V. CHIRILA, C. CHIRILA

716

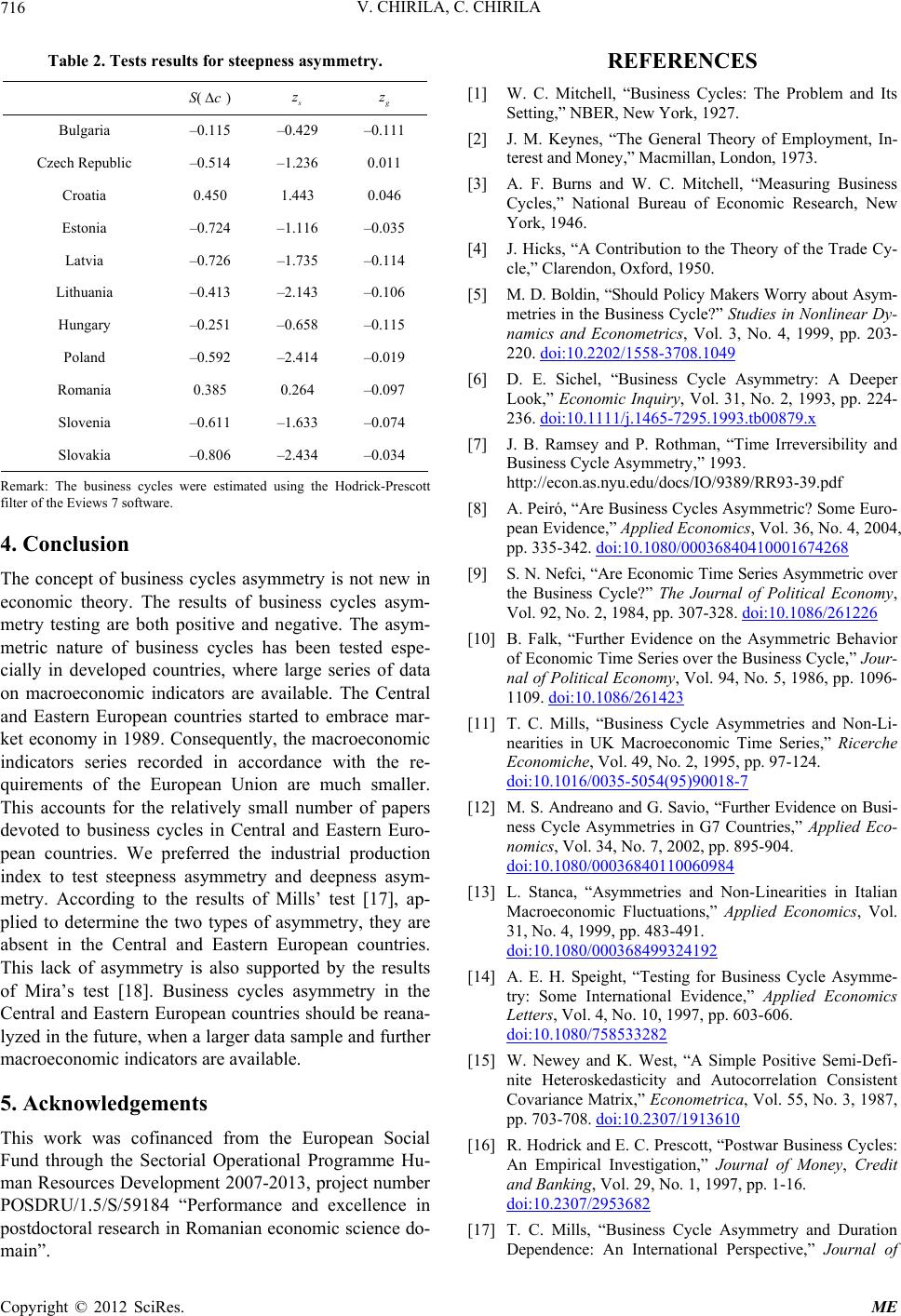

Table 2. Tests results for steepness asymmetry.

S() c

z

z

Bulgaria –0.115 –0.429 –0.111

Czech Republic –0.514 –1.236 0.011

Croatia 0.450 1.443 0.046

Estonia –0.724 –1.116 –0.035

Latvia –0.726 –1.735 –0.114

Lithuania –0.413 –2.143 –0.106

Hungary –0.251 –0.658 –0.115

Poland –0.592 –2.414 –0.019

Romania 0.385 0.264 –0.097

Slovenia –0.611 –1.633 –0.074

Slovakia –0.806 –2.434 –0.034

Remark: The business cycles were estimated using the Hodrick-Prescott

filter of the Eviews 7 software.

4. Conclusion

The concept of business cycles asymmetry is not new in

economic theory. The results of business cycles asym-

metry testing are both positive and negative. The asym-

metric nature of business cycles has been tested espe-

cially in developed countries, where large series of data

on macroeconomic indicators are available. The Central

and Eastern European countries started to embrace mar-

ket economy in 1989. Consequently, the macroeconomic

indicators series recorded in accordance with the re-

quirements of the European Union are much smaller.

This accounts for the relatively small number of papers

devoted to business cycles in Central and Eastern Euro-

pean countries. We preferred the industrial production

index to test steepness asymmetry and deepness asym-

metry. According to the results of Mills’ test [17], ap-

plied to determine the two types of asymmetry, they are

absent in the Central and Eastern European countries.

This lack of asymmetry is also supported by the results

of Mira’s test [18]. Business cycles asymmetry in the

Central and Eastern European countries should be reana-

lyzed in the future, when a larger data sample and further

macroeconomic indicators are available.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was cofinanced from the European Social

Fund through the Sectorial Operational Programme Hu-

man Resources Development 2007-2013, project number

POSDRU/1.5/S/59184 “Performance and excellence in

postdoctoral research in Romanian economic science do-

main”.

REFERENCES

[1] W. C. Mitchell, “Business Cycles: The Problem and Its

Setting,” NBER, New York, 1927.

[2] J. M. Keynes, “The General Theory of Employment, In-

terest and Money,” Macmillan, London, 1973.

[3] A. F. Burns and W. C. Mitchell, “Measuring Business

Cycles,” National Bureau of Economic Research, New

York, 1946.

[4] J. Hicks, “A Contribution to the Theory of the Trade Cy-

cle,” Clarendon, Oxford, 1950.

[5] M. D. Boldin, “Should Policy Makers Worry about Asym-

metries in the Business Cycle?” Studies in Nonlinear Dy-

namics and Econometrics, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1999, pp. 203-

220. doi:10.2202/1558-3708.1049

[6] D. E. Sichel, “Business Cycle Asymmetry: A Deeper

Look,” Economic Inquiry, Vol. 31, No. 2, 1993, pp. 224-

236. doi:10.1111/j.1465-7295.1993.tb00879.x

[7] J. B. Ramsey and P. Rothman, “Time Irreversibility and

Business Cycle Asymmetry,” 1993.

http://econ.as.nyu.edu/docs/IO/9389/RR93-39.pdf

[8] A. Peiró, “Are Business Cycles Asymmetric? Some Euro-

pean Evidence,” Applied Economics, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2004,

pp. 335-342. doi:10.1080/00036840410001674268

[9] S. N. Nefci, “Are Economic Time Series Asymmetric over

the Business Cycle?” The Journal of Political Economy,

Vol. 92, No. 2, 1984, pp. 307-328. doi:10.1086/261226

[10] B. Falk, “Further Evidence on the Asymmetric Behavior

of Economic Time Series over the Business Cycle,” Jour-

nal of Political Economy, Vol. 94, No. 5, 1986, pp. 1096-

1109. doi:10.1086/261423

[11] T. C. Mills, “Business Cycle Asymmetries and Non-Li-

nearities in UK Macroeconomic Time Series,” Ricerche

Economiche, Vol. 49, No. 2, 1995, pp. 97-124.

doi:10.1016/0035-5054(95)90018-7

[12] M. S. Andreano and G. Savio, “Further Evidence on Busi-

ness Cycle Asymmetries in G7 Countries,” Applied Eco-

nomics, Vol. 34, No. 7, 2002, pp. 895-904.

doi:10.1080/00036840110060984

[13] L. Stanca, “Asymmetries and Non-Linearities in Italian

Macroeconomic Fluctuations,” Applied Economics, Vol.

31, No. 4, 1999, pp. 483-491.

doi:10.1080/000368499324192

[14] A. E. H. Speight, “Testing for Business Cycle Asymme-

try: Some International Evidence,” Applied Economics

Letters, Vol. 4, No. 10, 1997, pp. 603-606.

doi:10.1080/758533282

[15] W. Newey and K. West, “A Simple Positive Semi-Defi-

nite Heteroskedasticity and Autocorrelation Consistent

Covariance Matrix,” Econometrica, Vol. 55, No. 3, 1987,

pp. 703-708. doi:10.2307/1913610

[16] R. Hodrick and E. C. Prescott, “Postwar Business Cycles:

An Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Money, Credit

and Banking, Vol. 29, No. 1, 1997, pp. 1-16.

doi:10.2307/2953682

[17] T. C. Mills, “Business Cycle Asymmetry and Duration

Dependence: An International Perspective,” Journal of

Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ME