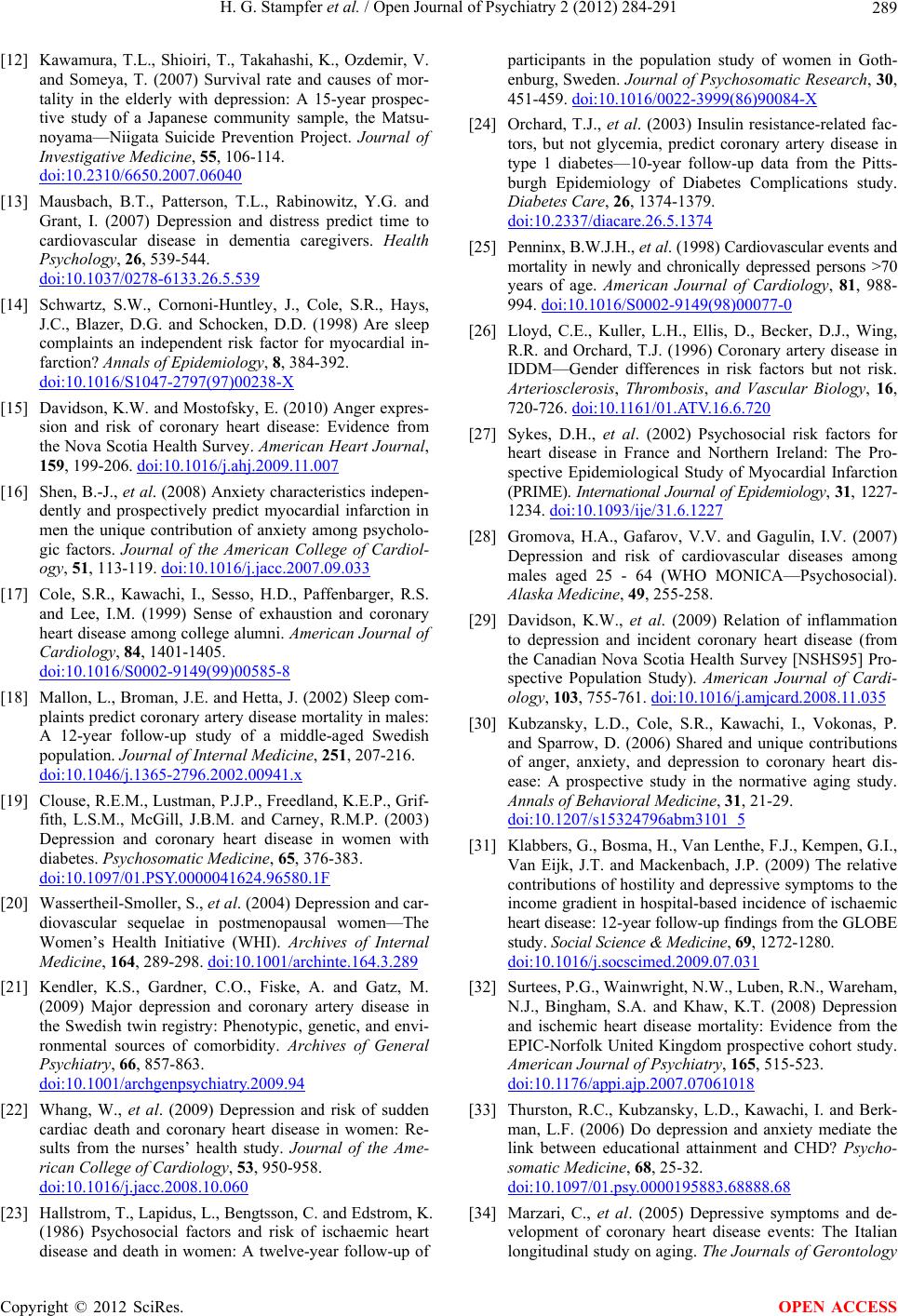

|