iBusiness, 2012, 4, 246-255 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ib.2012.43031 Published Online September 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ib) Explanatory Models of Ch ange of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing Nayeli Manzano1, Luis Rivas1, George Bonilla2 1Instituto Politécnico Nacional, México City, México; 2CETYS Universidad, Tijuana, México. Email: nayeli_manzano@yahoo.com.mx, larivas33@hotmail.com, gbon53@gmail.com Received January 16th, 2012; revised February 9th, 2012; accepted March 25th, 2012 ABSTRACT This work describes consumer behavior models that present sustainable empirical evidence on consumer behavior with social marketing applications given in the state of art. For this research, the most important and relevant databases were consulted in order to get to the fron tier of knowledge. It analyzes model differences and their variables, and presents a comparison among the models. One of the most interesting findings is the description of the stages of evolution in the purchasing decisions and the identification of the inhibitors of each stage. Five models were founded and compered as a result of the analysis. The five phases of fair consumers’ behavior: disinterest, concern, attitude, action and commitment behavior will be discussed. Keywords: Social Marketing; Sustainable; Consumer Behavior; Fair Trade 1. Introduction The foundation of social marketing is behavior change. According to Leal (2000) [1] consumer behavior en- compasses all the activities that precede, accompany and follow purchasing decisions and in which the individual or organization are actively involved in order to make informed choices. In social marketing, the behaviors that need to change are those that carry important consequences. The cones- quences mean the degree of involvement in a specific act of purchase and the perceived risk that such purchase may be associated with (Leal [1]). In other words, con- sumers gather information, think their decision through and most often find themselves emotionally involved in the selection process. These behaviors are not spontaneously realized. They have been researched and it has been concluded that there are different answers depending on which stage of the model the individual finds himself, the information that has been compiled and the stimuli used. Furthermore, these behaviors are carried out gradually and through clearly defined stages. From research, different models have been developed which are explained below. Research Background The issue of behavioral change has been approached from several perspectives, mainly from the standpoint of health, as it aims to change unhealthy behaviors of indi- viduals and improve health, reduce risk of diseases, chronic diseases and thus improve the quality of life of the population. The field of research has focused on the study of behavior change both at the individual and group levels. At the individual level, we have studied intrapersonal factors such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, motivation, opinions of themselves, developmental history, experience, skills and behavior (Glanz and Rimer 1996) [2]. According to Prochaska and DiClemente (1983) [3], for a person to change, behavior must go through a five- stage process: 1) Precontemplation The individu al is not aware of the problem and has not thought abou t changing. 2) Contemplation The person is thinking of changing in the near future. 3) Decision Making plans to change. 4) Action Implementation of specific action plans. 5) Maintenance Continuation of desirable actions, or repeating periodic recommended step. It is also relevant to mention the theory of behavioral change at the individual level advanced by the Health Belief Model (HBM), developed by researchers at the US Public Health Service in the 1950s. Th is social cognition model suggests that if people hav e information about the severity of their disease and their own susceptibility to it, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing 247 will adopt healthy behaviors if they perceive that the recommended b ehavior will be effective (Ca brera, Ta scó n and Lucumí, 2001) [4]. The HBM model is one of the most influential and widely used models to explain pre- ventive actions, people’s responses to symptoms, dis- ease diagnosed and health related behaviors. Another work of relevance is the consumer’s theory of information processing, which addresses the processes by which consumers receive and use information in their decision-making. This work proposed by James Bettman in 1979 [5] reflects a combination of rational, intellectual and motivational concep ts, the main assumptions are that individuals are limited in terms of how much information can be processed and to increase the use of information, people combine bits of information in “blocks” and cre- ate decision rules, called heuristics, to make faster and easier choices. It describes a cyclical process of informa- tion search, selection, use and learning as well as feed- back for future decision s. Another interesting work published a comprehensive framework for understanding human behavior, based on a cognitive formulation of the theory of social learning (Glanz and Rimer [2], Bandura [6]). In group-level models is important to mentioned Glanz and Rimer [2], and Rothman [7], because of their at- tempts to achieve goals of better health for individuals, groups, institution s and communities. Is relevant to mentioned the theory of diffusion of in- novations, used to understand costumers concerns re- garding the application of new products or technologies and for dissemination of strategies and promotional tools [8]. 2. Research Methods 2.1. Data Source This research utilized the Literature Review method con- ducted using the following databases: ProQuest digit al dissertat i o n ProQuest Multiple Databases ABI Inform Emerald OCENET Questia Green FILE, EBS CO Host D a tabas e The research focuses on themes related to the types and models of consumer behavior of social marketing products. As a result, an analysis of the models supported by the state of the art was conducted. 2.2. Explicative Models of Behavior Change 2.2.1. Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross (1992) Spiral Mo d el of the Ph as es of Change Andreasen (1995) [9] suggests that the most useful model for applying social marketing is the transtheoreti- cal model of change behavior developed by James O. Prochaska and Carlo C. DiClemente in 1983 [3]. Since 1983, Prochaska and DiClemente have completed vari- ous studies that have evolved into their spiral model of the phases of change (Prochaska, DiClemente and Nor- cross, 1992) [10]. Prochaska is Director of Cancer Pre- vention Research Center and Professor of Clinical and Health Psychology at the University of Rhode Island. DiClemente is Professor and Chair, Department of Psy- chology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and Norcross is Professor of psychology at the Univer- sity of Scranton. This model emerges out of the various researches un- dertaken by Prochaska and DiClemente since 1983. They have focused their research principally on behavior mo- dification in cases of addictive behaviors. They have con- centrated their studies mainly on smokers (Prochaska and DiClemente [3]), but also with people experiencing psy- chological stress (Prochaska and DiClemente [11]), indi- viduals undergoing psychotherapy (Prochaska y Costa, [12]), individuals using addictive substances (DiClemente et al., [13]), and persons enrolled in weight control pro- grams (Prochas ka, et al. [14]). As a result of the above studies, these researchers de- veloped the Spiral Model of the Phases of Change, which infers change as a progressive five-step process. Figure 1 will help explain th e five-step model. Precontemplation Stage. In this phase many individu- als are unconscious about their problems. In this phase individuals have no intention of changing their behavior in the immediate future. However, family, friends, neighbors are clearly conscious of the prob- lem. Often, individuals change their behavior because of internal and external pressures, but when such pressures subside they fall back into their old habits. (Prochaska, DiClemente and Norcross, [10]) confirm that resistance to recognize or to modify the problem behavior is the hallmark of the precontemplation phase. Contemplation Stage. People in this stage are con- scious that a problem exist and are seriously thinking of overcoming it, but they have yet to make a com- mitment. The authors found in their studies that peo- ple can remain in this stage for long periods of time, even years. In a study conducted by Prochaska and DiClemente they followed for two years a self-as- sisted, without external help, group of 200 smokers on the contemplation stage (Prochaska and DiCle- mente, [11]). Another aspect found by investigators at this stage is that people in this stage weight the pros and cons of the problem and the solution to the prob- lem. People who are at this stage seem to struggle Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB 248 Figure 1. Spiral model of the phases of change (Prochaska, DiClemente, and Norcross, [10]). with the positive ev aluation s of the add ictive b ehav ior and the amount of time and energ y that will cost them to so- lve the problem (DiClemente, et al., [13]). The principal elements of the contemplation stage are to 1) focus on the solution rather than the problem, and 2) think more about the future than the past. Preparation Stage. This is the stage that combines in- tention and behavioral criteria. Individuals at this stage intend to act in the next month but have been unsuccessful in the previous year. As a group, indi- viduals who are ready for action, report some small behavioral changes, such as smoking five cigarettes less or delaying their first cigarette of the day 30 minutes longer than people in the contemplation or precontemplation stages (DiClemente, et al., [13]). Although these people have made some reductions in their disruptive behavior such a reduction does not reach a criterion for effective action. However, they intent to take action in the near future. The authors originally called this stage decision-making. Action Stage. According to the authors, it is at this stage in which individuals modify their behavior, their experiences, or environment to overcome their problems. It is also at this stage that the most evident behavioral changes take place and require consider- able commitment of time and energy. At this stage individuals received much external recognition and the changes to the addictive behavior are more visible. The authors classify individuals into the action stage if they have altered their addictive behavior over a period of one day to six months. A successful change to addictive behavior means reaching a particular cri- terion such as abstinence. The hallmarks of this stage are behavior modification to an acceptable criterion and significant effort to ch ange. Maintenance and Relapse Prevention Stage. This is the stage where people work to prevent relapse and consolidate the gains made in the action stage (Pro- chaska, DiClemente, Norcross [10]). This stage is a continuation of change, not lack of it, so it should no t be considered as a static stage. For addictive behav- iors this stage lasts from six months to an indetermi- nate period past the initial action, rather some main- tenance behaviors persist throughout life. The authors classified people who abstain from falling back into addictive behavior and consistently pursue a new be- havior for more than six months during this phase. The hallmarks of this stage are to stabilize the behav- ior change and avoid relapse. Studies in the withdrawal process of smoking and al- cohol consumption show that it is typical for a person to be in repeated suspension and relapse cycles many times before attaining permanent abstinence. Therefore, Pro- chaska, et al. 1992, [14] illustrate this change as a spiral model in which the person goes through suspension and relapse, return to contemplation or preparation, but al- ways from a more favorable starting point than in the previous cycle. Progression through the stages is cyclical,  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing 249 not linear. 2.2.2. Kotler and Andreasen Model (1991) [15] According to Leal [1], Kotler and Andreasen [15] pro- posed a model during which the stages are grouped into five categories according to the marketing tasks that must be performed by a specialist in behavioral change. Ac- cording to the author, these tasks referred to the five stages of Prochaska and DiClemente [3]. In Figure 2, you can observe the different phases of the model proposed by Kotler and Andreasen, and the steps of the marketing efforts for behavior change. 1) Recalling the model of Prochaska and DiClemente, social marketing agents must educate consumers who are in the precontemplation stage to start to change their va- lues with the objective to help themselves begin the change process. 2) For consumers who are already in the contempla- tion stage, what social marketing agents need to do is to persuade and motivate them to move to the next stage and consequently change their behavior. 3) In the preparation phase consumers need help to figure out how to behave and perhaps support on control- ling their behavior. 4) For consumers in the action phase who have already performed the behavior once or several times the social marketing agents must confirm the behavior change by reinforcing it through training to finally move the con- sumers to the final phase of the model which is the final confirmation. Leal [1] makes a model comparison between the change behavior model of Prochaska and DiClemente and the Kotler and Andreasen model which is presented in Table 1. Through comparison analysis between these two models, Leal [1] found that: “The social marketing task facing those who wish to produce a change in be- havior, differ for each of the five categories of the ge- neral stages of Prochaska and DiClemente model there- fore, the main techniques for behavior change in use will also change.” 2.2.3. Leal’s M o d e l of the Beha vior Chan ge P r oc ess Antonio Leal Jimenez researcher at the University of Cadiz, Spain, proposes a new model called Model of be- havior change process. Leal builds on explanatory mod- els of behavior change in marketing, psychosocial studies on attitudes and the process of change, and in his own experience. The model Leal proposes is divided into four significant phases for social marketing. The focus given by the author to these phases is from the perspective of the adopted objective and the appropriate marketing strategies. This model is illustrated in Figure 3. The phases of Leal’s model are: 1) Observation. At this stage the target adopter does Figure 2. Kotler and Andrease n mode l [15]. Table 1. Comparison between two models of consumer change behavior. Prochaskay DiClemente’ s phasesMarketing tasks Phases modify by Andreasen Precontemplation Creating conscience and interest changing values Precontemplation Contemplation Persuation, motivation Contemplation Preparation To order Action Creating action Action Confirmation Maintaining ch ange Maintenance not even contemplate the desired action. This may be due to three reasons: first, because the individual is unaware of the social problem, for example, the effects of certain drugs, and second because he mistakenly believes he is not directly affected by the problem, for example hetero- sexual couples who do not consume drugs and the spread of AIDS, and finally because the individual has values and beliefs that are different from the proposed behavior change, for example, certain religions that are against donating bl o od. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing 250 Figure 3. Leal [1] model of behavior change process. 2) Analysis. In this phase the author includes th e adop- ters that are conscious of th e possibility of chang ing their attitude. They’re not against the change but are still ana- lyzing the pros and cons of such change. 3) Behavior. Once the individual has reflected upon the advantages and disadvantages of change the individ- ual may finally decide to adopt the new behavior. The author suggests that the way to motivate depends on whether the behavior is to be carried out once (organ donation), whether the behavior should be performed in a consistent manner (detoxification programs), if the be- havior change is permanent (conservation of natural re- sources), or if the change is permanent but related to sp e- cific situations (who drives a vehicle after alcohol con- sumption). 4) Affirmation. A reminder strategy is sometimes nec- essary with certain individuals as not to let the socially desirable behavior wane. Leal [1] mentions that this is a crucial stage, since it depends on the previous work for its continued success. Once the model was proposed, Leal [1] continues to direct his research focus on the challenges faced in each stage of the model and the most effective strategies through which the social marketing program can get in- dividuals to move from one phase to another in a sequen- tial continuously moving process until the final affirma- tion phase of the behavior is reached. 2.2.4. Shoppi n g Behavior Model of the Ecological Consumer (Bañeguil and Chamorro, [16]) This model was developed from research conducted by professors Tomás Bañeguil and Antonio Chamorro, Fac- ulty of Economics and Business, University of Extre- madura, Spain. As presented in previous models the aim of this research was to develop a model of behavior change specifically directed to the ecological consumer buying behavior and in this research to find the factors that hinder or prevent the individuals’ initial concerns to transform into action in terms of environmental respon- sibility. Bañeguil’s and Chamorro’s [16] research was based partially on models developed by other authors such as Calomarde, J. (2000) [17], Fuller, D. (1999) [18] and Kalafatis, Pollard, East an d Tsogas, (1999) [19]. The authors state that not all environmentally con- cerned citizens become green consumers, for example, persons that embrace ecological values are not necessar- ily making purchasing decisions of organic products. Starting from the idea that environmental awareness can occur in an individual in varying degrees (Kalafatis, Pol- lard, East and Tsogas [19]), the model proposed by the authors considers that a person can be located in five different dimensions of environmental awareness and to move from one dimension to another requires overcom- ing a number of inhibitors, as shown in Figure 4. The first stage, which the authors denominate “eco- logical indifference”, places all people who espouse the belief that the damaged to the natural environment is not a grave problem for humanity. Although they claimed that most individuals from developed nations are con- scious that this is indeed a real problem. The authors call the next stage “environmental con- cern” which places people who believe that there is a problem to be solved and in this stage they measure the individual’s level of interest in environmental issues and their perception of the gravity of the problem. The same individual may have varying degrees of concern about various environmental problems such as water pollution, air pollution, etc. Concern is a previous step to behavior change and in this case an ecological behavior change. The more concerned an individual is about environ- mental problems the greater the possibility that this con- cern will translate into purchasing behavior (Kalafatis, Pollard, East and Tsogas [19]). The phase of “ecological attitude” measures the ten- dency to take personal action to solve environmental pro- blems and the willingness to accept established or pro- posed government measures. There are certain people who are called “eco-actives” which are those persons that accept that a problem exists and they should do some- thing about it, that is, a person with a positive attitude toward the environment. Unlike the “eco-passives” or free riders who hope that the actions of others are benefi- cial to them or they think that the solution to a problem belongs to others. The authors do believe that there are inhibiting factors to move from one stage to another. The author’s call this fourth phase, the ecological de- cision phase in which the individual decides to take real measures to protect the environment. However, an eco- logical attitude does not always translate into a decision to act. The authors believe that this gap is due to some inhibiting factors that p revent indiv iduals to decide to act even though they know they should. In the last phase of the Bañguil and Chamorro model, e Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB 251 Buying inhibitors: Figure 4. Ecological consumer purchasing model of Bañeguil and Chamorro. action implementation or actual environmental perform- ance is when the individual implements the measures for environmental protection. These measures may relate to social behavior, buying behavior or consumer behavior. The individual will make an assessment among real eco- logical alternatives and those that are not. This will help to move from the decision phase to the action phase. Inhibiting Factors Knowing what factors make it difficult or impede the initial environmental concern from transforming into action is key for companies to design an effective (so cial, ecological) marketing strategy. For an individual to move from one stage to a higher one of the previously de- scribed model he/she must overcome a number of in- hibitors. As a result of their investigations the authors consider the following factors as inhibitors to the creation of an ecological attitude : The perceived effectiveness of the consumer (PEC): the ability that the person believes it has to influence the environment (Noya, Gomez and Paniagua, 1999) [20]. The perception of the effectiveness of the action. The capacity that the individual ascribes to a concrete way to influence the environment, for example, waste re- cycling or buying organic products. Perhaps the per- son believes he/she could and should do something to affect change, but do not give the same value to buy- ing green products that to recycling waste. Perceived personal benefit of the action. Individuals who have good environmental behavior do not nec- essarily gain a personal benefit by this action, on the contrary, it takes money, time, effort, and comfort to adopt good environmental behaviors, although these behaviors do generate a benefit to society. Further- more, because environmental benefits are long term the individual will not known whether adopting this behavior was good or not for the environment. In this case, ecological concerns will become ecological at- titude only when the individual adopts an altruistic at- titude and not a selfish one. If the person is not altru- istic he or she will move to the stage of ecological at- titude only if the problem affects the person directly. Individuals who are at the ecological decision phase compare ecological behaviors with normal behaviors. The following will explain the variables identified by the authors as inhibitors to move to the ecological deci- sion phase, in other words the variables that prevent a person from doing something even though he or she knows they must do something: 1) Confusion created by ignorance. The fact that the individual knows that a pro- blem exist and must act, does not necessarily means the  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing 252 individual knows how to act. A positive ecological atti- tude is not necessarily indicative of a high level of envi- ronmental training (Schlegelmilch, Diamantopoulos and Tassel, 1996) [21]; 2) Skepticism. This research results show that today’s consumers do not believe that state- ments about ecological organic products are true. The au- thors mentioned that th is lack of credibility is mainly due to the lack of tangibility of the ecological quality of the product. For example, it is easy to check the quality of trousers or the sound quality of a stereo system, but not environmental quality even for consumers with sufficient knowledge on the subject. To reach the final phase, action implementation or real ecological behavior, individuals must confront certain inhibitors of ecological shopping which are: Price. The researchers concluded that the segment of buyers that pay a bit more for ecological products is not that large as suggested by Philips (1999) [22]. What is sprouting is a generation of consumers that expect “products respectful to the environment as well as respectful to the pocketbook”. Perception of quality and effectiveness. Some indi- viduals may have the perception that environmental friendly products are lower in quality when compared to normal products. However, according to research results conducted by the Entorno Foundation (2000) [23] shows only 3 percent of those individuals sur- veyed mentioned that they don’t purchase ecologi- cally friendly products because they have lower qual- ity. Product availability in the marketplace. The ecologi- cal consumer does not easily find products with the ecological attributes required. In a survey conducted by the Entorno Foundation in 2000, 19% of the re- spondents to the question “Reasons for not buying ecological products” stated that they could not find them. Brand loyalty. Brand loyalty is a barrier for consum- ers to acquire ecological friendly products because they are usually satisfied with the products they al- ready use due to product satisfaction and met needs. Ecological brands must demonstrate that it not only satisfies needs but it is environmentally friendly. Lifestyle and comfort. Even when the ecological pro- duct has good price and quality in comparison to tra- ditional products it implies a change in lifestyle and therefore consumers may stop purchasing such item. For example, a mother may enforce her family to re- cycle paper however, but she may not be willing to use cloth diapers in place of disposable ones. The conclusions reached by the researchers showed that even though society may worry about the environ- ment the percentage of people reaching the last stage of the model is not sufficient enough to reach sustainable development. According to the Bañeguil’s and Chamor- ros’s model the gap between phases is due to certain fac- tors that they cluster into three types: 1) Attitude inhibiting factors. These include percep- tions of personal efficiency, perception of efficiency of action, and the perception of personal be nefit. 2) Decision inhibiting factors. Here the authors group ignorance and skepticism together. 3) Purchase inhibiting factors. This is where price, perceived quality, brand loyalty toward traditional brands and models, lifestyle, and the availability of commercial establishments are clustered. To overcome inhibiting factors, the authors recom- mend the increase of ecologically responsible behaviors and the demand for ecological products through social marketing ad campaigns, commercial marketing ads, and environmental marketing for the purpose of allowing in- dividuals to overcome inhibiting factors. 2.2.5. Awarene ss Mod el Phases during Adopt ion Behaviors of Fair Trade Products, Sampedro [24] This model was designed by Fernando Sampedro, De- partment of Economics and Business Administration, University of Valladolid, Spain. It is based on Bañeguil’s and Chamorro’s model of ecological consumer shopping behavior. To deepen the role of the factors that influence the de- cision process to consume fair trade products, Sampedro (2003) [24] created a model of stages of awareness ap- plicable to the consumption decision process of fair trade products, which is based on the existence of different levels of social awareness. The author suggests that the transition from one stage to another requires overcoming some inhibiting factors (see Figure 5). To clarify the proposed model, the author utilized in- depth interviews with several groups working in the field of fair trade in the city of Valladolid these were: Engi- neers Without Borders-Castilla y Leo n, Intermon- Oxfam, and Sodepaz-Castilla and Leon. They also surveyed a sample of 111 individuals in the city of Valladolid. This included 59 consumers of fair trade products and 52 con- sumers who had never purchased fair trade products. Following is an explanation of each of the phases that comprise this model. 1) Social disinterest. Individuals who are at this stage believe they should do nothing to solve the underdevel- opment of the Third World. These individuals have a low degree of personal involvement on this issue. 2) Social attitude. The author mentions that people with positive social attitude are those who have consid- ered taking action to address underdevelopment and there- fore believe that they are part of the solution. 3 ) Ethical behavior. Individuals found at this stage are Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB 253 Figure 5. Stages of awareness model for the consumption decision process of fair trade pr oducts. those who sporadically purchase fair trade products and do it to feel socially responsible about th eir consumption behavior. 4) Social commitment behavior. In this phase one finds individuals who purchase fair trade products are truly committed and take responsibility for their social action role. Inhibiting Factors According to the author, in this model for an individ- ual to move from the disinterest stage or from the first stage to the next, it is necessary for the individual to face an inhibiting factor called indifferenc e. Indifference. While in developed countries now exist greater concern about the situation of third world coun- tries, there is still a large majority of individuals that do not considered this situation to be a problem and are not concerned. This indifference blocks the way towards a more positive social attitude. Thus, the absence of social and ecological values of these individuals is reflected by the low importance given to the purchase decision of fair trade products (Sampedro [24]). Therefore the resear- cher infers that these individuals do not look at the origin of the product and are less willing to buy fair trade prod- ucts or to pay more for such products and are not even interested in knowing where one can purchase such pro- ducts. Once an individual reaches the indifference attitude stage other factors that will prevent progress to the next stage will be encountered: 1) Ignorance. As long as individuals have less knowl- edge about international trade, the causes of underdevel- opment, and the impact the purchase of certain products may have to help solve the problem of underdevelopment, the less they may consider taking action to resolve this situation. The knowledge of what is fair for underdevel- oped countries, which forms of consumption are more friendly to them (that is to say the impact of consumption and trade on poor countries), Sampedro considers this ignorance a factor that positively influences the predis- position of individuals to purchase fair trade products and perhaps even pay more for them. 2) Perceived low effectiveness. The ability that an in- dividual thinks he or she has to solve a problem deter- mines the decision to try these products. If the person believes it can do little to solve the problem the person may feel powerless and this may interfere with the inten - tion to act. Furthermore, if the individual is not con- vinced that fair trade is effective as a tool for develop- ment the individual will be unwilling to purchase fair trade pro d uc ts. 3) Skepticism. If the consumer has doubts about the veracity of the social responsibility of fair trade prod ucts the purchase of such products will be difficult. This can happen because the individual may intuit that social re- sponsibility is less than or equal to that of other products. As a result of his research, Sampedro considers these factors to be inhibitors to the development of committed behavior: 1) Lack of commitment. A weak commitment on the consumption of fair trade products can act as an inhibitor  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing 254 of committed behavior (Sampedro [24]). The author mentions that if the individual belongs to social organi- zations it would be easier for such a person to turn their social responsibility to the consumption of ethical prod- ucts. 2) Infidelity. When an individu al has a lower degree of social awareness he/she infrequently purchases fair trade products and alternates purchases with other types of produ cts. The more aw areness th e consumer has , the less the purchases of low social responsibility products will be. 3) Unfavorable valuation of the attributes of fair trade products. In this section, the researcher suggests that if consumers make a comparison of fair trade products with other products and find they are worse, they will not purchase them even if these products guarantee greater social responsibility. From the model proposed by Sampedro [24] one may conclude that the consumption behavior of fair trade products is mainly explained by variables related to the level of commitment, the knowledge of social responsi- bility initiatives, and the social and ecological values of the individual, and not as much as to the characteristics of the products or the usual socio-demographic variables. 3. Results and Analysis In the models of Prochaska, DiClemente and Norcross [10], Kotler and Andreasen (1991), and Leal [1], the au- thors focus on behavior change in general, which is one of the main objectives of social marketing. Prochaska, Di Clemente and Norcross initiated behavior change studies in 1983 and are considered the fathers of behavior chan- ge models. Bañeguil and Chamorro [16], proposed a mo- del that focuses on purchasing behavior particularly in the area of organic products. Sampedro [24], mentioned by Bañeguil and Chamorro, proposes a model of behav- ior for the purchase of fair trade products. As a result of conducting a state-of-the-art literature review we fou nd a total of 5 models, which are illustrated and compared in Table 2. 4. Conclusions If we analyze the five models presented in Table 2 we can observe that for individuals in process of behavior change a set of sequential stages have to be followed. In other words, individuals have to go through each of the stages and cannot leap from the first to the last stage. We must point out that all models have equivalent phases regardless of the name ascribed to them by their authors. Following is a summary of the characteristics presented by individuals passing through each of these stages. In the first phase, all the authors mentioned in this study agree that individuals do not even consider that the behavior is appropriate for them. They believe they should not do anything to change. In the second stage, individuals are becoming aware of a change in attitude, they are thinking and starting to be concern that a prob- lem exists and that it must be solved. In the third phase, the individuals finally decide to personally act to solve the problem. In the fourth stage, individuals perform the behavior for the first time, that is, they decide to take real steps to fix the problem. Finally, in the last stage the authors agree that indi- viduals are already committed in the conduct and prac- tice of the behavior as part of their habits and have no desire to return to previous behaviors. Let us not forget that in these models the authors are attempting behavior modification with a high degree of involvement, not spontaneously, but in a gradual way through distinct and clearly defined phases and as we observed, all the models take the individual through distinct and clearly define phases. Derived from the research, we found that there is very little information about the purchasing behavior of Mexican consumers specifically related to fair trade pro- ducts. The state of the art literature review revealed a single stage model of awareness in the purchasing be- havior of fair trade products and it was developed in Spain. Therefore, there are areas of opportunity for Mexican researchers to explore and get to know the be- havior of domestic consumers of fair trade products. Table 2. Synthesis of models and phases. Models Spiral model of phases of change Prochaska, DiClemente and Norcross [10] Kotler and Andr easen model [15] Leal’s model of the behavior change process [1] Shopping behavior model of the ecological consummer Bañeguil and Chamorr o [ 16] Awareness model for the comsumption decision process of fair trade products Sampedro [24] Precontemplation Precontemplation Observation Carelessness Disinterest Contemplation Contemplation Analysis Concern Preparation Attitude Attitude Action Action Behacior Action decision Behavior Phases Confirmation Maintenance Affirmation Real action Commitment Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB  Explanatory Models of Change of Consumer Behavior Applied to Social Marketing 255 Our conclusion is that the most compressive model to understand the behavior of consumers in fair trade has five phases which are: disinterest, concern, attitude, ac- tion, and commitment behavior. REFERENCES [1] A. Leal, “Gestión del Marketing Social,” McGraw Hill Interamericana de España., Valencia, 2000. [2] K. Glanz and B. Rimer, “Theory at a Glance: A Guide for the Practice of Health Promotion in the Paper Documents Playing Series #19, Models and Theories of Health Com- munication. Health Promotion,” Washington DC, 1996. [3] J. Prochaska and C. DiClemente, “Stages and Processes of Self-Change of Smoking: Toward an Integrative Model of Change,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol- ogy, Vol. 51, No. 3, 1983, pp. 390-395. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390 [4] G. Cabrera, J. Tascón and D. Lucumí, “Health Beliefs, History, and Contributions to the Model Constructs. Na- tional School of Public Health,” Facultad Nacional de Salud Pública, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2001, pp. 91-101. [5] J. Bettman, “An Information Processing Theory of Con- sumer Choice,” Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Florida, 1979. [6] A. Bandura, “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change,” Psychological Review, Vol. 84, No. 2, 1977, pp. 191-215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [7] J. Rothman, “Planning and Organizing for Social Change: Action Principles from Social Science Research,” Colu- mbia University Press, New York, 1974. [8] E. Rogers, “Diffusion of Innovations,” Free Press, New York, 1995. [9] A. R. Andreasen, “Marketing Social Change: Changing Behavior to Promote Health, Social Development, and the Environment,” Jossey Bass, San Francisco, 1995. [10] J. Prochaska, C. Di Clemente and J. Norcross, “In Search of How People Change: Applications to Addictive Be- haviors,” American Psychologist, Vol. 47, No. 9, 1992, pp. 1102-1114. [11] J. Prochaska, “Common Processes of Change in Smoking, Weight Control, and Psychological Distress,” In: S. Shiff- man and T. Wills, Eds., Coping and Substance Abuse, Columbus O. Ross Labs, Columbus, 1985, pp. 345-363. [12] J. Prochaska and A. Costa, “A Cross-Sectional Compari- son of Stages of Change for Pre-Therapy and Within- Therapy Clients,” University of Rhode Island, Kingston, 1989. [13] C. DiClemente, J. Prochaska, S. Fairhurst, W. Velicer, M. Velasquez and J. Rossi, “The Process of Smoking Cessa- tion: An Analysis of Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Preparation Stages of Change,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 59, No. 2, 1991, pp. 295- 304. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.295 [14] J. Prochaska, J. Norcross, J. Fowler, M. Follick and D. Abrams, “Attendance and Outcome in a Work-Site Weight Control Program: Processes and Stages of Change as Pro- cess and Predictor Variables,” Addictive Behaviors, Vol. 17, No. 1, 1992, pp. 35-45. doi:10.1016/0306-4603(92)90051-V [15] T. Bañeguil and A. Chamorro, “Buying Behavior of Or- ganic Products: A Proposed Model,” Consumption Stud- ies, Vol. 62, 2002, pp. 49-61. [16] P. Kotler and A. Andreasen, “Strategic Marketing for NonProfit Organizations,” Prentice Hall, New York, 1991. [17] J. Calomarde, “Geen Marketing,” Ediciones Pirámide y ESIC, Madrid, 2000. [18] D. Fuller, “Sustainable Marketing: Managerial-Ecological Issues,” SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, 1999. [19] S. Kalafatis, M. Pollard, R. East and M. Tsogas, “Green Marketing and Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior: A Cross-Market Examination,” Journal of Consumer Mar- keting, Vol. 16, No. 5, 1999, pp. 441-460. doi:10.1108/07363769910289550 [20] J. Noya, C. Gómez and A. Paniagua, “The Inconsistency of Attitudes toward the Environment in Spain,” In: M. Pardo, Ed., Sociology and the Environment: State of Af- fairs, Universidad Pública de Navarra., España, 1999. [21] B. Schlegelmilch, G. Borlen and A. Diamantopoulos, “The Link between Green Purchasing Decisions and Measures of Environmental Consciousness,” European Journal of Ting, Vol. 30, No. 5, 1996, pp. 35-55. [22] L. Philips, “Green Attitude,” American Demographics, Vol. 21, No. 4, 1999, pp. 46-47. [23] Fundación Entorno, “Advance Findings: Consumer Hab- its and Environment in Spain,” 2000. http://www.fundacionentorno.org [24] F. Sampedro, “Determinants of Ethical Consumption,” 2003. http://webs.uvigo.es/consumoetico/textos/archivos_pdf/co nsumoetico.pdf Copyright © 2012 SciRes. IB

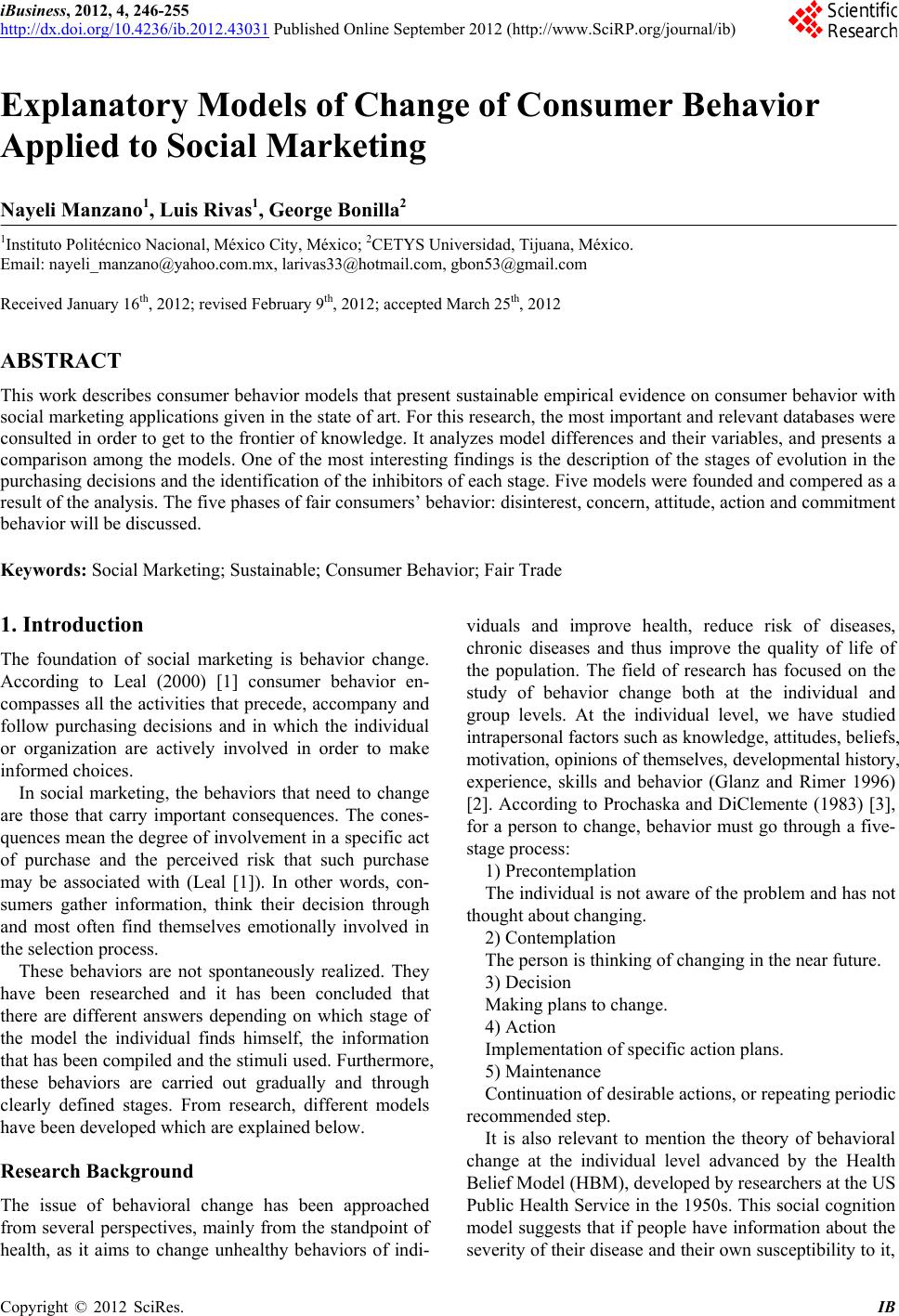

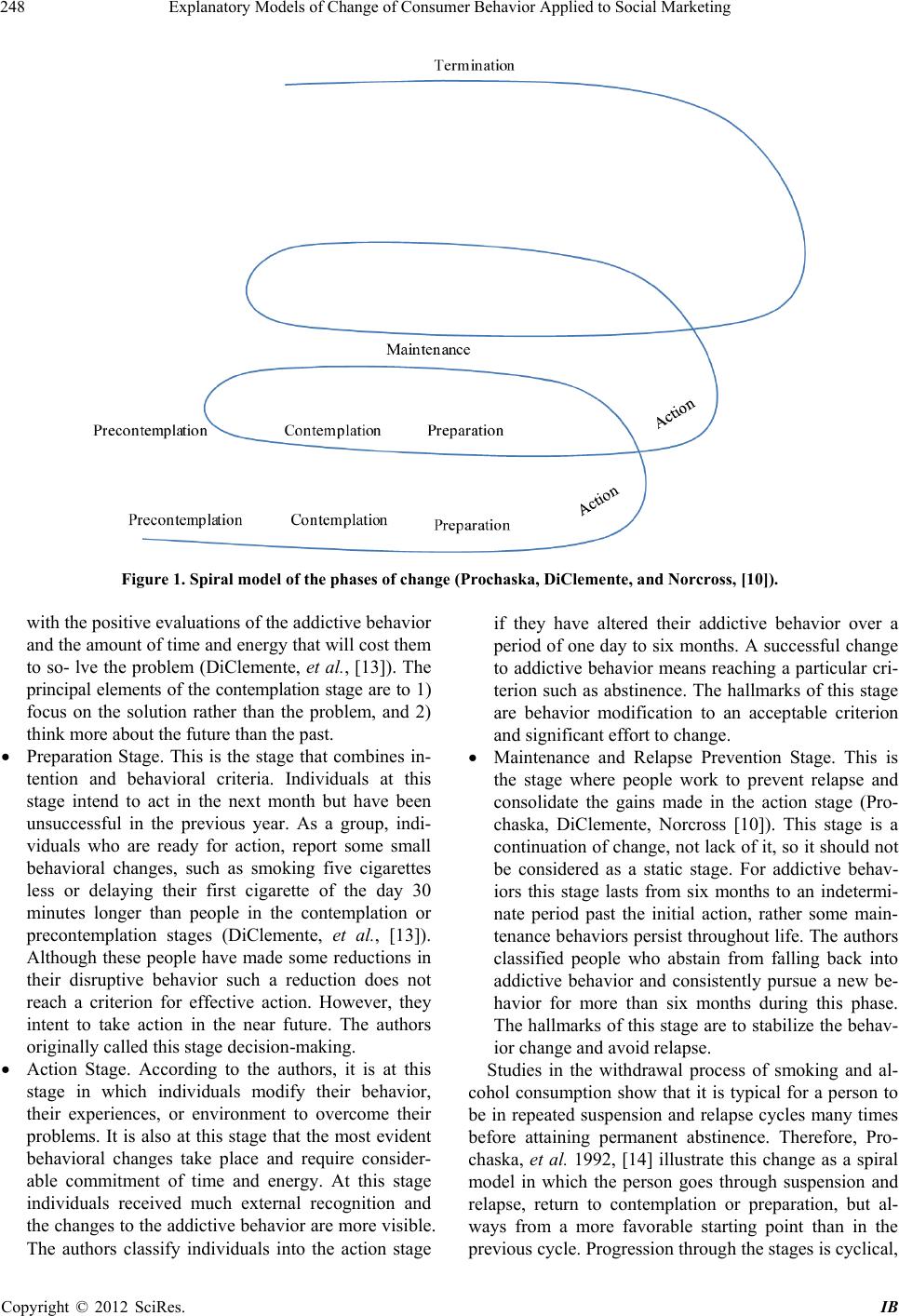

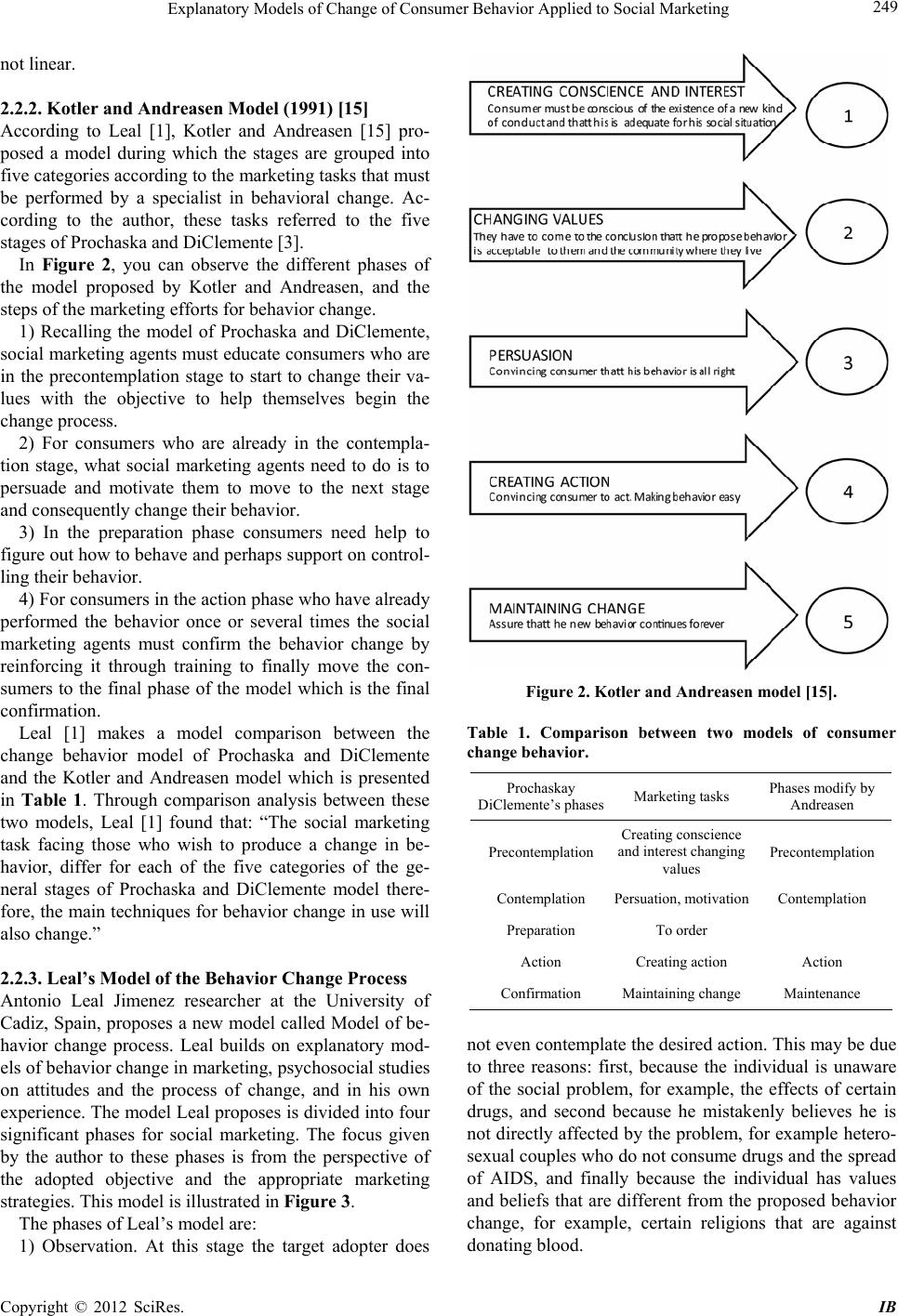

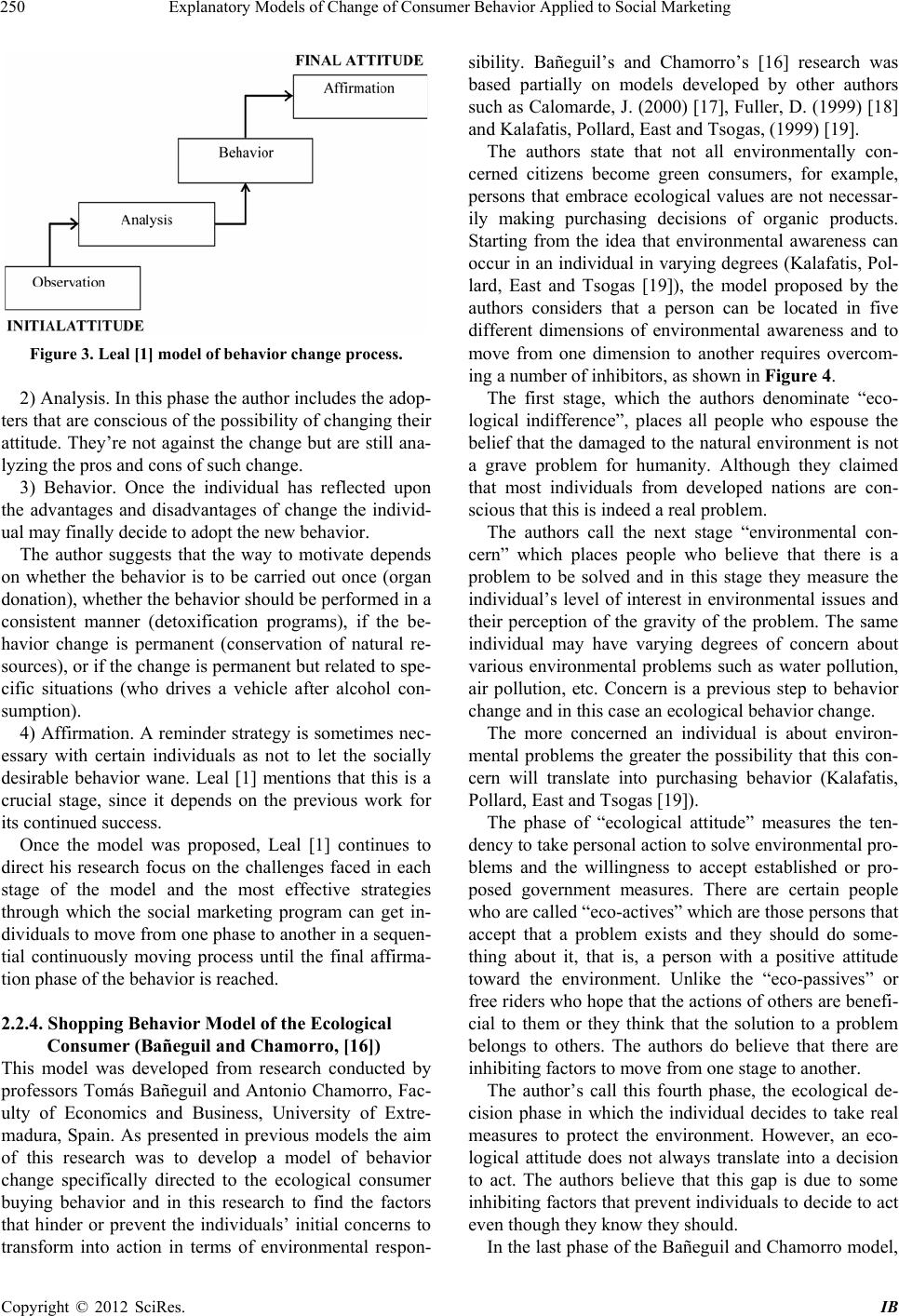

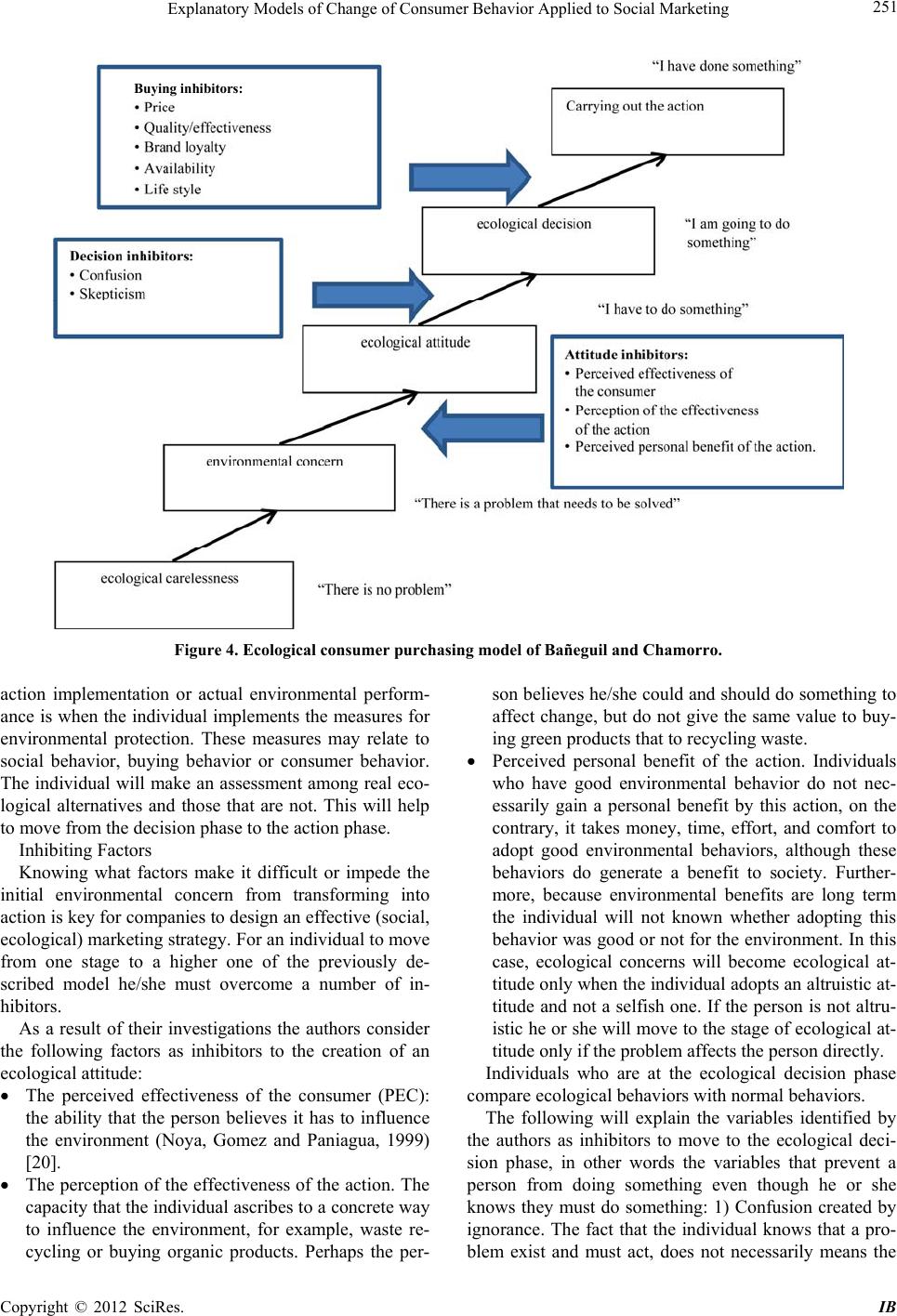

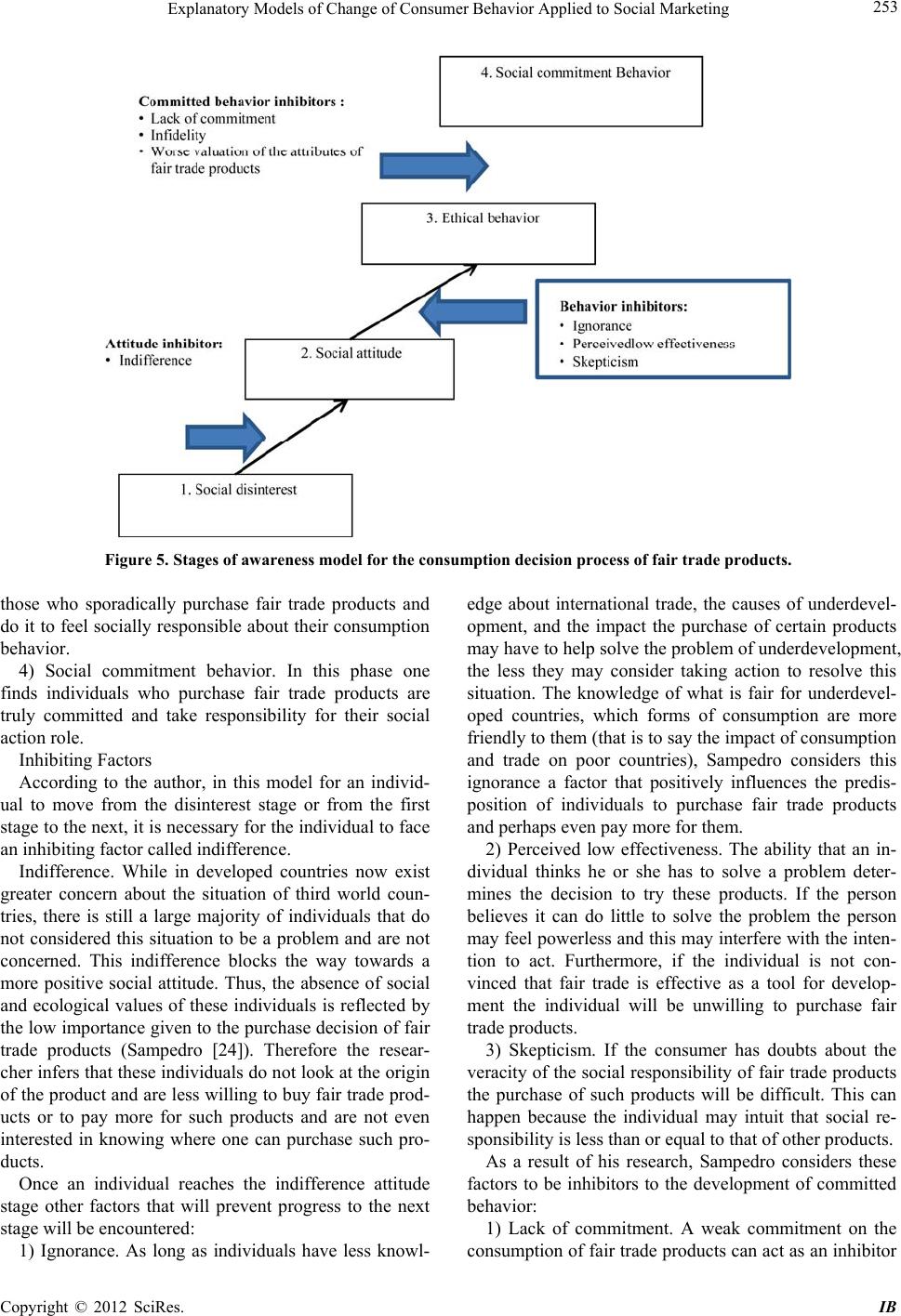

|