Open Journal of Political Science 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 9-16 Published Online April 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojps) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojps.2012.21002 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 9 Disproportionality and Party System Fragmentation: Does Assembly Size Matter? Krister Lundell Department of Political Science, Åbo Akademi University, Åbo, Finland Email: krister.lund ell @abo.fi Received October 28th, 2011; revised December 10th, 2011; accepted January 5th, 2012 The article examines the impact of assembly size on the degree of disproportionality and party system fragmentation. The hypothesis is as follows: assembly size has a negative effect on the degree of dispro- portionality and a positive effect on the effective number of parties in systems with single-member dis- tricts—in proportional electoral systems, by contrast, such a pattern does not exist. In PR systems, notably the average effective threshold supersedes assembly size in explaining the degree of disproportionality and the effective number of parties. Electoral thresholds, ordinal ballots and apparentement, which also have some impact on disproportionality and party system fragmentation in proportional elections, are ab- sent in systems with single-member districts (with the exception of ordinal ballots in alternative vote sys- tems). Moreover, the district magnitude does not vary between electoral districts and countries. Therefore, assembly size is a significant factor in majoritarian systems. The empirical analysis of 550 elections in democratic countries provides support for the hypothesis. Keywords: Electoral System; Assembly Size; Effective Threshold; Disproportionality; Party System Fragmentation; District Magnitude Introduction The purpose of the study is to examine the impact of assem- bly size on the disproportionality of election results and party system fragmentation. In the first systematic analysis of conse- quences of electoral systems, Douglas W. Rae referred to as- sembly size as the “generally neglected variable” (1967: p. 158). Yet, assembly size was not included in the analysis. Arend Lijphart has described the size of legislature as “an integral and legitimate part of the electoral system” (1994: p. 12). Rein Taa- gepera (2007) maintains that the degree of inclusiveness (i.e. the number of seat-winning parties in elections) of a simple electoral system is dependent on mainly three components: the electoral formula, the average district magnitude and the as- sembly size. In this article, it is argued and demonstrated—both theoretically and empirically—that assembly size negatively affects the degree of disproportionality and positively influ- ences party system fragmentation only in systems with sin- gle-member districts; thereby modifying, supplementing and correcting the arguments and evidence presented in earlier re- search. In proportional systems, the effect of assembly size is superseded in particular by the effect of district magnitude and formal electoral thresholds; it also competes with the impact of ballot structure and apparentement, i.e. the opportunity of com- bining party lists. In systems with single-member districts, by contrast, assembly size matters, because the district magnitude is one in each district, there are no formal electoral thresholds, and apparentement is not applied. Hence, several of the ele- ments that affect disproportionality and party system fragmen- tation in proportional systems are absent or do not vary in ma- joritarian systems, and therefore assembly size becomes impor- tant in the latter. There is wide agreement among scholars that district magni- tude is the single most important determinant of the degree of disproportionality in elections (e.g. Jones, 1993; Rae, 1967; Sartori, 1986; Taagepera & Shugart, 1989). The degree of dis- proportionality, in turn, largely affects the degree of party sys- tem fragmentation. The following example illustrates why dis- trict magnitude supersedes assembly size regarding the chances for small parties to gain representation. 50 seats are allocated by a proportional formula in 25 two-member districts. The legislature decides to improve the chances of representation for small parties by increasing the number of two-member districts from 25 to 50. Hence there are now 100 seats in the legislature. However, the threshold that guarantees a seat in any given district is still as high as one third of the votes in each district. Small parties would succeed much better, if the district magnitude was increased from two to four in each of the 25 original districts. In such a case, one fifth of the votes would guarantee representation in a district. What is more, one nationwide 100-member district would guarantee, to all intents and purposes, a proportional seat allocation be- tween a large number of parties. All other things being equal, the degree of disproportionality directly varies with district magnitude. Following this introduction, the theory of assembly size and electoral consequences is elaborated, and the hypothesis of the study is presented. Thereafter, the relevant elements of electoral systems are dealt with, beginning with the effective threshold. In the following three sections, external variables, the depend- ent variables and the dataset are described. The empirical analysis consists of three parts: the total research population, the sub-set of systems with single-member districts (SMD) and the sub-set of proportional systems.  K. LUNDELL The Impact of Assembly Size: Theory and Earlier Research The size of legislatures to a great extent varies between the countries of the world. Obviously, differences in assembly size are related to differences in country size. The population of a small country may be represented by a few dozens of deci- sion-makers, whereas a large assembly is needed in a country with a numerous population in order to be representative. Taa- gepera has established a causal link between population and assembly size (Taagepera, 1972; see also Taagepera, 2007; Taagepera & Shugart, 1989). The number of seats in the lower (or the only) chamber of the national assembly corresponds rather well to the cube root of the population—this is called the “cube root law of assembly sizes”. It predicts lower houses of 100 seats for countries with one million people, and 1000 seats for countries with 1000 million people. From this follows that assembly size varies in accordance with population size in logarithm form rather than population figures as such. Lijphart argues that assembly size matters only in small legislatures. “While the technical possibility of achieving perfect or near- perfect proportionality keeps improving as assembly size goes up”, he says, “only the smallest assembly sizes entail serious restrictions on proportionality” (Lijphart, 1994: p. 102). There- fore assembly size also has to be analyzed in logarithm form. Assembly size is defined as the number of elected seats in the lower or only chamber of the national legislative body. Taagepera (2007) maintains that the degree of inclusiveness (openness to small parties) of a simple electoral system, that is, the level of party system fragmentation, largely depends on three components of the electoral system: assembly size, dis- trict magnitude and seat allocation formula. The level of party system fragmentation, in turn, is to a great extent dependent on the degree of disproportionality of elections. Plurality/majority elections usually produce more disproportional seat allocation than elections that employ list PR allocation formulas. Assem- bly size, district magnitude and seat allocation formula can be combined in different ways, and the direction of the effect on system openness is compactly expressed in Joseph Colomer’s “micro-mega rule”: the small prefer the large, and the large prefer the small (Colomer, 2004). It means that large assem- blies, large electoral district magnitudes, and list PR allocation formulas with a large quota or large gaps between successive divisors are advantageous to small parties, and vice versa. Lijphart maintains that “if electoral systems are defined as methods of translating votes into seats, the total number of seats available for this translation appears to be an integral and le- gitimate part of the systems of translation” (1994: p. 12). He presents an example of four parties winning 41, 29, 17 and 13 per cent of the national vote in a PR election. The chances of proportional seat allocation considerably improve for a ten- member legislature in comparison with a five-member assem- bly, and perfect proportionality may be achieved, at least in principle, for a 100-member legislative body. This relationship is not as evident in plurality elections, he says, because plurality systems do not aim at proportionality (Lijphart, 1994). Not- withstanding, by referring to Taagepera (1973), Lijphart argues that there is a connection between assembly size and dispropor- tionality in plurality systems as well. He thus finds it theoreti- cally justified to regard assembly size as one of the important elements of electoral systems (Lijphart, 1994). On the face of it, Lijphart’s reasoning of assembly size and proportionality in PR elections makes sense. Yet, he mentions nothing about the constituency structure. If the election is con- ducted “at large” in a nationwide constituency, the degree of proportionality is indeed dependent on the size of the legisla- ture—however, in this case, assembly size is equal to the dis- trict magnitude. To be sure, if the district magnitude is five in all three legislatures mentioned above, greater proportionality would be achieved in the 100-member legislature than in the smaller ones, but this is, in turn, due to the larger number of constituencies rather than assembly size. In fact, a higher de- gree of proportionality in the 100-member legislature is inevi- table unless the relative strength between the four parties is approximately the same in each of the twenty districts. That being said, assembly size has an effect on the degree of disproportionality and the number of parties. A theoretical ex- planation of the impact of assembly size on the degree of pro- portionality is provided by means of the cube law, which holds that votes divided in a ratio of a:b between two parties in a plurality election results in a seat allocation in the ratio of a³:b³ (Taagepera, 1973). Disproportionality increases as the number of votes increases and/or assembly size decreases. Lijphart (1990) presents empirical evidence for this proposition in an analysis of plurality elections in the small assemblies of the Eastern Caribbean states. The factor mainly responsible for the high degree of disproportionality, he says, is the small size of the representative body. In 43 elections of totally 68 included in the analysis, the second largest party won a maximum of two seats. In almost one third of the elections, the second party gained no representation. These circumstances are, in addition to disproportional seat allocation, a consequence of the small number of seats in the legislature. Since parliamentary elections are contested in a small number of constituencies, a very lim- ited number of seats can be won by other parties than the larg- est one. In a quasi-experiment of the British elections in 1983, Taa- gepera and Shugart (1989) demonstrate that a reduction of the number of districts reduces the effective number of parliamen- tary parties. Neighboring districts were fused two by two and election results were recalculated. The procedure was repeated until there was merely one seat left. In the actual assembly, the effective number of parties was 1.98. The number dropped to 1.86 in a legislature with half the size. In a legislature with 79 seats, the effective number of parties was 1.70, whereas an 11-member assembly returned the value of 1.53. Taagepera (2007) points out that in reality voters would most likely give up on smaller parties, and as a consequence the number of both elective and legislative parties would be even further reduced. The two analyses above concern only plurality elections. By contrast, Lijphart’s research population in Electoral Systems and Party Systems (1994) consists mainly of PR elections. In a regression analysis of 57 PR systems, he finds that assembly size has a significant, negative effect on the degree of dispro- portionality, albeit not as strong as that of the effective thresh- old and electoral formula. Yet, apparentement and ballot struc- ture are not included in the model. Assembly size does not in- fluence the effective number of parties. In a larger sample of 69 electoral systems, the significant effect of assembly size re- mains when apparentement and presidentialism are controlled for. However, this sample is not restricted to PR systems. Moreover, he finds some evidence that assembly size is related to the effective number of parliamentary but not elective parties (Lijphart, 1994). Also, there is a difference between small and Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 10  K. LUNDELL large assemblies: the larger the size of the assembly, the smaller the effect of assembly size on the degree of disproportionality tends to be. In legislatures with more than one hundred mem- bers, there is no association (1994; see also Gallagher & Mitchell, 2005). Lijphart comes to this conclusion by compar- ing mean values of four categories of assembly size. The la rgest difference is observed between the smallest legislatures with less than one hundred members and the next category of legis- latures with 100 - 200 seats. The hypothesis of the present work is as follows: assembly size has a negative effect on the degree of disproportionality and a positive effect on the effective number of parties in sys- tems with single-member districts. In proportional systems, such a pattern does not exist. The influence of assembly size in PR systems is superseded foremost by the impact of the effec- tive threshold (which is thoroughly dealt with in the next sec- tion). In SMD systems, assembly size plays an important role since the district magnitude (in practice transformed into the average effective threshold) does not vary. In proportional sys- tems, by contrast, the effective threshold is more important than assembly size, because some systems have a larger average district magnitude as other systems, and several PR countries apply electoral thresholds that pose a barrier to small parties. Moreover, ballot structure and the opportunity of combining party lists are of some significance in proportional systems. In other words, the influence of assembly size on disproportional- ity and party system fragmentation in the total research popula- tion is assumed to be due to its significance among SMD sys- tems. The Effective Threshold Several studies have proven that of all electoral system components the district magnitude has the strongest effect on the degree of disproportionality (e.g. Jones, 1993; Rae, 1967; Sartori, 1986; Taagepera & Shugart, 1989). The degree of dis- proportionality, in turn, is a main determinant of party system fragmentation. As Taagepera says, “(a)rguably the most impor- tant aspect of an electoral system is the degree of squeeze it puts on representation of small parties, which influences the number of parties and is reflected in deviation from propor- tional representation” (1998a: p. 393). Electoral thresholds have a similar effect on disproportionality as small district magni- tudes. Countries with large districts often apply electoral thresholds, whereas countries with small districts do not need legal thresholds in order to counteract a highly fragmented party system. Legal thresholds may be applied at the district level, as in e.g. Spain (3 percent) and Belgium (5 percent), and for the allocation of seats at upper district levels, as in e.g. Norway (4 percent)—yet most often they are used at the na- tional level, a s in e.g. It aly (4 percent) and Slovakia (5 percent). However, the effects of district magnitude and electoral thresh- olds cannot be separately analyzed, because they covariate to a great extent (Anckar, 1997). On the other hand, as Lijphart points out, “…these two variables can be seen as functionally equivalent: they both set limits to the representation of small parties” (1997: p. 73). Taagepera and Shugart (1989) were the first to create a combined measure, called the effective magni- tude. Lijphart has presented modified versions of this measure, using the term effective threshold instead of effective magni- tude (1994, 1997). The interpretation is similar: a legal thresh- old has approximately the equivalent effect to a certain district magnitude, that is, the effective magnitude, and vice versa. The effective threshold is a rough estimate and a midpoint in a range between no representation and full representation, the so called thresholds of exclusion and inclusion (Lijphart, 1994). If a party passes the threshold of inclusion (a minimum per- centage of the vote under the most favorable conditions), it becomes possible for it to win a seat in a district. When a party passes the threshold of exclusion (a maximum perce ntage of t he vote under the most unfavorable circumstances), it is guaran- teed to win a seat in that particular district. However, the effec- tive thresholds usually vary between districts. In addition, these thresholds are also to some extent affected by the electoral formula and the number of parties that compete. Lijphart (1994) and Taagepera and Shugart (1989) deal with these problems in the followi ng way : they assume that , first, the numbe r of part ies is roughly the same as the district magnitude, second, the elec- toral formulas are roughly averaged and, third, the effective threshold is half-way between the upper and the lower thresh- olds (Taagepera, 1998b).1 Since the present work aims at modifying and complement- ing the argument put forward by Lijphart, I shall use a similar measure of effective threshold, based on the average district magnitude. The effective threshold is calculated as follows: T = 75%/(M + 1).2 Hence, if seas are allocated in a four-member district, the effective threshold is 75%/(4 + 1) = 15%. It means that a party that gets 13 percent of the vote in a four-member district will probably not win a seat in that district. However, if a party got 13 percent of the vote nationwide in one hundred four-member districts, it surely would win several seats. The effective threshold at the national level is not the same as the effective threshold at the district level. If a party fails to cross the national effective threshold, it is likely to be considerably underrepresented, but it will not necessarily fail to win any representation at all (Lijphart, 1994). Moreover, it is a question of what we are trying to predict from the effective threshold. Do we want to know the threshold which a party has to cross in order to obtain any representation at the national level or do we want to relate the effective threshold to nationwide dispropor- tionality and fragmentation? As in Lijphart’s study Electoral Systems and Party Systems (1994), the national effective th- reshold calculated on the basis of the average district magnitude is more appropriate here, because we are estimating the impact on nationwide disproportionality and party system fragmenta- tion. Taagepera (2002) has constructed a formula that measures the effective national threshold, i.e. the vote share which con- stitutes a fifty-fifty chance of securing a seat in the legislature. The key variables of the formula are average district magnitude, total assembly size and the number of electoral districts. How- ever, with regard to disproportionality and party system frag- mentation, the formula understates the importance of average district magnitude and overstates the significance of the number of districts (Gallagher & Mitchell, 2005). Moreover, a formula that includes the total assembly size is not appropriate in the present study, because the influence of the effective threshold is 1The nationwide inclusion threshold depends on the magnitude of the small- est district, whereas the nationwide exclusion threshold depends on all dis- tricts (Taagepera, 1998b). 2This is a simplified version of the formula that Lijphart applied in Electora Systems and Party Systems(1994). In a sh or t no t e published th ree years later Lijphart (1997) says that he would now opt for this streamlined formula, originally suggested by Taagepera. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 11  K. LUNDELL compared to that of assembly size. If we are interested in dis- proportionality and fragmentation, Lijphart (1994) and Taa- gepera and Shugart (1989) suggest that the average magnitude of the country as a whole should be applied.3 Taagepera refers to the formula presented above as “an overall estimate for the mean threshold of minimal representation” (2007: p. 246). The formula is an empirical expression with roots in theory (Taa- gepera, 2007). For a large part of the countries, it is relatively unproblematic to establish the average effective threshold. In some countries, however, legal thresholds, adjustment (com- pensatory) seats and combined electoral systems must be taken into account when calculating the effective threshold. Details are provided in the Appendix. Other Relevant Elements of the Electoral System The electoral formula is one of the main elements of an elec- toral system, yet it is not included among the independent vari- ables in the regression analysis. It strongly correlates with the effective threshold which means that, if included in the same model, it would most likely distort the results. Rather, electoral formula is dealt with by analyzing two sub-sets of elections, namely systems with single-member districts and proportional systems. The former category consists of the single-member plurality formula, the two-round system and the alternative vote. The block vote version of plurality systems is not included in that sample, because it employs multi-member districts. The sub-set of proportional systems consists of proportional list systems, the single transferable vote and mixed-member pro- portional systems. Despite combining two electoral formulas, the last mentioned is included among PR systems, because the final seat allocation is proportional. In addition to all electoral formulas included in these two sub-sets, mixed-member ma- joritarian systems, the block vote and the single-non-transfer- able vote are part of the total research population. Ballot structure and apparentement are also of some impor- tance with regard to electoral consequences. Both variables may be classified in different ways (see e.g. Cox, 1997). As for disproportionality and fragmentation, the most central feature of ballot structure is whether the voter may cast one or several votes. We can thereby distinguish between categorical and ordinal ballots. The theoretical link between ballot structure and disproportionality is indirect, relating to the two-way relation- ship between disproportionality and the party system. Dispro- portionality decreases multipartism but, to some degree, multi- partism also increases disproportionality (Lijphart, 1994). Ap- parentement implies that parties are allowed to connect their lists, and the combined vote total is used in the initial seat allo- cation. This opportunity improves the chances for small parties which otherwise would be considerably disadvantaged. Lijphart (1994) has found that apparentement has a positive impact on proportionality when the effective threshold is controlled for, whereas Anckar (1998) has reported a positive, significant ef- fect of apparentement on the effective number of parties. External Variables Party system structure is also related to other factors than those that are part of the electoral system; particularly country size, presidentialism and cultural heterogeneity. Yet, country size cannot be included in the regression models since both population and area strongly correlate with assembly size.4 In presidential elections, which may be seen as single-member district elections in the country as a whole, votes are mainly cast for candidates of the two largest parties, and this pattern is assumed to be reflected in parliamentary elections. However, the association between presidentialism and party system frag- mentation is dependent on two conditions: the presidential elec- tions must be conducted according to the plurality rule, i.e. in a single round, and they must be held at the same time as parlia- mentary elections (Shugart & Carey, 1992). Presidentialism is also assumed to have an indirect effect on disproportionality. Because of a relatively small effective number of parties in governmental systems as described above, the degree of dis- proportionality is expected to be smaller as well (Jones, 1993; Lijphart, 1994). Hence, in the empirical analysis, presidential- ism is controlled for. I shall apply Sartori’s definition of presi- dentialism: the president 1) must be popularly elected, 2) can- not be discharged by a parliamentary vote, and 3) appoints as well as directs the government (Sartori, 1994). The occurrence of several ethnic groups is assumed to influ- ence the party system structure in plurality systems. Through- out the years, some qualifications have been added to Du- verger’s (1964) theory of plurality elections and two-party sys- tems. Perhaps the most important exception is concerned with countries in which ethnic and other minorities are regionally concentrated. If ethnic minorities constitute a majority of the population in some regions, “third” parties may in some elec- toral districts obtain a fair-sized share of seats (Sartori, 1994). Indeed, Duverger (1964) acknowledged that the contesting parties may be different in different parts of the country, thereby making a fragmented party system at the national level possible. Ethnic heterogeneity is controlled for in the sub-set of SMD systems.5 3Another related problem concerns the effective threshold in countries with districts of unequal magnitude. Taagepera (1998a) uses Finland as an exam- le. The average magnitude is 13.3 (200 seats allocated in 15 districts), which returns an effective threshold of 5.2 per cent. However, the three smallest districts in 1983 had a magnitude of 1, 7, and 8 whereas the two largest ones had 20 and 27 seats. In the largest di strict, the effecti ve thresh- old was as low as 2.7 per cent, and thi s is the threshold that a small p arty had to cross in order to get a seat in the parliament. Taagepera concludes that ecause of large deviation in magnitude, party system fragmentation in Finland is greater than it would be if all districts were of equal size. So why do we not calculate the effective threshold on the basis of the largest district then? First of all, in a worldwide comparison, it is difficult to obtain reliable information on the size of districts in all countries. Secondly, and more importantly, the results would be distorted if we only consider one district. Small parties might get one or two seats in the two largest districts in Finland but that is not always the case. The largest district is usually the one that includes the capital. Quite often, however, small ethnic parties are regionally concentrated in smaller districts elsewhere (Anckar, 2002). Therefore, the average magnitude and threshold is a better solution than paying attention only to the lar g est district. Dependent Variables Disproportionality and party system fragmentation are the dependent variables of the study. Disproportionality is meas- ured by means of Gallagher’s least-squares index (1991), cal- culated in the following way: the difference between vote and seat shares for all parties are initially squared and then added. 4In the research population of the study, the correlation coefficient between assembly size and logged population is 0.82. Almost perfect correlation prevails between logged assembly size and l ogged pop ulation: 0.92. 5Values on ethnic heterogeneity provided by Anckar, Eriksson and Leskinen (2002) are applied. The degree of fragmentation is calculated according to the index of ethnic fractionalization proposed by Rae and Taylor (1 970). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 12  K. LUNDELL Thereafter, the sum is divided by two and the square root of this value is taken. Higher values indicate higher degrees of dis- proportionality. Party system fragmentation is measured by Laakso and Taagepera’s (1979) index, “the effective number of parties”, calculated as one divided by the sum of squared seat shares for each party. The index may also be calculated on the basis of vote shares. Lijphart (1994) included two measures: the effective number of elective parties based on vote shares and the effective number of parliamentary parties based on seat shares. I include only the latter because the analysis focuses on party system structure in the legislature. Furthermore, in Li- jphart’s study, electoral system elements are more strongly related to the effective number of parliamentary parties than the effective number of elective parties. Data When studying effects of electoral systems, some level of democracy must prevail. The most widely used source for de- termining the level of democracy is Freedom House’s annual survey of political rights and civil liberties. For each of the two dimensions, a scale ranging from one to seven is applied, with one representing the most democratic and seven the least de- mocratic. In addition, countries are categorised as “free”, “part ly free” and “not free”. The latter classification is used for select- ing the research population of the study. First, only elections conducted during years of “free” status are included. Second, in order to qualify for inclusion, a country must have been classi- fied as “free” or “partly free” each year since t he previous elec- tions. The analyzed time period is from 1972 to 2008, i.e. ever since Freedom House has provided ratings of the level of de- mocracy. All parliamentary elections (to the lower or only chamber) that fulfil the criteria above are included in the analy- sis,6 which results in a total research population of 550 elec- tions.7 The sub-sets of SMD systems and PR systems consist of 166 and 315 elections, respectively. Empirical Analysis The Total Research Population The empirical analysis begins with the total research popula- tion. Assembly size negatively correlates with the degree of disproportionality and positively with the effective number of parliamentary parties. The coefficients are –0.315 and 0.263, respectively, and significant at the 0.001-level. Nevertheless, the effective threshold is much more strongly associated with the dependent variables; the correlation coefficients are 0.687 and –0.543, respectively. Ballot structure and apparentement are also negatively associated with disproportionality and posi- tively with party system fragmentation. In Table 1, multivariate patterns are given, applying OLS regression analysis. Assembly si ze has a negative impact on the degree of disproportionality and a positive impact on the effect- Table 1. The effect of assembly size, effective threshold, ballot structure, ap- parentement and presidentialism on disproportionality and the effective number of parliamentary parties, OLS regression. Degree of disproportionality Effective nu mber of parliame ntary parties (Constant) 7.058 6.029*** 2.892 10.183*** Assembly size (log) –2.401 –.156 –4.859*** .507 .149 4.222*** Effective t h reshold .311 .652 19.113*** –.048 –.451 –12.110*** Ballot structu re (dummy) –.248 –.015 –.474 –.156 –.044 –1.246 Apparentement (dummy) .407 .018 .557 1.133 .229 6.345*** Presidentialism (dummy) .012 .000 .011 –.349 –.050 –1.437 R-square .495 .375 F-sig. *** *** N 530 543 Note: In each c ell, from to p d ownwar ds , figures indicate the regression coefficient, the standardized regression coefficient and the T-value, ***=sig. < 0.001; Sources: Anckar (2002); Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections; Countries of the World; Inter-Parliamentary Union; Lijphart (1994); Parties and Elections in Europe. tive number of parliamentary parties when other relevant vari- ables are controlled for. However, the most important variable with regard to both disproportionality and fragmentation is the effective threshold. Apparentement also has a stronger effect than assembly size on the effective number parties. Ballot structure has no independent effect on the dependent variables. As mentioned earlier, Lijphart maintains that assembly size affects the degree of disproportionality in small assemblies but not in large ones. In Lijphart’s analysis (1994), no influence of assembly size was found in a multiple regression with regard to the effective number of parties. Although the difference be- tween small and large legislatures has already been taken into account by using assembly size in logarithm form, I have also run a separate analysis (not presented in table format) in a sam- ple of assemblies with less than one hundred seats. There is a strong bivariate association between assembly size and the degree of disproportionality. However, in the multivariate analysis, assembly size has no impact—the effective threshold is the sole significant variable. Yet, it does not falsify Lijphart’s statement, because his sample consisted of PR systems only. Lijphart excluded majoritarian systems because in his research population of established democracies, majoritarian elections were conducted mostly in very large assemblies. Therefore we have to return to the matter when the sub-set of PR systems is analyzed. 6Countries that lack political parties (Federated States of Micronesia, Mar- shall Is lands, Nauru, P alau an d Tuval u) are ex clud ed fro m the anal ysis since they have no party systems, and consequently no values on the dependent variables of the study. Another four countries (Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Samoa and S olo mon Islan d s) are ex clud ed becau se i n mos t electi on s, a l arg e part of the successful candidates have been elected as independents. 7All data used in this study can be received from the author upon request. Some data, mainly on the degree of disproportionality, are missing. There- fore, N in the regression analysis of the total research population is smaller than 550. Systems with Single-Member Districts Next, SMD systems are separately analyzed. Presidentialism and ethnic heterogeneity are included as external control vari- ables. Ballot structure is the only electoral system characteristic that we need to control for when analyzing the effect of assem- bly size in this sample, because no formal electoral thresholds Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 13  K. LUNDELL are applied, apparentement does not exist in SMD systems, and the average district magnitude in each country is one. Assembly size correlates more strongly with the dependent variables in SMD systems than in the total research population; the correla- tion coefficients are –0.372 and 0.473, respectively, and sig- nificant at the 0.001-level. As shown in Table 2, the effect of assembly size on disproportionality remains when other factors are controlled for, yet the impact of ballot structure and espe- cially presidentialism is stronger. Concerning the effective number of parliamentary parties, assembly size is the most important variable. Proportional Systems There is a significant bivariate association between assembly size and party system fragmentation in the sub-set of propor- tional systems, yet not as strong as that between the effective threshold and fragmentation. The effective threshold strongly correlates with disproportionality—in contrast, no bivariate relationship exists between assembly size and disproportional- ity. Worthy of attention is also that the effective number of parties is somewhat more strongly related to apparentement than the effective threshold. Results of the regression analysis are given in Table 3. As hypothesized, the negative effect on disproportionality and the positive impact on the effective number of parties of assembly size that was found in both the total research population and among systems with single-member districts does not exist in proportional systems when the other variables are controlled for. The impact of the effective threshold is significant with regard to both dependent variables. Surprisingly, there is a significant positive effect of assembly size on the degree of disproportion- ality. Most likely, this is a spurious relationship caused by the Table 2. The effect of assembly size, ballot structure, presidentialism and ethnic heterogeneity on disproportionality and the effective number of parlia- mentary parties in systems with single-member districts, OLS regres- sion. Degree of disproportionality Effective nu mber of parliame ntary parties (Constant) 21.962 9.884*** .957 5.110*** Assembly s ize (log) –2.675 –.201 –2.641** .739 .621 8.629*** Ballot structu re (dummy) –6.258 –.231 –2.959** –.103 –.042 –.573 Presidentialism (dummy) –9.051 –.363 –4.717*** –.778 –.355 –4.880*** Ethnic heterogeneity –3.409 –.088 –1.147 –.557 –.161 –2.225* R-square .261 .337 F-sig. *** *** N 164 166 Note: In each c ell, from to p d ownwar ds , figures indicate the regression coefficient, the standardized regression coefficient and the T-value, ***=sig. < 0.001; Sources: Anckar (2002); Anckar, Erikss on, & Les kinen (2002); Chro ni cle of Parli ament ary Elections; Countries of the World; Inter-Parliamentary Union; Lijphart (1994); Parties and Elections in Europe. Table 3. The effect of assembly size, effective threshold, ballot structure, ap- parentement and presidentialism on disproportionality and the effective number of parliamentary parties in proportional systems, OLS regres- sion. Degree of disproportionality Effective number of parliame ntary parties (Constant) –1.011 –1.234 3.306 5.672*** Assembly size (log) 1.259 .169 3.527*** .394 .084 1.553 Effective t h reshold .307 .558 11.503*** –.065 –.187 –3.438** Ballot structu re (dummy) –.979 –.176 –3.716*** –.154 –.044 –.821 Apparentement (dummy) .229 .035 .714 .976 .234 4.274*** Presidentialism (dummy) .632 .062 1.304 –.608 –.094 –1.764 R-square .327 .149 F-sig. *** *** N 314 315 Note: In each c ell, from to p d ownwar ds , figures indicate the regression coefficient, the standardized regression coefficient and the T-value, ***=sig. < 0.001, **=sig. < 0.01; Sources: Anckar (2002); Chronicle of Parliamentary Elections; Countries o f the World; Inter-Parliamentary Union; Lijphart (1994); Parties and Elections in Europe. interplay of several variables, since, first, assembly size and disproportionality do not correlate, and, second, there is no theoretical explanation of this kind of association. The effective threshold explains most of the variation, whereas apparente- ment is of no significance with regard to the degree of dispro- portionality. Instead, ballot structure influences disproportion- ality among proportional electoral systems. Elections in which the voters have more than one vote produce more proportional results than elections with a categorical ballot. In a sample (not presented in table format) with legislatures that have less than one hundred seats, assembly size has no effect on the degree of disproportionality. Effective threshold and ballot structure are significant at the 0.001-level and the 0.05-level, respectively. The fact that apparentement possesses most explanatory power regarding the effective number of parliamentary parties in the PR sample calls for some further investigation. Seven countries provide the opportunity of combining p arty lists: Finland, Israel, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania and Switzerland. Together they constitute 54 cases. The aver- age effective number of parliamentary parties in this group of countries is 4.86, compared to 3.60 among the remaining 262 cases of proportional elections. The mean effective threshold in the countries with apparentement is 7.25, whereas the other group returns the mean value of 4.39. However, there is a very large difference in district magnitude between the groups, which is not transformed into a similar difference in the effec- tive threshold. The average district magnitude among appar- entement countries is as large as 60.9, compared to 18.3 among elections without the opportunity of combining lists. On the basis of previous research, we know that district magnitude is Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 14  K. LUNDELL Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 15 the single most influential element with regard to electoral sys- tem consequences. These circumstances most likely explain why the explanatory power of apparentement surpasses the effective threshold in this sample. Concluding Remarks In Electoral Systems and Party Systems, Lijphart (1994) ar- gued that the assumed influence of assembly size foremost concerns PR systems, and that a possible effect on dispropor- tionality is less plausible in non-PR systems. The empirical findings here suggest that it is just the opposite. In majoritarian systems, increasing assembly size results in a lower degree of disproportionality and a higher degree of party system frag- mentation. In proportional systems, these tendencies do not exist. The difference between PR and majoritarian systems arises because PR systems consist of elements that are absent or do not vary in systems with single-member districts. PR coun- tries use multi-member districts of varying size, and many of them apply electoral thresholds that restrict the chances of rep- resentation for small parties. In addition, some PR systems provide the opportunity of combining party lists, and some use ordinal ballots. These elements also have some impact on the degree of disproportionality and the effective number of parties. With the exception of ordinal ballots in alternative vote systems, all these elements are absent in countries with single-member districts, and therefore assembly size becomes much more im- portant in majoritarian systems. To be sure, in SMD systems, the size of the legislature is di- rectly related to the number of districts. The chances for small parties to win a seat increase as the number of constituencies increases, particularly if their support is regionally concentrated. Accordingly, on the basis of these results, we might as well conclude that the number of districts is decisive in SMD sys- tems since the number of districts is equal to assembly size. Here, however, focus has been on the influence of assembly size and differences between majoritarian and PR systems in this respect. In proportional electoral systems, ballot structure, apparentement, and, in particular, the effective threshold su- persede assembly size as determinants of the degree of dispro- portionality and the effective number of parties. In electoral systems with single-member districts, by contrast, assembly size remains a significant factor. REFERENCES Anckar, C. (1997). Determinants of disproportionality and wasted votes. Electoral Studies, 16, 501-515. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(97)00038-3 Anckar, C. (1998). Storlek och partisystem: En studie av 77 stater. Ph.D. Thesis, Åbo: Åbo Akademi University. Anckar, C. (2002). Effekter av valsystem: En studie av 80 stater. Stockholm: SNS Förlag. Anckar, C., Eriksson, M., & Leskinen, J. (2002). Measuring ethnic, lingustic and religious fragmentation in the world. Åbo: Åbo Akademi University. Chronicle of parliamentary elections. Several editions. Geneva: In- ter-Parliamentary Union. Colomer, J. M. (2004). The strategy and history of electoral system choice. In J. M. Co lomer (Ed.), Handbook of electoral system choice (pp. 3-80). H ou nd smills and New York: Palgrav e Mac millan. Countries of the World. (2011). URL (last checked 28 October 2011) http://www.theodora.com/wfb/ Cox, G. W. (1997). Making votes count: Strategic coordination in the world’s electoral systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Duverger, M. (1964). Political parties: Their organization and activity in the modern state. London: Methuen. Freedom House (2011). URL (last checked 27 October 2011) http://www.freedomhouse.org Gallagher, M. (1991). Proportionality, disproportionality and electoral systems. Electoral Studies, 1 0 , 33-51. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(91)90004-C Gallagher, M., & Mitchell, P. (Eds.) (2005). The politics of electoral systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Inter-Parliamentary Union (2011). URL (last checked 27 October 2011) http://www.ipu.org/parline-e/parlinesearch.asp Jones, M. P. (1993). The political consequences of electoral laws in Latin America and the Caribbean. Electoral Studies, 12, 59-75. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(93)90006-6 Laakso, M., & Taagepera, R. (1979). “Effective” number of parties: A measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12, 3-27. Lijphart, A. (1990). Size, pluralism, and the Westminster model of democracy: Implications for the Eastern Caribbean In J. Heine (Ed.), A revolution aborted: The lessons of Grenada (pp. 321-340). Pitts- burgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Lijphart, A. (1994). Electoral systems and party systems: A study of twenty-seven democrac ies 1945-1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lijphart, A. (1997). The difficult science of electoral systems: A com- mentary on the critique by Alberto Penadés. Electoral Studies, 16, 73-77. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(96)00058-3 Parties and Elections in Europe (2011). URL (last checked 26 October 2011). http://www.parties-and-elections.de Rae, D. W. (1967). The political consequences of electoral laws. New Haven: Yale University Press. Rae, D. W., & Taylor, M. (1970). The analysis of political cleavages. New Haven: Yale University Press. Sartori, G. (1986). The influence of electoral systems: Faulty laws or faulty method? In B. Grofman, & A. Lijphart (Eds.), Electoral laws and their political consequences (pp. 43-68). New York: Agathon Press. Sartori, G. (1994). Comparative constitutional engineering: An inquiry into structures, incentives and outcomes. Basingstoke: Macmillan. Shugart, M. S., & Carey, J. M. (1992). Presidents and assemblies: Constitutional design and electoral dynamics. New York: Cambridge University Press. Shugart, M. S., & Wattenberg, M. P. (2001). Mixed-member electoral systems: A definition and typology. In M. S. Shugart, & M. P. Wat- tenberg (Eds.), Mixed-member electoral systems: The best of both worlds? (pp. 9-24). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Taagepera, R. (1972). The size of national assemblies. Social Science Research, 1, 385- 401. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(72)90084-1 Taagepera, R. (1973). Seats and votes: A generalization of the cube law of elections. Social Science Research, 2, 257-275. doi:10.1016/0049-089X(73)90003-3 Taagepera, R. (1998a). Effective magnitude and effective threshold. Electoral Studies, 17, 393-404. Taagepera, R. (1998b). Nationwide inclusion and exclusion thresholds of representation. Electoral Studies, 17, 405-417. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(97)00054-1 Taagepera, R. (2002). Nationwide threshold of representation. Electoral Studies, 21, 383-401. doi:10.1016/S0261-3794(00)00045-7 Taagepera, R. (2007). Predicting party sizes. Oxford: Oxford Univer- sity Press. Taagepera, R., & Shugart, M. S. (1989). Seats and votes: The effects and determinants of electoral systems. New Haven: Yale University Press.  K. LUNDELL Appendix Determining the Effective Threshold in Countries with Formal Electoral Thresholds, Adjustment (Compensatory) Seats and Mixed Electoral Systems If the formal electoral threshold is higher than the effective threshold based on average magnitude, the former becomes the actual effective threshold. This is the case in e.g. Israel where the effective threshold would be 0.62 percent without a legal threshold of 2 percent. The use of compensatory seats implies that the final seat al- location is based on the results nationwide; any disproportion- ality at the lower district level is corrected at the upper level. However, it presupposes that the number of compensatory seats, the total number of seats in the legislature, and the districts at the lower level are sufficiently large. In most countries that apply compensatory seats, the upper level determines the effec- tive threshold. A formal threshold is often applied at the upper level; in Norway, for example, a party needs 4 percent of the total vote in order to be entitled to compensatory seats. Since this formal threshold is lower than the effective threshold based on the average magnitude at the lower level, it becomes the actual effective threshold. The same applies to countries such as Sweden, where a legal threshold is present at both the upper and the lower level: the 4 per cent formal threshold at the upper level, which is used for allocating compensatory seats, consti- tutes the effec t ive threshol d . However, in some countries with compensatory seats, parties get more than one shot at qualifying for representation. They may circumvent the legal threshold by winning a sufficient number of seats in the constituencies. Gallagher and Mitchell (2005) discuss the cases of Austria and Denmark and conclude that it is very rare for a party to qualify for the alternative route if they have not also crossed the formal threshold of 4 and 2 percent, respectively. Accordingly, the legal thresholds may well be treated as effective thresholds. Another kind of adjust- ment seats is called additional seats. The allocation of addi- tional seats is not dependent on the results at the lower level and hence does not affect the overall proportionality to any noticeable extent. Therefore the upper level district is added to the lower level districts when the average magnitude and the effective threshold are calculated. This strategy is also used for countries where compensatory seats only partially compensate for the disproportionality at the lower level. There are two kinds of mixed electoral systems: mixed- member proportional (MMP) where any disproportionality in the lower tier is eliminated through seat allocation in the upper tier, and mixed-member ma joritarian (MMM) where there is no link between the tiers. In MMP systems, calculation of the ef- fective threshold is based on the upper tier, usually determined by a legal threshold. However, some MMP countries provide alternative routes to parliamentary representation. In Germany, parties qualify for upper tier seats if they win either 5 percent of the list votes or three single-member districts. In New Zea- land, a party has to be successful in only one single-member district in order to circumvent the 5 percent threshold at the upper level. Again, as in the corresponding cases with adjust- ment seats, Gallagher and Mitchell (2005) come to the conclu- sion that the legal threshold at the upper level represents the national effective threshold. The authors also point out that formal thresholds at the district level in Spain and Belgium do not affect their national effective thresholds (Gallagher & Mitchell, 2005). At a first glance, MMM sy stems could be tre ated similarly as MMP systems; i.e. to let the upper tier determine the effective threshold. However, since there is no link between the tiers, small parties are substantially under-represented in the final seat allocation. Therefore, it is reasonable to take into account the relative weight of both tiers when calculating the effective threshold. In both tiers, the effective threshold is multiplied by the number of seats in the tiers, respectively. These values are added and the sum is divided by the total number of seats. Hungary (as of 1994) and Italy (from 1994 to 2001) have ap- plied MMM systems with partial compensation (Shugart & Wattenberg 2001). In Hungary votes cast for unsuccessful can- didates in the lower tier are added to their parties’ list votes. In the Italian mixed system, the transfer went from party lists to candidates in the single-member districts. The transfer of votes makes it difficult to determine how large a vote share is needed in order to win a seat in each tier. In my analysis, I rely on Gal- lagher and Mitchell’s (2005) estimate of “fair” representation, which in both cases is the legal threshold in the list tier, i.e. 5 percent in Hungary and 4 percent in Italy. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 16

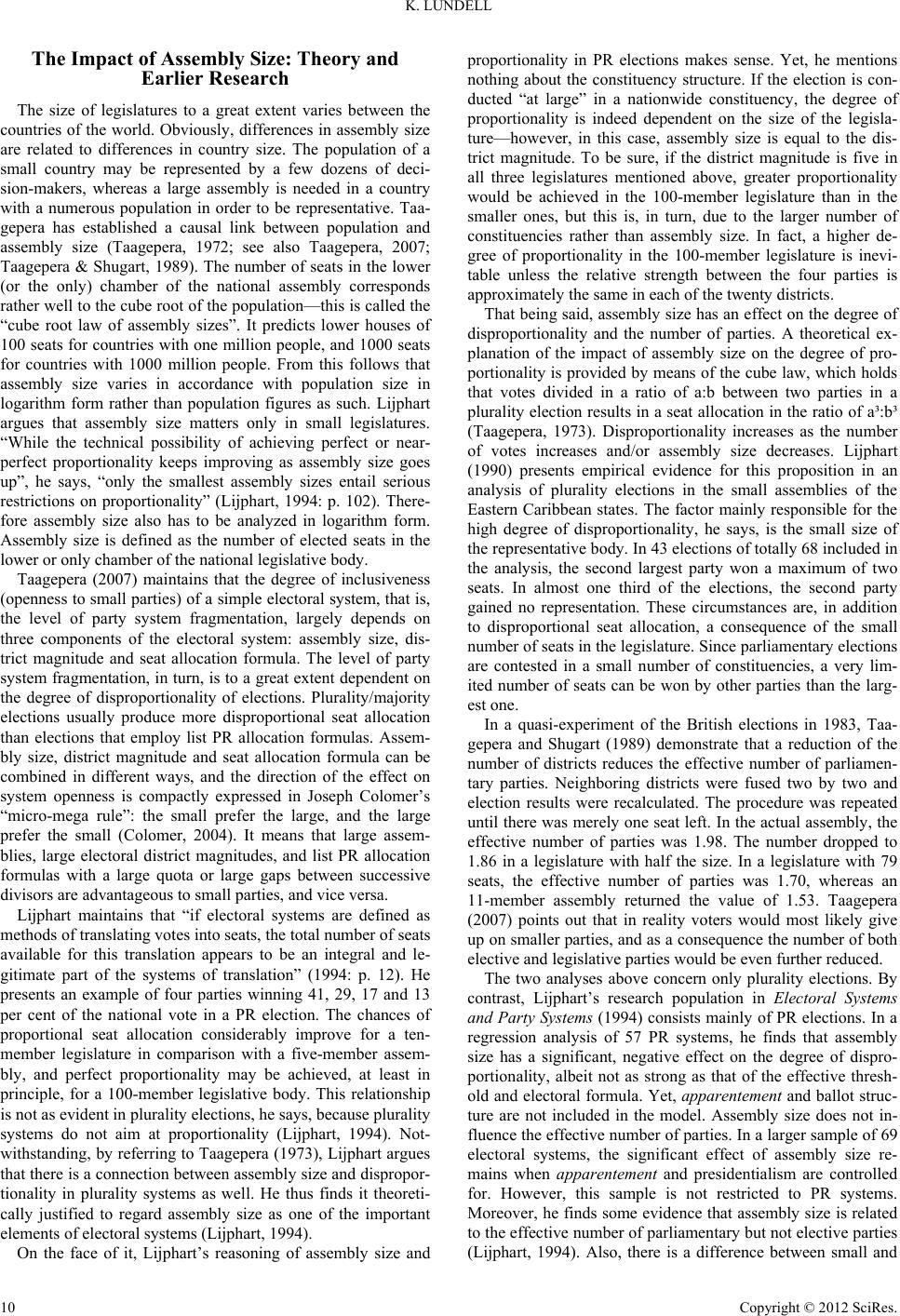

|