Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

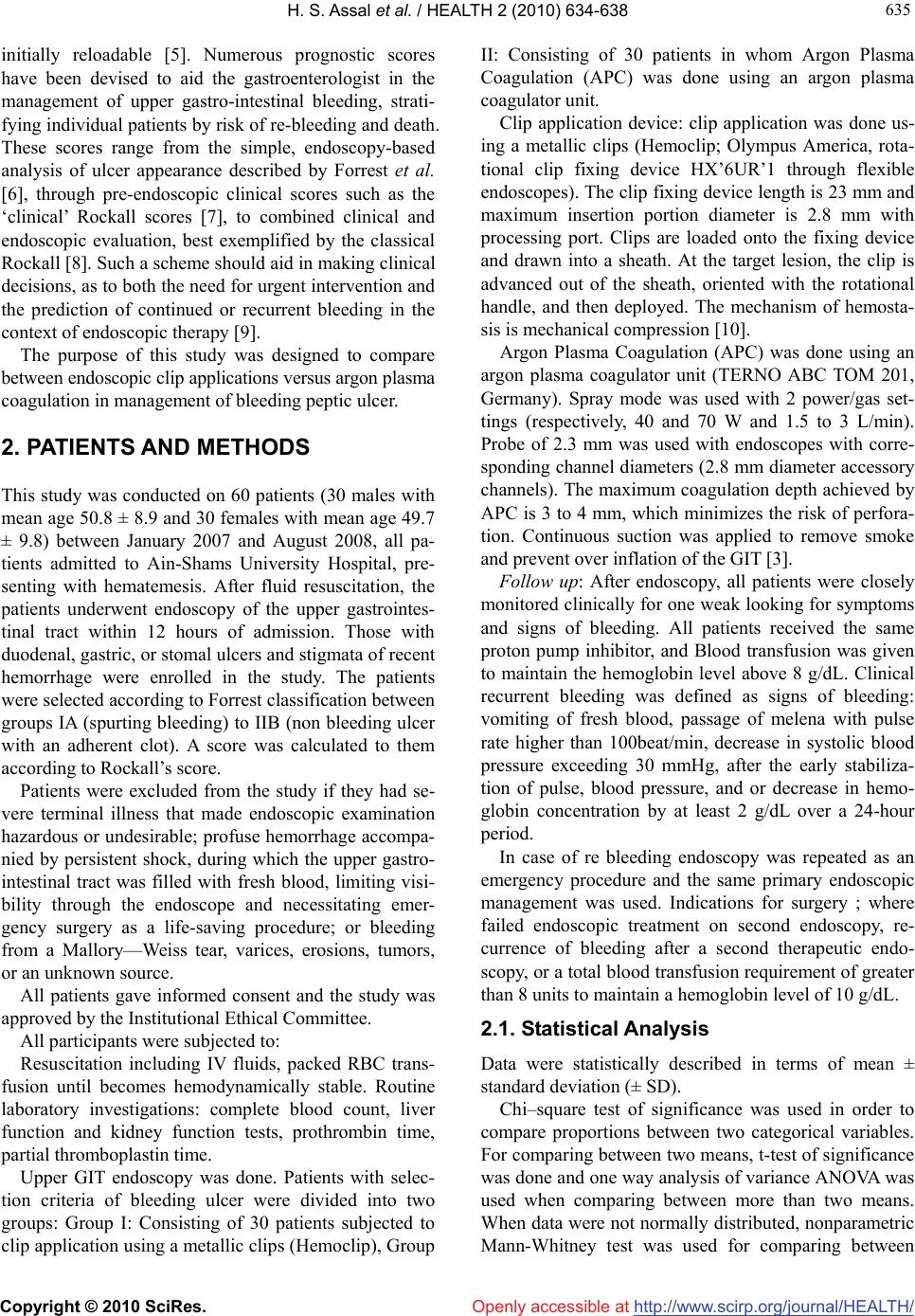

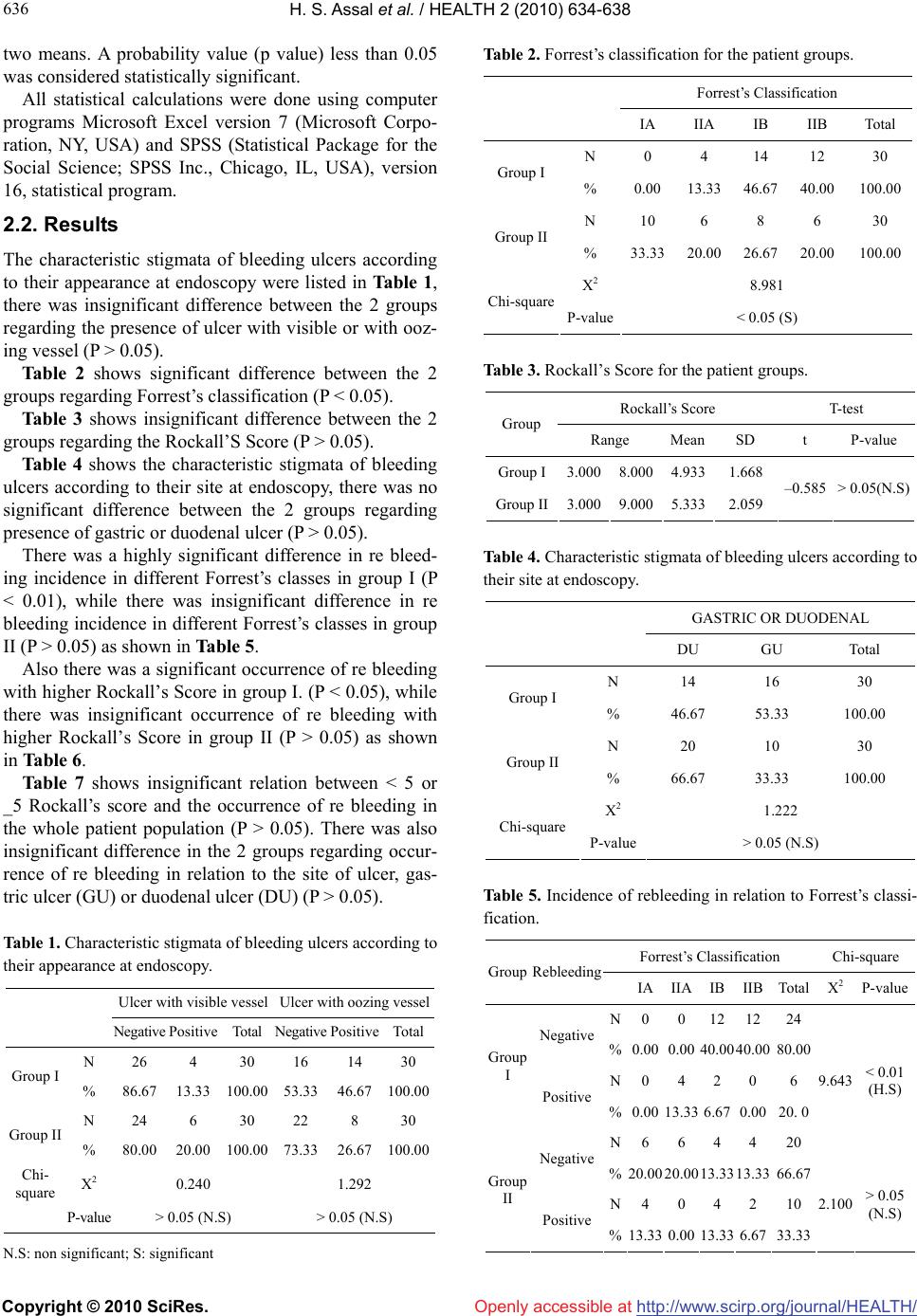

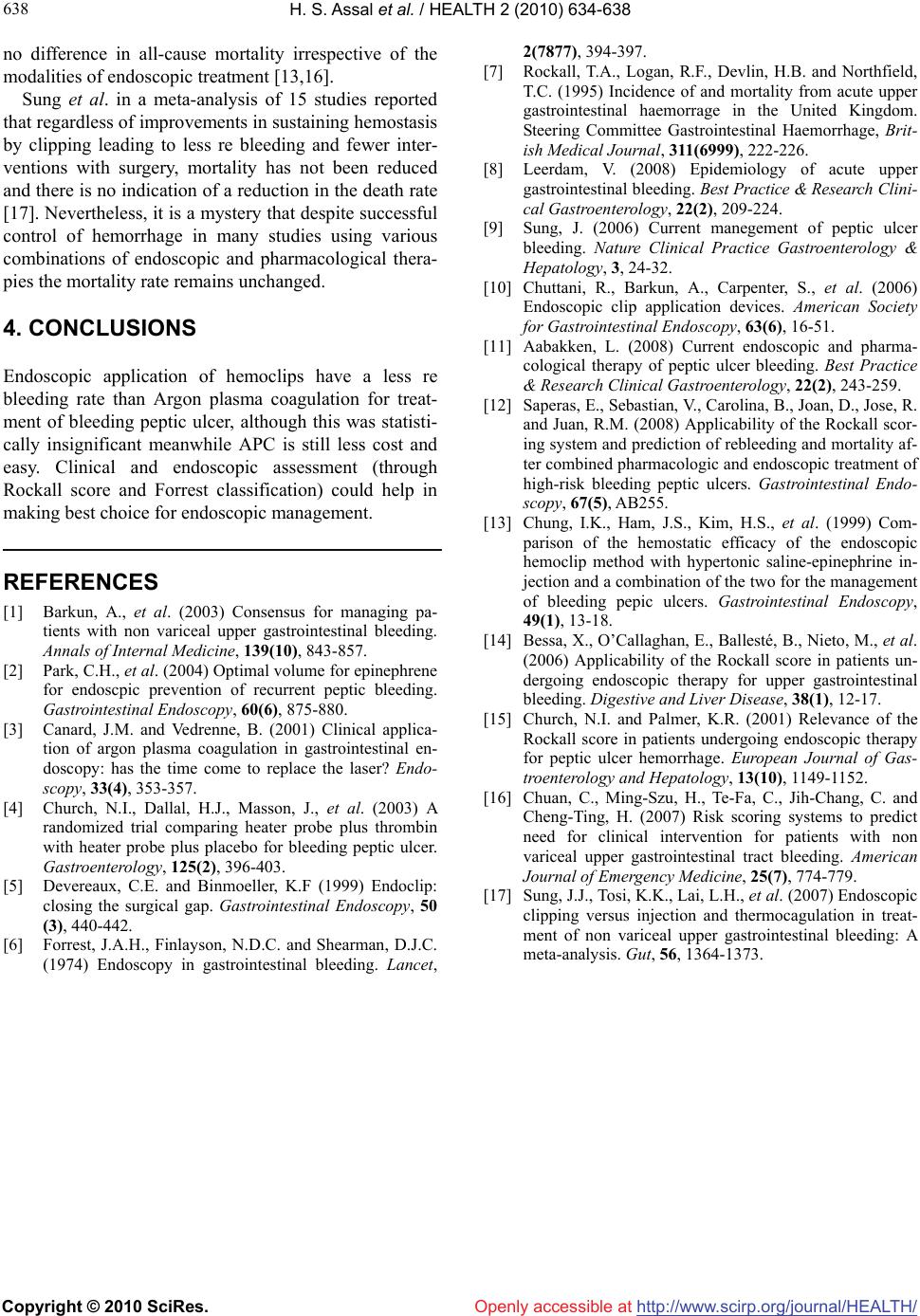

Vol.2, No.6, 634-638 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.26096 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Rokcall score versus forrest classification in endoscopic management of bleeding peptic ulcer Heba Sayed Assal1*, Ashraf Elsherbiny1, Hanan M. M. Badawy2, Ehab Hassan Nashaat3, Hesham al Shabrawi4 1Internal Medicine, Internal Medicine Department, National Research Center, Cairo-Egypt; *Corresponding Author: heba_assal@yahoo.com 2Internal Medicine, Department, Faculty of medicine, Ain-shams University, Cairo-Egypt 3Internal Medicine, Internal Medicine Department, Faculty of medicine, Ain-shams University, Cairo-Egypt 4Internal Medicine Department, Ahmed Maher Teaching hospital, Cairo-Egypt Received 27 November 2009; revised 22 February 2010; accepted 24 February 2010. ABSTRACT Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) remains an important emergency situation. In the last two decades, major developments took place influencing incidence, etiology and out- come of patients with acute UGIB. Peptic ulcer bleeding is the most significant complication of ulcer disease being responsible for 50% of all cases mortality. Aim of the study: To compare between endoscopic clip application versus argon plasma coagulation in management of bleeding peptic ulcer (BPU). Patients and Meth- ods: Sixty patients suffering from acute UGIB were randomly divided into two groups: group I included 30 patients treated with endoscopic clip application and Group II included 30 pa- tients subjected to endoscopic APC. All patients were classified according to Forrest classifica- tion and the clinical Rockall score. Results: There were significant differences between the two groups as regard Forrest classification (P < 0.05) there were insignificant difference be- tween the two groups as regard rockall score, site of the ulcer and re bleeding (P > 0.05). Re bleeding was significant with higher Rockall score in group I (P < 0.05) but it was insignifi- cant in group II (P > 0.05). Conclusion: Endo- scopic application of hemoclips have a less re bleeding rate than Argon plasma coagulation for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer, although this was statistically insignificant, meanwhile APC is still less cost and easy. Clinical and endoscopic assessment (through Rokcall score and Forrest classification) could help in making best choice for endoscopic management. Keywords: Endoscope; Bleeding Peptic Ulcer; Argon Plasma Coagulation; Clip Applications 1. INTRODUCTION Since the late 1980s, endoscopic haemostatic therapy has been widely accepted as the first-line therapy for up- per-gastrointestinal bleeding. Most clinical trials demon- strated a reduction in both recurrent bleeding and the need for surgical intervention when endoscopic hemo- stasis was used [1]. Endoscopic therapy can be broadly categorized into injection therapy, thermal coagulation, and mechanical hemostasis. When analyzed separately, injection therapy, thermal-contact devices, and me- chanical treatment all decrease the frequency of recur- rent bleeding and rate of surgical intervention [2]. Argon plasma coagulation (APC) is a non contact type of co- agulation that is easier to target to bleeding sites. A high-frequency current is transmitted by the ionized, electrically conductive argon gas. The argon gas flows onto the target surface, even if approached tangentially. APC has been used successfully to obtain hemostasis during open surgery. The use of APC in digestive tract endoscopy was first described in 1994. It is being ap- plied more and more widely in the treatment of different GI pathologic disorders, hemorrhagic lesions in particu- lar [3]. The only mechanical therapies widely available are endoscopically placed clips and band ligation de- vices. Endoscopic clips usually are placed over a bleed- ing site (e.g. visible vessel) and left in place [4]. This consisted of a stainless steel clip (of size approximately 6 mm long and 1.2 mm wide at the prongs) with a metal deployment device (that could be used to insert the clip into the endoscopic camera, and deployed outside the camera) enclosed in a plastic sheath. These clips were  H. S. Assal et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 634-638 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 635 635 initially reloadable [5]. Numerous prognostic scores have been devised to aid the gastroenterologist in the management of upper gastro-intestinal bleeding, strati- fying individual patients by risk of re-bleeding and death. These scores range from the simple, endoscopy-based analysis of ulcer appearance described by Forrest et al. [6], through pre-endoscopic clinical scores such as the ‘clinical’ Rockall scores [7], to combined clinical and endoscopic evaluation, best exemplified by the classical Rockall [8]. Such a scheme should aid in making clinical decisions, as to both the need for urgent intervention and the prediction of continued or recurrent bleeding in the context of endoscopic therapy [9]. The purpose of this study was designed to compare between endoscopic clip applications versus argon plasma coagulation in management of bleeding peptic ulcer. 2. PATIENTS AND METHODS This study was conducted on 60 patients (30 males with mean age 50.8 ± 8.9 and 30 females with mean age 49.7 ± 9.8) between January 2007 and August 2008, all pa- tients admitted to Ain-Shams University Hospital, pre- senting with hematemesis. After fluid resuscitation, the patients underwent endoscopy of the upper gastrointes- tinal tract within 12 hours of admission. Those with duodenal, gastric, or stomal ulcers and stigmata of recent hemorrhage were enrolled in the study. The patients were selected according to Forrest classification between groups IA (spurting bleeding) to IIB (non bleeding ulcer with an adherent clot). A score was calculated to them according to Rockall’s score. Patients were excluded from the study if they had se- vere terminal illness that made endoscopic examination hazardous or undesirable; profuse hemorrhage accompa- nied by persistent shock, during which the upper gastro- intestinal tract was filled with fresh blood, limiting visi- bility through the endoscope and necessitating emer- gency surgery as a life-saving procedure; or bleeding from a Mallory—Weiss tear, varices, erosions, tumors, or an unknown source. All patients gave informed consent and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee. All participants were subjected to: Resuscitation including IV fluids, packed RBC trans- fusion until becomes hemodynamically stable. Routine laboratory investigations: complete blood count, liver function and kidney function tests, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time. Upper GIT endoscopy was done. Patients with selec- tion criteria of bleeding ulcer were divided into two groups: Group I: Consisting of 30 patients subjected to clip application using a metallic clips (Hemoclip), Group II: Consisting of 30 patients in whom Argon Plasma Coagulation (APC) was done using an argon plasma coagulator unit. Clip application device: clip application was done us- ing a metallic clips (Hemoclip; Olympus America, rota- tional clip fixing device HX’6UR’1 through flexible endoscopes). The clip fixing device length is 23 mm and maximum insertion portion diameter is 2.8 mm with processing port. Clips are loaded onto the fixing device and drawn into a sheath. At the target lesion, the clip is advanced out of the sheath, oriented with the rotational handle, and then deployed. The mechanism of hemosta- sis is mechanical compression [10]. Argon Plasma Coagulation (APC) was done using an argon plasma coagulator unit (TERNO ABC TOM 201, Germany). Spray mode was used with 2 power/gas set- tings (respectively, 40 and 70 W and 1.5 to 3 L/min). Probe of 2.3 mm was used with endoscopes with corre- sponding channel diameters (2.8 mm diameter accessory channels). The maximum coagulation depth achieved by APC is 3 to 4 mm, which minimizes the risk of perfora- tion. Continuous suction was applied to remove smoke and prevent over inflation of the GIT [3]. Follow up: After endoscopy, all patients were closely monitored clinically for one weak looking for symptoms and signs of bleeding. All patients received the same proton pump inhibitor, and Blood transfusion was given to maintain the hemoglobin level above 8 g/dL. Clinical recurrent bleeding was defined as signs of bleeding: vomiting of fresh blood, passage of melena with pulse rate higher than 100beat/min, decrease in systolic blood pressure exceeding 30 mmHg, after the early stabiliza- tion of pulse, blood pressure, and or decrease in hemo- globin concentration by at least 2 g/dL over a 24-hour period. In case of re bleeding endoscopy was repeated as an emergency procedure and the same primary endoscopic management was used. Indications for surgery ; where failed endoscopic treatment on second endoscopy, re- currence of bleeding after a second therapeutic endo- scopy, or a total blood transfusion requirement of greater than 8 units to maintain a hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL. 2.1. Statistical Analysis Data were statistically described in terms of mean ± standard deviation (± SD). Chi–square test of significance was used in order to compare proportions between two categorical variables. For comparing between two means, t-test of significance was done and one way analysis of variance ANOVA was used when comparing between more than two means. When data were not normally distributed, nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used for comparing between  H. S. Assal et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 634-638 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 636 two means. A probability value (p value) less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical calculations were done using computer programs Microsoft Excel version 7 (Microsoft Corpo- ration, NY, USA) and SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), version 16, statistical program. 2.2. Results The characteristic stigmata of bleeding ulcers according to their appearance at endoscopy were listed in Table 1, there was insignificant difference between the 2 groups regarding the presence of ulcer with visible or with ooz- ing vessel (P > 0.05). Table 2 shows significant difference between the 2 groups regarding Forrest’s classification (P < 0.05). Table 3 shows insignificant difference between the 2 groups regarding the Rockall’S Score (P > 0.05). Table 4 shows the characteristic stigmata of bleeding ulcers according to their site at endoscopy, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups regarding presence of gastric or duodenal ulcer (P > 0.05). There was a highly significant difference in re bleed- ing incidence in different Forrest’s classes in group I (P < 0.01), while there was insignificant difference in re bleeding incidence in different Forrest’s classes in group II (P > 0.05) as shown in Table 5. Also there was a significant occurrence of re bleeding with higher Rockall’s Score in group I. (P < 0.05), while there was insignificant occurrence of re bleeding with higher Rockall’s Score in group II (P > 0.05) as shown in Table 6. Table 7 shows insignificant relation between < 5 or _5 Rockall’s score and the occurrence of re bleeding in the whole patient population (P > 0.05). There was also insignificant difference in the 2 groups regarding occur- rence of re bleeding in relation to the site of ulcer, gas- tric ulcer (GU) or duodenal ulcer (DU) (P > 0.05). Table 1. Characteristic stigmata of bleeding ulcers according to their appearance at endoscopy. Ulcer with visible vessel Ulcer with oozing vessel Negative Positive Total Negative PositiveTotal N 26 4 30 16 14 30 Group I % 86.67 13.33 100.00 53.33 46.67100.00 N 24 6 30 22 8 30 Group II % 80.00 20.00 100.00 73.33 26.67100.00 Chi- square X2 0.240 1.292 P-value > 0.05 (N.S) > 0.05 (N.S) N.S: non significant; S: significant Table 2. Forrest’s classification for the patient groups. Forrest’s Classification IA IIA IB IIB Total N 0 4 14 12 30 Group I % 0.0013.33 46.67 40.00100.00 N 10 6 8 6 30 Group II % 33.3320.00 26.67 20.00100.00 X2 8.981 Chi-square P-value< 0.05 (S) Table 3. Rockall’s Score for the patient groups. Rockall’s Score T-test Group Range Mean SD t P-value Group I3.0008.0004.933 1.668 Group II3.0009.0005.333 2.059 –0.585 > 0.05(N.S) Table 4. Characteristic stigmata of bleeding ulcers according to their site at endoscopy. GASTRIC OR DUODENAL DU GU Total N 14 16 30 Group I % 46.67 53.33 100.00 N 20 10 30 Group II % 66.67 33.33 100.00 X2 1.222 Chi-square P-value> 0.05 (N.S) Table 5. Incidence of rebleeding in relation to Forrest’s classi- fication. Forrest’s Classification Chi-square Group Rebleeding IA IIAIB IIB Total X2P-value N 0012 12 24 Negative %0.000.00 40.0040.00 80.00 N0 4 2 0 6 Group I Positive %0.0013.336.67 0.00 20. 0 N6 6 4 4 20 9.643 < 0.01 (H.S) Negative % 20.0020.0013.3313.33 66.67 N4 0 4 2 10 Group II Positive %13.33 0.00 13.33 6.67 33.33 2.100 > 0.05 (N.S)  H. S. Assal et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 634-638 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 637 637 Table 6. Incidence of rebleeding in relation to Rockall’s Score. Rebleeding Negative Positive T-test Rockall’s Score Mean SD MeanSD t P-value Group I 4.417 1.240 7.0001.732 –3.014 < 0.05 (S) Group II 5.900 2.234 4.2001.095 1.587 > 0.05 (N.S) Table 7. Correlation between high risk Rockall’s score and rebleeding. Rebleeding Rockall’s Score Negative Positive Total N 20 4 24 < 5 % 33.33 6.67 40.00 N 24 12 36 ≥ 5 % 40.00 20. 00 60.00 X2 1.02 Chi-square P-value > 0.05 (N.S) 3. DISCUSSION Peptic ulcer bleeding is the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, responsible for about 50% of all cases. Mortality is increasing with increasing age and is significantly higher in patients who are already admit- ted in hospital for co-morbidity [3]. Risk factors for peptic ulcer bleeding are non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) use and Helicobacter Pylori (HP) infection [8]. In patients with ulcers presenting with ongoing bleed- ing or high risk features (Forrest I, IIA, IIB); surgery was frequently required in the past to solve the situation. However, endoscopic therapy has been well documented to treat these ulcers [11]. The timing of the initial endoscopy has been debated. In general, red hematemesis indicates emergency upper endoscopy while black hematemesis and/or melena without haemodynamic instability can wait until normal working hours. However, from a logistic point of view early endoscopy has been advocated to ensure optimal utilization of resources [11] .In this study there was no significant difference in both groups regarding age, shock, presence of co morbid illness or liver cell failure, ulcer size, rockall score and site of ulcer; factors known to affect prognosis in many previous studies. Our study showed that the rate of re bleeding was slightly higher in APC group despite of being statisti- cally insignificant. Also there was no significant relation between the rates of re bleeding and the size of the ulcer. Few reports have concerned the indication for and effi- cacy of each hemostatic therapy according to location, depth and size of ulcer and bleeding activity of the ex- posed vessel as if the ulcer is large or deep, the possibil- ity of complications including further ulceration, recur- rence of bleeding and perforation is high [12]. A great care is required in performing the procedure if the bleeding ulcer is located on the posterior wall or lesser curvature of the gastric body or on the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb, the hemostatic rate is lower than for other therapies because of the technical diffi- culty of approaching the lesion [13]. In the present study although there was no statistical significance difference in re bleeding incidence in both groups there was highly significant difference in re bleeding incidence in relation to different Forrest’s classes in group I (P < 0.01), while there was insignifi- cant difference in re bleeding incidence in different Forrest’s classes in group II. Also, the rate of surgical interference of both groups was 0%. In recent years, the Rockall score has been used to se- lect patients with a low risk of rebleeding for early dis- charge. Almost all patients in this low risk group belong to patients without any stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH). However, patients with a SRH are a high-risk group for further re-bleeding and also mortality. It is therefore important to determine whether the Rockall score could be useful in patients who have undergone endoscopic therapy for UGIB to identify high-risk pa- tients and thus improve their management and outcome [14]. In the present study we assessed correlation between high risk Rockall’s score (> 5) and occurrence of re bleeding which re bleeding was 6.8 % in low risk Rock- all’s score (< 5) while re bleeding was 20% in high risk Rockall’s score (> 5). However, this was statistically non significant, but incidence of re bleeding in relation to high risk Rockall's score was significant in group I. This did not go in agreement with others [12], who concluded that the Rockall scoring system accurately identifies patients at high risk of death but not of re bleeding [12]. In spite that our study partially goes with others, who observe good correlation between the Rockall score and both the probability of re bleeding and mortality in pa- tients undergoing endoscopic therapy for peptic ulcer hemorrhage [15,16]. In the present study the mortality rates between the two groups were the same which was 0% in the two groups despite of significantly higher need for surgery in group II. This goes with others, who concluded that there was  H. S. Assal et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 634-638 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 638 no difference in all-cause mortality irrespective of the modalities of endoscopic treatment [13,16]. Sung et al. in a meta-analysis of 15 studies reported that regardless of improvements in sustaining hemostasis by clipping leading to less re bleeding and fewer inter- ventions with surgery, mortality has not been reduced and there is no indication of a reduction in the death rate [17]. Nevertheless, it is a mystery that despite successful control of hemorrhage in many studies using various combinations of endoscopic and pharmacological thera- pies the mortality rate remains unchanged. 4. CONCLUSIONS Endoscopic application of hemoclips have a less re bleeding rate than Argon plasma coagulation for treat- ment of bleeding peptic ulcer, although this was statisti- cally insignificant meanwhile APC is still less cost and easy. Clinical and endoscopic assessment (through Rockall score and Forrest classification) could help in making best choice for endoscopic management. REFERENCES [1] Barkun, A., et al. (2003) Consensus for managing pa- tients with non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(10), 843-857. [2] Park, C.H., et al. (2004) Optimal volume for epinephrene for endoscpic prevention of recurrent peptic bleeding. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 60(6), 875-880. [3] Canard, J.M. and Vedrenne, B. (2001) Clinical applica- tion of argon plasma coagulation in gastrointestinal en- doscopy: has the time come to replace the laser? Endo- scopy, 33(4), 353-357. [4] Church, N.I., Dallal, H.J., Masson, J., et al. (2003) A randomized trial comparing heater probe plus thrombin with heater probe plus placebo for bleeding peptic ulcer. Gastroenterology, 125(2), 396-403. [5] Devereaux, C.E. and Binmoeller, K.F (1999) Endoclip: closing the surgical gap. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 50 (3), 440-442. [6] Forrest, J.A.H., Finlayson, N.D.C. and Shearman, D.J.C. (1974) Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet, 2(7877), 394-397. [7] Rockall, T.A., Logan, R.F., Devlin, H.B. and Northfield, T.C. (1995) Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage, Brit- ish Medical Journal, 311(6999), 222-226. [8] Leerdam, V. (2008) Epidemiology of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Best Practice & Research Clini- cal Gastroenterology, 22(2), 209-224. [9] Sung, J. (2006) Current manegement of peptic ulcer bleeding. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 3, 24-32. [10] Chuttani, R., Barkun, A., Carpenter, S., et al. (2006) Endoscopic clip application devices. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 63(6), 16-51. [11] Aabakken, L. (2008) Current endoscopic and pharma- cological therapy of peptic ulcer bleeding. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology, 22(2), 243-259. [12] Saperas, E., Sebastian, V., Carolina, B., Joan, D., Jose, R. and Juan, R.M. (2008) Applicability of the Rockall scor- ing system and prediction of rebleeding and mortality af- ter combined pharmacologic and endoscopic treatment of high-risk bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointestinal Endo- scopy, 67(5), AB255. [13] Chung, I.K., Ham, J.S., Kim, H.S., et al. (1999) Com- parison of the hemostatic efficacy of the endoscopic hemoclip method with hypertonic saline-epinephrine in- jection and a combination of the two for the management of bleeding pepic ulcers. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 49(1), 13-18. [14] Bessa, X., O’Callaghan, E., Ballesté, B., Nieto, M., et al. (2006) Applicability of the Rockall score in patients un- dergoing endoscopic therapy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Digestive and Liver Disease, 38(1), 12-17. [15] Church, N.I. and Palmer, K.R. (2001) Relevance of the Rockall score in patients undergoing endoscopic therapy for peptic ulcer hemorrhage. European Journal of Gas- troenterology and Hepatology, 13(10), 1149-1152. [16] Chuan, C., Ming-Szu, H., Te-Fa, C., Jih-Chang, C. and Cheng-Ting, H. (2007) Risk scoring systems to predict need for clinical intervention for patients with non variceal upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 25(7), 774-779. [17] Sung, J.J., Tosi, K.K., Lai, L.H., et al. (2007) Endoscopic clipping versus injection and thermocagulation in treat- ment of non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Gut, 56, 1364-1373. |