Open Journal of Leadership

Vol.03 No.04(2014), Article ID:52332,9 pages

10.4236/ojl.2014.34009

Leadership, Social Identity and the Politics of Underdevelopment in Africa

Godwyns Ade’ Agbude1, Nchekwube Excellence-Oluye1, Joy Godwyns-Agbude2

1Department of Political Science and International Relations, College of Leadership Development Studies, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria

2Charis Center of Leadership Development, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Email: agodwins1@yahoo.com, chekwubeugbede@gmail.com, joygodwyns@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 September 2014; revised 19 October 2014; accepted 5 November 2014

ABSTRACT

Several researches have been conducted on the nature, character and causes of underdevelop- ment in Africa. Some scholars have alluded to the imperativeness of leadership in fostering development in Africa while some pointed a robust accusing finger to the structures of the international political system. While this paper does not join issues with these scholars, it however focuses on locating the dilemma of social identity as the missing factor in all inter personal relationships in Africa with special bias for the relationship between the led and the leaders. This paper briefly engages the arguments and counterarguments of the paradox of development in Africa and then goes on to show how the absence of social identity or group identity has been the bane of development in Africa. While dwelling on available secondary data, this paper theorizes the interplay among politics of underdevelopment, leadership and social identity in Africa. It concludes by arguing for the necessity of class suicide of the political class and also cognitive re-orientation of the led through education.

Keywords:

Leadership, Politics, Social Identity, Development, African States

1. Introduction

There is an interconnection among development or underdevelopment, social identity and leadership. It is this interconnectivity that this paper intends to investigate. The problem this paper basically addresses entails the consistent argument for the cause of underdevelopment in Africa. It visits this argument with the intention of showing the possibility of a perennial crisis of development in Africa if we do not grab the “bull by the horns” by radically pursuing social identity in Africa in order to encourage humane interpersonal relationship between the leaders and the led. What follows is a critical discussion of the several variables in this topic in order to further achieve the objective of this paper which aimed at re-directing the argument against Western political hegemony as the bane of development in Africa; and re-focusing on the loss of social identity as the cause of misbehaviours of the leaders and the led in Africa.

Claude Ake (1995, 1996) ; Samir Amin (1976, 1978); Arturo Escobar (1988, 2012) consistently argued that the Western political powers set the stage for the underdevelopment of African countries. For Samir Amin, underdevelopment, put in its historical perspective, is the cumulative result of unequal exchange, unequal development and imperialism (Amin, 1973, 1976, 1977). Therefore, Amin proposed “delinking” which he construed as the subordination of external relations to internal demands for popular transformation and development as against the bourgeois strategy of adjusting the internal growth of their countries to the demand of the worldwide expansion of capitalism (Amin, 1987).

2. Methodology

This paper employs the discursive analysis as a methodology of interrogating the concepts involved in this research. It dwells primarily on secondary data as the informative ground for projecting an ideal society in Africa.

3. Leadership

There is multiplicity in the definition of leadership, in the sense that various scholars and writers have seen and reviewed this concept from different views.

Newstrom and Bittel (2002) see leadership as the process of influencing and supporting others to follow you and to do willingly the things that need to be done. So leadership basically has to do with influence according to this definition, and this influence automatically generates support, and eventually “HE” who influences and “THEY” who support work cordially to generate desired results.

Boone and Kurtz (1984) give a similar definition. They posit that it is the function by which a manager or leader unleashes the available resources in order to get the organization to carry out plans to accomplish objec- tives, or the act of motivating or causing people to perform certain tasks intended to achieve specified objectives. They further note that leadership is “the act of making things happen”. Therefore, leadership is impossible without a guiding vision and purpose that generates passion for accomplishment. Leadership derives its power from values, deep convictions and correct principles.

According to Munroe (1984) , “leadership is like beauty, it’s hard to define but you know it when you see it”. More, leaders he argues are “ordinary people who accept or are placed under extra ordinary circumstances that bring forth their latent potential, producing a character that inspires the confidence and trust of others”. Munroe here posits that a leader or leaders must be people who inspire, and win the trust of people.

In summary of these definitions however, it is pertinent to note that from the foregoing definitions of leadership, a common trend to be seen among the various interpretations of leadership is that it relates to exerting influence over a group of people so that the collective purposes of that group will be achieved optimally. Leadership entails the ability to inspire other people to work towards the attainment of a common goal. Leadership is therefore vital in any organization or community because a manager must use it to secure the co-operation of his subordinates.

Leadership is a complex phenomenon involving the leader, the follower and the situation. Some leadership researchers have focused on the personality, physical traits, or behaviours of the leader, others have studied the relationship between the leaders and the followers; still others have studied how aspects of the situation affect the way leaders act. Some have extended the latter viewpoint so far as to suggest that there is no such thing as leadership; they argue that organisational successes and failures often get falsely attributed to the leader, but the situation may have much greater impact on how the organisation functions than does any individual, including the leader.

4. Social Identity

The Social Identity theory is a theory of group process and intergroup relations-that is, how we relate to others. This theory has been elaborated and occasionally misinterpreted by some scholars but its usage in this paper is to re-visit the politics of underdevelopment in Africa.

According to Chambliss and Schutt (2010: p. 23) , “a theory is a logically interrelated set of propositions about empirical reality”. A theory helps us clarify, understand, predict things, guides a research and serves as a basis for action. Identity is a term that means different things to different people. An identity comes from categorization with whatever standard; be it, ethnic, personal, social, gender etc. Hogg and Abrams (1998) define identity as “people’s concepts of who they are, of what sort of people they are, and how they relate to others” (cited in Fearon, 1999: p. 6 ). Therefore, identity is used in two forms from the above definitions-personal and social terms.

The Origin of the Theory

The post World War 11 led to the desire of many social psychologists to understand the psychology of intergroup relations. Early attempts to explain this relied heavily on the notion that prejudice was the irrational manifestation of some force that resided in the individual (Hornsey, 2008) . This revealed a broader predisposition within social psychology to view intergroup relations as interpersonal processes.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, there were robust debates about what impact social psychological theory has made. Many scholars have criticized the field for its tendency to overlook “big picture” constructs such as language, history, and culture in favour of interpersonal processes (Hornsey, 2008) .

The theory began to attract broader international attention in the 1980s and 1990s. The social identity approach is now one of the most influential theories of group processes and intergroup relations worldwide, having redefined how we think about numerous group-mediated phenomena and having extended its reach well outside the confines of social psychology (Hornsey, 2008: p. 2) .

The social identity approach in social psychology was initiated in the early 1970s by the work of Henri Tajfel and his colleagues on intergroup processes. One of the cornerstones to this approach is an insistence that the way in which psychological processes play out is dependent upon social context (Reicher, Spears, & Haslam, 2010: p. 4) . The theory was originally developed to understand the psychological basis of intergroup discrimination. Social identity theory introduced the concept of social identity as a way to explain intergroup behaviour.

Social Identity helps to define who we are and how we relate to others. It includes our self concept as well as the various groups of people with whom we identify (Brewer, 2001: p. 56) .

Social identity theory states that social behaviour will vary along a scale between interpersonal behaviour and intergroup behaviour. Interpersonal behaviour would be behaviour determined solely by the individual character- ristics and interpersonal relationships that exists between two or more people. While, intergroup behaviour would be behaviour determined solely by the social category memberships that apply to two or more people (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) .

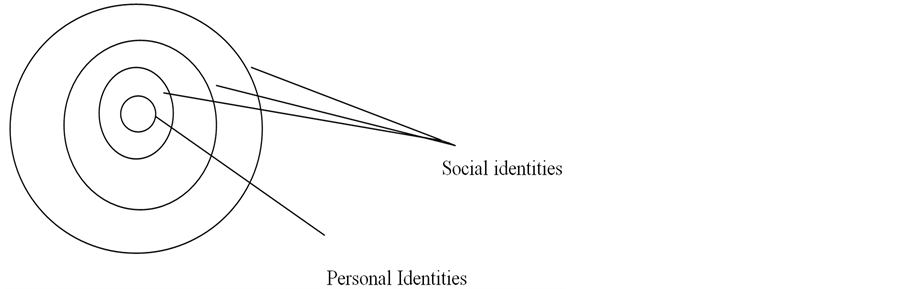

Source: (Brewer, 2001: p. 56)

In the Social Identity Theory, a person has not one “personal self” but rather, “several selves” that correspond to widening circles of group membership. Different social contexts may trigger an individual to think, feel and act on the basis of his personal, family or national “level of self” (Turner et al., 1987) . Also at the “level of self”, an individual has multiplied “social identities”. Social identity is the individual’s self-concept derived from perceived membership of social groups (Hogg and Vaughan, 2002). In other words, it is an individual-based perception of what defines the “us” associated with any internalized group membership. This can be distinguished from the notion of personal identity which refers to self-knowledge that derives from the individual’s unique attributes. There is a prevalence of “We” as opposed to “I”.

Tajfel and Turner (1979) identify three variables whose contribution to the emergence of in-group favoritism is particularly important. 1) The extent to which individuals identify with an in-group to internalize that group membership as an aspect of their self-concept; 2) The extent to which the prevailing context provides ground for comparison between groups; 3) The perceived relevance of the comparison group, which itself will be shaped by the relative and absolute status of the in-group.

Tajfel and Turner (1979) proposed that the groups which people belonged to were an important source of pride and self-esteem. Groups give us a sense of social identity: A sense of belonging to the social world (Mcleod, 2008) . Put differently, human beings have an indispensable need for positive self-esteem and they are manifested in both; personal identity and social identity.

It should be clear that social identities are much more than self-perceptions-they also have value and emotional significance. To the extent that we define ourselves in terms of a group membership, our sense of esteem attaches to the fate of the group (and hence the fate of fellow group members is pertinent to our own).

The concept of social identity bridges the gap between the individual and the societal and allows one to explain how socio-cultural realities can regulate the behaviours of individuals. The social nature of the bond is primary rather than secondary. That is, we are bound together through our joint sense of belonging to the same social category. Hence, what we do as group members is not constrained by the stance of a particular individual but by the socio-cultural meanings associated with the relevant social category. Put differently, social identity provides a psychological apparatus that allows humans, uniquely, to be irreducibly cultural beings. In order to understand the full significance of this stance, it is necessary to be aware that social identity not only transforms our understanding of the self-concept, but also of all self-related terms.

Perhaps the most profound implications relate to the notion of “self interest”, which underpins dominant conceptions of rationality. In this, the rational actor is one who effectively maximises the utility that accrues to the individual self, where “utility” is measured by reference to a universal standard such as monetary gain. In such conceptions, the “self” of “self-interest” is presupposed to be the personal self. However, where social identities are salient and constitute the self, a utility to fellow in-group members can constitute a utility to the (collective) self (Reicher, Spears, & Haslam, 2010: p. 14) . Moreover, what constitutes “utility” will vary from group to group―for some religious or ascetic groups more money may even have negative utility (it impedes entry into the kingdom of heaven).

The whole approach rests on the assumption that social change occurs when people act on shared social identity rather than act separately on the basis of their various personal identities.

5. Leadership and the Politics of Underdevelopment: Revisiting the Paradox of Africa’s Crisis

It is not too difficult to understand that from the foregoing above, the failure of the African States is the loss of social identity between the leaders and the led. African States have been thrown into this perennial development crisis because of the inability of the social “selves” to serve as the bond holding the continent, as it were (the individual countries), together. The State power that should have been used to advance the collective well-being of the people has become a tool of personal advancement in the hands of political leaders in Africa. Personality rule has replaced collective governance. This reinforces the importance of John Adams’ claims that what they wanted was “the government of laws and not of men”. Africa has the government of men and not that of laws. The implication of this is that the men can sabotage the process of law even to the extent of violating fundamental human rights.

Mbaku (2004) observes that:

…more than four decades of independence, most African countries are still underdeveloped and the people continue to suffer from poverty and material deprivation. In fact, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Africa, especially sub-Saharan Africa, still remains the poorest part of the world with most citizens unable to meet their daily basic needs. According to the UNDP’s (2003) human development index (HDI), of the thirty-four poorest and least developed countries in the world today, thirty (88 percent) of them can be found in Africa (Mbaku, 2004: p. 388) .

From the above, it is as though underdevelopment, poverty and retrogressive economy have been immortalized in Africa. Despite its variegated resources, Africa still dives deeper into the ocean of underdevelopment. Several development strategies (both exogenous and endogenous) have come and gone, yet there is hardly anything to show for African development. Africa is said to have more poor citizens compared to other continents. Africa is home to the poorest countries in the world, ranking higher than every other continent. The concepts of development strategies and ideologies are pervasive in Africa’s political lexicon with little or no proof to show of development.

Ake (1996) believes that political leaders use the development ideology as a tool to pauperize their people. For Ake, development is yet to commence in Africa given that what is presented by the political leaders and their Western counterparts are nothing short of mere “policy garbage” used to further personal economic benefits of the leaders. For some other scholars, as well as Ake, the problem of post-colonial African States is the existence of the colonial State inherited from their former oppressors (the colonialists).

But for Hammouda (1998: p. 21) , “connected with colonial oppression and domination, classical reason con- tinued to exert its influence over the elites in the colonized countries, resulting into the present crisis of development in Africa. The inheritors of the colonial State were not able to dismantle it in order to build for the progress and happiness of their people”. It is possibly for this reason that King-Akerele (1998: p. 22) argues that “the crisis that we face is not merely an economic one. We have, I believe, a more profound crisis of the mind, of a commitment to our people and their long-term well-being”. That is, the problem with Africa is a “mind- blindness” problem. In other words, Africa may need to go through mental decolonization and mental purification.

Despite its wealth, the deplorable state of the post-colonial African States has been worrisome for intellectuals and sincere policy-makers. The failures of most of the development ideologies have been beyond contemplation.

According to Kiawi and Mfoulou,

Despite its abundant human and natural resources, coupled with good economic performances in the 1960s and 1970s, the continent has at the same time produced despicable forms of poverty. The story from the 80s up to the 90s has even been worse. Theorists have had to redeploy their energies in an attempt to come up with more meaningful theories of development. Institutional establishments and think-tank set-ups such as the Global Coalition for Africa, African Crisis Response Initiative, African institutes across many universities in the world, etc., have made incredible attempts towards understanding the African phenomenon (Kia- wi & Mfoulou, 2002: p. 12) .

Despite its prosperity in terms of human and material resources, the African countries are still victims of poverty and underdevelopment. Several policies and theories of development have failed to engender development in Africa. Instead of developing, the continent has been home to the most underdeveloped, most crisis and conflict-ridden and poverty-ridden countries in the world. Apart from the institutional establishments stated in the above quote, other strategies have been employed namely the Monrovia Declaration of Commitment, the Lagos Plan of Action, the Leadership Forum, Economic Commission for Africa including the African Alternative Frame- work to Structural Adjustment and African Common Position on the African Environment and Development Agenda. Perhaps we could argue that though these strategies have not increased the standard of living of the people, their implementations have assisted and stalled the continent from degenerating into extinction. In other words, maybe the African States would have become defunct if not for these strategies and these institutional establishments. But on the contrary, it has been argued that their impact has not been felt given the absence of tangible improvements in the lives of the people who are the means and the ends of development. For instance, the African Alternative Framework emphasizes the need to restore growth through reducing economic imbalances and massive dependence on external management, governance and market structures. To achieve these aims, the Framework emphasizes domestic resource mobilization, better terms of trade and market access, and debt relief (Ndulu et al., 1998: p. 5) . With the components of the African Alternative Framework, the predicaments (poverty, underdevelopment and conflicts and crises) of the African States are still on the increase. Peradventure, that explains why King-Akerele feels that the present crises in Africa require reflective vision as a pathway out of the doldrums of underdevelopment, poverty and conflicts. For her, “in the present circumstances and against the backdrop of today’s world, a world of Globalization; of interdependence and the implications thereof, Africa and its peoples, its leadership, policy makers and intellectuals need to undertake a serious reflection as to ‘where we are and where, as a people we are going’” King-Akerele (1998: p. 22) . In the light of the African predicaments, Ndulu et al. (1998) argue for the need for development vision or vision for development which they describe as an articulation of the most desirable and realistic condition or situation which a nation would like to attain and the most plausible course of action for its achievement. Vision for development is a conception of ideals, of what ought to be for the best of society or conditions that ought to be created.

Vallianatos (2001) in his article, All the Gods of Africa Are Weeping, captures the African predicaments thus:

With about a third of its population hungry, sub-Saharan Africa is probably the most impoverished region of the world. Poverty, wars, foreign powers’ cold war food politics in the continent, droughts, environmental degradation, rapid population growth, foreign debt and inappropriate industrial development policies are partly responsible for Africa’s massive hunger, but they do not explain it. The roots of African hunger lie deep in the structure of the most persistent of colonial institutions in the continent―the export out of sub-Saharan Africa of plantation agricultural cash crops to the markets of Europe and North America. Long after Europe had abandoned the slave trade, slavery and the colonies themselves, it remained, together with its successor states in North America, determined to maintain hegemony over those former imperial territories, and particularly to retain uninterrupted access to African resources. So it educated Africa to maintain its colonial institutions for achieving “progress” and “development”. This gave birth, among other things, to an entire stream of economic development literature legitimising the perpetuation of colonialism in Africa under the guise of development (Vallianatos, 2001: p. 45) .

While identifying the several symptoms of underdevelopment in Africa, he argued that these only capture the realities in Africa but do not explain them. Poverty, hunger, environmental degradation, given the operations of the imperialist multinational corporations in Africa, population explosion, heavy and depressing foreign debt accompanied with inaccurate development policies imposed on Africa are the realities of this second largest continent in the world with diverse human and material resources. The part of the root of Africa problems is the imperialists’ education of Africans who were later used as tools for perpetrating their colonialist and capitalist tendencies. This, according to Vallianatos, is evident in the several economic development literature eulogizing Western concepts and alien paradigms that serve, primarily, the interests of the imperialist countries of the Western hemisphere. For instance, an African scholar of repute, Mazrui (1994) , surprisingly asked for a benign re-colonization in Africa. In other words, the Western world should re-colonize Africa despite the present quest for proper decolonization in Africa. Archie Mafeje provocatively reacts to Ali Mazrui by arguing that: “Ali Mazrui’s discourse on ‘benign colonization’ is intellectually bankrupt, analytically superficial, sensational, and downright dishonest. The proposition that Africa be re-colonized is not only preposterous but also mischievous in that it is not meant for African consumption. It is again Ali Mazrui playing up to his Western gallery” (Mafeje, 1995: p. 19) . What Africa needs is not benign re-colonization but rather a proper decolonization including mental decolonization.

In the same vein, Clemente Abrokwaa argues that:

The end of colonial rule in Africa, beginning in the 1950s, also brought the newly independent African states into the centre of a Eurocentric ideological struggle involving neocolonial forces in the area of economic development or modernization. Capitalist powers in Europe and the United States were keen to demonstrate that the road to sustained economic growth lay in a replication of the Western historical experience. The inherited chain of economic dependence forged during the colonial era ensured that economic, political, and educational models central to capitalist expansion would continue to play a hegemonic role in determining post-independence African development strategies. As a consequence, since the 1950s, the issue of development has engaged the attention of almost all independent African governments, making Eurocentric development strategies the foundation of policy decisions in post-colonial Africa (Abrokwaa, 1999: p. 646) .

The most pathetic part of the African experience of underdevelopment is that in this 21st century, having seen the danger of fraternizing with Eurocentric and “Americo-centric” development ideologies and paradigms, the African political leaders still consistently subject their growth and development to Western appraisal as though Africa lacks the capacity for self-development. The inherited chain of economic development forged during the colonial era has grown thicker and stronger such that it has pervaded all segments of the African societies. More than 50 years of independence in Africa, yet the story has been that of poverty, hunger, underdevelopment, crises and conflicts resulting into the loss of valuable lives and property. Perhaps, we could subscribe to the idea of the myth of post-colonialism in Africa. Has Africa been totally decolonized? Is independence not merely mental “self-pride”? In other words, the problem was that Africa had (has) no authentic ideology that could be used to further its development, thus consolidating its independence. Therefore, post-colonialism could still be subjected to rigorous interrogation given Africa’s “self-prostitution” with the Western world.

Compared to other developing countries, Africa is fast lagging behind. The most recent available regional comparative data indicates that, in 2000, 45% of the population of sub-Saharan Africa did not have access to safe water compared to 13% in South Asia and 24% in low income countries; for health services, the figure was 48% without access compared to 22% in South Asia and 20% for all developing countries; while for sanitation facilities, the performance was slightly better than average with 45% without access compared to 63% in South Asia and 55% in all low income countries (World Bank, 2002; Hope, 2004: pp. 131-132) .

The failure of development in Africa is evident in that the development paradigms and policies initiated and implemented in Africa have not touched the core areas that are the targets of development. For instance, Christian Lund defines development processes as the reproduction and transformation processes which somehow impinge on inequality, impoverishment and human insecurity (Lund, 2010: p. 20) . Development in Africa has no bearing on inequality, impoverishment and insecurity.

It has also now generally accepted that statism failed to reduce poverty in Africa. In fact, statism, restricted private enterprise and initiative thereby resulting in inefficiency, corruption and sub-optimal output levels (Hope, 1997; 2004: p. 134) . Consequently, the transition process from statism to liberalization has, at least in the short-run, deepened poverty in many of the African countries now considered to be liberalizing economies with negative consequences (Hope, 2004: p. 134) .

Hope continues:

The incidence of poverty has fallen in most regions of the world since 1945. However, in Africa, poverty continues to be a significant and deepening socio-economic problem despite the gains in economic progress and growth in some of those countries since embarking on the process of economic liberalization or structural adjustment (Hope, 2002). African poverty is multifaceted. It is characterized by, among other things, a lack of purchasing power, rural predominance, exposure to environmental risk, insufficient access to social and economic services, and few opportunities for formal sector income generation-the primary source of income earning opportunities (World Bank, 1994). In addition, there are other influential dimensions such as poor health, malnutrition, lack of shelter, lack of political rights and illiteracy (Hope, 2004: p. 127) .

Africa’s underdevelopment is more evident in the poverty level of the citizens as it reflects in the insufficient access to social and economic services, poor health, malnutrition, absence of shelter, inability to meet daily needs, illiteracy, deprivation and lack of income earning opportunities. According to Kempe Ronald Hope, there are three categories of the poor in Africa. The first category is the chronic poor; who are individuals at the mar- gin of society and who constantly suffer from extreme deprivation. The second category is the borderline poor; who are individuals or households who are occasionally poor, such as the seasonally unemployed. The final category is termed the newly poor; who are individuals or households who are the direct victims of the crisis of development policy that has rendered them unemployed. They may include retrenched workers and civil ser- vants (Hope, 2004) .

More so, the failure of foreign aids and development ideologies to generate development in Africa has been traced to corruption. According to Mbaku (2008: p. 427) , in several regions around the world, especially in Africa, corruption remains an important obstacle to political and economic development. Corrupt political leaders, policy-makers and bureaucrats have imposed corruption on the whole society such that corruption has become a culture in most African States.

Development discourse has no relevance until it has succeeded in decreasing this “army of poverty” in Africa. Therefore, we do not intend to “re-problematize” the African problems again but rather to re-visit the strategies that have been suggested for Africa’s development.

For Leonard and Straus (2003) , the paradox of Africa’s development is entrenched in the dynamism of its politics.

According to them:

Sub-Saharan Africa’s development problems are inseparable from its politics. International economic forces well beyond sub-Saharan Africa’s control have hobbled the continent, but some countries have been able to adopt public policies that have improved their development performance. Why have only relatively few countries in Africa succeed in making the changes necessary to improve their economic performance since the 1960s? The short answer is that the dynamics of African politics have worked against policies that would lead to greater development (Leonard & Straus, 2003: p. 1) .

This analysis seems to answer the question of the crisis of underdevelopment in the Sub-Saharan African region. The failure of the other paradigms is traceable to this dynamic character of African politics. While some African States have improved on the structure of the colonial state they inherited by integrating the well-being of their citizens into governance, some African States have totally driven farther away from the aspirations and the needs of the people. For Leonard and Straus (2003) , the failure of the development policies in Africa is not in- herently due to the internal faults of these policies but rather the peculiar nature of African politics which they refer to as “personal rule paradigm”.

Ake (1995) had long ago identified the development crisis in Africa as more of the feature of the internal politics in the African continent. According to him:

We have seen the African crisis broadly as a crisis of development and more specifically as an economic crisis, because of the compelling presence of its economic dimensions: the relentless falls in real incomes, share of world investment and trade, commodity prices and food production; growing malnutrition, decaying cities and collapsing infrastructure. But the crisis is, to my mind, primarily a crisis of politics, from the economic crisis derives (Ake, 1995: p. 72) .

The uniqueness of this argument is that Ake identified, beyond the internal character of African politics as played by the new African leaders, the role of the international community, especially the ex-colonial masters, in furthering their economic interest by manipulating the new inheritors of the colonial State. Leonard and Straus (2003) are of the opinion that there are certain institutions and structures with international dimension that allow “personal rule” to persist in the continent of Africa. The concept of “personal rule” can be broken down into the following terms such as “patrimonialism”, “neopatrimonialism”, “prebendalism” and “sultanism”. The components of these include the following 1) appointment and position generally depend on loyalty to one’s superior and not on adherence to impersonal norms, 2) transactions are personalized and office is treated as a form of personal property and a source of private gain (which Weber called a prebend), and 3) a clear sense of a public interest that transcends private ones does not exist (Leonard & Straus, 2003: p. 2) . These seem to be the characteristics of contemporary politics in Africa. Thus, one could conveniently argue that African leaders’ claim to democratic governance has not outgrown “personal rule paradigm”. All the explanations given above for African political leaders’ failure to develop their continent boil down to the missing link-social identity or group identity.

What has been responsible for the inability of the African States to transcend their states of underdevelopment to development is the absence of a bond among the people, starting with the leaders. According to Thomas et al. (2013) the social identity approach to leadership also focuses on the social cognition of group members, but im- portantly emphasizes the cognitive processes that are primarily associated with psychologically belonging to the group. Group membership provides people with a sense of identity―a social identity―and leaders express, epi- tomize, and shape this group identity.

From this, the African leaders have failed to foster a group identity (a national identity) that should be the ground for collective wellbeing of the society at large. What has replaced social identity (group identity) is now class identity of the political elite.

A basic principle of the social identity theory of leadership is that as group membership becomes more salient, and members identify more strongly with the group, leaders who are more prototypical of the group are deemed to be more effective than those less prototypical of the group (Hogg, 2001, 2005; Thomas et al., 2013) . The effectiveness of a leader in advancing the course of development in his/her region is tied to his/her identification with the group which is the society at large. The failure of leadership in Africa is their inability to identify with their society at large. When group identification or social identification is fallen, the likelihood exists that those who come into position of power will be unable to advance the course of development or wellbeing of the general society. This explains the reasons Africa, over the years, has not been able to produce leaders who identify with the collective existence of their people but rather leaders who pursue ethno-development (development of their ethnic groupings) or personal development (pursuing selfish interests).

Every attempt to trace the crisis of development in Africa to any other source collapses in the face of the failure of social identity or group identity as the underlying bond of collective existence. The simple escape route is to blame the West for the underdevelopment of the continent. But the truth that must be told is that African leaders (with the exception of very few) have failed to forge an identity for their societies. The irony of this is that leadership failure to identify with group or society at large has provoked citizens’ disengagement from group identity to pursue individual or ethno-identity which has become the breeding group of conflicts, corruption and underdevelopment in Africa.

6. Africa: Which Way Forward?

If we must end the trend of underdevelopment in Africa, we must rise to the occasion of fostering common social or group identity for African States. This is not seeking common laws or traditions or values in the continent. It simply implies replacing individual or ethnic identity with social or group identity. In this format, the quest becomes treating the whole country as a group or a social enclave to which everybody belongs, irrespective of the races or ethno-religious outlooks. Personal interests are subsumed under collective interests. Ethnic interests are integrated into one poll of group or social interests. This begins with our leaders committing what Amilcar Cabral called “class suicide” which is a process whereby the national bourgeoisie give up their class interests for the interests of the society at large (Cabral, 1980) . Fostering social or group identity on the basis of collectivity is the most appropriate step to ending this present politics of underdevelopment in Africa. If we fail to foster so- cial identity in our psyche and in our idea of governance in Africa, there will be a consistent recruitment of new leaders who would have drifted far apart from the social and collective well-being of the governed.

Also, at the level of elementary education, social identity should be taught and encouraged in order to enhance the cohesiveness in our social intelligence in Africa. However, this educational re-orientation will be ineffective if the political class fails to show its identification to the masses. Those who grow out of the masses to become leaders would have found social or group disintegration as a normal or ideal way of life in our politics; and then they will participate in and continue the tradition of pursuing personal interests as against social and group interests. Therefore, a lot lies in the hands of the political class and not just on international political system as some scholars want us to believe. And the problem we are confronted with in Africa is that of social or group identity.

References

- Abrokwaa, K. C. (1999). Africa 2000: What Development Strategy? Journal of Black Studies, 29, 646-668. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002193479902900505

- Ake, C. (1995). The Democratisation of Disempowerment. In J. Hippler (Ed.), The Democratisation of Disempowerment: The Problem of Democracy in the Third World (pp. 66-80). London: Pluto.

- Ake, C. (1996). Democracy and Development in Africa. Washington DC: The Brookings Institutions.

- Boone, L. E., & Kurtz, D. L. (1984). Principles of Management (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

- Brewer, M. B. (2001). The Social Self: Difference at the Same Time. In T. F. Pettijohn, (Ed.) Social Psychology (pp. 54-60). Guilford: McGraw Hill Company.

- Cabral, A. (1980). Unity and Struggle. London: Heinemann

- Chambliss, D. F., & Schutt, R. K. (2010). Making Sense of the World: Methods of Investigation. California: SAGE Publica- tion Company.

- Fearon, J. D. (1999). What Is Identity (As We Now Use the Word)? California: Stanford University. http://www.stanford.edu/~jfearon/papers/iden1v2.pdf

- Hammouda, H. B. (1998). The Third World in a Post-Liberal Era. CODESRIA Bulletin, 2, 17-21.

- Hogg, M. A. (2001). A Social Identity Theory of Leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 184-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0503_1

- Hogg, M. A. (2005). Social Identity and Leadership. In D. M. Messick, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), The Psychology of Leadership: New Perspectives and Research (pp. 53-80). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hope, K. R. (1997). African Political Economy: Contemporary Issues in Development. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Hope, K. R. (2004). The Poverty Dilemma in Africa: Toward Policies for Including the Poor. Progress in Development Studies, 4, 127-141.

- Hornsey, M. J. (2008). Social Identity Theory and Self Categorization Theory: A Historical Review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, Blackwell Publishing. http://www.sozialpsychologie.uni-frankfurt.de/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Hornsey-20082.pdf

- Kiawi, E. C., & Mfoulou, J. (2002). Rethinking African Development: Social Science Perspectives. CODESRIA Bulletin, 1-2, 12-17.

- King-Akerele, O. (1998). Positioning Africa in the Global Space: Reflection of an African Woman. CODESRIA Bulletin, 1, 22-23.

- Leonard, D. K., & Straus, S. (2003). Africa’s Stalled Development: International Causes and Cures. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Lund, C. (2010). Approaching Development: An Opionated Review. Progress in Development Studies, 10, 19-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/146499340901000102

- Mafeje, A. (1995). “Benign” Recolonization and Malignant Minds in the Service of Imperialism. CODESRIA Bulletin, 2, 17-20.

- Mazrui, A. A. (1994). Decaying Parts of Africa Need Benign Colonization. International Herald Tribune, Pretoria, 4 August 1994.

- Mbaku, J. M. (2004). NEPAD and Prospects for Development in Africa. International Studies, 41, 387-409. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002088170404100403

- Mbaku, J. M. (2008). Corruption Cleanups in Africa: Lessons from Public Choice Theory. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 43, 427-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0021909608091975

- McLeod, S. (2008). Social Identity Theory. http://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html#sthash.UsNnjwtA.dpbs

- Munroe, M. (1984). Becoming a Leader Every One Can Do It. Lanham, MD: Pneuma Life Publishing.

- Ndulu, B. et al. (1998). Toward Defining a New Vision of Africa for the 21st Century. CODESRIA Bulletin, 1, 4-10.

- Newstrom, J. W., & Bittel, L. R. (2002). Supervision Managing for Results (8th ed.). New York: McGraw Hill.

- Reicher, S. D., Spears, R., & Haslam, A. S. (2010). The Social Identity Approach in Social Psychology. In M. Wetherell, & C. T. Mohanty (Eds.), Sage Identities Handbook (pp. 45-62). London: Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446200889.n4

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33-47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Thomas, G., Martin, R., & Riggio, R. E. (2013). Leading Groups: Leadership as a Group Process. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16, 3-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1368430212462497

- Turner, J. C. et al. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford & New York: Blackwell.

- Vallianatos, E. G. (2001). All of Africa’s Gods Are Weeping. Race & Class, 43, 45-57. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0306396801431003

- World Bank (2002). World Development Indicators 2002. Washington DC: World Bank. http://dx.doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-5088-9