Open Journal of Applied Sciences

Vol. 3 No. 4 (2013) , Article ID: 35000 , 10 pages DOI:10.4236/ojapps.2013.34038

Turning Research into Action: Using Factor Analysis to Enhance Program Evaluation

Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, USA

Email: *ljacobson@kumc.edu

Copyright © 2013 Ruth Wetta et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received February 13, 2013; revised March 13, 2013; accepted March 20, 2013

Keywords: adolescent behavior; adolescent health services; evaluation methodology; evaluation studies; factor analysis; program evaluation; teen sexual health

ABSTRACT

Purpose: Sexual activity among adolescents in the United States remains high. Nearly 46% of students grades 9 - 12 have engaged in sexual intercourse. One of the more recent statistical tools employed in evaluation efforts includes factor analysis. The objective of this study was to investigate the underlying dimensions of a survey instrument that assesses a youth character development program, which focuses on avoiding high-risk behaviors. Method: The 76-item survey instrument was administered to adolescents (age 12 - 18). During the 2009-2010 school year, 652 participants in the intervention group and 1110 participants in the comparison group completed the pre-, post-, and 6-month follow-up survey. Results: Using Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior groupings, 27 survey items were selected. Through iterative principal axis factoring, four factors were extracted and rotated. A visual scree plot was generated to determine the number of acceptable factors. The extracted factors accounted for 52.53% of the total variance. Factors were subjected to Equimax rotation with Kaiser normalization and converged after six iterations. Variables with patterned weights less than 0.44 were excluded. A reliability analysis demonstrated internal consistency. Conclusions: Identified factors included: 1) Teenagers’ attitudes toward sexual health behaviors; 2) Teenagers’ perceptions of the consequences of sexual health behaviors; 3) Parental or guardian expectations; and 4) Teenagers’ relationships with parents or guardians. This study’s results indicated that all factors can be described within Ajzen’s theoretical framework consistent with previous research findings. Results may be used to enhance delivery of the intervention.

1. Introduction

Sexual activity among adolescents in the United States remains high. Nearly 46% of students grades 9 - 12 have engaged in sexual intercourse [1]. Recent estimates reveal that approximately 19 million new cases of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are diagnosed each year, almost half of them are among youth ages 15 to 24 [2]. Specifically, Forhan and colleagues [3] estimate that one in four 14 to 19-year-old has a sexually transmitted disease including chlamydia, herpes, trichomoniasis, or human papilloma virus. Teen STDs including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cost the United States $6.5 billion indicating its huge economic impact on American society [4].

Despite recent declines in the birth rate for US teenagers, teen birth rates continue to bear concern because of the socioeconomic burden of teen pregnancy and childbearing [5]. Teen mothers are less likely to graduate high school and more likely to depend on public assistance [6]. Additionally, children born to out-of-wedlock teenage mothers are more likely to experience poor health, poverty, delinquency, educational failure, and higher dropout rates [7,8].

Overall, the literature reports on a variety of interventions aimed to reduce adolescent risk behaviors [9-12]. In an attempt to reach youth within their social environment, interventions are offered within schools [13], faith-based organizations [14,15], and after-school settings [16]. Each intervention must be rigorously evaluated for its impact through the systematic use of various research methods.

Assessment of adolescent attitudes toward sexual health behaviors forms a critical component in the evaluation efforts of teens’ decision making ability to engage or not engage in sexual activity [17-19]. One of the statistical tools employed in evaluation efforts includes factor analysis. Previous studies have successfully used factor analysis to:

1) Identify the nature of the constructs underlying responses in attitudes towards sexual debut and adolescent decision-making about sexual behavior [20-22], and 2) Produce a more precise instrument [23].

Against this background, the objective of this article is to describe the results of factor analysis of a survey instrument that assesses a youth character development program. This study identifies four dimensions of teens’ attitudes about high-risk sexual health behaviors.

1.1. Program Background

Pure & Simple Health Education, Inc., a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization based in a Midwestern metropolitan area, is a faithand community-based agency that educates communities, parents, and youth on the value of: 1) refraining from sexual activity and other high-risk behaviors including alcohol, tobacco, and/or pornography; and 2) development of self-control for the purpose of developing positive, healthy relationships [15]. The organization regularly provides services to high-risk youth including adolescents from troubled families, unwed mothers, and youth transitioning back into society from detention centers. Active since 1997, professional staff and volunteers have educated the community on topics related to human sexuality serving more than 15,000 youth and adults. The curriculum, Pure & Simple Lifestyle (PSL), is a federally funded program. Since its inception, PSL is assessed by a third-party that uses quantitative and qualitative research methods to evaluate the curriculum’s effectiveness in reaching its goal of promoting self-restraint from high-risk behaviors among youth.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

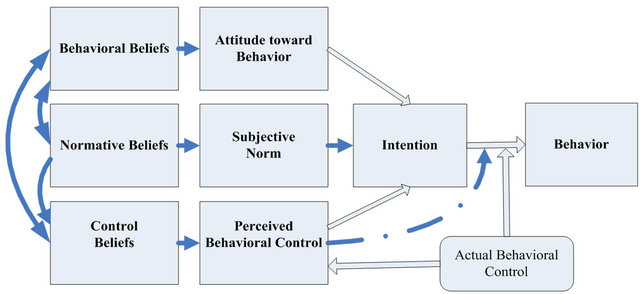

This study’s conceptual framework is guided by Ajzen’s [24,25] Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which is an extension of the Theory of Reasoned Action [26-28] in that TPB includes measures of control belief and perceived behavioral control. Ajzen specifies that behavior depends on a person’s intention and perceived ability. In other words, behavioral intentions can only be expressed in actual behavior if a person voluntarily decides to perform or not perform the behavior. An adolescent’s decision not to engage in sexual activity is a direct function of his/her intention to avoid or resist situations in which sexual activity may occur as long as he/she interprets the behavior as under his/her control. Thus, sexual activity depends to some degree on non-motivational factors (e.g., cooperation, time of day, location, communication, etc.).

Figure 1 describes Ajzen’s theory in more detail. Based on this model, intentions are preceded by: 1) atti-

Figure 1. Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior

tudes resulting from the formation of behavioral beliefs about the outcome of the behavior; 2) subjective norms which refer to the beliefs associated with perceived social pressure; and 3) perceived behavioral control referring to the beliefs about the degree of ease or difficulty of performing the behavior. First, behavioral beliefs connect sexual activity to probable outcomes and represent an adolescent’s judgment that the behavior will produce a given outcome. Accessible beliefs, the relatively small number of readily available beliefs at a given moment, will in combination with the subjective values of the expected outcomes determine the current attitude toward the behavior. Second, normative beliefs represent an adolescent’s perceived expectations regarding behaviors of a reference group (e.g., friends, family, and teachers). These beliefs and the desire to gain approval from the reference group will determine the current subjective norm, which will affect the intention to engage in sexual activity. Third, control beliefs represent an adolescent’s beliefs that he/she has the required skills, resources, and opportunities to engage in sexual activity.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The survey instrument was administered to adolescents (age 12 - 18) within their school setting, community organization, or faith-based organization. During the 2009-2010 academic school year, 652 participants in the intervention group completed the pre-, post-, and 6- month follow-up survey and 1110 participants in the comparison group completed the survey. Sampling methods for program participation and development of the curriculum have been described previously [15]. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita.

2.2. Instrument

The evaluation questionnaire was modeled after the 2004 Ohio Department of Health Abstinence Education Program Survey developed by Robert L. Seufert, Ph.D., at the Applied Research Center of Miami University, Middletown, Ohio [29]. The original Ohio Abstinence Education Program Survey consisted of 98 items designed to collect students’ demographic characteristics and opinions about behaviors regarding sexual activity. In collaboration with Seufert, the survey was modified for use in the Pure & Simple Lifestyle (PSL) curriculum. For the PSL survey, twenty-two items were deleted from the original Ohio survey. These items were discarded because program staff felt that statements were too descriptive, which could make participants feel uncomfortable when providing their responses.

The resulting first version of the PSL survey consisted of 76 items (see Appendix). A 5-point Likert scale was used for 63 items to assess teens’ agreement level with statements about their beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors regarding sexual activity with higher scores reflecting strong agreement. Other variables inquired about parent-teen relationships, relationships with peers, and demographic characteristics about participants and their families. Altogether, survey items contained in the data set were categorized using the TBP groupings for beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and the decision to engage in sexual health behaviors.

2.3. Data Collection

Adolescents who consented to participate and whose parents provided corresponding parental consent were given the confidential, self-administered survey to complete. The consent process was in accordance with procedures set forth by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Kansas School of Medicine-Wichita. After completing the survey, participants put their answer sheets into a common, large envelope to secure anonymity of responses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Using SPSS Version 18.0, demographic characteristics for both intervention and comparison group were analyzed by using the chi-square statistic to determine if significant differences between groups would exist. Second, a reliability analysis was conducted to determine internal consistency among the survey items. Last, through iterative principal axis factoring, four factors were extracted and rotated to achieve a simple structure [30].

3. Results

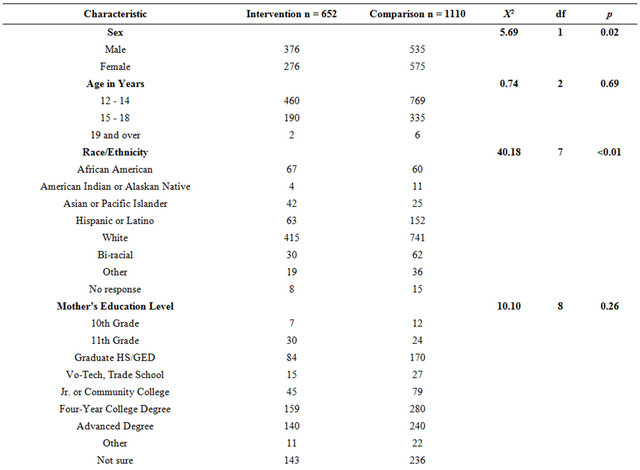

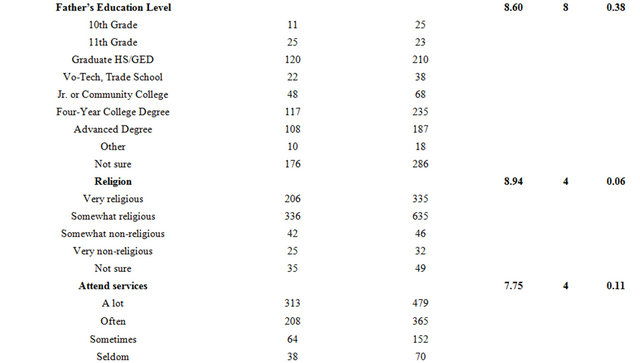

Table 1 displays demographic characteristics for the intervention and comparison groups. The chi-square value was not significant for age (X2 (df = 2) = 0.74, p = 0.69), mother’s education level (X2 (df = 8) = 10.10, p = 0.26), and father’s education level (X2 (df = 8) = 8.60, p = 0.38). These findings indicate that the distribution for each group was similar on age, mother’s education level, and father’s education level. Conversely, the chi-square value was significant for gender (X2 (df = 1) = 5.69, p = 0.02) and race (X2 (df = 7) = 40.18, p < 0.01). This finding shows that both groups differed in gender and racial diversity. There were a total of 1,762 respondents in both the intervention and comparison groups. About 52% of participants were male. Approximately 70% of respondents were between the ages of 12 and 14 years old. Racial/ethnic characteristics for both groups were: 66% White/Caucasian, 12% Hispanic/Latino, 7% African American/Black, and 4% Asian/Pacific Islander. Approximately 55% of respondents reported being somewhat religious while 31% of respondents reported being very religious. About 45% of participants indicated that they attend religious services a lot and about 33% indicated they attend often.

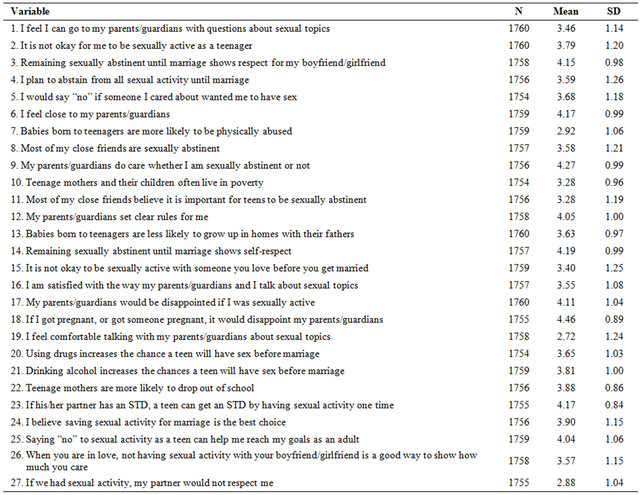

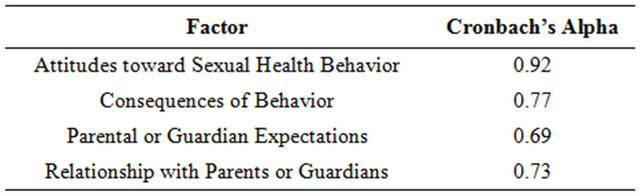

Table 2 shows the means and standard deviations for each variable. All values were within acceptable range. Table 3 demonstrates adequate internal consistency among the survey items within each factor as illustrated by Cronbach’s alphas of 0.69 or higher.

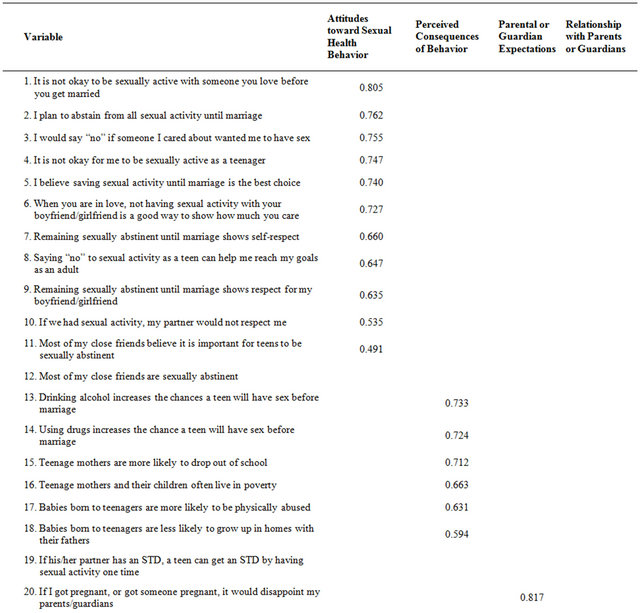

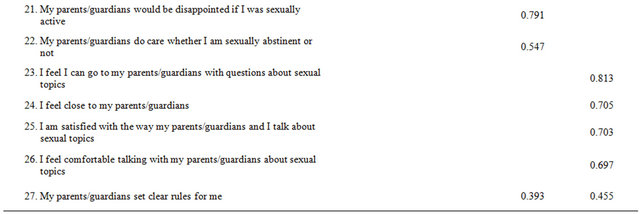

Table 4 shows the factor loadings of 27 selected survey items. Survey items contained participants’ attitudes and opinions regarding sexual behaviors. All survey items used Likert-type scales. The method used to extract the initial factor solution was iterative principal axis factoring. A visual scree plot was generated to determine the number of acceptable factors. Before rotation, four factors were extracted, which accounted for 52.53% of the total variance. These factors were subjected to Equimax rotation with Kaiser Normalization for enhanced interpretation and converged after six iterations. Variables with patterned weights less than 0.44 were excluded to facilitate interpretation of the factors. The final factors were identified as:

1) Teenagers’ attitudes toward sexual health behaviors;

2) Teenagers’ perceptions of the consequences of sexual health behaviors;

3) Parental or guardian expectations, and 4) Teenagers’ relationship with parents or guardians.

Two survey items (item number 12 and 19) did not meet the cut-off for a factor loading. One survey item (item number 27) cross-loaded and it was decided to include this item in the Relationship with Parents or Guardians factor rather than the Parental or Guardian Expectations factor.

The first factor, Attitudes toward Sexual Health Behaviors, consisted of eleven items and explored participants’ attitudes toward sexual health behaviors. The second factor, Perceptions of Consequences of Behaviors, consisted of six items and explored participants’ perceptions about long-term outcomes for teenage mothers and babies born to teenagers. Participants were also asked about the influence of alcohol and drugs on a teen’s deci-

Table 1. Demographics—participants in intervention and comparison group based on the 2009-2010 academic school year.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for each variable.

Table 3. Cronbach’s alpha for identified factors.

sion to engage in sexual activity. The third factor, Parental or Guardian Expectations, consisted of three items and explored participants’ perceptions about parental or guardian expectations regarding sexual activity and pregnancy. The fourth factor, Relationship with Parents or Guardians, consisted of five items and described the relationship between teenagers and their parents or guardians.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the underlying dimensions of a survey instrument that assesses a youth character development program. This program focuses on self-restraint from high-risk behaviors among adolescents such as sexual activity and the use of alcohol and/or drugs. Through iterative principal axis factoring, four factors were identified. Within the theoretical framework of the theory of planned behavior (TPB), behavior is described as being dependent on someone’s intention and perceived ability so that intentions will only be expressed in behaviors if the person voluntarily decides to perform or not perform the behavior. Against this background, this study’s results indicate that all four factors can be described within Ajzen’s theoretical framework consistent with previous research findings [11,12,18,31].

4.1. Factor 1—Teenagers’ Attitudes toward Sexual Health Behaviors The first factor demonstrates that attitudes toward sexual activity appear relevant to the outcome consistent with the TBP model [11,12,18,24-27,31]. Respondents generally believe that refraining from sexual activity leads to respect among peers, including respect for self, as well as the ability to reach goals in life. Specifically, this study’s

Table 4. Participants’ responses pattern matrix from principal axis factoring with Equimax rotation and Kaiser normalization.

findings demonstrate that adolescents who value restraint from sexual activity through respect of self and others are less likely to engage in sexual behaviors. Even though the literature on personal values in relation to sexual intercourse supports this finding, there is little empirical evidence how respect toward the self and others play into refraining from sexual activity [32-34].

Furthermore, in their evaluation of a year-long abstinence education program, Helitzer and colleagues [22] used exploratory factor analysis to identify a factor similar to the one reported here. Using similar factor analytic techniques, Cuffee and colleagues [20] found comparable results when they reported increased protective attitudes toward sexual activity through gender and race-specific programs. In short, the first factor identified in this study is consistent with findings from other research studies demonstrating that adolescents who hold positive attitudes toward refraining from sexual intercourse would delay onset of sexual debut or were less likely to engage in sexual behavior [17,35,36].

4.2. Factor 2—Teenagers’ Perceptions of the Consequences of Sexual Health Behaviors The second factor examines participants’ perceptions about long-term outcomes as well as the influence of alcohol and drugs on a teenager’s decision to engage in sexual activity. Behavioral beliefs on refraining from sexual activity connect adolescent sexual activity to probable outcomes such as teenage mothers’ increased likelihood of dropping out of school, living in poverty, physical abuse of the child, and the child growing up without a father in the home. In short, abstinence beliefs in combination with these subjective values of perceived outcomes for teenage mothers determine whether an adolescent engages in sexual activity. Also, teenagers’ in this study perceived the use of alcohol and drugs as leading to an increased likelihood to engage in sexual activity consistent with existing literature [22,34].

Whereas Helitzer and colleagues [22] identified a separate factor containing high-risk behaviors that is associated with early sexual debut (Use of Tobacco/ Alcohol/ Drugs/Sex), this study combined these elements into one factor labeled Consequences of Behaviors. In other words, this study’s factor shows an increased likelihood of engaging in sexual activity after the use of alcohol and/or drugs as well as the perceived costs of what happens to teenage girls after they give birth. This finding demonstrates that teenagers consider the costs of engaging in sexual activity and the outcome of birthing a child as critical. More importantly, this result may have implications for the design of intervention programs. In addition to the long-term outcome of preventing pregnancy or sexually transmitted diseases, intervention programs should also focus on how perceived costs of teenage pregnancy affect a teenager’s decision making process.

4.3. Factor 3—Parental or Guardian Expectations The third factor measures participants’ perceptions about parental or guardian expectations to sexual activity. Parental expectations subsequently influence a teenager’s decision to refrain from sexual activity [37,38]. According to the TPB model, sexual health behavior can be explained as 1) a teenager’s voluntary decision to engage or not engage in sexual activity referred to as “perceived behavioral control” and 2) the expectations regarding sexual behaviors of a critical reference group referred to as “subjective norms.” Through communication with their parents or guardians, teenagers learn expected behaviors surrounding sexual activity including restraint from sexual activity.

In this study, teenagers use their parents as the reference group when deciding to engage or not engage in sexual activity. These research findings demonstrate that when teenagers use their parents or guardians as a reference group that expresses disappointment if a teenager engages in sexual activity, teenagers are more likely to say “no” to sexual activity. The knowledge that teenagers have their parents’ or guardians’ approval to say “no” may provide them with the power to say “no” to sexual activity when pressured by peers. One of the key focal points in high-risk behavioral interventions such as the one discussed in this study is to direct teenagers’ attention to the parents or guardians and use them as their reference group particularly when this group expresses pro-abstinence values.

4.4. Factor 4—Relationship with Parents or Guardians The fourth factor, Relationship with Parents or Guardians, falls somewhat outside of Ajzen’s theoretical framework. The literature supports the claim that a quality relationship with parents including open communication about sexual topics reduces the likelihood of a teenager engaging in sexual activity [39,40]. This study’s findings add to an emerging body of research demonstrating the importance of the parent-adolescent relationship. Furthermore, this study’s program, the Pure & Simple Lifestyle (PSL) curriculum, emphasizes parental/ guardian relationship quality by providing special classes for parents/guardians in conjunction with their curriculum for adolescents. In particular, parents/ guardians are encouraged to have open communication with their teenager about the consequences of high-risk sexual behaviors and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Moreover, this finding has implications for the design of future youth character development programs in that the parental/guardian relationship should not be discounted and more effort should be directed toward incorporating the family structure when addressing adolescent high-risk behaviors.

5. Conclusions

Overall, there are a variety of statistical methods that can be used to evaluate an intervention. This study differs from others in that the application of factor analysis to a dataset has not yet enjoyed widespread use among evaluators of youth character development programs. Results from factor analysis can be used to assess program performance so that administrators may enhance delivery of the intervention rather than wait until it has been completed. Furthermore, factor analysis can be used to produce a more precise instrument. As reliability and validity of the core content of this study’s survey instrument were maintained, a shorter survey could contribute to greater completion of survey items and number of surveys collected.

One of the main limitations of this study is participants’ self-reported scores on the survey items. Social desirability in participants’ responses plays a role especially during young adolescence, a stage of development when conforming to peer pressure appears more important than at any other time during the life cycle. Another limitation points to volunteer bias in that the survey instrument was limited to the schools that were recruited and consented to participate. Furthermore, participants represented a student body from the country’s Midwestern region that reflects the region’s racial diversity and religious dimensions.

In addition to using a less traditional statistical procedure to evaluate interventions, this study adds to the body of adolescent sexual health literature in various ways. Specifically, the following findings set it apart from other studies in this field:

1) Through respect for self and others, adolescents are less likely to engage in sexual activity;

2) Teenagers view the costs of engaging in sexual activity as critical and this perception affects their decision making process to engage in sexual activity;

3) Parental abstinence values influence a teenager’s decision making process especially if the adolescent values the opinions of this reference group; and 4) Having a quality relationship with their parents/ guardians including open communication about sexual topics reduces adolescents’ likelihood to engage in sexual activity.

Further areas of study for future research on adolescent sexual activity point to examination of respect for self and others, perceptual processes of the costs of sexual activity and the adolescent’s decision making process, and the influence of the relationship between teenagers and their parents or guardians.

6. Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a three year Community Based Abstinence Education (CBAE) grant from the Abstinence Education Division of the Family and Youth Services Bureau (FYSB), Administration on Children, Youth and Families (ACYF), US Department of Health and Human Services (grant number 90AE0085).

The authors wish to thank Sandra E. Pickert, RN, MPH, BSN, executive director of Pure & Simple Health Education, Inc. for her continued support and participation in the evaluation of the organization’s healthy lifestyles youth development program.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,” DHHS Publication No. 2010-623-026/41246, US Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 2010.

- H. Weinstock, S. Berman and W. Cates, “Sexually Transmitted Diseases among American Youth: Incidence and Prevalence Estimates, 2000,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2004, pp. 6-10. doi:10.1363/3600604

- S. E. Forhan, S. L. Gottlieb, M. R. Sternberg, F. Xu, S. D. Datta, G. M. McQuillian and L. E. Markowitz, “Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Infections among Female Adolescents Aged 14 to 19 in the United States,” Pediatrics, Vol. 124, No. 6, 2009, pp. 1505-1512. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0674

- H. W. Chesson, J. M. Blandford, T. L. Gift, G. Tao and K. L. Irwin, “The Estimated Direct Medical Cost of Sexually Transmitted Diseases among American Youth, 2000,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2004, pp. 11-19. doi:10.1363/3601104

- B. E. Hamilton, J. A. Martin and S. J. Ventura, “Births: Preliminary Data for 2008,” National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 58, No. 16, 2012, 20 Pages.

- E. K. Adams, N. I. Gavin, M. F. Ayadi, J. Santelli and C. Raskind-Hood, “The Costs of Public Services for Teenage Mothers Post-Welfare Reform: A Ten-State Study,” Journal of Health Care Finance, Vol. 35, No. 3, 2009, pp. 44-58.

- S. Jaffee, A. Caspi, T. E. Moffitt, J. Belsky and P. Silva, “Why Are Children Born to Teen Mothers at Risk for Adverse Outcomes in Young Adulthood? Results from a 20-Year Longitudinal Study,” Development and Psychopathology, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2001, pp. 377-397. doi:10.1017/S0954579401002103

- D. P. Jutte, N. P. Roos, M. D. Brownell, G. Briggs, L. MacWilliam and L. L. Roos, “The Ripples of Adolescent Motherhood: Social, Educational, and Medical Outcomes for Children of Teen and Prior Teen Mothers,” Academic Pediatrics, Vol. 10, No. 5, 2010, pp. 293-301. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.008

- B. R. Flay, S. Graumlich, E. Segawa, J. L. Burns and M. Y. Holliday, “Effects of 2 Prevention Programs on HighRisk Behaviors among African American Youth: A Randomized Trial,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, Vol. 158, No. 4, 2004, pp. 377-384. doi:10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377

- P. W. Greenwood, “Cost-Effective Violence Prevention through Targeted Family Interventions,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1036, 2004, pp. 201- 214. doi:10.1196/annals.1330.013

- J. B. Jemmott, L. S. Jemmott and G. T. Fong, “Abstinence and Safer Sex HIV Risk-Reduction Interventions for African American Adolescents,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 279, No. 19, 1998, pp. 1529-1536. doi:10.1001/jama.279.19.1529

- J. B. Jemmott, L. S. Jemmott and G. T. Fong, “Efficacy of a Theory-Based Abstinence-Only Intervention over 24 Months,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, Vol. 164, No. 2, 2010, pp. 152-159. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.267

- K. L. Kumpfer, R. Alvarado, P. Smith and N. Bellamy, “Cultural Sensitivity and Adaptation in Family-Based Prevention Interventions,” Prevention Science, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2002, pp. 241-246. doi:10.1023/A:1019902902119

- C. E. Collins, D. L. Whiters and R. Braithwaite, “The Saved Sista Project: A Faith-Based HIV Prevention Program for Black Women in Addition Recovery,” American Journal of Health Studies, Vol. 22, No. 2, 2007, pp. 76- 82.

- S. E. Pickert, R. Wetta-Hall, A. Chesser, T. A. Hart, R. E. Crowe and L. M. Theis, “Criteria-Based Development of a Teen-Directed Abstinence-Centered Curriculum,” American Journal of Health Studies, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2009, pp. 386-400.

- D. E. Clemons, R. Wetta-Hall, L. T. Jacobson, A. Chesser and A. Moss, “Does One Size Fit All: Culturally Appropriate Teen Curriculum for Risk Behaviors,” American Journal of Health Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2011, pp. 45- 56.

- E. R. Buhi and P. Goodson, “Predictors of Adolescent Sexual Behavior and Intention: A Theory-Guided Systematic Review,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2007, pp. 4-21. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027

- E. S. Cha, W. M. Doswell, K. H. Kim, D. Charron-Prochownik and T. E. Patrick, “Evaluating the Theory of Planned Behavior to Explain Intention to Engage in Premarital Sex amongst Korean College Students: A Questionnaire Survey,” International Journal of Nursing Studies, Vol. 44, No. 7, 2007, pp. 1147-1157. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.04.015

- C. L. Thomas and D. M. Dimitrov, “Effects of a Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program on Teens’ Attitudes toward Sexuality: A Latent Trait Modeling Approach,” Developmental Psychology, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2007, pp. 173-185. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.173

- J. J. Cuffee, D. D. Hallfors and M. W. Waller, “Racial and Gender Differences in Adolescent Sexual Attitudes and Longitudinal Associations with Coital Debut,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2007, pp. 19-26. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.02.012

- M. Foster Cox, T. K. Fasolino and A. S. Tavakoli, “Factor Analysis and Psychometric Properties of the MotherAdolescent Sexual Communication (MASC) Instrument for Sexual Risk Behavior,” Journal of Nursing Measurement, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2008, pp. 171-183. doi:10.1891/1061-3749.16.3.171

- D. Helitzer, C. Hollis, B. Urquieta de Hernandez, M. Sanders, S. Roybal and I. Van Deusen, “Evaluation for Community-Based Programs: The Integration of Logic Models and Factor Analysis,” Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol. 33, No. 3, 2010, pp. 223-233. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.08.005

- N. H. Busen and K. Kouzekanani, “Perspectives in Adolescent Risk-Taking through Instrument Development,” Journal of Professional Nursing, Vol. 16, No. 6, 2000, pp. 345-353. doi:10.1053/jpnu.2000.18174

- I. Ajzen, “From Intentions to Actions: The Theory of Planned Behavior,” In: J. Kuhl and J. Beckmann, Eds., Action-Control: From Cognition to Behavior, Springer, Berlin, 1985, pp. 11-39.

- I. Ajzen, “The Theory of Planned Behavior,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50, 1991, pp. 179-211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- I. Ajzen and M. Fishbein, “Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 1980.

- M. Fishbein and I. Ajzen, “Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research,” Addison Wesley, Boston, 1975.

- T. J. Madden, P. S. Ellen and I. Ajzen, “A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992, pp. 3-9. doi:10.1177/0146167292181001

- R. L. Seufert, “Ohio Department of Health Abstinence Education Program Survey,” Applied Research Center of Miami University, Middletown, 2004.

- R. L. Gorsuch, “Factor Analysis,” Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc., Mahwah, 1983.

- L. S. Jemmott, J. B. Jemmott and M. K. Hutchinson, “HIV/AIDS: Prevention Needs and Strategies for a Public Health Emergency,” In: R. Braithwaite, Ed., Health Issues in the Black Community, 2nd Edition, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2001, pp. 309-346.

- C. Dilorio, W. N. Dudley, J. E. Soet and F. McCarty, “Sexual Possibility Situations and Sexual Behaviors among Young Adolescents: The Moderating Role of Protective Factors,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 35, No. 6, 2004, pp. 528-537.

- L. Blinn-Pike, “Why Abstinent Adolescents Report They Have Not Had Sex: Understanding Sexually Resilient Youth,” Family Relations, Vol. 48, No. 3, 1999, pp. 295-301. doi:10.2307/585640

- L. Blinn-Pike, T. J. Berger, J. Hewett and J. Oleson, “Sexually Abstinent Adolescents: An 18-Month FollowUp,” Journal of Adolescent Research, Vol. 19, No. 5, 2004, pp. 495-511. doi:10.1177/0743558403259987

- E. R. Buhi, P. Goodson, T. B. Neilands and H. Blunt, “Adolescent Sexual Abstinence: A Test of an Integrative Theoretical Framework,” Health Education & Behavior, Vol. 38, No. 1, 2011, pp. 63-79. doi:10.1177/1090198110375036

- N. T. Masters, B. A. Beadnell, D. M. Morrison, M. J. Hoppe and M. Rogers Gillmore, “The Opposite of Sex? Adolescents’ Thoughts about Abstinence and Sex, and Their Sexual Behavior,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2008, pp. 87-93. doi:10.1363/4008708

- G. F. Watts and S. Nagy, “Sociodemographic Factors, Attitudes, and Expectations toward Adolescent Coitus,” American Journal of Health Behavior, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2000, pp. 309-317. doi:10.5993/AJHB.24.4.7

- P. J. Dittus and J. Jaccard, “Adolescents’ Perceptions of Maternal Disapproval of Sex: Relationship to Sexual Outcomes,” Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2000, pp. 268-278. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00096-8

- C. B. Aspy, S. K. Vesely, R. F. Oman, S. Rodine, L. Marshall and K. McLeroy, “Parental Communication and Youth Sexual Behaviour,” Journal of Adolescence, Vol. 30, No. 3, 2007, pp. 449-466. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.007

- D. P. Deptula, D. B. Henry and M. E. Schoeny, “How Can Parents Make a Difference? Longitudinal Associations with Adolescent Sexual Behavior,” Journal of Family Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 6, 2010, pp. 731-739. doi:10.1037/a0021760

NOTES

*Corresponding author.