Creative Education 2012. Vol.3, No.1, 67-74 Published Online February 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ce) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.31011 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 67 An Expressive Arts-Based and Strength-Focused Experiential Training Program for Enhancing the Efficacy of Teachers Affected by Earthquake in China Rainbow T. H. Ho1,2*, Fumin Fan3, Angel H. Y. Lai4, Phyllis H. Y. Lo2, Jordan S. Potash2, Debra L. Kalmanowitz2, Joshua K. M. Nan2, Alicia K. L. Pon2, Zhanbiao Shi5, Cecilia L. W. Chan1,2 1Department of Social Work & Social Administration, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China 2Centre on Behavioral Health, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China 3Department of Psychology, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China 4George Warren Brown of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, USA 5Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China Email: *tinho@hku.hk Received October 22nd, 2011; revised December 18th, 2011; accepted January 8th, 2012 The 2008 Sichuan Earthquake killed over 9000 teachers and children leaving profound physical and emo- tional problems are prevalent among survivors. Many being victims themselves, teachers in the earth- quake affected areas not only have to recover a sense of personal efficacy in dealing with the difficulties, they also need to feel adequately prepared in their teaching roles to handle the changes in the classroom environment and student needs. Expressive art is a well-established tool to facilitate the expression of thoughts and feelings that can also be incorporated as interactive classroom activities—an approach that deviates from the traditional top-down teaching mode in China. A 3-day experiential training program based on expressive arts and strength-focused approaches was provided for 57 elementary and high school teachers across the earthquake area. This study evaluated changes after the training program. Re- sults showed that teachers’ general self-efficacy and teaching efficacy were significantly improved (t = 2.54, p = .01; t = 4.08, p = .00). The improvement in teaching efficacy is contingent upon the quality of relationship with students, after controlling for ethnicity. Keywords: Expressive Arts; Experiential Learning; Strength-Focused; Efficacy; Earthquake; Trauma Introduction The Sichuan earthquake on May 12, 2008 was one of the most serious natural disasters in China’s recent history (Higgins, Xiang, & Song, 2010). Approximately 70,000 people were killed and nearly 400,000 were injured (UNICEF, 2008). It is estimated that 3000 schools collapsed and that over 9000 teachers and students were killed, which accounted for about 12% of the to- tal victims (Macartney, 2009). Studies showed that affected tea- chers and children suffered from both undesirable feelings (e.g., anxiety and nervousness) and somatic symptoms (e.g., fatigue) (Niu, Zhu, & Zou, 2009; Zhang, Zeng, & Lai, 2009; Zhang, Kong, Wang, Chen, Gao et al., 2010). In addition to the traumatic ex- periences, teachers faced additional stress. Some teachers were blamed for leaving their students behind (Spencer, 2008) and others were arrested by the government for publicly criticizing pre-earthquake corruption activities that led to the massive col- lapse of school buildings (Hooker, 2008; Lan, 2008). The result- ing research confirmed that teachers suffered a higher level of stress than their students, which prompted social scientists and government officials to suggest targeted interventions and sup- port for them (Niu et al., 2009; Y. Zhang et al., 2010). Higgins, Xiang and Song’s (2010) review of the Sichuan earthquake’s post disaster management found that most inter- ventions focused on asking the victims to express their feelings, but many survivors felt annoyed by the overemphasis on their negative emotions. Given that Chinese cultural values discour- age overt expression of emotions, it may be more appropriate to limit expectations on verbal expression of negative emotions and instead focus on promoting strengths and positive outcomes (Chan, Chan, & Ng, 2006). Beyond cultural norms, there is also grow- ing evidence from neuroscience and the post-traumatic response of alexithymia that trauma may be better accessed and proces- sed through non-verbal means, such as arts-based practices (Gantt & Tinnin, 2009). Art making paired with a positive focus (i.e., focusing on a positive event) was found to lead to immediate stress reduction, whereas focusing on a negative event resulted in a slight increase (Curl, 2008). With all these considerations, we sought to create an inter- vention based predominantly on arts-based and strength-focused approaches which encourage emotional expression, hope and po- sitive attitude to life. By offering it as an experiential training, we could simultaneously provide the teachers with new skills for self-care and student interaction, while providing necessary support services. Our hope was that offering an alternative me- thod of post-disaster intervention would help teachers, as well as, students who had experienced earthquake related trauma. The Effect of Trauma o n Teachers *Corresponding author. The multiple losses resulting from most natural disasters lead  R. T. H. HO ET AL. to a myriad of practical and emotional challenges for the indi- vidual. Victims’ perceived competence to maintain personal functioning despite situational demands has been found to be an important mediator of posttraumatic recovery from long term emotional distress (Benight & Bandura, 2004). Such perceived competence, otherwise known as self-efficacy, is a personal appraisal of their ability to cope and perform under difficulty, to exercise control over their fears and to recover. Bandura (1997) theorized that victims who feel capable to overcome the after- maths of the trauma do so through reality testing, thereby al- lowing positive experiences to affirm their tests of self-efficacy. By focusing on their strengths, individuals can activate the self-confidence nece- ssary to grow through pain and rediscover inner resources previously unrecognized (Chan et al., 2006; Saleebey, 1996). Besides self-efficacy, trauma can severely challenge the sense of competence at work. After mass disasters, teachers are expec- ted to play a significant role in assisting students through the trauma, particularly in facilitating communication about the di- saster with the children and enhancing compassion and mutual support among students (Gaffney, 2008). There is an undeni- able value of teacher-mediated interventions in lowering PTSD rates among school children after natural disasters (Wolmer, Laor, Dedeoglu, Siev, & Yazgan, 2005). Yet, this additional responsibility for teachers to assume the role of mental health providers is not an identity that all teachers feel comfortable undertaking (Wolmer, Laor, & Lazgan, 2003). Reluctance is often attributed to the teachers’ lack of adequate knowledge and skills to provide mental health support to a degree beyond their typical role as educators. Other classroom problems arising from post-quake aftermaths may also contribute to a sense of low teaching efficacy among teachers. Teaching-efficacy is defined as teachers’ beliefs in their skills in delivering a variety of classroom instructional strategies, ma- naging classroom and engaging students in the learning process (Tschannen-Mora & Hoy, 2001). Higher teaching efficacy resulted in adopting desirable coping strategies, which facilitated recov- ery from the earthquake trauma (Shen, 2009). Lower teaching efficacy predicted higher levels of exhaustion and lower levels of personal accomplishment (Li, Yang, & Shen, 2007). Moreover, higher teacher-efficacy promoted warm interpersonal relation- ships with students by creating a supportive learning atmos- phere (Ashton & Webb, 1986; Tschannen-Moran, Woolfolk Hoy, & Hoy, 1998), which in turn positively affected student aca- demic performance (Guo, Piasta, Justice, & Kaderavek, 2010; Ogah, 2006). Increasing teacher self-efficacy and teaching-effi- cacy can aid in both their personal well-being as well as their student’s educational achievements. Experiential Learning: Effective Way to Learn and Master Skills One of the ways to develop self and work efficacy is through the mastery of experiences, which is defined as individuals’ suc- cessful experiences of overcoming obstacles and challenges (Ban- dura, 1997). Training teachers to master new teaching and com- munication methods offers them an opportunity for professional skill development that can achieve the specific purpose of en- hancing self-efficacy. It is equally important for teachers to ac- quire adequate confidence during professional trainings so that they may transfer the knowledge into actual practice (Anderson, 2002). An effective way in doing so is by putting knowledge into practice through mirroring real situations. Kolb (1984) de- fined such experiential learning as knowledge generation through the transformation of experience. One of the reasons that experien- tial learning may be more effective than traditional classroom learning is due to the multi-sensory and active involvement that stimulates the ability to receive information (Laird, 1985). Curry, Fazio-Griffth, Carson and Stewart (2010) found that experiential education on exercise immunology increased participants’ gen- eral efficacy and understanding on the course content; while Mathers (2006) demonstrated that practicum learning experience increased clinicians’ counseling self-efficacy. In addition, expe- riential learning may greatly enhance the relationship between teachers and students (Kelley & Whatley, 1980). Use of Expres s i ve Art s Activiti es as a Tool for Facilitating Learning and Training One method of engaging experiential learning is through the arts. The creative process involved in the arts requires involve- ment and attention, that stimulates problem solving and decision making (e.g. choices of arts materials and forms etc.) while pro- viding opportunities for exploring the self, others and environ- ment (Foster, 1992). As an additional benefit, artsbased active- ties promote mental well-being and stress reduction, as it allows for emotional expression and building a sense of satisfaction from the creation process (Walsh, Chang, Schmidt, & Yoepp, 2005; Walsh, Martin, & Schmidt, 2004). Expressive arts thera- pists have demonstrated how to make use of these processes in the service of therapeutic treatment and healing, specifically for people affected by trauma (Ahmed & Siddiqi, 2006; Jasenka, 1995). In addition to providing therapeutic benefit, the arts can be used as tool for teaching. Oreck (2004) noted that the increased use of the arts in teacher’s professional development and edu- cation is not for transforming teachers into arts specialists. Ra- ther, it is intended to enhance their competence in adopting a variety of medium for teaching, communicating and engaging students in the learning process (Foster, 1992; Fowler, 1996). Thomas & Mulvey (2008) reported that when the arts are used in this manner, learning was enhanced for both students and teachers, as this process involves the exchange of ideas and opi- nions among students and also between students and teachers. Unlike the traditional classroom environment where the teacher is the authority and communication is generally top-down, an interactive relationship enhances student motivation (Hughes & Kwok, 2007; Ryan & Patrick, 2001), which in turn renders them more interested in and engaged in the learning process (Skinner & Belmont, 1993). An additional feature of expressive arts is their therapeutic origins of being non-judgmental and suppor- tive which potentially transforms the classroom into a learning community where everyone contributes. Zhao and Kuh (2004) demonstrated that students in such an environment are intrinsic- cally motivated to learn, greatly aiding classroom management. Buildin g an A r t s-Based and Strength- F ocused Training Program In view of the benefits of using arts activities in a training that promotes personal well-being and new skill acquisition, the authors designed an arts-based and strength-focused experiential training program for school teachers affected by the Sichuan earth- quake specifically to enhance the self and teaching efficacy of educators (Figure 1). Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 68  R. T. H. HO ET AL. Figure 1. The expressive arts-based strength-focused experiential training pro- gram for teachers in Sichuan China. The present study was conducted for evaluating how an ex- pressive arts-based training program can help these teachers be- come aware of their own personal strengths while feeling more capable in their teaching roles. In addition, perceived efficacy attenuates the transfer of learned capabilities from the training back to the work setting (Anderson, 2002). Therefore, hypo- theses for the study included: 1) teacher’s general self-efficacy would increase after their participation in the training program; and 2) teachers’ teaching efficacy would increase after their par- ticipation in the program. Based on previous research on the associations between teacher-student relationship, general self- efficacy and teaching efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Klassen & Chiu, 2010; Siu, Spector, Cooper, & C. Lu, 2005; Wolters & Daug- herty, 2007), we also wanted to explore to what extent teacher- student relationship related to the changes of teaching efficacy after the training, because experiential learning and artsbased activities strongly emphasize and promote interactions between teachers and students. We hypothesized that better teacher- student relationship would result in greater changes of teaching efficacy after the training. Methods Participants Fifty seven school teachers between 21 and 72 years old, in Beichuan County and An County in the Sichuan province of China participated in the training program. Participants were from 20 secondary and 16 primary schools in rural and urban Sichuan. All of their schools were damaged at various levels, ranging from complete demolition to minor fall of fragments from the school buildings. The participants were recruited through a con- venience sampling strategy. The research team had limited influence in the sampling process as the Sichuan province monitored the organization of large scale disaster-related inter- ventions in the post-earthquake zones. The team first contacted the Institute of Psychology, China Academy of Science to es- tablish contact with the local governmental education department. The education department then selected the targeted schools and contacted the principals. The principals were subsequently asked to submit a list of teachers, who were then invited to participate in the program. Procedures A single-group pretest posttest design was adopted to meas- ure the changes in participants’ general self-efficacy and teach- ing efficacy right before and right after the 3-day training pro- gram. Governmental restrictions on conducting earthquake relief projects in Sichuan made it difficult for the researchers to recruit a control group for a quasi-experimental design. All recruited tea- chers had to participate in the same training. The current study also took into account certain confounding variables, namely, the teachers’ gender, education level, hours at work per day and teaching experiences, which may be related to the teachers’ ge- neral self-efficacy and teaching efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Klas- sen & Chiu, 2010; Siu et al., 2005; Wolters & Daugherty, 2007). Given that the participants were earthquake survivors, extra precautions were taken to protect this vulnerable population. Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong. The pretest and the posttest were designed to avoid trauma-related or emotional- related questions to limit overburdening the participants. All teachers were required to fill out the informed consent, which discussed participants’ privileges and the potential risks and be- nefits involved in the evaluation research. Information obtained was kept strictly confidential and was sent back to Hong Kong for analysis. Measurements General Self-Efficacy. The Chinese version of the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) was used to measure the general self-efficacy of the participants (Zhang & Schwarzer, 1995). The scale consists of 10 items that evaluates general self-ef- ficacy on a 4 point scale, namely, not at all true, hardly true, moderately true, and exactly true. A high total score means a high level of general self-efficacy. The scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .94) for the current sample. In addition, the scale has high internal and convergent and di- vergent validity across various cultural groups (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995). Teaching Efficacy. The Ohio State Teacher Self-Efficacy Short-Form (OSTES) was used to measure the teaching ef- ficacy of the participants. The scale, which consists of 12 items, measures the teachers’ beliefs in their ability to offer a variety of instructional strategies, manage their classrooms and engage their students on a 9 point scale, ranging from “no ability” to “having much ability”. The 3 subscales meas- ure perceived efficacy in 1) student engagement; 2) instruct- tional strategies; and 3) classroom management. A high to- tal score means a high teaching efficacy. A member of the team translated the scale into Chinese and reviewed it for cultural appropriateness and sensitivity. A research assistant back translated it to English to ensure that all items were in- terpreted correctly. The scale demonstrated high internal con- sistency in the current study (α = .921). Previous research also showed that the scale demonstrated high reliabilities and construct and discriminative validity among teachers in Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 69  R. T. H. HO ET AL. the United States (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001). Teachers’ perceive d relationship with stude nts. Since we could not observe the changes of teacher-student relation- ship immediately after the training, we looked at teachers’ perceived relationship with student. A single item measure was used for this evaluation. Teachers were asked to rate their responses to the statement “I have a good relationship with my students.” on a 5 point Likert scale, ranging from extremely disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor dis- agree, somewhat agree to extremely agree. Demographic variables. The demographic variables included: gender, ethnicity (coded as Han = 1 and minority ethnic group = 2) education level (coded as primary = grade 1 to 6, secondary = grade 7 to 13 and tertiary level = over grade 13), work hours per day (coded as high = over 11 hours, medium = between 8 and 10 hours and low = less than 7 hours), and teaching experience (coded as low = less than 5 years, medium = 6 to 10 years, and high = over 10 years). Interventio n: Arts-Based and Str e n g t h-Focuse d Training Program A collaborative team composed of experts in expressive arts therapy and group counseling led the training, which included: qualified art therapists, dance movement therapist, play thera- pist, social workers, psychologists and counselors from The Uni- versity of Hong Kong and Tsinghua University. The 3-day pro- gram was held in September 2009, 16 months after the Wenchuan earthquake and prior to school commencement. The program was modeled on the Kolb experiential learning theory (Kolb, Boyatzis, & Mainemelis, 2001) and expressive arts training mo- dels (Kalmanowitz & Potash, 2010). The program was designed according to Kolb’s four-stage model which includes: 1) con- crete experience: experiencing the new knowledge; 2) reflective observation: observing other people’s mastering the knowledge; 3) conceptualization: conceptualizing the knowledge through re- lating it to existing theories; 4) experimentation: applying the knowledge in real life settings. Teachers first experienced various kinds of expressive arts activities, including art making with dif- ferent materials, dance and movement with and without music, dramatic play and cooperative games which intended to help arouse interest and increase comfort in using art (concrete experience). Throughout the process, teachers were constantly encouraged to reflect on their experiences with the activities (reflective obser- vation). On the second day, the teachers learned about the under- lying concepts and theories of expressive arts through hands-on activities. Through dance, visual arts, music and drama activities, teachers were led to relate the use of expressive arts into their classrooms as a means to encourage expression, integration of ex- perience and growth, as well as establishing mutual respect and support among students (conceptualization). Activities were adapt- ed from expressive arts therapeutic tools to be short enough as a class activity with self-reflective and expressive components. On the third day, teachers developed expressive arts-based acti- vity plans related to their teaching, in the areas of classroom ma- nagement and communication or as a therapeutic recreational ac- tivity (experimentation). Teachers shared their ideas with the whole group and received feedback from the trainers and other participants (reflective observation). Throughout the project, we purposefully placed a strong em- phasis in training the teachers on the expressive and communi- cative aspects of expressive arts, rather than the therapeutic ones, since teachers are not expected to be proxy therapists or coun- selors. The trainers’ role modeled this stance by providing empa- thic understanding rather than active therapeutic interventions to demonstrate to the teachers how they can support their students. Both positive feelings (such as hope, gratitude, love, care) and ne- gative emotions (such as sadness, anxiety, fear, and loneliness) were equally welcomed in order to provide chances for partici- pants to ventilate their feelings freely. For positive emotions, further exploration and elaboration were encouraged; while for negative emotions, trainers relied on containment interventions with a focus on active listening to promote a supportive pres- ence and establishing a sense of togetherness. Training also em- phasized finding meaning and strength from the negative ex- periences. At the end of the training, teachers were required to reflect on their positive experiences of mastering the basic skills as they finished presenting the self-designed activities, thus lend- ing the whole process a strength-focused outlook. Results Participants A total of 57 participants completed both the pre- and post- evaluations. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the sample. Before conducting data analysis, exploratory analysis was performed to ensure that the data fit the statistical assumptions. The test of normality was conducted for the pretest and posttest scores of the General Self-Efficacy Scale and Teaching Efficacy Scale. Results indicated that they all had normal distributions and the variances of all scales in the two data collection points were relatively equal (data now shown). Paired sample t-test was then used to compare the means of the pretest and posttest measures. Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participating teachers. Demographic Characteristics n % School Primary 29 51 Secondary 28 49 Gender Male 27 47 Female 30 53 Ethnicity Han 46 81 Non-Han 11 19 Education Level Low 9 16 Medium 7 7 High 41 72 Teaching Experience Low 15 26 Medium 30 53 High 9 16 Missing 3 5 Hours at Work Per Day Low 4 7 Medium 45 79 High 8 14 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 70  R. T. H. HO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 71 General Self-Efficacy and Teaching Efficacy Significant increases in General self-efficacy scores (t = 2.54, p = .01, d = .28) and the teaching efficacy scores (t = 4.08, p = .00, d = .57) were found. All 3 domains of Teaching Efficacy, including student engagement (t = 3.02, p = .00, d = .40), in- structional strategies (t = 2.22, p = .03, d = .32) and classroom management (t = 4.60, p = .00, d = .64) were significantly in- creased with medium effect size (Table 2). Correlation and Regression Analysis Correlation analysis revealed that Ethnicity (Han or other ethnic minorities) and perceived Relationship with Students were associated with Teaching Efficacy and its two subscales, namely Student Engagement and Classroom Management subscales (Ta- ble 3). No relationship was observed for General Self-Efficacy with other variables. In order to further explore how perceived teacher-student relationship related to the changes of teachers’ efficacy after the training, regression analysis was performed (Table 4). Ethnicity, which was a stable construct, was first entered into the analysis. Regression equation of this first model was significant (R2 = .09, Adjusted R2 = .07, F(1, 48) = 4.64, p = .036), meaning that members of ethnic minorities, mainly (Qiang), predicted a greater change of teaching efficacy after the training. Perceived relationship with students was then en- tered into the model and the final equation was also significant (R2 = .20, Adjusted R2 = .16, F(2, 28) = 5.58, p = .007). The Adjusted R2 was .16 implying that the relationship with Stu- dents accounted for an additional 16% variance of Teaching Efficacy. These findings showed that teachers with better rela- tionships with students predicted greater increases in Teaching Efficacy after the training. Classroom Expressive Arts Activities Prop osed The types of activities proposed range from warm-up active- ties, emotional expression, creativity and problem solving, build- ing interpersonal trust and the enhancement of study interest. Sample activities are listed below (Table 5). Discussion The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the use of the experiential arts-based and strength-focused training pro- gram for helping teachers affected by the earthquake, as indi- cated by improvement in their self and teaching efficacies. The statistically significant increase in both of these areas supported the hypotheses. All 3 subscales of Teaching Efficacy, including student engagement, instructional strategies and classroom ma- nagement, were enhanced after the training. The larger increase in teaching efficacy relative to general self-efficacy and its mo- derate effect size may relate to the specific nature of the train- ing program as an opportunity to enhance professional develop- ment, although there was still a positive effect on personal well- being. The significant increase in the teachers’ self-efficacy in this study reflects how engaging in the arts and creative process wi- thin a supportive environment parallels the beneficial effects of the arts in such areas as reducing stress, improving self-confidence, opening up new perspectives, and enhancing the general ability to cope with problems (Dahlman, 2007; Oakley, 2008; Zuo, 1998). As suggested by Oreck (2004), the motivation to use arts ac- tivities in class arises from a sense of efficacy, particularly in linking arts activities to their own teaching aims. The positive findings of this research, particularly in regards to the increases in teaching efficacy lay the foundation for promoting expres- sive arts into the Sichuan classroom. The statistically signify- cant improvements in the teachers teaching efficacy, as meas- ured in student engagement, instructional strategies and class- room management can be explained in part by the design of the training and the modeling of the trainers. By combining both theoretical and experiential components, the teachers were able to fully experience the process, which enhanced their under- standing of the theories. Table 2. Changes in outcome measures. Pre-Test Post-Test Variable n M SD M SD t d General Self Efficacy 5726.865.66 28.35 5.07 2.54** .28 Teaching Self Efficacy 5085.6616.16 94.26 14.3 4.08*** .57 Instrumental Strategies 5724.965.07 26.49 4.6 2.22* .32 Classroom Management 5523.674.45 26.4 4.2 4.60*** .64 Student Engagement 5624.664.96 26.55 4.58 3.02*** .40 *p ≤ .05 **p ≤ .01 ***p = 0.00. Table 3. Correlation of outcomes and control variables. Pre and Post test changes School (Primary/Secondary) Age Years of Teaching Experience Teacher’s Educational Level Daily Working Hours Ethnicity (Han/Ethnic Minority) Relationship with Students General Self Efficacy .03 .17 .00 .05 .03 .09 .12 Teacher Efficacy (OSTES)—Total score .15 .21 .04 .07 .04 .31* .35* Student Engagement .03 .20 .13 .04 .02 .34* .26 Instructional Strategies .06 .20 .13 .02 .01 .31* .27* Classroom Management .12 .07 .08 .16 .04 .29* .39** *p < .005; **p < 0.01.  R. T. H. HO ET AL. Table 4. Hierarchical linear regression of teaching efficacy (total score) and relationship with students after controlling for ethnicity. Dependent variable Instructional strategies Model Independent variables b SE b ß t 1 Ethnicity 9.47 4.40 .30 2.16* R2 .09 Adjusted R2 .07 ΔR2 .09 F 4.64* 2 Ethnicity 8.49 4.20 .27 2.02* Relationship with students 4.45 1.82 .33 2.45* R2 .20 Adjusted R2 .16 ΔR2 .11 F 5.58** *p < .005; **p < 0.01. Table 5. Classroom expressive arts activities proposed by teachers. Activity goal Example activity Emotional expression Reflecting and expressing students’ gratitude in relation to the support they received after the earthquake through visual arts. Ritual of thanks by the whole class through music and movement. Creativity in problem solving If the school is flooded, build a life boat in a small group with a large piece of paper. Subsequent sharing on the experience of creation. Building interpersonal trust Trust walk with a partner who is not allowed to speak. Academic Engagement Using drama and skits to compose a story behind Chinese proverbs. The trainers provided examples of how expressive arts acti- vities could be used for team building, classroom management, communication, improving concentration and cheerful atmos- phere for the students. This role modeling supported the teach- ers to create their own activities based on their specific back- grounds, abilities and specific constraints in their schools, there- by encouraging critical analysis and application of their learning. The finding of the regression analysis that teacher-student re- lationship was the major contributor in predicting the gains in teacher’s teaching-efficacy may be explained by the expressive arts nature and experiential approach used in the training. As pre- viously stated, the expressive arts promote teacher –student en- gagement that enables stress reduction, which promotes stron- ger relationships. Experiential learning, on the other hand, pro- motes active and positive interaction between teachers and students. Of course, the validity of this prediction can only be confirmed with future longitudinal study. Another implication from the regression analysis is that professional training which aims at imparting teachers with skills to improve their teaching efficacy may show greater benefits when also addressing the is- sue of improving student-teacher relationships. In this training, making use of the expressive arts deepened the experiential learning for the teachers and gave them a medium for increase- ing their relationships with their students. In addition, the ana- lysis also indicated that teachers who are ethnic minorities re- lated to greater changes of teaching efficacy. This finding may be explained by the high cultural value the Qiang ethnic group places on arts and music which renders them more expressive and more involved in the artistic activities of the training. Such teachers understood the benefits quicker and were more willing to engage in the process. Lastly, the use of expressive arts activities in post-disaster training and as a tool for teachers to work with students responded to the problem of overemphasis on negative emotions and verbal expression among prevailing interventions or training delivered in the earthquake affected areas (Chan et al., 2006; Higgins et al., 2010). In the Sichuan context, this strength-based experien- tial learning approach that we adopted was revolutionary. Chi- nese teachers are seldom asked to actively participate in active- ties in conventional intervention programs. We believe the suc- cess of our training program was that it was designed on thera- peutic principles, but presented as an educational training pro- gram for skill enhancement, rather than for personal healing. Instead of dwelling on the trauma, participants focused on de- veloping their self and teaching efficacies in the training pro- gram, which may have assisted their recovery process indirectly and decreased their negative emotions in the long run (Benight & Bandura, 2004; Li, Yang, & Shen, 2007; Shen, 2009). Even though our methods may be viewed conspicuously in a Chinese context, the increases in self and teaching efficacy reflected the benefits of our approach. Certain limitations in this study merit discussion. Firstly, the relatively small sample size and a small number of control va- riables limited a comprehensive understanding of the findings. A small sample size resulted in an imbalanced ratio on the demographic variable of ethnicity, where ethnic minorities were only represented by about 19% of the data. Secondly, we were confined to selecting our participants via convenient sampling strategy due to government restriction, and such non-random sam- pling strategy might affect the external validity of the study. Thirdly, the one-group pretest and posttest experimental design limited our ability to directly relate the interventions to the tea- chers’ improved scores. A longitudinal study that follows the process of utilizing art in the classroom is needed to confirm the positive benefits to teachers and also the prediction con- ducted in the regression analysis. Lastly, the self-report meas- ure is subject to teacher bias and does not include the students’ perceptions of teacher engagement. Even so, the perceived in- creased engagement by teachers indicates their increased rela- tionship with the students, which impacts how they interact with the students. For future studies aiming at confirming the results and pre- dictions made in the present study, a quasi-experimental design with a random sampling should be adopted. Since it has been suggested that positive relations existed between a) teachers’ ge- neral self-efficacy and their posttraumatic recovery and b) tea- chers’ teaching efficacy and their students’ outcome, future re- search should also include follow up studies that address the coping skills and emotional status of the teachers and the aca- demic or behavioral outcomes of their students (Benight & Ban- dura, 2004; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Ogah, 2006). An ex- tended follow up on the teachers throughout the academic year Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 72  R. T. H. HO ET AL. could add valuable information on the sustainability of training outcomes. Finally, future research can replicate this training study on different populations affected by natural disasters in China. Conclusion Notwithstanding the limitations, the current study carries im- portant implications for post-disaster support for teachers. The study offered preliminary support for the application of expres- sive arts in post-disaster teaching in China. Moving away from an emphasis on verbal expression of negative emotions by pro- viding an alternative medium of expression was welcomed by participants and can be applied to other disaster-related inter- vention research in China and Asia. This study advocates that disaster relief workers in China can focus on promoting sur- vivors’ positive outcomes, rather than merely focusing on re- storing the victims’ previous states of functioning prior to the trauma. The introduction of experiential learning and arts-based education in China will also serve as an innovative alternative to the traditional classroom and one-way teaching methods com- monly used across the Country. Acknowledgements The authors would like to express heartfelt gratitude to the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation and the Tsinghua Univer- sity Education Foundation for funding this project. Special thanks also go to trainers and project assistants from Tsinghua Univer- sity and The Institute of Psychology, China Academy of Sci- ences for their full support in the implementation of the training and research, and most importantly, to all the teachers and edu- cators for their participation. REFERENCES Ahmed, S. H., & Siddiqi, M. N. (2006). Essay healing through art therapy in disaster settings. Lancet, 368, S28-S29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69916-9 Anderson, N., Onesm D. S., Sinangil, H. K., & Viswesvaran, C. (2002). Handbook of industrial, work and organizational psychology: Per- sonnel psychology (Vol. 1). London: SAGE. Ashton, P., & Webb, R. (1986). Making a difference: Teacher sense of efficacy and student achievement. New York: Longman. Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W H Freeman. Benight, C. C., & Bandura, A. (2004). Social cognitive theory of post- traumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behavior Re- search and Therapy, 42, 1129-1148. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008 Chan, C. L. W., Chan, T. H. Y., & Ng, S. M. (2006). The strength- focused and meaning-oriented approach to resilience and transforma- tion (SMART): A body-mind-spirit approach to trauma management. Social Work in Health Care, 43, 9-36. doi:10.1300/J010v43n02_03 Curl, K. (2008). Assessing stress reduction as a function of artistic creation and cognitive focus. Art Therapy: Journal of American Art Therapy Association, 25, 164-169. Curry, J., Fazio-Griffth, L., Carson, R., & Stewart, L. (2010). Qualita- tive findings from an experientially designed exercise immunology course: Holistic wellness benefits, self-efficacy gains, and integration of prior course learning. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 4, 1-15. Dahlman, Y. (2007). Towards a theory that links experience in the arts with the acquisition of knowledge. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 26, 274-284. doi:10.1111/j.1476-8070.2007.00538.x Foster, M. T. (1992). Experiencing a creative high. Journal of Crea- tive Behavior, 26, 29-39. doi:10.1002/j.2162-6057.1992.tb01154.x Fowler, C. B. (1996). Strong arts, strong schools: The promising po- tential and shortsighted disregard of the arts in American schooling. New York: Oxford University Press. Gaffney, D. A. (2008). Families, schools, and disaster: The mental health consequences of catastrophic events. Fa mily Com munity Health, 31, 44-53. Gantt, L., & Tinnin, L. W. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psycho- therapy, 36, 148-153. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005 Guo, Y., Piasta, S. B., Justice, L. M., & Kaderavek, J. N. (2010). Re- lations among preschool teachers’ self-efficacy, classroom quality, and children’s language and literacy gains. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1094-1103. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.005 Higgins, L., Xiang, G., & Song, Z. (2010). The development of psy- chological intervention after disaster in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 1, 77-86. doi:10.1080/21507680903570292 Hooker, J. (2008). Penalty for China quake photos reported. The New York Times. URL. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/31/world/asia/31quake.html Hughes, J., & Kwok, O. M. (2007). Influence of student-teacher and parent-teacher relationships on lower achieving readers’ engagement and achievement in the primary grades. Journal of Educational Psy- chology, 99, 39-51. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.39 Jasenka, R. (1995). LA '94 earthquake in the eyes of children: Art ther- apy with elementary school children who were victims of disaster. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12, 237-243. Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Researc h, 79, 491-525. doi:10.3102/0034654308325693 Kalmanowitz, D., & Potash, J. S. (2010). Ethical considerations in the global teaching and promotion of art therapy to non-art therapists. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37, 20-26. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2009.11.002 Kelley, L., & Whatley, A. (1980). Student-teacher relationship in expe- riential classes and the student’s perception of course effectiveness. Journal of Experiential Learn i n g and Simulation, 2, 9-16. Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-effi- cacy and job satisfaction: Teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 741-756. doi:10.1037/a0019237 Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2001). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In L. Zhang (Ed.), Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles (pp. 227-247). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Laird, D. (1985). Approaches to training and development. Reading, Mass: Addison-Welsey. Lan, H. (2008). Teacher arrested for writing Sichuan earthquake victim slogan. The Epoch times. URL. http://www.theepochtimes.com/n2/china/sichuan-earthquake-victims -5217.html Li, Y., Yang, X., & Shen, J. (2007). The relationship between teachers’ sense of teaching efficacy and job burnout. Psychological Science (China), 30, 952-954. Macartney, J. (2009). China releases Sichuan earthquake child death toll—But no names. The Sunday Times. URL. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/article6245044.ece Mathers, J. F. (2006). An exploratory investigation of the interrelation- ships of experiential learning, outcome expectations, self-efficacy, and goals in clinical practica students. Dissertation Abstracts Inter- national Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 66. URL. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN= 2006-99003-067&site=ehost-live&scope=site Niu, Y., Zhu, F., & Zou, Y. (2009). Psychological survey and interven- tion after the Wenchuan earthquake in grade 12 students and teachers from Dujiangyan. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 23, 179-182. Oakley, K. (2008). The art of education: New competencies for the creative workforce. Media International Australia, 128, 137-143. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 73  R. T. H. HO ET AL. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 74 Ogah, J. K. (2006). Teachers’ efficacy to affect student learning. IFE Psychologia: An Int ernational Journal, 14, 16-35. Oreck, B. (2004). The artistic and professional development of teachers: A study of teachers’ attitudes toward and use of the arts in teaching. Journal of Teacher Education , 55, 55-69. doi:10.1177/0022487103260072 Ryan, A. M., & Patrick, H. (2001). The classroom social environment and changes in adolescents’ motivation and engagement during mid- dle school. American Educational Research Journal, 38, 437-460. doi:10.3102/00028312038002437 Saleebey, D. (1996). The strengths perspective in social work practice: Extensions and cautions. Social Work, 41, 296-305. Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio causal and control beliefs (pp. 35-37). Windsor, UK: NFER-NELSON. Shen, Y. E. (2009). Relationships between self-efficacy, social support and stress coping strategies in Chinese primary and secondary school teachers. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 25, 129-138. Siu, O., Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., & Lu, C. (2005). Work stress, self-efficacy, Chinese work values, and work well-being in Hong Kong and Beijing. International Journal of Stress Management, 12, 274-288. doi:10.1037/1072-5245.12.3.274 Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom— Reciprocal effects of teacher-behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 571- 581. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571 Spencer, R. (2008). China earthquake: Teacher admits leaving pupils behind as he fled Chinese earthquake. The Te l eg r a ph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/asia/china/2064945/Chi na-earthquake-Teacher-admits-leaving-pupils-behind-as-he-fled-Chi nese-earthquake.html Thomas, E., & Mulvey, A. (2008). Using the arts in teaching and learning: Building student capacity for community-based work in health psychology. Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 239-250. doi:10.1177/1359105307086703 Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Cap- turing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17, 783-805. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1 Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk Hoy, A., & Hoy, W. K. (1998). Tea- cher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Re- search, 68, 202-248. UNICEF. (2008). Helping quake-affected children cope with trauma in Sichuan province. URL. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/china_44073.html Walsh, S. M., Martin, S. C., & Schmidt, L. A. (2004). Testing the effi- cacy of a creative-arts intervention with family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36, 214-219. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04040.x Walsh, S. M., Chang, C. Y., Schmidt, L. A., & Yoepp, J. H. (2005). Lowering stress while teaching research: A creative arts intervention in the classroom. Journal of Nursing Education, 44, 330-333. Wolmer, L., Laor, N., & Yazgan, Y. (2003). School reactivation pro- grams after disaster: Could teachers serve as clinical mediators? Child Adolesc Psychiatric Clinics of North Ame rica, 12, 363-381. doi:10.1016/S1056-4993(02)00104-9 Wolmer, L., Laor, N., Dedeoglu, C., Siev, J., & Yazgan, Y. (2005). Teacher-mediated intervention after disaster: A controlled three-year follow-up of children’s functioning. Journal of Chi ld Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1161-1168. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.00416.x Wolters, C. A., & Daugherty, S. G. (2007). Goal structures and teach- ers’ sense of efficacy: Their relation and association to teaching ex- perience and academic level. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 181-193. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.181 Zhang, C., Zeng, N., & Lai, C. (2009). A Survey on teachers’ mental health after Wenchuan earthquake. http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-ZDTJ200905011.htm Zhang, J. X., & Schwarzer, R. (1995). Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: A Chinese adaptation of the general self-efficacy scale. Psychologia, 38, 174-181. Zhang, Y., Kong, F., Wang, L., Chen, H., Gao, X., Tan, X. et al. (2010). Mental health and coping styles of children and adolescent survivors one year after the 2008 Chinese earthquake. Children and Youth Ser- vices Review, 32, 1403-1409. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.06.009 Zhao, C., & Kuh, D. (2004). Adding value: Learning communities and student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45, 115-138. doi:10.1023/B:RIHE.0000015692.88534.de Zuo, L. (1998). Creativity and aesthetic sense. Creativi ty Research Jour- nal, 11, 309-313. doi:10.1207/s15326934crj1104_4

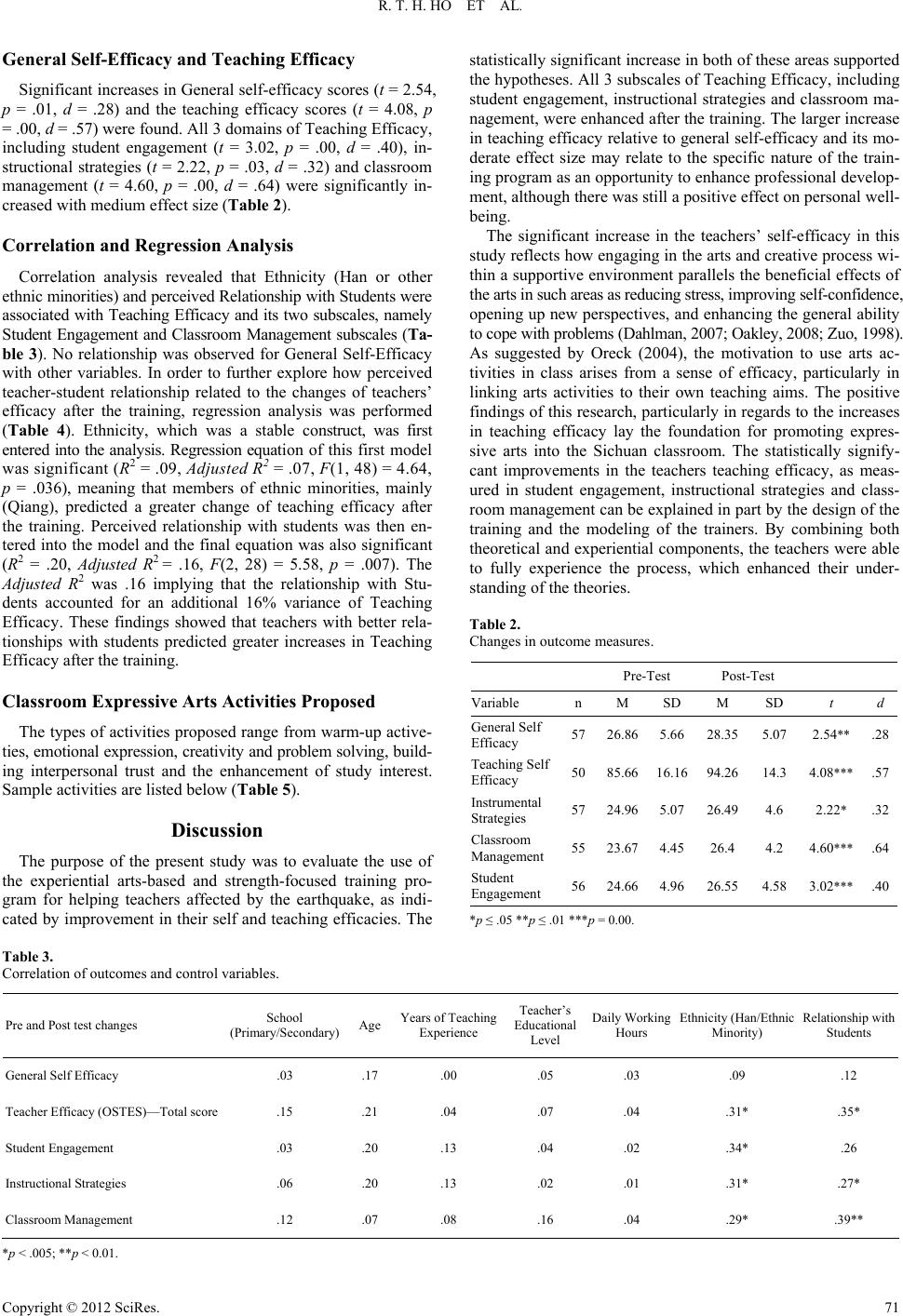

|