Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.06 No.02(2016), Article ID:64806,17 pages

10.4236/ojml.2016.62005

Speech Assessment for UIDE EFL Students: The IPA Case

―General-American English IPA Transcription to Assess Universidad Internacional del Ecuador EFL Students

Jorge Romero

Department of Languages, Universidad Internacional del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 January 2016; accepted 19 March 2016; published 22 March 2016

ABSTRACT

This Teaching English as the target second language involves several considerations which have to do with both the source language of speakers and the kind of training these students go through. In this particular case study, I have considered native speakers of Spanish who study English as a second language and identified, through two vowel sounds forming a minimal pair, that phonemes of General American English which are more likely to be mispronounced, is not only due to the fact that the English vowel system is more complex than that of Spanish, but also, and most important for this particular case study, that training is not consistent in contrastive exercising as it is in distribution exercising. In fact the English system has 20 vowel phonemes in Received Pronunciation, from 14 to 16 vowel phonemes in General American English and even 20 to 21 vowel phonemes in Australian English, while Spanish has only 5 vowel phonemes. The findings of this research account for the conclusion that exercising reinforcement need to be addressed and focused not only on the phonemes of the English vowel system which native speakers of Spanish have more trouble with, but also and more relevant in this research, that new and creative distribution exercising must be included in textbooks to help students master the English vowel sounds in order to avoid accent due to Spanish interference through quality English teaching.

Keywords:

Linguistics, Languages, Phonetics, Phonology, Language Teaching, Language Learning, EFL, Language Assessment, Pronunciation, IPA, Phonology Assessment

1. Introduction

1.1. Why Assessing EFL Students

This my twelve-year experience teaching in three Ecuadorian universities and five other foreign universities has motivated me to investigate why many university students, though having an acceptable knowledge of English, cannot master the basic vowel sounds of general English. I usually test my students through oral performances, which have allowed me to conclude that they need to work more on their individual pronunciation. My students’ final speeches have been very satisfactory under the communicative and structural point of view; however, when I reviewed their recorded oral presentations, there were up to 28 common sound mispronunciations including consonant sounds. Seventy-three percent of the mispronounced sounds were vowel phones; therefore, I have decided to concentrate on the vowel phonemes for this preliminary research paper. The results of this investigation will be used to conclude a second publication (a textbook) titled: “Let’s Master the English Vowel Sounds in Ten Lessons” and a series of new charts classifying the vowel sounds, addressed towards International University of Ecuador students.

1.2. Main Thesis

Most of the books used to teach English include vowel sound practice, but only a few of them include vowel contrast exercising and/or associative sound spelling. Simple vowel distribution drills are not enough to support the sound internalization process. Vowel contrastive drills, on the other hand, help students differentiate between the subtle changes of the various and complex English vowel sounds1. Another way to help English learners master these sounds is to create a link between what is said and what is written (Burquest, 2006) . This will help them predict the correct pronunciation by making sound-spelling generalizations. The best way to learn the General American English vowel system is to directly expose the students to the sounds studied (Roach, 2001) ; however, if we are to focus on the correct pronunciation through accent suppression, we have to recur to other supporting techniques such as exposing the students not only to distribution exercises and contrastive exercises, but also to predictive pronunciation based on tendentious sound spellings.

1.3. The IPA Case

Even though there are many transcription systems, the International Phonetic Alphabet is the most diffuse (International Phonetic Association, 1999) and probably the best-known by most of teachers and students in Ecuador. Its symbols―phonemes, allophones, suprasegmentals and diacritics―are the result of years of research and agreement by the International Phonetic Association (International Phonetic Association, 2005) . Most of the dictionaries including the electronically-edited versions use this useful worldwide system. The IPA vowel symbols used for this research paper and for the booklet proposed to master these sounds have been revised in 1993.

2. Methodology

2.1. Generalities

Taking into consideration the thesis previously stated, I have decided to apply three different tests to two English classes. The first test includes distribution exercises; the second one covers contrastive exercises and the third one is about listening exercises. These three sections will also be the subcategories that will constitute the second publication: “Let’s Master the English Vowel Sounds in Ten Lessons.” The total of 58 students tested had already been instructed with one-class introductory lesson about the English vowel system two weeks before. The overview lesson was a PowerPoint presentation designed to introduce to the students the English vowel sounds. The visual presentation did not focus on any specific sound and did not cover any practical exercise either, except for the completion of the blank vowel chart. The statistical results of the three tests administered to the two classes were analyzed, and their ultimate practical objective is to help design the booklet proposed for International University of Ecuador students or any other university to learn the General American English vowel system.

2.2. Targeted Students

The best students to carry on this research are beginners because they still do not have a deep conscience of English phonology (Ladefoged & Maddieson, 1996) , even though they have gone through the common vowel sounds briefly throughout the high school learning experience. Therefore, the two selected classes were two different “English I” classes divided according to UIDE placement test scores, class “Lucy 1” and class “Emma 2.” Class “Lucy 1” has 26 students and a test average of 46.79 ranging from 27 to 63. This class was divided in two groups A and B of 8 and 18 students respectively: group “A” (test average score of 48.12 ranging from 33 to 60) and group “B” (test average score of 45.47 ranging from 27 to 63). Class “Emma 2” has 32 students and a test average of 73.18 ranging from 35 to 96. This class was also divided in two groups A and B of 12 and 20 students respectively: group “A” (test average score of 73.91 ranging from 35 to 96) and group “B” (test average score of 72.45 ranging from 52 to 88). The two classes divided by groups were given the same tests; this will allow me to verify if the two classes and groups will be statistically different or not, once the data results will be analyzed.

2.3. Test Application Criteria

The same tests were given to both classes to see the performance results of two different “English I” classes. Groups “A” were administered the Distribution-exercise test sheets, and groups “B” were given the Contrastive-exercise test sheets. Groups “A” and “B” were given the same Listening-exercise test sheets. Groups “A” were exposed to a series of exercises dealing with the phonological distribution of the most common English sounds, so that the students work on where these sounds more likely would occur, while groups “B” were exposed to a series of contrastive exercises so that the students work on the difference between those sounds. The listening exercises were given to all groups and classes to measure their final performance and reaction of those who were previously given distribution exercises and those who were previously given contrastive exercises. The student final Listening-exercise test performance has two main conditionings: the class number based on the placement test score and the previous kind of test administered based on Distribution or Contrastive exercises.

2.4. Hypotheses

・ Even though classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2” are two beginner “English I” classes, they have a different English level based on their placement test average scores 46.79 and 73.18 respectively. This fact means they may perform differently in the three exercises: Distribution, Contrastive and, most important of all, the final Listening test; thus the reason for dividing the two classes into groups: “A” and “B.” The two groups were given different kind of tests―Distribution and Contrastive, respectively―while at the end both groups were given the Listening exercises.

・ On the Listening test, groups “A” who were previously given the distribution test would probably perform differently or worse than groups “B” who were previously given the contrastive test. Linking the common sound spelling with its pronunciation is very helpful but not enough to establish a difference with its counterpart sound.

・ On the Listening test, groups “B” who were previously given the contrastive test would probably perform differently or better than groups “A” who were previously given the distribution test. Using minimal pairs to teach vowel pronunciation is much more helpful if supported by appropriate and extensive contrast exercises (Carr, 1999) to help students model their articulators so that they master the subtle differences among the vowel sounds.

・ The students’ exposure to distribution exercises may not be enough to understand the production and therefore the utterance of vowel sounds. On the contrary, the students’ exposure to contrastive exercises may help understand the production and therefore the utterance of vowel sounds.

・ The students who are exposed to distribution as well as contrastive exercises may perform the best to understand the production and therefore the utterance of vowel sounds.

2.5. Test Application Process

Each class was divided in two groups and given 15 minutes for both tests: group “A” (distribution) and group “B” (contrastive) at the same time. The students were given the guidelines to complete the test sheet with their own choices and answers. They were also suggested to leave blank any answer they do not know. After that the two kinds of test sheets were distributed. Later, the same students (groups “A” and “B”) were given 15 minutes for the same listening test. The words were read and the students made their choices on the answer sheet. The week later, the listen/read and repeat exercise was done individually and recorded for later analysis.

2.6. Sound Selection Criteria for the Test

For this research work, only two and sometimes three sounds were selected not to overwhelm the students with the numerous vowel sounds of the English language. The selection of any pair of sounds under testing is arbitrary and will not necessarily alter the results. The final research result trend is in the function of the three kinds of exercises (distribution, contrastive and listening/repeating) and not only on the pair of sounds selected. The two sounds selected for the distribution, contrastive and listening exercises are /i:/ and /I/ as a minimal pair and in just one last exercise /i:/, /I/ and /e/ as a minimal triplet. If the results based on these two-sound exercises are in accordance with the assumptions, the research objective will be satisfactory and the remaining nine lessons of “Let’s Master the English Vowel Sounds in Ten Lessons” may be designed.

2.7. The Three Test Sheets

2.7.1. Distribution Exercises

The distribution test sheet has a series of four different exercises. The written introduction is constituted by two short lists of words that show where the two sounds /i:/ and /I/ most likely occur. This will help the students make a connection between these two sounds and their common spellings (Roach, 2002) . Look at the Distribution exercise sheet sample below.

Exercise a: thirty words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two columns in alphabetical order; fifteen words contain /i:/ and the other fifteen words contain /I/. The corresponding sound spelling has been highlighted in red. The students are supposed to check the corresponding IPA symbol for each word (30 correct checks).

Exercise b: ten words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been placed in one row in alphabetical order; five words contain /i:/ and the other five words contain /I/. The corresponding sound spelling has been highlighted in red, and a description of each of the two vowels has been included in the row. The students are supposed to place the words into the corresponding category in any order (10 correct words).

Exercise c: eight words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in one column in alphabetical order; four words contain /i:/ and the other four words contain /I/. Each word is followed by two different IPA transcriptions but only one is correct. The students are supposed to circle the correct transcription for each word. Even though the students may find new IPA symbols in the transcriptions, they only need to concentrate on the two symbols under study (8 correct transcriptions).

Exercise d: six words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in one column in alphabetical order. Each word is followed by a number of blank spaces corresponding the number of symbols used to transcribe that word; three words contain /i:/ and the other three words contain /I/. The corresponding sound spelling has not been highlighted because the students are supposed to write the correct transcription for each word (6 correct transcriptions).

1) Distribution Exercise Scoring Method

Exercises a through c are absolute (correct, incorrect or blank) due to their nature of checking, placing and circling, respectively. As opposed, exercise d is relative; if the correct /i:/ or /I/ symbol is included in the transcription―despite of the fact that the rest of the transcription symbols may not be correct―the transcription is valid (accurate, inaccurate or blank) (Hammond, 1999) .

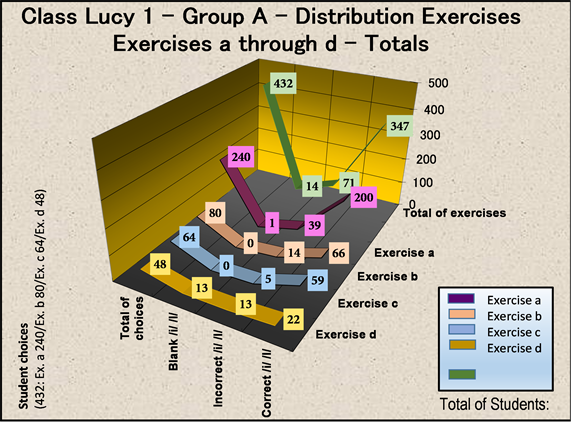

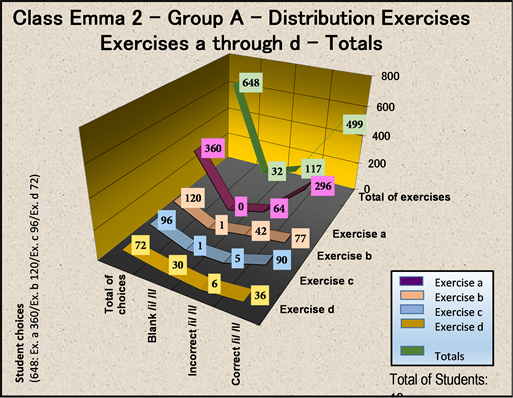

2) Distribution Test Sheet Data Analysis

The four distribution exercises a through d have been digitalized with Excel as shown below, e.g. Exercise a. The electronic sheet shows the subtotals and totals of correct, incorrect and blank checks holistically; furthermore, the subtotals and totals of correct, incorrect and blank checks classified by not only the student number, but also by the word number and sound type /i:/ and /I/ are also shown. So, every exercise reflects a lot of important numeric information capable of analyzing the students’ choices statistically (look at Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1. DT class “Lucy 1”-Group “A” exercise results.

Table 2. DT class “Emma 2”-Group “A” exercise results.

2.7.2. Contrastive Exercises

The contrastive test sheet has a series of six different exercises. The written introduction is constituted by two short lists of words that show where the two sounds /i:/ and /I/ most likely occur. This will help the students make a connection between the sound and its common spellings (Pike, 1943) , whenever applicable, just like the distribution test sheet. Look at the Contrastive exercise sheet sample below.

Exercise e: twenty words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been distributed in two corresponding columns as 10 minimal pairs in random order; ten words contain /i:/ and the other ten words contain /I/. The students are supposed to match the words in the first column with the words in the second column to form minimal pairs (10 correct matches).

Exercise f: four sentences containing /i:/ and /I/ words have been listed without any specific order in four lines; two sentences contain an /i:/ word and the other two sentences contain an /I/ word. The sentences are followed by four minimal pairs transcribing the /i:/ words and the /I/ words contained in the sentences. The students are supposed to read the sentences and circle the correct word transcription (4 correct transcriptions).

Exercise g: four blank sentence spaces have been listed in four lines. The students are supposed to write four sentences containing four words that have not been circled in the previous exercise. The students should be creative to write sentences with the counterpart words of the minimal pairs in exercise f that have not been selected (4 correct sentences).

Exercise h: six words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two columns in alphabetical order; three words contain /i:/ and the other 3 words contain /I/ as three minimal pairs. Each word is followed by a blank space. Obviously, the corresponding sound spelling has not been highlighted because the students are supposed to write the correct transcription for each word (6 correct transcriptions).

Exercise i: six word transcriptions containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two columns in random order; three transcriptions contain /i:/ and the other three transcriptions contain /I/ as three minimal pairs. Each transcription is followed by a blank space. The students are supposed to write the correct spelling for each of the words transcribed (6 correct word spellings).

Exercise j: two sentences containing several /i:/ and /I/ words have been listed in two lines as two tongue twisters. Each sentence has the /i:/ and /I/ words highlighted in red. The first sentence contains four /i:/ words and five /I/ words; the second one contains four /i:/ words and two /I/ words. The students are supposed to read the sentences aloud (15 correct word readings).

1) Contrastive exercise scoring method

Exercises e, f and j are absolute (correct, incorrect or blank/no response) due to their nature of matching, circling and reading aloud, respectively. As opposed, exercises g, h and i are relative. In exercise g, if the correct /i:/ or /I/ word is chosen to write a sentence―even if the rest of the sentences is not coherent―the sentence is valid. In exercise h, if the correct /i:/ or /I/ symbol is included in the word transcription―despite the fact that the rest of the transcription symbols may not be correct―the transcription is considered valid. In exercise i, if the /i:/ or /I/ symbol is spelled correctly―even though each transcribed word may have more than one correct spelling―the word spelled is considered valid as long as the word exists (correct, incorrect or blank/accurate, inaccurate or blank).

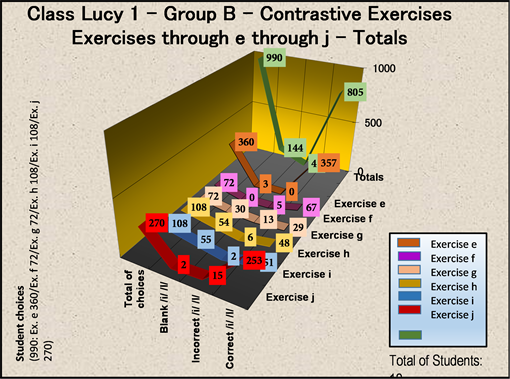

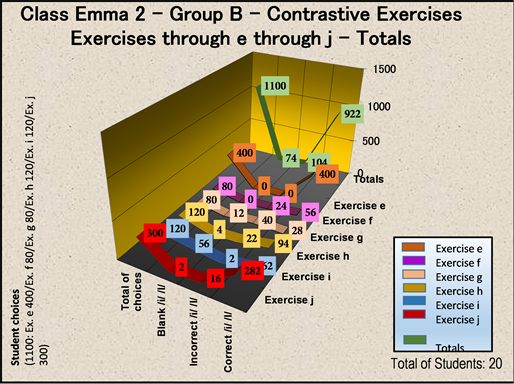

2) Contrastive test sheet data analysis

The six contrastive exercises e through j have been digitalized with Excel as shown below, e.g. Exercise e. The electronic sheet shows the subtotals and totals of correct, incorrect and blank matches holistically; furthermore, the subtotals and totals of correct, incorrect and blank matches classified by not only the student number, but also by the match number and sound type /i:/ and /I/ are also shown. So, every exercise reflects a lot of important numeric information capable of analyzing the students’ choices statistically (look at Table 3 and Table 4).

2.7.3. Listening Exercises

The listening test sheet has a series of six different exercises with no written introduction as opposed to the distribution and contrastive test sheets. This third test is the ultimate one that will be used to measure the students’ performance when they have been previously exposed to either distribution or contrastive exercises (Hall, 2001) . Look at the Listening exercise sheet sample below.

Exercise k: six words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two corresponding columns in alphabetical order; three words contain /i:/ and the other three words contain /I/. The corresponding sound spelling has been underlined to help the students focus on the correct pronunciation. The students are supposed to listen and repeat the words aloud (6 correct repetitions).

Exercise l: twelve words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in four lines distributed in four sets of three words in random order; six words contain /i:/ and the other six words contain /I/. Each set of words contains either the /i:/ sound or the /I/ sound. The corresponding sound spelling has been underlined to help the students focus on the correct pronunciation. The students are supposed to listen to each set of words and choose the correct phonemic symbol for them (4 correct choices).

Exercise m: eight words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two columns in random order as four sets of two words; six words contain /i:/ and the other two words contain /I/. Each set of words either share the /i:/ or do not share it at all. The corresponding sound spelling has been underlined to help the students focus on the correct pronunciation. The students are supposed to listen to the pairs of words and decide whether they share the same vowel sound or not (4 correct choices).

Table 3. CT class “Lucy 1”-Group “B” exercise results.

Table 4. CT class “Emma 2”-Group “B” exercise results.

Exercise n: eight words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two columns as four sets of two words, either minimal pairs or not, in random order; seven words contain /i:/ and the other remaining word contains /I/. The corresponding sound spelling has been underlined to help the students focus on the correct pronunciation. The students are supposed to listen to each pair of words and decide whether they are a minimal pair or not (4 correct choices).

Exercise o: eight words containing /i:/ and /I/ have been listed in two columns as four minimal pairs in random order; four words contain /i:/ and the other four words contain /I/. Each minimal pair is preceded by two blank spaces. The students are supposed to listen to each minimal pair and write the /i:/ and /I/ sounds in the order that the words were heard. The students should know what a minimal pair is―as lectured in a previous PowerPoint presentation (8 correct choices).

Exercise p: nine words containing /i:/ and /I/ and /e/ have been listed in three lines as three minimal triplets in random order; three words contain /i:/, other three words contain /I/ and the three remaining words contain /e/. The students are supposed to listen to each minimal triplet (Crystal, 2003) and repeat it. Once the students know what a minimal pair is, they do not necessarily need to be explained what a minimal triplet is; they can easily infer it. The inclusion of /e/ in this last listening exercise introduces the students a new sound that they will be studying in detail in the following lesson of “Let’s Master the English Vowel Sounds in Ten Lessons” (9 correct repetitions).

1) Listening exercise scoring method

All of the listening exercises are absolute (correct, incorrect or blank/no response) due to their nature of listening and repeating, choosing, deciding and writing; that is, there is one and only one possible choice.

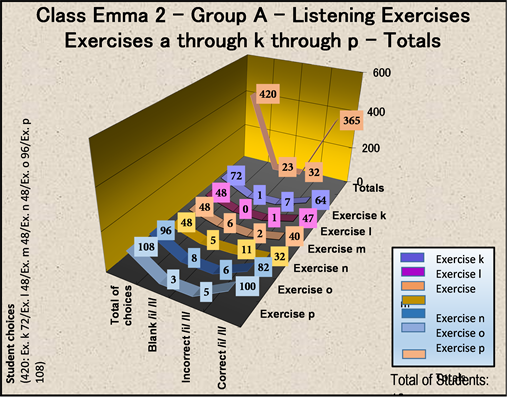

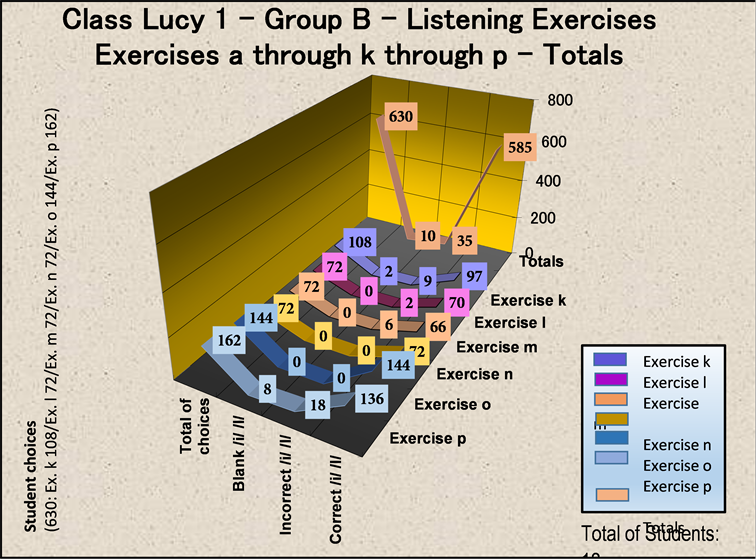

2) Listening test sheet data analysis

The six Listening exercises k through p of groups “A” and “B” have been digitalized with Excel as shown below, e.g. Group A: exercise k and Group B: exercise k. The electronic sheet shows the subtotals and totals of correct, incorrect and blank repetitions holistically; furthermore, the subtotals and totals of correct, incorrect and blank repetitions classified by not only the student number, but also by the word number and sound type /i:/ and /I/ are also shown. So, every exercise reflects a lot of important numeric information capable of analyzing the students’ choices statistically. Like an exit poll, the comparison between Group A: Distribution exercise a with Group A: Listening exercise k and between Group B: Contrastive exercise e with Group B: Listening exercise k will already show the first research results as preliminary scientific support for the thesis previously stated (look at Tables 5-8).

Table 5. LT class “Lucy 1”-Group “A” exercise results.

Table 6. LT class “Emma 2”-Group “A” exercise results.

Table 7. LT class “Lucy 1”-Group “B” exercise results.

Table 8. LT class “Emma 2”-Group “B” exercise results.

3. Results

The Three-Test All-Exercise Numeric Results

1) Distribution tests

Class “Lucy 1”-Group “A” and Class “Emma 2”-Group “A”.

2) Contrastive tests

Class “Lucy 1”-Group “B” and Class “Emma 2”-Group “B”.

3) Listening tests

Class “Lucy 1”-Group “A” and Class “Emma 2”-Group “A”.

Class “Lucy 1”-Group “B” and Class “Emma 2”-Group “B”.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Three-Test All-Exercise Results in Numbers

1) Distribution tests Listening tests

DT: Class “Lucy 1”-Group “A” Vs LT: Class “Lucy 1”-Group “A”.

DT: Class “Emma 2”-Group “A” Vs LT: Class “Emma 2”-Group “A”.

2) Contrastive tests Listening tests

CT: Class “Lucy 1”-Group “B” Vs LT: Class “Lucy 1”-Group “B”.

CT: Class “Emma 2”-Group “B” Vs LT: Class “Emma 2”-Group “B”.

4.2. The Three-Test All-Exercise Result Comparison

1) Class “Lucy 1” DT-Group “A” Vs Class “Lucy 1” LT-Group “A”

Between the distribution exercises and the listening exercise of Class “Lucy 1” group “A” there is no significant difference of correct answers, only 1% (DT: 80.3% and LT: 79.3%). Regarding the incorrect answers, there is a difference of 2.9% (DT: 16.4% and LT 16.4%). Finally there is a difference of 3% regarding the blank answers (DT: 3.2% and LT: 6.1%). This means that the students, who were exposed to distribution exercises prior the listening test, did not have significant improvement in the last test. Let us keep in mind that class “Lucy 1”has a lower placement test score average (look at Graph 1 and Graph 2).

2) Class “Emma 2” DT-Group “A” Vs Class “Emma 2” LT-Group “A”

Between the distribution exercises and the listening exercise of Class “Emma 2” group “A” there is already significant difference of correct answers, 10.5% (DT: 77% and LT: 86.9%). Regarding the incorrect answers,

Graph 1. DE class “Lucy 1-A” results.

Graph 2. LE Class “Lucy 1-A” results.

there is also a difference of 10.5% (DT: 18.1% and LT: 7.6%). Finally there is a difference of 0.6% regarding the blank answers (DT: 4.9% and LT: 5.5%). This means that the students, who were exposed to distribution exercises prior the listening test, did not necessarily have significant improvement in the last test due to this exposure, but because this is a higher class with higher placement test scores (look at Graph 3 and Graph 4).

3) Class “Lucy 1” CT-Group “B” Vs Class “Lucy 1” LT-Group “B”

Between the distribution exercises and the listening exercise of Class “Lucy 1” group “B” there is significant difference of correct answers, 11.6% (DT: 81.3% and LT: 92.9%). Regarding the incorrect answers, there is a difference of 1.5% (DT: 4.1% and LT 5.6%). Finally there is a difference of 12.9% regarding the blank answers (DT: 14.5% and LT: 1.6%). This means that the students, who were exposed to contrastive exercises prior the listening test, did have significant improvement in the last test due to this exposure. Let us keep in mind that class “Lucy 1”has a lower placement test score average, but still had significant improvement (look at Graph 5 and Graph 6).

4) Class “Emma 2” CT-Group “B” Vs Class “Emma 2” LT-Group “B”

Between the distribution exercises and the listening exercise of Class “Emma 2” group “B” there is also

Graph 3. DE class “Emma 2-A” results.

Graph 4. LE class “Emma 2-A” results.

Graph 5. CE class “Lucy 1-B” results.

Graph 6. LE class “Lucy 1-B” results.

significant difference of correct answers, 12.8% (DT: 83.8% and LT: 96.6%). Regarding the incorrect answers, there is also a difference of 6.9% (DT: 9.5% and LT 2.6%). Finally there is a difference of 5.8% regarding the blank answers (DT: 6.7% and LT: 0.9%). This means that the students, who were exposed to distribution exercises prior the listening test, did in fact have significant improvement in the last test due to this exposure (look at Graph 7 and Graph 8).

5) Groups “A” and “B” of classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2” Vs Groups “B” and “B” of classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2”

There is no significant improvement between groups “A” DT and LT of both classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2”, but there is a remarkable improvement between groups “B” DT and LT of both classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2.” This proves that no matter the class level (“Lucy 1” lower or “Emma 2” higher), there is performance improvement in the listening tests of those students who were previously exposed to contrastive exercises. Notice the number of correct, incorrect and blank answers of the two LT bars in the chart below [Classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2” Groups “A” LT (CA: 587/ IA: 73/ BA: 40) and Classes “Lucy 1” and “Emma 2” Groups “B” LT (CA: 1261/ IA: 53/ BA: 16)].

4.3. Conclusion and Recommendations

1) Distribution exercises vs Contrastive exercises

Both distribution exercises and more important of the two contrastive exercises should be included when teaching to master the English vowel system, regardless the class level. Distribution exercises are incomplete when used by themselves to teach English pronunciation. All distribution exercises should be supported by contrastive exercises. The students’ performance is higher when given the chance to establish a comparison between similar sounding sounds like minimal pairs. The numbers in the chart below demonstrate the important improvement in the LT between the students who were previously exposed to DT and those previously exposed to CT. Compare the first two bars named Classes Lucy 1 and Emma 2-Groups A-DT (CA: 846/ IA: 188/ BA: 46) and Classes Lucy 1 and Emma 2-Groups B-CT (CA: 1727/ IA: 145/ BA: 218) and then the last two bars Classes Lucy 1 and Emma 2-Groups A-LT (CA: 587/ IA: 73/ BA: 40) and Classes Lucy 1 and Emma 2-Groups B-LT (CA: 1261/ IA: 53/ BA: 16) (look at Graph 9). Both distribution exercise and contrastive exercises will be

Graph 7. CE Class “Emma 2-B” results.

Graph 8. LE class “Emma 2-B” results.

Graph 9. DE-CE-LE classes “Lucy 1-A/B and Emma 2-A/B” results.

included in the second part of this publication, the practical textbook to master the English vowel sounds: “Let’s Master the English Vowel Sounds in Ten Lessons.”

Cite this paper

NexhmijeAjeti,TeutaPustina-Krasniqi,TringaKelmendi,ArbenMurtezani,VioletaVula,TeutaBicaj,JorgeRomero, (2016) Speech Assessment for UIDE EFL Students: The IPA Case

—General-American English IPA Transcription to Assess Universidad Internacional del Ecuador EFL Students. Open Journal of Modern Linguistics,06,43-59. doi: 10.4236/ojml.2016.62005

References

- 1. Sheets, C.G., Paquette, J.M. and Wright, R.S. (2002) Tooth Whitening Modalities for Pulpless and Discoloured Teeth. In: Cohen, S. and Burns, R.C., Eds., Pathways of the Pulp, 8th Edition, Mosby, London, 755.

- 2. van der Burgt, T.P. and Plasschaert, A.J. (1985) Tooth Discolouration Induced by Dental Materials. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 60, 666-669.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(85)90373-1 - 3. Zareba, T., Bojar, W. and Wasaw, P.L. (2004) Antimicrobial Activity of Root Canal Sealers—In Vitro Evaluation. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 10, 55-59.

- 4. Pumarola, J., Berastegui, E., Brau, E., Cunalda, C. and Jimenez de Ante, M.T. (1992) Antimicrobial Activity of Seven Root canal Sealers. Results of Agar Diffusion and Agar Dilution Tests. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 72, 216-220.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(92)90386-5 - 5. Orstavik, D.A. (1981) Antibacterial Properties of Root Canal Sealers, Cements and Pastes. International Endodontic Journal, 14, 125-133.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.1981.tb01073.x - 6. Kaplan, A.E., Picca, M., Gonzalez, M., Macchi, P.L. and Molgatini, S.L. (1999) Antimicrobial Effect of Six Endodontic Sealers: An in Vitro Evaluation. Endodontics & Dental Traumatology, 15, 42-45.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-9657.1999.tb00748.x - 7. Davis, M.C., Walton, R.E. and Rivera, E.M. (2002) Sealer Distribution in Coronal Dentin. Journal of Endodontics, 28, 464-466.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004770-200206000-00012 - 8. Tina, P.A., Cemal, A., Burgt, A., Eronat, J.M. and Plasschaert, J.M.A. (1996) Staining Patterns in Teeth Discolored by Endodontic Sealers. Journal of Endodontics, 12, 187-191.

- 9. Walsh, L.J. and Athanassiadis, B. (2007) Endodontic Aesthetic Iatrodontics. Australian Dental Practice, 18, 16-24.

- 10. Elkhazin, M. (2011) Analysis of Coronal Discoloration from Common Obturation Materials. An in Vitro Spectrophotometry Study. Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbruecken.

- 11. Lenherr, P., Allgayer, N., Weiger, R., Filippi, A., Attin, T. and Krasti, G. (2012) Tooth Discoloration Induced by Endodontic Materials: A Laboratory Study. International Endodontic Journal, 45, 942-949.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2012.02053.x - 12. Kim, S.T., Abbott, P.V. and McGinley, P. (2000) The Effects of Ledermix Paste on Discolouration of Mature Teeth. International Endodontic Journal, 33, 227-232.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2591.2000.00278.x - 13. White, R.R., Goldman, M. and Lin, P.S. (1987) The Influence of the Smeared Layer upon Dentinal Tubule Penetration by Endodontic Filling Materials. Part II. Journal of Endodontics, 13, 369-374.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-2399(87)80195-4 - 14. Meincke, D.K., Prado, M., Gomes, B.P., Bona, A.D. and Sousa, E.L. (2013) Effect of Endodontic Sealers on Tooth Color. Journal of Dentistry, 41, 93-96.

- 15. Zare Jahromi, M., Navabi, A.A. and Ekhtiari, M. (2011) Comparing Coronal Discoloration between AH26 and ZOE Sealers. Iranian Endodontic Journal, 6, 146-149.

- 16. El Sayed, M.A.A. and Etemadi, H. (2013) Coronal Discoloration Effect of Three Endodontic Sealers: An in Vitro Spectrophotometric Analysis. Journal of Conservative Dentistry, 16, 347-351.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0972-0707.114369 - 17. van der Burgt, T.P., Mullaney, T.P. and Plasschaert, A.J. (1986) Tooth Discoloration Induced by Endodontic Sealers. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 61, 84-89.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0030-4220(86)90208-2 - 18. van der Burgt, T.P., Eronat, C. and Plasschaert, A.J. (1986) Staining Patterns in Teeth Discolored by Endodontic Sealers. Journal of Endodontics, 12, 187-191.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0099-2399(86)80152-2 - 19. Saunders, E.M. and Saunders, W.P. (1995) Long-Term Coronal Leakage of JS Quickfill Root Fillings with Sealapex and Apexit Sealers. Dental Traumatology, 11, 181-185.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-9657.1995.tb00484.x - 20. McMichen, F.R., Pearson, G., Rahbaran, S. and Gulabivala, K. (2003) A Comparative Study of Selected Physical Properties of Five Root-Canal Sealers. International Endodontic Journal, 36, 629-635.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00701.x - 21. Paravina, R.D. and Powers, J.M. (2004) Esthetic Color Training in Dentistry. Elsevier Mosby, Amsterdam.

- 22. Brewer, J.D., Wee, A. and Seyhi, R. (2004) Advances in Color Matching. Dental Clinics of North America, 48, 341-358.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cden.2004.01.004 - 23. Burgt, G. (1993) Clinical Evaluation of an Experimental Body and Incisal Shade Guide Based on in Vivo Tooth Colour Measurements. MS Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

- 24. (2004) Operating Manual: Vita Easyshade.

- 25. Pittford, T.R. (1986) Apexification and Apexogenesis. In: Walton, R.E. and Torabinejad, M., Eds., Principles and Practice of Endodontics, WB Saunders, Philadelphia.

- 26. Walton, R.E. and Rotstein, I. (1996) Bleaching Discolored Teeth: Internal and External. In: Walton, R.E. and Torabinejad, M., Eds., Principles and Practice of Endodontics, 2nd Edition, WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 385.

- 27. Parsons, J.R., Walton, R.E. and Ricks-Williamson, L. (2001) In Vitro Longitudinal Assessment of Coronal Discoloration from Endodontic Sealers. Journal of Endodontics, 27, 699-702.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004770-200111000-00012 - 28. Chiappinelli, J.A. and Walton, R.E. (1992) Tooth Discoloration Resulting from Long-Term Tetracycline Therapy: A Case Report. Quintessence International, 23, 539-541.

- 29. Weinberg, J.E., Rabinowitz, R.L., Zainger, M. and Gennaro, A.F. (1972) 14C-Eugenol: 1. Synthesis, Polymerization, and Use. Journal of Dental Research, 51, 1055-1061.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/00220345720510041101 - 30. Burquest, D. A. (2006). Phonological Analysis: A Functional Approach (3rd ed., p. 319). Dallas: SIL International.

- 31. Carr, P. (1999). English Phonetics and Phonology: An Introduction (pp. 232-245). USA: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

- 32. Crystal, D. (2003). A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (5th ed., pp. 536-539). New York: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

- 33. Hall, T. A. (2001). Distinctive Feature Theory (pp. 372-377). New York: Walter De Gruyter Inc.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/9783110886672 - 34. Hammond, M. (1999). The Phonology of English. UK: Oxford University Press.

- 35. International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet (p. 214). UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 36. International Phonetic Association (2005). The International Phonetic Alphabet. Symbols for All Languages Are Shown on This One-Page Chart.

- 37. Ladefoged, P. (2000). Vowels and Consonants: An Introduction to the Sounds of Languages (p. 191). USA: Blackwell Publishers.

- 38. Ladefoged, P., & Maddieson, I. (1996). The Sounds of the World’s Languages (p. 448). USA: Blackwell Publishing Limited.

- 39. Lindau, M. (1975). Vowel Features (p. 155). Working Papers in Phonetics, Los Angeles: University of California.

- 40. Pike, K. L. (1943). Phonetics: A Critical Analysis of Phonetic Theory and a Technique for the Practical Description of Sounds (p. 192). Michigan: University of Michigan Publications.

- 41. Roach, P. (2001). English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course. (3rd ed., p. 298). UK: Cambridge University Press.

- 42. Roach, P. (2002). A Little Encyclopedia of Phonetics (pp. 93-98). UK: University of Reading.

http://www.personal.rdg.ac.uk/~llsroach/encyc.pdf

Appendixes

Distribution Exercise Sheet Sample

For explanatory purposes, the correct answers have been included in the test sheet in bold font.

・ /i/2 as in the words peak, seek, grief, the (before vowel sounds), perceive

・ /I/ as in the words pick, lick, rhythm, building, businessman

Distribution Exercises

Exercise a: Check Ö the corresponding IPA symbol for each highlighted letter of the following words.

Exercise b: Place the words from the list below into the corresponding category by rewriting them.

Exercise c: Circle the correct transcription of each of the following words.

1. deceive [dIǀsi:v] [dIǀsIv]

2. heat [hi:th] [hIth]

3. hit [hi:th] [hIth]

4. it [i:th] [Ith]

5. relief [rIǀli:f] [rIǀlIf]

6. see [si:] [sI]

7. which [whi:tʃ] [whItʃ]

8. naked [ǀneIki:d] [ǀneIkId]

Exercise d: Transcribe the following words. Count the number of spaces /i/ in narrow transcription is [i:] and counts for two spaces)

1. deer [----] [di:r]

2. garbage [-------] [ǀgarbIdƷ]

3. lip [---] [lip]

4. mean [----] [mi:n]

5. polyethylene [-----------] [ǀpaliǀeθ[li:n]

6. voted [------] [ǀvowtId]

Contrastive Exercise Sheet Sample

For explanatory purposes, the correct answers have been included in the test sheet in bold font.

・ /i/2 as in the words peak, seek, grief, the (before vowel sounds), perceive

・ /I/ as in the words pick, lick, rhythm, building, businessman

Minimal Pairs

Exercise e: Match the words in column /i/ with the words in column /I/ with a line to identify all minimal pairs.

/i/ /I/

Exercise f: Circle the correct pronunciation.

1. New Zealand is the only country in the world with more sheep than people. [ʃi:p] [ʃIp]

2. The doctor’s main concern was to heal the sick man. [hi:l] [hIl]

3. Some people have serious problems trying to swallow big pills. [phi:lz] [phIlz]

4. The wife called the plumber to check all the pipework because water kept leaking. [ǀli:kIN] [ǀlIkIN]

Exercise g: Write 4 sentences with the four words above that have not been circled.

1. ___________________________________________________________________________________

2. ___________________________________________________________________________________

3. ___________________________________________________________________________________

4. ___________________________________________________________________________________

Exercise h: Transcribe the following minimal pairs using the I.P.A.

1. feeling [………………] [ǀfi:lIN] filling [………………] [ǀfIlIN]

2. mix [………………] [mIks] Meeks [………………] [mi:ks]

3. rill [………………] [rIl] real [………………] [ri:l]

Exercise i: Write the correct spelling of the words transcribed below.

1. [kwi:n] ________________ queen [kwIn] ________________ quin

2. [sIlz] ________________ sills [si:lz] ________________ seals

3. [fi:ld] ________________ fealed [fIld] ________________ filled

Exercise j: Read aloud the phrases below.

・ Hesits on the windowsill to seehispeerspick up the seeds.

・ She likes to eatgrilledeel and drinkbeer.

Listening Exercise Sheet Sample

For explanatory purposes, the correct answers have been included in the test sheet in bold font.

Listening exercises

Single words

Exercise k: Listen and repeat the words below. Pay attention to the underlined vowel sounds.

/i/ or /I/ /i/ or /I/

tease six

three fifty

thirteen tip

Exercise l: Listen and repeat the words below. Choose and write the correct phonemic symbol per each group of words.

1. leaving see please __________ /i/ or /I/

2. captain film business __________ /i/ or /I/

3. rib busy hip __________ /i/ or /I/

4. heap gear dearest __________ /i/ or /I/

Exercise m: Listen to the following pairs of words below. Do the underlined letters share the same vowel sound? If yes check it (Ö), if not cross it (´).

1. season weird (Ö)

2. veel lived (´)

3. seeking weeping (Ö)

4. these swimming (´)

Minimal Pairs

Exercise n: Listen to the following pairs of words below. Are they minimal pairs? If yes check it (Ö), if not cross it (´).

1. flea flee (´)

2. sleep slip (Ö)

3. heal heel (´)

4. beech beach (´)

Exercise o: Listen to the following minimal pairs below. Write the corresponding phonemic symbols in the order you hear them.

1. _____ _____ deep /i/ dip /I/

2. _____ _____ Zeep /i/ zip /I/

3. _____ _____ steer /i/ stir /I/

4. _____ _____ bit /I/ beet /i/

Minimal Triplets

Exercise p: Listen and repeat.

/i/ /I/ /e/3

mean min main

leak lick lake

feet fit fate

NOTES

1Distribution drills refer to the exercises that include phonemes that can be found in any non-specific environment within the phonological string and/or exercises that establish a relationship between different phonological elements within words without contrasting them but only describing them in the order they occur. On the other hand, contrastive drills refer to the exercises that describe the relationship between two different phonological elements, where both elements are found in the same specific environment with a change in meaning. An example of this in English would be [i:] and [I], as can be seen in the words heat and hit respectively.

2i/i(:) The narrow transcription [i:] as /i/ in broad transcription is due to /i/’s actual realization as [i:], especially in closed syllables―syllable with coda of the form e.g. VC, CVC, CVCC, CVVC, etc. The extended vocalic duration [:] is predictable by phonological rule and by its preceding phoneme [i] features: close front unrounded vowel. Other transcriptions use the I.P.A.’s semivowel or glide [j] to represent vocalic duration e.g. [ij]. Other transcriptions use no suprasegmental at all after [i] (Lindau, Mona, 1975). The english phonemic feature of tenseness also helps describe the characteristics of this sound. As in the words beat and bit, it is clear that the former sound realization is not only longer but also tense [i:] as opposed to the latter that is shorter and lax /I/. For the purpose of these exercises, I will use the I.P.A.’s close front unrounded vowel [i] (a lower-case letter i) and the suprasegmental [:] (a colon-like symbol).

3e(I)/eI The narrow transcription [eI] as /e/ in broad transcription is due to /e/’s actual realization as [eI], especially in open syllables―coda-less syllable of the form e.g. V, CV, CCV, etc. The off-glide [I] is predictable by phonological rule. Other transcriptions use the I.P.A.’s semivowel or glide [j] to represent the second and less prominent sound of the closing diphthong e.g. [ej], when it should only represent the first sound of the opening diphthong e.g. [je], according to the I.P.A.. Other transcriptions still use [y] to represent the second sound of [eI] e.g. [ey], but it may be confused with the I.P.A.’s /y/, which actually represents the close front rounded vowel in French (Ladefoged, 2000) . For the purpose of these exercises, I will attach to the latest I.P.A.’s near-close near-front unrounded vowel [I] (a small capital letter i) to represent the second sound of the closing diphthong e.g. [eI].