Open Journal of Safety Science and Technology, 2011, 1, 11 5-128 doi:10.4236/ojsst.2011.13013 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojsst) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST Re-Strategising for Effective Health and Safety Standards in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Ikechukwu A. Diugwu Department of Project Management Technology, Federal University of Technology, Minna, Nigeria E-mail: hushilld@aim.com Received September 15, 2011; revised October 28, 2011; accepted November 5, 2011 Abstract Poor health and safety record impact on the image/reputation and operational capabilities of businesses, es- pecially those within the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector. Given the role of SMEs in the economy, this paper attempts to highlight the issue of poor health and safety performance of the SME sector and sug- gest a strategy for improving the level of performance. To this end, survey questionnaires were distributed to assess the overall awareness of people about health and safety issues, motivations and constraints, vis-a-viz supply chain improvement initiatives. Based on the findings (responses from questionnaires) and existing literature, the unique characteristics of the supply chain network makes it a suitable medium through which health and safety improvement in small and medium-sized enterprises can be realised. Additionally, the findings show that good health and safety management culture enhances image, lowers costs, and improves the overall competitiveness of organisations. To complement the efforts/desires of health and safety regula- tors, there is need to leverage on the relationships that exist in supply chains, shown in this exercise to have a major influence on the activities of organisations. Keywords: Health and Safety Management, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, SMEs, Supply Chain 1. Introduction There are indications that in spite of the contribution of the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector to na- tional economies, efforts at improving health and safety standard of this sector have not produced intended results. This conclusion is informed by th e noticeable gaps in the implementation of health and safety laws, and compli- ance with these laws by SMEs [1], and the greater chal- lenges encountered by SMEs in developing and main- taining health and safety programmes than their larger counterparts [2-6]. Some of these challenges include the difficulties experienced by SMEs in the interpretation of regulations [7], th e recogn ition of relevant reg u lations , or even in their willingness to liaise with regulators [8]. In the past, different strategies have been used to enhance performance of SMEs [9,10]. While some of these inter- ventions were not successful [11], others were inappro- priate and of poor quality such that SMEs became unre- sponsive to them [12 ]. As a result, the suitability o f these strategies has been questioned [13]. Hence, there is a need to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies aimed at enhancing the awareness of, and compliance with safety and health legislations in business sectors (e.g. SMEs) with low compliance rates [14]. Equally important is the exploration of other health and safety improvement ini- tiatives [15] that would enab le SMEs to benefit from the initiatives, knowledge an d capabilities of others [9]. The need for this alternative improvement strategy, especially in health and safety, is predicated on the fact that workplace safety requires not only technical inter- ventions, but also the adoption of management, organisa- tional, and training instruments that can influence risk behaviour [16]. It has been argued that if sound man- agement principles had been applied to health and safety management, it would have been realised early enough that the coercive forces of inspections by regulatory agencies as the sole tool for promoting good health and safety practices in smaller businesses was no longer ef- fective; and it was no longer advisable to rely so much on it [17]. The ineffectiveness of this strategy has been attributed to the few inspectors assigned to monitor so many businesses, which are often distributed over a wide geographical area; a situation that makes the SME sector  I. A. DIUGWU 116 a “hard to reach” one [18]. Again, in view of the fact that workers in a unionised environment are more likely to exercise their rights over health and safety at work issues than their non-unionised counterparts [19], it would be proper to assume that the absence of organised trade un- ions in many small organisations impacts on the extent to which employees influence decisions on health and safe- ty related matters within their organisations. Similarly, the fear of being punished for poor performance affects the willingness of SMEs to seek help and information from sources perceived as having regulatory or enforce- ment powers. Thus, additional levers and supports are needed if regulations were to be effective in ensuring be- tter health and safety arrangements and outcomes in small businesses. Consequently, if the challenges of pre- ventive health and safety in small businesses were to be dealt with effectively, an alternative to regulation is to explore those social and economic factors that influence organisational behaviour, even if they are indirectly as- sociated with occupational health and safety [20]. Undoubtedly, these tools and resources are better ac- cessed through channels familiar to SMEs, which offers greater degrees of trust, loyalty and comfort [21], than through regulatory agencies/bodies such as the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). The supply chain network meets these criteria and should be explored if SMEs were to become fully aware of, and committed to health and safety performance improvement initiatives. Thus, link- ing health and safety to economically significant aspects of work in which the self-interest of small business em- ployers can be manipulated to improve their health and safety arrangements becomes a positive way of achieving the results, that seemingly elude the more traditional ap- proaches to compliance [20]. The conviction that supply chain influences represent a good improvement strategy is further strengthened by research findings which show that SMEs regard social networks as important channels through which they can access knowledge and informa- tion, and are keen to join or establish networks with key customers [22]. Although anecdotal evidence suggests that the business case for a better health and safety man- agement is yet to be fully appreciated by many SMEs, HSM remains an important aspect of business manage- ment [23]; successful organisations are known to actively manage all aspects of their businesses, including health and safety [24]. This paper identifies an effective way to improve heal- th and safety management in SMEs, thus minimising the variously acknowledged [25,26] impact of lost working days due to accidents at work and ill health on a nation’s economy. Although large organisations may have reser- vations over the benefits of activ ely participating in heal- th and safety improvement initiatives in SMEs, the risks from supply interruption (ranging from delivery to qual- ity problems) is enormous [27]. These views when con- sidered within the context of a heav ily ou tsourced market economy, justifies the interest in, and the investment in supply chain health and safety improvement. If perfor- mance of suppliers in the lower tiers of supply chains impact on the competitiveness of organisations across the entire chain [12], then, the degree to which a company manages its supply chain becomes a major determinant to its success [28]. Engaging in supply chain health and safety improvement activities would serve as a further demonstration of the commercial benefits of good health and safety management (HSM) to businesses, especially SMEs [15] where investments in health and safety im- provement activities are still regarded as undesirable costs rather than as investments. The diverse nature of SMEs is such that most coun- tries do not have an officially recognised single defini- tion of what constitutes an SME [29,30], making the definition of what co nstituted an SME a problematic one [31]. This notwithstanding, most definitions of an SME have been based on a combination of turnover, balance sheet total, or number of employees. In spite of these disparities, there is unanimity in acceptance and recogni- tion of the vital ro le played by th e SME sector in shap ing the economy of nations through the provision of new ideas, products, services, and most significantly jobs [32-37]. However, in spite of the strategic role played by the SME sector, there is a scarce knowledge about health and safety in that sector [38]; making HSM in SMEs to be relatively understudied and underserved [6]. This has led to the poor level of HSM evident in the sector [13]. This poor HSM culture may have contributed to the sig- nificantly higher rates and fatality of accidents in SMEs than in large enterprises [39,40]. 2. Materials and Methods 2.1. Study Area An area probability sampling tech nique [41,42] was ado- pted for this study. In consideration of the fact that there are over 4 million business enterprises in the United Kingdom [34], it was not feasible to survey every busi- ness enterprise. Consequently, multistage cluster samp- ling was applied in this study. To do this, a geographic location was defined in line with the sugg estion by M. J. Baker [43]. The survey sample was geographically re- stricted and data for the analysis were gathered through survey questionnaires distributed to businesses in two major cities in West Midlands, UK (Coventry and Bir- mingham). Within this geographic cluster, questionnaires Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU117 were also distributed to organised groups such as the Coventry and Warwickshire Safety Group, and the Bir- mingham Health, Safety and Environment Association. A simple random sampling technique was used to choose enterprises to be polled fro m enterprise listed in the App - legate directory within these cities. Furthermore, the sur- vey covered only a relatively small section of the popu- lation. This was informed by the fact that in surveys where the target population is large, a smaller percentage of the population is needed to achieve the same level of accuracy. This decision is in line with established guide- lines on this subject [44]. 2.2. Data Assembly and Management The questionnaire (Appendix 1) sought to ascertain the respondent’s views on varying health and safety issues and was divided into eight sections viz: Section A: Basic company information; Section B: Awareness of health and safety manage- ment; Section C: Existe nce of heal th and safety policy ; Section D: Motivations for health and safety manage- ment; Section E: Constraints to health and safety manage- ment; Section F: Improvement support from industrial net- work/customers; Section G: Supplier assessment and evaluation; Section H: Supplier development and improvement support available. The questions asked were based on find ings from lite- rature review in health and safety management, partner- ships and collaborations within supply chain networks. The data were complied and analysed using SPSS statis- tical software; and being an exploratory research, analy- ses were mostly frequency analysis of relevant of vari- ables. 3. Results and Discussion 3.1. Distribution of Respondents Out of 450 que stionnaires that were dist ributed, 12 1 wer e returned, with 112 valid responses, representing a 26.9% response rate. Although low response rates can signifi- cantly affect the accuracy of survey estimates [45], a 26.9% response rate although low, is in line with the response rates reported in other postal surveys and stud- ies [6,17, 46-48]. Table 1 below shows that 16 respondents were from micro companies, 17 from small enterprises, 38 from medium enterprises, and 41 from large enterprises. This provided a very good mix as the survey aimed to obtain views across the different sectors and enterprise sizes. It could be seen that greater number of respondents was from the construction industry. This can be attributed to the high level of health and safety awareness creation activities in the construction industry, which has led to fewer inhibitions/scepticisms, making organisations to open about their health and safety problems than organi- sations in other sectors. 3.2. Implications of Level of Health and Safety Standards Table 2 below is the distribution of views on the impact of poor health and safety standard on business image and operations. About 108% or 94.7% of the 114 valid re- sponses specified that poor health and safety perform- ance impacts on their business operations, while 6 (5.3%) felt it had no impact. A further 103 (92.0%) of 112 valid responses felt that it had a negative impact on their busi- ness image, while 9 (8.0%) felt that poor health and safety does not impact negatively on their business im- age. The findings presented in Table 2 are consistent with observations that poor health and safety standard affect the operations and image of businesses; and by implica- tion their economic viability. Th ere is an ob serv ation th at many organizations are becoming ever more cautious of threats posed to their business operations by the health Table 1. Distribution of respondents by business sector and enterprise size. Enterprise Size Sector 1 - 9 10 - 49 50 - 249 250+ Total Construction 3 7 14 14 38 Service 7 2 6 9 24 Manufacturing 3 5 11 9 28 Others 3 3 7 9 22 Total 16 17 38 41 112 Table 2. Impact of poor health and safety on image and operations. Impact on business operations Impact on business image Enterprise size Yes No Total Yes No Total 1 - 9 12 4 16 11 4 15 10 - 49 15 2 17 16 1 17 50 - 249 40 0 40 37 3 40 250 + 41 0 41 39 1 40 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST 118 and safety performance of their customers [49]. For in- stance, poor health and safety standards could lead to a reduction in the number of contracts awarded to an or- ganization by highly health and safety conscious organi- zations, as these organizations recognize that there may be increased costs as a result of compensations, exten- sion of projects, as well as change in project plans due to closures caused by accidents and ill health. To forestall the negative effects of this, these organizations now take proactive steps to ensure that problems with their bought- in supplies or services do not affect their reputatio ns [23] or operations. Thus, in view of increasing level of com- petition among organizations, there is need for suppli- ers/contractors to maintain a relatively good health and safety record in order to remain on the preferred supplier list of their customers. The impact of health and safety standard on the image and operations of an organization is further highlighted by the fact that a poor safety standard leads to loss of manpower while good health and safety standard lead s to low staff turn-over (i.e., increased ability to retain staff, and job satisfaction) [23]. The implication of this is that poor health and safety standard leads to less manpower, higher level of compensation, and reluctance by people to work for an organization, shown to be indifferent to the welfare (including health and safety) of its employees. This corroborates the view that successful organizations pay as much attention to health and safety management as they do to other aspects of their business activities [50]. As shown in Figure 1, it is evident that the p rotection of image as a motivator is as important to SMEs as it is to large organizations. Thus, an awareness of the cost implications of poor health and safety standards as noted in earlier works [51-55], becomes a motivation for im- proved safety performance. This finding reinforces the need for larger organizations to offer improvement sup- port to their associates in order to protect themselves from the negative impact of their safety performance as suggested by [56] . A non-parametric chi-square test (Table 3 below) was carried out to establish if there was any relationship among poor health and safety standards, the image and operations of an organization. The large chi-square sta- tistics of 91.26 (impact on business operations) and 78.89 (impact on business image) and the small signifi- cance level (p < 0.001) indicate an unlikelihood that these variables are independent of each other. Thus, a relationship among the levels of safety standard, image as well as operations of a business exists. 3.3. Access to Information Table 4 below is a breakdown according to enterprise size of responses on sources of information. This analy- sis helps to establish those sources where organizations can get help and information from. It also assesses the advantages and limitations of these sources with a view to determining the most effective way of commun icating with organizations, especially SMEs, on health and safety issues. It is evident from Table 4 that a small percentage of Enterprise size 1-9 10-49 50-249 250+ Frequency of response 403020100 Small extent Moderate extent Great extent Figure 1. Distribution of image protection as a motivator.  I. A. DIUGWU Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST 119 Table 3. Relationship among poor health and safety, busi- ness operation and image. Impact on business operations Impact on business image Chi-Square (a,b) 91.263 78.893 Df 1 1 Asymp. Sig. 0.000 0.000 (a) 0 cells (0%) have expected frequencies less than 5. The minimum ex- pected cell frequency is 57.0; (b) 0 cells (0%) have expected frequencies less than 5. The minimum expected cell frequency is 56.0. Table 4. Source of health and safety information. Response by Enterprise s iz e (%) Source of information 1 - 9 10 - 49 50 - 249250+ Trade Unions 6.7 0.0 15.0 19.5 HSE/Website 46.7 64.7 77.5 95.1 Health and safety journals 80.0 70.6 82.5 92.7 Local Authority 40.0 35.3 12.5 24.4 Industrial network/saf e t y groups 40.0 47.1 80.0 92.7 Head office 6.7 0.0 17.5 36.6 micro and small businesses relied on trade unions as a preferred source of information on health and safety; the use of Trade Unions as a source of information increases with enterprise size. This outcome is expected because the peculiar nature of SMEs discourages trade unionism. Also, observations from an earlier study [57] which noted a limited success with this form of intervention, rules this option out. Furthermore, the Safety Represen- tatives and Safety Committees Regulations 1977 (SRSC Regulations 1977) of The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, allowed only organizations with organized trade unions to appoint health and safety representatives. Thus, trade unions or to some extent employee pressure groups cannot be relied upon to influence the attitude of the management of organizations towards improvement in its health and safety standard or performance, as the very nature of SME does not encourage the formation of trade unions. A further examination of the data in Table 4 shows that organizations use the Health and Safety Executive, and its website, health and safety journ als, and industrial network/safety groups as sources of information on health and safety matters more than other sources. The data suggest that fewer respondents preferred industrial network and safety groups as sources of information than the other two sources. However, as would be seen from the discussions below on the inherent limitations to these sources, industrial networ ks and safety group s could be a better media for information dissemination. Although a substantial number of SMEs use the Heal- th and Safety Executive, its website, and Local Authori- ties as sources of information, the data presented in Ta- ble 4 above s how that th e prefer ence for th e use of thes e sources, especially the HSE and its website, increases with enterprise size. This is not surprising as findings from literature portray SMEs as having higher rates of accidents than larger enterprises [39,58,59]; amounting to lower standard of health and safety in smaller enter- prises compared to their larger counterparts [13,60]. Ob- viously, the fear of being punished because of this high level of accidents and poor health and safety standards/ records discourages SMEs (and indeed other organiza- tions) from seeking advice and help from sources that are perceived as having regulatory, and or enforcement po- wers) [61,62]. Consequently, these sources (e.g. Health and Safety Executive or Local Authorities) may neither be suitable nor effective channels of preaching health and safety improvement to organizations, especially SMEs. These limitations notwithstanding, it could still be ar- gued that SMEs could rely on the information contained in the Health and Safety Executive’s website (or infor- mation gateway) for help, guidance and advice on health and safety issues. While this argument seems compelling, it has been observed variously that a high volume gate- way information service has a minimal impact on the intended recipients compared to an intensive advisory system governed by mutual agreement between stake- holders [63,64]. This implies that the websites of health and safety regulators may not, after all, be the best way to influence improved health and safety performance in organizations, especially SMEs. Even in the circum- stance that these SMEs are able to access needed infor- mation from the health and safety regulators’ websites, it is still doubtful if the small enterprise sector has enough resources (personnel and otherwise) that would ensure utilization of the information so accessed, to solving their everyday business problems. In consideration of the fact that these guidance materials have failed to address the needs of businesses, there is a clear need to produce more sector specific guidance, perhaps with co-operation from professional representatives or trade bodies [65]. Again, in a survey carried out in the United Kingdom, an overwhelming major ity (82%) of respondents felt that they need ed more training on the use of the intern et [66]. Consequently, although information on health and safety issues are readily available on the internet, it is still not considered the most effective means of disseminating health and safety information because so many people do not yet know how to effectively use ICT equipment and facilities. This view is substantiated by the result of an- other survey which shows that although both social and electronic networks were both important channels through  I. A. DIUGWU 120 which SMEs can acquire knowledge, social networks with their key customers’ or buying customers by or- ganizations was preferred by SM Es [2 2 ] . The reliance upon safety journals for information on health and safety, although cited by many as a source of information may not be as effective as it seems. For this medium to produce the desired result, the person using it should have a certain level of health and safety manage- ment awareness. However, from Figure 2, it could be seen that many SMEs cited lack knowledge of details and implications of health and safety legislation, as well as of complexity of h ealth and safety legislatio n as major obstacles to the implementation of effective health and safety management systems in their organizations. Thus, a considerable level of outside h elp would be required by small organizations for them to effectively interpret and utilise the information contained in these journals. The use of this source of information could also be affected by lack of resources (human, and or financial), which is also shown as a major constraint in Figure 2. While the findings from this survey suggest that sources of information (in increasing order of preference) are industrial networks/safety groups, HSE/website, and health and safety journals, the limitations of these sour- ces are such that the use of industrial network/safety group seems most effective. For instance, there is an ar- gument that in order to engage SMEs to the level that would guarantee the achievement of the level of im- provement desired, there is a need to utilize those chan- nels with which SMEs are already familiar with [20,21]; more so when it has been noted that SMEs regard social networks as channels through which they can access im- portant improvement information [22]. 3.4. Strategies for Improving Health and Safety Table 5 contains a breakdown of responses by organiza- tions on their strategies for improving health and safety in their supply chains, while Table 6 contains responses on specific improvement activities implemented. The findings in Table 5 suggest that many companies either belonged to a network which encourages the ex- change of best practices, or carried out activities that are aimed at improving health and safety standards of their suppliers. This claim is however contradicted by the re- latively small number of companies that carry out ac- tual supplier/network improvement initiatives as shown in Table 6. This discrepancy could, perhaps, be ex- plained by the fact that most companies do not have this set down as an absolute requirement by their parent companies. The implication of this finding is that there is a need, not only for organizations to be interested in is- sues that relate to the health and safety performance of their suppliers, but also for a corporate mandate to en- force it. Thus, in order to benefit from the above, organizations must be engaged in those activities listed on Table 6 which, unfortunately as shown by the level of positive responses, leave much to be desired. There are inferences from literature pointing to the i mportance of these activi- ties, as the acquisition and development of knowledge are determinants to successful business strategies [67]. Networks, partnerships, and collaborations are proven sources of knowledge acquisition and dissemination; re- Figure 2. Health and safety management constraints. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU121 Table 5. Strategies for supply chain he alth and safe ty management. Yes Total % We rate health and safety performance as highly as cost 34 68 50.0 Interested in supply c hain improvement initiative 56 102 54.9 Educate our suppliers through written materials 37 67 55.2 Part of industry specific pa rtnership that shares good practice 68 111 61.3 We set health and safety criteria for our suppliers 44 67 65.7 Formal assessment of suppliers’ health and safety perfor mance 43 65 66.2 Informal assessment of suppliers’ health and safety performance 46 67 68.7 Part of network that share s go o d practice 86 110 78.2 Health and safety performance forms part of our sub-contract conditions 59 68 86.8 Table 6. Specific partnership improvement activities. Yes Total % We go into our suppliers’ com panies to help them improve health and safety 16 68 23.5 Benefited from improvement workshops and education from customers 26 109 23.9 Run workshops/sem i nars to educate our suppliers 21 67 31.3 Part of supply chain initiati v e i n v o l v ed in active dialogue with suppliers/stakeholder s 36 111 32.4 Have received guidance from customers 41 111 36.9 Interested in participation in supply chain improvem ent initiative 33 67 49.3 Communicate to suppliers our health and sa fety criteria for goods and se rvices we buy51 65 78.5 gular meetings and workshops among network members increase the level, frequency of direct contact, as well as know-how of stakeholders [68,69]. However, these meet- ings and work shops will not produce the desired result if there is no meaningful and effective communication be- tween organizations, because communication has been noted as playing a vital role in the sustenance of com- petitive advantage by orga nizations [70-74]. 3.5. Probable Improvement Strategy An analysis of factors that motivate improvement in health and safety standards in organizations shows that SMEs are motivated more by the requirement or encour- agement from their key customers than by the influence of legislation (Figure 3 below). This is in line with conclusions drawn from other studies [75]. In a study on environmental supply chain management, supply chain pressure was recognised as an external influence/driving factor for environment man- agement [46]. Similarly, the impact of customer influ- ences has been attested to by small businesses in UK who had achieved BS 5750 standard [76]. The utilisation of supply chain influences as an im- provement strategy seems plausible as major clients are known to have influenced the implementation of specific improvement ideas by their suppliers, when compliance with these requirements become pre-conditions to re- maining on the list of preferred suppliers/contractors [17]. The implementation, monitoring and evaluation of im- provement activities under the proposed strategy would be easily and seamlessly integrated into existing com- pany practices as large companies are known to have set, and demanded adherence to certain requirements that should be met by their suppliers [75]. It is also observed that good practices could be cascaded from major clients to suppliers [15]. There are instances where this stance has influenced the performance in health and safety management by suppliers [12,17]. Aside this requirement, there is an observed need for larger enterprises to en- courage and support HSM initiatives in SMEs as a way of minimising the negative impact of accidents on an entire business sector [56], because the competitive ad- vantage of organizations is now dependent on the ability to leverage on capabilities inherent in supply chains, as competitions are now between entire value chains [77]. 4. Conclusions and Recommendations This paper has explored factors that deter SMEs from effectively managing health and safety within their or- ganizations. It should be noted that in spite of the role of SMEs in the economic well-being of nations, there is still very little literature on health and safety management in Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST 122 Figure 3. Comparison between legislation and requirement/encouragement as motivators. SMEs. Although efforts have been made in the past to improve the health and safety performance of SMEs, these initiatives were ineffective. It suffices to note that although there are many avenues through which organi- zations can access information on health and safety, there was however a reluctance by organizations (especially SMEs) to approach health and safety regulators and go- vernment agencies for help, out of a fear of being pun- ished for poor health and safety performance. It was also established that lack of resources, expertise, management commitment, absence of perceived financial benefit, as well as complex legislations affect both the desire by, and ability of an organization to improve on its health and safety standard. Despite these constraints, it is evi- dent that while supply chain pressure was influential in bringing about improvements in organizations, it was practices such as collaborations and partnerships that en- hance this. For instance, the survey results suggest that a substantial number of organizations relied on industrial networks for information and support on health and safety matters. Conclusively, the expressed desire by larger organiza- tions to help their smaller business partners improve their safety performances should be capitalised upon. None- theless, it is equally important that steps are taken to en- sure that this goes beyond a mere expression of intent; activities capable of bringing about these desired im- provements should be identified, developed and imple- mented. These findings serve as further justification of the need to bring larger and smaller companies together in collaborative ventures aimed at improving their com- petitiveness. To these end, if larger organizations are as concerned about their images and reputations as the finding from this study shows, then they show a greater willingness to help their less capable and resource handi- capped smaller business partners improve their opera- tions, as a way of forestalling any ugly situation. This is because the less capable organizations (mostly smaller organizations) are more receptive to improvement ideas recommended to them, or demanded by their bigger as- sociates for fear of losing out on contracts. Since this work is exploratory, further work is needed to fully ascertain the effectiveness of using the supply chain pressure to drive forward safety improvement ini- tiatives in SMEs and to douse the fears entertained by larger firms on the feasibility of this strategy. While this fear by businesses is appreciated, it is dwarfed by the fact that knowledge acquisition bestows certain level of com- petitive advantage to members of a supply chain; and the ability to absorb and transfer knowledge affords advan- tages that exceed any result from cost saving strategies alone. This work can be further extended through the development of a re-strateg isin g (supply ch ain health and safety improvement) framework. 5. References [1] R. C. Lefebvre and L. Rochlin, “Social Marketing,” In: K.  I. A. DIUGWU123 Glanz, F. M. Lewis and B. K. Rimer, Eds., Health Be- havior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2 Edition, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 1997. [2] EIM, “Health and Safety at Work,” EIM Business & Policy Research, Zoetermeer, 1998. [3] European Commission, “A Self-Evaluation Handbook for SMEs,” Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 1995. [4] European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, “Comparative Report on Job Qual- ity in Microfirms, (Unpublished National Reports on UK, Sweden, Greece and France),” European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, Dublin, 2000. [5] European Industrial Relations Observatory, “Survey of Company Accident Rates,” 1999, http://www.eiro.eurofund.ie [6] D. Stokols, S. McMahan, C. Clitheroe and M. Wells, “Enhancing Corporate Compliance with Worksite Health and Safety Legislation,” Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2001, pp. 441-463. doi:10.1016/S0022-4375(01)00063-9 [7] L. Vassie, J. M. Tomas and A. Oliver, “Hea lth and Safety Management in UK and Spanish SMEs: A Comparative Study,” Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2000, pp. 35-43. doi:10.1016/S0022-4375(99)00028-6 [8] J. Borley, “A Healt h and Safety System Whic h Works for Small Firms,” Journal of the Royal Society for Health, Vol. 117, No. 4, 1997, pp. 211-215. doi:10.1177/146642409711700403 [9] T. J. N. M. de Bruijn and P. S. Hofman, “Pollution Pre- vention in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: Evoking Structural Changes through Partnerships,” Greenleaf Publishing Ltd., Sheffield, 2001, pp. 71-82. [10] European Network for Workplace Health Promotion, “Small, Healthy and Competitive: New Strategies for Im- proved Health in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises,” BKK Federal Association, Essen, 2001. [11] D. Walker and R. Tait, “Health and Safety Management in Small Enterprises: An Effective Low Cost Approach,” Safety Science, Vol. 42, No. 1, 2004, pp. 69-83. doi:10.1016/S0925-7535(02)00068-1 [12] E. Rhodes and R. Carter, “Collaborative Learning in Ad- vanced Supply Systems: The Klass Pilot Project,” The Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 15, No. 6, 2003, pp. 271-279. doi:10.1108/13665620310488566 [13] R. Bibbings “Strategy for Meeting the Occupational Safe- ty and Health Needs of Small and Medium Size Enter- prises (SMEs)—A Summary of ROSPA’s Views,” Safety Science Monitor, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2003, pp. 1-13. [14] P. L. Polakoff, “An Oversight Report: Senate Bill 198 Impact and Effectiveness on Workers’ Health and Safe- ty,” California Legislature, California Senate Committee on Industrial Relations, Sacramento, 1992. [15] M. S. Wright, “Factors Motivating Proactive Health and Safety Management” HSE Books, Sudbury, 1998. [16] A. Scipioni, F. Arena, M. Villa and G. Saccarola, “Inte- gration of Management Systems,” Environmental Man- agement and Health, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2001, pp. 134-145. doi:10.1108/09566160110389906 [17] J. J. Smallwood, “Client Influence on Contractor Health and Safety in South Africa,” Building Research and In- formation, Vol. 26, No. 3, 1998, pp. 181-189. doi:10.1080/096132198369959 [18] P. N. Fonteyn, D. Olsberg and J. A. Cross, “Small Busi- ness Owners’ Knowledge of Their Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Legislative Responsibilities,” Interna- tional Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, Vol. 3, No. 1-2, 1997, pp. 41-57. [19] D. R. Walters and K. Frick, “Worker Participation and the Management of Occupational Health and Safety: Re- inforcing or Conflicting Strategies?” In: K. Frick, P. L. Jensen, M. Quinlan and T. Wilthagen, Eds., Systematic Occupational Health and Safety Management: Perspec- tives on an International Development, Pergamon, Ox- ford, 2000. [20] D. Walters and F. Lamm, “OHS in Small Organisations: Some Challenges and Ways Forward,” National Research Centre for OHS Regulation, Australian National Univer- sity, Acton, 2003. [21] P. Ring and A. Van de Ven, “Developmental Processes of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 19, No. 1, 1994, pp. 90-118. [22] S. Chen, Y. Duan, J. S. Edwards and B. Lehaney, “To- ward Understanding Inter-Organizational Knowledge Tran- sfer Needs in SMEs: Insight from a UK Investigation,” Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2006, pp. 6-23. doi:10.1108/13673270610670821 [23] J. Rimington, “Managing Risk—Adding Value: How Big Firms Manage Contractual Relations to Reduce Risk—A Study,” Health and Safety Executive, London, 1998. [24] Health and Safety Commission, “Third Report: Organis- ing for Safety, ACSNI Study Group on Human Factors,” HMSO, London, 1993 [25] Commission of the European Communities, “Adapting to Change in Work and Society: A New Community Strat- egy in Health and Safety at Work 2002-2006,” Commis- sion of the European Communities, 2002 [26] Health and Safety Commission, “Health and Safety Sta- tistical Highlights 2002/03,” Health and Safety Executive, Norwich, 2003 [27] P. O’Keeffe, “Understanding Supply Chain Risk Areas, Solutions and Plans: A Five-Part Series,” The Supply Chain Risk Management Series, 2005. http://www.protiviti.com/downloads/PRO/pro-us/publicat ions/SupplyChainRiskAreas.pdf [28] M. Christopher, “Logistics and Supply Chain Manage- ment: Strategies for Reducing Cost and Improving Ser- vice,” 2 Edition, Financial Times/Prentice Hall, London, 1998 [29] European Union, “Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 Concerning the Definition of Micro, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (2003/361/EC),” Official Jour- nal of the European Union, OJ L 124, 2003, p. 36 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU 124 [30] Small Business Administration, Guide to SBA’s Defini- tions of Small Business, 2002. http://www.sba.gov/gopher/Financial-Assistance/Defin/d efi2.txt [31] D. Walters, “Working Safely in Small Enterprises in Europe: Towards a Sustainable System for Worker Par- ticipation and Representation,” European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), Brussels, 2002. [32] A. Ghobadian and D. Gallear, “Total Quality Manage- ment in SMEs,” OMEGA, Vol. 24, No. 1, 1996, pp. 23- 106. doi:10.1016/0305-0483(95)00055-0 [33] H. Iwasaki, “Introduction,” (u.d). http://www.jsbri.or.jp/new-hp-e/outline/intro.html [34] DTI Small Business Service, “DTI News Release: URN 04/92,” 26 August 2004. http://www.sbs.gov.uk/SBS_Gov_files/researchandstats/n ews162.pdf [35] Europa, “Definition of Small and Medium-Sized Enter- prises (SME)—Second External Consultation—to 10.9. 2002,” 2002. http://europa.eu.int/comm/enterprise/library/enterprise-eu rope/news-updates/enterprise-policy/20020708.htm [36] D. Arias-Aranda, B. Minguela-Rata and A. Rodriguez- Duarte, “Innovation and Firm Size: An Empirical Study for Spanish Engineering Consulting Companies,” Euro- pean Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2001, pp. 133-141. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000005671 [37] D. Ariyo, “Small Firms Are the Backbone of the Nigeria Economy,” Africa Economic Analysis, 2000. http://www.afbis.com/analysis/small.htm [38] C. Smallman, “The Reality of ‘Revitalising’ Health and Safety,” Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 32, No. 4, 2001, pp. 391-439. doi:10.1016/S0022-4375(01)00065-2 [39] Eurostat, “Accidents at Work in the EU in 1996,” Statis- tics in Focus, Theme 3-4/2000, 2000. [40] T. Nichols, “Size of Employment Unit and Injury Rates in British Manufacturing: A Secondary Analysis of WIRS 1990 Data,” Industrial Relations Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1995, pp. 45-56. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2338.1995.tb00722.x [41] F. J. Fowler, “Survey Research Methods: Applied Social Research Methods,” Vol. 1, Sage Productions, Watson- ville, 1984. [42] P. Levy and S. Lemeshow, “Sampling of Populations: Methods and Applications,” Wiley, New York, 1991. [43] M. J. Baker, “Sampling,” Marketing Review, Vol. 3, No. 1, 2002, pp. 103-120. doi:10.1362/146934702321477253 [44] L. Glynn, “A Critical Appraisal Tool for Library and Information Research,” Library Hi Tech, Vol. 24, No. 3, 2006, pp. 387-399. doi:10.1108/07378830610692154 [45] M. Fogliani, “Low Response Rates and Their Effects on Survey Results,” 1999. www.sch.abs.gov.au/SCH/A1610103.NSF/0/3ce43babf8 bbf59dca256b7c0001aea4/$FILE/Low%20Response%20 Rates.pdf [46] D. Holt and C. Kockelbergh, “Environmental Supply Chain Management in the UK—an Exploratory Analysis of Current Practices,” Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference of the International Purchasing and Supply Education and Research Association (IPS- ERA), Budapest, 13-16 April 2003. [47] D. J Storey, “Understanding the Small Business Sector,” Routledge, London , 1994. [48] L. Vassie, J. M. Tomas and A. Oliver, “Hea lth and Safety Management in UK and Spanish SMEs: A Comparative Study,” Journal of Safety Research, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2000, pp. 35-43. doi:10.1016/S0022-4375(99)00028-6 [49] I. Dalling, “The Future Is Unified: A Model for Inte- grated Management,” Quality World, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2000, pp. 34-39. [50] Health and Safety Commission, “Health and Safety in Small Firms, Discussion Document DDE,” HMSO, Lon- don, 1995. [51] N. V. Davies and P. Teasdale, “The Costs to the British Economy of Work Accidents and Work-Related Ill Health,” HSE Books, London, 1994. [52] B. Sznaider, “Six Sigma Safety,” Manufacturing Engi- neering, Vol. 125, No. 3, 2000, p. 18. [53] B. Pomfret, “Do Accidents/ Incidents Really Effect Prof- its?” A Key Note Speech and Incorporated in the Intro- duction to “the 5 Star Health & Safety Mana gement Sys- tem” Manual, World Safety Congress, Singapore, Sep- tember 2002. [54] J. Mossink and M. De Greef, “Inventory of Socio-Eco- nomic Costs of Work Accidents,” Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg, 2002. [55] M. Curran, “Environmental, Health, and Safety Activity- Based Cost (ABC) Analysis,” undated. http://www.bettermanagement.com/library/library.aspx?li braryid=3864&pagenumber=1 [56] W. A. Tamarelli, “A Revised Discussion Document in the Report of the OECD Workshop on Small and Medium- Sized Enterprises in Relation to Chemical Accident Chemical Accident Prevention, Preparedness and Re- sponse,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Paris, 1995. [57] D. R. Walters, “Employee Representation and Health and Safety: A Strategy for Improving Health and Safety Per- formance in Small Enterprises?” Employee Relations, Vol. 20, No. 2, 1998, pp. 180-195. doi:10.1108/01425459810211331 [58] Health and Safety Commission, “Levels and Trends in Workplace Injury: Rates of Injury within Small and Large Manufacturing Industry,” Health and Safety Com- mission, London, 2001. [59] Commission of the European Communities, “Adapting to Change in Work and Society: A New Community Strat- egy in Health and Safety at Work 2002-2006,” Commis- sion of the European Communities, 2002. [60] T. C. Lansdown, C. Deighan and C. Brotherton, “Health and Safety in the Small to Medium-Sized Enterprise: Psychosocial Opportunities for Intervention,” Health and Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST 125 Safety Executive, London, 2007. [61] British Chamber of Commerce, “Small Firms Survey: Health and Safety in Small Firms,” British Chamber of Commerce, London, 1995. [62] D. Elliott, D. Patton and C. Lenaghan, “UK Business and Environmental Strategy: A Survey and Analysis of East Midland Firms’ Approaches to Environmental Audit,” Greenleaf Publishing Ltd., Sheffield, 1996, pp. 30-49. [63] R. S. Batenburg and R. Rutten, “Managing Innovation in Regional Supply Networks: A Dutch Case of “Knowl- edge Industry Clustering,” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2003, pp. 263- 270. doi:10.1108/13598540310484654 [64] R. Bennett, P. Robson and W. Bratton, “Government Advice Networks for SMEs: An Assessment of the In- fluence of Local Context on Business Link Use, Impact and Satisfaction,” Applied Economics, Vol. 33, No. 7, 2001, pp. 871-885. [65] Department of the Environment Transport and the Re- gions, “Revitalising Health and Safety: Strategy State- ment,” Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, UK, 2000 [66] Y. Duan, R. Mullins, D. Hamblin, S. Stanek, H. Sroka, V. Machado and J. Araujo, “Addressing ICT Skill Chal- lenges in SMEs: Insights from Three Country Investiga- tions,” Journal of European Industrial Training, Vol. 26, No. 9, 2002, pp. 430-441. doi:10.1108/03090590210451524 [67] Y. L. Doz, “The Evolution of Cooperation in Strategic Alliances: Initial Conditions or Learning Processes?” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, 1996, pp. 55-83. doi:10.1002/smj.4250171006 [68] P. Hines and N. Rich, “Outsourcing Competitive Advan- tage: The Use of Supplier Associations,” International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Manage- ment, Vol. 28, No. 7, 1998, pp. 524-546. doi:10.1108/09600039810247489 [69] S. Lippman, “Environmental Responsibility: Are Corpo- rations Buying It? A Look at Corporate Green Purchas- ing,” Trillium Asset Management Quarterly Newsletter, June 2002. http://207.21.200.202/pages/news/news_detail.asp?Articl eID=163&Status=Archive [70] J. C. Anderson and J. A. Narus, “A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 54, No. 1, 1990, pp. 42-58. [71] M. Aquilon, “Cultural Dimensions in Logistics Manage- ment: A Case Study from the European Automotive In- dustry,” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1997, pp. 76-87. doi:10.1108/13598549710166122 [72] M. Cook and R. Tyndall, “Lessons from the Leaders,” Supply Chain Management Review, November/Decem- ber 2001, p. 23. [73] S. Hutchison, “Leadership and the Value of Strategic Communication,” Issue 06/03, 2003. http://www.ceoforum.com.au/200306_remuneration.cfm [74] R. M. Morgan and S. D. Hunt, “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 58, No. 3, 1994, pp. 20-38. doi:10.2307/1252308 [75] N. Gunningham and D. Sinclair, “Environmental Part- nerships; Combining Sustainability and Commercial Ad- vantage in the Agriculture Sector,” 02/004 ACL-1A, Ru- ral Industries Research and Development Corporation, Australia, 2002. [76] T. Redman, E. Snape and A. Wilkinson, “Is Quality Management Working in the UK?” Journal of General Management, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1995, pp. 44-59. [77] R. Horvath, “Collaboration: The Key to Value Chain Cre- ation in Supply Chain Management,” Supply Chain Ma- nagement: An International Journal, Vol. 8, No. 3, 2001, pp. 224-240.  I. A. DIUGWU 126 APPENDIX 1 Section A: About the company A.1. What is the name of your business? __________________ (Optional) A.2. How many employees does your business have? (if 250 and above, please also complete sections G and H) No of Employees Full Time 1 - 9 10 - 49 50 - 249 250 and above A.3. To which of these industries does your business belong? Agriculture Extractive & utility supply Construction Manufacturing Service Others Section B: Health and safety management awareness B.1. Do you think that poor health and safety record could impact on your Yes No Business Operations Business Image Please describe B.2. Do you have an appointed health and safety representative in your company?Yes No B.3. What percentage of the total working week of the person in (B.2.) above is spent on Health & Safety management duties? 0% - 9% 50% - 89% 10% - 49% 90% - 100% B.4. Who else is involved in your company’s health and safety management? Senior Management External Consultants Heal th and Safety Committee Trade Unions Industrial Network Others____________________ B.5. How many lost time accidents have you had in the past 12 months? ______ Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU127 B.6. Who enforces Health and Safety in your business sector? Health and Safety Executiv e (HSE) Local Authority’s Environmental Health Department Don’t know B.7. Have you ever been visited by a health and safety enforcement officer? No If “Yes”, what was the purpose of the visit? Routine inspection Accident/incident investigation Complaint investigation Advice B.8. What was the outcome of the visit? Improvement notice Prohibition notice Prosecution Formal caution Verbal/written advice Other B.9. Which of the following Health and Safety legislation are you aware of that affects your business? (Please tick applicable box or boxes) The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations Workplace (Health, Safety and Welfare) Regulations Noise at Work Regulations Health and Safety (Display Screen Equipment) Regulations Electricity at Work Regulations Personal Protective Equipment at Work Regulations Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regula- tions 2002 (COSHH) Provision and Use of Work Equipment Regulati ons Chemicals (Hazard Informatio n and Packaging for Supply) Regulations Manual Handling Operations R e gu l a ti o n s Construction (Design and Management) Regulations Health and Safety (First Aid) Regulations Gas Safety (Installation and Use) Regulations The Health and Safety Information for Em pl oyees Regulations Control of Majo r Accident Hazards Regulations Employers’ Liab ility (Compulsory Insurance) Act Dangerous Substances and Explosive Atmosphere s Regulations B.10. Which of the following do you have in place for managing health and safety in your company? (Please tick all applicable or boxes) Written policy statement Safety audit system Risk assessment Conducted by your company’s personnel Conducted by a Consultant Training programmes Health surveillance Accident/Incident reporting procedures Written safe wor king procedures Permit to work Incentive schemes None of these Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST  I. A. DIUGWU Copyright © 2011 SciRes. OJSST 128 B.11. How do you keep informed on Health and Safety issues and regulations? Trade Unions Local Authority Health and Safety Executive/Web site Industrial ne two rk/safety groups Health and safety journals Head office Section C: General heal th a nd s af ety policy Yes No C.1. Do you have a formal health and safety policy that describes roles and responsi bilities? C.2. Do you have a policy that requires written accident/incident reports (injuries, property damages, near misses, fires, explosions, etc.)? C.3. Do you conduct accident/incident investigations? C.4. Do you document, invest i gate, and discuss near miss accidents?

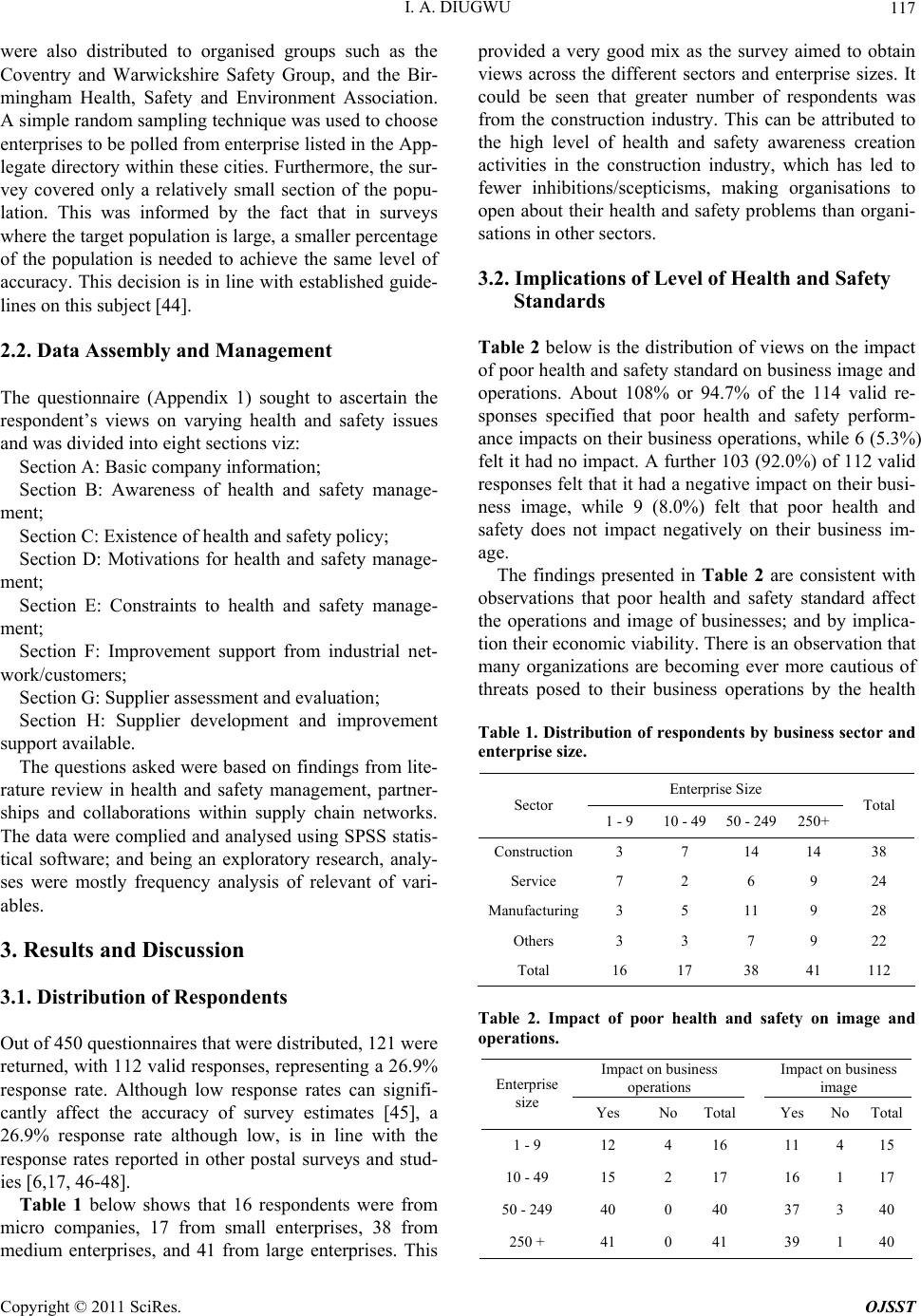

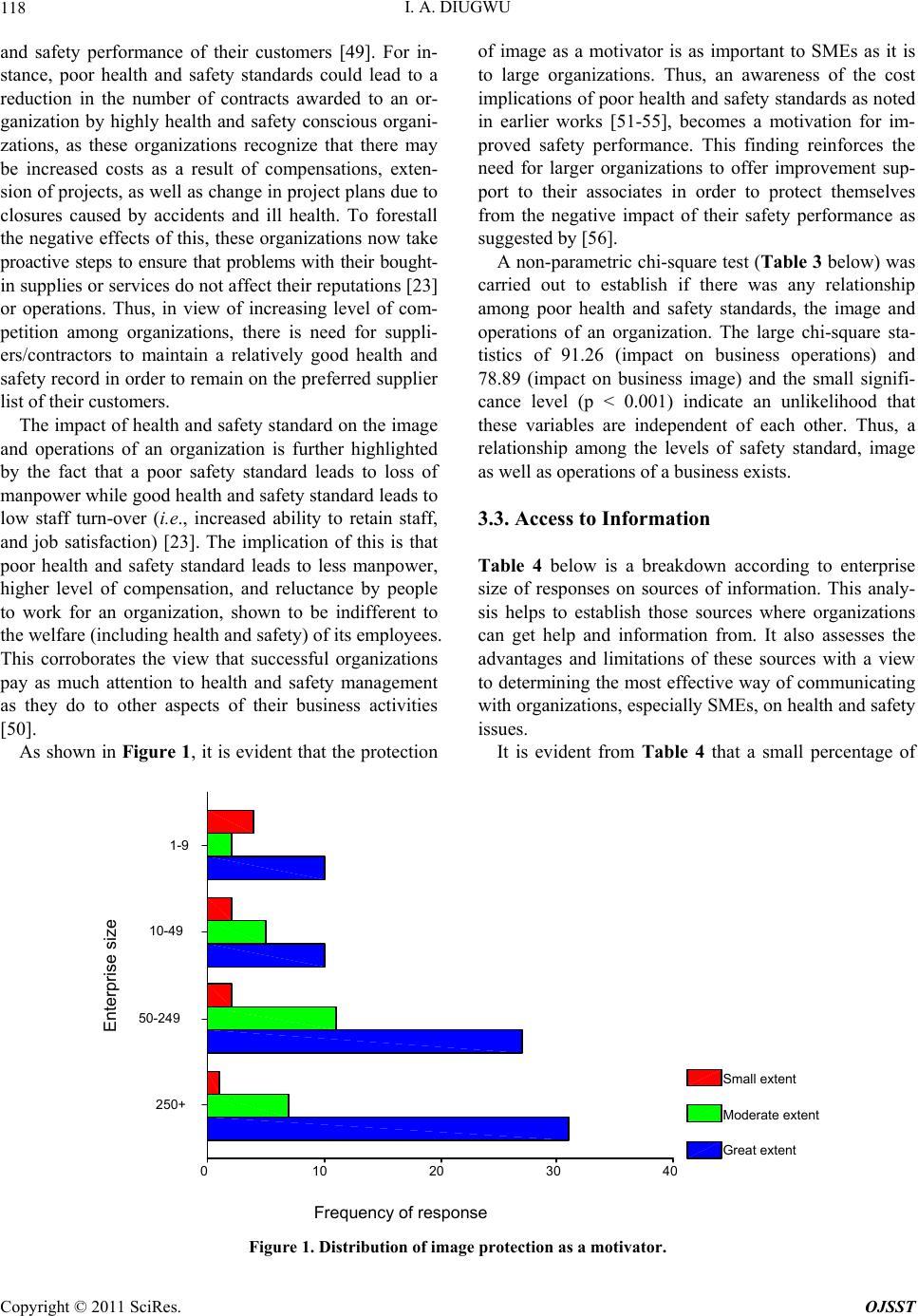

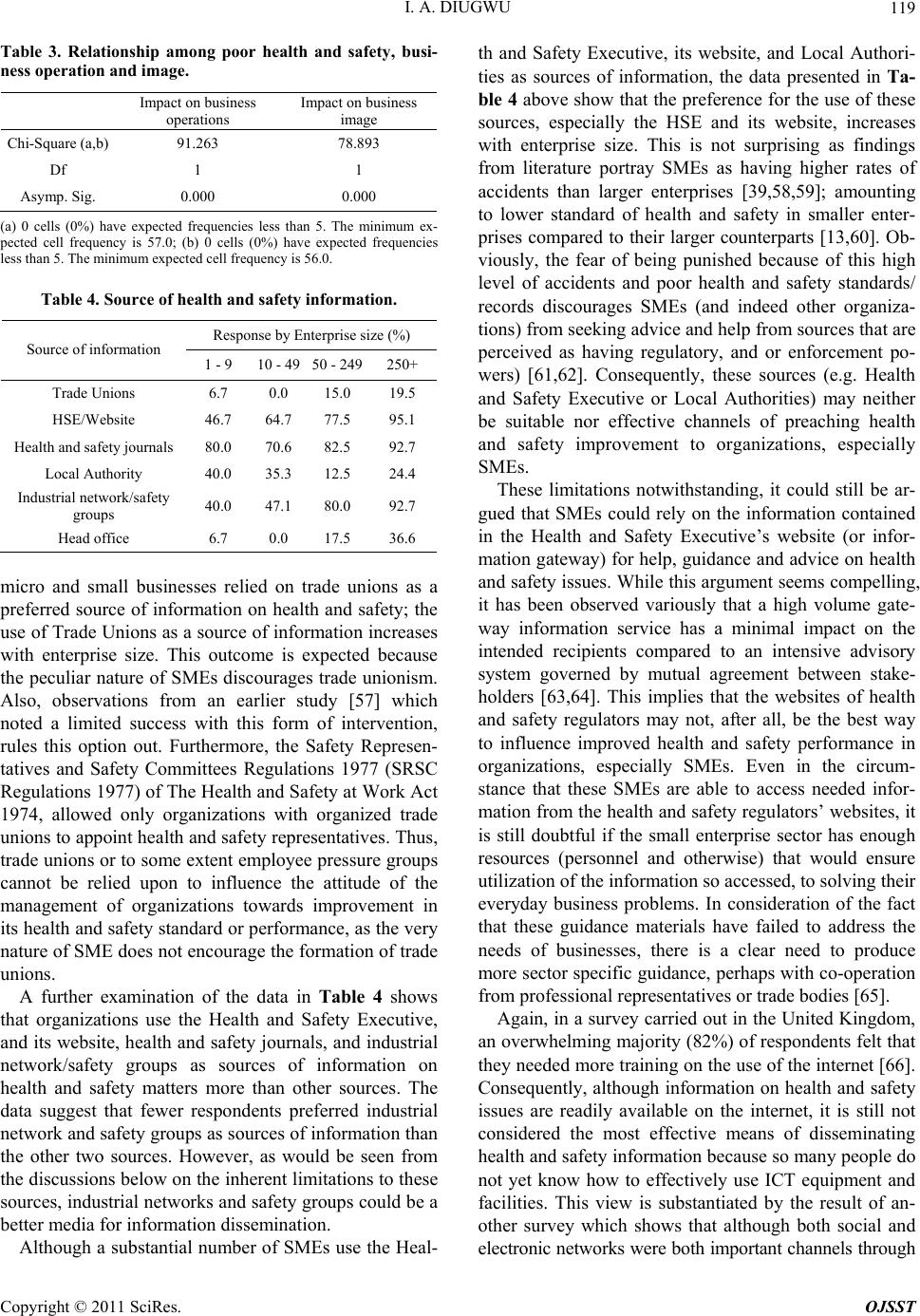

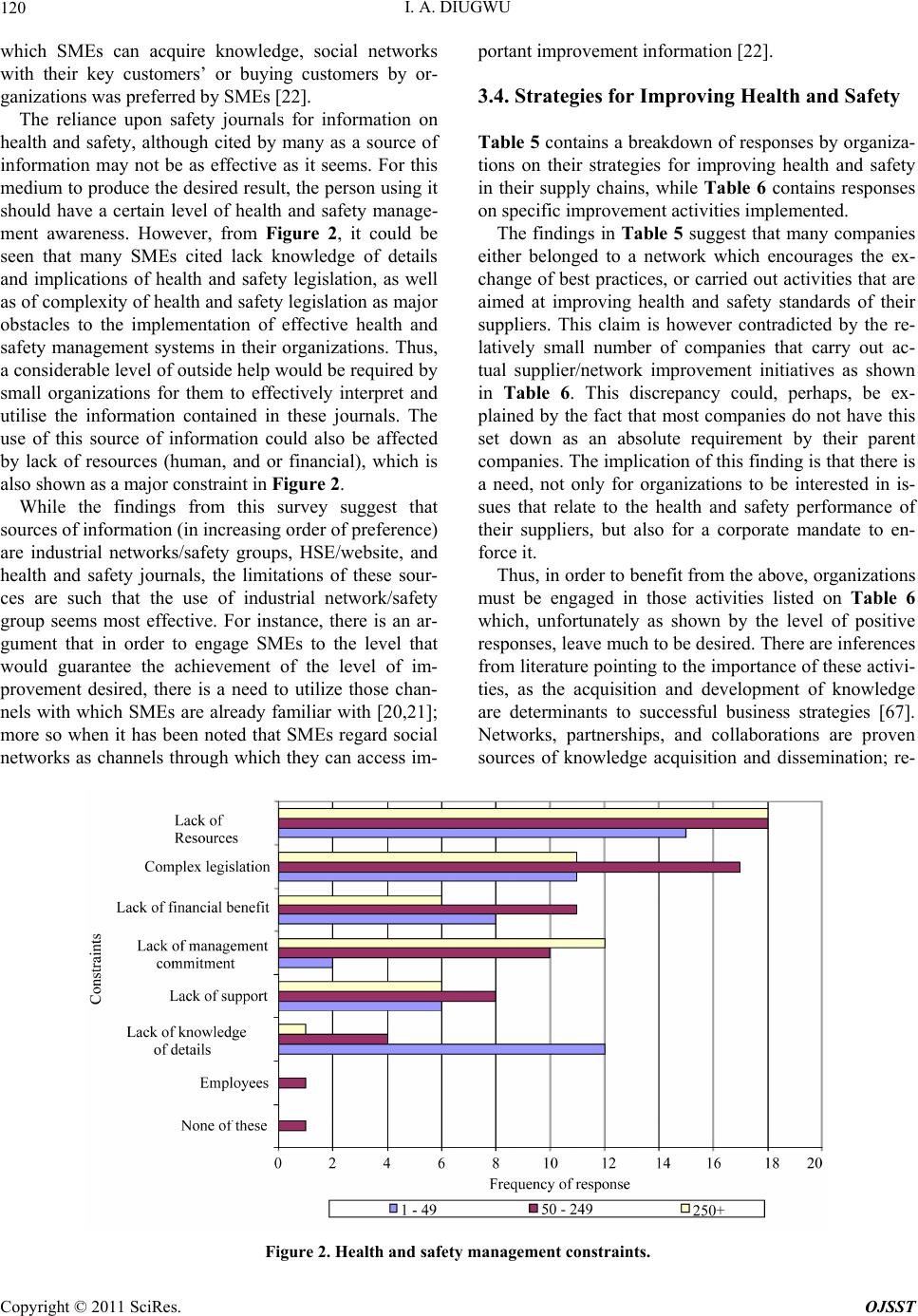

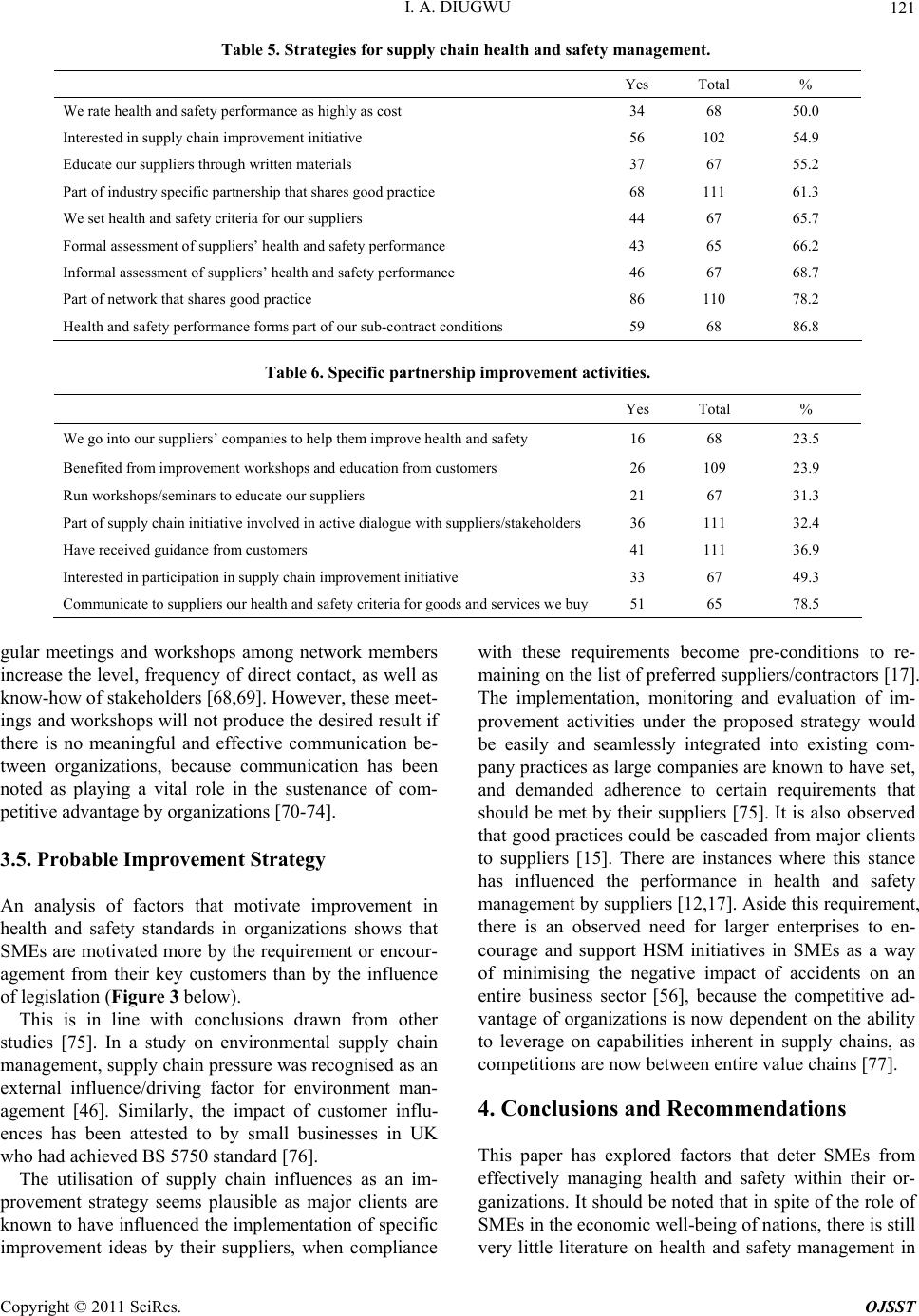

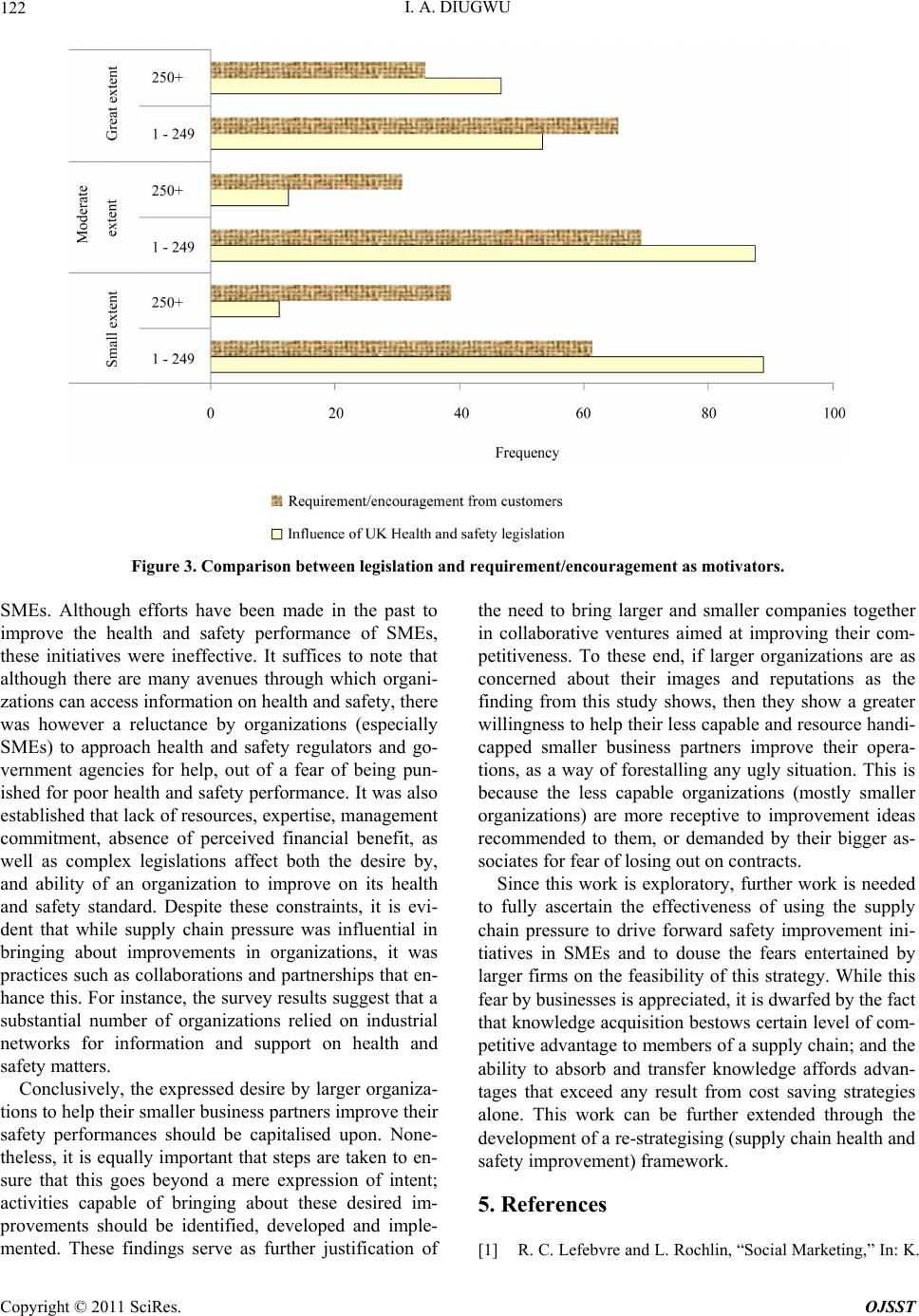

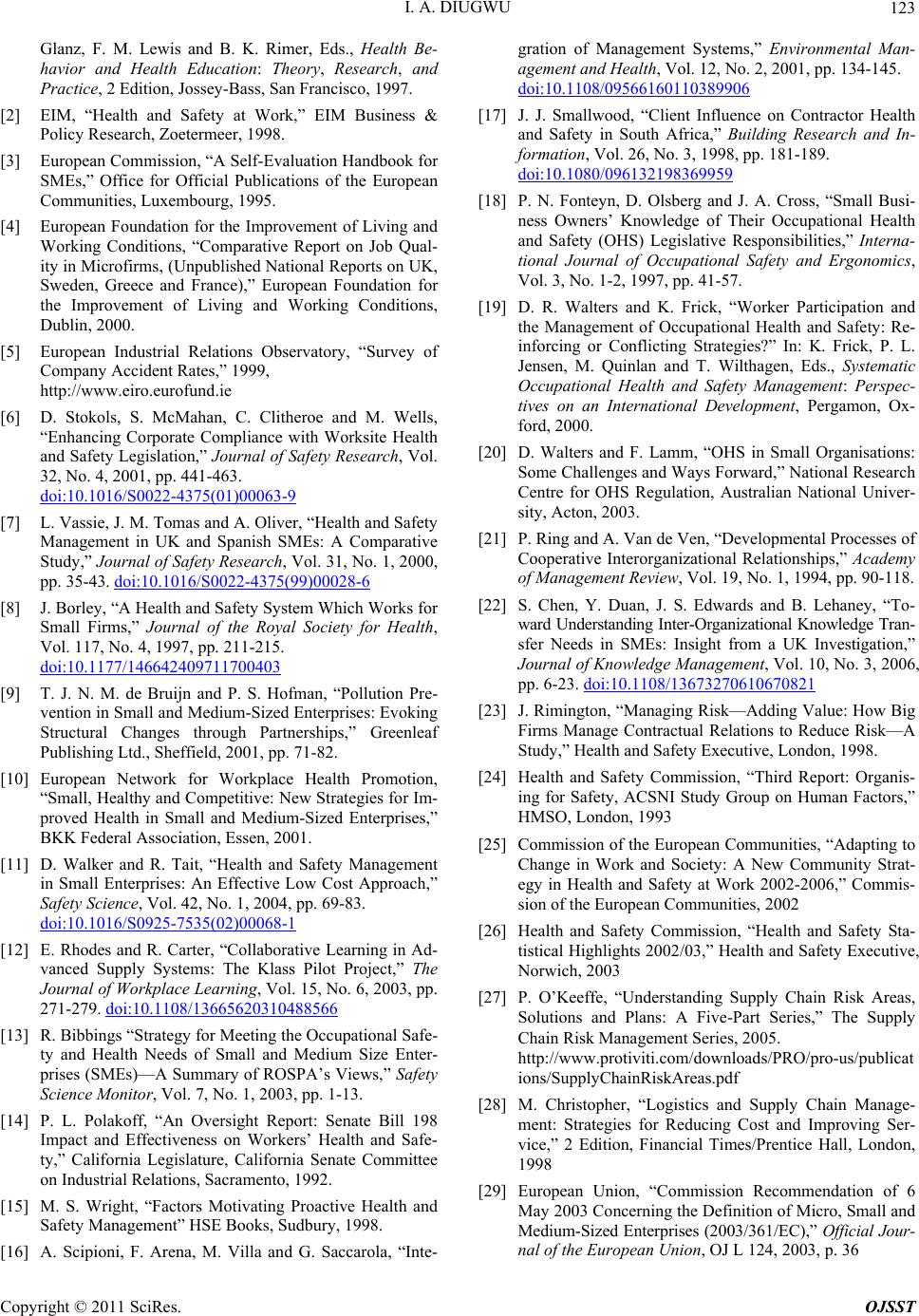

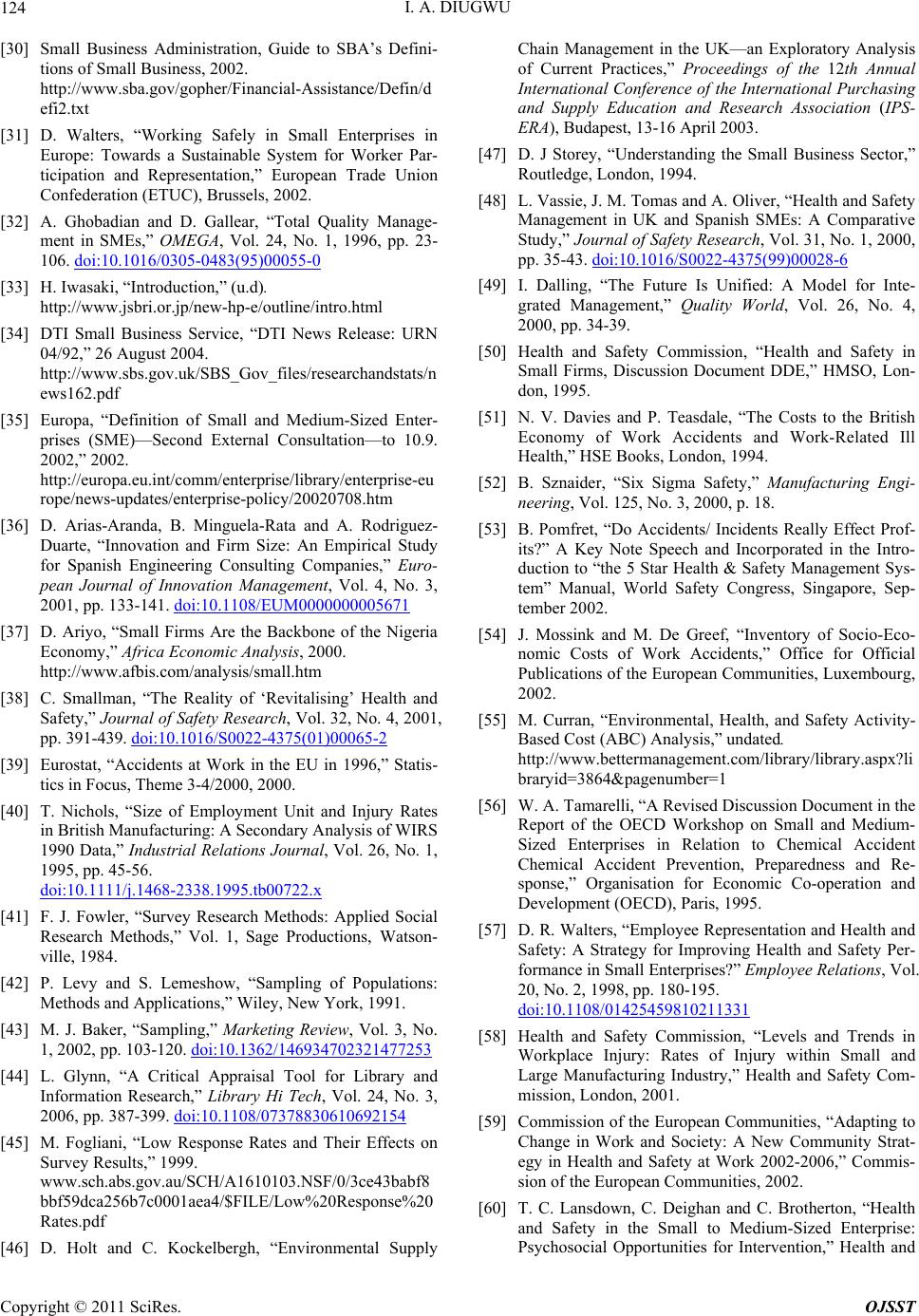

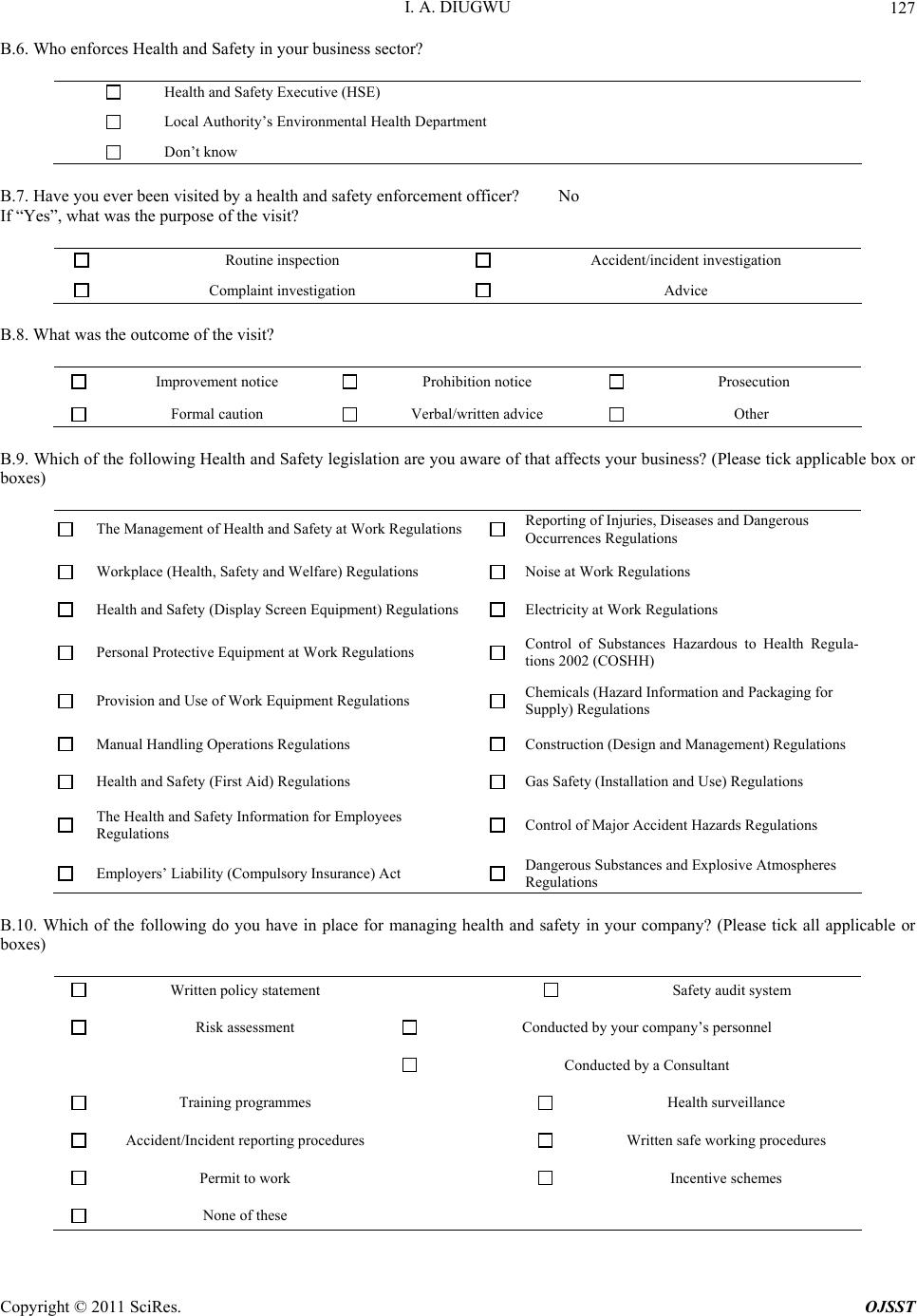

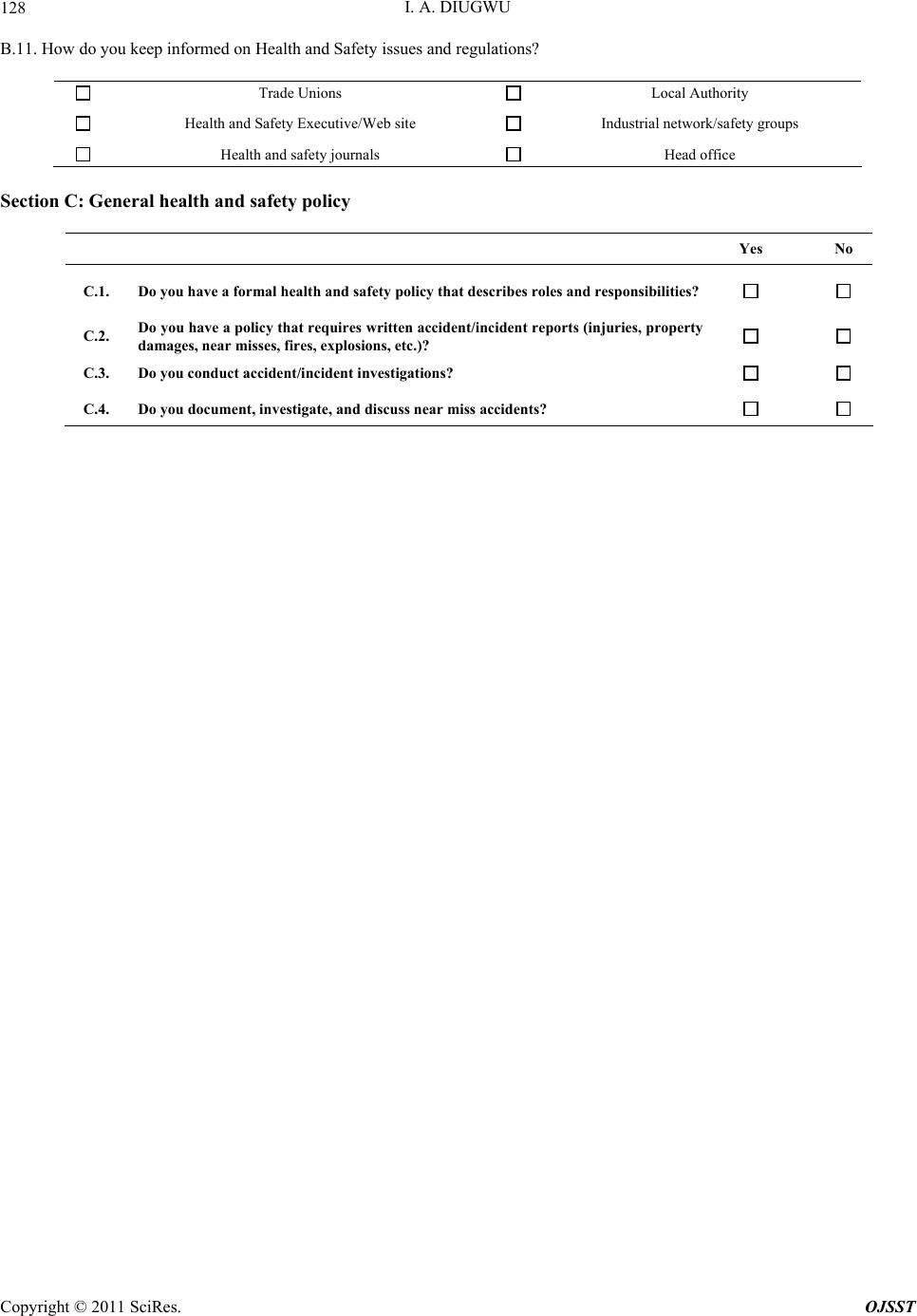

|