Psychology 2012. Vol.3, No.2, 143-149 Published Online February 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/psych) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.32022 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 143 The Impact of Stress, Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Coping on University Students, a Multicultural European Study Dimitrios G. Lyrakos Maastricht University, NL Elpis Care, Athens, Greece Email: info@lyrakos.gr Received November 29th, 2011; revised January 10th, 2012; accepted January 14th, 2012 The present study is a follow up study of 562 university students during a 12 month period, at universities from the UK, France, Germany, Austria, Spain, Italy, and Greece. The purpose of the study is to examine the impact of stress, social support and self-esteem on university students. To our knowledge, it is one of the very few, if not the only study, that examines those particular variables in a multicultural sample. The students completed at the beginning of the 12 month period a self reported scale about stress (the Daily Hassles questionnaire), self-esteem, and social support. During the second time the participants have also completed sections about University Satisfaction, and Coping Styles of Stress. The statistical analysis af- terwards has shown that the levels of stress have been significantly reduced after the passing of the 12 month period (p < .001), as it was hypothesised. On the other hand Social Support has been significantly reduced during the passing year (p = .049), which confirmed the Null-Hypothesis. Furthermore the re- search has shown that the levels of stress are negatively correlated with the positive ways of coping, the levels of social support, self-esteem and university satisfaction. On the other hand the levels of stress are positive correlated with the negative ways of coping, all above correlation have been proven to be sig- nificant (p < .005). Finally the country of studies has shown some differences in the levels of stress and in the rest of the variables of interest, particularly between the UK students and the rest of the other coun- tries. Keywords: Stress; Social Support; Self-Esteem; University Students; Europe; Multicultural Introduction Studying abroad causes more stress situations in students than in students studying in their home country, because every nation has its own language, traditions, customs and ways of thinking and sometimes it is really difficult or even impossible for a foreign student to adjust to all changes and differences, which he or she faces in university. It often takes a lot of time, trying and efforts to cope with new life in an educational estab- lishment. And young people are especially vulnerable in their perception of new people and environment. When they first enter the university they cannot escape the influence of the university special traditions and customs, its usual things, its flow of the time (Brewing et al., 1989). Everything is new for students in universities: their fellows, teachers, staff and even environment that surround them. This fact is either met as a challenge that they need to accept and overcome, or as a problem that is a cause of great stress. That does not only apply to students from abroad, but also to those students who study in their own country and choose to go to a university a long way from their hometown. They think going to a university is a time to be independent, and to live away from home and develop new interests (Fisher et al., 1988). But in reality these university students also feel great stress during their sessions and they need help in finding coping strategies for stress situation. All above-mentioned variables are closely connected with each other and exist in the life of every university student, de- spite their gender, age or race (Wolf et al., 1987). Students always think that their problems are especially serious. There are triggers or stressors that can affect student stress levels as nothing else. Major life changes, such as going to, and then leaving university, are the greatest contributors of stress for students regardless of gender. So they place the greatest demand on resources for coping (Ross, 1999). The Definition of Stress There are a number of different definitions for stress. Based on Long, stress is a relationship between the person and the environ- ment that is considered by the person as something that surpasses his/her capabilities and resources and is endangering his/her well- being. Stress is a person’s physical and psychological reaction to a perceive d or act ua l de ma nd f o r cha n ge. The de ma nd i t self i s cal le d a stressor and the steps pe ople take to resolve or avoi d the stressor are referred to as coping (Long, 1998). As the university student should adjust to changing situations and life in whole, the greater the stress, which is acquired. Stress is a combination of factors that affect each individual differently. In other words, what is stressful to one person may not be so to another, and reactions to stressors vary among dif- ferent groups of individuals and even among sisters and broth- ers. This is especially seen among university students, they are young and their behaviour and actions are so inconsistent that some of them do not feel stresses at all, while others can be in stressful state almost all the time. Different reasons influence them, including family relations, friendship, financial state, way of life, etc. (Odgen et al., 1997).  D. G. LYRAKOS Two Kinds of Stress Response There are two kinds of stress response: appraisal and coping. Appraisal refers to the responses a student has to everyday situations. Those situations create a number of thoughts. These thoughts fuel a student’s emotions (fear, sadness, happiness, anger, etc.), so if the thoughts are negative, the emotions will be, too. Neutral thoughts are less likely to provoke a stress re- sponse (Clark et al., 1990a; Clark et al., 1990b). Coping refers to the way a person responds to his appraisal. If his appraisal tends to arouse his nervous system, his coping will be affected, sometimes negatively. If he chooses a coping behaviour that’s not appropriate to the situation, running away from conflict with his roommate, or denying that he is not pre- pared for a test for example, he will ultimately add to his stress. Examples of coping responses include denial, discounting, blaming himself or others, distraction, social strategies. In general, action-based coping strategies, for example exercise emotion-based strategies; distraction and social strategies, such as support from friends, family etc. are good coping skills to have (Steptoe, 1996b; Weidn er et al., 1996; Van Golder et al., 1999). Apart from the direct active coping strategies there are also the indirect active coping strategies, that university students can adopt in an attempt to reduce their stress by releasing it or en- gaging in activities known to reduce stress. Those strategies do not, however, attempt to change the source of the stress (Clark et al., 1990a; Cosden et al., 1997). Self-Efficacy Stress and its effects on an individual’s self perceptions have received substantial empirical attention. Macan (1983), found that students, who experience high levels of self-efficacy can cope better with stress. Furthermore it is argued that their levels of stress are significantly lower compared with students, whose level of self-efficacy was low. These findings are consistent with the idea that the more stress a student experiences, the less satisfied they would be with other areas of their life (Brown, 1996; Steel et al., 1993). The relationship between the person and environment in stress perception and reaction is especially magnified in univer- sity students (Brewing, 1989). The problems and situations encountered by university students may differ from those faced by their non-student peers. The environment in which univer- sity students live is quite different. While jobs outside of the university setting involve their own sources of stress, such as evaluation by superiors and striving for goals, the continuous evaluation that university students are subjected to, such as weekly tests and papers, is one that is not often seen members and time pressures may also be sources of stress. Relationships with family and friends, eating and sleeping habits and loneli- ness may also affect some students adversely (Schwarzer, 1999). Social Support Social support has been found to be associated with greater well being in a wide variety of studies (Stepoe et al., 1996). Cohen and Wills suggest that considering data from animal and from human prospective and analogue studies together, social support may have crucial role. They discuss two models, one hypothesising a direct beneficial effect of social support and the other that social support buffers the adverse effects of stressful events. Both models are supported by available data. While social support is a complex, there is agreement that both quan- tity and quality of social support be assessed and a number of measures have been developed (Bages et al., 1997). Cohen and Wills concluded that the direct main effect of social support is found when qualitative measures are used and a buffering effect when qualitative measures are used. Thus social integration, which is a quantitative measure, may be associated with better psychological and physical well being whereas having available support that will enhance coping a qualitative measure, may result in a stress buffering effect of social support. Present Study The purpose of this work is to examine the correlation-in- teraction between stress, coping strategies, in the lives of uni- versity students, who are studying in their home country as well as abroad. Specifically, possible correlations are expected to be found between the coping strategies and the levels of stress. Furthermore it is also argued that factors such as social support, self-efficacy and university satisfaction will have a significant negative impact to the levels of stress. In order to have more support our findings, it has been decided that it is going to be a between subjects design, meaning that the same participants are going to complete the questionnaire twice within a period one year. It is argued that the levels of stress will be significant lower during the second examination. The hypotheses are: Stress the second time the participants will be examined will be lower in comparison to the first time. Social support will be less the first time will be significantly less in comparison to the second time. Stress will be negative correlated with 1) social support, 2) self-efficacy, 3) university satisfaction, 4) problem focus coping, 5) tension reduction coping, 6) social support coping. Stress will be positive correlated with 1) accommodation coping, 2) avoidance coping and 3) devaluation coping. There are gong to be significant differences between the students of the different countries. Methodology Participants The participants in this project are university students from British (English (111, 19.7%), Irish (28, 5%) and Scottish (23, 4.1%)), German (108, 19.2%), Italian (53, 9.4%), Spanish (58, 10.3%), France (50, 8.9%), Austrian (33, 5.9%) and Greek (98, 17.4%) universities. They were both male (278, 49.4%) and female (285, 50.6%), with the majority of the sample been, between the ages of 21 and 25 (58.5%). The youngest partici- pant of the study was 19 and the oldest 58 years. All partici- pants were asked to complete the questionnaire twice within 12 months (one year). The participants are from various fields and years of studies, nationality and ages. The first exclusion factor was that they could not being their final year during the first examination, because probably they would not be students during the second study and conse- quently would not fill the criteria for participating. The second exclusion factor was that the participants should be natives on the area where the university was in order to control possible problems with adjustment in a new city or even country. The participa nts were randomly selected from the university cafete- Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 144  D. G. LYRAKOS ria, dinner and the common rooms. Procedure The questionnaires in the countries outside the UK have been sent by mail or email to some psychology students together with a letter of instructions about the participants, who are needed for the completion of this research. The section in the instructions about the participants was the same with the sec- tion about the participants above. Furthermore it is going to emphasized the fact that the participants will have to come willingly to complete the questionnaire. The participants were found in the lecture theatres of the university, or in the coffee shops within the university. 12 months after the first comple- tion of the questionnaire the participants were contacted again in order to complete the same questionnaire again for the sec- ond time, during a period of high demands from the students, such as examination period. Questionnaire The questionnaire is separated in 5 different sections. Demographics In this section of the questionnaire information about the age, gender marital status will be obtained. Daily Hassles Schafer and his students created the Daily Hassles question- naire in order to measure anxiety in college students, based on the study of Lazarus in 1981 about their harmful effects. Ac- cording to Kenner (1991) “these micro-stressors are the irri- tating, frustrating, distressing demands that, to some degree, characterize everyday transactions with the environment”. Coping in General Life The resultant checklist is a 24 items scale. Respondents are requested to rate coping techniques they generally use in stre ssful situations. The CCS includes items related to six factors, changing the situation (problem-focus), accommodation, devalua- tion, avoidance, social support coping and symptom reduction. Self Esteem It has been generally accepted that the way in which people view and value themselves influences their perception of diffi- cult events around them. A measure of self esteem was thus included, using Rosenberg’s Self Esteem Scale. He described self esteem as “self-acceptance or a basic feeling of self worth”. Social Support The social support questionnaire by Sarason in 1983 was chosen to measure the participant’s social networks, work, fam- ily and friends. The shorten version was used since it was con- sidered important to reduce the size of each questionnaire be- cause of the great number that were used. University Satisfaction This questionnaire is consisted by 17 questions such as “How satisfied are you with the variety of your subjects?” This sec- tion is also a self-reported seven-item scale, with 1 being “ex- tremely dissatisfied” and 7 being “extremely satisfied”. Statistical Analysis For the purpose of this study there were conducted a number of statistical analyses to test the experimental hypotheses. The most important of the tests conducted here are a reliability analysis for the questionnaires, one-way ANOVA, Paired Sam- ple T-test, and Correlation. The software used for the statistical analysis was the SPSS 14.0. Results Reliability Analysis and Correlations From all the reliability analyses presented in the correlation matrix (Table 1), it can be seen that all the self reported scale questionnaires, used in the prese nt study, are valid to conduct the test for the hypotheses mentioned in the beginning of this section. Based on Table 1 it can be seen that stress is positively cor- related with accommodation coping (p-value < .001), devalua- tion coping (p-value < .001) and avoidance coping (p-value < .001). Furthermore stress is negatively correlated with self-esteem (p-value < .001), university satisfaction (p-value < .001), problem focused coping (p-value < .001), tension re- duction coping (p-value < .001), coping social support (p-value < .001) and social support (p-value < .001). Mean Differences In order to compare stress with social support, self-esteem, university satisfaction, extraversion and all the factors of the coping styles, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. The tables and plots produced by the test are presented below. From Table 2 for the one-way ANOVA presented, it can be safely concluded that there is a strongly significant difference in the means between stress and university satisfaction (p < .001), social support (p < .001), problem focused (p < .001), accommodation coping (p < .001), devaluation coping (p < .001), avoidance coping (p < .001), tension reduction coping (p < .001), social support (p < .001) and self-esteem (p < .001). It has also been argued that there is going to be significant difference between stress, social support, university satisfaction, self-esteem, the different factors of coping strategies, se lf-e steem , in relation with the country of origin. To support this hypothe- sis a one-way ANOVA has been conducted and it is presented below (Table 3). From the table produced it can be concluded that there is a significant mean difference between the country of origin and university satisfaction (p < .001), social support ( < .001), problem focused (p < .001), devaluation (p < .001), avoidance (p < .001), tension reduction (p < .001), cope social support (p < .001) and self-esteem (p < .001). There is only one difference, which does not have any sig- nificance. This is between the country of origin and the ac- commodation coping with a p-value of .736 which is much higher than .05. Comparison of Stress and Social Support between the First and Second Study The next test conducted is to determine if the level of stress Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 145  D. G. LYRAKOS Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 146 Table 1. Correlation coefficients , and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each of the scales used (*p < .05; **p < .001). Correlation Matrix CHOMER BSELF BHASSLE alpha CHOMER - BSELF .3904* .9333 BHASSLE –.4063** –.6406** .9632 UNSAT .2626* .5291* –.8047** COPFIX .2728* .5299** –.7727** COPACC .0399** –.1044** .5711* COPDEVAL –.3044** –.4826** .8168** COPAVOID –.3292** –.4937** .7911** COPTENRE .4230** .7586* –.6895* COPSOCSU .4122** .6846** –.5789** SOCSUB .3664** .6395** –.8374* UNSAT COPFIX COPACC COPDEVAL COPAVOID alpha UNSAT .9817 COPFIX .7420** .9334 COPACC –.5406** –.4171* .8277 COPDEVAL –.7688* –.7087** .6829* .8809 COPAVOID –.7179* –.6946** .5875** .9209** .9183 COPTENRE .5417* .7099** –.1235** –.5410* –.5790** COPSOCSU .5063** .6954* –.0270* –.4650* –.5067** SOCSUB .8150* .6698** –.3905** –.7101** –.6614* COPTENRE COPSOCSU SOCSUB alpha COPTENRE .9172 COPSOCSU .9277** .9057 SOCSUB .5746** .5040** .9713 Table 2. Dependant variable: seco n d score of daily hassle s. Variables N Df Sum of Square F Significance University Sa ti sfaction 562 56 174457.7 64.127 .000 Social Support B 562 56 27768.246 51.316 .000 Coping Problem Focused 562 56 7735.196 85.658 .000 Coping Acc ommodation 562 56 5236.209 48.637 .00 Coping Devaluation 562 56 6347.838 55.652 .000 Coping Avoidance 562 56 6741.091 46.377 .000 Coping Tensi on Reduction 562 56 6728.333 48.999 .000 Coping Soc i a l Support 562 56 6725.563 35.606 .000 Self-Esteem 562 56 17262.359 35.001 .000  D. G. LYRAKOS the second time is significant less in comparison to the first time. In order to determine that, a paired t-test has been con- ducted. From the Table 4 it can be seen that with a p-value less than .001, the levels of stress that the students present during the second examination is significant less (–10.491) in com- parison to the levels of the first examination. From Table 5 it can be seen that the social support, surpris- ingly, is higher the first time in comparison to the second time and this is barely significant with a p-value of .048, which is just less than .05. Discussion The present study is one of the few in the field that examines in a cross cultural way the impact on university students of some everyday factors that affect our lives, such as stress, so- cial support and self esteem. The findings on the present study, indeed show an effect on the students by those variables. Fur- thermore it is also presented a difference between the different countries. Explanation about the Levels of Stress A main interest is that the levels of stress in the students-par- ticipants during the second study have shown significant reduc- tion in comparison to the first time. That is accordingly to the literature about this subject (Goldman et al., 1997; Fisher et al., 1989; Nagquin et al., 1996; Goldberber et al., 1993). On the other hand it has been proven that the levels of stress even dur- ing the second part of the study, are significantly higher in the UK students in comparison to the rest of the European coun- tries tested. A definite answer about the actual reason of this phenomenon is quite difficult to be determined mainly because there have not been many researches comparing students from so many different countries and academic systems. One hy- pothesis could be that the academic system in the UK is sig- nificantly more difficult and for that reason more stressful in comparison to the rest of the European countries. Unfortunately though no direct comparison has been conducted between the academic systems and that makes this probability difficult to confirm or reject. Another reason could be the financial factor. There were a number of articles in the Guardian written by academics from various institutions around the UK, who were arguing that because of the tuition fees the performance of many students have been significantly reduced. (http://www.guardian.co.uk). Whether though is a single factor or a combination of factors it is difficult to establish in the pre- sent study, since there was not one of the experimental hy- potheses of the study. Whatever the reason though these great Table 3. Dependant variable: country of origin. Variables N Df Sum of Square F Significance University Sa ti sfaction 562 6 36355.064 20.708 .000 Social Support B 562 6 9214.380 36.423 .000 Coping Problem Focused 562 6 1518.139 20.003 .000 Coping Acc ommodation 562 6 39.454 .593 .736 Coping Devaluation 562 6 1398.915 21.679 .000 Coping Avoidance 562 6 1843.159 27.498 .000 Coping Tensi on Reduction 562 6 3465.522 71.308 .000 Coping Soc i a l Support 562 6 8352.404 56.569 .000 Self-Esteem 562 6 1392.067 57.840 .000 Table 4. Paired t-test between the two sums of the daily hassles questionnaire. Variables N SD Mean T df Significant (2-Tailed) Second Score of Daily Hassles (BHassle) 563 21.91 54.00 - First Score of Daily Hassles ( AHa ssle) 563 12.71 64.38 - BHassle-AHassle 563 23.46 –10.37 –10.491 562 .000 Table 5. Paired T-test between th e two sums of the social support q u e s tionnaire. Variables N SD Mean T df Significant (2-Tailed) Second Score of Socia l S upport (SocSuB) 563 7.62 27.74 - First Scor e of Social Su p port (SocSuA) 563 7.25 28.56 - SocSuB-SocSuA 563 9.77 –82 –1.984 562 .048 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 147  D. G. LYRAKOS differences in the levels of the stress between the UK students and the rest of the European University students are very dis- turbing (Naquin et al., 1996; Barlett, 1998). Social Support Another result of great interest is that the levels of social support during the second study have been reduced in com- parison to the first study. Although this difference is barely significant, nevertheless it raises a number of interesting ques- tions. It is argued from the literature that the levels of social support increase with time (Ross et al., 1999; Saranson et al., 1999; Steer et al., 1995), but at the present study they have fallen. It is difficult to explain the reason of why that happened. One possibility could be that since the students are advancing in the academic years at the university they have more work and there are greater the demands from them, that could have as a result in the unwilling reduction of the social interaction (Cos- den et al., 1997), and in particular the reduction of the social support satisfaction. Another, more simplistic reason, could be that many members of the social environment of the partici- pants were transferred at another university, they just finished their degree and went away, or they just stopped for various reasons contact with a number of persons (Steel et al., 1993; Steer et al., 1995). Negative Correlations The third hypothesis was sepa rated in seven subcategories. It is argued from the literature that stress will be negatively cor- related with social support (Watson et al., 1998), which was strongly confirmed by the analysis. This indicates that social support is a significant factor for the coping reduction of stress. The same argument is also strong for self-efficacy (Watson et al ., 1984; Wiebe, 1991), and the positives ways of coping. This proves that there are many factors that can influence the amount of stress not only in the students but also in humans in general (King et al., 1991; Parkes et al., 1990). Positive Co rr elations On the other hand it has been proven very strongly by the correlation table presented in the results that neuroticism and the negative affectivity ways of coping, accommodation coping, avoidance coping, and devaluation coping, can increase the levels of stress. These findings also support the results from (Long, 1998; Rapolow et al., 1987; Ronan et al., 1994). Differences between the Countries About the last hypothesis it has been proven that there are significant differences between the different countries. As it was mentioned in the beginning of this section, the biggest difference is between the UK and the rest European students. It can be seen from the plots presented in the results that the UK students, scored significant higher on stress than the rest of the participants and in general they scored worse than any other group of students. That comes in agreement partly with the research of Tony Towel at the Westminster University in 1999, but on the other hand the extend of this difference seems to be higher in the present study in comparison to that at the West- minster University research. Since the literature is very limited regarding comparisons between university students from dif- ferent countries there cannot be identified any definite reason explaining this phenomenon. One possibility could be that the demands for a UK student are higher in comparison to the rest of the E.U. universities that could explain the high levels of stress and the low social support. Additionally the infectivity of the coping strategies could be another important factor. It is possible that UK students have no effective means of coping, which could explain these radical differences (European Coun- cil of Education, 2001). Another reason for these differences between the countries could be the financial problems caused because of the tuition fees. There have been reports (The Guardian), that percent of part-time or even full-time jobs ever since the first year that the tuition fees had been established were increased significantly. High levels of stress may also result not from the students current academic studying, but from growing up in a stressful family environment. Parents usually lay unrealistic expectations for the student and this leads to a heightened state of anxiety. And this is not the end of the list. REFERENCES Bages, N., & Falger, P. R. J. (1997). Differences between information about type A, anger and social support and the relationship with blood pressure. Psycho logy and He alth, 12, 453-468. doi:10.1080/08870449708406722 Barlett, D. (1998). Stress: Perspectives and processes. Buckingham: Open University Press. Brewing, C. R., Furnham, A., & Howes, M. (1989). Demographic and psychological determinants of homesickness and confiding among students. Journal of Psychology, 80, 467-477. Brown, S. D. (1996). The textuality of stress, drawing between scien- tific and everyday accounting. Journal of Health Psychology, 1, 173-193. doi:10.1177/135910539600100203 Clark, D. A., Hemsley, D., & Nason-Clark, N. (1990a). Personality and sex differences in emotional responsiveness to positive and negative cognitive stimuli. Personality and Individual Differences, 8, 1-7. Clark, D. A., Beck, A. T., & Stewart, B. (1990b). Cognitive specificity and positive negative affectivity. Complementary or contradictory views on anxiety and depressant. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 148-155. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.99.2.148 Cosden, M. A., & McNamara, J. (1997). Self-concept and perceived social support among college students with and without learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 20, 2-12. doi:10.2307/1511087 Fisher, S., & Hood, B. (1987). The stress of the transition to university: A longitudinal, absent-mindedness and vulnerability to homesickness. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 425-441. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1987.tb02260.x Fisher, S., & Hood, B. (1988). Vulnerability factors in the transition to university; self-reported mobility history and differences as factors in psychological disturbance. British Journal of Psychology, 79, 309- 320. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1988.tb02290.x Goldberber, L., & Shlomo, B. (1993). Handbook of stress theoretical and clinical aspects (2nd ed.). Free Press. Goldman, C. S., & Wong, E. H. (1997) Stress and college students. Education, 117, 604-611. King, N. J., Ollendrich, T. N., & Gullone, E. (1991). Negative affectiv- ity in children and adolescents. Relations between anxiety and de- pression. Clinical Psych ol o gy Review, 11, 441-450. doi:10.1016/0272-7358(91)90117-D Long, B. (1998). Stress management for school personnel: Stress-inoculation. Training and Exercise: Psychology in the Schools, 25, 318. Naquin, M. R., & Gilbert, G. (1996). College students’ smoking be- havior, perceived stress and coping styles. Journal of Drugs and Education, 26, 367-376. doi:10.2190/MTG0-DCCE-YR29-JLT3 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 148  D. G. LYRAKOS Odgen, J., & Mtandabari, T. (1997). Examination stress and changes in mood and health related behaviors. Psychology and Health, 12, 289-299. doi:10.1080/08870449708407406 Parkes, K. R. (1990). Coping negative affectivity and the work envi- ronment addictive and interactive predictors of mental health. Jour- nal of Applied Psychology, 75, 399-409. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.75.4.399 Rapolow, L. E. (1987). Plain talk about handling stress. New York: G. E. Editions. Ronan, K. R., Kendall, P. C., & Rowe, M. (1994). Negative affectivity in children. Development and validation of the self statement ques- tionnaire. Cognitive Ther apy a nd Research, 18, 509-528. doi:10.1007/BF02355666 Ross, S. E. B., Niebling, C., & Heckert, T. M. (1999). Sources of stress among college students. College Students, 33, 312-318. Saranson, I. G., Basham, R. B., & Saranson, B. R. (1983). Assessing social support: The social support questionnair. Journal of Personal- ity and Social Psychology, 44, 127-139. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.127 Schwarzer, R. (1999). Self-regulatory processes in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors, the role of optimism. Journal of Health Psychology, 4, 115-127. doi:10.1177/135910539900400208 Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Lynch, M. (1993). Self-image resilience and dissonance: The role of affirmational resources. Journal of Per- sonality and Social P sychology, 64, 885-896. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.64.6.885 Steer, R. A., Clark, D. A., Beck, A. T., & Ranieri, W. F. (1995). Com- mon and specific dimensions of self-reported anxiety and depression: A replication. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104, 542-545. Steptoe, A., Wardle, J., & Polland, T. M. (1996). Stress, social support and health-related behaviour: A study of smoking, alcohol consump- tion and physical exercise. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 41, 171-180. doi:10.1016/0022-3999(96)00095-5 Steptoe, A., Wardle, J., & Polland, T. M. (1996). The European health and behaviour survey: The development of an international study in health psychology. P s ychol ogy a nd He alth, 11, 49-73. doi:10.1080/08870449608401976 Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: The disposi- tion to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465-490. Watson, D. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Person- ality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 Wiebe, D. J. (1991). Hardiness and stress moderation: A test of pro- posed mechanisms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 89-90. Weidner, G., Kohlmann, C. W., Dotzauer, E., & Burns, L. R. (1996). The effects of academic stress on health behaviors in young adults. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 9, 123-133. doi:10.1080/10615809608249396 Wolf, V. V., Finch, A. J., Saylor, C., Blount, L., Pallmayer, T. P., & Carek, D. S. (1987). Negative effectivity in children: A miltrait-mul- timethod investigation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychol- ogy, 55, 245-250. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.55.2.245 VanGalder, K. F., & Zagumny, M. J. (1999). Social and emotional self-perceptions among students with learning disabilities at voca- tional and liberal arts postsecondary institutions. Manuscript sub- mitted for publication. European Report of Education 2001. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 149

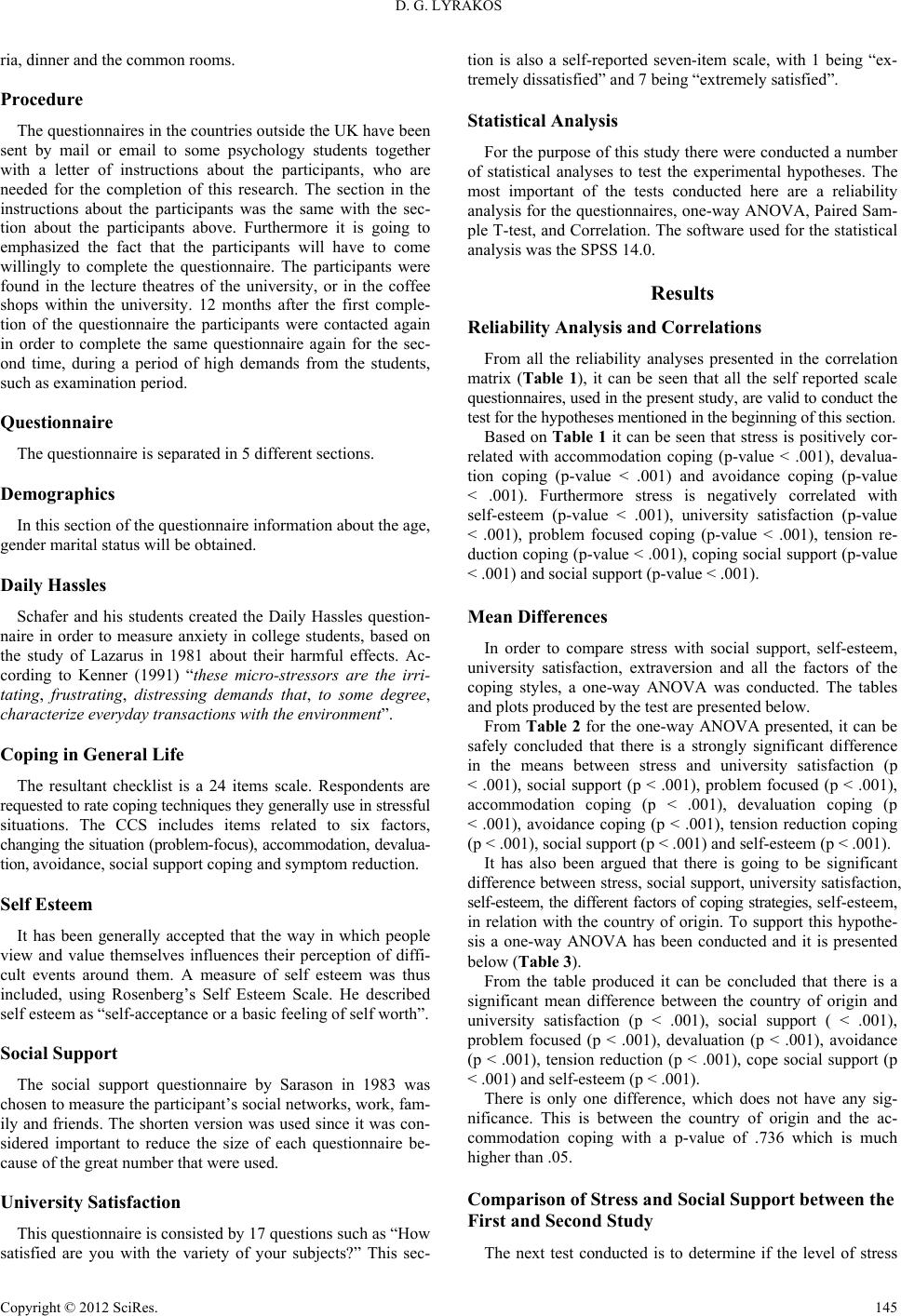

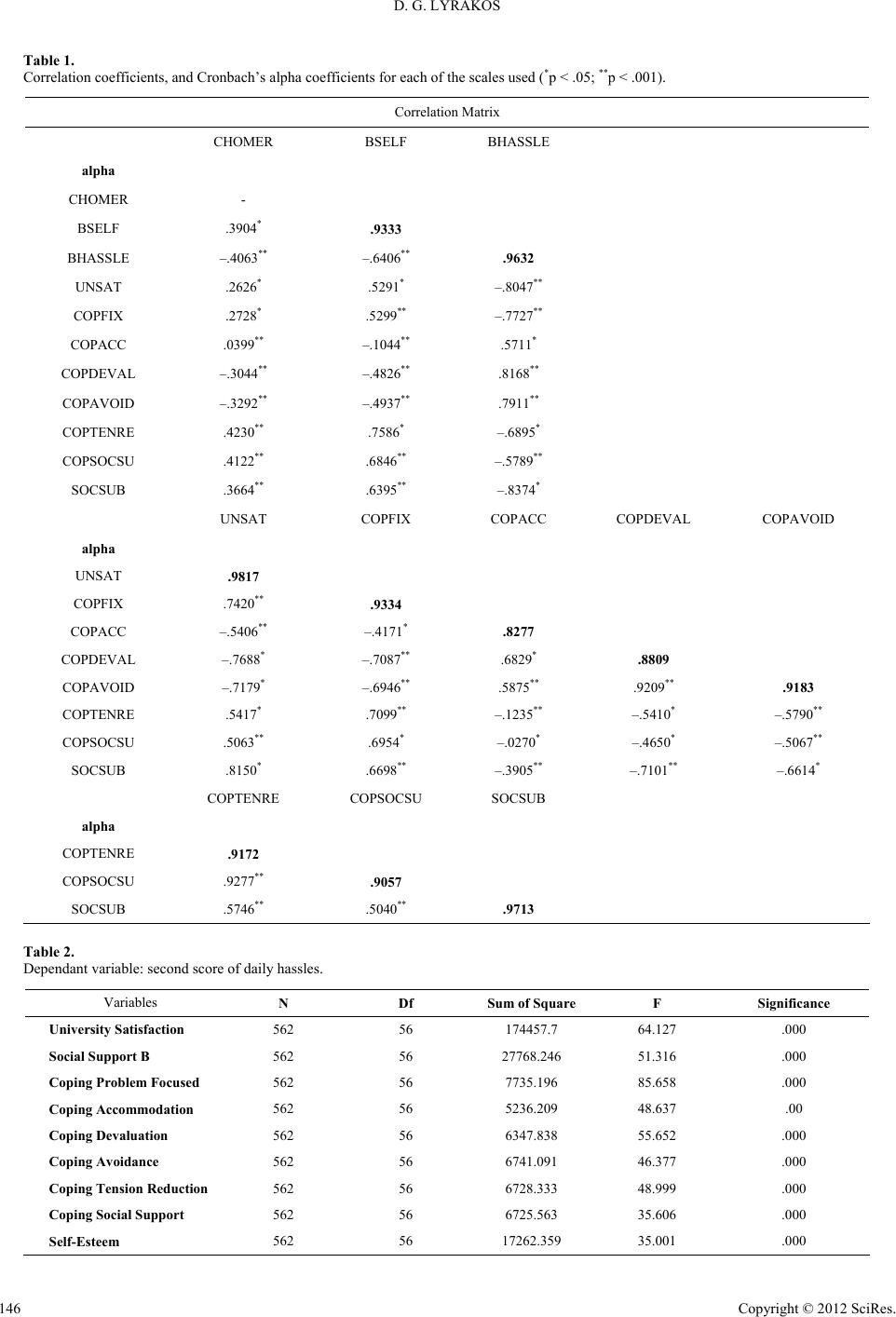

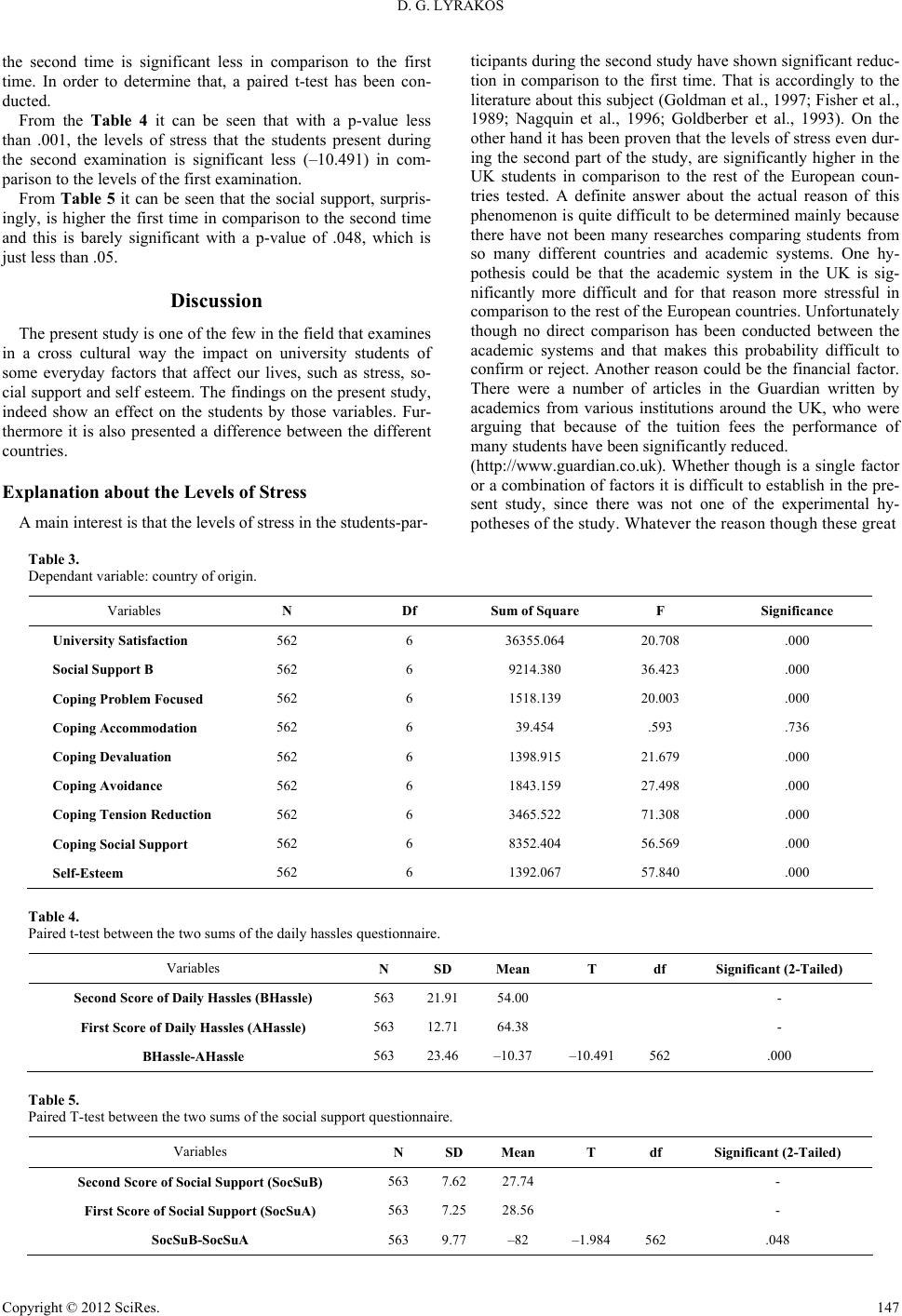

|