Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

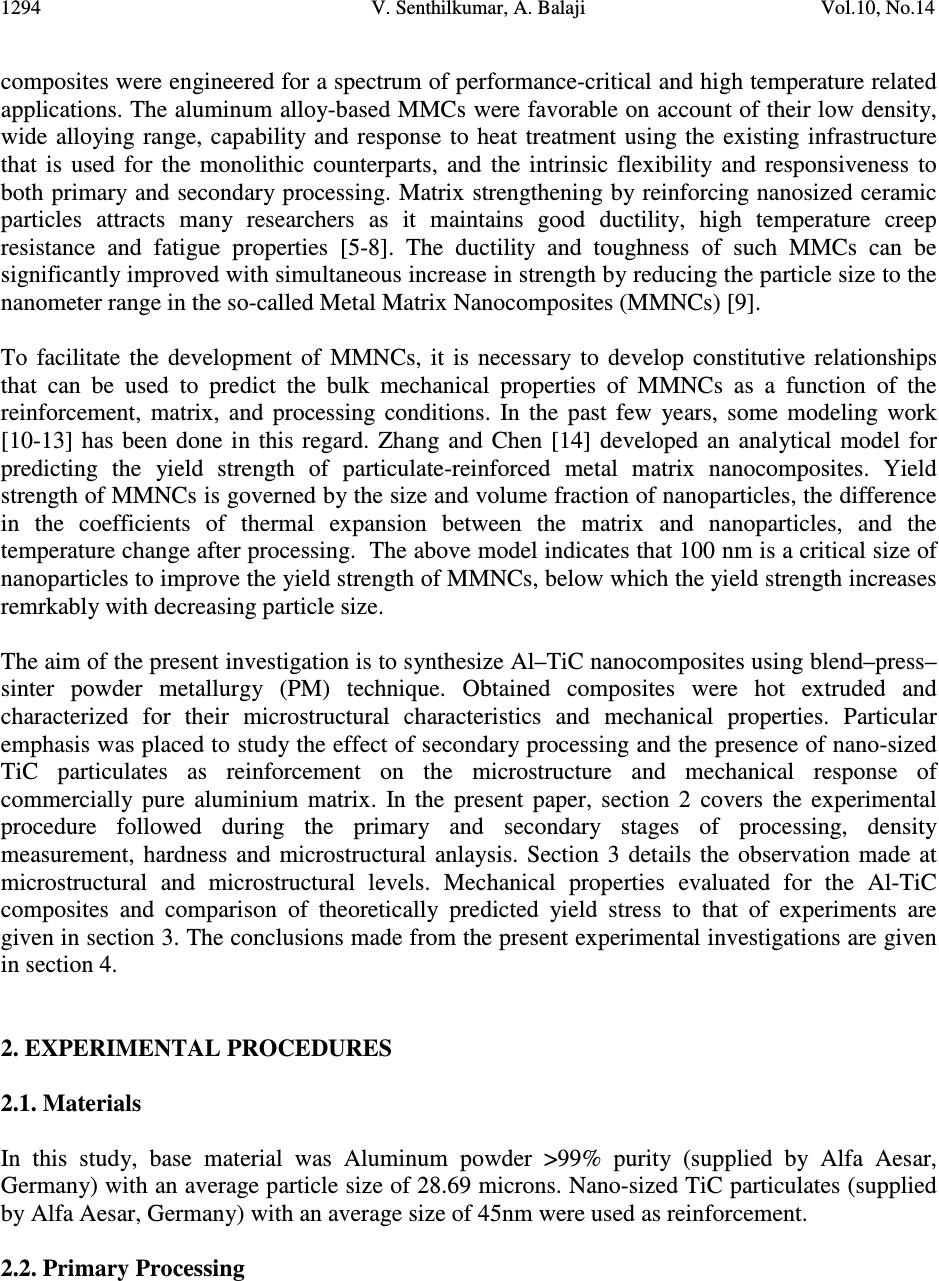

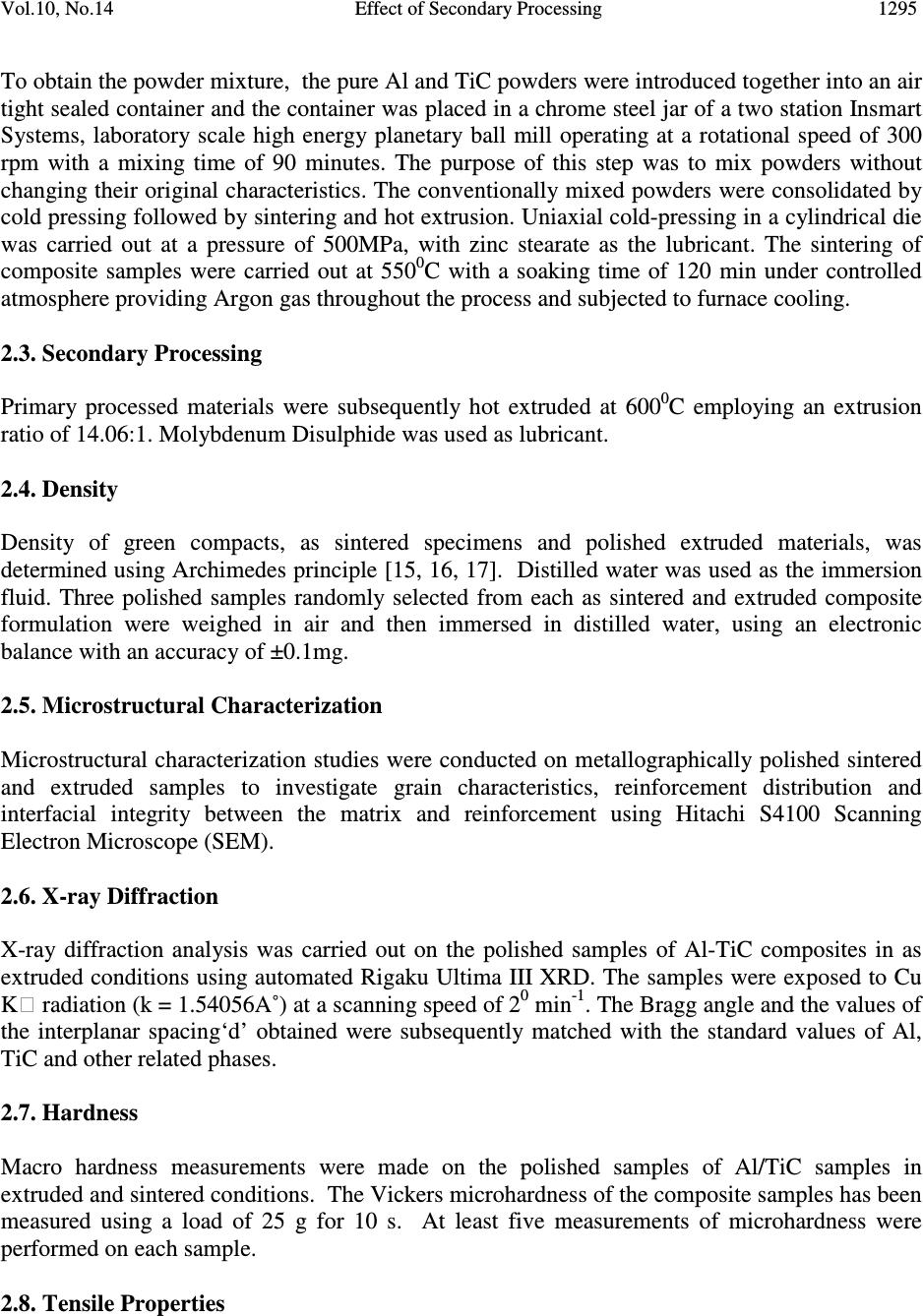

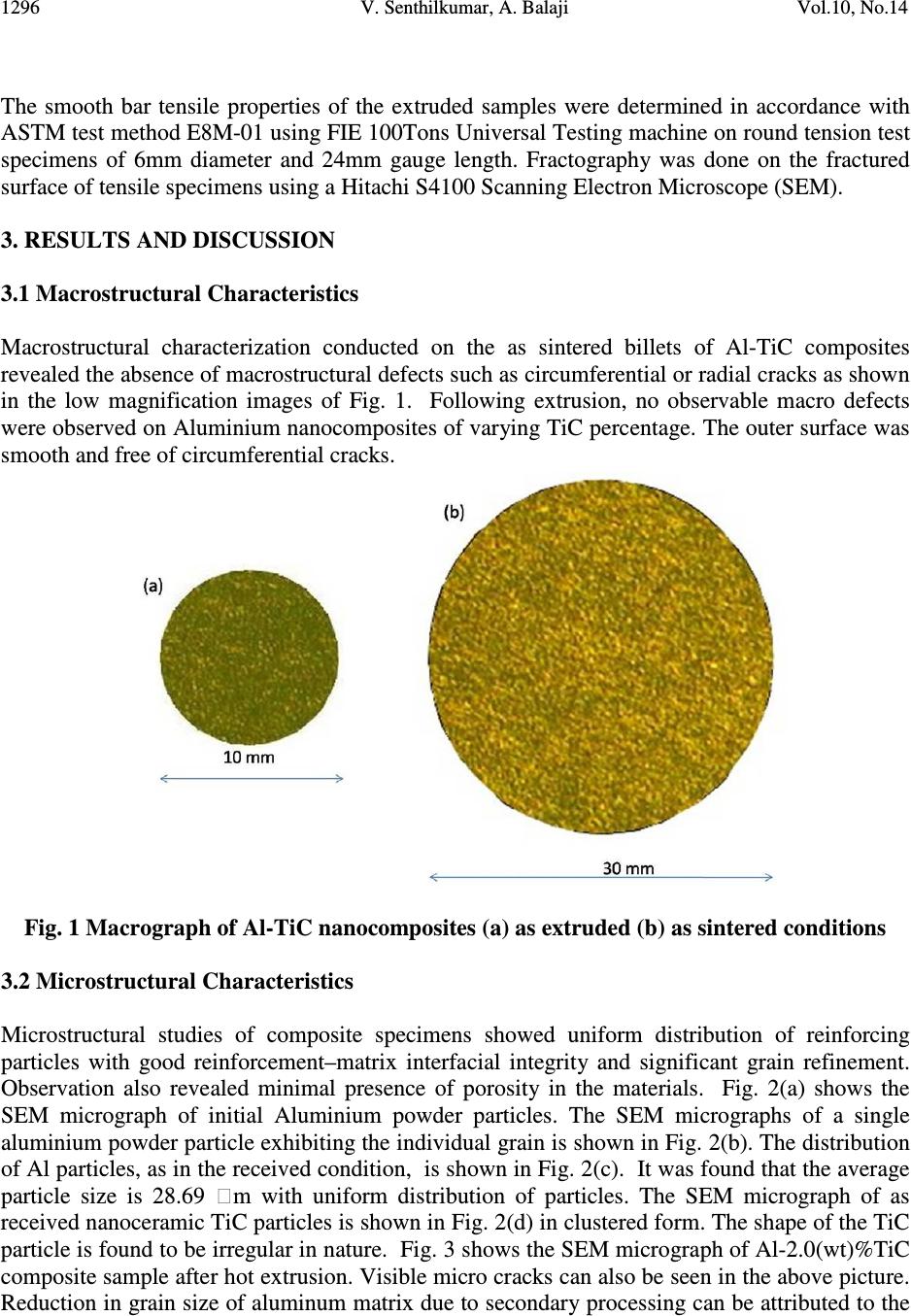

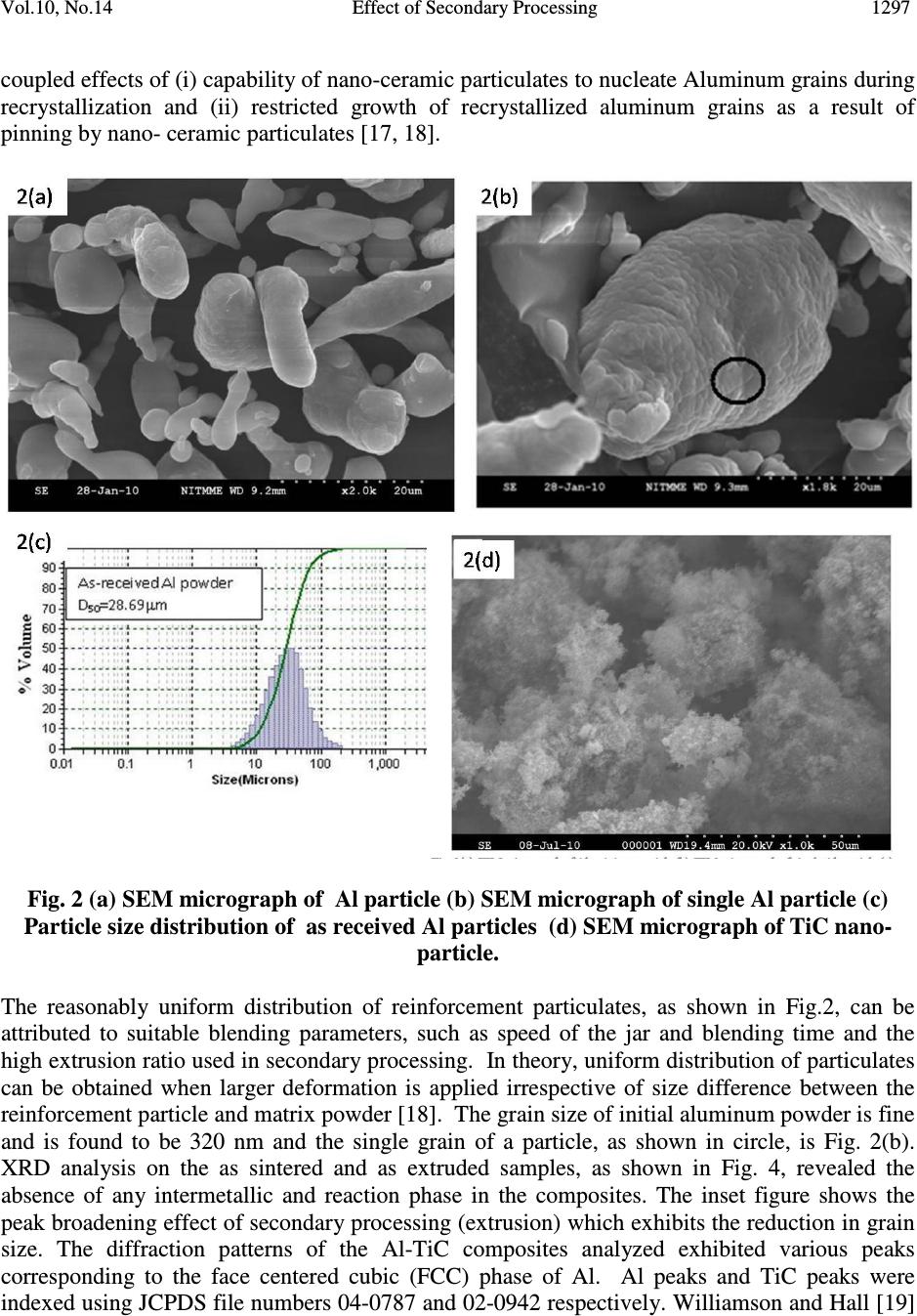

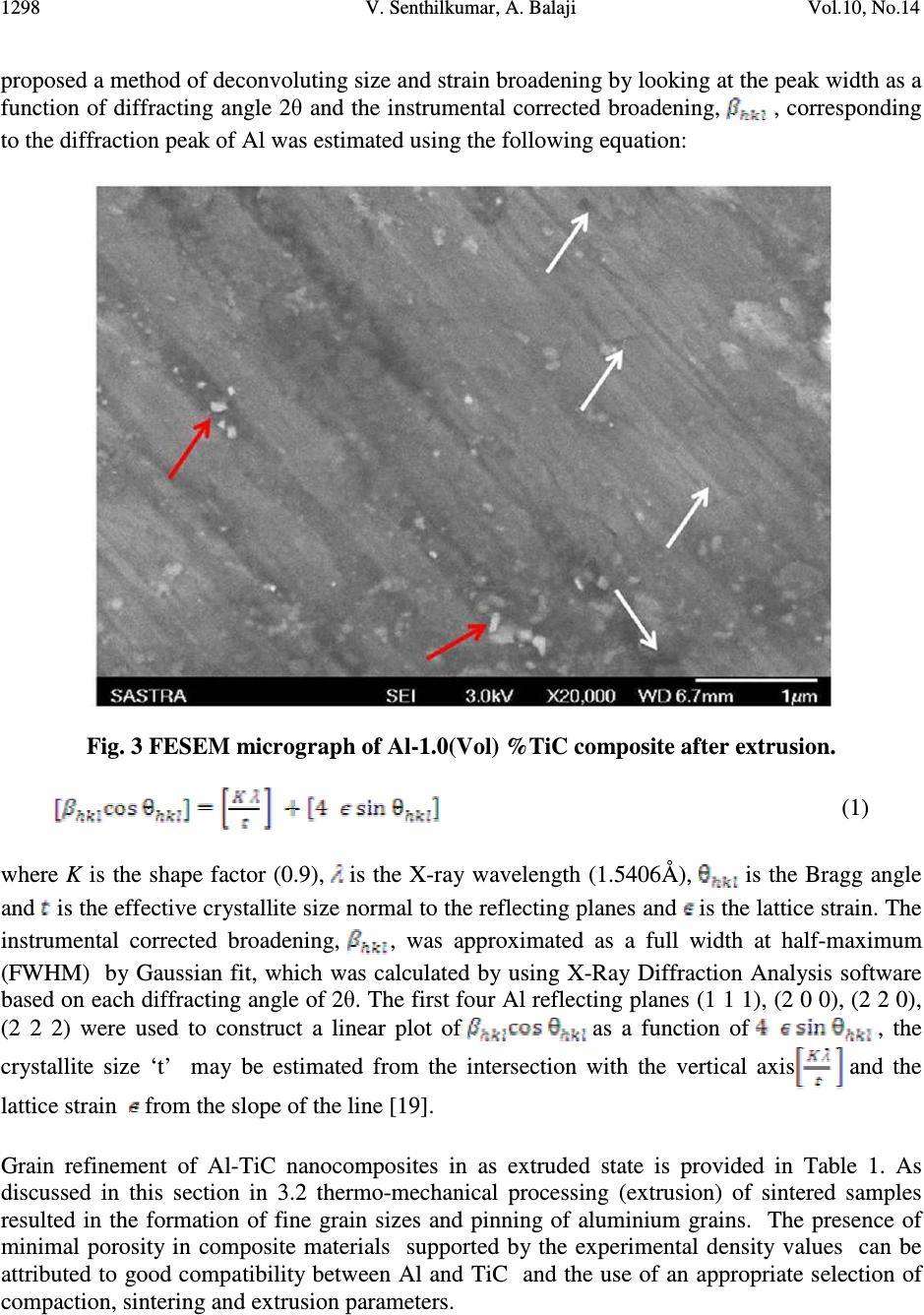

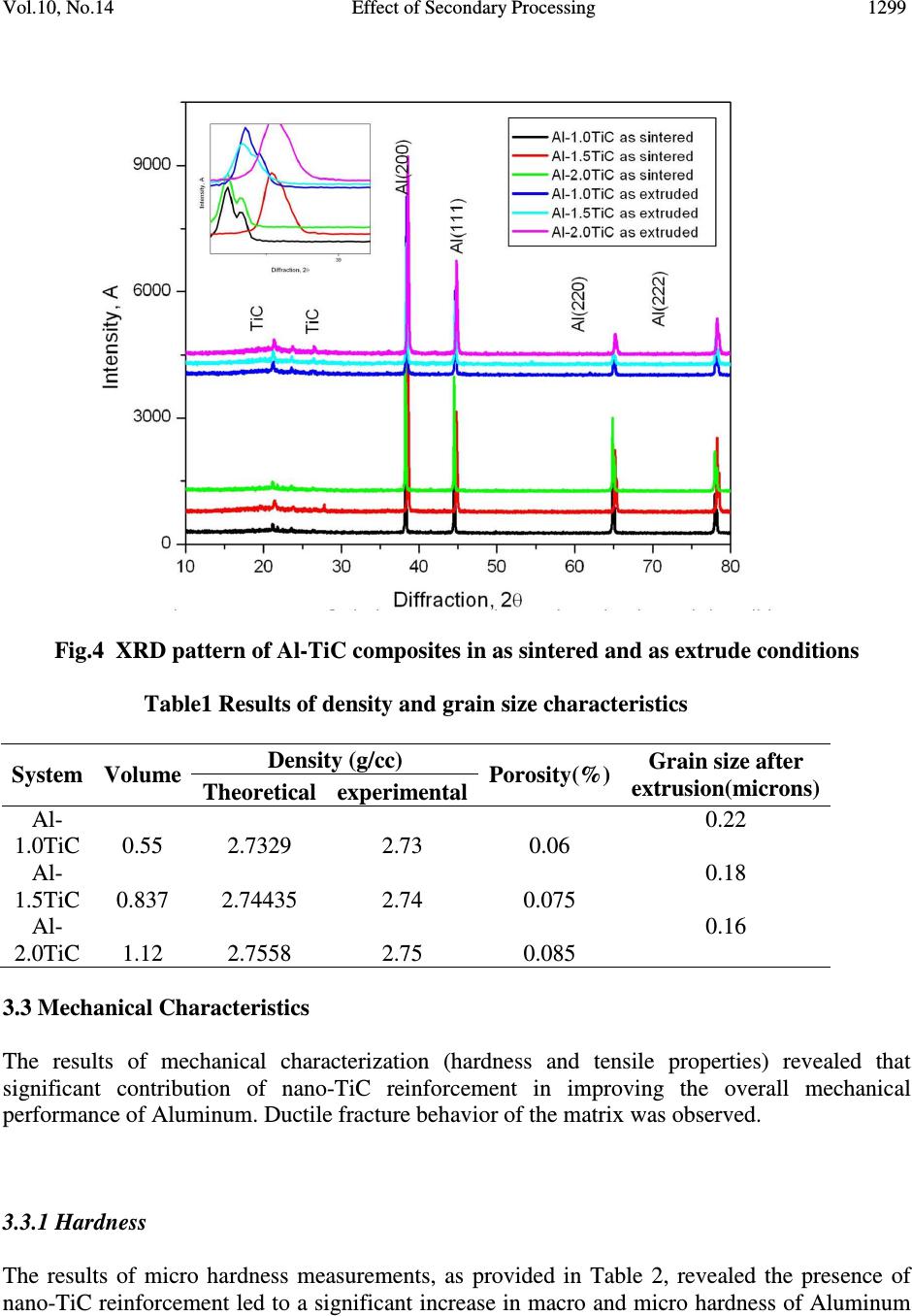

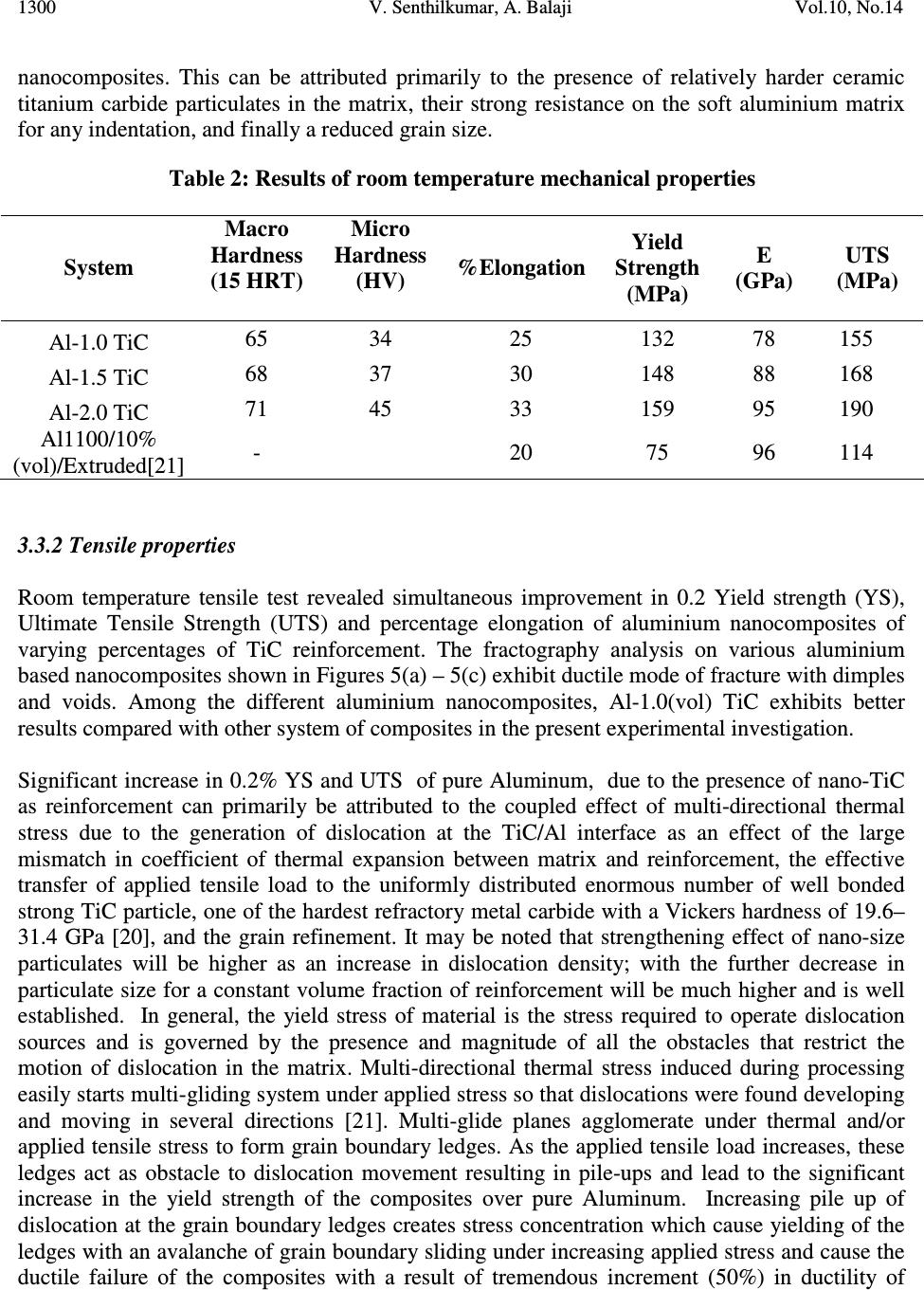

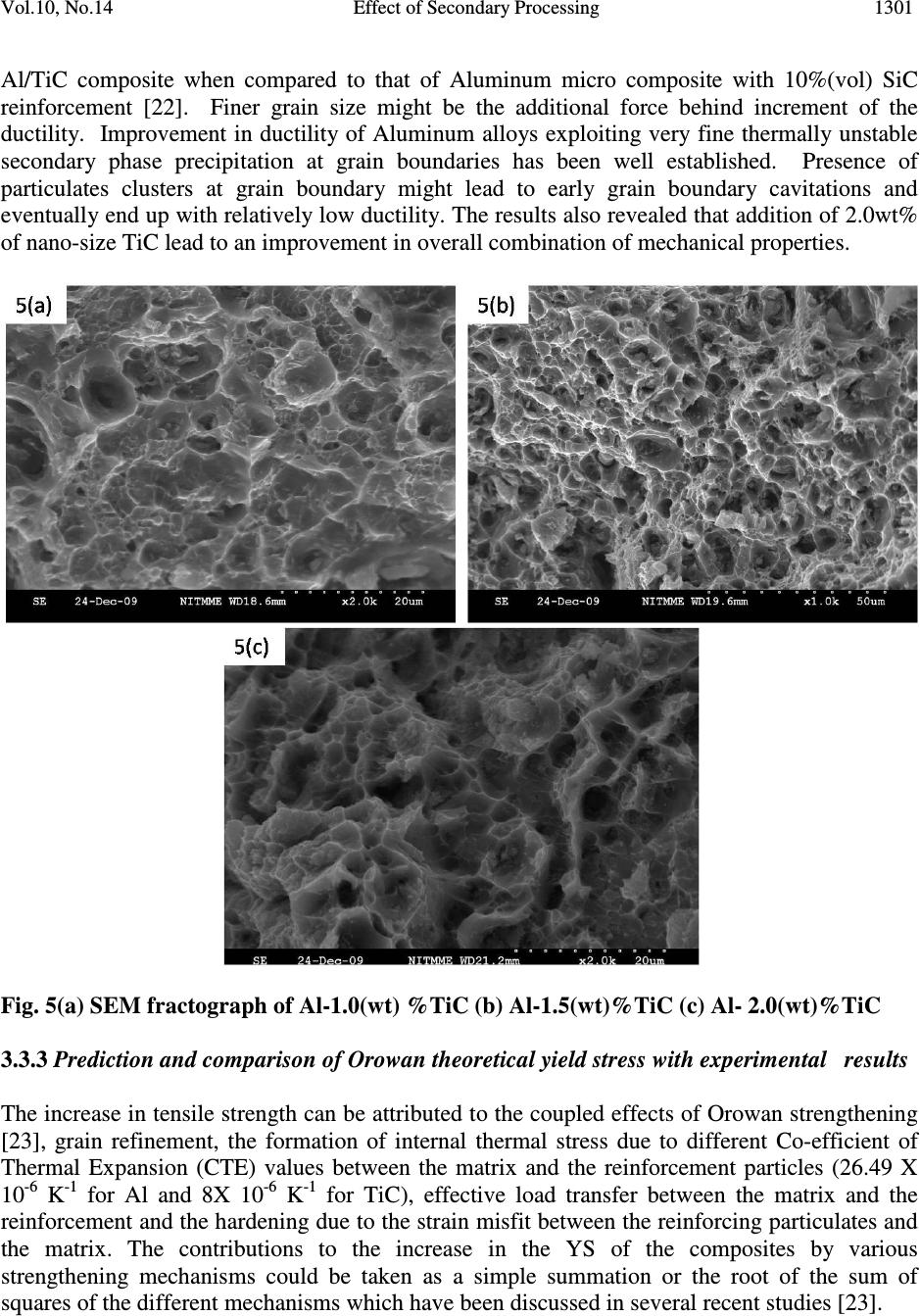

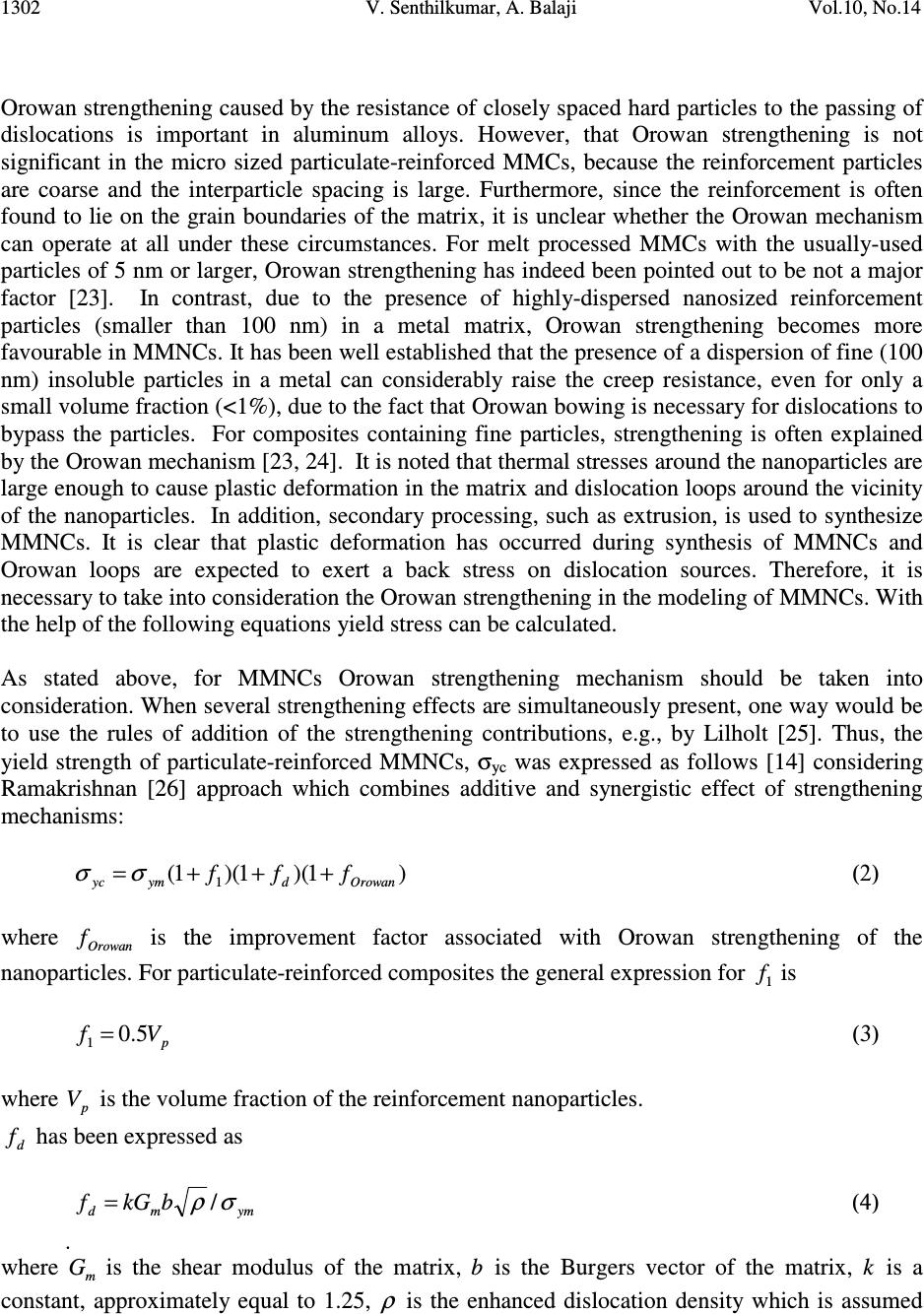

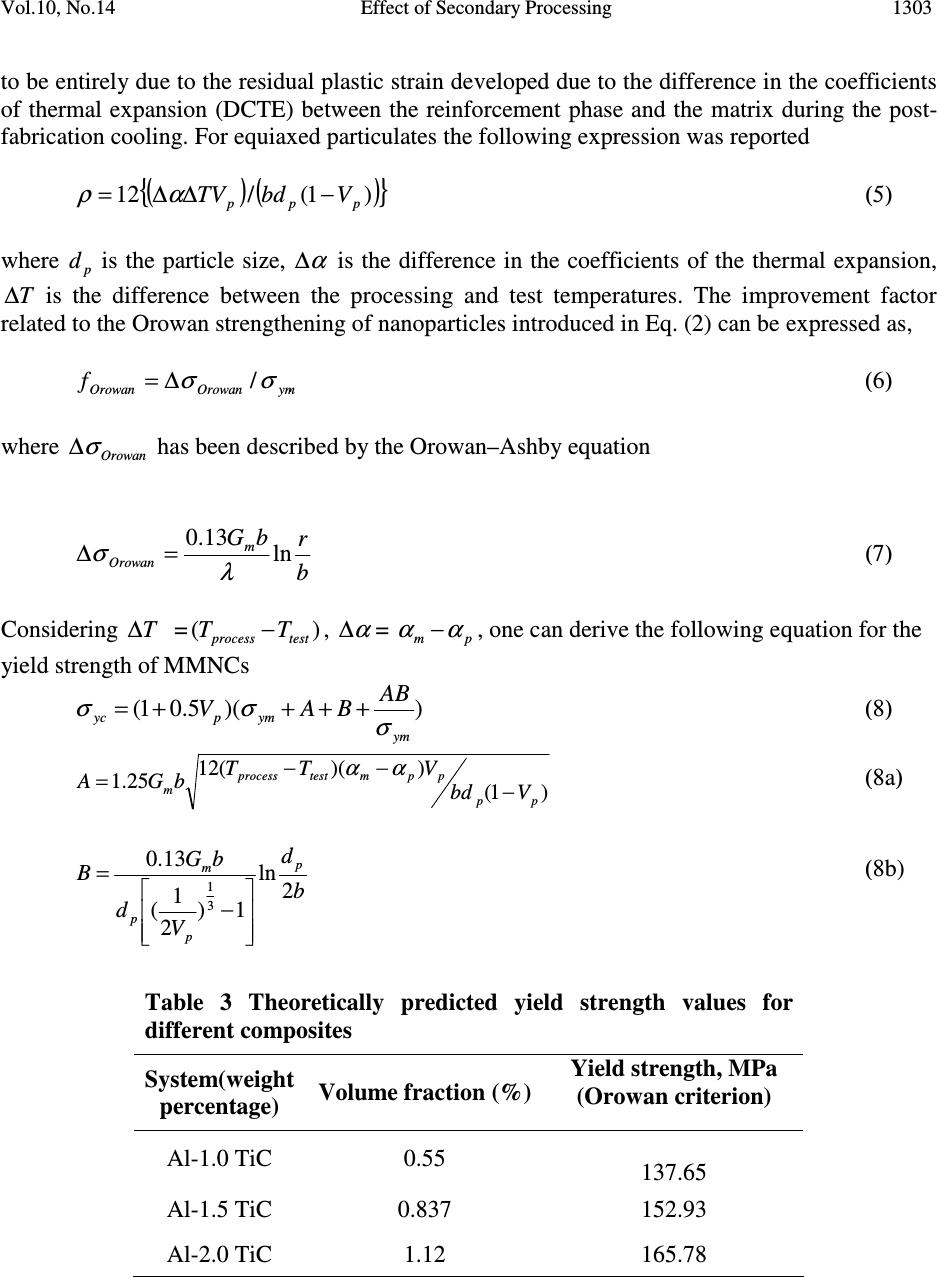

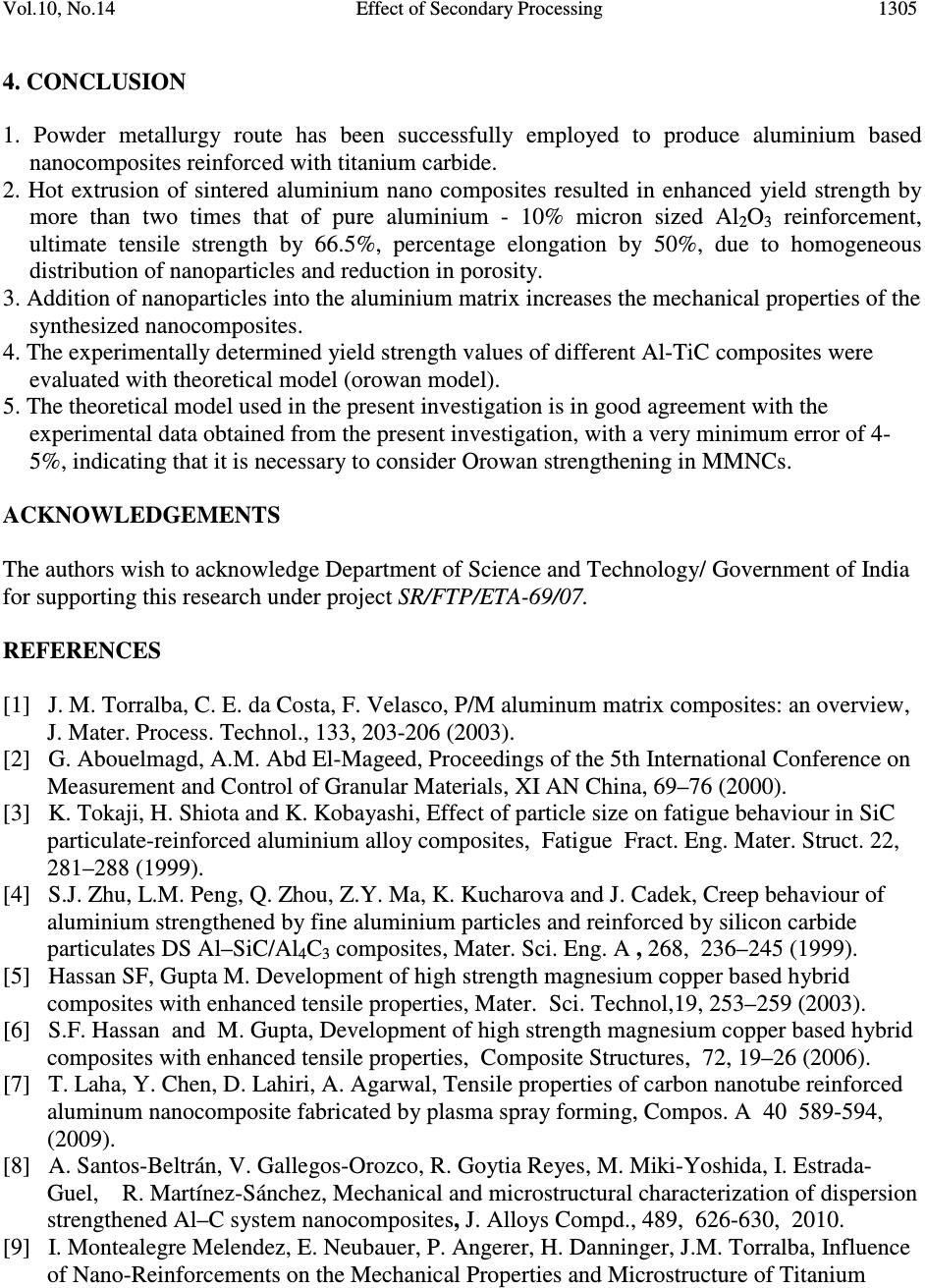

Journal of Minerals & Materials Characterization & Engineering, Vol. 10, No.14, pp.1293-1306, 2011 jmmce.org Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 1293 Effect of Secondary Processing and Nanoscale Reinforcement on the Mechanical Properties of Al-TiC Composites V. Senthilkumar * , A. Balaji, Hafeez Ahamed Department of Production Engineering, National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirrappalli – 620015, India *Corresponding author: vskumar@nitt.edu ABSTRACT Aluminium based composites containing 1, 1.5 and 2wt. % of nano-sized Titanium Carbide particulates (TiC), with an average of 45nm, reinforcement were synthesized using low energy planetary ball mill followed by hot extrusion. Microstructural characterization of the materials revealed uniform distribution of reinforcement, grain refinement and the presence of minimal porosity. Properties characterization revealed that the presence of nano-TiC particulates led to an increase in hardness, elastic modulus, 0.2% yield strength (0.2% offset on a stress-strain curve), and the stress at which a material exhibits a specified permanent deformation, Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) and ductility of pure aluminum. Fractography studies revealed that the fracture of pure aluminum occurred in ductile mode due to the incorporation and uniform distribution of nano-TiC particulates. An attempt is made in the present study to correlate the effect of nano-sized TiC particulates as reinforcement and processing type with the micro structural and tensile properties of aluminum composites. The mechanical properties, namely, the UTS, hardness, grain size and distribution of the reinforcement in the base metal were studied in as sintered and extruded conditions. Orowan strengthening criteria was used to predict the yield strength of Al-TiC composites in the present work and experimental results were compared with the theoretical results. Keywords: Nano-particulates; Aluminum; Tensile properties; Microstructure; Ductility; Orowan strengthening; 1. INTRODUCTION Composites have been considered as an important engineering material for potential applications in various industries from the days of their inception. During the last several decades, extensive research has shown tremendous promise of Metal Matrix Composites (MMCs) and a large number of conventional and innovative fabrication techniques have been developed to engineer composites for a diverse field of applications [1-4]. The most common choices for the matrix of a metal matrix composite have been aluminium, magnesium and titanium. The titanium matrix  1294 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 composites were engineered for a spectrum of performance-critical and high temperature related applications. The aluminum alloy-based MMCs were favorable on account of their low density, wide alloying range, capability and response to heat treatment using the existing infrastructure that is used for the monolithic counterparts, and the intrinsic flexibility and responsiveness to both primary and secondary processing. Matrix strengthening by reinforcing nanosized ceramic particles attracts many researchers as it maintains good ductility, high temperature creep resistance and fatigue properties [5-8]. The ductility and toughness of such MMCs can be significantly improved with simultaneous increase in strength by reducing the particle size to the nanometer range in the so-called Metal Matrix Nanocomposites (MMNCs) [9]. To facilitate the development of MMNCs, it is necessary to develop constitutive relationships that can be used to predict the bulk mechanical properties of MMNCs as a function of the reinforcement, matrix, and processing conditions. In the past few years, some modeling work [10-13] has been done in this regard. Zhang and Chen [14] developed an analytical model for predicting the yield strength of particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites. Yield strength of MMNCs is governed by the size and volume fraction of nanoparticles, the difference in the coefficients of thermal expansion between the matrix and nanoparticles, and the temperature change after processing. The above model indicates that 100 nm is a critical size of nanoparticles to improve the yield strength of MMNCs, below which the yield strength increases remrkably with decreasing particle size. The aim of the present investigation is to synthesize Al–TiC nanocomposites using blend–press– sinter powder metallurgy (PM) technique. Obtained composites were hot extruded and characterized for their microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties. Particular emphasis was placed to study the effect of secondary processing and the presence of nano-sized TiC particulates as reinforcement on the microstructure and mechanical response of commercially pure aluminium matrix. In the present paper, section 2 covers the experimental procedure followed during the primary and secondary stages of processing, density measurement, hardness and microstructural anlaysis. Section 3 details the observation made at microstructural and microstructural levels. Mechanical properties evaluated for the Al-TiC composites and comparison of theoretically predicted yield stress to that of experiments are given in section 3. The conclusions made from the present experimental investigations are given in section 4. 2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES 2.1. Materials In this study, base material was Aluminum powder >99% purity (supplied by Alfa Aesar, Germany) with an average particle size of 28.69 microns. Nano-sized TiC particulates (supplied by Alfa Aesar, Germany) with an average size of 45nm were used as reinforcement. 2.2. Primary Processing  Vol.10, No.14 Effect of Secondary Processing 1295 To obtain the powder mixture, the pure Al and TiC powders were introduced together into an air tight sealed container and the container was placed in a chrome steel jar of a two station Insmart Systems, laboratory scale high energy planetary ball mill operating at a rotational speed of 300 rpm with a mixing time of 90 minutes. The purpose of this step was to mix powders without changing their original characteristics. The conventionally mixed powders were consolidated by cold pressing followed by sintering and hot extrusion. Uniaxial cold-pressing in a cylindrical die was carried out at a pressure of 500MPa, with zinc stearate as the lubricant. The sintering of composite samples were carried out at 550 0 C with a soaking time of 120 min under controlled atmosphere providing Argon gas throughout the process and subjected to furnace cooling. 2.3. Secondary Processing Primary processed materials were subsequently hot extruded at 600 0 C employing an extrusion ratio of 14.06:1. Molybdenum Disulphide was used as lubricant. 2.4. Density Density of green compacts, as sintered specimens and polished extruded materials, was determined using Archimedes principle [15, 16, 17]. Distilled water was used as the immersion fluid. Three polished samples randomly selected from each as sintered and extruded composite formulation were weighed in air and then immersed in distilled water, using an electronic balance with an accuracy of ±0.1mg. 2.5. Microstructural Characterization Microstructural characterization studies were conducted on metallographically polished sintered and extruded samples to investigate grain characteristics, reinforcement distribution and interfacial integrity between the matrix and reinforcement using Hitachi S4100 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). 2.6. X-ray Diffraction X-ray diffraction analysis was carried out on the polished samples of Al-TiC composites in as extruded conditions using automated Rigaku Ultima III XRD. The samples were exposed to Cu K radiation (k = 1.54056A˚) at a scanning speed of 2 0 min -1 . The Bragg angle and the values of the interplanar spacing‘d’ obtained were subsequently matched with the standard values of Al, TiC and other related phases. 2.7. Hardness Macro hardness measurements were made on the polished samples of Al/TiC samples in extruded and sintered conditions. The Vickers microhardness of the composite samples has been measured using a load of 25 g for 10 s. At least five measurements of microhardness were performed on each sample. 2.8. Tensile Properties  1296 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 The smooth bar tensile properties of the extruded samples were determined in accordance with ASTM test method E8M-01 using FIE 100Tons Universal Testing machine on round tension test specimens of 6mm diameter and 24mm gauge length. Fractography was done on the fractured surface of tensile specimens using a Hitachi S4100 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 3.1 Macrostructural Characteristics Macrostructural characterization conducted on the as sintered billets of Al-TiC composites revealed the absence of macrostructural defects such as circumferential or radial cracks as shown in the low magnification images of Fig. 1. Following extrusion, no observable macro defects were observed on Aluminium nanocomposites of varying TiC percentage. The outer surface was smooth and free of circumferential cracks. Fig. 1 Macrograph of Al-TiC nanocomposites (a) as extruded (b) as sintered conditions 3.2 Microstructural Characteristics Microstructural studies of composite specimens showed uniform distribution of reinforcing particles with good reinforcement–matrix interfacial integrity and significant grain refinement. Observation also revealed minimal presence of porosity in the materials. Fig. 2(a) shows the SEM micrograph of initial Aluminium powder particles. The SEM micrographs of a single aluminium powder particle exhibiting the individual grain is shown in Fig. 2(b). The distribution of Al particles, as in the received condition, is shown in Fig. 2(c). It was found that the average particle size is 28.69 m with uniform distribution of particles. The SEM micrograph of as received nanoceramic TiC particles is shown in Fig. 2(d) in clustered form. The shape of the TiC particle is found to be irregular in nature. Fig. 3 shows the SEM micrograph of Al-2.0(wt)%TiC composite sample after hot extrusion. Visible micro cracks can also be seen in the above picture. Reduction in grain size of aluminum matrix due to secondary processing can be attributed to the  Vol.10, No.14 Effect of Secondary Processing 1297 coupled effects of (i) capability of nano-ceramic particulates to nucleate Aluminum grains during recrystallization and (ii) restricted growth of recrystallized aluminum grains as a result of pinning by nano- ceramic particulates [17, 18]. Fig. 2 (a) SEM micrograph of Al particle (b) SEM micrograph of single Al particle (c) Particle size distribution of as received Al particles (d) SEM micrograph of TiC nano- particle. The reasonably uniform distribution of reinforcement particulates, as shown in Fig.2, can be attributed to suitable blending parameters, such as speed of the jar and blending time and the high extrusion ratio used in secondary processing. In theory, uniform distribution of particulates can be obtained when larger deformation is applied irrespective of size difference between the reinforcement particle and matrix powder [18]. The grain size of initial aluminum powder is fine and is found to be 320 nm and the single grain of a particle, as shown in circle, is Fig. 2(b). XRD analysis on the as sintered and as extruded samples, as shown in Fig. 4, revealed the absence of any intermetallic and reaction phase in the composites. The inset figure shows the peak broadening effect of secondary processing (extrusion) which exhibits the reduction in grain size. The diffraction patterns of the Al-TiC composites analyzed exhibited various peaks corresponding to the face centered cubic (FCC) phase of Al. Al peaks and TiC peaks were indexed using JCPDS file numbers 04-0787 and 02-0942 respectively. Williamson and Hall [19]  1298 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 proposed a method of deconvoluting size and strain broadening by looking at the peak width as a function of diffracting angle 2θ and the instrumental corrected broadening, , corresponding to the diffraction peak of Al was estimated using the following equation: Fig. 3 FESEM micrograph of Al-1.0(Vol) %TiC composite after extrusion. (1) where K is the shape factor (0.9), is the X-ray wavelength (1.5406Å), is the Bragg angle and is the effective crystallite size normal to the reflecting planes and is the lattice strain. The instrumental corrected broadening, , was approximated as a full width at half-maximum (FWHM) by Gaussian fit, which was calculated by using X-Ray Diffraction Analysis software based on each diffracting angle of 2θ. The first four Al reflecting planes (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0), (2 2 2) were used to construct a linear plot of as a function of , the crystallite size ‘t’ may be estimated from the intersection with the vertical axis and the lattice strain from the slope of the line [19]. Grain refinement of Al-TiC nanocomposites in as extruded state is provided in Table 1. As discussed in this section in 3.2 thermo-mechanical processing (extrusion) of sintered samples resulted in the formation of fine grain sizes and pinning of aluminium grains. The presence of minimal porosity in composite materials supported by the experimental density values can be attributed to good compatibility between Al and TiC and the use of an appropriate selection of compaction, sintering and extrusion parameters.  Vol.10, No.14 Effect of Secondary Processing 1299 Fig.4 XRD pattern of Al-TiC composites in as sintered and as extrude conditions Table1 Results of density and grain size characteristics Density (g/cc) System Volume Theoretical experimental Porosity(%) Grain size after extrusion(microns) Al- 1.0TiC 0.55 2.7329 2.73 0.06 0.22 Al- 1.5TiC 0.837 2.74435 2.74 0.075 0.18 Al- 2.0TiC 1.12 2.7558 2.75 0.085 0.16 3.3 Mechanical Characteristics The results of mechanical characterization (hardness and tensile properties) revealed that significant contribution of nano-TiC reinforcement in improving the overall mechanical performance of Aluminum. Ductile fracture behavior of the matrix was observed. 3.3.1 Hardness The results of micro hardness measurements, as provided in Table 2, revealed the presence of nano-TiC reinforcement led to a significant increase in macro and micro hardness of Aluminum  1300 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 nanocomposites. This can be attributed primarily to the presence of relatively harder ceramic titanium carbide particulates in the matrix, their strong resistance on the soft aluminium matrix for any indentation, and finally a reduced grain size. Table 2: Results of room temperature mechanical properties System Macro Hardness (15 HRT) Micro Hardness (HV) %Elongation Yield Strength (MPa) E (GPa) UTS (MPa) Al-1.0 TiC 65 34 25 132 78 155 Al-1.5 TiC 68 37 30 148 88 168 Al-2.0 TiC 71 45 33 159 95 190 Al1100/10% (vol)/Extruded[21] - 20 75 96 114 3.3.2 Tensile properties Room temperature tensile test revealed simultaneous improvement in 0.2 Yield strength (YS), Ultimate Tensile Strength (UTS) and percentage elongation of aluminium nanocomposites of varying percentages of TiC reinforcement. The fractography analysis on various aluminium based nanocomposites shown in Figures 5(a) – 5(c) exhibit ductile mode of fracture with dimples and voids. Among the different aluminium nanocomposites, Al-1.0(vol) TiC exhibits better results compared with other system of composites in the present experimental investigation. Significant increase in 0.2% YS and UTS of pure Aluminum, due to the presence of nano-TiC as reinforcement can primarily be attributed to the coupled effect of multi-directional thermal stress due to the generation of dislocation at the TiC/Al interface as an effect of the large mismatch in coefficient of thermal expansion between matrix and reinforcement, the effective transfer of applied tensile load to the uniformly distributed enormous number of well bonded strong TiC particle, one of the hardest refractory metal carbide with a Vickers hardness of 19.6– 31.4 GPa [20], and the grain refinement. It may be noted that strengthening effect of nano-size particulates will be higher as an increase in dislocation density; with the further decrease in particulate size for a constant volume fraction of reinforcement will be much higher and is well established. In general, the yield stress of material is the stress required to operate dislocation sources and is governed by the presence and magnitude of all the obstacles that restrict the motion of dislocation in the matrix. Multi-directional thermal stress induced during processing easily starts multi-gliding system under applied stress so that dislocations were found developing and moving in several directions [21]. Multi-glide planes agglomerate under thermal and/or applied tensile stress to form grain boundary ledges. As the applied tensile load increases, these ledges act as obstacle to dislocation movement resulting in pile-ups and lead to the significant increase in the yield strength of the composites over pure Aluminum. Increasing pile up of dislocation at the grain boundary ledges creates stress concentration which cause yielding of the ledges with an avalanche of grain boundary sliding under increasing applied stress and cause the ductile failure of the composites with a result of tremendous increment (50%) in ductility of  Vol.10, No.14 Effect of Secondary Processing 1301 Al/TiC composite when compared to that of Aluminum micro composite with 10%(vol) SiC reinforcement [22]. Finer grain size might be the additional force behind increment of the ductility. Improvement in ductility of Aluminum alloys exploiting very fine thermally unstable secondary phase precipitation at grain boundaries has been well established. Presence of particulates clusters at grain boundary might lead to early grain boundary cavitations and eventually end up with relatively low ductility. The results also revealed that addition of 2.0wt% of nano-size TiC lead to an improvement in overall combination of mechanical properties. Fig. 5(a) SEM fractograph of Al-1.0(wt) %TiC (b) Al-1.5(wt)%TiC (c) Al- 2.0(wt)%TiC 3.3.3 Prediction and comparison of Orowan theoretical yield stress with experimental results The increase in tensile strength can be attributed to the coupled effects of Orowan strengthening [23], grain refinement, the formation of internal thermal stress due to different Co-efficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) values between the matrix and the reinforcement particles (26.49 X 10 -6 K -1 for Al and 8X 10 -6 K -1 for TiC), effective load transfer between the matrix and the reinforcement and the hardening due to the strain misfit between the reinforcing particulates and the matrix. The contributions to the increase in the YS of the composites by various strengthening mechanisms could be taken as a simple summation or the root of the sum of squares of the different mechanisms which have been discussed in several recent studies [23].  1302 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 Orowan strengthening caused by the resistance of closely spaced hard particles to the passing of dislocations is important in aluminum alloys. However, that Orowan strengthening is not significant in the micro sized particulate-reinforced MMCs, because the reinforcement particles are coarse and the interparticle spacing is large. Furthermore, since the reinforcement is often found to lie on the grain boundaries of the matrix, it is unclear whether the Orowan mechanism can operate at all under these circumstances. For melt processed MMCs with the usually-used particles of 5 nm or larger, Orowan strengthening has indeed been pointed out to be not a major factor [23]. In contrast, due to the presence of highly-dispersed nanosized reinforcement particles (smaller than 100 nm) in a metal matrix, Orowan strengthening becomes more favourable in MMNCs. It has been well established that the presence of a dispersion of fine (100 nm) insoluble particles in a metal can considerably raise the creep resistance, even for only a small volume fraction (<1%), due to the fact that Orowan bowing is necessary for dislocations to bypass the particles. For composites containing fine particles, strengthening is often explained by the Orowan mechanism [23, 24]. It is noted that thermal stresses around the nanoparticles are large enough to cause plastic deformation in the matrix and dislocation loops around the vicinity of the nanoparticles. In addition, secondary processing, such as extrusion, is used to synthesize MMNCs. It is clear that plastic deformation has occurred during synthesis of MMNCs and Orowan loops are expected to exert a back stress on dislocation sources. Therefore, it is necessary to take into consideration the Orowan strengthening in the modeling of MMNCs. With the help of the following equations yield stress can be calculated. As stated above, for MMNCs Orowan strengthening mechanism should be taken into consideration. When several strengthening effects are simultaneously present, one way would be to use the rules of addition of the strengthening contributions, e.g., by Lilholt [25]. Thus, the yield strength of particulate-reinforced MMNCs, σ yc was expressed as follows [14] considering Ramakrishnan [26] approach which combines additive and synergistic effect of strengthening mechanisms: )1)(1)(1( 1Orowandymyc fff +++= σσ (2) where Orowan f is the improvement factor associated with Orowan strengthening of the nanoparticles. For particulate-reinforced composites the general expression for 1 f is p Vf 5.0 1 = (3) where p V is the volume fraction of the reinforcement nanoparticles. d f has been expressed as ymmd bkGf σρ /= (4) where m G is the shear modulus of the matrix, b is the Burgers vector of the matrix, k is a constant, approximately equal to 1.25, ρ is the enhanced dislocation density which is assumed  Vol.10, No.14 Effect of Secondary Processing 1303 to be entirely due to the residual plastic strain developed due to the difference in the coefficients of thermal expansion (DCTE) between the reinforcement phase and the matrix during the post- fabrication cooling. For equiaxed particulates the following expression was reported ( ) { ( ) } )1(/12 ppp VbdTV −∆∆= αρ (5) where p d is the particle size, α ∆ is the difference in the coefficients of the thermal expansion, T ∆ is the difference between the processing and test temperatures. The improvement factor related to the Orowan strengthening of nanoparticles introduced in Eq. (2) can be expressed as, ymOrowanOrowan f σσ /∆= (6) where Orowan σ ∆ has been described by the Orowan–Ashby equation b r bG m Orowan ln 13.0 λ σ =∆ (7) Considering T ∆ =)( testprocess TT−, α ∆ = pm αα −, one can derive the following equation for the yield strength of MMNCs ))(5.01( ym ympyc AB BAV σ σσ ++++= (8) )1( ))((12 25.1 pp ppmtestprocess m Vbd VTT bGA− −− = αα (8a) b d V d bG B p p p m 2 ln 1) 2 1 ( 13.0 3 1 − = (8b) Table 3 Theoretically predicted yield strength values for different composites System(weight percentage) Volume fraction (%) Yield strength, MPa (Orowan criterion) Al-1.0 TiC 0.55 137.65 Al-1.5 TiC 0.837 152.93 Al-2.0 TiC 1.12 165.78  1304 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 Table 3 presents the analytical results of the effect of the volume fraction ( p V) on the yield strength based on Eq. (8) for different volume fraction of nanoparticulates ( p V). The following data were used for calculating the theoretical yield strength of the composites: ym σ = 97 MPa, m G = m E/[2(1 + ν )] = 25.4 GPa, b= 0.286 nm, m α = 0.000025 ( 0 C) -1 , p α = 0.000007 ( 0 C) -1 , T process = 300 0 C, T test = 30 0 C, Good agreement between the present model prediction, based on Eq. (8), and the experimental data has been observed and shown in Fig. 6. It has been also observed that the model proposed by Zhang and Chen [14] can be effectively used for predicting the yield strength of the aluminium based nanocomposites. A small amount of error between the thereortical model and the experimental value was found in the present investigation. The overestimation of results is due to the assumption made in the formulation of equation with regards to the shape of the nano particles which is spherical in the present case. However, the TiC nanoparticles assume irregular shape which can be seen in the Fig. 2(d). The orowan model predicted a better result with an error of 4% in the case of higher volume fraction (1.0%) exhibiting better mechanical properties. Fig. 6 Comparison of theoretically predicted yield strength with experimental results for varying percentage of TiC reinforcement (Wt%.)  Vol.10, No.14 Effect of Secondary Processing 1305 4. CONCLUSION 1. Powder metallurgy route has been successfully employed to produce aluminium based nanocomposites reinforced with titanium carbide. 2. Hot extrusion of sintered aluminium nano composites resulted in enhanced yield strength by more than two times that of pure aluminium - 10% micron sized Al 2 O 3 reinforcement, ultimate tensile strength by 66.5%, percentage elongation by 50%, due to homogeneous distribution of nanoparticles and reduction in porosity. 3. Addition of nanoparticles into the aluminium matrix increases the mechanical properties of the synthesized nanocomposites. 4. The experimentally determined yield strength values of different Al-TiC composites were evaluated with theoretical model (orowan model). 5. The theoretical model used in the present investigation is in good agreement with the experimental data obtained from the present investigation, with a very minimum error of 4- 5%, indicating that it is necessary to consider Orowan strengthening in MMNCs. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge Department of Science and Technology/ Government of India for supporting this research under project SR/FTP/ETA-69/07. REFERENCES [1] J. M. Torralba, C. E. da Costa, F. Velasco, P/M aluminum matrix composites: an overview, J. Mater. Process. Technol., 133, 203-206 (2003). [2] G. Abouelmagd, A.M. Abd El-Mageed, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Measurement and Control of Granular Materials, XI AN China, 69–76 (2000). [3] K. Tokaji, H. Shiota and K. Kobayashi, Effect of particle size on fatigue behaviour in SiC particulate-reinforced aluminium alloy composites, Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 22, 281–288 (1999). [4] S.J. Zhu, L.M. Peng, Q. Zhou, Z.Y. Ma, K. Kucharova and J. Cadek, Creep behaviour of aluminium strengthened by fine aluminium particles and reinforced by silicon carbide particulates DS Al–SiC/Al 4 C 3 composites, Mater. Sci. Eng. A , 268, 236–245 (1999). [5] Hassan SF, Gupta M. Development of high strength magnesium copper based hybrid composites with enhanced tensile properties, Mater. Sci. Technol,19, 253–259 (2003). [6] S.F. Hassan and M. Gupta, Development of high strength magnesium copper based hybrid composites with enhanced tensile properties, Composite Structures, 72, 19–26 (2006). [7] T. Laha, Y. Chen, D. Lahiri, A. Agarwal, Tensile properties of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum nanocomposite fabricated by plasma spray forming, Compos. A 40 589-594, (2009). [8] A. Santos-Beltrán, V. Gallegos-Orozco, R. Goytia Reyes, M. Miki-Yoshida, I. Estrada- Guel, R. Martínez-Sánchez, Mechanical and microstructural characterization of dispersion strengthened Al–C system nanocomposites , J. Alloys Compd., 489, 626-630, 2010. [9] I. Montealegre Melendez, E. Neubauer, P. Angerer, H. Danninger, J.M. Torralba, Influence of Nano-Reinforcements on the Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Titanium  1306 V. Senthilkumar, A. Balaji Vol.10, No.14 Matrix Composites, Composites Science and Technology, Accepted Manuscript Available online (2011). [10] Zhang and Chen, Contribution of Orowan strengthening effect in particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites, J. Mater. Sci. 29, 141–50, 1994. [11] He L, Allard LF, Ma E., Fe-Cu two-phase nanocomposites: application of a Modified rule of mixtures, Scripta Mater. 42, 517–23, 2000 [12] Holtz RL, Provenzano V., Bounds on the strength of a Model nanocomposite, Nanostruct . Mater. 8 , 289–300 (1997). [13] Lurie S, Belov P, Volkov-Bogorodsky D, Tuchkova N., Nanomechanical modeling of the nanostructures and dispersed composites, Comput. Mater. Sci. 28, 529–539 (2003). [14] Zhang and Chen, Consideration of Orowan strengthening effect in particulate-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites: A model for predicting their yield strength, Scr. Mater. 54, 1321–1326 (2006). [15] Gupta M, Lai MO, Saravanaranganathan D, Synthesis, microstructure and properties characterization of disintegrated melt deposited Mg/SiC composites, J. Mater. Sci. 35, 2155- 2165 (2000). [16] Y. Liu, L.F. Chen, H.P. Tang, C.T. Liu, B. Liu, B.Y. Huang,Design of powder metallurgy titanium alloys and composites, Mater. Sci. Eng. A, 418, 25-35 (2006) . [17] Hassan SF, Gupta M, Development of high strength magnesium based composites using elemental nickel particulates as reinforcement, J. Mater. Sci. 37, 2467–2474 ( 2002). [18] Tan MJ, Zhang X, Powder Metal Matrix Composites: Selection and Processing, Mater. Sci. Eng. A 244, 80–85 (1998). [19] K. Williamson, W.H. Hall, X-ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram, Acta. Metall., 1, 22–31 (1953). [20] E.K. Storms, The Refractory carbides, Academic Press, New York, p. 11 (1967). [21]Murr LE. Interfacial phenomena in metals and alloys. MA, USA: Addison-Wesley (1975). [22] B.V.R.Bhatt, Y.R.Mahajan, H.M.D.Roshan and Y.V.R.K.Prasad, Processing maps and hot- working of powder metallurgy 1100 Al-10 vol % SiC-particulate metal-matrix composite, J.Mater.Sci. 27, 2141-2147 (1992). [23] Hazzledine PM, Direct versus indirect dispersion hardening, Scripta Metall. Mater. 26, 57–58 (1992). [24] Huang H, Bush MB, Fisher GV, A Numerical Study of Effect of Grain Boundaries on Elastic and Plastic Properties in Nanocomposite Materials, Key Eng Mater. 127–31, 1191– 1198 (1997). [25] Lilholt H. In: in: Proc of the 4th Riso Int. Symp. on Metall. Mater. Sci. Denmark, Roskilde: Riso National Laboratory; 381–392 (1983). [26] Ramakrishnan N, An analytical study on strengthening of particulate reinforced metal matrix composites Acta Mater. 44, 69–77 (1996). |