iBusiness

Vol.2 No.2(2010), Article ID:1951,10 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2010.22013

Theory and Practice of the Design of Monthly Reports

Theory and Practice of the Design of Monthly Reports

Bernhard Hirsch, Anne Paefgen, Sven Schaier

![]()

Universität der Bundeswehr München, Neubiberg and WHU - Otto Beisheim School of Management, Vallendar, Germany.

Email: bernhard.hirsch@unibw.de, {anne.paefgen, sven.schaier}@whu.edu

Received January 20th, 2010; revised March 10th, 2010; accepted April 17th, 2010.

Keywords: Recipients of reports, design of reports, field study, provision of information, monthly report

ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on the design of management reports. Based on theoretical considerations concerning the personal information demand, hypotheses were developed and tested in a field study in German major enterprises. The findings from the field study show a high diversity of monthly reports to the top management. Furthermore it is shown how design improvements for these reports can be derived from the personal information demand of the recipients. The paper will also discuss deficits of the reporting system during the study.

1. Introduction

Providing management with information is one of the key tasks of management accounting (controlling). Numerous approaches to define management accounting do focus on the supply of information as the core task of management accounting [1-5], and empirical studies do confirm that substantial resources of management accounting are required for this key focus [6,7].

Within the framework of the information supply, the internal corporate reporting system plays an outstanding role [8-11]. Information collected and processed by corporate information systems are usually passed on to management in the form of reports, with the corporate information system comprising the preparation and transmission of information in the form of reports to employees, primarily to the leaders of an enterprise [12]. The corporate information system essentially supports the business-related decision-making processes [8].

As a consequence, shortcomings in terms of the conception of the information supply frequently only become apparent at the reporting stage, and moreover, successful results achieved within an otherwise well designed information supply are still susceptible to threat at this point. Reporting, to be understood as the entirety of reports directed to internal addressees of a corporation, may thus be viewed as the point of crystallization of information supply.

The science of business economics puts numerous demands on the design of reports. As a rule, the core idea behind these demands is to provide the recipients of reports the information they need to facilitate decision making [13]. So far only few studies have investigated the extent to which these demands are actually implemented in corporate practice. Göpfert [8] thus sees the need for research on the reporting sector. Moreover, up to now only few studies exist which investigate the structure of reporting [14].

Therefore, on one hand, this paper aims at illustrating the current status of the (monthly) reporting system in selected large German corporations, with the focus of the field study being the monthly report sent to the members of the board by corporate management accounting. All heads of corporate management accounting of the companies investigated agreed to rate the monthly report as one of the five most essential “products” of their respective departments. On the other hand, proceeding from this stocktaking, theory-based evaluations of the practice of the design of monthly reports are to be carried out from which suggestions for improvement will be derived.

The paper is structured as follows: The following section starts by developing the conceptional basis of the examination. First, the need for information is identified as the theoretical starting point for the design of the information supply and the reporting system. Based on conceptional considerations, hypotheses are derived which were empirically plausibilized within the framework of the field study. Afterwards the principal options for the design of the reporting system are shown. In the third section, the results of the empirical study are illustrated by first describing the further details of the methodology used for the study, followed by the presentation of the results of the field study in two steps: The reports examined are described by means of the design aspects as described in the second paragraph. In a second step, the procedure used for the evaluation of the reports and the assessment of possible options for improvement is described. Since the study is focused on only seven corporations, the empirical results can therefore not be claimed to be representative. Nevertheless, in our opinion, they are a valuable theory-based contribution beyond mere exploration, supporting the empirical plausibilization of theoretical considerations based on the reporting practice applied in large German corporations. Since the suggestions for improvement are basically corporate-specific, the relevant statements concentrate on the commonalities found in all corporations. In winding up, the fourth section summarizes the most important results in a resume.

2. Development of a Conceptional Frame of Reference

2.1 The Need for Information as the Starting Point for the Design of the Reporting System

The need for information by the addressee of the report represents the theoretical starting point for the demand of an information supply and its design. The need for information can be generally defined as the “sum of information required for the fulfillment of an informational interest” [15]. The goal of the information supply is to satisfy this need for information in the best possible way.

For the concretization of the information need it would be suitable to distinguish between an objective and a subjective need for information [16].The objective need for information results from the tasks fulfilled by the recipients of the information. In the event that the recipients of the information are primarily assigned routine tasks, there is only relatively little objective need for (new) information. However, for the accomplishment of tasks where problem-solving or decision-making skills are of central importance, the objective need for information often strongly increases. Thus – depending on the task to be accomplished – information such as details of the market environment, decisions taken in other parts of the corporation or available capacities is needed [5]. The more comprehensive the tasks to be fulfilled, and the more freedom is allowed for their accomplishment, the more difficult it is to directly define the required need for information by the mere formulation of the task.

While the objective need for information is solely derived from the formulation of a task, thus being defined independently by the individual person, i.e. the recipient of the information, the subjective need for information also considers the individual capabilities and the attitudees of the recipients of the information [13,17]. The abilities of an information recipient may primarily be concretized in view of his or her (professional) experience and his or her cognitive abilities. It must be assumed that the information recipients are limited as far as their processing capacities are concerned, however are capable to extend these capacities because of their experience [18,19]. The attitudes of an information recipient do affect his or her opinions and perceptions as to which information he or she wishes to obtain or requires to accomplish the task. There are certain factors that play a role for the subjective information need, such as the risk-taking characteristics of an information recipient and the question if he or she is more number-oriented or rather averse to numbers. The kind of how information is taken in by someone also has an effect on the subjective need for information.

The following sections are intended to examine if and to which extent the design of the reporting system should be primarily oriented towards one of these two components of information need. Two aspects are to be taken into consideration which will both be described below: First, the degree to which the respective need for information can be assessed and second, the interaction between controllers and managers regarding the design of the reporting system.

As far as the methods used to assess the need for information, a distinction is made between the deductive and the inductive assessment [20]. Within the framework of the deductive assessment of an information need, either logical analyses of the task or problem are used to determine who the recipients of the information are, or model analyses are used to assess the objective information need of the information recipients. As already mentioned, in practice, the assessment of the objective information need is especially difficult in such cases where the formulation of a task is characterized by high complexity and where considerable freedom is allowed to accomplish the task. However, this is exactly what especially applies to the relevant tasks to be accomplished by the members of a corporate board. Also to be taken into consideration are the theoretical arguments which have already been outlined, i.e. that both the abilities and the wishes or requests of the recipients are different regarding the design of a report. If the wishes expressed by the recipients of the reports are interpreted as their individual preferences, individual aspects regarding the design of reports must by no means be neglected, according to the principle of the economic theory: “De gustibus non est disputandum”.

This theory favors an inductive approach to assessing the information need, with the goal to identify the subjective information need based on the information demand by the recipients of the information. Thus, the situation-dependent settings are automatically considered in view of both the available sources of information and the information behavior of the recipients of the information. First conclusions on the subjective information need may be drawn on the basis of an analysis of the existing documents and information systems within a corporation. Another option is to observe the information behavior of the recipients of the information as well as to interview them. Interviews are the most direct option to assess the subjective information need. Since, as a rule, it must be assumed that managers themselves have the best overview of their tasks, problems and decision-making situations, the two last mentioned approaches are especially suitable to assess the information need of the management. In view of the difficulties of a deductive assessment of the objective information need of managers it must be assumed that such an inductive approach also represents a good basis for the assessment of the objective information need. Thus, a detailed survey of the information need should be based on the observation of the behavior (regarding the information demand) of the recipients of reports, as well as on interviews with the recipients.

A consequent orientation of the information supply towards the subjective demands of the recipients of the information will affect the interaction of controllers (as the suppliers of information) and managers (as the recipients of information). If management accounting is assigned the task to provide adequate information to the management, it is very obvious to interpret management, as the recipient of the service “information supply”, also as an (internal corporate) client of management accounting. Existing empirical studies investigating the customer orientation of cost calculators however give reason to assume that the idea of an internal customer orientation has often not yet been internalized by management accounting, while information supply is strongly approached through the information offer in the form of technical information systems [21,22].

In spite of the high significance which, for conceptional reasons, has been acknowledged to the subjective assessment of the quality of monthly reports by the recipients , it must be mentioned that this view does not exclude the fact that, within the framework of the reporting system, controllers should also have the right to make suggestions or to express disagreement. Such positioning of management accounting in the sense of a critical counterpart [23] becomes especially necessary if the information demand evidently differs from the objective information need. On one hand, such right to express disagreement requires the manager’s confidence in the competence of the controller. On the other hand, the fulfillment of the counterpart function within the reporting system requires detailed knowledge as to how and for what purpose managers use the supplied information. Such knowledge may be particularly won by a successful interaction between the controllers as the suppliers of reports and the managers as the recipients of reports. Through frequent exchange and attentive observation, controllers can learn to estimate the subjective and objective information need of the managers and counteract possible discrepancies. It also allows them to gain clues as to whether management may need other information, or if support is needed for the interpretation of the report information, or if the information supplied is perhaps not used for the intended purposes.

Based on the above conceptional considerations on the design of the reporting system, hypotheses are derived which underwent an empirical verification within the framework of the field study.

The first assumption is that the monthly reports in the examined companies are clearly different as far as their design is concerned since it must be expected that the recipients’ information need relevant for the design of the report will also greatly differ. Since the examined companies are active in different industrial sectors, pursue different business models and are also different as far as their internal organization is concerned, it must be expected that the objective information need of the management of these companies will differ from each other. Moreover the corporate management will probably show different abilities and attitudes which entail the assumption that the subjective information need will also be different. There are also other reasons, like the path dependence [24] regarding the design of information and report systems, leading to expect differences in the design of reports. Hence, the first hypothesis is that:

H1: The monthly reports in the examined companies do greatly differ in their design.

Second, it was derived that the design of the reports should primarily be oriented towards the subjective information need of the recipients of reports. Based on existing studies, it must be assumed that controllers strongly neglect the orientation towards the needs of their internal clients. These considerations are summarized as follows in the second hypothesis:

H2: The product “monthly report” which has to be established by management accounting does not sufficiently consider the needs of managers as internal clients.

In order to empirically verify the second hypothesis, the managers of the examined companies collected client requirements and client satisfaction data regarding the monthly reports they had received from management accounting. On one hand, this method allowed to verify if and to what extent the current monthly reports are oriented towards the needs and wishes of the recipients, and thus, towards their subjective information need. On the other hand, the results of this survey could be used to identify potentials for improvement in view of the reporting system of the examined companies. Common potentials for improvement found in all corporations also give a hint to typical deficits of the reporting system.

The basis for the verification of the first hypothesis was a comparison of the monthly reports in the various companies. The reports were examined in view of the design characteristics available for the design of the reports. The following section explains the design options that are available for the reporting system.

2.2 Design Options of the Reporting System

A report – and thus, a monthly report, too – can be described by the following design options [20]: Of great significance in view of the fulfillment of the information requirements, is (a) the purpose of the report. Personal design options refer to (b) the author of the report and (c) the recipient of the report. The time factor of the report is characterized by (d) the reporting date. Moreover, reports can be distinguished by different (e) types of reports. Finally, (f) the content and (g) the form offer the corresponding design options.

Ad (a): The purpose of the report is an essential aspect for the design of reports. There are five different purposes for a report: The superordinate purpose, especially for standard reports, is to inform the recipients of the report in the sense of a supply with “basic knowledge” of the business development. In more detail, this purpose of a report can be fulfilled by providing reports serving as brief information (“An overview of the essential key performance indicators”), and/or as a reference guide. A second essential purpose of a report is planning, where the information of a report is used to prepare decisions. Moreover, reports are frequently used for control purposes. Another purpose of a report is steering. The transmission of information leads to counter measures. The documentation purpose of a report basically follows the regulations of the external accounting and the Law on Monitoring and Transparency in Businesses (German: KonTraG). These regulations define certain types of information which have to be reported to the management [20].

Ad (b): Another design dimension of the reporting system is the author of the report (synonym: report bearer). The reporting system and, within this system, in particular the monthly report, is one of the core tasks or core products of management accountants (controllers). In corporate practice, controllers usually are the primary authors of reports [20].

Ad (c): The recipients of reports are the addressees. Since the definition of the reporting system used in this paper comprises the internal corporate transmission of information, the circle of the recipients is restricted to the managers of the company. Monthly reports are of particular relevance if they are presented to top management. Management takes decisions that have a particular effect on the success of a corporation. Apart from managers, other groups of employees, such as division managers are possible addressees of monthly reports [20].

Ad (d): The reporting date of a report is the time-related design aspect of reports, which for instance means the frequency of reports. The reporting date also includes the date of issue after the occurrence of a certain event.

Ad (e): If a reporting system is very sophisticated, various types of reports may be employed. Reports may be classified as standard reports, deviation reports and reports on demand. Standard reports are common use in corporate practice. They are written in regular intervals, at a certain point of time, for a certain circle of addressees and with a largely standardized content. Deviation reports do not follow any predetermined report cycle, instead they are triggered as soon as certain values either exceed or fall below a given threshold. Reports on demand required by the recipients in certain cases are the third type of reports [20].

Ad (f): The design of the content of a report may be further broken down into the features structure, objective of the information, type of information and related subject of the information. The structure of a report refers to its breakdown and the organizational units focused in the report. The facts captured in a report are - quite generally - called the objective of an information [23], including for instance, the decision taken due to the key performance indicators (KPIs) supplied in a report. By means of the dimensions of the Balanced Scorecard, these key performance indicators can be classified as finance, process, market/customer, employee and innovation KPIs [25]. Along with this classification, it is also possible to separate the KPIs into monetary (financial KPIs) and non-monetary (concerning all other categories of the Balanced Scorecard) KPIs. The type of information is intended to describe the character of the statements made on the objectives of the information. Possible types of statements include for instance fact-oriented, forecastoriented, explanatory or normative statements [23]. The explanatory power of information depend its subject relatedness. Only if data are related to each other, i.e. qualified, deviations can be deduced which can be analyzed and then deliver findings which are relevant in terms of steering and management accounting. In this context, the subject-relatedness of information is to be understood as those values that compared to the actual values. Typical reference values to be considered are past or forecast values.

Ad (g): The form of a report refers to aspects regarding the formal layout of a report. It can be broken down to design features that include the length or volume, the appearance and the presentation form. While the volume or length of a report simply refers to the number of pages of a report, the appearance means the number density, i.e. the number of figures per page, as well as the use of colors. For the presentation of the reported information tables, diagrams and comments can be used. Tables are an option to present a larger volume of data and are thus especially suitable for data rows and developments. Diagrams on the other hand allow an intuitive comprehension of the presented facts. It is important that the chosen type of diagram (e.g. columns, line charts, pie charts, or waterfall diagrams) best possible reflect the related facts. Additionally it may be useful to verbally formulate essential qualitative facts and findings and to add them as a comment [23].

3. Empirical Study

Based on conceptional considerations and the established hypotheses, the results of the empirical studies will be presented in this section. First, aspects regarding the methodology of the study will be described in further detail. Afterwards, the results of field study will be presented in two steps: First, the differences regarding the design of the monthly reports, which is the subject of hypothesis 1, will be examined. In a second step, the quality of the examined reports will be presented from the point of view of the recipients, and potentials for improving the reports will be shown (Hypothesis 2).

3.1 Methodology of Examination and Approach

The field study [26] presented in this paper was carried out in 2004. It examines the monthly report system of seven leading German enterprises which are active in different industrial sectors. The study is intended to facilitate the identification of the characteristics of the monthly reporting that are common in all companies. A commonality of all companies is their leading position in their respective market - all companies hold European and worldwide top positions.

An essential component of the study was the detailed comparison of the monthly reports supplied to the corporate management by management accounting. Due to the amount and high sensitivity of the information to be examined it was necessary to limit the scope of the sample inspection to these reports. Since the information contained in the reports is subject to confidentiality, the companies taking part in the study provided us reports from which one could read the type of information and the layout; however which did not contain any data.

In addition to the analysis of the documents, 22 personal interviews were held during the field study with both authors and recipients of reports of the companies involved. As authors of reports, management accountants (controllers) of the central management accounting department were interviewed. In order to gain the opinion of recipients, interviews with top managers of the corporate headquarters were held. Moreover, standardized questionnaires, which had been verified in pre-tests, were used in order to gain assessments regarding the monthly report of both the authors and the recipients on a broader basis.

3.2 Design of the Monthly Reports

Hypothesis 1 implies that, due to different requirements, monthly reports highly differ in their design. The following statements support this hypothesis in most parts. Since the study is focused on the examination of the monthly reports corporate management accounting supplies to the top management, the design aspects author and recipient, reporting cycle and type of report are similar in all examined reports. Nevertheless are there significant differences as to the purpose, form and content of the reports.

As far as the intended purpose of the report is concerned, it must be pointed out that in all companies, information is the superordinate purpose that prevails. This purpose of the report is however put into practice in different ways: In one of the companies of the study, the monthly report is mainly used as a reference guide, while the other companies primarily use it as a short overview of the current business development.

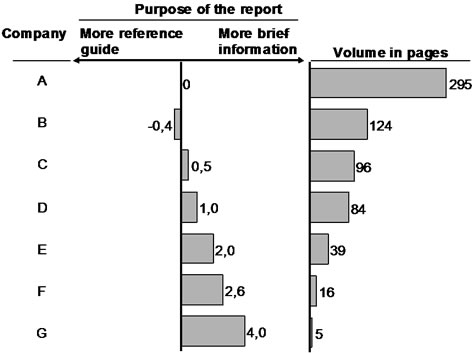

The form of the report, i.e. the volume of the reports as well as their design and presentation, highly differs. Regarding the determination of the volume or length of a report there seems to be a conflict between comprehensively informing the management and focusing the attention of the management on the key facts. This conflict is also mirrored in the analyzed reports (Figure 1). The volume of the reports ranges between 5 and 295 pages. Companies with a short monthly report in particular use this report primarily as a brief information (Point 4.0 on a total scale of 7). The company with the longest report by far, uses the report as both a reference guide and as a short overview of the current business development.

The components examined as the design features of the reports included the number density and the color design. The number density of the examined reports varies between 43 and 300 numbers per page. It is also noticeable that the number density is not proportional to the volume of the report. While the shortest report also shows the lowest number density, the second shortest report reaches the highest number density (with an average of over 300 numbers per page). The use of colors

Figure 1. Purpose of the report and number of pages

shows an incoherent picture. While three companies do without any color design, four companies make use of this option to make their reports visually appealing.

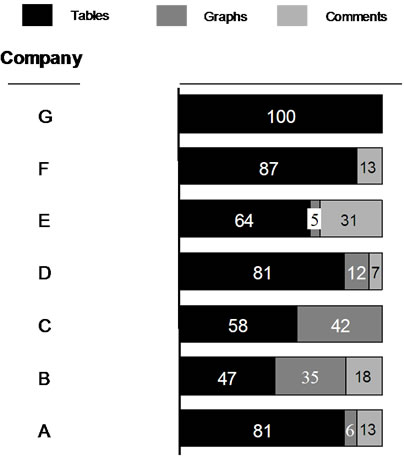

The last formal design feature to be mentioned is the form of presentation. As can be seen in figure 2, the use of the available presentation forms – tables, diagrams and comments – strongly varies. The analysis of the seven reports shows that a larger proportion of diagrams and comments are corresponding with a larger report volume.

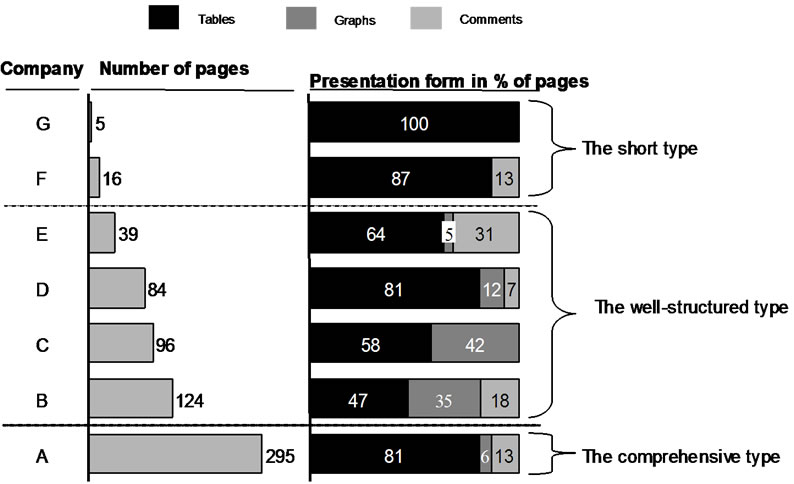

In summing up, the reports examined in the field study can be clustered in three groups according to their volume and presentation form – the comprehensive type, the short type and the well-structured type (Figure 3). Four out of the seven examined companies have developed well-structured monthly reports. Two companies write short reports. One monthly report may be characterized as comprehensive.

The design of the content of a report is subsumed under the features structure, objective of the information, type of information and related subject of the information. As far as the structure is concerned it must be emphasized that the structure of all reports corresponds to corporate structure. They start with an overview of the corporation before providing further details on the individual divisions. Four out of seven reports do have a table of contents. In addition to an organization-oriented structure, one company also reports according to geographical regions. A view on the organizational units focused in the reports shows that the proportion of information exploring the corporate level, the sub-group level and the product and sales level respectively do vary considerably. While one company uses 92% of the report content for data coming from decentralized corporate divisions, another company only uses 20% for such data.

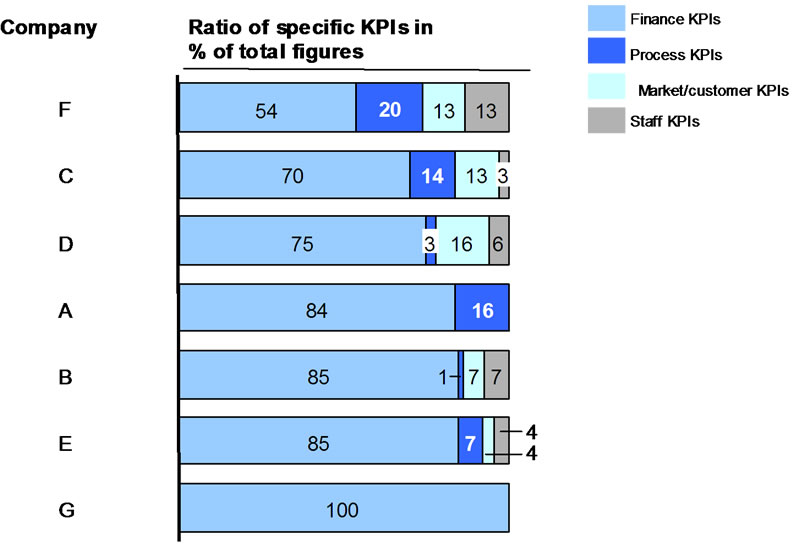

As expected, the financial key performance indicatiors (KPIs) prevail in all monthly reports as far as the objective of the examined information is concerned. With 54% to 100%, their proportional range is relatively high. The analysis of the reports resulted in the following illustration showed in figure 4.

The illustration demonstrates that financial KPIs do prevail in all corporations. However, the extent to which financial KPIs are prioritized does vary. While company G does completely without the report of non-financial KPIs, such figures account for almost half of the reported KPIs in company F. Among the non-financial KPIs, process KPIs often plays a prominent role.

Figure 2. Presentation form of the reports

Figure 3. Types of reports

Figure 4. Information objectives of the reports

The type of information was understood as the character of the statements made in the reports, i.e. if these statements tend to be fact-related, forecast-related, explanatory or normative. Fact-related in the sense of above said are all actual values represented in the reports. Forecast-related information can be found in the form of planning (budget) values and projections (forecasts). Planning values in the sense of target values may be also be understood as normative information. Comments frequently contain explanatory information. Depending on the design and structure of the content, they may also have a fact-related or normative character. Since fully writtenout comments were not available for the analysis, it is not possible to make any statements as to the proportion of the respective type of information in the reports.

The last content-related design feature to be described is the information relatedness of the examined reports. The information relatedness largely depends on the intended purpose of the report. The purpose of information in a report correlates with the dominance of actual values. However it is also possible to use projections for information purposes if they contain information about the current expectations. Projections can also be used for planning purposes, such as the determination of production capacities. The steering purpose of a report can be fulfilled by providing the most recent forecast values. For control purposes, parameters are needed in the form of planning values to compare them with the actual values. In all examined reports the actual values were compared with the corresponding values of the previous year. With the exception of one company, all companies continuously include planning values in their reports. Projections were found in only four out of the seven companies.

As a resume, it can be said that the analyzed reports show a great variance in terms of the relevant design features of the study. Hypothesis 1 may thus be affirmed by the empirical observations.

3.3 Evaluation of the Monthly Reports

In Subsection 2.1, it was formulated in hypothesis two that the monthly report as a “product” is not sufficiently oriented towards the needs of the managers, thus, as a consequence, not sufficiently satisfying the information need of the recipients. Above said must be verified by the evaluations of the interviews with the authors of the reports (controllers) and their clients (managers).

In the interviews held with the managers as the recipients of the reports they were also asked questions regarding their pattern of use, apart from questions concerning their information need. Additionally, a questionnaire with the same content was filled out by the authors of the reports who had been asked to assess the information need and behavior of the managers. This method allows a comparison of the statements made by the recipients with the assessment of the authors of the reports. Thus, it can be verified if or to what extent the authors of the reports are aware of the fact that their reports may possibly deviate from the ideal report design which should be oriented towards the subjective information need of the recipients; and if such deviations are accepted, for instance for financial reasons. Major deviations in the assessments also lead to the assumption that there is an increased need for communication between the recipients and the authors.

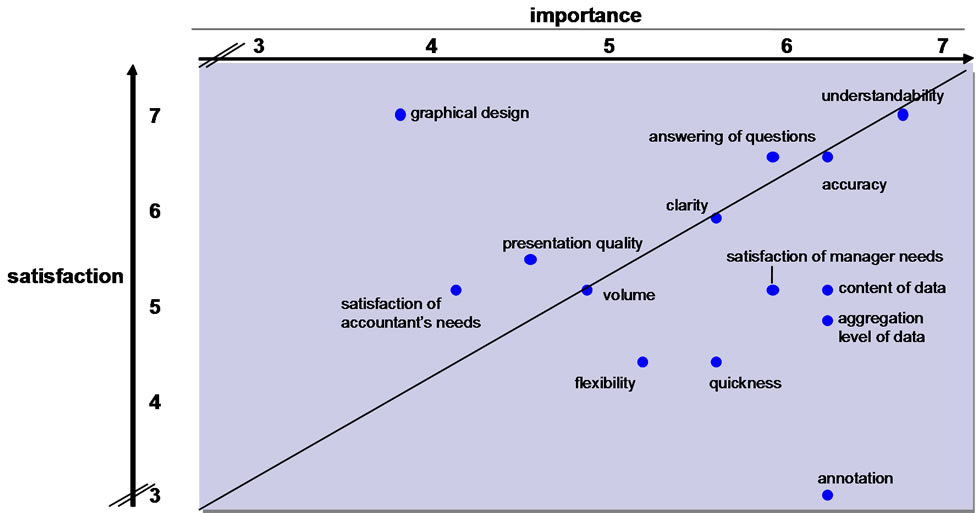

In marketing, the assessments of the importance of and the satisfaction with certain product features are compared in a so-called importance-satisfaction matrix, a widely used marketing instrument [27]. As a rule, the importance of a product feature is mapped on the horizontal axis and the corresponding value of satisfaction is mapped on the vertical axis. Starting from the hypothesis that the most essential quality features of a product also should be fulfilled to the best satisfaction of the customer, it follows that ideally, all points marked in the importance/ satisfaction matrix should be on or above the angle bisector starting from the origin of the coordinate system. Any criteria above the angle bisector may therefore be considered uncritical. In view of their importance, the satisfaction with these features is sufficient. The opposite applies for products below the angle bisector. The satisfaction reached is not sufficient considering the importance of the feature. The greater the distance of a point from the angle bisector, the more critical this aspect is evaluated by the recipient and the more urgent measures should be taken to improve the situation. The importance-satisfaction matrix is therefore an instrument to identify and visualize the fulfillment of the subjective information need of the recipients. The visualization offers starting points for the improvement of certain report features.

In the field study, the evaluations of the recipients regarding various content-related and formal design features of the monthly reports were inquired based on a scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 7 (very high) and then written into an importance/satisfaction matrix. Figure 5 shows the importance/satisfaction matrix for company B as an example.

From the illustration follows that the managers of company B receiving the reports are primarily dissatisfied with the key figures presented in the monthly report. They assess the importance of comments as very high; their practical implementation however does not meet their expectations. The volume of the monthly report as well as the replies to questions are however adequate from the point of view of the recipients. The graphic design as a quality feature is even over-fulfilled (as related to its importance).

Based on this exemplary approach shown for company B, specific deviations between the actual design of the reports and ideal design derived from the subjective information need of the recipients could be found in each of the companies - a fact indicating potential for improvement. For instance do the monthly reports of companies C and F do not meet the needs of the managers, especially as far as their structural overview is concerned. Company D has complaints concerning both the content and the kind of data reported. Moreover, the members of the board of this company explicitly criticize that the reports as designed by the management accounting department, do only insufficiently consider their requirements. Moreover, the parallel interviews held with questionnaires given to the authors of the reports makes it clear that their assessment of the information need of the recipients is distinctly different from the assessment of the recipients themselves. The potentials for improvement deviated from the interviews with the recipients were largely unknown to the authors of the report, instead, the authors saw other potentials for improvement than the recipients.

Figure 5. Importance/satisfaction matrix in relation to the monthly report of company B

Beyond the merely corporate-specific potentials for improvement some design aspects could be identified for which there is a need for improvement in all or at least most of the examined companies. This implies typical problems regarding the reporting systems in the examined companies. In all examined companies, the assessment of the annotation was “in the red” of the importance/satisfaction matrix. Further results from the questionnaires and the interviews indicate that on one hand, an increase of the proportion of comments is requested. On the other hand, the quality of the content of the comment needs to be improved, too. A first starting point for such improvement would be a more systematic use of comments; i.e. they should only be used for extraordinary facts or situations which are also of major economic relevance.

The features concerning the volume and graphic design, which were particularly positively evaluated in company B, also reached high satisfaction values in all other companies considering the importance attached to them. In spite of the broad diversification of the volume ranging from 5 to 295 pages, the volume seems to be well adjusted to the subjective need of the recipients. Also, the graphic design apparently is not an issue regarding the question if there should be a fixed portion of graphics, since this varies between 0 and 42%. The authors of the reports seem to have developed a good feeling for the needs of the recipients.

In winding up, it can be said that the examination of the subjective information need and in particular, the application of the importance/satisfaction matrix as a marketing instrument helped reveal potentials for improvement for the individual monthly reports that were examined within the framework of this field study. The results supports the assumption formulated in hypothesis two, i.e. that the product “Monthly Report” established by management accounting does not yet sufficiently consider the needs of managers as internal clients.

4. Conclusions

The existing field study provides an overview of the current situation of the internal monthly reporting to the management of some selected large German companies. The field study examined the monthly reports of seven companies. Additionally, interviews were held in these seven companies. Due to the limited scope of sample inspections no universally valid statements can be made based on these data. Nevertheless, in our opinion, the existing study bears a large heuristic potential which should be verified in future large-number studies. However, this approach is probably not easy to put into practice, due to the sensibility and complexity.

The field study could show that the monthly reports in the various companies do have different designs. Possible reasons for this variability in the design could be the orientation of the report design towards the situationdependent environment, but also other factors, like a historical path-dependence of the design.

However, a consequent and systematic orientation of the report design towards the different information needs of the recipients does apparently not exist. Within the framework of the field study, the analysis of the subjective information need of the recipients showed that the current design of the monthly reports deviates from the ideal design which can be derived from the subjective information need. It was thus possible to show corporatespecific potentials for improvement for all companies examined in the field study.

Moreover, some potential for improvement applying to all companies could be ascertained for the reporting system. The current state of annotations and comments is particularly criticized in all examined companies. There are various reasons that may cause difficulties for controllers writing comments. It may be that controllers are more familiar with quantitative information in the form of numbers, thus having problems with a verbal presentation of qualitative information. Moreover, the interviews held during the field studies also revealed that both time pressure and a lack of insight into the operative business to be commented make it difficult to write clear annotations or comments.

As a resume, it can be said that the results of the studies show that the orientation of the design of management reports towards the subjective information need of the recipient seems to be a promising approach to reveal potentials for improvement within the reporting system. By means of this approach which has been derived from this theoretical basis it was possible to show that management reports are not well-adjusted to the requirements and needs of their recipients, and moreover, that this approach helps gaining specific clues as to how to improve the design of a report. Also, the interviews held with both the authors and recipients of such report made it clear that the conception of management reports is frequently characterized by a “trial and error” process. A systematic communication between the authors and users concerning the structure of the reports hardly takes place. Above said supports the findings that this would be a starting point for an improved structural design of management reports.

REFERENCES

- F. Hoffmann, “Merkmale der Führungsorganisation Amerikanischer Unternehmen,” Zeitschrift für Führung und Organisation, vol. 41, No. 3, 1972. pp. 3-8, 85-89, 145-148.

- A. Heigl, “Controlling - Interne Revision,” The University of Texas at Brownsville, Brownsville, 1989.

- B. Huch, “Informationssysteme im Operativen Controlling – Rechnungswesen und Berichtswesen,” Kostenrechnungsp Raxis, vol. 28, No. 5, 1984, pp. 103-109.

- S. Neuhäuser-Metternich and F.-J. Witt, “Kommunikation und Berichtswesen,” Beck Juristischer Verlag, München, 2000.

- T. Reichmann, “Controlling mit Kennzahlen und Managementberichten: Grundlagen Einer Systemgestützten Controlling Konzeption,” Vahlen Verlag, Vahlen, 2001.

- Amshoff, “Controlling in Deutschen Unternehmungen: Realtypen, Kontext und Effizienz,” Gabler, Wiesbaden, 1993.

- J. Weber, U. David and C. Prenzler, “Controller Excellence,” Wearable Hemo-Ultrafiltratiin, Otto Beisheim, 2001.

- I. Göpfert, “Berichtswesen,” In: H.-U. Küpper and A. Wagenhofer, Handwörterbuch Unternehmensrechnung und Controlling, 4th Edition, SchäfferPoeschel, 2002, pp. 143-155.

- E. Scheffler, “Das Konzerninterne Berichtswesen als Grundlage für ein Effizientes Konzern-Controlling,” In: K. Küting and C.-P. Weber, Konzernmanagement: Rechnung - Swesen und Controlling, SchäfferPoeschel, 1993, pp. 303-317.

- M. Haberstroh and W. Papperitz, “Berichtswesen: Schnelligkeit als Wesentliche Anforderung des Controlling,” Controlling, vol. 4, 1992, pp. 12-19.

- G. Steinbichler, “Das Berichtswesen im Internationalen Unternehmen: Gestaltungsmöglichkeiten für das Controlling,” Controlling, vol. 2, No. 2, 1990, pp. 144-147.

- H.-U. Küpper and J. Weber, “Taschenlexikon Controlling,” SchäfferPoeschel, Stuttgart, 2001.

- R. Koch, “Betriebliches Berichtswesen als Informationsund Steuerungsinstrument,” Peter Lang, Wolfert, 1994.

- S. M. Stadler and B. E. Weißenberger, “Benchmarking des Berichtswesens,” Controlling, vol. 11, No. 4, 1999, pp. 5-11.

- J. Berthel, “Informationsbedarf,” In: E. Frese, Handwörterbuch der Organisation, SchäfferPoeschel, 1992, pp. 872-886.

- F. Wall, “Planungs-und Kontrollsysteme,” Gabler, Wiesbaden, 1999.

- T. Keller, “Enwicklung eines Anreizsystems zur Steigerung der Aufgabenbereitschaft von Informationen im Informationssystem der Unternehmung,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Hamburg University, Hamburg, 1994.

- G. A. Miller, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information,” Psychological Review, vol. 63, No. 2, March 1956, pp. 81-97.

- J. Weber, B. Hirsch, S. Linder and E. Zayer, “Verhaltensorientiertes Controlling,” Der Mensch im Mittelpunkt, WHU, 2003.

- H.-U. Küpper, “Controlling: Konzeption, Aufgaben und Instrumente,” SchäfferPoeschel, 2003.

- C. Homburg, J. Weber, J. T. Karlshaus and R. Aust, “Interne Kundenorientierung der Kostenrechnung,” Wearable Hemo-Ultrafiltratiin, 1998.

- C. Homburg, J. Weber, J. T. Karlshaus and R. Aust, “Interne Kundenorientierung der Kostenrechnung?” Die Betriebswirtschaft, vol. 60, No. 2, pp. 241-256.

- J. Weber, “Einführung in das Controlling,” SchäfferPoeschel, Stuttgart, 2004.

- A. Kieser and P. Walgenbach, “Organisation,” SchäfferPoeschel, Stuttgart, 2003.

- R. S. Kaplan and D. Norton, “Translating Strategy into Action: The Balanced Scorecard,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1996.

- E. R. Babbie, “The Practice of Social Research,” Wadsworth, Ohio, 2004.

- C. Homburg and H. Werner, “Kundenorientierung mit System – Mit Customer Orientation Management zu profitablem Wachstum,” Frankfurt am Main et al., 1998.