Technology and Investment

Vol.1 No.2(2010), Article ID:1758,12 pages DOI:10.4236/ti.2010.12010

Strategic Orientations: Multiple Ways for Implementing Sustainable Performance

Van Linden van den Heuvellsingel 7, Vlaardingen, Netherlands

E-mail: marcel@vanmarrewijk.nl

Received October 26, 2009; revised December 28, 2009; accepted December 28, 2009

Keywords: Spiral Dynamics, Four Phase Model, Hardjono, Flexibility, Creativity, Effectiveness, Efficiency, Sustainability Scan, CSR, Corporate Sustainability

Abstract

The Four Phase Model®, created by prof. dr. Teun W. Hardjono [1] in 1995, distinguishes four ideal type strategic orientations and shows that these strategies brighten and dim in a specific sequence, adding the most required competences to the organization, and creating a natural rhythm to corporate dynamics. By applying this theory one can understand the nature and whereabouts of the organization’s systemic constraints, revealing the basic features for creating a roadmap towards sustainable performance improvement and competence development. The model generates the top priorities, selects the most adequate (ideal type) interventions and key performance indicators. Combining strategic “situations” as indicated by the Four Phase Model and phase-wise “contexts” as introduced by Spiral Dynamics [2], provides a conceptual synergy with four innovative outcomes: Firstly, aligned with specific contexts, the strategic interventions and KPI’s can be made more specific and practical, thus creating a roadmap for performance improvement and organizational development. Secondly, it structures change management into four distinctive hierarchical complexity levels: 1) enhancing fundamental skills, structures and procedures (vitalizing); 2) improving contemporary levels, aligned with the dominant value system (optimizing); 3) new re-orientations while continuing within current systems (shifting) and 4) a transformation to a more complex context or emerging value system (transforming). Thirdly, powered with the combined understanding of above concepts, one can deduct the specific context and situation for each intervention, instrument or approach to be applied effectively. Fourthly, the combination provided the bases for the so-called Strategy Scan and Strategic Sustainability Scan.

1. Introduction

The rising public expectations, the increasing social and environmental problems both locally and globally and the continuous strive for quality improvements and innovations are challenging corporations to choose new ambitions and aspire for higher performance levels with respect to corporate sustainability. They need to chart a course with respect to corporate sustainability and responsibility (CS/CR) within an increasing complex and dynamic environment.

In other publications, Van Marrewijk [3,4] presented a set of definitions of CS/CR differentiated for various development phases (or contexts, or levels of existence). Companies can initiate activities or approaches supporting sustainability, which aligns their institutional structure, values systems and ambition levels. True, traditional capitalist structures hardly enhance sustainable development, but these first small steps are essential in – eventually-moving into a worldwide transition towards structures which support a sustainable way of living, working, producing and consuming.

The more corporations recognize that CS/CR activities might increase their success, support their branding and reduce theirs risks, the more they will invest in these activities. Stated in another “worldview”: the more companies accept their role in contributing to solving societal problems, to bridging the gaps between rich and poor and stop environmental degradation which are jeopardizing ecosystems, the more companies will create new product concepts and processes which include improvements to all objectives, for people, planet and profits. [5]

Each company needs to position itself within the CS/CR debate. What definition aligns their context and situation best? Which CS activities-among the numerous CS-initiatives already taken-make sense with respect to their fundamental objectives? What rate of progress do they need to take in order to stay ahead of competition? In the Journal of Business Ethics, Van Marrewijk and Hardjono [6] listed a set of the basic questions that stemmed from their SqEME approach: What does the organization want? Who are allowed to take part in this decision process? Which factors will influence the new ambitions? Which actions are most effective? And how can the espoused progress be measured and shown to the stakeholders?

This paper can support companies formulating strategies towards implementing corporate sustainability and responsibility by introducing the factors that influence the most adequate strategic orientation and the factors that indicate the developmental level at which companies need to act. Combining these outcomes will result in a sequence of strategic steps, which are placed in a context aligning the organization’ value systems and institutional structures. Depending the company’s ambition, the sequence of strategic steps can lead to performance improvement, a shift to new corporate orientations or set out a transition to new ways of doing business in a more sustainable way.

Paragraph two summarizes the Four Phase Model®, created in 1995 by Dr. Teun W. Hardjono, professor on Quality Management at the Erasmus University Rotterdam [1]. Paragraph three focuses on the integration of the Four Phase Model and Spiral Dynamics [2], combining the two dimensions mentioned above. Paragraph four will briefly summarize the possible sustainability interventions that can be implemented at different combinations. Paragraph five elaborates on the consequences with regard to corporate dynamics and the final chapter introduces an online strategy scan which is able to support a strategic dialogue.

2. Four Phase Model

Teun W. Hardjono presented his Four Phase Model® as a PhD thesis in 1995 [1], capturing 20 years of experiences in corporate strategy and organizational change as a senior consultant at one of the Netherlands’ most renowned management consultancies. In practice, the Four Phase Model® has appeared an effective model for managers and management consultants to analyze the present state of organizations and to determine the most likely strategy to further improve their organizations. The model structures various organizational performance indicators and possible interventions and is able to provide guidelines for a program of organizational change.

2.1. Core Assets

The Four Phase Model’s basic assumption is the recognition that organizations are striving to increase the sum of four essential assets, in a continuous process of exchanging one asset for another. These assets relate to basic organizational competences. These assets/competences are the:

o Material asset: the ability to increase, maintain and optimally utilize the tangible resources of an organization. Its worth is reflected-more or less-in the balance sheet.

o Commercial asset: the ability to have access to and to act on markets and the skills to execute commercial transactions.

o Socialization asset: the ability to inspire people and create supporting structures in order to achieve the common, corporate objectives.

o Intellectual asset: the learning capability of organizations, the ability to (pro-actively) adapt to changing circumstances and the creative capacity, which is based on the collective intellect and creativity of the members of organizations.

These core assets or basic competences also relate psychologically to the core drivers and professional ambitions of people and therefore also organizations. See Table 1.

Employees bring their best talents, skills, relationships and personality to the workplace and in return expect fair rewards, not only in financial terms, but also career opportunities, chances to grow their professional skills, challenging tasks to boost their experience, et cetera. Companies could make use of the relationships between corporate and personal drivers by for instance linking their reward schemes and employees’ personal developments plans in line with their core strategies. But first, lets elaborate some more on the core assets.

Tabel 1. Basic assets at organizational and individual level (Hardjono), [1].

Maximizing, for instance, the material assets at the expense of the other assets will ultimately lead to poor results. It is a myth that doing business is only focused at making profits. We all know what happened when a business unit manager shows double-digit growth figures, shortly after the CEO passionately requested for performance improvement on the shortest term possible. Having stripped research and development, postponed marketing campaigns, cut back conference trips and training possibilities, cancelled the annual day out while demanding overtime from his workers producing stocks, of course his financial figures improved. Soon his unit will be in dismay and he ought to be fired for that.

Healthy, sustainable organizations have learned to optimize the mix of the four essential competences: the abilities to create wealth, engage in transactions, enhance employee commitment, dedication and trust and the ability to adapt or proactively respond to changing circumstances.

Creating an optimal mix of the assets, companies exchange one asset for the other; For instance, invest money/ material assets for increasing the company’s commercial abilities. As long as the marginal revenues exceed the marginal costs, companies will invest in enhancing their assets in order to meet their corporate objectives. In creating an optimal mix, the organization is gaining more ability to protect and improve its future.

For creating an optimal mix of basic assets, organizations need adequate strategies. The following questions are relevant: What is the constraint in increasing corporate performance? What single factor will impact performance improvement most? What extra competences should be prioritized? What is the organization’s greatest risk? What kind of needs do our customers have? What are the needs of the other stakeholders? Is our organization fit to meet these requests? Although these questions seem to have different natures, the answers tend to come together nicely, as abundant case studies based upon the Four Phase Model have shown.

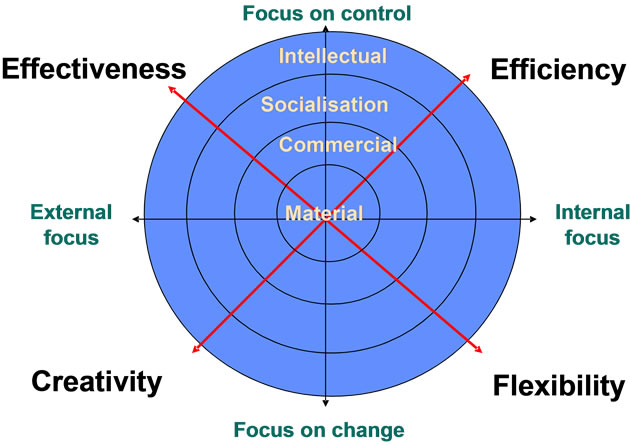

The Four Phase Model suggests organizations to focus on either internal or external issues and-at the same timefocus on control or change. Both pairs are dichotomies: although each side of these dichotomies are relevant, in a specific situation only one site contains the whereabouts of the constraint (inside or outside) or the key to the solution (via control or allowing change). The result can be presented in a so-called Harvard Diagram, presented in Figure 1. The diagram shows four concentric circles, representing the core assets, the diagram, representing the basic dichotomies, and the resulting four ideal type strategies, or strategic orientations.

These strategic orientations are:

· Effectiveness: A market-driven orientation which is directed towards increasing the effectiveness of an organization;

· Efficiency: A productivity orientation in order to enhance the efficiency of an organization;

· Flexibility: A people oriented strategy to increase the flexibility of an organization;

· Creativity: An innovation (and adaptedness)-driven orientation in order to increase the creativity of an organization.

Each strategic orientation contributes to all assets, but enhances one basic competence in particular. Effectiveness primarily boosts the commercial abilities; Efficiency focuses mainly on increasing the material assets; a strategy aimed at Flexibility has its most impact on the socialization competence and Creativity improves the intellectual capacity and the company’s adaptedness to changes in the environment.

The next paragraph will elaborate on the basic interventions, structured according the Four Phase Model.

2.2. The Basic Orientations

Ideal type interventions can be plotted in the basic graph of the Four Phase Model: four assets, four quadrants (result areas) and two dichotomies (orientations) makes 32 interventions.

We will now demonstrate the Effectiveness Quadrant, (top left) in Table 2:

Figure 1. The core assets, dichotomies, and strategic orientations (source: T.W. Hardjono) [1].

Table 2. The Effectiveness Quadrant (Hardjono) [1].

It reads as follows:

· Production, or adding value in general, generates products and services. These are positively appreciated on the balance sheets, but once sold to customers it delivers a cash flow and, given its cost structure, it might be profitable.

· By carefully planning and organizing marketing, sales, supply chain and distribution, thus generating supply and demand, and competing on the market, resulting in a specific market share.

· By structuring the organisation and setting targets to all employees, organisations proved a sense of direction and a specific customer orientation. Employees engage into social networks thus stimulating the organisation’s effectiveness.

· By anticipating and grasping the changing life conditions and societal circumstances, generating intelligence and understanding which will be used as inputs in new plans.

The appendix includes the full matrix of ideal type interventions.

The items in the overview are fairly basic-no rocket science here-stocks turn to revenues, to cash flow, to profits etcetera. It is the elegancy of the model providing a coherent image of complex organisations summarized in 32 activities. The model needed a fourth layer to acquire a level of sophistication in order to better meet the complexity of real life. Having defined the four basic assets, the diagram with the four quadrants based on the two dichotomies, and the four strategic orientations, the fourth level is formed by the various aspects of dynamics, which brought a specific sequence and rhythm to the model.

3. The Dynamics of the Four Phase Model

3.1. Balancing Reverse Effects

The model offers a few arguments that bring balance, sequence and rhythm to the model. The first one introduced here is “too much of anything will inevitably have a reverse effect”. Too much Efficiency results in a rigid bureaucratic organisation. Too much focus on Change and Flexibility will end up in chaos and anarchy. Too much room for Creativity leads to amateurism and too much focus on the market Effectiveness causes an oversensitive, segregated organisation.

One may conclude that balance needs a temporarily focus, as a continuous focus ultimately results in adverse effects. Figure 2 could therefore be read as follows: “Our main focus is on Efficiency, there we can make our biggest impact on our organisation and achieve our goals, but in order to prevent our largest risk to occur— rigidness and bureaucratic tendencies—management must already prepare the roads for our next strategy and focus on Flexibility.”

To prevent reverse effects to happen, organizations should turn to the “next” strategy that happens to include the competency that can prevent this effect to occur. More Flexibility will lift the fear for bureaucracies and Effectiveness soon turns hobbyism into successful marketing and sales campaigns. Taken from a risk perspective, having invested in improving creativity the largest risk is developing new products the market doesn’t want. Having successfully boosted marketing and sales, the organization needs to improve corporate efficiency to see to it that gained market shares leads to profits. Efficiency activities can turn organizations into control-driven bureaucracies and “lean and mean” entities that have lost employees’ commitment to give something extra at customers’ requests. Having successfully created supporting structures and gained employees’ dedication and trust, companies intend to expect creative and adaptive achievements, which ought to meet the customers’ perceptions, etcetera.

3.2. Prioritising Interventions

A second argument supporting balance is the fact that all four quadrants, and all 32 basic interventions are important, but not at the same time. Suppose an organisation has a focus internally and a focus on control, as Figure 2 presents. Its strategic orientation is thus aimed at Efficiency. The more impact-in both time, efforts and means-is spend on this strategy the more powers are building up on the other end of the dichotomies. Reverse effects will occur, forcing the system to move on to the next strategy.

A metaphor can explain this in more detail: a top indoor cyclist engaged in a sprint duel can be forced to a stand still—sur place—as he does not want to take lead position. In cycling this is a strategic option. It takes great skills to remain on one spot, but he cannot stay

Figure 2. Dynamics of the Four Phase Model© (Hardjono) [1].

there forever. Inevitably, in order to prevent from tumbling when his skills are fading or when his adversary was finally forced to take the lead, he moves his cycle downward while building up speed, heading for the finish line.

The next quadrant represents the organisation’s greatest challenge. For instance: Becoming more efficient while maintaining flexibility. If you fail, the organisation turns rigid and bureaucratic. Or, creating innovations, which promise a boost in sales. Without this market orientation creativity might lead to hobbyism. Figure 2 therefore shows a “wake up”, a position currently out of focus, but it needs extra attention in the near future to prevent large risks to occur.

As said before, all interventions are relevant but-strategically-not at the same time. Ideally, half the number of basic interventions can be adequately addressed. As Figure 2 shows, “half” does not represent just two quadrants: the intellectual asset moves ahead, as represented in the outer circle, creating a yin-yang shape. In total 16 interventions are relevant. The dark shades in Figure 2: Three times four interventions aligned with internal focus, Efficiency and focus on control, three lagging interventions on Effectiveness (material, commercial and socialisation) and a leading one on Flexibility (intellectual). In the shaded area there are no conflicting interventions.

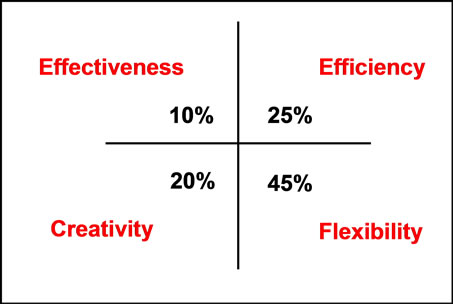

In conducting surveys among clients, we have often applied this model while structuring the employee answers to open questions such as “what can be improved in order to become a great place to work or a high performance organisation”. All employee arguments can be counted and represented in Figure 3. Collectively employees suggest to focus internally and especially on Flexibility. The best suggestion however would be to focus first on Efficiency and implement all improvement that will have impact within short notice. Then move on to focus on Flexibility. After a while management should start preparing the issues in Creativity that needs (strategic) attention.

3.3. System Constraints

Implementing strategic interventions covered in the dark

Figure 3. Results of an empirical analyses on employee arguments by Van Marrewijk

shape is supposed to enhance the necessary competences and ultimately contribute to obtaining the espoused performance results. The “yin-yang” shape indicates a dynamic process. Indeed, the Four Phase Model is a dynamic model suggesting a specific rhythm of shifting from one strategic orientation to the next, adding, each time, new improvements and competences. Ahead always lie new objectives to be met and new competences to be gained. The previous section discussed strategic risk management, with the organisation’s largest challenge represented in the next phase or quadrant, and reverse effects that occur when organisations become rigid. Trying to prevent them to occur was presented as the first factor that causes dynamic effects within organisations.

This paragraph will elaborate on the system constraint, the organisation’s bottleneck in improving corporate performance. Eli Goldratt elegantly proved in ‘the Goal’ (1984), his introduction to his Theory of Constraints, that in the end one factor obstructs the performance of an entire system. The investments that are able to lift this constraint by improving its quality or capacity will yield the highest productivity. The question is: where lies the constraint? On what factor should we target?

In terms of the Four Phase Model: 1) The constraint lies internally or externally and 2) the competences needed to lift the constraint are the material, commercial, socialisation or intellectual assets. In a strategic dialoguewithin the board of directors, among experts, deep within the organisation or with various stakeholders-one must find out the whereabouts of the constraint. The following strategic issues might deliver the final clue:

Customer profile Strategies developed with the Four Phase model apply to product/market combinations. Therefore market saturation levels, customer profiles, rate of progress et cetera are highly relevant. Our model distinguishes four ideal type profiles for customer needs. The organisation should focus on:

• Latent needs of customers. Surprise them with new, innovative products and services that where unheard off but are recognizes has attractive (Creativity).

• The customer must choose among a wide range of products, he does not fully comprehend. The traditional portfolio of marketing techniques is developed for this type of customer needs (Effectiveness).

• The customer is fully aware of all alternatives and seeks the lowest price (Efficiency).

• The customer is sensitive for the quality of services, which requires a flexible approach of the organisation (Flexibility).

Each specific customer profile can be serviced best by one of the strategic orientations mentioned between brackets. Customer needs can change over time, forcing the organisation to respond likewise. In many maturity models and life cycle approaches one can observe a sequence of these consumer types.

Although important, the strategic orientation will be influenced by more aspects than customer profile alone. We will provide an extra example:

Major risk What is the major risk of your organisation?

· We have to prevent growing into an over-bureaucratic, inert organisation, no longer able to respond adequately to customer needs for dedicated services.

· Myopia due to conflicting kingdoms existing in the organisation, and the unbalance between customer focus and cost control might bring us in jeopardy.

· In offering ample room and insufficient focus, our employees invest too much time in their hobby’s and personal interests.

· Our continuous attention for employee needs might turn into informalities and anarchy. Further more our service oriented, customer friendliness attitude might cost more than it generates.

Suppose the first option is recognised as the largest risk within the organisation, forcing it to shift to Flexibility in order to meet the needs for dedicated services while allowing human relations and corresponding socialisation ample room to balance existing rules and procedures.

With a wide spectrum of strategic aspects raised it is possible that not all answers align, but in practise these outcomes tend to match one other nicely, thus reinforcing a specific strategic orientation.

3.3. Maturity

Hardjono also dealt with the concept of maturity within his Four Phase model, especially the start up situation. See Figure 4. Any company starts with a good idea (Creativity). The pioneer enters the market, quickly turning to Efficiency in order to collect financial means, attracting employees and integrating them into the core processes. They need to respond to customers’ remarks thus adapting the products and services and probably expanding the

Figure 4. A start up situation gaining maturity.

scale and internal procedures (again Creativity). A new cycle starts. As a start up cycles pass quickly, and with gaining maturity they slow down. The best rhythm is a matter of flow: a balance between external and internal developments. Whenever an organisation fails to meet this flow it jeopardizes its existence.

My criticisms lies in the fact that being on the path of gaining maturity most organisations enter new levels of existence which influence the way strategies are implemented. Each level of existence is characterised by specific institutional arrangements: the dominant leadership style, the policies according which people and processes are managed, the way the organisation is structured, how decision making takes place, the relationship with partners et cetera. All these aspects relate with one and other and reinforce each other.

The nature of the interventions-as suggested by the Four Phase model-remain the same, however the context or value system that appear to be dominant highly impacts the way a specific intervention is implemented. I therefore prefer to apply strategic orientations as situations shifting from one to the next phase within a specific context, or “level of existence” as Clare Graves has put it. The next chapter will reveal an attractive effect once the Four Phase model is combined with Spiral Dynamics.

4. Combining Four Phase Model with Spiral Dynamics

4.1. Spiral Dynamics

Van Marrewijk introduced Spiral Dynamics in several previous publications [3,4,6-8]. Readers, not familiar with Spiral Dynamics, should first turn to this text before continuing with this chapter. We now summarize its features.

Clare W. Graves is the founder of the Emergent Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory. His successors, Don Beck and Chris Cowan, renamed it “Spiral Dynamics” and successfully introduced Graves’ academic achievements to a wider audience [2]. Based on extensive empirical research Graves, who was professor in psychology and a contemporary of Maslow, concluded that mankind has gradually developed eight core value systems so far. Each level of existence-constructed around such a core value system-provides its own hierarchy of needs. Values are considered as coping mechanisms to meet specific challenges and to structure institutions in order to influence behaviour. A value system is a way of conceptualizing reality and encompasses a consistent set of values, beliefs and corresponding behaviour and can be found in individual persons, as well as in companies and societies. The core question that summarises this theory is: how does the mind process reality? Spiral Dynamics does not “label” people and organisations, but it structures thinking systems within entities. It reveals the fundaments of our behaviour that are covered below the surface.

A value system develops mainly as a reaction to specific environmental challenges and threats: the systems brighten or dim as life conditions (consisting of historic Times, geographic Place, existential Problems and societal Circumstances) change.

All entities-including organizations-will eventually have to meet the challenges their situation provides or risk the danger of oblivion or even extinction. If for instance societal circumstances change, inviting corporations to respond and consequently reconsider their role within society, it implies that corporations have to realign their value systems and all their business institutions (such as mission, vision, policy deployment, decision-making, reporting, corporate affairs, etcetera) to these new circumstances. The quest to create an adequate response to specific life conditions results in a wide variety of survival strategies, each founded on a specific set of value assumptions and demonstrated in related institutions and behaviour. Evidently, the strategies introduced above also adopt the influence of specific value systems and show different approaches and alternative interventions.

The development of value systems occurs in a fixed order: Survival; Security; Energy and Power; Order; Success; Community, Synergy and Holistic life system. Each new value system includes and transcends the previous ones, thus forming a natural hierarchy (or holarchy) [9, 10]. Despite the recognition of specific levels, reality is a continuum of developments including transition zones between the levels. These transition phases are highly interesting but are left out in these analyses, leaving ideal type development phases or contexts.

4.2. Dominant Challenges

In determining the strategic orientation we also elaborate on the major challenges that occur within the organisation. We distinguish the following options:

· We need to manage all our operations efficiently in order to protect our margins (Efficiency).

· We need to transform good ideas and innovations into saleable products and services (Effectiveness).

· We need to enhance the dedication and resilience of our people, which are crucial to the success of our organisation, especially since customers demand dedicated services with respect to speed, flexibility and quality (Flexibility).

· We need to gain a better understanding of under surroundings, i.e. the life conditions that impact our organisation, such as the market and technological developments, trends in society and changes in people’s needs. We have to improve our ability to change along with these trends or-better-cause the changes to occur through the impact of our breakthroughs, innovations and new approach to design, produce and market our products and services (Creativity).

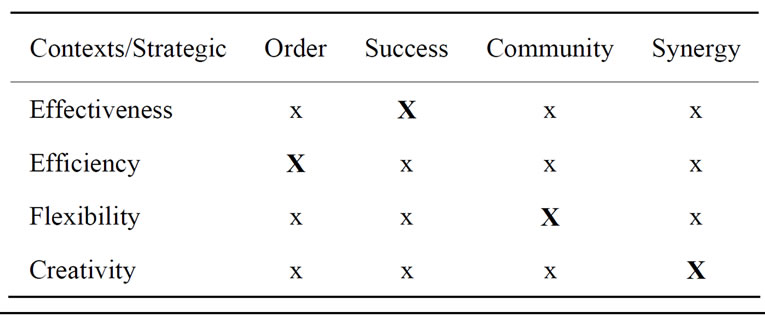

These options have been linked to strategic situations - as indicated between the brackets-but they also relate to contexts: Efficiency can be best implemented in Order, Effectiveness in Success, Flexibility in Community and Creativity in Synergy. However, in practice and theory one can observe all four strategic options in each context. In each context one strategic option can be considered dominant with all other options in a more supportive role.

The issue now arising is that for instance Effectiveness can take different appearances in various contexts. Depending how an organisation interprets one’s business environment and its ambition, values and capabilities, it will adopt the characteristic way of a particular context while implementing a specific set of interventions, associated to a selected strategic orientation.

We here summarize the core appearances of Effectiveness for the various contexts:

· Order: Organisations produce for stock and sell what is available against well-calculated prices;

· Success: A wide spectrum of marketing tools and communication techniques (including packaging) is applied to inform and influence customers to buy products;

· Community: Customers are recognised as human beings, with particular needs. Product qualities align with customer needs. Mass production systems are adapted to small batches with diversified products;

· Synergy: Customers are involved in the early stages of product design. People oriented marketing approaches change the industry. Product qualities align with societal needs.

The effects of contexts on implementing strategic orientations can be acquired via Van Marrewijk, since it can not be dealt within the context of this paper. One can observe that the interventions suggested in the Four Phase model have gained practical use when combined with Spiral Dynamics: the strategic interventions and KPI’s can be made more specific and practical.

In some industries you can see organisations shifting their strategies in a rapid sequence. More often one can observe particular strategies being quite persistent over time, such as a focus on low costs and Efficiency. Here we can see the mixed effects of contexts and situations. Suppose a particular industry can function adequately in Order. Rules and procedures would influence all strategies implemented within Order: Efficiency would be executed in a “blue” way, as well as Flexibility, Creativity and Effectiveness. Companies in Order cannot survive when they maintain their focus strictly on Efficiency. They have to shift their strategy to enhance the other core competences, all be it for a relative short period. Now and than, companies adapt their procedures to include new methods in order to cut costs. The challenge for these organizations remains to keep the prevailing structures from turning into rigid organizations generating reverse effects.

4.3. The Strategy Matrix

With four ideal type strategies and four selected contexts a grid can be made with sixteen combinations of specific situations and contexts. This is the Strategy Matrix, showed in Table 3.

This matrix offers a several distinctive benefits:

1) It expresses a basic philosophy behind the Four Phase model as well as Spiral Dynamics: all management principles, models and even hypes have their value, but often only in a certain situation/context combination. Or put differently: Due to changing circumstances both outside as well as inside organizations, models, tools and certainly hypes have limited applicability and tenability over time.

2) The matrix is therefore able to function as a framework for structuring for instance academic literature on business strategies and related policies. Also, all strategy models and tools mentioned above can be structured according this matrix.

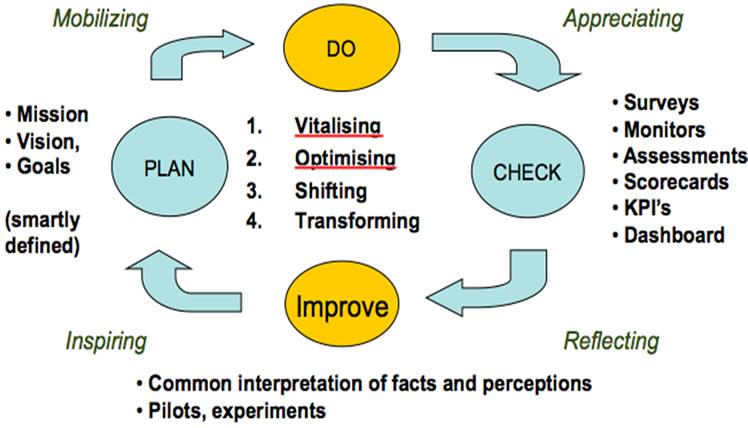

3) The matrix implies four distinctive hierarchical complexity levels in change management: a) vitalising, b) optimising, c) shifting and d) transforming.

4) The matrix offers the conceptual basis for the Strategy Scan, which can generate the most adequate strategic situation and context of organisations, or their product/market combinations.

5) The matrix also offers a conceptual basis for performance cycle from which one can deduct a roadmap for sustainable business improvement and organisation development.

4.4. Four Dimensions of Change Management

By combining the dynamics of the Four Phase model and Spiral Dynamics, in other words: by combining strategic

Table 3. The strategy matrix (Hardjono and van Marrewijk) [6].

X = dominant

x = applicable

“situations” and phase-wise “contexts”, we were able to structure change management into four distinctive hierarchical complexity levels: a) vitalising, b) optimising, c) shifting and d) transforming. These four dimensions of change management are explained below.

Vitalising Often the performance can be improved by enhancing the fundamental skills, structures and procedures of including contexts; These interventions are relatively simple as we have a lot of experience in managing these aspects, but being involved in more complex value systems, we tend to neglect basic competences although they jeopardise current performance potential.

Optimising Once a sound fundament has been realised, further improvement can occur when organisations enhance the effectiveness of the characteristic institutions within the dominant context. Try to find out and apply best practices, work smarter and excel in what needs to be done.

Shifting If including and current contexts are functioning well, further improvement can be established by fine-tuning the strategic situation. Within a context, organisations must focus their business towards the most adequate situation, aligning their interventions accordingly.

Transforming When challenged by more complex conditions, which cannot be met by prevailing work procedures, organisations have to transform into an emerging context in order to sustain their corporate performance. Organisations should adopt new ways of organising by transforming to a more complex context, adopting emerging value systems and all institutions aligned with it. Transformations are complex phenomena, especially if managed as an improvement project.

Having identified the four dimensions of change management, we adapted the Performance Cycle (Figure 5). It is structured according Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Improve sequence. The related activities, provided by professor Wessel Ganzevoort, are “mobilizing, appreciating, reflecting and inspiring”.

Figure 5. Performance improvement cycle, inspired by Deming and Ganzevoort.

The performance cycle suggests various ways to check the impact of the implementation process. Employee perception tools, such as surveys, monitors and assessments, as well as quality management, business operation and accounting tools generate data which via business intelligence services are provided to the board of directors, to management and professionals. Together they interpret the data and determine the progress made. Easy adaptations and fine-tuning are implemented directly, but larger alterations can be tried as experiments and pilots on a small-scale basis, or postponed until they fit the next strategic orientation.

4.5. Strategy Scan

The first step in drafting a roadmap towards sustainable performance improvement and organisation development is finding out one’s position: what are the current constraints, challenges and risks; what are the dominant value systems within the organisation. In short, what (strategic) situation and context are most adequate to face current strengths and weaknesses, opportunities and threads?

In 2003 Van Marrewijk and Hardjono developed the Strategy Scan, based on the Strategy Matrix.

This online scan supports the strategic dialogue, the exchange of facts and experts opinions, and gives a direction to strategy development.

The Strategy Scan is a powerful online instrument, which takes stock of opinions, ideas and perceptions of those directly involved in the company’s strategy formulation process. One can conduct the Strategic Scan in board of directors, management teams, among staff members, and as a vertical dialogue deeper into the organisation as well as outside, even with all stakeholders.

The Strategy Scan supports the strategy dialogue and gives an insight into your organisation’s strategic positioning and context within which the strategy ought to be executed.

The first part of the scan focuses on strategic aspects, which ultimately determine the main direction or strategic orientation of the organisation. Examples of such aspects are the consumer needs and the current bottleneck obstructing organisational performance. The result is a focus and a set of ideal type interventions.

The second part surveys the nature and complexity of the (external) environment and the disciplinary developments (or paradigms) regarding the management criteria such as leadership, people-, resource-and process management. The Strategy Scan indicates the organisation’s most dominant development phase, its favourite level of existence. Combined with the strategic orientation, the researchers and corporate experts can indicate specific interventions and sketch a roadmap for development, aligned with the dominant value systems of the organisation.

The feedback report gives an insight into shared opinions, priorities and most important differences among the responders. The first direct effect refers to the quality of the strategic dialogue with discussions focusing on the topics with a relative high level of variation. In focus groups or a workshop setting with representatives of the different views, one can try to tighten the strategy’s selection and formulation. Furthermore, the Strategy Scan’s result offers a solid base for an implementation plan and selecting key performance indicators.

The Strategy Scan is offered by Research to Improve. They also developed the Strategic Sustainability Scan, an extended version including additional sustainability issues. The Sustainability Scan generates an adequate meaning of corporate sustainability and-responsibility, an ideal type reference on which an organization can develop its own touch and approach. This way one can link strategy with CS/CR-policies and interventions.

5. A Roadmap towards Sustainable Performance

Deducting a roadmap for performance improvement and organizational development can be difficult as each organisation is unique. Many aspects can play a role and not all of them can be foreseen. Still it makes sense to have an idea about the path of change. What can we expect? What level of complexity? Do we have the necessary competences? The right people?

Each organisations must provide its own answers, but at least-by applying the Strategy Scan, the Strategy Matrix and the Performance Cycle-one can grasp its position, its strategic focus, a set of adequate interventions in order to lift the organisation’s bottlenecks and enhance its basic competences, and its dominant context to ‘colour’ the interventions into fitting change activities.

Good surveys can provide management information from which one can tell if vitalisation or optimisation is most effective to enhance corporate performance. Frequently held strategic analyses can provide arguments to remain focused or shift to a next strategic orientation, prioritising a new set of interventions. Strategies can shift permanently within one context. This is relatively simple, but challenging enough.

Changing life conditions can force organisations to gain maturity by transforming into emerging value systems, thus creating new contexts. Strategies will than not only shift to a next phase, but also transform into a new context. Logically, the starting point of the transformation lies in the Creativity phase: adapting to new circumstances have forced the organisation to move its boundaries, to create adaptations “out of the box”, introducing new ways of doing things. Leaving Order, a company will start adopting Effectiveness in a more entrepreneurial, profit-driven way. Marketing and leadership will be the pioneers in adopting a Success-driven approach, with People-and Process Management quickly catching up. After a while, Learning and Innovation and Communication and Decision-Making could be the two enablers, which will face the next performance constraint. When functioning within Success seems no longer adequate anymore, the need to sustain performance improvement will force the organisation to transform once more, this time into Community. It will support the need to learn, collaborate, engage and meet with society needs.

Strategic orientations (phases) as well as levels of existence (contexts) brighten and dim as responses to changing environmental circumstances and internal considerations, such as organizational structures and intrinsic motivations. We now elaborate on two developments situations: times of crises and a performance gap.

Crises Ideally, strategies develop ‘clockwise’ in a natural sequence, creating additional competences and adding to the organization’s total sum of assets. Especially in economic downturns, one can observe sudden shifts backwards! From for instance Efficiency back to Effectiveness, thus remaining in a control mode and ignoring the need to become more flexible and socialisation oriented. Due to such shifts specific competences are lost, expectations shattered and total sum of assets diminishes. But these shifts-for better or worse-can also support the organization’s survival.

Due to changing life conditions organizations can also choose to shift to less complex value systems. The more complex ones are more vulnerable and difficult to sustain when times are hard. Eventually, tides will turn and organizations, as well as individuals and societies, will try again the more complex value systems in order to escape the limitations of the former ones.

Performance gap Especially when centred in Success, organisations like to benchmark. Certain benchmarks such as the very best Great Places to Work® [11] and High Performance Organisations (HPO’s) [12] have average scores of 85% to 90%, while ordinary organisations only score for instance 50%. These benchmarks provide a high performance level but do not provide intermediate ‘stepping stones’. A target aimed at a 10% increase doesn’t make much sense. The point is what should an organisation do and try to accomplish with the least effort and with maximum effect: first focus and than select the nature of the intervention and determine in what context the best contribution can be made.

In trying to bridge the performance gap, organisations often need intermediate goals. With the matrix and cycle introduced above, one is now able to design a development path with the intermediate goals as stepping goals towards the ultimate result. Both children and top athletes take the same approach in trying to establish espoused performance levels.

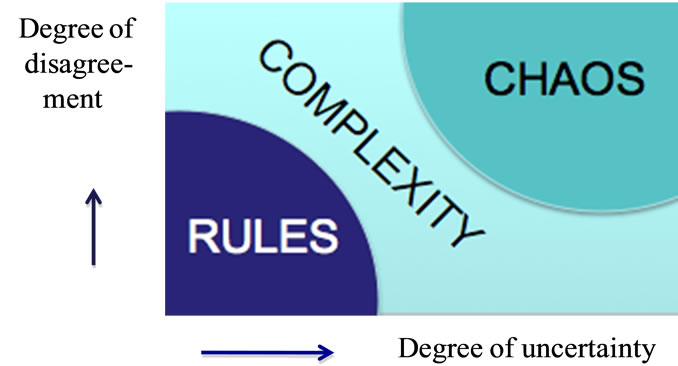

In designing a roadmap for change and performance improvement it is important to be aware of the complexities at hand. In a stable world one can predict the best approach and establish the expected results much easier. Prof. Ralph Stacey [13] defined this realm as ‘rules’. In Spiral Dynamics it coincides best with Order. If one is uncertain of the impact of interventions, complexity increases, ultimately reaching the level of chaos. See Figure 6. Strategies are aimed at bringing down the level of complexity in order to be better able to predict and manage, preferably control, the outcome of one’s activities.

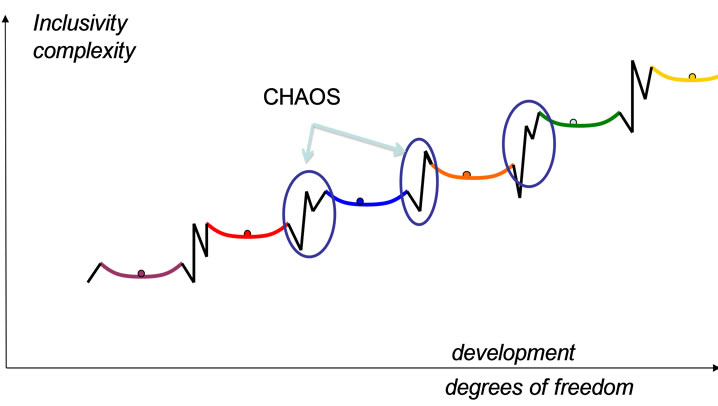

Van Marrewijk presents Spiral Dynamics’ levels of existence as ‘local’ equilibriums [14], offering adequate solutions to prevailing circumstances. See Figure 7. At each local equilibrium a specific set of values ‘rules’ and determines the institutional structures and patterns of behaviour, with which people and organisations are able to cope with prevailing circumstances. The moment entities become aware that current behaviour is no longer adequate to meet new challenges, periods of chaos emerge. Facing increasing complexity, people and organisations have to transform into new value systems. Each transition contains elements of chaos, due to people’s resistance for the unknown, leaving behind old patters of behaviour and trying to get accustomed to new institutions, to new ways of working and new competences.

Once people and organisations feel aligned with a new context, a new level of existence, they can apply their newly acquired competences to deliver adequate solutions

Figure 6. Reality according Prof. R. Stacey.

Figure 7. Phasewise orientation according Graves, (representation by van Marrewijk).

to prevailing challenges. They are able to match a higher level of complexity, as if complexity has been transformed into the realm of Stacey’s rules.

Turning back to the issue of bridging performance gaps, one can observe in Western economies that successful workplaces and HPO’s are often centred in Success /Community/Synergy, while the majority of organisations seem to function within Order/Success and still, quite a lot are in Power/Order.

A 40% performance gap can statistically be overcome by an average performance improvement of 4% for 10 years in a row. In practice it could imply a transition from a power-oriented organisation, via a shareholder, controland profit-driven organisation to a stakeholder-oriented organisation. This is not an easy task, certainly not in 10 years time.

6. Corporate Sustainability (CS)

In this chapter we focus on sustainable performance, the ability to sustain organisational performance over time. Through shifting strategic orientations ‘clockwise’, thus building up basic competences that match the challenges and bottlenecks occurring in business operations, organisations remain fit, flexible and balanced, thus securing the best performance possible.

The philosophy behind the Four Phase model does have added value in understanding a second interpretation of corporate sustainability. One that is related to balancing people, planet and profits [5].

The Four Phase model offers specific contributions regarding the topic of sustainability, the latter interpretation. The first one relates to its philosophy: Since all organizations and individuals have the same set of basic assets, they can exchange their assets among one other as for instance happens between organizations and their customers and suppliers. In Order and Success organisations tend to emphasis shareholder value, through focusing on control and resource management. Apart from the basic exchange of assets with customers, these organisations tend to enhance their total sum of assets mainly through internal activities. Inevitably, this approach reaches its boundaries, forcing companies to seek new opportunities to grow their assets and sustain their performance. The limits of growth can be overcome by transforming into new emerging contexts, thus facing a period of change and chaos due to learning new ways of doing business (Figure 6).

In the process of sustaining corporate performancethus enhancing corporate sustainability in both interpretations-organizations learn to involve their stakeholders in corporate decision-making and business practices. Organisations demonstrating Community and Synergy learn from one other, theoretically spoken they exchange intellectual assets with stakeholder inside (employees) and outside (customers, neighbourhood, etc). Involving customers in for instance product design impacts the innovation process of new product formats that include added values for various stakeholders. Therefore, Corporate Sustainability1, ultimately, means totalling the sum of assets, not only of the company, but of a much wider group of entities, eventually including the whole planet. In this latter context, CS implies that the material assets include the planet’s resources (natural capital). Depletion or exploitation of these resources is at best a zero sum game, which is no longer an attractive business objective.

Functioning in Synergy implies that organizations operate in an open system surrounded by other open systems. The interaction between these systems will lead to new and unexpected opportunities. By forming coalitions these possibilities can be explored and exploited in a way that they create added value for everyone concerned, generating added value not only in a material/financial way, but also in a commercial, social and intellectual way.

Managing the complexity of thinking and working in an environment of open systems, full of coalitions, offering great variety and diversity, opens the way to introducing “basic rules”. Only when you have mastered complexity, simplicity might work. Basic rules can be understood as the principles by which complex systems function. Paradoxes and dilemmas are seen as effects and sources of inspiration, often leading to new insights, new ideas, new concepts and new learning experiences.

The second contribution of the Four Phase model lies in aligning the strategic orientations with specific sustainability activities associated with the Triple Bottom Line. In stead of implementing CS-R activities as ‘add-ons’ to business operations, it will generate much more impact when out of many potential CS-R activities those ones are selected which will reinforce the effect of selected strategic interventions.

The two concepts described in this chapter, the strategic phases and development contexts, are distinct notions. The contexts are broader, psychological stages in evolutionary development, while the phases are more instrumental, structuring the interventions for strategy implementations.

The Strategy Matrix-integrating both concepts-presented above can help executives and business consultants to understand organization dynamics in general and facilitate them in plotting a course for organizational change, shifts or transformation, whenever they want to implement a more ambitious approach towards CS and CR, or corporate improvement in general.

7. References

[1] T. W. Hardjono, “Ritmiek en Organisatiedynamiek: Vierfasenmodel,” Kluwer, 1995.

[2] D. Beck and C. Cowan, “Mastering Values, Leadership and Change,” Spiral Dynamics, Blackwell Publishers, 1996.

[3] M. van Marrewijk, “Concepts and Definitions of Corporate Sustainability,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 44, No. 2-3, May 2003, pp. 95-105.

[4] M. van Marrewijk and M. Werre, “Multiple Levels of Corporate Sustainability,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 44, No. 2-3, May 2003, pp. 107-119.

[5] J. Elkington, “Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business,” Capstone Publishing Ltd., Oxford, 1997.

[6] M. van Marrewijk and T. W. Hardjono, “European Corporate Sustainability Framework for managing Complexity and Corporate Change,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 44, No. 2-3, May 2003, pp. 121-132.

[7] M. van Marrewijk, “European Corporate Sustainability Framework,” International Journal of Business Performance Measurement, Vol. 5, No. 2-3, 2003, pp.95-105.

[8] M. van Marrewijk, “A Value Based Approach to Organisation Types: Towards a Coherent Set of Stakeholder Oriented Management Tools,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 55, No. 6, December 2004, pp. 147-158.

[9] K. Wilber, “Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution,” Shambala Publications, 1995.

[10] K. Wilber, “A Theory of Everything: An integral vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality,” Shambala Publications, 2000.

[11] M. van Marrewijk, “The Social Dimension of Organizations: Recent Experiences with Great Place to Work® assessment practices,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 55, No. 2, December 2004, pp. 135-146.

[12] J. C. Collins, “Good to Great,” Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2001.

[13] R. Stacey, “Strategic Management and Orgnisational Dynamics,” 5th Edition, Prentice Hall, 2007.

[14] M. van Marrewijk, “The Cubrix, an Integral Framework for Managing Performance Improvement and Organisational Development,” Journal of Technology and Investment, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2010, pp. 1-13.

Abbreviations

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CS Corporate Sustainability

CR Corporate Responsibility

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

ECSF European Corporate Sustainability Framework

ECLET Emerging Cyclical Levels of Existence Theory

EU European Union

HPO High Performance Organizations

KPI Key Performance Indicator

NOTES

1Corporate responsibility, in this sense, means being accountable for working in such a way the total sum of assets will increase for direct or indirect stakeholders, now and in the future.