Paper Menu >>

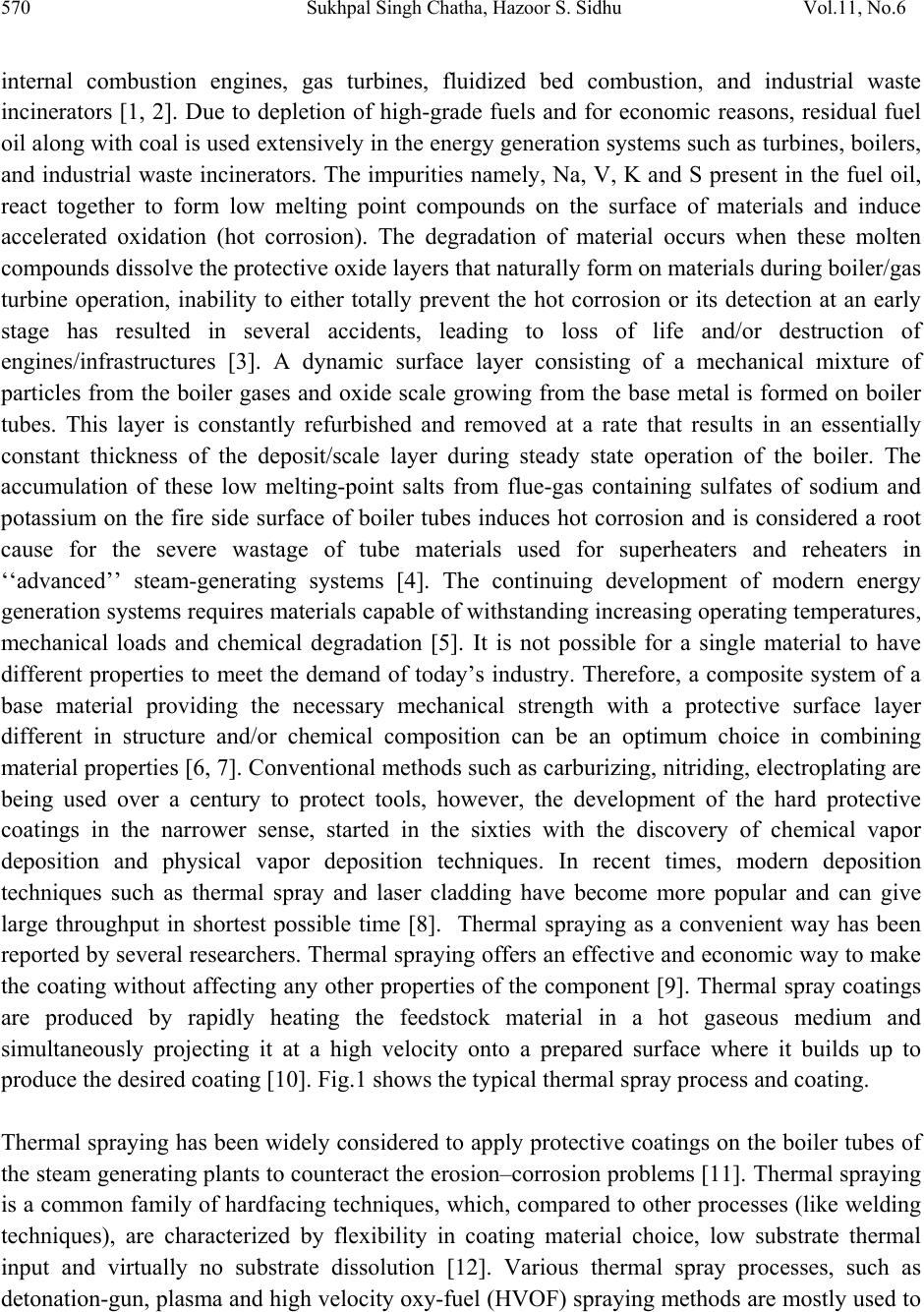

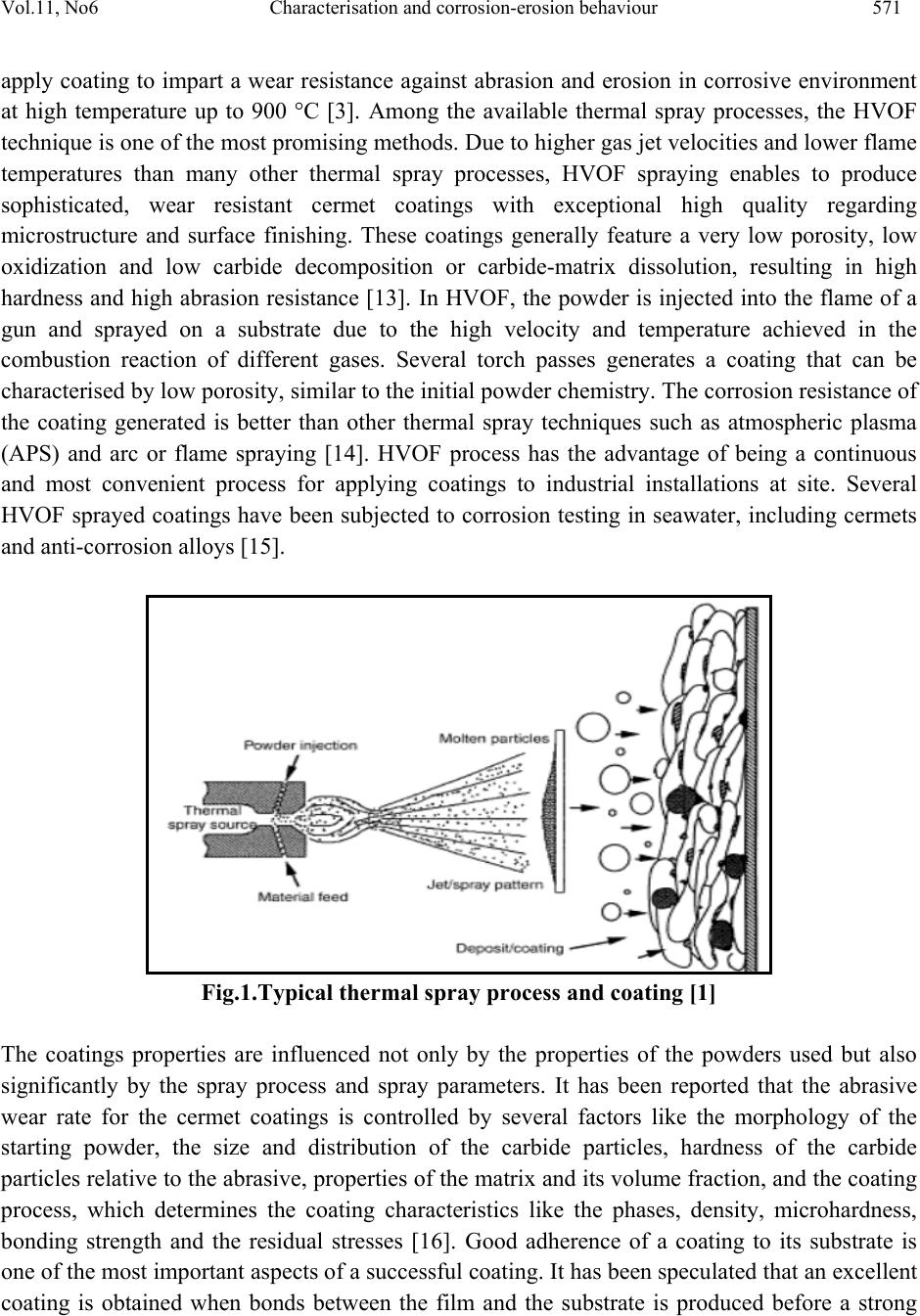

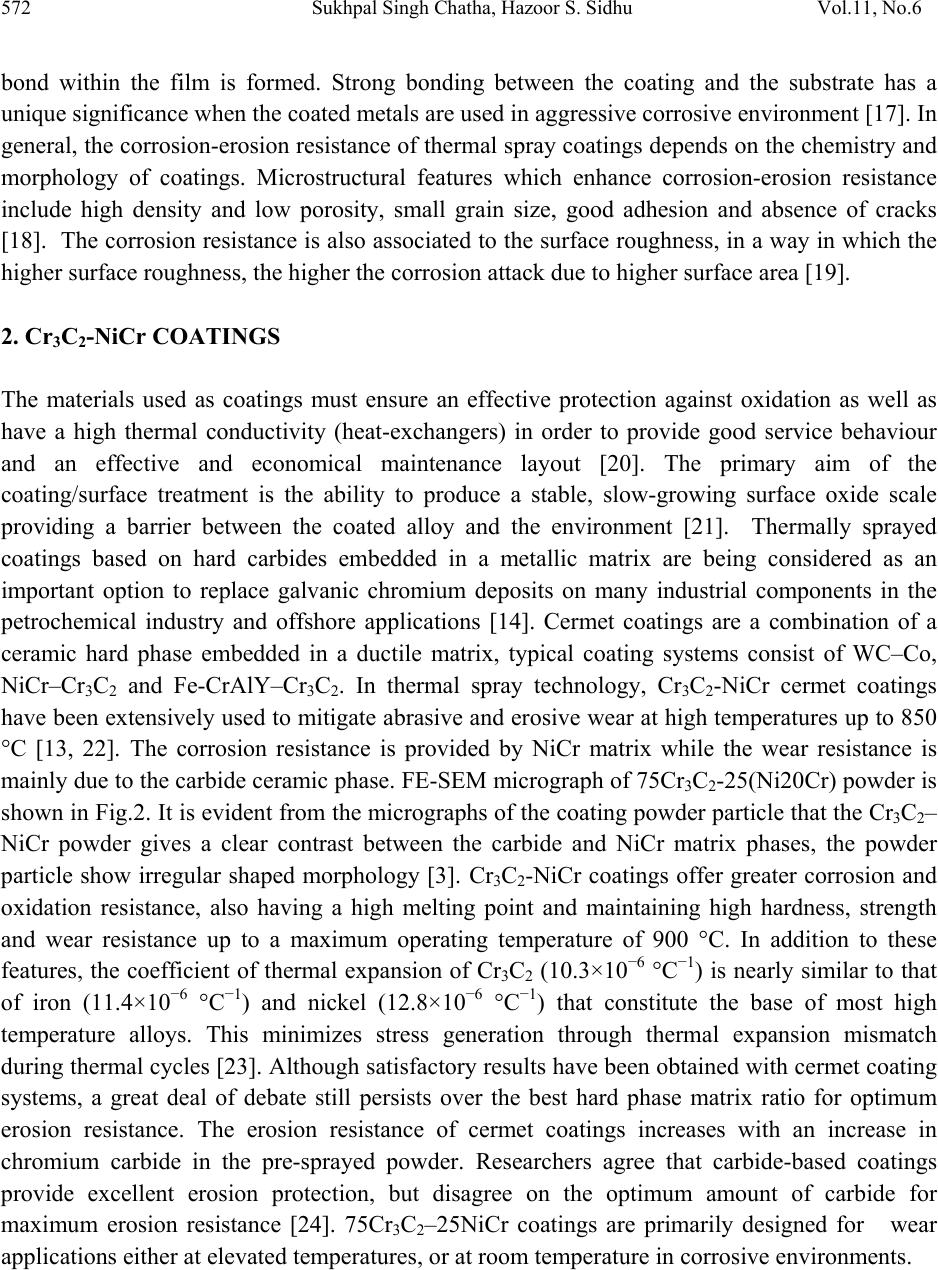

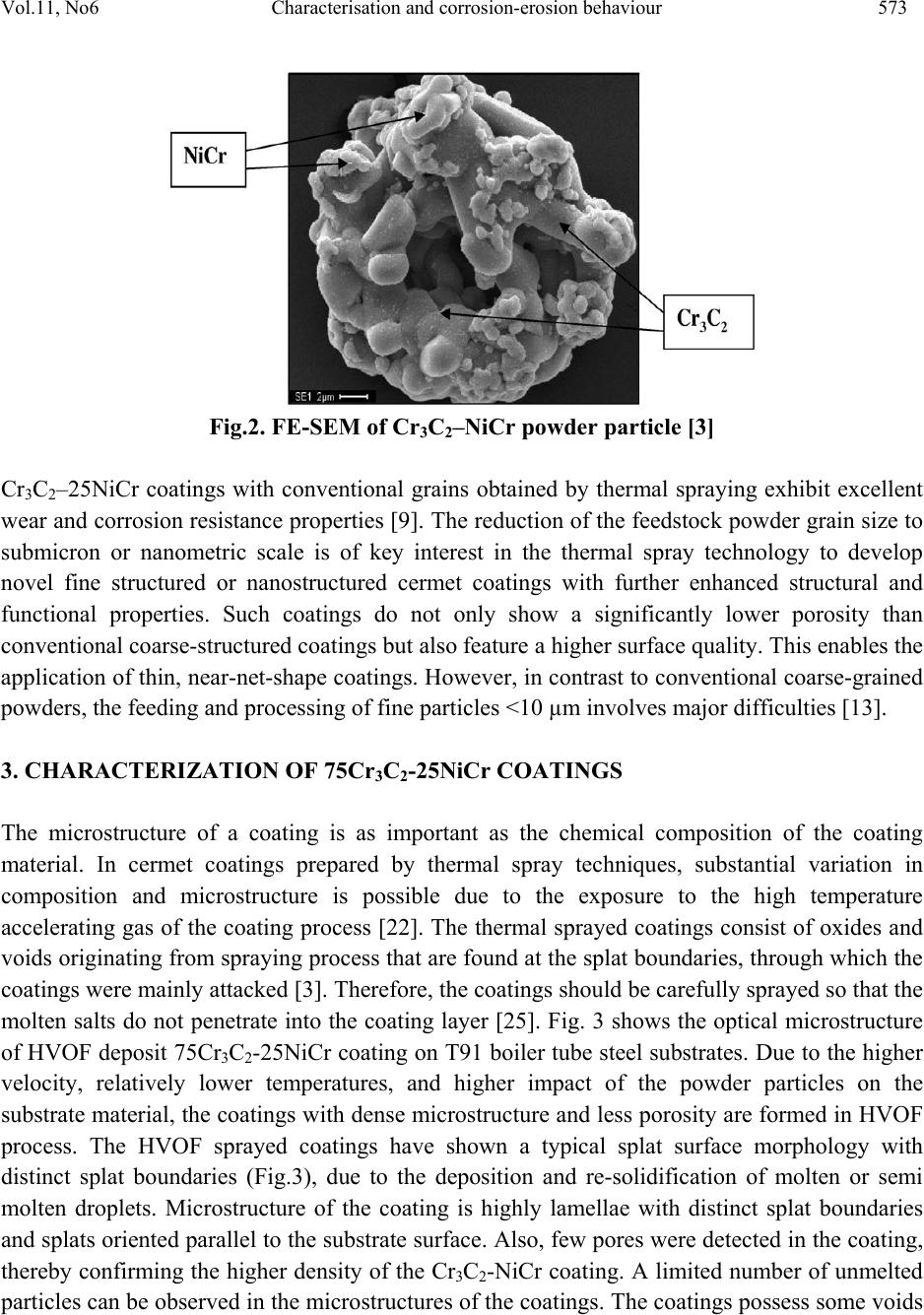

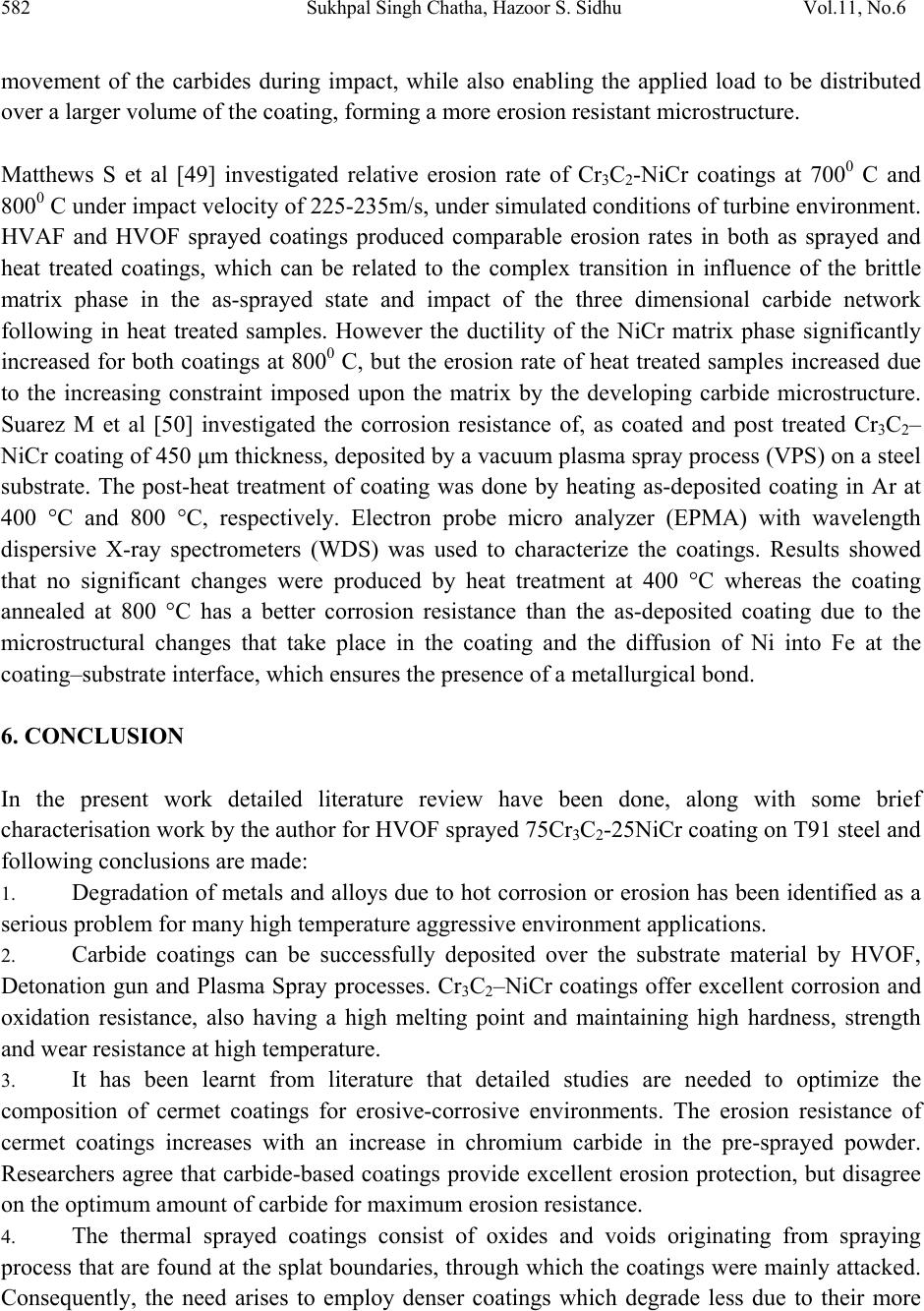

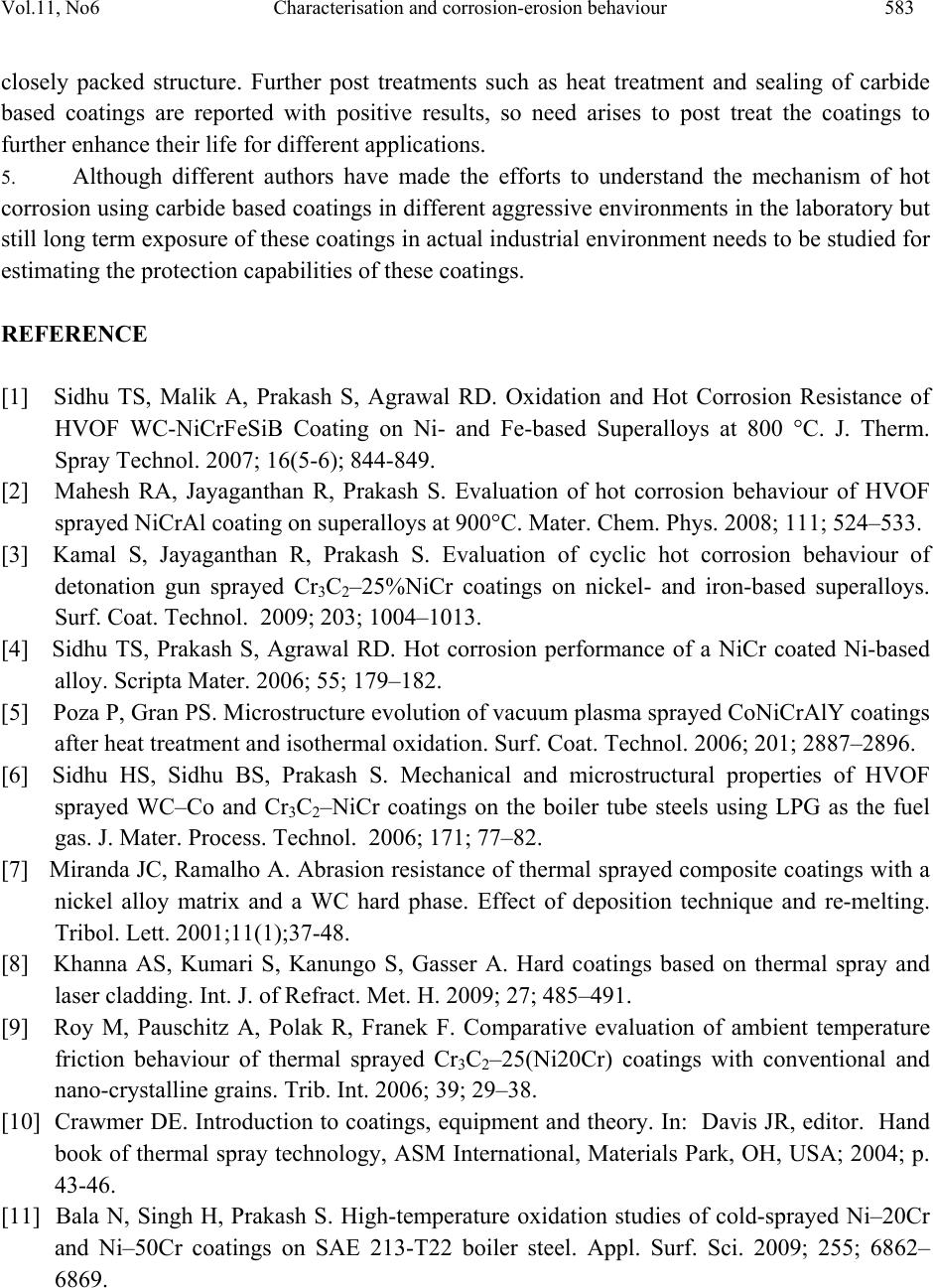

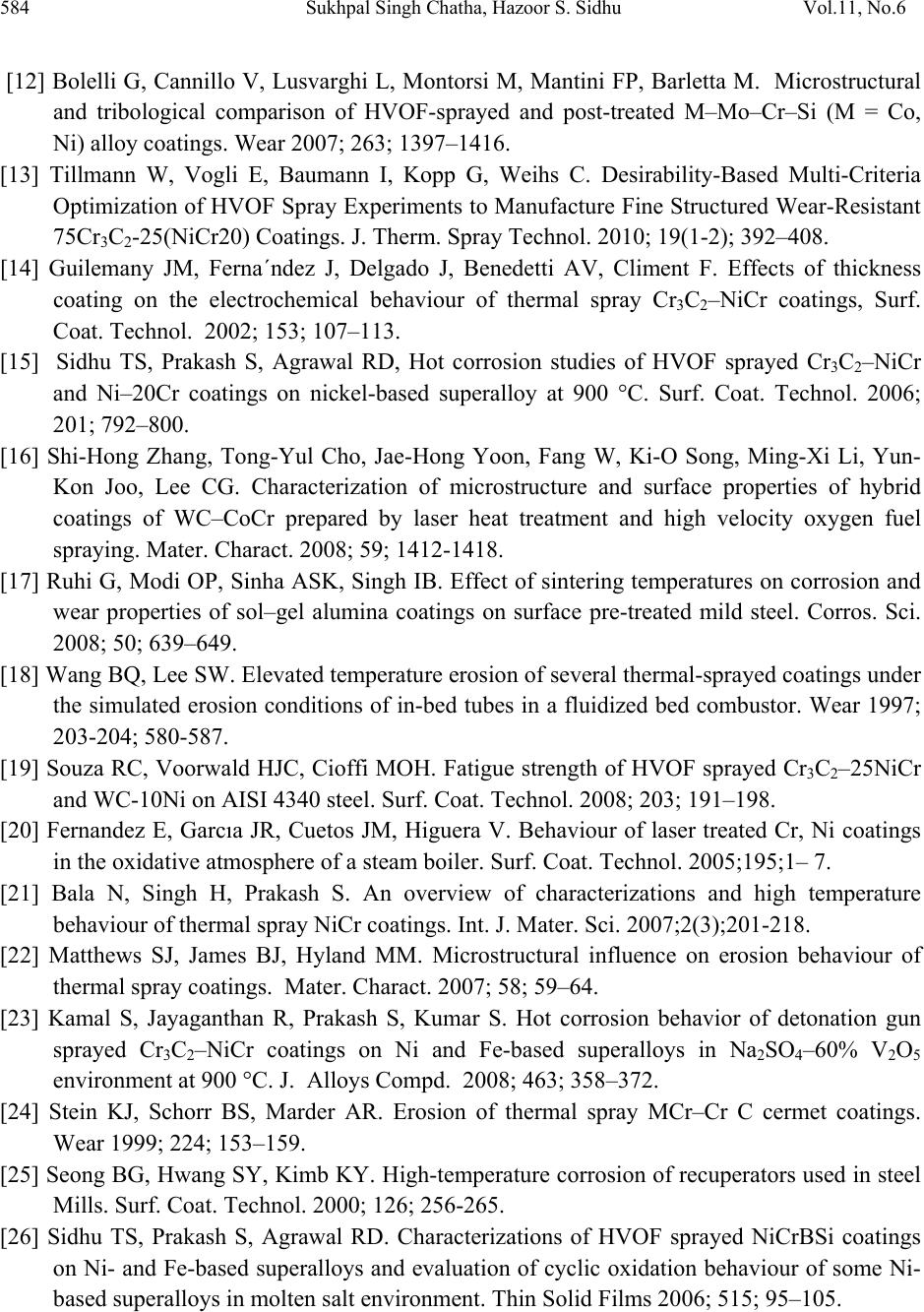

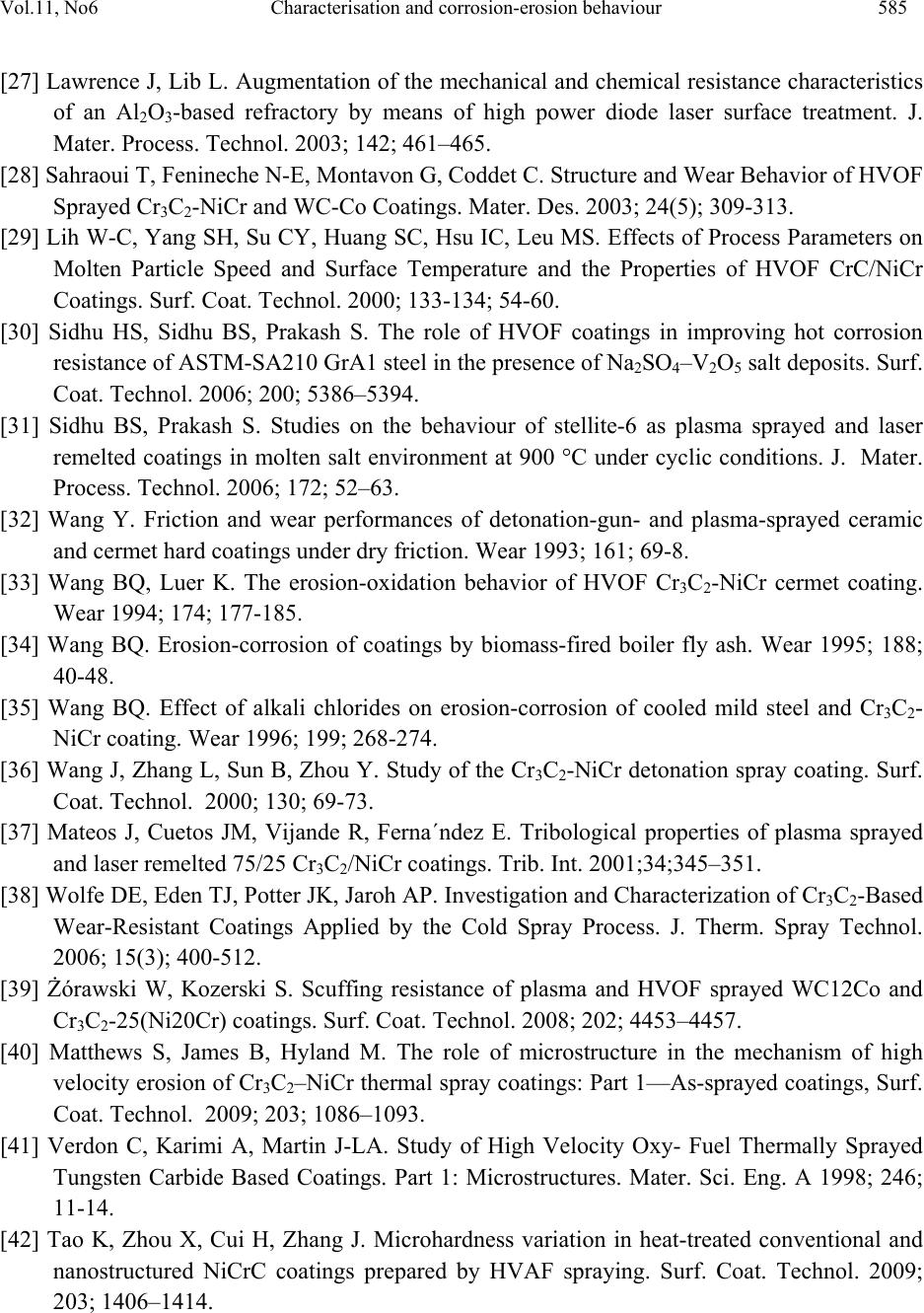

Journal Menu >>

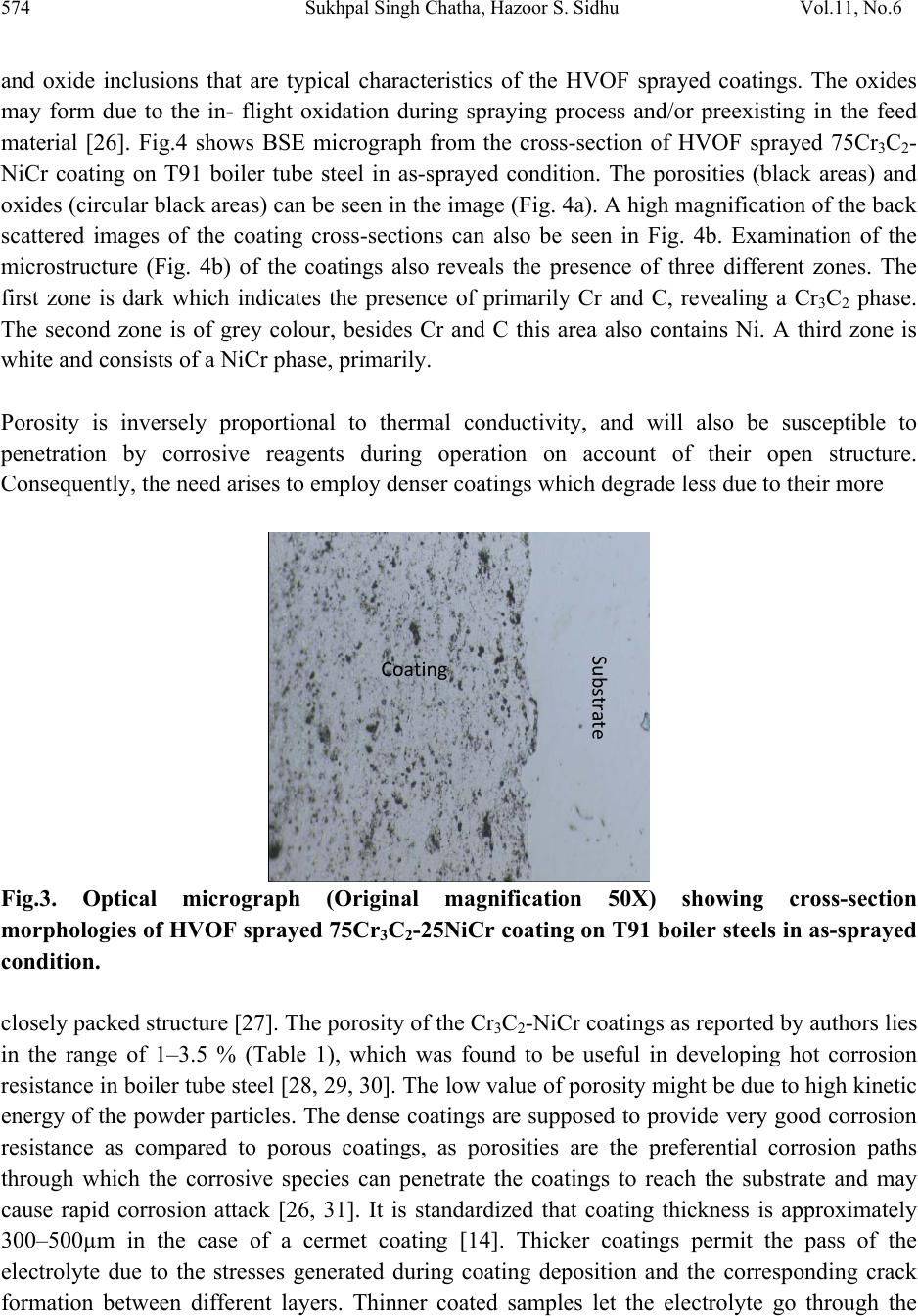

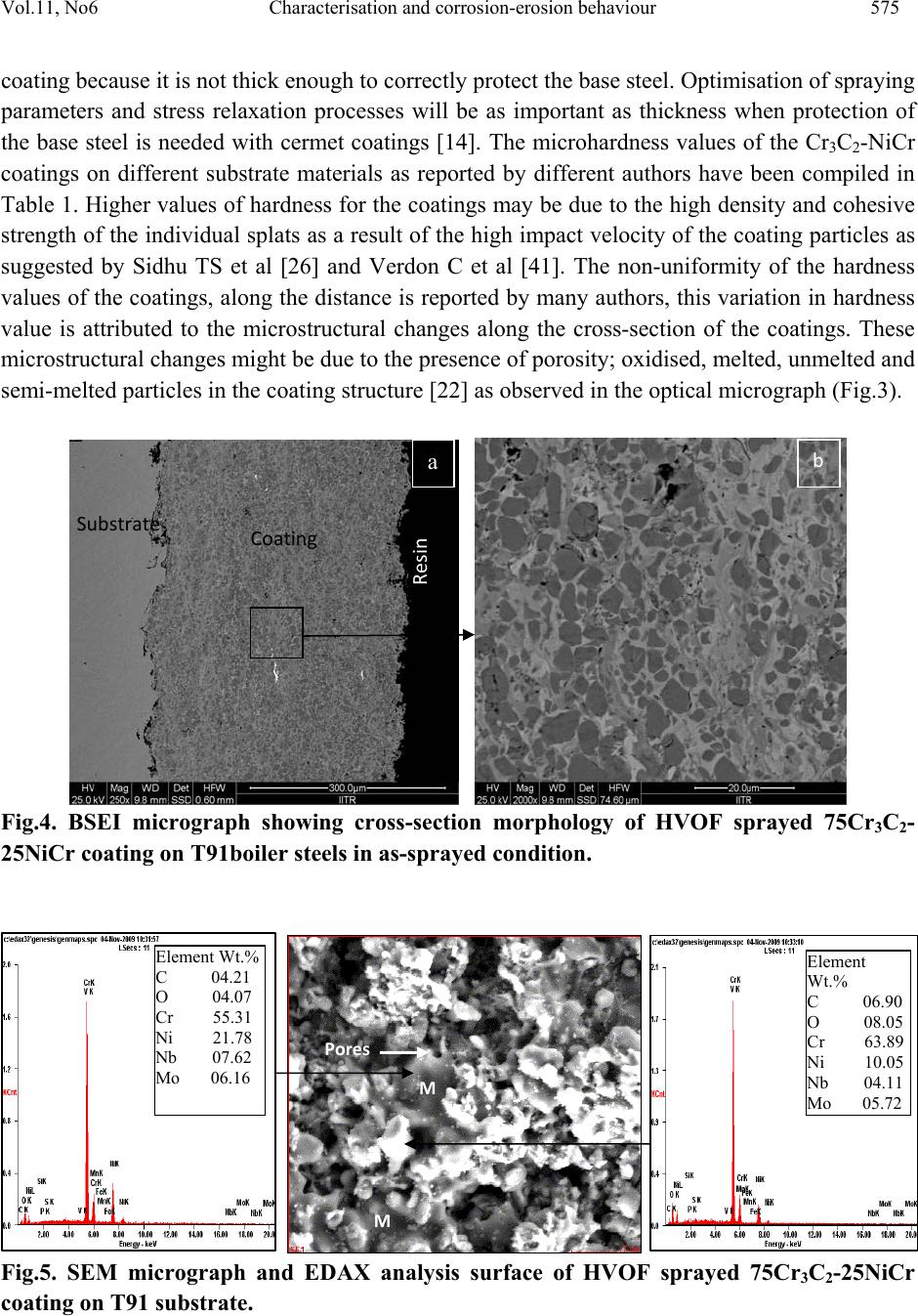

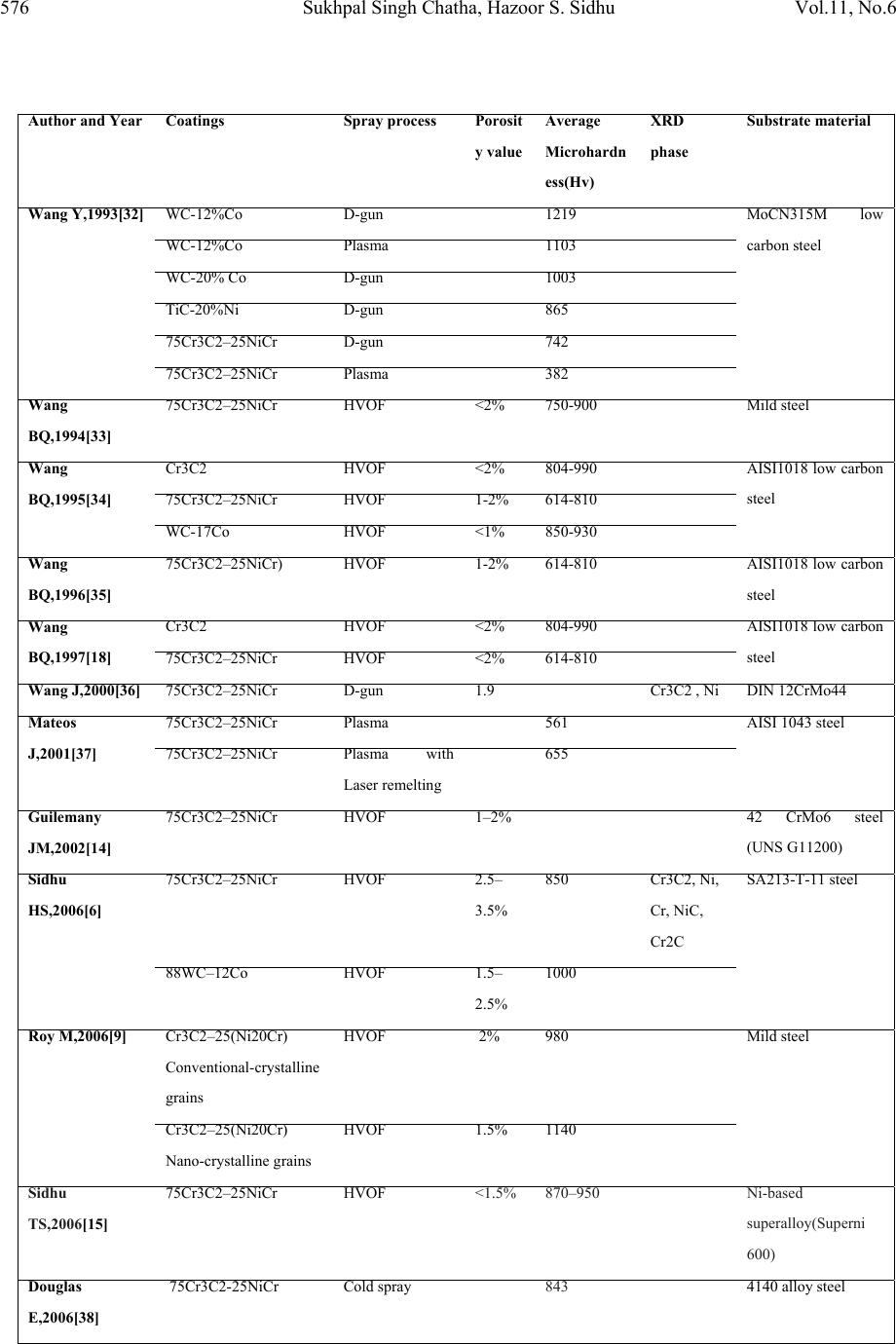

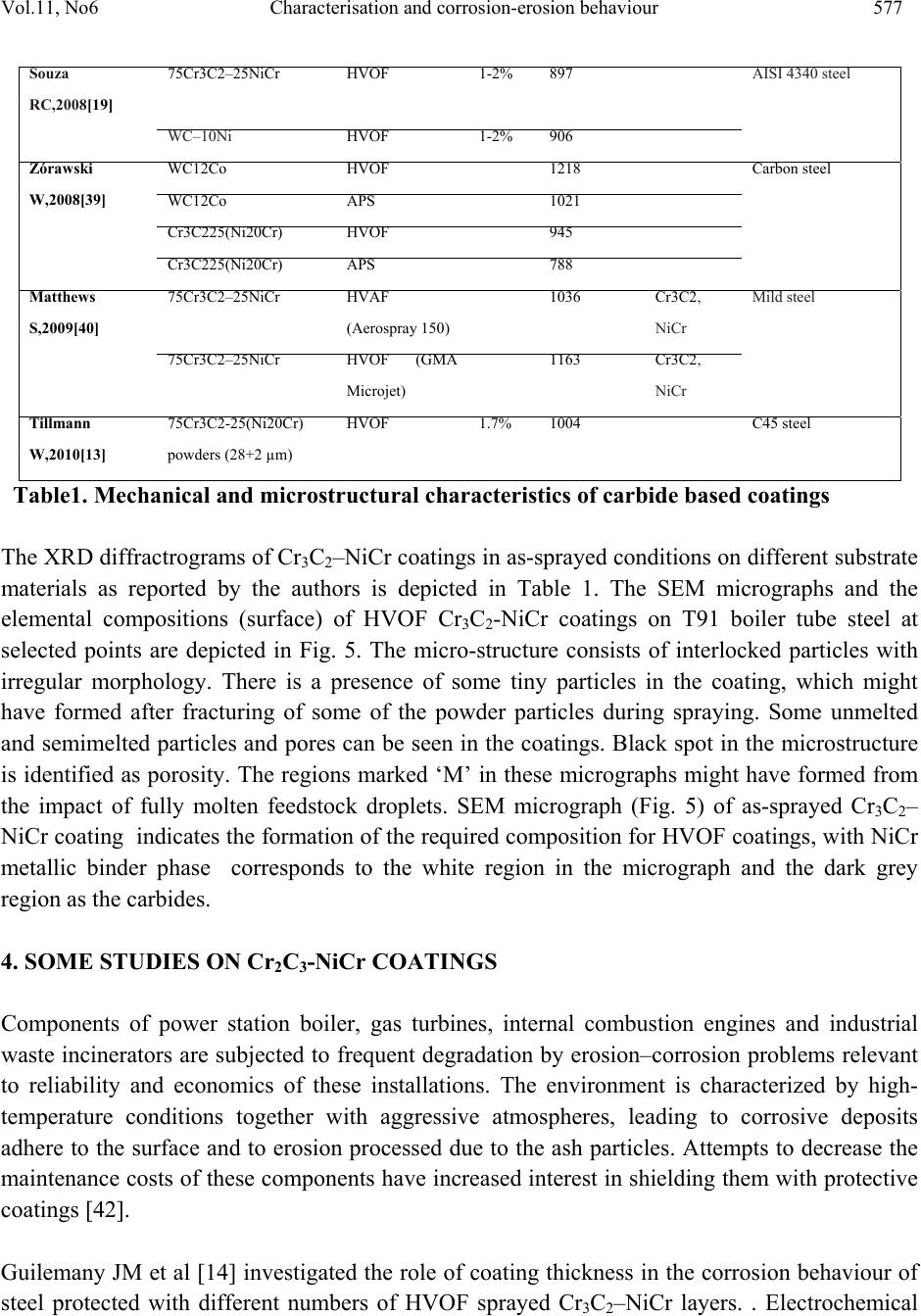

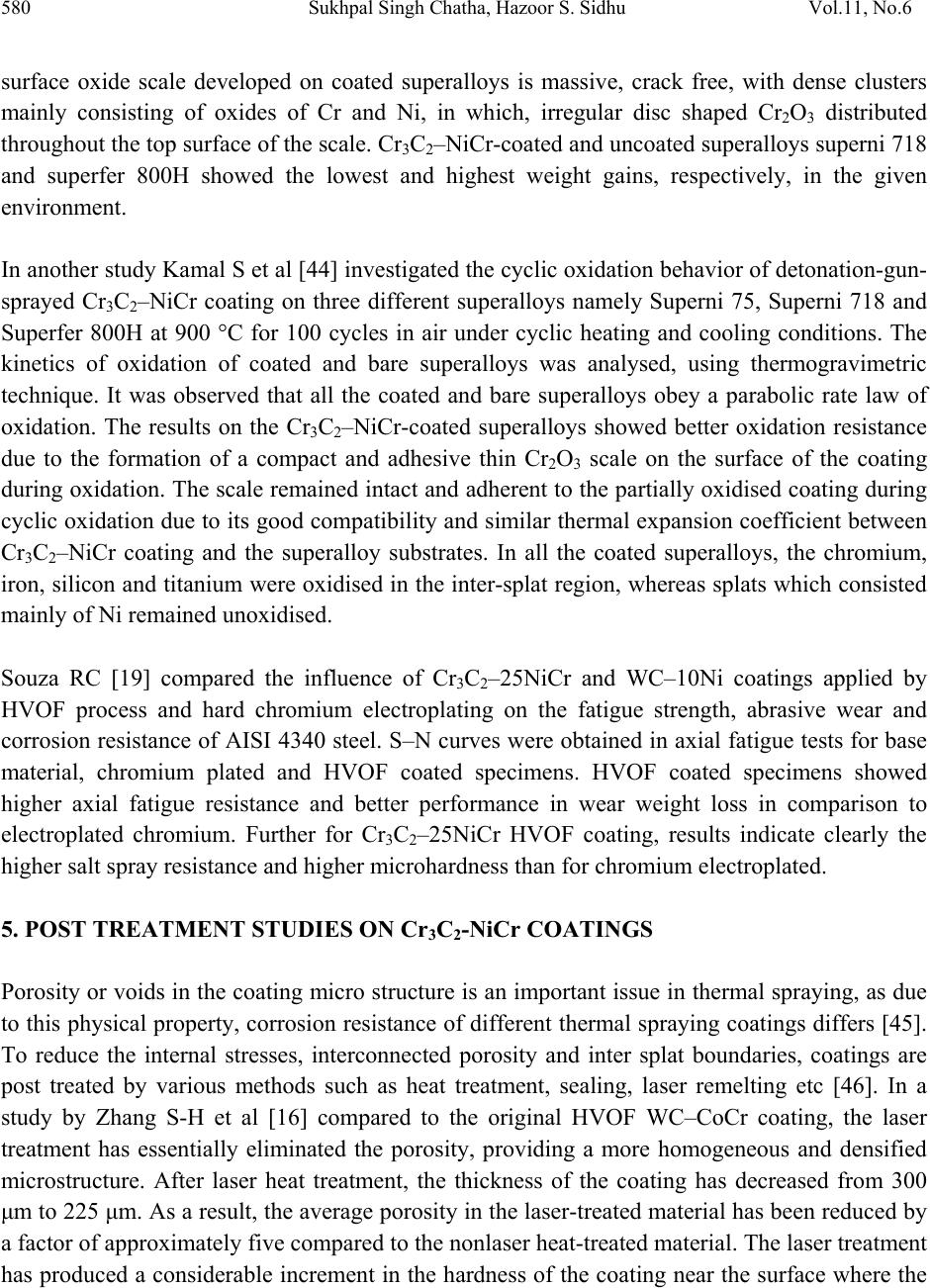

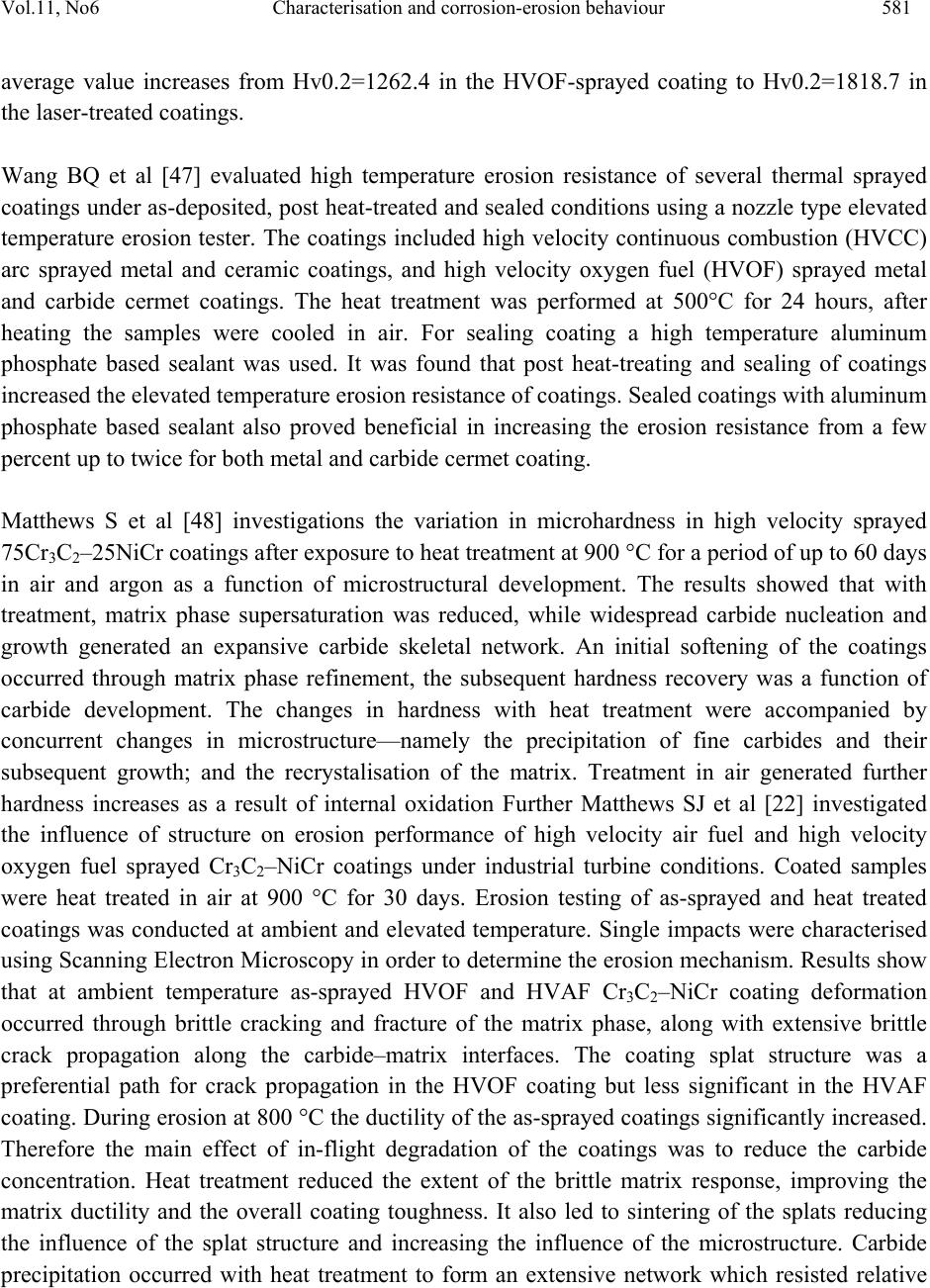

Journal of Minerals & Materials Characterization & Engineering, Vol. 11, No.6, pp.569-586, 2012 jmmce.org Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 569 Characterisation and Corrosion-Erosion Behaviour of Carbide based Thermal Spray Coatings Sukhpal Singh Chatha a,*, Hazoor S. Sidhu a, Buta S. Sidhu b a Yadavindra College of Engineering, Punjabi University Guru Kashi Campus, Talwandi Sabo, Bathinda, Punjab-151302, India b Punjab Technical University, Jalandhar, Punjab-144601, India *Corresponding Author: Sukhpal_chatha@yahoo.com ABSTRACT Thermal spraying has emerged as a suitable and effective surface engineering technology and is widely used to apply wear, erosion and corrosion protective coatings for various kinds of industrial applications. Cr3C2-based coatings have been applied to a wide range of industrial components. Cr3C2–NiCr coatings offer greater corrosion and oxidation resistance, also having a high melting point and maintaining high hardness, strength and wear resistance up to a maximum operating temperature of 900 °C. The corrosion resistance is provided by NiCr matrix while the wear resistance is mainly due to the carbide ceramic phase. This paper reviews the performance, developments and applications of Cr3C2–NiCr thermal spray coatings for corrosion/erosion-corrosion under different types of environments and outlines the characterization of Cr3C2–NiCr coatings with respect to their microstructure and mechanical properties, together with some brief characterisation work by the author for HVOF sprayed 75Cr3C2-25NiCr coating on T91 boiler steel. Keywords: Thermal spray, Microstructure, Mechanical properties, Corrosion-erosion, Cr3C2-NiCr 1. INTRODUCTION Degradation of metals and alloys due to hot corrosion or erosion has been identified as a serious problem for many high temperature aggressive environment applications, such as boilers,  570 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 internal combustion engines, gas turbines, fluidized bed combustion, and industrial waste incinerators [1, 2]. Due to depletion of high-grade fuels and for economic reasons, residual fuel oil along with coal is used extensively in the energy generation systems such as turbines, boilers, and industrial waste incinerators. The impurities namely, Na, V, K and S present in the fuel oil, react together to form low melting point compounds on the surface of materials and induce accelerated oxidation (hot corrosion). The degradation of material occurs when these molten compounds dissolve the protective oxide layers that naturally form on materials during boiler/gas turbine operation, inability to either totally prevent the hot corrosion or its detection at an early stage has resulted in several accidents, leading to loss of life and/or destruction of engines/infrastructures [3]. A dynamic surface layer consisting of a mechanical mixture of particles from the boiler gases and oxide scale growing from the base metal is formed on boiler tubes. This layer is constantly refurbished and removed at a rate that results in an essentially constant thickness of the deposit/scale layer during steady state operation of the boiler. The accumulation of these low melting-point salts from flue-gas containing sulfates of sodium and potassium on the fire side surface of boiler tubes induces hot corrosion and is considered a root cause for the severe wastage of tube materials used for superheaters and reheaters in ‘‘advanced’’ steam-generating systems [4]. The continuing development of modern energy generation systems requires materials capable of withstanding increasing operating temperatures, mechanical loads and chemical degradation [5]. It is not possible for a single material to have different properties to meet the demand of today’s industry. Therefore, a composite system of a base material providing the necessary mechanical strength with a protective surface layer different in structure and/or chemical composition can be an optimum choice in combining material properties [6, 7]. Conventional methods such as carburizing, nitriding, electroplating are being used over a century to protect tools, however, the development of the hard protective coatings in the narrower sense, started in the sixties with the discovery of chemical vapor deposition and physical vapor deposition techniques. In recent times, modern deposition techniques such as thermal spray and laser cladding have become more popular and can give large throughput in shortest possible time [8]. Thermal spraying as a convenient way has been reported by several researchers. Thermal spraying offers an effective and economic way to make the coating without affecting any other properties of the component [9]. Thermal spray coatings are produced by rapidly heating the feedstock material in a hot gaseous medium and simultaneously projecting it at a high velocity onto a prepared surface where it builds up to produce the desired coating [10]. Fig.1 shows the typical thermal spray process and coating. Thermal spraying has been widely considered to apply protective coatings on the boiler tubes of the steam generating plants to counteract the erosion–corrosion problems [11]. Thermal spraying is a common family of hardfacing techniques, which, compared to other processes (like welding techniques), are characterized by flexibility in coating material choice, low substrate thermal input and virtually no substrate dissolution [12]. Various thermal spray processes, such as detonation-gun, plasma and high velocity oxy-fuel (HVOF) spraying methods are mostly used to  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 571 apply coating to impart a wear resistance against abrasion and erosion in corrosive environment at high temperature up to 900 °C [3]. Among the available thermal spray processes, the HVOF technique is one of the most promising methods. Due to higher gas jet velocities and lower flame temperatures than many other thermal spray processes, HVOF spraying enables to produce sophisticated, wear resistant cermet coatings with exceptional high quality regarding microstructure and surface finishing. These coatings generally feature a very low porosity, low oxidization and low carbide decomposition or carbide-matrix dissolution, resulting in high hardness and high abrasion resistance [13]. In HVOF, the powder is injected into the flame of a gun and sprayed on a substrate due to the high velocity and temperature achieved in the combustion reaction of different gases. Several torch passes generates a coating that can be characterised by low porosity, similar to the initial powder chemistry. The corrosion resistance of the coating generated is better than other thermal spray techniques such as atmospheric plasma (APS) and arc or flame spraying [14]. HVOF process has the advantage of being a continuous and most convenient process for applying coatings to industrial installations at site. Several HVOF sprayed coatings have been subjected to corrosion testing in seawater, including cermets and anti-corrosion alloys [15]. Fig.1.Typical thermal spray process and coating [1] The coatings properties are influenced not only by the properties of the powders used but also significantly by the spray process and spray parameters. It has been reported that the abrasive wear rate for the cermet coatings is controlled by several factors like the morphology of the starting powder, the size and distribution of the carbide particles, hardness of the carbide particles relative to the abrasive, properties of the matrix and its volume fraction, and the coating process, which determines the coating characteristics like the phases, density, microhardness, bonding strength and the residual stresses [16]. Good adherence of a coating to its substrate is one of the most important aspects of a successful coating. It has been speculated that an excellent coating is obtained when bonds between the film and the substrate is produced before a strong  572 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 bond within the film is formed. Strong bonding between the coating and the substrate has a unique significance when the coated metals are used in aggressive corrosive environment [17]. In general, the corrosion-erosion resistance of thermal spray coatings depends on the chemistry and morphology of coatings. Microstructural features which enhance corrosion-erosion resistance include high density and low porosity, small grain size, good adhesion and absence of cracks [18]. The corrosion resistance is also associated to the surface roughness, in a way in which the higher surface roughness, the higher the corrosion attack due to higher surface area [19]. 2. Cr3C2-NiCr COATINGS The materials used as coatings must ensure an effective protection against oxidation as well as have a high thermal conductivity (heat-exchangers) in order to provide good service behaviour and an effective and economical maintenance layout [20]. The primary aim of the coating/surface treatment is the ability to produce a stable, slow-growing surface oxide scale providing a barrier between the coated alloy and the environment [21]. Thermally sprayed coatings based on hard carbides embedded in a metallic matrix are being considered as an important option to replace galvanic chromium deposits on many industrial components in the petrochemical industry and offshore applications [14]. Cermet coatings are a combination of a ceramic hard phase embedded in a ductile matrix, typical coating systems consist of WC–Co, NiCr–Cr3C2 and Fe-CrAlY–Cr3C2. In thermal spray technology, Cr3C2-NiCr cermet coatings have been extensively used to mitigate abrasive and erosive wear at high temperatures up to 850 °C [13, 22]. The corrosion resistance is provided by NiCr matrix while the wear resistance is mainly due to the carbide ceramic phase. FE-SEM micrograph of 75Cr3C2-25(Ni20Cr) powder is shown in Fig.2. It is evident from the micrographs of the coating powder particle that the Cr3C2– NiCr powder gives a clear contrast between the carbide and NiCr matrix phases, the powder particle show irregular shaped morphology [3]. Cr3C2-NiCr coatings offer greater corrosion and oxidation resistance, also having a high melting point and maintaining high hardness, strength and wear resistance up to a maximum operating temperature of 900 °C. In addition to these features, the coefficient of thermal expansion of Cr3C2 (10.3×10−6 °C−1) is nearly similar to that of iron (11.4×10−6 °C−1) and nickel (12.8×10−6 °C−1) that constitute the base of most high temperature alloys. This minimizes stress generation through thermal expansion mismatch during thermal cycles [23]. Although satisfactory results have been obtained with cermet coating systems, a great deal of debate still persists over the best hard phase matrix ratio for optimum erosion resistance. The erosion resistance of cermet coatings increases with an increase in chromium carbide in the pre-sprayed powder. Researchers agree that carbide-based coatings provide excellent erosion protection, but disagree on the optimum amount of carbide for maximum erosion resistance [24]. 75Cr3C2–25NiCr coatings are primarily designed for wear applications either at elevated temperatures, or at room temperature in corrosive environments.  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 573 Fig.2. FE-SEM of Cr3C2–NiCr powder particle [3] Cr3C2–25NiCr coatings with conventional grains obtained by thermal spraying exhibit excellent wear and corrosion resistance properties [9]. The reduction of the feedstock powder grain size to submicron or nanometric scale is of key interest in the thermal spray technology to develop novel fine structured or nanostructured cermet coatings with further enhanced structural and functional properties. Such coatings do not only show a significantly lower porosity than conventional coarse-structured coatings but also feature a higher surface quality. This enables the application of thin, near-net-shape coatings. However, in contrast to conventional coarse-grained powders, the feeding and processing of fine particles <10 µm involves major difficulties [13]. 3. CHARACTERIZATION OF 75Cr3C2-25NiCr COATINGS The microstructure of a coating is as important as the chemical composition of the coating material. In cermet coatings prepared by thermal spray techniques, substantial variation in composition and microstructure is possible due to the exposure to the high temperature accelerating gas of the coating process [22]. The thermal sprayed coatings consist of oxides and voids originating from spraying process that are found at the splat boundaries, through which the coatings were mainly attacked [3]. Therefore, the coatings should be carefully sprayed so that the molten salts do not penetrate into the coating layer [25]. Fig. 3 shows the optical microstructure of HVOF deposit 75Cr3C2-25NiCr coating on T91 boiler tube steel substrates. Due to the higher velocity, relatively lower temperatures, and higher impact of the powder particles on the substrate material, the coatings with dense microstructure and less porosity are formed in HVOF process. The HVOF sprayed coatings have shown a typical splat surface morphology with distinct splat boundaries (Fig.3), due to the deposition and re-solidification of molten or semi molten droplets. Microstructure of the coating is highly lamellae with distinct splat boundaries and splats oriented parallel to the substrate surface. Also, few pores were detected in the coating, thereby confirming the higher density of the Cr3C2-NiCr coating. A limited number of unmelted particles can be observed in the microstructures of the coatings. The coatings possess some voids  574 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 and oxide inclusions that are typical characteristics of the HVOF sprayed coatings. The oxides may form due to the in- flight oxidation during spraying process and/or preexisting in the feed material [26]. Fig.4 shows BSE micrograph from the cross-section of HVOF sprayed 75Cr3C2- NiCr coating on T91 boiler tube steel in as-sprayed condition. The porosities (black areas) and oxides (circular black areas) can be seen in the image (Fig. 4a). A high magnification of the back scattered images of the coating cross-sections can also be seen in Fig. 4b. Examination of the microstructure (Fig. 4b) of the coatings also reveals the presence of three different zones. The first zone is dark which indicates the presence of primarily Cr and C, revealing a Cr3C2 phase. The second zone is of grey colour, besides Cr and C this area also contains Ni. A third zone is white and consists of a NiCr phase, primarily. Porosity is inversely proportional to thermal conductivity, and will also be susceptible to penetration by corrosive reagents during operation on account of their open structure. Consequently, the need arises to employ denser coatings which degrade less due to their more Fig.3. Optical micrograph (Original magnification 50X) showing cross-section morphologies of HVOF sprayed 75Cr3C2-25NiCr coating on T91 boiler steels in as-sprayed condition. closely packed structure [27]. The porosity of the Cr3C2-NiCr coatings as reported by authors lies in the range of 1–3.5 % (Table 1), which was found to be useful in developing hot corrosion resistance in boiler tube steel [28, 29, 30]. The low value of porosity might be due to high kinetic energy of the powder particles. The dense coatings are supposed to provide very good corrosion resistance as compared to porous coatings, as porosities are the preferential corrosion paths through which the corrosive species can penetrate the coatings to reach the substrate and may cause rapid corrosion attack [26, 31]. It is standardized that coating thickness is approximately 300–500µm in the case of a cermet coating [14]. Thicker coatings permit the pass of the electrolyte due to the stresses generated during coating deposition and the corresponding crack formation between different layers. Thinner coated samples let the electrolyte go through the Coating Substrate  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 575 coating because it is not thick enough to correctly protect the base steel. Optimisation of spraying parameters and stress relaxation processes will be as important as thickness when protection of the base steel is needed with cermet coatings [14]. The microhardness values of the Cr3C2-NiCr coatings on different substrate materials as reported by different authors have been compiled in Table 1. Higher values of hardness for the coatings may be due to the high density and cohesive strength of the individual splats as a result of the high impact velocity of the coating particles as suggested by Sidhu TS et al [26] and Verdon C et al [41]. The non-uniformity of the hardness values of the coatings, along the distance is reported by many authors, this variation in hardness value is attributed to the microstructural changes along the cross-section of the coatings. These microstructural changes might be due to the presence of porosity; oxidised, melted, unmelted and semi-melted particles in the coating structure [22] as observed in the optical micrograph (Fig.3). Fig.4. BSEI micrograph showing cross-section morphology of HVOF sprayed 75Cr3C2- 25NiCr coating on T91boiler steels in as-sprayed condition. Fig.5. SEM micrograph and EDAX analysis surface of HVOF sprayed 75Cr3C2-25NiCr coating on T91 substrate. Coating Substrate Resin a b Element Wt.% C 04.21 O 04.07 Cr 55.31 N i 21.78 N b 07.62 Mo 06.16 Element Wt.% C 06.90 O 08.05 Cr 63.89 N i 10.05 N b 04.11 Mo 05.72 M M Pores  576 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 Author and Year Coatings Spray processPorosit y value Average Microhardn ess(Hv) XRD phase Substrate material Wang Y,1993[32] WC-12%Co D-gun 1219 MoCN315M low carbon steel WC-12%Co Plasma 1103 WC-20% Co D-gun 1003 TiC-20%Ni D-gun 865 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r D-gun 742 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r Plasma 382 Wang BQ,1994[33] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF <2% 750-900 Mild steel Wang BQ,1995[34] Cr3C2 HVOF <2% 804-990 AISI1018 low carbon steel 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF 1-2% 614-810 WC-17Co HVOF <1% 850-930 Wang BQ,1996[35] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiCr) HVOF 1-2% 614-810AISI1018 low carbon steel Wang BQ,1997[18] Cr3C2 HVOF <2% 804-990 AISI1018 low carbon steel 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF <2% 614-810 Wang J,2000[36] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r D-gun 1.9 Cr3C2 , Ni DIN 12CrMo44 Mateos J,2001[37] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r Plasma 561 AISI 1043 steel 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r Plasma with Laser remelting 655 Guilemany JM,2002[14] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF 1 – 2% 42 CrMo6 steel (UNS G11200) Sidhu HS,2006[6] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF 2.5 – 3.5% 850 Cr3C2, Ni, Cr, NiC, Cr2C SA213-T-11 steel 88WC – 12Co HVOF 1.5 – 2.5% 1000 Roy M,2006[9] Cr3C2 – 25(Ni20Cr) Conventional-crystalline grains HVOF 2% 980Mild steel Cr3C2 – 25(Ni20Cr) Nano-crystalline grains HVOF 1.5% 1140 Sidhu TS,2006[15] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF <1.5% 870 – 950 Ni- b ased superalloy(Superni 600) Douglas E,2006[38] 75Cr3C2-25NiC r Cold spray843 4140 alloy steel  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 577 Table1. Mechanical and microstructural characteristics of carbide based coatings The XRD diffractrograms of Cr3C2–NiCr coatings in as-sprayed conditions on different substrate materials as reported by the authors is depicted in Table 1. The SEM micrographs and the elemental compositions (surface) of HVOF Cr3C2-NiCr coatings on T91 boiler tube steel at selected points are depicted in Fig. 5. The micro-structure consists of interlocked particles with irregular morphology. There is a presence of some tiny particles in the coating, which might have formed after fracturing of some of the powder particles during spraying. Some unmelted and semimelted particles and pores can be seen in the coatings. Black spot in the microstructure is identified as porosity. The regions marked ‘M’ in these micrographs might have formed from the impact of fully molten feedstock droplets. SEM micrograph (Fig. 5) of as-sprayed Cr3C2– NiCr coating indicates the formation of the required composition for HVOF coatings, with NiCr metallic binder phase corresponds to the white region in the micrograph and the dark grey region as the carbides. 4. SOME STUDIES ON Cr2C3-NiCr COATINGS Components of power station boiler, gas turbines, internal combustion engines and industrial waste incinerators are subjected to frequent degradation by erosion–corrosion problems relevant to reliability and economics of these installations. The environment is characterized by high- temperature conditions together with aggressive atmospheres, leading to corrosive deposits adhere to the surface and to erosion processed due to the ash particles. Attempts to decrease the maintenance costs of these components have increased interest in shielding them with protective coatings [42]. Guilemany JM et al [14] investigated the role of coating thickness in the corrosion behaviour of steel protected with different numbers of HVOF sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr layers. . Electrochemical Souza RC,2008[19] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiCr HVOF 1-2% 897 AISI 4340 steel WC – 10Ni HVOF 1-2% 906 Ż órawski W,2008[39] WC12Co HVOF 1218 Carbon steel WC12Co APS 1021 Cr3C225(Ni20Cr) HVOF 945 Cr3C225(Ni20Cr) APS 788 Matthews S,2009[40] 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVAF (Aerospray 150) 1036 Cr3C2, NiCr Mild steel 75Cr3C2 – 25NiC r HVOF (GMA Microjet) 1163 Cr3C2, NiCr Tillmann W,2010[13] 75Cr3C2-25(Ni20Cr) powders (28+2 µm) HVOF 1.7%1004 C45 steel  578 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 measurements, such as Open-Circuit Potential, Polarisation Resistance and Cyclic Voltammetry, were performed in an aerated 3.4 NaCl media (%wt.). Electrochemical Impedance Measurements were also done in order to obtain a mechanism that explains the corrosion process. Results show that the corrosion resistance of the complete system is mainly influenced by the substrate behaviour. The application of a higher number of deposited layers did not substantially increase their anticorrosive properties. Stress generation during the spraying deposition process plays an important role in the behaviour of the coated steel against corrosion phenomena. Wang BQ et al [18] carried the elevated temperature erosion tests on cooled AlSl 1018 low- carbon steel and four thermal spray-coated mild steel specimens using a nozzle-type elevated temperature erosion tester. The thermal-sprayed coatings included a HVOF 75Cr3C2-25NiCr cermet coating, HVOF Cr3C2, low velocity flame-sprayed Cr2O3 ceramic coatings and an arc- sprayed FeCrSiB coating. Test conditions attempted to simulate the erosion conditions at the in- bed tubes of fluidized bed combustors. The specimens were water cooled on the backside. Material wastage was determined from thickness loss measurements of the specimens. Erosion test results were compared with those from testing isothermal specimens. It was found that the cooled specimens had greater material wastage than the isothermal specimens. The effect of cooling the specimen on the erosion wastage for 1018 steel was greater than that for the thermal- sprayed coatings. The lower material wastage of coated specimens compared to 1018 steel was related to the coatings composition and morphology. Among the four coatings tested the two hard coatings (HVOF Cr3C2, and low velocity flame-sprayed Cr2O3 ceramic coatings) exhibited lower erosion wastage than the other two coatings. The HVOF Cr3C2 coating exhibited the lowest erosion wastage due to its favorable composition and morphology. Which was about: three to 12 times lower than the erosion wastage of 1018 steel and the other three coatings. It had a finer structure and smaller splat size than the other three coatings. Further Wang BQ et al [43] carried out series of hot erosion tests on several carbide–metal composite coatings using a nozzle type elevated temperature erosion tester. The coatings included HVOF sprayed Cr3C2 cermet system and WC cermet coatings. 1018 low carbon steel and two arc-sprayed iron-base coatings were also tested for references. Bed ashes retrieved from different boilers were used as the erodent materials for tests at both shallow and steep impact angles. It was found that the all HVOF carbide cermet coatings showed much higher erosion resistance than 1018 steel and arc- sprayed iron-base coatings. Among the coatings tested the WC–17CrCo coating exhibited the highest erosion resistance. Among the HVOF Cr3C2 cermet system coatings the composite powder sprayed coatings showed higher erosion resistance than the blend powder sprayed coatings. The erosion behavior of the coatings is closely related to their microstructure, composition and the properties of erodent particles. Erosion resistance of FeCrAlY–Cr3C2 and NiCr– Cr3C2 cermet coatings with carbide levels ranging from 0–100% (in the pre-sprayed powder) was investigated by Stein KJ et al [24] in order to determine the optimum ceramic content for the best erosion resistance. Erosion testing  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 579 was carried out using a particle accelerator apparatus set at a velocity of 40 m/s, a mass flow of 80 g/min, and 400°C with 450 mm Al2O3 particles at 30° and 90° impact angles. Image analysis revealed the carbide levels in the pre-sprayed powder are much higher than in the final as sprayed coating. The lower carbide levels in the coatings are caused by a combination of poor carbide spray efficiency and reduction and oxidation of the carbide particles in the HVOF jet, resulting in the formation of various oxides and metal rich carbides. Erosion testing of the sprayed coatings found that decreasing the carbide content, and overall hard phase content (oxides and carbides), decreased the erosion rate for 90° impact. In addition, for 30° impact the erosion rate remained fairly constant regardless of carbide or hard phase content. In a comparative study of HVOF sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr and Ni–20Cr coatings on a Ni-based superalloy in a molten salt environment of Na2SO4–60%V2O5 at 900 °C under cyclic conditions, Sidhu TS et al [15] found that the hot corrosion resistance of Ni–20Cr coating was better than Cr3C2–NiCr coating. The presence of oxides of nickel and chromium and their spinels NiCr2O4, and uniform fine grain microstructure of the as sprayed coating might have contributed for better hot corrosion resistance of HVOF sprayed Ni–20Cr wire coating. These oxides might have blocked the pores and splat boundaries, and acted as diffusion barriers to the inward diffusion of oxidizing species. Kamal S et al [23] investigated the hot corrosion resistance of detonation gun sprayed Cr3C2– NiCr coatings on Superni 75, Superni 718 and Superfer 800H superalloys. Thermogravimetry technique is used to study the high temperature hot corrosion behavior of bare and Cr3C2–NiCr coated superalloys in molten salt environment (Na2SO4–60% V2O5) at high temperature 900 ◦C for 100 cycles. Results show that Cr3C2–NiCr coating can be successfully deposited by Detonation gun spraying process on Ni and Fe-based superalloy substrates, with uniform, adherent and dense microstructure with porosity less than 0.8%. Cr3C2–NiCr coatings on Ni- and Fe-based superalloy substrates are found to be very effective in decreasing the corrosion rate in the given molten salt environment at 900 ◦C. Particularly, the coating deposited on Superfer 800H showed a better hot corrosion protection as compared to Superni 75 and Superni 718. The coatings serve as an effective diffusion barrier to preclude the diffusion of oxygen from the environment into the substrate superalloys. It is concluded that the hot corrosion resistance of the D-gun sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr coating is due to the formation of desirable microstructural features such as very low porosity, uniform fine grains, and the flat splat structures in the coating. Further Kamal S et al [3] investigation hot corrosion behaviour of Cr3C2–NiCr cermet coatings deposited on two Ni-based superalloys, namely superni 75, superni 718 and one Fe-based superalloy superfer 800H by detonation-gun thermal spray process. The cyclic hot-corrosion studies were conducted on uncoated as well as D-gun coated superalloys in the presence of mixture of 75 wt.% Na2SO4+25 wt.% K2SO4 film at 900 °C for 100 cycles. It was observed that Cr3C2–NiCr- coated superalloys showed better hot-corrosion resistance than the uncoated superalloys in the presence of 75 wt.% Na2SO4+ 25 wt.% K2SO4 film as a result of the formation of continuous and protective oxides of chromium, nickel and their spinel, as evident from the XRD analysis. The  580 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 surface oxide scale developed on coated superalloys is massive, crack free, with dense clusters mainly consisting of oxides of Cr and Ni, in which, irregular disc shaped Cr2O3 distributed throughout the top surface of the scale. Cr3C2–NiCr-coated and uncoated superalloys superni 718 and superfer 800H showed the lowest and highest weight gains, respectively, in the given environment. In another study Kamal S et al [44] investigated the cyclic oxidation behavior of detonation-gun- sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr coating on three different superalloys namely Superni 75, Superni 718 and Superfer 800H at 900 °C for 100 cycles in air under cyclic heating and cooling conditions. The kinetics of oxidation of coated and bare superalloys was analysed, using thermogravimetric technique. It was observed that all the coated and bare superalloys obey a parabolic rate law of oxidation. The results on the Cr3C2–NiCr-coated superalloys showed better oxidation resistance due to the formation of a compact and adhesive thin Cr2O3 scale on the surface of the coating during oxidation. The scale remained intact and adherent to the partially oxidised coating during cyclic oxidation due to its good compatibility and similar thermal expansion coefficient between Cr3C2–NiCr coating and the superalloy substrates. In all the coated superalloys, the chromium, iron, silicon and titanium were oxidised in the inter-splat region, whereas splats which consisted mainly of Ni remained unoxidised. Souza RC [19] compared the influence of Cr3C2–25NiCr and WC–10Ni coatings applied by HVOF process and hard chromium electroplating on the fatigue strength, abrasive wear and corrosion resistance of AISI 4340 steel. S–N curves were obtained in axial fatigue tests for base material, chromium plated and HVOF coated specimens. HVOF coated specimens showed higher axial fatigue resistance and better performance in wear weight loss in comparison to electroplated chromium. Further for Cr3C2–25NiCr HVOF coating, results indicate clearly the higher salt spray resistance and higher microhardness than for chromium electroplated. 5. POST TREATMENT STUDIES ON Cr3C2-NiCr COATINGS Porosity or voids in the coating micro structure is an important issue in thermal spraying, as due to this physical property, corrosion resistance of different thermal spraying coatings differs [45]. To reduce the internal stresses, interconnected porosity and inter splat boundaries, coatings are post treated by various methods such as heat treatment, sealing, laser remelting etc [46]. In a study by Zhang S-H et al [16] compared to the original HVOF WC–CoCr coating, the laser treatment has essentially eliminated the porosity, providing a more homogeneous and densified microstructure. After laser heat treatment, the thickness of the coating has decreased from 300 μm to 225 μm. As a result, the average porosity in the laser-treated material has been reduced by a factor of approximately five compared to the nonlaser heat-treated material. The laser treatment has produced a considerable increment in the hardness of the coating near the surface where the  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 581 average value increases from Hv0.2=1262.4 in the HVOF-sprayed coating to Hv0.2=1818.7 in the laser-treated coatings. Wang BQ et al [47] evaluated high temperature erosion resistance of several thermal sprayed coatings under as-deposited, post heat-treated and sealed conditions using a nozzle type elevated temperature erosion tester. The coatings included high velocity continuous combustion (HVCC) arc sprayed metal and ceramic coatings, and high velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) sprayed metal and carbide cermet coatings. The heat treatment was performed at 500°C for 24 hours, after heating the samples were cooled in air. For sealing coating a high temperature aluminum phosphate based sealant was used. It was found that post heat-treating and sealing of coatings increased the elevated temperature erosion resistance of coatings. Sealed coatings with aluminum phosphate based sealant also proved beneficial in increasing the erosion resistance from a few percent up to twice for both metal and carbide cermet coating. Matthews S et al [48] investigations the variation in microhardness in high velocity sprayed 75Cr3C2–25NiCr coatings after exposure to heat treatment at 900 °C for a period of up to 60 days in air and argon as a function of microstructural development. The results showed that with treatment, matrix phase supersaturation was reduced, while widespread carbide nucleation and growth generated an expansive carbide skeletal network. An initial softening of the coatings occurred through matrix phase refinement, the subsequent hardness recovery was a function of carbide development. The changes in hardness with heat treatment were accompanied by concurrent changes in microstructure—namely the precipitation of fine carbides and their subsequent growth; and the recrystalisation of the matrix. Treatment in air generated further hardness increases as a result of internal oxidation Further Matthews SJ et al [22] investigated the influence of structure on erosion performance of high velocity air fuel and high velocity oxygen fuel sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr coatings under industrial turbine conditions. Coated samples were heat treated in air at 900 °C for 30 days. Erosion testing of as-sprayed and heat treated coatings was conducted at ambient and elevated temperature. Single impacts were characterised using Scanning Electron Microscopy in order to determine the erosion mechanism. Results show that at ambient temperature as-sprayed HVOF and HVAF Cr3C2–NiCr coating deformation occurred through brittle cracking and fracture of the matrix phase, along with extensive brittle crack propagation along the carbide–matrix interfaces. The coating splat structure was a preferential path for crack propagation in the HVOF coating but less significant in the HVAF coating. During erosion at 800 °C the ductility of the as-sprayed coatings significantly increased. Therefore the main effect of in-flight degradation of the coatings was to reduce the carbide concentration. Heat treatment reduced the extent of the brittle matrix response, improving the matrix ductility and the overall coating toughness. It also led to sintering of the splats reducing the influence of the splat structure and increasing the influence of the microstructure. Carbide precipitation occurred with heat treatment to form an extensive network which resisted relative  582 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 movement of the carbides during impact, while also enabling the applied load to be distributed over a larger volume of the coating, forming a more erosion resistant microstructure. Matthews S et al [49] investigated relative erosion rate of Cr3C2-NiCr coatings at 7000 C and 8000 C under impact velocity of 225-235m/s, under simulated conditions of turbine environment. HVAF and HVOF sprayed coatings produced comparable erosion rates in both as sprayed and heat treated coatings, which can be related to the complex transition in influence of the brittle matrix phase in the as-sprayed state and impact of the three dimensional carbide network following in heat treated samples. However the ductility of the NiCr matrix phase significantly increased for both coatings at 8000 C, but the erosion rate of heat treated samples increased due to the increasing constraint imposed upon the matrix by the developing carbide microstructure. Suarez M et al [50] investigated the corrosion resistance of, as coated and post treated Cr3C2– NiCr coating of 450 μm thickness, deposited by a vacuum plasma spray process (VPS) on a steel substrate. The post-heat treatment of coating was done by heating as-deposited coating in Ar at 400 °C and 800 °C, respectively. Electron probe micro analyzer (EPMA) with wavelength dispersive X-ray spectrometers (WDS) was used to characterize the coatings. Results showed that no significant changes were produced by heat treatment at 400 °C whereas the coating annealed at 800 °C has a better corrosion resistance than the as-deposited coating due to the microstructural changes that take place in the coating and the diffusion of Ni into Fe at the coating–substrate interface, which ensures the presence of a metallurgical bond. 6. CONCLUSION In the present work detailed literature review have been done, along with some brief characterisation work by the author for HVOF sprayed 75Cr3C2-25NiCr coating on T91 steel and following conclusions are made: 1. Degradation of metals and alloys due to hot corrosion or erosion has been identified as a serious problem for many high temperature aggressive environment applications. 2. Carbide coatings can be successfully deposited over the substrate material by HVOF, Detonation gun and Plasma Spray processes. Cr3C2–NiCr coatings offer excellent corrosion and oxidation resistance, also having a high melting point and maintaining high hardness, strength and wear resistance at high temperature. 3. It has been learnt from literature that detailed studies are needed to optimize the composition of cermet coatings for erosive-corrosive environments. The erosion resistance of cermet coatings increases with an increase in chromium carbide in the pre-sprayed powder. Researchers agree that carbide-based coatings provide excellent erosion protection, but disagree on the optimum amount of carbide for maximum erosion resistance. 4. The thermal sprayed coatings consist of oxides and voids originating from spraying process that are found at the splat boundaries, through which the coatings were mainly attacked. Consequently, the need arises to employ denser coatings which degrade less due to their more  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 583 closely packed structure. Further post treatments such as heat treatment and sealing of carbide based coatings are reported with positive results, so need arises to post treat the coatings to further enhance their life for different applications. 5. Although different authors have made the efforts to understand the mechanism of hot corrosion using carbide based coatings in different aggressive environments in the laboratory but still long term exposure of these coatings in actual industrial environment needs to be studied for estimating the protection capabilities of these coatings. REFERENCE [1] Sidhu TS, Malik A, Prakash S, Agrawal RD. Oxidation and Hot Corrosion Resistance of HVOF WC-NiCrFeSiB Coating on Ni- and Fe-based Superalloys at 800 °C. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2007; 16(5-6); 844-849. [2] Mahesh RA, Jayaganthan R, Prakash S. Evaluation of hot corrosion behaviour of HVOF sprayed NiCrAl coating on superalloys at 900°C. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008; 111; 524–533. [3] Kamal S, Jayaganthan R, Prakash S. Evaluation of cyclic hot corrosion behaviour of detonation gun sprayed Cr3C2–25%NiCr coatings on nickel- and iron-based superalloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009; 203; 1004–1013. [4] Sidhu TS, Prakash S, Agrawal RD. Hot corrosion performance of a NiCr coated Ni-based alloy. Scripta Mater. 2006; 55; 179–182. [5] Poza P, Gran PS. Microstructure evolution of vacuum plasma sprayed CoNiCrAlY coatings after heat treatment and isothermal oxidation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006; 201; 2887–2896. [6] Sidhu HS, Sidhu BS, Prakash S. Mechanical and microstructural properties of HVOF sprayed WC–Co and Cr3C2–NiCr coatings on the boiler tube steels using LPG as the fuel gas. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006; 171; 77–82. [7] Miranda JC, Ramalho A. Abrasion resistance of thermal sprayed composite coatings with a nickel alloy matrix and a WC hard phase. Effect of deposition technique and re-melting. Tribol. Lett. 2001;11(1);37-48. [8] Khanna AS, Kumari S, Kanungo S, Gasser A. Hard coatings based on thermal spray and laser cladding. Int. J. of Refract. Met. H. 2009; 27; 485–491. [9] Roy M, Pauschitz A, Polak R, Franek F. Comparative evaluation of ambient temperature friction behaviour of thermal sprayed Cr3C2–25(Ni20Cr) coatings with conventional and nano-crystalline grains. Trib. Int. 2006; 39; 29–38. [10] Crawmer DE. Introduction to coatings, equipment and theory. In: Davis JR, editor. Hand book of thermal spray technology, ASM International, Materials Park, OH, USA; 2004; p. 43-46. [11] Bala N, Singh H, Prakash S. High-temperature oxidation studies of cold-sprayed Ni–20Cr and Ni–50Cr coatings on SAE 213-T22 boiler steel. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009; 255; 6862– 6869.  584 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 [12] Bolelli G, Cannillo V, Lusvarghi L, Montorsi M, Mantini FP, Barletta M. Microstructural and tribological comparison of HVOF-sprayed and post-treated M–Mo–Cr–Si (M = Co, Ni) alloy coatings. Wear 2007; 263; 1397–1416. [13] Tillmann W, Vogli E, Baumann I, Kopp G, Weihs C. Desirability-Based Multi-Criteria Optimization of HVOF Spray Experiments to Manufacture Fine Structured Wear-Resistant 75Cr3C2-25(NiCr20) Coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2010; 19(1-2); 392–408. [14] Guilemany JM, Ferna´ndez J, Delgado J, Benedetti AV, Climent F. Effects of thickness coating on the electrochemical behaviour of thermal spray Cr3C2–NiCr coatings, Surf. Coat. Technol. 2002; 153; 107–113. [15] Sidhu TS, Prakash S, Agrawal RD, Hot corrosion studies of HVOF sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr and Ni–20Cr coatings on nickel-based superalloy at 900 °C. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006; 201; 792–800. [16] Shi-Hong Zhang, Tong-Yul Cho, Jae-Hong Yoon, Fang W, Ki-O Song, Ming-Xi Li, Yun- Kon Joo, Lee CG. Characterization of microstructure and surface properties of hybrid coatings of WC–CoCr prepared by laser heat treatment and high velocity oxygen fuel spraying. Mater. Charact. 2008; 59; 1412-1418. [17] Ruhi G, Modi OP, Sinha ASK, Singh IB. Effect of sintering temperatures on corrosion and wear properties of sol–gel alumina coatings on surface pre-treated mild steel. Corros. Sci. 2008; 50; 639–649. [18] Wang BQ, Lee SW. Elevated temperature erosion of several thermal-sprayed coatings under the simulated erosion conditions of in-bed tubes in a fluidized bed combustor. Wear 1997; 203-204; 580-587. [19] Souza RC, Voorwald HJC, Cioffi MOH. Fatigue strength of HVOF sprayed Cr3C2–25NiCr and WC-10Ni on AISI 4340 steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008; 203; 191–198. [20] Fernandez E, Garcıa JR, Cuetos JM, Higuera V. Behaviour of laser treated Cr, Ni coatings in the oxidative atmosphere of a steam boiler. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2005;195;1– 7. [21] Bala N, Singh H, Prakash S. An overview of characterizations and high temperature behaviour of thermal spray NiCr coatings. Int. J. Mater. Sci. 2007;2(3);201-218. [22] Matthews SJ, James BJ, Hyland MM. Microstructural influence on erosion behaviour of thermal spray coatings. Mater. Charact. 2007; 58; 59–64. [23] Kamal S, Jayaganthan R, Prakash S, Kumar S. Hot corrosion behavior of detonation gun sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr coatings on Ni and Fe-based superalloys in Na2SO4–60% V2O5 environment at 900 °C. J. Alloys Compd. 2008; 463; 358–372. [24] Stein KJ, Schorr BS, Marder AR. Erosion of thermal spray MCr–Cr C cermet coatings. Wear 1999; 224; 153–159. [25] Seong BG, Hwang SY, Kimb KY. High-temperature corrosion of recuperators used in steel Mills. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000; 126; 256-265. [26] Sidhu TS, Prakash S, Agrawal RD. Characterizations of HVOF sprayed NiCrBSi coatings on Ni- and Fe-based superalloys and evaluation of cyclic oxidation behaviour of some Ni- based superalloys in molten salt environment. Thin Solid Films 2006; 515; 95–105.  Vol.11, No6 Characterisation and corrosion-erosion behaviour 585 [27] Lawrence J, Lib L. Augmentation of the mechanical and chemical resistance characteristics of an Al2O3-based refractory by means of high power diode laser surface treatment. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003; 142; 461–465. [28] Sahraoui T, Fenineche N-E, Montavon G, Coddet C. Structure and Wear Behavior of HVOF Sprayed Cr3C2-NiCr and WC-Co Coatings. Mater. Des. 2003; 24(5); 309-313. [29] Lih W-C, Yang SH, Su CY, Huang SC, Hsu IC, Leu MS. Effects of Process Parameters on Molten Particle Speed and Surface Temperature and the Properties of HVOF CrC/NiCr Coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000; 133-134; 54-60. [30] Sidhu HS, Sidhu BS, Prakash S. The role of HVOF coatings in improving hot corrosion resistance of ASTM-SA210 GrA1 steel in the presence of Na2SO4–V2O5 salt deposits. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2006; 200; 5386–5394. [31] Sidhu BS, Prakash S. Studies on the behaviour of stellite-6 as plasma sprayed and laser remelted coatings in molten salt environment at 900 °C under cyclic conditions. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006; 172; 52–63. [32] Wang Y. Friction and wear performances of detonation-gun- and plasma-sprayed ceramic and cermet hard coatings under dry friction. Wear 1993; 161; 69-8. [33] Wang BQ, Luer K. The erosion-oxidation behavior of HVOF Cr3C2-NiCr cermet coating. Wear 1994; 174; 177-185. [34] Wang BQ. Erosion-corrosion of coatings by biomass-fired boiler fly ash. Wear 1995; 188; 40-48. [35] Wang BQ. Effect of alkali chlorides on erosion-corrosion of cooled mild steel and Cr3C2- NiCr coating. Wear 1996; 199; 268-274. [36] Wang J, Zhang L, Sun B, Zhou Y. Study of the Cr3C2-NiCr detonation spray coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2000; 130; 69-73. [37] Mateos J, Cuetos JM, Vijande R, Ferna´ndez E. Tribological properties of plasma sprayed and laser remelted 75/25 Cr3C2/NiCr coatings. Trib. Int. 2001;34;345–351. [38] Wolfe DE, Eden TJ, Potter JK, Jaroh AP. Investigation and Characterization of Cr3C2-Based Wear-Resistant Coatings Applied by the Cold Spray Process. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2006; 15(3); 400-512. [39] Żórawski W, Kozerski S. Scuffing resistance of plasma and HVOF sprayed WC12Co and Cr3C2-25(Ni20Cr) coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008; 202; 4453–4457. [40] Matthews S, James B, Hyland M. The role of microstructure in the mechanism of high velocity erosion of Cr3C2–NiCr thermal spray coatings: Part 1—As-sprayed coatings, Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009; 203; 1086–1093. [41] Verdon C, Karimi A, Martin J-LA. Study of High Velocity Oxy- Fuel Thermally Sprayed Tungsten Carbide Based Coatings. Part 1: Microstructures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1998; 246; 11-14. [42] Tao K, Zhou X, Cui H, Zhang J. Microhardness variation in heat-treated conventional and nanostructured NiCrC coatings prepared by HVAF spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009; 203; 1406–1414.  586 Sukhpal Singh Chatha, Hazoor S. Sidhu Vol.11, No.6 [43] Wang BQ, Shui ZR. Hot erosion behavior of carbide–metal composite coatings. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2003; 143–144; 87–92. [44] Kamal S, Jayaganthan R, Prakash S. High temperature oxidation studies of detonation-gun- sprayed Cr3C2–NiCr coating on Fe- and Ni-based superalloys in air under cyclic condition at 900 °C. J. Alloys Compd. 2009; 472; 378–389. [45] Sidhu TS, Prakash S, Agrawal RD. Hot corrosion and performance of nickel-based coatings. Current Sci. 2006; 90(1); 41-47. [46] Sundararajan G, Sudharshan PP, Jyothirmayi A, Gundakaram RC. The influence of heat treatment on the micro structural, mechanical and corrosion behaviour of cold sprayed SS 316L coatings. J of Mater Sci. 2009; 44; 2320–2326. [47] Wang BQ. Effect of post heat treatment and sealing on erosion resistance of several thermal sprayed coatings. Proceedings of ICSE, Southwest Jiaotong University Press, Chengdu, China, 2002; 138–143. [48] Matthews S, Hyland M, James B. Microhardness variation in relation to carbide development in heat treated Cr3C2–NiCr thermal spray coatings. Acta Mater. 2003; 51; 4267–4277. [49] Matthews S, James B, Hyland M. High temperature erosion of Cr3C2-NiCr thermal spray coatings—The role of phase microstructure. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2009; 203(9); 1144-1153. [50] Suarez M, Bellayer S, Traisnel M, Gonzalez W, Chicot D, Lesage J, Puchi-Cabrera ES, Staia MH. Corrosion behavior of Cr3C2–NiCr vacuum plasma sprayed coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008; 202(18); 4566–4571. |