iBusiness

Vol. 4 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 25645 , 9 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2012.44038

Comparative Analysis of the Management Practices and Behaviour of Small and Medium Information Technology Enterprises

![]()

Department of Production Engineering, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil.

Email: taciana.barros@gmail.com

Received August 28th, 2012; revised September 28th, 2012; accepted October 22nd, 2012

Keywords: Small and Medium Business; Strategic Thinking; Information Technology

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the role and influence of management practices and behaviour in successful small and medium sized information technology enterprises (SMET), based on the comprehensive concept of Mintzberg 5Ps of strategy (1992) [1]. The study employed a survey of 13 SMET with were examined on how closely they used best strategic practices in their management and how it is related to SMET performance. The discussion and conclusions highlight different ways of strategic thinking, the importance of the mutual trust and commitment between managers and employees. Specifically, we determine three elements whose greater exploration can lead to a deeper understanding of how the strategic planning is influenced by the manager’s view, in order to encourage their competitiveness through market environmental uncertainties.

1. Introduction

Small and medium businesses have become important in economic and social development [2], their main characteristics are: size, structure, culture and resource constraints, entrepreneur types of behaviour or attitudes towards risk; tend to opt for informal practices, have an ad hoc entrepreneurial process and the management process and cultural dimension [3,4]. To Westhead et al. [5], entrepreneurs have management based on flexibility and share knowledge with their employees to reduce the market risks. In order to identify the type of product to be produced, where and to whom it will be sold, and product features such as cost, customization, reliability and delivery [6] of small and medium information technology firms (SMET) prompt their strategy.

A considerable number of studies have been done to understand “what managers really strategizing” [7,8]. These studies including human capital [9,10], employees innovative behaviour [11-13], effective recruitment and selection practices [14], a good training and development. These issues are critical to support the strategic planning to create superior performance or competitive advantage through the process of transferring benefits from the companies to their customers [13]. However, various aspects related to SMET to avoid the strategic thinking: fear of the weaknesses, lack of knowledge of the strategic planning process, fear to deal with market risks and uncertainties.

Our study concentrates on managers in (SMET), as a first step to elucidate their behaviour nature to develop strategic planning based on the five P-propositions [1]: Plan—This is a formal process or a course of action to deal with a situation. The manager is analytical and has ability to organize internal resources; Pattern—Is a stream of actions, the manager develop skills among work strategies in the process of organizational learning; Position—Formal process to access excellence level to locate the product or services in certain markets conditions. The managers adjust their effort and skills; Perspective—The manager act in accordance with external environments; provide useful information to achieve external and internal environment goals; Play or Ploy—Way of handle competitors and reduce the market threats, the manager articulate the strategic and motivate their employees.

The main objective of this research is to analyse the influence of SMET’s manager behaviour on the process of strategic planning based on the theoretical framework of five systematic P-propositions [1,15]. This descriptive study of 13 SMET’s managers rests on Yin model [16]. The data sample collected between the years from 2009 to 2012, and a real name of SMETs will be preserved, we denominate as “Case Study”. And, we link SMET management and their members to promote valuable ideas to engage the innovation efforts [17] according to their innovative behaviour and internal incentives [18].

2. Literature Review

Innovation has concentrated on firms’ financial performance, organizational incentives [19-21] and on the generation of feasible ideas [12] relies on the creativity, transfer and retention of knowledge of individuals [22]. These SMET members learn together [23] as learning organization. They have different specialties and act like a horizontal networks relationship to choose a course of action [24], have a clear vision about their goals, and communicate to interact [25]. However, the innovation incentives have risk and unpredictable outcomes [26].

In this complex scenario, SMET must develop strategically to make the most effective use of its resources and capabilities in order to remain competitive. To Sambamurthy et al. [27] there are three distinct “logics of strategy” for SMEs: 1) positioning-to identify the forces of the industry, firms seek profitability, and use an integrated system of activities focus on external forces without reinforcing internal activities; 2) leverage-firms try to overcome the weakness by deploying their inimitable resources and competencies to reach a stable position; and 3) opportunity-ability to innovate and develop superior market intelligence using the strategic planning, it builds strong external relationships, proper market responsiveness [28], and enable agility and flexibility [29].

Committing resources can be an indicator of the organisation’s strategic intent [30]. Training can affect these organizations, because individuals skills and creativity convert a new idea into a product or service, which customers need [31], towards meeting the organization’s objectives in a more systematic and effective way [32]. SMET needs an effective means of monitoring their internal and external sources of opportunity to apply them into managerial practice to build partnership with firms having core competencies specializing in the other elements in the information technology chain: testing, production, marketing, distribution, and logistics or distribution.

Business partnerships combining or incorporating complementary components in each chain participant. This SMET characteristic is very complex, and requires external variety of knowledge and expertise.

3. Methodology

This descriptive and explanatory case study uses a quailtative method of multiple-case studies [33,34]. It creates theoretical constructs and propositions based on empirical evidence. Data were collected from semi-structured interviews, questionnaires, analysis of company documents, media communications and observation [35] that could prove or provide further explanations of the topics of the interviews. The structure of the questionnaire addressed on nominal scale and open-ended questions with the empirical events interpretation [35] on a set of 13 case studies of Brazilian SMET. We considered size, dynamic, capability perspective, exploratory and transformative learning in changed environments. As well as, the strategic intent, since the leaders behaved differently from the ways [15] trying to create a powerful goal since individuals could share knowledge throughout the organization. All respondents are managers; each interview lasted about 1 hour.

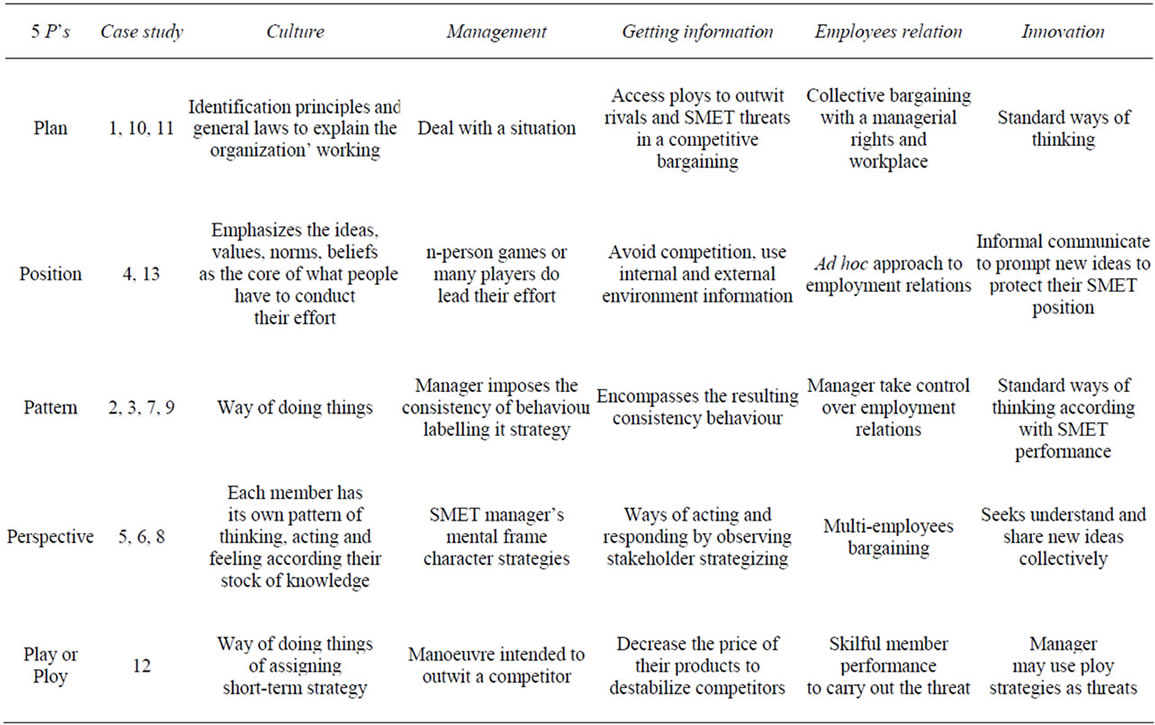

The protocol in this research relies on Yin model [17]. And the approach is based on Mintzberg 5Ps [14] to describe what really happens in information technology organizations that tried to create successful strategic innovation. Therefore, we opted to make a pre-test questionnaire, using a pilot study with two managers that is not part of our sample. As a result of the refinements in this theoretical research validated and reduced researcher’s bias when interpreting the data. Accordingly, this study adopts five dimensions, including culture, management, how the SMET members get the information, employees relation and innovation performance, in the construct of Mintzberg 5P strategic practices. The 5Ps are not mutually exclusive, can show evidence of more than one interpretation of strategy [14].

Data Sample

We observe the necessity to maintain SMET manager’s effort on customer and market requirements. Each manager has a lot of daily routine functions, concentrate in commercial, human resources, and financial areas. Supervising teams, managing people and teams, audit, quality management and technical assistance activities are not attributed of these managers. SMET has heterogeneous cognitive ability to leadership and formulate innovative ideas. At the same time, it has difficulties to implement the communication between managers and employees.

The group has an average age of 32 years, 15.38% occupy the position of IT manager and 84.62% are directors. The average age of the companies operated by them is 13.1 years, and the time that these managers are working in these companies ranged from 1 to 22 months. The current number of employees has average of 38 people per SMET.

According to the SMET sample, 69.2% do strategic planning: the managers, themselves, conduct internally 53.8% of this and 15.4% are out-sourced to consultants. These SMET review the planning annually or quarterly.

The others, which do not develop strategic planning (30.8%), because: are unfamiliar with the technique, time priority to their customers; have internal structuring process. The main activities to develop strategic planning are: 15.38% SWOT analysis, 23.08% drawing up of the mission and vision and 61.54% controlling, monitoring or implementing the strategy. About 76.92% of SMETs analyse the market as following: 29.4% examining the contact through correspondence with the directors, 29.4% SMET search on web sites, 5.88% draw up a marketing survey and 35.29% do it during the contact with clients. Employees are not involved in strategic planning; but, three of the companies consider this involvement fundamental.

The competitor analysis is performed by 69.3% of these companies: 33% study market changes and 20.83% from clients or competitor managers at events and meetings. The suppliers analysis is conducted by 53.8% of the companies, and 46.15% of SMETs do not do, because they are satisfied with the actual suppliers. However, in companies that do supplier analysis, 36.84% ask thirdparties for recommendations, 5.26% experiment for a period, 5.26% consult a member of staff, 21.05% carry out searches by phone. However, the stakeholders information is partly neglected, 53.8% consider the views of their clients, 30.77% their competitors and 23.08% their suppliers and the market.

4. Minzterg Propositions of SMET

Strategy can be analysed by the manager’s view [36]. In this sense, we compare characteristics of the SMET managers according to the strategic view of Mitzberg, to him there are a large number of studies to prove that executive’s activities are characterised by brevity, variety and discontinuity and strongly oriented to action, and no inclination for reflection activities [36,37]. Appendix 1 compare 5P Minzterg’ propositions of each case study. The results show the mental evidence as a strategic perspective was that they expect that the organisation’s activities will follow from what was drawn up when planning according to the leadership style [14,36]. The development of strategic planning in the companies is not a static process, since 92.31% of the respondents of them analyse the market and use this to compose their market such that the characteristic of improving the organization’s relationship with the market. Allied to this, SMET identifies a set of strategic internal practices to elicit the willingness and motivation of employees to engage them to develop organizational expertise for business objectives [38] while contributing to improve the organisation’s relationship with its employees and promoting a collective awareness. These factors give dynamism to the design a clear direction for a SMET’s market position, and the possibility of constantly alternative strategies changing, without losing the final goal established by the SMET.

Information flown from executives suggests that they are influenced by external sources and are defined as the ability to organise people and resources to meet organizational objectives. But, Mintzberg [7,14] found that most of managers not have enough time to think strategically, they lost their time doing routine activities, such as calling, reading long reports, including ritual and ceremonies, trading and processing of small details that connect the organisation to its environment. However, the stakeholders and employees information is neglected, and some negative characteristics can contribute to SMET becoming vulnerable to the market risks, such as: lack of future vision; lack of time and resources, difficulty in establishing, monitoring and tracking the company’s goals; employees lacking commitment. The boundaries between the activities described will vary in each company used as a case study, in some cases there was the juxtaposition of functions due to the characteristics of the organization itself. In this sense, strategic planning becomes important for each organization.

The development of SMET strategic planning lies to improve the organization’s relationship with the market and with the future vision. SMET managers report that have difficulty to monitoring and to controlling strategies and their visions for stakeholders and employees [26]. Establishment of a shared ambition, development of collective identity and ability to give personal meaning, managers have to prompt the organisation to be on better strategic position. They claim mutual trust of SMET employees, vertical relationship between their superior and subordinates and horizontal interactions across functions to develop a feeling of empowerment and commitment [38] among multi-skilled employees. To Rumelt [39] a result of individual initiative and mutual cooperation can protect organization from the structural limitation, global competition, market risk and technological innovation competition and shorter product or service life cycles on their products or services.

We observed in Appendix 1, companies 1, 10 and 11 classified as Planning systematic proposition. These SMET analyses the external set of forecasts made about future conditions an internal environment by the study of strengths and weakness, to be able to control the environment. The process of evaluation are based on returnon-investment, competitive strategy valuation and risk analysis. It lends themselves to development those strategies and to reduce internal ambiguity [39]. The employee’s commitment to achieve strategic planning goals is important issue to the SMET managers. Surveys to analysing the scope and focus of the external course are done to integrate and to provide better service, and to support strong and visionary leadership.

Companies 4 and 13 can be described as Position proposition, because the main role is market domain where resources are concentrated with a root strategy [40]. The strategic planning is composed by three stages: formulation, implementation, and control. The managers learn with their internal reflection of their past decisions (right and wrong). Particularly useful in early stage of strategy development, when date must be analysed, those companies survey customers through marketing research. Regarding the activities of the competition they are also monitored through their Web sites, newspapers and magazines. Their suppliers also undergo an assessment, through experimentation of services and/or products for a certain time. Companies 2, 3, 7 and 9 are target as Pattern proposition. Strategy promotes action coordination, focus on SMET direct effort emerges from past organizational behaviour to improvise actions to support the strategic intent. The managers have fear to promote new strategies, focuses on short term results. Companies 5, 6 and 8 can be described as Perspective systematic proposition. SMET culture encourages innovation from employees. Managers conduct a strategic planning, based on SWOT analysis, with an interconnect relationship with employees and stakeholders. The leadership is more democratic, internal and external information are used to improve SMET performance. And company 12 described as Ploy systematic, because the strategic planning takes into the direct competition, where threats and various other manoeuvres are employed to gain advantage.

These results demonstrate that each perspective can be used to structure theoretical arguments that explain significant levels of variation SMET strategic performance.

5. Discussion

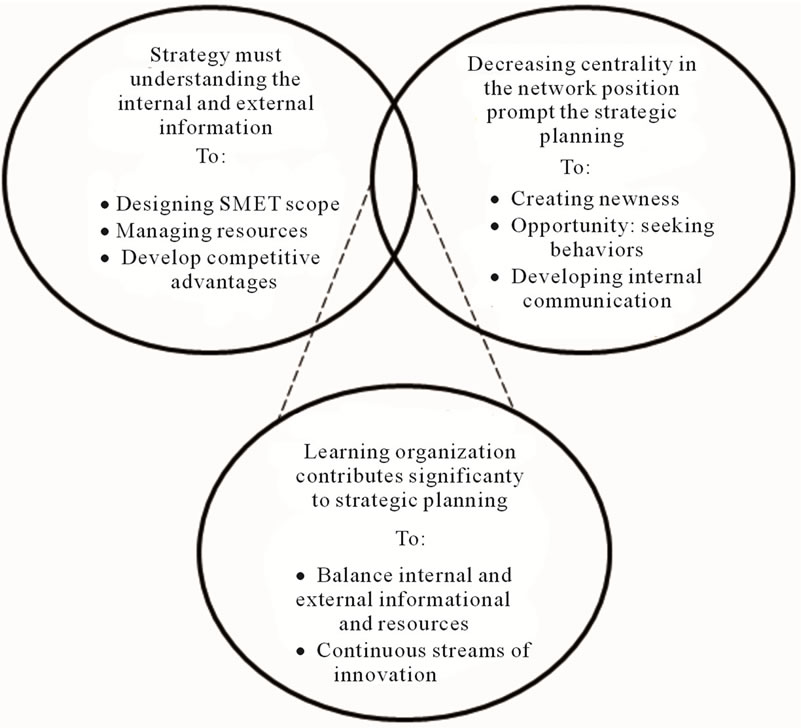

The findings suggest that in the context of strategic planning, assumptions on managers’ behaviour, network position, and the sequence of learning processes need to be considered. It enriches the theoretical knowledge on relationships between learning processes, strategic, new ideas, innovation, skills of managers and employees commitment. In order to explain how the necessary knowledge for strategic innovation is need, SMET must provide an understanding of how learning processes and combinative capabilities contribute to develop the strategic planning. The Management Capabilities influence the SMET Performance though internal and external important capabilities as showed in Figure 1. While the enterprise performance can be measured by various results: 1) financial; 2) human resource (employees and SMET managers); 3) organisational effectiveness. However, Enterprise Performance is a perceived out-come of customer satisfaction, determined by the adequate use of SMET resources.

Figure 1. Propositions of the SMET strategic planning.

In the Figure 1 we observed three propositions of the SMET strategic planning, its effects refer to constraints which are necessary for taking advantage of the exploratory learning processes. A strong formalisation of knowledge sharing of problem-solving needs higher cognitive diversity, and horizontally decision-making authority. A number of factors affect the firm competes in a fast-cycle market. Few of today’s firms have been able to achieve an effective balance between internal and external information. Effective analyses of external (emerging trends in the technological, socio cultural, economic, political/ legal, demographic, and global arenas in which the firm competes) and internal environments are the foundation for discovering an ideal balance. Each firm has unique resources and capabilities, and different customers. The information drifted from them explain how and when SMET can do a service or product with their scarce resources. Based on the above discussion, we offer the first proposition: Proposition 1. Strategy must understand the internal and external information.

SMET should incorporate in their strategies, the sustainable development in two competitive ways. First, by altering the price structure of more efficient and flexible strategic actions [41] and second by enabling the creation of better IT services of greater quality. From this point of view, SMET should concentrate in the incentive schemes, to encourage skilled individuals to link their effort and compensation [23,42]. We believe that incentives will increase the ability of SMET to engage its members in innovative strategic actions. The exploration occurs when integrates diverse knowledge with existing knowledge stocks of their members, the staff skills would guide them to act in a sustainable way [38]. But, values cannot be imposed top-down, should emerge from the SMET staff. Hansen [43] believes that knowledge and culture can be shared to establishing a common language.

Therefore, Proposition 2: decreasing centrality in the network position prompt the strategic planning. According to Mookherjee [44] decentralization of authority enhances the potential effectiveness of a firm’s exploration behaviours in that it makes it possible for the firm to examine a relatively large number of potentially attractive opportunities. Spreading power of making decision to the lower SMET levels. It will be possible for organizations to implement quickly and efficiently decisions; also minimizes the need for extensive tools to the internal communication.

SMET practices adapting internal requires an array of newness in the form of innovations to prompt the strategic planning. Absorbing new knowledge to which the firm gains access while exploitation new strategic actions. Consequently, will be difficult for competitors to imitate SMET’ new ideas. Under such conditions, learning processes are preceded by an assimilation of the newly acquired knowledge. It continues internal with the staff interacts from combinative capabilities of SMET members. SMET members capabilities and aspirations transforming their knowledge in strategic actions. Furthermore, this factor supports the Proposition 3: Learning organization contributes significantly to strategic planning. People continually expand their capacity together to create the results while they expansive patterns of thinking. SMET need to discover how to tap people’s commitment and capacity to learn [45]. The strategy needs all organizational functions developed in effective and integrated way [42]. Nonaka [46] recommended the use of metaphors and organizational redundancy to encourage dialogue to understand new ideas.

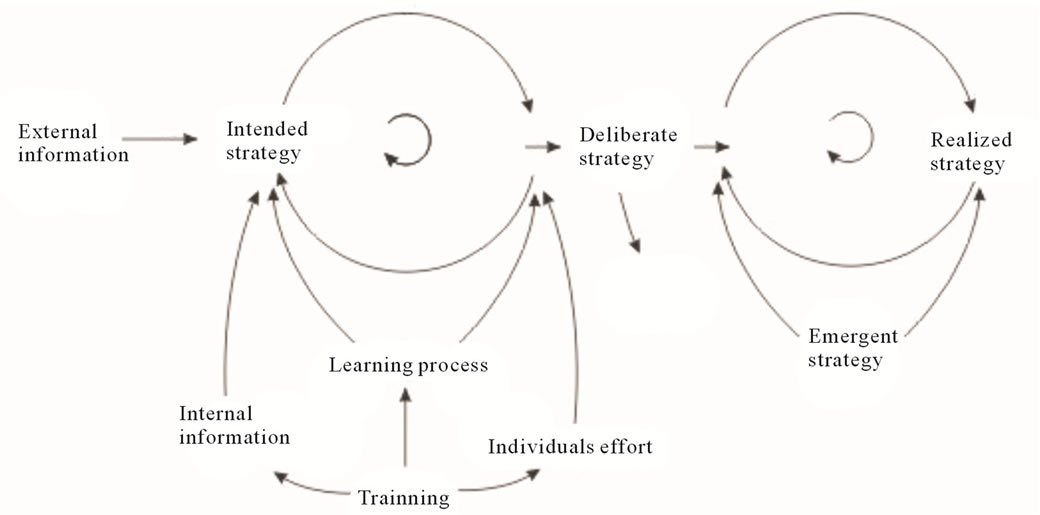

The key reasons for strategic planning, described in Figure 2, have success include managers and employees with significantly correlated with job satisfaction, effective leadership [47], support from the SMET employees, understand the customer’s changes requirements [48], the organizational size, complexity and resource constraints [49] and effective communication.

Those propositions of this study describes success and failure of strategic planning with the attitudes and perspectives of manager, and their potential to better understand SMET structure, culture and organizational resource constraints.

Therefore, the implementation of strategic planning has key strengths, such as: improves communication; promotes a collective awareness; increases the ability to take managerial decisions; improves the delegation of tasks; guides internal improvement programs; improves the relationship of the organisation with employees, improves the organisation’s relationship with the market; and prompts a company’s future vision.

6. Conclusions

The discussions of SMET companies, management’s comments and responses, revealed new [14] information which was incorporated in Mintzberg view. As the intersection between strategic management’s focus on exploiting competitive advantages and manager’s to SMET efforts to outperform competitors [36,48]. In this way an approach for each manager cognitive style can be developed by typically working through three steps: 1) behaviour to explore for opportunities, we believe that strategic planning captures a set of organizational actions with the capacity, training, and organisational learning contribute exchange of vision; 2) negotiate agreement; and 3) negotiate trust. “It involves individual cognition and social interaction, cooperation as well as conflict and all of this must be in response to what can be a demanding environment”, according to Mintzberg [7,14,36]. This allows

Figure 2. SMET organisational strategy performance model.

an assessment of whether or not there is a viable alignment between the mutual interests of SMET members. The process of strategic support requires constant effort and the search for agreement on the innovation applies to both internal and external people.

The practical implications of our findings can be viable to managerial recommendations for determining the relative importance of learning processes and combinative capabilities for SMET develop the strategic planning. The frequency with which it is performed or reviewed guarantees the market barriers that may arise suddenly or can stand out and make a contingency, achieving a competitive advantage that ensures success for organisations. But, the most of routine activities are performed by managers, it reduces their time to plan strategic actions Managers should become aware of the fact that strategic results need a good coordination capability through enhancing participation in decision-processes, and increasing internal communication. And, connectedness to different external knowledge sources from their stakeholders.

Despite the managerial and theoretical implications, this study has some limitations. As with any qualitative research, we cannot ensure complete observation of 13 SMET, just on the phenomenon studied [50]. The first limitation is the individual response can represent the deliberate firm-level situations, due to the self-selection behaviours, emerging from the fact that not all firms are perfectly free to do their knowledge management and human resource practices choices given the particular contingencies they face [51]. To alleviate this problem, this study asks the executives who are familiar with the topic to complete the questionnaire.

We used only qualitative measures to capture three propositions of SMET strategic planning. Such qualitative measures may be subject to research bias. Future research should, therefore, develop more quantifiable measures for testing our findings through quantitative data. The last limitation is the use of a cross-sectional research design. We chose the 13 cases for reasons of appropriateness, rather than of representativeness [52]. We provided a rich description of these 13 cases of studies which other researchers and managers can evaluate the SMET managerial contexts. Future research might using longitudinal design to drawing causal inferences.

To conclude, human resources are valuable assets for firms desiring to achieve superior innovation and sustainable competitive advantages. The viewpoints of this study highlight the crucial importance of the knowledge management capacity when examining the relationship between strategic practices and innovation performance.

7. Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this paper. This study is part of research funded by the Brazilian Research Council (CNPq).

REFERENCES

- H. Mintzberg, “Five Ps for Strategy,” In: H. Mintzberg and J. B. Quinn, Eds., The Strategy Process, PrenticeHall International Editions, Englewood Cliffs, 1992, pp. 12-19.

- W. D. Bygrave, “The Entrepreneurial Process,” In: W. D. Bygrave and A. Zacharakis, Eds., The Portable MBA in Entrepreneurship, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2004.

- N. J. Lindsay, “Toward a Cultural Model of Indigenous Entrepreneurial Attitude,” Academy of Marketing Science Review, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005, pp. 1-18.

- P. E. Petrakis, “Risk Perception, Risk Propensity and Entrepreneurial Behaviour: The Greek Case,” Journal of American Academy of Business, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2005, pp. 233-242.

- P. Westhead, D. Ucbasaran and M. Wright, “Decisions, Actions, and Performance: Do Novice, Serial, and Portfolio Entrepreneurs Differ?” Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2005, pp. 393-417. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2005.00144.x

- V. Hanna and K. Walsh, “Small Firm Networks: A Successful Approach to Innovation?” R&D Management, Vol. 32, No. 3, 2002, pp. 201-207. doi:10.1111/1467-9310.00253

- S. Carlson, “Executive Behaviour,” Stockholm, Strömbergs, 1951.

- H. Mintzberg, “Managerial Work: Analysis from Observation,” Management Science, Vol. 18, No. 2, 1971, pp. 97-110. doi:10.1287/mnsc.18.2.B97

- V. J. García-Morales, F. J. Lloréns-Montes and A. J. Verdú- Jover, “The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Organizational Performance through Knowledge and Innovation,” British Journal of Management, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2008, pp. 299-319. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00547.x

- T. Kiessling, G. Richey, J. Meng and M. Dabic, “Exploring Knowledge Management to Organizational Performance Outcomes in a Transitional Economy,” Journal of World Business, Vol. 44, No. 4, 2009, pp. 421-433. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2008.11.006

- W. M. Cohen and H. Sauermann, “Schumpeter’s Prophecy and Individual Incentives as a Driver of Innovation,” In: F. Malerba and S. Brusoni, Eds., Perspectives on Innovation, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2007. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511618390.006

- N. Foss, “Alternative Research Strategies in the Knowledge Movement: From Macro Bias to Micro-Foundations and Multi-Level Explanation,” European Management Review, Vol. 6, No. 1, 2009, pp. 16-28. doi:10.1057/emr.2009.2

- J. Galende and J. M. De La Fuente, “Internal Factors Determining a Firm’s Innovative Behaviour,” Research Policy, Vol. 32, No. 5, 2003, pp. 715-736. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00082-3

- D. Foray and E. Steinmueller, “The Economics of Knowledge Reproduction by Inscription,” Industrial & Corporate Change, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2009, pp. 299-319. doi:10.1093/icc/12.2.299

- G. Hamel and C. Prahalad, “Strategy as Stretch and Leverage,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 71, No. 2, 1993, pp. 75-84.

- R. Yin, “Case Study Research Design and Methods,” Sage Publications, London, 2003.

- J. Corbin and A. Strauss, “Basics Qualitative Research,” SAGE Publications, London, 2008.

- T. Besley and M. Ghatak, “Status Incentives,” American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 2, 2008, pp. 206-211. doi:10.1257/aer.98.2.206

- C. B. Cadsby, F. Song and T. Francis, “Sorting and Incentive Effects of Pay for Performance: An Experimental Investigation,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, No. 2, 2007, pp. 387-405.

- J. Dow and C. C. Raposo, “CEO Compensation, Change, and Corporate Strategy,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 60, No. 6, 2005, pp. 2701-2727. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00814.x

- M. Peng, T. Buck and I. Filatotchev, “Do outside Directors and New Managers Help Improve Firm Performance? An Exploratory Study of Russian Privatization,” Journal of World Business, Vol. 38, No. 4, 2003, pp. 348-360. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2003.08.020

- G. Friebel and M. Giannetti, “Fighting for Talent: RiskTaking, Corporate Volatility and Organization Change,” Economic Journal, Vol. 119, No. 540, 2009, pp. 1344-1373.

- P. Senge, “The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization,” Doubleday Currency, New York, 1990.

- N. S. I. Karthik, “Learning in Strategic Alliances: An Evolutionary Perspective,” Academy of Marketing Science Review, Vol. 6, No. 5, 2002, pp. 1-14.

- I. Nonaka and H. Takeuchi, “The Knowledge-Creating Company,” Oxford University Press, New York, 1995.

- M. Holloway, “How Tangible Is Your Strategy? How Design Thinking Can Turn Your Strategy into Reality,” Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2009, pp. 50-56. doi:10.1108/02756660910942463

- V. Sambamurthy, A. Bharadwaj and V. Grover, “Shaping Agility through Digital Options: Reconceptualising the Role of Information Technology in Contemporary Firms,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 2, 2003, pp. 237-263.

- M. Wade and J. Hulland, “The Resource-Based View and Information Systems Research: Review, Extension, and Suggestions for Future Research,” MIS Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2004, pp. 107-142.

- K. M. Eisenhardt and S. L. Brown, “Competing on the Edge: Strategy as Structured Chaos,” Long Range Planning, Vol. 31, No. 5, 1999, pp. 786-789. doi:10.1016/S0024-6301(98)00092-2

- A. Cottam, J. Ensor and C. Band, “A Benchmark Study of Strategic Commitment to Innovation,” European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2001, pp. 88-94. doi:10.1108/14601060110390594

- J. Adair, “The Challenge of Innovation,” The Talbot Adair Press, Surrey, 1990.

- P. Drucker, “Theory of the Business,” Harvard Business Review, Boston, 1994, pp. 95-106.

- J. Brannen, “Working Qualitatively and Quantitatively,” In: C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium and D. Silverman, Eds., Qualitative Research Practice, Sage, London, 2004.

- S. Kvale, “Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing,” Sage, Thousand Oaks, 1996.

- A. Strauss and J. Corbin, “Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques,” Sage Publications Inc., Newbury Park, 1990.

- H. Mintzberg, B. Ahlstrand and J. Lampel, “Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Management,” Prentice-Hall International Editions, Englewood Cliffs, 2002.

- T. R. Zenger, “Explaining Organizational Diseconomies of Scale in R&D: Agency Problems and the Allocation of Engineering Talent, Ideas, and Effort by Firm Size,” Management Science, Vol. 40, No. 6, 1994, pp. 708-729. doi:10.1287/mnsc.40.6.708

- S. Ghoshal and C. A. Bartlett, “Linking Organizational Context and Managerial Action: The Dimensions of Quality of Management,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 5, 1994, pp. 91-112.

- R. Rumelt, “Strategy, Structure, and Economic Performance,” Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 1974.

- T. McNichols, “Executive Policy and Strategic Planning,” McGraw-Hill, New York, 1983.

- V. Capkun, A. P. Hameri and L. A. Weiss, “On the Relationship between Inventory and Financial Performance in Manufacturing Companies,” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 29, No. 8, 2009, pp. 789-806. doi:10.1108/01443570910977698

- M. Saad, “Development through Technology Transfer,” Intellect Books, Bristol, 2000.

- M. T. Hansen, “Knowledge Networks: Explaining Effective Knowledge Sharing in Multiunit Companies,” Organization Science, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2002, pp. 232-248. doi:10.1287/orsc.13.3.232.2771

- D. Mookherjee, “Decentralization, Hierarchies, and Incentives: A Mechanism Design Perspective,” Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 44, No. 2, 2006, pp. 367-390. doi:10.1257/jel.44.2.367

- P. M. Senge, “The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization,” Doubleday Currency, New York, 1990.

- I. Nonaka, “A Dynamic Theory of Organizational Knowledge Creation,” Organization Science, Vol. 5, No. 1, 1994, pp. 14-37. doi:10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- M. A. Adeniyi, “Effective Leadership Management: An Integration of Styles, Skills & Character for Today’s CEO,” Author House, Bloomington, 2007.

- M. E. Porter, “Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analysing Industries and Competitors,” The Free Press, New York, 1980.

- O. Moen, “The Relationship between Firm Size, Competitive Advantages and Export Performance Revisited,” International Small Business Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1999, pp. 53-72. doi:10.1177/0266242699181003

- Y. S. Lincoln and E. G. Guba, “Naturalistic Inquiry,” Sage Publications, Inc., Beverly Hills, 1985.

- B. H. Hamilton and J. A. Nickerson, “Correcting for Endogeneity in Strategic Management Research,” Strategic Organization, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2003, pp. 53-80. doi:10.1177/1476127003001001218

- M. Miles and A. M. Huberman, “Qualitative Data Analysis,” Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, 1994.

Appendix

Appendix 1. SMET Mintzberg’s 5Ps Strategy.