International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.2 No.5(2011), Article ID:8766,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2011.25088

Can Provision of Health Information Lead to Healthier, Longer Lives?

![]()

1University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, USA; 2Pueblo City-County Health Department, Pueblo, USA; 3Colorado State University, Pueblo, USA.

Email: ckbartecchi@gmail.com

Received August 28th, 2011; revised September 30th, 2011; accepted October 25th, 2011.

Keywords: Health

ABSTRACT

As health promoters, we seek ways to direct our patients and the public to those activities that will lead to a healthier and longer life. Many programs have been tried with relatively small groups of individuals, with limited or unsustained success. This study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of providing free, quality, unbiased, frequently updated, untainted, easily accessible information to an entire community (Pueblo, Colorado) of 60,000 households. The study showed that certain groups, namely the better educated, health care workers and females benefitted most from the health information provided them. Whether the population most in need of such information was effectively reached remained unanswered due to lack of feedback from this targeted group. This study provided some valuable insights into the various challenges that one faces in trying to develop a better health-informed, participating population. It also suggests the need to continue to search for an effective way to produce the desired changes in health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Health promoters and educators encourage individuals to do the “right things”, so they will be healthier and live longer. At the same time, however, most people don’t know or are unsure of just what are the “right things”. And sometimes, what is to be included in the category of “right things” is not always clear. Certainly, not smoking, exercising and maintaining an ideal weight would make anyone’s list of “right things”. Other items however may not be so clear cut—what type of diet for weight reducetion, the need for dietary supplements, when and how often women should have mammograms, and the value of Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) testing in men.

There is no shortage of advice for the individual desiring to do the “right things”. Books, magazines, radio, television, the Internet, friends and family members are all there to influence the selection of “right things”. Unfortunately, many of these influences can be faulted by incorrect, unscientific, without adequate research, biased, anecdotal, outdated or implausible information. Individual or corporate profit motive is often behind questionable health related recommendations. Such recommendations, skillfully packaged by clever marketers, are readily devoured by people unwilling to put the thought, time, and effort into doing the “right things”. Instead they desire a “pill” or a short-cut to achieving a healthier and longer life. Unfortunately, there are plenty of “providers” out there, ready, willing, and able to take advantage of this population.

Few would deny that the problem is getting worse. Our population is getting older, heavier, lazier, and they persistently embrace bad habits. For example, there are 50 million smokers in the United States and 30% of U.S. adults drink too much. All this results in major diseases and shortened life spans, at great expense to a society already burdened with financial stresses and strains [1].

Health care professionals desire to determine what can be done about our health care dilemma. Is government intervention the answer? In Vietnam, the government mandated a helmet law for all motorbike riders that led to a significant decrease in head injuries and deaths from motorbike accidents [2]. This approach however doesn’t appeal much to the populace in the United States. Smoking bans and clean air laws, however, have prevented heart attacks in the U.S. and other countries [3,4]. Should people be paid to adopt healthy habits, or maybe lower their health insurance costs? Incentives have worked with smokers [5] and overweight individuals [6], but often, when financial incentives stop, smokers and the obese return to their former habits. Should the focus be on the education of our children—teaching them healthy habits from the earliest effective grade school years? However, such education of our children would be even more beneficial if we could educate their parents, and ideally, the entire adult population.

Educating the entire adult population on healthy behaviors is not an easy task. First of all, what venue and teaching style is the most appropriate for large audiences? Some individuals learn better orally while others need visual cues. Is utilizing the Internet and social networking the answer? In addition, how could we require mandatory attendance? Our society prides itself on choices and freedom of choice. Classroom teaching efforts are expensive, require skilled teachers and would be burdensome time-wise. Media education (radio and television) would have similar problems. Printed educational materials are expensive, need to be read by busy people with other time commitments, are outdated quickly, and are not always consumed by the public. Our goal is to put forth a cost effective approach that has worked in a motivated population.

2. Methods

Feeling that it would be advantageous to provide free of charge, high quality, frequently updated, easily read, useful and untainted information, the authors of the book “Living Healthier and Longer—What Works, What Doesn’t” took a unique approach to health education. They sought financial assistance from foundations, hospitals, business, and individual entities who were willing to forego any contribution or input into the proposed text. Seven organizations accepted the challenge and supported its production. These organizations (shown in the Acknowledgements) and the authors agreed that no entity should profit in any way from the distribution of the book, its updates or its information. The goal was to impact the health of 150,000 people of Pueblo County, a population center in Southern Colorado.

The authors determined that the health information contained in the book should come from the highest quality academic resources. These resources included the following:

1) Medical Journals

New England Journal of Medicine Journal of the American Medical Association The Lancet British Medical Journal Annals of Internal Medicine Archives of Internal Medicine Circulation American Journal of Cardiology Journal of the American College of Cardiology

2) Publications and documents from major medical centers

Berkeley Wellness Letter Harvard Health Letter Harvard Heart Letter Health after 50, The Johns Hopkins Medical Letter Mayo Clinic Health Letter Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter The Medical Letter Nutrition Action Health Letter

3) Web sites sponsored by the CDC, NIH, FDA, Quackwatch

4) Symposia and meetings sponsored by major medical centers and the American College of Physicians

To insure the most up-to-date information, the original text was completed and the contents reviewed over a fourmonth period at an approximate cost of $1.00 per copy. Using a small, local publisher, supported by a large Denver printer, 60,000 free copies of the 224 page book were available for distribution in a two-month period. The leadership of the Pueblo City-County Health Department was solicited in deciding on a course of action that would determine the value of providing authoritative health information “free” to a selected population. Every effort was made to provide a free copy of the book to the approximate 60,000 households in Pueblo. Books were distributed locally through libraries, churches, the Pueblo CityCounty Health Department, supermarkets and pharmacies, Pueblo newspaper offices, physician’s offices, the two community hospitals, schools, nursing homes, neighborhood clinics, health fairs, political rallies, service club meetings, business meetings, senior programs, YMCA, YWCA, and book related meetings encouraged the use of the on-line book “Updates” (every 6 months) as well as in radio and newspaper advertisements.

The goal was to determine if the book, once in the hands of the households of the Pueblo community, was read by household members and if any value could be detected resulting from their possession of this newly acquired health information. Many variables were considered.

1) Did individuals who were given books bring the book home and did they read the book?

2) Were there any positive changes made after reading the book?

3) Were the book and its contents shared with other family members?

4) Did readers gain any value from the book’s contents and frequent “updates”?

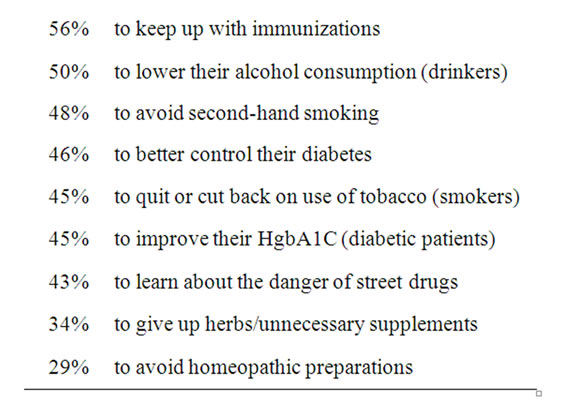

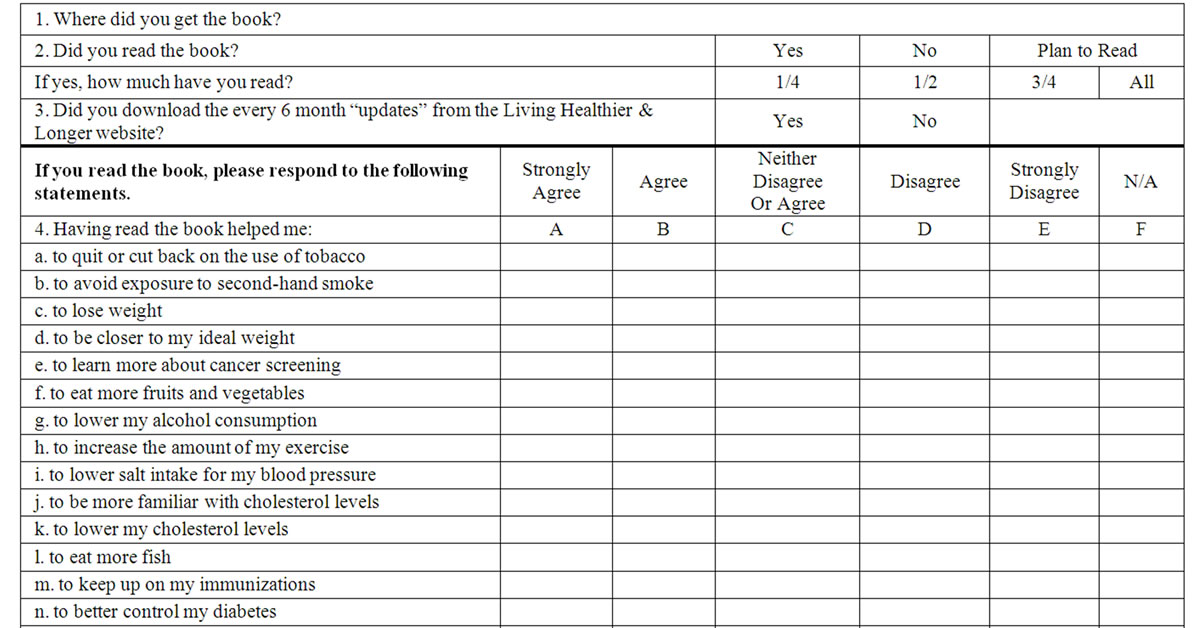

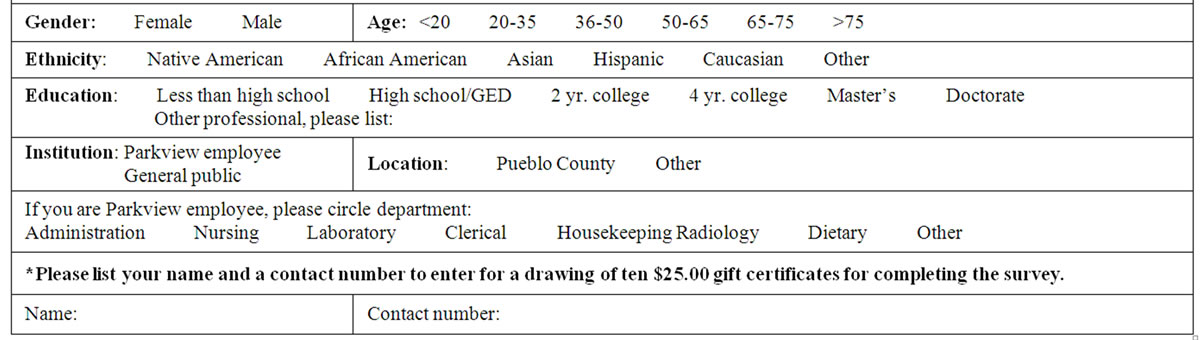

Survey Design The survey was designed to evaluate the impact of the book on the Pueblo community. A set of questions was developed by the authors, members of the Pueblo CityCounty Health Department, and a survey researcher. The survey consisted of demographic information and questions on the impact of the book. Feedback was measured through the five-point Likert Scale [7].

3. Results

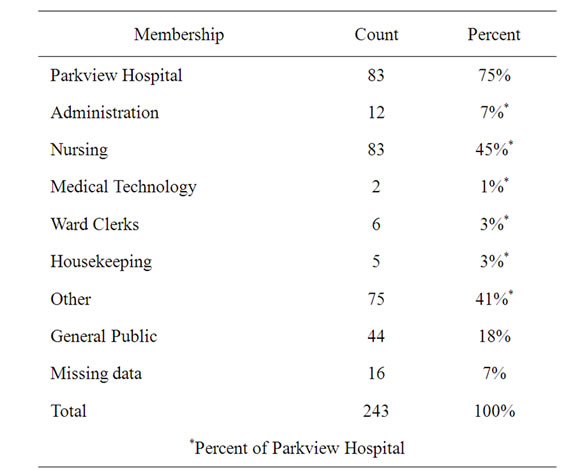

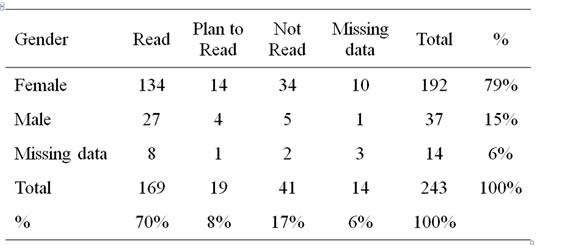

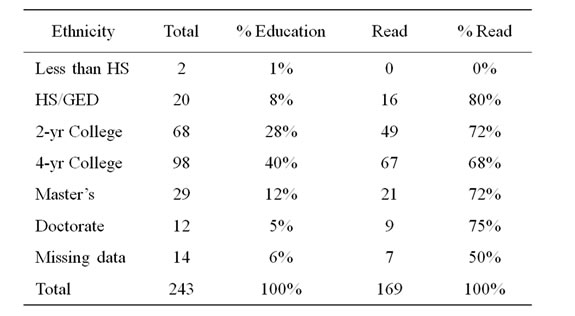

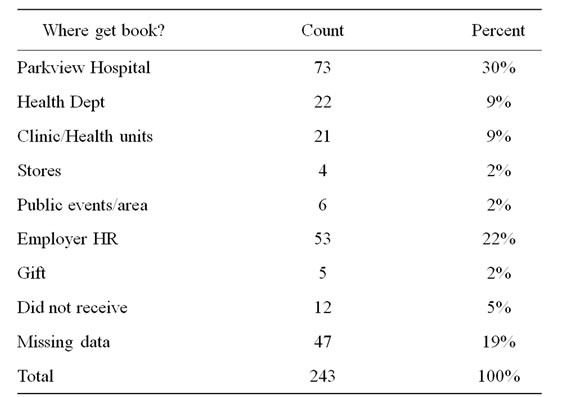

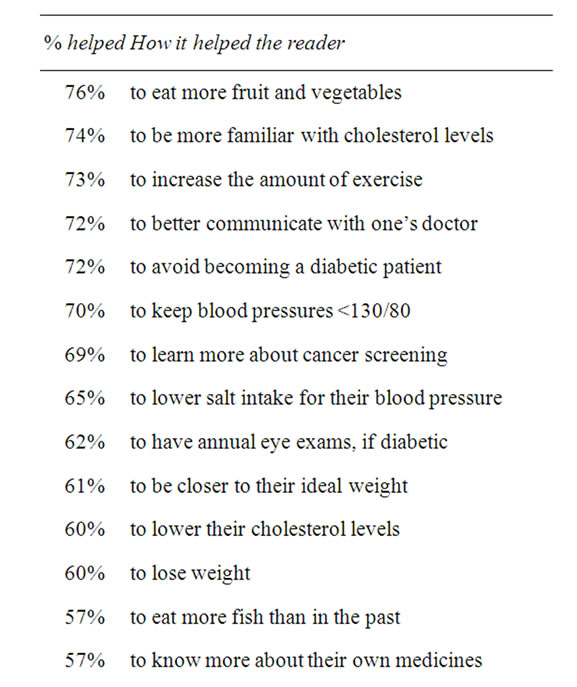

In Table 1 are shown the distribution of the sites which responded to the survey. Seventy-five percent of responders were from Parkview Hospital (183 of 243). The nurses at the hospital were particularly good responders to the survey. In Table 2 are shown the responders by gender. Clearly, women predominated over men with respect to having read the book. This is of interest, since women are known to have a longer lifespan than men in the United States (78 versus 75 years average). In Table 3 is shown the level of education of the responders. Fewer high school graduates responded, but the ones that did tended to read the book. Clearly those responders with some college or higher education were more likely to read the book. In Table 4 are shown the respondents by ethnicity. Caucasians predominate, but of interest, 21% of respondents were Hispanic. Of note, recent data indicate that Hispanics have a longevity from birth in the United States greater than Caucasians (80.8 versus 78.2 years). The percentage of readers increased with age, 58% for ages 20 - 35; 71% for ages 36 - 50; 75% for ages 50 - 65 and above. Among hospital employees 100% of those who worked in administration responded, 69% in nursing, and 62% in other areas of the hospital. Thus, working in a health care environment appears to be an incentive for learning about living a longer and healthier life. In Table 5 are shown the sources whereby individuals obtained “Living Healthier and Longer—What Works, What Doesn’t.” Again, of those who responded 48% received the book when they were in a health care environment. In Table 6 are shown

Table 1. Sites of survey response.

Table 2. Survey respondents by gender.

Table 3. Respondents by education.

Table 4. Survey respondents by ethnicity.

Table 5. Source of the book.

Table 6. Value of book to respondents.

self-reported assessments of whether the book helped them to live a longer and healthier life. Percentages of “strongly agree” and “agree” responses were combined. The analysis was based on those who read either part or the whole book. The majority of the respondents believed the book would help them live a longer and healthier life. See Figure 1 for the full survey.

Surveys were administered through both on-line and paper copies. The on-line survey was posted by “Survey Monkey”, an on-line software. The on-line survey and its web link were marketed through the local Pueblo newspaper and the web site. Paper copies were distributed to local institutions, health department staff, businesses, and Parkview Medical Center. About 2200 surveys with return envelopes and postage were mailed to the Parkview Hospital employees. Ten $25.00 gift certificates were used as incentives (through random drawings) to encourage respondents to complete surveys.

4. Discussion

Though anecdotal, responses from the author’s personal patients and contacts and other physicians in the community, those to whom we personally explained the book and its goals, were quite positive. Other physicians who distributed the book noted the same. However, more than anecdotal evidence was necessary to assess the book’s value. A survey of each member of the 2000+ staff of the Parkview Hospital was selected because the Hospital chose to mail a copy of the book to each employee’s home address. The book was accompanied by a letter explaining the goal of the book and the availability of periodic updates. Also, there was easy access to all employees for a follow-up survey.

The need for more effective patient education is characterized by the situation with the 65 million Americans with hypertension. One of the most treatable factors to decrease the incidence of atherosclerosis, acute heart attacks, stroke, and cardiac failure is hypertension. Yet over the past ten years the National Health and Nutrition Exam survey (NHANES) indicates that only an average of ten percent of hypertensive patients in the United States have their blood pressure controlled to less than 140/70 mmHg, let alone less than 130/80 mmHg. The other patients did not have their blood pressures controlled to less than 140/90 mmHg in spite of the availability of over one hundred antihypertensive medications. Moreover, millions of dollars have been spent in the United States by numerous government and non-government organizations to educate the population about the importance of effectively treating hypertension.

Various educational vehicles have been used including television, radio, magazines, books, lectures, conferences, etc. to educate the public about how to enhance their health, yet there has been very little improvement over the last decade in the treatment of hypertension. Another approach was used in the present study. Rather than exposing a population to a message for a snapshot in time on television or on the Internet, in a newspaper or magazine, or at a physician visit, they had the continuous availability of high quality, non-commercial health information (without cost) in a book by medical experts. Thus, rather than a single exposure, there would be continuous access of information that consolidates the major issues relative to maintenance of optimal health and disease prevention in individuals.

The present study evaluated this possibility using, “Living Healthier and Longer—What Works, What Doesn’t” [8] a book which received a very favorable review [9] in the New England Journal of Medicine. Noncommercial support was obtained with a goal of providing this book without cost to every one of the 60,000

Figure 1. Living longer survey.

families in the Pueblo community, a Colorado city with a population of 150,000. Moreover, the book was made available on the Internet with updates every six months to insure that current, up-to-date, high quality information is available in every home. Of interest, over the last year there were 14,000 downloads of the book from 140 different countries. Furthermore, permission was granted for translations of the book from China, Japan, and Vietnam.

Much was learned from this approach. First, printing large quantities of the book without an intermediary decreased the real costs of the book from approximately $20 to $1.00. Manually distributing the books to various sites to decrease the cost of the project, as compared to mailing the book to each household, was labor intensive and less effective. The mailing of the books to each household would have added approximately $.50 for each book, but no doubt would have been more effective. This was confirmed by the Parkview Hospital experience where every employee received the book by mail.

The survey results were revealing. Women and individuals employed in a health care environment were more likely to read the up-to-date health care information. Also those individuals with more formal education were more likely to read the book. Whether individuals who received the book continued to refer to various sections of the book when health care questions arise cannot be assessed by the survey. Nevertheless, the information continues to be available in contrast to multimillion dollar projects that have used the one-time snapshot in time approach.

Unfortunately, we were unable to document that the segment of the population in most need of health maintenance and disease prevention information was reached by our approach. This includes the poor, medically indigent, disadvantaged and the elderly who are frail, homebound or sickly. In addition, many young adults do not read books and only access health information from the internet, if at all. How to better access these segments of society with up-to-date health care information is an important challenge. Another disappointing aspect to the project was the failure of those who received the book to access the online six month updates. Perhaps they read them on the computer, but did not download the updates. Why men, who in contrast to women, who have more hypertension, alcoholism, tobacco abuse, and earlier deaths, seem to have less interest in obtaining information about health maintenance and disease prevention is another question raised by the survey. This dilemma is difficult to understand.

How to better educate the country’s population with respect to participating in their own health maintenance and disease prevention, not just relying on health care providers, is an enormous challenge. The approach of this study does not appear to be the answer, but does provide some insights into the various challenges of having a better informed, involved population. Others have noted “that risk information on its own is not effective and needs to be coupled with other tools to promote healthy behavior” [10]. A recent systemic review demonstrated that “information alone is not an effective way to produce desired changes in health outcomes and much remains to be learned” [11]. It is, however, a beginning.

“You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink”—Old English Homilies c. 1175.

REFERENCES

- J. F. Wilson, “Can Disease Prevention Save Health Reform?” Annals of Internal Medicine, Vol. 151, No. 2, 2009, pp. 145-147.

- Global Road Safety Partnership, “Helmet Law and Enforcement,” GRSP, Vietnam, 11 May 2009.

- C. E. Bartecchi, R. N. Alsever, C. Nevin-Woods, et al., “Reduction in the Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction Associated with a Citywide Smoking Ordinance,” Circulation, Vol. 114, 2006, pp. 1490-1496. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615245

- J. M. Samet, “Smoking Bans Prevent Heart Attacks,” Circulation, Vol. 114, 2006, pp. 1450-1451. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.649103

- K. G. Volpp, A. B. Troxel, M. V. Pauly, et al., “A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 360, No. , 2009, pp. 699-708. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0806819

- K. G. Volpp, L. K. John, A. B. Troxel and L. Norton, “Financial Incentive-Based Approaches for Weight Loss,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 300, No. 22, 2008, pp. 2631-2637. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.804

- R. Likert, “A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes,” Archives of Psychology, Vol. 22, No. 140, 1932, pp. 1-55.

- C. E. Bartecchi and R. W. Schrier, “The Science and Art of Living a Longer and Healthier Life,” EMIS Inc., Durant, 2000.

- R. S. Lawrence, “Living Healthier and Longer: What Works, What Doesn’t,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 359, 2008, pp. 2852-2853. doi:10.1056/NEJMbkrev0805085

- S. L. Sheridan, A. J. Viera, M. J. Krantz, et al., “The Effect of Giving Global Coronary Risk Information to Adults: A Systemic Review,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 170, No. 3, 2010, pp. 230-239. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.516

- T. Ahmad and S. Mora, “Providing Patients with Global Cardiovascular Risk Information,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 170, No. 3, 2010, pp. 227-228. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.502