Sociology Mind 2012. Vol.2, No.1, 95-108 Published Online January 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/sm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/sm.2012.21013 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 95 95 African Americans in the US Women’s National Basketball Association, 2006: From the NCAA to the WNBA Amadu Jacky Kaba Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work, Seton Hall University, South Orange, USA Email: Amadu.Ka ba @shu.edu Received September 17th, 2011; revised October 25th, 2011; accepted December 6th, 2011 This research study presents a social science examination of the US Women’s National Basketball As- sociation (WNBA) players for the 2006 season. This study does not examine on-court performance data. Instead, it focuses on the profile of the players as human beings, by looking at their race, average age, height and weight, colleges or universities attended in the United States and which regions these institu- tions are located in, demographics of international players, graduation rates, etcetera. The paper also ex- amines the issue of gender bias when it comes to salaries and advertisement or endorsement opportunities. Keywords: Women’s National Basketball: USA; African American Women; Educational Attainment; NCAA; Gender and Sports Introduction African American females, like their male counterparts have been playing or participating in organized sports in the United States from the 1800s or before. Among the sports that African American females have been participating in are: Basketball, Fencing, Field Hockey, Figure Skating, Golf, Gymnastics, La- crosse, Rowing, Softball, Soccer, Swimming, Tennis, Track and Field, and Volleyball. Due to its popularity in the United States and the world, and also due to their history in the country, the relationship between African American females and Bas- ketball has been unique. That is because it is the sport that has contributed to providing college scholarships to a very large number of Black females in the past several decades. By the 21st Century, basketball is also providing African American women with jobs and advertisement opportunities, although not as large as their male counterparts (Abney, 1999; Baker, 2008; Grundy & Shackelford, 2006; McDonald, 2000; Ruihley, 2010; Spencer & McClung, 2001; Staffo, 1998a; Wearden & Creedon, 2002; Yafie, 1997). As Abney (1999) notes: “African American women have made significant contributions and set standards of excellence in every aspect of sport. Although seldom recognized and rewarded, they have excelled in many sports including tennis, golf, gymnastics, figure skating, volleyball, lacrosse, field hockey, fencing, rowing, track, and basketball. African American women have attained prominence and had successful careers as Olympians, professional and collegiate athletes, coaches, admini- strators, officials, athletic trainers, and sportscasters… African American women have had to overcome many odds, including the double jeopardy of gender an d r a ce . D u r in g t h e e a r l y 1900s, they competed during times when women were not encouraged to become athletes and African Americans were not given equal opportunities” (p. 35). The United States women’s professional basketball league, the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) is in- creasing its popularity not only in the US, but all over the world, despite the fact that the league as of 2011 has been in existence for only 15 years. Picker (2006) quoted the league’s former president, Donna Orender as saying that: “Not only is basket- ball the No. 1 participatory sport for girls in the United States, there are 100 million females playing this sport around the world… It is a global game for women as well as for men” (p. D6). Staffo (1998a) also points out that 80 million females across the world play basketball and that in the United States it was the sport most female youths play (p. 191). The purpose of this study is to take an in-depth social science examination of the players that comprised the United States Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) for the 2006 season. The study does not include statistics showing the numbers or percentages of points, assists, rebounds, etcetera of the players (Gomez et al., 2009; Kochman & Goodin, 2003). Nor does this paper include the teams that each player is on. Instead, this study focuses only on the profile of these players or in knowing their various characteristics such as their racial breakdown, colleges and universities attended, international players, their average height, weight, and age. In some in- stances, comparisons will be made with their male counterparts in the 2005-2006 US National Basketball Association (NBA). The paper begins with the methodology. Next it presents the statistical findings of the various characteristics of the players. Finally, the paper presents a discussion section with analysis of some of the data in the findings. Methodology All of the data were compiled from the official website of the WNBA (http://www.wnba.com) as of May 20, 2006, the official o pening day of the 2 006 season. The WNBA presents a profile of each of its players in alphabetical order. I printed out the profile of each player and transferred her data into an excel spreadsheet in alphabetical order. One large table was created and it contains the profiles of all the players. The variables include date of birth and age, racial background, height, weight, position played, college/university or institu- tion attended, state in the US where institution is located, region of the country (e.g. Northeast, Midwest, South and  A. J. KABA West, using US Census or government classification) where institution is located, and year of graduation for those players who attended colleges or universities in the United States. Data for salaries of WNBA players are not posted on the league’s website nor are they posted by the USA Today newspaper, which posts salary figures for the National Bas- ketball Association (NBA), their male counte rparts. However, according to Isaacson (2006): “The WNBA rookie minimum is $31,800, as opposed to nearly $400,000 in the NBA. The average WNBA salary is $50,000, as opposed to the NBA’s $4.5 million” (p. 1; also see Staffo, 1998; Cahppell & Kara- georghis, 2001). As little as their salaries are by 2006, those figures actually increased from the 1990s. For example, ac- cording to Staffo (1998a): “…WNBA salaries range from $15,000 to $50,000 excluding meal and travel money… another source described the same sliding scale but listed the minimum at only $10,000” (p. 193). Kaba (2011a) points out that the average salary of US National Basketball Association (NBA) players for the 2005-2006 season was $3.9 million (p. 7). Data for WNBA players who are foreign-born were also compiled and computed. The figures for age are as of May 31, 2006. The players are also separated into two categories based on their pictures posted on the WNBA official website: 1) Players of African decent (but referred to as Black players in this study); and 2) White players. This author, who has pub- lished extensively on the racial make-up of not only the people of the United States, but also the world, utilized the classifica- tion of various racial groups in the US to divide the players (see Kaba, 2006ab, 2011a). For example, in the US, people who are of Turkish, Arab, Jewish, Iranian, or European ancestry, are classified as White, while anyone with Black African ancestry is classified as Black or African American. And individuals from East Asia and South Asia are classified under Asian/Pacific Isl an d er s . It is useful to note that these classifications are by no means saying that is what these players are or identified themselves as. The classifications are utilized only to help us understand the racial make-up of the league. General Findings Numbers, P e rcentages and Racia l Make-Up of WNBA Players Like their male counterparts in the NBA, players of African descent or Black players comprise the majority in the US Women’s National Baske tball Association (WNBA). However, their proportion is not as high as the men. Of a list of 177 names of WNBA players on the league’s website as of 12:30 pm on May 20, 2006 (opening day of the 2006 regular season), data were not available for two players, bringing the list down to 175 players. The data in this entire section focus on these 175 players, all of whom are either categorized as Black or White (No other players from other racial groups are among those 175 total players). Of those 175 players, Black players comprised 118 (67.4%), and White players comprised 57 (32.6%) (Table 1). Lapchick and Kushner (2006) present a breakdown of WNBA players for the 1999 and 2005 seasons, utilizing cultural, instead of racial definition. They claim that in the 1999 WNBA season, African American players comprised 64%, White players, 32% and Latina players, 2%. For the Table 1. Profile of 2006 WNBA players: As of May 20, 2006. Total# of all Players#of Black Players % #of White Players% 175 118 67.4 57 32.6 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www. wnba.com, 2006. 2005 WNBA season, African American players comprised 130 (63%); White players, 69 (34%); Latina players, 2 (1%); 1 Asian player; and a group of players called “Other”, 3 (1%) (p. 13). For comparative purposes, of the 430 players in the NBA during the 2005-2005 season, 327 (76%) were Black, 101 (23.5%) were White, and 2 were Northeast Asians (Kaba, 2011a: p. 4). Average Age of All Players On average, Black players are older than White players. The average age of all 175 players was 25.9 years. The average age of the Black players was 26.2 years, and the average age of the White play ers wa s 25.3 y ear s (Ta bl e 2 ). In the NBA, during the 2005-2006 season, the average age of all 430 players was 26.5 years; 26.7 years for Blacks and 26.1 years for White players (Kaba, 2011a: p. 12). In addition, no player in the WNBA was 20 years or younger. A total of 96 players (54.9% of all players) were 21 - 25 years old. Of that total, Black players accounted for 61 (63.5%, but 51.7% of all 118 Black players, and 34.9% of all 175 players), and White players accounted for 35 (36.5%, but 61.4% of all 57 White players, and 20% of all 175 players). A total of 41 play- ers (23.4% of all players) were 26 to 29 years old. Of that total, Black players comprised 28 (68.3%, but 23.7% of all Black players, and 16% of all 175 players), and White players com- prised 13 (31.7%, but 22.8% of all White players, and 7.4% of all 175 players). A total of 37 players (21.1% of all players) were 30 years or older. Of that total, Black players comprised 28 (75.7%, but 23.7% of all Black players, and 16% of all 175 players), and White players comprised 9 (24.3%, but 15.8% of all White players, and 5.1% of all 175 players) (Table 3). Average Height of All Players Players of African descent in the WNBA are shorter on av- erage than White players. The average height of all WNBA players was 72.4 inches (over 6’0”). The average height of Black players was 72.3 inches (over 6’0”), and the average height of White players was 72.6 inches (upwards to 6’1”) (Table 4). In the NBA, during the 2005-2006 season, the aver- age height of all players was 79.2 inches (just over 6’7”); 78.6 inches (up to 6’7”) for Black players; and 81 inches (6’9”) for White players (Kaba, 2011a: p. 6). Table 2. Average age of WNBA players. All Players ( N = 175)Black Pl a yers (N = 118) White Players (N = 5 7) Average Age Average Age Average Age 25.9 (year s ) 26.2 (year s ) 25.3 (year s) Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www. nba.com, 2006. w 96 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  A. J. KABA Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 97 Table 3. Age groups of WNBA players: 2006 season. % of all % of all Item Number % of total ( 175) Blacks Whites #of All Players 20 Years Old or Younger 0 0 0 0 #of All Players 21 - 25 Years Old 96 54.9 #of All Blac k Players 21 - 25 Years O l d 61 34.9 51.7 #of All White Players 21 - 25 Years Old 35 20 61.4 #of All Players 26 - 29 Years Old 41 23.4 #of All Blac k P layers 26 - 2 9 Years Old 28 16 23.7 #of All White Players 26 - 29 Years Old 13 7.4 22.8 #of All Players 30 Years Old or Older 37 21.1 #of All Blac k Players 30 Y ears Old or Older 28 16 23.7 #of All White Players 30 Years Old or Older 9 5.1 15.8 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www.wnba.com, 2006. Table 4. Average height of WNBA players. All Players (N = 175) Black Players N = 118 White Players N = 57 Average Height Average Height Average Height 72.4 inches (over 6’0”) 72.3 inches (over 6’0”) 72.6 inches (6’1”) Source: Compiled and Computed based on Data on the WNBA Website. www. wnba.com, 2006. It is useful to note that the mean or average height of females 20 years and over in the US from 1999 to 2002 was 63.8 inches or almost 5’4” tall. When broken down according to race/cul- tural background both non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks are taller than the national average (64.2 inches each for those 20 years and over) and they are also both at 64.6 inches tall each for those 20 - 39 years (Table 5). For males 20 years and over in the US during that same period, their average height was 69.2 inches; 69.7 inches for non-Hispanic White males; and 69.5 inches for non-Hispanic Black males (Kaba, 2011a: p. 10). In addition to their average height, a total of 107 players (61.1% of all players) are 6’0” or taller. Of that total, 74 Black players (42.3% of all players, but 62.7% of all Black players) are 6’0” or taller, and 33 White players (18.9% of all players, but 57.9% of all White players) are 6’0” or taller. A total of 57 players (32.6% of all players) are 6’1’ to 6’2” tall. Of that total, 42 Black players (24% of all players, but 35.6% of all Black Table 5. Mean height (inches) for females 20 years and above, 1999-2002: United States. Females 20 Years & Over 63.8 Non-Hispanic Black Females 20 Years & Over 64.2 20 - 39 Year s 64.6 Non-Hispanic White Female s 20 Years & Over 64.2 20 - 39 Year s 64.6 Source: Ogden et al., 2004, pp. 8-15. players) are 6’1” to 6’2” tall, and 15 White players (8.6% of all players, but 26.3% of all White players) are 6’1” to 6’2” tall. A total of 68 players (38.9% of all players) are from 5’3” to 5’11” tall. A total of 50 players (28.6% of all players) are 6’3” or taller. Of that total, 32 Black players (18.3% of all players, but 27.1% of all Black players) are 6’3” or taller, and 18 White players (10.3% of all players, but 31.6% of all White players) are 6’3” or taller. A total of 30 players (17.1% of all players) are 6’4” or taller. Of that total, 17 Black players (9.7% of all players, but 14.4% of all Black players) are 6’4” or taller, and 13 White players (7.4% of all players, but 22.8% of all White players) are 6’4” or taller. A total of 16 players (9.1% of all players) are 6’5” or taller. Of that total, 6 Black players (3.4% of all pl ay ers, but 5.1% of all Black players) are 6’5” or taller, and 10 White players (5.7% of all players, but 17.5% of all White players) are 6’5” or taller. Finally, a total of 5 players (2.9% of all players) are 6’6” or taller. Of that total, 1 Black player (0.6% of all players, but 0.8% of all Black players) is 6’6” or taller, and 4 White playe rs (2. 3% of all pl ayers, but 7% of all White players) are 6’6” or taller. Four White players (2.3% of all players, 7% of all White players) are 6’7” or taller. Three White players are 6’8” or taller. There are 2 White players who are 6’8” tall, and 1 White player who is 7’2” tall (Table 6). Average Weight of All Players There might be a correlation between being taller and also weighing heavier. White players in the WNBA on average are heavier than Black players. The average weight of all WNBA players was 168.7 pounds. The average weight of White players was 169.7 pounds, and 168.1 pounds for Black players (Table 7). In the NBA, during the 2005-2006 season, the average weight of all 430 players was 223.9 pounds; 220.3 pounds for Blacks; and 233.6 pounds for Whites (Kaba, 2011a: p. 10). In the general US population, from 1999 to 2002 the mean or average weight of females 20 years and over was 162.9 pounds. For non-Hispanic White females, it was 161.7 pounds, and 182.4 pounds for non-Hispanic Black females during that same period. For those aged 20 - 39 years, it was 158.4 pounds for non-Hispanic White females, and 179.2 pounds for non-His- panic Black females (Table 8). For males 20 years and over in the US during that same period, their average weight was  A. J. KABA Table 6. Height breakdown of WNBA players. % of all % of Black % of White Item # players Players only Players only Total# of all players 6’0” and tal ler 107 61.1 Total# of all Black players 6’0” and taller 74 42.3 62.7 Total# of all White players 6’0” and taller 33 18.9 57.9 Total# of all players 6’1” to 6’ 2 ” tall 57 32.6 Total# of all Black players 6’1” to 6’2” tall 42 24 35.6 Total# of all White playe rs 6’ 1” to 6’2” ta ll 15 8.6 26.3 Total# of all players 6’3” and tall er 50 28.6 Total# of all Black players 6’3” and taller 32 18.3 27.1 Total# of all White players 6’3” and taller 18 10.3 31.6 Total# of all players 6’4” and tal ler 30 17.1 Total# of all Black players 6’4” and taller 17 9.7 14.4 Total# of all White playe rs 6’4” and taller 13 7.4 22.8 Total# of all players 6’5” and tall er 16 9. 1 Total# of all Black players 6’5” and taller 6 3.4 5.1 Total# of all White playe rs 6’ 5” and taller 10 5.7 17.5 Total# of all players 6’6” and taller 5 2.9 Total# of all Black players 6’6” and taller 1 0. 6 0. 8 Total# of all White players 6’6” and taller 4 2.3 7 Total# of all players 5’3” to 5’ 1 1” tall 68 38.9 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www.wnba.com, 2006. Table 7. Average weight of WNBA players. All Players ( N = 170) Black P l ay ers (N = 114 ) White Players (N = 56) Average Weight (pounds) Aver ag e Weight (pounds) Average Weight (pounds) 168.7 168.1 169.7 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www. wnba.com, 2006. Table 8. Mean weight (pounds) for females 20 years and above, 1999-2002: United States. Females 20 Years & O ver 162.9 Non-Hispanic Black Females 20 Years & O ver 182.4 20 - 39 Yea r s 179.2 Non-Hispanic White Female s 20 Years & O ver 161.7 20 - 39 Yea r s 158.4 Source: Ogden et al., 2004, pp. 8-15. 189.8 pounds; 193.1 pounds for non-Hispanic White males; and 189.2 pounds for non-Hispanic Black males (Kaba, 2011a: p. 11). Number of Players Institutions in Sending States Had in the WNBA: 20 06 Season A total of 33 states (with Washington DC as a state equiva- lent) in the country had colleges and universities with a com- bined total of 156 players (89.13% of all 175 players) on the rosters of WNBA teams on opening day on May 20, 2006. Of those 156 players, Blacks comprised 114 (73.1%), and Whites comprised 44 (26.9%). A total of 6 states had double figure numbers of players on opening day: Tennessee, 14 players (13 Blacks and 1 White); Texas, 11 players (10 Blacks and 1 White); Connecticut, 12 players (7 Blacks and 5 Whites); Louisiana, 12 players (all 12 are Black players); California, 11 players (9 Blacks and 2 Whites); an d Fl orida, 11 players (9 Blac ks a n d 2 Whit es). Two states had 9 players each: Georgia (7 Blacks and 2 Whites); and North Carolina (8 Blacks and 1 White). The state of Virginia had 6 players (4 Blacks and 2 Whites). Three states had 5 players each: Kansas (1 Black and 4 Whites); Indiana (2 Blacks and 3 Whites); and Pennsylvania (4 Blacks and 1 White). Four states had 4 players each: Alabama (all 4 are Black play- ers); Iowa (3 Blacks and 1 White); and Utah (1 Black and 3 Whites). Three states had 3 players each: Michigan (all 3 are White players); Missouri (all 3 are Black players); and New Jersey (all 3 are Black players). A total of 6 states had 2 players each: Massachusetts (1 Black and 1 White); Minnesota (all 2 are White players); Mis- sissippi (all 2 are Black players); Ohio (1 Black and 1 White); Oklahoma (1 Black and 1 White); Oregon (1 Black and 1 White); and South Carolina (all 2 are Black players). A total of 7 states had 1 player each: Arkansas (Black player); Colorado (White player); Nebraska (White player); Nevada (White player); Washington DC (Black player); West Virginia (White player); and Wisconsin (Black player) (Table 9). Sending Institutions (Colleges and Universities) A total of 69 colleges and universities in the United States 98 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  A. J. KABA Table 9. Number of players institutions (colleges or universities may send 1 or more players) in sending states sent : 2006 WNBA season. N = 156 State Total# of Players Sent #of Black Players #of White Players Tennessee 14 13 1 Texas 11 10 1 Connecticut 12 7 5 Louisiana 12 12 0 California 11 9 2 Florida 11 9 2 Georgia 9 7 2 North Carol ina 9 8 1 Virginia 6 4 2 Kansas 5 1 4 Indiana 5 2 3 Pennsylvania 5 4 1 Illinois 4 3 1 Alabama 4 4 0 Iowa 4 3 1 Utah 4 1 3 Michigan 3 0 3 Missouri 3 3 0 New Jersey 3 3 0 Massachusetts 2 1 1 Minnesota 2 0 2 Mississippi 2 2 0 Ohio 2 1 1 Oklahoma 2 1 1 Oregon 2 1 1 South Carolina 2 2 0 Arkansas 1 1 0 Colorado 1 0 1 Nebraska 1 0 1 Nevada 1 0 1 Washington DC 1 1 0 West Virginia 1 0 1 Wisconsin 1 1 0 Total 156 114 42 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www. wnba.com, 2006. had a total of 156 players (89.1% of all 175 players) in the WNBA on opening day, on May 20, 2006. Two Universities had double figure number of players: University of Connecticut, 12 (7 Blacks and 5 Whites), and the University of Tennessee, 11 (10 Blacks and 1 White). The University of Georgia had 8 players (6 Blacks and 2 Whites). Louisiana State University and Louisiana Tech University each had 5 players (all of them are Black). Four institutions had 4 players each: Duke University (3 Blacks and 1 White); Kansas State University (all 4 players are White); University of Florida (all 4 players are Black); and University of Southern California (all 4 players are Black). A total of 9 institutions (13% of all 69 institutions) had 3 players each: Michigan State University (all 3 players are White); Penn State University (2 Blacks and 1 White); Rutgers University (all 3 players are Black); Texas Tech (all 3 players are Black); University of Iowa (all 3 players are Black); Uni- versity of Missouri, Columbia (all 3 players are Black); Uni- versity of North Carolina (all 3 players are Black); University of Notre Dame (1 Black and 2 Whites); and the University of Virginia (all 3 players are Black). A total of 21 institutions (30.4% of all 69 institutions) had 2 players each: Auburn University (all 2 players are Black); Baylor University (all 2 players are Black); Brigham Young University (1 Black and 1 White); DePaul University (all 2 players are Black); Florida International University (1 Black and 1 White); Florida State University (1 Black and 1 White); Mississippi State University (all 2 players are Black); North Carolina State University ( all two players are Black); Old Do- minion University (1 Black and 1 White); Purdue University (1 Black and 1 White); Stanford University (all 2 players are Black); Tulane University (all 2 players are Black); University of California, Los Angeles (all 2 players are Black); University of Houston (all 2 players are Black); University of Kansas (all 2 players are Black); University of Minnesota (all 2 players are White); University of Oregon (1 Black and 1 White); Univer- sity of South Carolina, Columbia (all 2 players are Black); University of Texas, Austin (1 Black and 1 White); University of Utah (all 2 players are White); and Vanderbilt University (all 2 players are Blac k). A total of 30 institutions (43.5% of all 69 institutions) had 1 player each: Boston College (Black player); Colorado State University (White player). Florida Atlantic University (Black player); Georgetown University (Black player); Georgia Tech (Black player); Harvard University (Black player); Iowa State University (White player); Liberty University (White player); The Master’s College (White player); Ohio State University (White player); Pepperdine University (Black player); Saint Edwards University (Black player); Southeastern Oklahoma State University (Black player); Temple University (Black player); Texas Christian University (Black player); University of Alabama, Birmingham (Black player); University of Ala- bama, Tuscaloosa (Black player); University of Arkansas, Fa- yetteville (Black player); University of California, Santa Bar- bara (White player); University of Central Florida (Black player); University of Cincinnati (Black player); University of Illinois, Champaign (Black player); University of Memphis (Black player); University of Miami (Black player); University of Nebraska, Lincoln (White player); University of Nevada, Las Vegas (White player); University of Oklahoma (White player); University of Wisconsin (Black player); Western Illinois Uni- versity (White player); and West Virginia University (White player) (Table 10). Number of Players Institutions and Regions Had in the WNBA: 200 6 Season Institutions in the Southern United States sent the highest proportion of players to the WNBA. In fact, the South had the majority of players in the WNBA, compared to the other three official regions of the United States. Of 156 players for whom available data showed that they attended colleges or universities n the US, 85 (54.5%) are from institutions located in the i Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 99  A. J. KABA 100 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. Table 10. All 69 sending institutions and NCAA & NAIA conferences: 2006 WNBA season. N = 156 Players Institution Total# of Players #of Black Players #of White Players NCAA or NAIA Conference University of Connec ti cut 12 7 5 Big East Conference University of Tennessee, Knoxville 11 10 1 Southeastern Conference University of G eorgia 8 6 2 Southeastern Conference Louisiana State University 5 5 0 Southeastern Conference Louisiana T ech University 5 5 0 Western Athletic Conference Duke University 4 3 1 Atlantic Coast Conferenc e Kansas State University 4 0 4 Big 12 Conference University of Florida 4 4 0 Southeastern Conference University of Southe rn California 4 4 0 Pacific-10 Conference Michigan State University 3 0 3 Big Ten Conference Penn State University 3 2 1 Big Ten Conference Rutgers University 3 3 0 Big East C onference Texas Tec h University 3 3 0 Big 12 Conference University of Iowa 3 3 0 Big Ten Confe rence University of Mi ssouri, Columbia 3 3 0 Big 12 Conference University of North Carolina , Chapel Hill 3 3 0 Atlantic Coast Conference University of N otre Dame 3 1 2 Big East C onference University of Vir ginia 3 3 0 Atlantic C oast Conference Auburn University 2 2 0 Southeastern Confe r ence Baylor University 2 2 0 Big 12 Conference Brigham Young Univers ity 2 1 1 Mountain West Conference DePaul University 2 2 0 Big East C onference Florida International University 2 1 1 Sun Belt Con ference Florida State University 2 1 1 Atlantic Coast Conference Mississippi State University 2 2 0 Southeastern Conference North Carolina State University 2 2 0 Atlantic Coast Conference Old Dominion University 2 1 1 Colonial Athletic Association Purdue University 2 1 1 Big Ten Co nference Stanford University 2 2 0 Pacific-10 Conference Tulane University 2 2 0 Conference U SA University o f California , Los Angeles 2 2 0 Pacific-10 Conference University of Houston 2 2 0 Conference USA University of Kansas 2 2 0 Big 12 Conference University of Minnesota 2 0 2 Big Ten Conference University of Oregon 2 1 1 Pacific-10 Conference University of South Carolina, Columbia 2 2 0 Southeastern Con f erence University of Texas, Austin 2 1 1 Big 12 Conference University of Utah 2 0 2 Mountain West Conference Vanderbilt University 2 2 0 Southeastern Conference Boston College 1 0 1 Atlantic Coast Conference Colorado State University 1 0 1 Mountain West Conference Florida Atlantic University 1 1 0 Atlantic Sun Conference Georgetown University 1 1 0 Big East C onference Georgia Tech 1 1 0 Atlantic C oast Conference Harvard Univ ersity 1 1 0 Ivy League Iowa State U niversity 1 0 1 Big 12 Conference Liberty Unive r sity 1 0 1 Big South Conferenc e The Master’s College 1 0 1 Golden State Athletic Conference (NAIA) Ohio State University 1 0 1 Big Ten C onference Pepperdine University 1 1 0 West Coast Conference Saint Edwards University 1 1 0 Heartland Conference (Division II) S.E. Oklahoma State Unive rsi ty 1 1 0 Lone Star Conference (Division II) Temple University 1 1 0 Atlantic 10 Conference Texas Christia n University 1 1 0 Mountain West Conference University of Alabama, Birmingham 1 1 0 Conference USA University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa 1 1 0 Southeastern Conference University of Arkansas, Fayetteville 1 1 0 Southeastern Confere nce University of C alifornia, Santa Barbara 1 0 1 Big West Conference University of Central Florida 1 1 0 Conference USA University of Cincinna ti 1 1 0 Big East Conference University of I llinois, Champaign 1 1 0 Big Ten Con ference University of Memphis 1 1 0 Confere nce USA University of Mia mi 1 1 0 Atlantic C oast Conference University of Nebraska , Lincoln 1 0 1 Big 12 Conference University of Nevada, Las Veg as 1 0 1 Mountain West Conference University of O klahoma 1 0 1 Big 12 Conference University of Wisconsin 1 1 0 Big Ten Conference Western Illinois U niversity 1 0 1 Mid Continent Conference West Virginia University 1 0 1 Big East Conference  A. J. KABA Continued Total 156 114 42 Percentages 73.1 26.9 NAIA = National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics NCAA = National Collegiate Athletic Association Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www.wnba.com, 2006. South; 31 players (19.9%) are from the Midwest; 21 players (13.4%) are from the Northeast; and 19 players (12.2%) are from the West. Of the 114 Black players who attended institu- tions in the US, 74 (64.9%) are from the South; 15 players (13.2%) are from the Midwest; 14 players (12.3%) are from the Northeast; and 11 players (9.6%) are from the West. of the 42 White players who data showed that they attended institutions in the US, 16 (38.1%) are from the Mid west; 11 players (26.2%) are from the South; 8 play ers (19%) are from West; and 7 play- ers (16.7%) are from the Northeast. The 74 Black players who attended institutions in the South account for 47.4% of all 156 players who attended institutions in the US, and 42.3% of the total 175 players in the WNBA (Table 11). College or University Graduation Rates of WNBA Players: 200 6 Se ason WNBA players may be among the top (if not the top) of pro- fessional teams in the United States with an extremely high proportion of their players with at least a bachelor’s degree. These degrees are earned from many of the most highly ranked academic institutions in the country (such as Harvard Univer- sity, Duke University, Stanford University, etcetera). To pre- sent a better perspective on the academic progress of WNBA players, this author compiled the names of the 69 colleges or universities that had players in the WNBA and counted how many of them are also listed in the 2006 US News & World Report college rankings for the United States. The US News & World Report college academic rankings are divided into three sections: 1) National Universities, which ranks the top 120 institutions (both Tier 1 and Tier 2 combined) according to academic strength. This particular ranking had 124 institutions because some institutions are tied for certain positions. For example, Princeton University and Harvard University are tied for the top spot; 2) Tier 3 institutions, which are a group of 64 colleges and universities listed alphabetically; and 3) Tier 4 institutions, which are a group of 60 institutions listed alpha- betically. The total number of all institutions in the three groups is 248. Of the 69 colleges and universities that had players in the WNBA as of May 20, 2006, six (8.7%) were not listed on any of the three rankings by US News & World Report. A total of 64 institutions (25.8% of all 248 institutions) with players in the WNBA were listed on one of the three ranking lists. For the Top 120 academic institutions, a total of 46 institutions (37.1%) with players in the WNBA were ranked; A total of 23 institu- tions (18.5% of all top 124 institutions listed) were ranked in the top 60; a total of 8 institutions (6.4% of all top 124 institu- tions listed) were ranked in the top 25; and 3 institutions (Har- vard University, Duke University and Stanford University) (2.4% of all top 124 institutions listed) were ranked in the top 5 (Table 12). A total of 12 institutions (18.7% of all 64 institutions ranked in Tier 3) with players in the WNBA were among the 64 insti- tutions grouped in Tier 3. Finally, for the 60 institutions ranked in Tier 4, there were 6 institutions (10% of all 60 institutions in Tier 4) among those 60 Tier 4 institutions in the US News & World Report 2006 college rankings (Table 12). Let us now examine the graduation rates of WNBA player. For the 2006 WNBA roster, college or university attendance data were provided for 156 (89.1%) of the 175 total players. College or university attendance data were not provided for 19 players. Out of the 156 players who attended colleges and uni- versities in the US, data show that 155 (99.4%) graduated or have at least a bachelor’s degree. The 155 players with degrees comprised 88.6% of all 175 players in the WNBA. A total of 113 Black players (72.9% of all players with de- grees) had bachelor’s degrees. A total of 42 White players (27.1% of all players with degrees) had a bachelor’s degree. No college or university degree attainment data were available for one Black player who attended a univer sity in the United States. Of the 114 Black players who attended institutions in the US, 113 (99.1%) graduated or have bachelor’s degrees. of the 42 White players who attended institutions in the US, 42 (100%) graduate d or have bachelor’s degrees. The 113 Black players for whom data show that they have degrees, comprised 95.8% of all 118 Black players, and 64.6% of all players. The 42 White players for whom data show that they have degrees, comprised 73.7% of all 57 White players, and 24% of all players (Table 13). Number of WNBA Players Sent By NCAA and NAIA Conferences Of the 32 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I conferences 18 (56%) had at least 1 player in the 2006 WNBA season. There is 1 player in the league from the Table 11. Institutions and regions send ing players to th e WNBA: 2006 season. N = 175 Region Total# Insts. Sent % Total# of Black Players Sent% of BlacksTotal# of White Players Sent% of Whites Northeast 21 13.4 14 12.3 7 16.7 South 85 54.5 74 64.9 11 26.2 Midwest 31 19.9 15 13.2 16 38.1 West 19 12.2 11 9.6 8 19 Total 156 100 114 100 42 100 Source: Compiled and computed based on dat a on the WNBA website. ww .wnba.com, 2006. Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 101  A. J. KABA Table 12. Total# of players of each sending Inst itution to the WNBA, 2006 US News & World Report academic ranking, 2006. N = 156 Players Institution Total# of Players Rank# of Top 120 InstitutionsTier 3 Institutions Tier 4 Institutions University of C onnecticut 12 68 University of Tennessee, Knoxville 11 85 University of Georgia 8 58 Louisiana State University 5 Tier 3 Louisiana Tech University 5 Tier 3 Duke Univers ity 4 5 Kansas State University 4 Tier 3 University of Florida 4 50 University of Southe rn California 4 30 Michigan State University 3 74 Penn State University 3 48 Rutgers University, New Brunswick 3 60 Texas Tech University 3 Ti er 3 University of Iowa 3 60 University of Mi ssouri, Columbia 3 85 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill 3 27 University of N otre Dame 3 18 University of Virginia 3 23 Auburn Uni v ersity 2 85 Baylor Uni versity 2 78 Brigham Young Univers ity 2 71 DePaul University 2 Tier 3 Florida International Univer sity 2 Tier 4 Florida State University 2 109 Mississippi State University 2 Tier 3 North Carolina State University 2 78 Old Dominion University 2 Tier 4 Purdue University 2 60 Stanford University 2 5 Tulane University 2 43 University o f California, Los Angeles 2 25 University of H ouston 2 Tier 4 University of Kansas 2 97 University of Mi nnesota 2 74 University of O regon 2 115 University of South Carolina, Columbia 2 109 University o f Texas, Austin 2 52 University of U tah 2 120 Vanderbilt University 2 18 Boston College 1 40 Colorado State University 1 120 Florida Atlant i c University 1 Tier 4 Georgetown University 1 23 Georgia Institute of Technology 1 37 Harvard Univ ersity 1 1 Iowa State University 1 85 Liberty University 1 NA The Master’s College 1 NA Ohio State University, Columbus 1 60 Pepperdine University 1 55 Saint Edwards University 1 NA S.E. Oklahoma S t ate University 1 NA Temple University 1 Tier 3 Texas Christian University 1 97 University of Alabama, Birmingham 1 Tier 3 University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa 1 104 University of Ar k ansas, Fayetteville 1 Tier 3 University o f California, Santa Barbara 1 45 University o f Central F lo r ida 1 Tier 3 University of Cincinnati 1 Tier 3 University of Illinois, Champaign 1 42 University o f Memphis 1 Tier 4 University of Mia mi 1 55 University of Nebraska, Lincoln 1 97 University of Nevada, Las Vegas 1 Tier 4 University of Oklahoma 1 109 University o f W i s consin 1 34 Western Illinois University 1 na West Virginia U niversity 1 Tier 3 102 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  A. J. KABA Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 103 Continued Total 156 NAIA = National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics NCAA = National Collegiate Athletic Association NA = Not Available Source: “America’s Best Colleges”, US News & W orld Report College Rankings. http://www.usnews.com/usn ews/edu/college/rankings/ . Retrieved on May 20, 2006. Table 13. College or university att en da nc e and graduation rates of WN BA players: 2006 season. N = 175 Item # % of Total (N) As % of Those Enrolled #of Blacks % #of Whites % Total# of all players e nrolled in College/University in US 15689.1 Total# of all players who graduated from College/University 15588.6 99.4 113 72.9 42 27.1 Total# of players with out College Attendance Data A vailable 19 4 21.1 15 78.9 #of black players who attended but no year of g raduation d ata Shown 1 #of white players who attended but no year of g raduation d ata Shown 0 % of black players who gradua ted within 118 black total (9 5.8%) % of white players who graduated within 57 white total (73.7 % ) % of black players who gra duated within 114 blacks who attended (99.1%) % of white playe r s who graduated within 42 whites who attende d (100%) Source: Compiled and computed based on dat a on the WNBA website. ww .wnba.com, 2006. National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA). There are 2 Division II conferences with 2 players combined in the league. A total of 6 NCAA Division I conferences had double figure numbers of players in the WNBA: Southeastern Confer- ence, 38 players (24.4% of all 156 players who attended institu- tions in the US); Big East Conference, 23 players (14.7%); Big 12 Conference, 19 players (12.2%); Atlantic Coast Conference, 17 players (10.9%); Big Ten Conference, 16 players (10.3%); Pacific-10 Conference, 10 players (6.4%); Conference USA, 7 players (4.5%); Mountain West Conference, 7 players (4.5%); Western Athletic Conference, 5 players (3.2%); Colonial Ath- letic Association, 2 players (1.3%); Sun Belt Conference, 2 players (1.3%); Atlantic 10 Conference, 1 player (0.6%); Atlan- tic Sun Conference, 1 player (0.6%); Big South Conference, 1 player (0.6%); Big West Conference, 1 player (0.6%); Ivy Group, 1 player (0.6%); Mid Continent Conference, 1 player (0.6%); West Coast Conference, 1 player (0.6%) (Table 14). The Golden State Athletic Conference of the National Colle- giate Athletic Association (NAIA) had 1 player (0.6%). Two Division II Conferences had 2 players: Heartland Conference, 1 player (0.6%), and the Lone State Conference, 1 player (0.6%) (Table 14). Number and Names of Institutions in States with Players in the WN B A : 2 006 Season The 33 states (including Washington DC as a state equiva- lent) that had players in the WNBA on opening day on May 20, 2006, had 69 colleges and universities with each having at least 1 player in the league. According to Table 15, three states (9.1% of all 33 states) have 6 different institutions with players in the WNBA: California, Florida and Texas. A total of 6 states (18.2% of all 33 states) have 3 different institutions each with players in the WNBA: Alabama, Illinois, Louisiana, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia. A total of 9 states (27.3% of all 33 states) have 2 different institutions each with players in the WNBA: Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Massachusetts, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Utah. Finally, a total of 15 states (45.4% of all 33 sending states) had 1 institution each with players in the WNBA: Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, Nevada, Oregon, South Carolina, Washington DC, West Virginia, and Wisconsin (Table 15). International Players in the WNBA: 200 6 Se ason The 2006 WNBA season had a substantial proportion of players from many countries across the world, including Aus- tralia, Belarus, Canada, Democratic Republic of Congo, the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Ivory Coast, France, Latvia, Mali, Poland, Portugal, Russia, and Yugoslavia. For example, research by this author identified a total of 29 international players on rosters as of May 20, 2006 opening day of regular season games. These 29 players include both those who at- tended college in the US and those who came directly from abroad. The 29 international players comprised 16.6% of the total 175 players in the league. Among the 29 international players, White players accounted for 20 (69%) and Black play- ers account for 9 (31%). The 20 White players comprised 35.1% of the total 57 White players. The 9 Black players com- prised 7.6% of the total 118 Black players. Also, the average age of all 29 international players is 26.3 years, and their average weight is 171.1 pounds. Their average height is 73.7 inches (almost 6’2”). The average age of the 20 White players is 26.7 years, and their average weight is 173.5 pounds. The average height of the 20 White international play- ers is 73.9 inches (almost 6’2”). For the 9 Black international players, their average age is 25.7 years, and their average weight is 166.2 pounds. Their average height is 73.3 inches (just over 6’1”) (Compiled and computed based on 2006 data on the wnba.com). In addition, a total of 19 international players arrived in the WNBA directly from overseas or abroad. of that total, 15 (78.9%) are White and 4 (21.1%) are Black. These 19 players  A. J. KABA Table 14. Number of WNBA players sent by NCAA & NAIA conferences. N = 156 Name of Conference Number of Players Se nt% American East Conference 0 0 Atlantic 10 Conferenc e 1 0.6 Atlantic C oast Confe rence 17 10.9 Atlantic Sun Conference 1 0.6 Big 12 Confe rence 19 12.2 Big East C on ference 23 14.7 Big Sky Conference 0 0 Big South Conference 1 0.6 Big Ten Conference 16 10.3 Big West Conference 1 0.6 Colonial Athle tic Association 2 1.3 Conference USA 7 4.5 Division I Indepe nd e nts 0 0 Horizon League 0 0 Ivy Group 1 0.6 Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference 0 0 Mid Continent Confere nce 1 0.6 Mid-American Conference 0 0 Mid-Eastern At hletic Conference 0 0 Missouri Valley Conference 0 0 Mountain West Conference 7 4.5 Northeast Conference 0 0 Ohio Valley Conference 0 0 Pacific-10 Conference 10 6.4 Patriot League 0 0 Southeastern Confere nce 38 24.4 Southern C onference 0 0 Southland Conference 0 0 Southwestern Athletic Conference 0 0 Sun Belt Conference 2 1.3 West Coast Conference 1 0.6 Western Athletic Conference 5 3.2 Heartland Conference (Division II, St. Edwards University) 1 0.6 Lone Star Conference (Division II SE Oklahoma State University) 1 0.6 Golden State Athletic Conference (NAIA), The Master’s College 1 0.6 Total 156 99.7 NAIA = National Association of I ntercollegiate Athletics NCAA = National Collegiate Athletic Association Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www.wnba.com, 2006. comprised 10.9% of all 175 WNBA players (Table 16). For comparative purposes, during the 2005-2006 NBA sea- son, almost 1 out of every 5 of the 430 players (19%) was from overseas. of the 82 international players, 56 were non-Black, 26 were Black (Kaba, 2011a: p. 4). International players were from 38 nations and territories, with 54 of them from 15 European countries, 11 from Latin American nations, 8 from Caribbean nations, 7 from sub-Saharan African nations, 3 from the Middle East, 2 from Canada, 2 from the Asian nation of Georgia, 1 each from Australia, China, South Korea and New Zealand (Kaba, 2011b). Discussion A contributing factor to the large number of Black WNBA players is that they comprise a substantial proportion of female college basketball players in the US, where the WNBA drafts the majority of its play ers. For exa mple, according to a January 2005 NCAA report, in 2003- 2004, there were an estima ted 3947 (27% of all female basketball play ers) non-Hispanic Black female bas- ketball players and 9373 (64.2% of all female basketball players) non-Hispanic White female basketball players in Divisions I, II & III combined. These figures did not include non-resident alien female basketball players, who comprised 364 during that same period (“1999-2000—2 003 -2004 NCAA”, January 2005: pp. 5-9, 66). It is in Division I Women’s college basketball (where the majority of WNBA players are either drafted or come from), however, that has a higher proportion of Black female players. For example, in 2003-2004, there were 1987 (41.6% of all Divi- sion I female basketball players) non-Hispanic Black female Division I basketball players, and there were 2235 (46.8% of all Division I femal e basketball players) non- Hispanic White female basketball players (“1999-2000—2003-2004 NCAA”, January 2005: p. 8, 67). The reason why the proportion of Black female players is relatively high is that in October 2004, for example, there were 9,808,000 females enrolled in US colleges and universities, with non-Hispanic Black females compri sing 1,525,000 (15.5%), and White females in general accounted for 7,438,000 (75.8%) (“School Enrollment”, 2005). To look at this differently, for example, as of March 2002, of the 282 million people in the US, males comprised 137.9 million (48.9%), and females comprised 144.2 million (51%). Non-Hispanic Black females comprised 19.3 million (13.4% of the total female population) and non-Hispanic White females comprised 99.4 million (68.9% of the total female population) (“The Black Population in the United States”, 2003). The data in this study also show that WNBA players, in- cluding Black players are highly educated, with at least a bach- elor’s degree. Among professional sports in 2006 in the United States, it appears as if WNBA players may have the highest proportion with at least a bachelor’s degree, from America’s colleges and universities, including from Harvard University. This is a trend also observed in society in general, with females now earning more bachelor’s degrees than their male counter- parts, despite experiencing exclusion from most colleges and universities in US history. Black females, who have experi- enced the most severe exclusion, have been the most impressive as the data above show and as new educational attainment data (from Bachelor’s degree to professional and doctorate degrees) of the US show. By 2009, within the general US population Black females are behind only Asian males and Asian females most of whom are foreign born) in the proportion within their ( 104 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  A. J. KABA Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 105 Table 15. Number & names of institut ions in states with players in the WNBA: 2006 season. N = 69 State Total # of Institutions Names of Institut ions Tennessee 3 University of Tennessee, Universi t y of Memp h is, & Vanderbilt University Texas 6 University of Texas, Austin, Texas Christia n, University of Houston, St. Edwards Unive rsity, Texas Tech University & Baylor University Connecticut 1 University of Connecticut Louisiana 3 Louisiana State University, Louisiana Tech Uni, & Tulane University California 6 UCLA, USC, Pepperdine University, Stanford University, University of California, Santa Barbara, & The Master’s College Florida 6 Florida International, University of Florida, Florida Atla n ti c Universi ty, Florida Sta te University, Un i versity of Miami, & Universi ty of Centr al Florida Georgia 2 University of Georgia & Georgia Ins t itute of T echnology North Carolina 3 Duke University, N.C. State Un iversity, & Unive rsity of North Carolina Virginia 3 Liberty University, Old Dominion University, & University of Virginia Kansas 2 Kansas State Uni & University of Kansas Indiana 2 University of Notre Dame & Purdue University Pennsylvania 2 Penn State University & Temple Unive r s it y Illinois 3 DePaul Uni, University of Illinois, Champaign, & Western Illinois University Alabama 3 Auburn University, University of Alabama, Birmingham, & University of Ala bama, Tuscaloosa Iowa 2 Iowa State University & University of Iowa Utah 2 Brigham Young University & University of Utah Michigan 1 Michigan State University Missouri 1 University of Missouri New Jersey 1 Rutgers University, State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick Massachuset ts 2 Boston College & Harvard University Minnesota 1 University of Minnesota Mississippi 1 Mississippi State University Ohio 2 Ohio State U ni v ersity & Unive rsi t y of Cincinnati Oklahoma 2 Southeastern Oklahoma State University & University of Oklahoma Oregon 1 University of Oregon South Carolina 1 University of South Carolina, Columbia Arkansas 1 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Colorado 1 Colorado State University Nebraska 1 University of Nebraska Nevada 1 Universit y of Nevada, Las Veg as Washington DC 1 Georgetown University West Virginia 1 University of West V irginia Wisconsin 1 University of Wisconsin Total 69 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www.wnba.com, 2006. group or category enrolled in college. The dedication to educa- tional attainment of Black American females is so strong that they would go deep into debt to attain their college education (Fiegener, 2009; Hoffer et al., 2003; Kaba, 2005, 2011c). For example, due to Black females, among those in the United States who earned doctorates in 2008, Blacks had the highest level of debt: $38,586; $29,698 for American Indians; $27,553 for Hispanics; $25,761 for multiracial individuals; $21,299 for Whites; and $13,216 for Asians (Fiegener, 2009: p. 53). In addition to their love for the game of basketball, Black females in particular and females in general use the game to win scholarships to earn their bachelor’s or master’s degrees, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars or more. Videon (2002) points out that: “…participation in athletics is associated with an array of positive educational outcomes. Students who participate in sports have better attendance records, lower rates  A. J. KABA Table 16. Players coming directly from overseas to the WNBA. Total# Directly from Overseas Total# from Overseas Black Players % Total# from Overseas White Players % 19 4 21.1 15 78.9 Source: Compiled and computed based on data on the WNBA website. www. wnba.com, 2006. of discipline referrals, and higher academic self-esteem and are more likely to be in a college preparatory curriculum, earn higher grades, and aspire to, enroll in, and graduate from col- lege” (p. 415). According to Lapchick (2011), during the 2011 NCAA Men’s and Women’s tournaments: “95 percent (60) of the women’s teams compared to 63 percent (42) of the men’s teams graduated at least 60 percent of their players” (p. 1; also see Gaston-Gayles, 2004: p. 75). Hamilton (2003) writes of a talented African American University of Tennessee women’s basketball player named Kara Lawson, who despite being one of the top college basketball players in the country, managed to graduate “…as a finance major with 3.75 GPA” (p. 22). According to Kaba’s (2011a) study of the 2005-2006 NBA season, data were only provided for the academic institutions (high schools, colleges and universities) in the US that the players attended, but not whether they graduated. There were 35 players who entered the league directly from US high schools during that season (also see Kaba, 2011b). Finally, it is important to briefly discuss why society would allow WNBA players to be paid a salary of $50,000 by 2006 while their brothers or male counterparts are paid an average of almost $4 million during the 2005-2006 season. This is the case even with advertisement or endorsement opportunities. Fans appear to be willing to pay the males substantially more than their female counterparts. As a result, a substantial number of WNBA players have to go overseas to play professionally once the WNBA season ends because they are paid better in those nations than in the United States (James, 2002; McCabe, 2011; Spencer & McClung, 2001; Staffo, 1998ab; Ruihley et al., 2010; Wearden & Creedon, 2002). Staffo (1998a) notes that an esti- mated 500 women from the United States we re playing overseas (p. 190). Staffo (1998a) also adds that: “Professional leagues outside the United States existed in Spain, Italy, Germany, Scandinavia and Japan. A few US stars, such as Teresa Ed- wards and Katrina McClain, made an estimated $200,000 for a six-month season” (p. 190). Even though some WNBA players earn significantly more than the average and that some also get endorsements, those figures are not as high as the males. Issacson (2006) points out that: “The highest-paid WNBA players earn about $90,000, and with endorsement deals, stars can push that to as much as $200,000. Overseas salaries for the best players approach $500,000” (p. 1). Staffo (1998a) also notes that “…superstars like Lisa Leslie, Rebecca Lobo and Sheryl Swoopes are said to be making up to $250,000 when promotional fees are added in...” (p. 193). According to Spencer and McClung (2001), former WNBA star Cynthia Cooper signed endorsement con- tracts with both General Motors and Nike for an estimated $500,000 annually (p. 334). Ruihley et al. (2010) note that NBA player LeBron James, who entered the league directly from high school, signed a multi-year contract with Nike for $90 million; that in 2009, golf player Tiger Woods’ endorse- ment income was $110 million; and that in 1997 former NBA player Michael Jordan earned $40 in endorsements (pp. 133-135). Fans tend to show more support for male sports through their rate or level of attendance and also through ticket price. Ac- cording to McCabe (2011), “A critical outcome of understand- ing the nature of spectators’ involvement with competitive sports is its relevance in predicting consumption attitudes and purchasing behavior” (pp. 107-108). Smith and Roy (2011) claim that: “Ticket sales represent the most important source of local revenues for most sport teams. Revenue from ticket sales makes up at least 50% of all local revenues for the four major professional sports leagues in the United States (NFL, MLB, NBA, and NHL)” (p. 93). According to Staffo (1998a): “During the first [WNBA] season average attendance was 9669 per game, with the single largest crowd being 18,937 when Hous- ton played at Charlotte August 16, 1997… The first champi- onship game was played August 30 at The Summit, with the Houston Comets defeating the New York Liberty. Attendance was 16,285” (p. 192). Cotes and Humphreys (2007) point out that the average attendance to NBA games from 1991 to 2001 was 16,671 (p. 167). Jacobsen (2010) reports that in the WNBA: “[Ticket prices for] Most franchises start around $10 and go as high as $200 or more. Single-game tickets to the defending champ Phoenix Mercury begin at $10 and go as high as $195.25. The New York Liberty charges anywhere from $10 to $260, the latter for courtside seats” (p. B1). It is noted that the average NBA ticket price in 2010 was $48.08; $99.25 for the Los Angeles Lakers; and $88.66 for the New York Knicks (“NBA Sees Ticket Prices Slump,” 2010: p. C2). Staffo (1998b) claims that during the 1996-1997 NBA season, the price of front row seat at a New York Knicks home game at the Madison Square Garden was $1000 (p. 15). Voisin (2011) points out that the NBA’s annual revenue is $4 billion. How can one explain this human behavior of gender bias in sports? According to James (2002): “It has been proposed that women’s sports have a different appeal than men’s sports” (p. 141). Wearden and Creedon (2002) claim that: “Feminist scholars point to the huge disparity in endorsement revenue between male and female athletes as evidence of a male hierar- chy in sport… The gender hierarchy argument holds that fe- male athletes are both “other than” and “less than” their male counterparts” (p. 189). In addition, females involved in team sports may experience more discrimination in earnings than those in individual sports. For example, according to Wearden and Creedon (2002): “… researchers have found a sex-appropriate ranking scheme in sport that suggests individual sports (that is tennis, figure skat- ing, golf and gymnastics) are more appropriate for women than team sports” (p. 189). Staffo (1998a) attempts to present this philosophical explanation of gender bias in sports: “Finally one big difference between the development of men’s sports and women’s sports in the US is that women’s sports have always been based in the philosophy and are an outgrowth of the women’s physical education program and therefore have gen- erally maintained a purer attitude in the pursuit of sports for sports sake. This philosophy has generally kept women’s sports free from the corruption that has frequently marred men’s sports” (p. 195). 106 Copyright © 2012 SciRes.  A. J. KABA Conclusion This study has attempted to present an in-depth examination of the players in the 2006 United States Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA) season. The data show that Black players or players of African descent comprised the ma- jority of the league as of the first day of the 2006 season. Al- most all of the players who attended colleges and universities in the United States graduated. These athletes also attended many of the most selective institutions in the United States, including Harvard University. Colleges and universities from the South- ern United Stat es sent the majority of all players to the WNBA in 2006. International players comprised a significant propor- tion of players in the WNBA in 2006. WNBA players, like professional women athletes in other sports do not get a fair compensation for their talents due to gender bias within the society. However, the data in this study also indicate that these women are set to take-up various leadership positions after their athletic careers not only in the United States, but the world as well. They have the first class academic education and disci- pline from sports that they will take with them in their future leadership roles. Finally, these players also have become repre- sentatives or ambassadors of the colleges and universities and states where they were educated. REFERENCES Abney, R. (1999). African American women in sport. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 70, 35-38. America’s Best Colleges (2006). US News & World Report. URL (last checked 20 May 2006). http://www.usnews.com/usnews/edu/college/rankings Baker, C. A. (2008). Why she plays: The world of women’s basketball. Winnipeg: Bison Books. US Census Bureau (2003). The black population in the United States: March 2002. Washington DC: Gover nment Printing Office. Cahppell, R. H., & Karageorghis, C. I. (2001). Race, ethnicity, and gender in British basketball. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 10, 29-46. Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. R. (2007). Ticket prices, concessions and attendance at professional sporting events. International Journal of Sports Finance, 2, 161-17 0. Gaston-Gayles, J. L. (2004). Examining academic and athletic moti- vation among student athletes at a Division I University. Journal of College Student Devel opment, 45, 75-83. doi:10.1353/csd.2004.0005 Gomez, M. A., Lorenzo, A., Ortega, E., Sampaio, J., & Ibanez, S. J. (2009). Game related statistics discriminating between starters and nonstarters players in Women’s National Basketball Association League (WNBA). Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 8, 278-283. Grundy, P., & Shackelford, S. (2007). Shattering the glass: The re- markable history of women’s basketball. Chapel Hill, NC: The Uni- versity of North Car oli n a Press. Fiegener, M. K. (2009). Doctorate recipients from US universities: Summary Report 2007-2008. Directorate for social, beh avior al, a nd eco- nomic sciences, National Science Foundation. Table 24, 53. Arling- ton: Divisi on of Sci ence Resour ces Stat istics. Hoffer, T. B., Sederstrom, S., Selfa, L., Welch, V., Hess, M., Brown, S., Reyes, S., Webber, K., & Guzman-Barron, I. (2003). Doctorate re- cipients from United States universities: Summary Report 2002 (pp. 113-115). Chicago: National Opinion Research Center. Hamilton, K. (2003). Courting success; University of Tennessee fi- nance major balances hoops excellence with academic achievement. Black Issues in Higher Education, 20, 22-23. Isaacson, M. (2006). Promotions in motion: WNBA athletes do more than play: They also sell the league. Knight Ridder Tribune Business News, 1. Jacobsen, L. (2010). Shock is pleased by ticket sales for opener. Tulsa World, B1. James, J. D. (2002). Women’s and men’s basketball: A comparison of sport consumption motivations. Women in Sport & Physical Activity Journal, 11, 141-170. Kaba, A. J. (2011a). African Americans in the National Basketball Association (NBA), 2005-2006: Demography and earnings. Interna- tional Journal of Social and Management Sciences, 4, 1-25. Kaba, A. J. (2011b). Characteristics of players in the 2005-2006 US National Basketball Association (NBA). URL (last checked 14 Oc- tober 2011). http://www.hollerafrica.com/index.php Kaba, A. J. (2011c). Black American females as geniuses. Journal of African American Studies, 15, 120-124. doi:10.1007/s12111-010-9134-1 Kaba, A. J. (2006a). The blood and family relations between Africans and Europeans in the United States. African Renaissance, 3, 105- 114. Kaba, A. J. (2006b). Race, geography and territorial inheritance: People of Black African, European and Chinese Descent. URL (last checked 14 October 2011). http://www.hollerafrica.com/ Kaba, A. J. (2005). Progress of African Americans in higher education attainment: The widening gender gap and its current and future implications. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13, 1-34. Kochman, L., & Goodwin, R. (2003). Market efficiency and the women’s NBA. American Business Re vi ew, 21 , 141-143. Lapchick, R. (2011). Keeping score when it counts: Academic pro- gress/graduation success rate study of NCAA Division I Women’s and Men’s Basketball Tournament Teams. URL (last checked 20 October 2011) http://tidesport.org/Grad%20Rates/2011_Womens_Bball_Study_FIN AL.pdf Lapchick, R., & Kushner, D. (2006) . The 2005 racial and gender report card: Women’s National Basketball Association. Orlando: University of Central Florida. McCabe, C. (2011). Spectators’ relationship women’s professional basketball: Is it more than sex? North American Journal of Ps y ch ol o gy , 13, 107-122. McDonald, M. (2000). The marketing of the Women’s National Bas- ketball Association and the making of Post-Feminism. International Re- view for the Sociology of Sports, 35, 35- 47. doi:10.1177/101269000035001003 NBA Sees Ticket Prices Slump (2010). The Times—Transcript. Monc- ton, C2. Ogden, C. L., Fryar, C. D., Carroll, M. D., & Flegal, K. M. (2004). Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960-2002. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 347. Hyattsville, MA: National Center for Health Statistics. Picker, D. (2006). East all-stars break through on night for young and old. New York Times, D.6. US Census Bureau (2005). School enrollment—Social and economic characteristics of students: October 2004. Washington DC: Gov- ernment Printing office. Smith, J. G., & Roy, D. P. (2011). A framework for developing cus- tomer orientation in ticket sales organizations. Sports Marketing Quarterly, 20, 93-102. Spencer, N. E., & McClung, L. R. (2001). Women and sport in the 1990s: Reflections on embracing stars, ignoring players. Journal of Sport Management, 15, 318-349. Ruihley, B., Runyan, R. C., & Lear, K. E. (2010). The use of sport celebrities in advertising: Replication and extension. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 19, 132-142. Staffo, D. (1998a). The history of women’s professional basketball in the United States with an emphasis on the Old WBL and the New Copyright © 2012 SciRes. 107  A. J. KABA 108 Copyright © 2012 SciRes. ABL and WNBA. Physical Educator, 55, 187-198. Staffo, D. F. (1998b). The development of professional basketball in the United States, with an emphasis on the history of the NBA to its 50th anniversary season in 1996-199 7. Physical Educator, 55, 9-18. Videon, T. M. (2002). Who plays and who benefits: Gender, interscholastic athletics, and academic outcomes. Sociological Perspectives, 45, 415- 444. doi:10.1525/sop.2002.45.4.415 Voisin, A. (2011). NBA must fix its broken business model. The Sac- ramento Bee. URL (last checked 8 October 2011). http://m.standard.net/topics/sports/2011/07/01/voisin-nba-must-fix-br oken-business-model Wearden, S., & Creedon, P. J. (2002). “We Got Next”: Images of women in television commercials during the inaugural WNBA Sea- son. Culture, Sport, Society, 5, 189-210. doi:10.1080/713999865 Yafie, R. C. (1997). The WNBA’s full court press. The Journal of Business Strategy, 18, 32- 33. 1999-00—2003-04 NCAA Student-Athlete Ethnicity Report (2005). Published by the National Collegiate Athletic Association. P.O. Box 6222. 317/917-622 2 . www.ncaa.org.

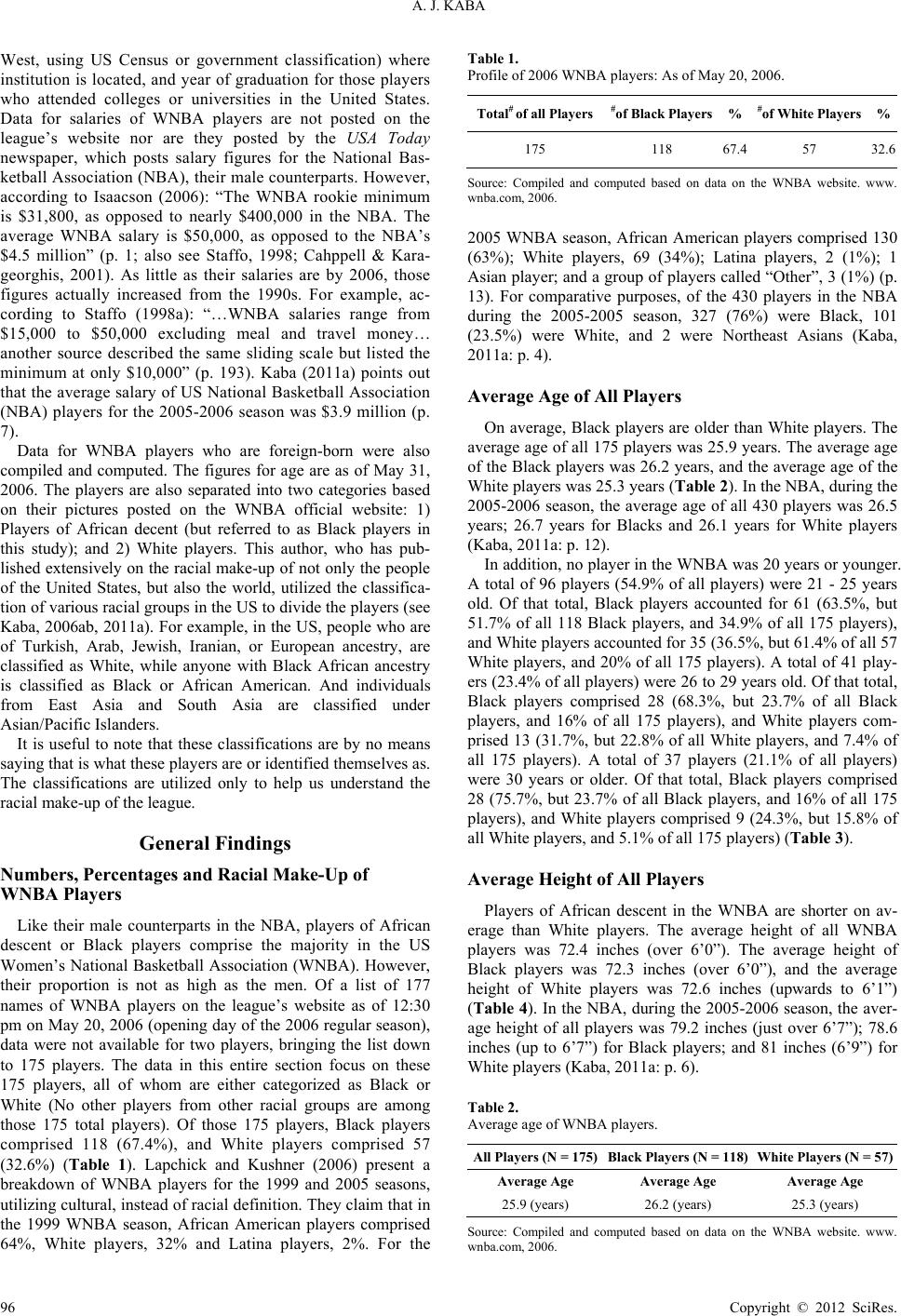

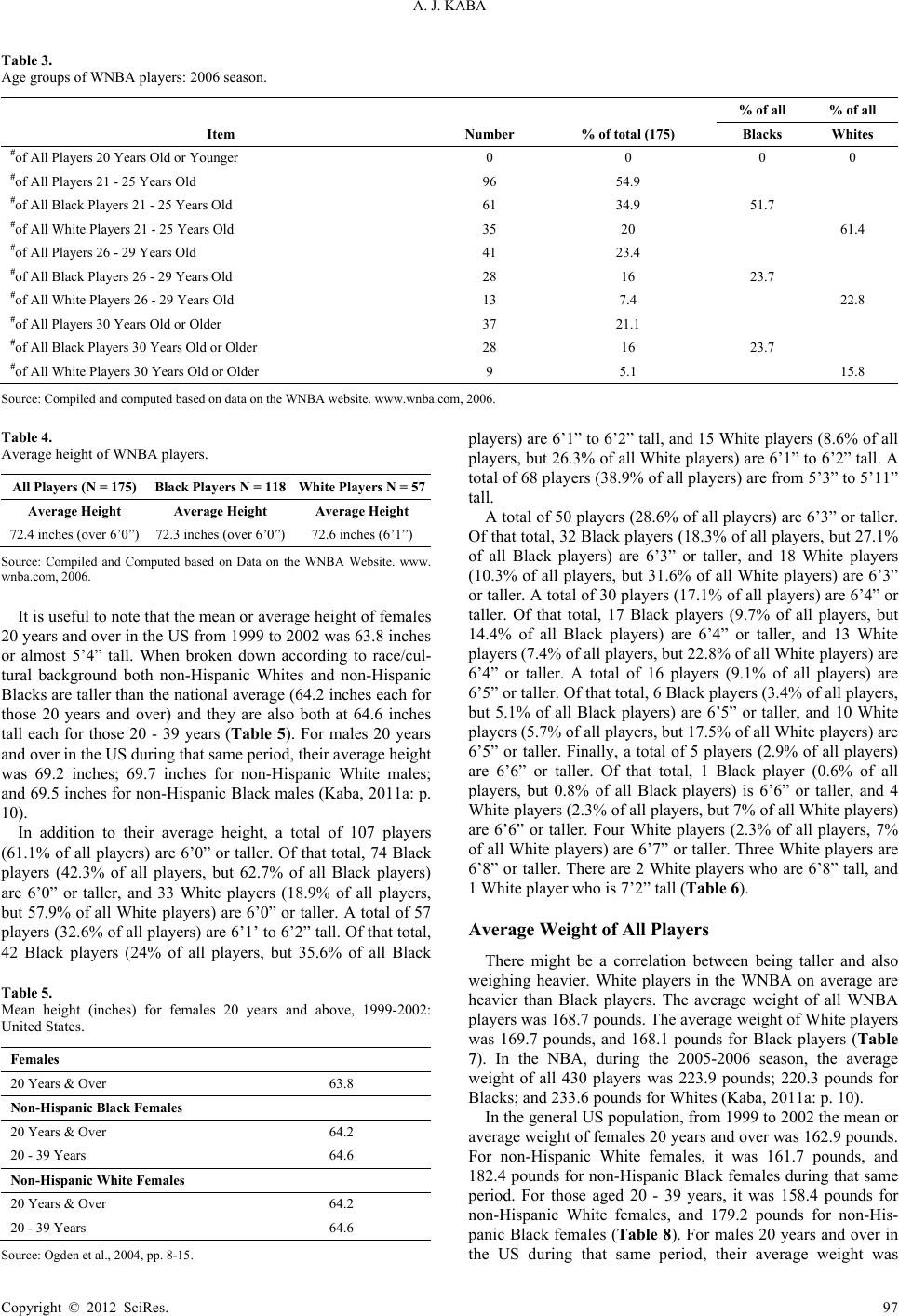

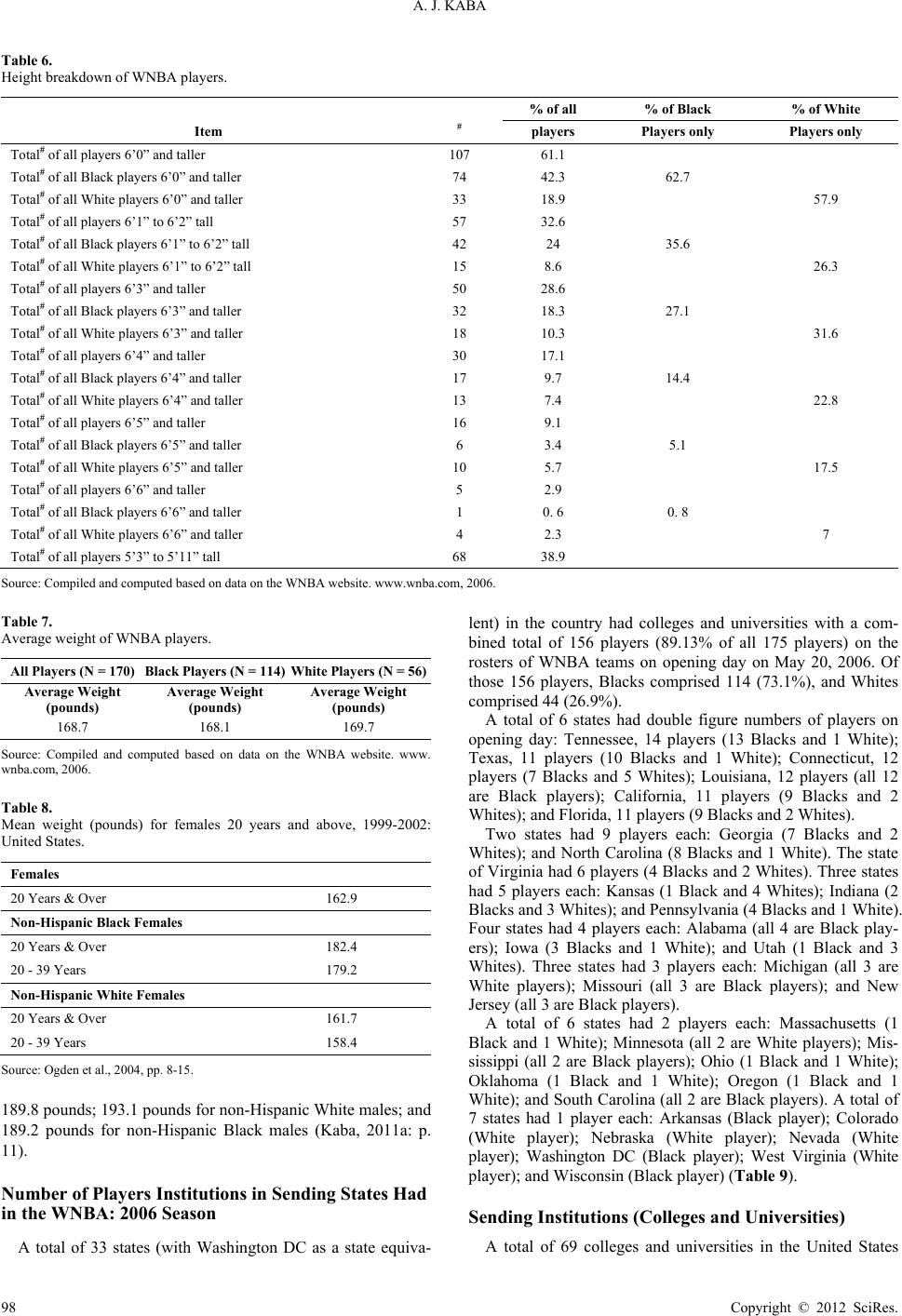

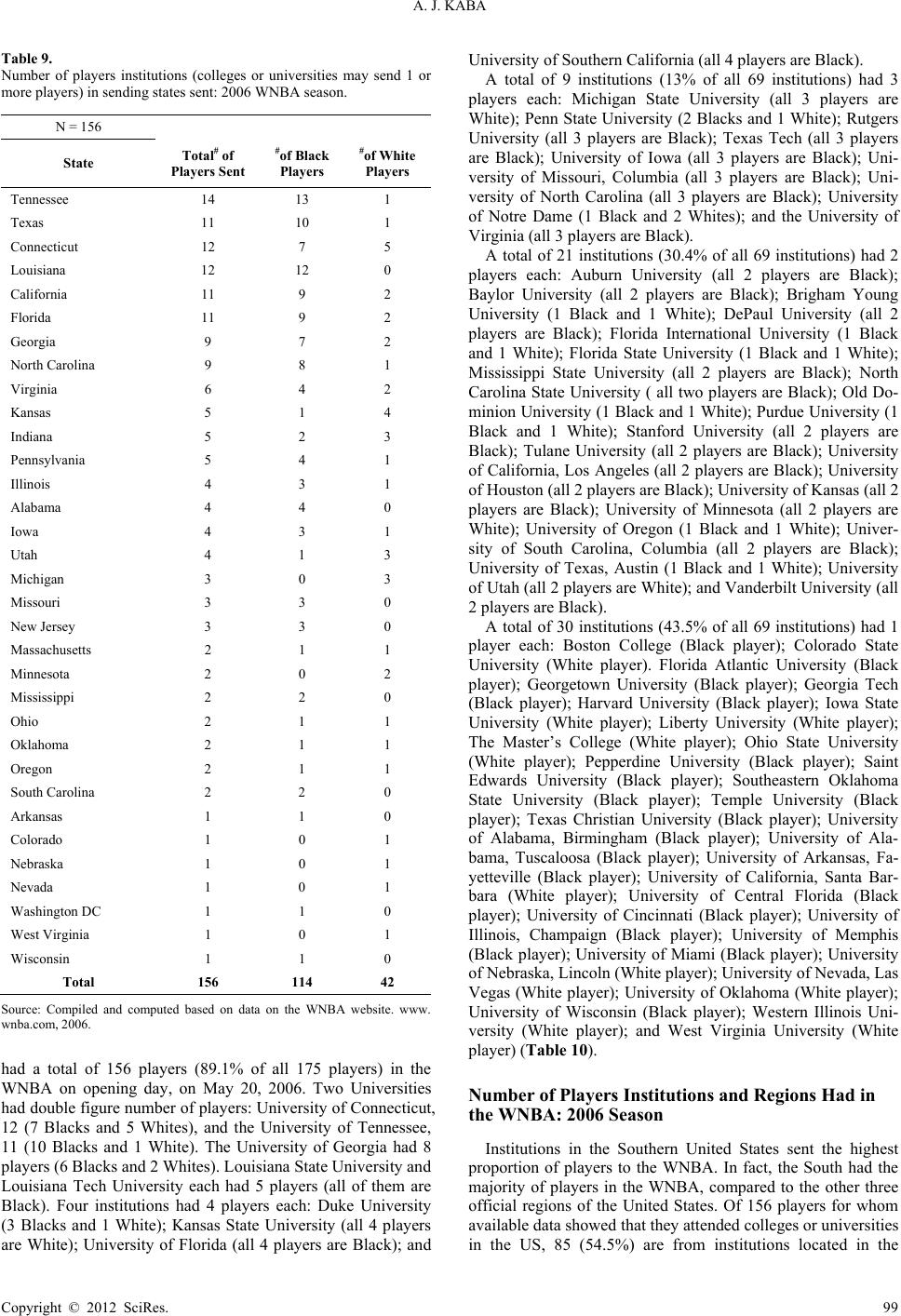

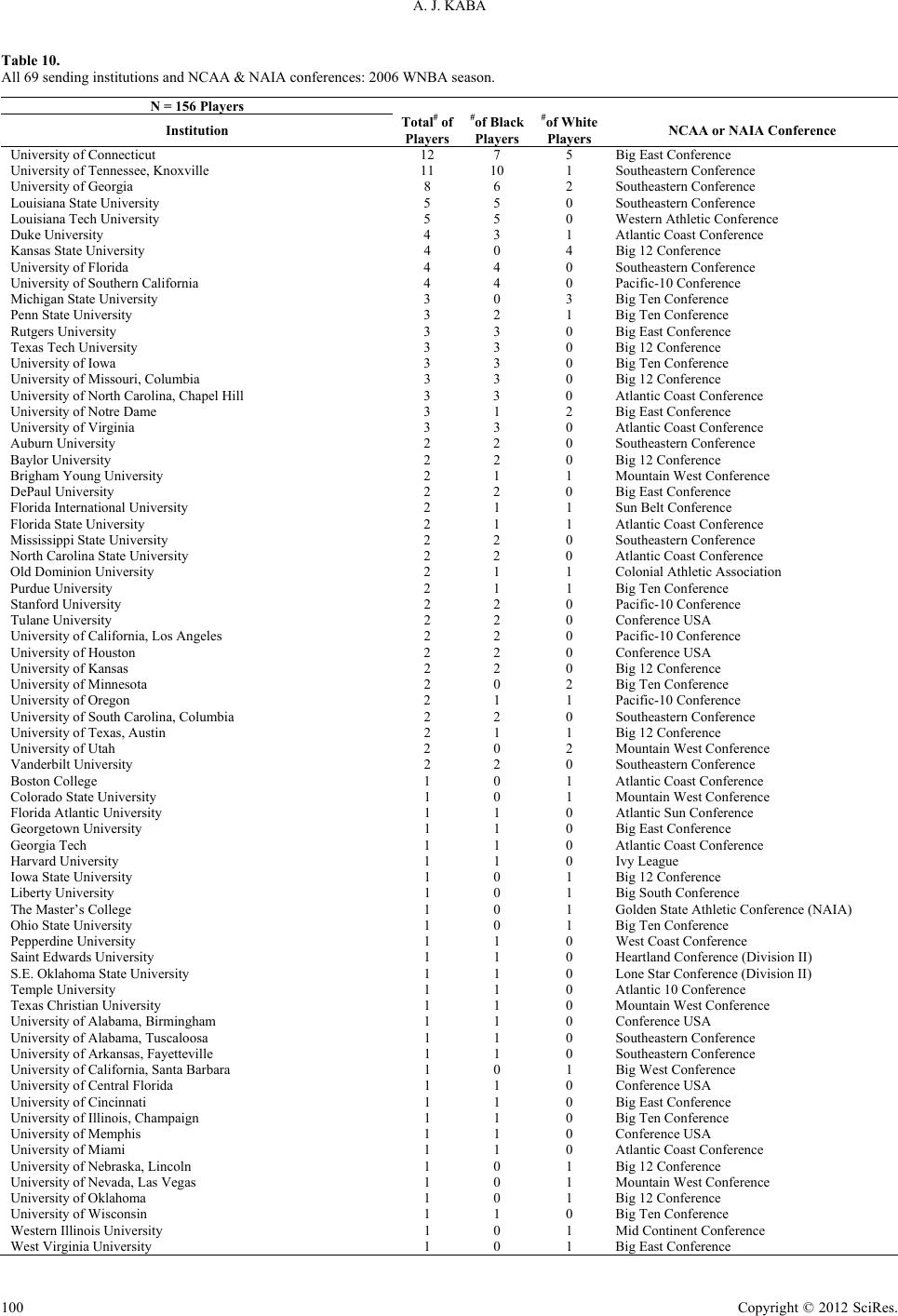

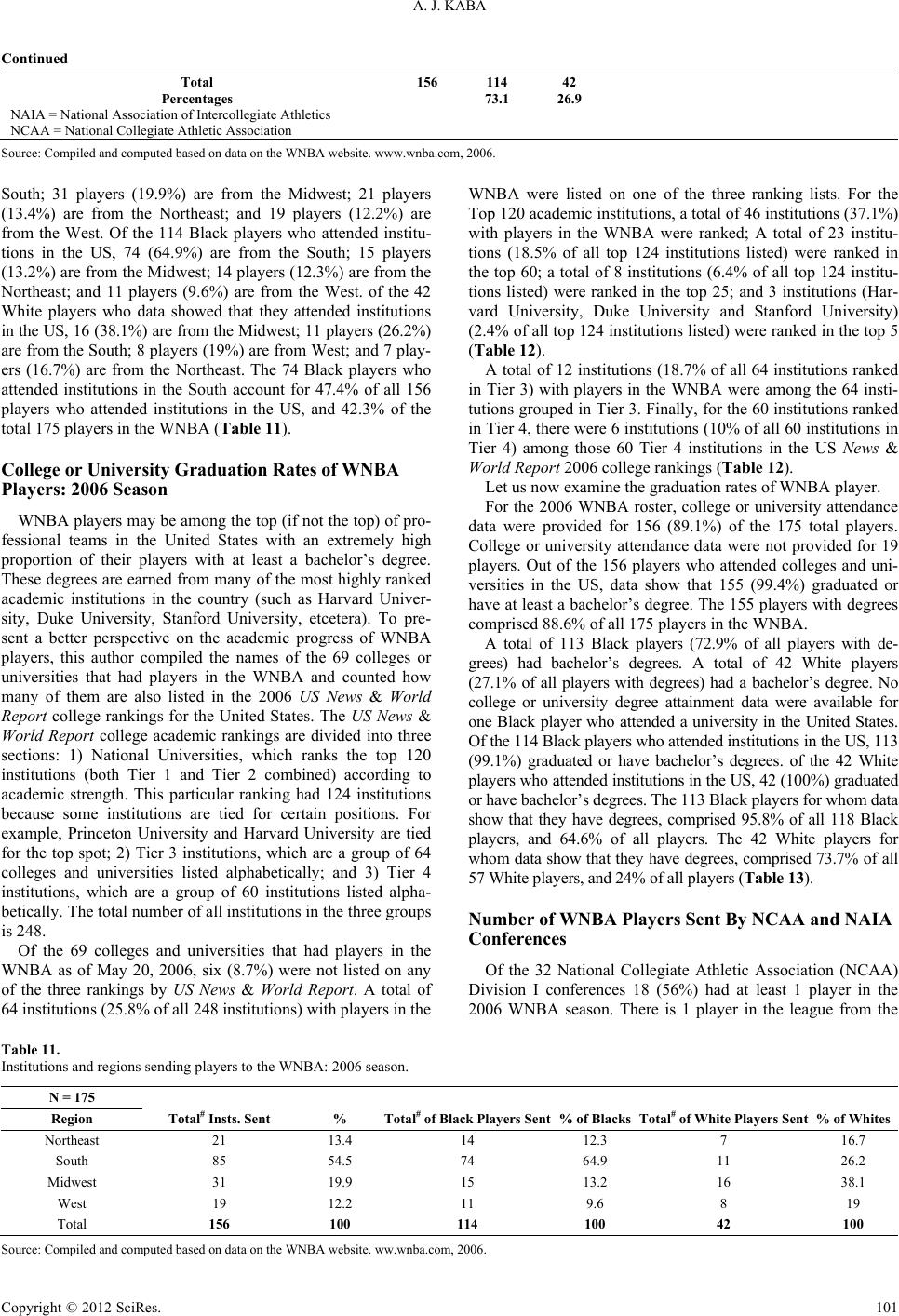

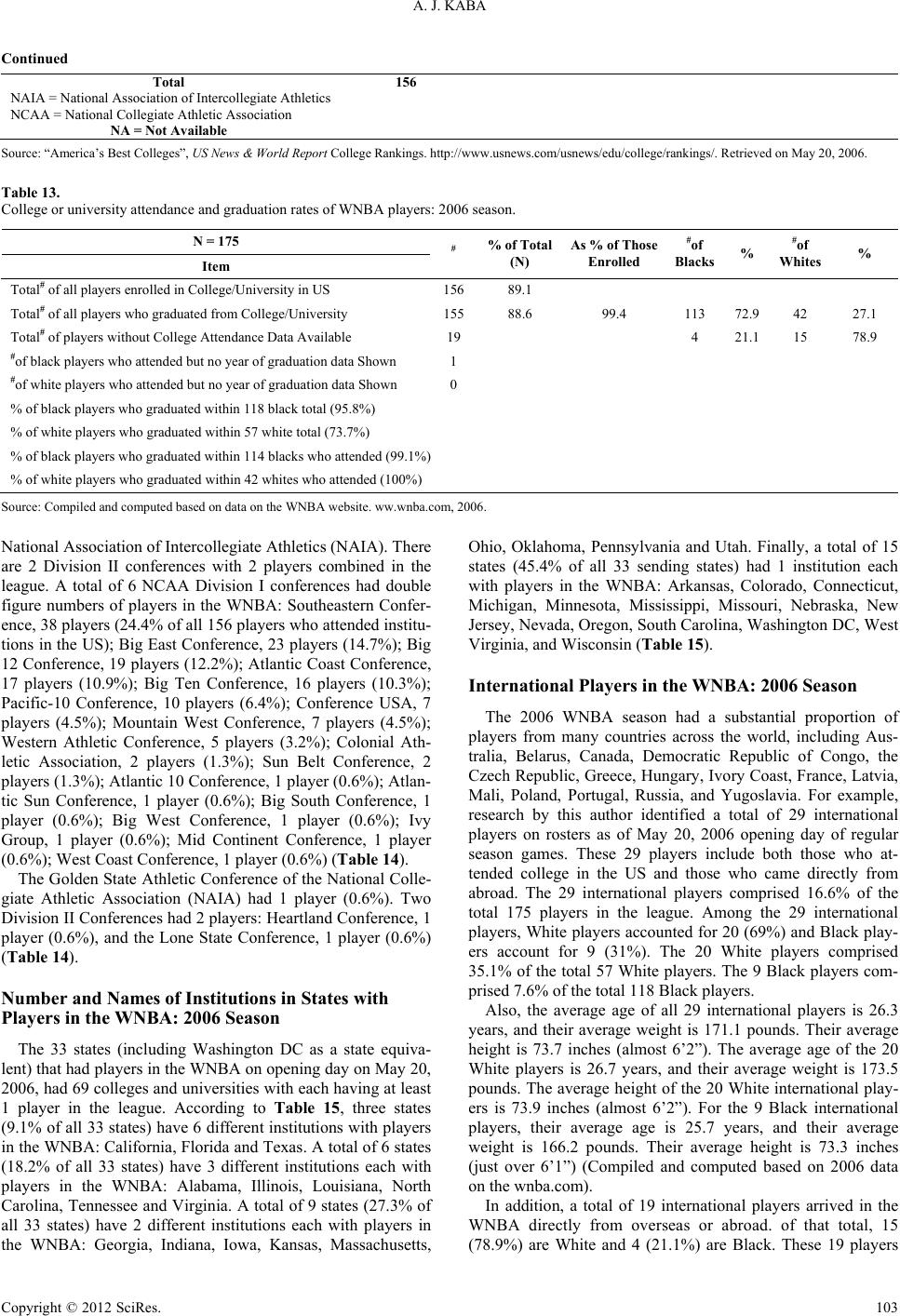

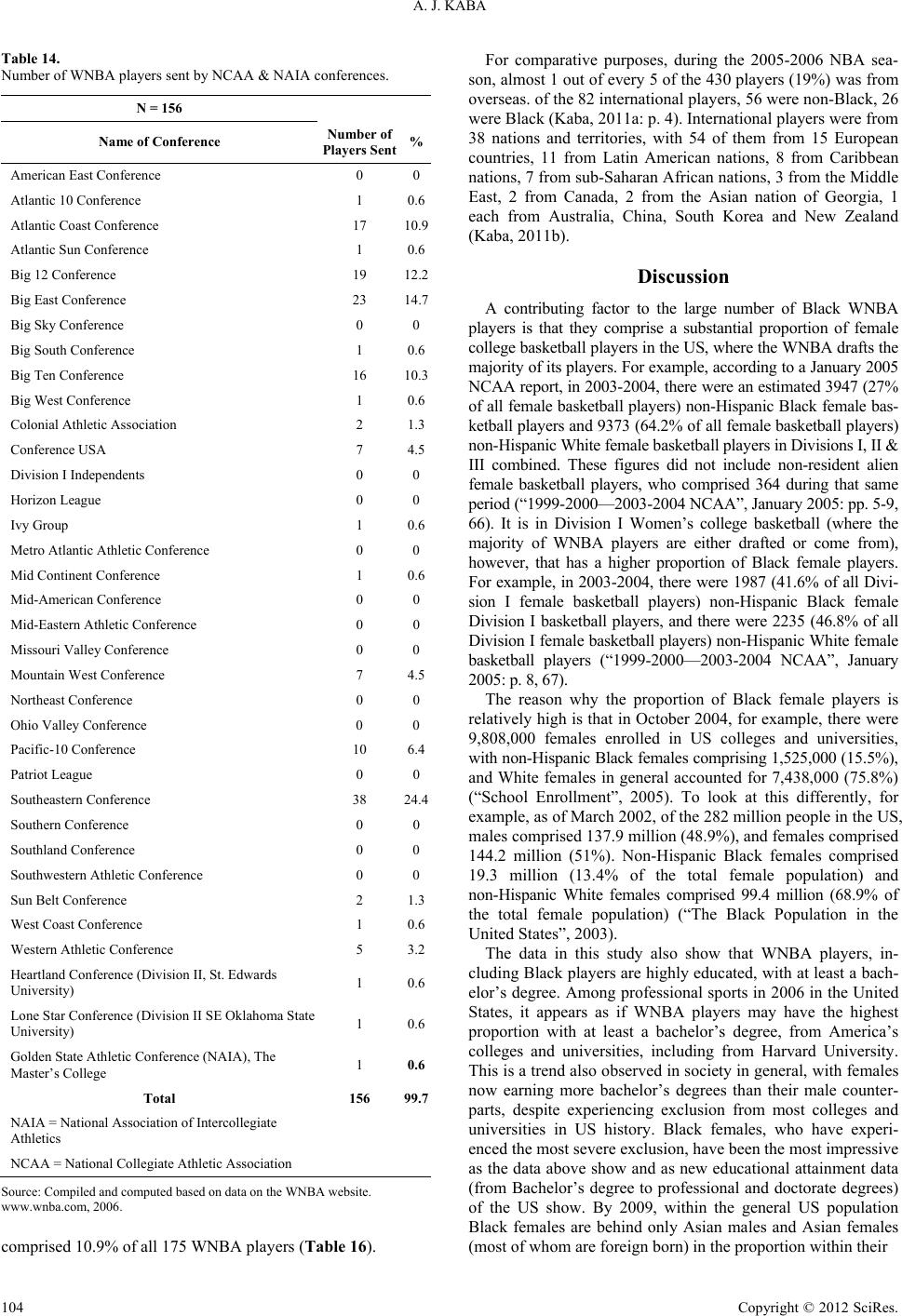

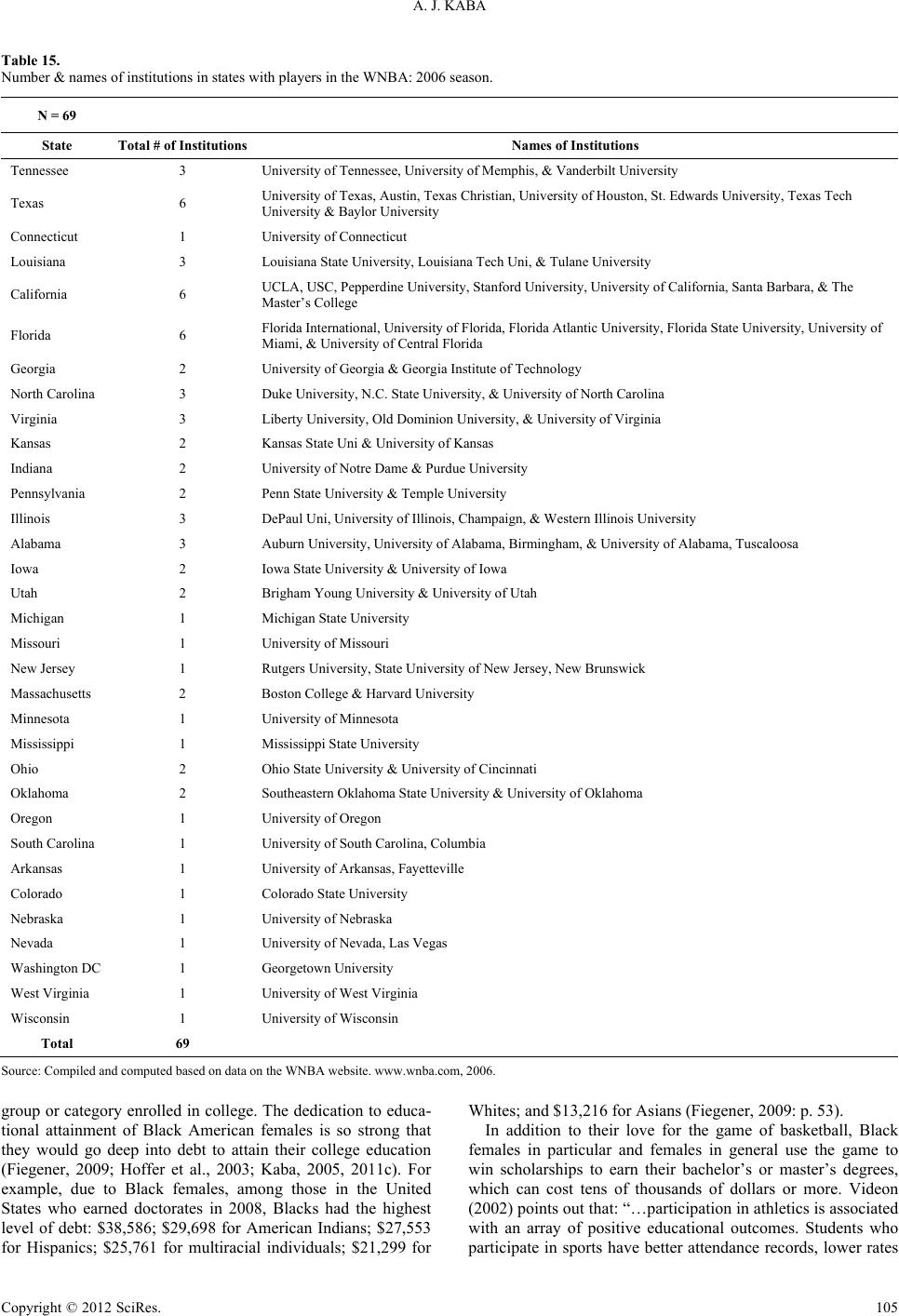

|