Modern Economy

Vol. 3 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 21292 , 4 pages DOI:10.4236/me.2012.34061

Introducing Liability Dollarization and Contractionary Depreciations to the IS Curve

Department of Economics, Amherst College, Amherst, USA

Email: ahonig@amherst.edu

Received April 17, 2012; revised May 15, 2012; accepted June 1, 2012

Keywords: liability dollarization; IS curve

ABSTRACT

This paper presents a simple modification to the standard IS curve used, at least implicitly, by policymakers that allows capital flight to have a contractionary effect in emerging market economies. In the standard model, capital flight leads to an expansionary shift in the IS curve through an increase in net exports. However, in the presence of liability dollarization for domestic firms, a currency depreciation triggered by capital flight leads to an investment collapse. A simple adjustment to the standard investment schedule captures this channel and allows for the possibility that capital flight yields a contractionary shift in the IS curve.

1. Introduction

In the basic short run open economy model found in macroeconomics textbooks and used, at least implicitly, in policymaking, an episode of capital flight or a sudden stop of capital inflows is expansionary.1 The intuition is that the reduction in inflows and/or increase in outflows and the depreciation of the domestic currency stimulate net exports, which then increases output. While this result holds for advanced economies, it contradicts reality in the case of emerging market countries where sudden stops are usually contractionary.

The key feature of emerging economies that produces this different outcome is that their debt is often denominated in a foreign currency such as the dollar. The presence of liability dollarization implies that large depreciations can lead to significant reductions in net worth by inflating the domestic currency value of borrowers’ loans (De Nicoló, Honohan, Ize [5]; Mishkin [6]). The financial accelerator literature then provides a link from changes in net worth to investment. Specifically, in the presence of financial frictions such as imperfect monitoring and enforcement of contracts, a large decline in net worth can lead to a sharp rise in the cost of borrowing as poorly-collateralized firms must pay a higher premium for external funds (Bernanke and Gertler [7]). In extreme cases, firms may face liquidity and insolvency problems that restrict their growth. Therefore, a large currency depreciation can trigger an investment collapse that can potentially dominate the traditional expansionary effect through net exports.

In fact, more recent research on the effects of exchange rate devaluations has placed greater emphasis on this financial or balance sheet channel than the traditional trade channel (c.f. Krugman [8]; Frankel [9]). This literature includes 3rd generation currency crisis models in which financial factors play a primary role in the propagation of crises (Aghion, Bacchetta and Banerjee [10]; Céspedes, Chang and Velasco [11]). There is also a growing empirical literature testing the relevance of these balance sheet effects (see Galindo, Panizza and Schiantarelli [12] for an empirical survey). For example, Aguiar [13] finds that Mexican firms with heavy exposure to short-term foreign currency debt before the 1994 devaluation experienced relatively low levels of post-devaluation investment. Specifically, observed foreign currency debt exposure reduced net investment rates for 1995 from positive 1% to negative 3.6% following the December, 1994 depreciation. Furthermore, annual GDP growth was 4.5% for 1994 and −6.2% in 1995. Thus the effects of depreciations can impact investment and output soon after the depreciation occurs.

Bebczuk, Galindo and Panizza [14] present macro evidence of this effect using a large sample of countries during the period 1976-2003, finding that the presence of liability dollarization weakens the expansionary effect through the standard trade channel. Specifically, in countries with low levels of liability dollarization, a 20% depreciation is associated with a 0.5 percentage point increase in the growth rate of GDP per capita the following year. However, in countries with significant dollar liabilities, including most of their developing country sample, devaluations are in fact contractionary. They also test whether the contractionary effect works through investment or consumption. They find that depreciations significantly impact investment growth but not consumption growth, concluding that investment is the main channel through which depreciation affect output.

2. The Model

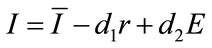

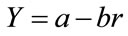

The result that capital flight is expansionary therefore contradicts both theoretical and empirical results for emerging market economies with liability dollarization. To bridge this gap, this paper presents a very simple modification of the standard IS curve that allows for the possibility of contractionary depreciations. The key insight is that a depreciation can lead to a decline in investment if firms suffer from liability dollarization and a decline in consumption if households have borrowed in dollars. Letting E represent the nominal exchange rate (foreign currency per domestic currency), then the investment function

(1)

(1)

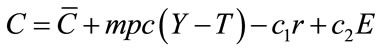

captures the effect of the exchange rate on investment, in addition to the standard interest rate effect. In particular, a fall in E for a given r leads to a decline in investment. As mentioned above, this effect requires some imperfection in capital markets so that investment depends on net worth, as in the financial accelerator model. Similarly, the consumption function

(2)

(2)

allows the exchange rate to have independent effects on consumption through household balance sheets.

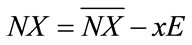

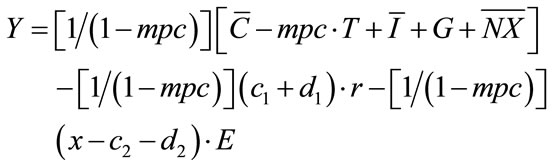

The rest of the model is standard. The determination of net exports is given by  (c.f. Abel, Bernanke and Croushore [4]; Mishkin [3]), where I have assumed sticky prices so that changes in the nominal exchange rate affect the real exchange rate and therefore net exports.2 Assuming that government spending G and taxes T are set exogenously, we can write the open economy IS curve as:

(c.f. Abel, Bernanke and Croushore [4]; Mishkin [3]), where I have assumed sticky prices so that changes in the nominal exchange rate affect the real exchange rate and therefore net exports.2 Assuming that government spending G and taxes T are set exogenously, we can write the open economy IS curve as:

(3)

(3)

or

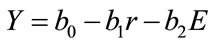

. (4)

. (4)

“ ” includes the effect of government spending, taxes, and autonomous changes in consumption, investment, and net exports. Since a rise in r lowers investment and consumption, it is assumed that b1 > 0. The traditional assumption is that b2 > 0, assuming the Marshall-Lerner conditions are satisfied. However, in the presence of liability dollarization, the effect of a currency depreciation on household and firm balance sheets lowers consumption and investment. If this effect dominates the traditional trade effect so that

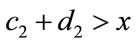

” includes the effect of government spending, taxes, and autonomous changes in consumption, investment, and net exports. Since a rise in r lowers investment and consumption, it is assumed that b1 > 0. The traditional assumption is that b2 > 0, assuming the Marshall-Lerner conditions are satisfied. However, in the presence of liability dollarization, the effect of a currency depreciation on household and firm balance sheets lowers consumption and investment. If this effect dominates the traditional trade effect so that , the depreciation results in a contractionary shift in the IS curve.

, the depreciation results in a contractionary shift in the IS curve.

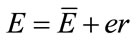

Substituting in a positive relationship between E and r (which can be derived, for example, from an interest rate parity condition) yields an open economy IS curve in which the coefficient of r incorporates the effects of E. Specifically, suppose the nominal exchange rate is given by , where “e” captures the sensitivity of the exchange rate to the domestic real interest rate and

, where “e” captures the sensitivity of the exchange rate to the domestic real interest rate and  captures exogenous changes in the exchange rate. Substituting this relationship into equation (4) yields

captures exogenous changes in the exchange rate. Substituting this relationship into equation (4) yields

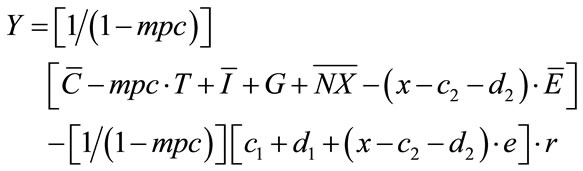

(5)

(5)

or

(6)

(6)

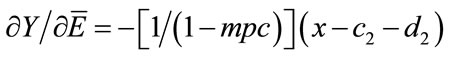

Capital flight or sudden stops of capital inflows can be captured by a decrease in , which exogenously depreciates the exchange rate for a given real interest rate. Thus the effects of capital flight are given by

, which exogenously depreciates the exchange rate for a given real interest rate. Thus the effects of capital flight are given by

(7)

(7)

An episode of capital flight that causes an exogenous depreciation therefore leads to a fall in Y if the contractionary effects on consumption and investment, captured by , outweigh the expansionary effect on net exports, given by x.3 The former effects are likely to be large in countries with a high share of dollar liabilities, producing the observed result that sudden stops are contractionary in such economies. This characterization describes many of the emerging economies in East Asian, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Graphically, the effect of capital flight on investment is captured by a leftward shift in the investment schedule (with r on the vertical axis), which acts to shift the IS curve left. Similarly, the effect on consumption is captured by a rightward shift in the savings line, which also shifts the IS curve to the left.

, outweigh the expansionary effect on net exports, given by x.3 The former effects are likely to be large in countries with a high share of dollar liabilities, producing the observed result that sudden stops are contractionary in such economies. This characterization describes many of the emerging economies in East Asian, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Graphically, the effect of capital flight on investment is captured by a leftward shift in the investment schedule (with r on the vertical axis), which acts to shift the IS curve left. Similarly, the effect on consumption is captured by a rightward shift in the savings line, which also shifts the IS curve to the left.

A contractionary shift in the IS curve then implies a similar shift in the aggregate demand curve. This is true if one is assuming monetary base targeting and an AD curve based on the IS-LM model or if one is assuming interest rate targeting and a Taylor rule to generate the AD curve (however, the size of the shift in the AD curve will depend on the particular model). Combined with an upward sloping AS curve, the end result is still a fall in output.

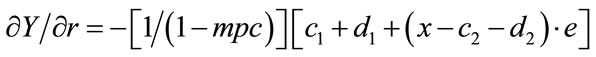

Liability Dollarization and the Potency of Monetary Policy The presence of liability dollarization also has implications for the slope of the IS curve and the potency of monetary policy. The effect of a change in interest rates on output is given by

(8)

(8)

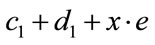

The traditional effects of a change in the real interest rate on consumption, investment, and net exports are captured by . In particular, a fall in the real interest rate stimulates consumption and investment directly and depreciates the currency, thereby indirectly stimulating net exports.

. In particular, a fall in the real interest rate stimulates consumption and investment directly and depreciates the currency, thereby indirectly stimulating net exports.

However, in the presence of liability dollarization, lower interest rates induce a depreciation that lowers consumption and investment, captured by . These additional effects weaken the expansionary effect of lower interest rates.4 Graphically, the presence of liability dollarization steepens a downward sloping investment function by counteracting the stimulative effect of lower interest rates. This implies a steeper IS curve and a weaker effect of expansionary monetary policy. Similarly, liability dollarization makes consumption less sensitive to change in r. This steepens the savings line, which steepens the IS curve and again makes monetary policy less potent.

. These additional effects weaken the expansionary effect of lower interest rates.4 Graphically, the presence of liability dollarization steepens a downward sloping investment function by counteracting the stimulative effect of lower interest rates. This implies a steeper IS curve and a weaker effect of expansionary monetary policy. Similarly, liability dollarization makes consumption less sensitive to change in r. This steepens the savings line, which steepens the IS curve and again makes monetary policy less potent.

3. Conclusion

This paper presents a modification to the standard IS curve that captures the reality in most emerging market nations that sudden stops are contractionary events, and in many cases, highly contractionary. The key mechanism that produces this result is that when domestic firms or households have dollar liabilities on their balance sheets without corresponding dollar assets, exchange rate depreciations that occur during sudden stops can lead to large reductions in net worth. This can lead to higher borrowing costs and, in some cases, insolvency, both of which combine to reduce aggregate demand and output. Adding the exchange rate to the investment and consumption equation captures this channel. Depending on the extent of liability dollarization, the model can generate expansionary depreciations in more advanced economies with little liability dollarization or contractionary depreciations in those that suffer from significant liability dollarization.

REFERENCES

- O. Blanchard, “Macroeconomics,” 5th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2009.

- N. G. Mankiw, “Macroeconomics,” 7th Edition, Worth Publishers, Richmond, 2010.

- F. S. Mishkin, “Macroeconomics: Policy and Practice,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2011.

- A. Abel, B. Bernanke and D. Croushore, “Macroeconomics,” 6th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2007.

- G. De Nicoló, P. Honohan and A. Ize, “Dollarization of the Banking System: Causes and Consequences,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 29, 2005, No. 7, pp. 1697- 1727. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.06.033

- F. S. Mishkin, “Understanding Financial Crises: A Developing Country Perspective,” In: M. Bruno and B. Pleskovic, Eds., Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics, World Bank, Washington DC, 1996, pp. 29-62.

- B. S. Bernanke and M. Gertler, “Agency Costs, Net Worth, and Business Fluctuations,” American Economic Review, Vol. 79, No. 1, 1989, pp. 14–31.

- P. Krugman, “Balance Sheets, the Transfer Problem, and Financial Crises,” Princeton University, Princeton, 1999.

- J. Frankel, “Contractionary Currency Crises in Developing Countries,” NBER Working Paper No. 11508, 2005.

- P. Aghion, P. Bacchetta, and A. Banerjee, “A Simple Model of Monetary Policy and Currency Crises,” European Economic Review, Vol. 44, No. 4-6, 2000, 728-738. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(99)00053-7

- L. F. Céspedes, R. Chang and A. Velasco. “Balance Sheets and Exchange Rate Policy,” American Economic Review, Vol. 94, No. 4, 2004, pp. 1183-1193. doi:10.1257/0002828042002589

- A. Galindo, U. Panizza and F. Schiantarelli, “Debt Composition and Balance Sheet Effects of Currency Depreciation: A Summary of the Micro Evidence,” Emerging Markets Review, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2003, pp. 330-339. doi:10.1016/S1566-0141(03)00059-1

- M. Aguiar, “Investment, Devaluation, and Foreign Currency Exposure: The Case of Mexico,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 78, No. 1, 2005, pp. 95-113. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.06.012

- R. Bebczuk, A. Galindo and U. Panizza, “An Evaluation of the Contractionary Devaluation Hypothesis,” InterAmerican Development Bank Working Paper 582, 2006.

NOTES

1Although textbooks do not explicitly state that sudden stops are expansionary, this result is implied by the models that are used. Furthermore, textbooks do claim that exogenous depreciations and/or devaluations (which are triggered by sudden stops) are expansionary (Blanchard [1]; Mankiw [2]; Mishkin [3]). Abel, Bernanke and Croushore [4] go so far as to claim that a rise in foreign interest rates (historically one of the main causes of sudden stops) is expansionary.

2The setup is slightly different in Mankiw [2], where net capital outflow in a large open economy is modeled as a function of the real interest rate (a higher domestic r reduces outflows and increases inflows as the expected return to lending domestically rises). The level of net capital outflow then pins down the level of NX by the balance of payments identity. In this setup, it is still the case that capital flight has the potential to shift the IS curve to the left.

3The empirical evidence cited above that depreciations have much larger and statistically significant effects on investment than on consumption imply that c2 < d2.

4In extreme cases, if , lower interest rates actually reduce output, implying a positively sloped IS curve. This corresponds to the case when b < 0 in Equation (6). This could occur in countries with very high levels of liability dollarization.

, lower interest rates actually reduce output, implying a positively sloped IS curve. This corresponds to the case when b < 0 in Equation (6). This could occur in countries with very high levels of liability dollarization.