Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.08 No.14(2018), Article ID:88172,29 pages

10.4236/tel.2018.814200

Cocoa Exports of Cameroon: Structure and Mechanism of Operation

Ze Engamba Herve, Guiyu Zhao

College of Economics and Management, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China

Copyright © 2018 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: September 12, 2018; Accepted: October 27, 2018; Published: October 30, 2018

ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to study the cocoa market in Cameroon over the period 2000 to 2016. The study consisted in presenting in a general way the organization, structure and operating mechanisms of the Cameroon cocoa market, particularly the value chains from family farmers to final consumers through exports; it also allowed us to highlight some issues and prospects for reviving the cocoa sector in Cameroon. It shows that Cameroon, like most cocoa-producing countries, also faces many difficulties not only externally, but also because of the international environment (the volatility of the prices of export products), internally through implemented policy measures, their consistency and phasing, as well as their deadlines. Starting from the liberalization of the sector in the early 1990s to the devaluation of the CFA franc in January 1994, a relative stagnation of the country’s agricultural performance has been noted so far. The problem is therefore not only institutional and structural but also cyclical. With regard to domestic marketing, the government’s option of a return to stabilization will reaffirm the place and the role of the State in the management of the sector. As far as external marketing is concerned, to remedy this, the government option consists of setting up a state-controlled advanced sale system through the centralization of sales and the monitoring of their quantitative execution. However, for a development of Cameroon’s artisanal, semi-industrial and industrial cocoa processing industry, we need strong support and protection of the local industry in order to attract foreign investors and encourage local initiatives, with accompanying measures that make cocoa processing more profitable in Cameroon as in other producing countries.

Keywords:

Exports, International Market, Cocoa, Cameroon

1. Introduction

Starting from the premise that generalized free trade can only enhance growth and participate in poverty reduction, part of the economic literature on international trade advocates liberalizing all trade. One of the limitations of this literature lies in the priority it places on competition between developing and industrialized economies, often focusing on the problem of distortions of competition caused by agricultural policies. In fact, developing countries are not exposed solely to competition from the North, especially in commodity markets such as coffee and cocoa. The growth of South to South trade masks a recomposition of the commercial performances of each of these economies. The comparative advantages acquired in the past and which had crystallized for a time the market shares held by the southern countries which produced raw materials, are wavering under the weight of new competitors. The structure of the world supply of coffee and cocoa is a good illustration of this change (Anna L and Thierry P, 2008) [1] .

Often considered as inseparable (Cocoa and Coffee), cultivated in the same zones (tropical zone in general), cocoa is mainly traded on the commodity exchanges of London and New York. Subject to rumors or anticipations of stock outs, poor harvest, weather or political events, the market is very volatile and speculative; price changes can be very important. However, prices have tended to decline since the early 1980s under the double effect of excess supply and large stocks held by consuming countries. In the 1980s, these countries took advantage of falling prices to build considerable reserves used to regulate the market in their favor. Producer countries are not able to build stocks for their benefit; they remain subject to the global market (Atlas et al., 2007) [2] .

A panoramic view of supply and demand shows that the global cocoa supply is highly dependent on African, South American and now Asian countries. The supply is abundant, often leading to a supply-demand imbalance (confers a law of supply and demand of J.B. Say), causing a structural weakening of prices prejudicial to most producers. Indeed, world cocoa production since the 20th century has been growing at a rate of around 2% to 2.5% and reached 1.5 million tonnes in 1964. Today, it exceeds 2 million tonnes, of which Africa alone accounts for nearly 66% (Mossu, 1990). The major producing countries are: Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Indonesia, Cameroon and Nigeria (FAO et al., 2007).

Total world production comes from three production basins: The Gulf of Guinea (Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, etc.), with total production hovering around 70%; South America, Central America and the Caribbean (Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, etc.), with total output hovering around 16%; South Asia and Oceania (Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, etc.) with total production around 18% (FAO, 2017) [3] .

As for the country importing cocoa beans, the main actors are: The United States, the EU, the United Kingdom, the Russian Federation (ICCO et al., 2007) and China, which is recently positioning itself more and more like a future Eldorado of this market by 2050. These countries import about 3 million tons of cocoa each year (Wikipedia, 2009) [4] .

From the historical point of view, the Cameroonian cocoa market has undergone several changes, starting after Independence of the country (1960).

Indeed, from 1980 to 2000, cocoa and coffee exports accounted for nearly 28% of the GDP of non-oil products and 40% of primary sector exports generated around 110 billion CFA francs/year, distributed to producers (INS COMEX, 2005) [5] .

From 2005 to 2010, these exports increased from 180,000 to 227,000 tonnes, an increase of 47,000 tonnes in absolute value and 20.6% in relative value. In addition to this growth is the good behavior of international market prices, which can explain the significant change in their FOB (Free On Board) value, which rose from 116.5 billion FCFA in 2005 to 312.3 billion FCFA in 2010, an increase of 195.8 billion CFA francs in absolute value and 168% in relative value (INS, 2009). Despite the uncertainties and risks faced by producers facing this highly volatile market, the forecasts of international organizations, with regard to price developments on the international markets for cocoa and coffee, are encouraging over the next few years. In view of the average growth rate of 3% in traditional markets and optimistic forecasts for growth in consumption in the emerging markets of the Middle East, Asia and the non-traditional markets that are the producing countries (ONCC, 2011) [6] .

The economic crisis of the 1980s, which resulted, among other things, in the drastic drop in prices of agricultural raw materials since 1986 and in the State’s incapacity, through the National Office for the Marketing of Commodities (ONCPB), to further support the prices to the planters, led to a reform of the sectors under the guidance of the donors. Indeed, the Cameroonian economy was an administered economy, largely marked by the presence of the state as the main actor, provider of wealth and jobs (increased interventionism of the state in economic activity). The crisis of the middle 1980s led to the implementation of the Structural Adjustment Policies (SAPs) instituted and imposed by the Bretton Wood institutions in developing countries, largely resulting in a strong liberalization of the Cameroonian economy. The cocoa and coffee sectors also suffered from these liberal reforms. One of the consequences of these reforms was the commitment of the State as a major economic actor. Indeed, the dissolution of the ONCPB in 1991 by the creation of the ONCC or National Office of Cocoa and Coffee (secular branch of the State) and the CICC or Interprofessional Council of Coffee and Cocoa (consultation structure of private operators), the liberalization and deregulation of marketing with the consequent elimination of stabilization and the easing of conditions for access to the export profession the privatization of export quality control and devaluation of the FCFA in January 1994 are perfect illustrations of the restructuring of these sectors [7] .

Despite the expected effects of these measures (liberalization) and the devaluation of the CFA franc in 1994, it is clear that the objectives have not been achieved in particular: the local processing of cocoa (through industrialization); optimizing the competitiveness of products; the qualitative and quantitative improvement of production; transparency in commercial transactions, improvement of the Cameroon label in the world cocoa supply market (PRDFCC, 2014). Hence, the interest and the socio-economic stake in the cocoa sector. The purpose of this paper is to present in a general way the structure and operating mechanisms of cocoa exports in Cameroon from family farmers to consumers; It also provides an answer on the perception of Cameroonian cocoa in the international market and its impact (perception) on cocoa export earnings in the economy [8] .

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the adopted methodology; Section 3 presents the organization, structure and operating mechanisms of the sector; Section 4 highlights the prospects of reviving the sector in Cameroon; finally, Section 5 will allow us to conclude and propose some solutions for economic policy.

2. Methodology

The study focuses on the cocoa market in Cameroon over the period 2000 to 2016. Its objective is to present in a general way, the organization, the structure and the mechanisms of the functioning of the Cameroonian cocoa market, notably the starting value chain from family farmers to consumers to exports; finally, it will allow us to highlight some prospects for reviving the cocoa sector in Cameroon. The approach is simply to take stock of the current situation of the cocoa market in Cameroon, notably on the issues related to cocoa exports of Cameroon origin and to provide some solutions to the many difficulties faced by Cameroon. For this purpose, a thorough literature search on the subject was done both theoretically and for data collection to strengthen our analysis. However, in this study we did not carry out a field survey near the producers and professionals of the sector to better understand its operationalization. On the other hand, it may be completed in the future by other much more in-depth work. The collection of information is divided into two parts: Statistical data: diagrams 2 and 3 are from UNCTAD in 2008; Chart 1 on the evolution of average prices to farmers comes from data collected at faostat and oncc of Cameroon. The literature presented here is the result of extensive documentation of the various reports of the ICCO, the World Bank and the Cameroonian NSI since the early 2000s.

3. Organization and Stakeholders in the Sector

With regard to the organization and the actors of the sector, the production is made by small farmers and more or less structured organizations like cooperatives or large groups (large plantations). Indeed, the commercial cocoa resulting from the work of local producers or craftsmen is introduced into marketing channels whose number of actors has greatly increased since the liberalization of the sectors. The most numerous license holders, accredited by local control bodies, act as intermediaries to supply exporters. Today, major exporters are investing in purchasing systems closer to producers at the expense of smaller players. This system also affects patented local exporters who are very numerous at first sight see for the most fragile their market shares shrink and disappear. These major exporters are also playing an increasing role in the transformation of market cocoa into manufactured products in the producing countries. They provide raw material, liqueur, butter, powder, the industry of the consuming countries or put on the local or regional markets of the chocolate products. Three major multinational groups dominate this market: ADM Cocoa, Cargill and Barry Callebaut. They are present in West African producing countries alongside other actors whose importance varies from country to country. The bulk of cocoa goes, in the form of market cocoa or semi-finished products, to the major consuming countries. After landing in the ports, the cocoa, which can remain stored in the form of beans about 3 years or more, is redirected towards the industrialists and manufacturers who directly manufacture finished products or products (cover) intended for the industries and craftsmen of the chocolate factory and biscuits that have not invested in the direct treatment of cocoa beans.

With respect to local stakeholders in the industry, historical developments indicate that several changes have been made over time. These can be subdivided into two main periods. That of the pre-crisis period in the mid-1980s and the post-1990 period. Indeed, the Cameroonian economy was an administered economy, largely marked by the presence of the state as the main actor, provider of wealth and wealth jobs (increased state interventionism in economic activity). The cocoa and coffee sectors are under the supervision of the ONCPB (National Office for the Marketing of Commodities), the regulatory body for these sectors. However, the crisis of the mid-1980s led to the implementation of structural adjustment policies instituted and imposed by the Bretton Wood institutions in developing countries. This largely translated into the concept of a market economy theorized by classical and neoclassical economists. This has mainly resulted in a strong liberalization of the cocoa and coffee sector in Cameroon since 1991. To this end, the State has been replaced by two structures namely: the ONCC or National Office of Cocoa and Coffee (secular arm of the State) and the CICC or Interprofessional Council of Coffee and Cocoa (structure of concertation of the private operators). However, various other local structures and international organizations are actively involved in the deployment of the Cocoa and Coffee sectors [9] .

• FODECC―Cocoa and Coffee Sector Development Fund

To increase the efficiency of the cocoa and coffee sectors, the Fund for Development of the Cocoa and Coffee Value Chain (FODECC) was created in March 2006 by Presidential Decree No. 2006/085 of 9 March 2006 on the organization and operation of the Development Fund. Its main mission is to support this sector through the financing of projects aimed at securing, increasing and guaranteeing the good quality of cocoa and coffee production.

• Companies under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture

In fact, the State is carrying out a series of actions in these main production areas with the aim of: improving the economic and social well-being of small producers and contributing to the sustainable management of basin ecosystems of production.

• Technical unit for monitoring and coordinating the cocoa and coffee sectors

At the level of the Prime Minister’s Services, a technical unit for monitoring and coordinating the cocoa and coffee sectors has been created to ensure the coordination and transparency of the various operations in these sectors.

• Other local stakeholders

Approved buyers

Producer associations

Association of Cocoa and Coffee Exporters (AECC)

Trade Union of Manufacturers and Buyers of Cocoa and Coffee of Cameroon (SUACC) [10] .

3.1. Structure and Mechanism of Operation

The removal of government support measures has led to the disorganization of the sector and in particular the increase in the number of private actors throughout the chain, causing a decline in quality and production volumes (Graph 1).

• Regulatory bodies

These bodies have, statutorily, the responsibility for a part of the regulation of cocoa farming.

1) The regulation of production: The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MIDADER).

It is in charge of the cocoa production component. This organ is involved in the control of cocoa production from seed to fermentation. To this end, MINADER carries out extension activities and agricultural advice. MINADER deploys extension managers in the production areas who are in charge of raising producers’ awareness of good agricultural practices.

2) Regulation of marketing: The National Office of Coffee and Cocoa (ONCC).

This body is in charge of the export quality control component of Cameroon. As such, its agents make technical visits to the facilities of approved quality control agencies, factories and storage facilities for approval. The ONCC also has a role of promoting the brand image of origin Cameroon on cocoa.

The ONCC also provides the link with the various stakeholders in the sectors (exporters, manufacturers, forwarding agents, quality control companies) including the Inter professional sector and collects information on many aspects (purchase prices, planters, market calendars. Names of active exporters in the field, denunciation of bad practices of certain exporters).

• The Inter professional council of coffee and cocoa (CICC)

The purpose of this body is to provide all the professional bodies constituting the various colleges represented at its general assembly with any assistance

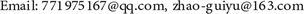

Graph 1. Cocoa sector in Cameroon.

and/or services to increase the efficiency of the entire sector. The CICC has within it: a college of producers-national association of coffee and cocoa producers (GIC, UGIC, federation, confederation); the college of machineries; the college of exporters; the college of transformers.

Regarding the processing of cocoa, part of Cameroon’s cocoa is processed locally, but about 90% of the cocoa is exported to Europe, particularly to the Netherlands, as a raw material for chocolate makers and the chocolate industry. confectionery. The three biggest buyers of Cameroonian cocoa are: ADM (Archer Daniels Midland), Cargill and Barry Callebaut. Today, a majority of local processing companies are subsidiaries of large multinationals in the global cocoa trade.

• Agricultural professional organizations (OPA)

For two decades, sub-Saharan African states have disengaged themselves by unilaterally transferring responsibilities to professional agricultural organizations (OPA), also known as OP.

The coxeurs are illegal buyers and help to disrupt the marketing of cocoa in Cameroon. The coxeurs are collectors and touts operating directly from the producers in the bush. They buy the cocoa and coffee in the villages face to face with the farmers, edge field, often deceiving them (on the quantity and the quality) but paying them immediately.

3.2. Vertical Integration and Horizontal Concentration

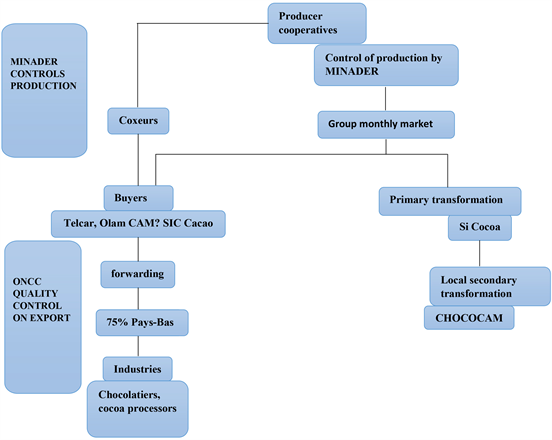

Graph 2 representing the cocoa supply chain above shows that there have been important changes in the chain structure, both in the cocoa producing countries

Graph 2. Cocoa supply chain. Source: UNCTAD Secretariat, 2008.

and in the consuming countries (cocoa importers). In this sub-section, we will first examine the structural changes originally made, referring specifically to the case of Cameroon, and then the restructuring processes outside the producing countries. The structural configuration of the chain largely determines the bargaining power of the various actors in the supply chain, and therefore deserves a detailed examination.

The relationship between concentration, competition and efficiency is complex, in the cocoa and chocolate sector as elsewhere. The phenomenon of concentration is assessed here by reference to aggregated industry classifications and market shares.

As for the other cocoa producing countries, a distinction must be made between production and marketing. Production is centered around farmers. At the end of the 1990s, almost 90% of world cocoa production came from small farms with less than five hectares. The number of cocoa farmers in the world was estimated at about 14 million, three quarters (75%) in Africa. In Cameroon, it is estimated that 400,000 hectares of land are dedicated to cocoa cultivation, with a production structure characterized by the predominance of small producers (at the end of the 1990s, there were over 1.6 million small cocoa farmers); between 2000 and 2005, the yield per hectare averaged 370 kilograms per hectare. It is estimated that in 2002, only 10% of cocoa (and coffee) growers were organized into producer associations, mainly through Joint Initiative Groups (JICs), which is also their share of trade cocoa. These growers are mainly engaged in harvesting, fermenting, drying, bagging and sometimes transporting cocoa beans to delivery points in the interior of the country. At these stages of production, the cost of labor (often family) and material inputs (fertilizers, insecticides and fungicides) are by far the main cost components. With regard to the marketing of cocoa, the local marketing chain (until the boarding of cocoa aboard the ship) goes from farmers to international buyers, with two intermediate stages. The first step involves collecting at the local level―at or near the farm―and delivery to the export port (domestic marketing). The second stage is export shipping (external marketing). A simplified version of the marketing chain is illustrated below, in the specific case of Cameroon [11] (Graph 3).

Domestic marketing is carried out by producer organizations, local traders operating on their own behalf or agents of the exporters or the local processor. Exporters, independent buyers and their agents must have signed a declaration of commercial activity and hold a professional card issued by the Inter professional Council for Cocoa and Coffee (CICC). The main activities include the collection and processing of cocoa beans on the spot and their transportation to the port.

The domestic marketing chain is often characterized, as indicated below, by some fragmentation, depending on the marketing channels prevailing in a given region:

Farmers bring their produce to the warehouse of the producer organization to which they belong so that it can be transported to the exporters’ warehouses.

An exporter is a local purchasing organization (with its own employees) and buys directly from producers, from the farm itself or close to it (purchase originally). There is also direct trading when large exporters and processors use agents to buy cocoa directly from producers or from village markets for delivery to buyers’ warehouses.

Self-employed people―usually traders who often have other activities―procure small amounts of cocoa from several subsidiary collectors (or “local collectors”, who are often themselves cocoa farmers), or directly from producers, in order to make a larger batch for the exporter.

At the regulatory level, initial purchases must be made in the context of organized markets, at the initiative of the producers and their groupings and in liaison with the buyers and the competent administrative authorities. Door-to-door or overnight cocoa purchases are prohibited. The purpose of all these requirements was to strengthen the relative bargaining power of producers near buyers [12] .

In practice, farmers, including individual producers, often sell directly to local traders or agents of the exporter. These traders buy directly from or near the farm and transport the product to the exporter’s purchase points (on-site warehouses) in the cocoa production areas. From there, the cocoa is transferred to the exporter’s warehouses at the point of export (the port of Douala).Low quality (residual) beans unfit for export are sold at reduced prices to the agents of the local processing company.

External marketing is provided by exporters, or freight forwarders. The export of cocoa beans is reserved for operators who have signed a declaration of commercial activity and who hold a business card issued by the CICC. Exporters buy from cooperatives, other middlemen and even producers and sell to international

Graph 3. Internal marketing structures―Cameroon.

buyers (often affiliates). They are responsible for all operations specific to export transactions (physical handling at the port, customs clearance, export packaging, phytosanitary treatment, and other obligations imposed by the exporting country and the importing country or negotiated under the contract export sales). In most cases, these functions are provided through a network of service providers. Cocoa transport and related formalities are handled by a “freight forwarder” acting on behalf of an exporter who handles all shipping and insurance formalities and documents for the goods. An “aconite” takes care of loading the cargo on the ship. Quality control is provided by approved companies. The exporter plays a central role in this whole network of services.

Traditionally, the first clients for cocoa in the export markets were importers who bought the cocoa for their own account, then sold it to manufacturers (cocoa processors and chocolate manufacturers). Gradually, the boundaries between traders and industrial users in this sector have faded. Large processors and manufacturers are now also the main international buyers of cocoa in export markets. In addition, as we will see below, these buyers have integrated vertically upstream, by taking up some extent the export activities in the countries of origin.

In the case of cocoa, financial flows and physical flows operate in the opposite direction: exporters generally provide credit to intermediaries, who use the funds to pay collectors and growers.

1) Arrêté no 00026/MINCOMMERCE du 12 août 2005, art. 6.

2) Ibid.

Liberalization of the cocoa sector in West and Central Africa has led to further concentration in the export sector, with a tendency for traders and foreign manufacturers to operate, either directly or through proxies.

During the first years of liberalization, a large number of extremely fragmented local traders (local buyers and exporters) were involved, sometimes leading to a temporary increase in producer prices. However, the sector has been rapidly consolidating as many of these traders have been squeezed out by fierce competition. With respect to external marketing, a small number of large private exporters have gradually dominated export markets. In Cameroon, more than 60% of exports reported between August 2006 and July 2007 had been made by the four largest exporters (in terms of tonnage shipped). The largest exporter alone accounted for about 29% of shipments during this period. As far as cocoa supply is concerned, exporters are involved in the entire chain from production to export. In countries of origin, producers have little bargaining power over these large traders who, directly or through contracts with agents, buy as close as possible to the source of production [13] .

This process of horizontal concentration has been accompanied by a tendency for traders and foreign manufacturers to move vertically upstream to the point of origin. As in other cocoa producing countries, in Cameroon the main local processing and export companies are now subsidiaries, or close partners, of multinationals active in the cocoa sector worldwide. For example, the Cameroonian cocoa processing company SA, known as SIC cocoa, was owned (99.95% at 31 August 2006) by Barry Callebaut, a leading Swiss cocoa processing and chocolate manufacturing company. The American company Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) has acquired―with the company Olam registered in Singapore―Usicam, one of the largest facilities for drying, cleaning and storage of cocoa and other related activities in Cameroon. ADM is, together with the company Cargill (also present in Cameroon for the supply of cocoa and the corresponding logistics), a major trader and processor of cocoa in the international market. The country of destination of more than 77% of the consignments declared for export between August 2006 and July 2007 was the Netherlands, which is also explained by the presence on the spot, in Cameroon, of multinational companies (Cargill and ADM in particular) which have their main processing facilities in the Netherlands. Other multinational trading companies―including Olam and ED & Man―have also established a local presence in Cameroon. And factual relationships of dependence and control are added to these formal links between companies. In particular, a number of local exporters that are not united by formal relationships with foreign firms are nevertheless dependent on them as sources of financing. In practical terms, these exporters act as freight forwarders by selling their FOB products to international buyers for whom they receive financing. The internalization of activities in the various segments of the cocoa value chain under the auspices of multinational companies makes a priori possible tacit or formal collusive behavior [14] .

This movement of concentration and integration of firms in the cocoa export sector in Africa is apparently driven by two factors. The first was access to finance, which put local exporters at a competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis foreign companies. With the liberalization of the sector, private commercial banks in producing countries have become reluctant to finance local operators in the cocoa sector and have tightened credit conditions. According to the statistics of the Professional Association of Banks and Financial Institutions of Côte d’Ivoire (APBEF-CI), for example, the total amount of credits for the cocoa and coffee season at the end of January 2000 (six months after liberalization of the cocoa sector) was CFA 133 billion, or an average of 9.5% of total loans granted by banks, well below the level of a few years earlier, which was close to 20%. Loans from these commercial banks had very high interest rates of 18 to 25 percent a year. Local exporters were therefore seeking to affiliate with foreign trading and processing companies from which they could receive credit at much lower interest rates (4% - 6% per annum). In fact, most multinational trading and processing companies have a strong financial rating and get most of their financial resources from institutional investors. For them, the cost of capital is very low (with an interest rate equal to the adjusted LIBOR rate plus a margin, depending on the company’s rating), compared to that which local traders have to pay [15] .

The second factor was the obvious economies of scale in cocoa transport logistics. In the 90s, bulk transport of cocoa beans developed in international trade. Cocoa beans are loaded into shipping containers (“containerized bulk”) or directly into the ship’s hold (also called “mega-bulk” method). In the early 2000s, it was thus transported in bulk between 800,000 and 900,000 tonnes of cocoa per year for Europe only. Bulk transport may be less expensive than conventional jute sacks in a proportion of not less than one-third, but the quantities involved require large cargoes, which is possible at the moment only for large companies. This development has resulted in significant cost savings, but it has also strengthened the competitive position of large multinationals. In addition to these important structural consequences, it is not excluded that bulk transport has had the unintended consequence of a decline in the quality of cocoa. In bulk transport, cocoa beans are simply dumped in containers. This type of transport involves storage in piles (rather than in bags) (i.e. beans are piled up on the warehouse floor) and other logistical operations specific to bulk (as it is for cereals, cocoa beans are unloaded from the ship’s hold and transported to the warehouse by hopper or conveyor belt). With all this, there can be a mix of cocoa of different origins and physical alterations. But attempts to revert to traditional jute bagging have met with strong opposition.

There has also been a strong concentration of structures for cocoa purchases at the international level. ADM, Cargill and Barry Callebaut are the main international buyers of Cameroonian cocoa in export markets. In 2003, these three companies would have bought 95% of Cameroon’s cocoa production. The emergence of this oligopsonistic structure for cocoa purchases is similar to the structural changes taking place at the international level [16] .

3.3. International Organization and Structure of the Industry

In consumer countries, the chocolate manufacturing sector and the chocolate consumption market have also undergone significant changes, which have implications for the structure of the cocoa market as a whole.

The patterns of vertical integration and de-integration, horizontal concentration and globalization of operations have undergone important structural changes at the international level in the following areas: International trade in cocoa beans and cocoa; Cocoa processing (processing of cocoa beans into cocoa mass/mass, cocoa butter and cocoa powder); Manufacture and marketing of couverture, or chocolate for industrial use (the raw material of food chocolate manufacturers); Manufacture and marketing of consumer chocolate; Retail sale of chocolate in consumer countries.

1) CNUCED, TD/B/COM.1/EM.10/2, cf. supra, note 25, p. 11.

Thus, the cocoa-chocolate sector is highly concentrated at various stages. In many (remote) areas, cocoa farmers face oligopsony or even monopsony situations. In consumer countries, concentration is becoming stronger in retail activities and as for markets for intermediate products (semi-finished products derived from cocoa and cover), they are generally characterized by an interaction between oligopsonistic and oligopolistic structures [17] .

3.4. Concentration, Competition and Efficiency

The above analysis of market structures is supplemented with information on price trends in the cocoa and chocolate industry. This section refers only to changes in prices and cost structures that can at least partly be observed in connection with the consolidation and restructuring of markets. But for lack of sufficient information an exhaustive factual analysis of costs and margins throughout the chain cannot be made. With regard to the purchase of cocoa, it has been seen above that liberalization had resulted in increased concentration in the export sector, since foreign trading and processing companies tended to integrate their upstream countries of origin. Oligopsonistic structures have emerged for cocoa purchases, both locally and internationally. Are these consolidations and restructuring schemes accompanied by significant price movements? The answer seems to lie in an analysis of price trends since liberalization: The share of producer prices, converted into dollars, relative to world prices; additional data on marketing costs and taxes; other factual elements (Figure 1).

A number of observations can be drawn from the relative movements of producer prices and world prices. Cocoa producers are most often victims of exogenous shocks due to the volatility of world prices. In fact, the cocoa market is mainly characterized by a strong fluctuation of prices, which results in the speculative behavior of the producers pushing them to adopt behaviors of diversification of their production activities. The figure above illustrates this with a downward trend of prices weakening the welfare of producers.

The figure above is a trend of the average FCFA price of cocoa near planters in Cameroon. Indeed, this figure shows that prices have been very volatile since the 2000s and continue to be so far because of the harmful effects of the liberalization and devaluation of the CFA franc in the early 1990s, following the decline of commodity prices in the mid-1980s. This is not encouraging for the

Figure 1. Evolution of average prices to cocoa farmer from 2000 to 2016 in Cameroon. Sources: Author’s conception using research data with STATA 14.

producing countries, which are suffering from the sum of its shocks and are seeing their profits fade. On the other hand, this figure also shows that a posteriori prices seem to go back which would be good news for the cocoa producers even this one is only a logical continuation of a cycle which will have long impacted negatively on the conditions of life of cocoa farmers. There is therefore hope to hope in a horizon, certainly uncertain but more or less close to a relative rise in prices.

Notes: In cocoa trading, futures contracts traded on the futures and financial instruments market in London (LIFFE) and the New York Coffee, Sugar and Cocoa Exchange (NYBOT) are used as benchmarks for world. In Cameroon, export prices are correlated with LIFFE futures prices.

With regard to additional data on internal marketing costs and taxes, the analysis of additional data and the literature on marketing costs and taxes is particularly enlightening. Indeed, the breakdown of expenditures in the cocoa sector in Cameroon focuses on taxes and other charges levied on cocoa shipments; costs incurred at the plant and the port of export. “Export taxes and duties” include explicit export taxes (such as the export duty) on exports. “Other charges” include various fees to certain organizations, fees for quality inspection, and other administrative costs. These “Export taxes and duties” and “Other charges” together constitute the share of public levies in the export value of cocoa. The “Freight Forwarder” covers the general expenses and freight forwarder costs (shipping formalities, insurance and documents for the export of cocoa, and organization of delivery to the port). “Port Services” essentially covers the costs of quality inspection and Phytosanitary treatment, storage and port insurance, lighterage costs and other logistical costs (recent container loading system) and then other expenses (e.g. new packaging). “Initial processing and conditioning” is essentially expenditure (drying, sorting, bagging, weighing, marking, storage, etc.) at the plant level (packing plants, usually near the export port). “Other costs and margins” includes other costs borne by the exporter and the estimated cost of its profit margin [18] .

In practice, two analyses can be made: First, there is a significant reduction in taxes. A sharp decrease in the incidence of direct export taxes, partially offset by the introduction of new indirect taxes. On the other hand, marketing costs do not seem to have declined significantly. Since the share of producers in the export price is dependent on the marketing costs and taxes, the recent increase in the share of producers in the export price was more likely to result from tax reductions than cost savings from more efficient services; Second, the impact of the “exporter share” increased over the period considered, but there was insufficient information to examine in detail whether this increase was due to cost increases or increased profits. The “exporter share” here includes only certain overhead costs borne by the exporter and his profit margin. It does not cover all the functions to prepare the cocoa for shipping and load it on board the ship. These functions are taken into account here in various other cost items that are billed in practice to other parties (the freight forwarder for example) [19] .

With respect to other factual elements, changes in prices, costs and margins are at the heart of the competitive analysis. However, other factual elements of a more qualitative nature reveal practices in producer countries that might fall under the scope of competition law. In Cameroon, the National Cocoa and Coffee Board carried out a review of quality control certifications and export sales declarations which revealed certain shortcomings that could be due to questionable practices. In Cameroon, only grade I and grade II cocoa beans can be exported (grade I is the highest grade). Pre-shipment samples of the cocoa beans destined for export are collected to analyze and sort the beans to determine their quality and to issue the appropriate certificate. Indeed, if Grade I (GI) cocoa was exported as Grade II (GII) cocoa, this means that exporters in Cameroon have made “devalued” export sales contracts with their buyers, perhaps because of the unequal bargaining positions of the international buyer and the local exporter, or even the existence of collusion in them. From the point of view of competition law, this type of action could be considered an abusive practice. It is important to underline that the structural conditions on the cocoa market (with a limited number of buyers who have integrated upstream in the producing countries) may favor such practices [20] .

3.5. Impacts of Changes in the Chocolate Manufacturing and Consumption Sector on the Overall Market Structure

In consumer countries, the chocolate manufacturing sector and the chocolate consumption market have also undergone significant changes that are impacting the overall market structure. This section therefore aims to provide a more detailed explanation of these changes in the manufacturing sector and the consumer market for chocolate. So, an inventory of fixtures is a necessity to better perceive the issues facing the sector. The market for the manufacture and consumption of chocolate is conditioned by the global supply of beans, which is mainly made by African countries, Brazil, and Indonesia. Consumers being mainly, the countries of the EU, the USA and new emerging countries like China. Indeed, the cocoa supply market is facing a new dynamic that could bring about a paradigm shift, especially with the arrival of emerging countries, which constitute an important market for producing countries, which could lead to shortage of cocoa supply.

3.5.1. A Shortage of Chocolate Is Looming in the World

While consumers of this sweet sweetness (chocolate) are still more numerous and that global warming disrupts production, cocoa bean producers are unable to meet the demand. The demand for chocolate continues to grow due in particular to the massive arrival of new consumers from emerging countries. “The demand for this greed is exploding, especially in emerging markets, where consumers are getting richer and producers around the world are struggling to produce enough cocoa so that chocolate continues to flow,” said the very serious Wall Street Journal recently. In 2013, the world consumed for the first time more than four million tonnes of cocoa, 32% more than ten years ago. A surge in demand that has pushed the price of the precious commodity by more than 9% since the beginning of 2014 and nearly 40% in one year. In fact, producers have not been able to meet the entire demand. The cocoa harvest is mainly carried out by small independent farmers, mainly based in West African countries. However, they are not able to invest to increase their productivity, especially since the planting of new trees does not produce immediate effect since it takes at least ten years for a cocoa tree to produce beans. Not to mention that many small producers choose to turn away from this less lucrative crop than palm oil or rubber. The threat of global warming would further aggravate the phenomenon of scarcity. Rising temperatures are likely to affect cocoa crop [21] .

A rise in the price of chocolate is also felt. Indeed, the price of the cocoa bean should continue to grow. The International Chocolate Organization (ICCO) predicts that demand will exceed production in the coming years, the longest period of shortage since the organization publishes its statistics, since 1960, the business daily warns. An increase led by China, where demand for cocoa is expected to increase by 5% per year until 2020, according to Euro Monitor International. The price of chocolate and chocolate confectionery will inevitably rise, warns Sterling Smith, a specialist in the cocoa market. Manufacturers such as Mars or Nestlé will have to make a choice between increasing the final price of their property to pass on the increase in the cost of production, reduce the size of products sold or find a substitute for cocoa. Hershey has already started using cocoa butter as a substitute for chocolate in many of its products. Conversely, Michael Szyliowicz, co-founder of Mont Blanc Gourmet, had questioned his customers to ask them if they would prefer to have the same products but at higher prices or if they would prefer different products. The majority of customers opted for higher prices. It may be time to store the chocolate before its price flies [22] .

3.5.2. Chocolate Victim of the Economic Crisis

According to Cécile Chevré (2015), several reasons can be mentioned:

- rising demand, especially in emerging countries.

- the decline in production, which is threatened, among other things, by the risk of Ebola becoming contagious in the main world producers such as Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. It is the risk of crop disruption that caused cocoa prices to skyrocket in the fall.

- a greater concentration of cocoa players. These multinationals serve as intermediaries between the producers and the main buyers of beans, such as chocolatiers or large agri-food groups (Nestlé, Mars, Mondelez, etc.). Gold which says concentration says risks of movements more brutal on the prices at the least news on the supply or the demand.

- Add to that the recent decision of the Swiss National Bank (SNB) to abandon parity between the Swiss franc and the euro. As you most certainly know, Switzerland has earned a reputation for choice in the world of chocolate. Some of the biggest chocolatiers on the planet are Swiss: Lindt & Sprüngli (SWX: LISN), Nestlé (SWX: NESN).

The rise in cocoa prices has already pushed chocolate makers and manufacturers to take several measures, both upstream and downstream. Upstream, chocolate players have invested in producing countries to ensure sufficient production. In 2012, US giant Mondelez International launched the $400 million “Cocoa Life” program to support a responsible and sustainable cocoa sector. In early 2014, the French chocolate group decided to invest 4 billion FCFA in the construction of a processing plant in Côte d’Ivoire [23] .

Downstream, many chocolatiers and agribusiness giants have decided to pass on the rise in cocoa prices to consumers. Several strategies have been deployed in recent years: price increases of course, but also and especially lower quality or percentage of chocolate present in their products! It is a scandal! You must have noticed the massive appearance of “customized” chocolate bars on the shelves. The reason is simple: biscuits, caramel and other additions allow you to use less chocolate, thus reducing costs while pushing up the labels. This is the power of marketing and speculation. These strategies on the part of chocolate makers were supposed to counterbalance the effects of speculation on the prices of the bean. Cocoa has indeed become one of the commodities preferred by speculators of all kinds on commodities. The most famous episode: in 2010, Anthony Ward, called “Chocolate finger”, managed to explode the course of the bean on a speculative blow to 1 billion dollars. Proof that despite the efforts of the main players in the sector, speculators still have a taste marked by the tablet, the fall of 30% of cocoa prices. Behind the collapse that has seen the ton of cocoa rise from $3000 to $2000 an announcement that could upset the cocoa market in the coming months: global demand is plummeting [24] .

3.5.3. Chocolate, a Sign of a New Global Crisis?

The question is worth asking in the light of the latest figures published on the amount of beans crushed on each continent. In the fourth quarter of 2014, it decreased 7.5% year on year in Europe, 2% in the United States (while a slight increase was expected) and 21% in Malaysia. This is due to a sharp drop in the demand for chocolate in Europe as well as in the United States, as a result of the price increases imposed by chocolatiers and the food industry. The players in the sector are banking on rising demand from emerging countries to offset the decline in demand from traditional consumers such as Europeans and Americans. These are still struggling to be seduced by the virtues of chocolate. As a reminder, the Chinese consume only 38 grams per year against 4 kg on average for the French. Certainly, the margin of progress is important (the consumption of chocolate increases by 30% per year in China) but we do not see the empire of the Middle to convert massively to chocolate.

The announcement of a decline in cocoa consumption alone cannot explain the collapse of 30% of prices. And all the more so since the classes have resumed to regain their level of $3000. No doubt, speculators on commodities have once again accentuated the movement. But what does the medium term reserve for us? Despite falling demand, cocoa prices could remain at high levels while production in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana is threatened by weather conditions. In addition, in the long run, all analysts agree on one point: the scarcity threatens. In November 2014, Barry Callebaut again pointed the finger at risk while the March group expects a deficit of one million tonnes in 2020. What to increase appetites for a global market estimated at 110 billion dollars in 2014 and this explains why Lindt’s action on the Swiss Stock Exchange has not flinched under the news of the soaring franc but has even progressed in recent days. You will now have to pay 55,000 Euros to buy a Lindt share.

The Swiss group Barry Callebaut, world leader in the sale of chocolate to professionals, relies on measures stamped “sustainable development” to increase cocoa production in Africa, to meet the growing demand for chocolate.

The world engulfs more cocoa than it produces. The deficit, measured by the difference between milled beans and harvested beans, is expected to reach 115,000 tonnes this year according to the latest forecast by the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). If stocks are still sufficient to avoid a shortage, the situation should not improve. Indeed, with the growth in emerging countries of middle classes increasingly influenced by “Western” tastes, demand is likely to explode. In China alone, it should rise from 5% to 6% per year until 2020. If the consumption of chocolate in emerging countries increases to 2 kg per year and per person against 50 grams currently, to get closer to the consumption in western countries (7 kg in France), the demand will be “difficult to satisfy”, worries Juergen Steinneman, the director-general of Barry Callebaut, world leader in the cocoa powder and chocolate markets. “It is estimated that by 2020, we will need about a million additional tons of cocoa beans,” said Philippe Janvier, vice president of Barry Callebaut in charge of the Europe zone.

A weakened production

For the number one supplier of the market, as for the more well-known groups, the stakes are all the more important as production tends to decrease. In addition to frequent concerns about political stability in producing countries, Côte d’Ivoire being the most important, we must add diseases that weaken cultures. Not to mention other factors such as rural exodus or competition from other types of crops considered more profitable that would also weigh on production. In the 2011/2012 and 2012/2013 seasons, production fell by 5.3% and 3.5% year-on-year, according to figures from the ICCO, but should rise again.

In the first line

Barry Callebaut likes to point out: one out of five consumer chocolate products comes (indirectly or not) from its factories. The company holds “25% market share in the processing of cocoa beans,” says group CEO Juergen Steinemann. Suffice to say that in case of too much fluctuation, “we will be affected first,” he warns. Also the way the company born in 1996 from the merger between the French Cacao Barry and the Belgian Callebaut does it to anticipate the problem is not only crucial for the sector (Mondelez, Nestlé, etc. are its customers) but also rich in lessons.

Sustainable development

To secure its supply and get closer to these new markets, Barry Callebaut acquired last year the cocoa business of Singaporean company Petra Foods. A way to diversify its sources, nearly 60% of the raw material is now purchased in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. For the future, the Zurich group relies above all on a model of intensification of production via programs of sustainable development. He organizes them alone, without the intermediary of specialized associations. It focuses on improving productivity in Côte d’Ivoire’s plantations. Philippe Janvier, also head of the brand in France, explains: “Thanks to more appropriate cultivation techniques, we could easily double these yields. It is our responsibility to train farmers, to provide help to increase yields in Côte d’Ivoire of Ivory and in other countries afterwards.”

No to GMOs

From 400 kg of beans per hectare, the Swiss company hopes to see the yield of these plantations increase to 800 kg. And for that, she says she does not believe in pesticides, fertilizers and even less GMOs. “For basic research, our research and development centers focus on the properties of chocolate and cocoa for health,” says Philippe Janvier. Genetically modified beans as used in Ecuador, for example, would be unattractive in terms of taste and the big producers of GMOs such as Monsanto would in any case find unattractive a market as small as cocoa, compared to soybean, points Juergen Steinemann.

For the director of the Swiss group, the secret, “it’s training”. Teaching producers how to better manage their crops, how to better maintain their land, would be enough to increase their productivity and meet rising demand. The group expects to invest 7 to 8 million Swiss francs in Ivory Coast this year (5.7 to 6.5 million euros).

Small farms

Responding to the risk of scarcity through sustainable development is an idea shared by other players in this industry. Marc Blanchard, CEO of the Max Havelaar association in France, told the Tribune at the end of April that policies to support producers “can help rebalance supply and demand.” However, given the structure of farms―often very small, between 2 and 3 hectares―and the multiplicity of producers (750,000 in Côte d’Ivoire), only an ant work, on the spot, could allow these projects to support producers to bear fruit.

Still the problem of child labor

Finally, these good intentions also displayed by the competitors do not prevent the multinational chocolate companies from being regularly criticized by human rights defenders, for example about child labor, or ecologists about the environment. Regarding Barry Callebaut, if the Zurich group is rich in a fund to fight against child labor in Africa, he was singled out in March 20013 by an American NGO to be one of the lowest contributors with 100,000 dollars committed per year between 2012 and 2014 against more than 900,000 by March.

3.5.4. Chocolates Stuffed with Economic, Social and Environmental Issues

In 2016, the cocoa sector is characterized by unequal relationships between thousands of producers and producers of beans and some processing companies, which has many negative impacts. This analysis attempts to understand the vicious circle engendered by the mass chocolate market and the challenges to fair trade to avoid the announced crisis and guarantee the food sovereignty of cocoa farmers.

Agro-industry at the origin of an announced shortage

The standardization initiated over more than a century in order to ensure a production of cocoa at constant quality, whatever the origin of the bean and production practices. The cocoa bean has thus become a raw material subject to speculation, the price of which varies according to world prices. The liberalization of the sector at the end of the 1980s, which, by putting an end to various attempts at international regulation, notably resulted in the arrival of the main traders, ADM and Cargill, in the cocoa sector and led in reaction the merger of Barry and Callebaut (now Barry Callebaut, world leader in cocoa processing). Since then, these three players have dominated the global transformation of cocoa and are strengthening their presence in producing countries while investing in ever larger and more efficient processing plants.

Fair trade as an alternative for the sustainability of the sector at all levels

The establishment of cocoa prices in the countries of production that enable producers and their families to meet their basic needs; The financial contribution of the cocoa sector to give the communities that live there the necessary means to enable them to invest in local essential services and their local development; Strengthening and developing cocoa farmers’ organizations that are dynamic, appropriate and governed by their members; Promotion of the agroforestry model at the heart of the cocoa sector; The development of chocolate value chains that value the quality of cocoa and the original production from consumers.

Challenges remain to be met for fair trade to be a real alternative to the conventional model

In terms of support for producers, it is clear that, depending on the region, the beneficial impacts of fair trade are more or less felt by the families of producers. At the transformation stage, the complexity of the process, the necessary infrastructure and the very high concentration of the sector mean that it is not easy to get out of the “conventional” system. The chocolate industry is responsible for illegal deforestation linked to cocoa farming in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana, according to Mighty Earth (January 2018).

The NGO Mighty Earth denounces the impacts of the chocolate industry on the Ivorian and Ghanaian forest canopies (Espoir Olodo, 2017). Chocolate is not only a luxury consumer product, it is also a source of destruction of many forest covers in the main suppliers of raw materials that are Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. This is the main conclusion of Mighty Earth’s new report, “Bitter Deforestation of Chocolate”. For the Organization, actors in the global chocolate industry, be they traders (Barry Callebaut, Cargill and Olam) or chocolatiers (Hershey’s, Nestle, Mondelez, Lindt and Ferrero), maintain deforestation in these two countries and provide raw material for cocoa plantations established in protected areas. “We were able to identify seven cooperatives that bought cocoa from the protected areas we visited, and then confirmed that they sold it to major international traders like Cargill, Olam and Barry Callebaut. It is obvious that these traders are responsible for creating a market for illegally grown cocoa, which eventually gets into chocolate bars consumed around the world”, says the NGO. “A study conducted by Ohio State University on 23 protected areas in Côte d’Ivoire, concluded that seven of them had been almost entirely converted to cocoa. Not far away, in Ghana, the world’s second-largest cocoa producer, the situation is the same: between 2001 and 2014, 117,866 hectares of protected areas were cleared and Ghana lost more than 7000 square kilometers of forest, at least 10% of its total forest cover; one-third of the country’s deforestation can be attributed to activities related to the chocolate sector. Adds Mighty Earth. In response to the recent commitment of 35 cocoa and chocolate companies around the world, is the presentation of a framework for action leading to a cocoa supply chain without deforestation next November at the 23rd Conference of the Parties (COP23) in Germany. The Organization remains skeptical.” These companies can make a huge difference because they together hold the overwhelming majority of the chocolate and cocoa market. But for the moment, they have not provided any details as to the exact nature of their program, which must be done by the end of the year. For example, they have not yet guaranteed that future crop expansions will be carried out without deforestation, in order to protect landscapes with high carbon stock. Nor did they explain their action with regard to cleared territories in Côte d’Ivoire’s national parks and protected areas. The report says.

Thus, it emerges after analysis that the impact of changes in the consumer manufacturing and consumption market in consumer countries on the structure of the market as a whole seems to be indicative of a sluggish market. Problems related to supply scarcity, price volatility, challenges to fair trade, environmental and social problems related to deforestation are some of the factors that influence the structure of the market. Nevertheless, some solutions are being taken by some multinationals (like Barry Callebaut) to sustain the sector [25] .

4. Challenges and Prospects for Reviving the Cocoa Sector in Cameroon

➢ Research and Development

Cocoa research is carried out in Cameroon by IRAD, through its research on stimulating plants, the related technical itineraries and the organoleptic qualities of cocoa. It is a dynamic that IRAD has developed but which, unfortunately, faded at the beginning of the 1990s with the disengagement of the State from production activities. However, IRAD has a large gene bank on cocoa that can produce varieties that can meet the criteria of productivity, competitiveness and disease resistance. In terms of infrastructure, this institution has laboratories and scientific workshops for the development of cocoa varieties.

In terms of support for research and development, the plan for the revival and development of the coffee and cocoa sector (PRDFCC) will continue the production of efficient and early basic plant material. To this end, IRAD’s capacities will be strengthened, particularly in terms of infrastructure, equipment and human resources.

➢ Production

Since the implementation of the 2002 Recovery Plan, cocoa production has evolved differently in terms of both quantity and quality.

On a quantitative level, the analysis of the evolution of cocoa production (confers Table A1) shows that it has grown progressively in the period 2002/2011, from 140,000 tonnes in 2002 to 210,000 tonnes in 2011 with a peak of 228,500 tons in 2010 for an annual growth of about 5.9%. Despite the exceeding of the cocoa production targets set by the 2002 stimulus plan of 200,000 tonnes for the years 2010/2015, the estimated annual growth rate remains relatively low, reaching the projected 600,000 tonnes in 2020. The need to step up existing actions and develop new ones is in fact necessary.

As regards quality, it has deteriorated considerably over time so as to begin the Cameroon origin, particularly as regards cocoa beans. Indeed, Cameroonian cocoa suffers from the non-respect of the different technical routes of the pre and post-harvest operations. These important operations, even when they are carried out, are not always in line with good practice, especially with regard to Phytosanitary treatments, fermentation and drying. The smells of smoke and tar, pesticide residues, and the virtual disappearance of grade I are the consequences.

The performance of the cocoa sector highlighted in this way is the result of the fact that most small-scale producers, whose farms are mostly of the family type, are atomized in all the production basins located in the appropriate agro-ecological zones.

More and more, there is a craze for elites and other active or retired workers, as well as young people trained in the renewal of agricultural education and training, to settle in cocoa production. This new class of agricultural producers or entrepreneurs, more open to innovation, represents an important potential for the development of sectors. The operators of the sector benefit somehow from the various services and supports offered by the public authorities and other stakeholders through different projects and programs. The services offered are mainly related to training, extension and agricultural information. The support is in cash or equipment such as plant material, fertilizers and pesticides and equipment and small agricultural equipment. The size of cocoa orchards is currently poorly known. It is nevertheless estimated at 600.000 hectares for cocoa trees.

Despite the overall upward trend in cocoa production between 2000 and 2016, it must be recognized that the current performance of this sector remains below potential, due to the constraints it faces [26] .

➢ Marketing

The liberalization of cocoa marketing has profoundly changed the internal and external marketing system, formerly implemented by the former ONCPB. This situation has had a negative impact on the quality of the products, from the purchase to the producers until the exportation and the delivery in the principal ports of destination, which has started the image of the Cameroon origin on the international market.

Internal marketing

The internal marketing of cocoa in Cameroon is governed by a legislative and regulatory system, the application of which is revised at the beginning of the campaign. However, having moved without transition from the state monopoly system to full liberalization throughout the national territory, internal marketing now induces an undifferentiated collection of field products and facilitates the blending of qualities and harvests by farmers.

If the current marketing system now allows the producer, especially with regard to cocoa, to receive a price representing more than 80 per cent of the international price, if the operators of the sectors can operate freely on all production basins without concessions and without quotas, on the other hand, the general environment of the marketing of the products remains gangrenous, and without being exhaustive, by the dysfunctions hereafter: the absence of organized markets at the level of the producers; lack of pre quality control; the inadequacy of the market information system; the proliferation of stakeholders and the lack of professionalization; lack of funding for marketing operations and subsequent vulnerability of producers; weak control of boarding; the insufficient application of the texts in force; low adaptability to the global commodity economy; the absence of the State and/or the supervisory bodies of the sectors; weak collaboration of stakeholders and obsolescence of the institutional framework; the disarticulation of the die.

External marketing

As a result of the total liberalization decided in the 1990s, external marketing is characterized, among other things, by: a multiplicity of stakeholders without specifications; a fragmentation of the offer; a lack of follow-up after boarding [27] .

➢ The quality of the products

The liberalization of cocoa marketing has had a negative impact on quality. Exporters have had a low propensity to seek improvements in product quality. Indeed, the adoption in 1992 of the packaging standards of the French Association of Cocoa Trade (AFCC), instead of those of the FAO used by the former ONCPB, led to the degradation of the quality of the products. The Cameroonian cocoa market is confronted with the non-respect of the technical itineraries, notably the fermentation times and the humidity rate required by the regulations. In the Southwest Region, where rainfall is over six (6) months, cocoa drying ovens have been popularized. The state of obsolescence and the lack of maintenance of these ovens lead to the production of beans with strong smell of smoke, rejected by the chocolatiers.

The decline in the quality of products and the change in the marketing system, have strongly contributed to the negative evolution of the differentials of Cameroonian labels on the international market. The quotation of the Cameroon origin has been on par with the international market since 2005, but the premium on quality (“Good Fermented”) has disappeared. During the 2012 and 2013 campaigns, deliveries suffered penalties in the range of £40 to £ 80/MT, due to their non-compliant quality [28] .

➢ Product transformation

Several technological innovations have been developed in recent years. For cocoa, beyond the grinding of beans, the processing of other parts of the fruit makes it possible to produce products of various uses. The mucilage of the pod makes it possible to produce sweetened or alcoholic drinks while the cortex can be used in breeding and the mineral or organic fertilization of the plants (compost or potash fertilizers).

The constraints related to the transformation are: the weak infrastructural capacity and the lack of qualified personnel.

The recommended actions are: for research―the census and popularization of product processing methods and the development of a catalog of existing innovations (products and by-products)―the optimization of processing methods that meet the standards of national and international quality―the rehabilitation and development of technical research platforms in relation to modern methods of transformation and training of trainers. Research/Extension Services This will include: capacity building of producers, and other investors in cocoa processing and stakeholder ownership of the relevant quality standard legislation―Development and implementation of an effective financing plan for product processing in conjunction with MINMIDT.

In Cameroon, a single processor has been installed for 60 years because of the lack of incentives. The conversion rate is relatively low, about 15% of the national production.

The other producing countries are 43% for Côte d’Ivoire, 25% for Ghana, Indonesia is now processing all its production, and becomes an importer of cocoa to meet the need for installed capacity. Indeed, domestic production in these countries is much larger than in Cameroon and therefore, the choice of the cocoa sector has a greater impact on world prices in terms of price and premium for the origin of cocoa; the quality of cocoa is better (controls on the ground much more organized, disciplined and effective than in Cameroon regardless of the marketing model adopted) [29] .

➢ Constraints for the development of the cocoa sector

Technical constraints: they relate to the low productivity and competitiveness (quality) of products. These are the result of no or bad application of the recommended technical itineraries, due to the difficulties of access to agricultural inputs and services, the aging of planters and plantations.

Other constraints: these are organizational and institutional constraints, which are linked on the one hand to the weak structuring of the producers, who therefore do not always have the necessary weight in the negotiations and on the other hand to the weakness of the coordination of the sector that gives free reign to institutional interference that does not always benefit the sector.

The financing constraints are linked to the low level of funding in the sector and the lack of appropriate mechanisms linked to the numerous interferences that disperse the limited resources available. The FODECC (cocoa and coffee development fund), which is the dedicated financing structure, is “competing” with other structures that draw directly on the source of the royalty, when they do not simply become additional financing geared towards the sector [30] .

The natural constraints are those related to climate change that jostle the agricultural calendar, making it unmanageable, with the frequent and non-cyclical occurrence of diseases and pests often difficult to control.

In view of the above, the rapid development of cocoa production, to meet the production challenges by 2020, requires the removal of the constraints thus identified, and urgently those that have a rapid and short-term impact on productivity. It therefore seems appropriate to accelerate the production and dissemination of seedlings in order to meet demand quickly, to facilitate the fertilization of cocoa trees and to proceed with the complete protection of orchards; all things that would increase the current yields by at least three, a necessary condition to increase production by at least 2.5 by 2020 and to reach or exceed the production targets set [31] .

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

The purpose of this paper was to present, in a general manner, the organization, structure and operating mechanisms of the Cameroon cocoa market, particularly the value chain from family farmers to consumers through exports; it also aimed to highlight some issues and prospects related to the revival of the cocoa sector in Cameroon. It shows that Cameroon, like most cocoa-producing countries, also faces many difficulties not only externally, but also because of the international environment (the volatility of the prices of export products), internally through implemented policy measures, their consistency, and phasing, as well as their deadlines. Starting from the liberalization of the sector in the early 1990s to the devaluation of the CFA franc in January 1994, a relative stagnation of the country’s agricultural performance has been noted so far. The problem is therefore not only structural but also cyclical. The corrective measures are envisaged, for example, in the internal marketing of products, aim, inter alia, to: improve the producer price; cushion the impact of international price fluctuations on producer prices; restore the differentiated collection of products and the deterioration of export quality; fight against the under-payments of the products, because of the difficulties of access to the places of purchase; improve the competitiveness of cooperatives; institute a framework for consultation involving all public and private stakeholders, under the coordination of the Branch Authority. The government option of a return to stabilization will reaffirm the place and the role of the State in the management of the sectors. With regard to the constraints related to external marketing, to remedy this, the government option for external marketing is the establishment of a system of advanced sales, controlled by the State, through centralization sales and monitoring of their quantitative and qualitative execution to the ports of destination.

In addition, for the development of Cameroon’s artisanal, semi-industrial and industrial processing industry in both cocoa and coffee roasting, it is recommended that: strong support and protection of the local industry in order to attract foreign investors and encourage local initiatives, with accompanying measures that make cocoa processing more profitable in Cameroon as in other producing countries, should be put in place.

Some recommendations in economics policy

1) With regard to the internal marketing of products, the aim here is to improve the producer price; mitigate the impact of international price fluctuations on producer prices; restore the differentiated collection of products and the deterioration of the quality of exports; fight against the underpayment of the products, because of the difficulties of access to the places of purchase; improve the competitiveness of cooperatives; establish a consultation framework involving all public and private stakeholders, under the coordination of the branch authority. The government’s option of a return to stabilization will reaffirm the place and role of the state in the management of the sector.

2) With regard to external marketing constraints, to remedy this, the government option for external marketing should be put in place, together with a state-controlled advanced sales system to centralize sales followed by their execution destination.

3) Respect for international standards in terms of quality necessarily entails the respect of technical itineraries in the production process. Industry experts and the government must go in this direction to improve the perception of the Cameroon label in the international market. In addition to the GI (Geographic Indicator) approach, it also seems to be one of the ways to improve the quality of cocoa from Cameroon.

In addition, the impact of changes in the consumer manufacturing and consumption market in consumer countries on the market structure as a whole seems to be indicative of a sluggish market. Problems related to supply scarcity, price volatility, challenges to fair trade, environmental and social problems related to deforestation are some of the factors that influence the structure of the market. Nevertheless, some solutions are being taken by some multinationals (like Barry Callebaut) to sustain the sector. However, one of the limitations of this study is that we have not conducted a survey of producers and professionals in the sector to better understand its operationalization. For this purpose, therefore, future studies in this area field can be realized to further this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

Herve, Z.E. and Zhao, G.Y. (2018) Cocoa Exports of Cameroon: Structure and Mechanism of Operation. Theoretical Economics Letters, 8, 3223-3251. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2018.814200

References

- 1. Lipchitz, A. and Pouch, T. (2008) The Changes in the Global Coffee and Cocoa Markets. Géoéconomie, No. 44, 101-124. https://doi.org/10.3917/geoec.044.0101

- 2. ECOWAS-SWAC/OECD (2007) Atlas of Regional Integration in West Africa.

- 3. Robert, B. (1962) The Participation of the Agricultural Sector in Financing Economic Growth. Third World, 3, 143-162.

- 4. Chominot, A., Benoit, D. and Michel, G. (1996) Introduction. In: Rural Economy. No. 234-235, Globalization of Agricultural and Food Economies. Situation and Prospective, 3-9. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecoru.1996.4796

- 5. Gilbert, C.L. and Varengis, P. (2003) Globalization and International Commodity Trade with Specific Reference to the West African Cocoa Producers. Dans NBER Working Papers, National Bureau of Economic Research.

- 6. Abena, P.E. (2009) The Measures Taken by the Government to Achieve a Sustainable Cocoa Economy: The Case of Cameroon.

- 7. Abena, P.E. (2006) Liberalization of Cameroon’s Cocoa and Coffee Sectors and the Transparency of Markets.

- 8. Courade, G., Eloundou-Enyègue, P. and Grangeret, I. (1991) The Central Union of Agricultural Cooperatives of Western Cameroon (UCCAO): From the Commercial Enterprise to the Peasant Organization. In: Third World, Volume 32, Agrarian Policies and Farmer Dynamism: New Directions? 887-899.

- 9. UNCTAD (2008) Cocoa Study: Structure of the Industry and Competition.

- 10. UNCTAD (2016) A Basic Product Profile by INFOCOMM: The Case of Cocoa.