Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.07 No.15(2016), Article ID:72230,11 pages

10.4236/jmp.2016.715189

Exact Axisymmetric Solutions of the 2-D Lane-Emden Equations with Rotation

Dimitris M. Christodoulou1, Demosthenes Kazanas2

1Department of Mathematical Sciences and Lowell Center for Space Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, USA

2NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Laboratory for High-Energy Astrophysics, Greenbelt, USA

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: October 14, 2016; Accepted: November 21, 2016; Published: November 24, 2016

ABSTRACT

We have derived exact axisymmetric solutions of the two-dimensional Lane-Emden equations with rotation. These solutions are intrinsically favored by the differential equations regardless of any adopted boundary conditions and the physical solutions of the Cauchy problem are bound to oscillate about and remain close to these intrinsic solutions. The isothermal solutions are described by power-law density profiles in the radial direction, whereas the polytropic solutions are described by radial density profiles that are powers of the zeroth-order Bessel function of the first kind. Both families of solutions decay exponentially in the vertical direction and both result in increasing or nearly flat radial rotation curves. The results are applicable to gaseous spiral-galaxy disks that exhibit flat rotation curves and to the early stages of protoplanetary disk formation before the central star is formed.

Keywords:

Dark Matter, Gravitation, Galaxies, Protoplanetary Disks

1. Introduction

We use a new method to solve analytically the axisymmetric Lane-Emden equations [1] [2] with rotation in two dimensions. The method is an extension of the one-dimensional algorithm that we applied to ordinary second-order differential equations of mathematical physics [3] [4] [5] and produces separable equations in two dimensions [6] . The solutions are intrinsically favored by the differential equations themselves and dictate that the physical solutions of the Cauchy problem should oscillate about and remain close to these preferred solutions [4] [5] .

The two-dimensional analytic solutions show that both the densities and the rotation speeds decay exponentially with height from the symmetry plane  while the radial rotation curves are increasing or nearly flat at all heights. Thus, the Newtonian rotation profiles so derived are similar to the “flat” rotation curves observed in gaseous spiral galaxies [7] without the need of invoking dark matter [8] - [22] or the various modifications of the Newtonian dynamics [23] - [30] .

while the radial rotation curves are increasing or nearly flat at all heights. Thus, the Newtonian rotation profiles so derived are similar to the “flat” rotation curves observed in gaseous spiral galaxies [7] without the need of invoking dark matter [8] - [22] or the various modifications of the Newtonian dynamics [23] - [30] .

In what follows, we derive the exact solutions of the 2-D Lane-Emden equations with rotation in the isothermal case (Section 2) and in the general polytropic case (Section 3), and we discuss the astrophysical implications of our results (Section 4).

2. Isothermal Self-Gravitating Newtonian Gaseous Disks

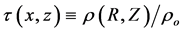

We use the scaling constants  and

and  to normalize the cylindrical coordinates (R, Z) and the density profiles

to normalize the cylindrical coordinates (R, Z) and the density profiles , respectively. We thus define the dimensionless radius

, respectively. We thus define the dimensionless radius , height

, height , and density

, and density . Velocities

. Velocities  are also normalized consistently by the constant

are also normalized consistently by the constant , where G is the Newtonian gravitational constant, in which case we define the dimensionless rotation velocity

, where G is the Newtonian gravitational constant, in which case we define the dimensionless rotation velocity . The same scaling also applies to the sound speed

. The same scaling also applies to the sound speed  of the gas which in this section is a constant, i.e., the dimensionless sound speed is

of the gas which in this section is a constant, i.e., the dimensionless sound speed is .

.

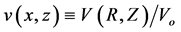

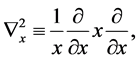

The 2-D axisymmetric isothermal Lane-Emden equation with rotation [1] [2] [5] can then be written in dimensionless form as

(1)

(1)

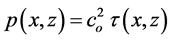

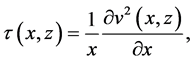

where  and v are functions of x and z, and

and v are functions of x and z, and

(2)

(2)

and

(3)

(3)

This equation describes the axisymmetric equilibrium of a rotating, self-gravitating, gaseous disk in which the gas obeys the isothermal equation of state  , where p is the dimensionless pressure of the gas.

, where p is the dimensionless pressure of the gas.

If we equate the last two terms of Equation (1), viz.

(4)

(4)

then this is an intrinsic solution [4] [5] provided that the rest of the equation also vanishes:

Equations ((4) and (5)) form a system in which

We now introduce the following scaling relations in the z-direction:

where the three new functions

This is precisely the equation that was solved by [5] on the symmetry plane

The two terms are independent, thus they must be constant and the constants should combine to produce zero. We can then write

where the separation constant

where the integration constant c is taken to be negative to guarantee monotonically decreasing density profiles away from the symmetry plane

where

in which case the solutions become

and

Equation (14) was derived by [5] for

where

Figure 1 shows the density profile

3. Polytropic Self-Gravitating Newtonian Gaseous Disks

The 2-D axisymmetric polytropic Lane-Emden equation with rotation [1] [2] [5] can be written in dimensionless form as

where

We repeat the procedure outlined in Section 2 in order to obtain the intrinsic solution of Equation (16): If we equate the last two terms of Equation (16), viz.

then this is an intrinsic solution [4] [5] provided that the rest of the equation also vanishes:

Figure 1. Density solution

Equations (17) and (18) form a system in which

We now introduce the scaling relations (6) in the z-direction, where the three functions

as was also found in the isothermal case of Section 2.

Substituting the first of Equations (6) into Equation (18) and diving all terms by

The two terms are independent, thus they must be constant and the constants should combine to produce zero. We can then write

where the separation constant

where the particular solution with the minus sign was chosen so that

where A is the integration constant and the Bessel function of the first kind was chosen because it does not diverge at

except in cases of even polytropic indices n in which they produce rings touching one another at consecutive zeroes of

The solutions in the entire (

where

where

where

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the density and rotation profiles, respectively, of the

Figure 2. Density solution

Figure 3. Rotation profile

Figure 4. Ring-like density solution

Figure 5. Rotation profile

values of

In the inner region of the rotation profile of Figure 3, the contours are nearly vertical as expected from measurements of the rotation profile of the Milky Way [33] . In the outer region where the rotation speeds are larger, the contours are however tilted and the tilt becomes more pronounced for larger values of

Figure 7 shows the radial rotation curve

Figure 6. Rotation profile

Figure 7. Polytropic rotation curve

continues to increase with radius as it passes through a sequence of inflection points. Each jump in the profile represents the rotation curve inside the next outward ring.

4. Discussion

In this work, we derived exact axisymmetric solutions of the 2-D Lane-Emden equations with rotation. In the isothermal case, the solutions show a power-law dependence on the radius x and an exponential decline with height

The gaseous disk equilibria produced in Sections 2 and 3 are Newtonian in nature and they all have rising or asymptotically flat radial rotation curves. Such rotation profiles are demanded by the analytic solutions for self-consistency. The resulting Newtonian models argue against the need to assume the existence of dark matter in spiral galaxies in order to produce the observed flat rotation curves and against the need to modify the Newtonian dynamics to achieve the same effect (references were given in Section 1). The same models may also prove useful in studies of the rotation curves in protoplanetary disks [34] [35] [36] at their very early stages of evolution and before the central star is formed.

It is important to note that the flat and rising rotation profiles were not prescribed as input to the Lane-Emden equations; instead, they were the result of the intrinsic equilibrium solutions. Similar types of rotation profiles have been previously found in models of Newtonian gaseous disks [37] [38] [39] [40] but they were dismissed because they were thought to be peculiar in nature. We now find that these models were giving us clues as to the true behavior of the gas in self-gravitating astrophysical disks.

The main obstacle in understanding the dynamical behavior of gas in spiral galaxies is an old argument [7] that relies solely on particle dynamics―that an orbiting particle at radius r enclosing mass

Acknowledgements

We thank Joel Tohline for feedback and guidance over many years.

Cite this paper

Christodoulou, D.M. and Kazanas, D. (2016) Exact Axisymmetric Solutions of the 2-D Lane-Emden Equations with Rotation. Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 2177-2187. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.715189

References

- 1. Lane, J.H. (1870) Amer. J. Sci. Arts, Second Series, L, 57.

- 2. Emden, R. (1907) Gaskugeln, Leipzig, B.G. Teubner.

- 3. Christodoulou, D.M., Graham-Eagle, J. and Katatbeh, Q.D. (2016) Advances in Difference Equations, 2016, 48.

https:/doi.org/10.1186/s13662-016-0774-x - 4. Christodoulou, D.M., Katatbeh, Q.D. and Graham-Eagle, J. (2016) Journal of Inequalities and Applications, 2016, 147.

https:/doi.org/10.1186/s13660-016-1086-0 - 5. Christodoulou, D.M. and Kazanas, D. (2016) Journal of Modern Physics, 7, 680-698.

https:/doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.77067 - 6. Jackson, J.D. (1962) Classical Electrodynamics. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- 7. Binney, J. and Tremaine, S. (1987) Galactic Dynamics. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton.

- 8. Freeman, K.C. (1970) Astrophysical Journal, 160, 811.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/150474 - 9. Bosma, A. (1978) The Distribution and Kinematics of Neutral Hydrogen in Spiral Galaxies of Various Morphological Types. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen.

- 10. Rubin, V.C., Ford Jr., W.K. and Thonnard, N. (1980) Astrophysical Journal, 238, 471.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/158003 - 11. Bosma, A. (1981) Astronomical Journal, 86, 1791-1846.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/113062 - 12. Bosma, A. (1981) Astronomical Journal, 86, 1825-1846.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/113063 - 13. Rubin, V.C., Ford Jr., W.K., Thonnard, N. and Burstein, D. (1982) Astrophysical Journal, 261, 439-456.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/160355 - 14. Van Albada, T.S. and Sancisi, R. (1986) Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A, 320, 447-464.

https:/doi.org/10.1098/rsta.1986.0128 - 15. Begeman, K.G. (1987) HI Rotation Curves of Spiral Galaxies. PhD Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen.

- 16. Begeman, K.G. (1989) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 223, 47-60.

- 17. Persic, M. and Salucci, P. (1990) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 245, 577.

- 18. Carignan, C., Charbonneau, P., Boulanger, F. and Viallefond, F. (1990) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 234, 43-52.

- 19. Broeils, A. (1992) Dark and Visible Matter in Spiral Galaxies. PhD Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen.

- 20. Persic, M. and Salucci, P. (1995) Astrophysical Journal Supplement, 99, 501.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/192195 - 21. Persic, M., Salucci, P. and Stel, F. (1996) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 281, 27-47.

https:/doi.org/10.1093/mnras/278.1.27 - 22. Salucci, P. and Persic, M. (1997) Dark Halos around Galaxies. In: Persic, M. and Salucci, P., Eds., Dark and Visible Matter in Galaxies, ASP Conference Series 117, 1.

- 23. Milgrom, M. (1983) Astrophysical Journal, 270, 365-370.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/161130 - 24. Tohline, J.E. (1983) Stabilizing a Cold Disk with a 1/r Force Law. In: Athanassoula, E., Ed., Internal Kinematics and Dynamics of Galaxies, Springer, Berlin, 205-206.

https:/doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-7075-5_56 - 25. Felten, J.E. (1984) Astrophysical Journal, 286, 3-6.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/162569 - 26. Sanders, R.H. (1984) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 136, L21-L23.

- 27. Sanders, R.H. (1986) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 223, 539-555.

https:/doi.org/10.1093/mnras/223.3.539 - 28. Mannheim, P.D. and Kazanas, D. (1989) Astrophysical Journal, 342, 635-638.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/167623 - 29. Mannheim, P.D. and O’Brien, J.G. (2011) Physical Review Letters, 106, Article ID: 121101.

https:/doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.121101 - 30. Mannheim, P.D. and O’Brien, J.G. (2012) Physical Review D, 85, Article ID: 124020.

- 31. Abramowitz, M. and Stegun, I.A. (1972) Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Dover, New York.

- 32. Rosenheinrich, W. (2016) Tables of Some Indefinite Integrals of Bessel Functions.

http://www.eah-jena.de/rsh/Forschung/Stoer/besint.pdf - 33. Levine, E.S., Heiles, C. and Blitz, L. (2008) Astrophysical Journal, 679, 1288-1298.

https:/doi.org/10.1086/587444 - 34. Williams, J.P. and Cieza, L.A. (2011) Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 49, 67-117.

https:/doi.org/10.1146/annurev-astro-081710-102548 - 35. Belloche, A. (2013) Observation of Rotation in Star Forming Regions: Clouds, Cores, Disks, and Jets. In: Hennebelle, P. and Charbonnel, C., Eds., Angular Momentum Transport during Star Formation and Evolution, EAS Pub. Ser. 62, 25.

- 36. Tsitali, A.E., Belloche, A., Commerçon, B. and Menten, K.M. (2013) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 557, Article Number: A98.

https:/doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321204 - 37. Hayashi, C., Narita, S. and Miyama, S.M. (1982) Progress of Theoretical Physics, 68, 1949-1966.

https:/doi.org/10.1143/PTP.68.1949 - 38. Narita, S., Kiguchi, M., Miyama, S.M. and Hayashi, C. (1990) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 244, 349-356.

- 39. Schneider, M. and Schmitz, F. (1995) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 301, 933-940.

- 40. Marr, J.H. (2015) Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 448, 3229-3241.

https:/doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stv216