Open Journal of Forestry 2012. Vol.2, No.3, 150-158 Published Online July 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojf) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojf.2012.23018 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 150 Peer Influence of Non-Industrial Private Forest Owners in the Western Upper Peninsula of Michigan Jillian R. Schubert1, Audrey L. Mayer1,2 1Department of Social Sciences, Michigan Tech nol ogi cal University, Houghton, USA 2School of Forest Resources and E nv ironmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, USA Email: almayer@mtu.edu Received March 8th, 2012; re vis ed April 10th, 2012; accepted May 8th, 2012 Understanding how non-industrial private forest (NIPF) owners gain and share information regarding the management of their property is very important to policy makers, yet our knowledge regarding how and to what degree this information flows over privately owned landscapes is limited. The work described here seeks to address this shortfall. Widely administered surveys with close-ended questions may not adequately capture this information flow within NIPF owner communities. This study used open-ended questions in interviews of clusters of NIPF owners to determine whether and to what extent owners in- fluence each other directly (through conversations or referrals to sources of advice) or indirectly (through observation of management). We obtained data from thirty-four telephone interviews with owners of NIPF properties in the Western Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and analyzed the data using open coding. Roughly half of the forest owners we interviewed were influenced either directly or indirectly by other members of their NIPF communities. Reasons for owning forests (such as privacy, hunting and nature recreation, and economics) also influenced owners’ management behaviors and goals. This peer-to-peer flow of information (whether direct or indirect) has significant implications for how to distribute man- agement and programmatic information throughout NIPF owner communities, and how amenable these communities may be to cooperative or cross-boundary programs to achieve ecosystem and landscape- scale goals. Keywords: Communication; Information; Management; Landowners; Opinion Leader; Policy Introduction More than half of the 751 million acres of forest in the United States is privately owned, 35% by non-industrial private owners (Butler et al., 2005; Butler, 2008). Non-industrial pri- vate forest (NIPF) refers to forest owned by private entities, such as individuals and families, that do not fall under the category of vertically integrated timber companies (Best & Wayburn, 2001; Butler, 2008). These owners are also referred to as “small-scale forest owners” or “family forest owners” in the more positive sense (as the term defines what they are, rather than what they are not; Fischer et al., 2010). These own- ers comprise 92% of all private forest owners and own 62% of private forest in the United States (Butler, 2008). In the aggre- gate, activities undertaken by forest owners have the potential to drastically impact the forested landscapes of the United States, along with its associated biodiversity and ecological services (Erickson et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005; Gustafson & Loehle, 2008; Ma et al., 2011). The need for more information before engaging in manage- ment activities for ecosystem-scale benefits, and/or entering into programs, is a recurrent theme in many studies of private forest owners (Finley et al., 2006). Regardless of whether more information is needed on ecosystem management (Jacobson, 2002), collaborative management across boundaries (Finley et al., 2006), the effects of management programs (Vokoun et al., 2010), or whether that information comes from professionals (Creighton et al., 2002) or peers (Knoot & Rickenbach, 2011; Ma et al., 2011), there seem to be few owners in these commu- nities who are not interested in more information (Finley et al., 2006). Different forest owners may require different kinds of information (Finley et al., 2006; Gootee et al., 2010), conveyed in different formats (Hujala et al., 2009), from different kinds and numbers of sources (West et al., 1988; Lönnstedt, 1997), depending upon owner characteristics such as age, education, absenteeism, land tenure, and values. Large surveys such as the National Woodland Owner Survey (NWOS; Butler et al., 2005), and smaller efforts (e.g., West et al., 1988) have indicated that NIPF owners may get at least as much information and advice on management and voluntary program enrollment from neighbors, friends, and other NIPF-owning peers, as from pro- fessional foresters at public agencies and pr i v a t e i n d u s t ry. However, more attention has been placed on the relative weight these information sources are given by NIPF owners, than how this advice is used and spread to other NIPF owners (e.g., Ma et al., 2011). According to the NWOS, the preferred sources of management advice for NIPF owners are natural resources professionals (Butler et al., 2005). Although NIPF owners may claim to want and take advice from natural re- sources professionals more frequently (although see Ma et al., 2011), they influence and are influenced by the landowners around them. However, previous research has shown that ad- vice from friends and family may be applied more often than advice from natural resources professionals, and that landown- ers may trust information from other landowners rather than experts (West et al., 1988; Ma et al., 2011). Rickenbach et al.  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER (2005) found that NIPF owners may make management deci- sions based on their opinions of neighbors’ management out- comes without actually asking neighbors about their manage- ment. No study has yet made a distinction between direct in- formation (given verbally or in writing from one person to an- other) and indirect information, which can be gathered through observing the efforts and effects of forest management on other forested properties. There is a variety of state and Federal programs in place to encourage management, discourage forest conversion, and pro- vide tax incentives to NIPF owners, and enrollment in these programs is mostly voluntary. Although voluntary programs may seem to avoid many of the legal entanglements that plague regulation or mandatory programs, the voluntary nature of the program requires a greater burden on both the landowner and the administrative organization, in terms of time, financial re- sources, education and knowledge of the problem; common enrollment obstacles for many voluntary programs (Lieberherr, 2011). Most of these programs contain an education component about land management and management programs for poten- tial and existing participants (Greene et al., 2005; Ma et al., 2011). Generally, many NIPF owners are unaware of these kinds of programs and their potential benefits, leading to poor participation (Nagubadi et al., 1996; Greene et al., 2004; Kil- gore et al., 2007). For example, in Michigan, the Commercial Forest program requires the landowner to take the initiative to obtain a management plan and enroll their forested property in the program (eligible property must be at least 40 contiguous acres); less than 0.3% of the 498,000 owners are enrolled in the program (Butler, 2008; MI DNR, 2011). Fortney et al. (2011) found that the majority of non-participants in West Virginia’s Managed Timberland program, a tax incentive program with the goal of retaining private forest land, did not know about the program and many would have participated had they been aware of it. Those landowners that did participate in the pro- gram became aware of it primarily from foresters. Rossi et al. (2010) found that foresters were the most important source of information about a Southern Pine Beetle prevention cost-share program in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia, and foresters needed to be more active about recruit- ing landowners to increase participation. If forest owners do not view DNR foresters as valuable sources of advice, their know- ledge of these NIPF-targeted programs is likely to remain low, unless there are other information sources that they use more frequently. Here we present research on NIPF owners of the Western Upper Peninsula of Michigan and how they communicate about forest management and programs with neighboring NIPF own- ers. We collected data from 34 telephone interviews with NIPF owners; we believe the use of open-ended interview data, in- stead of the more commonly used mail surveys, provided new insight. The goal of this research was to understand the way information moves through NIPF owner-dominated landscapes, and to provide recommendations to policy implementers on how to best reach these owners with information. Knowledge about how information flows among private landowners is an emerging critical need, as the diversity and functioning forested landscapes in many parts of the world are impacted by the col- lective decision-making of thousands of private forest owners (Erickson et al., 2002; Fischer et al., 2010; Knoot & Ricken- bach, 2011). Methods Our study area was the Western Upper Peninsula of Michi- gan, encompassing eight counties: Baraga, Dickinson, Gogebic, Houghton, Iron, Keweenaw, Marquette, and Ontonagon. There are approximately 30,000 NIPF owners in this area (B. Butler, pers. communication), with the potential for a substantial in- crease in number due to industrial timberland divestiture and subsequent parcelization (Froese et al., 2007). While the eco- nomic importance of the timber industry has declined in the past several decades (Froese et al., 2007), ecosystem-based tourism (e.g., hunting, fishing, recreation) remains an important sector of the regional economy (Nelson, 2001). This sector is directly impa c ted by forest management at the landscape scale. We compared digitized parcel maps to classified LANDSAT imagery to identify forested areas with clusters of NIPF owners. These parcel maps (obtained from Rockford Map Publishers, Rockford IL) included the names of owners, which we then used in searches of online and paper directories to find contact information. All interviewees were guaranteed that their identi- fying information would be kept in confidence. As with Gootee et al. (2010), we found that interviewees were not comfortable having their interview recorded (given the subject matter of their interactions with neighboring forest owners), and so we took detailed notes (confirming our notes during the interview if there were difficulties or discrepancies with the notes) and the notes were converted into a nearly-complete interview ses- sion immediately after each interview. All interviews were assigned a number, so that owner names were not linked to interviews; interviewee numbers are referenced in the Results section. In the preliminary round of interviews conducted in summer 2010, we chose two landowners per community at random. We considered a community to be a cluster of NIPF properties that were typically surrounded by other land uses, such as farms or publicly owned forests. We contacted one of these potential interviewees and asked them to participate; if they declined or could not be reached, we called the second landowner. We used a snowballing method with successful contacts to find other potential interviewees within the community who may not have been listed in directories, and it gave us some indication of the social network of these landowners. Snowballing is the process of asking interviewees to recommend others to potentially be interviewed (Patton, 1992). In previous research, snowballing has been used to obtain interviews when there is no list of po- tential interviewees available (Gan et al., 2003). Snowballing has also been used to gain new or differing ideas and opinions (Rickenbach & Reed, 2002). Ultimately this method was un- successful; only four interviewees recommended neighbors and only one that was recommended agreed to participate. To as- sure a sufficient sample size, we did use this method to some extent for the second round of interviewing. For subsequent interviews, we contacted all individuals with listed phone numbers in the chosen communities, but still asked to recom- mend neighboring landowners for interviews. The interviews were semi-structured with a mix of open and close-ended questions. The preliminary interviews had more close-ended questions, while the second round of interviews consisted of mostly open-ended forms of the same questions (see Appendix). We made these adjustments to better reflect the kinds of data we had received in the first interviews. We ana- lyzed the data collected from the interviews using two types of Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 151  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 152 coding. First, we coded the interviews using predetermined codes. This served to index the data and create categories (Bab- bie, 2010). We also used an open-coding method. Open-coding is accomplished by careful examination of the data for ideas that were not originally considered (DeWalt & DeWalt, 2002). We used Pearson’s chi-squared tests to determine whether the characteristics of owners (such as resident versus absentee owner) influenced their sources of management information. However we also used qualitative methods to identify opinions about information sources that may be influenced by attitudes or other ownership aspects that cannot be quantified. Qualita- tive approaches have become more common in studies of landowner behavior and preferences (Fischer et al., 2010). Results We conducted thirty-four interviews in total: twelve during the preliminary round and twenty-two from the second round of interviewing. An additional 65 landowners we tried to contact either refused an interview (16), did not answer the phone (44), or had a disconnected phone line (5). We had great difficulty to generate a larger sample of interviews given the large number of seasonal residences without listed landlines (or with land- lines that remained unanswered), and an inability to determine the owner of a particular property given numerous listings for the same name (or first initial and last name), particularly among the Finnish ancestry community. Our set of interviewees was fairly typical in their distribution of characteristics when compared to the averages found by the NWOS. The mean age of the interviewees was 56.7 years with an average of 3.8 years of post-high school education. This is close to the mean age of NIPF owners in the western Upper Peninsula, though the mean level of education was higher than the general population in this area as reported by the NWOS (B. Butler, pers. communication). Twenty-four of the interviewees were absentee owners, and 26 of the interviewees were male. Our interviewees owned an average of 245.5 acres for 21.7 years, which was also consistent with the NWOS data for the western UP. Also consistent with NWOS averages, the new owners we interviewed were less likely to live on their land than the long-term owners, and owners with larger properties were more likely to have a management plan than those with smaller holdings. However, more of our interviewees had pur- chased (28) (rather than inherited (6)) their forested properties than the average population of owners in the area. Quantitative Analysis of Information Sources The majority of the results from the quantitative analysis were not statistically significant (at p < 0.05); this was not un- expected due to the small sample size. However, we did ob- serve some significant correlations (Table 1). For continuous data, such as tenure, we reclassified it into the categories of short term (less than 10 years) and long term (10 years or more) in order to perform Pearson’s Chi-Squared tests, The other data used for the Pearson’s chi-squared tests were already categori- cal; the categories included purchaser/inheritor and resident owner/absentee owner. We also used regression analysis, so the distance to NIPF property did not have to be categorized. Residency on their forested property had little impact on peer influence; similar proportions of both residents and non-resi- dents influenced or were influenced by their neighbors. Land- owners that resided on their property were more likely to rec- ommend neighboring forest owners for interviews. However, length of ownership (tenure) was negatively correlated with taking management advice from neighbors or knowing neigh- boring landowners’ management practices. Owners that had recently acquired their properties were less likely to have in- fluence on or be influenced by their neighbors than long-tenure owners; 54% of interviewees that owned their property for ten years or more had been influenced by or influenced neighbors, while the same was true for only 38% of short-term owners. Interviewees that purchased their property (as opposed to in- heritors) were more likely to participate in programs for NIPF owners and to know how their neighboring owners manage, but were less likely to actively manage. Participation in NIPF pro- grams with no active management often indicated goals related to nature conservation. Qualitati ve Review of Influ e nces on M anagement Roughly half of the interviewees were influenced by their NIPF owner neighbors, both directly (through conversations about management or referrals to foresters or others sources of advice), and indirectly (through observations of neighbors’ management). Of t he interviewees influenced by or influencing neighboring landowners in some way, 32% were directly in- fluenced, 38% were indirectly influenced, and 21% were influ- enced in both ways by their neighbors. One extreme example of a landowner having both types of influence was interviewee #19. He spoke with neighboring landowners (who were also his relatives) about his management, and they managed similarly and used the same forester. He and his relatives also influenced other NIPF owners directly by recommending the same forester to another owner. This owner also engaged in some collabora- tive management with neighboring NIPF owners. Interviewee #19 and his relatives were influenced indirectly by other NIPF Table 1. Summary of significant results and their relationships. Characteristic 1 Characteristic 2 Statistical Relationship Management Advice Negative (p = 0.02) Tenure Neighbor Management K nown Negative (p < 0.001) Size of Forested Property Management Plan Positive (p = 0.023) Resident Owner (not absentee) Neighbor Recommendation for Interview Positive (p = 0.002) Neighbor Management K nown Positive ( p = 0.018) Active Management Negative (p < 0.001) Purchaser ( not inheritor) Program Enro ll ment Positive (p < 0.001)  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER owners as well; he and his relatives only harvested during the winter after observing the damage to soils from summer har- vests on a neighboring property. Indirect influence from neighboring owners can discourage people entirely from managing. Interviewee #6 said that she would not log her land because of the result of logging on her neighbor’s property. She said, “They made a mess of their properties. They just had them logged and destroyed a lot of trees. They were going after big ones and left others lying down and drove over them with bulldozers. It looks horrible, at least we think so”. Interviewees were not always aware of their influence on other NIPF owners, and sometimes had complex information dynamics with their neighbors. For example, interviewee #11 was a forester whose neighbors came to him for advice; how- ever, he was unsure whether they acted on his advice. He said of his influence on his neighbors, “They’re only interested in if theirs can be cut and how much money can be made. I men- tioned what I’d like to do (on my property) because I under- planted white pine. They think I’m nuts and it’s a waste of time and money”. He also decided to use particular logging compa- nies on his property based on the quality of the work they had performed on a neighbor’s property (in his own opinion). This is an example of a landowner who may directly influence the management on his neighbors’ properties, and is indirectly influenced by their management decisions. However, in com- parison to their neighbors, foresters probably have far more knowledge about the variety of management techniques and goals that are possible, and so they are likely to be more trusted or sought out as sources of information than other neighbors without similar experience. Values That May Affect Peer Influence and Information Flow We identified several themes that emerged as influences on NIPF owners’ management from the open-coding of responses. These issues have some bearing on the spread of information through these NIPF communities and participation in NIPF- targeted programs. Here, NIPF programs are those that are specifically targeted to private landowners who do not own a mill or other industrial facility, and are not incorporated as a profit-oriented organization; some of these programs may cap the total amount of land that can be enrolled by a landowner. These programs are almost always voluntary, and can include incentives such as free education, technical assistance from a professional forester, cost-share for management activities or tax abatements (Greene et al., 2005; Mayer & Tikka, 2006). These themes have also been found in other studies of NIPF owner communities in the United States. Privacy: Many of the interviewees had purchased their prop- erty as a residence, but they specifically purchased a rural, for- ested parcel because they valued privacy . Creighton et al. (2002) and Butler and Ma (2011) also found that aesthetics and privacy are major drivers in the decision to purchase an NIPF property in the region. For example, interviewee #12 said of purchasing her property, “We really like the natural beauty. In Baraga (where it’s at), it’s unspoiled by buildings and houses. We like the fact that it’s remote”. For example, interviewee #5 implied that the value he placed on privacy impacted his management. He also stated that he would not manage in a way that impacted his neighbors’ viewsheds. This concern for neighboring proper- ties may not be rare; Vokoun et al. (2010) found that nearly 41% of NIPF owners in Virginia considered how management of their land might affect the qualities of their neighbors’ prop- erties. Privacy concerns also influenced participation in NIPF programs; a majority of the first round of interviewees men- tioned loss of privacy as a concern with participation. We spe- cifically asked the second round of interviewees what they saw as benefits and downfalls to these NIPF programs. Five of the twenty-two responded that a perceived loss of privacy (through forfeiture of property rights or control over property) was a barrier to participation (several mentioned Michigan’s Com- mercial Forest program specifically). Value of Nature: Many of the interviewees expressed that their desire to own NIPF stemmed from the way they viewed nature. Interviewee #7 communicated the value he placed on nature as well as his desire for privacy when asked how many neighboring landowners he knew. He said, “At home, we know all of them unfortunately. It’s not wild enough for me.” When asked about his management of his second property, he said, “We like the property the way it is. There are wildlife like you wouldn’t believe. Everything available are on there. I wish it was never logged”. Interviewee #5 stated that he and his wife purchased their property as a “private nature sanctuary”. The interviewees’ understanding of nature also impacted their opin- ions regarding land management. Interviewee #4 said that there is no reason to manage and the only reason people manage is for money. The opposite viewpoint was also expressed; some of the interviewees believed that forests required management to be healthy. Interviewee #3 said that he harvested his property because he didn’t want the mature trees to go to waste, where “waste” was intended as a loss to nature, rather than an eco- nomic loss. Recreation and Wildlife: More than half the interviewees (57%) stated that their purchase of NIPF property was driven by recreational activities. Hunting was the most common rec- reational use mentioned by interviewees, and some specifically mentioned hunting for white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virgin- ianus). Butler and Ma (2011) found recreation to be one of the most common reasons for owning forested property in the northern US. New owners in particular have been found to place more value on recreation than traditional owners (New- man et al., 1996). While many interviewees that hunted on their properties did not actively manage their NIPF, they had unique relationships with their neighbors due to these hunting activities. Interviewee #18 managed specifically for wildlife habitat and was influenced by her neighbors. She said that she and her neighbors “…don’t work together, though, except for deer. We try to work together on the bucks we shoot”. While they were not collaboratively managing in the traditional sense, they were communicating and collectively altering their activities. Jacob- son (2002) found that the most influential reason for coopera- tion among NIPF owners was often for hunting and wildlife management. Alternatively, one interviewee (#7) would not enroll his land in the Commercial Forest program or allow pub- lic hunting on his property because he believed that it would lead to trespassing, although he did not have any conflict with hunting per se. Economics: Many purchased their property as an investment and expected financial gain from timber harvests at some future date. A few landowners mentioned that selling some or all of their property was in their long term plans, but differed on whether that plan influenced how they managed (or did not Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 153  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER manage) the prope rty to enhance its valu e for future sale. Some interviewees had specific management goals, but let financial influences dictate their management practices. Interviewee #9, for instance, prioritized hunting and wildlife habitat, however he did harvest some high value tree species for timber. Inter- viewee #21 followed a management plan, but let the timber market overrule his plan. He said, “I left the hemlock because there was no market for it, and for wildlife habitat”. Financial concerns also prompted communication among neighboring forest owners. The neighbors of interviewee #11 (a forester) came to him for management advice; he believed that his neighbors’ reason for seeking advice was to make money from their land. Program participation was also influenced by financial con- cerns. The most commonly mentioned program benefits that were perceived to be advantageous were tax incentives. When asked if he had a management plan, interviewee #19 stated, “Yes, it’s simple. You can’t apply to put your land in Commer- cial Forest without a written plan”. When he was asked why he enrolled in Commercial Forest, he stated that he did so for the tax incentive. Several interviewees explicitly mentioned or discussed NIPF programs, and most of these programs used tax incentives or cost share to encourage participation. One inter- viewee participated in the US Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program, another in Michigan’s Forest Stewardship Program, and several others had at least some land enrolled in the Commercial Forest program. Mistrust of Government: The interviewees in this research primarily referred to the Michigan Department of Natural Re- sources (DNR) when expressing their distrust of government. They viewed government involvement on their property as limiting. For example, interviewee #11 explained that he did not participate in any government-run assistance programs because “I don’t want the government involved in telling me what to do. [The government] places restrictions on [my land]”. Interviewee #19 had stronger opinions about the DNR, ex- pressing an opinion that their primary goal was to collect fees from forest owners. Previous NIPF literature has identified a mistrust of government programs and officials in general in NIPF owner communities, even if specific individuals from these agencies were trusted (West et al., 1988; Brook et al., 2003; Shandas, 2007; Ma et al., 2011). Gootee et al. (2010) found that NIPF owners were not necessary distrustful of ad- vice and information from these professional sources, but rather were put off by the one-directional, hierarchical manner in which this advice was given to them. Owners’ efforts to obtain information from neighbors, relatives, and other NIPF owners were more reflective of the need for a two-way dialogue than from any general mistrust of professionals. Discussion Our study found that a considerable number of NIPF owners may be influenced both indirectly and directly by their neigh- bors regarding forest management approaches. The peer-to-peer flow of information across the privately owned forested land- scape can be inferred from previous research but was explicitly examined here. According to the NWOS, more Michigan NIPF owners get advice and management information from state and federal agencies or private consultants than from other sources (Butler et al., 2005). “Other forest owners” were the manage- ment advice sources for approximately 18% of Michigan NIPF owners surveyed, less than state (41%), but roughly equal to federal (20%) and private (22%) foresters (Butler et al., 2005). Likewise, using a survey West et al. (1988) found that NIPF owners in northern Michigan were as likely to seek advice from friends and neighbors (22.2%) as from state and federal (27.6%) or private (24.2%) foresters. However, while West et al. (1988) do not address whether information was received from multiple sources, it is apparent from the NWOS results that owners are receiving information from multiple sources simultaneously, although it is not possible to discern from the aggregated results which sources owners are more or less likely to use in combi- nation. Our interviews suggest that peers, neighbors and family members may provide more information than these surveys indicate, at least among owners in the western Upper Peninsula. The NIPF owners that were not influenced by or influencing their neighbors’ management behaviors typically did not con- duct active management on their NIPF property (although some owners may be actively deciding not to manage; e.g., Inter- viewee #4; Erickson et al., 2002). This result echoes the find- ings of Finley et al. (2006), where NIPF owners who had no interest in cooperating with neighboring landowners were far less concerned about not knowing neighbors and more con- cerned about privacy; privacy concerns could be interpreted as not wanting to share information with neighbors or government agencies. We found that interviewees did not immediately consider in- direct information received from neighboring properties, opin- ion leaders and social norms in NIPF communities when an- swering direct questions about information sources, but re- vealed considerable influence from these sources over the course of the entire interview. An opinion leader is defined as a person well respected by their community and often holding a local leadership position; most importantly, they are thought of as good land managers (Rogers & Schoemaker, 1971). Opinion leaders are thought to be innovative and influential, which could lead to many of their surrounding landowners adopting the practices they advocate (Haymond, 1988; West et al., 1988). Social norms are generally accepted practices and behaviors in a community or culture that influence individual behaviors, while social influence is when a majority pressures a minority to conform to a certain behavior (Cialdini et al., 1998). These leaders and norms contribute to the peer influence that has been observed to have a greater effect on management than advice and information from forestry professionals (West et al., 1988; Ma et al., 2011). Mail surveys asking mostly close-ended ques- tions, such as the NWOS (originally designed to reflect com- mercial forestry goals), may miss these subtle influences that are better illuminated by more open-ended, qualitative instru- ments and analyses (Bliss & Martin, 1989; Lönnstedt, 1997; Tikkanen et al., 2006; Hujala et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2010; Gootee et al., 2010). That so many NIPF owners seek out the opinions of other forest owners for management advice emphasizes Gootee et al.’s (2010) and Ma et al.’s (2011) calls for programs that use peer-to-peer learning to distribute information about manage- ment and programs to the NIPF community. These programs include the “Woods Forum” in Massachusetts, Oregon’s Master Woodlands Manager Program, and Pennsylvania’s Volunteer Initiative Program (Reed, 2001; Jacobson, 2002; Ma et al., 2011). This two-way flow of information among peers, along with the different forms of information flow (direct and indirect) identified in this study, will have a considerable influence on Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 154  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER the success of newer cross-boundary and cooperative programs for managing for goals other than timber production in ecosys- tems and landscapes (Creighton et al., 2002; Jacobson, 2002; Fischer et al., 2010; Vokoun et al., 2010). How might the large influx of urban, absentee owners into forested landscapes integrate into these information flows? The number of non-resident owners has increased significantly in the Upper Peninsula; the number of owners living one hundred miles or more from their timberland increased by 31% from 1981 to 1994, and about 35% considered their NIPF a secon- dary residence by 2006 (Leatherberry et al., 1998; Potter-Witter, 2005; B. Butler, pers. comm.). This trend is dominated by ur- ban landowners residing far from their forest, and is accelerated by parcelization of large, industrial tracts which are purchased by new owners. Parcelization, the subdivision of large tracts of forest into multiple ownerships, can lead to habitat fragmenta- tion when these parcels are managed differently (Mehmood & Zhang, 2001). This in turn may have an effect on wildlife and ecosystem services (Erickson et al., 2002); over half of the listed threatened and endangered species in the United States utilize private lands (Irland, 1994). The results of our study suggest that we should not see a dramatic difference in how absentee owners get their manage- ment information, as we found no difference among resident versus absentee owners regarding whether and how they were influenced by neighbors (although we interviewed more absen- tee than resident owners). However, we expect that new owners are much less likely to be integrated into the NIPF owner community than older owners, regardless of residency, simply due to a lack of time to become acquainted with neighbors; those we interviewed were far less likely to know their neigh- bors or get management information from them. Alternatively, Lönnstedt (1997) found that new owners were more often ad- vised by neighbors or forest-owning family members than by professionals. Therefore, general information campaigns in NIPF communities may reach absentee owners as their owner- ship tenure increases, but reaching new owners may require additional effort. The value the interviewees placed on nature and their under- standing of nature was a major determinant in management. Some interviewees purchased their land for residences, but still logged because they felt that the forest “needed” to be managed. Alternatively, some interviewees believed that the forest didn’t need to be managed and would take care of itself. Information regarding management programs may reach owners of both opinions but may be much less effective for the latter case, re- gardless of the information source. Other NIPF owners seemed to manage solely for economic reasons despite their stated goals or reason for obtaining an NIPF property. While they may value other aspects of their NIPF properties or the opinions of others, they either cannot or will not forego the economic bene- fit of harvesting timber on their property. Finally, a mistrust of government agencies reaffirmed the importance of privacy and economics to NIPF owners. While some refrained from pro- gram participation due to their aversion to government in- volvement, others still participated in Commercial Forest for the tax incentive. While mistrust may lead some to seek other sources of advice or renounce government programs, it may not be the most influential factor in NIPF decision making behind economic and aesthetic priorities (Fischer et al., 2010). Inherent bias in our sampling methodology must be kept in mind when generalizing these results. One such bias is in phone interviewing. Our sample was limited to not only those owners with a telephone (Babbie, 2010), but those with a phone num- ber listed in the local printed and online directories. Cellular telephones are far less likely to be listed, but are far more common as primary phone numbers among those 30 years old and younger (US Census, 2009, Blumberg & Luke, 2010). The average age of the interviewees in our sample was 56.7; there were only two interviewees under the age of forty, and none under age thirty. Although owners under 30 are quite rare among NIPF owners in this area, their absence from our study may be impacted by their predominant use of cellular phones over landlines. We were also not able to contact some land- owners who lived out of state, were not listed online, and were not enrolled in Commercial Forests (which lists contact infor- mation for all owners). These omissions could bias our results since newer classes of NIPF owners tend to live further away from their NIPF property, and are less likely to enroll immedi- ately in voluntary programs (Jones et al., 1995). Finally, our use of coded interviews did not allow us to conduct rigorous statistical analyses of information flow among categories of owners, give our small sample size. While our methodology allowed us to gain details that we were unlikely to receive from a quantitative survey (Bliss & Martin, 1989), these details must be appreciated qualitatively. Conclusion The potential implications of this research on Michigan’s forested landscape depend on the actions taken by policy mak- ers and implementers to incorporate these and similar findings into their practices. NIPF owners influence their neighbors’ management and are influenced by their neighbors both directly and indirectly. As evidenced by the growing trend of peer- to-peer forest owner education programs and research, man- agement information can and does flow among owners across privately-owned landscapes (Reed, 2001; Fischer et al., 2010; Knoot & Rickenbach, 2011). While we did not collect informa- tion on the differential influence of opinion leaders in our sam- ple, some of our interviews suggested that experienced indi- viduals such as foresters may be more likely to be sought out for information. If information and advice about land manage- ment and programs were targeted to a few landowners, such as local foresters or opinion leaders in a community, the efficiency of information efforts might be increased. Not only mi ght more owners receive the information, but they may give it significant weight in their future decision-making. Increasing participation rates in these landowner assistance programs through more efficient information campaigns may not only help reduce for- est fragmentation (benefiting wildlife and ecosystem services), but create more cohesive NIPF owner communities. The most pote ntially influent ial result from thi s research was the importance of government mistrust and its impact on man- agement and programmatic information. As information about management travels through NIPF owner communities, so too can negative impressions or false information about govern- ment advice and programs. Forest owners are influenced by each other, both through direct communication and perceived management results, and therefore it is essential for successful program administration to improve the image of government agencies and programs within the private forest owner commu- nity. The most trusted sources of information among our inter- viewees were local private foresters, who were also NIPF own- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 155  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER ers and commonly community opinion leaders. Reaching out to these individuals could improve enrollment in programs and acceptance of advice from government organizations. The information dynamics and management goals we found in Michigan are broadly consistent with what has been ob- served in other countries with high proportions of NIPF owners, particularly in Europe. While information from professional foresters was highly regarded among NIPF owners in Germany, neighbors were viewed as an additional source of information for about half of those surveyed (Bieling, 2004). In Finland, a forest owner’s preferences for the source, mode or tone of the information communication can vary depending upon owner characteristics (such as age) or the relationship with the infor- mation source (Hujala & Tikkanen, 2008; Hujala et al., 2009). Owners in Sweden were less likely to trust government agen- cies if the agency’s goal was to educate forest owners about the preservation of biologically diverse forests on their property, and the owners did not value that goal (Götmark, 2009). Many of the points highlighted in our interviews, such as the differen- tial trust of information based on its source, and the influence of intangible values such as nature-based recreation and biodiver- sity conservation on management decisions, have been found among NIPF owners in many other countries (e.g., Tikkanen et al., 2006). Applying innovative techniques such as cognitive mapping and social network analysis at the scale of NIPF communities may increase our understanding of how to com- municate information regarding management practices and programs to these dynamic and complex communities, and how their collective decision-making might change our forested landscapes (Tikkanen et al., 2006; Fischer et al., 2010; Knoot & Rickenbach, 2011). Acknowledgements We would like to thank Brett J. Butler of the U.S.D.A. Forest Service for supplying us with NWOS data specific to the west- ern Upper Peninsula counties in Michigan. Jennifer Daryl Slack, Carol MacLennan, and Kathleen Halvorsen provided invaluable comments on JRS’s MS thesis from which this work was taken. A portion of this work was funded by a McIntire-Stennis grant from the US Department of Agriculture—Forest Service. REFERENCES Babbie, E. R. (2010). The practice of social research (12th ed.). Bel- mont, CA: Wadsworth. Best, C., & Wayburn, L. (2001). America’s private forests: Status and stewardship. Washing ton, DC: Island Press. Bieling, C. (2004). Non-industrial private-forest owners: Possibilities for increasing adoption of close-to-nature forest management. Euro- pean Journal of Forest Research, 123, 293-303. doi:10.1007/s10342-004-0042-6 Bliss, J. C., & Martin, A. J. (1989). Identifying NIPF management mo- tivations with qualitative methods. Forest Science, 35, 601-622. Blumberg, S., & Luke, J. (2010). Wireless substitution: Early release of estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, July-December 2009. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Brook, A., Zint, M., & DeYoung, R. (2003). Landowners’ responses to an Endangered Species Act listing and implications for encouraging conservation. Conservation Biology, 17, 1638-1649. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2003.00258.x Butler, B. J., Leatherberry, E. C., & Williams, M. S. (2005). Design, implementation, and analysis methods for the National Woodland Owner Survey. Amherst, MA: US Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Northern Research Station GT. Butler, B. (2008). Family forest owners of the United States, 2006. Amherst, MA: US Dep artment of Agriculture Forest Service, North- ern Research Station GT. Butler, B., & Ma, Z. (2011). Family forest owner trends in the Northern United States. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry, 28, 13-18. Cialdini, R. B., Trost, M. R., Gilbe rt, D. T., Fiske, S. T. , & Lindzey, G. (2008). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. Handbook of Social Psychology, 2, 151-192. Creighton, J. H., Baumgartner, D. M., & Blatner, K. A. (2002). Eco- system management and nondindustrial private forest landowners in Washington State, USA. Small-Scale Forest Economics, Manage- ment and Policy, 1, 55-69. DeWalt, K. M., & DeWalt, B. R. (2002). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. Erickson, D. L., Ryan, R. L., & De Young, R. (2002). Woodlots in the rural landscape: Landowner motivations and management attitudes in a Michigan (USA) case study. Landscape and Urban Planning, 58, 101-112. doi:10.1016/S0169-2046(01)00213-4 Finley, A. O., Kittredge Jr., D. B., Stevens, T. H., Schweik, C. M., & Dennis, D. C. (2006). Interest in cross-boundary cooperation: Identi- fication of distinct types of private forest owners. Forest Science, 52, 10-22. Fischer, A. P., Bliss, J., Ingemarson, F., Lidestav, G., & Lönnstedt, L. (2010). From the small woodland problem to ecosocial systems: the evolution of social research on small-scale forestry in Sweden and the USA. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 25, 390-398. doi:10.1080/02827581.2010.498386 Fortney, J., Arano, K. G., & Jacobson, M. (2011). An Evaluation of West Virginia’s Managed Timberland Tax Incentive Program. Forest Policy and Economics, 13, 69-78. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2010.08.002 Froese, R., Hyslop, M., Miller, C., Garmon, B., McDiarmid Jr., H., Shaw, A., Leefers, L., Lorenzo, M., Brown, S., & Shy, M. (2007). Large-tract Forestland Ownership Change: Land Use, Conservation, and Prosperity in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Ann Arbor, MI: Na- tional Wildlife Federation. Gan, J., Kolison Jr., S. H., & Tackie, N. O, (2003). African-American Forestland Owners in Alabama’s Black Belt. Journal of Forestry, 101, 38-43. Gootee, R. S., Blatner, K. A., Baumgartner, D. M., Carroll, M. S., & Weber, E. P. (2010). Choosing what to believe about forests: Differ- ences between professional and non-professional evaluative criteria. Small-scale Forestry, 9, 137-152. doi:10.1007/s11842-010-9113-3 Götmark, F. (2009). Conflicts in conservation: Woodland key habitats, authorities and private forest owners in Sweden. Scandinavian Jour- nal of Forest Research, 24, 504-514. doi:10.1080/02827580903363545 Greene, J. L., Straka, T. J., & Dee, R. J. (2004). Nonindustrial private forest owner use of federal income tax provisions. Forest Products Journal, 54, 59-66. Greene, J., Daniels, S., Jacobson, M., Kilgore, M., & Straka, T. (2005). Existing and potential incentives for practicing sustainable forestry on non-industrial private forest lands. Final Report to the National Commission on Science for Sustainable Forestry, NCSSF Research Project C2, 31 October 2 0 0 5. URL (last checked 5 July 2011). http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/econ/data/forestincentives/ncssf-c2-final- report.pdf Gustafson, E. J., & Loehle, C. (2008). How will the changing industrial forest landscape affect forest sustainability? Journal of Forestry, 106, 380-387. Haymond, J. L. (1988). NIPF opinion leaders: What do they want? Journal of Forestry, 86, 30-31, 34-35 Hujala, T., & Tikkanen, J. (2008). Boosters of and barriers to smooth communication in family forest owners’ decision manking. Scandi- navian Journal of Forest Research, 23, 466-477. doi:10.1080/02827580802334209 Hujala, T., Tikkanen, J., Hänninen, H., & Virkkula, O. (2009). Family forest owners’ perception of decision support. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 24, 448-460. doi:10.1080/02827580903140679 Irland, L. C. (1994). Getting from here to there: Implementing ecosys- tem management on the ground. Journal of Forestry, 92, 12-17. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 156  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 157 Jacobson, M. G. (2002). Ecosystem management in the southeast United States: Interest of forest landowners in joint management across ownerships. Small-scale Forest Economics, Management and Policy, 1, 71-92. Jones, S. B., Luloff, A. E., & Finley, J. C. (1995). Another look at NIPFs: facing our myths. Journal of Forestry, 93, 41-44. Kilgore, M. A., Green e, J. L., Jaco bso n, M. G., St raka, T. J., & Dan iels, S. E. (2007). The Influence of Financial Incentive Programs in Pro- moting Sustainable Forestry on the Nation’s Family Forests. Journal of Forestry, 105, 184-191. Knoot, T. G., & Rickenbach, M. (2011). Best management practices and timber harvesting: The role of social networks in shaping land- owner decisions. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 26, 171- 182. doi:10.1080/02827581.2010.545827 Leatherberry, E. C., Kingsley, N. P., & Birch, T. W. (1998). Private timberland owners of Michigan, 1994. St. Paul, MN: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, NC Resource Bull. Lieberherr, E. (2011). Acceptability of the Deschutes Groundwater Mitigation Program. Ecology Law Currents, 38, 25-35. Lönnstedt, L. (1997). Non-industrial private forest owners’ decision process: A qualitative study about goals time perspective, opportuni- ties and alternatives. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 12, 302-310. doi:10.1080/02827589709355414 Ma, Z., Kittredge, D. B., & Catanzaro, P. (2012). Challenging the tradi- tional forestry extension model: Insights from the Woods Forum Program in Massachusetts. Small-scale Forestry, 11, 87-100. doi:10.1007/s11842-011-9170-2 Mayer, A. L., & Tikka, P. M. (2006). Biodiversity conservation incen- tive programs for privately owned forests. Environmental Science and Policy, 9, 614-625. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2006.07.004 Mehmood, S., & Zhang, D. (2001). Forest parcelization in the United States: A study of contributing factors. Journal of Forestry, 99, 30- 34. Michigan Department of Natural Resources (2011). Commercial Forest (CF) Information and Forms. URL (last checked 16 February 2011) http://www.michigan.gov/dnr/0,1607,7-153-30301_30505_34240-34 01600.html Nagubadi, V., McNamara, K. T., Hoover, W. L., & Mills Jr., W. L. (1996). Program participation behavior of non-industrial forest land- owners: A probit analysis. Journal of Agricultural and Applied Eco- nomics, 28, 323-336. Nelson, C. M. (2001). Economic implications of land use patterns for natural resource recreation and tourism. Lansing, MI: Michigan Land Resource Project, Public Sector Consultants. Newman, D. H., Aronow, M. E., Harris Jr., T. G., & Macheski, G. (1996). Changes in timberland ownership characteristics in Georgia. In M. J. Baughman (Ed.), Symposium on nonindustrial private for- ests: Learning from the past, prospects for the future. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota. Patton, M. Q. (1992). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. Potter-Witter, K. (2005). A cross-sectional analysis of Michigan non-industrial private forest landowners. Northern Journal of Ap- plied Forestry, 22, 132-138. Reed, A. S. (2001). Extension in Oregon—Educational leadership for sustainability. Journal of F orestry, 99, 18-21. Rickenbach, M., & Reed, A. (2002). Cross-boundary cooperation in a watershed context: The sentiments of private forest landowners. En- vironmental Management, 30, 584-594. doi:10.1007/s00267-002-2688-5 Rickenbach, M., Zeuli, K., & Sturgess-Cleek, E. (2005). Despite failure: The emergence of “new” forest owners in private forest policy in Wisconsin, USA. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 20, 503- 513. doi:10.1080/02827580500434806 Rogers, E., & Shoemaker, F. (1971). Communication of innovations: A cross-cultural approach. New York, NY: The Free Press. Rossi, F. J., Carter, D. R., Alavalapati, J. R. R., & Nowak, J. T. (2010). Forest landowner participation in State-Administered Southern Pine Beetle Prevention Cost-Share Programs. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry, 34, 110-117. Shandas, V. (2007). An empirical study of streamside landowners’ interest in riparian conservation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 73, 173-184. doi:10.1080/01944360708976151 Tikkanen, J., Isokääntä, T., Pykäläinen, J., & Leskinen, P. (2006). Ap- plying cognitive mapping approach to explore the objective-structure of forest owners in a Northern Finnish case area. Forest Policy and Economics, 9, 139-152. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2005.04.001 US Census Bureau (2009). Homes with cell phones nearly double in first half of decade. URL ( la s t checked 24 March 2 01 2 ). http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/income_wealth/c b09-174.html Vokoun, M., Amacher, G. S., Sullivan, J., & Wear, D . (2010). Examin- ing incentives for adjacent non-industrial private forest landowners to cooperate. Forest Policy and Economics, 12, 104-110. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2009.08.008 West, P. C., Fly, J. M., Blahna, D. J., & Carpenter, E. M. (1988). The communication and diffusion of NIPF management strategies. Nor- thern Journal of Applied Forestry, 5, 265-270. Zhang, Y., Zhang, D., & Schelhas, J. (2005). Small-scale non-industrial private forest ownership in the United States: rationale and implica- tions for forest management. Silva Fennica, 39, 443-454.  J. R. SCHUBERT, A. L. MAYER Appendix: Interview Questions 1) How long have you owned your property? Do you own more than one forested property? 2) How did you acquire your property? [Did you buy or in- herit it?] Why did you purchase a forested property? 3) Do you live on your forest property for most of the year? [Where do you live if not? How far is your home from your forest property?] 4) Can you please describe your property? [how many acres, how much forest, what kind of forest?] 5) Some people work with their land to achieve certain goals that they manage for [such as timber improvement, wildlife habitat]. What are your goals, if any? Do you actively work with or manage your land? What do you do and why? Why or why not? 6) Do you have a written management plan [a plan stating what you want to do with your land and how you will achieve it]? Why or why not? Can you describe your plan? 7) Is your forest enrolled in any programs [for example CFA, conservation easements]? If so, which program? Why did you choose to enroll? What do you see as the benefits or drawbacks to these programs? 8) Do you know how your neighbors manage their land? Do your neighbors manage their forest similar to the way you do? If not, what is different about what they do to their land? 9) How many neighboring landowners do you know? 10) Do you talk to your neighbors about what you do with your land? If so, what do you talk about? If not, why not? 11) Have you ever specifically done or avoided something because of your neighbor’s success or failure with that method? If so, what was it? Why did you do it? 12) Where do you get advice about managing your land? [for example forester, DNR, other owners, internet] Why did you choose that source? What kind of advice have you received? 13) Are there any neighbors that you think would be inter- ested in being interviewed or that could give me valuable in- formation? If so, could you please tell me their name and pos- sible a way to contact them? 14) Could you please tell me your age and highest level of education? Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 158

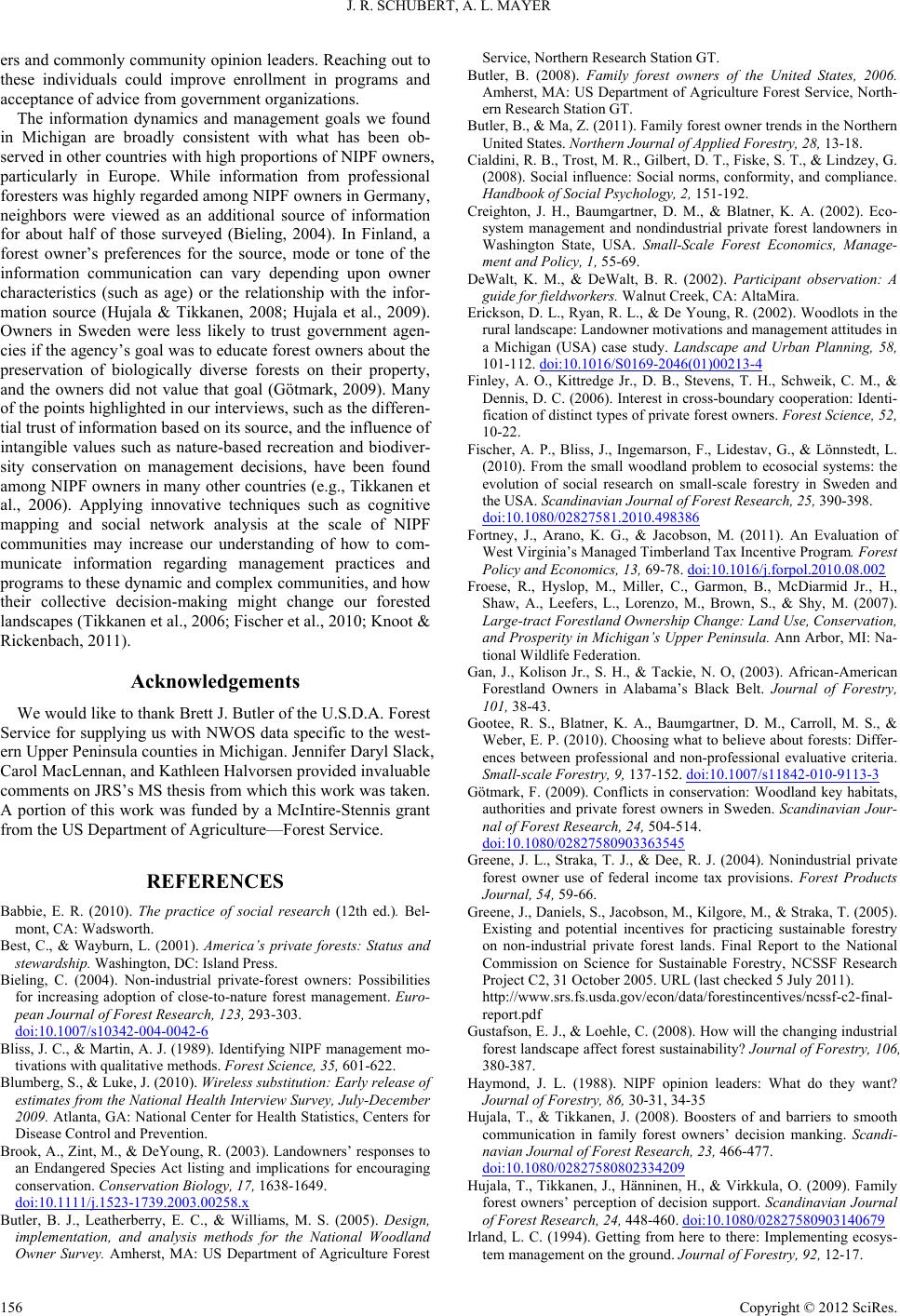

|