Health

Vol.5 No.3A(2013), Article ID:29606,10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.53A082

Psychological quality of life and employability skills among newly registered first-year students: Opportunities for further university development

![]()

1Research Unit INSIDE, University of Luxembourg, Walferdange, Luxembourg; *Corresponding Author: michele.baumann@uni.lu

2INSERM, U669, University of Paris-Sud and Paris Descartes University, Paris, France

Received 9 January 2013; revised 15 February 2013; accepted 23 February 2013

Keywords: Psychological WHOQoL-Bref; Newly-Registered Students; Academic Employability Skills; Quality of Life

ABSTRACT

In accord with new European university reforms initiated by the Bologna Process, our objective was to evaluate influences on the relationship between psychological quality of life (QoL) and the acquisition of academic employability skills (AES) among first-year students at the University in Luxembourg. At the beginning (2 months in) and the end (9 months) of the academic year, 973 newly registered students participated in this study involving two cross-university surveys. Students who redoubled or who had studied at other universities were excluded. Data were collected with an online questionnaire comprising the psychological Whoqol-bref subscale, AES scale, and questions about other related factors. The AES score decreased from 74.2 to 65.6. At both time points, the psychological Whoqol-bref was positively correlated with environmental and social relations QoL and perceived general health. Multiple regression models including interaction terms showed that a higher psychological QoL was associated with better general health (difference satisfied-dissatisfied 9.44), AES (slope 0.099), social relationships QoL (0.321), and environmental QoL (0.298). No interaction with time effects was significant, which indicates that the effects remain stable with time. If the university could maintain the QoL indicators at appropriate levels or manage decreases as they occur, it would have implications for health promotion and the creation of new student support systems. The SQALES project provides valuable information for universities aiming to develop a European Higher Educational Area.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the European Union, quality of life (QoL) is a high social and public health policy priority that reflects wider public concerns [1]. The European Pact signed in Brussels recognized that the mental health and well-being of the population play essential roles in the economic and social success of the Union [2]. Additionally, mental health of university students represents an important and growing public health issue [3]. The past decade has seen a expansion in the numbers of students in further and higher education. With this growth has come increasing recognition of mental health problems in the student population and calls for better integration of educational and health care [4].

Quality of life (QoL) is defined as “individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” [5]. A novel simultaneous “spoke-wheel” methodology designed by the WHOQOL Group used international collaborations to improve equivalence [6,7]. A landmark review by Bowden and Fox-Rushby [8] concluded that the WHOQOL is the best available instrument for crosscultural use. Some recent investigations into student QoL have been conducted with the short version of the WHOQOL scale (Whoqol-bref, 26 items) [6], including the use of various domains among medical students from Australia [9], nursing students from Brazil [10], other students from Brazil [11], health service students from Turkey [12], and social sciences students from Brazil [13]. In our study, we focused on psychological QoL, a domain of the Whoqol-bref; however, we could find no studies in the scientific literature using this widely applied subscale as a dependent variable. Nevertheless, a few studies have examined the links between QoL globally and in its four domains (psychological, physical, social and environmental) [14], and their performance and applicability, principally among early adolescents [15] and students [16], and compared students’ QoL with that of an adult community sample [17]. Some researchers analysed the relationships between QoL and loneliness [12], parental rearing [18], and health enhancement programmes [9].

Student life, particularly the first year, is a period of vulnerability during which young people establish and adjust new psychological identities [19,20]. The social and academic circumstances at university expose students to a number of socio-economic, environmental and psychological factors that may result in altered health status [21,22]. First-year students undergo a certain amount of stress due to difficulties in coping with the studies and with possible financial and social issues in their new life with more autonomy. Despite many somatic (tiredness, headaches, backaches), psychological (depression, suicidal tendencies) and behavioural (eating habits, addictive behaviours) disorders, very few longitudinal studies have been dedicated to student stress and health. Existing studies in this area tend to be descriptive and cross-sectional rather than explanatory [23].

In order to create a European Higher Educational Area, in 1999 the Bologna process initiated a series of reforms intended to achieve performance matching that of the best systems in the world aimed at fulfilling the Lisbon strategy goals for growth. Specific changes were: introduction of the three-cycle system (bachelor/master/doctorate), quality assurance, and recognition of qualifications and periods of study. Every second year from then on, Ministers responsible for higher education in the 46 Bologna countries have met to measure progress and set priorities for action. Venues so far have been: Prague (2001), Berlin (2003), Bergen (2005), London (2007) and Leuven/Louvain-La-Neuve (2009)

Today’s students are expected to acquire more and more employability skills while maintaining their quality of life. Psychological distress is associated with academic failure, job difficulties, and diverse social outcomes later in life [24,25]. Furthermore, students are susceptible to depressive mood and anxiety as modern universities become competitive environments that must enable them to meet occupational requirements under stressful conditions [26-28] with an impact on academic achievement [29,30]. In that context, the Human Resources Development Canada Department of Research has created a self-rated questionnaire for university students to gauge how convinced they are of having the academic skills needed for employment according to the following dimensions: communication, interpersonal relations, and capacity for innovation [31]. Our study uses a self-administered measure. However, consistent with positional conflict theory the self-perceived skills relative to employability may be a product of relative societal expectations [32]. This theory suggests that there may be a link between biographic measures and self-perceived employability competencies. In this context the biographic measures could be seen as perception of the strength of the university’s brand in the region or prestige of the chosen faculty. In addition the skills relative to employability of these participants give us information about their perceptions without providing any data on actual employability state.

The Grand-duchy of Luxembourg is the smallest country in Europe (502,500 population, 2600 km2) and one of most multilingual and culturally diverse Nation States (with more than 150 different nationalities). The University of Luxembourg, opened in 2003, is the youngest, indeed the only, such institution. The Students’ Quality of Life and Employability Skills (SQALES) project was initiated by the research unit INSIDE [33] to: 1) meet the recommendations adopted at Bergen (2005) under the Bologna Process that call on universities for high levels of competition and production; and 2) help all those involved in university education to produce guidance and advice taking some account of existing facilities (health promotion activities, employability workshops, counselling services, support for university work, student union welfare officers) and opportunities for further development. From this perspective, there is a real need for universities to evaluate the psychological health of students.

Newly registered students are of most interest: they are just discovering university life, and are younger, and issues should emerge and be available for investigation sooner. This information will be of value to our new university and to others who conduct similar work in the future. The aim is to help all involved in university education to produce guidance and advice taking some account of the prospects and implications for further development, whether or not in terms of health promotion programmes as recommended by the Charter of Ottawa and the network of the Foundation of European Regions for Research in Education and Training [34]. The new missions for European universities taking part in the reforms initiated by the Bologna process are to: 1) guarantee students a quality of life favourable to their studies; 2) promote their employability; 3) assess their satisfaction; 4) provide guidance and support to those looking for employment; 5) encourage and develop a participatory process [35]. Studies such as this are important in order to highlight the value of establishing help and support services for students, although there may be some disparities due to differences in the socio-economic context and organisational factors.

Our research is an original study because there is few relevant scientific literature concerning: first, the values of QoL domains among first-year university students; second, the relation between psychological QoL and the academic Employability skills (AES) that students must now acquire; and third this link between the beginning and the end of the first cycle. The objectives of our study were to analyse the influences, at two times over the course of the first year, on the association between psychological QoL and AES, and general health, social relationships and environmental QoL, and sociodemographic characteristics among newly registered students.

2. METHOD

2.1. Population

The 973 newly registered students (those redoubling were excluded, as were those who had studied at other universities) in the first year of the bachelors/licences stage in three faculties (Sciences & Technology, Law & Finance, and Social Sciences) were invited to participate in a survey involving data collection at two time points: two months and nine months after the beginning of the academic year.

2.2. Ethics

The protocol was approved in advance by the Ethical Research Committee of the University, and informed signed consent was obtained from all respondents. Representatives of student associations and a member of the research team provided information about the goals of the survey. The Ethical Research Committee and the Study Directors considered the online questionnaire more appropriate than “asking students to fill in the survey during courses”. This is the usual procedure in student research, but its value is open to question, particularly if the objective is to systematically collect data free of potential bias due to interaction between university staff and students.

2.3. Protocol

The students were invited to participate at the two surveys via an anonymous process involving a website address. During a class period, the research team (with the cooperation of representatives of student associations) presented the aims of the survey. Students were then contacted at their university email addresses and asked to complete an online self-reported questionnaire via an anonymous process in the language of their choice: French, German or English.

2.4. Material

Three groups of variables were collected:

a) Psychological Whoqol-bref (6 items) is a subscale of the Whoqol-bref tool (26 items) [36] which measured negative feelings, positive feelings, self-esteem, spirituality, thinking, and bodily image. The internal consistency Cronbach’s alpha (reliability and inter-item correlation) was calculated among all students (0.77). This international instrument was validated in the languages used for the investigation: German [37], French [38], and English [6].

b) AES (6 items) were assessed using measuring their perceived competencies or capacities to write, think critically, solve problems, work effectively with others, lead others, and use new technology. Each respondent estimated his or her level on a four point scale (not very good to excellent) ; the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76. English and French versions are available [31]. The German version was translated and back-translated by experts.

c) Others factors:

- Social relationship Whoqol-bref (3 items) and environmental Whoqol-bref (8 items), subscales of the Whoqol-bref tool (26 items) [36] were also rated on a five point scale; the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.64 and 0.77, respectively.

- Sociodemographic and general health characteristics: sex, age, nationality (Luxembourger/other nationality), 12th grade diploma (general/professional-technical), level of education of the parents (below/12th grade and above), their professional status (manual worker/senior officer), and general health with a selfadministrated five point scale (dissatisfied to very satisfied).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All scores were calculated so that a higher score represented a better level. At time points 1 and 2, the samples were compared for each variable by means of Chi-square test and Student’s t-test. The links between the psychological Whoqol-bref and the AES scores, and the other variables were explored by one way anova tests and correlations. We fitted a linear mixed model to the overall data set with the psychological Whoqol-bref score as the dependent variable. Inter-subject variances were supposed to be equal at time 1 and time 2. Among candidate socio-demographic variables, we selected those with a significant simple effect at the 5% level. We were particularly interested in the effects of time, general health, AES, social relationships and environmental quality of life, and changes over two times of those effects which were explored by adding interaction terms.

3. RESULTS

The mean age of the 321 respondents (participation rate, 33%) was about 21 years; Luxembourg students enter university one year later than most of their European counterparts. Young women predominated (57.3% vs 46.3% non-respondents) (Table 1). But more young women participated, even though females do not out number males overall at our university.

Once the consent was signed, each student’s could be identified through his personal number. Thanks the base enrolment of the university and the personal number we could check his or her sociodemographic characteristics indicating, among other for each student, if he/she was not redoubling.

Table 1. Comparison of sociodemographic characteristics between non-respondents and respondents.

p1: Significance level of Chi square test: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

This over-representation, corresponding to the wellknown preponderance of females in surveys, has been observed elsewhere. Non-respondents are particularly likely to be men, who tend to be low participants in surveys anyway because they don’t like to do so or to give personal opinions [39,40].

More responders came from the Law & Finance and Social Sciences faculties, at the second time point. Satisfaction with the AES (74.2 vs 65.6) declined. No signifycant differences were observed for the psychological, social relationships and environmental Whoqol-bref scores, which were relatively stable between time points 1 and 2. Similarly for nationality and education level, most students were Luxembourgers and their diploma was generally 12th grade.

The parental level of education was mainly under 12th grade diploma (63.4% of fathers, 68.8% of mothers) and their professional status was mainly “manual worker” (62.4% and 76.3%, respectively). More than 83.6% were “satisfied or very satisfied” with their general health state (Table 2).

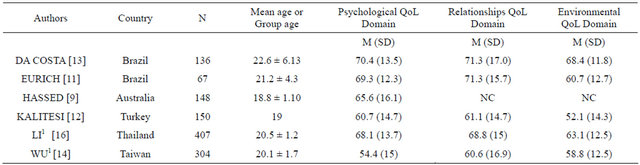

At the two time points, the students in our study had higher psychological, social relationships and environmental QoL scores than those found in studies cited in the Introduction. For the psychological QoL, Luxembourg students had a higher score than social sciences students from Brazil (72.3 vs 70.4) [13]. With regard to the social relationship QoL, the students from Luxembourg (Table 3) had a similar mean to that reported among students from Brazil (71.9 vs 71.3) [11,13]. For the environmental QoL, the students from Luxembourg had a higher level than students from Brazil (72.5 vs 68.4) [13].

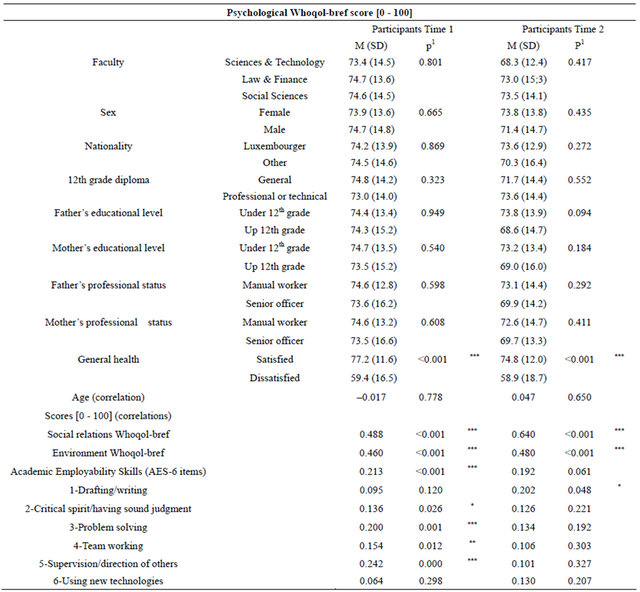

The psychological Whoqol-bref score was positively correlated, only at time 1, with AES score, and at both time points, with the environmental and social relations QoL scores and the general health (Table 4).

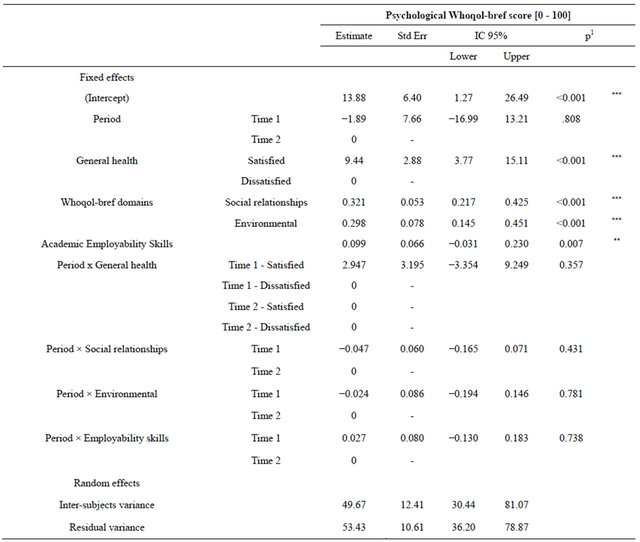

Among the socioeconomic characteristics of the participants, no effect reached the 0.05 significance level. Fixed effects were observed between a higher psychological Whoqol-bref and general health (difference satisfied-dissatisfied 9.44), AES (slope 0.099), social relationships QoL (0.321), and environmental QoL (0.298). No interaction with time effects was significant, which indicates that the effects remain stable with time. The inter-subjects variance was almost half of the overall variance, leading to a high correlation estimate between student’s psychological QoL measures (49.7) (Table 5).

4. DISCUSSION

At the two time points, our study shows that the psychological, social relationship and environmental QoL dimensions were relatively stable and their levels were

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics, psychological Whoqol-bref, academic employability skills, and other variables. M2 = Mean; SD Standard Deviation.

p1: Significance level of the Fisher exact test, except for the continuous variable age, for which the Student’s t test was used *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

higher than those in studies cited in the Introduction. No links between psychological QoL and sociodemographic characteristics were observed; this is interesting because those factors are major contributors to social inequality in mental health [41].

By focusing on the period between the beginning and the end of the first year, this study improves our understanding of the links between the psychological QoL of newly registered students and their perceived general health, social relationships and environmental QoL (living conditions and lifestyles on campus). The higher the psychological QoL, the better these associated factors were perceived to be. In contrast, after seven months, the perceived acquisition of AES had declined.

In a recent study among only social sciences students from three European universities, the psychological QoL was associated with the acquisition of skills and knowledge that increase employability among students from the faculties with vocational/applied/professional courses in Luxembourg and Romania, but not their academically (mainly general courses) orientated Belgian counterparts [42]. Our interpretation suggests that the individual projects of students who enrol into academic courses are probably not well defined. The Canadian research from

Table 3. WHOQoL-bref domains among students: results from the literature.

1: Scores of this study were on a 0 - 20 scale, we transformed them to a 0 - 100 scale according to the calculation of the Whoqol: (domain-4)*(100/16).

Table 4. Relationships between psychological Whoqol-bref, sociodemographics characteristics, and academic employability skills, separately for each time (bivariate tests).

p1: Significance level of One way Anova test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 or Significance level of no correlation test.

Table 5. Relationships between psychological Whoqol-bref, academic employability skills, and other variables (multiple regression).

1: Significance level of type III tests: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

which we have adapted the AES scale highlights some interesting points when it compares the AES of students and post-graduates. It observed that social sciences graduates who had worked for at least two years had higher level skills [31].

Indeed, the students who were more confident in their capacity to use their newly acquired competencies and in their ability to solve the difficulties were the ones who felt able to project themselves into a professional future. The feeling of personal effectiveness is a major determinant of believing they can obtain a potential occupation [43], and the motivation to go on [44].

Young adulthood has great potential for personal growth and for failure. Individuals who receive proper encouragement and reinforcement through personal exploration will emerge from this stage with a strong sense of self and a feeling of independence and control. Those who remain unsure of their beliefs and desires will be insecure and confused about themselves and the future [20]. Reflection about this project could be potentially beneficial to professionals of the university in order to provide appropriate advice, consultation, or intervention specifically to this age group. Some interventions should focus on helping students to prepare for work and acquire occupational requirements. Attention should be given to prevention, by, for example, offering students interventions aimed at reinforcing internal resources and empowerment.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations should be discussed. First, the surveys were conducted among newly registered volunteers and the results cannot be generalized. However, although the sample is small, the rate of 33% is in accord with the 27% in the literature [45]. Findings therefore cannot be extrapolated to wider participants, thereby limiting interpretation of the data. Second, voluntary completion of the web-based self-administered questionnaire might lead to bias in terms of participation and responses to questions [46]. Third, the web-format Whoqol-bref is considered equivalent to the paper version [45], and the quality of the completed questionnaires was high.

4.2. Recommendations

With regard to the development of a European Higher Educational Area, our SQALES project permits evaluation of the impact of the new university missions and follow-up of new indicators in order to ensure that students’ needs for help are being met appropriately, i.e. by supporting them in acquiring skills, increasing well-being, and generally improving the environment on the campus and the relationships that exist there. The decision to focus on newly registered first-year undergraduates was of paramount importance as it enabled us to identify some challenges and difficulties related to transition periods. Every year, too many students drop out and leave university without a diploma.

If the university could maintain indicators of performance at appropriate levels, health promotion involving empowerment strategies can be used to develop activities and create further opportunities. Workshops to develop empowerment strategies, discussion groups, student welfare initiatives, individual help, and information provided on websites, leaflets and hotlines can increase the capacity of young people to cope with anxiety and manage their lives. Discussion groups are a well-established tool in workplace health promotion, facilitating participation and empowerment. Those that gave a voice to the students proved to be useful in encouraging participation in university-based health promotion. It is important to be able to gauge the difficulties of adapting to a university environment without losing sight of the complexities young adults face in dealing with academic problems and the emotional and relationship issues that come into play during this period of adolescence when youth is extended [47].

Additional data should help in the design of intervenetions to improve support services for students. This is an ethical issue, because we are responsible for the young people we will be asking to address the socio-economic challenges posed by the current crisis. The beginning of university life is an important time of change for young adults in terms of identity development driven by the interactions between individual bio-psychological characteristics and the demands of society, and in terms of health-related behaviour [48,49].

A campus is a natural assistance setting for health programmes among students and for developing workshops about improving the social environment, and enhancing the acquisition of skills in writing/drafting, critical thinking, problem solving, working effectively with others, leading others, and using new technology. In many universities, tutoring groups have been created to help students manage their university work or to learn work methods. Participation reduces perceived stress and contributes support and advice favouring interaction in pairs. Information then plays a very important role in the promotion of autonomy, self-respect and development of the ability to take action. It increases the participation of students in their training and improves their performance [20]. We would also create work groups through which students can establish contact with the employment market by organizing meetings with professionals, and attend sessions on job-seeking techniques.

New relations with lecturers. Health promotion also supports positive relations between students and lecturers who would like to use more empowerment-based teaching methods [43]. Efforts should be devoted to improveing supervision of teaching and encouraging a positive educational approach. Professors who are cordial, open, and able to joke and laugh with their students build confidence and facilitate communication and social relationships.

Student associations improve the social environment by implementing cultural projects, and organizing festivals, sporting competitions between universities, and conferences. Support activities help new students look for an internship or complete a professional project. Associations encourage the development of student life through networks of similar bodies. This will require students to participate in training days and the management of associations. Promoting student empowerment within the decision-making authorities on the campuses cannot be improvised; student associations must learn it.

5. CONCLUSION

The SQALES project provides knowledge that can serve as a foundation for guidance and advice for those about to discover the world of work-missions recommended by the Bologna process and the European Higher Education Area [35]. The SQALES protocol and this instrument can provide valuable information for universities that conduct similar studies in the future. Empowerment of students is a necessary part of university-based health promotion. Special emphasis should be given to lowering barriers against participation. Implementation of proposed actions is highly dependent on the establishment of effective health promotion support structures, such as a steering committee, and the commitment of university management.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all the volunteer students of the University of Luxembourg. The project “Students Quality of Live and Employability Skills “SQALES” obtain a financial support by the University of Luxembourg.

REFERENCES

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (2010) How are you? Quality of Live in Europe. http://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/focusform.htm

- WHO Europe (2008) European pact for mental health and well-being. EU High-level Conference on Together for Mental Health and Wellbeing, Brussels, 12-13 June 2008. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_determinants/life_style/mental/mental_health_fr.htm

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E. and Gollust, S.E. (2007) Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care, 45, 594-601. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4c1

- Craig, T.K.J. (2004) Students’ health needs: Problems and responses. Psychiatric Bulletin, 28, 69-70. doi:10.1192/pb.28.2.69-a

- WHOQOL Group (1994) The development of the World Health Organisation’s quality of life assessment instrument (the WHOQOL). In: Orley, J. and Kuyken, W., Eds., Quality of Life Assessment: International Perspectives, Springer, Berlin. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79123-9

- Skevington, S.M., Sartorius, N., Amir, M. and the WHOQOL Group (2004) Developing methods for assessing quality of life in different cultural settings: The history of the WHOQOL instruments. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 1-8. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0700-5

- Skevington, S.M. (2010) Qualities of life, educational level and human development: An international investigation of health. Social Psychiatry and Epidemiology, 45, 999-1009. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0138-x

- Bowden, A. and Fox-Rushby, J. (2003) A systematic and critical review of the process of translation and adaptation of generic health related quality of life measures in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and South America. Social Sciences and Medicine, 57, 1289-1306. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00503-8

- Hassed, C., de Lisle, S., Sullivan, G. and Pier, C. (2009) Enhancing the health of medical students: Outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Advance Health Sciences Education Theory Practice, 14, 387-398. doi:10.1007/s10459-008-9125-3

- Saupe, R.S., Nietche, E.A., Cestari, M.E., Giorgi, M.D. and Krahl, M. (2004) Quality of life of nursing students. Revista Latino-Americano Enfermagem, 12, 636-642.

- Eurich, R.B. and Kluthcovsky, A.GC. (2008) Evaluation of quality of life of undergraduate nursing students from first and fourth years: The influence of sociodemographic variables. Revista Psiquatria do Rio Grande do Sul, 30, 211-220.

- Kalitesi, Y., Destek, S., Ag Ve Yalnizlik, S. and Iliskiler, A. (2004) Relationships between quality of life, perceived social support, social network, and loneliness in a Turkish sample. Yeni Symposium, 42, 20-27.

- da Costa, C.C., de Bastiani, M., Geyer, J.G., Calvetti, P.U., Muller, M.C. and Andreoli de Maoraes, A.L. (2008) Qualidade de vida e bem-estar espiritual em universitarios de Psicologia. Psicologia Estudo, 13, 249-255. doi:10.1590/S1413-73722008000200007

- Wu, C.H. and Yao, G. (2007) Examining the relationship between global and domain measures of quality of life by three factor structure models. Social Indicators Research, 840, 189-202. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-9082-2

- Chen, K.H., Wu, C.H. and Yao, G. (2006) Applicability of the WHOQoL-BREF on early adolescence. Social Indicators Research, 79, 215-234. doi:10.1007/s11205-005-0211-0

- Li, K., Kay, N.S. and Nokkaew, N. (2009) The performance of the World Health Organization’s WHOQOLBREF in assessing the quality of life of Thai College Students. Social Indicators Research, 90, 489-501. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9272-1

- Yao, G., Wu, C.H. and Yang, C.T. (2008) Examining the content validity of the WHOQOL-BREF from respondents’ perspective by quantitative methods. Social Indicators Research, 85, 483-498. doi:10.1007/s11205-007-9112-8

- Zimmermann, J., Eisemann, M.R. and Fleck, M. (2008) Is parental rearing an associated factor of quality of life in adulthood? Quality Life Research, 17, 249-255. doi:10.1007/s11136-007-9261-x

- Adlaf, E.M., Gliksman, L., Demers, A. and Newton-Taylor, B. (2001). The prevalence of elevated psychological distress among Canadian undergraduates: findings from the 1998 Canadian Campus Survey. Journal American College Health, 50, 67-72. doi:10.1080/07448480109596009

- Amara., M.E. and Baumann, M. (2012) University Europe. Identity of student vis-a-vis the employability. Ed. Academia L’Harmattan, collection INSIDE, Louvain La Neuve, 317.

- Roberts, S., Golding, J., Towell, T., Reid, S. and Woodford, S. (2000) Mental and physical health in students: The role of economic circumstances. British Journal Health Psychology, 5, 289-297. doi:10.1348/135910700168928

- Özdemir, U. and Tuncay, T. (2008) Correlates of lonelyness among university students. Child Adolescent Psychiatry Mental Health, 2, 29-39. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-2-29

- Boujut, E., Koleck, M., Bruchon-Schweitzer, M. and Bourgeois, M.L. (2009) Mental health among students: A study among a cohort of Frenchmen. Annales MedicoPsychologiques, 167, 662-668. doi:10.1016/j.amp.2008.05.020

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E. and Gollust, S.E. (2007) Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care, 45, 594-601. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e31803bb4c1

- Patel, V., Flisher, A.J., Hetrick and S., McGorry, P. (2007) Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. Lancet, 369, 1302-1313. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7

- Roberts, R., Golding, J., Towell, T. and Weinreb, I. (1999) The effects of economic circumstances on British students’ mental and physical health. Journal American College Health, 48, 103-109. doi:10.1080/07448489909595681

- Stecker, T. (2004) Well-being in an academic environment. Medical Education, 38, 465-478. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2929.2004.01812.x

- Verger, P., Guagliardo, V., Gilbert, F., Rouillon, F. and Kovess-Masfety, V. (2010) Psychiatric disorders in students in six French universities: 12-month prevalence, co morbidity, impairment and help-seeking. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 189-199. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0055-z

- El Ansari, W. and Stock, C. (2010) Is the health and wellbeing of university students associated with their academic performance? Cross sectional findings from the United Kingdom. International Journal of Environmental and Research Public Health, 7, 509-527. doi:10.3390/ijerph7020509

- Tsouros, A.D., Dowding, G., Thompson, J. and Dooris, M. (1998) Health promoting universities concept, experience and framework for action. World Health Organization, Copenhagen.

- Lin, Z., Sweet, R., Anisef, P. and Schuetze, H. (2000) Consequences and policy implications for university students who have chosen liberal or vocational education. Labour market outcomes and employability skills. Human Resources Development Canada. http://www.rhdsc.gc.ca/fr/sm/ps/rhdc/rpc/publications/recherche/2000-000184/page00.shtml

- Rothwell, A., Herbert, I. and Rothwell, F. (2007) Selfperceived employability: Construction and initial validation of a scale for university students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73, 1-12. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2007.12.001

- Pelt, V. and Baumann, M. (2010) How universities can assess employability skills? In: Bargel, T., et al., Ed., The Bachelor: Changes in Performance and Quality of Studying? Empirical Evidence in International Comparison, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, 66-82.

- FRERET (2010) Studying in a changing university: The works of the UNI 21 research group. http://www.freref.eu/index.php?lang=en

- European Commission (2009) The Bologna Process 2020: Towards the European higher education area. Leuven/ Louvain-La-Neuve (Belgium). http://ec.europa.eu/education/higher-education/doc1290_en.htm

- Hawthorne, G., Herrman, H. and Murphy, B. (2006) Interpreting the WHOQOL-BREF: preliminary population norms and effect sizes. Social Indicators Research, 77, 37-59. doi:10.1007/s11205-005-5552-1

- Angermeyer, M.C., Kilian, R. and Matschinger, H. (2000) WHOQOL-100 und WHOQOL-BREF. Handbuch fur die deutschsprachige version der WHO instrumente zur erfassung von lebensqualität. HOGREFE, Göttingen.

- Leplège, A., Réveillère, C., Ecosse, E., Caria, A. and Rivière, H. (2000) Propriétés psychométriques d’un nouvel instrument d’évaluation de la qualité de vie, le WHOQOL-26, à partir d’une population de malades neuromusculaires. Encéphale, 26, 13-22.

- Dunn, K.M., Jordan, K., Lacey, R.J., Shapley, M. and Jinks, C. (2004) Patterns of consent in epidemiologic research: Evidence from over 25,000 respondents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159, 1087-1094. doi:10.1093/aje/kwh141

- Van Loon, A.J.M., Tijhuis, M., Picavet, H.S.J., Surtees, P.G. and Ormel, J. (2003) Survey non-response in the Netherlands: Effects on prevalence estimates and associations. Annals of Epidemiology, 13, 105-110. doi:10.1016/S1047-2797(02)00257-0

- Aïach, P. and Baumann, M. (2010) Prevention and reduction of the social inequalities of health: A difficult conciliation. Global Health Promotion, 17, 95-98. doi:10.1177/1757975909356639

- Baumann, M., Ionescu, I. and Chau, N. (2011) Psychological quality of life and its association with academic employability skills among students from three European faculties. BMC Psychiatry, 11, 63-72. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-63

- Colquitt, J.A. and Le Pine, J.A. (2000) Toward and integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678-707. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.678

- Urdan, T. C. and Maehr, M. L. (1995) Beyond a two-goal theory of motivation and achievement: A case for social goals. Review of Educational Research, 65, 213-243.

- Chen, W.C., Wang, J.D., Hwang, J.S., Chen, C.C., Wu, C.H. and Yao, G. (2009) Can the web-form WHOQOLBREF be an alternative to the paper-form? Social Indicators Research, 94, 97-114. doi:10.1007/s11205-008-9355-z

- Brener, N.D., Kann, L., Kinchen, S.A., Grunbaum, J.A., Whalen, L., Eaton, D., Hawkins, J. and Ross, J.G. (2004) Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recommendation and Report, 24, 1-13.

- Meier, S., Stocks, C. and Kramer, A. (2006) The contribution of health discussion groups with students to campus health promotion. Health Promotion International, 22, 28-36. doi:10.1093/heapro/dal041

- Schwarzer, R. (2001) Stress, resources, and proactive coping. Applied Psychology, 50, 400-407.

- Luszczynska, A. and Schwarzer, R. (2003) Planning and self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of breast self-examination: A longitudinal study on self-regulatory cognitions. Psychology Health, 18, 93-108. doi:10.1080/0887044021000019358