Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.4, 448-456 Published Online August 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.34069 Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 448 Reflective Collaborative Practices: What Is the Teachers’ Thinking? A Ghana Case Amoah Samuel Asare Psychology and Educa t i o n D ep a rtment, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana Email: asareamoahy@yahoo.com Received June 9th, 2012; r evised July 12th, 2012; accepted July 22nd, 2012 With advances in using the teachers’ classroom as the foreground for teacher improvement, reflective and collaborative activities provide teachers with a positive attitude towards questioning their teaching in a variety of professional development contexts. This study therefore explores how teachers within one school develop their thinking about their practices, if given an opportunity to engage in a planned series of critical dialogues relating to their own classroom teachings. Using a case study approach, four mathe- matics teachers purposely and through theoretical sampling techniques were selected in a school in Ghana for the study. The field research included interviews and reflective dialogue. Key issues identified include the opportunities to systematically and rigorously diagnose their practices leading to the development of different reflective scales when reflecting. The process was found to be a tool for supporting teachers to critically think which is underpinned by social, political and cultural issues as a process to analyze com- peting claims and viewpoints. Recommendations for policy and potential areas for further research were also made. Keywords: Reflective Collaborative Practices; Junior High School; Reflective Scales Introduction Even though reflective and collaborative practices have be- come one of the key principles underpinning teachers’ thinking about their practices as championed in the West, in the Ghana- ian context and most developing countries, such development is given less attention. In Ghana, efforts made to support teachers to understand their practices is seen to be instructive and prescriptive in na- ture (Acheampong et al., 2006) and overemphasizes on theory with little link to collaborative and reflective activities. It is within this contextual background that this study seeks to find out how teachers in Ghana, can develop better understanding of their practices, using their reflective and collaborative practices. Specifically the study seeks to explore how teachers within one school develop their thinking about their practices, if given an opportunity to engage in a planned series of critical dialogues relating to their own classroom teachings. This article begins with a brief literature review on the mean- ing and nature of reflective and collaborative practices. Brief profiles of the participating teachers are shared because find- ings seem to suggest that who they were and what the teachers did at the start of the study partly accounted for their contribu- tions during the reflective dialogue. Finally, the findings and possible implications of the findings of the study for teachers and teacher educators in Ghana and similar contexts are dis- cussed What Is Reflective and Collaborative Practice? Sharing of views within critical dialogue in reflective col- laborative activities in different context, positions one to make decision about what seems promising. According to Richardson & Placier (2001) teachers co-construct their understandings of innovations by informally collaborating and learning from each other as they reflect on their experience. Further, they claimed teachers perceive and draw on a variety of personal and profes- sional experiences, and other explicit knowledge to explain their professional performances. However, Jurasaite-Harbison and Rex (2010) think teachers have limited opportunities for interactions; hence they rarely engage in knowledge transfer. Reflective and collaborative practices are activities that support the interaction that locate discussions of an activity within the context of understanding and developing meaning to what is observed. Hatton and Smith (1995) have emphasized the following re- flection levels in reflective collaborative exercises; descriptive writing, descriptive reflection, dialogic reflection and critical reflection. The study was informed by the environment, socio- economic background and personal, reactive, emotional issues. Rarieya (2005) who used four teachers in the same school fo- cused her views as she explores and engages teachers to discuss their actions came out with reflections that hinges on noticing, making sense, making meaningful reflections, being transfor- mative in reflection. These support Sherin & Han, (2004) ideas which emphasizes on reflective dialogue, where the facilitator factor was very crucial. Thus within any reflective collaborative activities where participants move along different levels of reflection. The reflective differences result due to the methodo- logical and conceptual orientation adopted for the study. Reflective and Collaborative Processes Uptake: Sample and Instrument The study employed a qualitative case study approach and engaged four teachers from the same school. A typical school  A. S. ASARE site was reflexively selected in order to manage the context specificity to support authentic views of participants for the purpose of validity as suggested by Creswell (2009) and Bry- man (2008), even though Wainwright (1997) has raised some concerns about the typicality of a research site with regards to what constitutes a typical site. Access in the study has two sides. The first is the official permission which was negotiated for due to some privileges, and my prior knowledge that I thought could potentially be useful in the research process, informed my choice of the school. My familiarity with the school being used mostly for researches and the selection of teachers that I wanted to use in the study were students who afford me insights that generally may not be available for the decisions I will make about the data. Thirdly, the nature of the study required con- tinuous engagement of the teachers, as the study took place during the in-term period. Hence there was the need to consider the proximity of school to research environment for meeting places for convenience in order to stagger the research groups discourse in between the teachers’ formal teaching work, and fourthly to minimize the financial constraints involved while travelling. These characteristics helped me to select the school within my university environment. Having been given the permission from the District Educa- tion Officer (District head) and head of the school to use the selected school for the study, my next concern was to select teacher participants for the study. Mattessich et al. (2001, 2005) believe that in any collaborative activity, members involved need to review who to include, but in this study the responsibi- lity was on me to do the selection. In view of this, I decided on four criteria to help me to select the members. Firstly, the teachers needed to, on their own thinking, develop their own strategies to engage in a professional discourse about their teaching actions by setting their own agenda without taking instructions from me as well as for them to have explicit and unspoken control over relevant issues. Secondly, because it was a classroom-based study, I wanted to focus on the experiences within one subject area that I will be able to understand the processes mathematics teachers go through in reflective con- versation. Hence teachers teaching mathematics were consid- ered appropriate. Thirdly, the group needed to have the capacity to continuously monitor the activities and integrate into their plan the necessity to include new members if the need arose and finally the number needed to be not so large that the proc- ess of collaboration would become unmanageable due to the limited data collection period of six months. The only three mathematics teachers (all females) were ini- tially purposely selected with the help of the headteacher. These cohort of teachers for typicality (Creswell, 2003), were former students from the University of Education, Winneba. A fourth teacher, a male, through theoretical sampling techniques, was selected after the initial interview and feedback from my pres- entation at a seminar organised at the University of Education, Winneba. Issues related to collaboration, age and gender came out strongly from the transcripts of the initial interviews and suggestions from the seminar and this eventually led to the inclusion of another mathematics and science teacher to the sample. These four teachers had gone through two levels of teacher preparation institutions and were all teaching in the Junior High School levels at the selected school. The following four teachers were therefore selected to form the sample for the study. Profile of Cases Aggie: She is about twenty three years old mathematics teacher has been teaching in the school for three years before the study. As a class teacher and having attended some INSET activities, she thinks the facilitator factor and organizational challenges inhibit effective INSET activities. She cherishes the collaboration of colleagues for improvement as an alternative. Catherine: Catherine is about forty five years old who dis- covered her potential for teaching from her youthful days. As a resource consultant for INSET activities in the school district, she believes self assessment is the best option for looking at oneself in terms of effectiveness. She believes in the offer of suggestions and direct how to her suggestions during collabora- tive talk sessions with colleagues. Lydia: She is a twenty eight year old teacher and has been teaching in the school for four years. As a staff secretary, she thinks effective management of self is the cornerstone for every effective teacher. She believes in teachers co-switching be- tween teacher centred and child centred approach as teaching approach, and thinks relying on students comments collabora- tively support one’s self assessment. Oneal: Oneal, the only male in the study and twenty eight years. He once acted as the assistant head of the school and now a member of the schools’ sports committee. Oneal believes attending INSET programmes is good if done collaboratively with colleagues, however, the way it is organised creates pro- blems which inhibit teacher’s interest in attending such pro- grammes. Ethical Issues In order to identify significant problems or issue to any study and present a rationale for its importance (Creswell, 2003), informed consent, confidentiality and anony mity issues need to be addressed in researches. In the study, informed consent was necessary, because the participant were required to give out and engage in the frequent interactions in complex manner as sup- ported by Stark et al. (2006) who said when participants give their consent to a study, they are empowered rather than the researcher being protected; they are assured of anonymity and confidentiality in order to avoid any possible harm to them. In addition, it sought to avoid deception and harm (Heath et al., 2004). Even though, Heath, Crow, and Wiles (2004) have ar- gued that “informed consent is a largely unworkable process given that researchers can rarely know the full extent of what participation may entail, or predict in advance all the possible outcomes of participation” (p. 406). The Data Source The data sources for this study included individual inter- views and reflective dialogue on observed video playback of the teachers’ classrooms teaching actions. Seven steps sup- ported the data collection . The first step was a one-on-one interview. Data collecte d fo- cused on the teachers’ background information, their profes- sional development activities and their current practices in the school of the study. The second step was a trigger session where the teachers viewed and discussed two mathematics les- sons. This was to set the context of the RD process and which guided them to develop protocol for subsequent phases. The next step called the collaborative meeting helped the Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 449  A. S. ASARE teachers develop the following: Establishing a helpful and non-threatening environment for all activities in the intervention; Develop clear guidelines within which they are to operate; Decide how each of the teacher’s lesson was to be video- taped, the number of times and how to the reflective con- versations are to be organised on their videotaped lessons and; The development of parameters around which group dis- course would revolve around. The fourth step was the video capture. Participants decided on what lesson to be video captured, the day of the videoing, time an d lesson to be c aptured. Th is vide o capture wa s done on three occasions as agreed by the participants. The fifth step was the reflective conversation period termed the dialogue session. This phase included discussions on the video playback of the captured lessons. The sixth phase forms an overview session where the participants reflected on the video capture and the group discourse sessions with the seventh step, being an exit meeting which ends the RD process. Steps four, five and six are repeated on three occasions. Data Authentication and Trustworthiness In qualitative researches a way is needed to assess the “extent to which claims are supported by convincing evidence” (Silverman, 2006). To be able to authenticate the trustworthy- ness of data collected depends on how reliable or valid the sub- jective nature of discourse(s) is/are treated to ascertain the strength of interactions. Further, Yin (2009) thinks that “if a later investigator followed the same procedures as described by an earlier investigator and conduct the process all over again, the later investigator should arrive at the same findings and conclusion” (p. 45). Data was therefore authenticated after re- flection, based on three criteria advocated by Heikkinen, Hutunen, and Syrjala (2007) were adopted. These included, principle of reflexivity, and principle of workability. Principle of reflexivity, (Heikkinen et al., 2007) based on ideas on how researchers consciously reflect on their pre-in- sight or analyze their ontological and epistemological presump- tions, provided a better forum for the participants in the study. Even though, to present a particular reflexive account which is necessarily better in quality and being more truthful than any account is what is required in any qualitative study, “one cannot expect to know the ‘ultimate truth’ that corresponds exactly to an external truth” (Feldman, 2007: p. 28) is always a problem. But the RD process saw participants exchanging ideas, claims and counter claims to compare and contrasted plurality of per- spectives and used multiple realities, to develop understanding and knowledge. The principle of workability according to Heikkinen et al., (2007) is about how the quality of any interactions gives rise to changes in social actions. But Feldman was concerned with how equal value can be given to all interpretations by saying: Where there was the possibility to have desired outcomes, such as liv ely discuss ions or an attentio n to ethical problems th at draw upon unchallenged or false assumptions about race, eth- nicity, gender or sexual orientation that helped to maintain the status quo rather than leading to emancipation (p. 29). However, the study saw participants empowered and eman- cipated by way of developing their own ground rules and se- lecting the focus for the discussions. This saw how they criti- cally dialogued using plurality of perspectives to agree and disagree to develop consensus. The Methods and Data Collection Process Semi-structured interviews and the reflective dialogue (RD) gave the participants voice which challenged them to authentic- cate their opinions in a flexible environment Within the discussions, the participants listened, paid atten- tion to their cultural background, responded appropriately to each other’s views, respected and recognized the hierarchical arrangement of ages, as well as each others’ views, which de- pict their own cultural dimensions. The discussions focused on either subject content or pedagogy and as a focal point they either used specific examples or general knowledge about the observed action which they preferred, to advance their argu- ments. In addition, they often used their past experiences, cited literature or an already discussed issue to support their claims. The ability of the participants to recall or recount actions exhi- bited were supported by video playback actions of their teach- ings. At the outset of the RD, the environment was characterized but later it became cordial. Consensus building therefore was not easy. The start was characterized by tension and conflict coupled with judgmental remarks about their colleagues’ ac- tions resulting in confrontation as each put up strong defense for their actions. Changes in attitude, in relation to the softening of stance and the building of consensus manifested after the continuous and increased frequency in engaging with the inter- actions. Challenging Issues/Limitation Firstly, the views of the sample size of four participants ap- peared too limited to be used to generalize the findings. Sec- ondly, mechanical problems related to the video and audio data affected the transfer of the recorded data to another device for transcription. Thirdly, by using the grounded approach in the analysis, one issue of concern was data saturation. The informal dialogue within the RD and the use of the iterative process and multiple comparison methodology make it very difficult to completely exhaust dealing with all issues in the data. What is produced is solely the researcher’s own analysis showing how reflexive the researcher is. The next important factor was the limited resources and fi- nancial support for the study. Analysis Multi-case design employing the thematic approach was used to analyze the data collected. The study, a phenomenological one (Van Manen, 1989) allowed interpretation of the lived ex- periences. From the iterated process of reading and rereading the transcribed narratives from interviews, views were wrestled with and interrogated. The analyses were guided by the follow- ing questions: what changes were being observed to occur in words and phrases in the data that were pointing to how the participants were reflecting? How were they organizing their thoughts? How were they describing actions being observed? How were they interpreting what they observed? How were they being critical about what they saw? Both within case and Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 450  A. S. ASARE Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 451 cross case analysis formed the focus of the analysis. The par- ticipants’ way of re-categorizing issues of concern (within-case analyses) informed the cross- case analysis . Substantive comments from the data are used as templates to explain and justify claims made. The teachers’ use of their re- flective skills which were serendipitous and occurred without planning and forethought provided the underlying basic ideas in developing understanding as well as overcoming challenges they were confronted with. Results of the Study: Changes along Reflective Scales Extensive researches by Hatton and Smith (1995), and Rarieya (2005) in reflection and in-depth reflective dialogue with its descriptive characteristics informed the identification of the reflective scales. The analyzed data identified the following reflection shifts: judgmental to supportive, descriptive to criti- cal, unorganized to organized, and evaluative to interpretive reflections as found in Table 1. Deliberately Judgmental to Suppo rt ive Ref le ct io ns From the data analysis, issues on resolving the on-the-spot problems as they shared their views, the overarching behavior of the participants was seen to invigorate one’s reflection that epitomizes judgmental remarks about underpinning practices on observations made at first contact with such practice. For ex- ample expressing her opinion on Oneal’s first lesson, Catherine said: By your judgment how did you f ind your performance? To me it is no t the b est of performance because you did not impress me as a teacher. Oneal then replied, “I think I did well”. Catherine further said “always try to open up to tell us about your problems for us to be able to support you”. Whereas Catherine reflected on what she observed, the indi- cation is that she was also expecting Oneal to come out with his own reflections on his actions. Seeking clarification or justifi- cation in such a situation becomes a two-way affair between the observed and the observer. Any alternative offered, therefore, is dependent on the views expressed by the two participants. If such professional reflection can be shared through communica- tion, it is reasonable to conclude that participants try to deal with identified problems on the spot. As the process progressed, and after seeing and engaging in the critique of teaching actions, Catherine realized it was more rewarding to rather support colleagues with problems rather than making judgmental remarks when she said. I think we all need to support each other than to b e too critical about what we see to be better performance later on. Further Catherine realized emotional issues underpin some comments made when she said. I am really shocked about what you have said; I could ex- perience your sentiments and feelings behind your views. The study process suggests that the process trajectory seemed to offer an environment in which Catherine changed. Facilitat- ing factors that tend to help in the change process included making judgmental and suggestive comments coupled with being bold to challenge and pointing out faults. Further, judgmental and supportive way s are influenced by the human personal factors that include emotional sentiments. Here, issues related striving to accommodate varied perspectives, Table 1. Reflective scales and individual behavio rs. Reflective scales Participants/reflective comments What influenced shift Significant observed shift Judgmental Very instruct ive, seek for clarification, indif ferent to discussio n, questions teachers inability to manage lesson. Judgmental to supportive Supportive Empathet ic and offers options. Questioning the influence of cultural norms on be h aviors. Catherine Descriptive Recount w hat observed, raises probable factors and q uestions to observe, raises reasons to justifies occurrence of event. Descriptive t o critical Critical Offer and rel ate ideas on well structured actions that relate to sch ool/official education policy. Emphasizes deeper and critical analysis of events. Analytical views emphasize and relate ideas to socio-cultural issues. Using rhetorical questions to develop deeper analysis of events. Onael Unorganized Disjointed thoughts. Gives different explanations to same issue. Inability to make interpersonal comparison. Inability to sort out thought and views fro m others. Inability t o monitor what others said. Unorganized to organize d Organized Prefers specific order of pre sentation of idea, systematic and coherent presentation of idea. Cherishes sequencing of arguments. Organize , manage and monitor ideas commented by ot hers. Realizing and becoming aware of engaging in debate rather than being indifferent to activities. Lydia Evaluative Prefers consistency of ideas. Always concludes on initial attempts. Makes judgments based on thinking of what is right. Evaluative to interpretative Interpretative Prefer holistic mutually discussed issues. Self evaluation and advances id eas to other similar ob servation s. Asks for evide nces to all views to develop better understa nding. Pre fers giving thought to ideas well before responding. Focuses on formatively evaluating event rather than one step analysis. Was of the view that well managed self and activitie s is important t o understand practice. Aggie S ource: Data from reflective dialogue.  A. S. ASARE making better quality analyses and addressing challenges re- lated to emotional attachment underpinned supportive reflec- tion. Descriptive to Critical Reflections The analyses shows that the sustained interactions that took into account the nature of topic for discussions which provided more descriptive comments, social, political and cultural issues through the exploration of alternatives to resolve problems in professional situations provided critical reflection characterized the analysis . One issue that seemed to support the shift in reflection was about the emphasis placed on topics for discussion. Mono topic discussion, even though produced in-depth knowledge within the discussion on teachers’ practices, it also provide very real possibility to skew discussions. However, multiple topic dis- cussions, which sought to produce shallow knowledge as re- marked by Oneal, appear to be more descriptive towards bal- anced discussions on skills. Oneal felt: ... focusing on specific subject content with corresponding reasons to justify the deficiency observed in its applications is good, but descriptions are skewed and focused on only an aspect of the practices, on the other hand, when reference is made on pedagogical knowledge with accompanying reasons, descrip- tions cut across various techniques teachers adopt. The excerpt above clearly indicates that descriptive reflection can occur through multiple topic discussions. In support, Mat- tessich, et al. (2001) and Fielding et al. (2005) collaborative discussions are aimed toward providing in-depth understanding of issues. Oneal’s point therefore is important and I suggest that in order to avoid skewed understanding, recounting of events in practice needs to include more and wider discussion in order to have access to multiple skills and views. However as the dis- cussions progressed, use of rhetorical questions to seek justify- cations, and relating ideas to socio-cultural ethics of schools made the participants more critical in their comments. Sound- ing more critical about their teachings Oneal said. I think our discussions now have given us much information about our teachings but when we are discussing our practices, we need to know how school policy is directing us to teach espe- cially preparing them towards final examinations. This excerpt shows how he was now emphasizing policy re- lated to their practices. Oneal’s transition shows that in such discussions, individuals from the outset learn new things. However over time what is learnt gives them much more understanding of the various events that make them export what they have learnt to other situations. The continuous and systematic organization of ac- tivities saw Oneal, using rhetorical questions and self assess- ment to advance his arguments. Oneal’s shift indicates that invalidity and inconsistency in arguments characterised his actions from the outset. Illustrating this, Catherine remarked “We need to identify reasons that will make our claims more understandable”. Using questions like “What was not good about what you saw?”, “How do you think the teacher can ex- plain the subjec t matter well? ” and “What went well and why?” were what Catherine suggested could unravel reasons to justify her claims. Sustaining the questioning strategy was found to have re- sulted in the participants advancing their accounts to school policy. Significantly, their accounts on the deficiencies identi- fied were more on the difficulties in realigning their practices to their immediate school policies. This is confirmed by the fol- lowing statement made by Catherine. When discussing our practices we need justify any claim we make for effectiv e t ransfer o f ideas. T h is is what the edu cational policy is all about. If we do that I hope we will be able to know what to include in our lessons to ensure our students attain good grades at the end of their course since mostly the final examina- tions wants the students to display quality and thorough learning. Whilst it is evident that in reflective collaborative activities, participants descriptively and critically reflected on the prac- tices that were analysed, different factors influenced their shift processes. However, regardless of their analytical base, it would appear that the teachers seek out to develop deeper un- derstanding of their practices as well as processes that seem appropriate and relevant when developing the deeper under- standing. Rarieya (2005) has suggested that at the centre of discussing their practices, in the absence of sufficient reflective ability, the teacher will not be able to bring his or her knowl- edge to the appropriate professional lev el. Unorganized Reflection to Organized Reflections The data analysis saw the participants’ arguments generally inconsistent, unsystematic and incoherent from the outset of the discussions but later developed into arguments that were more systematic, coherent and consistent. Blurred thoughts on reflections seemed to influence one’s inability to sort out thoughts and views expressed by others. Such difficulty emanates from varied factors. One such factor is about the individual not reflecting on what was observed but on what ought to have been done. Exhibiting some behavior, Ag- gie said “What are we doing? Are we to observe and talk about the bad sides of everyone’s teaching or are we from the teach- ing actions to see where we can also make mistakes?” While Aggie did not question the way and manner issues were analyzed on what observed, as suggested by Hatton and Smith (1995), she questions the organization of the lesson con- tent and how it could be improved. She rather, emphasized what ought to have been done and what was done. Her actions provide basis for a well organized thought, that stem from or- ganization of thoughts that are consistently done when discuss- ing teaching actions. This coupled with other elements such as being well informed about what is being discussed, which sup- port Osterman and Kottkamp (1993) and Day (1999) who pointed out that, the act of engaging in discussing teaching activities with colleagues to understand their teaching actions is an indicator of reflection. Saliently from the study, thoughts expressed on an issue(s) from initial discussions sometimes were disjointed and in- grained with varied interpretations, however, with time, more organized thoughts were observed. The organized thoughts emanates from the presence of situations and the use of differ- ent professional perspectives as well as sharing existing knowl- edge and beliefs. In this way, through essential skills that are inconsistently, unsystematically and incoherently used can become more organized in thoughts when examined with peers. In conclusion, different types of knowledge that are inter- twined can be organized not according to type, but rather to the problem that the knowledge is intended to address as suggested by Gallimore and Stigler (2003). Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 452  A. S. ASARE Evaluation Reflection to Interpretative Reflection From the analyzed data, one finding was about how the re- spondents weighed competing claims and viewpoints of their own and others as they explored alternative solutions to issues raised regarding their performances. Issues on evaluative reflection to interpretive reflection, was drawn from Bennett (1999) and Matttessich et al. (2005) ideas which points out that the frequency with which participants within any collaborative group communicate their views pro- motes better understanding of issues discussed. However with effective support for the identification of inconsistencies, the individuals misapprehended issues under discussion in any collaborative activity. For example, Lydia prefers for “each one to assess what he/she hears and form his/her own opinion about what they heard”. She thinks “sharing such experiences with colleagues can motivate one to seek and ask for more information for clari- fication rather than presenting evidence that is not practicable”. The excerpt brings to fore one’s willingness to engage col- leagues in a collaborative endeavor where reflective views permeate such interaction to understand one’s teaching action which is worthwhile. Further Lydia emphasizes self evaluation of one’s own analyses of teaching actions. However, she thinks “this can be done if teaching activities are well organized and the analysis follows the manner in which the teaching actions are organ- ized”. Scrutinising her comments, she formatively re-assessed comments made by other colleagues and offered interpretations continuously. One difficulty she faced was when the judgments were based on opinions just like hers. Analyzing others’ opin- ion is what she claims “... very difficult to do since you cannot objectively verify it”. Her behavior in the interactions in the later stages indicates that she concluded every submission to any observed actions before explaining and interpreting how she evaluated the observed actions. To her, it is important to “let the people know the end product before you interpret how you got there”. In sum, it was more illuminating to evaluate before interpreting actions observed. Discussing the Facts abou t the Refle ctive Scales The views of all four respondents suggested that in reflection collaboration activities, participants begin to examine actions using their essential skills or generic competencies. This proc- ess seemed to support how teachers try to test their personal understanding of how they teach, how the activities influence what they do, the extent to which they think about the actions they observed indicating that the participants based their asser- tion on the technical knowledge as suggested by Schon (1987) on Technical Rationality. During the process, the participants based their reflections on their technical knowledge. The par- ticipants, in an attempt to resolve an identified problem or defi- ciency, used such skills knowledge to try to interpret what is acceptable. The teachers thus, carry out their analysis with the resulting behavior reflecting the possession of requisite skill which confirms Rareiya (2005) thought on RD. The teachers’ shift along the reflective axis suggests that teachers, in the process of their reflections, change the way they reflect over time. That is, the start of their reflection changes as they continue to en g ag e with reflect i ve a ctivities. On deliberative judgement reflection to supportive reflective, the underpinning idea hinges on the work of Schon (1987) that explains reflection-in-action and reflection-on-acti on. This means that during RD the two concepts go together (Rarieya, 2005). However Fook and Gardner (2007) state reflecting on a practice is finding a better way to practice. With the discussions, it al- lows teachers to resolve the on the spot practices to develop better understanding of their actions. Hatton and Smith (1995) think about effectiveness in such reflective processes is where each offer support to create different forms of reflection for exchange of technical ideas. This is done through seeking clari- fication and justification using questions to support colleagues. Again, judgmental and supportive reflections are influenced by human personal factor like emotional sentiments. However, in accommodating varied perspectives, the quality of analysis to address challenges underpin by emotional attachment can be managed. This hinges on individuals sharing of multiple per- spectives, hence they must be willing, ready and committed in engaging in continuous interaction in critical reflection to minimize emotional influence that inhibits their reflection (Fook & Gardner, 2007). Teachers are not just concerned with practices that will serve their instant goal as they engaged in structured discourse; rather they think about their broader purpose and practice in ways that support their long-term goals. This idea underpins McLaughlin and Talbert’s (2006) description about what teachers do when they engage in discourse about their teachings, is given much interpretation in the study where the multifaceted process en- couraged each of the participants to draw, simultaneously and selectively, from each others’ views to support their claims. Through utilizing multiple perspectives teachers are able to re-evaluate their fundamental assumptions (Fook & Gardner, 2007) about their teachings. There is thus, the connection be- tween individual’s personal experiences and the broader social context and how they are intertwined to influence the way one uses what he/she knows to what they do. Questions like why this behavior? What is the need to make my teaching more practical? Are some of the questions that promoted further inquiry resulting in issues connected to policy of a school and this support Schon’s (1987) view of reflection. Views that seemed to develop metacognitive skills and a belief or ideology (Hatton & Smith, 1995) being the goal of practice had to linked to socio-cultural or external policy of any institu- tion. This normally is not common occurrence in day to day interactions, however, as echoed by Hatton and Smith (1995) “critical dimensions need to be fostered from the beginning, for teaching is a moral business concerned with means and ends” (p. 46). Since participants’ voices in discussions are normally used to verify whether an action was good or not, individuals need to mull over, or tentatively explored reasons as to why an event happened, as championed by Hatton and Smith (1995) and Rarieya (2005). Unorganised reflection to organised reflection, emphases views that, the most difficult aspect for fostering reflective approaches is the eventual development of a capacity to under- take reflection-in-action. However, writers like Fook and Gar- dner (2007) agree that effective reflections depend on how ideas can be systematically and coherently organized. Through regular interactions, Rareiya (2005) also states that the teacher is better able to reflect in a sustained manner, when the teacher become open-minded, wholehearted, responsible, willing to take risks and has access to alternative ways of teaching, since they tend to use their “espoused theories” and “theories-in-use” Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 453  A. S. ASARE (Schon & Agyris, 1978) to organize their thoughts. It is worthy of note that organizing thought involve knowing what to evaluate and setting the criteria for evaluation (Minott (2006), citing James-Reid (1983), hence teachers need to deli- berately plan for evaluation as well as being empathetic (Slote, 2010). Such behavior which is a relational skill needed by teachers, will help them deliberately put themselves into the process of dialogue as this will create a trusting and safe learn- ing environment (Young & Gates, 2010). Creating such an environment will support one to “tune in” to what one is saying (McCann & Baker, 2001; Hutchins & Vaught, 1997; cited in Slote, 2010). This will enable one foster the ability to listen effectively and carefully. This is necessary because, “teaching is a complex interpersonal relationship, one in which human beings are not as separate as we often assume” (Markham, 1999: p. 59). Again the mood of the individual ac- cording to Comer (1980). Mood is a state of mind reflecting one's feelings at any par- ticular moment. Everyone has experienced their good and bad days. The dimensions of mood can influence our judgment of ourselves and those around us. They can influence how we react to situations. This situation will allow teachers to adapt covert behaviors, which could be detrimental or beneficial to any group discus- sions as they try to develop understanding of their practices (Rareiya, 2005). Even though it will be dangerous when such behaviors are not open to the group as members may find dif- ficulty when offering support or become disillusioned if they do not have access to such behavior. It is therefore crucial for teachers, according to Fook and Gardner to: ... model different ways of asking questions that might elicit further thinking and reflection for a person, as oppose to asking questions that might be more inclined to close persons’ thinking down, or impl ici t ly imp ose a way o f th in king rathe r th an invite a person to think it through for themselves (p. 97). Such a questioning strategy, without any force or pressure can help elicit information needed. Consequently, the study showed the uses of multiple strategies are therefore needed to elicit the appropriate information. In order to get organized, personal beliefs and behaviors, such as domineering and entrenching, need to be attended to since it turns to close down discussions. These behaviors pre- vent better conceptualization of principles of activities. This is what causes Hatton and Smith (1995) to posit that. It is widely acknowledged that from such a starting point which addresses the immediate and pressing concerns..., it is possible to move on to create learning situations which foster the development of more demanding reflective approaches, taking account of the factors which impact upon the practical context, often using the technical competencies as a first frame-work for analyzing performance in increasingly demanding situations (p. 46). Sustained discussions and persistence as found in the study, provide ways through which effective communication was possible. Individuals’ capability to deal with novel situations seemed to differ. Even though the intentional behavior of re- flection was tacitly being used, the honest, opened and objec- tive way in which views which were expressed made under- standing easy. Using such an atmosphere to gain experience cannot happen without conflicts, arising from offensive com- ments or conflicts and the provision of unclear statements re- sults in tense atmosphere cannot be ruled out. The reflective collaborative behaviors, as have been described by many au- thors, (Fook & Gardner, 2007; Osterman & Kottkamp, 1993; Sherin & Hans, 2004; Rareiya, 2005; Van Es & Sherin, 2008), tend to create tension and if not well managed may stifle shifts in reflection. Notwithstanding, consensus building can support to create an atmo s p h e r e conducive to discussion. There are suggestive evidences in literature that the impact of reflection-in-action. Reflection-in-action, as suggested by Schon (1987), enables an individual to compose a new situation in a continuous manner and enables one to develop a behavior which can be referenced to any time in the course of their work. This is normally what influences immediate responses where one unconsciously solves an identified problem. Conclusion The scales of the reflection rather portray that there are re- flective processes that can support teachers to understand their practices. Tacitly and latently, the participants traverse through scales of reflection which are informed by varied and peculiar factors. These factors may not be conclusive however they can support changes in reflection. While participants seemed to move through different reflec- tive scales as they dialogued, the shift was promoted by some factors. I argued that despite the inhibiting factors, some moti- vating and facilitating factors influence the shift. In other words, teachers should aim to be prepared to take risks, mutually share views and be prepared to accept criticisms collaboratively as postulated by Day (1999). However, addressing these needs required first addressing their existing personal and contextual constraints, which worked against the shift in the reflective scales. Implication of the Study for Teacher’s Education and Teacher Educator Reflection: A Tool for Understanding and Dealing wi th On-the-Spot Professional Problems As the participants reflected on the challenging factors, as well as their beliefs in practical knowledge and mood, they made decisions regarding how they could resolve any identified deficiency or faultlessness in their practices. These decisions and adjustments in turn influenced how they later reflected on the observed actions. Generally as they reflected during their discussion, they pre- sented analyzed views on the events observed. They then shared the views amongst themselves. Their mutually accepting and deciding on an alternative for any identified deficiency of faultlessness about an action made them to mutually support each other during the interactions. The process provided some insights into the nature of the in- terrelated support each gave to the other. The relationship re- garding recall and sharing of views actually provided evidence to how their reflection-in-action/discussion addressed their concerns after experiencing the arguments about their practices. In effect they went through the process by, as Hatton & Smith (1995) put it “contextualizing of multiple viewpoints” (p. 6). Reflection Supporting Critical Thinking That Include s Taking Account of Social and Political Issues Coyle (2002) provides an argument that to be able to reflect one need to emphasize that teachers take greater responsibility Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 454  A. S. ASARE for their own professional growth when this is set within their unique particular socio-political contexts, they can link their practice to policy or socio-cultural issues. Teachers therefore need to understand that they are not teaching for teaching sake rather their output is to fulfill a set objectives, be it national or local. This can be done if teachers share their views with col- leagues in their attempt to develop appropriate strategies to change their practices and move it to the realm of policy or set goals/objectives. This will enable teachers know that teaching itself is not only the transmission of knowledge, rather it is done to achieve a set national or local goal that needs to be discussed passionately with colleagues or through teamwork. Reflection Supports Systematic and Coherent Organization of Thoughts There was clearly the awareness of organizing thoughts sys- tematically and coherently through reflection to develop under- standing. Generally, participants try to examine how their es- sential analytical process could be organized in an order that will eventuate into developing better understanding. Doing so will give them a better process to uncover their unknown and unidentified skills. This means a reflection process is about “unsettling thinking and unearthing fundamental assumption about practice and to see how these are linked with actual prac- tice” (Fonk & Gardner, 2008). Therefore “examining one’s use of essential skills or generic competencies as often applied in controlled, small scale setting” (Hatton & Smith, 1995: p. 6) in any interaction can provide a better understanding of what hap- pens. Recommendation Linking Knowledge to Practice One issue that emerged from the study was about the ability of teachers to link their knowledge to their practice. In their quest for further investigation to see how effective the discus- sions had impacted on their classroom practice. Specifically the issue to be explored could include: How they can ensure such ideas are well implemented? What improvements are needed to ensure that professional support can help teachers implement their discussed ac- tions? What factors need to be considered when teachers engage in collaborative reflective dialogue on practices on the same issue? Are teachers to be given special training in how they col- laborate and reflect on specific issue on teachers practice? Strengths of the Research The in-depth exploration using four teachers provided rich and deep information where the teachers could learn new ways of understanding their practices. The second strength of this study was the way teachers con- currently engaged with the study and at the same time per- formed their normal teaching. The teaching actions used for the exercise were contemporary hence issues discussed were recent issues where ideas expressed were advanced into their class- rooms. The final strength of the research process was the benefit de- rived from getting an in-depth understanding of how teachers can reflect and collaborate. The interactions afforded me the opportunity to put into proper perspective the views of teachers concerning their practices. The main methodological limitation identified in the research process was what Maykut and Morehouse (1994: p. 155) refer to as the problem of reactivity. They pointed out that reactivity is a “term used to describe the unintended effects of the re- searcher on the outcomes of the research processes”. The first of such problems of reactivity was my position as a teacher educator. This was because the participants had the perception that I had answers to all their teaching problems. Regularly they sought my point of view when they were discussing their teaching practices. In response I always reiterated that I was also learning just as they were and I had to convince them that I needed their viewpoints to enable me get a comprehensive pic- ture of the issue. The second problem of reactivity arose from the perception of the participants that I had come to assess their teaching prac- tices. They therefore had an initial suspicion about my being part of the observation and discussions. Akyeampong (1997) reports of a similar problem during his field work in Ghana, which Marshall and Rossman (1999: p. 85) refer to as “Politics of Organisations”. This earlier signal helped me plan towards it by thoroughly explaining the rationale and purpose of the study and my role as a researcher and facilitator as suggested by Marshall and Rossman (1999) and Bens (2005). This position made me maintain good interpersonal relationship to disabuse their minds of any such suspicion. REFERENCES Akyeampong, K., Pryor, J. & Ghartey, A. J. (2006). A vision of suc- cessful schooling: Ghanaian teachers’ understanding of learning, teaching and assessment. Comparative Education, 42, 155-176. doi:10.1080/03050060600627936 Amoah, S. A. (2011). The reflective and collaborative practices of teachers in Ghanaian basic schools: A case study. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham: University of Nottingham. Argyris, C. & Schon, D. A. (1996). Organisational learning II: Theory, methods, and practice. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Com- pany. Bereiter, C. (2002). Education and mind in the knowledge society. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (3nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Comer, J. C. (1980). The influence of mood on student evaluations of teaching. Journal of Educational Resear ch , 73, 229-232. Coyle, D. (2002). The case for reflective model of teacher education in fundamental principles module. Nottingham: University of Notting- ham. Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Pub- lications. Day, C. (1999). Professional development and reflective practice: Pur- poses, processes and partnership. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 7, 2. Feldman, A. (2007). Validity and quality in action research. Educa- tional Action Research, 15 , 21-32. doi:10.1080/09650790601150766 Fielding, M., Brag, S., Craig, J., Cunningham, I., Eraut, M., Gillinson, S., Horne, M., Robinson, C., & Thorp, J. (2005). Factors influencing the transfer of good practice. Research Report, Falmer: University of Sussex & Demos. Fook, J. & Gardner, F. (2007). Practicing critical reflection: A resource handbook. Berkshire: Open Un iver sity Press. Gallimore, R. & Stigler, J. (2003). Closing the teaching gap: Assisting teachers to adapt to change. In Richardson (Ed.), Whither Assessment (pp. 25-36), London: Qualifications and Curr iculum Authority. Hatton, N. & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: To- Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 455  A. S. ASARE Copyright © 2012 SciRe s . 456 wards a definition and implementation. Teaching & Teacher Educa- tion, 11, 33-49. doi:10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U Heath, C., Crow, T., & Wiles, A. (2004). Analysing interaction: Video, ethnography and situated conduct. In T. May (Ed.), Qualitative re- search in action. L on d on: Sage. Heikkinen, H. L. T., Hutunen, R., & Syrjala, L. (2007). Action research and narrative: Five principles for validation. Educational Action Re- search, 15, 5-21. doi:10.1080/09650790601150709 Markham, M. (1999). Through the looking glass: Reflective teaching through a Lacanian le ns. Curriculum Inq u i r y, 29, 55-76. Mattessich, P. W., & Monsey, B. R. (1997). Community building: What makes it work. Saint Paul, MN: Fieldstone Alliance. McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). The contexts in question: The secondary school workplace. In: McLaughlin, M. W., Talbert, J. E., & Bascia, N. (Eds.), The contexts of teaching in secon dary schools. New York: Teachers’ College Press. Minott, M. A. (2006). Reflection and reflective teaching: A case study of four seasoned teachers in the Cayman islands. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham: University of Nottingham. Osterman, K. F., & Kottkamp, R. B. (1993). Reflective practice for educator: Improving schooling through professional development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corw i n Press Inc. Rarieya, J. F. A. (2005). Reflective dialogue: What’s in it for teachers? A Pakistan case. Journal of In-Service Educa ti o n, 31, 313-335. doi:10.1080/13674580500200362 Schon, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Fran- cisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Sherin, M. G., & Hans, S. (2004). Teacher learning in the context of a video club. Teaching and Teacher E ducation, 20, 163-183. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2003.08.001 Sil verman, D. (2006). Interpreting qualitat ive data. London: Sage Publi- cations. Slote, M. (2010). Reply to Noddings, Darwall, Wren, and Fullinwider. Theory and Research in Educati o n, 8, 187-197. Stark, L. J., Spirito, A., Williams, C. A., & Guevremont, D. C. (2006). Common problems and coping strategies: Findings with normal ado- lescents. Journal of Abnorm al C hi l d Psychology, 17, 203-212. doi:10.1007/BF00913794 Taggart, G. L., & Wilson, A. P. (2005). Promoting reflective thinking in teachers. Thou s a nd O a k , CA: Corwin Press. UNESCO Principal Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCO PROAP) (2000). Increasing the number of women teachers in rural schools. Bangkok: UNES CO PROAP. Van Manen, M. (1995). On the epistemology of reflective practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theor y and Practice, 1, 33-50. Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). London: Sage Publ i cations.

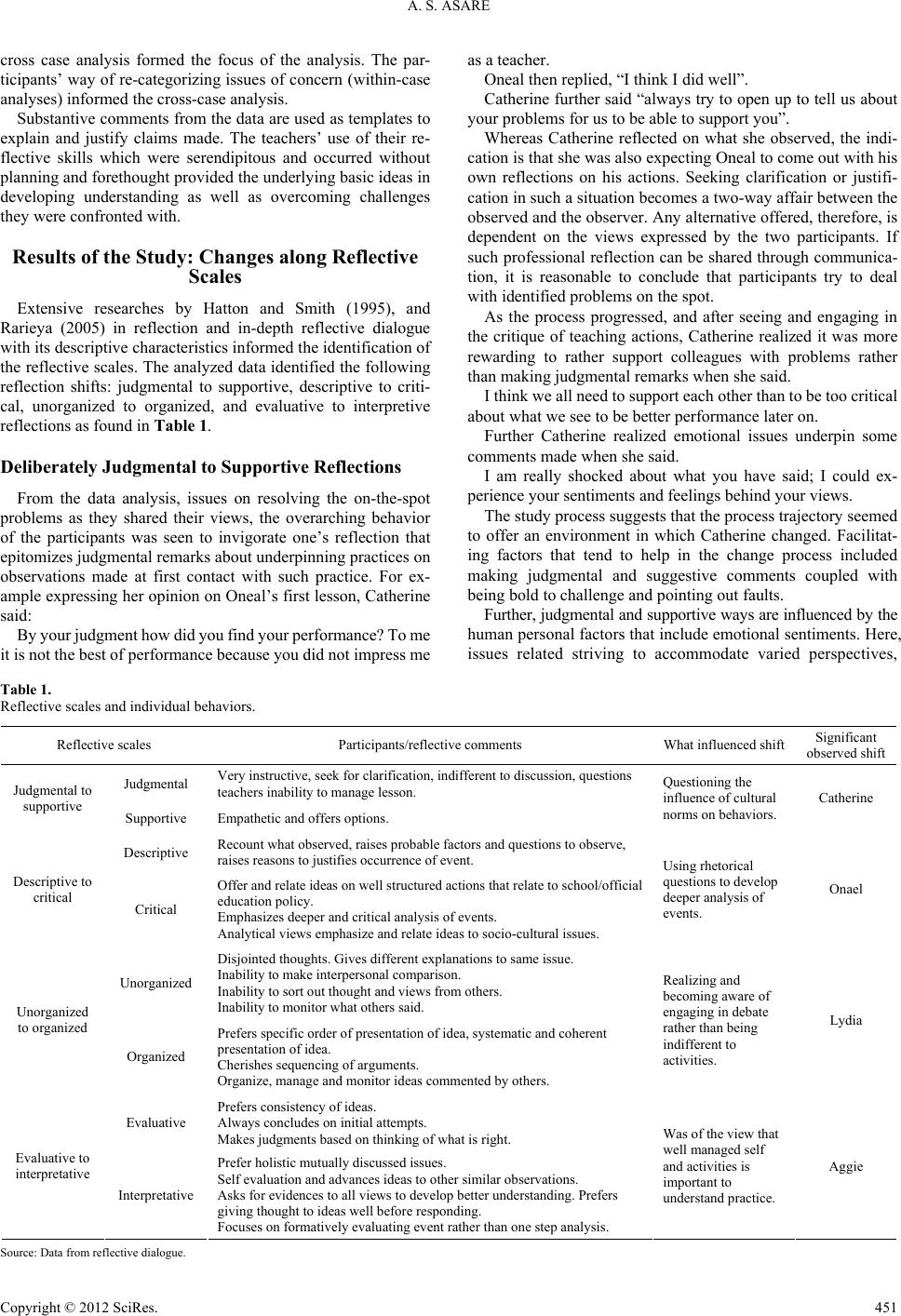

|