Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.2(2013), Article ID:32983,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.32038

Psychological preparation practices for children undergoing medical procedures in Japan and Germany

![]()

1Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health and Welfare, Prefectural University of Hiroshima, Hiroshima, Japan

2Department of Nursing, NRW Catholic University Applied Sciences, Cologn, Germany

Email: matumori@pu-hiroshima.ac.jp

Copyright © 2013 Naomi Matsumori, Michael Isfort. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 18 February 2013; revised 20 March 2013; accepted 15 April 2013

Keywords: Psychological Preparation; Children Undergoing Medical Procedures; Pediatric Nursing; Japan; Germany

ABSTRACT

The present study aimed to clarify the current status and awareness of psychological preparation for children undergoing medical procedures in pediatric nursing in Japan as compared with that in Germany. An original questionnaire about the current status and awareness of psychological preparation for children in hospitals was distributed by mail to nurses’ working on Japanese pediatric wards in 2010. The same questionnaire, translated into German, was distributed to nurses working on German pediatric wards via the internet in 2010. A large majority of respondents strongly agreed that children have a right to informed consent. German nurses expressed a longer-term viewpoint on the effects of preparation than Japanese nurses. Japanese nurses recognized a greater need for improvement in their duties than German nurses. The results suggest that we should consider our own country’s nursing practices and need for improvement, but also learn from studies of other countries to address each culture and medical situation appropriately.

1. INTRODUCTION

Preparation is a means to support the psychological readiness and autonomy of the child undergoing medical treatment. This investigation focused on the respect for children’s rights for preparation as “explaining medical information to a child”. We conducted an investigation to understand the current practice and the spread of preparation since 2002 [1]. Previously, a study was conducted to clarify the status and awareness of psychological preparation for children in child health nursing in Japan in 2005 [2]. The current investigation added new queries to the last questionnaire from 2005 and applied it nationwide to clarify the current status and issues of psychological preparation. In 2010, our university and NRW Catholic University Applied Sciences of Germany entered into an academic agreement. We therefore conducted comparative research with Germany as a representative European country. This study reports the current status and awareness of psychological preparation for children undergoing medical procedures in pediatric nursing in Japan and in Germany.

2. BACKGROUND

Since the 1930s, the need for preparation to reduce psychological aggression among children receiving medical care in Europe and America has been recognized. Psychological preparation started to be introduced into the field of pediatric nursing in Europe and America around 1970. Nursing practices for children reflected the psychological influence of meeting the parents, the disease, and hospitalization. Between 1940 and 1960 preparation programs using a drawing method, a pre-hospital tour, pamphlets or picture books, and puppets were developed [3]. In Japan, a large number of articles or translations regarding psychological responses in hospitalized children have been published since 1970 [4]. Preparation was introduced in the medical setting in Japan by a nursing text and a journal of nursing, triggered by the Convention on the Rights of the Child ratified by Japan in 1994. Initially, preparation was introduced by Kiuchi et al. (1998) as play therapy concerning words to point to the informed consent provided in Sweden. With the support of research grants from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture from 1997 to 1999, Ebina et al. (1997) conducted research in this area, collecting interview and observation data regarding whether children are provided with sufficient information on medical procedures and examinations in the clinical setting. The Japan Nursing Association (2002) advocated for a standard of child health nursing duties requiring that nurses explain medical examinations, conditions, and treatments using plain words and pictures appropriate for a child’s development and understanding [5].

We previously reported a case study of psychological preparation undertaken by a nurse using a Kiwanis doll and a wooden model of the medical procedure for a 4- year-old girl scheduled to undergo surgery for vesicoureteral reflux [6]. Another study was conducted to clarify the status and awareness of psychological preparation for children in child health nursing in Japan. An original questionnaire was distributed to 350 nurses working on pediatric wards in Japan in 2005. Most aspects of psychological preparation for children in hospital were “always” provided by 35.2% and provided “depending on the status” by 64.6% of the respondents. The responses covered various ways of psychological preparation for various medical procedures (e.g., medical procedures, 83%; preoperational examinations, 45%; physical examinations, 37%; and nursing care, 36%) [2].

Japan and Germany share a number of similarities. Germany is a member of the European Union and one of the members of the European Association for Children in Hospitals. It has a population of approximately 82 million people. The average number of births per woman in Germany is 1.4% and 26% of the population are over 60 [7]. Germany was the first country with a low birthrate and high aging rate to establish a nursing care insurance system based on the social insurance method. The medical welfare system in Germany can be used as an example for the medical welfare systems of other countries, including Japan. German nurses are trained in schools mostly located within hospitals, and nurses can specialize as general nurses, pediatric nurses, or geriatric nurses [8]. As of 2000, Germany had 25 institutes offering bachelor degrees in nursing education [9]. German nursing students receive common education necessary for nursing in the first year and receive specialized curricula after the second year [10].

Japan has a population of 127 million people; the average number of births per woman is 1.4% and 30% of the population are over 60 [11]. However, unlike Germany, the Japanese nursing education system only provides a general nursing qualification. In 2000, Japan already had nearly 80 institutes offering bachelor of nursing degrees; as of 2012, that number has increased to 200.

As of 2010, Germany had a higher number of doctors per thousand capita (3.7) than Japan (2.2). The numbers are more similar when looking only at nurses; there were 11.3 nurses per thousand capita in Germany and 10.1 in Japan. Germany currently has a higher number of doctors and nurses per capita than Japan [12]. The current project compared psychological preparation for children in child health nursing in Germany and Japan.

3. METHODS AND PARTICIPNANTS

An original questionnaire about the current status and consciousness of psychological preparation for children in hospitals was distributed by mail to nurses working on Japanese pediatric wards between October and December 2010. The same questionnaire, translated into German, was distributed to nurses working on German pediatric wards via the internet between September and October 2010. The recruiting took place in Germany through a press release and information from an internal e-maildispatcher [13]. A total of 2168 Japanese questionnaires and 335 German questionnaires were distributed.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire was designed specifically for the present study. It was based upon topics identified in our past study of Japanese nursing in 2005 [2]. The contents of the questionnaire were divided to address the following issues:

• Background information about participants;

• Who is most responsible for providing psychological preparation to parents or children;

• Necessity of providing psychological preparation to children before examinations, procedures, and operations;

• Reasons why psychological preparation is provided or not provided to children;

• Best strategy to promote psychological preparation in nursing.

3.2. Data Analysis

The digital data were tallied using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office Professional 2010). Chi-square tests were performed with SPSS statistical analysis software (IBM SPSS Statistics Ver.19). Numerical values were rounded to the nearest hundredth for analysis.

3.3. Reliability and International Validity

The Japanese side led the investigation, but the questionnaire, based on the Japanese study conducted in 2005, was finalized by through multiple discussions with Prof. Michael Isfort [13].

3.4. Ethical Considerations

A letter of invitation outlining the research aims and providing further details of the study accompanied each questionnaire. Participants were informed that their anonymity would be protected and that participation was voluntary. Questionnaires did not contain any personal information that could identify respondents.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Participants

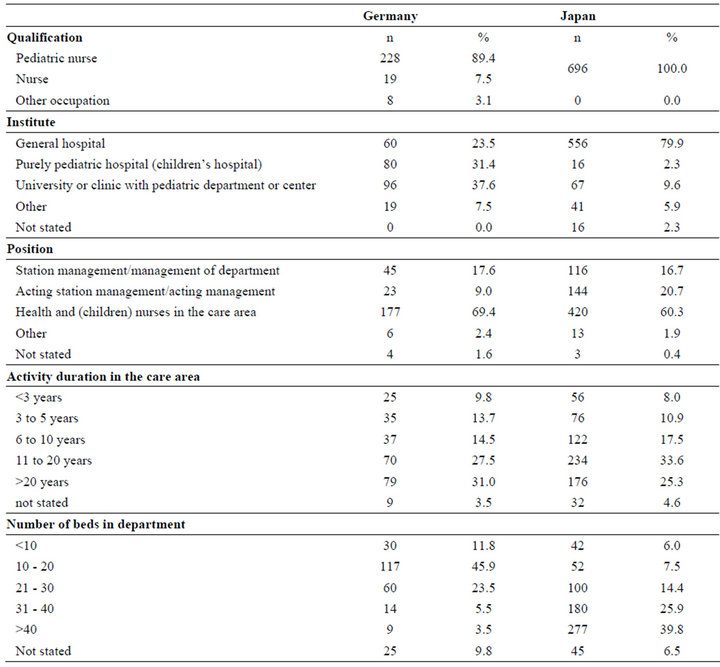

A total of 696 Japanese questionnaires (response rate, 32.1%) and 255 German questionnaires (response rate, 76.1%) were returned (Table 1).

4.2. Responses to Questions

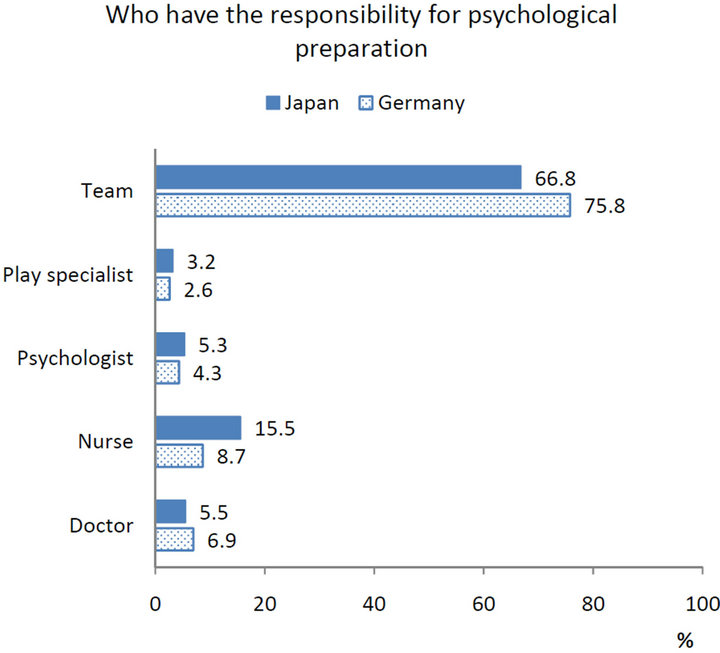

A higher proportion of Japanese respondents (58.6%) answered that psychological preparation is “always necessary” for children in hospitals; only 29.6% of respondents from Germany agreed (p < 0.01). German respondents answered that it was the responsibility of the entire team nearly 10% more often than Japanese respondents. Conversely, more Japanese than German respondents answered that nurses had the primary responsibility (Figure 1).

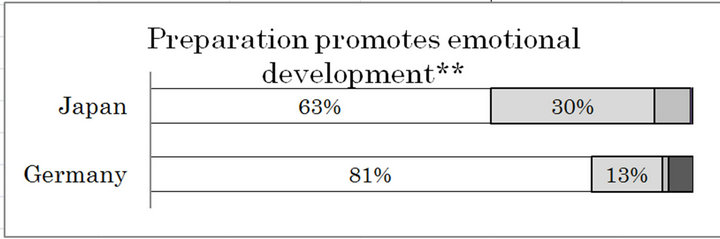

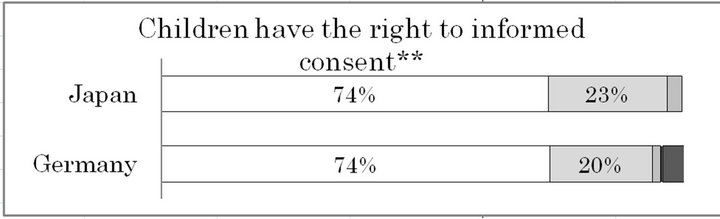

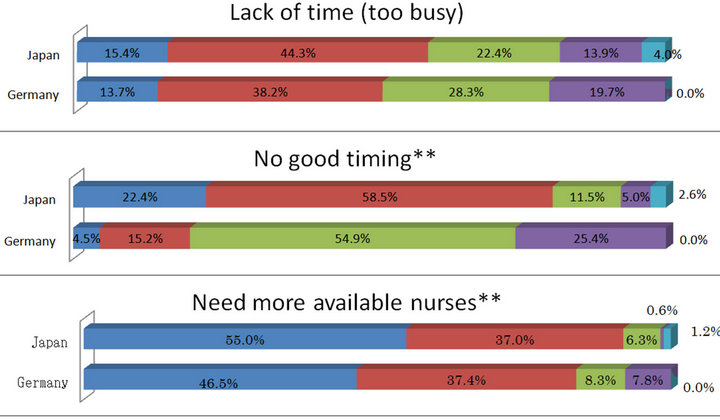

A large majority of all respondents strongly agreed that children’s right to informed consent was a valid reason to conduct psychological preparation. German respondents tended to agree more than Japanese respondents that preparation was important for the promotion of emotional development and for improvement of nursing quality (Figure 2). As explanations for why preparation is not currently conducted, Japanese respondents tended to agree more than the German respondents that there was never a good time, that the number of nurses needed to be increased, that it is better to explain to parents than children, and that children become anxious when presented with medical information. However Japanese respondents does not tended to agree much more than Germans that preparation is not a nursing duty (Figure 3).

Table 1. Background of participants in Germany and Japan.

Figure 1. Recognition of psychological preparation for children in hospital.

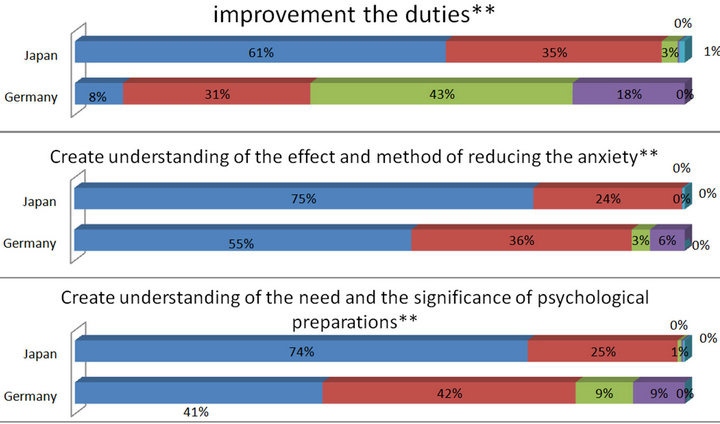

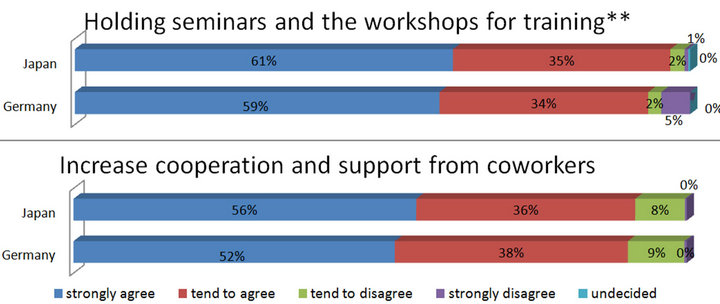

Finally, we asked respondents to tell us what they believed was the best strategy to promote psychological preparation in nursing. Japanese respondents agreed more strongly than German respondents that improvement of duties, understanding the effects and methods of reducing anxiety, and understanding the need and significance of psychological preparations were all necessary strategies. Over 90% of all respondents agreed, 60% strongly, that it was important to hold seminars and workshops about psychological preparation (Figure 4).

5. DISCUSSION

A large majority of each country’s respondents strongly agreed that children have a right to informed consent. This result means that each nation’s clinical settings

Figure 2. Reasons why preparation is conducted (**p < 0.01).

were influenced by the Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by Japan in 1994 and by Germany in 1992. The present results indicate that the necessity of psychological preparation for children in hospitals was recognized more strongly in Japan than in Germany. In 2005, the proportion of Japanese respondents who answered that psychological preparation is “always necessary” for children in hospitals was 35.2% and 64.4% of respondents said it was “dependent on the child’s status” [14]. The Japan Nursing Association (2002) advocated for the standard of child health nursing duties that the nurses need to explain conditions, treatment, and medical examinations for children, using plain words and pictures appropriate for the child’s development and level of understanding. After 2002, the number of the documents about preparation in the pediatric nursing area suddenly increased. Therefore, recognition by nurses of the necessity of psychological preparation for children in hospitals changed over five years by the nursing movement in Japan. Each nurse explored autonomy and decision making in nursing depending on medical and political history; recognition of these factors can be an indicator of self-direction in nursing [15]. Compared to Japanese respondents, German respondents strongly agreed that psychological preparation was

Figure 3. Reasons why preparation is not conducted (**p < 0.01).

necessary for the promotion of emotional development and improvement of nursing quality. German nurses expressed a longer-term viewpoint on the effects of preparation than Japanese nurses. Japanese respondents tended to agree more with reasons not to conduct preparation, such as that there was never a good time, that it was better to discuss the topic with parents, or that children become anxious when presented with medical information. Tork et al. (2007) reported that a higher dependence of children in their daily tasks undoubtedly places a greater burden on nurses in clinical settings. In Germany, children attend nurseries earlier and are then trained to attend to their needs to help themselves gain independence in all aspects of self-care. It has been reported that German children have lower care dependency than Egyptian children [16]. It seems important in nursing practice to assess the care dependence of children in respect to their developmental stage in order to maximize their self-care abilities while gaining a better understanding of the actual inter-

Figure 4. Best strategy to promote psychological preparation in nursing (**p < 0.01).

cultural differences [17].

Additionally, Japanese nurses recognized that improvement of duties, understanding the effects and methods of reducing anxiety, and understanding the need and significance of psychological preparations were necessary. Japanese nurses need more understanding about children’s potential competence and the real significance of preparation for protecting children’s rights than German nurses. These results indicate that concepts such as the reduction of handling for children and nursing measures for infants are realized to some extent in Germany, because German nurses are specialized in pediatric nursing. Additionally, Japanese nurses may be busier than German nurses, as Japan has more beds in the pediatric department and fewer pure pediatric hospitals than Germany. Japan also has fewer nurses per capita than Germany. Therefore, Japanese nurses may require more specialized training for pediatric nursing depending.

The results of this study are limited by the interpretation and meaning of the items on the questionnaire; each country’s results were produced by researchers in their own languages and with their own method. Each country has a different medical history and welfare system and a different nursing education curriculum. Future studies should aim to further clarify these findings by comparing the results of qualitative research on the medical cultures and welfare systems of Germany and Japan.

6. CONCLUSION

The present results indicate that the necessity of psychological preparation for children in hospitals was recognized more strongly in Japan than in Germany. A large majority of each country’s respondents strongly agreed regarding children’s right to informed consent. However, Japanese nurses were recognized as busier than German nurses because Japan has a greater number of beds in pediatric departments and a lower number of nurses per capita than Germany. The present results suggest that we should consider our own country’s nursing practices and need for improvement, but also learn from studies of other countries to address each culture and medical situation appropriately.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Professor Hiromitsu Mihara, and Professor Ansugar Meates, who helped with data collection and study design.

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research in Japan 2010.

REFERENCES

- Matsumori, N., Ninomiya, K., Ebina, M., Katada, N., Katuda, H., et al. (2006) Practical application and evaluation of a care model for informing and reassuring children undergoing medical examinations and/or procedures (part 2): Methods of relating and practical nursing techniques that best bring out the potential of children. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 3, 51-64. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2006.00052.x

- Matsumori, N. (2009) Child health nursing issues regarding psychological preparation practices for children undergoing medical procedures in Japan. Program & Abstracts of the 1st International Nursing Research Conference of World Academy of Nursing Science, 19-20 September 2009, 20.

- Bar-Mor, G. (1997) Preparation of children for surgery and invasive procedures: Milestones on the way to success. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2, 252-255. doi:10.1016/S0882-5963(97)80010-3

- Oikawa, I. (2002) Preparation; ways and devices, why is preparation required? Japanese Journal of Child Nursing, 25, 189-192.

- Matsumori, N., Ninomiya, K., Ebina, M., Katada, N., Katuda, H. et al. (2006) Practical application and evaluation of a care model for informing and reassuring children undergoing medical examinations and/or procedures (part 2): Methods of relating and practical nursing techniques that best bring out the potential of children. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 3, 51-64. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7924.2006.00052.x

- Matsumori, N. and Kamoshita, K. (2006b) A study of practice and expansion of preparation for children undergoing surgery: Using a Kiwanis doll and wooden model of the medical procedure. Humanity and Science Journal of Faculty of Health and Welfare, 6, 71-82.

- World Health Organization (2011) Country statistics. Global health observatory data repository. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.country.9200

- Löffler, H., Bruckner, T., Diepgen, T. and Effendy, I. (2006) Primary prevention in health care employees: A prospective intervention study with a 3-year training period. Contact Dermatitis, 54, 202-209.

- Hackmann, M. (2000) Development of nursing research in Germany in the European context. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 6, 222-228.

- Hozumi, Y. (2009) Elderly care training education and the training system for teachers of elderly care in Germany. Kawasaki Medical Welfare Journal, 18, 337-346.

- World Health Organization (2011) Country statistics. Global health observatory data repository. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-JPN?lang=en

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2012) OECD health data: Health care resources. OECD health statistics (database).

- Isfort, M., Matsumori, N. and Brüheet, R. (2011) Die reduzierung von ängsten von kindern vor untersuchungen und operationen (Germany). Kinderkrankenschwester, 30, 378-386.

- Matsumori, N. (2011) The states and issues of the psychological preparations for children and parents receiving medical treatment (Japanese). Proceedings of the 31st Academic Conference of the Japan Academy of Nursing, Kochi, 2-3 December 2011, 512.

- Hackmann, M. (2000) Development of nursing research in Germany in the European context. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 6, 222-228.

- Tork, H., Lohrmann, C. and Dassen, T. (2007) Care dependency among school-aged children: Literature review. Nursing & Health Sciences, 9, 142-149.

- Tork, H., Dassen, T. and Lohrmann, C. (2009) Care dependency of hospitalized children: Testing the care dependency scale for paediatrics in a cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 435-442.