Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

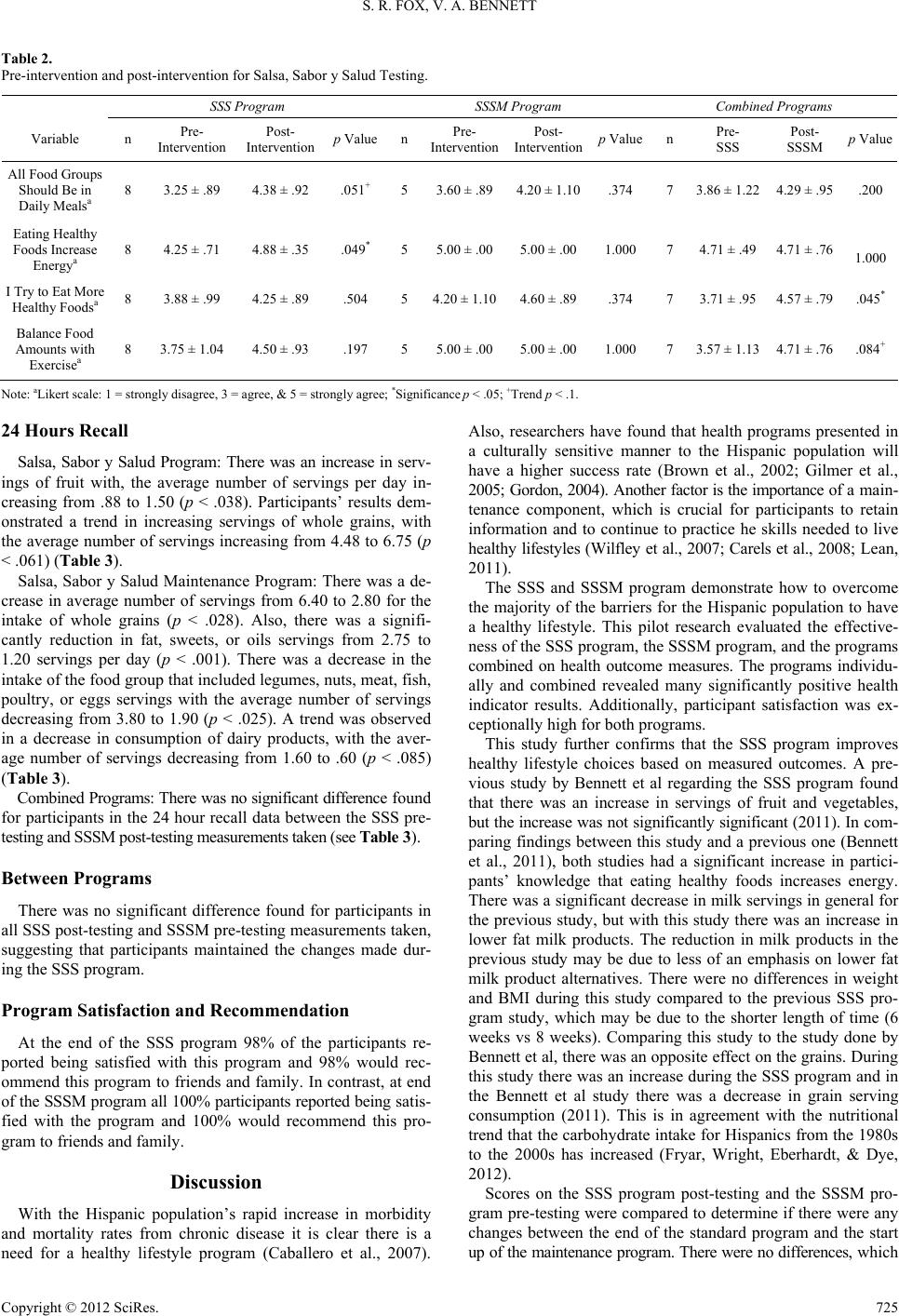

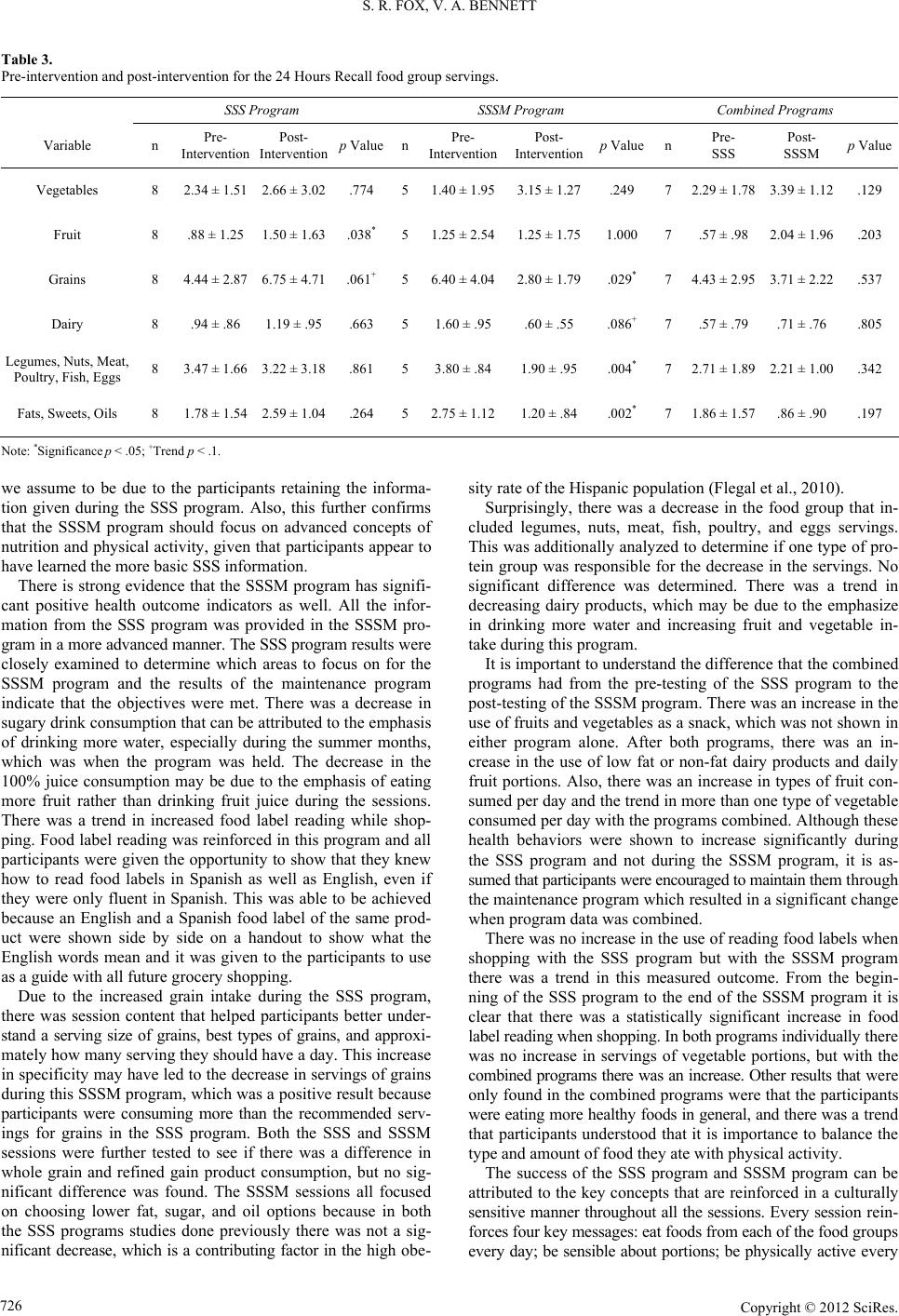

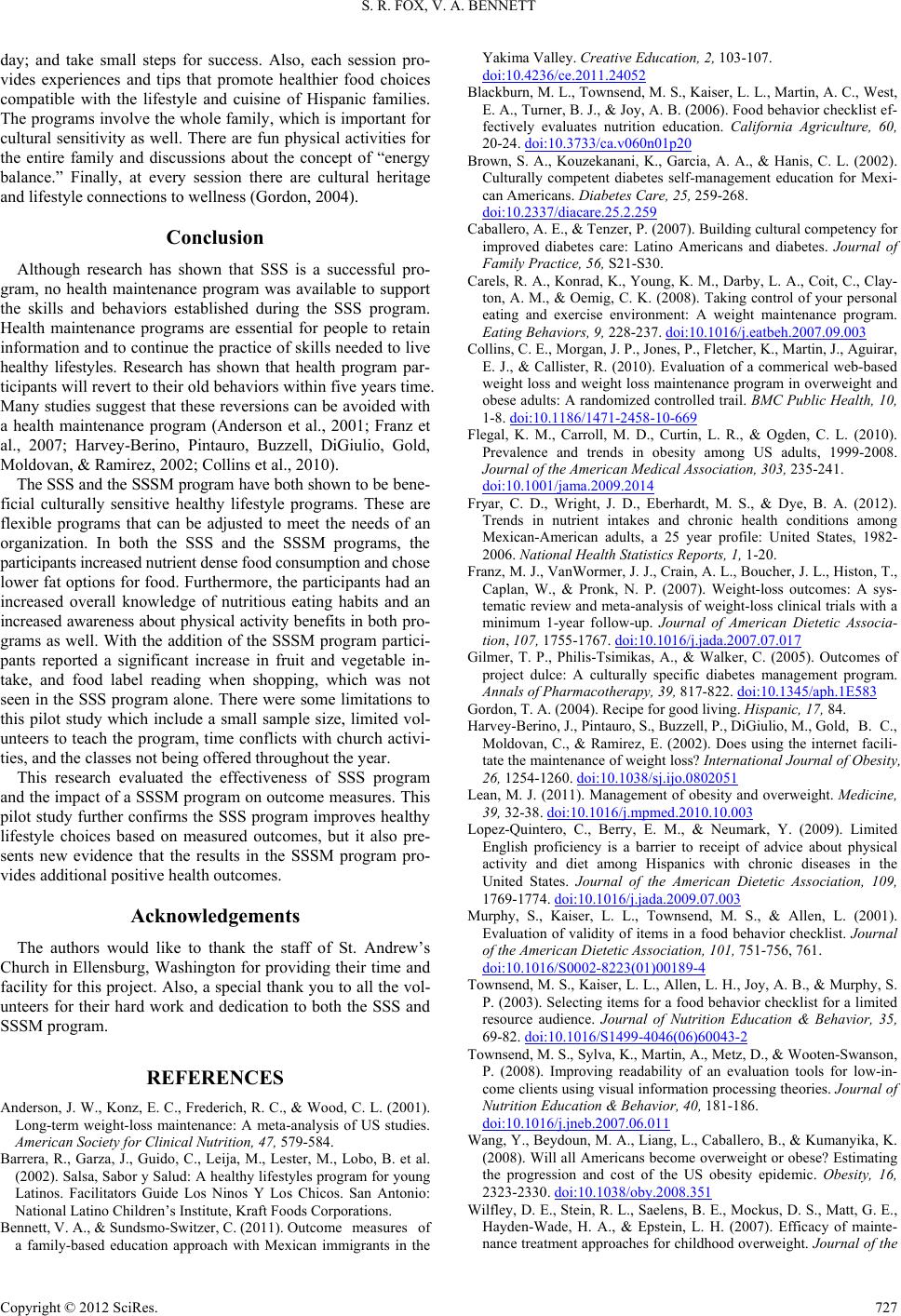

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.6, 721-728 Published Online October 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.36107 Copyright © 2012 SciR e s . 721 Effectiveness of Salsa, Sabor y Salud Program and the Impact of a Salsa, Sabor y Salud Maintenance Program on Outcome Measures Stephanie R. Fox, Virginia A. Bennett Central Washington University, Ellensburg, USA Email: foxnutrition@hotmail.com Received August 2nd, 2012; r evised September 5th, 2012; accepted September 20th, 2012 Chronic diseases in the United States are disproportionately higher in the Hispanic population. A signifi- cant factor in the high prevalence of chronic disease in Hispanics may be their overweight or obese status. Intervention strategies are imperative if this trend is to be reversed. Researchers have found that culturally sensitive health programs for the Hispanic population have a higher success rate, but very few of these programs are available. One culturally sensitive health program in particular that has had a lot of positive feedback is the Salsa, Sabor y Salud (SSS) program. Although research has shown that SSS is a success- ful program, SSS has not had a maintenance program to date. Health maintenance programs are essential for people to retain information and to continue the practice of skills needed to live healthy lifestyles. Re- search has shown that health program participants will revert to their old behaviors within five years time. Recent studies suggest that these reversions can be avoided with a health maintenance program. The ob- jective of this pilot study was to evaluate the effectiveness of the SSS program and the impact of a Salsa, Sabor y Salud Maintenance (SSSM) program on outcome measures. In both the SSS and SSSM program the participants increased nutrient dense food consumption and chose lower fat options for food. The par- ticipants in both programs had a significant increase in overall knowledge of nutritious eating habits and the benefits of physical activity as well. With the addition of the SSSM program participants reported an increase in fruit and vegetable intake, and food label reading when shopping, which was not seen in the SSS program alone. This study further confirms the SSS program improves healthy lifestyle choices based on measured outcomes, but it also provides evidence that the SSSM program significantly enhances positive health outcomes. Keywords: Cultural Competency; Salsa Sabor y Salud; Maintenance Program Introduction In the past few decades there has been a major increase in the number of overweight and obese i ndividuals in the United St at es (USA) (Wang, Beydoun, Liang, Caballero, & Kumany ika, 2008). According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Ex- amination Survey (NHANES) in 2007-2008 the prevalence of overweight and obese adults was 68% and 33.8% respectively. Within the Hispanic population in the USA 77.9% were over- weight and 38.7% were obese (Flegal, Carroll, Curtin, & Ogden, 2010). Childhood obesity is also a growing problem in the USA. In 2008, 34% children and adolescents of all ethnic groups were considered overweight with a body mass index (BMI) above the 85th percentile and 17% were obese with a BMI above the 95th percentile (Centrella-Nigro, 2009). BMI is an estimation of body fat based on the calculation using the height and weight of a person (Bennett & Sundsmo-Switzer, 2011). There is an increased risk for Hispanic children and adolescents to become overweight or obese (Centrella-Nigro, 2009). The NHANES 2008 survey revealed that 38.2% of Hispanic children and adoles- cents were overweight and 20.9% were considered obese. This is a profound concern because the majority of overweight and obese chi ldren and a dolescen ts will co ntinue to m aintain t h is status later in life, which can lead to life-threatening chronic diseases (Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010). Chronic disea ses in the USA occur at disproportiona tely hi gh er rates in the Hispanic population (Lopez-Quintero, Berry, & Neu- mark, 2009). There are numerous Hispanic immigrants who c om e to the USA with healthy diets and levels of high physical activ- ity, but there is evidence that through acculturation there is a negative impact on their nutrition and exercise (Ayala, Baquero, & Klinger, 2008). Health care providers have had difficulty conveying the importance of nutrition and physical activity to the Hispanic population (Lopez-Quintero et al., 2009). Researchers have found that if the health information is presented to His- panic participants in a culturally sensitive manner they will have a higher success rate in their health programs, such as diabetes education programs (Brown, Kouzekanani, Garcia, & Hanis, 2002; Gilmer, Philis-Tsimikas, & Walker, 2005; Gordon, 2004). For the current pilot intervention, in Ellensburg WA, US A, was selected because there are currently no culturally specific healthy lifestyle classes offered to this population and 53% of Hispanics in Kittitas County are at or below 184% of the fed- eral poverty level, making them at risk for poor he alth outcome s (Wilkerson, 2008). With the high rate of Hispanic overweight or obesity, it is clear that there is a need for an effective and culturally appro- priate healthy lifestyle program. One program in particular that has had a lot of positive feedback is the culturally sensitive Hispanic healthy lifestyle program called Salsa, Sabor y Salud (SSS) that was created by National Latino Children’s Institute (Ayala et al., 2008). There has been one study that measured  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT objective outcomes of this program and found statistically sig- nificant positive health indicators upon completion, which in- cluded dietary changes, weight, body mass index, waist circum- ference, blood pressure, heart rate, reported physical activity, and healthy lifestyle scores (Bennett et al., 2011). Health main- tenance programs are essential for people to retain information and to continue the practice of skills needed to live healthy lifestyles (Wilfley et al., 2007; Carels et al., 2008; Lean, 2011). Many studies suggest that participants will revert back to their old behaviors within five years time, but it can be avoided with a health maintenance program ((Anderson et al., 2001; Franz et al., 2007; Harvey-Berino, Pintauro, Buzzell, DiGiulio, Gold, Moldovan, & Ramirez, 2002; Collins et al., 2010). To date, th er e has not been a maintenance component available for the Salsa, Sabor y Salud program. The purpose of this pilot research was to determine the effec- tiveness of the SSS program and the impact of a Salsa, Sabor y Salud Maintenance (SSSM) progra m on outcome mea sure s. Participants and Methods Participants The SSS healthy lifestyles program was offered to Hispanic families living in Kittitas County during the winter of 2011, fol- lowed by the SSSM program that was offere d in the of summer 2011. Participation in the winter program was open to Hispan- ics living in the immediate area. Participants were eligible to join the SSSM if they had participate d in the SSS program held in the winter of 2011 and attended 3 or more sessions. Demo- graphics were assessed using the Washington State University Demographics Questionnaire (Blackburn, Townsend, Kaiser, Martin, West, Turner, & Joy, 2006), which helped determine if the participants were of Hispanic ethnicity and the race they considered themselves to be. It qualified age as 18 - 59 or 60 plus. They were also asked if they were receiving government assistance. This question helped identify the socioeconomic status of the participants in the study. The SSS and SSSM programs seek to improve the health of the whole family due to the close family relationships in the Hispanic culture, but for this study, only data was collected for the adults. The programs were held at a catholic church imme- diately after the Spanish mass. This study was open to either sex and the only exclusions to pa rticipation were obvious ph ysi - cal or mental limitations that impaired the subject to participate in the physical or mental aspects of the program. This study was conducted in Ellensburg because, based on our research of the surrounding area, there were currently no culturally specific healthy lifestyle classes offered to this population. Recruitment for the SSS and SSSM program were done with radio announcements, announcements made at the church, and flyers about the program one month prior to the classes starting. Those who were interested were enrolled. When recruiting for the SSSM program participants in the winter SSS program were notified and announcements were made at the church. There were a total of 17 participants enrolled for the winter SSS program. From this SSS program, 15 participants were enrolled in the summer SSSM program. Participants who had missing data or didn’t meet the attendance standards (three or more sessions during the winter SSS program and two or more sessions during the summer SSSM program) were not included in the study. Study Desi gn This study was approved by the Central Washington Univer- sity Human Subjects Review Committee. Participants were gi ven materials in either Spanish or English based on their preference. A written consent and explanation of the study was given to all adult participants. If an adult did not want to be part of the re- search study, they were still able to participate in the SSS and SSSM programs. This was a quasi experimental design, in which the partici- pant volunteered to be a part of the study. The same pre- and post-testing was used for both the SSS and SSSM program. Pre- and post-testing was used to assess changes in nutrition and ph y s i - cal activity knowledge, and dietary habits. All participants who were included in the data analysis pilot study had to complete both the pre- and post-measurements. The SSS program is a culturally sensitive program that was created for educating Hispanic families on how to make healthy lifestyle choices. It was designed to include eight sessions at 90 minutes, but is a flexible program that can be adjusted to meet the needs of the organization that is coordinating it. There are different themes for each session that are intended to educate regarding the importance of nutrition and physical activity. A novel maintenance program designed to complement the SSS program was developed for this pilot study. The curricu- lum was set up similarly to the actual SSS program. It included four 90 minute sessions and can be changed to fit the needs of any organization. It consists of four new sessions with cultur- ally sensitive themes that educates the families on nutrition and physical activity, but all the lessons are more advanced versions of the previous learning objectives in the SSS program. Procedure CWU undergraduate nutrition students taught the sessions in Spanish. The CWU undergraduate nutrition stude nts chosen were bilingual, bicultural, and trained by the national SSS program trainers. At least one registered dietitian and one graduate nutri- tion student from CWU attended every session for both the SSS and SSSM programs to help with any questions related to nutri- tion and physical activity. All pre- and post-measurements were administered and described by the CWU undergraduate nutri- tion students, a registered dietitian, and/or a graduate nutrition student from CWU. Participants were assigned a numerical identifier when they filled out all pre- and post-forms. A list of participants with matching coded identifier was kept in a secure cabinet apart from the data and used only by the principal investigators. Par- ticipants were given their ID numbers as part of their docu- mentation and asked to use them in subsequent data collection. In this manner, no names were linked to data. The list with names linking coded identifiers was destroyed upon completion of data collection. Both photographs and videos were taken of classroom activi- ties, but limited to those participants who agreed to being pho- tographed or video recorded on a signed consent form. While these photos could identify the participants, personal data was not connected to the photos. The photographs and/or video were archived for future use in an annual presentation to dietitians describing the educational program and its benefits as well as part of the graduate student’s oral defense. These photos are stored in the principal investigator’s locked office inside a locked file Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 722  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT cabinet, with all data collect coded with numbers instead of par- ticipants names. Due to time constraints, the winter SSS program was modi- fied as to the number of sessions and the amount of time pre- sented. As mentioned before, the curriculum was designed for eight sessions at 90 minutes, but adjustments can be made to the program to adhere to the group’s time frames. Six weekly sessions for the SSS program were offered in the winter con- sisting of 120 minutes each. For the first 75 minutes there were lectures and activities. In the remaining 45 minutes there was SSS physical activities and review of the session. At the first session there was a debriefing about the program and the study. During this time written consents were explained. The pre-mea- surements were taken in session one during the first 30 minutes and in session 6 the post-measurements were taken the last 30 minutes. For each session the learning objectives were clearly defined and reinforced throughout the six week program. At the last session there was a review of the whole program and par- ticipants were able to sign up for the SSSM program. For the SSSM program there were four weekly sessions that were 120 minutes each. The SSSM had the same structure as t he six week SSS winter program, but included different themed activities. For the first 75 minutes there were lecture and activi- ties. In the remaining 45 minutes there were SSS physical ac- tivities and review of the session. At the first session there was a debriefing about the program and the study. The pre-measu- rements were taken in session one during the first 30 minutes and in session four the post-measurements were taken the last 30 minutes. For each session the learning objectives were c le a rly defined and reinforced throughout the four week program. At the last session there was a review of the whole program and participants were given a SSSM program tips packet to help them maintain their nutrition and physical activity knowledge after the program completion. Measurements Pre- and post-testing was used to assess healthy lifestyle cha- nges in nutrition and phy sical activity knowledge with two s hort questionnaires. One of the questionnaires, Salsa, Sabor y Salud Healthy Lifestyle Test, obtained from the National Latino Chil- dren’s Institute (Bennett et al., 2011; Barrera et al., 2002), was used to assess knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes surrounding nu- trition and physical activity. The other questionnaire, Washing- ton State University (WSU) Food Behavior Checklist (Black- burn et al., 2006; Murphy, Kaiser, Townsend, & Allen, 2001; Townsend, Kaiser, Allen, Joy, & Murphy , 2003; Townsend, Sy l - va, Martin, Metz, & Wooten-Swanson, 2008), is a multiple choice questionnaire assessing food group preference, food frequency, food label knowledge, food security, and physical activity. As done in the previous SSS study by Bennett et al., dietary habits were also recorded at pre- and post-interventions, and assessed with a 24-hour diet recall form (2011). The 24-hour diet recall form included all foods and beve rages consumed du r- ing the 24 hours proceeding the day of the interview from mid- night to midnight. Overall foo d consumption was a nalyzed b a se d on the amount of servings from MyPlat e.gov website. Fo od groups were based on the SSS healthy plate model, a culturally sensi- tive visual that depicts all of the food groups. The food groups include a vegetable group; fruit group; grain group; legumes, nuts, meat, fish, poultry, and eggs group; dairy group; and a s ep a- rate category of f at , oils, and sweets. Statistical Analysis There were a total of six ways the SSS program and SSSM program were examined which include: Demographics. Attendance. Knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes surrounding nutrition and physical activity via the Salsa, Sabor y Salud. Eating behaviors and food security via the WSU Food Be- havior Checklist. 24 Hour Recall. Program Satisfaction and Recommendation. The pre- and post-testing included the mean likert scale re- sults of the Salsa, Sabor y Salud Healthy Lifestyle Test and WSU Food Behavior Checklist. For the WSU Food Behavior Checklist there were three different likert scales that described results which included: 1 represented never to 4 represented always when referring to how often they do something; 1 rep- resented don’t drink juice to 4 represented 16oz or more when referring to the amount of juice they drink daily, and 1 repre- senting never to 5 representing 3 cups or more when referring to fruit and vegetable portions. For the Salsa, Sabor y Salud Healthy Lifestyle Test, and the program satisfaction and rec- ommend a t i on an a lysi s th e l i k ert s c a l e w a s: 1 r e pres e nte d strongly disagrees to 5 represented strongly agree. Mean scores on these items were compared using dependent t test. The mean 24 hours recall food group servings were all compared with dependent t test as well. For WSU Food Be- havior Checklist, Salsa, Sabor y Salud Healthy Lifestyle Test, and 24 hour recall the following measurements were compared: Pre- and Post-SSS Program. Between the Programs. Pre- and Post-SSSM Program. Both Programs Combined. Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel Data Analysis (version 2007). Statistical significance was set at p < .05. Results Demographics All participants were Hispanic and reported their race as white. Both women (75%) and men (25%) participated in the adult group with an age range between 18 - 59 years old. A total of 75% of the participants reported receiving government assis- tance. The total included in the analysis were: eight in the SSS program analysis, five in the analysis between programs, five in the analysis of the SSSM program, seven in the analysis of com- bined programs, and seven in the program satisfaction and rec- ommendation analysis (Figure 1). Attendance The SSS sessions participants had an average attendance of 72.92% or 4.375 out of the 6 sessions. For the SSSM sessions the participants’ average attendance was 75% or 3 out of 4 of the sessions. With SSS and SSSM combined, the participants’ average attendance was 73.75% or 7.375 out of 10 of the ses- sions. WSU Food Behavior Checklist Salsa, Sabor y Salud Program: There was a significant in- crease in participant’s consumption of more than 1 type of fruit Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 723  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 724 Combined Programs: When comparing the pre-SSS to post- SSSM, there was an increase in the use of fruits and vegetables as a snack from 2.14 fruit snacks per day/week to 2.86 per day/week (p < .047). Another significant result was the increase in use of low fat or non-fat dairy products 2.29 cu ps/ se r vi ng s/ day to 3.43 cups/servings/day (p < .047). There was an increase in having more than 1 type of fruit per day from 1.71 to 2.86 (p < .030). Also, there was a trend in having more than one type of vegetable per day from 2.00 types to 2.86 types of vegetables per day (p < .078). Label reading also improved substantially in the group, increasing from 1.29 labels read on average to 2.57 (p < .022). There was a significant increase in servings of vege- table and fruit portions, from 2.14 to 3.14 for vegetables and from 2.14 to 3.29 for fruits (p < .038 and p < .015, respectively) (see Table 1). and vegetables per day. Mean likert scale results increased from 1.63 to 2.50 for fruit and from 2.25 to 2.75 for vegetables (p < .021 and p < .033, respectively). Use of low fat or non-fat dairy products significantly increased fro m 2.38 to 3.38 ( p < .033) (Table 1). Salsa, Sabor y Salud Maintenance Program: There was a de- crease in sugary drink consu mption from 2.40 to 1.60 (p < .016). There was a strong trend in reading food labels when shopping with an increase in from 1.60 to 3.00 (p < .052). Also, there was a significant decrease from 3.00 to 2.00 for 100% juice con- sumption (p < .034) (Table 1). Salsa, Sabor y Salud Healthy Lifestyle Test Salsa, Sabor y Salud Program: There was an increase from 4.25 to 4.88 in knowing that eating healthy foods increases en- ergy levels (p < .049). There was strong trend in the particip ants knowledge of what food groups should be included in daily m eals , with the mean likert scale results increasing from 3.25 to 4.38 (p < .051) (Table 2). Salsa, Sabor y Salud Maintenance Program: There was no significant difference found for the SSS Healthy Lifestyle Test between the SSSM pre-testing and SSSM post-testing meas- urements taken (Table 2). Combined Programs: With the two programs combined, there was a significant increase in consumption of healthy foods in general, with the mean likert scale results increasing from 3.71 to 4.57 (p < .045). Healthy foods in general were defined as low fat, high fiber, low sugar, and high mineral and/or vitamin con- tent. Also, the results illustrated a trend in importance to bal- ance the type and amount of food eaten with daily level of physical activity, with the mean likert scale results increasing from 3.57 to 4.71 (p < .084) (see Table 2). Figure 1. Participants included in the study. Table 1. Pre-intervention a nd post-intervention for WSU Food Behavio r Checklist for an average day. SSS Program SSSM Program Combined Programs Variable n Pre- Intervention Post- Intervention p ValuenPre- Intervention Post- Intervention p ValuenPre- SSS Post- SSSM p Value Intake of Sweetened Drinksa 8 2 .13 ± .84 2.50 ± .54 .197 52.40 ± .551.60 ± .55.016* 71.86 ± .38 1.57 ± .54.172 Fruits and Vegetables as a Snacka 8 2.25 ± .71 2.38 ± .74 .685 52.80 ± .843.20 ± .84.374 72.14 ± .69 2.86 ± 1.07.047* Intake of 100% Fruit Juiceb 8 3.00 ± .93 2.75 ± .89 .170 53.00 ± 1.002.00 ± .71.034* 72.71 ± 1.25 2.00 ± .58.140 Intake of Vege tables Portionsc 8 2.38 ± .74 2.8 8± .84 .275 52.60 ± .553.20 ± .84.208 72.14 ± .69 3.14 ± .90.038* Intake of Fruit Portionsc 8 2.38 ± .74 3.00 ± .7 7 .180 52.80 ± .843.40 ± .55.208 72.14 ± .69 3.29 ± .76.015* 1 or More Types of Fruita 8 1.63 ± .74 2.50 ± .54 .021*52.80 ± .842.80 ± .841.000 71.71 ± .76 2.86 ± .90.030* 1 or More Types of Vegetablesa 8 2.25 ± .4 6 2.75 ± .46 .033*52.20 ± .4 52.80 ± .84.208 72.00 ± .78 2.86 ± .90.078+ Low or Non-F at Dairya 8 2.38 ± .74 3.38 ± 1.19 .033*53.00 ± 1.003.40 ± .55.477 72.29 ± .76 3.43 ± .54.005* Reading Fo od Labels a 8 1.38 ± .52 2.00 ± 1.07 .180 51.60 ± .553.00 ± 1.23.051+ 71.29 ± .76 2.57 ± 1.27.022* Note: aLikert scale: 1 = never, 2 = yes, sometimes, 3 = yes, often, & 4 = always; bLikert scale: 1 = Don’t D rink Juice, 2 = 8 oz, 3 = 12 oz, & 4 = 16 oz o r more; cLikert scale: 1 = None, 2 = 1/2 cup, 3 = 1 cup, 4 = 2 cups, & 5 = 3 cups or more; *Significance p < .05; +Trend p < .1.  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT Table 2. Pre-intervention and post-intervention for Salsa, Sabo r y Salud Testing. SSS Program SSSM Program Combined Programs Variable n Pre- Intervention Post- Intervention p Valuen Pre- Intervention Post- Intervention p Valuen Pre- SSS Post- SSSM p Value All Food Groups Should Be in ily Meala Das 8 3.25 ± .89 4.38 ± .92 .051+ 5 3 .60 ± .894.20 ± 1. 10.374 7 3.86 ± 1.22 4.29 ± .95.200 Eating Healthy Foods Increase Energya 8 4.25 ± .7 1 4.88 ± .35 .049* 5 5.00 ± .005.00 ± .00 1.000 7 4.71 ± .49 4.71 ± .76 1.000 I Try to Eat More Healthy Fo ods a 8 3.88 ± .99 4.25 ± .89 .504 5 4.20 ± 1.104.60 ± .8 9 .374 7 3.71 ± .95 4.57 ± .79.045* Balance Food Amounts with Exercisea 8 3 .75 ± 1.044.50 ± .93 .197 5 5.00 ± .005.00 ± .00 1.000 7 3.57 ± 1.13 4.71 ± .76.084+ Note: aLikert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 3 = agree, & 5 = strongly agree; *Significance p < . 05; +Trend p < .1. 24 Hours Recall Salsa, Sabor y Salud Program: There was an increase in se rv- ings of fruit with, the average number of servings per day in- creasing from .88 to 1.50 (p < .038). Participants’ results dem- onstrated a trend in increasing servings of whole grains, with the average number of servings increasing from 4.48 to 6.75 (p < .061) (Table 3). Salsa, Sabor y Salud Maintenance Program: There was a de- crease in average number of servings from 6.40 to 2.80 for the intake of whole grains (p < .028). Also, there was a signifi- cantly reduction in fat, sweets, or oils servings from 2.75 to 1.20 servings per day (p < .001). There was a decrease in the intake of the food group that included legumes, nuts, meat, fish, poultry, or eggs servings with the average number of servings decreasing from 3.80 to 1.90 (p < .025). A trend was observed in a decrease in consumption of dairy products, with the aver- age number of servings decreasing from 1.60 to .60 (p < .085) (Table 3). Combined Programs: There was no significant difference found for participants in the 24 hour recall data between the SSS pre- testing and SSSM post-testing measurements taken (see Table 3). Between Programs There was no significant difference found for participants in all SSS post-testing and SSSM pre-testing measurements ta ken, suggesting that participants maintained the changes made dur- ing the SSS program. Program Satisfaction and Recommendation At the end of the SSS program 98% of the participants re- ported being satisfied with this program and 98% would rec- ommend this program to friends and family. In contrast, at end of the SSSM program all 100% participants reported being sat is- fied with the program and 100% would recommend this pro- gram to friends and family. Discussion With the Hispanic population’s rapid increase in morbidity and mortality rates from chronic disease it is clear there is a need for a healthy lifestyle program (Caballero et al., 2007). Also, researchers have found that health programs presented in a culturally sensitive manner to the Hispanic population will have a higher success rate (Brown et al., 2002; Gilmer et al., 2005; Gordon, 2004). Another factor is the importance of a ma i n- tenance component, which is crucial for participants to retain information and to continue to practice he skills needed to live healthy lifestyles (Wilfley et al., 2007; Carels et a l., 2008; Lea n, 2011). The SSS and SSSM program demonstrate how to overcome the majority of the barriers for the Hispanic population to have a healthy lifestyle. This pilot research evaluated the effective- ness of the SSS program, the SSSM program, and the progra ms combined on health outcome measures. The programs individu- ally and combined revealed many significantly positive health indicator results. Additionally, participant satisfaction was ex- ceptionally high for both programs. This study further confirms that the SSS program improves healthy lifestyle choices based on measured outcomes. A pre- vious study by Bennett et al regarding the SSS program found that there was an increase in servings of fruit and vegetables, but the increase was not significantly significant (2011 ). In co m- paring findings between this study and a previous one (Bennett et al., 2011), both studies had a significant increase in partici- pants’ knowledge that eating healthy foods increases energy. There was a significant decrease in milk servings in general for the previous study, but with this study there was an increase in lower fat milk products. The reduction in milk products in the previous study may be due to less of an emphasis on lower fat milk product alternatives. There were no differences in weight and BMI during this study compared to the previous SSS pro- gram study, which may be due to the shorter length of time (6 weeks vs 8 weeks). Comparing this study to the study done by Bennett et al, there was an opposite effect on the grains. During this study there was an increase during the SSS program and in the Bennett et al study there was a decrease in grain serving consumption (2011). This is in agreement with the nutritional trend that the carbohydrate intake for Hispanics from the 1980s to the 2000s has increased (Fryar, Wright, Eberhardt, & Dye, 2012). Scores on the SSS program post-testing and the SSSM pro- gram pre-testing were compared to determine if there were any changes between the end of the standard program and the start up of the maintenance program. There were no differences, w hi ch Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 725  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT Table 3. Pre-intervention and pos t -intervention for th e 2 4 H o u rs Recall food group servings. SSS Program SSSM Program Combined Programs Variable n Pre- Intervention Post- Intervention p ValuenPre- Intervention Post- Intervention p ValuenPre- SSS Post- SSSM p Value Vegetables 8 2.34 ± 1.51 2.66 ± 3.02 .774 51.40 ± 1.953.15 ± 1.27.249 72.29 ± 1.78 3.39 ± 1.12.129 Fruit 8 .88 ± 1.25 1.50 ± 1.63 .038* 51.25 ± 2.541.25 ± 1.751.000 7.57 ± .98 2.04 ± 1.96.203 Grains 8 4.44 ± 2.87 6.75 ± 4.71 .061+ 56.40 ± 4.042.80 ± 1. 79.029* 74.43 ± 2.95 3.71 ± 2.22.537 Dairy 8 .94 ± . 8 6 1.19 ± .95 .663 51.60 ± .95 .60 ± .55 .086+ 7.57 ± .79 .71 ± .76 . 805 Legumes, Nuts, Meat, Poultry, Fish, Eggs 8 3.47 ± 1.66 3.22 ± 3.18 .861 53.80 ± .84 1.90 ± .95 .004* 72.71 ± 1.89 2.21 ± 1.00.342 Fats, Sweets, Oils 8 1.78 ± 1.54 2.59 ± 1.04 .264 52.75 ± 1.121.20 ± .84 .002* 71.86 ± 1.57 .8 6 ± .90 .197 Note: *Significance p < .05; +Trend p < .1. we assume to be due to the participants retaining the informa- tion given during the SSS program. Also, this further confirms that the SSSM program should focus on advanced concepts of nutrition and physical activity, given that participants appear to have learned the more basic SSS information. There is strong evidence that the SSSM program has signifi- cant positive health outcome indicators as well. All the infor- mation from the SSS program was provided in the SSSM pro- gram in a more advanced manner. The SSS progra m result s w e r e closely examined to determine which areas to focus on for the SSSM program and the results of the maintenance program indicate that the objectives were met. There was a decrease in sugary drink consumption that can be attributed to the emphasis of drinking more water, especially during the summer months, which was when the program was held. The decrease in the 100% juice consumption may be due to the emphasis of eating more fruit rather than drinking fruit juice during the sessions. There was a trend in increased food label reading while shop- ping. Food label reading was reinforced in this program and all participants were given the opportunity to show that they knew how to read food labels in Spanish as well as English, even if they were only fluent in Spanish. This was able to be achieved because an English and a Spanish food label of the same prod- uct were shown side by side on a handout to show what the English words mean and it was given to the participants to use as a guide with all future grocery shopping. Due to the increased grain intake during the SSS program, there was session content that helped participants better under- stand a serving size of grains, best types of grains, and approxi- mately how many serving they should have a day. This increase in specificity may have led to the decrease in servings of grains during this SSSM program, which was a positive result because participants were consuming more than the recommended serv- ings for grains in the SSS program. Both the SSS and SSSM sessions were further tested to see if there was a difference in whole grain and refined gain product consumption, but no sig- nificant difference was found. The SSSM sessions all focused on choosing lower fat, sugar, and oil options because in both the SSS programs studies done previously there was not a sig- nificant decrease, which is a contributing factor in the high obe- sity rate of the Hispanic population (Flegal et al., 2010). Surprisingly, there was a decrease in the food group that in- cluded legumes, nuts, meat, fish, poultry, and eggs servings. This was additionally analyzed to determine if one type of pro- tein group was responsible for the decrease in the servings. No significant difference was determined. There was a trend in decreasing dairy products, which may be due to the emphasize in drinking more water and increasing fruit and vegetable in- take during this program. It is important to understand the difference that the combined programs had from the pre-testing of the SSS program to the post-testing of the SSSM program. There was an increase in the use of fruits and vegetables as a snack, which was not shown in either program alone. After both programs, there was an in- crease in the use of low fat or non-fat dairy products and daily fruit portions. Also, there was an increase in types of fruit con- sumed per day and the trend in more than one type of vegetable consumed per day with the programs combined. Although these health behaviors were shown to increase significantly during the SSS program and not during the SSSM program, it is as- sumed that participants were encouraged to maintain them through the maintenance program which resulted in a significant change when program data was combined. There was no increase in the use of reading food labels when shopping with the SSS program but with the SSSM program there was a trend in this measured outcome. From the begin- ning of the SSS program to the end of the SSSM program it is clear that there was a statistically significant increase in food label reading when shopping. In both programs individually there was no increase in servings of vegetable portions, but with the combined programs there was an increase. Other results that w er e only found in the combined programs were that the participants were eating more healthy foods in general, and there was a tre nd that participants understood that it is importance to balance the type and amount of food they ate with physical activity. The success of the SSS program and SSSM program can be attributed to the key concepts that are reinforced in a culturally sensitive manner throughout all the sessions. Every sessio n rein - forces four key messages: eat foods from each of the food groups every day; be sensible about porti ons; be physically active e very Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 726  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT day; and take small steps for success. Also, each session pro- vides experiences and tips that promote healthier food choices compatible with the lifestyle and cuisine of Hispanic families. The programs involve the whole family, which is important for cultural sensitivity as well. There are fun physical activities for the entire family and discussions about the concept of “energy balance.” Finally, at every session there are cultural heritage and lifestyle connections to wellness (Gordon, 2004). Conclusion Although research has shown that SSS is a successful pro- gram, no health maintenance program was available to support the skills and behaviors established during the SSS program. Health maintenance programs are essential for people to retain information and to continue the practice of skills needed to live healthy lifestyles. Research has shown that health program par- ticipants will revert to their old behaviors within five years time. Many studies suggest that these reversions can be avoided with a health maintenance program (Anderson et al., 2001; Franz et al., 2007; Harvey-Berino, Pintauro, Buzzell, DiGiulio, Gold, Moldovan, & Ramirez, 2002; Collins et al., 2010). The SSS and the SSSM progra m have both shown to be be ne - ficial culturally sensitive healthy lifestyle programs. These are flexible programs that can be adjusted to meet the needs of an organization. In both the SSS and the SSSM programs, the participants increased nutrient dense food consumption and chose lower fat options for food. Furthermore, the participants had an increased overall knowledge of nutritious eating habits and an increased awareness about phy sical activity benefits in both p ro- grams as well. With the addition of the SSSM program partici- pants reported a significant increase in fruit and vegetable in- take, and food label reading when shopping, which was not seen in the SSS program alone. The re were some limitations to this pilot study which include a small sample size, limited vol- unteers to teach the program, time conflicts with church activi- ties, and the classes not being offered throughout the year. This research evaluated the effectiveness of SSS program and the impact of a SSSM program on outcome measures. T his pilot study further confirms the SSS program improves healthy lifestyle choices based on measured outcomes, but it also pre- sents new evidence that the results in the SSSM program pro- vides additional positive health outcomes. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the staff of St. Andrew’s Church in Ellensburg, Washington for providing their time and facility for this project. Also, a special thank you to all the vol- unteers for their hard work and dedication to both the SSS and SSSM program. REFERENCES Anderson, J. W., Konz, E. C., Frederich, R. C., & Wood, C. L. (2001). Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. American Society for Clinical Nutrition, 47, 579-584. Barrera, R., Garza, J., Guido, C., Leija, M., Lester, M., Lobo, B. et al. (2002). Salsa, Sabor y Salud: A healthy lifestyles program for young Latinos. Facilitators Guide Los Ninos Y Los Chicos. San Antonio: National Latino Children’s Institute, Kraft Foods Corporations. Bennett, V. A., & Sundsmo-Switzer, C. (2011) . Outcome measures of a family-based education approach with Mexican immigrants in the Yakima Valley. Creative Educa t ion, 2, 103-107. doi:10.4236/ce.2011.24052 Blackburn, M. L., Townsend, M. S., Kaiser, L. L., Martin, A. C., West, E. A., Turner, B. J., & Joy, A. B. (2006). Food behavior checklist ef- fectively evaluates nutrition education. California Agriculture, 60, 20-24. doi:10.3733/ca.v060n01p20 Brown, S. A., Kouzekanani, K., Garcia, A. A., & Hanis, C. L. (2002). Culturally competent diabetes self-management education for Mexi- can Americans. Diabetes Care, 25, 259-268. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.2.259 Caballero, A. E., & Tenzer, P. (2007). Building cultural competency for improved diabetes care: Latino Americans and diabetes. Journal of Family Practice, 56, S21-S30. Carels, R. A., Konrad, K., Young, K. M., Darby, L. A., Coit, C., Clay- ton, A. M., & Oemig, C. K. (2008). Taking control of your personal eating and exercise environment: A weight maintenance program. Eating Behaviors, 9, 228-237. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.09.003 Collins, C. E., Morgan, J. P., Jones, P., Flet cher, K., M a rtin, J., Aguirar, E. J., & Callister, R. (2010). Evaluation of a commerical web-based weight loss and weight loss maintenance program in overweight and obese adults: A randomized controlled trail. BMC Public Health, 10, 1-8. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-669 Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., & Ogden, C. L. (2010). Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303, 235-241. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.2014 Fryar, C. D., Wright, J. D., Eberhardt, M. S., & Dye, B. A. (2012). Trends in nutrient intakes and chronic health conditions among Mexican-American adults, a 25 year profile: United States, 1982- 2006. National Health Statistics Reports, 1, 1-20. Franz, M. J., VanWormer, J. J., Crain, A. L., Boucher, J. L., Histon, T., Caplan, W., & Pronk, N. P. (2007). Weight-loss outcomes: A sys- tematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. Journal of American Dietetic Associa- tion, 107, 1755-1767. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017 Gilmer, T. P., Philis-Tsimikas, A., & Walker, C. (2005). Outcomes of project dulce: A culturally specific diabetes management program. Annals of Pharmacother ap y , 39, 817-822. doi:10.1345/aph.1E583 Gordon, T. A. (2004). Recipe for good living. Hispanic, 17, 84. Harvey-Berino, J., Pintauro, S., Buzzell, P., DiGiulio, M., Gold, B. C., Moldovan, C., & Ramirez, E. (2002). Does using the internet facili- tate the maintenance of weight loss? International Journal of Obesity, 26, 1254-1260. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802051 Lean, M. J. (2011). Management of obesity and overweight. Medicine, 39, 32-38. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2010.10.003 Lopez-Quintero, C., Berry, E. M., & Neumark, Y. (2009). Limited English proficiency is a barrier to receipt of advice about physical activity and diet among Hispanics with chronic diseases in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109, 1769-1774. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2009.07.003 Murphy, S., Kaiser, L. L., Townsend, M. S., & Allen, L. (2001). Evaluation of validity of items in a food behavior checklist. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 101, 751-756, 761. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00189-4 Townsend, M. S., Kaiser, L. L., Allen, L. H., Joy, A. B., & Murphy, S. P. (2003). Selecting items for a food behavior checklist for a limited resource audience. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior, 35, 69-82. doi:10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60043-2 Townsend, M. S., Sylva, K., Martin, A., Metz , D., & Wooten -Swanson , P. (2008). Improving readability of an evaluation tools for low-in- come clients using visual information processing theories. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior, 40, 181-186. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.06.011 Wang, Y., Beydoun, M. A., Liang, L., Caballero, B., & Kumanyika, K. (2008). Will all Americans become overweight or obese? Estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity, 16, 2323-2330. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.351 Wilfley, D. E., Ste in, R. L., Saelens, B. E., Mock us, D. S., Matt, G. E., Hayden-Wade, H. A., & Epstein, L. H. (2007). Efficacy of mainte- nance treatment approaches for childhood overweight. Journal of the Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 727  S. R. FOX, V. A. BENNETT Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 728 American Medical Association , 298, 1661- 1673. doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1661 Wilkerson, J. (2008). Ten-year homeless plan: 2008 annual report. Washington: Community, Trade, and Economic Development. URL (last checked 25 Februar y 2012). http://www.commerce.wa.gov/desktopmodules/ctedpublications/cted publicationsview.aspx?tabid=0&itemid=6803&mid=870&wversion= staging |