Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.5, 399-405 Published Online May 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.35056 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 399 Personality and College Major Choice: Which Come First? Michela Balsamo1, Marco Lauriola2*, Aristide Saggino1 1Università degli Studi “G. d’Annunzio” Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy 2Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, Roma, Italy Email: *marco.lauriola@uniroma1.it Received February 6th, 2012; revised March 8th, 2012; accepted April 9th, 2012 The present study attempts to solve the nature of the known individual differences in personality related to academic college major choice. The question whether these precede or follow the choice of an academic major is still open. To rule out environmental influences during academic study, group differences in personality were assessed in perspective college students, thus before the incoming in a specific academic major. The Big Five Questionnaire-60 (BFQ; Caprara, Schwartz, Capanna, Vecchione, & Barbaranelli, 2006) and a questionnaire assessing the behavioural intention to enrol in different university faculties were administered to a sample of 886 last-year students who enrolled in different senior high schools. Among the Big-Five Factors, Extraversion and Conscientiousness have been found the explanatory vari- ables predicting high-school students’ expressed choice for their perspective academic career. These find- ings give a preliminary empirical support to the hypothesis of the pre-existence of group differences in personality at the moment of their choice for a specific academic career. Limitations and implications for future research are discussed. Keywords: Personality Traits; College Major Choice Introduction Deciding whether going to college and which college major to matriculate in is one of the most important life decisions and perhaps the first important life decision for students in Western industrialized countries (Galotti, 2007). Also, it represents a decision that research has shown to be the most frequently identified life regret for Americans (Roese & Summerville, 2005). It is indeed important for students to choose a college environment that fits well with their personal characteristics. In fact, according to Holland’s (1985, 1996, 1997) vocational theory, students are expected to flourish as long as there is a good fit between personality and environment characteristics. Not surprisingly, it has been documented that a poor fit is likely to adversely affect student well-being and performance at school, while a good fit can make college years less stressful and can help reducing student attrition, which may eventually turn out in dropping out from college (Tracey & Robbins, 2006; Schmitt, Oswald, Friede, Imus, & Merritt, 2008; Wintre et al., 2008; Allen & Robbins, 2008, 2010; Gilbreath, Kim & Nichols, 2010; Tracey, Allen, & Robbins, 2011). Likewise, personnel psychologists proposed a model by which workers are first attracted by organizations that are seemingly alike to their personality characteristics, then se- lected by these organizations, and eventually drop out from the organization because of an actual misfit between worker per- sonality characteristics and environment requests (Schneider, Goldstein, & Smith, 1995; Slaughter, Stanton, Mohr & Schoel, 2005; De Cooman et al., 2009). Personality research on this topic supported both vocational and personnel psychology claims as it concerns the person- environment fit hypothesis based on evidence collected from college students which already started their academic way. However, while in the current person-environment fit literature it is important to separate “socialization” effects from “selec- tion” effects (Miech, Caspi, Moffitt, Entner-Wright, & Silva, 1999), such personality studies are unable to disentangle these effects as long as they compared the average profile of students sampled from different faculties. Thus, the question whether individual differences in personality precede or follow the choice of an academic major, and eventually predict students’ proficiency in a specific major, is still open. Before presenting data collected from senior high-school students during the period they make their decisions about fu- ture college major choice, we review personality literature to trace the personality profile of different college majors onto which comparing the personality profile of groups of perspec- tive college students, which are not yet exposed to the “sociali- zation” effects of any college environment. Personalit y T r ai ts a n d Uni versity Major It has been documented that there are consistent personality differences between groups of students enrolled in different majors (Hu & Gong, 1990; Corulla & Coghill, 1991; Kline & Lapham, 1992; Harris, 1993; Wilson & Jackson, 1994; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Lievens, Coetsier, De Fruyt, & De Maeseneer, 2002; Rubinstein, 2005; Marrs, Barb, & Ruggiero, 2007; Van der Molen, Schmidt, & Kruisman, 2007; Lounsbury, Smith, Levy, Leong, & Gibson, 2009). Most studies of the Big-Five and academic college major choice compared natural-science and applied-science students to other groups. Students enrolled in natural-science majors not only were often described as more introverted than those en- rolled in humanities, social science and art majors (Hu & Gong, 1990; Harris, 1993), but they were also more introverted than applied-science, medical students and mixed control groups *Corresponding author.  M. BALSAMO ET AL. (Corulla & Coghill, 1991; Wilson & Jackson, 1994; Lievens, Coetsier, De Fruyt, & De Maeseneer, 2002). Other traits have been associated with the choice of a natural-science college major. Results show that natural-science students attained higher Emotional Stability scores than humanities, art and law or economics students (Hu & Gong, 1990; Corulla & Coghill, 1991; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Rubinstein, 2005), as well as lower scores on Openness to Experience than humanities, social science, political science, art and mixed control groups (Kline & Lapham, 1992; Harris, 1993; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Marrs, Barb, & Ruggiero, 2007). Students enrolled in applied-science majors resulted as more conscientious than humanities, social science, political science, art and mixed con- trol groups (Kline & Lapham, 1992; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Van der Molen, Schmidt, & Kruisman, 2007), as well as more closed minded than other groups but natural-science ma- jors (Kline & Lapham, 1992; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996). However, applied-science students not only described them- selves as less agreeable and cooperative than natural-science ones (Kline & Lapham, 1992; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996), but also more though-minded than mixed control groups (Van der Molen et al., 2007). Making a summary of these findings, one may presume that the personality profile of natural-science students is mostly characterized by Introversion, while that of applied-science students is mostly characterized by Conscien- tiousness, Closed- and Tough-Mindedness. Most studies which involved humanities students provided consistent results as to their lesser extraverted personality, es- pecially if they were compared to medical, applied-science, natural-science, law or economics and political science students (De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Lievens et al., 2002). However, the issue whether humanities students are more or less extra- verted than natural-science students is still open. Whereas Hu and Gong (1990) concluded that humanities students are more extraverted than natural-science, the opposite conclusion was drawn by De Fruyt and Mervielde (1996). In addition, most studies reported lower Conscientiousness scores for humanities students relative to medical, applied-science, natural-science, law or economics and political science students (De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Lievens et al., 2002), as well as higher neu- roticism scores than applied-science, natural-science, politi- cal-science and mixed control groups (Hu & Gong, 1990; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996). Based on this literature we may conclude that the personality profile of humanities-students may be outlined as characterized by Introversion, Neuroticism and Carelessness relative to other groups. Higher Openness to Experience scores mostly differentiated students enrolled into social-science majors from science ma- jors, both natural and applied (Kline & Lapham, 1992; Harris, 1993; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Marrs, Barb, & Ruggiero, 2007), as well as from Law or Economics, Arts and mixed con- trol groups (Harris, 1993; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Rubin- stein, 2005; Marrs, Barb, & Ruggiero, 2007). As it regards the presumed Extraversion of social-science students, our literature review supported this claim only when social-science students have been compared to humanities and natural-science students, who were the more introverted groups (Harris, 1993; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996). Like humanities students, social-science students were less conscientious than applied-science, natural- science, law or economics and political-science students (Kline & Lapham, 1992; De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996). Business and law students were higher in Extraversion and Conscientiousness than humanities students, as well as more conscientious than social-science majors (De Fruyt & Mer- vielde, 1996). In addition, they were the most though minded group relative to many other groups, such as medical, social- science, natural, arts and mixed control students (De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Lievens et al., 2002; Rubinstein, 2005; Lounsbury, Smith, Levy, Leong, & Gibson, 2009). A few stud- ies have considered art and medical students. Art students mostly differentiated themselves from science students, both natural and applied, as they obtained higher Openness to Ex- perience and Neuroticism scores as well as lower Conscien- tiousness scores (Corulla & Coghill, 1991; Kline & Lapham, 1992; Harris, 1993). Furthermore, art students were described as more agreeable (Kline & Lapham, 1992), but less open to experience than social science-students (Marrs et al., 2007). No positive findings have been reported in the literature as to the difference between art and humanities majors. To our knowl- edge, the only study who compared the Big-Five profile of medical students to that of other groups reported that medical students obtained higher scores on Extraversion and Agree- ableness than seven different academic majors (Lievens et al., 2002). The Present Study Based on major theories of vocational choice as well on the literature that we have reviewed in the above section (see also Lauriola, Saggino, Balsamo, & Gioggi, 2005), the question whether personality factors are associated with attending the choice of an academic major is no longer a issue. Though some inconsistent results, the personality profile of natural-science students is mostly characterized by Introversion, while that of applied-science students is mostly characterized by a mixture of Conscientiousness, Closed- and Tough-Mindedness. Further- more, the personality profile of humanities-students was char- acterized by Introversion, Neuroticism and Carelessness rela- tive to other groups. Social-science students are often described as moderately extraverted but less conscientious than other groups of students. The hypothesis that a specific academic environment may actively attract and select some specific personality types has been traditionally investigated by comparing the profile of dif- ferent groups of students. However, such studies say little about whether group differences in personality preceded one’s aca- demic choice or whether group differences in personality are accounted for by a selective pressure of a specific environment. Despite a complete answer to this question would require ex- tensive controlled longitudinal research over a period of time longer than five years (considering five years as a reasonable expected time to complete college studies), some evidence supporting the pre-existence of individual differences in per- sonality can be provided by survey research assessing senior high-school students. No such study has been carried out yet so far. Thus, the main goal of the present study is comparing the personality profile of senior high-school students at the moment of their choice for a specific academic career. Different from the studies reviewed in the introduction, we look for personality characteristics that are of some importance when high-school students sort themselves into a specific major, not for personal- ity traits that characterized specific college majors. The extent to which the profile of perspective college students is alike to that reported in the literature for groups sampled within specific Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 400  M. BALSAMO ET AL. academic majors can help answering the question whether indi- vidual differences in personality precede or follow the aca- demic choice. Methods Participants A total of 886 students at the last high-school year (495 fe- males and 391 males) aged 17 to 20 years old (M = 18.11; SD = .58) were surveyed from different parts of Italy. Four-hun- dred-seventy-six participants were from the north (53.7%), 136 were from the centre (15.3%), and 274 were from the south (30.9%) of the country. As to the attended school type, the sur- veys were collected from 493 students in college preparing high-schools (128 humanities-oriented, 287 science-oriented and 78 teacher-training) and from 393 students in job preparing high-schools (211 technical-accountants, 96 polytechnic, 86 leisure-and-tourism). All participants were in the last year of the senior high school and were surveyed about two months earlier than they ended the school. As a part of the survey, high-school students were filtered on a preliminary question asking for whether they planned to continue their academic career at college. Those who answered positively to this ques- tion (N = 754, 85.1%) were asked to express their interests for each of 41 academic programs commonly provided by Italian public universities. Finally, students were asked to express their final choice, indicating which college major was their most likely choice for the next year. In order to facilitate the com- parison with the reviewed literature, we grouped the students’ expressed choice as follows: natural-science, applied-science, social-science, health-science, arts & humanities, economic & law, sport-science, military. Students who expressed more than a single preference or left their choice blank, but intended go on with their academic career, were grouped as undecided respon- dents. Procedure All participants were in the last year of the senior high school and were surveyed about two months earlier than they ended the school. This period of the year was chosen because it is close to the deadline for applying to college and most students already have a clear picture of the type of major they are will- ing to matriculate in. The survey was administered during the regular class hours, after that participants provided their in- formed consent. During the completion time the class teacher was waiting out of the room, to prevent from potential external influences. The interviewer was in class and observed and wrote down on a diary any unusual class behavior, which could have been interfere with the survey completion. The survey completion time was on average 30 minutes. As a part of the survey, high-school students were filtered on a preliminary question asking for whether they planned to continue their aca- demic career at college. Instruments The survey included: 1) questions assessing the behavioural intention to enroll in different university faculties. It also in- cludes a preliminary question asking for whether students in- tend to continue their academic career at a college for the next year and, in case of positive answer, which college major would been their most likely choice. 2) The Big Five Questionnaire-60 (BFQ-60; Caprara, Schwartz, Capanna, Vecchione, & Barbara- nelli, 2006), which is an abridged form of the extensively used 132-item Big Five Questionnaire (BFQ; (Caprara, Barbaranelli, Borgogni, & Perugini, 1993). It was validated on large national students and community samples (Barbaranelli & Caprara, 2000; Caprara et al., 1993; Caprara, Barbaranelli, & Livi, 1994), as well as in cross-cultural research (Caprara, Barbaranelli, Bermudez, Maslach, & Ruch, 2000). The form used in this study contains 60 items, each asking for “how you are like” a 5-point scale (1 = very false for me, 5 = very true for me). The items were purposefully selected from the original BFQ as the best possible trade-off between ques- tionnaire length and optimal psychometric properties (Caprara et al., 1993). In particular, the reliability indexes assessed in the present study for the five domain scales of Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience met with the psychometric standard for short scales (i.e., .70, .69, .78, .83 and .72 with 12 items each, respectively). Statistical Analysis The Big-Five factors were considered as independent vari- ables in a set of discriminant function analyses aimed at pre- dicting high-school students’ expressed choice for their per- spective academic major. Since one’s academic choice is com- plex and multi-determined, we controlled for gender and school type differences, including these variable in the analysis in a logically ordered way. We first entered personality variables, then we added gender and finally we included school type in the model. The comparison of statistically significant predictors between models helped understanding whether the effect of individual difference variables was spuriously inflated by gen- der and attended high school type, whose effect on major choice has been repeatedly documented (Worthington & Higgs, 2003; Malgwi et al., 2005; Niu & Tienda, 2008; Ma, 2009, 2011; Dickson, 2010). Results Descriptive Analyses of College Major Choice Students were filtered on a preliminary question asking for whether they have planned to continue their academic career at college. Those who answered positively to this question (N = 754, 85.1%) were asked for which college major would have been their choice for the next year. The most preferred choices were: economic-law (N = 216; 28.6%), applied-Science (N = 106; 14.1%), health-science (N = 97; 12.9%) and social-science (N = 87; 11.5%) majors. Other majors were chosen by ap- proximately one fourth of respondents as follows: humanities (N = 57; 7.6%), natural-science (N = 53; 7.0%), art (N = 51; 6.8%), military-college (N = 20; 2.7%) and sport-science (N = 11; 1.5%). Although 56 respondents (6.3%) planned to continue their academic career, they did not decided yet for any specific major. Respondents’ expressed choices were significantly asso- ciated with gender (χ2 = 97.58; df = 9; p < .001). The inspection of standardized residuals revealed that there were significantly more males expressing an applied-science or a sport-science choice, and significantly more females express- ing a social-science choice. Other expressed choices, albeit in some cases were disproportionally chosen by males and fe- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 401  M. BALSAMO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 402 perspective humanities students were indeed the most intro- verted group and the most conscientious than other groups con- sidered in this study. Perspective economic-law students were the most extraverted and one of the less conscientious group. Likewise, perspective military students were the least conscien- tious group and one of the more extraverted. Perspective health science students were almost as conscientious as humanities students, but the two groups differed as it regards the higher extraversion of health science students. males, did not attain statistical significance. As to the effect of attended school type on college major choice, a statistically significant association (χ2 = 52.86; df = 9; p < .001) has been detected with students in job preparing schools who expressed less preferences for health-science and natural-science majors than students in college preparing schools. Furthermore, stu- dents in job preparing schools were also more frequent than students in college preparing schools among those who did not decided yet for any specific major. The effects of both these variables was taken into account when addressing the issue of whether personality traits predicted high-school student choices. Our descriptive analysis of college major choice reavealed an association of this variable with both gender and high-school type. Thus, a logical question to be answered is whether gender and school type were counfounding factors in assessing the relation of Extraversion and Conscientiousness with expressed major choice. To rule out these alternative accounts, a second discriminant function analysis was carried out to evaluate the “unique” contribution of individual differences in personality controlling for the disproportion of males and females in most college major choice groups. Higher priority was given to gen- der, relative to personality factors, in a sequential analysis. Three discriminant functions (λ-s) were extracted (with a com- bined χ2 = 150.32; df = 27; p < .001). After removal of the first function λ1, there still was a statistical association between groups and predictors (χ2 = 43.64; df = 16; p < .001). After removal of the second function λ2, the analysis was no longer significant (χ2 = 7.47; df = 7; p = .38). The two significant dis- criminant functions accounted for 72% and 23% of the between groups variability, whereas the third marginally significant fuction accounted for about 4.7%. Consistent with our sequen- tial strategy, who assigned higher priority to gender, the first discriminant function summarized gender differences in college major choices. The inspection of standardized coefficients re- vealed that the second and the third function in this analysis were mostly loaded by Extraversion and Conscientiousness, thus resembling the first and the second function assessed in the earlier analysis. These results indicated that gender differences in college major choice subtracted from Conscientiousness but not from Extraversion. The pattern of group differences on the second and third discriminant functions resembled the pattern has been described in earlier analysis, as shown in Figure 1. Personality and Expressed College Major Choice A stepwise discriminant function analysis was carried out with Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emo- tional Stability and Openness to Experience as predictors of membership in economic-law, applied-science, health-science, social-science, humanities, natural-science, art, military-college and sport-science expressed college major choices. Three dis- criminant functions (λ-s) were extracted (with a combined χ2 = 62.48; df = 27; p < .001). After removal of the first function λ1, the analysis approached the conventional level of statistical significance (χ2 = 25.05; df = 16; p = .07). After removal of the second function λ2, the analysis was far away from statistical significance. The first and the second discriminant functions accounted for 60% and 28% of the between groups variance. According to Tabachnick and Fidell (2006), the inspection of the rotated loading matrix of correlations between predictors and discriminant functions indicated that the first function was mostly loaded by Extraversion, whereas the second function was mostly loaded by Conscientiousness. As one can see from Figure 1, the groups who were maximally separated on the first discriminant function were students who expressed a humani- ties major choice vs. those who expressed an economic-law major choice. Differently, the groups who were maximally separated on the second discriminant function were students who expressed a humanities major choice vs. those who ex- pressed a military major choice. In keeping with the literature, Figure 1. Group centroids from stepwise discriminant function analysis of the Big Five computed on the expressed college major choices.  M. BALSAMO ET AL. A third discriminant function analysis was carried out to evaluate the “unique” contribution of individual differences in personality controlling also for the disproportion of different school-types indifferent expressed choice groups. Higher prior- ity was indeed given to gender and school type relative to per- sonality factors. Four discriminant functions (λ-s) were ex- tracted (with a combined χ2 = 199.42; df = 36; p < .001). After removal of the first and the second function, there still was a statistical association between groups and predictors (λ1 = .76; χ2 = 87.42; df = 24; p < .001 and λ2 = .89; χ2 = 34.38; df = 14; p < .05). After removal of the third function λ3, the analysis was no longer significant (χ2 = 2.46; df = 6; p = .87). The three sig- nificant discriminant functions accounted for 57%, 26% and 15% of the between groups variability. Like earlier analysis, the first and the second discriminant functions summarized gender differences and attended school type differences in college major choices, while the third discriminant function was loaded by Extraversion. Again, gender differences and school type differences did not subtract from Extraversion. The major findings of discriminant analyses might be sum- marized in the following statements: 1) Extraversion and Con- scientiousness were among the Big-Factors who differentiated expressed college major choices of high school students, par- ticularly separating perspective applied-science majors from other groups of students; 2) controlling for the counfonding effect of gender differences, which were associated with both personality and expressed major choice, the effect of Extraver- sion still was statistically significant, while the effect of Cosci- entiousness only approached statistical significance; 3) control- ling for both gender and attended school type, Extraversion was the only personality factor accounting for expressed college major choices. Discussion Consistent with well established vocational and personnel psychology theories (e.g. Schneider et al., 1995; Holland, 1997), it has been hypothesized that a specific academic environment may actively attract and select some specific kind of perspec- tive college students. Despite a complete answer to this ques- tion would have required extensive controlled longitudinal research over a long period of time, this study has been de- signed to provide some preliminary evidence in support of our hypothesis. It first has been looked at whether reliable person- ality differences can be found among group of students who expressed a deliberate college major choice for the next aca- demic year, and then compared these differences to docu- mented differences between groups of college students who have already been exposed to or socialized to a specific college environment. As it concerns the first issue, preliminary evidence has been found that perspective college students who expressed a delib- erate major choice resulted to have specific personality profiles depending on their stated preferred major. In addition, despite the comparison of college student groups revealed a complex pattern of individual differences in virtually all of the Big Five factors, only individual differences in Extraversion and Con- scientiousness seems to precede the period of college matricu- lation. This finding not only suggests that some personality traits encompassed into the Big Five factor model, preceded to some extent one’s entry period in a specific academic environ- ment, but also that there are some stable personality differences in Extraversion and Conscientiousness, which are not likely to be the effect of a socialization process within a specific social environment. As it concerns the consistency of pre-existent group differ- ences with group differences well documented in the literature, our study showed that lower Extraversion mostly differentiated humanities and science perspective students from economic- law, social science or art ones. In addition, if one looks at the rank order of perspective college student groups along the in- troversion-extraversion continuum (Figure 1), one can see that there is a good degree of consistency with personality studies, which revealed that actual humanities students were often characterized by lower extraversion than other groups (De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996), in some cases even lower than sci- ence students which have been traditionally portrayed as the most introverted group of students (e.g., Hu & Gong, 1990). The greater extraversion reported by perspective economic-law students is another finding consistent with the literature inves- tigating actual groups of college students (De Fruyt & Mer- vielde, 1996; Lounsbury et al., 2009). The second most important personality characteristics, sepa- rating perspective college students, was Conscientiousness. This finding is in keeping with one of the most comprehensive reviews of Big Five in education, which stressed the importance of this personality factor in predicting hard-working in school and college environments (De Raad & Schouwenburg, 1996). Again, perspective humanities and science students reported higher ratings than other groups of perspective students. This finding was consistent with the literature showing that science students, regardless of whether enrolled in a natural or in an applied major, were often portrayed has very careful and accu- rate people (e.g., Kline & Lapham, 1992; De Fruyt & Mer- vielde, 1996). However, in contrast with the reviewed literature, our study revealed that humanities students, although intro- verted were not described as more conscientious than other groups (e.g., De Fruyt & Mervielde, 1996; Lievens et al. 2002). Our findings were not only consistent to a large extent with the literature, but also they were robust to confounding factors which may both affect one’s college major choice as well as one’s personality ratings (Worthington & Higgs, 2003; Malgwi et al., 2005; Niu & Tienda, 2008; Ma, 2009, 2011; Dickson, 2010). For instance, the discriminant function loaded by Extra- version still attained the conventional levels of statistical sig- nificance when gender differences and attended school type were controlled for in the analysis. Differently, the discriminant function representing Conscientiousness in the analysis was no longer statistically significant, after controlling for covariates, and this may perhaps account for some inconsistency between our study of perspective college students and studies of actual college students as it concerns the presumed higher Conscien- tiousness of humanities students. Before concluding, it’s worth acknowledging the following limitations to our findings. First of all, in order to provide an ultimate answer to the question whether personality differences preceded college socialization, an extensive controlled longitu- dinal study is needed. Second, we investigated a behavioral intention to enroll in a specific college major about six months before the actual choice, thus it is possible that part of the stated intentions might be different from the actual behavior. Finally, we controlled for gender and attended high school type in data analysis, while the effect of other possible confounding factors Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 403  M. BALSAMO ET AL. (e.g., student’s parental occupation and socioeconomic status, parental and peer influence, the student’s prior work experience, perceived career prestige and self-employment opportunities, reputation of the major, perceived quality of instruction, and amount and type if promotional information) cannot be ruled out (Leppel, Williams, & Waldauer, 2001; Porter & Umbach, 2006; Ma, 2009, 2011). Taken together, this research provide a preliminary empirical answer to the question whether some individual differences in personality came first than socialization effect of the college social environment shaping actual student personality profiles. In other words, it seems plausible to assume that personality domains had significant impact on the intention to enrol in a specific university faculty (“selection” effects), and not the contrary, that is the choice of a particular cultural-academic context had systematic impact on the individual’s structure of personality traits (“socialization” effects). The results of the present study also underscore the utility of an assessment of individual differences in personality in educa- tional counseling already at the time of senior high school. It is possible that these differences are associated with the outcome in specific academic fields. Therefore, if replicated, the present findings might be helpful from a practical standpoint for school counseling psychologists faced with the issue of college major choice. From a theoretical perspective, these results enhance the current body of knowledge on the psychology of orientation and provide new applications of the Big Five model (Goldberg, 1990; John, 1990) to the study of college student development. Acknowledgements The authors discussed the contents of this article together. Marco Lauriola and Michela Balsamo elaborated the research hypotheses, set the methodological contents collected and ana- lyzed the data. Aristide Saggino provided a significant contri- bution in planning this study as well in the interpretation of results. The final version of the manuscript was written by M. Lauriola and M. Balsamo. REFERENCES Allen, J., & Robbins, S. (2008). Prediction of college major persistence based on vocational interests and first-year academic performance. Research in Higher Education, 49, 62-79. doi:10.1007/s11162-007-9064-5 Allen, J., & Robbins, S. (2010). Effects of interest-major congruence, motivation, and academic performance on timely degree attainment. Journal of Counseling Psyc holo gy, 57, 23-35. doi:10.1037/a0017267 Barbaranelli, C., & Caprara, G. V. (2000). Measuring the Big Five in self-report and other ratings: A multitrait-multimethod study. Euro- pean Journal of Psychological Assessment, 16, 31-43. doi:10.1027//1015-5759.16.1.31 Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., & Perugini, M. (1993). The Big Five questionnaire: A new questionnaire to assess the Five Factor Model. Personality and Individual Differences, 15, 281-288. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(93)90218-R Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., & Livi, S. (1994). Mapping persona- lity dimensions in the Big Five model. European Review of Applied Psychology, 44, 9-15. Caprara, G.V., Schwartz, S., Capanna, C., Vecchione, M., & Barbaranelli, C. (2006). Personality and politics: values, traits, and political choice. Political Psychology, 27, 1-28. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00447.x Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Bermudez, J., Maslach, C., & Ruch, W. (2000). Multivariate methods for the comparison of factor structures in cross-cultural research: An illustration with the Big Five ques- tionnaire. Journal of Cro ss Cu ltu ral Psychology, 31, 437-464. doi:10.1177/0022022100031004002 Corulla, W.J., & Coghill, K.R. (1991). Can educational streming be linked to personality? A possible link between extraversion, psy- choticism and choice of subjects. Personality and Individual Differ- ences, 12, 367-374. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(91)90052-D De Cooman, R., Gieter, S. D., Pepermans, R., Hermans, S., Bois, C. D., Caers, R., & Jegers, M. (2009). Person-organization fit: Testing socialization and attraction-selection-attrition hypotheses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 102-107. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2008.10.010 De Fruyt, F., & Mervielde, I. (1996). Personality and interests as pre- dictors of educational streaming and achievement. European Journal of Personality, 10, 405-425. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0984(199612)10:5<405::AID-PER255>3.0. CO;2-M De Raad, B., & Schouwenburg, H.C. (1996). Personality in learning and education: A review. European Journal of Personality, 10, 303-336. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0984(199612)10:5<303::AID-PER262>3.0. CO;2-2 Dickson, L. (2010). Race and gender differences in college major choice. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627, 108-124. doi:10.1177/0002716209348747 Galotti, K. M. (2007). Decision structuring in important real-life decisions. Psycholog i c a l Science, 18, 320-325. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01898.x Gilbreath, B., Kim, T.-Y., & Nichols, B. (2010). Person-environment fit and its effects on university students: A response surface metho- dology study. Research in Hi gher Education, 52, 47-62. doi:10.1007/s11162-010-9182-3 Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The Big-Five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psy- chology, 59, 1216-1229. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216 Harris, J. A. (1993). Personalities of students in three faculties: Percep- tion and accuracy. Personality and Individual Differences, 15, 351-352. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(93)90229-V Holland, J. L. (1985). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocation personalities and work environments. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Holland, J. L. (1996). Exploring careers with a typology what we have learned and some new directions. American Psychologist, 51, 397- 406. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.4.397 Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of voca- tional personalities and work environments (3rd ed.). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. Hu, C., & Gong, Y. (1990). Personality differences between writers and mathematicians on the EPQ. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 637-638. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(90)90047-U John, O.P. (1990). The “Big Five” factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and questionnaires. In: L. A. Pervin, (Ed.), Handbook of personality theory and research (pp. 66-100). New York: Guilford. Kline, P., & Lapham, S. (1992). Personality and faculty in British uni- versities. Personality and Individual Diffe ren ces, 13, 855-857. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(92)90061-S Lauriola, M., Saggino, A., Balsamo, M., & Gioggi, A. (2005). Tratti di personalità nel contesto educativo: Successo ed orientamento scolastico [Personality traits in education: School achievement and interests]. GIPO- Giornale Italiano di Psicologia dell’Orientamento, 6/1, 13-25. Leppel, K., Williams, M.L., & Waldauer, C. (2001). The impact of parental occupation and socioeconomic status on choice of college major. Journal of Family and Economic, 22, 373-394. Lievens, F., Coetsier, P., De Fruyt, F., & De Maeseneer, J. (2002). Medical students’ personality characteristics and academic perfor- mance: A five-factor model perspective. Medical Education, 36, 1050-1056. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01328.x Lounsbury, J. W., Smith, R. M., Levy, J. J., Leong, F. T., & Gibson, L. W. (2009). Personality characteristics of business majors as defined Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 404  M. BALSAMO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 405 by the Big Five and narrow personality traits. Journal of Education for Business, 84, 200-205. doi:10.3200/JOEB.84.4.200-205 Ma, Y. Y. (2009). Family socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and college major choices-gender, race/ethnic, and nativity patterns. Sociological Persp e c tives, 52, 211-234. doi:10.1525/sop.2009.52.2.211 Ma, Y. Y. (2011). College major choice, occupational structure and demographic patterning by gender, race and nativity. Social Science Journal, 48, 112-129. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2010.05.004 Marrs, H., Barb, M. R., & Ruggiero, J. C. (2007). Self-reported influ- ences on psychology major choice and personality. Individual Dif- ferences Research, 5, 289-299. Miech, R. A., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Wright, B. R., & Silva, P. A. (1999). Low socioeconomic status and mental disorders: A longitu- dinal study of selection and causation during young adulthood. American Journal of Sociology, 104, 1096-1131. doi:10.1086/210137 Niu, S. X., & Tienda, M. (2008). Choosing college: Identifying and modeling choice sets. Social Science Research, 3 7 , 416-433. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.06.015 Porter, S. R., & Umbach, P. D. (2006). College major choice: An analysis of person-environment fit. Research in Higher Education, 47, 429-449. doi:10.1007/s11162-005-9002-3 Roese, N. J., & Summerville, A. (2005). What we regret most … and why. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1273-1285. doi:10.1177/0146167205274693 Rubinstein, G. (2005). The big five among male and female students of different faculties. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 1495-1503. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.012 Schneider, B., Goldstein, H. W., & Smith, D. B. (1995). The ASA framework: An update. Personnel Psychology, 48, 747-774. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1995.tb01780.x Schmitt, N., Oswald, F. L., Friede, A., Imus, A. & Merritt, S. (2008). Perceived fit with an academic environment: Attitudinal and behav- ioral outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72, 317-335. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.007 Slaughter, J. E., Stanton, J. M., Mohr, D. C., & Schoel III, W. A. (2005). The interaction of attraction and selection: Implications for college recruitment and schneider’s ASA model. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54, 419-441. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00218.x Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2006). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers. Tracey, T. J., & Robbins, S. B. (2006). The interest-major congruence and college success relation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Voca- tional Behavior, 69, 64-89. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2005.11.003 Tracey, T. J. C., Allen, J., & Robbins, S. B. (2011). Moderation of the relation between person-environment congruence and academic suc- cess: Environmental constraint, personal flexibility and method. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 8 0, 38-49. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.005 Van Der Molen, H. T., Schmidt, H. G., & Kruisman, G. (2007). Personality characteristics of engineers. European Journal of Engineering Education, 3 2, 495-501. doi:10.1080/03043790701433111 Wilson, G. D., & Jackson, C. (1994). The personality of physicists. Personality and Individual Differences, 16, 187-189. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90123-6 Wintre, M., Knoll, G., Pancer, S., Pratt, M., Poliyy, J., Birnie-Lefco- vitch, S., et al. (2008). The transition to university: The student- university match (SUM) questionnaire. Journal of Adolescent Re- search, 23, 745-769. doi:10.1177/0743558408325972 Worthington, A. C., & Higgs, H. (2003). Factors explaining the choice of a finance major: The role of students’ characteristics, personality and perceptions of the profession. Accounting Education: An International Journal, 1 2, 261-281. doi:10.1080/0963928032000088831

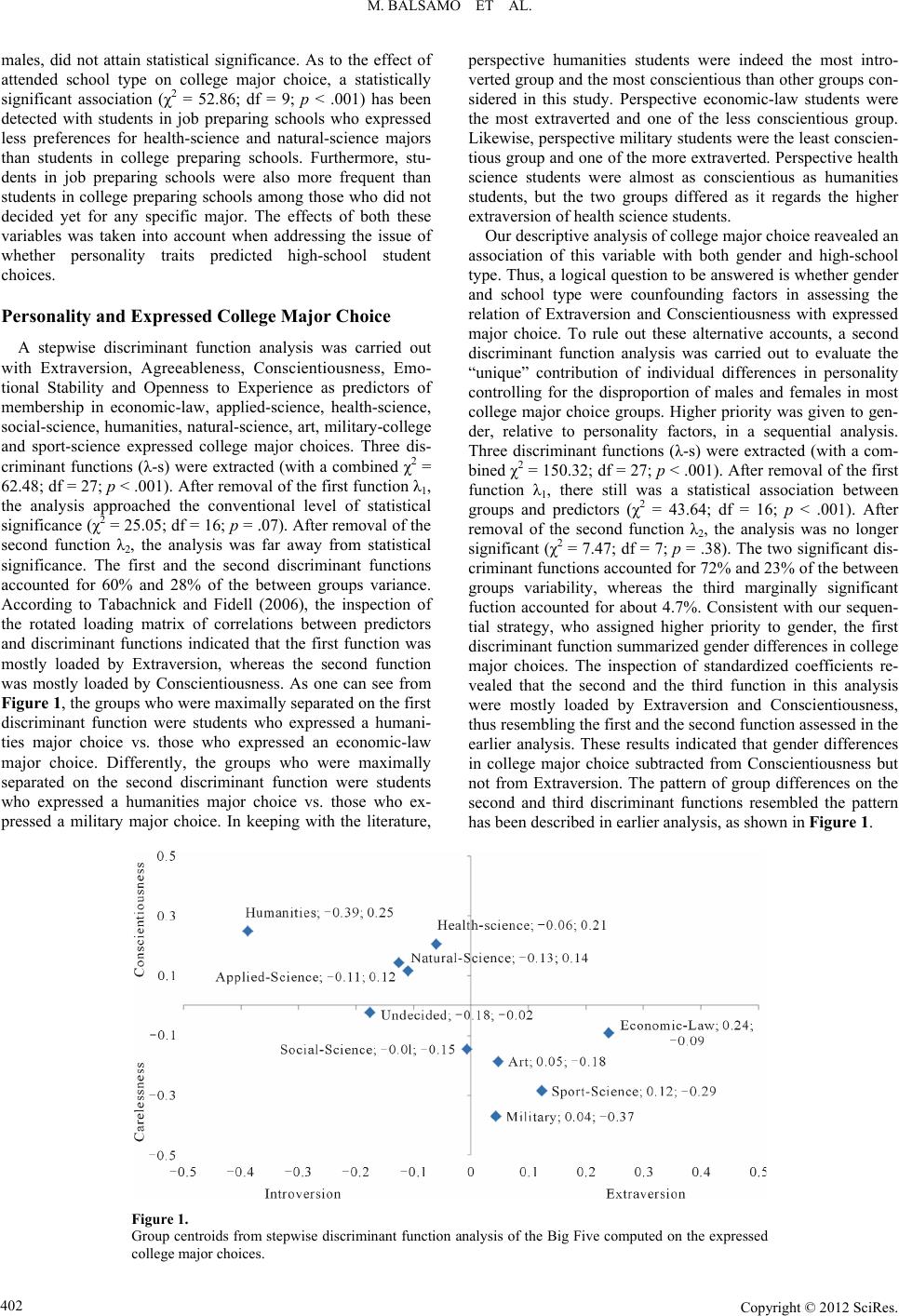

|