Vol.2, No.7, 796-803 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.27120 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health HIV clinic caregivers’ spiritual and religious attitudes and behaviors Elizabeth A. Catlin1*, Jeanne H. Guillemin2, Julie M. Freedman3, Mary Martha Thiel4, Sandra McLaughlin5, Cheryl D. Stults6, Marvin L. Wang7 1 Ethics, MassGeneral Hospital for Children, Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA; *Corresponding Author: ecatlin@partners.org 2Sociology Department, Boston College, Boston, USA 3Infectious Disease Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Cambridge, USA 4Clinical Pastoral Education, Hebrew Senior Life/Hebrew Rehabilitation Center, Boston, USA 5Department of Social Services , M as s achusetts General Hospital, Cambridge, USA 6Sociology Department, Brandeis University, Waltham, USA 7MassGeneral Hospital for Children, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA Received 10 March 2010; revised 15 March 2010; accepted 16 March 2010. ABSTRACT Based on prior research, we hypothesized that staff in an outpatient clinic caring for an HIV patient population might rely on religious and spiritual frameworks to cope with the strains of their work and that their responses to a spiritual and religious survey might reflect work-related spiritual distress. Surveys were completed by 78.7% of s taff (n = 59 ). All res pond ents scored in the "moderate" range for religious and spiritual well-being as well as existential satisfaction with living. The large majority agreed that the religious and spiritual concerns of p atients hav e a place in patient care. Nurses, (88.2% of nurse respondents) viewed assessing the spiritual needs of patients as their responsibility, (p = 0.03). While 82% of HIV clinic respondents pri- vately prayed for patients always, often or so- metimes, this did not include physicians. Phy- sicians in this clinic setting appeared to be less spiritual and religious, based on their survey responses, than coworkers and than US physi- cians in general. The majority of clinic physi- cians (78%) believed that God does not suffer with the suffering patients, in contrast to the majority of su pport staff (69%) and nearly h alf of the nurses, who believed that God does suffer with them, (p = 0.018). Contrary to our expecta- tion, respondents did not report work-related spiritual distress, which may be related to im- proved therapies that can prolong and improve patients’ lives. Survey data revealed, however, a surprising level of engagement in and reliance on spiritual and religious frameworks among nurses and support staff. Whether the absence of measured spiritual distress is linked, in a causal rather than random manner, to spiritual and religious reliance by certain of these health care providers, is unknown. Keywords: Spirituality; Religion; Caregivers; Caregiver Bu rden 1. INTRODUCTION The emergence of AIDS in the early 1980’s [1,2] pre- sented formidable challenges to healthcare providers an d hospitals. Mortality and morbidity caused by infectious diseases had progressively declined in the twentieth century; better sanitation, childhood vaccination, and the introduction of antibiotics dramatically reduced the risk of serious epidemics. Instead, hospital staffs grew famil- iar with mortality from cancer, heart disease, stroke, and other conditions associated with longer life spans and industrial societies. The organizational response of hos- pitals to the spread of HIV disease was the formation of specialized infectious disease units. In the subsequent nearly thirty years, advances in technology have sub- stantially prolonged and improved the quality of life for treated individuals with HIV disease, increasingly iden- tified as a chronic condition. Consequently, the medical management of patients with HIV disease resembles that of other life-threatening conditions: the trajectory of a patient’s life can be extended by reliance on technology and clinical care, if available. The epidemic, while fundamentally different, contin-  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 797 797 ues [1]. Worldwide, 0.8% of adults are estimated to be infected with HIV; resource-limited regions bearing the greatest disease burden [3]. The estimated number of persons in the U.S. living with HIV disease is 1.2 mil- lion, 35,962 have progressed to AIDS [4]. Hospital staffs remain responsible for chronic ambulatory care of these individuals as well as for difficult, end-of-life care [5]. In addition, attention has turned to the suffering, physi- cal and non-physical, of patients and to the potential role of spirituality in the clinical setting. In 2006, for exam- ple, the U.S. Department of State issued guidelines for global AIDS relief that included spiritual care “that ad- dresses the major life events that cause people to ques- tion themselves, their purpose and their meaning in life” [6]. In this article we pose the question of whether hospital staffs that care for patients with HIV disease have a sense of spiritual or religious dimensions in their work. In a previous article [7] this and related questions were asked of those who work in the newborn intensive care unit (NICU) context, where caring for critically ill and dying newborn babies raises existential and spiritual concerns. These physicians, nurses, and other providers, as they met their NICU responsibilities, were privately concerned with the meaning of suffering and death and were also aware of the need for pastoral support. In the present study, we test the hypothesis th at HIV clinic pro- viders might rely on spiritual and religious frameworks in caring for their patients and that work-related spiritual distress might be a common theme for them. 2. METHOD This 65-item questionnaire study was approved by the Human Studies Subcommittee of the Institutional Com- mittee on Research, [Supplement]. The instrument used was a version of the aforementioned NICU questionnaire. It was revised for care providers of adult patients, with added spiritual well-being questions [8]. From March through July 2003, the survey was made available on line to all staff members of an ambulatory HIV clinic in a large metropolitan hospital, at a workstation away from the immediate patient care area. Respondents were also given the opportunity to write in comments, for example, to questions concerning the particular difficul- ties of their work. Participation was voluntary and anonymous and a gift coupon was provided as reim- bursement upon survey completion. A Microsoft Access 97 relational database was used to obtain and store re- sponses from the questionnaire-assigned data table. We surveyed 59 of the 75 staff members (78.7%). The respondents included 23 physicians, 17 nurses, and 19 administrative and support staff. The complete data set of survey responses was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using the statistical software program SPSS version 13.0. Frequency distributions were produced, cross tabulations performed, and Pear- son’s Chi-square statistics calculated on the independent demographic variables of position, age, years worked in the HIV clinic, years worked in the hospital, race/eth- nicity, education, religion, marital status, parental status, and gender against other relevant variables. Significance was assigned for p values less than 0.05. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Staff Characteristics Most participants (49.2%) were 30-39 years of age, fol- lowed by 20.3% in the 40-4 9 years’ group, 16.9% in the 20-29 years’group, and 13.6% were 50 years of age or older. There were more female respondents (34, 57.6%) than male (25, 42.4%), (Ta ble 1). The support and ad- ministrative staff were predominantly female (16/19), and males comprised 70% of the physician staff. The majority of respondents reported their race as white; less than 10% identified themselves as African-American or Asian (Table 2). One third (35.6%) of the HIV clinic staff reported being parents; 49.2% of the staff were married or pa rtnered. 3.2. Religious Identification and Spiritual Assessment The largest portion of staff, 28.8%, identified themselves as Catholic, 18.6% as Jewish, 10.2% as Protestant, 6.8% Christian Orthodox, 6.8% selected “other”, 5.1% Epis- copalian, 1.7% reported being Buddhist, 1.7% Quaker, and 13.6% of staff reported no religious affiliation. However, of physician staff, one fifth (20%) answered that they had no religious affiliation. All survey respon- dents scored in the “moderate” range for spiritual well being (41 to 99 score); similarly, 98.3% scored in the “moderate” category for religious well-being. For satis- faction with life, 98.3% indicated moderate levels. The great majority of the staff acknowledged that sp iritual or religious concerns were important in patient care. When asked if the spiritual/religious concerns of a patient have a place in patient care in your view, 49.1% answered “always”, “often” or “yes” (2 responses), and another 44.1% (26) answered “sometimes”; 6.8% (4) answered “seldom” (see Table 3). Overwhelmingly, the respon- dents answered affirmatively, 93.2%, to the question of the appropriateness of attending to spiritual/religious concerns in the course of caring for patients while only 4 staff members answered “seldom” and no one replied “never”.  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 798 The HIV clinic staff was asked how frequently they as- sessed the spiritual or religious needs of patients and 22% answered “always”, “often” or “yes” and 37.3% answered “sometimes”. The remaining respondents were more hesitant, 40.7% (24) answering “seldom” or “never” (see Table 3). When aske d if they felt competent to do a basic spiritual assessment, 25.8% answered “always” or Table 1. Basic demograp hic s: complete c ases. Frequency Percent Position Physician 23 39% Nurse 17 28.2% Support and Administrative Staff 19 32.2% Total 59 100.0% Age in years 20-29 10 16.9% 30-39 29 49.2% 40-49 12 20.3% 50+ 8 13.6% Total 59 100.0% Years in HIV < 1 6 10.2% care 1-4 21 35.6% 5-9 15 25.4% 10+ 15 25.5% missing cases 2 3.3% Total 59 100.0% Years at study institution < 1 11 18.6% 1-4 24 40.7% 5-9 14 24% 10+ 10 17% Total 59 100% Parent Yes 21 35.6% No 38 64.4% Total 59 100% Gender Female 34 57.6% Male 25 42.4% Total 59 100% Table 2. Basic demographics with missing cases. frequency percentvalid % Race African-American3 5.1% 5.4% Asian 2 3.4% 3.6% White 49 83.1% 87.5% Other 2 3.4% 1.8% missing cases 3 5.1% 1.8% Marital status Single 22 37.3% 40.0% Married 21 35.6% 38.2% Partnered 8 13.6% 14.5% Divorced 4 6.8% 7.3% missing cases 4 6.8% Religion Jewish 11 18.6% 20.0% Catholic 17 28.8% 30.9% Episcopalian 3 5.1% 5.5% Christian Orthodox4 6.8% 7.3% Quaker 1 1.7% 1.8% Protestant 6 10.2% 10.9% Buddhist 1 1.7% 1.8% None 8 13.6% 14.5% Other 4 6.8% 7.3% missing cases 4 6.8% Education High School/GED3 5.1% 5.3% Associates Degree4 6.8% 7.0% Bachelors Degree 10 16.9% 17.5% Masters Degree 16 27.1% 21.8% MD 25 39% 40.4% Other 1 1.7% 1.8% missing cases 2 3.4% “often” while 37.9% responded “sometimes” and re- maining staff (36.1%) indicated “seldom”, “never” or “no”. Nearly two thirds of staff across the various job categories indicated that they were ill equipped to do a basic spiritual assessment. Lack of training in spiritual assessment was cited by more than half of the staff and a nother 38.5% replied that they were too busy or that  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 799 799 Table 3. Staff self-assessment of spiritual care giving. Spiritual concerns have role in patient care I assess patients’ spiritual/ religious needs I am competent to perform a spiritual assessment* Always or Often 49.1% 22% 25.8% Sometimes 44.1% 37.3% 37.9% Seldom or Never 6.8% 40.7% 36.1% *(1) case missing spiritual assessment was not part of their job description. When asked to identify which members of the staff should be given the responsibility for assessing a pa- tient’s spiritual needs, most respondents chose social workers (88.1%), nurses (62.7%), attending physicians (61%), followed by medical fellows (57.6%). Nurses, in particular (88.2% of nurse respondents), viewed assess- ing the spiritual needs of patients as their responsibility, (p = 0.03), in keeping with the long-term historical inte- gration of spiritual care into the discipline of nursing. There was not a chaplain assigned at this time to the HIV clinic team; staff responses to this and related ques- tions may have been influenced by this fact. When asked which members of the team should in- clude consideration of the patient’s religious/spiritual needs in planning their care, 93.2% selected the social worker, 79.7% indicated the attending physician and 71.2% indicated the fellow. Physicians and nurses in particular favored the fellow’s taking this responsibility, (p = 0.016). Fewer respondents (42.4%) indicated the intern or resident, while 76.3% indicated the nurse and 71.2% the nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant. Note that in this question, respondents were asked to select as many individuals as they thought should be involved in th is process. Hospital chaplains were favored by 40.7% of staff when asked wh at resources they drew on to help resp ond to a patient’s spiritual needs. A patient’s clergy person was selected by 32.2%, colleagues by 42.4%, while 18.6% indicated that they would turn to reading or re- search. 22.0% of staff replied that responding to a pa- tient’s spiritual needs is not within the scope of their practice: eight of these respondents were support and administrative staff (p = 0.03). 3.3. Staff Experience The staff experience in HIV work varied but overall was modestly long-term. Ten of the 12 attending physicians were experienced in HIV work for five or more years. Twelve of the 17 nurses were experienced for five or more years. The same was true for the three social workers and for 4 of the 16 support and administrative staff. Concerning stress relief, many chose physical exercise (61%), watching movies or reading (44.1%) and a few indicated they relied on alcohol (3) or drugs (2). About one third of the respondents (30.5%) indicated they re- lied on “personal spiritual practice”. More indicated that they participated in social activities (50.8%) or relied on family and friends (54.2%). Some respondents sought psychotherapy (15.9%) for relief of stress. When asked, “Do you think spiritual caring is an ap- propriate part of your caregiving role?” 72.9% of the HIV clinic staff surveyed responded affirmatively. Phy- sician staff differed somewhat in this response category, as nearly 40% felt that spiritual caregiving was not an appropriate part of their role in the clinic. Of the clinic staff, 30% indicated that they always or often privately prayed for their patients, but most respondents (66.7%), when asked if they personally prayed with patients when they were with them answered, “never”, (Figure 1, Ta- ble 4). When asked if they would like to offer to pray with patients, (22) responded “never”. These included ten of the 12 physicians (all six attending physicians, three of the five fellows, and the one intern) who had responded that spiritual care giving is an appropriate part of their professional role. Others responded “sometimes” (35.9%), and very few (3) indicated “always”, “often”, or just “yes”, (Ta bl e 4 ). Despite this reluctance, most staff in- dicated a willingness to respond to a patient’s request for prayer. Asked to respond to, “If a patient asks for prayers I get someone else to do it who is capable”, the staff members who valued spiritual caregiving were divided into approximately one-third who answered negatively and two-th irds who respond ed affirmatively. Most of the latter indicated that they would get someone else “some- times”, while (8) indicated “always” or “often”. When asked to respond to, “If a patient asks for prayers I don’t follow through on their request”, 78.1% of those re- sponding to the question answered “seldom” or “never” (see Table 5). 3.4. Hardest Part of the Work Respondents were asked to define the hardest part of their work in the HIV clinic. The responses fell into three general categories. One concerned technical and infor- mational obstacles, that is, not having a cure or not being  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 800 able to keep up with all the available and relevant infor- mation. The second category of responses concerned personnel and bureaucratic difficulties, such as difficult colleagues or tedious paperwork. The third category in- cluded respondents that cited suffering for and anxiety about patients as the hardest part of their work. Of the 49 who responded to this survey question, physicians tended to be more concerned about technical obstacles, while nurses responded that personnel/bureaucratic is- sues were the hardest part of their work (p = 0.002). Compassion for the patients in answering this question was widely evident but support staff displayed the most concern. Examples of the open text responses to, “What is the hardest part of y ou r jo b?” included: “Dealing with the inefficient and wasteful delivery of care to our patients which leads to fewer resources avai- lable for all.” Figure 1. Prayer practices reported by clinic staff. Table 4. Prayer practices reported by clinic staff. I personally pray for patients when I am with them (n = 39) I would like to offer to pray with patients (n = 39) I privately pray for my patients (n = 40) frequency frequency frequency Always or Often 3 3 12 Sometimes 10 14 21 Seldom or Never 26 11 of 12 MDs replied “NEVER”* 22 10 of 12 MDs replied “NEVER”* 7 2 MDs replied “NEVER”* *Each of these physician respondents had replied that spiritual care giving is an appropriate part of their professional role. Table 5. Spiritual caring as an appropriate part of role: when a patient asks for prayers. I do it myself I get someone else to do it I don’t follow through on their request frequency (n = 39) frequency (n = 43) frequency (n = 32) Affirmative (Always, often, sometimes) 30 26 7 Negative (Seldom or never ) 9 17 25  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 801 801 “Telling someone they are HIV positive.” “Watching the patients suffer with this terrible dis- ease.” “Being unable to alleviate or attenuate someo ne’s suf- fering, or unable to help a person find hope or peace in their life.” 3.5. Configuring the Spiritual Meaning of Suffering When asked what theological sense or ultimate meaning they made of the suffering of patients, none of the staff indicated a belief that the patients were being punished, whether for original sin, or the sins of a partner. Some saw causality based in ignorance regarding risk for con- tracting HIV (10). Some also selected the r epl y, “We liv e in an imperfect, fallen world” (12). The theological sense made of patient suffering was thought by only one respondent to be due to God wanting to teach a lesson; a small number (7) indicated that patients suffered because God had a plan. No clinic staff indicated that God wanted to punish patients or that, “The devil has a hold on this world”. However, many respondents believed, “God suffers with them” (26) as a way of making sense of the suffering. These included five physicians, nine nurses, the three social workers and nine of the support and administrative staff. This finding was statistically significant, (p = 0.018), meaning that clinic position category strongly predicted the response, “God suffers with them”. Specifically, nurses and support/administra- tive staff were more likely to respond that, “God suffers with them”, while physicians were more likely to state that, “God does not suffer with them”. Overall, 72.9% of respondents did not feel that there were other explana- tions for patient suffering; the remaining 27.1% felt the explanation was not listed. Those that believed other reasons explained patient suffering wrote open text re- sponses such as: “The answer to this is probably no t knowable.” “The world is not fallen but is imperfect.” “My role in care is to ameliorate suffering.” “Suffering allows redemption.” “We don't understand the mean ing of their suffering.” Of the seven female physician staff, five felt that God did not suffer with the sufferers, whereas the female nurses were more evenly split between believing God suffered with (5) and did not suffer with the patients (6). Female support staff was more likely to feel that God suffered with the patients (11). Most male physicians (13 of 16) felt God did not suffer, while of male nurses, two-thirds felt that God did suffer with patients. Several staff (12) indicated that, “There is no meaning to their suffering”, that, “God is not able to prevent such suffer- ing” (13), or that, “God chooses not to prevent su ch suf- fering to give us free will” (15). A smaller number of respondents (9) indicated that, “There are accidents in nature” as an explanation for why patients suffer. When asked about the suffering of the families and friends of those with HIV disease, 35.6% indicated that the families and friends suffered from the stigma associ- ated with the disease but nearly all (96.6%) rejected the idea of a punitive God, original sin, or the devil as hav- ing any role in this problem. Some thought the suffering might be part of God’s plan, that the world was imper- fect, that there are accidents in nature or that God could not prevent such suffering (15). Of these 15 respondents, nurses were the least likely to believe that God could not prevent such suffering. Some responden ts (14) indicated that, “God chooses not to prevent such suffering to give us free will”. As with the suffering of patients, more staff (39.0%) thought that God suffers with the families and friends of patients. Physicians, at 6.8%, were the least likely to reply that God suffers with families and friends of the patients. Asked what theological sense they made of their own suffering in caring for patients with HIV and their fami- lies/friends, only three respondents (a physician, a nurse, and a social worker) indicated that they did not suffer when caring for patients with HIV and their families or friends. All of the other respondents rejected the ex- planatory options of: God is punishing me, the devil has a hold on this world, or I suffer because of the social stigma of working with HIV patients. A few (6) indi- cated that they saw no meaning in their own suffering; (11) indicated that God cannot prevent suffering and the same percent indicated that God chooses not to prevent suffering to give us free will. The largest number of re- spondents (14) chose the option that, “God suffers with me”. When asked to choose a phrase that best expressed their attitude toward “you r own suffering in your work”, a few (7) opted for, “I personally do not experience suf- fering in my work”. In contrast, 52 chose other options. The largest response group (49) chose the option, “I cannot change the fact of human suffering but I can alle- viate it as much as possible”. No one chose the option, “I cannot change the fact of human suffering and there is nothing I can do about that”. The option, “I am willing to suffer to alleviate the suffering of others” was selected by (15); eleven of these were physicians, including six attending and four fellows, two were nurses, one was a social worker, and one was support and administrative staff, (p = 0.007). Physicians reported being more will- ing to suffer for their patients at 47.8% while the large majority of clinic nurses and administrative staff replied that they were not willing to suffer (88.2% and 89.5%, respectively) to alleviate the suffering of others.  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 802 4. DISCUSSION Rapid advances in biotechnology have been associated with longer survival and improved quality of living for many patients with HIV disease. Nonetheless, it remains a profoundly life-altering illness, challenging patients, families, friends and caregivers and causing suffering and anguish. Many Americans rely on religion as a cop- ing mechanism when they are seriously ill, including those with HIV disease [9,10] and those experiencing severe stress [11]. We speculated that staff caring for this patient population might also rely on spiritual and reli- gious frameworks to cope with doing this work and we wondered whether their self reports of well-being might reflect distress. This new survey data provides surprising and unexpected information about both areas of interest. Many staff members in this HIV clinic appeared in- vested in their spiritual lives and religious beliefs. The fact that 82% of them always, often, or sometimes prayed for their patients is telling, but this did not in- clude physicians, whose replies tended to be more secu- lar. Physicians in this clinic setting appeared to be less spiritual and religious, based on their survey responses, than their clinic coworkers and than American physi- cians in general. One in three reported having no reli- gious affiliation, whereas U.S. survey data indicate that one in ten physicians reported having no religious af- filiation [12]. Despite believing that spiritual caregiving was an appropriate part of their professional duties, these physicians often didn’t pray or want to pray for their patients. How these providers conceptualized spiritual care was not addressed in this study. The majority of clinic physicians (78%) believed that God did not suffer with the suffering patients, in marked contrast to the majority of support staff (69%) and nearly half of the nurses, who believed that God suffered with them, (p = 0.018). On the other hand, many of these physicians were willing to suffer to relieve the suffering of their patients, whereas the support and nursing staffs voiced opposition to this altruistic appro ach. Another interpreta- tion of physician responses might be that these responses represented complex reactions to the clinical setting of HIV disease, in “...a post-911 environment where spiri- tual issues of life and death have taken on a new urgency, but feelings about them are often ambivalent and diffi- cult to articulate” [13]. That the clinic nursing staff demonstrated a strong spiritual and religious orientation may be related to the fact that a core spiritual dimension exists in all nursing care, as taught by nursing scholars, who have studied spiritual and religious components within their profes- sion [14,15]. In addition to the spiritual orientation and care provided by the nurses, support and administrative staff in this HIV outpatient clinic emerged as an impor- tant resource for spiritual support and caregiving to pa- tients. They eagerly responded to patient requests for prayer and were highly compassionate about the plight of the patien t population. In fact, the support and ad min- istrative staff appeared to be key care providers for pa- tients, although not specifically recogn ized as such. An unexpected result of this research was that these healthcare providers and support staff consistently scored in the “moderate” range for religious and spiritual well- being, as well as existential satisfaction. In their work with patients with HIV disease, these care providers regularly face issues of mortality, the meaning of life, and theodicy. HIV clinic patients themselves may ask very difficult questions of staff; they have in common a chronic, complex, and potentially lethal illness, each with time to reflect on existential and spiritual issues [16, 17]. The relatively high spiritual well-being scores of the care providers in this study suggest that they may have successfully dealt with some of the aforementioned is- sues. They may have also benefited from decades of public education and technological innovation that have changed the environment for HIV treatment. Earlier re- ports documented job stress and fear of infection as fre- quent problems characteristic among healthcare workers caring for patients with HIV disease [18,19]. Distress among healthcare providers of patients with HIV disease and patients may have declined related to the success of potent therapeutics, especially HAART regimens [20]. Patients with HIV disease are living for much longer periods, with decidedly improved quality of life; these factors allow for qualitatively different relationships to be formed between staff and patients, about which much more could be learned. Compassion for patients was clearly evident in questionnaire answers and suppor ts the conclusion that humane, personal attachments develop between HIV clinic staff and patients, families and friends over extended periods of treatment and follow up. This continuity in positive relationships may explain some of the apparent job satisfaction and lessened sense of being oppressed by the actual patient work that was measured. The response rate of 78.8% to the survey was nu- merically robust, but the study was small and its findings may have been somewhat biased against secular results, in that the staff members who chose not to participate might be predicted to be unsympathetic to this subject area. A division appeared to exist between physicians who processed the difficulties of their work in a more secular manner and the strong component of spirituality and religiosity in the nursing and support staff of this HIV clinic. Whether the spiritual and religious reliance reported by these health care providers is linked, in a  E. A. Catlin et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 796-803 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 803 803 Marshall, G.N., Elliot, M.N., Zhou, A.J., Kanouse, D.E., Morrison, J.L. and Berry, S.H. (2001) A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 1507- 1512. causal rather than random manner, to the absence of measured spiritual distress, remains to be researched. This survey data points the way to further social sci- ence research, quantitative and qualitative, on the dif- ferent clinical con texts for treating pa tients infected with HIV. Of particular interest is the interplay of care pro- viders’ spirituality and religious beliefs and those of pa- tients with HIV disease, some from minority groups with strong religious traditions, [21,22]. But of greatest and global interest, clearly, would be achieving a cure for HIV infection [23], making possible a future world without HIV/AIDS [2]. [12] Curlin, F.A., Lantos, J.D., Roach, C.J., Sellergren, S.A. and Chin, M.H. (2005) Religious characteristics of U.S. physicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(7), 629-634. [13] Grant, D., O'Neil, K. and Stephens, L. (2004) Spirituality in the workplace: New empirical directions in the study of the sacred. Sociology of Religion, 65(3), 265-283. [14] Barnum, B.S. (1996) Spirituality in nursing: From tradi- tional to new age. Springer Publishing Company, New York. [15] Nagai-Jacobson, M.G. and Burkhardt, M.A. (1989) Spirituality: Cornerstone of holistic nursing practice. Ho- listic Nursing Practice, 3(3), 18-26. REFERENCES [1] Hariri, S. and McKenna, M.T. (2007) Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus in the United States. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 20(3), 478-488. [16] Ezzy, D. (2000) Illness narratives: Time, hope and HIV. Social Science and Medicine, 50(5), 605-617. [17] Siegel, K. and Schrimshaw, E.W. (2000). Perceiving benefits in adversity: Stress-related growth in women liv- ing with HIV/AIDS. Social Science and Medicine, 51 (10), 1543-1554. [2] Osborn, J.E. (2008) The past, present, and future of AIDS. Journal of the American Medical Association, 300, 581- 583. [3] World Health Organization. (2008) HIV/AIDS e stimates are revised downwards, http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/ EN_WHS08_Full.pdf [18] Horsman, J.M. and Sheeran, P. (1995) Healthcare work- ers and HIV/AIDS: A critical review of the literature. So- cial Science and Medicine, 41(11), 1535-1567. [4] (2008) Health, United States. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ data/hus/hus08.pdf [19] Sherman, D.W. (1996) Nurses’ willingness to care for AIDS patients and spirituality, social support, and death anxiety. The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 28(3), 205- 213. [5] Karasz, A., Dyche, L. and Selwyn, P. (2003) Physicians’ experiences of caring for late-stage HIV patients in the post-HAART era: Challenges and adaptations. Social Science and Medicine, 57(9), 1609-1620. [20] Hammer, S.M., Squires, K.E., Hughes, M.D., Grimes, J. M., Demeter, L.M., Currier, J.M., Eron, J.J. Jr., Feinberg, J.E., Balfour, H.H., Deyton, L.R., Chodakewitz, J.A., Fischl, M.A., Phair, J.P., Spreen, W., Pedneaulx, L., Nguyen, B.- Y. and Cook, J.C. (1997) A controlled trial of two nucleo- side analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. New England Journal of Medicine, 337(11), 725-733. [6] (2006) An Overview of Comprehensive HIV/AIDS Care Services. HIV/AIDS Palliative Care Guidance #1, in the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, U.S. Depart- ment of State, Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordi nator. http://www.state.gov/documents/organization/64416.pdf [7] Catlin, E.A., Guillemin, J.H., Thiel, M.M., Wang, M.L., Hammond, S. and O'Donnell, J. (2001) Spiritual and re- ligious components of patient care in the neonatal inten- sive care unit: Sacred themes in a secular setting. Journal of Perinatology, 21(7), 426-430. [21] Rapiti, E., Porta, D., Forastiere, F., Fusco, D. and Perru- cio, C.A. (2000) Socioeconomic status and survival of persons with AIDS before and after the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Epidemiology, 11 (5) , 496-501. [8] Ellison, C.W. and Smith, J. (1991) Toward an integrative measure of health and well-being. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19(1), 35-48. [22] Dray-Spira, R. and Lert, F. (2003) Social health inequali- ties during the course of chronic HIV disease in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS, 17(3), 283- 290. [9] Koenig, H.G., Larson, D.B. and Larson, S.S. (2001) Re- ligion and coping with serious medical illness. Annals of Psychotherapy, 35(3), 352-359. [23] Richman, D.D., Margolis, D.M., Delaney, M. , Greene, W. C., Hazuda, D. and Pomerantz, R.J. (2009) The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science, 323(5919), 1304-1307. [10] Tuck, I., McCain, N.L. and Elswick, R.K. (2001) Spiri- tuality and psychosocial factors in persons living with HIV. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33(6), 776-783. [11] Schuster, M.A., Stein, B.D., Jaycox, L.H., Collins, R.L., Openly accessible at

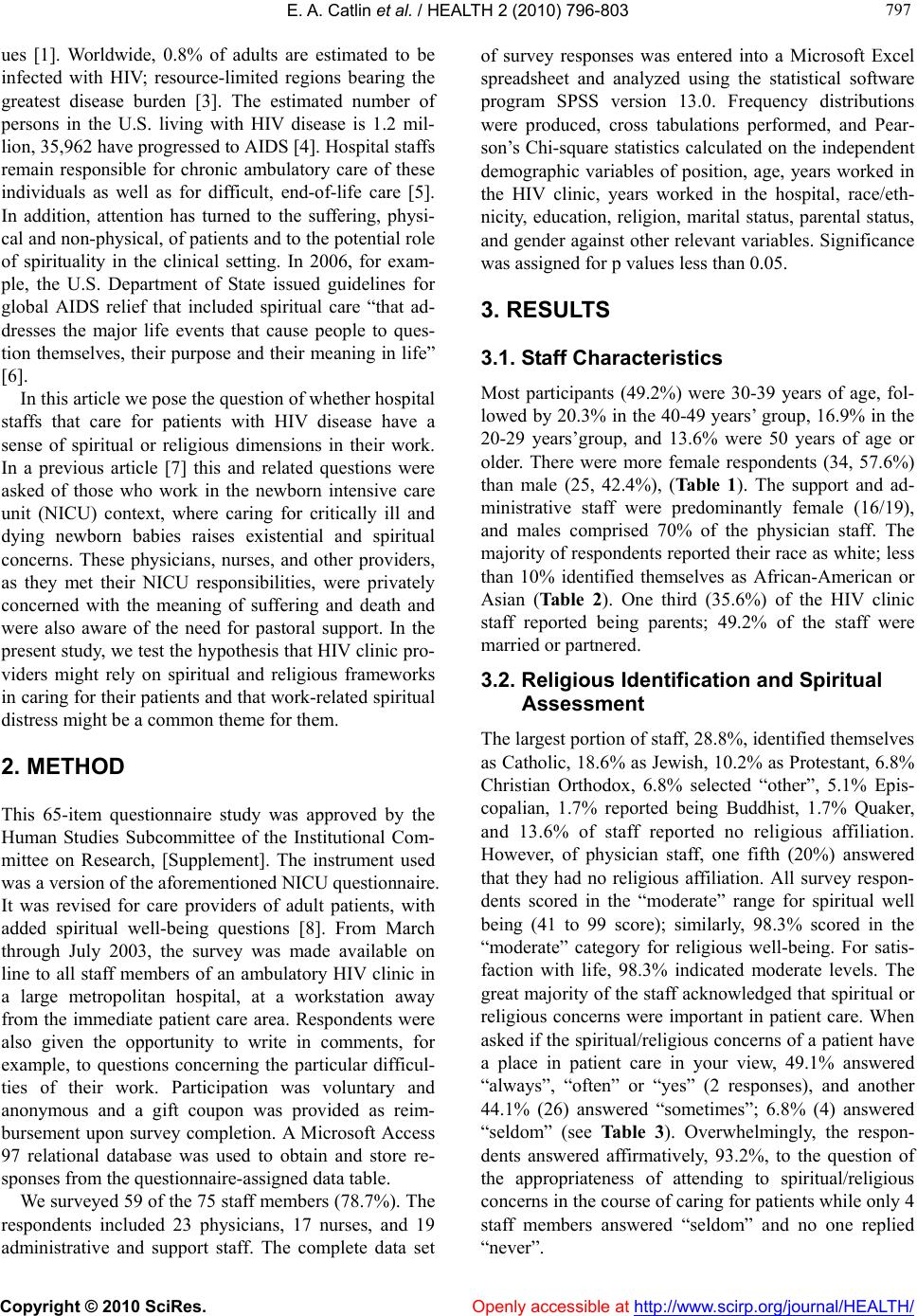

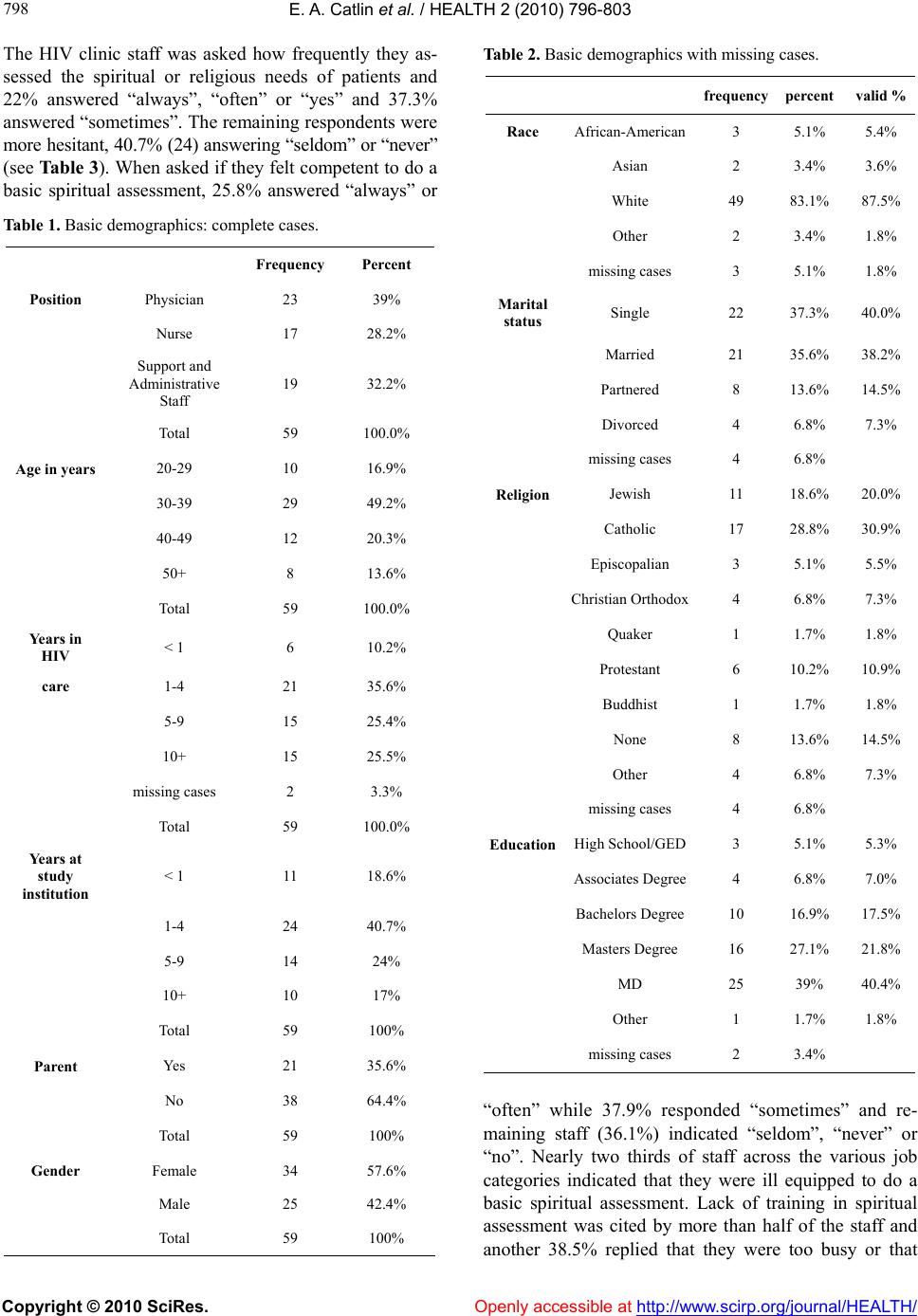

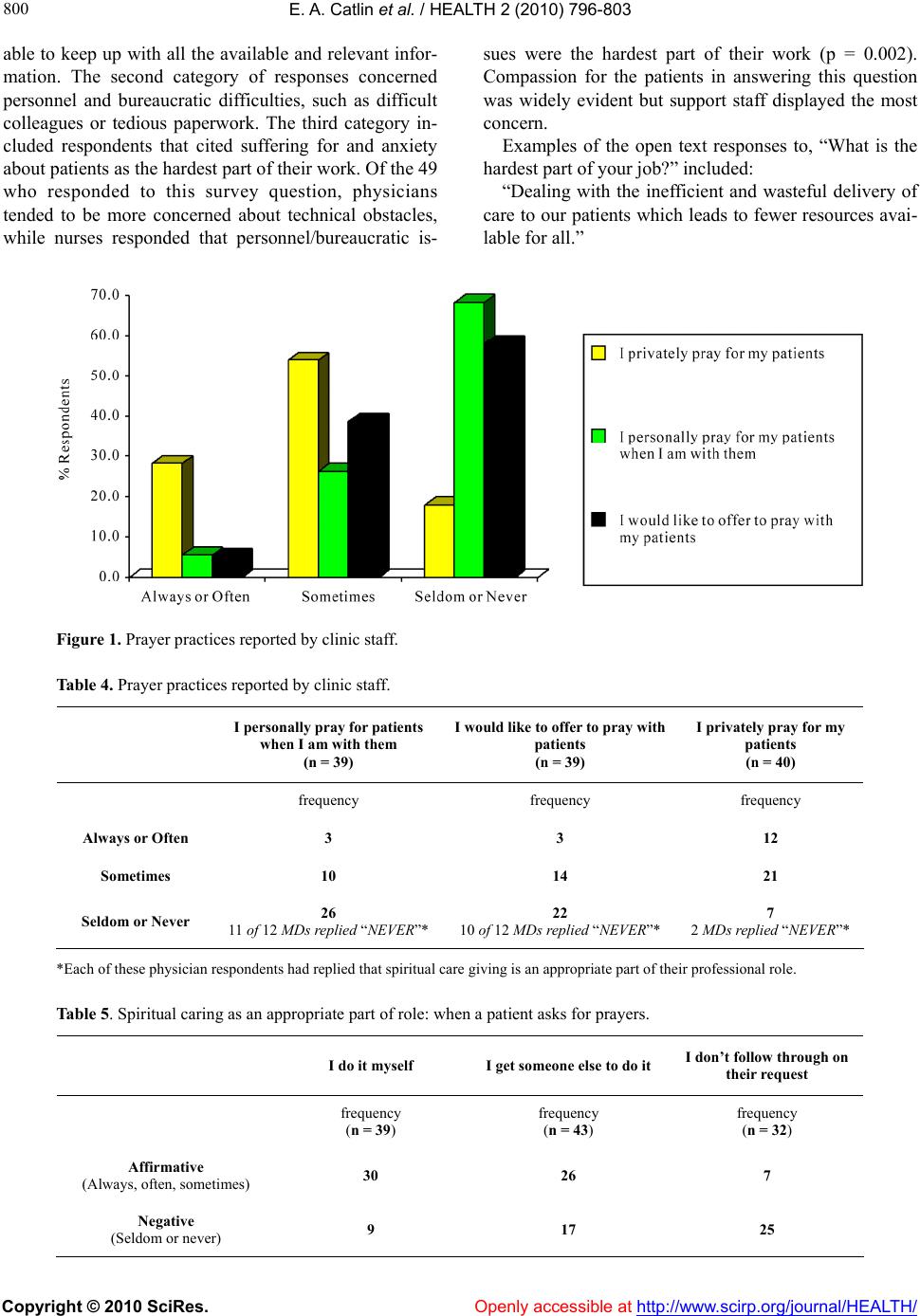

|