Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

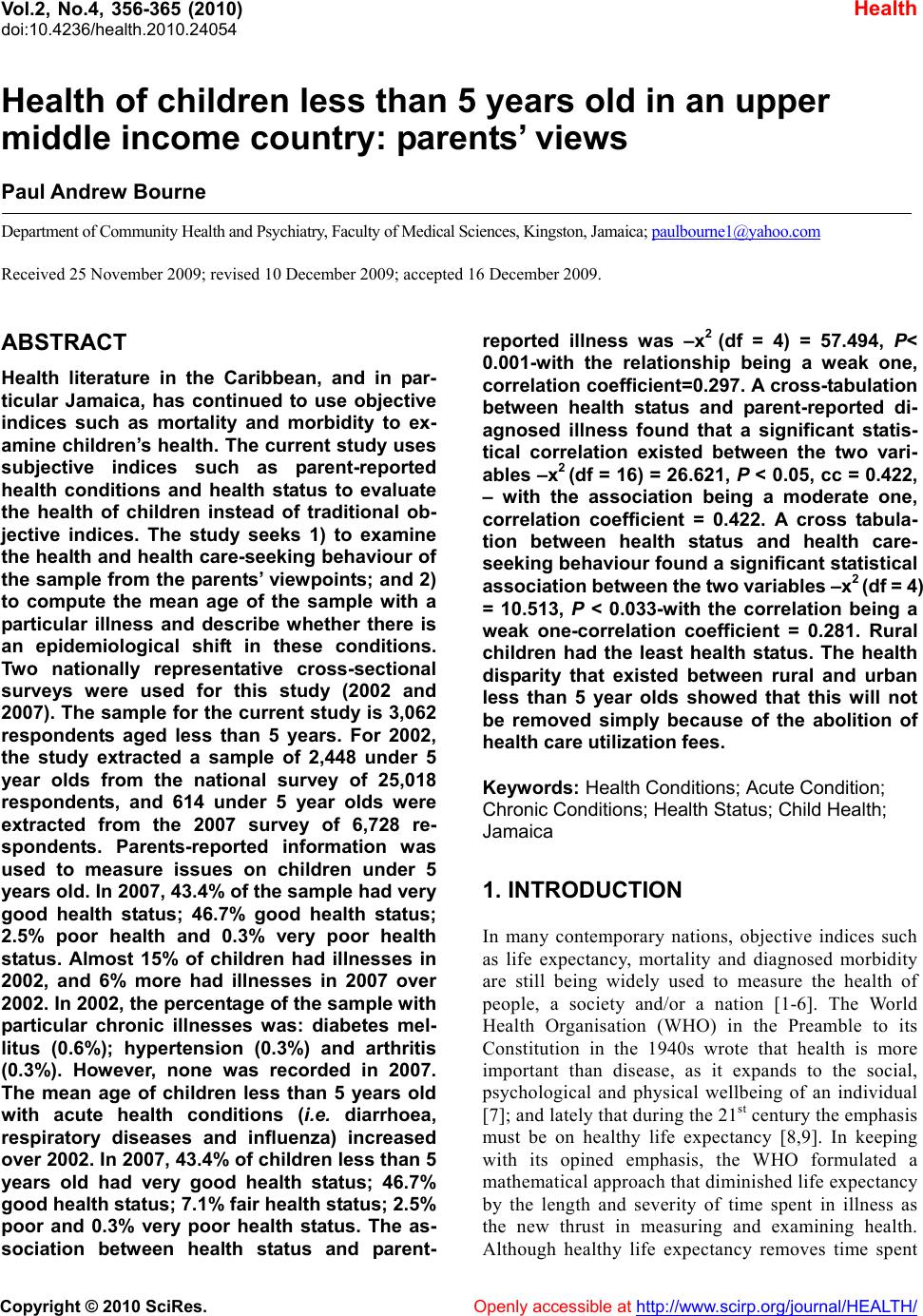

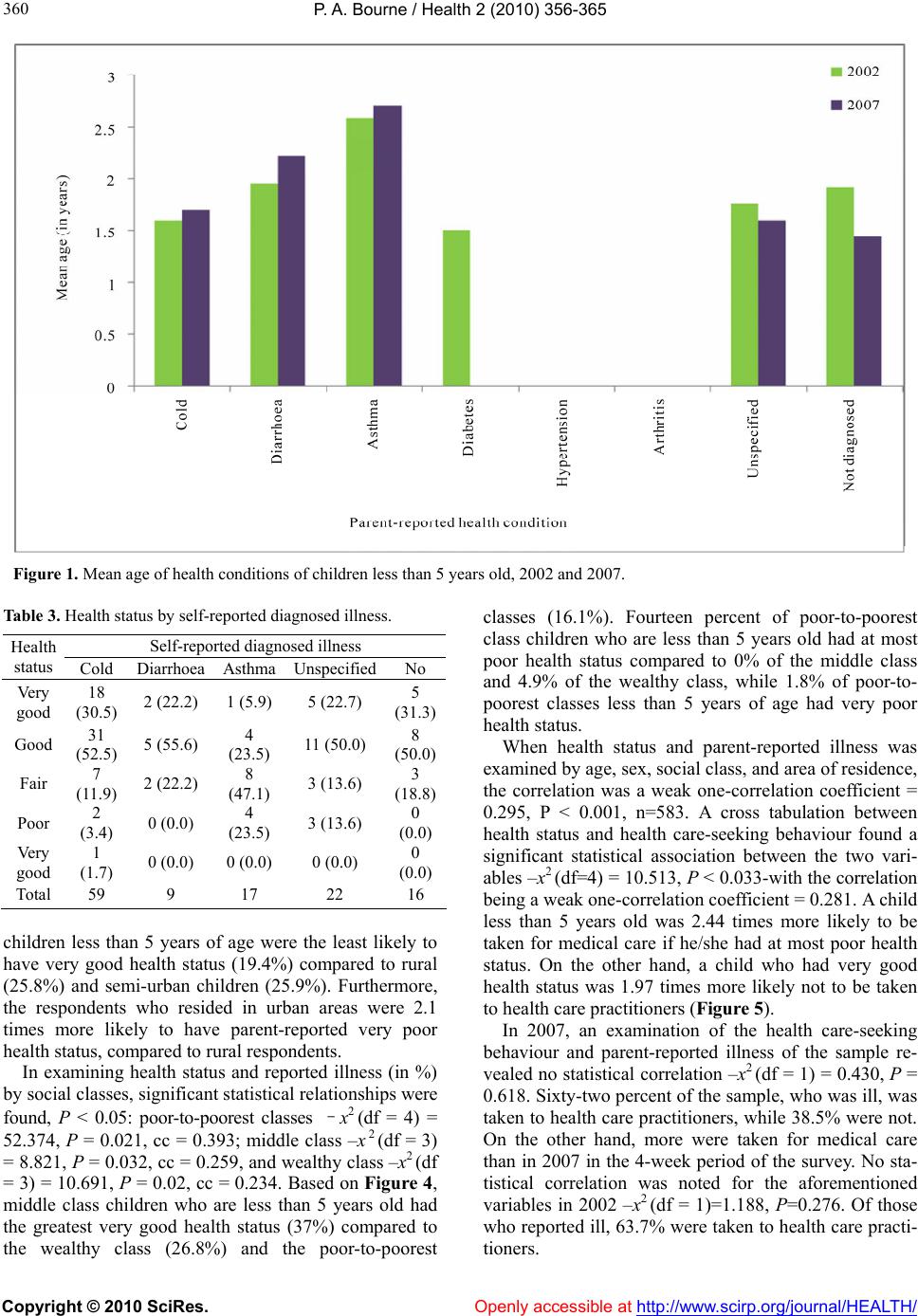

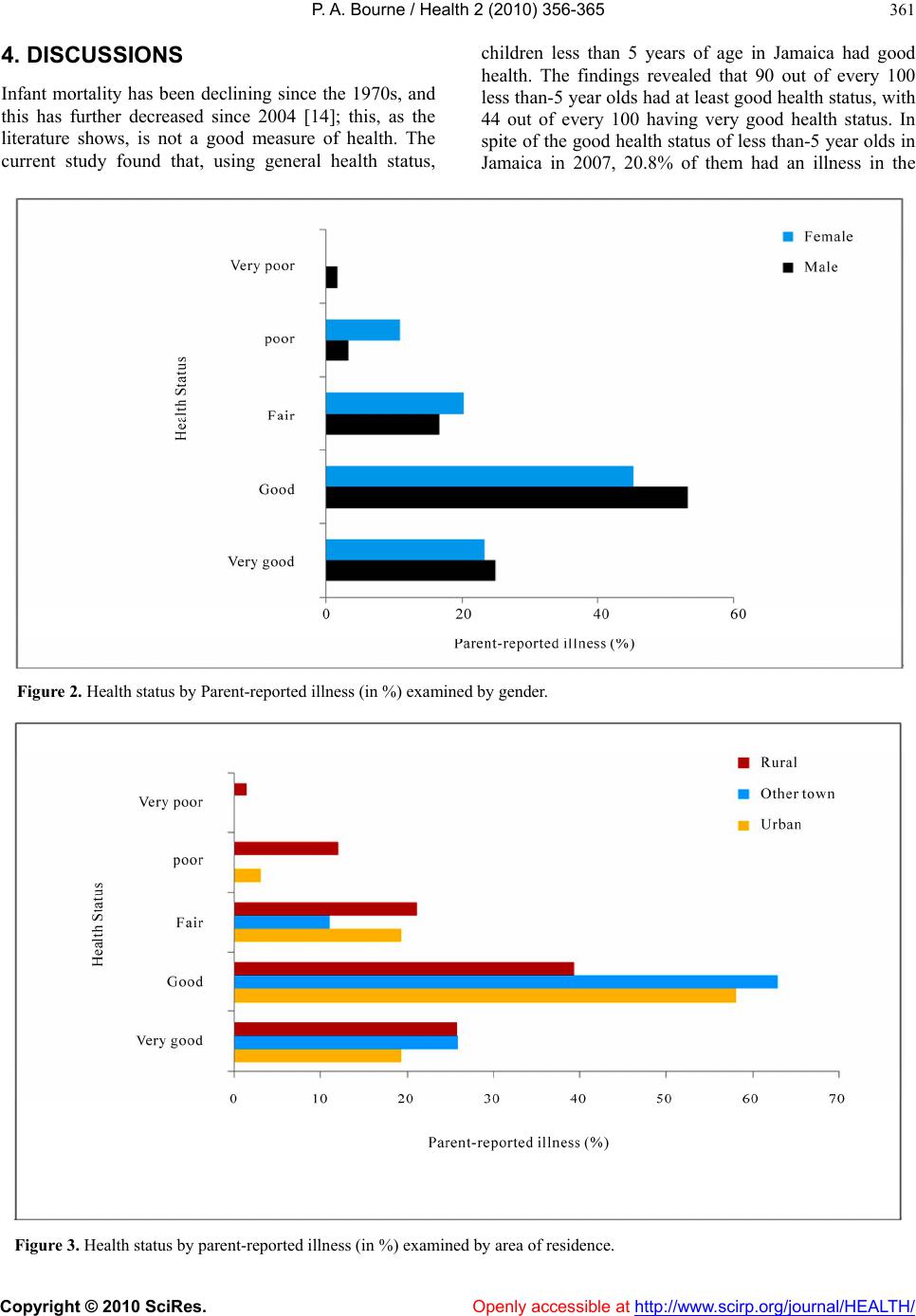

Vol.2, No.4, 356-365 (2010) Health doi:10.4236/health.2010.24054 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health of children less than 5 years old in an upper middle income country: parents’ views Paul Andrew Bourne Department of Community Health and Psychiatry , Faculty of Medical Sciences, Kingston, Jamaica; paulbourne1@yahoo.com Received 25 November 2009; revised 10 December 2009; accepted 16 December 2009. ABSTRACT Health literature in the Caribbean, and in par- ticular Jamaica, has continued to use objective indices such as mortality and morbidity to ex- amine children’s health. The current study uses subjective indices such as parent-reported health conditions and health status to evaluate the health of children instead of traditional ob- jective indices. The study seeks 1) to examine the health and health care-seeking behaviour of the sample from the parents’ viewpoints; and 2) to compute the mean age of the sample with a particular illness and describe whether there is an epidemiological shift in these conditions. Two nationally representative cross-sectional surveys were used for this study (2002 and 2007). The sample for the current study is 3,062 respondents aged less than 5 years. For 2002, the study extracted a sample of 2,448 under 5 year olds from the national survey of 25,018 respondents, and 614 under 5 year olds were extracted from the 2007 survey of 6,728 re- spondents. Parents-reported information was used to measure issues on children under 5 years old. In 2007, 43.4% of the sample had very good health status; 46.7% good health status; 2.5% poor health and 0.3% very poor health status. Almost 15% of children had illnesses in 2002, and 6% more had illnesses in 2007 over 2002. In 2002, the percentage of the sample with particular chronic illnesses was: diabetes mel- litus (0.6%); hypertension (0.3%) and arthritis (0.3%). However, none was recorded in 2007. The mean age of children less than 5 years old with acute health conditions (i.e. diarrhoea, respiratory diseases and influenza) increased over 2002. In 2007, 43.4% of children less than 5 years old had very good health status; 46.7% good health statu s; 7.1% fair health status; 2.5% poor and 0.3% very poor health status. The as- sociation between health status and parent- reported illness was –x2 (df = 4) = 57.494, P< 0.001-with the relationship being a weak one, correlation coefficient=0.297. A cross-tabulation between health status and parent-reported di- agnosed illness found that a significant statis- tical correlation existed between the two vari- ables –x2 (df = 16) = 26.621, P < 0.05, cc = 0.422, – with the association being a moderate one, correlation coefficient = 0.422. A cross tabula- tion between health status and health care- seeking behaviour found a significant statistical association between the t wo variables –x2 (df = 4) = 10.513, P < 0.033-with the correlation being a weak one-correlation coefficient = 0.281. Rural children had the least health status. The health disparity that existed between rural and urban less than 5 year olds showed that this will not be removed simply because of the abolition of health care utilization fees. Keywords: Health Conditions; Acute Condition; Chronic Conditions; Health Status; Child Health; Jamaica 1. INTRODUCTION In many contemporary nations, objective indices such as life expectancy, mortality and diagnosed morbidity are still being widely used to measure the health of people, a society and/or a nation [1-6]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) in the Preamble to its Constitution in the 1940s wrote that health is more important than disease, as it expands to the social, psychological and physical wellbeing of an individual [7]; and lately that during the 21st century the emphas is must be on healthy life expectancy [8,9]. In keeping with its opined emphasis, the WHO formulated a mathematical approach that diminished life expectancy by the length and severity of time spent in illness as the new thrust in measuring and examining health. Although healthy life expectancy removes time spent  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 357 in illness and severity of dysfunctions, it fundamen- tally rests on mortality. The WHO therefore, instead of moving forward, has given some scholars, who are inclined to use objective indices in measuring health, a guilty feeling about continuing this practice. The Caribbean, and in particular Jamaica, continues to use mortality and morbidity to measure the health of children or infants [1-6]. The use of mortality, morbidity and life expectancy is the practice of Caribbean scholars, and is widely used in Jamaica by the: Ministry of Health (MOHJ) [10]; Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN) [11]; Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) [12]; PIOJ and STATIN [13] as well as the Pan American Health Or- ganization (PAHO) [14] in measuring health. In spite of the conceptual definition opined by the WHO in the Preamble to its Constitution in 1946, the health of chil- dren who are less than 5 years old in Jamaica is still measured primarily by using mortality and morbidity statistics. Recently a book entitled ‘Health Issues in the Caribbean’ [15] had a section on Child Health; however the articles were on 1) nutrition and child health devel- opment [16] and 2) school achievement and behaviour in Jamaican children [17], indicating the void in health literature regarding health cond itions. An extensive review of health literature in the Carib- bean region found no study that has used national survey data to examine the health status of children less than 5 years of age. The current study fills this gap in the lit- erature by examining the health status of children less than 5 years of age using cross-sectional survey data which are based on the views of patients. The objectives of this study are 1) to examine the health and health care-seeking behaviour of the sample; and 2) to evaluate the mean age of the sample with a particular illness and to describe whether there is an epidemiological shift in these conditions. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Sample The current study used two secondary nationally repre- sentative cross-sectional surveys (for 2002 and 2007) to carry out this work. The sub-samples are children less than 5 years old, and th e only criterion for selection was being less than 5 years old. The sample in the current study is 3,062 respondents of ages less than 5 years. For 2002, a sub-sample of 2,448 less than-5 year olds was extracted from the national survey of 25,018 respondents in 2002, and information on 614 less than-5 year olds was extracted from the 2007 survey. The survey (Ja- maica Survey of Living Conditions) began in 1989 to collect data from Jamaicans in order to assess govern- ment policies. Since 1989, the JSLC has added a new module each year in order to examine that phenomenon, which is critical within the nation [18,19]. In 2002, the focus was on 1) social safety nets, and 2) crime and vic- timization, while for 2007, the re wa s no foc u s. 2.2. Methods Stratified random sampling technique was used to draw the sample for the JSLC. This design was a two-stage stratified random sampling design where there was a Primary Sampling Unit (PSU) and a selection of dwell- ings from the primary units. The PSU is an Enumeration District (ED), which comprises a minimum of 100 resi- dences in rural areas and 150 in urban areas. An ED is an independent geographical unit that shares a common boundary. This means that the country was grouped into strata of equal size based on dwellings (EDs). Based on the PSUs, a listing of all the dwellings was made, and this became the sampling frame from which a Master Sample of dwellings was compiled, which in turn pro- vided the sampling frame for the labour force. One third of the Labour Force Survey (i.e. LFS) was selected for the JSLC [18,19]. The sample was weighted to reflect the population of the nation [18-20] . The JSLC 2007 was conducted in May and Augu st of that year; while the JSLC 2002 was administered be- tween July and October of that year. The researchers chose this survey based on the fact that it is the latest survey on the national population, and that that it has data on the self-reported health status of Jamaicans. An administered questionnaire was used to collect the data from parents on children less than 5 years old, and the data were stored, retrieved and analyzed using SPSS for Windows 16.0 (SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL, USA). The ques- tionnaire was modelled on the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) household sur- vey. There are some modifications to the LSMS, as the JSLC is more focused on policy impacts. The question- naire covered areas of socio-demographic variables-such as education; daily expenses (for the past 7 days); food and other consumption expenditures; inventory of dura- ble goods; health variables; crime and victimization; social safety net and anthropometry. The non-response rates for the 2002 and 2007 surveys were 26.2% and 27.7% respectively. The non-response includes refusals and cases rejected in data cleaning. 2.3. Measures Social class: This variable was measured based on the income quintiles: The upper classes were those in the wealthy quintiles (quintiles 4 and 5); the middle class was quintile 3 and the poor were the lower quintiles (quintiles 1 and 2). Age is a continuous variable in years. Health conditions (i.e. parent-reported illness or par- ent-reported dysfunction): The question was asked: “Is this a diagnosed recurring illness?” The answering options are: Yes, Cold; Yes, Diarrhoea; Yes, Asthma; Yes, Diabe- tes; Yes, Hypertension; Yes, Arthritis; Yes, Other; and No.  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 358 Self-rated health status: “How is your health in gen- eral?” And the options were: Very Good; Good; Fair; Poor and Very Poor. Medical care-seeking behaviour was taken from the question ‘Has a health care practitioner, healer or phar- macist been visited in the last 4 weeks? ’ with there being two options: Yes or No. Parent-reported illness status. The question is ‘Have you had any illness other than due to injury (for example a cold, diarrhoea, asthma, hypertension, diabetes or any other illness) in the past four weeks? Here the options were Ye s or No. 2.4. Statistical Analysis Descriptive statistics, such as mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency and percentage were used to analyze the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. Chi-square was used to examine the association be- tween non-metric variables, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test the relationships between metric and non-dichotomous categorical variables, whereas an independent sample t-test was used to ex- amine the statistical correlation between a metric vari- able and a dichotomous categorical variable. The level of significance used in this research was 5% (i.e. 95% confid enc e inte rval ). 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristic of Sample In 2002, the sex ratio was 98.8 males (less than 5 years old) to 100 females (less than 5 years old), which shifted to 116.2 less than-5 year old males to 100 less than-5 year old females. The sample over the 6 year period (2002 to 2007) revealed internal migrations to urban zones (Ta bl e 1 ): In 2002, 59.6% of respondents resided with their parents and/or guardians in rural areas, which declined to 5.07%. The percentage of children less than 5 years of age whose parents were in the poorest 20% fell to 25.4% in 2007 over 29.6% in 2002. In 2007 over 2002, 1.7 times less children less than 5 years of age were taken to public hospitals, compared to 1.2 times less taken to private hospitals (Tab le 1 ). Approximately 6% more children less than 5 years were ill in 2007 over 2002. Based on Tabl e 1, less than-5 year olds with par- ticular chronic illnesses had: diabetes mellitus (0.6%); hypertension (0.3%) and arthritis (0.3%). Howev er, none was recorded in 2007. There were some occasions on which the response rates were less than 50%: In 2002, health care-seeking behaviour was 14.3%; parent-reported diagnosed health conditions, 14.2%; and visits to health care institutions, 8.9% (Table 1). For 2007, the response rate for health care-seeking behaviour was 20.2%; parent-reported di- agnosed health condition s, 20.2%, and less than 11% for cost of medical care. 3.2. Health Conditions Based on Ta b l e 1 , the percentage of less than-5 year olds with particular acute conditions saw a decline in colds and asthmatic cases, as well as chronic conditions. Figure 1 revealed that in 2007 the mean age of children less than 5 years old with acut e health conditions (i. e. diarrhoea, respi- ratory diseases and influenza) increased ov er 2002. On the other hand, the mean age of those with unspecified illnesses declined from 1.76 years (SD = 1.36 years) to 1.64 years (SD = 1.36 years). Concomitantly, the greatest mean age of the sample was 2.71 years (SD = 1.21 years) for asthmatics in 2007 and 2.59 years (1.24 years) in 2002. It should be noted here that the me an age of a child less than 5 years of age in 2002 with diabetes mellitus was 1.50 years (2.12 years). 3.3. Health Status In 2002, the JSLC did not collect data on the general health status of Jamaicans, although this was done in 2007. Therefore, no figures were available for health status for 2002. In 2007, 43.4% of children less than 5 years old had very good health status; 46.7% good health status; 7.1% fair health status; 2.5% poor and 0.3% very poor health status. The response rate for the h ealth status question was 96.9%. Ninety-seven percent of the sample wa s used to exa mine the association between health status and parent- reported illness –x2 (df = 4) = 57.494, P < 0.001-with the rela ti o ns hi p being a weak one, correlation coefficient = 0.297. Tab le 2 revealed that 24.2% of children less than 5 years of age who reported an illness had very good health status, com- pared t o 2 times more of th ose wh o did no t repo rt an ill ness. One percent of parents ind icated that their children (of le ss than 5 years) who had no illness had poor health status, compared to 5.6 times more of those with illness who had poor health status. 3.4. Health Conditions, Health Status and Medical Care-Seeking Behaviour A cross-tabulation between health status and parent- reported diagnosed illness found that a significant statis- tical correlation existed between the two variables –x2 (df =16)=26.621, P < 0.05, cc=0.422, -with the associa- tion being a moderate one, correlation coefficient=0.422 (Ta b l e 3 ). Based on Ta b l e 3 , children less than 5 years old with asthma were less likely to report very good health status (5.9%), compared to those with colds (30.5%); diarrhoea (22.2%); and unspecified health con- ditions (22.7%). When health status by parent-reported illness (in %) was examined by gender, a significant statistical rela- tionship was found, P < 0.001: males –x2 (df = 4)  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 359 Table 1. Socio-demographic characteristic of sample, 2002 and 2007. 2002 2007 Variable n % n % Sex Male 1216 49.7 330 53.7 Female 1231 50.3 284 46.7 Income quintile Poorest 20% 725 29.6 156 25.4 Poor 554 22.6 140 22.8 Middle 474 19.4 126 20.5 Wealthy 402 16.4 117 19.1 Wealthiest 20% 293 12.0 75 12.2 Self-reported illness Yes 345 14.9 125 20.8 No 1969 85.0 475 79.2 Visits to health care facilities (hospitals) Private, yes 17 7.8 5 6.7 Public, yes 100 46.3 20 26.7 Area of residence Rural 1460 59.6 311 50.7 Semi-urban 682 27.9 125 20.4 Urban 306 12.5 178 29.0 Health (or, medical) care-seeking behaviour Yes 221 63.3 76 61.3 No 128 36.7 48 38.7 Health insurance coverage Yes, privat e 211 9.0 66 11.1 Yes, public * * 33 5.5 No 2123 91.0 496 83.4 Self-reported diagnosed health conditions Acute Cold 185 53.3 60 48.4 Diarrhoea 20 5.8 9 7.3 Asthma 46 13.3 17 13.7 Chronic Diabetes mellitus 2 0.6 0 0 Hypertension 1 0.3 0 0 Arthritis 1 0.3 0 0 Other (unspecified) 54 15.6 22 17.7 Not diagnosed 38 11.0 16 12.9 Number of visits to health care institutions 1.53 (SD = 0.927 ) 1.43 (SD = 0.989 ) Duration of illness Mean (SD) 8.51 days (6.952 days) 8.07 days (7.058 d ays) Cost of medical care Public facilities Median (Range) in USD 2.36 (157.26)1 0.00 (64.62)2 Private facilities Median (Range) in USD 13.76 (117.95)1 10.56 (49.71)2 1USD1.00 = Ja. $50.87; 2USD1.00 = Ja. $80.47 *In 2002, all health insurance coverage was private and this was change in 2005 to include some public option. =25.932, P < 0.05, cc = 0.320, and f emales –x2 (df = 4) = 39.675, P < 0.05, cc = 0.356. The health statuses of males less than 5 years old in the very good and good categories were greater than those of females (Figure 2). However, the females had greater health statuses in fair and poor health status than males, with more males re- porting very poo r healt h stat us t han females. Based on Figure 3, even after controlling health status and parent-reported illness (in %) by area of residence, a significant statistical association was found: urban –x2 (df = 3) = 10.358, P < 0.05, cc = 0.238; semi-urban –x2 (df = 3) = 9.887, P = 0.021, cc = 0. 273, and rural –x2 (df = 3) = 45.978, P < 0.001, cc = 0.365. Concomitantly, Table 2. Health status by self-reported illness. Self-reported illness Health status Yes n (%) No n (%) Very good 30 (24.2) 227 (48.3) Good 61 (49.2) 217 (46.2) Fair 23 (18.5) 19 (4.0) Poor 9 (7.3) 6 (1.3) Very poor 1 (0.1) 1 (0.2) Total 124 470 x2 (df = 4) = 57.494, P < 0.001, cc = 0.297, n = 594  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 360 Figure 1. Mean age of health conditions of children less than 5 years old, 2002 and 2007. Table 3. Health status by self-reported diagnosed illness. Self-reported diagnosed illness Health status Cold Diarrhoea Asthma Unspecified No Very good 18 (30.5) 2 (22.2) 1 (5.9) 5 (22.7) 5 (31.3) Good 31 (52.5) 5 (55.6) 4 (23.5) 11 (50.0) 8 (50.0) Fair 7 (11.9) 2 (22.2) 8 (47.1) 3 (13.6) 3 (18.8) Poor 2 (3.4) 0 (0.0) 4 (23.5) 3 (13.6) 0 (0.0) Very good 1 (1.7) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) 0 (0.0) Total 59 9 17 22 16 children less than 5 years of age were the least likely to have very good health status (19.4%) compared to rural (25.8%) and semi-urban children (25.9%). Furthermore, the respondents who resided in urban areas were 2.1 times more likely to have parent-reported very poor health status, compared to rural respondents. In examining health status and reported illness (in %) by social classes, significant statistical relationships were found, P < 0.05: poor-to-poorest classes –x2 (df = 4) = 52.374, P = 0.021, cc = 0.393; middle class –x 2 (df = 3) = 8.821, P = 0.032, cc = 0.259, and wealthy class –x2 (df = 3) = 10.691, P = 0.02, cc = 0.234. Based on Figure 4, middle class children who are less than 5 years old had the greatest very good health status (37%) compared to the wealthy class (26.8%) and the poor-to-poorest classes (16.1%). Fourteen percent of poor-to-poorest class children who are less than 5 years old had at most poor health status compared to 0% of the middle class and 4.9% of the wealthy class, while 1.8% of poor-to- poorest classes less than 5 years of age had very poor health status. When health status and parent-reported illness was examined by age, sex, social class, and area of residence, the correlation was a weak one-correlation coefficient = 0.295, P < 0.001, n=583. A cross tabulation between health status and health care-seeking behaviour found a significant statistical association between the two vari- ables –x2 (df=4) = 10.513, P < 0.033-with the correlation being a weak one-correlation coefficient = 0.281. A child less than 5 years old was 2.44 times more likely to be taken for medical care if he/she had at most poor health status. On the other hand, a child who had very good health status was 1.97 times more likely not to be taken to health care practitioners (Figure 5). In 2007, an examination of the health care-seeking behaviour and parent-reported illness of the sample re- vealed no statistical correlation –x2 (df = 1) = 0.430, P = 0.618. Sixty-two percent of the sample, who was ill, was taken to health care p ractitioners, while 38.5% were no t. On the other hand, more were taken for medical care than in 2007 in the 4-week period of the survey. No sta- tistical correlation was noted for the aforementioned variables in 2002 –x2 (df = 1)=1.188, P=0.276. Of those who reported ill, 63.7% were taken to health care practi- tioners.  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 361 4. DISCUSSIONS Infant mortality has been declining since the 1970s, and this has further decreased since 2004 [14]; this, as the literature shows, is not a good measure of health. The current study found that, using general health status, children less than 5 years of age in Jamaica had good health. The findings revealed that 90 out of every 100 less than-5 year olds had at least good h ealth status, with 44 out of every 100 having very good health status. In spite of the good health status of less than-5 year olds in Jamaica in 2007, 20.8% of them had an illness in the Figure 2. Health status by Parent-reported illness (in %) examined by gender. Figure 3. Health status by parent-reported illness (in %) examined by area of residence.  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) **-** Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 362 Figure 4. Health status by parent-reported illness (in %) examined by social classes. Figure 5. Health status by health care-seeking behaviour. 4-week period of the survey, which is a 5.9% increase over 2002. It is interesting to note the shift in this study away from specific chronic illnesses. In 2002, 30 out of every 1,000 less than-5 year olds in Jamaica were diag- nosed with hypertension and arthritis (i.e. parentre- ported), with 60 out of 1,000 having been parent-reported with diabetes mellitus. None such cases were found in 2007, suggesting that in the case of the children who had  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 363 363 those particular ch ronic illnesses, their parents had eith er migrated with them or they had died. Concomitantly, the country is seeing a reduction in children less th an 5 years old with colds; however, marginal increases were seen in diarrhoea, asthma and unspecified health conditions over the last 6 years. Although there were increased reported cases of illness over the studied period, in 2007, 62 out of every 100 ill children were taken to medical practi- tioners, and this fell from 64 in every 100 in 2002. One of the arguments put forward by some people is that what retards or abates health care-seeking behaviour is medical cost. With the abolition of health care user fees for children since 2007, the culture must be playing a role in parents and/or guardians not taking children who are ill to medical care facilities for treatment. Medical cost cannot be divorced from the expenditure that must be incurred in taking the child to the health care facility. In 2007, 25 out of every 100 children less than 5 years of age had parents and/or guardians who were less than the poverty line. Although this has de- clined by 4.2% since 2002, it nevertheless means that there are children whose parents are incapacitated by other factors. Marmot [21] opined that the financial in- ability of the poor is what accounts for their lowered health status, compared to other social classes. The cur- rent study concurs with the findings of Marmot, as it was revealed that children less than 5 years of age from poor households had the least health status. This means that poverty is not merely eroding the health status of poor Jamaicans, but that equally it is decreasing the health status of poor children. Rural poverty in Jamaica is at least twice as great as urban poverty, and approximately 4 times more than semi-urban [13], which provides another explanation for the poor health status of ch ildren less than 5 years of age. The current study found that 3.2% of those children dwelling in urban zones recorded at most poor health status, compared to 13.6% of rural children, suggesting that the health status of the latter group is 4.3 times worse than the former. This means that poverty in rural zones is exponential, eroding the quality of life of chil- dren who are less than 5 years old. Poverty in semi-ur- ban areas was 4% which is 2.5 times less than that for the nation; and those less than 5 years of age recorded the greatest health status, supporting Marmot’s perspec- tive that poverty erodes the health status of a people. Hence, the decline in health care-seeking behaviour for this sample is embedded in the financial constraints of parents and/or guardians as well as their geographical challenges. The terrain in rural zones in Jamaica is such that medical care facilities are not easily accessible to residents compared to urban dwellers. With this terrain constraint comes the additional financial burden of at- tending medical care facilities at a location which is not in close proximity to the home of rural residents, and this accounts for the vast health disparity between rural and urban children. As a result of the above, the removal of health care utilization fees for children less than 18 years of age does not correspond to an increased utiliza- tion of medical care services, or lowered numbers of unhealthy children less than 5 years of age. If rural par- ents are plagued with financial and location challenges, their children will not have been immunized or properly fed, and their nutritional deficiency would explain the health disparity that exists between them and urban chil- dren who have easier access to health care facilities. The removal of health care utilization fees is not syn- onymous with an increased utilization of medical care for children less than 5 years old, as 46.5% of the sample attended public hospitals fo r treatment in 2002, and after the abolitio n of user fees in April 2007 utilization fell by 1.7 times compared to 2002. In order to understand stand why there is a switch from health care utilization to mere survival, we can examine the inflation rate. In 2007, the inflation rate was 16.8% which is a 133% increase over 2002 (i.e. 7.2%), which translates into a 24.7% increase in the prices of food and non-alcoholic beverages, and a 3.4% increase in health care costs [22]. Here the choice is between basic necessities and health care utilization, which further erodes health care utilization in spite of the removal of user fees for children. Health status uses the individual self-rating of a per- son’s overall health status [23], which ranges from ex- cellent to poor. Health status therefore captures more of people’s health than diagnosed illness, life expectancy, or mortality. However, how good a measure is it? Em- pirical studies show that self-reported health is an indi- cator of general health. Schwarz & Strack [24] cited that a person’s judgments are prone to systematic and nn-systematic biases, suggesting that it may not be a good measure of health. Diener, [25] however, argued that the subjective index seemed to contain substantial amounts of valid variance, indicating that subjective measures provide some validity in assessing health, a position with which Smith concurred [26]. Smith [26] argued that subjective indices do have good construct validity and that they are a respectably powerful predic- tor of mortality risks [27], disability and morbidity [27], though these properties vary somewhat with national or cultural contexts. Studies have examined self-reported health and mortality, and have found a significant corre- lation between a subjective and an objective measure [27-29]: life expectancy [30]; and disability [2 8]. Bourne [30] found that the correlation between life expectancy and self-reported health status was a strong one (correla- tion coefficient, R=0.731); and that self-rated health ac- counted for 53% of the variance in life expectancy. Hence, the issue of the validity of subjective and objec- tive indices is good, with Smith [26] opining that the construct validity between the two is a good one. The current research found that parent-reported illness and the health status of children less than 5 years of age  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 364 are significantly correlated. However, the statistical as- sociation was a weak one (correlation coefficient=0.297), suggesting that only 8% of the variance in health status can be explained by parent-reported children’s illnesses. This is a critical finding which reinforces the position that self-reported illnesses (or health conditions) only constitute a small proportion of people’s health. There- fore, using illness to measure the health status of chil- dren who are less than 5 years of age is not a good measure of their health, as illness only accounts for 8% of health status. However, based on Bourne‘s work [30], health status is equally as good a measure of health as life expectancy. One of the positives for the using of health status instead of life expectancy is its coverage in assessing more of people’s general health status by using mortality or even morbidity data. 5. CONCLUSIONS In summary, the general health status of children who are less than 5 years old is good; however, social and public health programmes are needed to improve the health status of the rural population, which will translate into increased health status for their children. The h ealth disparity that existed between rural and urban children less than 5 years of age showed that this will not be re- moved simply because of the abolition of health care utilization fees. In keeping with this reality, public health specialists need to take health care to residents in order to further improve the health status of children who are less than 5 years old. 5.1. Conflict of Interest The author has no conflict of interest to report. 5.2. Disclaimer The researcher would like to note that while this study used secondary data from the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions, 2007, none of the errors that are within this paper should be ascribed to the Planning Institute of Ja- maica or the Statistical Institute of Jamaica as they are not there, but owing to the researcher. REFERENCES [1] Lindo, J. (2006) Jamaican perinatal mortality survey, Jamaica Ministry of Health. Kingston, 1-40. [2] McCarthy, J.E. and Evans-Gilbert, T. (2009) Descriptive epidemiology of mortality and morbidity of health-indi- cator diseases in hospitalized children from western Ja- maica. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hy- giene, 80, 596-600. [3] Domenach, H. and Guengant, J. (1984) Infant mortality and fertility in the Caribbean basin. Cah Orstom (Sci Hum), 20, 265-72. [4] Rodriquez, F.V., Lopez, N.B., and Choonara, I. (2002) Child health in Cuba. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 93, 991-3. [5] McCaw-Binns, A., Holder, Y., Spence, K., Gordon- Strachan, G., Nam, V., and Ashley, D. (2002) Multi- source method for determining mortality in Jamaica: 1996 and 1998. Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, University of the West Indies. International Biostatistics Information Services. Division of Health Promotion and Protection, Ministry of Health, Jamaica. Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Kingston. [6] McCaw-Binns, A.M., Fox, K., Foster-Williams, K., Ashley, D.E., and Irons, B. (1996) Registration of births, stillbirths and infant deaths in Jamaica. International Journal of Epidemiology, 25, 807-813. [7] World Health Organization (1948) Preamble to the Con- stitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, June 19-22, 1946; signed on July 22, 1946 by the representa- tives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, 2, 100) and entered into force on April 7, 1948. “Constitution of the World Health Organization, 1948.” In Basic Documents, 15th Edion, World Health Organization, Geneva. [8] World Health Organization (2004) Healthy life expec- tancy 2002: 2004 world health report. World Health Or- ganization, Geneva. [9] World Health Organization (2000) WHO issues new healthy life expectancy rankings: Japan number one in new ‘healthy life’ system. World Health Organization, Washington D. C. & Geneva. [10] Jamaica Ministry of Health (1992-2007) Annual report 1991-2006. Jamaica Ministry of Health, Kingston. [11] Statistical Institute of Jamaica (1981-2009) Demographic statistics, Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Kingston. [12] Planning Institute of Jamaica (1981-2009) Economic and social survey. Planning Institute of Jamaica, Kingston. [13] Planning Institute of Jamaica and Statistical Institute of Jamaica (1989-2009) Jamaica Survey of Living Condi- tions, 1988-2008. PIOJ and STATIN, Kingston. [14] Pan American Health Organization (2007) Health in the Americas, volume II Countries. PanAmericanHealth Organization, Washington DC. [15] Morgan, W. Ed. (2005) Health issues in the Caribbean. Ian Randle, Kingston. [16] Walker, S. (2005) Nutrition and child health develop- ment. In Morgan, W. Ed., Health issues in the Caribbean, Ian Randle, Kingston, 15-25. [17] Samms-Vaugh, M., Jackson, M., and Ashley, D. (2005) School achievement and behaviour in Jamaican children. In Morgan, W. Ed. Health issues in the Caribbean, Ian Randle, Kingston, 26-37. [18] Statistical Institute of Jamaica. (2008) Jamaica survey of living conditions, 2007, Kingston, Jamaica. Statistical Institute of Jamaica, Planning Institute of Jamaica and Derek Gordon Databank, University of the West Indies, Kingston, Jamaica. [19] Statistical Institute of Jamaica. (2003) Jamaica survey of living conditions. Statistical Institute of Jamaica, King- ston, Planning Institute of Jamaica and Derek Gordon Databank, University of the West Indies. [20] World Bank, Development Research Group, (2002).  P. A. Bourne / Health 2 (2010) 356-365 Copyright © 2010 SciRes. Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 365 365 Poverty and human resources. Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions (LSLC) 1988-2000: Basic Information. [21] Marmot, M. (2002) The influence of income on health: Views of an Epidemiologist. Does money really matter? Or is it a marker for something else? Health Affair, 21, 31-46. [22] Bourne, P.A. (2009) Impact of poverty, not seeking medical care, unemployment, inflation, self-reported illness, health insurance on mortality in Jamaica. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1, 99-109. [23] Kahneman, D. and Riis, J. (2005) Living, and thinking about it, two perspectives. In Huppert, F. A., Kaverne, B. and N. Baylis, The Science of Well-Being, Oxford Uni- versity Press. [24] Schwarz, N. and Strack, F. (1999) Reports of subjective well-being: Judgmental processes and their methodo- logical implications. In Kahneman, D., Diener, E., Schwarz, N. Eds., Well-Being: The Foundations of He- donic Psychology. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 61-84. [25] Diener, E. (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-75. [26] Smith, J. (1994) Measuring health and economic status of older adults in developing countries. Gerontologist, 34, 491-6. [27] Idler, E.L. and Benjamin, Y. (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21-37. [28] Idler, E.L. and Kasl, S. (1995) Self-ratings of health: Do they also predict change in functional ability? Journal of Gerontology, 50, S344-S353. [29] Schechter, S., Beatty, P., and Willis, G.B. (1998) Ask- ing survey respondents about health status: Judgment and response issues. In Schwarz, N., Park, D., Knauper, B., and Sudman, S. Eds., Cognition, Aging, and Self- Reports, Taylor and Francis, Ann Arbor. [30] Bourne, P.A. (2009) The validity of using self-reported illness to measure objective health. North American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1, 232-238. |