Journal of Service Science and Management

Vol.6 No.4(2013), Article ID:38703,6 pages DOI:10.4236/jssm.2013.64028

The Reduction of Drug Abuse in Taiwan and Its Information System Application—An IT Enabled Service Innovation in E-Government

![]()

Department of Management Information Systems, National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Email: 98356507@nccu.edu.tw

Copyright © 2013 Larry F. K. Chang. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received April 11th, 2013; revised May 13th, 2013; accepted June 15th, 2013

Keywords: IT-Enabled Service; E-Government; Drug Abuse Reduction Service

ABSTRACT

The drug abuse problem is one of the toughest issues currently facing governments around the world. Typically, drug offenders are arrested, jailed for a time and then released, but there is high probability that they will become repeat offenders after leaving prison. This typical solution is a significant waste of administrative resources and fails to reduce the rate of recidivism among drug abusers. Recently, more countries are treating drug abuse offenders as patients, offering them drug substitution treatment in order to reduce dependency on illegal drugs and lower the risk of AIDS infection. Patients go to work as normal, live normally, and retain their human dignity. In this study, we use the service blueprinting method to show how Taiwan’s drug abuse reduction service cares for drug offenders. The service integrates several Taiwanese governmental ministries by using a single information management system which is triggered automatically when the drug abuse offender leaves prison. We analyze this case using the Service Open System View framework and provide suggestions for improving the existing service. From the academic viewpoint of service science, this study shares the case of Taiwan’s drug abuse reduction service and provides suggestions for best practices which can improve existing services.

1. Introduction

The drug abuse problem is always ranked as one of the toughest issues faced by governments worldwide. Drug abuse offenders are difficult to monitor once they leave prison. Detoxification services are also difficult to perform on offenders who are not incarcerated. On the other hand, drug abuse offenders cannot easily find jobs and can be easily enticed back into the drug abuse culture. Therefore, there is a high probability that they will become repeat offenders after leaving prison.

Drug harm reduction service providers face a complicated service process spanning several ministries including the Ministry of Justice, police agencies, the Council of Labor Affairs, and the Department of Health. This kind of service is complex and extremely difficult. At first glance, this predicament appears to have no correlation with information technology (IT); however, a careful review of the problems, procedures and regulations regarding drug abuse shows that IT can actually provide a significant contribution to services engaged in drug harm reduction.

Taiwan’s “Single Window Service for Drug Abusers” (SWSDA) project began in December, 2008 [1]. The SWSDA project included the creation of the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders that collects valuable information from all relative ministries and agencies. The creation of a standard operation procedure (SOP) for local Drug Abuse Prevention Centers was also part of the project. The collected information and SOP have been of great assistance to counselors at the Drug Abuse Prevention Center who are responsible for supervising offenders released from prison to rejoin society. In January, 2009, the service was launched by the Drug Abuse Prevention Centers in Taipei City, and in the counties of Taipei, Taoyuan, Tainan and Taitung. In May of that same year, the service was extended to the entire country.

Since the success of IT-enabled service depends on not only IT but also on the coordination of service co-creators, this study discusses the case of SWSDA from the perspective of the Service Open System View [2]. In addition, we attempt to identify service gaps and provide suggestions to fill them.

This article has three major parts. First, we briefly review drug harm reduction studies in the extant literature and describe the substitution method for treating drug abuse. Second, we introduce the details of Taiwan’s SWSDA project. Finally, we discuss the service gaps and corresponding solutions.

2. Related Literature and Governmentally Administered Drug Abuse Treatment Services

Substitution treatment offers drug abuse offenders methadone or buprenorphine as a replacement for their illegal drug of choice. Methadone and buprenorphine are less addictive and allow long intervals between doses. This allows drug abuse offenders to reduce their drug use and resolve the drug abuse problems they experience in daily life. Furthermore, the substituted drug is not a liquid to be injected into the body; it is taken in pill form. Because of this, the number of patients with infectious, injection-transmitted diseases such as AIDS, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and endocarditis decreases.

A study of 506 drug abusing males in New York in 1988 showed that 71% of the observed subjects did not inject drugs during the substitution treatment period. Sixty percent of the observed subjects were still not injecting drugs more than a year later. However, 80% of observed subjects who were not in the substitution treatment program abused drugs again within twelve months [3].

A 1996 study conducted across 15 states in the U.S. by the U.S. National Institute of Drug Abuse observed 2,973 subjects, including a substitution treatment experiment group and a reference group. After 6 months of observation via urine testing, the study reported that the number of people in the experiment group who did not abuse drugs was 3 times the number of non-abusers in the reference group [4].

Hong Kong’s Methadone Treatment Programme began in 1972, and was put into practice in the entire Hong Kong area in 1976. The program is jointly administered by the Hong Kong Narcotics and Drug Administration Unit and The Society for the Aid and Rehabilitation of Drug Abusers. The goals of the Hong Kong Methadone Treatment Programme are: 1) to provide easy, legal, and medically safe and effective drugs; 2) to help drug abuse offenders become self-reliant and live a normal life; 3) to reduce the case of needle sharing through monitoring, health education, and counseling; 4) to encourage drug abusers to receive treatment; and 5) to help drug abusers detoxify (treatment, rehabilitation and reintegration). The program has one assistant director-general, three fulltime senior doctors, 26 social workers, 42 doctors, and 135 medical assistants who provide services in the nighttime clinics. Twenty methadone clinics are open 365 days a year, from 7:00 to 22:00 [5]. The shorter the waiting time for service, the fewer the cases of drug abuse. If a gap exists between the methadone maintenance treatment and the drug abuse demand, the drug abuse offenders may resort to illegal drugs again.

This particular program has been running successfully for more than 30 years. The government of Hong Kong uses the substitution treatment to save the drug abuse offender’s life first and work on abstinence and rehabilitation later.

In 2008, Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice performed a two-stage investigation into drug abuse offenders involved in various types of criminal activities [6]. The purposes of the first stage of the investigation were to determine drug abuse offenders’ need for Careline (a call-in service), assess their understanding of the purpose of the Drug Abuse Prevention Center, and identify any difficulties and needs they have in the process of rejoining society. The objective of the second stage was to assess drug abuse offenders’ demand for job training and employment. The second stage investigation intended to determine the correlation between Careline calling time and the content of drug abusers’ requests in order to effectively and economically allocate manpower and other related resources within Careline. The research findings revealed the following: 1) In order for Careline to provide helpful service for drug abusers, resources from related agencies such as Drug Abuse Prevention Centers, the Department of Health, and the Council of Labor Affairs must be integrated. 2) Careline should provide services 24 hours a day for different types of drug abusers. 3) channels to provide help must be integrated in order to be more convenient for drug abusers. 4) Drug Abuse Prevention Centers must promote and advertise their services to the public consistently and frequently. 5) The Drug Abuse Prevention Centers and the frequency of individual counseling service for drug abusers must be advertised often in the prisons,. 6) Employment facilitation programs for drug abusers should be initiated.

3. Project Case

3.1. The Drug Abuse Problem in Taiwan

Of the various types of criminals in Taiwan, drug offenders are the most numerous. Of all the prisoners in correctional facilities, including prisons and jails, 38.5% (25,064 persons) are drug offenders. To make matters worse, the recidivism rate for drug offenders is 79.3%, and 72.9% of recidivists are addicted to heroin or morphine.

Full rehabilitation from a drug addiction is very difficult. Once out of prison, repeat drug offenders increase the recidivism rate and waste considerable social resources. In practice, drug addicts should be treated as patients. Taiwan’s Narcotics Endangerment Prevention Act was adopted to this end in 1998; first-time drug offenders are treated as patients, and the first repeat offense is treated as a criminal act.

The policies for drug harm prevention also changed gradually from arrests and confinement to directing drug offenders toward substitution treatments. Substitution treatments enable drug addicts to overcome their addiction to drugs, to work properly, to live a normal life, and to retain their personality. The treatments also reduce the risk of AIDS infection from heroin injections, and help eliminate the social problems arising from misdemeanors related to drug abuse.

3.2. Related Agencies and IT-Enabled Services in Taiwan

Taiwan’s Department of Health is the primary promoter of substitution therapy. The Department of Health launched a drug addiction and AIDS harm reduction program and assigned each local Health Center to adopt drug substitution therapy. The District Prosecutor’s Office of Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice suspends the prosecution of repeat drug offenders and forces those offenders to be treated with drug substitution therapy at the local Health Center. Every county and city government in Taiwan has set up a local Drug Abuse Prevention Center. The Taiwanese government expects that the above programs will detoxify up to 15,000 prison-released drug offenders a year, reducing the impact on the community once the drug offenders are out of jail.

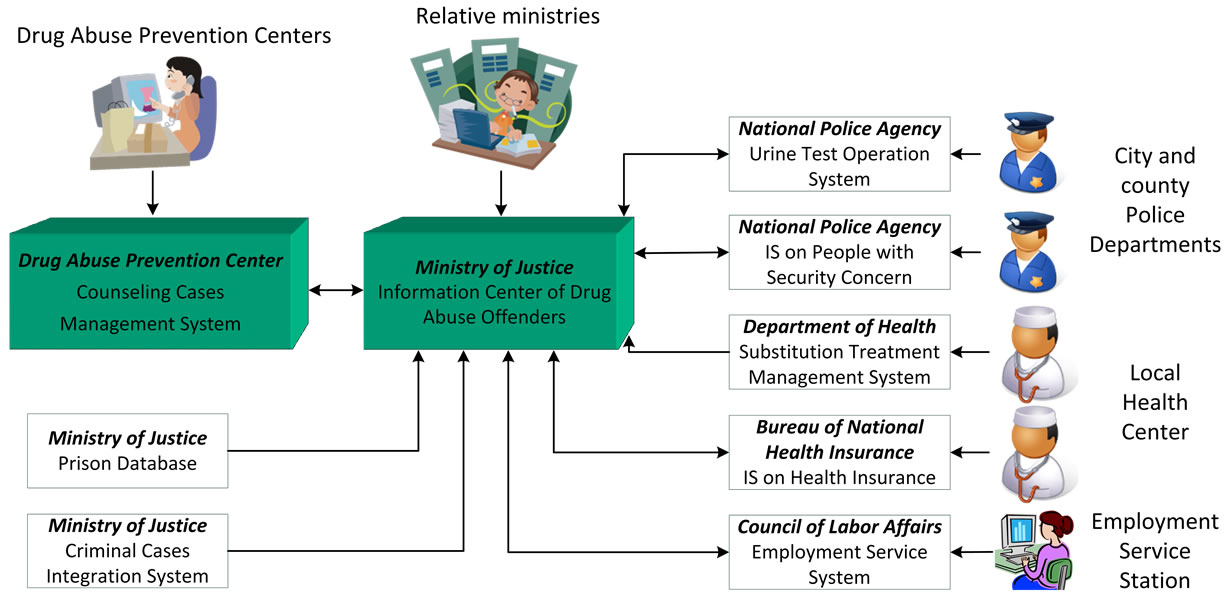

In May of 2009, the Department of Information Management in Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice took over an ITenabled service for drug abuse reduction that was named “Single Window Service for Drug Abusers” (SWSDA) [7]. Figure 1 shows the stockholders in the server ecosystem. And, the SOP for this service comprises the following steps. 1) The criminal case database in the Ministry of Justice exports personal information on drug offenders who will be out of prison soon to the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders. The assessment of detox outcomes for those drug offenders during the period of imprisonment is transmitted from the prison database to the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders. 2) The Department of Health collects real-time substitution treatment information regarding drug abusers from each local Health Center, and exports that information to the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders daily. This allows the counseling staff of the Drug Abuse Prevention Centers to be fully aware of the governance status of substitution treatments reported by the counseling caseworkers. 3) The National Police Agency collects drug offender urine test records from city and county police departments. It also collects reports on inspection visits by police officers concerning the security status of drug offenders, and exports the data to the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders in order to monitor whether the offenders are going back to using drugs or have broken contact with the local police office. 4) The Council of Labor Affairs collects information about drug abuse offenders who participate in job training provided by city or county governments, and information about offenders who have gotten jobs, and exports that information daily to the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders. This allows the counseling staff of each Drug Abuse Prevention Center to be fully aware of the employment status reported by the job training caseworkers. 5) Each member of the counseling staff of the Drug Abuse Prevention Centers must not only access the information about drug abuse offenders but also update the detailed information about daily counseling cases for the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offenders. 6) The Bureau of National Health Insurance provides an online connection to query the health insurance information for each drug abuse offender insured by an employer in order to monitor the latest employment status of drug abuse offenders.

3.3. SWSDA Service Gaps According to the Open System View

The character of service organizations is sufficiently unique to require a special management approach. Because of this distinctive character, the system view must be expanded to include the customer as a participant in the service process. On the other hand, the customer is viewed as an input that is transformed by the service process into an output with some degree of satisfaction [3].

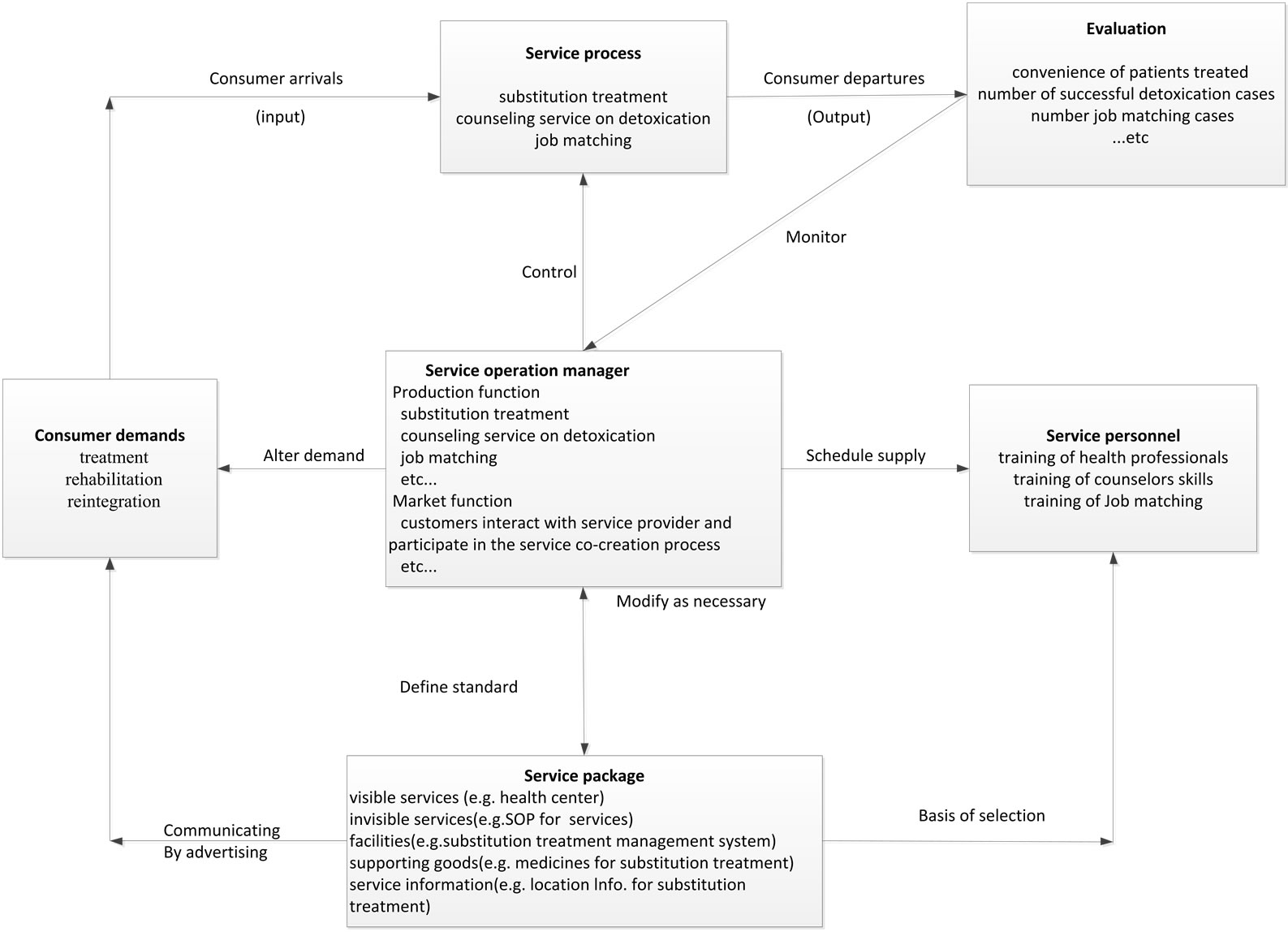

In this study, we adopt the Open System View created by Fitzsimmons as a lens through which to analyze Taiwan’s SWSDA and identify service gaps. Figure 2 shows the 6 key components defined in the Open System View: consumer demands, service process, evaluation, service personnel, service operation manager, and service package.

• Consumer Demands: Easy, legal, and medically safe and effective drugs which are less addictive and allow long intervals between doses. Drug abuse offenders can reduce their use of illegal drugs and avoid drug abuse problems in daily life.

• Service Process: Based on consumer demand, the service provides substitution treatments, detoxification counseling services, job matching, etc.

Figure 1. Related government agencies.

Figure 2. Open System View.

• Evaluation: The service evaluates overall customer satisfaction during the entire service process. Customer satisfaction factors include the convenience of patient treatments, the number of successful detoxification cases, and the number of successful job matching cases.

• Service Personnel: This is regarding the training of various personnel: health professionals, counselors who provide services to drug abusers, counselors who evaluate whether the drug abusers are suitable for substitution treatment, and others.

• Service Operation Manager: The objectives of service operation managers are to meet customer demand through the interaction between customers and service staff, control the service process, monitor service quality measurements, schedule service staff training, and define the service standard. The “production function” treats all processes (substitution treatments, detoxification counseling service, job matching, etc.) as services. Customer interaction with the service provider and participation in the service co-creation process is an important source of information in the “market function”.

• Service Package: SWSDA is unusual in that it is humanitarian in nature and yet maintains law and order; it is both a kind of social welfare and a kind of compulsory medical service. The related laws and regulations used in the SWSDA have to be established before the service is launched because the service requires a significant number of fulltime staff who must have the appropriate legal status, and the compulsory medical services must have a legal basis. The experience gained by interactions between drug abusers and service staff should feed back to the law amendment process in order to fill the gaps between legislative knowledge and actual daily practice.

4. Discussion

Based on the analysis above, this study has identified five service gaps in the SWSDA. These gaps and the recommended solutions to fill the gaps are discussed below.

4.1. Service Personnel

Gap 1: The Drug Abuse Prevention Centers have no fulltime employees devoted to counseling or serving drug abusers.

The idea for the Drug Abuse Prevention Center was generated in the first Drug Abuse Prevention Meeting which was held by Taiwan’s Executive Yuan (the executive administration in Taiwan) in 1996. Executive Yuan then asked the offices of the district prosecutor in Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice to assist local county and city governments to establish Drug Abuse Prevention Centers. The Drug Abuse Prevention Center is only a service concept, a part of the daily operational activities of local government staff. Therefore, there is no fulltime employee in any Drug Abuse Prevention Center, preventing it from actually monitoring all drug abuser counseling cases.

Lack of manpower is one of the Drug Abuse Prevention Center’s most critical problem. In the short term, we suggest that the Taiwanese government should use the secondary reserve funds in Executive Yuan for the Drug Prevention Center to hire contract personnel who have counseling skills. In the long term, we suggest that legislation be passed to change the Drug Abuse Prevention Center from a service program to a physical department so that Drug Abuse Prevention Centers will have their own budget and staff.

4.2. Service Operation Management

Gap 2: Counselors and medical personnel do not build relationships and trust with drug abuse offenders before the offenders are out of prison. Monitoring drug abuse offenders becomes difficult once they are out of prison. Thus, it is not easy to perform detoxification service afterwards.

The Drug Abuse Prevention Centers’ lack of manpower makes it impossible for counseling staff to conduct face-to-face and one-on-one counseling before the drug abuse offenders leave prison. Accordingly, counseling staff have difficulty making connections with drug abusers.

For this gap, we suggest that Drug Abuse Prevention Centers increase the frequency with which they advertise in prisons. The advertisements should put more emphasis on introducing the functions and roles of the Drug Abuse Prevention Center. They should also form a professional, familiar, and caring human image in the drug abuser’s mind, bringing the counseling staff closer to the drug abusers.

Gap 3: Drug abuse offenders have no employment and residence mechanisms once they are out of prison. There are no related organizations to administrate such mechanisms.

While in prison, drug abuse offenders find obtaining illegal drugs to be difficult, if not impossible. Once out of prison, however, reverting back to abusing the drug is easy. The primary reason is that, once they leave prison, a lot of drug abuse offenders are not accepted or helped by their family. They have no stable place to live, they are vulnerable to social exclusion, and they can be easily enticed to rejoin others in the drug culture. Thus, drug abuse offenders are highly likely to take drugs again. On the other hand, the employment of ex-convicts (convicted offenders who are out of prison) is rare because employers are not willing to employ former prisoners. Thus, drug abusers have get difficulty making ends meet and living like normal people.

Currently, there is only one law (Narcotics Endangerment Prevention Act 25) in Taiwan related to ex-convicts who are drug abuse offenders. These ex-convicts must regularly have their urine tested within the first two years after their release. We suggest that Taiwan should establish halfway houses and allow drug abuse offenders to spend the last half of their sentence in these residences. This suggestion results in two positive outcomes. The first is that the drug abuse offenders can get jobs and return to the community under strict surveillance. The second is that drug abuse offenders can try to resist taking drugs when they return to the community. They can either find jobs on their own or with the help of a government agency. On the other hand, drug abuse offenders must also regularly submit to urine tests. If they take drugs again or do harm to society again, they return to prison.

4.3. Evaluation

Gap 4: Substitution treatment is not yet universally effectively executed in Taiwan.

Hong Kong, Singapore and the US are testaments to the effectiveness of substitution treatment, especially Hong Kong which has practiced this treatment for more than 30 years with great success. In contrast, only 20% of Taiwan’s local health centers provide substitution treatment, and drug abusers are unaware that they can get help from the government. Counselors should make more effort to promote substitution therapy and help drug abusers engage in this kind of treatment.

First, we suggest that the government integrate all the assistance channels—including prisons, Drug Abuse Prevention Centers, police departments, health centers, and employment services—in order to provide more convenient services. Second, we suggest that the government build a 24/7 call center as a service window for different customer needs

4.4. Service Package

Gap5: The Drug Abuse Prevention Centers have no service SOP (standard operation procedure) or rules, and the related organizations lack service measurements.

There is no standardized service process in the local Drug Abuse Prevention Centers of different cities and counties. We suggest that the government design a uniform process for all Drug Abuse Prevention Centers. Another concern is that performance measurements for the goals of drug harm prevention are not well established. For instance, one of the current measurements for police effectiveness in the field of drugs harm prevention is the number drug abuse offenders arrested. We suggest the measurements should be changed from the number of arrests to the number of drug abuse counseling cases opened. The weighting of the measurements in counseling cases should also be changed. When the police perform inspection visits to determine the security status of drug offenders, they should introduce the drug abuse reduction service instead of arresting the offenders again.

5. Conclusion

The SWSDA in Taiwan is working but not to its full potential. There are five gaps in the current service. After discussing the service gaps in the SWSDA, we suggest improvements to fill those gaps. The ultimate goal is to make the drug abuse reduction and prevention effort more effective through IT-enabled services that are easy to use, convenient, and useful for people struggling to overcome drug abuse. With a clear goal in sight, the service can become more and more complete. Drug harm reduction work is difficult, but there are many successful cases from which lessons can be learned. Even with only a 10% - 20% reduction in the drug offender recidivism rate, the SWSDA still has great potential to benefit Taiwanese society as a whole.

REFERENCES

- Anonymous “Ministry of Justice to Promote the City and County Drug Control Act Was Officially Entered the Information Technology Operations,” Announcement of Ministry of Justice in Taiwan. http://www.moj.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=158298&ctNode=28172&mp=001

- J. A. Fitzsimmons and M. J. Fitzsimmons, “Service Management: Operations, Strategy, Information Technology,” 6th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2008.

- J. C. Ball and A. Ross, “The Effectiveness of Methodone Maintenance Treatment: Patient, Programmes, Service, and Outcomes,” Springer-Verlag, New York, 1991, pp. 160-176. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-9089-3_7

- D. S. Metzger and H. Navaline, “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention and the Potential of Drug Abuse Treatment,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 37, No. 5, 2003, pp. 451-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/377548

- S. Xu, “Harm Reduction Programs—Methadone Maintenance Treatment Program,” Taiwan Lourdes Association, http://www.lourdes.org.tw/list_1.asp?id=602&menu1=5&menu2=31

- C.-C. Hung, “Analysis of the Needs of Drug Addicts from Questionnaire in Taiwan Correctional Facilities,” Department of Corrections Ministry of Justice in Taiwan. http://www.moj.gov.tw/

- C. Chen, “Building the Information Center of Drug Abuse Offender-Strategic Planning for Drug Abuse Prevent Policy,” Bimonthly Journal for Research Development and Evaluation, Vol. 32, No. 1, 2008, pp. 66-76.