T. Ricon / HEALTH 2 (2010) 685-691

Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/

691

691

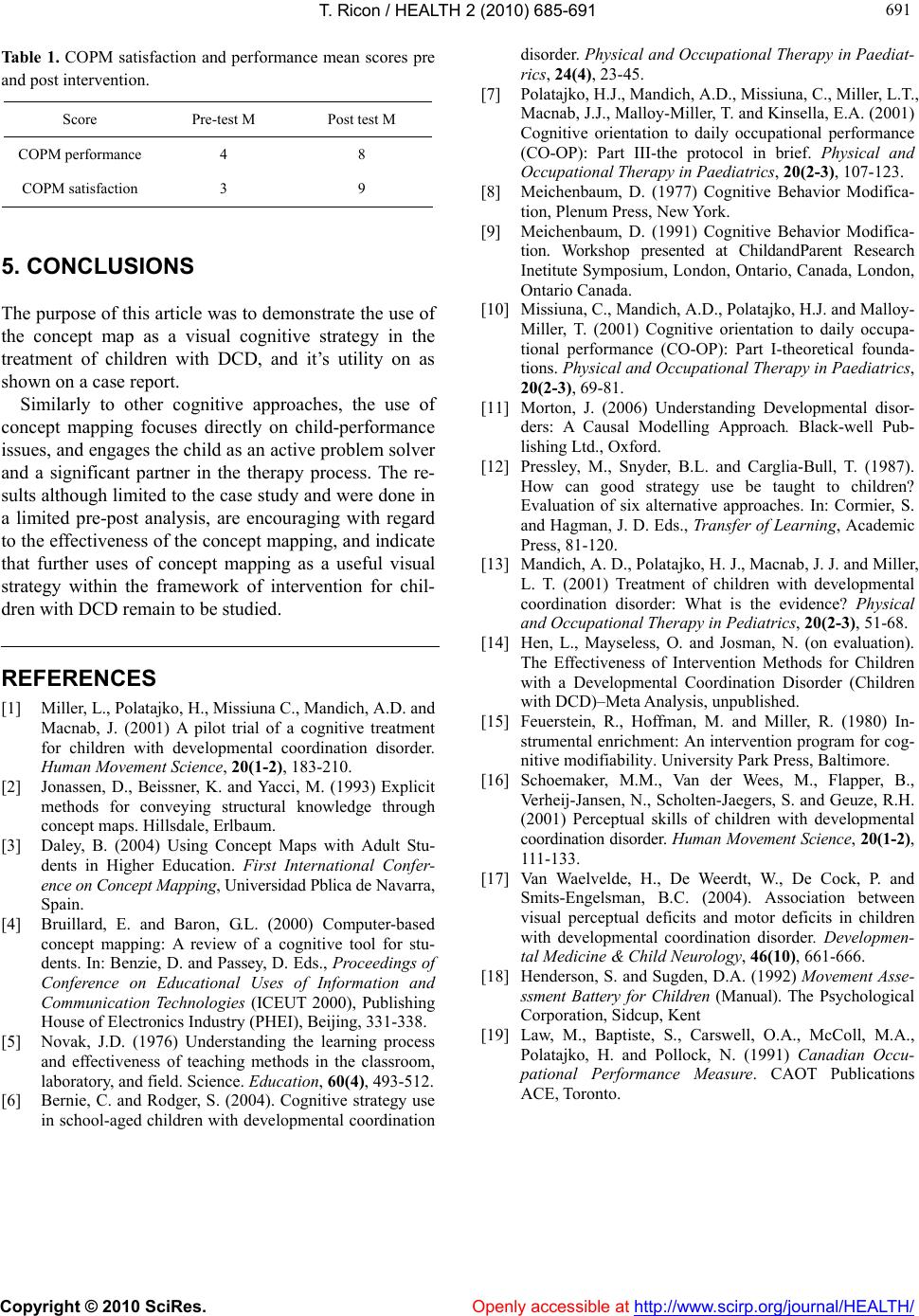

Ta ble 1 . COPM satisfaction and performance mean scores pre

and post intervention.

Score Pre-test M Post test M

COPM performance 4 8

COPM satisfaction 3 9

5. CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this article was to demonstrate the use of

the concept map as a visual cognitive strategy in the

treatment of children with DCD, and it’s utility on as

shown on a case report.

Similarly to other cognitive approaches, the use of

concept mapping focuses directly on child-performance

issues, and engages the child as an active problem solver

and a significant partner in the therapy process. The re-

sults although limited to the case study and were done in

a limited pre-post analysis, are encouraging with regard

to the effectiveness of the concept mapping, and indicate

that further uses of concept mapping as a useful visual

strategy within the framework of intervention for chil-

dren with DCD remain to be studied.

REFERENCES

[1] Miller, L., Polatajko, H., Missiuna C., Mandich, A.D. and

Macnab, J. (2001) A pilot trial of a cognitive treatment

for children with developmental coordination disorder.

Human Movement Science, 20(1-2), 183-210.

[2] Jonassen, D., Beissner, K. and Yacci, M. (1993) Explicit

methods for conveying structural knowledge through

concept maps. Hillsdale, Erlbaum.

[3] Daley, B. (2004) Using Concept Maps with Adult Stu-

dents in Higher Education. First International Confer-

ence on Concept Mapping, Universidad Pblica de Navarra,

Spain.

[4] Bruillard, E. and Baron, G.L. (2000) Computer-based

concept mapping: A review of a cognitive tool for stu-

dents. In: Benzie, D. and Passey, D. Eds., Proceedings of

Conference on Educational Uses of Information and

Communication Technologies (ICEUT 2000), Publishing

House of Electronics Industry (PHEI), Beijing, 331-338.

[5] Novak, J.D. (1976) Understanding the learning process

and effectiveness of teaching methods in the classroom,

laboratory, and field. Science. Education, 60(4), 493-512.

[6] Bernie, C. and Rodger, S. (2004). Cognitive strategy use

in school-aged children with developmental coordination

disorder. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Paediat-

rics, 24(4), 23-45.

[7] Polatajko, H.J., Mandich, A.D., Missiuna, C., Miller, L.T.,

Macnab, J.J., Malloy-Miller, T. and Kinsella, E.A. (2001)

Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance

(CO-OP): Part III-the protocol in brief. Physical and

Occupational Therapy in Paediatrics, 20(2-3), 107-123.

[8] Meichenbaum, D. (1977) Cognitive Behavior Modifica-

tion, Plenum Press, New York.

[9] Meichenbaum, D. (1991) Cognitive Behavior Modifica-

tion. Workshop presented at ChildandParent Research

Inetitute Symposium, London, Ontario, Canada, London,

Ontario Canada.

[10] Missiuna, C., Mandich, A.D., Polatajko, H.J. and Malloy-

Miller, T. (2001) Cognitive orientation to daily occupa-

tional performance (CO-OP): Part I-theoretical founda-

tions. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Paediatrics,

20(2-3), 69-81.

[11] Morton, J. (2006) Understanding Developmental disor-

ders: A Causal Modelling Approach. Black-well Pub-

lishing Ltd., Oxford.

[12] Pressley, M., Snyder, B.L. and Carglia-Bull, T. (1987).

How can good strategy use be taught to children?

Evaluation of six alternative approaches. In: Cormier, S.

and Hagman, J. D. Eds., Transfer of Learning, Academic

Press, 81-120.

[13] Mandich, A. D., Polatajko, H. J., Macnab, J. J. and Miller,

L. T. (2001) Treatment of children with developmental

coordination disorder: What is the evidence? Physical

and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 20(2-3), 51-68.

[14] Hen, L., Mayseless, O. and Josman, N. (on evaluation).

The Effectiveness of Intervention Methods for Children

with a Developmental Coordination Disorder (Children

with DCD)–Meta Analysis, unpublished.

[15] Feuerstein, R., Hoffman, M. and Miller, R. (1980) In-

strumental enrichment: An intervention program for cog-

nitive modifiability. University Park Press, Baltimore.

[16] Schoemaker, M.M., Van der Wees, M., Flapper, B.,

Verheij-Jansen, N., Scholten-Jaegers, S. and Geuze, R.H.

(2001) Perceptual skills of children with developmental

coordination disorder. Human Movement Science, 20(1-2),

111-133.

[17] Van Waelvelde, H., De Weerdt, W., De Cock, P. and

Smits-Engelsman, B.C. (2004). Association between

visual perceptual deficits and motor deficits in children

with developmental coordination disorder. Developmen-

tal Medicine & Child Neurology, 46(10), 661-666.

[18] Henderson, S. and Sugden, D.A. (1992) Movement Asse-

ssment Battery for Children (Manual). The Psychological

Corporation, Sidcup, Kent

[19] Law, M., Baptiste, S., Carswell, O.A., McColl, M.A.,

Polatajko, H. and Pollock, N. (1991) Canadian Occu-

pational Performance Measure. CAOT Publications

ACE, Toronto.