Vol.3, No.5, 651-657 (2012) Agricultural Sciences http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/as.2012.35078 Cassava sector development in Cameroon: Production and marketing factors affecting price Elise Stephanie Meyo Mvodo*, Dapeng Liang Business Administration, School of Management, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China; *Corresponding Author: mvodostephanie@gmail.com Received 12 July 2012; revised 18 August 2012; accepted 6 September 2012 ABSTRACT Regular and available supply is the prerequisite of an effective and efficient commercialization process. Using multivariate regression analysis on field data, this research appraises the pro- duction and marketing factors that influence cassava market price. The production factors include cultivated area, planting material, yield, and farmers’ field schools; while farmers access to a paved road, having a telephone, the trans- portation costs of fresh roots, the level of root perishability, and the prices of rice and maize stand as marketing factors. The results show that farmers who attended farmers’ field school adopted improved planting materials, propa- gated them in their localities and the yields in these communities increased significantly. The farm size also has a significant influence on the availability of fresh root s. On the marketing side, transport ation cost s, access to a p av ed road, the prices of rice and maize significantly affect cas- sava’s market price and tighten the relationship between producers and marketers. We conclude that to increase fresh roots supply, roads lead- ing to cultivating areas should be paved, better transportation provided, communication costs reduced, even distribution of planting materials and appropriate warehouses. Keywords: Production Factors; Marketing Factors; Cassava; Market Price; Cameroon 1. INTRODUCTION Literature reporting responsibilities’ allotment in a Bantu family prior and just after the independence states the man was the financial provider and in-charge of the hardest work. In rural areas, his activities scope was hunting for bush meat, fishing and picking. Additionally, he cultivated cash crops such as coffee, cocoa and rubber tree. He also took part in community farms and nation- building initiatives. The woman was in-charge of chil- dren’s education and housekeeping. She has to provide food, placing herself at the bottom line of the family diet manager. Women cultivated crops and exotic herbs for cooking and medicinal purposes; those crops that were considered as complementary with lesser economic im- portance were peanut, cassava, taro, yam, cocoyam, on- ions among others [1,2]. Women sold handful of those products on seasonal and weekly community markets for extra money usually without business objectives. The mid 80s crisis, The Breton wood institutions structural adjustments in early 90s and the country’s currency de- valuation in mid 90s made cash crop prices unpredictable and the government ceased to provide financial aids to farmers [3]. Many rural-farming households faced criti- cal financial down sloping and many coffee and cocoa farms were abandoned [4]. In addition, the increasing number of women in the intellectual arena, some with high-institutional positions (decision makers) and women empowerment initiatives contributed to the raising of a self-determined and powerful generation of women, with the quest of using what they have in order to upgrade their family’s living conditions. All these created market opportunities for many food crops, among which cassava holds an upright place, moving from a family food crop to a high financial return crop. Today, cassava is a major staple food and one of Cam- eroon top five crops. Cassava serves as raw material for more than 80 industrial products worldwide. It represents a delicacy, enabling the processing of many culturally appreciated recipes. Cassava is imperatively needed for human consumption, livestock feed and industries. Since independence, the production has tripled with an average production of 2,109,040 MT per year [5] still, the de- mand is hardly met. Nowadays, there are attempting ini- tiatives to reduce cassava process from field to the end user. Cassava sector embeds many business opportunities but lots of production are unexploited due to many in- adequate factors namely production, marketing, commu- nication and infrastructures. The most commonly identi- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. S. M. Mvodo, D. P. Liang / Agricultural Sciences 3 (201 2) 651-657 652 fied bottleneck to develop cassava market opportunities is the lack of a reliable supply [6]. Consequently, to have a permanent stock security, production and marketing factors have to be identified and upgraded. How can the sector’s production and marketing conditions improve? The main objective of this work is to evaluate the differ- ent factors influencing the sector’s supply and the com- mercialization process. 2. PRODUCTION AND MARKE TING FACTORS Cassava sector is a promising sector with many busi- ness opportunities; the main challenge is the mass supply of tuber roots that can satisfy human, animal and indus- trial needs. Cassava, as well as the rest of agriculture sector faces production and marketing limitations that significantly impedes the country’s overall economic growth and development. 2.1. Production Factors In Sub-Saharan Africa, agriculture is still germinal. The farm size along with yield rate per hectare is among the least in the world. The farming equipments are cut- lasses and hoes and the cultivated fields are small (65% less than 1 ha) that is mostly done by women; medium (25% around 5 ha), and communities farms (10% more than 5 ha). Lack of good planting materials and equip- ments, absence of mechanization and power, soil infertil- ity and land pressure are classified among the most re- corded constraints. The need for agricultural moderniza- tion cannot be overemphasized. The agriculture world needs improved production techniques, high yield, pest and diseases resistant planting materials (HYV) and ad- vanced equipments. High productivity has to be sup- ported by solid foundations i.e.; the creation of farm-to- market roads, the identification of markets outlets and the provision of better incentives to farmers [3,6,8]. Some limitations are usually not considered in studies however they can be useful in the attempt to understand critical elements of the behavior of sector’s actors; farm- ers lack coordination, they specifically lack initiatives and many do not take part in communities’ farms. Com- munity farms, practiced in inter-cropping can boost em- ployment and income creation. In addition, they repre- sent effective alternatives for biodiversity conservation and increase production at local and sub-divisional levels. The nuclear family members serve as the only source of labor where employable work force is highly required. The socio-economic factors analysis indicates that cas- sava as well as agriculture sector’s work force is aging, less educated and dominated by women. This situation in Cameroon is partly due to lack of motivation and ab- sence of youth farmer’s settlement scheme. Diseases such as mosaic, root rot, fungal rot and pests like whiteflies impede the yields. The replanting of af- fected planting material contributes to the propagation of the diseases on subsequent harvest. Fungal rot spreads faster in monoculture of cassava or when intercrops with cowpea [9,10]. Fortunately, in the study area, neither monoculture nor mixed cropping system with cowpea is practiced. Work done by [11] argues that researchers’ major limit is the failure to address post-harvest as well as the mar- keting phase of the cassava life shield. Recently, many researchers have focused on post-harvest processing and upkeep methods of cassava roots. The farmers’ field schools (FFSs) provide field trainers who educate famers on how to efficiently plant, grow, harvest and process cassava. They freely distributed (HYV). For an enhanced organization and coordination, trainers work in collabo- ration with farmers’ associations. Being a member of rural associations, attending public meeting and social events, belonging to an administrative committee, expo- sure to visits and training access, family size, children age and education level and information access are some factors that positively influence farmers to participate in training. Therefore, intensive awareness should be put in rural areas with the purpose of encouraging people to become members of agricultural cooperatives and take part in community development [3,6,12]. The production factors could improve significantly, but the sector cannot attain the objective of upgrading its activities if there are not appropriate means facilitating the roots availability on the market. 2.2. Marketing Factors Beside production constraints, other agriculture sec- tor’s constraints are infrastructures, consumer acceptance, transportation costs, the commodity type, the efficiency of transport and marketing sector, travel distance as well as small volumes, poor price information, commodity perishability, differences in storage and retailing [6,13]. The marketing system can be defined as a network of possibilities that enable a commodity [cassava] to move from producer to consumer through the large range of intervening actors in a least length of time. In Africa and particularly Cameroon, the routing net- work is limited: Cameroon has 77,588 kilometers of roads with only 5133 of them paved. They mostly link regional cities [14]; whereas farming communities dwell at divisional levels. Road plays a crucial role in the agri- culture and the transport of commodities. Therefor, dis- enclaving rural areas and making them accessible is fun- damental for economic development [3,13,15-17]. Tele- phone communication within the same vicinity is seven times more expensive than calling western or eastern Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. S. M. Mvodo, D. P. Liang / Agricultural Sciences 3 (201 2) 651-657 653 countries worldwide. Cameroon is 20% telephone cov- ered, but some rural communities face unsteady net- works. The cost of transportation represents another con- straint; since roads in their majority are not paved, transport societies and transportation equipments are limited. Transporters are scattered, old-fashioned cars coupled with high fuel prices escalate the problem. Tran- sportation costs represent the most expensive of the pro- duction costs. The rate of root deterioration depends to root cyanogens content and this affects its price. There- fore, the best way to upkeep cassava is to process it [15,17-23]. The work done by [17] affirms that, price depends on the location marketers and consumers ac- quire the commodity: on the farm side, road side, com- munity markets or on urban markets, while [6] sustain that harvesting age and root starch content are the main factors of price determination. In Cameroon, agricultural studies on crop factors’ im- pact are scarce. Researchers mainly focus on rice [24-28] and maize [29,30]. Studies on the cassava sector largely focus on traditional processing [15,17,21]. In addition, price mechanism and its determination have received less concern. The need to cover this gap is the driving aim of this study. The paper hypothesizes that: H0: Production and marketing factors do not affect the cassava’s market price H1: Production and marketing factors of cassava fresh roots do have impact on the market price. 3. METHODOLOGY 3.1. Study Area The study area is the Nyong and Mfoumou subdivi- sion. It is one of the ten subdivisions of Cameroon cen- tral region, located in the Southeastern part with Akono- linga as capital city. Farmers cultivate Cassava in inter- cropping farm system two times a year at the beginning of each rainy season. The region has equatorial climate with two rainy and two dry seasons. 1500 mm to 2000 mm of rainfalls recorded with temperature of 20˚ - 30˚. Data were collected in four phases; each phase consisted of the survey of one community made up of many vil- lages. Four communities were surveyed between June to September 2011. N = number of interviewees: Ayos (N = 26) in the south, Akonolinga 1 (N = 69) in the west, Ako- nolinga 2 (N = 40) in the east and Mengang (N = 111) in the north. There were not substantial processing units of cassava in the region, most cassava roots were either self-consumed (small farm) or sold on farm side, weekly community markets and urban markets. Due to very low population density, we targeted social gatherings in order to have enough and diversified respondents. These loca- tions include weekly-community markets (Saturday), after-service gatherings, holidays events such as football competitions, association meetings and cassava trade fair. There exist three transportation societies, which service Yaoundé every 1 - 2 hours while the informal cars, in degraded states, service villages sometimes at the rate of one time a week. The sub-divisional roads are not tared; the national road from Yaoundé to Bertoua facilitates the transportation of agricultural crops together with its inha- bitants. A total of 246 farmers among which 231 (94%) women were interviewed. Respondents were randomly selected and data collected using structured interviews. The main questions focused on the farm size: small ≤ 1 ha, medium ≤ 5 ha, communities > 5 ha. The possible out- comes were small = 1, medium = 2, small + community = 3, medium + community = 4. The yield: ≤11 tons/ha = 1, ≤30/ha = 2, >30 tons/ha = 3. Attendance to farmers’ field school, access to a paved road and having a mobile hand set were dummy questions (access = yes, otherwise = no). Estimated days before the appearance of yellow color on roots measured the perishability level. The ap- proximate transport costs of 50 kg of roots from their locations to Yaoundé. The usage of planting material was classified as exclusively local varieties = 1 exclusively high yield varieties = 2 and mixing varieties = 3. Un- structured interviews were use with some officials, FFSs trainers, ministry’s officials and heads of the National Programme for the Development of Roots and Tuber for complementary data. Cassava, rice and maize market prices were collected from the ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development 2011 food index prices (Table 1). 3.2. Model Choice Data were analyzed using multivariate regression model; this method is appropriate to test the influences of each individual factor on the determination of cassava market price. This method proves its usefulness as [6] used it to test the influence of determinants on cassava price and productivity in Indonesia. The model assesses the appropriate agricultural extension technological needs of users in cassava processing units in Nigeria [22]. Income and factors influencing the potatoes landrace production have been analyzed with this model [8]. The Table 1. Market prices of rice, maize and cassava. June July August September rice 400 350 300 375 maize 275 263 250 250 cassava 130 148 151 147 Source: Cameroon Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development price (in FCFA) indexes of food crop in Yaoundé-markets, 2011. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. S. M. Mvodo, D. P. Liang / Agricultural Sciences 3 (201 2) 651-657 654 factors affecting the job satisfaction of university lectur- ers in Zimbabwe were tested using this model [31]. Fac- tors affecting the adoption of fertilizer in rice production in Cote d’Ivoire were also studied by [7], using this model. 10 01 YnXn . (1) Subsequently, 01122334455 667788 99 1010. YXXXXX XXXX X (2) where: Y = Cassava market price (in FCFA); β = The regression parameter; µ = The error term; X1 = Cultivated area (in ha); X2 = Yield per 1 ha (in tons); X3 = Planting material; X4 = Farmers’ field school (dummy variable); X5 = Access to paved road (dummy variable); X6 = Access to telephone (dummy variable); X7 = Transportation costs of 50 kg of cassava (in FCFA); X8 = Level of perishability (in days); X9 = Price of rice (in FCFA); X10 = Price of maize (in FCFA). 4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Farm sizes are classified into 4 categories, 39% of in- terviewees grow cassava in small farms (less than 1 ha), among which 19% exclusively work in their farms while 20% (49 respondents) took part in community farms. Medium size farms are the result of some women re- ceiving additional help from their upbrings, family members and employable workers. While 34% exclu- sively cultivate their farms, 66 people from this group participated in community farms. In the survey area, many community farms were IFAD initiatives going hand in hand with FFSs training (Table 2). Improvements of farming techniques and yields increase motivate farmers to participate in those initiatives. Regarding yield results, the highest number of interviewees, 121 respondents reported having more than 11 tons per hectare. This was due to many factors: In the southern part of the region (Ayos), though they rejected the HYV, their production remains high, and this is credited to its soil fertility. Where FFSs took place, farmers adopted new practices and high yield, pest and diseases free planting materials. Varieties 82/34, 80/17, 92/3/26, 41/15 and 24/25 were freely distri- buted to participants (Table 2). They were allowed to sell those at 25 FCFA a stem to their community mates. Im- proved stems propagated as well as some planting and har- vesting techniques. The training took place for the full cassava production cycle [planting, weeding and harvest- Table 2. Cultivated area, yield and planting materials. % Number Cultivated areaa,b exclusively small 19 47 exclusively medium 34 84 small + community 20 49 medium + community 27 66 Total 100 246 Yieldsa less than 11 tons/ha 39 95 less than 30 tons/ha 49 121 more than 30 tons/ha 12 30 Total 100 246 Planting material exclusively local varieties 30 73 exclusively HYV 22 55 mixing varieties 48 118 Total 100 246 Source: authors’ field work 2011. aThe farm size and yield were reporting the last farm period i.e.: cassava planted at around March/April 2010 and harvested starting January 2011. bCommunity farm is exclusively associa- tions’ or local groups’. Partaking members own private farms, be it small or medium, they however occasionally attain community farms. ing] that is: one year, and results show that yields tripled. The varieties distributed are not only pest resistant, but also, mature rapidly. Farmers reported that the palatabil- ity and consistency of the new introduced varieties were better than the local ones. They produce more delicious leaves. Their roots are easy to boil and suitable to proc- ess into starch; but to make cassava puddings (bobolo and nkonda) local varieties are preferred. In addition, the local varieties have more fibers and can be maintained in the soil for longer period (more than 36 months), whereas the new introduced varieties rot rapidly. Close to Yaoundé, farmers were relatively young, they adopted appropriate techniques and HYV but their yield per hec- tare did not surpass 30 tons. The authors then conclude that production of over 30 tons/ha must be the result of the combination of fertile soil, use of improved planting ma- terials, use of work force and early whole cassava harvest (at around 11 months). The west and east parts of the region did not have FFSs due to impracticable roads and very low population density. Therefore, the use of HYV was very scarce in this part of the survey area, the high proportion of farmers using exclusively local varieties coupled with the southern part, which rejected the Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. S. M. Mvodo, D. P. Liang / Agricultural Sciences 3 (201 2) 651-657 655 HYV, are found in these localities. A total of 55 farmers admitted using only improved planting materials while 111 use both local and improved varieties. The northern, central and southern parts of the survey area had FFSs whereas the eastern and western part did not. The northern and central parts adopted the HYV, while the southern part rejected them. Some farmers from the western and eastern parts received HYV through family, acquaintances and alliances. The road from Yaoundé to Akonolinga is paved. The national tared road connecting Yaoundé to Bertoua largely ease the movement of people and the transporta- tion of commodities within that locality. Thus only 32% of the respondents have access to the road, the average transportation of 50 kg bag of roots from the locality to a randomly selected market in Yaoundé is 1107 FCFA ($2.5) whereas only 85 farmers had a mobile hand set (Tables 3 and 4). In some weekly community markets, roads inter- sections and food markets in urban centers, warehouses are built, nevertheless these are insufficient and unfur- nished. Four days is the mean time fresh roots can resist before getting yellow color. The highest number of days (5) is recorded on both HYV and local varieties depending on varieties. Sweet varieties rot quicker than bitter ones. Early maturity, sweetness and abundance of water were reasons of fast rotting (Table 4). Women associations, religious groups and weekly community markets were suitable places for collecting and sharing information since the population density in the region is among the least in the country. All localities dwellers did not attend FFSs due to the place where it was organized, the time of its organization, the famers’ availability, their perception on benefits and partner’s occupation or farmer-self other income activities, and whether or not they have children. The socioeconomic aspects of actors involve in the sec- tor was not our main concern. However, as [7,11,21,22] Table 3. Dummy variables. yes no % number % number (FFSs) 41 100 59 146 Access to paved road 32 78 68 168 Access to telephone 35 85 65 161 Source: authors’ field work 2011. Table 4. Transport costs and perishability level. mean range transport costsa 1107 [500, 2000] perishability levelb 3.85 [1.5, 5] Source: own survey 2011. aTransport costs are in FCFA; bPerishability level is in number of days. pointed out a precise understanding of the sector will be possible if actors’ level of education, age, gender, num- ber and age of children and activity of the partner are thoroughly analyzed. This may uncover some underpin- ning elements. There is a strong, positive and linear relationship be- tween the evolution of cassava market price and the con- sidered factors hence; we fail to reject the alternative hypothesis. R = 0.94, where 89% variations of the de- terminants affecting the roots’ market price derive from production and marketing factors; there is a highly strong effect between roots availability on the marketplace and price. The F-test is highly significant at P < 0.05 so F (10, 235) = 191.937, P = 0.000. Cultivated area and planting material factors signifi- cantly affect the production thus the market price (Table 5). It is obvious that since many cultivate small farms, increasing the farm size will increase the available dis- posable roots. In the same line of thought, farmers with the improved, high yield varieties, pest and diseases free planting materials will increase the fresh roots production. HYV increase yield per hectare and larger farm size in- creases acreages. This results in high quantities of fresh roots. Yield per hectare and FFSs do not influence the market price. Unquestionably, because the direct returns of FFSs are the distribution of planting materials and propagation of better farming techniques. Tared roads, cost of transportation, warehouses avail- ability and the price of substitutes (rice and maize) have significant impact on cassava market price whereas access to a mobile handset does not (Ta b le 6). Access to paved road not only shorten the transportation of commodities Table 5. Production factors affecting cassava roots supply. model standardized coef. t-value farm size 0.066 2.23 yield 0.027 1.11 (FFSs) 0.034 1.18 planting mat. 0.115 4.11 Table 6. Marketing factors affecting cassava price. standardized coef. t-value paved road −0.076 −2.75 telephone −0.007 −0.29 transportation −0.175 −4.932 perishability 0.072 2.566 rice −0.676 −21.38 maize −0.484 −15.909 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. S. M. Mvodo, D. P. Liang / Agricultural Sciences 3 (2012) 651-657 656 from farm to market, but significantly reduces costs. Farmers living alongside the paved road in the survey area reported selling substantial quantities of cassava, in front of their houses or on weekly community markets. Easily accessible community markets, with paved roads and bridges, where retailers and other sector operators pur- chase, have higher affluence. Only the transportation costs represent production costs and serve as price indicator for farmers of this region since it is quite difficult to price other production factors (land, labor, planting materials). As a result, the higher the price of transportation, the higher the cost of the commodity. Cassava roots rot quickly; consequently, it has to be processed immediately [15,17-23]. The perishability level measured by the ap- pearance of yellow lines on roots negatively influences market price. To gain a higher price, roots have to be fresh, white in color and fiber-free. Additionally, stores are not equipped with refrigerated system; hot temperatures (around 25˚) accelerate the rotting process. The prices of substitute rice and maize play crucial role on buyer’s decision, according to the demand-supply rule, the higher the price of substitutes, the higher the probability that the buyer will turn to cassava. Looking at the social perspec- tive, in a tight income revenue country e.g. Cameroon, a kilogram of rice/maize is likely to feed a family of 6 in a day, a result not achievable with a kilogram of cassava. Urban homemakers rather choose staple foods with less waste, easy to cook and to store with longer life span. Telephone did not affect the price of cassava. In Sub- Saharan Africa, communication is costly and information links are under developed among agriculture sector’s actors. In some rural localities, networks are unstable. 5. CONCLUSIONS Many industries in Cameroon need fresh roots of cas- sava to incorporate, either natural or in the form of modi- fied starch, in their production process. The development of the sector calls for an effective and efficient supply. Therefore, the production and marketing factors have to be carefully evaluated and improved. This paper con- firms that the size of the farm, the availability and the adoption of improved planting material play a critical role on root production. The agricultural sector rests on the hands of rural dwellers who perceive it only as their primary supply source of food, thus practicing it at a subsistent level; they lack adequate agronomy education or training. The cultivated area is reduced due to the non utilization of tractors, and improved technologies for planting, clearing or harvesting. The un-adapted policies, poor planting materials, pests and diseases, and lack of technology further deter the sector causing the yield to be minimal. At about 120 km from Yaoundé, the field inspection and data collection reveal that study area is not fully tared; this absence has a critical influence on transporta- tion, supply rate and the quality of roots. The absence of appropriate warehouses causes rapid deterioration of fresh roots and has remarkable impact on the market price. We concluded that appropriate warehouses in mar- kets will slow the deterioration process; more and better- tarred roads will ease the supply and communication costs and therefore, should be earnestly reduced. It was noticeable that cassava is a women cultivated crop, many upgrade their life with its mass production and process- ing, and this calls for a study of their socio economic aspects. REFERENCES [1] Vincent, J.F. (1976) Traditions et transition: Entretien avec les femmes Beti du sud Cameroun. L’Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre-Mer Nouvelle Série, 10, 166 p. [2] Anonymous (2012) Le role de la femme dans la famille Camerounaise. www.culturevive.com [3] Fonjong, L. (2004) Changing fortunes of government policies and its implications on the application of agri- cultural innovations in Cameroon. Nordic Journal of Af- rican Studies, 13, 13-29. http://www.njas.helsinki.fi/pdf-files/vol13num1/fonjong [4] Sonwa, D.J., Weise, F.S., Tchatat, M., Ousseynou-Ndoye, O., Adesina A.A. and Endamana, D. (2006) Adaptations of cocoa and coffee farmers’ communities in the heart of remnant pristine forest of east Cameroon to institutional changes. Landscape Ecology. ftp://190.144.167.33/Agroecosystems/incoming/manders on/Jenna%20ES%20Literature/Cocoa/Sonwa_et_al_2006 .pdf [5] Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organ- ization (FAO/WHO) (2005) National food safety systems in Africa—A situation analysis. Proceedings of Regional Conference on Food Safety for Africa, Harare, 3-6 Octo- ber 2005, 41 p. [6] Sugino, T. and Mayrowani, H. (2009) The determinants of cassava productivity and price under the farmers’ col- laboration with the emerging cassava processors: A case study in east Lampung, Indonesia. Journal of Develop- ment and Agricultural Economics, 1, 114-120. http://www.imamu.edu.sa/dcontent/IT_Topics/java/sugin o%20and%20mayrowani.pdf [7] Adesina, A.A. (1996) Factors affecting the adoption of fertilizers by rice farmers in Cote d’Ivoire. Nutrient Cy- cling in Agro Ecosystems, 46, 29-39. doi:10.1007/BF00210222 [8] Ogbonna, M.C., Anyaegbunam, H.N., Madu, T.U. and Ogbonna, R.A. (2009) Income and factor analysis of sweet potato landrace production in Ikom agricultural zone of Cross River State, Nigeria. Journal Development Agricultural Economics, 1, 132-136. http://academicjournals.org/JDAE/PDF/Pdf2009/Sept/Og Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS  E. S. M. Mvodo, D. P. Liang / Agricultural Sciences 3 (2012) 651-657 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OPEN ACCESS 657 bonna%20et%20al.pdf [9] Ntonifor, N., Braima, J., Gbaguidi, B. and Tumanteh, A. (1994) Whiteflies and whitefly-borne viruses in the trop- ics: Building a knowledge base for global action. Chapter 1.5, Cameroon. [10] Messiga, A.J.N.A. and Mwangi, M. (2004) Rots in Cam- eroon. The status of fungal tuber rots as a constraint to cassava production in the Pouma District of Cameroon. Proceedings of 9th Triennial Symposium of the Interna- tional Society for Tropical Root Crops—Africa Branch, Mombasa, 31 October-5 November 2004. [11] Nchang, N.R. (2007) Uncovering local understanding of cassava varietal selection Koudandeng—Obala, Camer- oon. http://www.geneconserve.pro.br/artigo036.pdf [12] Nugussie, W.S. (2010) Why some rural people become members of agricultural cooperatives while others do not? Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 2, 138-144. http://www.academicjournals.org/JDAE/PDF/Pdf2010/A pr/Nugussie.pdf [13] Hine, J.L. and Ellis, S.D. (2001) Agricultural marketing and access to transport services, rural transport knowl- edge base. Rural Travel and Transport Program. [14] Anonymous (2012) Le reseau routier camerounais. http://www.travauxpublics.gov.cm/index.php?option=co m_content&view=article&id=279&Itemid=113 [15] Boué, C. and Mauroy, E. (2006) Appui à la mise en place d’un atelier de transformation du manioc dans le District de Mboma, province est du Cameroun. Internship Report. [16] Aworemi, J.R. and Ilori, M.O. (2008) An evaluation of the performance of private transport companies in se- lected southwestern of Nigeria. African Journal of Busi- ness Management, 2, 131-137. http://www.academicjournals.org/ajbm/PDF/pdf2008/Au gust/Aworemi%20and%20Ilori.pdf [17] International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) (2008) Etudes sur les potentialites de commercialisation des produits derivés du manioc sur les marchés CEMAC. Initiative Régionale Pour la Production et la Commer- cialisation du Manioc (IRPCM). [18] Plucknett, D.L., Truman, P.P. and Robert B.K. (2000) A global development strategy for cassava: Transforming traditional tropical root crop—Spurring rural industrial development and raising incomes for the rural poor. [19] Nweke, F. (2004) New challenges in the cassava trans- formation in Nigeria and Ghana. www.ifpri.org [20] Djilemo, L. (2007) La farine de manioc (Manioht Escu- lenta Crantz) non fermentée: L’avenir pour la culture du manioc en Afrique. Atelier International du Manioc, 04 au 07 juin, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. [21] Essono, G., Ayodele, M., Akoa, A., Foko, J., Gockowski, J. and Olembo, S. (2008) Cassava production and proc- essing characteristics in southern Cameroon: An analysis of factors causing variations in practices between farmers using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). African Journal of Agricultural Research, 3, 49-59. http://academicjournals.org/ajar/PDF/pdf%202008/Jan/Es sono%20et%20al.pdf [22] Odebode, S. (2008) Appropriate technology for cassava processing in Nigeria: User’s point of view. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 9, 3. http://www.iiav.nl/ezines/web/JournalofInternationalWom ensStudies/2008/No3/bridgew/Cassava.pdf [23] Oluwasola, O. (2009) Stimulating rural employment and income for cassava (Manihot sp.) processing farming households in Oyo State, Nigeria through policy initia- tives. Journal of Development and Agricultural Econom- ics, 2, 18-25. http://www.academicjournals.org/jdae/PDF/Pdf2010/Feb/ Oluwasola.pdf [24] Molua, E.L. and Lambi, C.M. (2007) The Economic im- pact of climate change on agriculture in Cameroon. Pol- icy Research Working Paper Series 4364, The World Bank. http://www.ceepa.co.za/docs/CDPNo17.pdf [25] Molua, E.L. (2010) Response of rice yields in Cameroon: Some implications for agricultural price policy. Libyan Agriculture Research Center Journal Internation, 1, 182- 194. http://www.idosi.org/larcji/1(3)10/9.pdf [26] Molua, E.L. (2010) Rice production response to trade liberalization in Cameroon. Research Journal of Agricul- ture and Biological Sciences, 6, 118-129. http://www.aensionline.com/rjabs/rjabs/2010/118-129.pdf [27] Molua, E.L. (2010) Price and non-price determinants and acreage response of rice in Cameroon. ARPN Journal of Agricultural and Biological Science, 5, 3. http://www.idosi.org/larcji/1(3)10/9.pdf [28] Goufo, P. (2008) Rice production in Cameroon: A review. Research Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences, 4, 745-756. http://www.aensionline.com/rjabs/rjabs/2008/745-756.pdf [29] Franzel, S. (1999) Socioeconomic factors affecting the adoption potential of improved tree fallows in Africa. Agroforestry Systems, 47, 305-321. doi:10.1023/A:1006292119954 [30] Kafle, B. (2010) Determinants of adoption of improved maize varieties in developing countries: A review. Inter- national Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 1, 1-7. http://ecisi.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/1-71.pdf [31] Chimanikire, P., Mutandwa, E., Gadzirayi, C.T., Mu- zondo, N. and Mutandwa, B. (2007) Factors affecting job satisfaction among academic professionals in tertiary in- stitutions in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Business Management, 1, 166-175. http://www.academicjournals.org/ajbm/pdf/Pdf2007/Sep/ Chimanikire%20et%20al.pdf [32] Atemnkeng, T.J., Boboh, V.M. and Kenyi, M.D. (2010) Adoption of maize and cassava production technologies in forest-savannah zone of Cameroon; implications for poverty reduction. World Applied Sciences Journal, 11, 196-209.

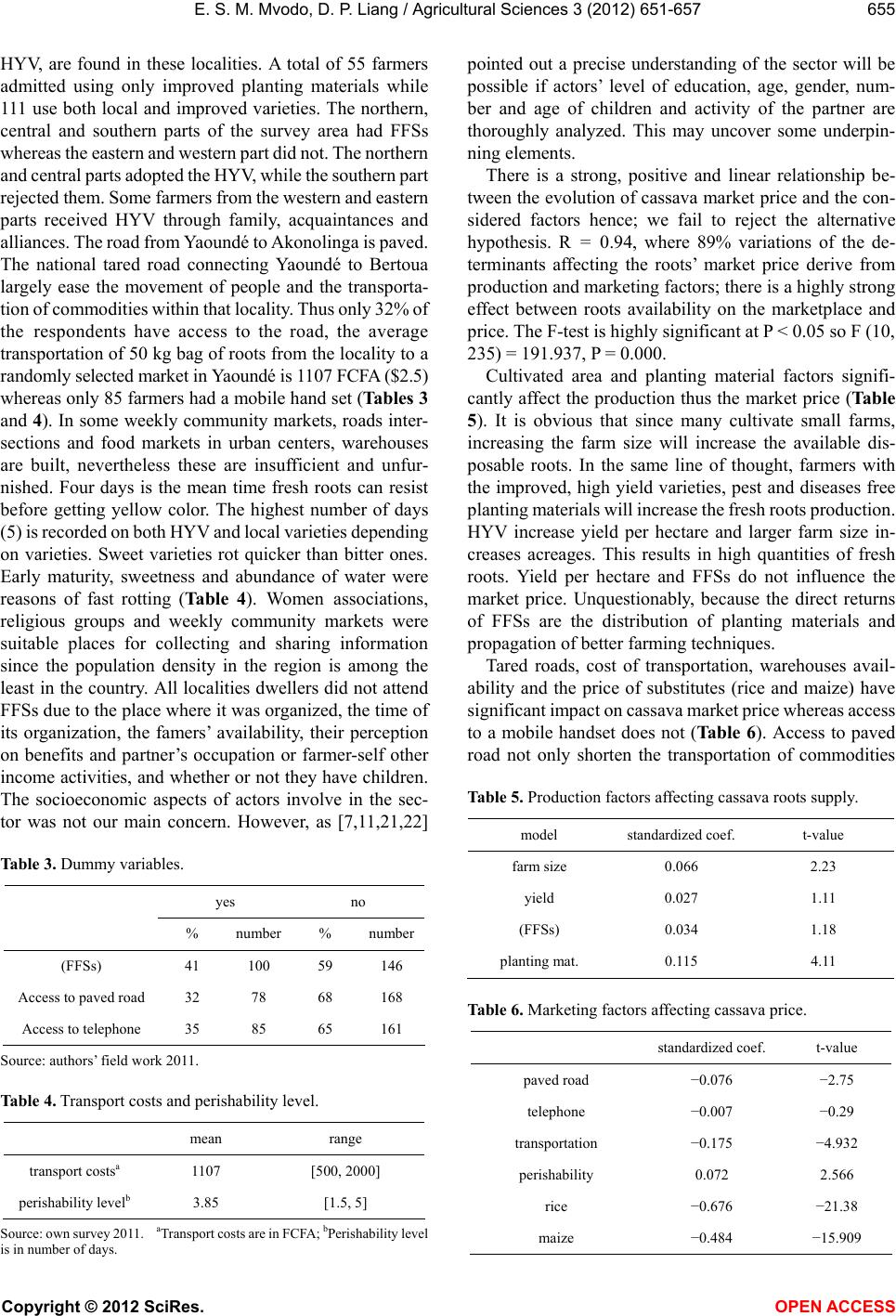

|