World Journal of Nano Science and Engineering, 2012, 2, 148-153 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/wjnse.2012.23019 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/wjnse) A Study on Synthesis and Characterization of Biobased Carbon Nanoparticles from Lignin Prasad Gonugunta1,2, Singaravelu Vivekanandhan1,2, Amar K. Mohanty1,2, Manjusri Misra1,2* 1School of Engineering, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada 2Bioproducts Discovery and Development Centre, Department of Plant Agriculture, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada Email: *mmisra@uoguelph.ca Received May 12, 2012; revised June 27, 2012; accepted July 2, 2012 ABSTRACT Carbon nanoparticles were synthesized using lignin as a renewable feedstock by employing a freeze-drying process followed by thermal stabilization and carbonization. The effect of adding various amounts of KOH to a lignin solution on the solubility of the lignin, the freeze-drying process, the thermal stabilization of the freeze-dried lignin, and carbon nanoparticle formation was investigated through FTIR, DSC, SEM, TEM and surface area analysis. SEM investigations confirmed that the freeze-drying process caused the formation of lignin with a porous microstructure. TEM analysis indicates that the thermal stabilization of freeze-dried lignin prevented the formation of agglomerated carbon nanoparti- cles during the carbonization process. The smallest carbon nanoparticles were found to be 25 nm and were prepared from the lignin precursor with 15% KOH. Keywords: Carbon Nanoparticles; Lignin; Freeze-Drying; Carbonization 1. Introduction Carbon nanostructures such as fullerenes, carbon nano tubes/fibres/particles, and graphene sheets have been extensively studied due to their unique properties such as good electrical/thermal conductivity, excellent corrosion resistance, and enhanced chemical/bio compatibility [1- 5]. Hence, they have found a wide range of applications which include polymer composites, electrochemical en- ergy storage and conversion, catalysis, filtration, hydro- gen storage, and biotechnology [6-10]. Among the vari- ous carbon allotropes, particulate nanostructures receive more attention due to their versatility in fabrication and their extensive applications in polymer nanocomposites as nanofillers, waste-water treatment, biomedical imaging, and optical devices [11-14]. In general, these carbon nanoparticles have been synthesized using various syn- thetic processes including thermal carbonization, laser irradiation, sonication, and exfoliation [3,15-17]. One of the key factors in controlling the morphology and the yield of the carbon nanoparticles is the precursor material. Various carbon precursors such as graphite powders, petroleum pitch, carbon rich polymers, and other kinds of liquid/gaseous hydrocarbons have been extensively used for the fabrication of carbon nanoparti- cles [5,16]. However, there is a need for alternate carbon sources for the synthesis of carbonaceous materials due to increasing oil prices, depleting petroleum resources, their negative environmental impacts, and increasing demand for carbon-based nanomaterials in various emerg- ing fields. Hence, renewable carbon resources such as plant biomasses, biobased oils, and hydrocarbons have been explored for the fabrication of carbon nanostruc- tures [18, 19]. Among the various renewable precursors, lignin, which is widely known as a co-product of pulp and second generation cellulosic ethanol industries, re- ceives great attention due to its 1) carbon rich chemical structure, 2) abundance in nature, 3) chemical compati- bility, and 4) cost effectiveness. Thus, lignin has been investigated for the fabrication of carbonaceous materials such as carbon fibres and activated carbons. However, the synthesis of carbon nanoparticles from lignin has not been explored to a great extent [20,21]. Synthesis of carbon nanoparticles with controlled microstructures is possible through chemical modification and alteration of the processing parameters. In this, the challenging issue is to inhibit the agglomeration of lignin molecules during the carbonizetion process. Herein, we report the synthesis of carbon nanoparticles using lignin as a renewable feedstock by adopting a freeze-drying process in order to overcome the issues related to the formation of lumps during carbonization. Our ultimate aim is to investigate the effect of KOH ad- *Corresponding author. C opyright © 2012 SciRes. WJNSE  P. GONUGUNTA ET AL. 149 dition on the solubility of lignin, the freeze-drying proc- ess, and thermal stabilization as well as the formation of carbon nanoparticles. Freeze-drying of solubilized lignin can effectively produce ultra porous lignin structures. The thermal stabilization is involved in the retention of the obtained microstructure during the carbonizing proc- ess. This will help to avoid the agglomeration of carbon particles as well as the formation of lumps during the carbonization process and result in ultrafine nanoparti- cles. The complete process was investigated using FTIR, DSC, SEM, and TEM. 2. Experimental 2.1. Materials Protobind 2400 lignin (PL) is a by-product of the paper industries and was obtained from A L M Pvt. Ltd. India. Potassium hydroxide (KOH) in pellet form was procured from Sigma Aldrich and both the precursors were used as-received without further purification. 2.2. Methods Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of the various steps involved in the synthesis of carbon nanoparticles from lignin. Step 1: 2 g of lignin samples were dissolved in 500 ml of deionised water with various KOH concen- trations such as 0 wt%, 5 wt%, 10 wt%, and 15 wt% un- der sonication. The obtained solutions were labeled as PL-0, PL-5, PL-10, and PL-15 respectively. Step 2: Brown coloured lignin solutions were transferred into steel beakers and solidified using liquid nitrogen. The solidified lignin samples were freeze-dried in order to achieve porous lignin. Step 3: Thermal stabilization of the freeze-dried lignins was performed by heating them up to 250˚C at a 1˚C/min ramp rate. This helps in reten- tion of the porous microstructure during the carbonize- tion process. Step 4: After the thermal stabilization, proc- ess, thermo stabilized lignin samples were carbonized in a tubular furnace at 700˚C for 2 hours under nitrogen atmosphere by employing a 5˚C/min heating rate. The obtained carbon nanoparticles were used for further char- acterization. 2.3. Characterization Techniques A SAVANT-MODULYO (Model No: B1576) freeze dryer was used to dry lignin solutions, which allows the formation of porous lignin. The effect of thermal stabili- zation on the structural coordination of freeze-dried lig- nin was investigated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Thermo Scientific Nicolet TM 6700 FT-IR Spectrometer, USA employing attenuated total reflection infrared (ATR-IR) mode between 400 cm−1 and 4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. Differ- ential Scanning Calorimetric (DSC) analysis of the as-obtained as well as the thermo-stabilized freeze-dried lignin was performed using a TA Q-200 DSC in order to identify the glass transition temperatures (Tg). 3 to 5 mg of lignin samples were sealed in an aluminum pan sup- plied by TA instruments. Initially, the sample was heated to and maintained at 80˚C for 30 minutes in order to re- move existing moisture and then cooled to 0˚C. The DSC thermogram was recorded up to 250˚C employing a 20˚C /min ramp rate. All analysis was carried out in a nitrogen atmosphere.The micro-structure of the lignin samples were analyzed using a scanning electron micro-scope (SEM), FEI Inspect S50 Netherlands. Gold coating was Figure 1. Schematic of the various steps involved in the synthesis of carbon nanoparticles fr om lignin. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJNSE  P. GONUGUNTA ET AL. 150 performed for all the samples in order to enhance the SEM images. Synthesized carbon nanoparticles were characterized using a transmission electron microscope (TEM), JEOL 2010F FEG TEM/STEM, employing a 200 kV operating voltage. Brunauer-Emmet-Teller (BET) surface area analysis of the freeze-dried lignin samples and the synthesized carbon nanoparticles were measured with a NOVA station-C, Quantachrome through nitrogen gas sorption at 77.3 K. First, the samples were flow de- gased at 55˚C for 8 - 16 hours to remove the volatiles. BET surface areas were taken from a multipoint plot over a P/Po range of 0.05 - 0.35. 3. Results and Discussion The freeze-drying process caused the formation of po- rous lignin samples. However, these may fuse together and form lumps during the carbonization process, which results in bulk carbon material rather than well-defined carbon nanoparticles. In order to retain this porous struc- ture, lignin samples underwent a thermal stabilization process employing a low heating rate of 1˚C/min at 250˚C for 2 hours. The effect of thermal stabilization on their structural coordination, thermal behavior, and mi- crostructure were investigated by FTIR, DSC, and SEM analysis respectively. Figure 2 shows the FTIR spectra of the as-obtained and thermo stabilized lignin with dif- ferent KOH formulations. From Figure 2, the FTIR spectra indicates a characteristic peak of the lignin at 1590 cm−1 and 1500 cm−1, which represents the aromatic skeletal vibration [22]. Thermal stabilization of the freeze-dried lignin caused shifting of the peak at 1590 cm−1, which also increases with increasing KOH concen- tration for both the freeze-dried as well as thermo stabi- lized lignins. During the thermal stabilization, lignin un- dergoes condensation reactions in the presence of alkali metals, which also caused the formation of various or- ganic compounds such as metal formates as well as ace- tates [22]. These metal carboxylates have a very strong absorbance in the region of 1695 - 1540 cm−1, which caused the increased peak intensity at 1590 cm–1 [23]. Thermal stabilization also caused the formation of new peaks at 1385 cm−1 and 1315 cm−1, which is attributed to C-O-C stretching, which evidences the formation of ex- cess ether groups through condensation. This results in higher cross-linking and caused significant improvement in the glass transition temperature. Figure 3 exhibits the DSC thermograms of freeze- dried lignin before and after thermo stabilization. The DSC thermogram of freeze-dried lignin derived without KOH addition shows a Tg of 89˚C, which increases with increasing KOH concentration. Ucar et al. reported that the presence of alkali metal in lignin effectively caused the cross-linking through condensation, which also results (a) (b) PL+15% KOH PL+10% KOH PL+5% KOH P PL+15% KOH PL+10% KOH PL+5% KOH P Figure 2. FTIR spectra of freeze-dried lignin (a) as derived and (b) thermal stabilized. in the increased Tg in the DSC thermogram. Thermo stabilization further enhances the condensa- tion/cross-linking significantly thereby increasing the glass transition temperature and retaining the glassy state of lignin, which is confirmed through the DSC thermo- grams which do not show a significant Tg point. During thermal stabilization, lower heating rates increase the Tg of the lignin samples faster than the actual temperature, thereby avoiding the possibility of fusing and stabilizing the foamy structure. SEM analysis confirms this phe- nomenon, which is shown in Figure 4. The freeze-drying process caused the formation of porous structures, which is highly influenced by the presence of KOH. The freeze-dried lignin solution made without KOH addition formed a caused the formation of solid mass. Further, the thermal stabilization caused the successful retention of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJNSE  P. GONUGUNTA ET AL. 151 (a) (b) PL+15% KOH PL+10% KOH PL+5% KOH PL PL+15% KOH PL+10% KOH PL+5% KOH PL Temperature ˚C) Temperature ˚C) 121˚C 111 ˚C 107˚C 89˚C Figure 3. DSC thermogram of freeze-dried lignin (a) as porous structure. This resuis consistent with the re- were carbonized at 70 derived and (b) thermo stabilized. lt ported literature by Kadla et al. [20]. Thermol stabilized lignin samples 0˚C in nitrogen atmosphere for 2 hours. It was ob- served that the carbonized lignin without KOH results in the formation of solid mass where as the lignin samples modified with KOH yielded ultrafine particles. The chal- lenging issue in fabricating carbon nanoparticles is the yield, which indicates the efficiency of the conversion process. The thermal stabilization yield fraction (YTS) is the ratio of mass of lignin present after thermal stabili- zation (mTS) to before (mTS) thermo stabilization process. Similarly, carbonization yield fraction (YC) is the ratio of mass of carbonized material (mC) to mass of material present before carbonization process (mTS). Overall yield is the product of the yields of thermal stabilization (YTS) and the carbonization (YC). (I) A s derived (I I) The rmo-s tabilized 50µm 50µm 50µm 50µm 50µm 50µm 50µm 50µm (a) (a) (b) (b) (c)(c) (d) (d) Figure 4. SEM micrographs of freeze-dried lignin (I) as derived and (II) thermo stabilized ((a) PL; (b) PL + 5 wt% KOH; (c) PL + 10 wt% KOH; (d) PL + 15 wt% KOH). 0 TS TS TS m Ym C CTS m Ym 00 TS CC TTSC TS TS TS mm m YY Ym mm Table 1 summarizes the yields during the various st na ages involved in the synthesis of carbon nanoparticles. The specific surface area of the synthesized carbon noparticles were measured by employing BET surface area analysis The measured surface area of the carbon nanoparticles synthesized from lignin with different KOH concentrations of 0%, 5%, 10%, and 15 % are 0, 43, 47, and 23 m2/g respectively. From this analysis, it is confirmed that the addition of KOH to lignin up to 10% Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJNSE  P. GONUGUNTA ET AL. 152 increases the surface area and higher concentrations of KOH decreases the surface area. This may be due to the tendency of KOH to form agglomerates at higher KOH concentrations (15%). The results indicate that the addition of KOH reduces th 4. Conclusion les were successfully synthesized us- Table 1. Yields for thermaed and carbonized Sample al Yield of car Overall yield e overall yield, which may be due to the oxidation be- havior of KOH in lignin. Synthesized carbon powders were further characterized by TEM analysis to confirm the formation of nanoparticles. TEM micrographs of the carbon particles prepared from lignin source modified with different KOH concentration are shown in Figure 5. Carbon nanopartic ing lignin (Protobind 2400), a industrial co-product, as a renewable feedstock. The effect of KOH addition on the solubility of lignin, the freeze-drying process, thermal lly stabiliz carbon nanoparticles. Yield of therm name stabilization (YTS%) bonization (YC%) (YT%) PL 92.88 1.3 52.847 1.11 49.08 PL + 5 w88.46 2.5 55.072 1.9 48.71 w 75.97 3.1 56.7 2.1 43.07 w66.82 3.5 57.8 2.5 38.61 t% KOH PL+10 t% KOH PL+ 15 t% KOH 500 nm 100 nm 200 nm 200 nm (a) (b) (c) (d) Figure 5. TEM image of carbon nanoparticles synthe + 15 wt% KOH. ents he Ontario ministry of agri- NCES [1] O. ShenderovBrenner, “Carbon Nanostructure olid State and Ma- sized from (a) Protobind 2400; (b) Protobind 2400 + 5 wt% KOH; (c) Protobind 2400 + 10 wt% KOH; and (d) Protobind 2400 stabilization, and the carbonization behavior was inves- tigated. Freeze-drying inhibited agglomeration during the thermal stabilization process and resulted in the forma- tion of lignin with foamy and porous structures. Thermal stabilization of the freeze-dried lignin caused condensa- tion followed by cross linking reactions which increased the Tg of the lignin gradually; thereby retaining its glassy nature beyond its degradation temperature as confirmed by FTIR and DSC analysis. The carbonization of the thermal stabilized lignin caused the formation of carbon nanoparticles with a size range between 25 and 150nm. TEM analysis of these synthesized carbon nanoparticles indicates that the addition of KOH influences their parti- cle size significantly. 5. Acknowledgem The authors are thankful to t culture, food and rural affairs (OMAFRA) new directions and alternative renewable fuels research program (2009) for supporting this research. REFERE a, V. Zhirnov and D. s,” Critical Reviews in S terial Sciences, Vol. 27, No. 3-4, 2002, pp. 227-356. doi:10.1080/10408430208500497 [2] S. Iijima and T. Ichihashi, “Single-Shell Carbon Na tubes of 1-nm Diameter,” Nature no- , Vol. 363, No. 6430, of Fluorescent Carbon Nanoribbons, 1993, pp. 603-605. [3] J. Lu, J. Yang, J. Wang, A. Lim, S. Wang and K. P. Loh, “One-Pot Synthesis Nanoparticles, and Graphene by the Exfoliation of Graphite in Ionic Liquids,” ACS Nano, Vol. 3, No. 8, 2009, pp. 2367-2375. doi:10.1021/nn900546b [4] A. K. Geim and K. S. Novoselov, “The Rise of Gra- phene,” Nature Materials, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2007, pp. 183-191. doi:10.1038/nmat1849 [5] Y. Wang, S. Serrano and J. Santiago-Aviles, “Conductiv- ity Measurement of Electrospun PAN-Based Carbon Nanofiber,” Journal of Materials Science Letters, Vol. 21, No. 13, 2002, pp. 1055-1057. doi:10.1023/A:1016081212346 [6] P. Ajayan and O. Zhou, “Appli tubes,” Carbon Nanotubes, Vol. cations of Carbon Nano- 80, 2001, pp. 391-425. doi:10.1007/3-540-39947-X_14 [7] R. H. Baughman, A. A. Zakhidov and W. A. De Heer, “Carbon Nanotubes—The Route toward Applications,” Science, Vol. 297, No. 5582, 2002, pp. 787-792. doi:10.1126/science.1060928 [8] W. Choi, I. Lahiri, R. Seelaboyina and Y. S. Kang thesis of Graphene and Its , “Syn- Applications: A Review,” Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2010, pp. 52-71. doi:10.1080/10408430903505036 [9] N. Sinha and J. T. W. Yeow, “Carbon Nanotubes for Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJNSE  P. GONUGUNTA ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. WJNSE 153 ransactions on Biomedical Applications,” IEEE TNano- Bioscience, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2005, pp. 180-195. doi:10.1109/TNB.2005.850478 [10] E. Frackowiak and F. Beguin, “Electrochemic of Energy in Carbon Nanotubes al Storage and Nanostructured Car- bons,” Carbon, Vol. 40, No. 10, 2002, pp. 1775-1787. doi:10.1016/S0008-6223(02)00045-3 [11] S. C. Ray, A. Saha, N. R. Jana and R. Sarkar, “Fluore cent Carbon Nanoparticles: Synthesis s- , Characterization, and Bioimaging Application,” Journal of Physical Chem- istry C, Vol. 113, No. 47, 2009, pp. 18546-18551. doi:10.1021/jp905912n [12] J. Yu, Q. Zhang, J. Ahn, S. F. Yoon, Rusli, Y. J. Li, B Gan and K. Chew, “Synthesis o . f Carbon Nanoparticles by Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition and Their Field Emission Properties,” Journal of Materials Science Letters, Vol. 21, No. 7, 2002, pp. 543-545. doi:10.1023/A:1015456921100 [13] R. Haydarov and O. Gapurova, “Applicatio Nanoparticles for Water Treat n of Carbon ment, Water Trea tment Technologies for the Removal of High-Toxicity Pollut- ants,” In: M. Václavíková, K. Vitale, G. P. Gallios and L. Ivaničová, Eds., Water Treatment Technologies for the Removal of High-Toxicity Pollutants, Springer, Berlin, 2010, pp. 253-258. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3497-7_25 [14] M. M. Saatchi and A. Shojaei, “Mechanical Performance of Styrene-Butadiene-Rubberfilled with Carbon Nano Particles Prepared by Mechanical Mixing,” Materials Sci- ence and Engineering: A, Vol. 528, No. 24, 2011, pp. 7161-7172. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2011.05.089 [15] T. Akiyama, N. Akae, M. Hayasaka and N. Ishikawa, “Nanoparticle Recovery Using a Fume Collector Com- prised of Carbonized Refuse-Derived Fuel,” Metallurgi- cal and Materials Transactions B, Vol. 35, No. , 2004, pp. 993-998. [16] S. L. Hu, K. Y. Niu, J. Sun, J. Yang, N. Q. Zhao and X. W. Du, “One-Step Synthesis of Fluorescent Carbon Na- noparticles by Laser Irradiation,” Journal of Materials Chemistry, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2009, pp. 484-488. doi:10.1039/b812943f [17] H. Li, X. He, Y. Liu, H. Huang, S. Lian, S. T. Lee, et al., “One-Step Ultrasonic Synthesis of Water-Soluble Carbon Nanoparticles with Excellent Photoluminescent Proper- ties,” Carbon, Vol. 49, No. 2, 2011, pp. 605-609. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2010.10.004 [18] M. Sharon, “Carbon Nanomaterials and Their Synthesis from Plant-Derived Precursors,” Synthesis and Reactivity in Inorganic, Metal-Organic and Nano-Metal Chemistry, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2006, pp. 265-279. doi:10.1080/15533170600596048 [19] K. Sudo and K. Shimizu, “A New Carbon Fiber from 70440113 Lignin,” Journal of Applied Polymer Science, Vol. 44, No. 1, 1992, pp. 127-134. doi:10.1002/app.1992.0 “Lignin—From Natu- [20] P. Carrott and M. Ribeiro Carrott, ral Adsorbent to Activated Carbon: A Review,” Biore- source Technology, Vol. 98, No. 12, 2007, pp. 2301-2312. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2006.08.008 [21] J. Kadla, S. Kubo, R. Venditti, R. Gilbert, A. Compere (02)00248-8 and W. Griffith, “Lignin-Based Carbon Fibers for Com- posite Fiber Applications,” Carbon, Vol. 40, No. 15, 2002, pp. 2913-2920. doi:10.1016/S0008-6223 egener, “Analytical [22] G. Ucar, D. Meier, O. Faix and G. W Pyrolysis and FTIR Spectroscopy of Fossil Sequoiaden- dron Giganteum (Lindl.) Wood and MWLs Isolated Hereof,” European Journal of Wood and Wood Products, Vol. 63, No. 1, 2005, pp. 57-63. doi:10.1007/s00107-004-0530-x [23] G. Socrates, “Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts,” John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, 2004.

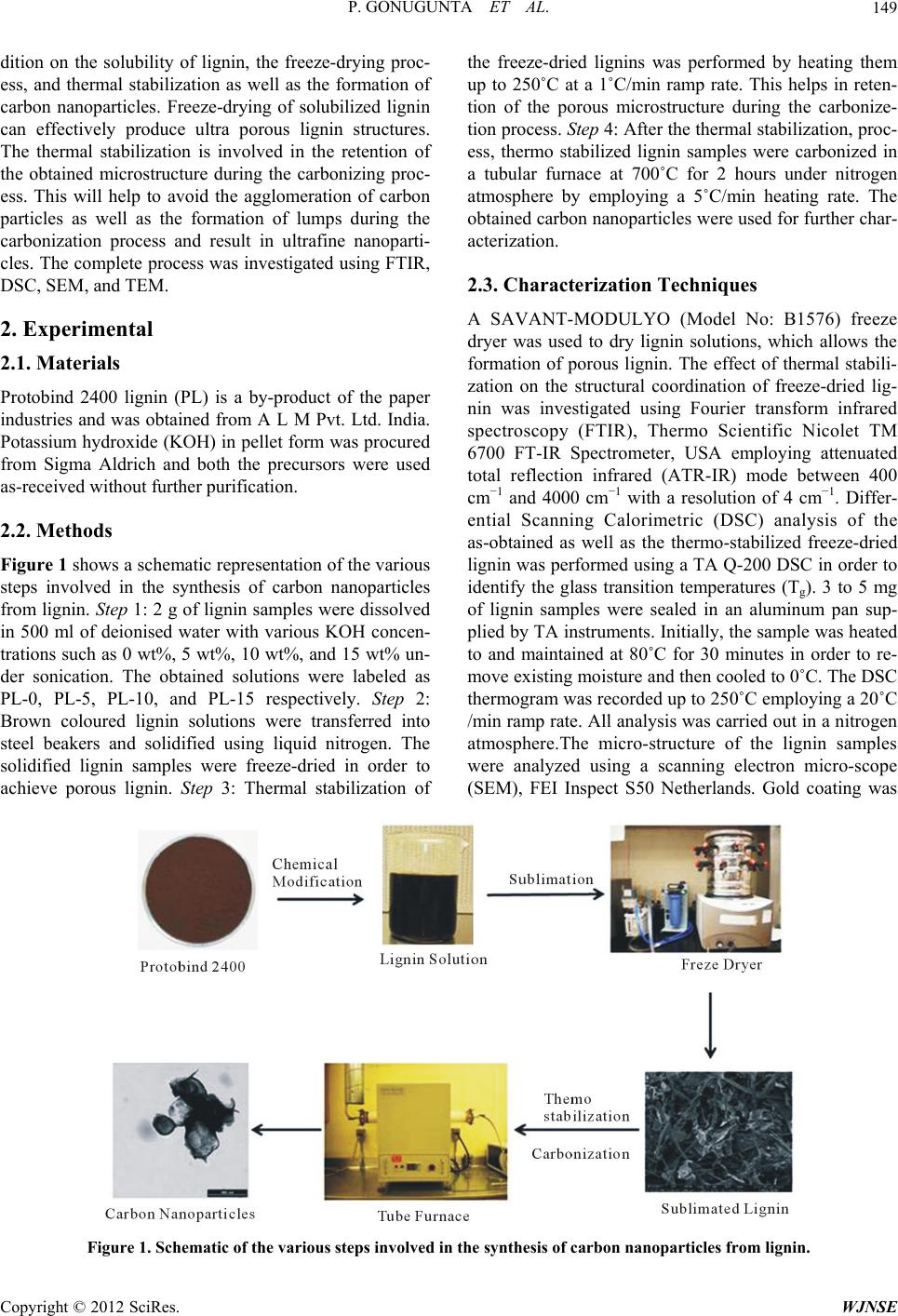

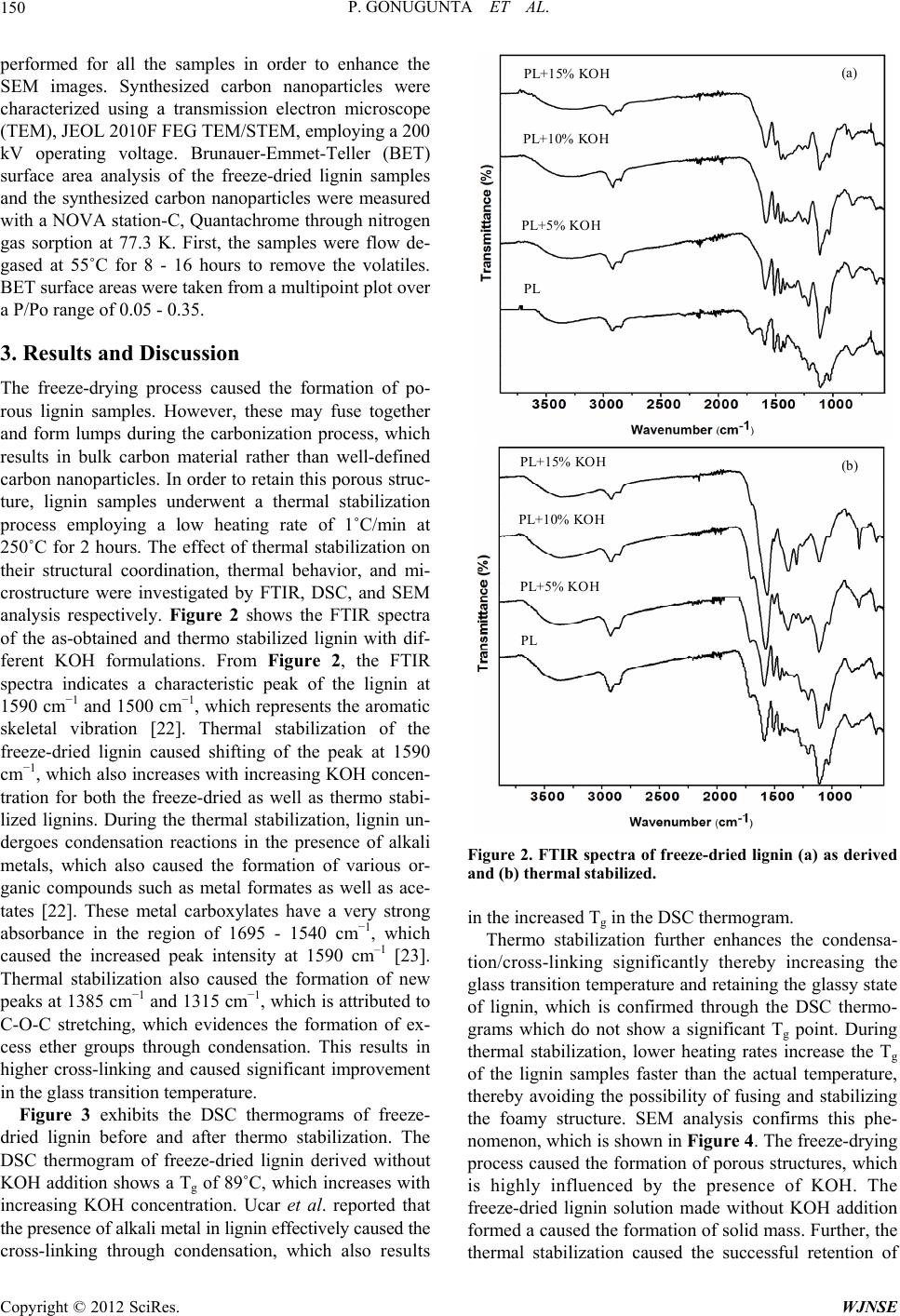

|