Health

Vol.5 No.5(2013), Article ID:31914,9 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.55109

An exploration of violence, mental health and substance abuse in post-conflict Guatemala

![]()

1Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA; *Corresponding Author: cbranas@upenn.edu

2Department of Internal Medicine & Global Health Equities, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

3School of Medicine, Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, Guatemala City, Guatemala

4Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, USA

5Hospitalito Atitlan, Santiago Atitlan, Guatemala

6Center for Public Health Initiatives, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

7Section of General Internal Medicine, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, USA

8Division of General Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, USA

9Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA

10Department of Family Medicine & Community Health, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA

Copyright © 2013 Charles C. Branas et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 11 March 2013; revised 12 April 2013; accepted 10 May 2013

Keywords: Violence; Trauma; Civil Conflict; Latin America

ABSTRACT

Guatemala’s 36-year civil war officially ended in December 1996 after some 200,000 deaths and one million refugees. Despite the ceasefire, Guatemala continues to be a violent country with one of the highest homicide rates in the world. We investigated potential associations between violence, mental health, and substance abuse in post-conflict Guatemala using a communitybased survey of 86 respondents living in urban and rural Guatemala. Overall, 17.4% of our respondents had at least one, direct violent experience during the civil war. In the post-conflict period, 90.7% of respondents reported being afraid that they might be hurt by violence, 40.7% screened positive for depression, 50.0% screened positive for PTSD, and 23.3% screened positive for alcohol dependence. Potential associations between prior violent experiences during the war and indicators of PTSD and aspects of alcohol dependence were found in regression-adjusted models (p < 0.05). Certain associations between prior civil war experiences, aspects of PTSD and alcohol dependence in this cohort are remarkable, raising concerns for the health and safety of the largely indigenous populations we studied. Higher than expected rates of depression, PTSD, and substance abuse in our cohort may be related to the ongoing violence, injury and fear that have persisted since the end of the civil war. These, in turn, have implications for the growing medical and surgical resources needed to address the continuing traumatic and post-traumatic complications in the post-conflict era. Limitations of the current study are discussed. These findings are useful in beginning to understand the downstream effects of the Guatemalan civil war, although a much larger, randomly sampled survey is now needed.

1. INTRODUCTION

Between 1960 and 1996 Guatemala experienced a violent civil war during which some 200,000 non-combatant civilians were killed, 440 villages were destroyed and over one million Guatemalans were displaced—both internally and into southern Mexico [1,2]. Those killed included indigenous individuals, laborers, academics, religious leaders, and others who were clearly noncombatants [3]. Fourteen years ago, peace accords were signed between a number of rurally based guerrilla forces and Guatemala’s national army.

Despite attempts at peace, post-conflict violence has continued. In the run-up to the 2008 presidential elections, more than 50 candidates, their relatives, and party activists were killed [4] and the 2012 presidential succession was reportedly preceded by some 40 homicides related to the elections [5]. Moreover, day-to-day crime has reportedly increased since the end of the civil war. The daily murder rate rose from 17 in 2008 to 20 in 2009 and the 2006 homicide rate of 108 per 100,000 in the capital Guatemala City was one of the highest in the Americas, significantly higher than the United States’ national rate of 5.6 per 100,000 [6,7] and over twice that of Detroit which was called America’s most murderous city with a homicide rate of 47 per 100,000 that same year [8].

Today the Guatemalan-Honduran-El Salvadoran triangle is referred to as the most violent area of the world outside of active theaters of war [9]. This has been attributed largely to illegal drugs and gangs [10,11]. Given its geographic location in the middle of the Central American isthmus, Guatemala is considered a major drug trafficking corridor with an estimated 200 metric tons of cocaine passing en route to the US each year since the close of the civil war [12]. Other theories as to why violence has worsened include a fatigued law enforcement sector, despair and distrust in the face of past government corruption, family and community fragmentation, a pervasive criminal culture of impunity [10], endemic poverty, economic modernization [11], changes in social participation [13] and gender discrimination [ 14 ]. Less than a decade after the civil war had unofficially concluded, persistent violence in Guatemala is thought to have resulted in the second highest rates of fear from armed crime in the world and the proliferation of more private security personnel than members of the regular army [15].

There is a perception that the current situation in Guatemala is the result of the country’s past, large-scale civil conflict. As one qualitative, post-conflict report on the Guatemalan civil war stated, “entire communities were obliterated… [and] the country was orphaned abruptly by the loss of valuable citizens whose absence is still being felt”. This same high-profile report also maintains that survivors of the conflict are thought to still be experiencing psychosomatic complaints, traumatic memories, nightmares, and alcoholism [16]. However, population-based, epidemiologic analyses to determine the details of the relationships between past and present violence, and the downstream effects of this violence on mental health and substance abuse in Guatemala, are lacking. The objective of this study was to examine the extent, nature, and impact of past and present-day violence in a community-based, in-country sample of Guatemalans in order to determine if any associations exist between this violence and downstream sequelae related to mental health and substance abuse.

2. METHODS

We fielded a community-based survey of respondents selected from both urban and rural areas of Guatemala to quantify the experience of violence, mental health and substance abuse in post-conflict era, after 1996. This survey was of a nonrandom, convenience sample of 86 Guatemalans administered from April 2009 to August 2010 in Guatemala City and the Sololá Department in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Our survey ascertained respondent demographics, trauma history, mental health, substance use history, exposure to weapons and crime, and experience with the prior Guatemalan civil war.

Paper-based survey instruments were administered on foot by a team of 8 interviewers from Guatemala and the United States. These team members conducted their interviews in pairs to enhance rapport and connection with respondents (one Guatemalan with knowledge of the local area was part of each pairing) as well as interviewer safety. Residents confirmed to be over the age of 18 years were approached in public places perceived as safe—parks, municipal buildings, hospital waiting areas, churchyards, markets, and cafes—and surveyed by interviewers in secluded, one-on-one interactions that were out-of-earshot from others. All interviews were completed while sitting alongside the respondent in order to respectfully administer and explain questions and respond to any concerns the respondents might have over the course of the interview. The average time required to complete a survey was 35.2 ± 15.2 minutes.

Consent to conduct the survey was obtained beforehand from each respondent. Potential respondents that refused to be interviewed were not asked further questions. All respondents, including and especially those that could not read or write, were explained the risks and benefits of participation. When a respondent’s primary language was a Mayan dialect, a local Guatemalan trained interpreter was present to translate from Spanish into the appropriate Mayan language. Respondents were paid 20 - 40 quetzales (Q), approximately US $2.50 - US $5.00, for completing the survey. The administration of the surveys and the conduct of the study was fully approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Complete trauma histories documented the dates of each respondent’s first, most significant and most recent experiences with violence. For each reported event, respondents were asked if a government or other political organization was involved. When respondents were unable to give an exact number of times they experienced a given violent event, they were asked to give an estimated minimum. Therefore, if someone said they experienced, for instance, at least fifteen violent events of a certain type, the number fifteen was used.

Trauma histories were primarily documented using the Spanish language version of the Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ, Cuestionaiaro de Historial de Trauma) [17] supplemented with questions written by our study team. Survey items from other instruments were also used, and in some cases modified for use (mostly for purposes of understanding and cultural sensitivity), in documenting trauma histories. These other instruments were the Trauma Events Questionnaire (TEQ) [18], the Stressful Life Events Screening Questionairre [19], and the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) Exposure to Violence Survey [20].

A positive screen for PTSD was defined by three of four affirmative answers to the Primary Care PTSD (PC-PTSD) screen [21]. A positive screen for depression was defined by affirmative answers to both of the Patient Health Questionairre-2 (PHQ-2) questions [22]. An alcohol screen was considered positive for dependence if two or more affirmative answers were given to the CAGE questionnaire [ 23,24 ]. Heavy drinking was defined as drinking five or more drinks in a day for men, four or more for women [25]. A substance abuse screen was considered positive if the respondent answered in the affirmative that their use of alcohol or drugs caused major problems at home, school or work.

Follow-up questions to the trauma, post-traumatic stress, depression, and substance abuse items allowed our interviewers to also document the timing of each respondent’s experiences. We thus questioned our respondents about the frequency and year(s) when their experiences of trauma, mental health, and substance abuse occurred allowing us to place these experiences relative to the official end of the Guatemalan civil war in 1996. We then defined outcome variables that were restricted to the post-war period (e.g., depression that was reported as beginning after the civil war concluded) and independent variables that were restricted to the period of the civil war (i.e. seeing serious injury or death during the war).

We began our analyses by calculating percentages and exploring univariable distributions of our outcome variables, focal independent variables, and numerous sociodemographic factors. Numerous cross-tabulated percentages were also calculated. The distributions of sociodemographic variables for our cohort were also compared to data available for the Guatemalan general population from official sources. Unadjusted, bivariable analyses were then completed between all focal independent variables and outcome variables. Because all outcome variables were prepared as 0 - 1 indicator variables, logistic regression was used throughout permitting the estimation of odds ratios. Each of these independentoutcome comparisons were inspected for statistical significance by calculating p-values and 95% confidence intervals. Finally, logistic regression-adjusted, multivariable analysis were completed for all the same focal independent and outcome variable comparisons. These regression models accounted for the confounding effects of age, gender, unemployment, education, urbanrural home, and marital status. None of these independent variables were excessively collinear, as evidenced by variance inflation factors of less than 4. P-values of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance throughout.

3. RESULTS

The 86 study participants were a median age of 34.5 years and a mean age of 37.4 ± 13.3 years; 45.4% were male and 54.7% were female. A total of 60.5% of respondents spoke at least some Spanish, 30.2% reporting Spanish as their main language, while 39.5% spoke only an indigenous language (Tz’utujil, K’iche’, Kaqchikel, or Q’eqchi’). When asked about ethnicity, 75.6% of our respondents considered themselves indigenous, 20.9% ladino, and 3.5% declined to report their ethnicity. With respect to literacy, 58.2% reported being able to read or write. In addition, 60.5% reported being employed with a mean monthly income of 1337 Quetzales (about US $170). A total of 23.3% of respondents lived in urban areas.

Comparing these demographics to what is reported nationally for Guatemala in 2011 showed similarities and differences among comparable factors—the country’s median age is 20 years, 48.8% male and 51.2% female, 60% of the population speak Spanish, 40% speak other Amerindian languages, 40.5% are indigenous, 45.9% are ladino, 69.1% can read and write, 3.2% are unemployed, 45% are in poverty, active workers have an average monthly wage of 2779 Quetzales (about US $350), and 49% of the population is urban [26,27]. Although many factors were similar in our respondent population and the Guatemalan general population, our respondent population appeared to be older, more indigenous, more unemployed, and more rural than the general population.

The 86 people surveyed experienced 1107 total violent events in their lifetimes (12.9 lifetime violent events per person), of which 1056 (95.4%) were man-made acts of violence such as weapons assaults (12.3 lifetime violent events per person) and 51 (4.6%) were natural acts of violence such as earthquakes and mudslides. A total of 10.5% of respondents reported “more than 30” lifetime experiences with violence, 5.8% reported lifetime experiences with violence that likely exceeded 100 events, and 12.8% reported experiencing no violent events.

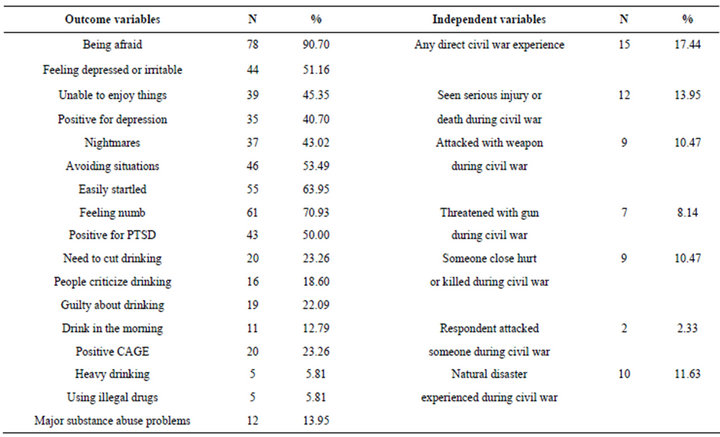

The vast majority of respondents (90.7%) reported being afraid that they might be hurt by violence in the post-conflict period. A gender comparison showed 87.2% of males and 93.6% of females reporting being afraid. A total of 40.7% of our respondents screened positive for depression in the post-conflict period. A gender comparison showed that 30.8% of males and 48.9% of females reported being depressed in the post-conflict period. Exactly half of our respondents (50.0%) screened positive for PTSD, with the most common contributor being respondents who reported feeling numb or detached from others, activities, or their surroundings. A gender comparison demonstrated that 61.5% of males and 40.4% of females screened positive for PTSD (Table 1).

With respect to substance abuse, 23.3% of respondents screened positive for alcohol dependence using the CAGE, with the most common contributor being respondents who reported feeling the need to cut down on their drinking. Although only 5.8% of respondents reported using illegal drugs, 13.9% reported that their use of alcohol or drugs caused them major problems at home, school, or work (Table 1).

When considered together, 37.2% of respondents screened positive for depression and reported being afraid that they might be hurt by violence in the postconflict period. Similarly, 46.5% of respondents were both positive for PTSD and reported being afraid that they might be hurt by violence in the post-conflict period and 22.1% of respondents were both positive for alcohol dependence using the CAGE and reported being afraid that they might be hurt by violence in the post-conflict period. In addition, 22.1% of respondents screened positive for both PTSD and depression in the postconflict period and 15.1% of respondents were positive for both PTSD and alcohol dependence using the CAGE. Only 11.6% of respondents screened positive for both depression and alcohol dependence in the post-conflict period.

A total of 17.4% of our respondents had at least one direct violent experience that occurred during the Guatemalan civil war. Some of these were the experiences of actual combatants and others of unaffiliated, noncombatants (Table 1). When considering unadjusted odds ratios, several outcomes appeared to be significantly associated with reporting at least one direct experience with the civil war. These significant outcomes associated with at least one direct war experience include the reporting of nightmares related to trauma, screening positive for alcohol dependence fusing the CAGE, and heavy drinking (although small numbers made the confidence intervals very large for the association with heavy drinking). Specific experiences with the civil war also showed statistically significant associations with many of the same mental health and substance abuse outcomes, for instance, being threatened with a gun during the war and having someone close hurt or killed during the war (Table 2).

Table 1. Numbers and percentages of mental health and substance abuse outcomes and respondent experiences during the civil war.

Table 2. Unadjusted odds ratio associations between respondent experiences during the civil war and mental health and substance abuse outcomes.

Most of these significant associations did not persist in regression models adjusted for the confounding influences of age, gender, unemployment, education, urbanrural home, and marital status. Respondents who reported at least one direct experience with the civil war were 11.4 times more likely to also report being annoyed by people criticizing their drinking, a statistically significant association (p < 0.05). Respondents who reported having someone close to them hurt or killed during the civil war were 10.2 times more likely to also report having nightmares related to trauma, another statistically significant association (p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3. Regression-adjusted odds ratios between respondent experiences during the civil war and mental health and substance abuse outcomes.

4. DISCUSSION

Ethnographic and cross-national studies have documented the negative mental health and substance abuse effects civil wars have after war-related violence has ended [28]. Few population surveys exist however, documenting these effects in detail for single countries, especially Guatemala. Although it represents early findings, our current survey analysis of violent events, mental health, and substance abuse in Guatemala contains some novel and useful findings. A few significant relationships remained after statistical adjustment. These statistically significant relationships—between prior civil war experiences and indicators of PTSD (having nightmares or unwanted thoughts) and one aspect of alcohol dependence (being annoyed when criticized for drinking) —are of sufficient magnitude that they raise concerns about mental health and warrant further investigation.

Over a decade after the official end of the Guatemalan civil war, over 90% of the respondents we surveyed reported being afraid that they might be hurt by violence and 50% still had probable PTSD. Although these percentages may be influenced by selection effects from our nonrandom sample of Guatemalans, they are excessively large and again warrant concern and a call for further investigation. In Cambodia, a lower rate of 11.2% of probable PTSD was reported 25 years after the Khmer Rouge genocide [ 29 ]. In another study of postconflict Algeria, Cambodia, Ethiopia and Gaza, rates of PTSD were reported to be 37.4%, 28.4%, 15.8% and 17.8% respectively [30], again lower than the rates we found in Guatemala.

According to the World Health Organization, depression affects about 121 million people worldwide (almost 2% of the world’s population) [31] and the age-standardized prevalence of PTSD around the world in 2000 was 208/100,000 among males and 559/100,000 among females [32]. A year 2000 survey of 170 Guatemalan refugees who fled the civil war and were living across the border in Chiapas, Mexico showed a mean of 8.3 violent events per individual with 38.8% having symptoms of depression and 11.8% having PTSD symptoms [33]. A 2001 survey of 179 Guatemalan refugees that had returned to their country showed a mean of 5.5 traumatic events per individual with 47.8% showing depression and 8.9% demonstrating PTSD [34]. The World Health Organization also reports that alcohol use disorders affected about 3% of the world’s population in 2004 [35] and 3.8% of males and 0.7% of females in Guatemala [35].

By comparison, the respondents in our survey experienced 12.3 violent events per individual with 40.7% screening positive for depression, 50.0% screening positive for PTSD, and 22.1% positive for both depression and PTSD. Depending on the metric used, between 5.8% and 23.3% of our respondents also reported some level of substance abuse. These numbers may be higher than some previous reports possibly because of the nonrandom nature of our survey but also because of the very high rate of fear of violence reported by our cohort and the high volume of traumatic events that have continued to occur since the peace accords, as reported by our respondents and corroborated by other sources [9]. Our numbers may also be higher given that our respondents were heavily indigenous and largely came from Guatemala City, one of the most violent cities in the world, as well as the Western Highlands region of Guatemala, which had been a hub of violence during and in the immediate years after the civil war [ 11,13 ].

Our survey data and its analysis have several limitations. Although many factors were similar in our respondent population and the Guatemalan general population, our respondent population also differed from the Guatemalan general population in several indicators. Our study is therefore mostly a hypothesis generating exercise and an exploration of relationships that will require further investigation through larger, populationbased epidemiologic surveys of violence, mental health and substance abuse in post-conflict Guatemala. Although prior surveys of Guatemalan populations investigating these topics were not remarkably larger than the size of the cohort of respondents we analyzed, they did incorporate random sampling unlike the nonrandom survey sample of convenience that was implemented here. Selection biases that accompany convenience samples may erode the generalizability of our findings. In addition, recall biases, telescoping (reporting that a landmark event happened earlier or later than it actually did) [36], and other issues related to the cross-sectional nature of our survey also limit the interpretation of our findings. Finally, multiple testing problems related to our relatively small sample size may not be favorable for the numerous analyses that we have reported here; preferential consideration of results with p-values less than 0.01 can help to address this. Despite these limitations, the high rates of reported violence, fear and associated mental health and substance abuse problems that we found are of sufficient magnitude to, at a minimum, prompt further study.

High levels of reported violence, fear, depression, post-traumatic stress, and substance abuse were evident in the post-conflict Guatemalan cohort we sampled. Certain associations between prior civil war experiences, aspects of PTSD and alcohol dependence in this cohort are remarkable, raising concerns for the health and safety of the largely indigenous populations we studied and warranting further investigation. Higher than expected rates of depression, PTSD, and substance abuse in our cohort may be related to the ongoing violence, injury and fear that have persisted since the end of the civil war. These, in turn, have implications for the growing medical and surgical resources needed to address the continuing traumatic and post-traumatic complications in the post-conflict era. The current study is useful in beginning to understand the downstream effects of the Guatemalan civil war, although a randomly sampled survey of violence, mental health and substance abuse, larger than what has been previously undertaken, is now needed in post-conflict Guatemala.

REFERENCES

- Jonas, S. (2000) Of centaurs and doves: Guatemala’s peace process. Westview Press, Boulder.

- Anonymous (2011) Guatemala’s presidential election— The return of the iron fist. The Economist, 41-42.

- Weisel, T. and Corillon, C. (2003) Guatemala: Human rights and the Myrna mack case. National Academies Press, Washington DC.

- Rosenberg, M. (2007) Violence haunts guatemala’s election. TIME.

- Procurador de los Derechos Humanos (2011) Panorama electoral. 9.

- Overseas Security Advisory Council (2013) Guatemala 2013 crime and safety report. https://www.osac.gov/Pages/ContentReportDetails.aspx?cid=13878

- Rogriguez, A.M. and Santiago, I.G. (2007) Informe estadistico de la violencia en Guatemala. United Nations Development Programme. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/na-tional_activities/informe_estadistico_violencia_guatemala.pdf.%20Accessed%2025%20Feb%202010

- US Department of Justice FBoI, Criminal Justice Information Services Division (2006) Table 6, Crime in the US by metropolitan statistical area. http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2011/crime-in-the-u.s.-2011/tables/table-6%20Services%20Division

- Anonymous (2011) Justice in central America—Parachuting in the prosecutors. The Economist, 45-46.

- Garcia, M. (2004) Lynchings in Guatemala: Legacy of war and impunity. Harvard University Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Cambridge. http://programs.wcfia.harvard.edu/files/fellows/files/fernandez.pdf

- Alvarado, S.E. and Massey, D.S. (2010) In search of peace: Structural adjustment, violence, and international migration. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630, 137-161. doi:10.1177/0002716210368107

- Replogle, J. (2008) Mexico exports drug war to guatemala. TIME.

- Flores, W., Ruano, A.L. and Funchal, D.P. (2009) Social participation within a context of political violence: Implications for the promotion and exercise of the right to health in Guatemala. Health & Human Rights, 11, 37-48. doi:10.2307/40285216

- Carey Jr., D. and Torres, M.G. (2010) Precursors to femicide: Guatemalan women in a vortex of violence. Latin American Research Review, 45, 142-164.

- Hillier, D. and Wood, B. (2003) Shattered lives: The case for tough international arms control. Oxfam International.

- Anonymous (1999) Guatemala, never again! Recovery of historical memory project. Maryknoll, Archdiocese of Guatemala, New York.

- Green, B. (1996) Trauma history questionnaire. Sidran Press, Lutherville.

- Vrana, S. and Lauterbach, D. (1994) Prevalence of traumatic events and post-traumatic psychological symptoms in a nonclinical sample of college students. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7, 289-302. doi:10.1002/jts.2490070209

- Goodman, L.A., Corcoran, C., Turner, K., Yuan, N. and Green, B.L. (1998) Assessing traumatic event exposure: general issues and preliminary findings for the stressful life events screening questionnaire. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 521-542. doi:10.1023/A:1024456713321

- Sampson, R.J., Raudenbush, S.W. and Earls, F. (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918-924. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.918

- Prins, A., Ouimette, P., Kimerling, R., et al. (2004) The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry, 9, 9- 14. doi:10.1185/135525703125002360

- Whooley, M.A., Avins, A.L., Miranda, J. and Browner, W.S. (1997) Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 12, 439-445. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x

- Ewing, J.A. (1984) Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA, 252, 1905-1907. doi:10.1001/jama.1984.03350140051025

- Cremonte, M. and Cherpitel, C.J. (2008) Performance of screening instruments for alcohol use disorders in emergency department patients in Argentina. Substance Use & Misuse, 43, 125-138. doi:10.1080/10826080701212337

- Midanik, L.T. (1994) Comparing usual quantity/frequency and graduated frequency scales to assess yearly alcohol consumption: Results from the 1990 US National Alcohol Survey. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 89, 407- 412. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00914.x

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística Guatemala, Guatemala City. http://www.ine.gob.gt

- CIA (2011) The world factbook. Guatemala. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gt.htm

- Ghobarah, H., Huth, P. and Russett, B. (2003) Civil wars kill and maim people—Long after the shooting stops. American Political Science Review, 97, 189-202. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000613

- Sonis, J., Gibson, J.L., de Jong, J.T., Field, N.P., Hean, S. and Komproe, I. (2009) Probable posttraumatic stress disorder and disability in Cambodia: Associations with perceived justice, desire for revenge, and attitudes toward the Khmer rouge trials. JAMA, 302, 527-536. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1085

- De Jong, J.T., Komproe, I.H., Van Ommeren, M., et al. (2001) Lifetime events and posttraumatic stress disorder in 4 postconflict settings. JAMA, 286, 555-562. doi:10.1001/jama.286.5.555

- Marcus, M., Yasamy, M.T., Van Ommeren, M., Chisholm, D., Saxena, S. A global public health concern. WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, 1-4. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/depression/who_paper_depression_wfmh_2012.pdf

- Ayuso-Mateos, J.L. (2006) Global burden of post-traumatic stress disorder in the year 2000. Global Burden of Disease, World Health Organization Global Program on Evidence for Health Policy.

- Sabin, M, Cardozo, B.L., Nackerud, L., Kaiser, R. and Varese, L. (2003) Factors associated with poor mental health among Guatemalan refugees living in Mexico 20 years after civil conflict. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290, 635-642. doi:10.1001/jama.290.5.635

- Sabin, M., Sabin, K., Kim, H.Y., Vergara, M. and Varese, L. (2006) The mental health status of Mayan refugees after repatriation to Guatemala. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica—Pan American Journal of Public Health, 19, 163-171.

- World Health Organization (2011) Global status report on alcohol and health. Chapter: Guatemala. Socioeconomic Context. WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication, Geneva.

- Gaskell, G., Wright, D. and O’Muircheartaigh. (2000) Telescoping of landmark events—Implications for survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 77-89. doi:10.1086/316761