Advances in Applied Sociology 2011. Vol.1, No.1, 56-63 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. DOI:10.4236/aasoci.2011.11005 Factors Influencing Work Efficiency in China Wei Wei, Robert J. Taormina* Psychology Department, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Macau, Macau (SAR), China. Email: *Taormina@umac.mo Received November 14th, 2011; revised December 18th, 2011; accepted December 29th, 2011. The preferred methods of conflict handling are largely sociologically prescribed in China, but those methods could reduce efficiency in the workplace. This study examined factors that could influence the efficiency of working people since efficiency is important to the successful operation of organizations. Some relatively unex- plored personality variables, i.e., Creativity and Resilience, Esteem from Others, Attrib ution for Success (to Self), and Attribution for Success (to Others), and some more usual variables, i.e., Conscientiousness, Self-Conf id en ce , a n d Organization al Socialization (Training, Understanding, Coworker Support, Future Prospects), were tested for their expected positive relationships to three dependent variables, i.e., Work Efficiency, Conflict Handling-Avoidance, and Conflict Handling-Compromising. Questionnaire data from 192 Chinese employees in Mainland China were analyzed to assess these relationships. Correlation results indicated that all variables (except Future Prospects and Attribution to Others) were positively related to Work Efficiency, and most were positively related to both Conflict Handling-Avoidance, and Conflict Handling-Compromising. Results for the relationships of the per- sonality and social variables to conflict handli ng and work effi cie n c y are discussed in terms of Chinese culture. Keywords: Chinese Culture, Conflict Han dli ng, Compromising, Work Efficiency Factors Influencing Work Efficiency in China Chinese society is known for its dedication to Confucian values, which stress harmony in social relationships as a prin- cipal societal objective (Yang, 1995), such that, for example, avoiding conflict in the near-term could maintain harmony over the long-term. At the same time, however, as Lu, Kao, Siu, and Lu (2010) noted regarding conflicts in the workplace, using an avoidance coping strategy might not always be optimal, i.e., “withdrawing from the stressful reality and conceding to fate may give one momentary peace of mind and protect social har- mony, but such passive adaptatio n does not eradicate the stress- ors” (p. 301). No netheless , Kirkbr ide, Tang, and Westwoo d (1 991), who used paired statements reflecting five conflict handling styles (e.g., competing versus collaborating) found the most chosen options for the Chinese to be compromising and avoid- ing. While this societal preference for avoiding conflict to main- tain harmony is a well-known predilection for the Chinese, what has not been sufficiently examined is whether there are person- ality factors that could influence one’s preferred conflict-hand- ling style, and the extent to which each of the preferred conflict- handling styles is related to the employees’ work efficiency. Employee efficiency is an important concept for human re- source management as well as for overall organization per- formance. Organizations need to be efficient in order to com- pete and survive in the modern economic environment. The rea- son for this can be readily understood from the definition of the word “efficiency” which means “to be productive without waste” (e.g., of time or energy), namely, “effective operation as meas- ured by a comparison of production with cost, as in energy, time, and money” (Merriam-Webster, nd). This implies that im- proving employees’ efficiency at work should be very impor- tant to the organization’s economic performance. According to Taormina and Gao (2009), since efficiency is considered to be a means to achieve organizational goals, high efficiency is de- sired by management for their organizations to attain high ef- fectiveness. Given the concern about avoiding conflict in Chinese society, this research also considers personality factors that might be re- lated to how employees handle conflicts at work, since conflict in the workplace could create interpersonal problems, e.g., for work teams, that could interfere with organization efficiency (Liu, Fu, & Liu, 2009) Since work efficiency, as a specific measure, was a newly discovered variable (Taormina & Gao, 2009), there is no exist- ing theory about it. The closest concept is work performance, which is a very general term that could include a number of different components, while work efficiency is a more specific concept. There have been many studies on work performance, and some indicate that good work performance contributes to desired organization outcomes (Maxham, Netemeyer, & Lich- tenstein, 2008). On the other hand, a few papers used a concept named work efficiency, but they examined this variable in terms of specific tasks (e.g., Paul, 1967), without examining personality factors, such as the unique attribute s of creativity and resilience, that might contribute to employee work efficiency. Thus, this research also examines personality factors that may be related to work efficiency. Research Objectives The main objectives of this research were to identify person- ality and organizational factor s that could be related to employee work efficiency, as well as to ways that employees handle con- flicts at work. In particular, some unique and less studied per- sonality factors, i.e., Creativity, Resilience, Esteem received from Others, Attribution for Success (t o Self), and Attribution for Suc- cess (to Others), as well as some more standard variabl e s, namely, Conscientiousness, Self-Confidence, and aspects of organiza- tional socialization (Training, Understanding, Coworker Sup- port, Future Prospects), were examined for their possible influ- ence on the dependent measures. Also missing from the litera- ture are studies on the above variables using data from Main- land China. Thus , this stu dy uses data from emp lo ye es in two ci ties in southwest and northeast China, i.e., Kunming and Changchun,  W. WEI ET AL. 57 respectively. To facilitate understanding of the expected relationships among the variables for this study, the dependent variables are described first, followed by the independent variables with their hypothe- sized relationships to the dependent variables. Dependent Variables Work Efficiency. Taylor (1911) first put forward the concepts of efficiency when he introduced the scientific study of work methods in order to improve worker efficiency. Taylor pio- neered a method, now known as the “time-and-motion” study, for determining the best way to reduce time and effort (improve efficiency). Taormina and Gao (2009) indicated that efficiency refers to obtaining the most output from the least amount of input. Accordingly, managers should be concerned with em- ployee work efficiency since high efficiency should lead to lower costs but better products, which would benefit the or- ganization. Consequently, since the specific variable of Work Efficiency has not been sufficiently examined, and the factors contributing to it are not clear, it is necessary to further investi- gate work efficiency. Conflict Handling. Barki and Hartwick (2004) defined con- flict in the work setting as “a dynamic process that occurs be- tween interdependent parties as they experience negative emo- tional reactions to perceived disagreements and interference wi th the attainment of their goals” (p. 216). Conflicts occur every- where, including in the workplace; and since conflicts disrupt personal relationships, they could disrupt work performance, which requires finding ways to handle them. Blake and Mouton (1964) suggested some methods that people use in conflict si- tuations, and Rahim (1983) developed several measures for hand- ling interpersonal conflict, including avoiding, compromising, and dominating. As this study was conducted in China, where harmonious relationships are a cultural imperative (Yang, 1995), the dominating approach to conflict handling should be rare and, for this reason, was not examined in this study. Thus, only the two styles of Conflict Handling-Avoidance and Conflict Han- dling-Compromise were investigated. Conflict Handling-Avoidance. Rahim, Magner, and Shapiro (2000) explained that, when there is conflict, the use of the avoid- ing style refers to ignoring, taking no action, or withdrawing from the situation; and stated that this style tends to not satisfy the concerns of either party in the conflict. Conflict Handling-Compromising. Rahim et al. (2000) stated that, for this style, both parties must give up something in order to reach a mutually satisfying decision. Furthermore, a person using the compromising style would give up more than a domi- nating person, but would address the concern more directly than an avoiding person, thereby splitting the differenc e with the other party in order to reach a middle ground. Independent Var iables Creativity. There has been a growing consensus among crea- tivity researchers regarding the appropriateness of defining creativity in terms of an outcome, such as an idea or product (Amabile, 1988). In particular, Amabile’s (1988) definition of creativity is the “production of novel and useful ideas” (126). This makes creativity especially relevant to human resource management, and, consistent with this operationalization, that definition of creativity is adopted for this study. Although not extensively studied in the human resource lit- erature, some research has been conducted on creativity in the workplace. For example, Rasulzada and Dackert (2009) found that organizational climate and work resources were significantly related to perceived creativity and innovation in organizations. In addition, according to Oldham and Cummings (1996) em- ployees produced the most creative work when they had crea- tivity relevant personal characteristics, e.g., when they were in- sightful, intelligent, original, inventive, resourceful, and reflec- tive. These characteristics would likely allow such individuals to think of ways to perform their work more easily and effect- tively. Therefore, H(1): The more Creativity employees have, the more Work Efficiency they will have. With regard to Conflict Handling (Avoidance and Compro- mise), creative individuals would probably find conflict to be disruptive to their work and , thus , when em plo yees ar e sub ject ed to some problems with work and personal relationships in an or- ganization, they are inventive enough to find new ways to avoid them. Alternately, if the conflict is unavoidable, they might also be creative enough to think of ways to compromise, but without losing too much in the deal. Therefore, H(2): The more Creativity employees have, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoidance they will use; and (b) the more Conflict Handling-Compromise they will use. Resilience. Although the concept of resilience has been de- fined in different ways, the dictionary definition of resilience, i.e., “The act of rebounding or springing back” (Oxford English Dictionary, nd) is used here. Likewise, research on resilience has taken two approaches, namely, one that views resilience as a set of traits (Jacelon, 1997), and the other, from the counseling literature, sees it as a process of receiving support from other people. Here, resilience is viewed as a personal characteristic. Also, one theory of resilience that fits either approach is that by Antonovsky (1987), who sees resilience as a characteristic of people in good health, which allows them to resist threats to their well-being and to spring back in the face of adversity. With regard to Work Efficiency, the personal-characteristics view would argue that resilient people would not give up when they are faced with difficulties at work, and, instead, would try harder to complete their tasks, which would result in better per- formance. Thus, H(3): The more Resilience employees have, the more Work Efficiency they will have. Regarding Conflict Handling (Avoidance and Compromise), Resilience should also be relevant. The research from counsel- ing, which, at the same time fits the Antonovsky (1987) model, describes resilient individuals as having experienced and sur- vived stressful situations. There is research support for this model, e.g., that individuals who successfully survived stressful situa- tions have personal characteristics that allow them to rebound from the stress to live successful lives (Parker, Cowen, Work, & Wyman, 1990). Thus, resilient people may be more sensitive to stress, and, since conflict is stressful, they would want to avoid it, if possible, or, if it is unavoidable, to compromise in order to reduce its duration. Hence, H(4): The more Resilience employees have, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoidance they will use; and (b) the more Conflict Handling-Compromise they will use. Conscientiousness. Conscientiousness is one of the Big Five personality dimensions, which characterizes people as being care- ful, reliable, hardworking, and organized (Costa & McCrae, 1985). As such, it is likely to be an attribute that managers would want their employees to possess, and it has been studied extensively in regard to work performance. In particular, Bar- rick and Mount (1991) conducted a meta-analysis of the Big Five personality dimensions and argued that Conscientiousness  W. WEI ET AL. 58 should be related to job performance because it relates to a person being careful and hardworking, which are characteristics that help one to accomplish their work assignments. They found Conscientiousness to predict all job performance criteria, and concluded that “Individuals who exhibit traits associated with a strong sense of purpose, obligation, and persistence gener- ally perform better than those who do not” (p. 18). Thus, this variable is expected to reveal similar results with Work Effi- ciency. H(5): The more Conscientious employees are, the more Work Efficiency they wi ll have. For Conflict Management (Avoiding and Compromising) and Conscientiousness, relatively little research has been performed, and is thus inconclusive. Antonioni (1998), for example, found no significant correlations between Conscientiousness and the two types of Conflict Handling. When the data were split for student and managers in regression analyses, Conscientiousness could not predict Avoiding for either group, and could not pre- dict Compromising for students, but was a negative predictor for managers, i.e., managers who were less conscientious were more likely to c ompromise . That study was conducted in the West, but since this study is for Chinese, a different logical argument is used, i.e., if Con- scientiousness is characterized by being careful, then conscien- tious employees may prefer to avoid conflict; at the sa me time, however, since conscientious people are also planful, reliable, and responsible, they might also be inclined to compromise in negotiations in order to reach more agreeable solutions to a con- flict. Hence, H(6): The more Conscientiousness employees have, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoidance they will use; and (b) the more Conflict Handling-Compromise they will use. Self-Confidence. Based on Kolb (1999), self-confidence is defined as the degree of perc ei ved proba bility of success a t a ta sk. Some research found that self-confidence was related to past experience and the feedback from past experience (McCarty, 1986). This research, however, views self-confidence as a pre- cursor of Work Efficiency, with the idea that people who are confident of their abilities would be more likely to perform well. In other words, people with high self-confidence would likely think that they are more able to solve problems at work, and thus work more efficiently. This idea has been supported in a study by Hanton and Connaughton (2002), who found that higher levels of self-confidence were associated with higher performance. Thus, H(7): The more Self-Confidence people have, the more Work Efficiency they wi ll have. For Conflict Handling, people with high Self-Confidence might believe they can readily solve a conflict and prefer not to argue about it, and thus might avoid conflicts. For compromise, people high on Self-Confidence might be open to using com- promise because they would not worry about giving up some- thing in the negotiations since they feel sure that they could rely on themselves if the compromised solution does not work. There- fore, H(8): The more Self-Confidence people have, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoiding, and (b) the more Con- flict Handling-Compromising they will use. Esteem from Others. Esteem is generally defined as the worth or value that is placed on something or someone (Mer- riam-Webster, nd), and, in psychology, is the positive regard or re sp ect t hat p eop le h ave t oward themselves or toward other peo- ple. Specifically, in Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs, esteem, which is a higher-order need, is of two types, namely, self- esteem and esteem received from others. Of the two, there is an abundant literature on self-esteem in the workplace (see Pierce & Gardner, 2004), but Esteem from Others is a concern of this research because the respect that a person receives from co- workers could affect one’s work performance and how that person deals with conflicts at work. In terms of Work Efficiency, the concept of “face” could play a role. Face generally refers to a person’s respectability, or how one is regarded in society. People “have face” when other people re spect them, but “lose face” when they are publicly embarrassed, and, in China, social reputation is very important (Hwa ng, 1987). Thus, if a person already is respected by his or her coworkers, he or she might desire to be more proficient and do excellent work in order to maintain that respect. Therefore, H(9): The more Esteem from Others employees receive, the more Work Efficiency they will have. Regarding Conflict Handling, face could also play a role. That is, when conflicts occur, a person who is respected by others might prefer to avoid becoming involved in them as a way of precluding the possibility of losing respect because of disagree- ments that could result from conflicting views or opinions. In cases where the person who is highly respected by others can not avoid a conflict, once again, in order to maintain the respect they are receiving, the person might be more willing to com- promise somewhat so that he or she is not seen as being too in- flexible, which could result in losing respect. Thus, H(10): The more Esteem from Others employees receive, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoiding, and (b) the more Conflict Handling-Compromising they will use. Attribution for Success (to Self and Others). Base on Hei- der’s (1958) causal attribution theory, whereby people make causal inferences about why events occur, e.g., why someone succeeds at a task, due to either one’s own efforts (internal) or to environmental (external) causes. In this study, Attribution for Success refers to successes in one’s own life and is examined in two dimensions, namely, attribution to oneself for success (i.e., the individual’s own efforts led to the success) and attribution to others for success (i.e., helpful efforts of other people led to one’s success), which is a recent application of attribution the- ory (Taormina & Gao, 2010). People who attribute their suc- cesses to their own efforts would likely do so because of their past achievements, e.g., in their jobs, and therefore should per- form well at work. Hence, in terms of the dependent measures in this study, people who are high on this factor should perform well and have high Work Efficiency. Regarding attribution to others, Work Efficiency focuses on one’s individual perform- ance, so other people might not affect the estimate of one’s own effectiveness. Therefore, a relationship is expected only be- tween Attribution to Self and Work Efficiency. H(11): The more Attribution for Success (to Self) em- ployees engage in, the more Work Efficiency they will have. With regard to attributions for success and Conflict Handling, people with a high Attribution to Self (i.e., believe their suc- cesses are due to their own efforts) would likely have a high sense of personal achievement. Thus, they may be reluctant to involve themselves in conflicts with others and avoid conflicts in preference of searching for solutions that are more suited to their own way of doing things. Also, in the case of conflicts they can not avoid, they might tend to use compromise because they believe that even if they “give up” something, they could rely on themselves in case the compromise should fail. H(12): The more Attribution for Success (to Self) em-  W. WEI ET AL. 59 ployees engage in, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoiding, and (b) the more Conflict Handling-Compromising they use. For people with a high Attribution to Others (i.e., believe their successes are due to the help received from other people), they would likely avoid conflicts in order to maintain good relationships with others because they might need their help again in future. And when conflicts happen that they can not avoid, they would be more likely to compromise, again for the purpose of keeping good personal relationship in anticipation of obtaining help from others in the future. Therefore, H(13): The more Attribution for Success (to Others) em- ployees engage in, (a) the more Conflict Handling-Avoiding, and (b) the more Conflict Handling-Compromising they will use. Organizational Socialization. Organizational Socialization has been defined as “the process by which a person secures relevant job skills, acquires a functional level of organizational under- standing, attains supportive social interactions with co-workers, and generally accepts the established ways of a particular or- ganization” (Taormina, 1997, p. 29). It has four domains: Training, Understanding, Coworker Support and Future Pros- pects. Training refers to the job-related skills organizations provide to employees; Understanding refers to the employees’ cognitive comprehension of the way the organization works and the ability to apply that knowledge; Coworker Support refers to both instrumental and emotional sustenance that employees receive from other workers; and Future Prospects refers to em- ployees’ expectation about promotion and rewards that the or- ganization makes available. Previous research showed that these four domains were sig- nificantly and positively related to Work Efficiency (Taormina & Gao, 2009). With regard to Training, Bernardin and Beatty (1984) pointed out that training and development are important parts of the HRM process. Their model of the HRM system demonstrates that through selection, training, development, place- ment, and motivation, an organization can achieve effectiveness and efficiency among its human resources. Therefore, H(14): The more highly employees evaluate the Training offered by their organization, the more Work Efficiency they will have. For Understanding, Reio and Wiswell (2000) studied infor- mation seeking as part of workplace learning, which represents increased understanding, and found that it played an important role in job performance. In order to promote work efficiency, an employee needs to learn well and understand how their or- ganizations function, which should help them become more ef- fective and efficient in their work. Therefor e, H(15): The more highly employees evaluate their own Understanding, the more Work Efficiency they will have. For Coworker Support, positive relationships among coworkers include assistance with tasks (when needed) and moral support, all of which are expected to improve employee work efficiency. Previous research has provided evidence for this idea, i.e., that support among coworkers improves work performance (Lee, 1986) and performance proficiency (Taormina, 2004), and in- creases productivity (Wolf, 1989); all markers of Work Effi- ciency. And more recently Coworker Support was also found to be directly related to Work Efficiency (Taormina & Gao, 2009). Thus, those studies suggest a positive relationship between Co- worker Support and Work Efficiency. Therefore, H(16): The more highly employees evaluate their Coworker Support, the more Work Efficiency they will have. Future Prospects, according to Taormina (1997), are rewards, benefits, opportunities, and promotions offered by a company that represent types of reinforcement management provides to its employees for doing good work, which should improve the employees work efficiency . Alternately, if good job perfor mance is not rewarded, employee motivation is likely to decline. Em- pirical support for the positive relationship between Future Pros- pects and Work Efficie ncy has been provided by Taormina and Gao (2009). Therefore, H(17): The more highly employees evaluate their Future Prospects in their companies, the more Work Efficiency they will have. Method Respondents The respondents were 192 (62 female, 129 male, 1 no response) Chinese adults aged between 18 and 58 years (M = 36.83, SD = 8.32) working in factories and private companies in Kunming and Changchun China. Highe st education levels were: 3 primary school; 21 high school; 53 junior college; 94 bachelor; 18 mas- ter or above; 3 no response. For Marital status, 48 were single, 140 married, and 4 other (separated, divorced, widowed, or no response). The average number of children reported was 0.68 (SD = 0.49). Regarding employment, all 192 were employed full-time. Monthly income (in Chinese RMB) was as follows: 3 at <1000; 86 at 1000-2999; 64 at 3000 - 4999; 19 at 5000 - 6999; 11 at 7000 - 8999; 4 at 9000 or more, and 5 gave no re- sponse. Measures In addition to the demographics, and the 3 main variables (Work Efficiency, Conflict Handling-Avoidance, and Conflict Handling-Compromise), there were 11 independent variables. Unless otherwise noted, all measures asked respondents how well the items described them, using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Demographics. Age and number of children were recorded as given. Other codings were: Gender (0 = female, 1 = male); Education (0 = none, 1 = primary, 2 = high school, 3 = junior college; 4 = bachelor, 5 = master or above); Marital status (1 = single, 2 = married, 3 = other); Employment (0 = none, 1 = part time, 2 = full-time); Monthly income, in Chinese RMB (1 = 1000, 2 = 1000 - 2999, 3 = 3000 - 4999, 4 = 5000 - 6999, 5 = 7000 - 8999, 6 = 9000 or more). Work Efficiency. Work Efficiency was measured with an 8-item scale. F our i tems were derived from Gao and Taormina’s (2002) 4-item Work Efficiency scale, which identified some generally accepted performance appraisal criteria across indus- tries in China, e.g., “Able to meet deadlines.” To increase the strength of the scale, four more items were added that came from brainstorming by several professionals in the management area, i.e., “Prioritize my tasks effectively”, “Complete tasks quickly”, “Make efficient use of my time at work”, and “Use the most effective methods for doing the work”. Respondents were asked to indicate how often these criteria describe their per- formance, and answered on a 5-point frequency scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). Conflict Handling Styles. The two Conflict Handling Styles of Avoiding and Compromising were each measured by 5-item scales. All items were from Rahim’s (1983) scales for handling interpersonal conflict. The five Avoiding items were from Ra- him’s (1983) 7-item Avoiding subscale, e.g., “I avoid confronting others”. And the five Compromising items were from his com-  W. WEI ET AL. 60 promising subscale, e.g., “I negotiate with others so that a com- promise can be reached”. Respondents were asked how often they performed the actions described by the statements when they have conflicts with other people, and their answers were recorded on a 5-item scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Esteem. Esteem Needs were measured using a newly created 12-item scale. All the items were developed from Maslow’s (1943, 1971, 1987) theory of need satisfaction. According to Maslow, Esteem Needs are of two types, Esteem for Self, and Esteem from Others. Only Esteem from Others was assessed with six statements on satisfaction with the respect and recogni- tion the respondent receives from other people, e.g., “The pres- tige I have in the eyes of other people”. Respondents were asked how much they are satisfied with what is described in the statements (items). Answers were on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). Attribution for Success. Two separate, 5-item scales from Taormina and Gao (2010) were used to assess the extent to which the respondents evaluated the successes in their life as being determined by their own efforts, for Attribution-to-Self, or the efforts of other people, for Attribution-to-Others. Sample items included “Principally the result of your own effort” (for Self), and “Mostly the result of help received from others” (for Oth- ers). Respondents were asked to what extent they agreed or di- sagreed that their successes in life were due to each reason (scale item). Organizational Socialization. Organizational socialization was measured using Taormina’s (2004) Organizational Socia- lization Inventory, which has four subscales, namely, Training, e.g. “This organization has provided excellent job training for me”, Understanding, e.g., “I know very well how to get things done in this organization”, Coworker Support, e.g., “My rela- tionships with other workers in this company are very good”, and Future Prospects, e.g., “There are many chances for a good career with this organization”. Resilience. This was measured with a 12-item scale. Three items were from Connor and Davidson’s (2003) Resilience scale, i.e., “When things look hopeless, I usually give up” [R], “I am able to make it through difficult times”, and “Coping with stress strengthens me”, and one item was from Lang, Goulet, and Amsel (2003), i.e., “I am easily discouraged by failure” [R]. The remaining items were newly created, i.e., “I do not let things stop me from achieving my goals”, “If something bad happens to me, I will bounce back”, “If I do not succeed at first, I will surely try again”, “I keep on trying even in difficult situa- tions”, “The difficulties in my life have made me a stronger person”, “I am determined to finish what I start despite obsta- cles in the way”, “I am determined to be a survivor, even in the hardest times”, and “I am a person who has great resolve”. Creativity. Creativity was measured with a 10-item scale. Two of the items were from Simonton’s (1986) 12-item Intel- lectual Brilliance factor of his Presidential Personality adjective checklist, and the adjectives were converted to statements, i.e., “I am an insightful person” and “I am an inventive person”. The remaining eight items were newly created, i.e., “I am a very creative person”, “I enjoy coming up with new ideas”, “I have a vivid imagination”, “I like to create new things”, “I en- joy trying different ways of doing things”, “I am very good at brainstorming”, “I am very original in my thinking”, and “I can solve problems that cause other people difficulty”. Conscientiousness. To measure Conscientiousness of the Big Five personality dimensions, its subscale of Perfectionism was assessed. This was a 10-item scale composed of four items from the Perfectionism scale of the HEXACO Personality In- ventory (Lee & Ashton, 2004), two items from the Abridged Big-Five dimensional Circumplex Model (AB5C; Hofstee, deRaad, & Goldberg, 1992), one item from the Revised version of the NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) (Costa & McCrae, 1992), and three newly created items, i.e., “Dislike mistakes”, “Like things to be in order”, and “Am not bothered by mistakes” [R]. Self-Confidence. This was measured by a 10-item scale. Four items were adapted from Lane, Sewell, Terry, Bartram, and Nesti’s (1999) 9-item Self-Confidence Scale of the Com- petitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (e.g., “I feel confidence in myself”). Three items were adapted from Kolb’s (1999) 5-item Self-Confidence Scale (e.g., “I have confidence in my own de- cisions”). Two were adapted items from Hirschfeld et al.’s (1977) 15-item Lack of Social Self-Confidence Scale (e.g., “I am very confident about my own judgments”), and one item was adapted from Day and Hamblin’s (1964) 10-item Self-Esteem and Self-Confidence Scale (e.g., “I usually feel that my opin- ions are inferior”). All the items were slightly reworded to focus more on introspective self-confidence rather than a spe- cific social context. Procedure and Ethical Considerations As the objective of this study was to assess Chinese people on their Work Efficiency and Conflict Handling, a purposive sample of employees was used, i.e., data were collected from employed people in factories and companies in Kunming and Changchun, China. With permission from management, ques- tionnaires were brought to the locations on work days and per- sonally handed to the employees, who were asked to complete them during their break times. The questionnaire took about 10 to 15 minutes to complete, and, when finished, were handed back to the researcher on site. Together, 192 co mpleted questionnaires were returned out of 230 that were handed out, yielding a re- sponse rate of 83.48%. Ethical guidelines of the American Psychological Associa- tion were followed in the study. Informed consent of partici- pants was obtained verbally and through the cover page of the questionnaire, which introduced the survey and gave the re- searcher’s contact information. Potential participants were in- formed that their participation was entirely voluntary, and that they could stop responding at any time. They were also assured that their identities, personal information, and responses would never be revealed to anyone, and that their data would be used only in combined statistical form so that they could never be personally identified. Results Demographi c Dif fer ences Although no hypothese s were made regarding the demograph- ics, t-tests and ANOVAs were performed to assess their differ- ences on the dependent variables of Work Efficiency, Conflict Handling-Avoiding, a nd Conflict Handling-Compromising. For Gender, there was only one significant differe nce, with Fe- males (M = 3.54, SD = 0.73) higher than Males (M = 3.24, SD = 0.87) on Conflict Handling-Avoiding, t(189) = 2.37, p < 0.05. For having Children, there was also only one difference, with the No Children group (M = 3.70, SD = 0.61) higher than the Having Children group (M = 3.45, SD = 0.73) on Conflict Han- dling-Compromising, t(182) = 2.35, p < 0.05. There were no other significant differences among any other demographics on any of the other dependent variables.  W. WEI ET AL. 61 Variable Correlations and Test for Common Method Bias Correlations were computed for all the variables to assess their relationships and to test the hypotheses. Overall, all hy- potheses were supported except four, i.e., not significantly related were: H(2a) Creativity and Conflict Handling -Av oidi ng; H(8a) Self-Confidence and Conflict Handling-Avoiding; H(13a) Attribution for Success to Others and Conflict Han- dling-Avoiding; and H(17) Future Prospects and Work Effi- ciency. To test for possible multicollinearity of the data, common- method bias was assessed by factor analyzing all the variables together, using the maximum-likelihood approach with a forc e d, one-factor solution (see Harman, 1960). The resultant Chi- square value is then divided by the degrees of freedom to assess model fit, whereby a ratio of less than 2.00:1 would indicate common- method bias (i.e., a single factor). For this study, the ratio was 5.63:1, suggesting that common-method bias was not a concern. All of the correlations among the main variables and the de- pendent variables, as well as the means, standard deviations, and Cronbach Alpha reliabilities of the variables, are shown in Table 1. Regressions Three regressions were run to determine the extent to which any of the independent variables could statistically predict the dependent variables. For Work Efficiency, 36% of the variance was explained, F(3,168) = 31.66, p < 0.001. Three variables en- tered the regression equation (all positively), with Attribution for Success to Self explaining 27% of the variance, Self-Confi- dence explaining 7%, and Conscientiousness explaining 2%. For Conflict Handling-Avoiding, 8% of the variance was ex- plained, F(2169) = 7.48, p < 0.001. This time, two variables entered the regression, with Attribution for Success to Self ex- plaining 6%, and Gender explaining 2% (with females higher than males on this variable). For Conflict Handling-Compromising, 26% of the variance was explained, F(3168) = 20.15, p < 0.001. Three variables en- tered this regression (all positively ), with Attribution for Success to Self explaining 21% of the variance, Conscientiousness ex- plaining 3%, and Attribution for Success to Others explaining 2%. Discussion This research examined personality and organizational factors for their relation to employee Work Efficiency and how em- ployees handle work conflicts. While there were a few demo- graphic differences, this discussion centers on the main person- ality variables and their relation to the dependent measures, particularly from the perspective of Chinese culture. Personality, Work Efficiency, and Chinese Culture Among the variables selected for study, Self-Confidence and Conscientiousness have been commonly used in human factors research, while others, especially Creativity, have been used less frequently. In particular, although certain personality variables, namely, Creativity, Resilience, and Esteem from Others, have not been extensively studied before, these factors were found to have significant and positive correlations with Work Efficiency. Fur- thermore, in regard to Chinese culture, even though Creativity and Resilience are often thought to be characteristic of western, “individualistic” culture, both of these variables had relatively high mean scores on their measure ment scales. This suggests that these personality characteristics are not unique to any particular culture, and implies that managers in Chinese cultu re could begin to look at these characteristics among their employees. Table 1. Means, standard deviations, Cronbach alpha reliabilities, and correlations of the main variables (N = 192). Mean SD Work EfficiencyConflict Handling Avoid Conflict Handling Compromise Alpha Reliabilities Work Efficiency 3.95 0.61 - - - 0.93 Conflict-Handling Avoid 3.33 0.83 0.14+ - - 0.83 Conflict-Handling Compromise 3.53 0.69 0.35**** 0.47** - 0.84 Creativity 3.63 0.60 0.40**** 0.09 0.26**** 0.90 Resilience 3.64 0.55 0.35**** 0.15* 0.27**** 0.86 Conscientiousness 3.51 0.42 0.37**** 0.17* 0.30**** 0.69 Self-Confidence 3.68 0.45 0.44**** 0.07 0.19** 0.84 Esteem from Others 3.53 0.58 0.33**** 0.22*** 0.29**** 0.88 Attribution to Self 3.58 0.58 0.50**** 0.24** 0.44**** 0.74 Attribution to Others 2.88 0.69 0.01 0.13 0.16* 0.79 Training 3.46 0.76 0.14+ 0.14+ 0.11 0.88 Understanding 3.69 0.70 0.31**** 0.19** 0.25**** 0.86 Coworker Support 3.67 0.64 0.20** 0.09 0.12 0.81 Future Prospects 3.09 0.83 0.05 0.02 0.03 0.82 + p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.005; **** p < 0.001.  W. WEI ET AL. 62 In traditional Chinese thinking, self-promotion is antithetical to the culture such that creative employees do not come forward, which makes it is difficult to identify them. That is, the hierar- chically structured culture, which is reflected strongly in Chinese organizations, leads the employees to wait for instructions from their superiors. At the same time, the employee with creative ideas would be inhibited from promoting those ideas for fear of being seen as self-aggrandizing, and, consequently, possibly being rejected by his or her coworkers. Likewise, he or she might fear being seen by superiors in a negative light, e.g., since the superior is expected to be the leader, the superior might think the creative employee is imposing on his or her leadership and thereby causing him or her to “lose face” by presenting new ideas that everyone expects the leader to put forward; and/or the leader might regard the creative employee as a bothersome “show-off” who does not fit in with the group. The positive correlations between creativity and work effi- ciency, along with the limiting organizational circumstances for creative people, imply that managers could try to find ways to foster creativity among employees. For example, research has suggested that creativity can be taught (Williams, 2001). At the same time, managers also need to find ways that allow creative employees to propose their creative ideas, e.g., by creating chan- nels (perhaps written ones) through which to put forward those ideas, without suffering negative consequences either from their peers or from their superiors. Personality, Conflict Handling, and Chinese Culture Regarding Conflict Handling, first, it is well known that so- cial harmony is paramount in Chinese culture (Yang, 1995). Thus, among the many ways that conflict could be handled, the two most suitable in Chinese culture are to avoid them or to compromise in order to resolve them amicably (Kirkbride et al., 1991). The results found some personality variables positively related to conflict avoidance (although the correlations were not especially powerful). This might be because avoiding conflict is practiced by almost everyone through out Chinese society, which means that, for Chinese people, no particular personality char- acteristic is especially asso ci ated with avoiding con fli cts. For Conflict Handling-Compromising, there were much stronger positive correlations; and the difference with Avoiding is as follows: The act of avoiding conflict is very easy to do, i.e., when conflicts occur, one only needs to stay away (or walk away) from them. Compromising, however, requires a person to have some special skills to do this successfully. For example, to be good at compromise, one must be able to negotiate, know what to ask for, what to give up, how much to giv e up, and when to give up. The remarkable finding in the results was that many of the variables selected for this study were so highly, significantly, and posi- tively related to compromising. These correlations may be strong for reason s that can be fou nd in Chinese culture. Because of the importance of maintaining social harmony, and since interpersonal conflicts are inevitable in life, it becomes necessary to find ways to compromise that are agreeable to both parties. In looking at the results of the re- gression analyses for predicting the use of compromise, three variables, namely, Conscientiousness, Self-Confidence, and At- tribution to Self for one’s success in life, account for all the ex- plained variance, and this is a strong effect (R2 = 0.26; f 2 = 0.35; for computing effect size, see Cohen, 1992). The correla- tions and the variables that predicted compromise may be de- termined by Chinese culture. In particular, traditional Chinese culture teaches one to be co nscientious in various ways, such as through obedience, work- ing hard, being trustworthy, and maintaining harmony with others (see Chinese Culture Connection, 1987 ). Thus, conscientiousness seems to be advocated in Chinese culture, and its characteristics of being careful and responsible make persons with those quail- ties more effective at reaching mutually agreeable compromises. Regarding Self-Confidence and Chinese culture, there are (an- ecdotal) examples of Chinese Deans in Chinese universities, e.g., one gained self-confidence from successfully attaining a profess- sorship in an overseas university, and, when appointed as Dean in a Chinese university, refused to compromise, using his au- thority as a power to win in any disagreement. But this refusal to compromise led them to be disliked by all his subordinates. On the other hand, when a person abides by Chinese values, he or she would fit better into, and be more likely to succeed in, Chinese society, which includes interacting successfully with other people. With such successful experiences, one becomes more assured about how to reach agreements, including “giving up” something in the process of making compromises in order to maintain harmony with others. For Chinese culture and Attribution for Success to Self, which was the third variable that predicted compromi se, again, one’s past successes and per sona l ach iev em en ts in lif e th at ar e ga in ed thro ugh abiding by Chinese values likely lead to greater self assurance and self reliance, which allows one to be less afraid to make compromises. Overall Summary This study assessed how the Chinese societal preference for harmony may impact two preferred conflict-handling styles in relation to work efficiency; and found a stronger positive cor- relation between handling conflicts by using compromise (ver- sus using avoidance) and work efficiency. Also, Creativity, Re- silience, Conscientiousness, Self-Confidence, Esteem from Others, Attributions for Success to Self, and most of the dimensions of organizational socialization were also positively and significantly related to Work Efficiency. Taken together, the results seem to imply that the Work Efficiency of Chinese employees could be improved in many ways, including through organizational socia- lization and the use of compromise in handling conflicts. Finally, Chinese culture appeared to be very useful in explaining how some social and personality characteristics can be influential in predicting such important outcomes as work efficiency and handling conflicts. References Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in or- ganizations. In B. M. Staw and L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavio r (pp. 123-167). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Antonioni, D. (1998). Relationship between the Big Five personality factors and conflict management styles. International Journal of Conflict Management, 9, 336-355. doi:10.1108/eb022814 Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unravelling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Barki, H., & Hartwick, J. (2004). Conceptualizing the construct of interpersonal conflict. International Journal of Conflict Management, 15, 216-244. doi:10.1108/eb022913 Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality di- mensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psy- chology, 44, 1-26. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x Blake, R. R., & Moutin, J. S. (1964). The managerial grid. Houston, TX: Gulf. Bernardin, H. J., & Beatty, R. W. (1984). Performance appraisal: Assessing human behavior at wor k. Boston: Kent. Chinese Culture Connection (1987). Chinese values and the search for  W. WEI ET AL. 63 culture-free dimensions of culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psy- chology, 18, 143-164. doi:10.1177/0022002187018002002 Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155- 159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety , 18, 76-82. doi:10.1002/da.10113 Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessme nt Resources. Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). NEO-PI-R professional inven- tory manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Reso u rces. Day, R. C., & Hamblin, R. L. (1964). Some effects of close and puni- tive styles of supervision. The American Journal of Sociology, 69, 499-510. doi:10.1086/223653 Gao, J. H. & Taormina, R. J. (2002). Performance appraisal in Zhuhai and Macao. Proceedings of the 7th International Human Resource Management Conference, Limerick: University of Limerick. Hanton, S., & Connaughton, D. (2002). Perceived control of anxiety and its relationship to self-confidence and performance. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 73, 87-97. Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interperson al relations. New York: Wiley. doi:10.1037/10628-000 Hirschfeld, R. M. A., Klerman, G. L., Gough, H. G., Barrett, J., Kor- chin, S. J., & Chodoff, P. (1977). A measure of interpersonal de- pendency. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41, 610-618. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4106_6 Hofstee, W. K., de Raad, B., & Goldberg, L. R. (1992). Integration of the Big Five and circumplex approaches to trait structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 146-163. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.63.1.146 Hwang, K. K. (1987). Face and favor: The Chinese power game. American Journal of Sociology, 92 , 944-974. doi:10.1086/228588 Jacelon, C. S. (1997). The trait and process of resilience. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25, 123-129. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025123.x Kirkbride, P. S., Tang, S. F., & Westwood, R. I. (1991). Chinese con- flict preferences and negotiating behavior: Cultural and psychologi- cal influences. Organization Stud ie s, 12, 365-386. doi:10.1177/017084069101200302 Kolb, J. A. (1999). The effect of gender role, attitude toward leadership and self-confidence on leader emergence: Implications for leadership development. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 10, 305- 320. doi:10.1002/hrdq.3920100403 Lane, A. M., Sewell, D. F., Terry, P. C., Bartram, D., & Nesti, M. S. (1999). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Competitive State Anxi- ety Inventory-2. Journal of Sports Sc ience, 17, 505-512. doi:10.1080/026404199365812 Lang, A., Goulet, C., & Amsel, R. (2003). Lang and Goulet hardiness scale: Development and testing on bereaved parents following the death of their fetus/infant. Death Studi e s, 27, 851-880. doi:10.1080/716100345 Lee, D. M. S. (1986) Academic achievement, task characteristics, and first job performance of young engineers. IEEE Transactions on En- gineering Management, EM-33, 127-133. Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 329-358. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr3902_8 Liu, J., Fu, P., & Liu, S. (2009). Conflicts in top management teams and team/firm outcomes: The moderating effects of conflict-handling approaches. International Journal of Conflict Management, 20, 228- 250. doi:10.1108/10444060910974867 Lu, L., Kao, S. F., Siu, O. L., & Lu, C. Q. (2010). Work stressors, Chi- nese coping strategies, and job performance in Greater China. Inter- national Journal of P s y ch o lo gy , 45, 294-302. doi:10.1080/00207591003682027 Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-396. doi:10.1037/h0054346 Maslow, A. H. (1971). The farther reaches of human nature. Oxford: Viking. Maslow, A. H. (1987). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). Boston: Addison-Wesley. Maxham, J. G., Netemeyer, R. G., & Lichtenstein, D. R. (2008). The retail value chain: Linking employee perceptions to employee per- formance, customer evaluations, and store performance. Marketing Science, 27, 147-167. doi:10.1287/mksc.1070.0282 McCarty, P. A. (1986). Effects of feedback on the self-confidence of men and women. Academy of Management J o u rnal, 29, 840-847. doi:10.2307/255950 Merriam-Webster Dictionary (nd). http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ Oldham G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 607-634. doi:10.2307/256657 Oxford English Dictiona ry (nd). http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/163619 Parker, G., Cowen, E., Work, W., & Wyman, P. (1990). Test correlates of stress resilience among urban school children. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 11, 19-35. doi:10.1007/BF01324859 Paul, R. J. (1967). Increasing the work efficiency of the service em- ployee. Journal of Small Business Management,5, 9-13. Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-es- teem literature. Journal of Manage ment, 30, 591-622. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2003.10.001 Rahim, M. A. (1983). A measure of styles of handling interpersonal conflict. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 368-376. doi:10.2307/255985 Rahim, M. A., Magner, N. R., & Shapiro, D. L. (2000). Do justice perceptions influence styles of handling conflict with supervisors? What justice perceptions, precisely? International Journal of Conflict Management, 11, 9-31. doi:10.1108/eb022833 Rasulzada, F., & Dackert, I. (2009). Organizational creativity and in- novation in relation to psychological well-being and organizational factors. Creativity Research J o urnal, 21, 191-198. doi:10.1080/10400410902855283 Reio, T. G., & Wiswell, A. (2000). Field investigation of the relation- ship among adult curiosity, workplace learning, and job performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 11, 5-30. doi:10.1002/1532-1096(200021)11:1<5::AID-HRDQ2>3.0.CO;2-A Simonton, D. K. (1986). Presidential personality: Biographical use of the Gough Adjective Check List. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 149-160. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.1.149 Taormina, R. J. (1997). Organizational Socialization: A multidomain, continuous process model. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 5, 29-47. doi:10.1111/1468-2389.00043 Taormina, R. J. (2004). Convergent validation of two measures of organizational socialization. International Journal of Human Re- source Management, 1 5 , 76-94. doi:10.1080/0958519032000157357 Taormina, R. J. & Gao, J. H. (2009). Identifying acceptable perform- ance appraisal criteria: An international perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 47, 102-125. doi:10.1177/1038411108099292 Taormina, R. J. & Gao, J. H. (2010). A research model for guanxi be- havior: Antecedents, measures, and outcomes of Chinese social net- working. Social Science Research, 39, 1195-1212. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.07.003 Taylor, F. W. (1911). The principles of scientific management. New York: Harper Bros. Williams, S. (2001). Increasing employees’ creativity by training their managers. Ind u s t ri a l a n d C om m e r c i al Training, 33, 63-68. doi:10.1108/00197850110385642 Wolf, J. R. (1989). Human resource management. Psychiatric Annals, 19, 432-434. Yang, K. S. (1995). Chinese social orientation: An integrative analysis. In T. Y. Lin, W. S. Tseng and E. K. Yeh (Eds.), Chinese Societies and Mental Health (pp. 19-39). Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

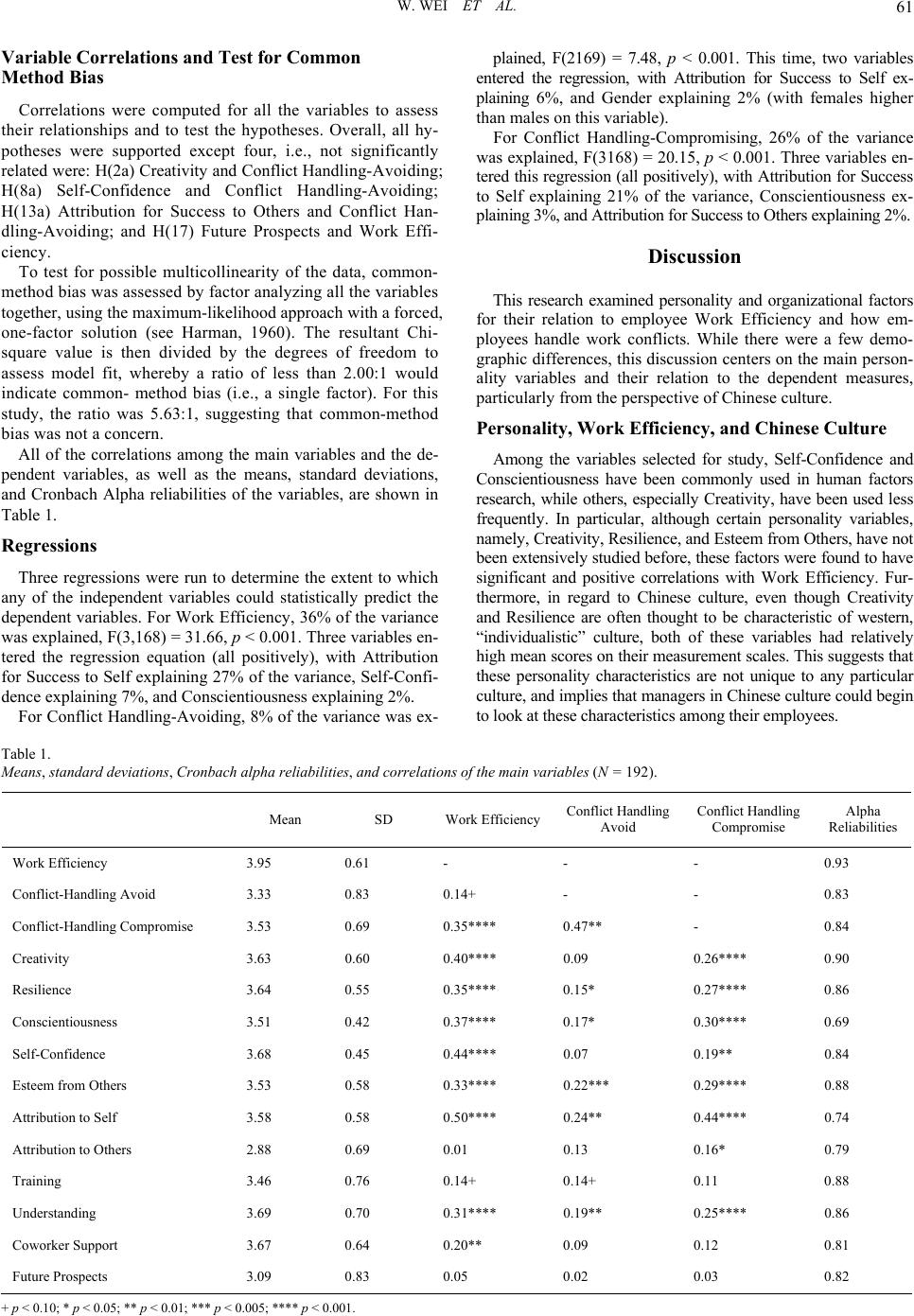

|