Psychology

Vol.09 No.04(2018), Article ID:83910,15 pages

10.4236/psych.2018.94047

A Differentiation of Self Scale in Two Domains for Japan: A Preliminary Study on Its Development and Reliability/Validity

Koji Kudo

Department of Educational Psychology, Tokyo Gakugei University, Tokyo, Japan

Copyright © 2018 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial International License (CC BY-NC 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Received: March 1, 2018; Accepted: April 20, 2018; Published: April 23, 2018

ABSTRACT

In this study, a differentiation of self scale was created applicable to two domains―intrapsychic and interpersonal, and was named the Differentiation of Self Scale in Two Domains (DSS-2D). A preliminary study was then performed on its reliability and validity. A questionnaire survey was conducted with university students (n = 273). Exploratory factor analysis results were used to divide DSS-2D into 4 subscales. The intrapsychic differentiation scale corresponded to intrapsychic differentiation, while 3 subscales―the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale, interpersonal differentiation individuality scale, and adaptive interpersonal relationship scale―corresponded to the interpersonal domain. The reliability coefficients for each subscale were sufficient. In all subscales, there was a significant correlation with trait anxiety, as was theoretically anticipated, and criterion-related validity was confirmed. These results support the future utility of DSS-2D.

Keywords:

Differentiation of Self, Intrapsychic Domain, Interpersonal Domain, Scale Development, Reliability and Validity

1. Introduction

1.1. Differentiation of Self

Differentiation of self is one of the main concepts in Bowen’s proposed Family Systems Theory. Differentiation of self is composed of two domains, differentiation in the intrapsychic domain and differentiation in the interpersonal domain. Intrapsychic differentiation is the balance between an individual’s thoughts and emotions, while interpersonal differentiation is the balance between the desire for individuality and togetherness in interpersonal relationships. Individuality is the desire to follow one’s own volition and be an individual autonomous and distinguishable from others. Togetherness is the desire to be dependent on, seek connections with, and be the same as others (Kerr & Bowen, 1988: pp. 64-65) . That is, differentiation is the ability to appropriately handle the “balance between thoughts and emotions” and the “balance between individuality and togetherness,” or rather the ability to sustain balance among each pair of concepts and manage the appropriate function of each while maintaining overall integration.

1.2. The Relationship between Differentiation of Self and Adolescence

Kerr and Bowen (1988) stated that development of differentiation of self is influenced by the degree of emotional separation from one’s family of origin (p. 98). This “emotional separation from family of origin” can also be referred to as “psychological independence from parents”. Erikson (1995: pp. 234-237) and Havighurst (1948: pp. 37-40) , who proposed the stages of life span development, say that psychological independence from one’s parents is rightly one of the major developmental challenges for adolescence. Therefore, differentiation of self is a concept deeply related to adolescence.

1.3. Differentiation of Self Hypothesis

The differentiation of self hypothesis supposes that people with low differentiation of self are vulnerable to stress (Bowen, 1978: p. 472; Kerr & Bowen, 1988: p. 97) . According to the differentiation of self hypothesis, people with low differentiation of self can easily let emotions dominate over thinking in stressful situations. If emotions become excessively dominant, it becomes difficult to make calm, logical judgments about various matters. The person is more likely to have a strong desire for togetherness rather than individuality and interpersonal relationships are likely to become states of fusion. Thus, people with low differentiation of self are unable to cope appropriately with stressful situations and are likely to develop maladjusted psychosocial states. However, people with high differentiation of self can maintain a balance between thoughts and emotions and between individuality and togetherness, even during stressful situations. They can cope appropriately with stressful situations while maintaining proper functioning of each of these. Prior studies conducted overseas have reported results generally supporting the hypothesis of differentiation of self (e.g., Choi & Murdock, 2017; Jankowski, Hooper, Sandage, & Hannah, 2013; Lampis, 2016 ).

If, as stated earlier, we consider differentiation of self to be a concept deeply related to adolescence, the differentiation of self hypothesis would be important for examining adolescent stress vulnerability.

1.4. Influence of Cultural Differences on the Differentiation of Self Hypothesis

The differentiation of self hypothesis assumes the influence of cultural differences, and therefore, it is not appropriate to automatically apply results of research conducted abroad to Japan. The differentiation of self hypothesis was formed based on Bowen’s clinical experience with European Americans in the United States, and many of these subjects had a cultural background that recognized the value of individualism and independence (Gushue & Constantine, 2003) . If we consider such cultures individualistic cultures, then at the opposite end of the spectrum are collectivist cultures. Japan is considered to have many aspects of a collectivist culture, and we cannot ignore the potential impact of these cultural differences on the validity of the differentiation of self hypothesis. This necessitates empirical research in Japan on the differentiation of self hypothesis, but to date there have been few such studies.

1.5. Differentiation of Self Scale

1.5.1. The Need to Develop a Differentiation of Self Scale in Japan

To amass empirical research on the differentiation of self hypothesis in Japan, as has been done abroad, it is necessary to construct a differentiation of self scale that can be used in Japan. This is because the empirical research collected abroad is said to be underpinned by the development of scales with high reliability and validity, such as Skowron and Friedlander’s (1998) Differentiation of Self Inventory (DSI) (Miller, Anderson, & Keala, 2004) .

However, a scale created abroad cannot simply be translated and put to use; it is more desirable to create a scale particular to Japan. As stated previously, it has been suggested that cultural differences will affect the differentiation of self hypothesis. Therefore, to closely investigate differentiation of self, it is necessary to create a differentiation of self scale within Japan’s cultural context. The creation of this scale should be based on the following 3 conditions.

1.5.2. Three Conditions for Creating a Differentiation of Self Scale

First, a differentiation of self scale should correspond to the two domains of differentiation. As previously stated, it has been suggested that cultural differences will affect the differentiation of self hypothesis. With that in mind, a subscale composition developed abroad is not necessarily valid in Japan. However, one of the fundamental qualities of differentiation of self is that it is composed of both intrapsychic and interpersonal differentiation. Thus, it is necessary to create a scale that clearly corresponds to this.

Second, the content of the scale items must be applicable to all of adolescence. As previously stated, differentiation of self is a concept deeply related to adolescence. However, the age range of adolescence has been widening due to an earlier start and later ending. It is necessary to be able to use the scale at all ages of this prolonged adolescence. Therefore, question items must use expressions that are understandable to those in the younger stages of adolescence. Furthermore, content that does not necessarily apply to adolescents should not be included, such as spousal relationships.

Third, there should not be too many items on the scale. This is in consideration of how the scale is used, as it is often used in conjunction with other scales. To make the scale usable for younger populations such as high school students, it is important to consider the response burden of survey participants, and therefore necessary to limit the number of items on the scale.

1.5.3. Current Status of the Differentiation of Self Scale in Japan

Currently in Japan, available differentiation of self scales includes the Differentiation of Self Inventory (Hiraki, Kishi, Nozue, & Ando, 1998) and the Differentiation of Self Scale for Undergraduate Students (Kudo, 2017). Although these Japanese differentiations of self scales have all been tested for reliability and validity, they do not fulfill the 3 conditions described above. Hiraki et al.’s (1998) Differentiation of Self Inventory is composed of 6 subscales and provides a broad view on various aspects of differentiation of self. However, it does not focus on intrapsychic differentiation. Kudo’s (2017) Differentiation of Self Scale for Undergraduate Students has 3 subscales and for 1 of these, the correspondence with the two domains is unclear. As it was created with the premise of targeting undergraduate students, it includes question items considered fairly difficult to understand for young people such as high school students. To gather empirical research on differentiation of self in Japan, it is necessary to create a scale that fulfills the 3 conditions described above.

1.6. Purpose

In this study, I composed a differentiation of self scale that considered the following 3 conditions: it is composed of subscales that correspond to the 2 domains of differentiation of self, the item content can be used with all ages of adolescents, and the number of items is restricted as much as possible. I then tested its reliability and validity.

This study’s results are expected to contribute to promoting the gathering of empirical research on the differentiation of self hypothesis in Japan.

2. Methods

2.1. Item Creation

Two texts were referenced for item creation: Bowen’s representative work Family therapy in clinical practice (Bowen, 1978) and Family evaluation (Kerr & Bowen, 1988) . In these 2 texts, Bowen describes the differentiation of self scale (Bowen, 1978: pp. 472-475; Kerr & Bowen, 1988: pp. 97-107) . Bowen mentions that it was an attempt to explain people’s various differences based on high and low differentiation of self, and rather than being an actual scale, it was a hypothetical one. The items are stated in ordinary language, and there are no scale items that would be used in actual clinical settings. However, this content undeniably portrays the various aspects of people the Bowen thought to be related to high and low differentiation of self. Therefore, in this study, items were created with reference to this section of his work.

Specifically, applicable sections from the 2 texts were first translated to Japanese and then content considered directly related to high and low differentiation of self was extracted. Next, 70 items were created for the first draft, paying attention to not using difficult-to-understand expressions so the items would be accessible even to high school students, and not using expressions that assume specific relationships, such as “lover” or “spouse” so as not to limit the respondents. Finally, the items were shown to 4 average undergraduate students (third year) majoring in psychology and their comments sought. Based on their comments, some items were revised or deleted. Through this process, a scale with 61 items was created.

2.2. Survey Participants and Survey Period and Procedures

The survey targeted undergraduate students in the Kanto region and was conducted during lecture periods, between October and November 2016. The study was explained both orally and in writing on the questionnaire coversheet, where it was made clear that responses were voluntary and participants could drop out at any time. There were no disadvantages to not participating. Personal information related to the responses would be protected, and response content would be used only for research purposes. The survey was then conducted. There were 296 participants (150 male, 144 female, 2 missing), of whom 273 (139 male, 133 female, 1 missing) provided valid responses (the validity rate of the questionnaire was 92.2%) and their average age was 20.41 (SD = 0.97).

2.3. Questionnaire

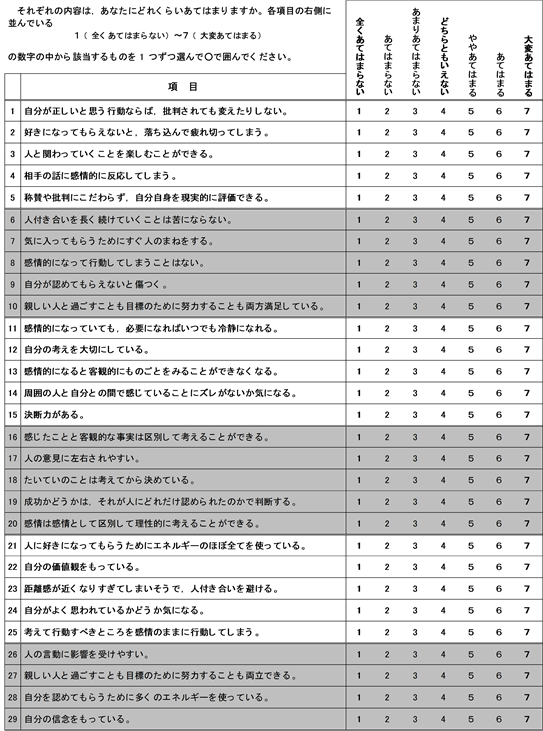

2.3.1. Differentiation of Self Scale

The study used a scale composed of the 61 items described above. Responses were given on a 7-point Likert scale (1 “does not apply at all” to 7 “greatly applies”). Respondents were asked how much each item applies to them personally.

2.3.2. Anxiety Scale

People with low differentiation of self are said to have chronically high anxiety (Kerr & Bowen, 1988: p. 115) and it is assumed that there is a significant negative correlation between differentiation of self scale scores and anxiety scale scores. Therefore, criterion-related validity was tested by verifying these assumptions. To do so, Hida, Fukuhara, Iwaki, Soga, and Spielberger’s (2000) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form JYZ (STAI) trait anxiety scale (20 items) was used. Sufficient reliability and validity has been confirmed for STAI (Hida et al., 2000) . Responses were requested on a 4-point Likert scale (1 “almost never” to 4 “almost always”).

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics for Each Item Score

The mean value of each item score was in the range 3.09 to 5.90, and the standard deviation was 0.86 to 1.72. No items caused a ceiling effect or floor effect (Table 1).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for each item score.

N = 273.

3.2. Factor Number Determination and Item Selection

Exploratory factor analysis results (maximum likelihood method and Promax rotation) suggested a 3- or 4-factor structure based on the attenuation condition of the initial eigenvalues (scree plot). Based on the concept of differentiation of self, there were some disagreements between the item content and assumed concepts of the factors on which the items loaded for the 3-factor structure. Therefore, a 4-factor structure was determined to be valid.

Next, the same factor analysis was repeated with the number of extracted factors set to 4 and removing items with factor loadings less than 0.35 or loading differences of less than 0.1 between multiple factors. Results revealed 15 items with high factor loadings as Factor 1, 11 items with high factor loadings as Factor 2, 7 items with high factor loadings as Factor 3, and 5 items with high factor loadings as Factor 4, for a total of 38 items.

With the aim of restricting the total number of scale items, items were selected considering the reliability coefficient (α coefficient) for the subscales. This resulted in 10 items with high loadings on Factor 1 (α = 0.83), 8 items with high loadings on Factor 2 (α = 0.83), and 6 items with high loadings on Factor 3 (α = 0.79). Factor 4 maintained 5 items (α = 0.75). In total, there were 29 items for the entire scale.

Finally, the factor analysis described above was performed again for the 29 items, and it was confirmed that the four-factor structure was maintained (see Table 2).

Factor 1 is composed of items such as “I care about whether people think well of me,” “I am easily influenced by others’ opinions,” and “I care about whether there is a divide felt between me and those around me.” These measure whether one is inclined to be in agreement with and accepted by others and to maintain relationships with them, and are items with content corresponding to togetherness within interpersonal differentiation. Therefore, Factor 1 was named the “interpersonal differentiation togetherness factor” and the subscale composed of these items was the “interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale”.

Factor 2 is composed of items such as “I am able to distinguish emotions as emotions and think rationally,” and “Even when I become emotional, I can calm down whenever necessary.” These are items with content corresponding to balance between thoughts and emotions, or in other words, intrapsychic differentiation. Therefore, Factor 2 was labeled the “intrapsychic differentiation factor” and the subscale composed of these items was the “intrapsychic differentiation scale”.

Factor 3 is composed of items such as “I have my own beliefs” and “When I act based on what I believe is correct, I do not change my actions even if I am criticized.” These measure whether one has one’s own ideas and can act autonomously without being swayed by others’ criticism, and these items have content corresponding to individuality within interpersonal differentiation. Therefore, Factor 3 was labeled the “interpersonal differentiation individuality factor” and the subscale composed of these items was the “interpersonal differentiation individuality scale”.

Factor 4 is composed of items such as “Continuing to socialize for a long time does not bother me” and “I am able to both spend time with someone I am close with and strive for my goals.” These measure whether one is able to smoothly manage interactions with others while simultaneously striving for personal goals, which is the opposite of devoting oneself only to maintaining interpersonal relationships or immersing oneself in interpersonal relationships. In the differentiation of self hypothesis, this is considered to be an adaptive interpersonal relationship. Therefore, Factor 4 was labeled the “adaptive interpersonal relationship factor” and the subscale composed of these items was the “adaptive interpersonal relationship scale”.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis results.

N = 273. (R) indicates a reverse item, and the loading value is the amount after reversal.

For calculations of reliability coefficients (α coefficient) and subsequent analysis, some item scores were reversed so that high scores for each subscale would correspond to high differentiation of self. Thus, high scores on the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale indicate high differentiation of self, despite the concept name suggesting the opposite.

The scale created using the processes described above was named the Differentiation of Self Scale in Two Domains (DSS-2D) (see Appendix).

3.3. Descriptive Statistics for Each Subscale Score and Normality and Correlation

The mean value and standard deviation of each subscale score are shown in Table 3. To investigate the normality of the distribution of each score, the Shapiro-Wilk’s significance probability was determined, and only the adaptive interpersonal relationship scale failed to show a normal distribution at a 5% level. Correlations among subscale scores are shown in Table 4. With the exception of the correlation between the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale and the adaptive interpersonal relationship scale, all others showed a significant correlation at a 1% level.

3.4. Gender Differences for Each Subscale Score

A t-test conducted to investigate the gender difference for each subscale score revealed no significant difference in any subscale (Table 5).

3.5. Criterion-Related Validity

To investigate the scale’s criterion-related validity, the correlation between each

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for subscale scores and Shapiro-Wilk’s significance probability.

N = 273. The scale score is the sum of item score divided by the number of items.

Table 4. Correlations among DSS-2D subscale scores.

N = 273. **Correlation is significant p < 0.01 level.

Table 5. Gender differences in subscale scores.

Table 6. Correlations between DSS-2D sub-scales and trait anxiety.

aN = 151. bN = 152. ***Correlation is significant p < 0.001 level.

subscale score and trait-anxiety scale scores was found. As there was no gender difference in any of the subscale scores, this analysis was conducted without regard to gender. Additionally, in the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale, 1 clear outlier on the scatter plot was confirmed. An analysis was therefore conducted excluding this data point. Results showed that for all subscale scores, there was a significant negative correlation at a 0.1% level (Table 6).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this research was to create a differentiation of self scale with 3 conditions in mind and to test the reliability and validity of this scale. Overall, this aim can be considered to be achieved.

The first condition was for the scale to correspond to the two domains of differentiation of self. In this study, subscales were created to correspond to each differentiation domain and this condition was met. The intrapsychic differentiation scale alone corresponds to differentiation in the intrapsychic domain, while 3 subscales, the interpersonal differentiation individuality scale, interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale, and adaptive interpersonal relationship scale, correspond to differentiation in the interpersonal domain.

Differentiation in the interpersonal domain refers to the balance between individuality and togetherness. The interpersonal differentiation individuality scale and the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale properly correspond to these two. Balance between individuality and togetherness, unlike the balance between thoughts and emotions, is difficult to express in one simple sentence, and therefore, two subscales were created corresponding separately to individuality and togetherness.

The adaptive interpersonal relationship scale, however, is considered to measure aspects that are somewhat different from the interpersonal differentiation individuality scale and the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale. The correlation among subscales suggested that this subscale measures aspects that differ specifically from the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale. This subscale corresponds to interpersonal differentiation; however, its item content does not directly express individuality or togetherness. It can be said that items showing this content correspond to adaptive interpersonal relationships in the differentiation of self hypothesis. This is a state that can be achieved by someone with high interpersonal differentiation and a state in which one can enjoy interpersonal relationships without retreating from them and can work toward achieving their goals without getting completely immersed in interpersonal relationships. The adaptive interpersonal relationship scale may be considered a more indirect scale for measuring differentiation of self compared to the interpersonal differentiation individuality scale and the interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale in the sense that it does not directly express individuality and togetherness.

The second condition was for item content to be accessible for all ages of adolescence. During the item-creation stage, this meant avoiding the use of difficult-to-understand expressions and items such as asking about spousal relationships.

The third condition was to restrict the number of items as much as possible. In total, there are 29 items on the DSS-2D; however, as a scale composed of 4 subscales, this is by no means a large number of items, and this condition can be considered to be met.

Reliability and validity were also shown. Reliability coefficients were found for each subscale: interpersonal differentiation togetherness scale (10 items) α = 0.83, intrapsychic differentiation scale (8 items) α = 0.83, interpersonal differentiation individuality scale (6 items) α = 0.79, and adaptive interpersonal relationship scale (5 items) α = 0.75. Compared to the other 2 subscales, the interpersonal differentiation individuality scale and the adaptive interpersonal relationship scale had somewhat lower values. However, these values can be regarded as sufficient considering the number of items. Validity was confirmed through the relationship with trait anxiety. A significant negative correlation was found between differentiation of self and trait anxiety scores. This supports the hypothesis described above. Based on these results, we can say that criterion-related validity for DSS-2D was shown in one respect.

5. Conclusion

In Japan, there have not been differentiation of self scales fulfilling the following 3 conditions: composed of subscales that correspond to the 2 domains of differentiation of self, item content that can be used with all ages of adolescents, and as few items as possible. In this study, a scale which fulfills the 3 conditions, named DSS-2D, was developed. The reliability coefficients and the criterion-related validity were confirmed. The results generally support the future utility of DSS-2D.

This study contributes to studies on the differentiation of self hypothesis in Japan in that it developed the DSS-2D scale. It is hoped that the development of DSS-2D will contribute to promoting the gathering of empirical evidence on the differentiation of self hypothesis in Japan.

6. Limitations and Future Challenges

This study’s limitations and future challenges include the following.

First, there should be an additional criterion-related validity investigation and test-retest reliability should also be investigated. In this study’s criterion-related validity investigation, only 1 criterion (trait anxiety) was used, and no specialized investigations were performed for each of the differentiation domains. In the future, it will be necessary to select multiple criteria for each differentiation domain and investigate each domain. For reliability, this study only examined internal consistency (α coefficient). In the future, it will be necessary to investigate the test-retest reliability showing scale stability over time. Additionally, this study was unable to confirm normality for the adaptive interpersonal relationship scale. Based on what can be seen in score distribution, it is unlikely that deviations from normality will appear as an immediate effect of usage. However, in future studies, it is necessary to continue this investigation of normality.

Second, the survey subject size should be increased. Survey subjects in this study were all undergraduate students. Therefore, at the present moment, it is not possible to affirm that the DSS-2D can actually be utilized with all ages of adolescence based on this study’s results. In the future, it is necessary to conduct a survey with subjects outside the age range of undergraduate students and to continue to accumulate DSS-2D reliability and validity verification results.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP16K04294.

Cite this paper

Kudo, K. (2018). A Differentiation of Self Scale in Two Domains for Japan: A Preliminary Study on Its Development and Reliability/Validity. Psychology, 9, 745-759. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2018.94047

References

- 1. Bowen, M. (1978). Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. New York: J. Aronson. [Paper reference 3]

- 2. Choi, S.-W., & Murdock, N. L. (2017). Differentiation of Self, Interpersonal Conflict, and Depression: The Mediating Role of Anger Expression. Contemporary Family Therapy, 39, 21-30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-016-9397-3 [Paper reference 1]

- 3. Erikson, E. H. (1995). Childhood and Society. UK: Vintage. (Original Work Published 1950, New York: W. W. Norton). [Paper reference 1]

- 4. Gushue, G. V., & Constantine, M. G. (2003). Examining Individualism, Collectivism, and Self Differentiation in African American College Women. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 25, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.25.1.hagbhguehtb9xkah [Paper reference 1]

- 5. Havighurst, R. J. (1948). Developmental Tasks and Education. New York: Longmans, Green. [Paper reference 1]

- 6. Hida, N., Fukuhara, M., Iwaki, M., Soga, Y., & Spielberger, C. D. (2000). New Edition STAI Manual: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form JYZ. Tokyo: Practical Education Publishing. [Paper reference 2]

- 7. Hiraki, N., Kishi, K., Nozue, T., & Ando, Y. (1998). Trial to Develop a Differentiation of Self Inventory: For Understanding Multi-Generational Family Relationships. Research-Aid Paper of the Yasuda Life Welfare Foundation, 34, 144-151. [Paper reference 2]

- 8. Jankowski, P. J., Hooper, L. M., Sandage, S. J., & Hannah, N. J. (2013). Parentification and Mental Health Symptoms: Mediator Effects of Perceived Unfairness and Differentiation of Self. Journal of Family Therapy, 35, 43-65.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00574.x [Paper reference 1]

- 9. Kerr, M. E., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family Evaluation: An Approach Based on Bowen Theory. New York: W. W. Norton. [Paper reference 6]

- 10. Kudo, K. (2017). Development of a Differentiation of Self Scale for Undergraduate Students: Examining Its Reliability and Validity. Bulletin of Tokyo Gakugei University, Division of Educational Sciences, 68, 215-224. [Paper reference 2]

- 11. Lampis, J. (2016). Does Partners’ Differentiation of Self Predict Dyadic Adjustment? Journal of Family Therapy, 38, 303-318. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12073 [Paper reference 1]

- 12. Miller, R. B., Anderson, S., & Keala, D. K. (2004). Is Bowen Theory Valid? A Review of Basic Research. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 30, 453-466.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01255.x [Paper reference 1]

- 13. Skowron, E. A., & Friedlander, M. L. (1998). The Differentiation of Self Inventory: Development and Initial Validation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45, 235-246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.235 [Paper reference 1]

Appendix. Differentiation of Self Scale in Two Domains (DSS-2D)