Advances in Physical Education 2012. Vol.2, No.2, 54-60 Published Online May 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ape) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ape.2012.22010 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 54 Physical Activity and Mobility Function in Elderly People Living in Residential Care Facilities. “Act on Aging”: A Pilot Study Monica E. Liubicich1, Daniele Magistro1, Filippo Candela2, Emanuela Rabaglietti2, Silvia Ciairano1,2 1University Interfaculty School of Motor Science (SUISM), Research Centre in Motor and Sport Science, University of Turin, Turin, Italy 2Department of Psychology, University of Turin, Turin, Italy Email: monica.liubicich@unito.it Received February 15th, 2012; revised March 18th, 2012; accepted March 27th, 2012 The present study aims at investigating the changes between pre-test and post-test in mobility function, balance, and gait after a physical activity program in a sample of elderly people. Forty-four individuals living in residential care facilities were recruited, with a mean age of 85 (SD = 6.6) in the control group and 84.26 (SD = 7.4) in the intervention group. We collected baseline and post-test measurements for the Tinetti Test. The findings showed that the physical activity intervention had a positive effect on physical functions. There was a statistically significant change between the means of the two groups over time; the intervention groups showed a stable condition with respect to overall mobility function, balance, and gait while the control group showed decreased performance at the post-test. These results underline that even in critical conditions, relatively simple training may promote a more positive adjustment to old age. Keywords: Aging; Physical Functioning; Exercise; Balance; Gait; Mobility Function Introduction Demographic projections and epidemiological studies show that throughout western society the population is getting older and older and that aging may be associated with an increase in disability and frailty, although most of the elderly population stay relatively healthy for a long time (World Health Organiza- tion, 2002; Aromaa & Koskinen, 2004; Stenzelius, Westergreen, Thorneman, & Rahm Hallberg, 2005). The level of decline of older people in physiological and psychological aspects (Shum- way-Cook & Woollacott, 2000) is characterized by great indivi- dual variations due to both personal factors (idiosyncratic life events and personal characteristics) and extrinsic factors (envi- ronmental and social contexts and opportunities) that lead to significant differences in performance (Spirduso, Francis, & MacRae, 2005). However, around 20% of people aged 70 or above experience limitations in carrying out daily activities and/or are affected by physical disabilities, resulting in a loss of autonomy (Manton & Land, 2000; Pennix et al., 2002). Among all other aspects, motor skills also decrease as indi- viduals grow older (Shea, Park, & Braden, 2006; Voelcker-Rehage & Alberts, 2005) and especially certain parameters such as ba- lance, flexibility, and strength, which are predictors of depend- ence in the Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) (Guralnik et al., 2000). The present study represents the continuation of a series of pilot research projects (Ciairano, Liubicich, & Rabaglietti, 2010) that investigate the positive effects of a physical activity pro- gram on physical functioning in an Italian sample of older peo- ple in residential care facilities. In our previous research we focused on the psychological aspects of older people and health perceptions, while this present study analyzes objective aspects related to the physicality of older people. Description of the Problem Motor difficulties, the inability to manage daily activities, and serious illnesses are risk factors for becoming dependent on others and subsequent institutionalization (Hirvensalo, Ratanen, & Heikkin, 2000; Laukkanen, Leskin, Kauppinen, Sakari-Rantala, & Heikkinen, 2000; Agüero-Torres, von Strauss, Viitanen, Win- bland, & Fratiglioni, 2001; Rockwood et al., 2004). With respect to ways of facing the dependence of older peo- ple on others, different European countries have different wel- fare politics and/or cultural traditions to deal with this problem (Anttonen & Sipila, 1996; Bettio & Platenga, 2004; Lucchetti, Mazzoni, Principi, & Greco, 2007). Generally speaking, in nor- thern European and especially Scandinavian countries, the wel- fare ratio addressed to the aging population is very high, and institutionalization is more likely proposed to very ill elderly who cannot receive sufficient medical care in their own homes. In southern European countries, traditionally the family com- pensates for low levels of public welfare, and institutionalize- tion is more likely to be proposed to older people who are alone or who have a very weak social network that cannot support them in their daily activities. Irrespectively to the cause of in- stitutionalization, we know that it represents an adjunctive chal- lenge for the elderly. In fact the study by Galloway and Jokl (2000) showed that at least 30% of older people experience deeper and quicker physical decline after entering residential care facilities, probably also because in these institutions older people lose their usual pattern of daily habits and their social context at the same time. Although the institutionalization of elderly people is not de- sirable in principle, it is undeniable that it is the only reason- able solution especially at very high levels of frailty. Thus, we need to explore in which ways we can prevent the decline of older  M. E. LIUBICICH ET AL. people who are also in the precarious condition of institution- alization in order to avoid that this decline becomes a greater loss for the elderly themselves, at a greater cost for society, and to endorse more lively participation within the facilities. We know that physical activity can be used, also at older ages, for promoting the overall wellbeing of individuals (Gal- loway & Jokl, 2000). Several studies have shown that physical activity interventions lead to modifications in behavior related to the risk of falls (Barnett, Smith, Lord, Williams, & Baumand, 2003; Suzuki, Kim, Yoshida, & Ishizaki, 2004; Means, Rodell, & O’Sullivan, 2005), since even limited movement can initiate a process of change over the short or medium term (van der Bij, Laurant, & Wensing, 2002). Besides this, as reported in the meta-analysis carried out by Beswick et al., (2008), increasing the amount of daily physical activity reduces the risk of institu- tionalization, hospital admissions, falls, and disabilities. Different types of training have proven to be capable of im- proving the motor skills and the quality of life of elderly people (Baker, Atlantis, & Fiatarone, 2007), in particular if the abilities of each individual are taken into account in terms of intensity and workload. The World Health Organization guidelines (1999) identify aerobic endurance, resistance strength, flexibility, and balance as related to the health of the elderly. Aside from this, these guidelines suggest group physical activity in order to promote increased psycho-social benefits and to provide further motivation to continue the program and persevere in older peo- ple. The older people showed some preference for the physical activity programs that include exercises designed to improve balance as well as flexibility and gait (Norton, Galgali, & Cam- pbell, 2001; Day et al., 2002). In compliance with the indica- tions provided by the American College of Sports Medicine (2000), physical activity programs designed for the elderly who are already in residential care facilities have to be addressed at preserving the skills that are functional towards maintaining independence as long as possible, slowing down the processes that may lead to disability, and educating the elderly about an active lifestyle. These indications also emphasize that daily physical activity and physical activity programs may contribute to overall individual wellbeing and play a key role in prevent- ing a wide range of different illnesses. Some interventions showed specific positive effects on strength, flexibility, mobil- ity, and balance (Rydwik, Frandin, & Akner, 2004). What is generally acknowledged is that it is crucial to design interven- tions that are able to prevent the most negative consequences of institutionalization, like the loss of acceptable levels of auton- omy, which in turn may start a negative vicious cycle of con- stant deterioration. Despite widespread awareness of this, very few studies, especially in countries outside the northern Euro- pean ones, have addressed the issue of investigating the effi- cacy of interventions specifically aimed at improving mobility function and/or its stable maintenance, which is the basis for preserving autonomy as long as possible in very old groups of people. The majority of the previous studies concentrated on the younger bracket of the elderly population (aged between 65 and 75) living in normal condi- tions (among others see: Marsh, Miller, Rejeski, Huttona, & Kritchevsky, 2009; Bird, Hill, Ball, & Willimans, 2009). The present study aims at considering older institutionalized elderly in a southern European country. Purpose We looked at two groups of older people living in three resi- dential care facilities to describe the physical functioning changes from pre-test to post-test in relation to their participation in a physical activity program. The objective of this research is to test the effects of a physic- cal activity program on mobility function, in particular balance and gait which are strictly related to walking, in the case of insti- tutionalized elderly people. We assumed that participating in a physical activity program could improve or at least retain an elderly person’s mobility function as a whole and/or in its two components of balance and gait, or keep it constant over time. As anticipated, physical activity may be a protective factor for the institutionalized eld- erly and it increases so that the individuals can be independent for as long as possible (Fried, Ferrucci, Darer, Williamson, & Anderson, 2004; Gill et al., 2004). Methods Study Desi gn The intervention was introduced in two residential care fa- cilities of the Piedmont region in the north of Italy and another residential care facility, in the same area, was used as the con- trol group: Currently, more than 5000 older people of the Piedmont region live in residential care facilities (Banchero, et al., 2009). First, from the list offered by the Health Office of the Piedmont Region, we selected 30 facilities that have similar features in terms of their accordance to the National Health Service, the number and typology of guests (range from 80 to 120), the intermediate social and economic conditions of the guests (all the guests in these facilities are requested to contrib.- ute a small amount for the care they receive), and services of- fered to the older people (presence of nurses, healthcare opera- tors, physiotherapist, and psychologist). Second, we randomly extracted six of these facilities from the list and all of them agreed to participate in the study. Third, we excluded three of the facilities because we did not find enough self-sufficient seniors in order to create a physical activity group. Then we assigned two of the remaining facilities to the experimental condition and one to the control condition. The facilities that were selected accommodate both self-suf- ficient older people (i.e., individuals who can walk, eat, and use the bathroom independently) and dependent older people (re- quiring assistance in the basic activities of daily life). All of them are private institutions, but linked to the Public Health Service through a funding agreement. Physical Activity Intervention General—This intervention consisted of two one-hour sessions per week for 16 weeks. It was offered to a group of self-suf- ficient older people living in a residential care facility. The physical activity was done in small groups and qualified in- structors conducted the sessions. All the instructors had a uni- versity degree in physical education and sports-related fields and were specialized in physical fitness training for the elderly (Ciairano et al., 2006). They were selected on the basis of their results in the university courses “Adapted Physical Activity” and “Health and Old Age”. That is, we selected only people who achieved a final grade higher than the 95th percentile of the grade distribution for each of these subjects. The set of activities was specifically designed for our re- search. The intervention protocol, as advised by the American Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 55  M. E. LIUBICICH ET AL. College of Sports Medicine (2007), focused on three specific objectives: mobility, balance, and resistance strength. The in- tervention was organized so as to reproduce the movements and gestures of daily life, considering the three aims above. The intervention was designed with a gradual increase of the pa- rameters of work intensity and complexity of exercise. Participants In each residential care facility the older participants, both the intervention group and the control group, were selected by the director of the residential care facility, who is a trained phy- sician, from among all the older people living in the facility. The three criteria for inclusion were: 1) self-sufficiency (see above), 2) absence of serious chronic and/or acute diseases, and 3) intact cognitive functions, which were directly verified by the researchers. The Mini Mental Test (Folstein & McHugh 1975) was used to evaluate cognitive functions, and all the par- ticipants reached or exceeded the minimum score of 23. First, our study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Turin, and second the participants were in- formed that participation in the study was voluntary and confi- dential. All the selected individuals agreed to participate and gave their written informed consent, in accordance with Italian law and the ethical code of the Italian Association of Psycholo- gists (1997). Those who were included in the experimental group partici- pated in the physical activity program, while the control group was comprised of individuals who did not participate in the program and continued their normal activities planned in the facility. With respect to the physical activity of the older people in the control group, they simply continued their free activity of walking in the facility’s garden since they are self-sufficient individuals. The sample comprised of 44 people, 16 of whom were males (36%; 2 in the control group and 14 in the experimental group) and 28 females (64%; 9 in the control group and 19 in the ex- perimental group). We did not find differences between the experimental and control group (χ = 2,1, d.f. = 1, p = .27). The mean age was 85 (SD = 6.6) for the control group and 84.26 (SD = 7.4) for the experimental group (t-test = –.34, d.f. = 41, p = .73). All the participants lived in the residential care facility permanently. With regard to marriage status, the majority were widows/widowers (N = 26) or married (N = 8), while others had never married (N = 7), or were divorced (N = 3): No dif0 ferences were found between the experimental and control group (χ = 3,7, d.f.= 3, p =.29). In terms of education, two lev- els were considered: “low”, corresponding to compulsory edu- cation (only primary school) and “high”, corresponding to addi- tional non-compulsory education (more than primary school). 0In this case we also did not find significant differences be- tween the two groups (χ = 2,1, d.f. = 1, p =.64). The average level of education of the men and women in the sample was in line with that of the age-matched national population (National Institute of Statistics, 2006; Costa, Migliardi, & Gnavi 2006). In fact, 75% of the participants had received only compulsory education, exactly like about 70% of the national population. Former occupations were divided into manual (N = 31) and non-manual labor (N= 13) and there were no differences be- tween the experimental and control group (χ = 3,2, d.f. = 1, p =.35). With regard to previous participation in organized exer- cise or sporting activities, the majority of individuals (N = 27) had never participated and there were no differences between the experimental and control group (χ = 1,3, d.f.= 1, p =.31). The main characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1. Procedure The mobility functions (Köpke & Meyer, 2006) of balance and gait in the elderly were assessed using the Tinetti Test (Ti- netti, 1986). The version of the Tinetti Test used for this study included a total of 16 items that corresponded to the mobility functions: 9 items corresponded to balance, and 7 to gait. Of the items, 11 had a score ranging from 0 to 2, 6 items had a score ranging from 0 to 1, with a maximum total score of 28 for mo- bility functions. The maximum scores were 16 for balance and 12 for gait. The higher the total score, the better the perform- ance. All participants had to perform the Tinetti Test twice, during the pre-test and post-test. Data and Statistical Analysis We ran repeated measures analyses of variance for each of the aspects considered in the present study. In every model, we examined one between-factor experimental condition (intervene- tion and control group) and one within-factor condition of time (pre-test and post-test). In addition, we examined the interaction term between the experimental condition and the time. Results In general, the intervention group and the control group dif- fered with respect to the mobility function (total Tinetti Test) as well as balance (Tinetti Test balance subscale) and gait (Tinetti Test gait subscale) (Table 2). Mobility function was higher in the intervention group (19.48 vs. 7.95); balance was also higher in the intervention group (11.78 vs. 4.36), and the same was true for gait (7.82 vs. 3.31). The differences between the intervention and the control group were statistically significant for the mobility function (F = 26.72, p < .001, η2 = .383), balance (F = 34.43, p < .002, η2 = .445), and gait (F = 14.08, p < .001, η2 = .247). As for the effects of the intervention (Figure 1), mobility function decreased between the pre-test and post-test in the control group (from 11.36 to 4.54), while it remained relatively stable in the intervention group (from 20.09 to 18.88). The interaction between the condition and the time was significant and there were noticeable differences concerning the decrease in mobility function between the intervention group and the control group (F = 7.15, p < .011, η2 = .143). For what concerns balance (Figure 2), a decrease between the pre-test and post-test was observed in the control group (from 6.64 to 2.64), while it remained relatively stable in the experimental group (from 11.97 to 11.59). The interaction be- tween condition and time was significant, the decrease in bal- ance was markedly different when looking at the intervention group and the control group (F = 7.24, p < .010, η2 = .144). Finally, the control group (Figure 3) showed a decrease in gait (from 4.73 to 1.91), while the intervention group remained stable (from 8.24 to 8.24). Also in this case, there were significant differ- ences in the decrease of their gait (F = 5.26, p < .027, η2 = .109). In general, the effect of the intervention explains a proportion of variance—around 10% - 15%—which is reasonably high when considering the small sample size of the present study according to Cohen (1988). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 56  M. E. LIUBICICH ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 57 Table 1. Characteristics of participants (N, %). Group Variable Category Control Experimental N % N % Female 9 82 19 58 Gender Male 2 18 14 42 No 8 73 19 58 Past participat ion in physical activitie s Yes 3 27 14 42 North Italy 10 91 30 91 Center Italy / / 2 6 Original Region South Italy 1 9 1 3 Never married 1 9 6 18 Married 1 9 7 21 Widow 9 82 17 52 Family condition Divorced / / 3 9 Past job Manual 10 91 21 64 Non manual 1 9 12 36 Level of education Only Primary School 9 82 24 73 More than Primary School 2 18 9 27 Age Mean (SD) 85 (6.6) 84.26 (7.4) Table 2. Results of repeated measures ANOVA. Mean (M), Standard Deviation (DS), Main Effects (ME), and interaction effects (IE) for the dependent vari- ables related to mobility functions of elderly people. Group Time Group * Time Dependent variables Control M (SE) Experimental M (SE) Pre-test M (SE) Post-test M (SE) Control Pre M (SE) Control Post M (SE) Experimental Pre M (SE) Experimental Post M (SE) ME Group ME Time IE Group * Time Tinetti Total 7.95 (1.93) 19.48 (1.1) 15.73 (1.29) 11.71 (1.17) 11.36 (2.24) 4.54 (2.04) 20.09 (1.27) 18.88 (1.16) F(1,43) = 26.7 p < .001 η2 = .383 F(1,43) = 14.63 p < .001 η2 = .254 F(1,43) = 7.15 p < .011 η2 = .143 Tinetti Balance 4.36 (1.06) 11.78 (.60) 9.30 (.70) 7.11 (.69) 6.64 (1.22) 2.64 (1.19) 11.97 (.70) 11.59 (.68) F(1,43) = 34.4 p < .002 η2 = .445 F(1,43) = 10,62 p < .001 η2 = .198 F(1,43) = 7.2 p < .010 η2 = .144 Tinetti Gait 3.31 (1.04) 7.82 (.60) 6.48 (.67) 4.66 (.60) 4.73 (1.17) 1.91 (1.04) 8.24 (.67) 8.24 (.67) F(1,43) = 14.0 p < .001 η2 = .247 F(1,43) = 17.52 p < .001 η2 = .289 F(1,43) = 5.26 p < .027 η2 = .109 Figure 2. Figure 1. Balance. Mobility function.  M. E. LIUBICICH ET AL. Figure 3. Gait. Discussion The objective of this study was to investigate how participa- tion in a physical activity program affects the mobility func- tions of a group of elderly people staying in residential care facilities, focusing in particular on its effects on balance and gait. As for the first research hypothesis, we wanted to deter- mine if participating in a physical activity program can improve an elderly person’s mobility function or keep it stable over time. Mobility, understood as the ability to independently move around in one’s environment, is a fundamental expression of an individual’s autonomy. A decrease in mobility function is often a predictor of future health issues that might lead to disability. In line with the reference literature about the effects of physical activity on a comparable sample with a similar health condition and age, (Nakagawa et al., 2008; Netz, Wu, Becker, & Tenen- baum, 2005; Snow, Shaw, Winters, & Witzke, 2000), the re- sults of our research seem to point to physical activity as an indispensable tool to preserve residual skills and to curb their loss, which is fundamental in order to be independent when walking. Secondly, we assumed that our specifically designed physical activity program would improve both the balance and gait of institutionalized elderly people and preserve these over time. Our results concerning balance and gait are very similar to those reported in the literature. Indeed, physical activity pro- grams based on resistance strength training presented to sam- ples of institutionalized older people do help preserve their lower limb strength or slightly increase it (Jessup, Horne, Vishen, & Wheeler, 2003), which is directly related to walking autonomously. As for balance, issues such as the physiological aging process, the loss of straightening reflexes, a decrease in muscular strength to preserve an upright posture, the vulner- ability of sensory organs, as well as an increase in swaying justify the postural instability typical of the older ages. Hence, elderly individuals must concentrate and completely focus their attention in order to keep their balance. The various compo- nents of gait undergo changes simply due to the natural aging process. The initiation of steps, its height, continuity and sym- metry, path deviation, and turning while walking are compo- nents of gait that mirror an older person’s confidence and effi- ciency in walking. If difficulties in keeping one’s balance and walking are ascertained through the Tinetti Test (Tinetti, 1986), this can help predict an increased risk of falls. As for the as- sumption that the older individuals who participated in our physical activity program improved or retained these functions to a higher extent than the control group, the results indicate that walking skills were preserved in the intervention group more so than in the control group. Our research seems to sup- port the hypothesis that physical activity programs can trigger positive changes even in the short term, thus enabling elderly individuals to better manage those actions that imply simple movements, such as moving from place to place within one’s dwelling, going to the bathroom autonomously, and taking short walks. When comparing the intervention group to the control group, the variation between pre-test and post-test data in relation to the age of the sample and to the institutionalized condition, highlights the protective function played by physical activity on the health of the older elderly, for whom a good overall physic- cal condition is a key precondition for an independent daily life. Facing and accepting the challenges of a changing body, redis- covering the joys of movement, and socializing, as well as once again learning to trust oneself, preserving one’s skills and ap- plying them to daily living in order to retain one’s autonomy as long as possible—all of this can be turned into a great chance to promote health and to prevent a wide range of risks faced by the elderly. The limitations of this study mainly concern the small num- ber of individuals in the sample, justified by the difficulties in recruiting older people living in residential care facilities that were self-sufficient and met the criteria of our research. Resi- dential care facilities in Italy are actually becoming more and more the places where the oldest elderly live in a situation of frailty and are no longer able to lead a fully independent life (Banchero et al., 2009). Moreover, their dependence on others in daily life activities is most likely linked to the progress of old age and to the fact that some debilitating diseases have become chronic. Despite the limitations concerning the sample type, some stimulating observations can be drawn from our study. Firstly, this study is one of the first research projects carried out in Italian residential care facilities with the purpose of investigat- ing the effects of motor training on a sample of institutionalized older people. The reference literature mostly regards intervene- tions carried out in northern European and north American countries, which are not indicative of the Italian context that is characterized by a different social and healthcare system and in which the elderly are mostly looked after by their relatives. Secondly, this study fits into the new line of research on the most frail segment of the population—the older elderly in resi- dential care facilities—evidence that frailty is a process that requires great attention in the future from researchers in order to predict those elderly who are at risk of ADL dependence and to identify effective interventions, such as physical training programs, to prevent or delay the onset of dependence (Guilley et al., 2008). Moreover, individual psychological resources can play an important role in the maintenance of these benefits in the short and medium term: in the oldest of the elderly the maintenance of these activities is strategic for both physical and psychological wellbeing (Caplan & Schooler, 2003). Conclusion Considering the growing numbers of the weaker portion of the population, made up of people over 80 who live in a institu- tion, this study proves that simple physical activity programs, conducted by suitably trained instructors with a degree in physical Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 58  M. E. LIUBICICH ET AL. education or sports-related fields, can bring about changes in the physical functioning of the elderly. Setting realistic goals and designing activity protocols that take scientific evidence into consideration (in relation to the type, intensity, and fre- quency of the physical training) might lead to constructing and implementing interventions that are useful to improving the general adjustment of citizens and their quality of life. Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge Regione Piemonte, Assessorato Ricerca, Innovazione e Sviluppo Bando Scienze Umane 2009, for contributing to this ACT ON AGEING pilot study. REFERENCES Associazione Italiana di Psicologia (1997). Codice Etico della ricerca psicologica. URL (last checked 5 October 2011). http://www.mopi.it/docs/cd/aipcode.pdf Agüero-Torres, H., von Strauss, E., Viitanen, M., Winbland, B., & Fratiglioni, L. (2001). Institutionalization in the elderly: The role of chronic diseases and dementia. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Journal of Clinic a l Epidemiology, 54, 795-801. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00371-1 American College of Sports Medicine (2007). Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American college of sports medicine and the American heart association. Jour- nal of the American Heart A s sociation, 116, 1094-1105. doi:10.1116/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185650 American College of Sports Medicine (2000). ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (6th ed). Baltimore, ML: Lippincott, Williams & Wilking. Anttonen, A., & Sipila, J. (1996). European social care services: Is it possible to identify models? Journal of European Social Policy, 6, 87-100. doi:10.1177/095892879600600201 Aromaa, A., & Koskinen, S. (2004). Health and Functional Capacity in Finland: Baseline Results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Helsinki: National Public Health Institute. Baker, M. K., Atlantis, E., & Fiatarone Singh, M. A. (2007). Multi- modal exercise programs for older adults. Age and Ageing, 36, 375- 381. doi:10.1093/ageing/afm054 Banchero, A., Bianchetti, A., Brizioli, E., Casanova, G., Gori, C., Guaita, A., & Trabucchi, M. (2009). L’Assistenza Agli Anziani Non Autosufficienti in Italia. Maggioli Editore, IRCCS-INRCA, Santar- cangelo di Romagna. Barnett, A., Smith, B., Lord, S.R., Williams, M., & Baumand, A. (2003). Community-based group exercise improves balance and re- duces falls in at-risk older people: A randomized controlled trial. Age and Ageing, 32, 407-414. doi:10.1093/ageing/32.4.407 Beswick, A. D., Rees, K., Dieppe, P., Ayis, S., Gooberman-Hill, R., Horwood, J., & Ebrahim, S. (2008). Complex interventions to im- prove physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 371, 725- 735. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6 Bettio, F., & Platenga J. (2004). Comparing care regimes in Europe. Feminist Economics, 10 , 85-113. doi:10.1080/1354570042000198245 Bird, M., Hill, K., Ball, M., & Willimans A. D. (2009). Effects of re- sistance and flexibility exercise intervention on balance and related measures in older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 17, 444-454. Caplan, L. J., & Schooler, C. (2003). The roles of fatalism, self-confi- dence, and intellectual resources in the disablement process in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 18, 551-561. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.18.3.551 Ciairano, S., Liubicich, M., & Rabaglietti, E. (2010). The effects of a physical activity programme on the psychological wellbeing of older people in a residential care facility: An experimental study. Ageing & Society, 30, 609-626. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09990614 Ciairano, S., Musella, G., Gemelli, F., Liubicich, M., Rabaglietti, E., & Roggero, A. (2006). Un intervento di promozione dell’attività mo- toria e la salute fisica e psicologica degli anziani all’interno di una residenza: valutazione di processo e di risultato. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia dello Sport, 1 , 3-11. Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Costa, G., Migliardi, A., & Gnavi, R. (2006). Verso un profilo di salute (towards a profile of health). Turin: Servizio Centrale Comunicazi- oni. Day, L., Fildes, B., Gordon, I., Fitzharris, M., Flamer, H., & Lord, S. (2002). Randomized factorial trial of falls prevention among older people living in their own home. British Medical Journal, 325, 128- 135. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7356.128 Folstein, M., Folstein, S., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psyc h i a t r i c Research, 12, 189-198. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 Fried, L. P., Ferrucci, L., Darer, J., Williamson, J. D., & Anderson, G. (2004). Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbid- ity: Implications for improved targeting and care. Journal of Geron- tology: Medical Science, 59, 255-263. Galloway, M. T., & Jokl, P. (2000). Aging successfully: The impor- tance of physical activity in maintaining health and function. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 8, 37-44. Gill, T. M., Baker, D. I., Gottschalk, M., Peduzzi, P. N., Allore, H., & Van Ness, P. H. (2004). A prehabilitation program for the prevention of functional decline: effect on higher-level physical function. Ar- chives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85, 1043-1049. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2003.10.021 Guilley, E., Ghisletta, P., Armi, F., Berchtold, A., Lalive d’Epinay, C., Michel, J. P., de Rebaupierre, A. (2008). Dynamics of frailty and ADL dependence in a five-year longitudinal study of octogenarioans. Research on Aging, 30, 299-317. doi:10.1177/0164027507312115 Guralnik, J. M., Ferrucci, L., Pieper, C. F., Leveille, S. G., Markides, K. S., & Ostir, G. V. (2000). Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the Short Physical Performance Battery. Journal of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences Medi- cal Sciences, 55A, M221-M231. doi:10.1093/gerona/55.4.M221 Hirvensalo, M., Rantanen, T., & Heikkinen, E. (2000). Mobility diffi- culties and physical activity as predictor of mortality and loss of in- dependence in the community-living older population. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 493-498. Jessup, J. V., Horne, C., Vishen, R. K., & Wheeler, D. (2003). Effects of exercise on bone density, balance, and self-efficacy in older wo- men. Biological Research for Nursing, 4, 171-180. doi:10.1177/1099800402239628 Köpke, S., & Meyer, G. (2006). The Tinetti Test: Babylon in geriatric assessment. Zeischrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatie, 39, 288-291. Laukkanen, P., Leskinen, E., Kauppinen, M., Sakari-Rantala, R., & Heikkinen, E. (2000). Health and functional capacity as predictors of community dwelling among elderly people. Journal of Clinical Epi- demiology, 53, 257-265. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00178-X Lucchetti, M., Mazzoni, E., Principi, A., & Greco, C. (2007). Promot- ing health and preventing chronic degenerative pathologies for elders: The empirical scenario in Italy. Educational Gerontology, 33, 867- 880. doi:10.1080/03601270701569135 Manton K. G., & Land K. C. (2000). Active life expectancy estimates for the US elderly population a multidimensional continuo-mixture model of functional change applied to completed cohorts, 1982-1996. Demography, 37, 253-265. doi:10.2307/2648040 Marsh, A. P., Miller, M. E., Rejeski, J., Huttona, S. L., & Kritchevsky, S. B. (2009). Lower extremity muscle function after strength or power training in older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 17, 416-443. Means, K., Rodell, D., & O’Sullivan, P. (2005). Balance, mobility and falls among community-dwelling elderly person. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 84, 238-250. doi:10.1097/01.PHM.0000151944.22116.5A Nakagawa, K., Inomata, N., Konno, Y., Nakasawa, R., Hagiwara K., & Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 59  M. E. LIUBICICH ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 60 Sakamoto, M. (2008). The characteristic of a simple exercise pro- gram under the instruction of physiotherapists for general elderly people and frail elderly people. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 20, 197-203. doi:10.1589/jpts.20.197 National Institute of Statistics (2006). Annuario statistico italiano 2006. (Statistical Italian Yearbook—2006). URL. http://www.istat.it Netz, Y., Wu, M.-J., Becker, B. J., & Tenenbaum, G. (2005). Physical activity and psychological well-being in advance age: A meta-ana- lysis of intervention studies. Psychology and Aging, 2, 272-284. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.272 Norton, R., Galgali, G., & Campbell, A. J. (2001). Is physical activity protective against hip fracture in frail older people? Age and Ageing, 30, 262-264. doi:10.1093/ageing/30.3.262 Pennix, B. W. J. H., Rejeski, W. J., Panda, J., Miller, M. E., Di Bari, M., Applegate, W. B., & Pahor, M. (2002). Exercise and depressive sym- ptoms: A comparison of aerobic and resistance exercise affects on emotional and physical function in older persons with high and low depressive symptomatology. Journal of Gero nt ol o gy , 57B, 124-132. Rydwik, E., Frandin, K., & Akne, G. (2004). Effects of physical train- ing on physical performance in institutionalised elderly patients (70+) with multiple diagnoses. A ge an d Ageing, 33, 13-23. doi:10.1093/ageing/afh001 Rockwood, K., Howlett, S. E., MacKnight, C., Beattie, B. L., Bergman, H., Hèbert, R., & McDowell, I. (2004). Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: Report from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Journal of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences Medical Sciences, 59A, 1310-1317. doi:10.1093/gerona/59.12.1310 Shea, C. H., Park, J.-H., & Braden, H. W. (2006). Age-related effects in sequential motor learning. Physical Therapy, 86, 478-488. Shumway-Cook, A., & Woollacott, M. (2000). Attentional demands and postural control: The effect of sensory context. Journal of Ger- ontology Series A Biological Sciences Medical Sciences, 55A, M10- M16. Snow, C. M., Shaw, J. M., Winters, K. M., & Witzke, K. A. (2000). Long-term exercise using weighted vest prevents hip bone loss in postmenopausal women. Journal of Gerontology Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 55, M489-M491. doi:10.1093/gerona/55.9.M489 Spirduso, W. W., Francis, K. L., & MacRae, P. G. (2005). Physical di- mensions of aging (2nd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Stenzelius, K., Westergreen, A., Thorneman, G., & Rahm Hallberg, I. (2005). Patterns of health complaints among people 75+ in relation to quality of life and need of help. Archives of Gerontology and Geriat- rics, 40, 85-102. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2004.06.001 Sukuzi, T., Kim, H., Yoshida, H., & Ishizaki, T. (2004). Randomized controlled trial of exercise intervention for the prevention of falls in community-dwelling elderly Japanese women. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism, 22, 602-611. doi:10.1007/s00774-004-0530-2 Tinetti, M. (1986). Performance-oriented assessment of mobility prob- lems in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 34, 119-126 van der Bij, A. K., Laurant, M. G. H., & Wensing, M. (2002). Effec- tiveness of physical activity interventions for older adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22, 120-133. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(01)00413-5 Voelcker-Rehage, C., & Alberts, J. L. (2005). Age-related changes in grasping force modulation. Experimental Brain Research, 166, 61- 70. doi:10.1007/s00221-005-2342-6 World Health Organization (1999). Linee guida di Heidelberg per la promozione dell’attività fisica per le persone anziane (a cura di). Medicine Sport, 52, 324-328. World Health Organization (2002). Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. Geneva: WHO, Ageing and Life Course Team, Non-communicable Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Department.

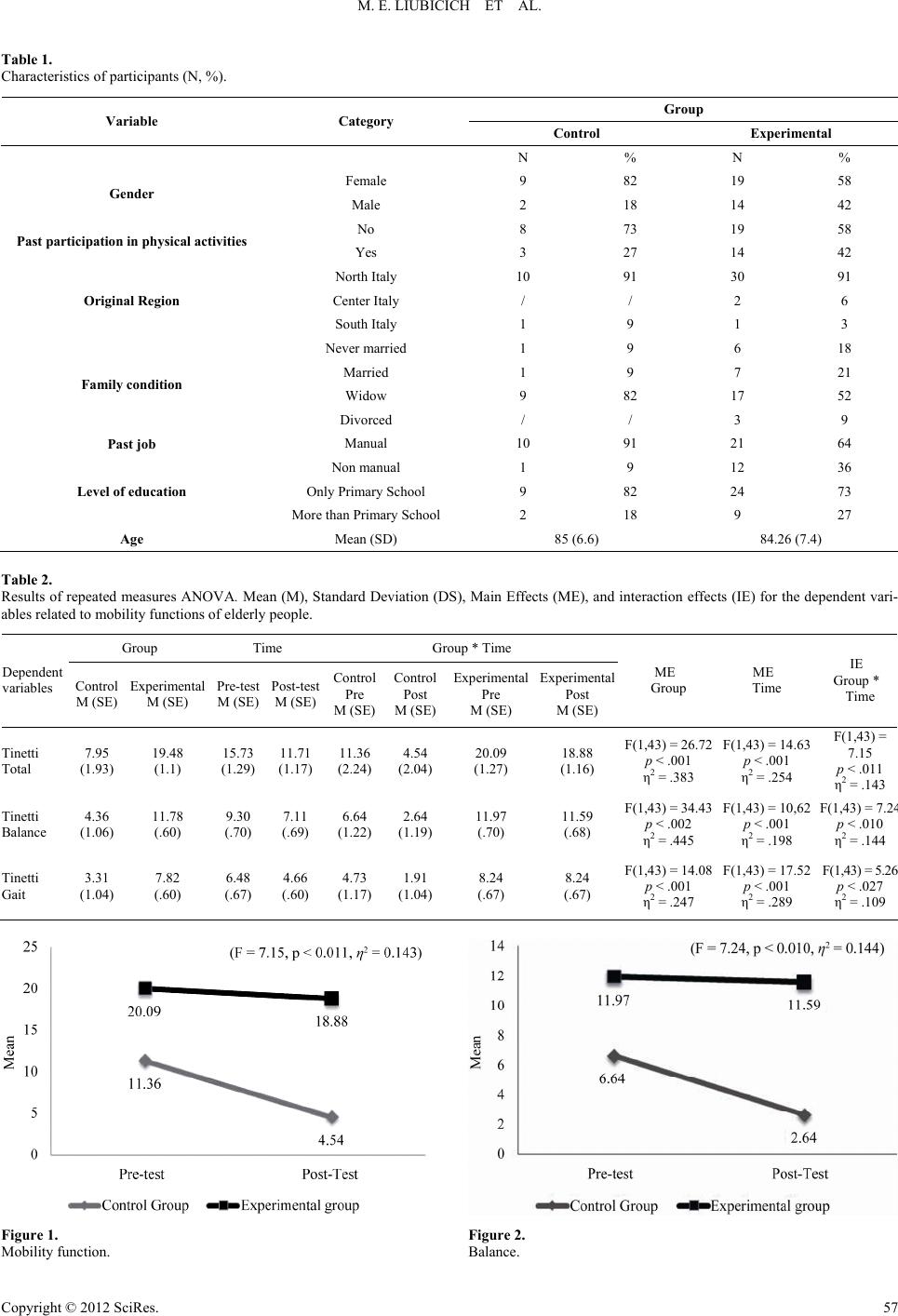

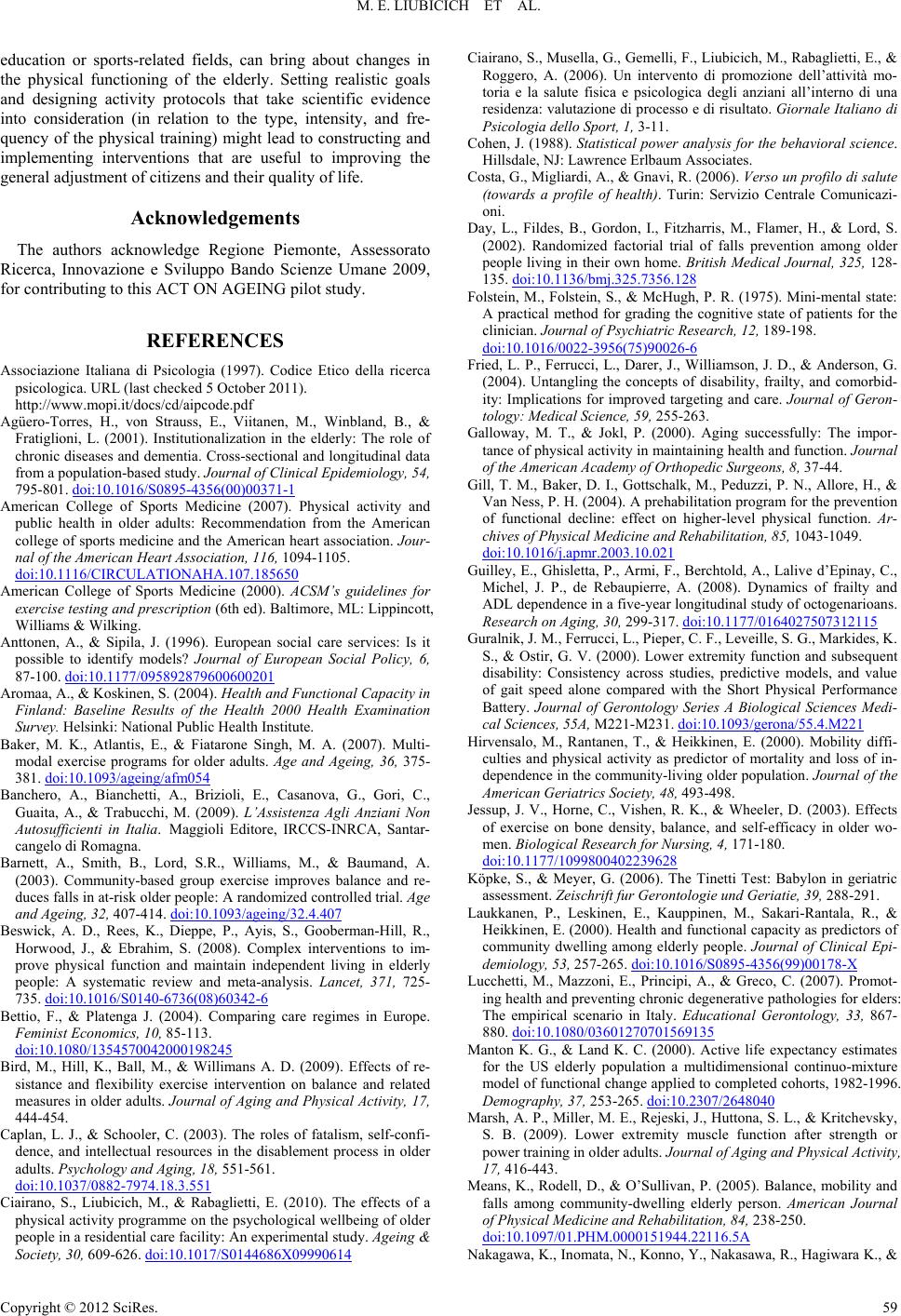

|