Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 2012, 1, 25-31 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojmp.2012.13005 Published Online July 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojmp) Emotional Bias in Childhood-Event Interpretation by Adults with Generalized Anxiety Disorder Fanny Marteau1,2, Anne-Sophie Lassalle1,2, Bruno Vilette1,2, Dominique Servant3, Stéphane Rusinek1,2 1Université Lille Nord de France, Lille, France 2UDL3, PSITEC, F-59653 Villeneuve d’Ascq, France 3Hopital Fontan, Lille, France Email: marteau.fanny@yahoo.fr, {anne-sophie.lassalle, bruno.vilette}@univ-lille3.fr, dominique.SERVANT@chru-lille.fr, stephane.rusinek@univ-lille3.fr Received March 21, 2012; revised April 27, 2012; accepted May 24, 2012 ABSTRACT Objectives: It is often stressed that anxiety alters perceptions of the world by way of processes like the rapid detection of threats and the exaggeration of risks. Given that these processes are active during all information processing, they are thought to influence not only the interpretation of current events, but also the recall of past events. In patient’s anamne- sis, we have often attempted to incorporate the events that patients recollect into our functional explanation of their dis- order, forgetting that the meaning of what a patient relates may be intrinsically linked to his/her pathology and patho- logical functioning. We are interested here in potential biases in the events remembered by anxious patients. Methods: We contacted twenty-seven men aged 25 or older suffering from generalized anxiety disorder. They were asked to rec- ollect childhood events from cue words and then rate each remembered event on its subjective emotional valence and intensity, its frequency of recollection, and the vividness of the memory. The responses of the anxious subjects were compared to those of control subjects without psychiatric disorders. Results: Findings seem to show that anxious pa- tients’ memories of childhood events may be impaired by emotional interpretation biases. Indeed, anxious patients re- member more negative events than participants in the control group. The emotional intensity of negative or positive events remembered by anxious patients is also considered more important. Keywords: Generalized Anxiety; Childhood Events; Emotional Interpretation Biases 1. Introduction Many studies on cognitive biases showed that anxious patients focus on threatening stimuli [1-5]. This bias has also been identified in children [6-8]. Moreover, Eysenck [9,10] demonstrated that the principal role of anxiety is to facilitate the early detection and the process of threat- ening signals coming from the environment. This role was originally an undeniable adaptive value, but it can also amplify threats. Thus, in this study we investigated the recall process of past events by anxious patients. We will consider here that memories are constantly undergoing a redefinition process, as Bartlett [11] de- scribed by saying, that for an individual or for a group, the past is constantly being reworked, reconstructed, in accordance with immediate interests. These processes, which we “rewrite” our own history and the events that took place during our childhood, must be regarded as normal and healthy, for the reworking of the past permits better adaptation to personal change. However, in anx- ious patients, this process may lead to an over-focus or over-concentration on negative past events. Indeed the worry, which is one of the most important processes of anxiety, leads to the reinterpretation of past events in a negative way [12-15]. Similarly, the theory of emotional disorders proposed by Beck [16-19], the pio- neer of cognitive therapy, states not only that anxiety- based thought patterns or anxiety schemas affect infor- mation encoding, but also that the encoded information in turn influences the structure of the schemas. It follows that anxiety schemas are continuously being redefined, in such a way that every experienced events are constantly being reinterpreted in order to make them fit into the dominant schema. For twenty years, a significant amount of research showed that emotional events are better recalled than neutral events, whether they were events of everyday life [20] or experimental material such as words [21]. How- ever, there are individual differences concerning the memory of emotional events either negative or positive [22]. For some authors [23], the negative emotional C opyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP  F. MARTEAU ET AL. 26 events lead mechanisms of repression in normal indi- viduals. They estimated that the normal individual seeks to protect himself from negative emotional memories that disrupt his self-esteem and future goals. Similarly, the emotional intensity is attenuated for negative events in order not to destabilize the individual. As the memories of past events influence the self-representation of the person and his future, the person reconstructs the past in order to be consistent with a positive self-image. In con- trast, anxious people have a disturbance of the control function for negative events [24,25]. They would re- member more negative events than positive events and the emotional events would be judged as more intense. Several studies showed that people rethink more often the intense emotional events than the weakly intense ones. The frequent reactivation of memories related to the mechanism of rumination among anxious individuals will accordingly keep them permanently in memory [26]. It appears that the amygdale and stress hormones play a vital role in increasing the storage of emotional events [27]. From a clinical standpoint, the anxious person has difficulty in maintaining a positive self-image and self- confidence in the future due to the persistence of nega- tive memories. Studies concerning recall of negative events among anxious patients are not homogeneous. In fact, other au- thors suggested that anxious patients do not remember more negative events [28,29]. They stated that anxiety is characterized by selective attention to threatening events, but that these negative events tend to be avoided after- wards by the person. There would exist two adaptive styles: repressive people and non-repressive ones. Rep- ressors, who may be either anxious or not anxious, would memorize less negative events and would allocate less effort to retrieve negative information. Thus, repressors would recall less negative memories than non-repressors, either for the period of childhood or the recent past. In the study reported below, we hypothesized that anxiety have an impact on the recall of events stored in memory. To study these biases, we asked adults who suffer from generalized anxiety disorder, and adults with no psychiatric disorders, to remember events from their childhood. Our goal was to determine whether anxious and non-anxious people differ in their emotional judge- ments of past events (emotional valence and intensity), and also whether the features and structure of the mem- ory traces (recollection frequency and vividness of the memory). Under the data of literature, we believe that anxious patients will remember more negative events than positive. They should also judge the emotional in- tensity of the event that they reported, either it was nega- tive or positive as more important? The anxious patients should remember negative events more often and should have a clearer image of negative events. 2. Method 2.1. Participants The study was run on a group of 27 male patients, who were of European origin, with generalized anxiety disor- der without any co morbidity, with age ranging from 25 to 57 years (m = 36.17, sigma = 9.632). They were tested during a consultation at the hospital. We only met pa- tients with generalized anxiety disorder to study the ef- fects of anxiety on recall of emotional events, because we did not want them focus on a particular object. A pre-test showed that people with other forms of patho- logical anxiety tended to spontaneously seek to child- hood events related to their pathology (e.g., events in- volving physiological feelings for patients with panic disorder or contamination events for patients with ob- sesssive Compulsive Disorder). The diagnosis of gener- alized anxiety was made on the basis of DSM-IV criteria [30] assessed using the MINI Test for the French version [31]. The anxious subjects were also given the French Lifestyle Test [32]. The “French Lifestyle” consists of 66 items measuring the degree of anxiety, rated in a di- chotomous fashion “true” or “false”, without the system- atic sense of answers. The general anxiety score is be- tween 0 (very weak anxiety) and 66 (very strong anxiety). The calibration of the test showed that beyond 40, a pa- tient could be regarded as suffering from pathological anxiety, but that beyond 50, the anxiety is “very disab- ling”. According to the authors [32], this test has a good internal validity and a satisfactory fidelity test-retest. This test was the anxiety test most used in this hospital, where patients were tested. Patients whose lifestyle score was below 50 out of 66 were considered ineligible for the study. Among the patients seen in the first interview, four were not included in the study because their anxiety was too high. We selected only male patients to avoid that the sex effects interfering with anxiety during the study. Thus, there is a restriction on the generalization of the results in the general population. All patients were tested over a period of three month (June, July, August), in the same specialized hospital in the management of anxiety by the cognitive and behavioural therapy. It was their first consultation and they had made an appointment on their own initiative after visiting their family doctor. At the time of testing, patients were not hospitalized. Their medications were varied but not disabling. The study was clearly explained to patients to obtain their consent. All patients agreed to participate in the study. The control group was strictly matched to the anxiety patient group on age and socio-occupational category, so this group also contained 27 men, who were of European origin, between the ages of 25 and 57. There are no other variables (IQ, sexual orientation) that could be consid- ered in the matching of these two groups. Control sub- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP  F. MARTEAU ET AL. 27 jects were interviewed first to ensure that they never had a psychiatric disorder. They were tested on the French Lifestyle Test [32] and the STAI [33] to make sure that their trait-anxiety level wasn’t too high. The STAI test of Spielberger [33] is a self-administered questionnaire composed of two scales. The first scale used to measure “state-anxiety” (transitory provision of the individual) and the other measure “trait-anxiety” (corresponds to the personality). Only the measurement of “trait-anxiety” was used. The scores of “trait-anxiety” are between 0 and 80. A score of 50 is considered by the authors [33] as a sign of a pathological anxiety. Subjects with a lifestyle score above 40 out of 66 and a STAI score above 50 (state-scale and trait-scale) were excluded, as recom- mended by the authors of these tests. For reasons having to do with procedures in the hospital where they were tested, the anxious subjects did not take the STAI. The anxiety of the control participants was measured in order to be sure that they had no pathological anxiety. None the control group subjects were excluded following this measure. The study was clearly explained to the subjects to obtain their consent. All subjects agreed to participate in this study. 2.2. Materials and Procedure The experimental materials were designed specifically for this study. They included a list of 15 words likely to evoke childhood memories, along with various scales for evaluating each event remembered. The list of words used as event-recall cues was gener- ated as follows. Nine psychology experts (four research- ers at the University and five clinicians) examined re- ports of interviews of 66 ordinary individuals. From the reports, they selected 46 very general words pertaining to childhood events mentioned by the 66 individuals. The 46 words were then tested on 106 other ordinary indi- viduals, whose task was to say whether or not a child- hood memory came spontaneously to mind when they heard the words. The 15 nouns for which a memory came to mind for 80% of the individuals were used as the items for the experiment. The 15 words were vacation, friend, love, birthday, animals, Christmas, sports, fight, family, home, school, toy, candy, dream, and accident. The words old and car, both of which elicited spontaneous memories in 78% of the individuals, were added to the top of the list to be used later for training. The results obtained for these two words were not included in the statistical processing. Given that these materials were being used here for the first time, this study also served as an initial validation of their use. The words were writ- ten in black letters on white A5-size cards. The subjects first saw the two training words, after which the other words were presented in random order. For each word, the subject was asked to find an event he had experienced before he was 16 years old. A different event was to be related for each cue. If the subject could not think of an event within two minutes, the experi- menter was supposed to go on to the next word, but this in fact never happened. As soon as an event was recol- lected, the subject had to answer four questions on a 10 cm analogical scale. Questions asked participants to rate 1) the valence of the emotion experienced during the event (0 = Negative, 10 = Positive, with a mark labelled “Neutral” in the middle of the scale); 2) the intensity of the emotion experienced during the event (0 = Very Weak, 10 = Very Strong); 3) the frequency of recollec- tion of the event during childhood (0 = Never, 10 = Very Often); and 4) the vividness of the memory today (0 = Very Fuzzy, 10 = Very Clear). For Question 3, the sub- ject was asked to consider the period before age 16, but we used this question to estimate current processing bi- ases. The experimenter was always the same. He was both a clinician and researcher at the University. The procedure was strictly respected and the experimenter was trained in the procedure in order to limit methodo- logical bias. The variables for the study were chosen on the basis of a body of theoretical research. In particular, we consid- ered the work of Plutchik [34,35], who proposed defining the pathological character of emotions in terms of their intensity, and suggested that emotions are opposed in their valence, as in happiness and sadness. These ideas were adopted by Lazarus [36] and also Bower [37,38] in their descriptions of emotional semantic-memory net- works, where repetition of information reinforces its memory trace. The general theory underlying our study was the theory of disordered schemas postulated by Beck [16-19], in which all of these variables are important. But our justifications were also empirical, being based, for example, on Cassidy and Delaoche [39] work showing that for children as young as 4 years-old, the fact of re- collecting something (talking about it again) improved the child’s memory of it; or on Pillemer et al. [40] re- search, where 4-year-old children were able to accurately remember details of a fire alarm in their school that had affected them; or more recently, the study of Andersson et al. [41] on subjects suffering from anxiety-related diz- ziness, where poorer recall was found for autobiographi- cal memories of dizziness induced by positive words. The “emotional shock of an event” can thus be translated by how vividly it is remembered. 3. Results While every subject remembered more negative events than positive ones, anxious subjects averaged as many negative events as controls (t [32] = 1.391, p = 17.38, Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP  F. MARTEAU ET AL. 28 manxious = 7.824, mcontrol = 6.941) (Table 1). For positive events, anxious subjects who recalled fewer positive events than controls. Note also that none of the remem- bered events were rated as strictly neutral. In the processing reported below, each variable was considered as a function of the overall valence of the remembered events. The means and comparisons of means are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In order to avoid statistical artefacts due to the large number of compare- sons, we set a significance level of p = 0.001. For positive events, there was only one significant dif- ference: recollected-event intensity was greater for anx- ious subjects. This same difference existed for negative events, which in addition were rated more negatively by anxious subjects than by non-anxious ones. Thus, re- gardless of event valence, emotional intensity seems to be exaggerated among persons with generalized anxiety, especially for negative events. When comparisons were made across paired positive/ negative events to determine whether any particular class of events had a particular status in memory, no signifi- cant differences were found. Table 1. Mean number of memories, by event valence. Anxious Controls Mean number of negative memories 7.824 (σ = 1.916) 6.941 (σ = 1.784) Mean number of positive memories 7.176 (σ = 1.912) 8.059 (σ = 1.784) Table 2. Means and comparisons of means on positive events. Anxious Controls t32 p Tonality (valence) 8.436 (σ = 1.214) 7.482 (σ = 1.434) 2.094 0.0443 Intensity 8.226 (σ = 0.911) 6.129 (σ = 1.411) 5.148 <0.0001 Vividness 7.212 (σ = 1.907) 7.038 (σ = 1.680) 0.282 0.7801 Frequency of recollection 6.854 (σ = 1.936) 5.775 (σ = 2.134) 1.544 0.1325 Table 3. Means and comparisons of means on negative events. Anxious Controls t32 p Tonality (valence) 1.918 (σ = 1.227) 3.305 (σ = 1.001) 3.609 0.0010 Intensity 8.463 (σ = 1.237) 6.099 (σ = 1.057) 5.993 <0.0001 Vividness 7.886 (σ = 1.515) 6.652 (σ = 1.714) 2.224 0.0333 Frequency of recollection 6.638 (σ = 2.060) 6.687 (σ = 2.231) 0.067 0.9469 4. Discussion The results showed that anxious patients remembered more negative events than positive ones. The emotional intensity of negative or positive events remembered by anxious patients is also considered more important. As we predicted, anxious patients remember negative events more often. There are at least three explanations for the results of this study. Firstly, the anxious subjects may have actually experienced more intense and more emotional loaded events during their childhood, which could even be the reason explaining their disorder. However, comparing the number of negative events experienced for anxious and non-anxious children, Boer and colleagues [42] were unable to really conclude that more negative events had actually occurred in the former group. Alternative possi- bility is that when recalling childhood events, the anxious patients reinterpreted them as more intense and more emotional loaded than they actually were, in which case they were subject to an interpretation bias at recall time. Lastly, as anxious children, these individuals may have interpreted events in this way during childhood, unlike non-anxious children. This means that their anxiety al- ready existed in childhood and caused them to bias their interpretations of information and their encoding in memory. Although Boer et al. [42] findings did not provide a definitive answer, these authors hesitated between sev- eral explanations: a greater number of negative events experienced by anxious children, their greater vulnerabil- ity, and potential recall biases in both the anxious chil- dren and their parents reporting the events. In our ap- proach, which aims to show that anxiety is generated by a processing bias, we lean towards the last two hypothe- ses, which are not in fact mutually exclusive. An earlier study of Rusinek et al. [43] provided an indication sup- porting the idea of an encoding bias among anxious chil- dren. Middle school children were tested on trait-anxiety before experiencing a slightly anxiety-generating event. The event was a speech given by the school principal about the poor grades of certain students and the good grades of others (of course, no names were mentioned). A week later, the students were asked to rate their mem- ory of the event, using the same measures as in the ex- periment reported in the present paper: emotional valence, emotional intensity, recollection frequency, and vivid- ness of the memory. The results showed that the most anxious children, both girls and boys, had already exag- gerated the intensity of the emotion and the valence of the event, they remembered the headmaster’s speech as more intense and more negative than the other children did. These results can be compared to the findings ob- tained by Calvo et al. [44] and by Mathews and Mackin- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP  F. MARTEAU ET AL. 29 tosh [45], who found a threat-confirming anxiety bias on tasks with ambiguous stimuli, especially when the stim- uli were related to the self. It could be, then, that already in childhood, some chil- dren acquire an emotional-event interpretation process that is biased by phenomena such as exaggeration of the intensity and valence of experienced emotions, especially when the events are negative. While certain anxious adults may have lived through very intense, emotionally loaded events, we can also say that the large number of experienced emotional events probably depends both on the interpretation made of them during childhood and on a biased reinterpretation at recall time. There is obviously a methodological problem here, which is the control for the equivalence of memories reported by different sub- jects. We can unfortunately only note this problem, but it lead us to hypothesize without evidence, that different scores in fact reflect differences in information process- ing, not real differences in the characteristics of the ex- perienced events themselves. In addition, there are other restrictions in interpretations. First, the sample size is quite small. Similarly, only men who suffered general- ized anxiety disorders are among them. It should be in- teresting to test women and other anxiety disorders. It shall be interesting to verify that indeed, the specificity of a disorder also leads to recall biases depending on this disorder. Concerning the latter, a more complex proce- dure must be established and future research could be directed towards this prospect. From the clinical standpoint, however, these findings suggest that we exercise caution regarding the life events related by patients. These events certainly have their sig- nificance, since the patients themselves feel they are im- portant, but the filter of anxiety may very well distort them. Thus, it is important to develop and apply new therapeutic interventions that can effectively reduce negative attentional biases [46,47], while treating the problems associated with anxiety disorders. For example, the “Cognitive-Reminiscence Therapy” [48,49], which combines cognitive therapy and reminiscence, appears to be an interesting approach for the treatment of anxious patients. Therefore, the therapeutic work will award a crucial place in the awareness by the patient of his cogni- tive biases. The patient must get into Metacognition and take awareness of the influence of his biases in his vision of past, present and future events. Therefore, it is not the past that will be used to understand the present, but the patient’s cognitive functioning those impacts on his per- ception of past events. Moreover, the work of reminis- cence therapy based on the difficult events of the past can help the patient to be reconciled with certain events in its history. This work of reminiscence therapy pro- motes a questioning of thoughts and beliefs that crystal- lized on the negative. The modification of negative events in long-term memory of an anxious patient will allow him to have a more positive view of himself. The anxious patient can better manage his memories in order to define himself differently. Thus, the anxious person integrate an approach that aims to reduce to the minimum interpretation biases responsible of an anxious and nega- tive perception of self, of the world and of the future. 5. Acknowledgements We wished to thank PhD. student Alhadi Chafi for his support in the writing of this paper. REFERENCES [1] Y. Bar-Haim, D. Lamy, L. Pergamin and M. J. Baker- mans-Kranenburg, “Threat-Related Attentional Bias in Anxious and Nonanxious Individuals: A Meta-Analytic Study,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 133, No. 1, 2007, pp. 1-24. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1 [2] M. W. Eysenck and A. Byrne, “Implicit Memory Bias, Explicit Memory Bias, and Anxiety,” Cognition and Emotion, Vol. 8, No. 5, 1994, pp. 415-431. doi:10.1080/02699939408408950 [3] A. Mathews and B. Mackintosh, “A Cognitive Model of Processing in Anxiety,” Cognitive Therapy and Research, Vol. 22, No. 6, 1998, pp. 539-560. doi:10.1023/A:1018738019346 [4] R. J. McNally, “Cognitive Bias in Panic Disorder,” Cur- rent Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1994, pp. 129-132. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.ep10770595 [5] S. Mobini and A. Grant, “Clinical Implications of Atten- tional Bias in Anxiety Disorders: An Integrative Litera- ture Review,” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, Vol. 44, No. 4, 2007, pp. 450-462. doi:10.1037/0033-3204.44.4.450 [6] P. C. Kendall, J. L. Hudson, E. Gosch, E. Flannery- Schroeder and C. Suveg, “Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety Disordered Youth: A Randomizes Clinical Trial Evaluating Child and Family Modalities,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 76, No. 2, 2008, pp. 282-297. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.282 [7] P. Stallard, “Early Maladaptive Schemas in Children: Stability and Differences between a Community and a Clinic Referred Sample,” Clinical Psychology and Psy- chotherapy, Vol. 14, 2007, pp. 127-139. doi:10.1002/cpp.511 [8] M. W. Vasey, E. L. Daleiden, L. L. Williams and A. Mathews, “Biased Attention in Childhood Anxiety Dis- orders: A Preliminary Study,” Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 2, 1995, pp. 267-279. doi:10.1007/BF01447092 [9] M. W. Eysenck, “Anxiety: The Cognitive Perspective,” Psychology Press, Hove, 1992. [10] M. W. Eysenck, N. Derakshan, R. Santos and M. G. Calvo, “Anxiety and Cognitive Performance: Attentional Control Theory,” Emotion, Vol. 7, No. 2, 2007, pp. 336- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP  F. MARTEAU ET AL. 30 353. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336 [11] F. C. Bartlett, “Remembering,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1932. [12] J. L. Deffenbacher, W. A. Zwemer, M. A. Whisman, R. A. Hill and R. D. Sloan, “Irrational Beliefs and Anxiety,” Cognitive Therapy and Research, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1986, pp. 281-292. doi:10.1007/BF01173466 [13] M. W. Vasey, “Development and Cognition in Childhood Anxiety: The Example of Worry,” Advances in Clinical Child Psychology, Vol. 15, 1993, pp. 1-39. [14] M. W. Vasey and M. R. Dadds, “The Developmental Psychopathology of Anxiety,” Oxford University Press, New York, 2001. [15] K. Verstraeten, P. Bijttebier, M. W. Vasey and F. Raes, “Specificity of Worry and Rumination in the Develop- ment of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Children,” British Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 50, No. 4, 2011, pp. 364-378. doi:10.1348/014466510X532715 [16] A. T. Beck and D. A. Clark, “An Information Processing Model of Anxiety: Automatic and Strategic Processes,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, Vol. 35, 1997, pp. 1110-1119. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(96)00069-1 [17] A. T. Beck, G. Emery and R. L. Greenberg, “Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective,” Basic Books, New York, 2005. [18] A. T. Beck and A. Freeman, “Cognitive Therapy of Per- sonality Disorders,” The Guilford Press, New York, 1990. [19] D. A. Clark and A. T. Beck, “Cognitive Therapy of Anxi- ety Disorders: Science and Practice,” Guildford Press, New York, 2010. [20] C. P. Thompson, J. J. Skowronski, S. F. Larsen and A. L. Betz, “Autobiographical Memory: Remembering What and Remembering When,” Laurence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, 1996. [21] S. Nagae and M. Moscovitch, “Cerebral Hemispheric Differences in Memory for Emotional and Non-Emo- tional Words in Normal Individuals,” Neuropsychologia, Vol. 40, No. 9, 2002, pp. 1601-1607. doi:10.1016/S0028-3932(02)00018-0 [22] J. W. Schooler and E. Eich, “Memory for Emotional Events,” In: E. Tulving and F. I. M. Craik, Eds., The Ox- ford Handbook of Memory, Oxford University Press, Ox- ford, 2000, pp. 379-392. [23] S. C. Brown and F. I. M. Craik, “Encoding and Retrieval of Information,” In: E. Tulving and F. I. M. Craik, Eds., The Oxford Handbook of Memory, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000, pp. 93-107. [24] P. Bayart and S. Rusinek, “Etude des Biais d’Interpré- tation Emotionnelle dans l’Evaluation de Situations Futures chez le Sujet Alcoolodépendant,” Journal de Thérapie Cognitive et Comportementale, in Press, 162. [25] D. A. Hope, R. M. Rapee, R. G. Heimberg and M. J. Dombeck, “Representations of the Self in Social Phobia: Vulnerability to Social Threat,” Cognitive Therapy and Research, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1990, pp. 177-189. doi:10.1007/BF01176208 [26] O. Luminet, E. Zech, B. Rimé and H. Wagner, “Predic- ting Cognitive and Social Consequences of Emotional Episodes: The Contribution of Emotional Intensity, the Five Factor Model, and Alexithymia,” Journal of Re- search in Personality, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2000, pp. 471-497. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2000.2286 [27] R. Adolphs, N. L. Denburg and D. Tranel, “The Amyg- dala’s Role in Long-Term Declarative Memory for Gist and Detail,” Behavioral Neuroscience, Vol. 115, No. 5, 2001, pp. 983-992. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.115.5.983 [28] A. Mathews and C. MacLeod, “Cognitive Approaches to Emotion and Emotional Disorders,” Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 45, 1994, pp. 25-50. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.45.020194.000325 [29] L. S. Newman and D. A. Hedberg, “Repressive Coping and the Inaccessibility of Negative Autobiographical Memories: Converging Evidence,” Personality and Indi- vidual Differences, Vol. 27, No. 1, 1999, pp. 45-53. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00233-5 [30] American Psychiatric Association, “Diagnostic and Sta- tistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR),” Rth Ed. (Text Revision), American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC, 2000. [31] Y. Lecrubier, D. V. Sheehan and E. Weiller, “The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A Short Diagnostic Structured Interview: Reliability and Validity According to the CIDI,” European Psychiatry, Vol. 12, No. 5, 1997, pp. 224-231. doi:10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83296-8 [32] M. Hautekèete, S. Rusinek and D. Hautekèete-Sence, “Un Test d’Anxiété: le Style de Vie,” Vingt-Quatrièmes Journées Scientifiques de Thérapie Comportementale et Cognitive, Paris, 1996. [33] C. D. Spielberger, “Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y),” Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, 1983. [34] R. Plutchik, “The Psychology and Biology of Emotion,” HarperCollins, New York, 1994. [35] R. Plutchik, “Emotions in the Practice of Psychotherapy: Clinical Implications of Affect Theories,” American Psychological Association Press, Washington DC, 2000. doi:10.1037/10366-000 [36] R. S. Lazarus, “Emotion and Adaptation,” Oxford Uni- versity Press, Oxford, 1991. [37] G. H. Bower, “Mood and Memory,” American Psycholo- gist, Vol. 36, No. 2, 1981, pp. 129-148. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.129 [38] G. H. Bower, “Commentary on Mood and Memory,” Behaviour Research and Therapy, Vol. 25, 1987, pp. 443- 456. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(87)90052-0 [39] D. J. Cassidy and J. S. Deloache, “The Effect of Ques- tioning on Young Children’s Memory for an Event,” Cognitive Development, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1995, pp. 109- 130. doi:10.1016/0885-2014(95)90020-9 [40] D. B. Pillemer, M. L. Picariello and J. C. Pruett, “Very Long-Term Memories of Salient Preschool Event,” Ap- plied Cognitive Psychology, Vol. 8, 1994, pp. 95-106. doi:10.1002/acp.2350080202 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP  F. MARTEAU ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. OJMP 31 [41] G. Andersson, M. Fredriksson, M. Jansson, C. Ingerholt and H. C. Larsen, “Cognitive bias in Dizziness: Emo- tional Stroop and Autobiographical Memories,” Cognitive and Behavioral Therapy, Vol. 33, No. 4, 2004, pp. 208- 220. doi:10.1080/16506070410030098 [42] F. Boer, M. T. Markus, R. Maingay, I. E. Lindhout, S. R. Borst and T. H. Hoogendijk, “Negative Life Events of Anxiety Disordered Children: Bad Fortune, Vulnerability, or Reporter Bias?” Child Psychiatry and Human Devel- opment, Vol. 32, No. 3, 2002, pp. 187-199. doi:10.1023/A:1017952605299 [43] S. Rusinek, M. Hautekèete, H. Danes, I. Deregnaucourt and V. Lemmen, “Biais d’Interprétations d’Evénements Scolaires chez des Enfants Anxieux,” Journal de Théra- pie Comportementale et Cognitive, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2002, pp. 59-65. [44] M. G. Calvo, M. W. Eysenck and M. D. Castillo, “Inter- pretations Bias in Test Anxiety: The Time Course of Pre- dictive Inferences,” Cognition and Emotion, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1997, pp. 43-64. doi:10.1080/026999397380023 [45] A. Mathews and B. Mackintosh, “Induced Emotional Interpretation Bias and Anxiety,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Vol. 109, No. 4, 2000, pp. 602-615. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.109.4.602 [46] Y. Barr-Haim, “Research Review: Attention Bias Modi- fication: A Novel Treatment for Anxiety Disorders,” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, Vol. 51, No. 8, 2010, pp. 859-870. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02251.x [47] A. Wells, “Metacognitive Therapy for Anxiety and De- pression,” Guilford Press, New York, 2009. [48] P. Cappeliez, “Fonctions des Réminiscences et Dépres- sion,” Gérontolgie et Société, Vol. 130, 2009, pp. 171- 185. doi:10.3917/gs.130.0171 [49] K.-J. Chiang, H. Chu, H.-J. Chang, M.-H. Chung, C.-H. Chen, H.-Y. Chiou and K.-R. Chou, “The Effect of Reminiscence Therapy on Psychological Well-Being, Depression and Loneliness among the Institutionalized Aged,” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, Vol. 25, No. 4, 2010, pp. 380-388. doi:10.1002/gps.2350.

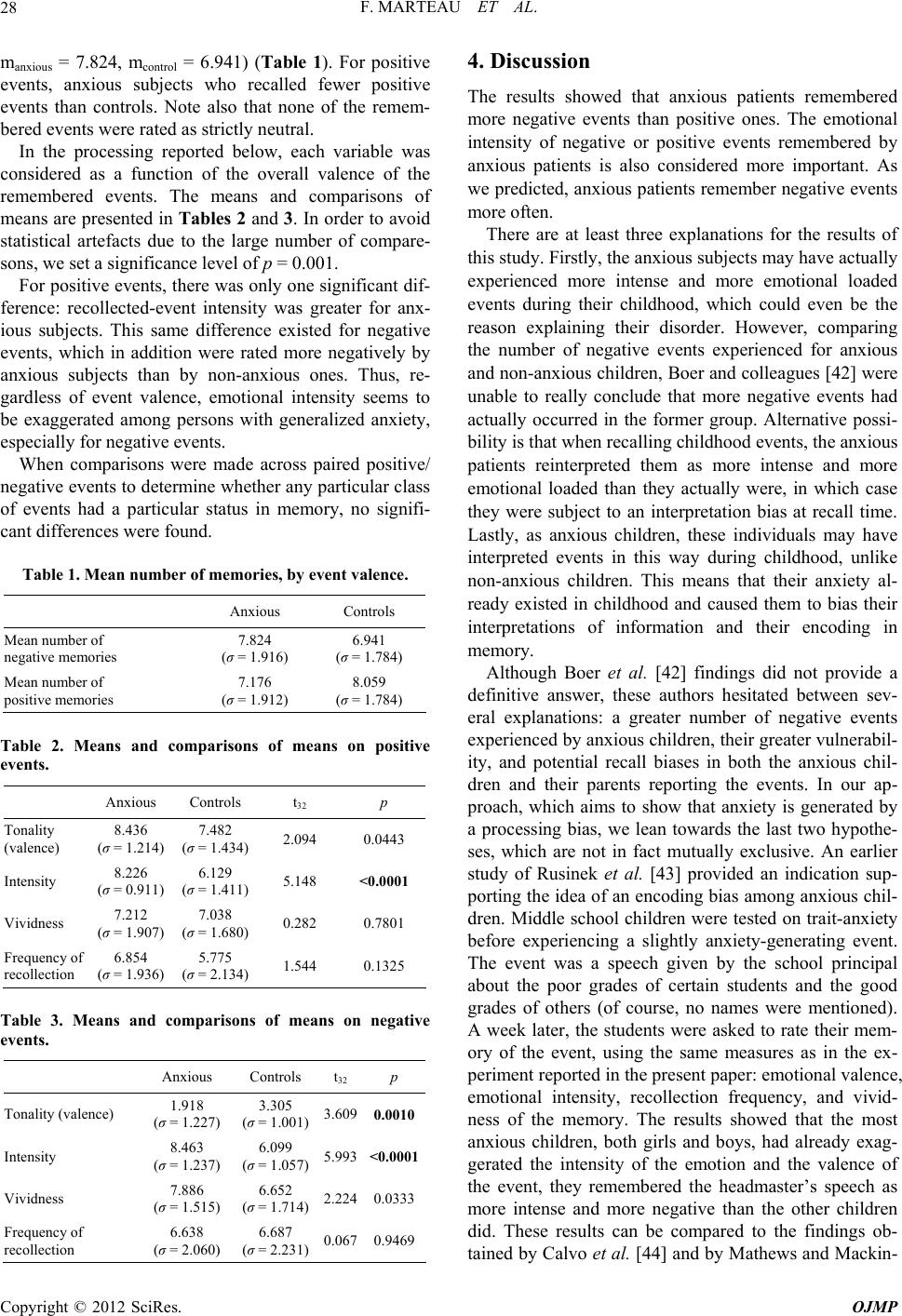

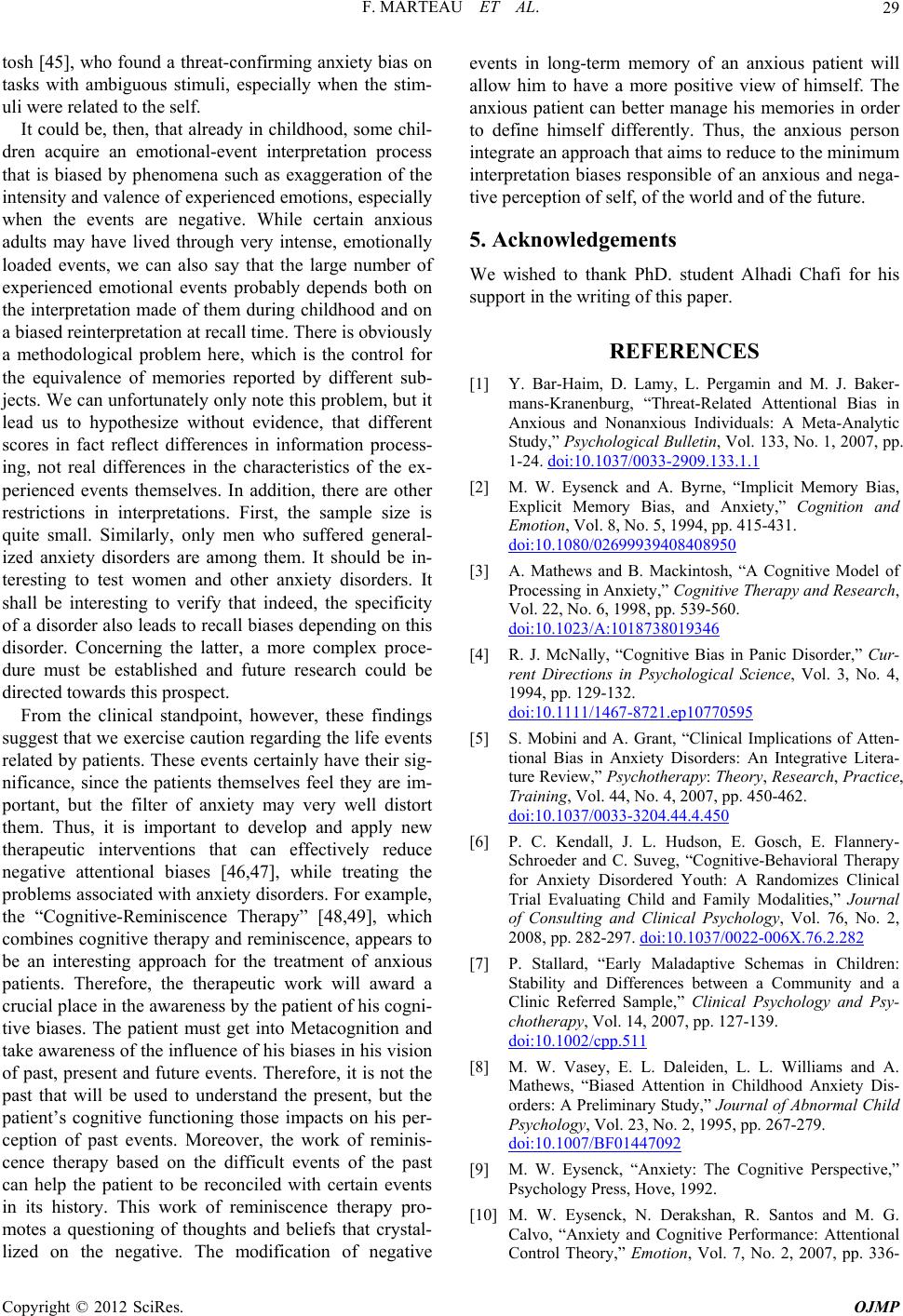

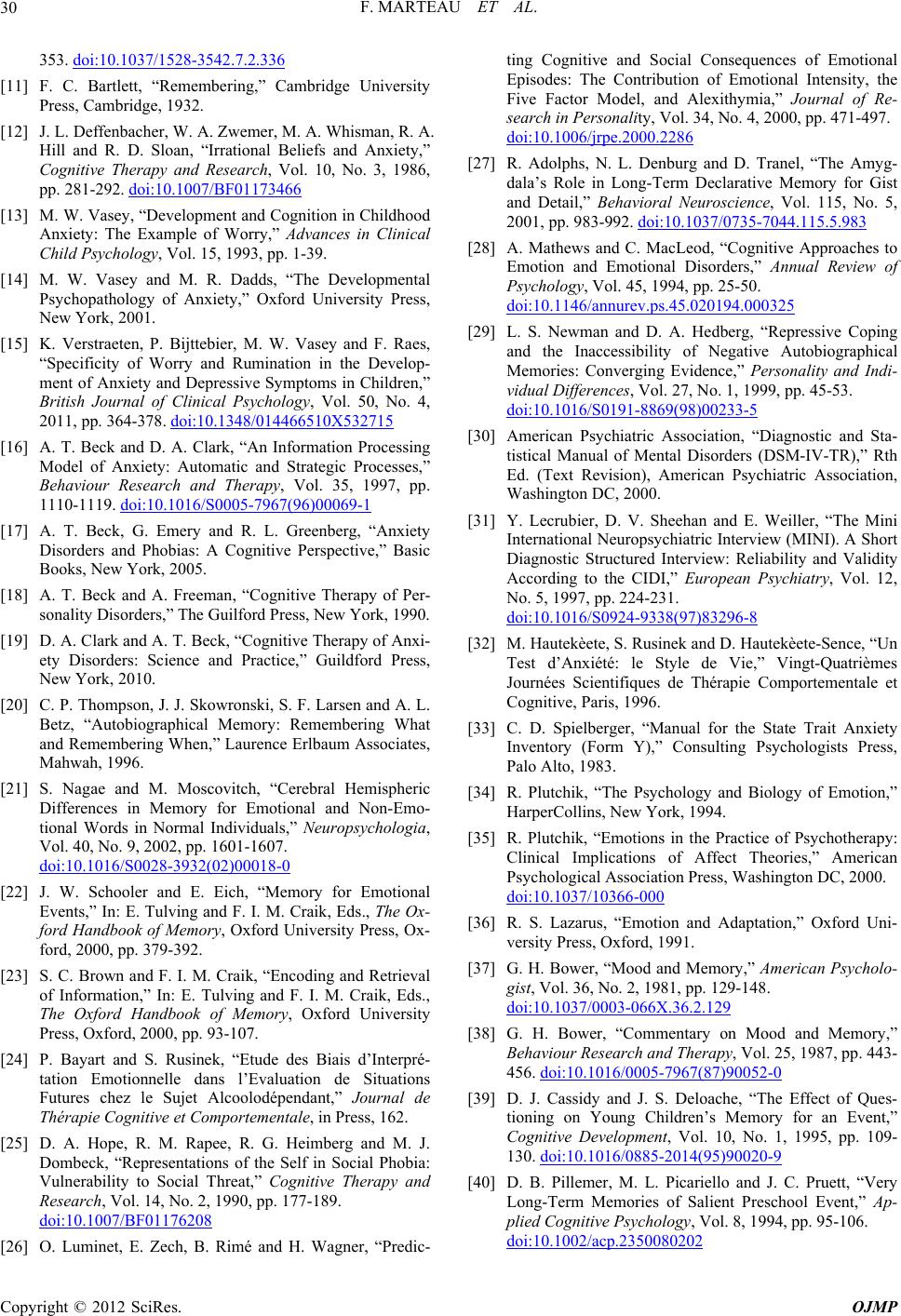

|