Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

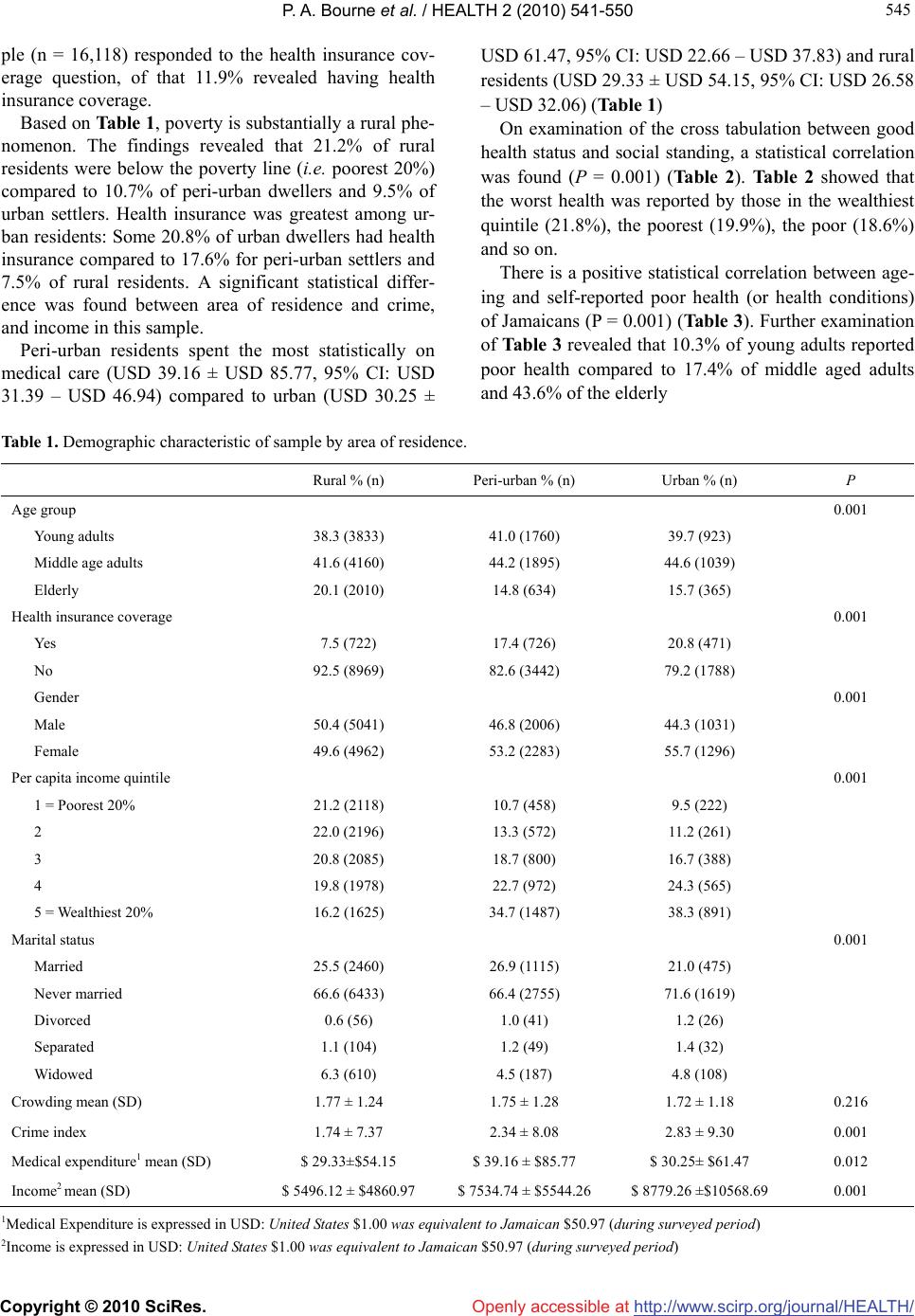

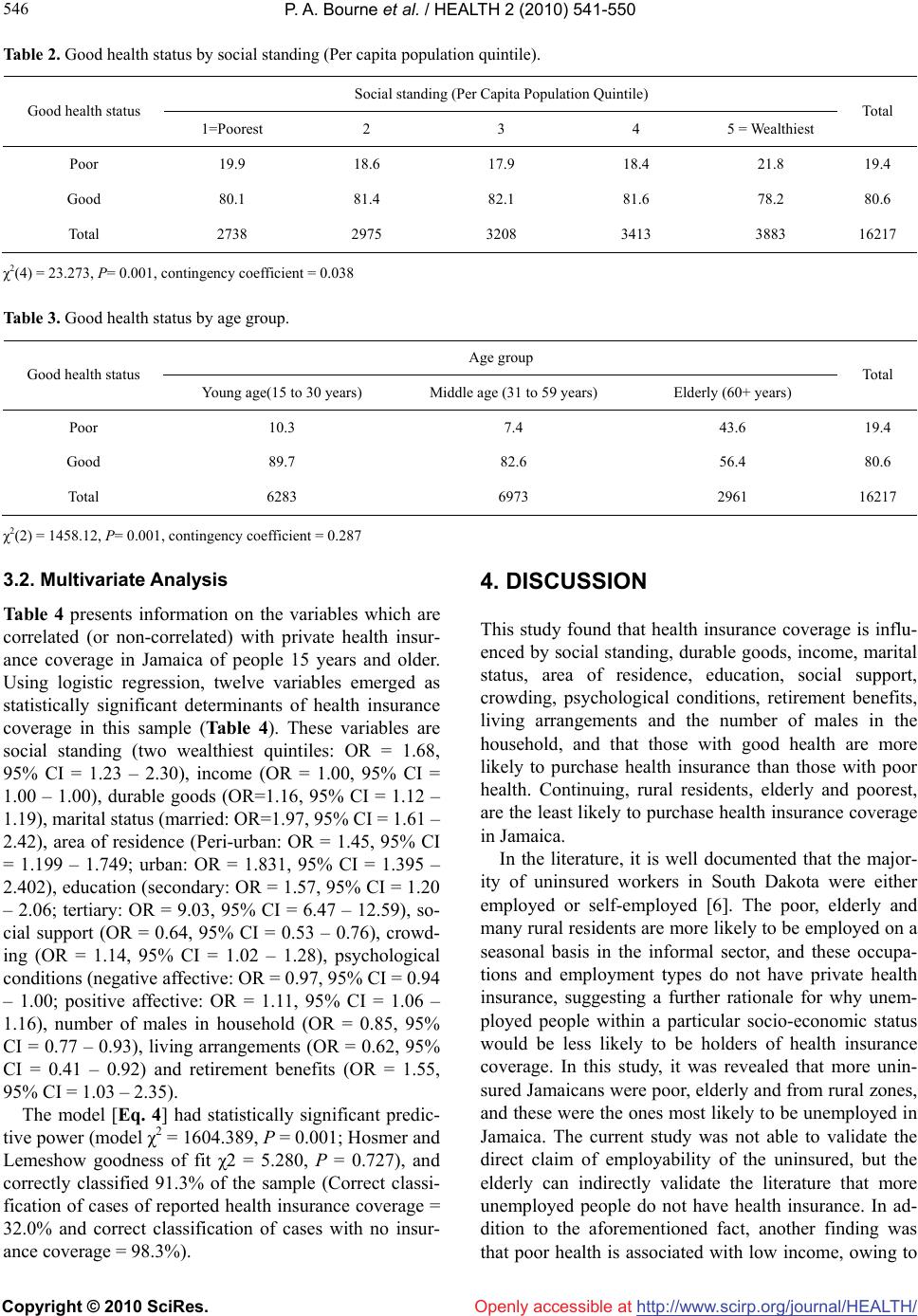

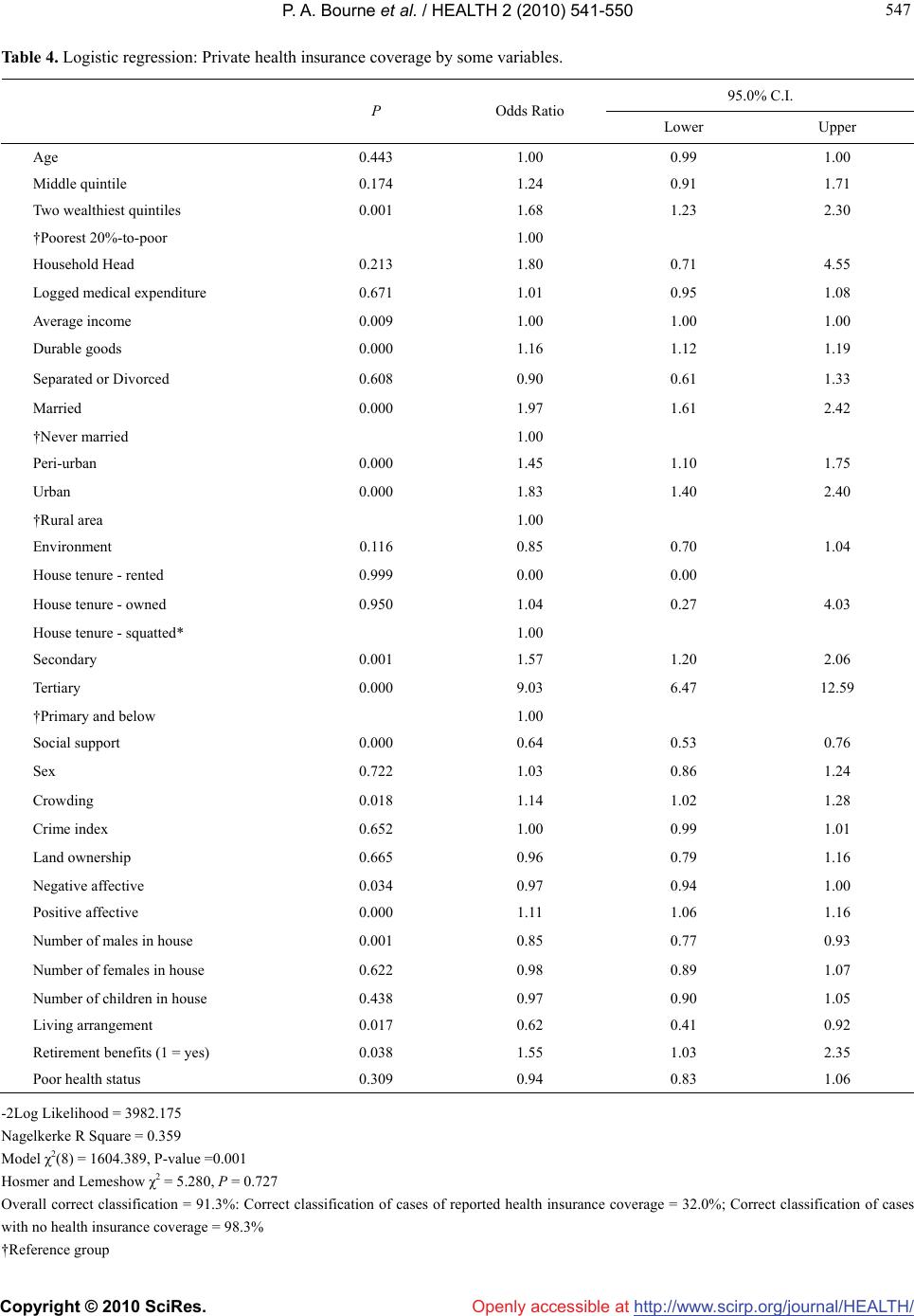

Vol.2, No.6, 541-550 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.26081 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Determinants of self-rated private health insurance coverage in Jamaica Paul A. Bourne1*, Maureen D. Kerr-Campbell2 1Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medical Sciences The University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica; *Corresponding Author: paulbourne1@yahoo.com 2Systems Development Unit, Main Library, The University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica Received 18 November 2009; revised 5 January 2010; accepted 8 January 2010. ABSTRACT The purpose of the current study was to model the health insurance coverage of Jamaicans; and to identify the determinants, strength and predictive power of the model in order to aid clinicians and other health practitioners in un- derstanding those who have health insurance coverage. This study utilized secondary data taken from the dataset of the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions which was collected between July and October 2002. It was a nationally rep- resentative stratified random sample survey of 25,018 respondents, with 50.7% females and 49.3% males. The data was collected by way of a self-administered questionnaire. The non-re- sponse rate for the survey was 29.7% with 20.5% not responding to particular questions, 9.0% not participating in the survey and another 0.2% being rejected due to data cleaning. The current research extracted 16,118 people 15 years and older from the survey sample of 25,018 respondents in order to model the de- terminants of private health insurance coverage in Jamaica. Data were stored, retrieved and analyzed using SPSS for Windows 15.0. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to establish statistical significance. Descriptive analysis was used to provide baseline information on the sample, and cross-tabulations were used to examine some non-metric variables. Logistic regression was used to identify, determine and establish those factors that influence private health insurance coverage in Jamaica. This study found that approximately 12% of Jamai- cans had private health insurance coverage, of which the least health insurance was owned by rural residents (7.5%). Using logistic regression, the findings revealed that twelve variables emerged as statistically significant determinants of health insurance coverage in this sample. These variables are social standing (two weal- thiest quintile: OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.23 – 2.30), income (OR = 1.00, 95%CI = 1.00 – 1.00), durable goods (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.12 – 1.19), marital status (married: OR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.61 – 2.42), area of residence (Peri-urban: OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.199 – 1.75; urban: OR = 1.83, 95% CI = 1.40 – 2.40), education (secondary: OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.20 – 2.06; tertiary: OR = 9.03, 95% CI = 6.47 – 12.59), social support (OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.53 – 0.76), crowding (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.02 – 1.28), psychological conditions (negative affec- tive: OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94 – 1.00; positive affective: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.06 – 1.16), num- ber of males in household (OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.77 – 0.93), living arrangements (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41 – 0.92) and retirement benefits (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.03 – 2.35). This study highlighted the need to address preventative care for the wealthiest, rural residents and the fact that social support is crucial to health care, as well as the fact that medical care costs are borne by the extended family and other social groups in which the individual is (or was) a member, which explains the low demand for health insurance in Jamaica. Private health care in Jamaica is substantially determined by af- fordability and education rather than illness, and it is a poor measure of the health care- seeking behaviour of Jamaicans. Keywords: Health Insurance; Private Health Coverage; Social Determinants of Health Insurance Coverage; Jamaica  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 542 1. INTRODUCTION Literature on private health insurance or health insurance in the Caribbean, and in particular Jamaica, has been substantially on 1) population density–i.e. coverage, 2) coverage offerings, 3) cost of care–i.e. health economics, and 4) acceptance (or lack of) by health service provid- ers of certain insurance coverage. Having extensively perused the literature review on private health insurance and health care reform in Jamaica, it is obvious that no study has been conducted identifying the different fac- tors that explain health insurance coverage in this nation. The individual utilization pattern of health insurance coverage is highly associated over time with older adults [1,2] as they prepare for the degeneration of the body; but, what else do we know about those who have private health insurance in Jamaica? Do insurers attract healthy patients, and are high risk individuals more likely to become insured as against their low risk (i.e. less health conditions) counterparts? Health insurance is a con- stituent of health seeking behaviour, suggesting that it is equally important in any study of health, quality of life, and wellbeing. In this study the researchers will criti- cally examine factors that can be used to predict private health insurance coverage by using a logistic regression technique to explain the independent effect; and in the process the researchers will investigate the lives of re- spondents in order to understand those who reported having private health insurance coverage. Instead of providing an elaborate and extensive de- scription of ‘health insurance’, we will give a simplified meaning of this construct. Health insurance is protection against medical costs owing to the possibility of injuries, dysfunctions and other happenings that hinder the body from performing at some functional standard. In keep- ing with this definition, a health insurance policy is the contract that is signed by an insurer (i.e. insurance pro- vider) and an individual or a group, in which the insurer agrees to pay a specific sum (i.e. a premium). Hence, the population’s health service is partially dependent on health insurance coverage or the welfare system of the state. Jamaica does not have a public health insurance system, but one for the elderly and those who have par- ticular chronic health conditions, such as diabetes melli- tus, hypertension, cancer or a combination. In September 2001, the Cabinet of Jamaica accepted and approved a proposal for the establishment of a National Health Fund (NHF) that would assists patients as well as the elderly in Jamaicans. The individual benefits of the NHF (i.e. public health insurance options) for the elderly and for those with particular chronic health conditions was offi- cially commenced in 2003 (i.e. August 1, 2003), and so there are only data on private health insurance coverage from 1988-2002. Despite the fact that Jamaica has insti- tuted a free health-care service delivery programme for its child population (below 18 years in 2006), the quality of care which is relatively good is still surrounded by a certain socio-psychological milieu as well as inequality in health care offerings in the private versus the public sector. This explains the rationale why some people seek private health care and by extension private health in- surance coverage [3] to meet the impending higher medical cost of care [1,4-7] and a particular quality of service–environment, customer service and length of service. The current study will be examined within the theoretical framework used by Franc, Perronnin, & Pi- erre [8]. 1.1. Theoretical Framework A South African Health Inequalities Survey (SANHIS) carried out in 1994 of 3,489 women ages 16 to 64 years was used to model the determinants of health insurance coverage. Kirigia et al., [8] sought to model health in- surance demand among South African women. They used binary logistic regression analyses to estimate health insurance coverage among the sample and various determinants of health insurance coverage. Health in- surance coverage of the sample was determined by socio-demographic characteristics, health rating, envi- ronment rating, bad health choices (i.e. smoking and alcohol consumption), and contraceptives. These were embodied in the mathematical formula, Eq. 1: Pij = (α + β1 Health rating + β2 Environment rating + β3 Residence + β4 Income + β5 Education + β6 Age + β7 Age squared + β8 Race + β9 Household size + β10 Occupation + β11 Employment + β12 Smoking + β13 Alcohol use + β14 Contraceptive use = β15 Marital status + εi (1) where Pij = 1 if individual I owns insurance (j = 1) and equal otherwise (j = 0); α is intercept terms; (β’s) are the estimated coefficients; and εi is the stochastic error term. The conceptual framework of Kirigia et al.’s work [8] was on two risks of health care. They believed that these risks are (1) the risk of becoming ill, with the associated loss in quality of life, cost of medical care, loss of pro- ductive times, more serious cases, mortality, and (2) the risk of total or incomplete or delayed recovery [8]. This denotes that a person’s decision to buy health insurance would be based on differentials between the level of expected utility of the insurance and the expected utility without insurance. It is this binary nature dependent variable and the desire to determine the effect of par- ticular independent variables that justified the binary logistic regression technique. Eq. 1 allows for the estimation of the individual probability of having or not having health insurance by some explanatory variables. Kirigia et al., [8] did not  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 543 543 stipulate whether health insurance was public or private coverage, and this was addressed in another research paper. Using the same principle of econometric analysis as Kirigia et al., a group of researchers used a single multiple regression equation that identified explanatory variables and the powers of particular factors that can be used to determine determinants of those who have pri- vate health insurance [9]. This captures a standard utility theory model of a demand for private health insurance coverage, Eq. 2: Y = β0 + β1P + β2I + β3Z (2) where the standard utility theory is expressed in the quantity demanded of health insurance, Y, can be written as a function of the user price of health insurance, P, income, I, and a vector of other factors, Z or (with time subscripts suppressed); and β1 and β2 represent, respec- tively, the price and income elasticity of the demand for private health insurance. Like Kirigia et al., [8] self-rated private health insur- ance coverage is a binary variable (1= yes and 0= other- wise), which denotes that a logistic regression model will be used to estimate the determinants and determine their impact on the dependent variable, as was done by Ahking, Giaccotto, and Santerre [9]-Eq. 3. Instead of having a vector factor which envelopes individual char- acteristics, this research isolates those factors including income, unlike Eqs. 1 and 2, and added more variables such as psychological conditions, living arrangements and social support. HIi = ƒ(Yi, HCi, Eni, MSi, ARi , Ei, SSi, Oi, Pi, Gi, NPi, PPi, Mi, Fi, Di, EWi , Ai, Ri, YPi, Pmci, LLi, CRi,) (3) where Eq. 3 is Private Health Insurance coverage, HIi, is a function of Yi is average current income per person in household i; HCi is health conditions of person i; Eni is physical environment of person i; MSi is marital status of person i; ARi is area of residence of person i; Ei is educa- tional level of person i; SSi is social support of person i; Oi is average occupancy per person i; Pi is property ownership of person i; Gi is gender per person i; NPi is negative affective psychological conditions per person i; PPi is positive affective psychological conditions per person i; Mi is number of males per household per per- son i; Fi is number of females per household per person i; Di is the number of children per household per person i; EWi is durable goods; Ai is age of person i; Ri is retire- ment benefits of person i; YPi is social standing of per- son i; Pmci is cost of medical care of person i, LLi is living arrangements of person i; and CRi is crowding. The current study found the following determinants of private health insurance of Jamaica (Eq. 4): HIi = ƒ (Yi, ARi, MSi, SSi, Ei, ∑(NP i, PPi), Mi , EW i, Ri, YPi,LLi,CRi,) (4) where Eq. 4 is Private Health Insurance Coverage, HIi, is a function of Yi is average current income per person in household i; HCi is health conditions of person i; ARi is area of residence of person i; MSi is marital status of person i; SSi is social support of person i; Gi is gender per person i; Ei is educational level of person i; NPi is negative affective psychological conditions per person i; PPi is positive affective psychological conditions per person i; EWi is durable goods of person i; Di is the number of children per household per person i; Ri is retirement benefits of person i, YPi is social standing of person i, LLi is living arrangements and CRi is crowd- ing. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Method This study utilized secondary data taken from the dataset of the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions which was collected between July and October 2002. It was a na- tionally representative stratified random sample survey of 25,018 respondents, with 50.7% females (N = 12,675) and 49.3% males (N = 12,332). The data was collected by way of an administered questionnaire. The non-re- sponse rate for the survey was 29.7% with 20.5% not responding to particular questions, 9.0% not participat- ing in the survey and another 0.2% being rejected due to data cleaning. The current research extracted a sub- sample of 16,118 people 15 years and older from the survey sample of 25,018 respondents in order to model the determinants of private health insurance coverage in Jamaica. The rationale for the use of the 2002 data set instead of the 2007 is primarily because of the sample popula- tion. In 2002, the institutions that were principally re- sponsible for the data collection used 10% of the na- tional population to gather pertinent data on the labour force, and this was for the Survey of Living Conditions. It represents the largest data collected on the Jamaican population, and data was also collected on crime and victimization and the environment, these being included for the first time, and omitted in subsequent surveys. Given the nature of crime, violence and victimization in the nation, we opted to use a survey that had crime and the environment as among data collected. Another con- dition for the selection of this dataset was the fact that it was a large population, as against other years when the population was less than 3,000. Within the context of a non-response rate that ranges from 10 to 30 per cent, a larger rather than a smaller sample size coupled with some pertinent variables was preferred to a smaller sam- ple size without the two critical aforementioned vari- ables. Data were stored, retrieved and analyzed using  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 544 SPSS for Windows 15.0. A p-value of less than 0.05 was used to establish statistical significance. Descriptive analysis will be done on the sampled population in order to provide background information on the respondents; and the enter method of logistic regression will be used to establish the determinants of self-reported private health insurance in Jamaica. Using the principle of par- simony, the final model will consist of only those statis- tically significant variables. Where multicollinearity existed (r > 0.7), variables were independently entered into the model to aid in determining which one should be retained during the final model construction (i.e. the de- cision therefore was based on the variable’s contribution to the predictive power of the model and the goodness of fit). 2.2. Measure Health conditions: The summation of reported ailments, injuries or illnesses in the last four weeks, which was the survey period; where higher values denote greater health conditions; it ranges from 0 to 4 conditions. Health status is a dummy variable, where 1 (good health) = not reporting an ailment or dysfunction or illness in the last four weeks, which was the survey period; 0 (poor health) if there were no self-reported ailments, injuries or ill- nesses. While self-reported ill-health is not an ideal in- dicator of actual health conditions as people may un- der-report their health condition, it is still an accurate proxy of ill-health and mortality. Household crowding: This is the average number of persons living in a room. Physical Environment: This is the number of responses from people who indicated suffering landsides; property damage due to rains, flooding or soil erosion. Psycho- logical conditions are the psychological state of an indi- vidual, sub-divided into positive and negative affective psychological conditions. 18-19 Positive affective psy- chological condition signifies the number of responses with regard to being hopeful and optimistic about the future and life generally. Negative affective psychologi- cal condition means number of responses from a person on having lost a breadwinner and/or family member, loss of property, being made redundant, or failing to meet household and other obligations. Income is proxied by total individual expenditure in USD. During the survey period, United States $1.00 was equivalent to Jamaican $50.97. Average income (i.e. per person per household) is total expenditure divided by the number of persons in the household. Age: The number of years lived, which is also referred to age at last birthday. This is a continuous variable, ranging from 15 to 99 years. Age group is classified into three categories. These are young adults (ages 15 to 30 years), middle aged adults (ages 31 to 59 years) and the elderly (ages 60 + years). Retirement benefits were measured by those who recei- ved retirement income. Private Health Insur- ance Coverage: This is a dummy variable, where 1 de- notes self- reported ownership of private health insur- ance coverage and 0 is otherwise. Durable goods: This variable is the summation of the self-reported durable goods owned by an individual ex- cluding houses, buildings and property. where Di 28 i 1 EW D i ranges from 1 to 28, where higher values denote greater ownership of durable goods. Living arrangements are a dummy variable where, 1 = living alone, 0 = living with family members or relative. Social support (or network) denotes different social networks with which the individual has been or is in- volved (1 = membership of and/or visits to civic organi- zations or having friends that visit one’s home or with whom one is able to network, 0 = otherwise). Crime: n ij i1 CrimeIndexi=K T where Ki represents the frequency with which an indi- vidual has witnessed or experienced a crime, where i denotes 0, 1 and 2, in which 0 indicates not witnessing or experiencing a crime, 1 means witnessing 1 to 2, and 2 symbolizes seeing 3 or more crimes. Tj denotes the degree of the different typologies of crime witnessed or experienced by an individual (where j = 1…4, where 1 = valuables stolen, 2 = attacked with or without a weapon, 3 = threatened with a gun, and 4 = sexually assaulted or raped. The summation of the frequency of crime by the degree of the incident ranges from 0 and a maximum of 51. Social standing is proxied by per capita population quintile (from poorest-to-wealthiest) 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Sample The sample was 16,619 respondents (i.e. 48.6% males and 51.4% females; with 39.2% young adults, 42.7% middle aged adults and 18.1% elderly). Some 25.8% of the sample resided in peri-urban areas; 60.2% in rural zones; 14.0% were from urban areas; 16.8% were below the poverty line (i.e. poorest 20%); while 18.2% were just above the poverty line compared to 21.2% in the wealthy quintile and 24.1% in the wealthiest 20%. Of the sample, 97.6% responded to the health status ques- tion. Of those who responded to the health status ques- tion, 80.6% indicated at least good health and 19.4% poor health. Ninety-seven percentage points of the sam-  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 545 545 ple (n = 16,118) responded to the health insurance cov- erage question, of that 11.9% revealed having health insurance coverage. Based on Table 1, poverty is substantially a rural phe- nomenon. The findings revealed that 21.2% of rural residents were below the poverty line (i.e. poorest 20%) compared to 10.7% of peri-urban dwellers and 9.5% of urban settlers. Health insurance was greatest among ur- ban residents: Some 20.8% of urban dwellers had health insurance compared to 17.6% for peri-urban settlers and 7.5% of rural residents. A significant statistical differ- ence was found between area of residence and crime, and income in this sample. Peri-urban residents spent the most statistically on medical care (USD 39.16 ± USD 85.77, 95% CI: USD 31.39 – USD 46.94) compared to urban (USD 30.25 ± USD 61.47, 95% CI: USD 22.66 – USD 37.83) and rural residents (USD 29.33 ± USD 54.15, 95% CI: USD 26.58 – USD 32.06) (Table 1) On examination of the cross tabulation between good health status and social standing, a statistical correlation was found (P = 0.001) (Table 2). Table 2 showed that the worst health was reported by those in the wealthiest quintile (21.8%), the poorest (19.9%), the poor (18.6%) and so on. There is a positive statistical correlation between age- ing and self-reported poor health (or health conditions) of Jamaicans (P = 0.001) (Table 3). Further examination of Table 3 revealed that 10.3% of young adults reported poor health compared to 17.4% of middle aged adults and 43.6% of the elderly Table 1. Demographic characteristic of sample by area of residence. Rural % (n) Peri-urban % (n) Urban % (n) P Age group 0.001 Young adults 38.3 (3833) 41.0 (1760) 39.7 (923) Middle age adults 41.6 (4160) 44.2 (1895) 44.6 (1039) Elderly 20.1 (2010) 14.8 (634) 15.7 (365) Health insurance coverage 0.001 Yes 7.5 (722) 17.4 (726) 20.8 (471) No 92.5 (8969) 82.6 (3442) 79.2 (1788) Gender 0.001 Male 50.4 (5041) 46.8 (2006) 44.3 (1031) Female 49.6 (4962) 53.2 (2283) 55.7 (1296) Per capita income quintile 0.001 1 = Poorest 20% 21.2 (2118) 10.7 (458) 9.5 (222) 2 22.0 (2196) 13.3 (572) 11.2 (261) 3 20.8 (2085) 18.7 (800) 16.7 (388) 4 19.8 (1978) 22.7 (972) 24.3 (565) 5 = Wealthiest 20% 16.2 (1625) 34.7 (1487) 38.3 (891) Marital status 0.001 Married 25.5 (2460) 26.9 (1115) 21.0 (475) Never married 66.6 (6433) 66.4 (2755) 71.6 (1619) Divorced 0.6 (56) 1.0 (41) 1.2 (26) Separated 1.1 (104) 1.2 (49) 1.4 (32) Widowed 6.3 (610) 4.5 (187) 4.8 (108) Crowding mean (SD) 1.77 ± 1.24 1.75 ± 1.28 1.72 ± 1.18 0.216 Crime index 1.74 ± 7.37 2.34 ± 8.08 2.83 ± 9.30 0.001 Medical expenditure1 mean (SD) $ 29.33±$54.15 $ 39.16 ± $85.77 $ 30.25± $61.47 0.012 Income2 mean (SD) $ 5496.12 ± $4860.97 $ 7534.74 ± $5544.26 $ 8779.26 ±$10568.69 0.001 1Medical Expenditure is expressed in USD: United States $1.00 was equivalent to Jamaican $50.97 (during surveyed period) 2Income is expressed in USD: United States $1.00 was equivalent to Jamaican $50.97 (during surveyed period)  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 546 Table 2. Good health status by social standing (Per capita population quintile). Social standing (Per Capita Population Quintile) Good health status 1=Poorest 2 3 4 5 = Wealthiest Total Poor 19.9 18.6 17.9 18.4 21.8 19.4 Good 80.1 81.4 82.1 81.6 78.2 80.6 Total 2738 2975 3208 3413 3883 16217 χ2(4) = 23.273, P= 0.001, contingency coefficient = 0.038 Table 3. Good health status by age group. Age group Good health status Young age(15 to 30 years) Middle age (31 to 59 years) Elderly (60+ years) Total Poor 10.3 7.4 43.6 19.4 Good 89.7 82.6 56.4 80.6 Total 6283 6973 2961 16217 χ2(2) = 1458.12, P= 0.001, contingency coefficient = 0.287 3.2. Multivariate Analysis Table 4 presents information on the variables which are correlated (or non-correlated) with private health insur- ance coverage in Jamaica of people 15 years and older. Using logistic regression, twelve variables emerged as statistically significant determinants of health insurance coverage in this sample (Table 4). These variables are social standing (two wealthiest quintiles: OR = 1.68, 95% CI = 1.23 – 2.30), income (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 1.00 – 1.00), durable goods (OR=1.16, 95% CI = 1.12 – 1.19), marital status (married: OR=1.97, 95% CI = 1.61 – 2.42), area of residence (Peri-urban: OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.199 – 1.749; urban: OR = 1.831, 95% CI = 1.395 – 2.402), education (secondary: OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.20 – 2.06; tertiary: OR = 9.03, 95% CI = 6.47 – 12.59), so- cial support (OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.53 – 0.76), crowd- ing (OR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.02 – 1.28), psychological conditions (negative affective: OR = 0.97, 95% CI = 0.94 – 1.00; positive affective: OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.06 – 1.16), number of males in household (OR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.77 – 0.93), living arrangements (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.41 – 0.92) and retirement benefits (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.03 – 2.35). The model [Eq. 4] had statistically significant predic- tive power (model χ2 = 1604.389, P = 0.001; Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit χ2 = 5.280, P = 0.727), and correctly classified 91.3% of the sample (Correct classi- fication of cases of reported health insurance coverage = 32.0% and correct classification of cases with no insur- ance coverage = 98.3%). 4. DISCUSSION This study found that health insurance coverage is influ- enced by social standing, durable goods, income, marital status, area of residence, education, social support, crowding, psychological conditions, retirement benefits, living arrangements and the number of males in the household, and that those with good health are more likely to purchase health insurance than those with poor health. Continuing, rural residents, elderly and poorest, are the least likely to purchase health insurance coverage in Jamaica. In the literature, it is well documented that the major- ity of uninsured workers in South Dakota were either employed or self-employed [6]. The poor, elderly and many rural residents are more likely to be employed on a seasonal basis in the informal sector, and these occupa- tions and employment types do not have private health insurance, suggesting a further rationale for why unem- ployed people within a particular socio-economic status would be less likely to be holders of health insurance coverage. In this study, it was revealed that more unin- sured Jamaicans were poor, elderly and from rural zones, and these were the ones most likely to be unemployed in Jamaica. The current study was not able to validate the direct claim of employability of the uninsured, but the elderly can indirectly validate the literature that more unemployed people do not have health insurance. In ad- dition to the aforementioned fact, another finding was that poor health is associated with low income, owing to  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 547 547 Table 4. Logistic regression: Private health insurance coverage by some variables. 95.0% C.I. P Odds Ratio Lower Upper Age 0.443 1.00 0.99 1.00 Middle quintile 0.174 1.24 0.91 1.71 Two wealthiest quintiles 0.001 1.68 1.23 2.30 †Poorest 20%-to-poor 1.00 Household Head 0.213 1.80 0.71 4.55 Logged medical expenditure 0.671 1.01 0.95 1.08 Average income 0.009 1.00 1.00 1.00 Durable goods 0.000 1.16 1.12 1.19 Separated or Divorced 0.608 0.90 0.61 1.33 Married 0.000 1.97 1.61 2.42 †Never married 1.00 Peri-urban 0.000 1.45 1.10 1.75 Urban 0.000 1.83 1.40 2.40 †Rural area 1.00 Environment 0.116 0.85 0.70 1.04 House tenure - rented 0.999 0.00 0.00 House tenure - owned 0.950 1.04 0.27 4.03 House tenure - squatted* 1.00 Secondary 0.001 1.57 1.20 2.06 Tertiary 0.000 9.03 6.47 12.59 †Primary and below 1.00 Social support 0.000 0.64 0.53 0.76 Sex 0.722 1.03 0.86 1.24 Crowding 0.018 1.14 1.02 1.28 Crime index 0.652 1.00 0.99 1.01 Land ownership 0.665 0.96 0.79 1.16 Negative affective 0.034 0.97 0.94 1.00 Positive affective 0.000 1.11 1.06 1.16 Number of males in house 0.001 0.85 0.77 0.93 Number of females in house 0.622 0.98 0.89 1.07 Number of children in house 0.438 0.97 0.90 1.05 Living arrangement 0.017 0.62 0.41 0.92 Retirement benefits (1 = yes) 0.038 1.55 1.03 2.35 Poor health status 0.309 0.94 0.83 1.06 -2Log Likelihood = 3982.175 Nagelkerke R Square = 0.359 Model χ2(8) = 1604.389, P-value =0.001 Hosmer and Lemeshow χ2 = 5.280, P = 0.727 Overall correct classification = 91.3%: Correct classification of cases of reported health insurance coverage = 32.0%; Correct classification of cases with no health insurance coverage = 98.3% †Reference group  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 548 the difficulties it creates with accessing crucial health care [6]. This research disagrees with the literature that the poor have lower health statuses, suggesting that they have more health-related conditions than the wealthy. The rich engage in highly involved particular lifestyle practices that expose them to health hazards, and this is not equally comparable to the poor environment of the poor, justifying why they reported the least health status. Pacione [10] has shown that the quality of the physical environment affects the quality of life (or health or wellbeing) of people, but that lifestyle behavioural prac- tices play a significant role in determining one’s health [11] like the physical milieu. [12,13] Moreover, the high cost of health care is a deterrent for the poor to have health insurance coverage; [6] and we concur with the literature as we found a positive statistical association between self-rated health insurance coverage and income. However, in this study we have refined the income vari- able, as there is a ceiling to income and its relation with the purchase of health coverage in Jamaica. The current work has revealed that those in the wealthy-to-wealthiest quintiles were twice as likely to purchase health insur- ance coverage as the poor-to-poorest people. Within the context that those in the wealthiest quintile purchased the most health insurance and indicated the lowest health status, it can be inferred that the purchase of health in- surance is in keeping with their life style and the per- ceived role of income in buying good health, as against preventative behaviour. Health insurance coverage is an elderly phenomenon, [6] and this work does not concur with the literature. The argument put forward is that younger people are health- ier, and so do not see the need to invest in health cover- age, as the risk of becoming ill is low, hence the will- ingness to engage in risky behaviour compared to their older counterparts, [6] suggesting that the futuristic end for health insurance coverage becomes even more criti- cal after 30 years when more people will have families, as well as the fact that the purchase of health insurance may materialize owing to futuristic changes in the eco- nomic circumstances of the individual. There is a statistical relationship between socioeco- nomic conditions and the health status of Barbadians, which is not the case in Jamaica. A study by Hambleton et al., [11] of elderly Barbadians revealed that 5.2% of the variation in reported health status was explained by the traditional determinants of health. Furthermore, when this was controlled for current experiences, the percentage fell to 3.2% (a drop of 2%). When the current set of socioeconomic conditions was used, they ac- counted for some 4.1% of the variation in health status, while 7.1% were due to lifestyle practices compared to 33.5% which were as a result of current diseases. [11] Despite this fact, it is obvious from the data that there are other indicators which explain health status; people do not necessarily pay attention to this fact although they may have more income or access to more economic re- sources. This explains the rationale for more health con- ditions being reported by the wealthiest as well as the group that purchased the most health insurance, where the thinking is that money can buy health. A study published in the Caribbean Food and Nutri- tion Institute on the elderly in the Caribbean found that 70% of individuals who were patients within different typologies of health services were senior citizens. [14-16] Among the many issues that the research reported on are the five major causes of morbidity and mortality, taken from the Caribbean Epidemiology Centre, which are of paramount importance to this discussion, and their in- fluence on the elderly—cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, neoplasm, diabetes, hypertension and acute respiratory infection—and these dysfunctions are highly costly to treat. It should be noted that many of these dysfunctions are owing to lifestyle behaviour. Hence, the purchase of private health insurance coverage by these people when they become old and approach retirement is in keeping with the cost of health care and the high likelihood of becoming ill. Eldemire, [17] on the other hand, opined that the eld- erly are not as sick as some people are making them out to be–“The majority of Jamaican older persons are physically and mentally well and living in family units” [17]; but the fact is they are preparing for the eventuality of health conditions owing to the principle of the degen- eration of the body with the onset of old age. Eldemire is somewhat right. The current study found that for every 1 young adult who reported poor health, there were ap- proximately 2 middle aged adults and 4 elderly persons. Simply put, there were elderly people with poorer health than other age cohorts; but of the elderly, more of them indicated good health status (56.4%). The mere fact of living longer (life expectancy post retirement is at least 15 years), suggests that the aged population will require more for medical care if they become ill. [18] With age- ing the issue is not if they become ill but when. A group of scholars found that there is a direct association between ageing and health conditions, [19] a concept with which this study concurs. And this provides the explanation for the purchase of private health insurance more than other age cohorts, because they are at a dif- ferent stage from other age cohorts in a population. Health conditions are crucial to the purchase of pri- mary health insurance coverage, and this is highlighted by ageing. Eldemire’s works [17,18] have shown that ageing in an individual does not translate to high physi-  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 549 549 cal impairments, but that with ageing come particular changes in the profile of dysfunctions–Alzheimer’s dis- ease, dementia, cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, neo- plasm, diabetes, hypertension and acute respiratory in- fection. [20] A study conducted by Costa [21], using secondary data drawn from the records of the Union Army (UA) pension programme that covered some 85% of all UA, shows that there is an association between chronic conditions and functional limitation–which in- cludes difficulty walking and bending, blindness in at least one eye and deafness [21]. Among the significant findings is–(i) the predictability between congestive heart failure in men and functional limitation (i.e. walk- ing and bending). Although Costa’s study was on men, this applies equally to women, as biological ageing re- duces physical functioning, and so any chronic ailment will only further add to the difficulties of movement of the aged, be it man or woman. One study has contra- dicted the works of Eldemire, and it showed that a large percentage of the elderly suffer from at least one health condition. Women are more involved in health seeking behaviour, compared to their male counterparts, [22] irrespective of the age factor, and this is owing to the cultural back- ground in which they live. Unlike women, across the world men have a reluctance to ‘seek health-care’ com- pared to their female counterparts. It follows in truth that women have bought themselves additional years in their younger years, and it is a practice that they continue throughout their lifetime which makes the gap in age differential what it is–approximately a 4-year differential in Jamaica. In keeping with the preventative care ap- proach to health care, it would be expected that women would purchase more health insurance coverage than them, but this is not the case in Jamaica as gender was not a predictor of health status. However, the more men in a household, the less an individual will purchase health insurance coverage. The Planning Institute of Jamaica in collaboration with the Statistical Institute of Jamaica has shown that while the general health status is commendable, chronic illnesses are undoubtedly eroding the quality of life en- joyed by people who are 65 years and older [23,24]. The JSLC report reveals that the prevalence of recurrent (chronic) diseases is highest among individuals 65 years and over. [23] The findings show that in 2000, the prevalence of self-reported illness/injury for people aged 65 years and over was 41.7%, for those 60 to 64 years it was 27.6% compared to 19.8% for children less than five years old. However, the prevalence of self-reported illness/injury for those 50 to 59 years was 18.8%. Some 36.6% of individuals 65 years and over reported inju- ries/illnesses in 2002 which is a 5.6% reduction in self-reported prevalence of illnesses/injuries over 2000, but the self-reported prevalence of illness/injuries rose by 25.8% to 62.4% in 2004. [25,26] It should be noted here that this increase in self-reported cases of inju- ries/ailments does not represent an increase in the inci- dence of cases, as according to the JSLC for 2004,the proportion of recurring/chronic cases fell from 49.2% in 2002 to 38.2% in 2004 [26]. In addition, the PIOJ and STATIN [23] in (JSLC 2000) opined that individuals 60-64 years of age were 1.5 times more likely to report an injury than children less than five years of age, and the figure was even higher for those 64 years of age and older (2.5 times more). In this paper, the findings con- curred with the literature that health conditions are sig- nificantly greater; but other issues account for them not demanding more health insurance coverage than middle age adults. This is reinforced in the findings that showed that people who received retirement benefits were ap- proximately twice as likely to purchase health insurance coverage as those who did not receive any retirement benefits. Embedded in this finding is the fact that health insurance is a matter of affordability and education, and not illness, which justifies why rural residents had the lowest health insurance coverage, yet still the poorest 20% good health status was greater than that of those in the wealthiest 20%. Statistics revealed that poverty in 2007 for the nation was 9.9%, and rural poverty was 15.3% compared to 4% in peri-urban and 6.2% in urban areas [27], accounting for the lowest private health in- surance coverage in that group. 5. CONCLUSIONS In summary, married Jamaicans are more likely to pur- chase health insurance coverage compared to those who were never married, with urban residents being more likely to purchase health insurance than rural dwellers. An individual who has attained tertiary level education was more likely to purchase health insurance than one with at most primary level education, and those who lived alone were less likely to purchase health insurance coverage than those who dwelled with relatives or fam- ily members. Moreover the wealthiest were more likely to purchase health insurance, but were less healthy, and this indicates that income does not buy good health. Therefore, this study highlighted the need to address preventative care for the wealthiest, and the fact that social support is crucial to health care, along with the fact that medical care costs are borne by the extended family and other social groups in which the individual is (or was) a member, which explains the low demand for health insurance in Jamaica.  P. A. Bourne et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 541-550 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 550 6. DISCLAIMER The researchers would like to note that while this study used secondary data from the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions, none of the errors in this paper should be ascribed to the Planning Institute of Jamaica or the Sta- tistical Institute of Jamaica, but to the researchers. 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to take this opportunity to thank the Data Bank in Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, the Uni- versity of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica for making the dataset (i.e. Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions, 2002) available accommodated the current study. REFERENCES [1] Ettner, S.L. (1997) Adverse selection and the purchase of Medigap insurance by the elderly. Journal of Health Economics, 16(5), 543-562. [2] Liu, T. and Chen, C. (2002) An analysis of private health insurance purchasing decisions with national health in- surance in Taiwan. Social Science & Medicine, 55(5), 755-774. [3] Dong, H., Kouyate, B., Cairns, J., Mugisha, F. and Sau- erborn, R. (2003) Willingness-to-pay for community- based insurance in Burkina Faso. Health Economics, 12(10), 849-862. [4] Carrin, G. (2003) Social health insurance in developing countries: A continuing challenge. International Social Security Review, 55(2), 57-69. [5] Thomasson, M.A. (2006) Racial differences in health coverage and medical expenditure in the United States. Social Science History, 30(4), 529-550. [6] The Lewin Group (2002) Health insurance coverage in South Dakota: Final report of the state planning grant program. South Dakota Department of Health. [7] Varghese, R.K., Friedman, C., Ahmed, F., Franks, A.L., Manning, M. and Seeff, L.C. (2005) Does health insur- ance coverage of office visits influence colorectal cancer testing. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 14(3), 744-747. [8] Kirigia, J.M., Sambo, L.G., Nganda, B., Mwabu, G.M., Chatora, R. and Mwase, T. (2005) Determinants of health insurance ownership among South African women. BMC Health Services Research, 5(1), 1-17. [9] Ahking, F.W, Giaccotto, C. and Santerre R. (2009) The aggregate demand for private health insurance coverage in the US. Journal of Risk and Insurance, The American Risk and Insurance Association, 76 (2), 133-157. [10] Pacione, M. (2003) Urban environmental quality of hu- man wellbeing—a social geographical perspective. Land- scape and Urban Planning, 65(1-2), 19-30. [11] Hambleton, I.R., Clarke, K., Broome, H.L., Fraser, H.S., Brathwaite, F. and Hennis, A.J. (2005) Historical and current determinants of self-rated health status among elderly persons in Barbados. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2005, 17(5-6), 342-353. [12] Bourne, P. (2007) Determinants of well-being of the Ja- maican elderly. Master’s Thesis, The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus. [13] Bourne, P. (2007) Using the biopsychosocial model to evaluate the wellbeing of the Jamaican elderly. West In- dian Medical Journal, 56(Suppl 3), 39-40. [14] Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute (1999) Health of the Elderly. Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute Quar- terly, 32, 217-240. [15] Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute (1999) Focus on the elderly. Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute Quarterly, 32, 179-240. [16] Anthony, B.J. (1999) Nutritional assessment of the eld- erly. Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute Quarterly, 32, 201-216. [17] Eldemire, D. (1995) A situational analysis of the Jamai- can elderly 1992. The Planning Institute of Jamaica, Kingston. [18] Eldemire, D. (1997) The Jamaican elderly: A socioeco- nomic perspective & policy implications. Social and Economic Studies, 46(1), 75-93. [19] Zimmer, Z., Martin, L.G. and Lin, H.-S. (2003) Determi- nants of old-age mortality in Taiwan. Policy Research Division Working Papers Series, 181, Population Council, New York. (http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/wp/181.pdf) [20] Eldemire, D. (1996) Level of mental impairment in the Jamaican elderly and the issues of screening levels, care- giving, support systems, carepersons, and female burden. Molecular and Chemical Neuropathology, 28(1-3), 115- 120. [21] Costa, D.L. (2002) Chronic diseases rates and declines in functional limitation. Demography, 39(1), 119-138. [22] Rice, P.L. (1998) Health psychology. Wadsworth Pub- lishing, Belmont. [23] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (2001) Jamaica survey of living conditions 2000. Kingston. [24] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (1998) Jamaica survey of living conditions 1997. Kingston. [25] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (2003) Jamaica survey of living conditions 2002. Kingston. [26] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (2005) Jamaica survey of living conditions 2004. Kingston. [27] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (2008) Jamaica survey of living conditions 2007. Kingston. |