Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

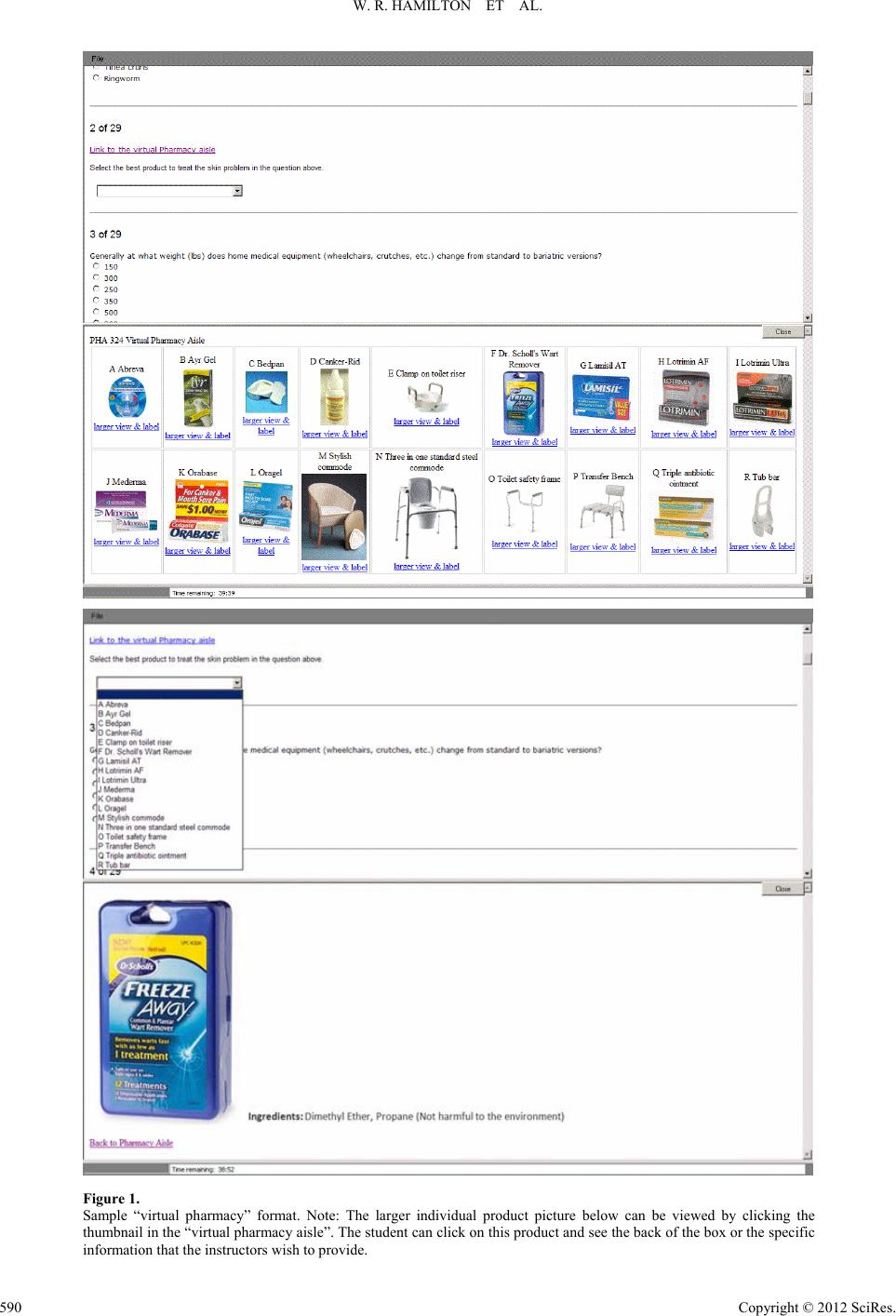

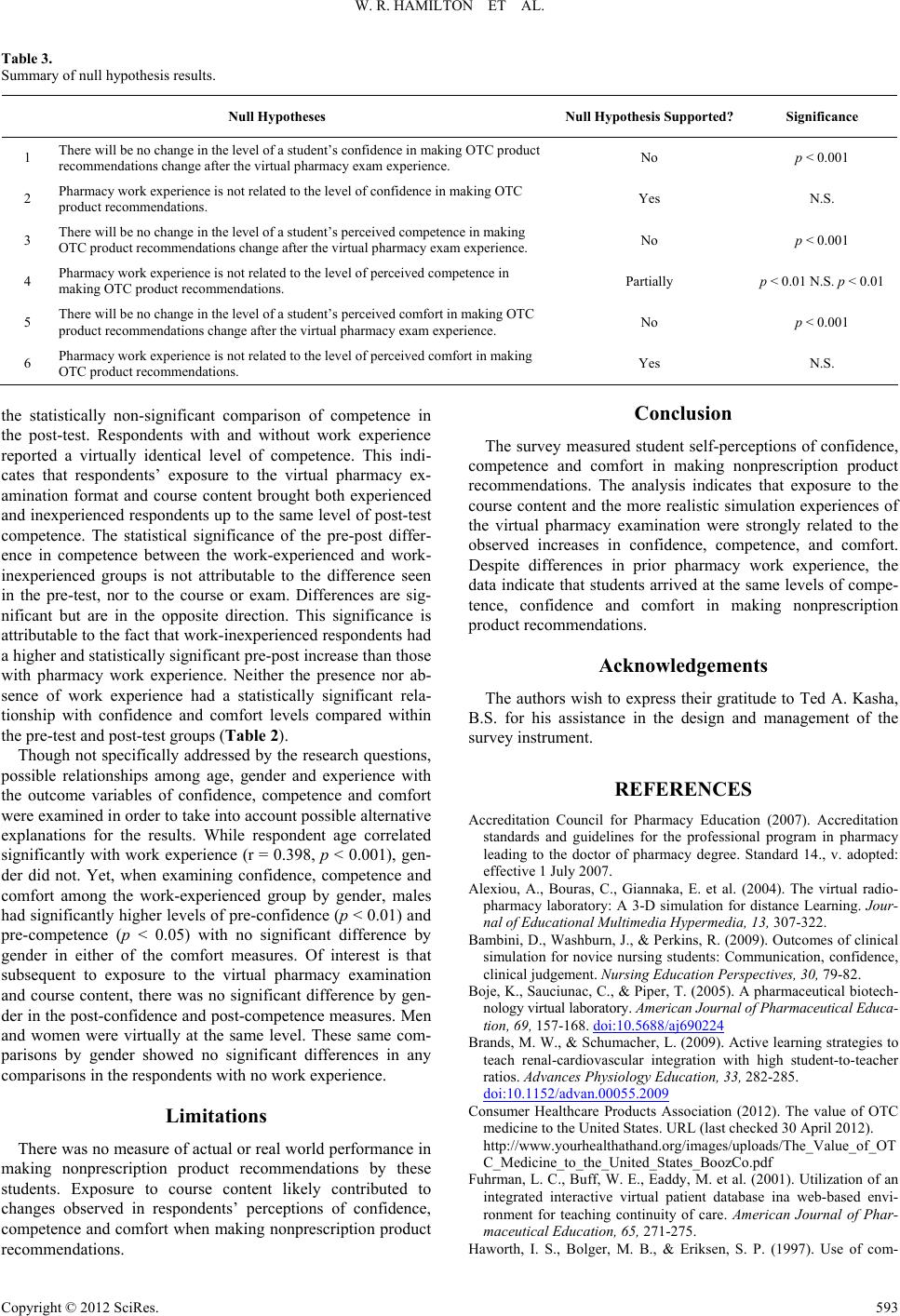

Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.4, 588-594 Published Online August 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.34086 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 588 A Novel Virtual Pharmacy Examination Format and Student Self-Perceptions in Making Nonprescription Product Recommendations William R. Hamilton1, Bartholomew E. Clark1, Victor A. Padrón1, Amanda L. Kelly2, DeDe A. Hedlund1, Mark V. Siracuse1 1Pharmacy Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, Creighton University, Omaha, USA 2Pharmacy Department, St. Luke’s Magic Valley Regional Medical Center, Twin Falls, USA Email: whamilton@creighton.edu Received June 16th, 2012; revised July 18th, 2012; accepted July 31st, 2012 Objective: Determine the impact of the virtual pharmacy examination on student perceptions of confi- dence, competence, and comfort when recommending nonprescription products. Method s : A pre-test post-test survey of student perceptions of their own confidence, competence and comfort following expo- sure to a “virtual pharmacy” examination was administered. Paired sample t-tests and independent sam- ples t-tests were used for pre-post comparisons where appropriate. Results: Analysis showed a pre-post mean increase of 1.25 on a 5-point scale (p < 0.001) for the 3-item subscale measuring perceived confi- dence in making nonprescription product recommendations. A single item for a pre-post comparison of perceived competence showed a mean increase of 1.45 on a 5-point scale (p < 0.001). Pre-post compari- sons of self-reported comfort in making nonprescription recommendations showed a mean increase of 0.49 on a 5-point scale (p < 0.01). Conclusions: The virtual examination format improved student per- ceptions of their own confidence, competence and comfort in making nonprescription product recom- mendations. Keywords: Virtual Simulation; Practice Simulation; Computer-Based Examination; Therapeutic Recommendations; Nonprescription Products; OTC Products; Pharmacy Work Experience Introduction Simulations have been used as learning and assessment tools since the 1960s and can take the form of an actor playing the role of a patient, mannequins with physiologic responses and the ability to communicate, virtual laboratories, virtual families, virtual examinations, and other computerized tools (Srinivasan, 2006). Universities currently face larger class sizes, distance learning, and the expectation to do more with less (Tompson, 2003; Sibbald, 2003; Alexiou, 2004; Brands, 2009). In health care education, students must not only gain knowledge, but also master clinical and personal skills (Kinkade, 1995; Schlicht, 1997; Fuhrman, 2001; Sibbald, 2003, 2004; Kiegaldie, 2006; Kluge, 2007; Orr, 2007; Tsai, 2008; Bambini, 2009; Brands, 2009; Paige, 2009; Kameg, 2010; Liaw, 2010). Simulations have commonly been useful as supplements in teaching com- plex concepts in pharmacology and pharmacokinetics (Li, 1995; Sewell, 1996; Haworth, 1997; Hedaya, 1998; Boje, 2005). Mannequin simulations have been used to develop communica- tion, assessment, and clinical skills (Bambini, 2009; Brands, 2009; Kameg, 2010; Liaw, 2010). Sibbald and Schlicht devel- oped virtual patient case studies (Schlicht, 1997; Sibbald, 2003; 2004). Orr enlisted the help of pharmacy faculty and residents who had prior community pharmacy experience to act as virtual patients; throughout the semester students would receive emails from their virtual patient asking them self-care questions likely to be encountered in practice (Orr, 2007). Fuhrman assigned virtual families to pharmacy students for whom they were to answer questions based upon what the students were learning in didactic lectures (Fuhrman, 2001). Kinkade developed a text- based computer program in which students made decisions on patients (Kinkade, 1995). Alexiou created a virtual laboratory designed for radioactive pharmaceuticals so people could work independently on experiments and techniques or to work col- laboratively (Alexiou, 2004). Boje created a virtual laboratory where students learned about the drug development process (Boje, 2005). Simulations can allow students to accomplish experiential learning in a relatively low risk environment (Schlicht, 1997; Tompson, 2000; Kiegaldie, 2006; Bambini, 2009). From using simulations, students felt that they improved their understanding of complex concepts, enhanced communi- cation and clinical skills, improved judgment, stimulated ana- lytical thinking, increased information retention, and improved self-efficacy (Haworth, 1997; Fuhrman, 2001; Sibbald, 2003; Boje, 2005; Kiegaldie, 2006; Kluge, 2007; Orr, 2007; Tsai, 2008; Bambini, 2009; Paige, 2009; Kameg, 2010; Liaw, 2010). In previous studies, students who learned with simulations scored higher than students who were taught with traditional methods (Fuhrman, 2001; Liaw, 2010). Overall, students reported that they felt the simulation ex- periences were beneficial, valuable, and relevant, and that they would recommend the simulation to other students (Sewell, 1996; Hedaya, 1998; Tompson, 2000; Sibbald, 2003, 2004; Boje, 2005; Kiegaldie, 2006; Orr, 2007; Tsai, 2008; Bambini, 2009; Brands, 2009; Kameg, 2010). However, the user-friend- liness of the simulation is a factor in how the students perceive  W. R. HAMILTON ET AL. simulations. In a study that used a simulation game that was not very user-friendly, students did not respond as favorably to this experience as did students in other studies (Kinkade, 1995). Current Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Guidelines stress an experiential educational model (Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, 2007). Yet many pharmacists learn about nonprescription products through a combination of personal use and some training and experi- ence after they graduate from pharmacy school (Consumer Healthcare Products Association, 2012). The authors propose that a component of the professionalization of pharmacy stu- dents should include knowledge of, and experiential training in, making nonprescription/over-the-counter (OTC) product rec- ommendations. Consistent with ACPE Guideline 11.2 under Standard 11: Teaching and Learning Methods, a virtual phar- macy examination assessment provides a closely guided simu- lation that mimics pharmacy practice in that “Active learning strategies include… simulations and other practice-based exer- cises.” (Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, 2007). With this challenge in mind, the instructors of the Nonprescrip- tion Therapeutics course (PHA 413) have employed pedagogi- cal strategies that require students to engage actively in making therapeutic decisions based upon course didactic content while not being limited to traditional multiple choice assessments. PHA 413 is a four-semester-hour required course offered to almost 200 students in the second professional year. Engaging such large classes in the application of knowledge from didactic content is a challenge. One way the course instructors ad- dressed this issue was by incorporating a “virtual pharmacy” component into the examinations routinely given in this four- credit-hour nonprescription therapeutics course. The term “vir- tual pharmacy” refers to a computerized simulation of the non- prescription products area of a community pharmacy. Students in the combination campus and distance-based class in the spring of 2011 were transitioning from being consumers of nonprescription products to becoming professionals who rec- ommend products to patients for a variety of health issues. The multiple choice examination format does not provide students with the same number of possible choices that they would have in a pharmacy. To solve this problem, we devel- oped a virtual pharmacy exam. The virtual pharmacy examina- tion contains images of numerous products that one would en- counter in an OTC aisle of the pharmacy. On the examination, the student is given a self-care question or issue and they must select an appropriate recommendation from numerous options. Product images are separated into different sections similar to the aisles one would find in a pharmacy, e.g. cough and cold products, gastrointestinal products. Although it would be possible to administer the virtual pharmacy examination in a paper version, the combination of: 1) students having laptop computers that allow them to take on-line examinations; 2) examination software, such as Ques- tion Mark®; and 3) a secure browser system provided an op- portunity to create and use a virtual pharmacy examination format. Creighton University pharmacy students have been issued laptop computers since the fall of 2000. Examination software is embedded in all the issued laptops. Examination software allows students to take examinations in any location with supervision by a proctor who oversees the student while taking the examination; results are immediately available for access by students and instructors. A secure browser allows students to log into the examination while it blocks any other computer use such as web surfing for answers. Students look at images of product packaging and labels, and then select what they conclude would be the best choice for a patient in a given situation. The virtual pharmacy is set up as a group of linked web pages. Examination web pages were au- thored by creating two views of each product, one large, one small with a third large view of the Drug Facts of each product. Naming conventions for image files were standardized (exam- ples VP01_ProductLarge_001.gif, VP01_ ProductSmall_001. gif, VP01_ ProductLabel_001.gif) as were label page names (VP01_Product001.html). Standardization of naming conven- tions allowed for use of an Excel® spreadsheet to create neces- sary names by changing the numerical portion of each file name by an increment of one. The mail merge function of Microsoft Word® was then used to create individual .txt files containing appropriate html code. File extensions were then changed to .html and pages copied to a web server. See Figure 1 for examples of examination questions and pictures. The main page represents shelves in a pharmacy and displays small pictures of various product packages. Clicking the small picture provides a larger picture of the front of the package. This process can be thought of as taking a product off the shelf. Clicking a larger image turns the package around to allow stu- dents to view the back where Drug Facts are listed. Returning to the main page can be thought of as putting a product back on the shelf to once again view all products available in the virtual pharmacy. Objective The objective of the study was to determine the impact of the virtual pharmacy examination format on student perceptions of confidence, competence, and comfort when recommending a nonprescription product. Null Hypotheses 1) There will be no change in the level of a student’s confi- dence in making nonprescription product recommendations after the virtual pharmacy examination experience; 2) Pharmacy work experience is not related to levels of con- fidence; 3) There will be no change in the level of a student’s per- ceived competence in making nonprescription product recom- mendations after the virtual pharmacy examination experience; 4) Pharmacy work experience is not related to levels of per- ceived competence; 5) There will be no change in the level of a student’s per- ceived comfort in making nonprescription product recommen- dations after the virtual pharmacy examination experience; 6) Pharmacy work experience is not related to levels of per- ceived comfort. Methods Survey Instrument De sign, Adm i n istration, and Validation A survey instrument was designed for electronic administra- tion. The instrument was composed of: 1) categorical demogra- phic items; and 2) likert-scale items designed to assess students’ self-perceptions of confidence, competence and comfort when making nonprescription product rcommendations (Figure 2). e Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 589  W. R. HAMILTON ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 590 Figure 1. Sample “virtual pharmacy” format. Note: The larger individual product picture below can be viewed by clicking the thumbnail in the “virtual pharmacy aisle”. The student can click on this product and see the back of the box or the specific information that the instructors wish to provide.  W. R. HAMILTON ET AL. Q#13. Have you ever worked in a pharmacy as an intern since you began pharmacy school? 1) Yes (If yes, please go to question 14) 2) No (If no, please go to question 16) Q#14. Please indicate the type of pharmacy (s) you have worked in as a pharmacy intern. Check all that apply. a) Independent community pharmacy b) Chain or other corporately owned pharmacy c) Hospital pharmacy—inpatient d) Nursing home or long term care pharmacy e) Home infusion pharmacy f) Nuclear pharmacy g) Pharmaceutical industry h) Pharmacy benefit manager i) Other (please specify) _____________________ Q#15. About how many total hours have you worked as a pharmacy intern since you began pharmacy school? ____ Q#16. Identify your pathway: Campus insert radio button Distance insert radio button. Q#17. Identify your gender: Male insert radio button Female insert radio button. Q#18. What was your age on your last birthday: ____ Pre-test and post-test survey instruments were administered to 182 students at the beginning and end of the semester. Con- firmatory factor analysis with Varimax rotation was used to establish validity of subscale composition. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determine subscale reliability. This study was considered exempt by the Creighton University Institutional Review Board. Results Of the 182 pre and post surveys administered, 168 students completed both (106 by campus students and 62 by distance students) for a usable response rate of 92.3%. Among these, for those who chose to answer the gender item, gender distribution was 107 females and 59 males. There were 122 respondents with pharmacy work experience and 46 with none. Paired sample t-tests and independent samples t-tests were used for pre-post comparisons where appropriate. Analysis showed a pre-post mean increase of 1.25 on a 5-point scale for the 3-item subscale measuring perceived confidence in making OTC recommendations (p < 0.001, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91). Confirmatory factor analyses with Varimax rotation and reli- ability analyses were conducted on the three-item scale meas- uring respondent confidence in making an OTC product rec- ommendation. For the pre-confidence analysis, of three com- ponents extracted, the primary component had an Eigen value of 2.579 explaining 86.55% of the variance. Reliability analysis for this subscale had a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.92. For the post-confidence analysis of three components extracted, the primary component had an Eigen value of 2.722 explaining 90.72% of the variance. Reliability analysis for this subscale had a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.95. A single item for a pre-post com- parison of perceived competence showed a mean increase of 1.45 on a 5-point scale (p < 0.001). A single item for a pre-post Instructions: Please indicate the extent to which you agree or disagree with each statement using the answer codes provided. Survey Items: Response Codes: 1 = Strongly Disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither Agree nor Disagree 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly Agree Q#01. I am confident in my ability to make a recommendation to a patient for use of a self-care product. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#02. I think I can do a good job when making a recommendation to a patient for use of a self-care product. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#03. I am confident that I can select an appropriate product in response to a patient’s request for a self-care product recommendation. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#04. The virtual pharmacy examination format used in this course is a realistic simulation of the types of problem solving a pharmacist engages in when making recommendations to a patient regarding self-care. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#05. The use of the virtual pharmacy examination in this course helped me to become more confident when making a self-care recommendation to patients. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#06. The use of the virtual pharmacy examination in this course has helped me to become more confident when making a self-care recommendation. Not used because it is a duplication of 5. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#07. I am currently competent to make self-care recommendation to patients. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#08. The use of the virtual pharmacy examination in this course helped me to become more competent to make a self-care product recommendation to a patient. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#09. I feel nervous when I make a recommendation to a patient for use of a self-care product. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#10. The use of the virtual pharmacy examination in this course has helped me to become less anxious when making a self-care recommendation. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#11. I like the virtual pharmacy examination format used in this course more than the traditional multiple choice examination format. 1 2 3 4 5 Q#12. The virtual pharmacy examination format used in this course is harder than the traditional multiple choice examination format. 1 2 3 4 5 Figure 2. urvey instrument. S Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 591  W. R. HAMILTON ET AL. comparison of perceived comfort in making nonprescription product recommendations showed a mean increase of 0.49 on a 5-point scale (p < 0.001). See Table 1 for comparisons by sub- groups. Comparisons based upon whether or not respondents had pharmacy work experience, showed significant differences only for comparisons of pre-test perceived competence (0.31 less for the group with no work experience, p < 0.05) and for post-test competence (0.43 less for the group with no work experience, p < 0.05), see Table 2. The negligible differences seen between responses of campus and distance pathway students were not statistically significant. Discussion Overall and within subgroups with and without work ex- perience, respondents’ levels of self-perceived confidence, competence and comfort in making nonprescription product recommendations increased significantly from pre-test to post- test, thus refuting the Null Hypotheses 1, 3 and 5. Of interest is that the presence or absence of work experience had no rela- tionship to these pre-post increases, thus refuting Null Hy- potheses 2, 4 and 6 vis-à-vis pre-post comparisons. Both groups showed increases in their perceived levels of confidence, com- petence and comfort in making nonprescription product rec- ommendations. Table 3 summarizes support and lack of sup- port for the null hypotheses. The presence of work experience does play a statistically sig- nificant role when contrasting pre-test levels of self-perceived competence, with the experienced group having statistically significant higher values of pre-test competence. Of note is Table 1. Pre-post comparisons. Null Hypotheses Addressed Comparisons via Paired Samples t-tests Mean (SD) N Mean Scale Difference Significance (2-tailed) 1 Pre Confidence—All 2.95 (0.88) N = 168 Post Confidence—All 4.19 (0.50) N = 168 1.25 p < 0.001 1 Pre Confidence—Work 3.03 (0.84) N = 122 Post Confidence—Work 4.20 (0.53) N = 122 1.17 p < 0.001 1 Pre Confidence—No Work 2.74 (0.96) N = 46 Post Confidence—No Work 4.16 (0.44) N = 46 1.42 p < 0.001 3 Pre Competence—All 2.62 (0.91) N = 168 Post Competence—All 4.07 (0.68) N = 168 1.45 p < 0.001 3 Pre Competence—Work 2.75 (0.91) N = 122 Post Competence—Work 4.07 (0.71) N = 122 1.32 p < 0.001 3 Pre Competence—No Work 2.28 (0.86) N = 46 Post Competence—No Work 4.04 (0.60) N = 46 1.76 p < 0.001 5 Pre Comfort—All 2.65 (0.91) N = 167 Post Comfort—All 3.13 (0.68) N = 167 0.49 p < 0.01 5 Pre Comfort—Work 2.69 (0.96) N = 121 Post Comfort—Work 3.07 (1.13) N = 121 0.38 p < 0.01 5 Pre Comfort—No Work 2.54 (0.91) N = 46 Post Comfort—No Work 3.28 (0.68) N = 46 0.74 p < 0.01 Table 2. Comparisons within subgroups: Work versus no work. Null Hypotheses Addressed Comparisons via Independent Sample s t-tests Mean (SD) N Mean Scale Difference Significance (2-tailed) 2 Pre Confidence—Work 3.03 (0.84) N = 122 Pre Confidence—No Work 2.74 (0.95) N = 46 −0.29 N.S. 2 Post Confidence—Work 4.20 (0.53) N = 122 Post Confidence—No Work 4.16 (0.43) N = 46 −0.05 N.S. 2 Post Confidence Diff.—Work 1.18 (0.81) N = 122 Post Confidence Diff.—No Work 1.42 (0.97) N = 46 0.24 N.S. 4 Pre Competence—Work 2.75 (0.91) N = 122 Pre Competence—No Work 2.28 (0.86) N = 46 −0.46 p < 0.01 4 Post Competence—Work 4.07 (0.71) N = 122 Post Competence—No Work 4.04 (0.60) N = 46 0.03 N.S. 4 Post Competence Diff.—Work 1.33 (0.83) N = 122 Post Competence Diff.—No Work 1.76 (0.85) N = 46 0.43 p < 0.01 6 Pre Comfort—Work 2.69 (0.96) N = 121 Pre Comfort—No Work 2.54 (0.94) N = 46 −0.14 N.S. 6 Post Comfort—Work 3.07 (1.13) N = 122 Post Comfort—No Work 3.28 (0.68) N = 46 0.20 N.S. 6 Comfort Diff.—Work 0.39 (1.33) N = 121 Comfort Diff.—No Work 0.74 (0.93) N = 46 0.35 N.S. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 592  W. R. HAMILTON ET AL. Table 3. Summary of null hypothesis results. Null Hypotheses Null Hypothesis Supported? Significance 1 There will be no change in the level of a student’s confidence in making OTC product recommendations change after the virtual pharmacy exam experience. No p < 0.001 2 Pharmacy work experience is not related to the level of confidence in making OTC product recommendations. Yes N.S. 3 There will be no change in the level of a student’s perceived competence in making OTC product recommendations change after the virtual pharmacy exam experience. No p < 0.001 4 Pharmacy work experience is not related to the level of perceived competence in making OTC product recommendations. Partially p < 0.01 N.S. p < 0.01 5 There will be no change in the level of a student’s perceived comfort in making OTC product recommendations change after the virtual pharmacy exam experience. No p < 0.001 6 Pharmacy work experience is not related to the level of perceived comfort in making OTC product recommendations. Yes N.S. the statistically non-significant comparison of competence in the post-test. Respondents with and without work experience reported a virtually identical level of competence. This indi- cates that respondents’ exposure to the virtual pharmacy ex- amination format and course content brought both experienced and inexperienced respondents up to the same level of post-test competence. The statistical significance of the pre-post differ- ence in competence between the work-experienced and work- inexperienced groups is not attributable to the difference seen in the pre-test, nor to the course or exam. Differences are sig- nificant but are in the opposite direction. This significance is attributable to the fact that work-inexperienced respondents had a higher and statistically significant pre-post increase than those with pharmacy work experience. Neither the presence nor ab- sence of work experience had a statistically significant rela- tionship with confidence and comfort levels compared within the pre-test and post-test groups (Table 2). Though not specifically addressed by the research questions, possible relationships among age, gender and experience with the outcome variables of confidence, competence and comfort were examined in order to take into account possible alternative explanations for the results. While respondent age correlated significantly with work experience (r = 0.398, p < 0.001), gen- der did not. Yet, when examining confidence, competence and comfort among the work-experienced group by gender, males had significantly higher levels of pre-confidence (p < 0.01) and pre-competence (p < 0.05) with no significant difference by gender in either of the comfort measures. Of interest is that subsequent to exposure to the virtual pharmacy examination and course content, there was no significant difference by gen- der in the post-confidence and post-competence measures. Men and women were virtually at the same level. These same com- parisons by gender showed no significant differences in any comparisons in the respondents with no work experience. Limitations There was no measure of actual or real world performance in making nonprescription product recommendations by these students. Exposure to course content likely contributed to changes observed in respondents’ perceptions of confidence, competence and comfort when making nonprescription product recommendations. Conclusion The survey measured student self-perceptions of confidence, competence and comfort in making nonprescription product recommendations. The analysis indicates that exposure to the course content and the more realistic simulation experiences of the virtual pharmacy examination were strongly related to the observed increases in confidence, competence, and comfort. Despite differences in prior pharmacy work experience, the data indicate that students arrived at the same levels of compe- tence, confidence and comfort in making nonprescription product recommendations. Acknowledgements The authors wish to express their gratitude to Ted A. Kasha, B.S. for his assistance in the design and management of the survey instrument. REFERENCES Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (2007). Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional program in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. Standard 14., v. adopted: effective 1 July 2007. Alexiou, A., Bouras, C., Giannaka, E. et al. (2004). The virtual radio- pharmacy laboratory: A 3-D simulation for distance Learning. Jour- nal of Educational Multimedia Hypermedia, 13, 307-322. Bambini, D., Washburn, J., & Perkins, R. (2009). Outcomes of clinical simulation for novice nursing students: Communication, confidence, clinical judgement. Nursing Educatio n Perspectives, 30, 79-82. Boje, K., Sauciunac, C., & Piper, T. (2005). A pharmaceutical biotech- nology virtual laboratory. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Educa- tion, 69, 157-168. doi:10.5688/aj690224 Brands, M. W., & Schumacher, L. (2009). Active learning strategies to teach renal-cardiovascular integration with high student-to-teacher ratios. Advances Physiology Education , 33, 282-285. doi:10.1152/advan.00055.2009 Consumer Healthcare Products Association (2012). The value of OTC medicine to the United States. URL (last checked 30 April 2012). http://www.yourhealthathand.org/images/uploads/The_Value_of_OT C_Medicine_to_the_United_States_BoozCo.pdf Fuhrman, L. C., Buff, W. E., Eaddy, M. et al. (2001). Utilization of an integrated interactive virtual patient database ina web-based envi- ronment for teaching continuity of care. American Journal of Phar- maceutical Education, 65 , 271-275. Haworth, I. S., Bolger, M. B., & Eriksen, S. P. (1997). Use of com- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 593  W. R. HAMILTON ET AL. puter-based case studies in a problem-solving curriculum. American Journal of Pharmaceu tical Education, 61, 97-102. Hedaya, M. A. (1998). Development and evaluation of an interactive Internet-based pharmacokinetic teaching module. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Educatio n, 62, 12-16. Kameg, K., Howard, V. M., Clochesy, J. et al. (2010). The impact of high fidelity human simulation on self-efficacy of communication skills. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31, 315-323. doi:10.3109/01612840903420331 Kiegaldie, D. (2006). “The virtual patient”—Development, implemen- tation and evaluation of an innovative computer simulation for post- graduate nursing students. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 15, 31-47. Kinkade, R. E., Mathews, C. T., Draugalis, J. R. et al. (1995). Evalua- tion of a computer simulation in a therapeutics case discussion. American Journal of Pha r m a ce u t i c a l Education, 59, 147-150. Kluge, M. A., Glick, L. K., & Engleman, L. L. (2007). Teaching nurs- ing and allied health care students how to “communicate care” to older adults. E d u c a t io n a l G e r o nt o logy, 33, 187-207. doi:10.1080/03601270600864082 Li, R. C., Wong, S. L., & Chan, K. H. (1995). Microcomputer-based programs for pharmacokinetic simulations. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 59, 143-147. Liaw, S. Y., Chen, F. G., Klainin, P. et al. (2010). Developing clinical competency in crisis event management: An integrated simulation problem-based learning activity. Advances in Health Sciences Edu- cation, 15, 403-413. doi:10.1007/s10459-009-9208-9 Orr, K. K. (2007). Integrating virtual patients into a self-care course. American Journal of Pha r m a ce u t i c a l Education, 71, 1-9. doi:10.5688/aj710230 Paige, J. T., Kozmenko, V., Yang, T. et al. (2009). Attitudinal changes resulting from repetitive training of operating room personnel using high-fidelity simulation at the point of care. The American Surgeon, 75, 584. Schlicht, J. R., Livengood, B., & Shepard, J. (1997). Development of multimedia computer applications for clinical pharmacy training. American Journal of Pha r m a ce u t i c a l Education, 61, 287-292. Sewell, R. D. E., Stevens, R. G., & Lewis, D. J. (1996). A pharmacol- ogy experimental benefits from the use of computer-assisted learning. American Journal of Pha r m a ce u t i c a l Education, 60, 303-307. Sibbald, D. (2003). Virtual interactive case tool for asynchronous learning and other self-directed learning formats. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Educatio n, 67, 144-152. Sibbald, D. (2004). A student assessment of virtual interactive case tool for asynchronous learning: Develop online resources for non-pre- scription drugs. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 68, 1-7. doi:10.5688/aj680111 Srinivasan, M., Hwang, J. C., West, D. et al. (2006). Assessment of clinical skills using simulator technologies. Academic Psychiatry, 30, 505-515. doi:10.1176/appi.ap.30.6.505 Tompson, G. H., & Dass, P. (2000). Improving students’ self-efficacy in strategic management: The relative impact of cases and simula- tions. Simulation Gaming, 31, 21-44. doi:10.1177/104687810003100102 Tsai, S., Chai, S., Hsieh, L. et al. (2008). The use of virtual reality computer simulation in learning port—A cath injection. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 1 3 , 71-87. doi:10.1007/s10459-006-9025-3 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 594 |