Advances in Chemical Engineering and Science

Vol.05 No.03(2015), Article ID:58371,18 pages

10.4236/aces.2015.53040

Radiative Heat Transfer and Thermocapillary Effects on the Structure of the Flow during Czochralski Growth of Oxide Crystals

Reza Faiez*, Yazdan Rezaei

Solid State Lasers Department, Laser & Optics Research School, Tehran, Iran

Email: *rfaiez@gmail.com

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 22 June 2015; accepted 24 July 2015; published 28 July 2015

ABSTRACT

A numerical study was carried out to describe the flow field structure of an oxide melt under 1) the effect of internal radiation through the melt (and the crystal), and 2) the impact of surface tension-driven forces during Czochralski growth process. Throughout the present Finite Volume Method calculations, the melt is a Boussinnesq fluid of Prandtl number 4.69 and the flow is assumed to be in a steady, axisymmetric state. Particular attention is paid to an undulating structure of buoyancy-driven flow that appears in optically thick oxide melts and persists over against forced convection flow caused by the externally imposed rotation of the crystal. In a such wavy pattern of the flow, particularly for a relatively higher Rayleigh number , a small secondary vortex appears nearby the crucible bottom. The structure of the vortex which has been observed experimentally is studied in some details. The present model analysis discloses that, though both of the mechanisms 1) and 2) end up in smearing out the undulating structure of the flow, the effect of thermocapillary forces on the flow pattern is distinguishably different. It is shown that for a given dynamic Bond number, the behavior of the melt is largely modified. The transition corresponds to a jump discontinuity in the magnitude of the flow stream function.

, a small secondary vortex appears nearby the crucible bottom. The structure of the vortex which has been observed experimentally is studied in some details. The present model analysis discloses that, though both of the mechanisms 1) and 2) end up in smearing out the undulating structure of the flow, the effect of thermocapillary forces on the flow pattern is distinguishably different. It is shown that for a given dynamic Bond number, the behavior of the melt is largely modified. The transition corresponds to a jump discontinuity in the magnitude of the flow stream function.

Keywords:

Numerical Simulation, Fluid Flow, Radiative Heat Transfer, Thermocapillary Forces, Czochralski Method, Oxides

1. Introduction

Refractory oxide crystals such as gadolinium gallium garnet (GGG) and yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) are widely used as solid-state laser hosts and materials for epitaxial films in magneto-optical devices [1] [2] . As the most commonly used technique, garnet crystals are grown by Czochralski (Cz) method mainly characterized by hydrodynamics of the melt which is inextricably coupled to transport phenomena in this configuration. Motions relevant to the Cz melt can be classified by the principal of driven forces into the following main groups: 1) gravitational (natural convection), 2) mechanical (forced convection) and 3) surface tension (Marangoni convection). These different kinds of the melt motion are quite complex and their intensity and interaction determine the flow structure, the heat and mass transport, the shape of crystal/melt interface and consequently the quality of the crystal [3] . Defect formation in the crystal as well as spiral growth of oxides are strongly influenced by convective flow and its instabilities [4] - [6] .

Accounting for the internal radiation within the melt and crystal is of crucial importance in numerical modeling of Cz growth of oxides because they are often semitransparent to infrared radiation [7] [8] . Radiative heat transfer (RHT) strongly couples with the melt dynamic and, as demonstrated by Xiao and Derby [9] , considerably affects the interface shape. Their model, however, approximated the internal radiation through the crystal being totally transparent and so could not be provide an explanation of the effect of optical properties of the crystal. Furthermore, the melt was assumed to be opaque and consequently did not participate in the radiative heat transfer in the model.

Tsukada et al. [10] have developed a global analysis of heat transfer in the Cz oxide growth system in which the influence of the optical properties of both the melt and the crystal on the interface morphology has been studied. In their model, however, forced convection flow and thermocapillary effect was neglected. Recently, much progress has been made in understanding the effect of internal radiation on the thermal convective pattern generated at the melt free surface for which the Marangoni instability is an indispensable factor [10] [11] . Jing et al. [12] have numerically revealed that when the internal radiation was ignored, a spoke pattern was generated and the bulk melt flow was oscillatory; the pattern disappeared when the melt assumed to be semitransparent. These computational efforts were generally based on three-dimensional modeling of Cz oxide melt in an open crucible and consequently all effects attributed to the crystal, including its optical properties, were ignored. More recently, Budenkova et al. [13] have reported the results of a two dimensional, axisymmetric modeling of the Cz growth of Gd3Ga5O12(GGG) and Tb3Ga5O12(TGG) crystals. In contrast to GGG, the authors in [13] concluded that the heat transfer in TGG can be described within the model of opaque crystal of thermal conductivity in the range 3.5 - 5.0 W∙m−1∙K−1. For both of the cases, the melt was assumed to be opaque, and the thermocapillary effect as well as the meniscus influence on the crystal/melt interface was ignored.

In this paper, we report the results of a numerical simulation of the Czochralski growth of a large-diameter GGG crystal. The main subject of the present model calculations is, in a first step, to explain the effect of internal radiation on the flow and thermal fields. The results obtained for semitransparent material are compared with the case in which both the melt and the crystal are assumed to be opaque to the thermal radiation. The convective behavior of the melt is discussed, and it is shown that the thermal stratification of the fluid depends on the intensity of buoyant forces in optically thick melt. The undulating pattern of the thermal field disappears with contribution of the internal radiation in heat transfer in the melt. Throughout the first step, thermocapillary flow is neglected.

In the second step, the material is assumed to be opaque, and the radiative heat exchange occurs between exposed surfaces in the Cz enclosure. The structure and properties of a small vortex which appears in the melt of high Rayleigh number is studied. It is shown that there is a critical thermocapillary coefficient at which the undulating structure [14] of the flow and, consequently the small vortex near the crucible bottom disappears. The transition of the flow pattern corresponds to a jump discontinuity in the magnitude of the flow stream function.

2. Model Description

The Cz growth system can be characterized by coexisting vertical and horizontal temperature gradients and the differential rotation rates of the crystal and crucible. The general feature of the fluids motion in the Cz crucible is described as follows. The buoyancy-driven hot flow ascends along the crucible wall and then accompanied by the surface/tension-driven flow, travels along the melt free surface towards the crystal rim. The fluid is being cooled down along the path and more intensively adjacent to the crystal/melt interface (CMI) due to the larger heat conductivity of the oxide crystal. This creates a stream of cold fluid which descends along the centerline towards the crucible bottom. If the crucible is at rest and the crystal rotation rate is sufficiently low, the flow is essentially buoyancy driven with a unicellular meridional circulation, namely the Hadley cell circulation [15] , with a small zonal flow driven by the crystal rotation. The crystal rotation drives a flow which streams upward below the crystal, outward along the meniscus, and down along the boundary between the Hadlay cell circulation and the forced convection cell. The shear layer between the buoyancy and rotationally driven cells, known as a Stewartson layer [16] , is characteristic of rotating fluids. Considerable effort has expended to ensure that, depending on the Rayleigh number, the flow in a side-heated cavity similar to Cz melt, displays two-dimen- sional axisymmetric behavior. As well, it is believed that secondary vortices which appear in the convective flow of high Rayleigh number cannot be attributed to an instability of base flow but are a direct consequence of convective distortion of the thermal field [17] .

In the model, the crystal pulling rate is, as usual, much smaller than the characteristic velocity of the buoyancy-driven flow. Therefore, the system is assumed to be in a quasi-steady state. In the melt model, the fluid motion is substantially determined by the natural convection for which the Rayleigh number does not exceed the relevant critical value estimated for relatively high Prandtl number fluids [17] [18] . Therefore, the assumption of axisymmetric transport processes in the melt can be justified. Furthermore, the significant mechanisms of instability in Cz melt model arise because of the non-linear interaction of rotational and buoyant flows to which the temperature field is strongly coupled. Therefore, axisymmetric behavior is expected for the melt model without an intense swirl.

In the present modeling of Cz-oxide growth process with bulk radiation incorporated in the governing equations, the influence of thermal convections on the flow pattern is studied. The externally imposed rotational effect is, however, assumed to be secondary in the present analysis. The crystal rotation, when accounted for in the melt, breeds a small zonal flow beneath the CMI. For experimentally reasonable rates of rotation, the flow pattern remains almost unchanged.

2.1. Physical Model

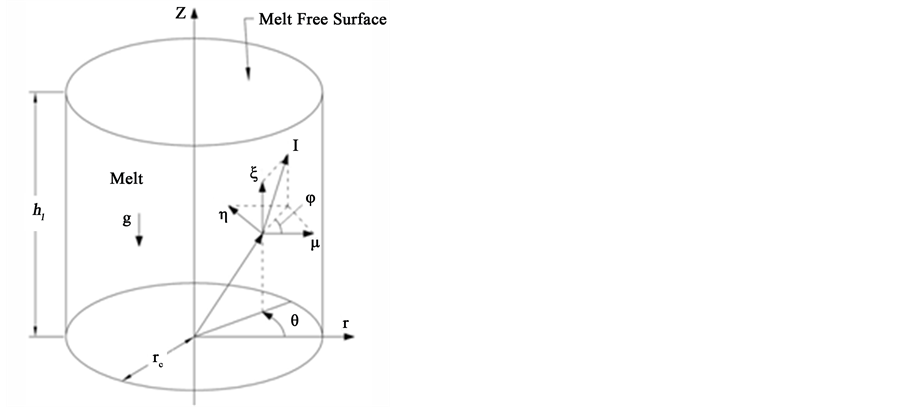

The schematic in Figure 1(a) illustrates that the configuration adopted in the present analysis consists of a crucible of radius  and height

and height , the oxide melt of height

, the oxide melt of height , the cylindrical shape crystal of curved shoulder and with dimensions

, the cylindrical shape crystal of curved shoulder and with dimensions  and

and , the ambient gas and enclosure of height

, the ambient gas and enclosure of height  and radius

and radius . The

. The

Figure 1. (a) Schematic diagram of the Czochralski growth configuration; (b) non-uniform finite differential mesh used for calculations.

melt aspect ratio  is equal to unity and the ratio of radii

is equal to unity and the ratio of radii . Corresponding to the crystal volume,

. Corresponding to the crystal volume,  is a reasonable height of crucible expose wall. Because the meniscus configuration at the crystal edge directly affects the contact area between the fluid and the crystal, its influence is taken into account in the numerical simulation. As shown in Figure 1(a), some of this area is almost vertical and consequently allows for radial heat transfer (both convective and radiative) from the melt to the surrounding near the CMI. In the vicinity of the crucible wall, however, a right angle contact is assumed.

is a reasonable height of crucible expose wall. Because the meniscus configuration at the crystal edge directly affects the contact area between the fluid and the crystal, its influence is taken into account in the numerical simulation. As shown in Figure 1(a), some of this area is almost vertical and consequently allows for radial heat transfer (both convective and radiative) from the melt to the surrounding near the CMI. In the vicinity of the crucible wall, however, a right angle contact is assumed.

The mathematical model developed here, incorporates transport process in the melt and the crystal. In the ambient gas phase, assumed to be totally transparent to the thermal radiation, only the energy equation is solved. The semitransparent phases are bounded to diffuse-gray surfaces and, according to the spectroscopic measurements of the refractory oxides optical properties [19] , the optical thickness of the melt is taken to be larger than that of the crystal. For most of the calculations performed here, the thermophysical properties of GGG, reported just recently by IKZ-Berlin [20] , are employed. The physical properties of the two phases of the Cz domain are given in Table 1. For theoretical purpose, however, two parameters ( and

and ) are allowed to take different values within a reasonable range of data reported for oxides. The geometrical and growth parameters used in the present study are listed in Table 2. The common non-dimensional groups which characterize the melt behavior in the Cz/GGG configuration are given and compared with those of YAG in Table 3.

) are allowed to take different values within a reasonable range of data reported for oxides. The geometrical and growth parameters used in the present study are listed in Table 2. The common non-dimensional groups which characterize the melt behavior in the Cz/GGG configuration are given and compared with those of YAG in Table 3.

Table 1. Thermophysical properties, including optical data [20] , employed in calculation; the subscripts l, x, a, c and k denote melt, crystal, air, crucible and insulating enclosure, respectively.

e: Estimated values.

Table 2. Geometrical and process parameters used for calculations.

Table 3. Dimensionless parameters of the garnet oxide GGG and YAG melts for the same characteristic length

2.2. Basic Assumption

The fluid flow for the melt region is described by coupled Navier-stokes and heat equations. The present model involves the following assumption: 1) the melt is an incompressible Newtonian fluid which satisfies the Boussinesq approximation; 2) the fluid flow is laminar; 3) viscous dissipation is negligible; 4) the melt/gas interface is not calculated from the Young-Laplace equation, but instead, following Galazka et al. [21] , an appropriate curvature of the melt free surface has been assumed so that, it provides the melt meniscus at the crystal rim; 5) the constant angle is equal to the equilibrium growth angle of the garnet crystals; 6) the crucible bottom is thermally insulated and its side walls are at a uniform and constant temperature,

To estimate the contribution of the internal radiation to heat transfer in the melt, the crystal and melt are assumed to be absorbing/emitting mediums bounded by vanishingly thin semitransparent diffuse gray surfaces. As a disposal parameter [7] [10] the optical thickness of the melt,

3. Numerical Approach

A finite volume method (FVM) is applied to compute quasi-steady and axisymmetric solutions to the fully coupled equations governing heat transfer and melt hydrodynamics for Czochralski growth of garnet oxide GGG crystal. The radiative heat transfer strongly couples with fluid dynamics [7] - [10] . Therefore, an accurate modeling of the Cz/GGG configuration requires a simultaneous solution of the radiative transfer equation and the fluid dynamics equations. This means that numerical procedure used for the radiative transfer must be compatible with the transport equations for other processes. During the last decade, different methods have been developed to solve the radiative transfer equation for refractory oxides growth systems. The PN-approximation which expands the radiation intensity by an orthogonal series of spherical harmonics [22] is widely used in its simplest form, i.e. the P1-approximation. Numerically, it has been shown, however, that the computational methods based on the P1-approximation is valid only for optically thick materials [23] . This means that with increasing the contribution of internal radiation to heat transfer, or decreasing the conduction/radiation ratio

As given in Table 3, the Planck number of garnet oxide melts is low

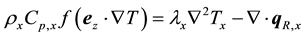

3.1. Governing Equations

The equations describing the conservation of mass, momentum and energy for the two-dimensional (2D) model represented and restricted in the preceding sections, are expressed as follows.

where

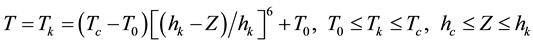

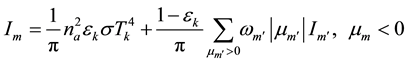

To estimate the radiative heat flux

We consider the radiative heat transfer for the axisymmetric system (the melt and crystal) depicted in Figure 2. Based on the DO method, the balance of energy passing in a specified direction

where

where

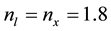

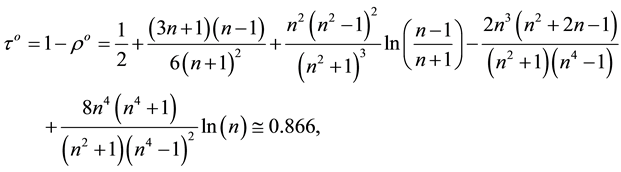

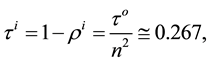

In the present work, the optical properties on both sides of the semitransparent mediums (the crystal and the melt) surfaces are estimated with their refractive indices [26] [27] ,

where

Figure 2. Coordinate system used.

In the Cz configuration Figure 1(a), each material constituting the system, such as the melt, the crystal and the crucible expose wall, is surrounded by a transparent gas, and the incident radiative heat flux to their surfaces through the ambient gas, is partially absorbed and reflected but not transmitted if the material is opaque. In this case, the emissivity of the melt into the ambient phase can be estimated as

3.2. Boundary Conditions

The velocity boundary conditions are

o the melt free surface where boundary conditions can be expressed by components as

if thermocapillary convection is taken into account

o at the crystal walls and the crystal/melt interface

o at the melt centerline

For any variable

o At the melt free surface:

o at the sidewall of the crystal:

o at the crystal/melt interface:

o at the insulating enclosure wall:

o at the top enclosing surface:

o at the crucible submerged wall:

o at the crucible bottom:

o at the exposed portion of crucible wall:

o at the centerline:

where subscripts

The governing equations with boundary conditions for the fluid flow and heat transport in the system were numerically solved by employing control volume (CV) based finite differential technique. The SIMPLEC algorithm [30] was used to couple velocities and pressure on staggered grids, and second order upwind method was used for discretization of momentum and energy equations. The equations are integrated over each CV and the resulting system of algebraic equations is solved iteratively until convergence is reached. Figure 1(b) provides a sample of non uniform mesh layout used in the present simulations. The cell number for both the melt and the

crystal sums up 13,806 (each with area

4. Results

The present section is divided into two parts: 1) the results which explain the effect of internal radiation transfer on the convective flow and thermal fields in the melt dominated by the buoyancy forces the intensity of which is respected by the Rayleigh number Ra, and 2) the results which reveal the influence of thermocapillary forces on the convective pattern in the melt when the material does not participate in the radiative heat transport. For the cases in which the internal radiation is ignored the boundary conditions for temperature and radiative transfer between the exposed opaque surfaces, are expressed as given in reference [12] . The reliability and accuracy of the present simulation was ascertained by validating the general results of calculations with numerical results of the convection in the Cz/oxide melt [8] [9] . Comparison was made with the results obtained by Hintz et al. [28] [31] for a Cz melt (Pr = 6.8) simulated in a model experiment. The present numerical results were found to be in a good agreement with the results in literature for opaque and/or semitransparent Cz/oxide melts.

The convective behavior of GGG melt in the model can be characterized by the dimensionless similarity parameters given and compared to YAG melt in Table 3. However, to investigate 1) the effect of internal radiation on the buoyancy-driven flow, and 2) the influence of Marangoni convection on the flow field pattern, calcula-

tions were carried out for opaque system with

4.1. The First-Step Results

The numerical simulations of the opaque

Stratification of the Melt and Radiative Heat Transport

It is well known [32] [33] that for an incompressible fluid, buoyancy forces can give rise to internal gravity waves if the fluid is a stratified medium. According to linear theory, instability of a shear flow can only occur if the Richardson number,

form of the non dimensional parameter is given by

Table 4. Flow velocity components (mm/s) and the magnitude of

Figure 3. Flow pattern (a), temperature distribution (b) and velocity field (c) in the opaque (left) and semitransparent (right) melt

As shown in Figure 3(b), the optically thick melt is a thermally stratified medium. The effect of optical properties on the flow pattern is shown in Figure 3(a). The comparative simulation of the melt behavior describes that, in contrast to the semitransparent melt, the opaque melt exhibits an undulating structure near the crucible bottom due to a retarding force caused by vertical stratification of the fluid. Within the surveyed range of

Figure 3(c) shows how large the internal radiative transfer affects the velocity field pattern. Though the components of the field, with the exception of

melt (C1). For each value of the Rayleigh number

significantly different for two optically distinguished cases C1 and C2. More precisely, it is anticipated that, for opaque melt

To describe the details relevant to the discussion, Figure 4(a) and Figure 4(b) show the temperature variations along the vertical

The vortex (named RFV hereafter) appears only in the opaque melt and its center, located at the point

Figure 4. Temperature variation along the (a) vertical and (b) horizontal lines, including the vortex diameters,

Radial velocity profile along the vertical

Figure 5 to observe the eventual implication of Rayleigh-Fjørtoft’s necessary (but not sufficient) condition of instability [32] in the opaque melt. The condition is expressed as

4.2. The Second-Step Results

This section is assigned to description of 1) the properties of the small secondary vortex (RFV) which appears in the optically thick melt model and 2) the role of thermocapillary forces on the flow field structure which lead to similar results on the fluid motion as the radiative transfer.

In this section, the melt is assumed to be opaque. For the present steady and axisymmetric model, the streamlines are defined in terms of the velocity components as

4.2.1. Structure and Properties of the Vortex

It has been shown [34] that for two dimensional, steady motion of an incompressible fluid of constant viscosity

The area of the normal cross-section of the vortex tube is approximated by

Figure 5. Radial velocity profile along the line

shown [34] that an elliptical patch of uniform vorticity

For the case

the boundary,

Contrarily, at the lower edge, around the point A, viscous dissipation has the lowest effect. Note that, vorticity intensification due to stretching of vortex lines, does not occur in the present 2D model.

Within the surveyed range of

Increasing the Rayleigh number, the non-uniformity of the vorticity distribution on the closed

flow (not shown here) and, as shown in Figure 7, the ratio

4.2.2. Thermocapillary Forces and Vortex Merging

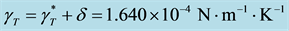

Surface tension gradient,

Figure 6. Stream function and vorticity plotted along (a) the vertical and (b) the horizontal lines

Figure 7. Dependence of geometrical properties of vortex tube on the intensity of buoyancy-driven flow in the melt (

stratification in the vicinity the melt free, is removed in the presence of thermocapillary flow. The effect, as expected, depends on the intensity of Ma-flow or more precisely, on the ratio of the boundary to surface tension forces represented by

where

To investigate the influence of thermocapillary forces on the flow pattern in the present optically thick melt of

Figure 8. Flow pattern (a), temperature distribution (b) and velocity field (c) in the melt (

ven forces on the melt behavior is significantly different for two cases of

In the case with

For a negligibly small increment of the thermocapillary forces, that is, for

For two cases of

Figure 10 displays that, in an optically thick melt of

Figure 9. Radial velocity profile along the line

Figure 10. Abrupt change in the magnitude of

value

This can be inferred that more energy is stored in the wavy structure of the flow by increasing the Rayleigh number of the melt. The small secondary vortex (RFV) volume

5. Summary and Conclusions

Two-dimensional axisymmetric simulations of the Navier-stokes equations were used to investigate the behavior of the melt under a) the effect of internal radiative transfer and b) the influence of thermocapillary forces, during Cz growth of GGG crystals.

The results indicated that the two different mechanisms end up, however, in a similar pattern of the flow in the interior of the melt: the undulating structure of the flow, caused by vertical stratification of the melt, was smeared out when the melt assumed to be semitransparent (case C1) and/or when the surface tension coefficient

The wavy pattern of the flow found to be enhanced with increasing in the intensity of convective flow

The properties of an elliptical-shape secondary vortex (RFV) which appears in the interior of the opaque melt of

center

In the presence of thermocapillary forces

Cite this paper

RezaFaiez,YazdanRezaei, (2015) Radiative Heat Transfer and Thermocapillary Effects on the Structure of the Flow during Czochralski Growth of Oxide Crystals. Advances in Chemical Engineering and Science,05,389-407. doi: 10.4236/aces.2015.53040

References

- 1. Fei, Y.T., Chou, M.M.C. and Chai, B.H.T. (2002) Crystal Growth and Morphology of Substituted Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. Journal of Crystal Growth, 240, 185-189.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(02)00876-X - 2. Jia, Z., Tao, X., Dong, C., Cheng, X., Zhang, W., Xu, F. and Jiang, M. (2006) Study on Crystal Growth of Large Size Nd3+: Gd3Ga5O12 (Nd:GGG) by Czchralski Method. Journal of Crystal Growth, 292, 386-390.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2006.04.041 - 3. Polezhaev, V.I. (2003) Modeling of Technically Important Hydrodynamics and Heat/Mass Transfer Processes during Crystal Growth. In: Scheel, H.J. and Fukuda, T., Eds., Crystal Growth Technology, John Wiley, Chichester, 155-186.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0470871687.ch8 - 4. Wilke, H., Crnogorac, N. and Cliffe, K.A. (2007) Numerical Study of Hydrodynamic Instabilities during Growth of Dielectric Crystals from the Melt. Journal of Crystal Growth, 303, 246-249.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2006.10.151 - 5. Uecker, R., Wilke, H., Schlom, D.G., Velickov, B., Reiche, P., Polity, A., Bernhagen, M. and Rossberg, M. (2006) Spiral Formation during Czochralski Growth of Rare-Earth Scandates. Journal of Crystal Growth, 295, 84-91.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2006.07.018 - 6. Lan, C.W. and Tu, C.Y. (2001) Three-Dimensional Simulation of Facet Formation and the Coupled Heat Flow and Segregation in Bridgman Growth of Oxide Crystals. Journal of Crystal Growth, 233, 523-536.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(01)01599-8 - 7. Tsukada, T., Kobayashi, M. and Jing, C.J. (2007) A Global Analysis of Heat Transfer in the CZ Crystal Growth of Oxide: Recent Developments in the Model. Journal of Crystal Growth, 303, 150-155.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2006.11.344 - 8. Tsukada, T., Kobayashi, M., Jing, C.J. and Imaishi, N. (2005) Numerical Simulation of CZ Crystal Growth of Oxide. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing, 1, 45-62.

- 9. Xiao, Q. and Derby, J.J. (1994) Heat Transfer and Interface Inversion during the Czochralski Growth of Yttrium Aluminum Garnet and Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. Journal of Crystal Growth, 139, 147-157.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(94)90039-6 - 10. Tsukada, T., Kakinoki, K., Hozawa, M. and Imaishi, N. (1995) Effect of Internal Radiation within Crystal and Melt on Czochralski Crystal Growth of Oxide. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 38, 2707-2714.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0017-9310(95)00077-M - 11. Jing, C.J., Imaishi, N., Sato, T. and Miyazawa, Y. (2000) Three-Dimensional Numerical Simulation of Oxide Melt Flow in Czochralski Configuration. Journal of Crystal Growth, 216, 372-388.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(00)00427-9 - 12. Jing, C.J., Hayashi, A., Kobayashi, M., Tsukada, T., Hozawa, M., Imaishi, N., et al. (2003) Effect of Internal Radiative Heat Transfer on Spoke Pattern on Oxide Melt Surface in Czochralski Crystal Growth. Journal of Crystal Growth, 259, 367-373.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2003.07.033 - 13. Budenkova, O.N., Vasiliev, M.G., Yuferev, V.S., Ivanov, I.A., Bul’kanov, A.M. and Kalaev, V.V. (2008) Investigation of the Variations in the Crystallization Front Shape during Growth of Gadolinium Gallium and Terbium Gallium Crys- tals by the Czochralski Method. Crystallography Reports, 53, 1181-1190.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1134/S106377450807016X - 14. Kobayashi, M., Hagino, T., Tsukada, T. and Hozawa, M. (2002) Effect of Internal Radiative Heat Transfer on Interface Inversion in Czochralski Crystal Growth of Oxides. Journal of Crystal Growth, 235, 258-270.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(01)01786-9 - 15. Ristorcelli, J.R. and Lumley, J.L. (1992) Instabilities, Transition and Turbulence in the Czochralski Crystal Melt. Jour- nal of Crystal Growth, 116, 447-460.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(92)90654-2 - 16. Xiao, Q. and Derby, J.J. (1995) Three-Dimensional Melt Flows in Czochralski Oxide Growth: High-Resolution, Massively Parallel, Finite Element Computations. Journal of Crystal Growth, 152, 169-181.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(95)00090-9 - 17. Markatos, N.C. and Pericleous, K.A. (1984) Laminar and Turbulent Natural Convection in an Enclosed Cavity. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 27, 755-772.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0017-9310(84)90145-5 - 18. Jaluria, Y. and Gebhart, B. (1988) Buoyancy Induced Flows and Transport. Hemisphere, Washington DC.

- 19. Kobzev, G.A. and Petrov, V.A. (1993) Measurement of Thermal Radiation and Optical Properties of Refractory Oxi- des and Their Melts under CO2 Laser. Thermochimica Acta, 218, 291-304.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0040-6031(93)80430-I - 20. Crnogorac, N. and Wilke, H. (2009) Measurement of Physical Properties of DyScO3 Melt. Crystal Research and Tech- nology, 44, 581-589.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/crat.200800530 - 21. Galazka, Z. and Wilke, H. (2000) Influence of Marangoni Convection on the Floe Pattern in the Melt during Growth of Y3Al5O12 Single Crystals by the Czochralski Method. Journal of Crystal Growth, 216, 389-398.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(00)00426-7 - 22. Modest, M.F. (1993) Radiative Heat Transfer. McGraw-Hill, New York, 487.

- 23. Lan, C.W., Tu, C.Y. and Lee, Y.F. (2003) Effects of Internal Radiation on Heat Flow and Facet Formation in Bridgman Growth of YAG Crystals. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 46, 1629-1640.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0017-9310(02)00454-4 - 24. Colomer, G. (2006) Numerical Methods for Radiative Heat Transfer. Diss. PhD Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona.

- 25. Liu, J., Shang, H.M. and Chen, Y.S. (2000) Development of Unstructured Radiation Model Applicable for Two-Di- mensional Planar and Three-Dimensional Geometries. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfer, 66, 17-33.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4073(99)00162-4 - 26. Spuckler, C.M. and Siegel, R. (1992) Refractive Index Effects on Radiative Behavior of a Heated Absorbing-Emitting Layer. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 6, 596-604.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2514/3.11539 - 27. Spuckler, C.M. and Siegel, R. (1994) Refractive Index and Scattering Effects on Radiation in a Semitransparent Laminated Layer. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer, 8, 193-201.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2514/3.523 - 28. Hintz, P. and Schwabe, D. (2001) Convection in a Czochralski Crucible—Part 2: Rotating Crystal. Journal of Crystal Growth, 222, 356-364.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(00)00885-X - 29. Nunes, E.M., Naraghi, M.H.N., Zhang, H. and Prasad, V. (2002) A Volume Radiation Heat Transfer Model for Czoch- ralski Crystal Growth Processes. Journal of Crystal Growth, 236, 596-608.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(02)00826-6 - 30. Ferziger, J.H. and Peric, M. (2002) Computational Methods for Fluid Dynamic. Third Edition, Springer, Berlin, 166- 178.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-56026-2 - 31. Hintz, P., Schwabe, D. and Wilke, H. (2001) Convection in a Czochralski Crucible—Part 1: Non-Rotating Crystal. Journal of Crystal Growth, 222, 343-355.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(00)00884-8 - 32. Drazin, P.G. and Reid, W.H. (1982) Hydrodynamic Stability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 320-333.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1115/1.3162197 - 33. Fein, J.S. and Pfeffer, R.L. (1976) An Experimental Study of the Effects of Prandtl Number on Thermal Convection in a Rotating, Differentially Heated Cylindrical Annulus of Fluid. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 75, 81-112.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S002211207600013X - 34. Acheson, D.J. (1994) Elementary Fluid Dynamics. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 162-191.

- 35. Jones, A.D. (1988) Scaling Analysis of the Flow of a Low Pr Number Cz Melt. Journal of Crystal Growth, 88, 465- 476.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0248(88)90145-5

NOTES

*Corresponding author.