Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.07 No.12(2016), Article ID:70136,21 pages

10.4236/jmp.2016.712139

Electromagnetic-Energy Flow in Anisotropic Metamaterials: The Proper Choice of Poynting’s Vector

Carlos Prieto-López, Rubén G. Barrera

Instituto de Física, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 22 June 2016; accepted 23 August 2016; published 26 August 2016

ABSTRACT

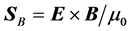

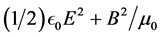

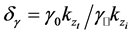

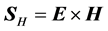

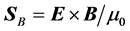

We study the controversy about the proper determination of the electromagnetic energy-flux field in anisotropic materials, which has been revived due to the relatively recent experiments on negative refraction in metamaterials. Rather than analyzing energy-balance arguments, we use a pragmatic approach inspired by geometrical optics, and compare the predictions on angles of refraction at a flat interface of two possible choices on the energy flux:  and

and . We carry out this comparison for a monochromatic Gaussian beam propagating in an anisotropic non- dissipative anisotropic metamaterial, in which the spatial localization of the electromagnetic field allows a more natural assignment of directions, in contrast to the usual study of plane waves. We compare our approach with the formalism of geometrical optics, which we generalize and analyze numerically the consequences of either choice.

. We carry out this comparison for a monochromatic Gaussian beam propagating in an anisotropic non- dissipative anisotropic metamaterial, in which the spatial localization of the electromagnetic field allows a more natural assignment of directions, in contrast to the usual study of plane waves. We compare our approach with the formalism of geometrical optics, which we generalize and analyze numerically the consequences of either choice.

Keywords:

Poynting Vector, Eikonal, Electromagnetic-Energy Flux, Anisotropic Metamaterials, Geometrical Optics

1. Introduction

The location of electromagnetic energy is an elusive subject that has been under discussion since the beginning of electrodynamics [1] . Even in the case of electrostatics, one can write at least two different expressions for the energy density of a fixed distribution of charges ( [2] , p. 21). In one of them, the energy density is proportional to the charge density itself, thus located wherever the charge density is different from zero; in the other one, it is proportional to the square of the electric field generated by the charge distribution, thus located in all space, both inside and outside the volume occupied by the charge distribution. On the side of electrodynamics, the am- biguity is even greater. The energy-balance equation in vacuum involves the time derivative of energy density of the electromagnetic field, given in terms of the squares of the electric and magnetic fields and the divergence of the Poynting vector; this vector is defined as proportional to the cross product of the electric and magnetic field and it gives the magnitude and direction of the energy flux ( [3] , sec. 61). Since the balance equation for energy conservation requires only the divergence of the Poynting vector, this vector field is not uniquely defined and it is always possible to add to it an arbitrary vector field with zero divergence. Furthermore, it is also possible to redefine both the Poynting vector and the expression for the energy density, in such a way as to fulfill correctly the balance equation [4] - [10] ( [11] , ch. 27.5). This freedom leads to an unsurmountable ambiguity about the location of electromagnetic energy and direction of the electromagnetic-energy flux. Nevertheless, it has been argued that the law of conservation of energy does not stand by itself, that there are also conservation laws for linear and angular momentum, and they have to be examined together. For example, in vacuum, the relationship between the Poynting vector (energy-flux field) and the electromagnetic linear-momentum density, together with the conservation of angular momentum, restricts the freedom of choice for the mathematical expression of the Poynting vector, and it has been even claimed that these restrictions remove the ambiguity altogether [12] [13] .

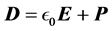

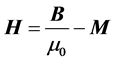

The problem of the location of energy and the correct expression for the energy flux in the presence of materials acquires additional intricate subtleties related to the description of the energy-exchange mechanism between fields and matter [14] [15] . First, let us recall that the formulation of macroscopic electromagnetic phenomena is commonly achieved by the introduction, besides the macroscopic electric field  and magnetic induction field

and magnetic induction field , of two other fields: the displacement field

, of two other fields: the displacement field  and the magnetic intensity

and the magnetic intensity , or, equi- valently, the polarization and magnetization fields:

, or, equi- valently, the polarization and magnetization fields:  and

and . In relation to the physical interpretation of these fields, a problem arises about an issue that has been discussed for more than a century: how to establish if

. In relation to the physical interpretation of these fields, a problem arises about an issue that has been discussed for more than a century: how to establish if  or

or  represents the “real” magnetic field, that is, the one that comes after an averaging process of the magnetic field generated by the microscopic components of a given material. There are even carefully argued assertions by W. Thomson that the magnetic field inside the material is not even properly defined ( [16] and references therein). The choice in this issue has definite consequences in the energy-balance equation―also known as Poynting’s theorem―when extended to the case where materials are present. As we will discuss briefly in Section 2, this is specially important if we want to separate the total energy density into a component stored in the fields and a component stored or dissipated within the material.

represents the “real” magnetic field, that is, the one that comes after an averaging process of the magnetic field generated by the microscopic components of a given material. There are even carefully argued assertions by W. Thomson that the magnetic field inside the material is not even properly defined ( [16] and references therein). The choice in this issue has definite consequences in the energy-balance equation―also known as Poynting’s theorem―when extended to the case where materials are present. As we will discuss briefly in Section 2, this is specially important if we want to separate the total energy density into a component stored in the fields and a component stored or dissipated within the material.

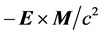

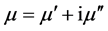

Furthermore, in the more general case when the electromagnetic response is linear but not instantaneous, it necessarily depends on frequency and it is dissipative. In this case it is not possible to separate the energy density into material, field and absorption contributions. But even in low-dissipation frequency bands, the correct expression for the Poynting vector (energy flux) depends on the explicit form of the energy-balance equation. Also, in relation to the freedom of choice of Poynting’s vector and the restrictions imposed by other conservation laws: linear and angular momentum, one has to recall that unlike in vacuum, in the presence of material media the relation between Poyting’s vector and the linear-momentum density of the electromagnetic field is still controversial [17] . There have been at least two proposals for the correct mathematical expression for the linear-momentum density: one given originally by M. Abraham ( ) [18] and the other one given originally by H. Minkowski (

) [18] and the other one given originally by H. Minkowski ( ) [19] , being these two choices the source of a persisting debate about either their correctness or their physical interpretation ( [20] , and references therein). There are also more drastic claims assuring that the macroscopic electromagnetic field within a material is actually a non-physical quantity, and that real measurement devices do not really measure the energy flux given by the Poynting vector [21] .

) [19] , being these two choices the source of a persisting debate about either their correctness or their physical interpretation ( [20] , and references therein). There are also more drastic claims assuring that the macroscopic electromagnetic field within a material is actually a non-physical quantity, and that real measurement devices do not really measure the energy flux given by the Poynting vector [21] .

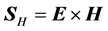

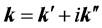

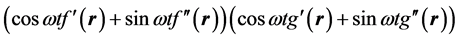

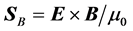

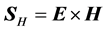

Here we will not analyze all different aspects of these longstanding and sometimes subtle questions. We will rather concentrate only in two different proposals for the mathematical expression of the Poynting vector , whose choice has created controversy even in recent years [22] - [30] . One given by

, whose choice has created controversy even in recent years [22] - [30] . One given by , which is the commonly used in literature and the one that appears in most textbooks and the other by

, which is the commonly used in literature and the one that appears in most textbooks and the other by , where we use SI units and

, where we use SI units and

In this paper, rather than discussing the energetic balance in the material, we propose to look at the con- troversy from the perspective of geometrical optics in an extremely pragmatic approach, based on the fact that the energy flux is not only used to calculate energy balances, but also to quantify light intensity and its direction of propagation. To watch the refraction of a laser beam on a transparent prism is a very common and intuitive experience, in which one could very naturally speak about the “location” of the energy and the direction and “bending” of the energy flux. In contrast, in the idealized case of a plane wave the energy is on the average evenly distributed over all space, and it is therefore unlocalized, making it impossible to use such “intuitive” arguments as above.

For the two fields

Having all this in mind, we tackle the problem by constructing a “ray” of light in order to see how does it refract at an interface between vacuum and an anisotropic metamaterial. One can find different definitions of ray in geometrical optics, for example, one, as a line in the direction of the gradient of the eikonal [3] [39] , another, simply as a continuous line along the direction of the energy flow [40] , and still another one that defines ray merely as a beam [41] . Here we will adopt a rather intuitive picture of a ray by regarding it as a very narrow beam. Then we use continuum electrodynamics to calculate the spatial location of the reflected and refracted beams, together with the energy flow according to the two proposals in question. Then we compare―among other things―their directions with the direction of the beam.

The structure of the paper is as follows: in Section 2 we compare, for each energy-flux proposal, possible interpretations of the energy-balance equations and the terms involved in them; then in Section 3 we present a brief introduction of the electromagnetic properties of anisotropic uniaxial metamaterials with emphasis on the refraction of plane waves at a flat interface; we later state in Section 4 some basic properties of 2D mono- chromatic electromagnetic fields, on which we build our analysis, and make a comparison with the formalism of geometrical optics, which we extend in Section 5. In Section 5.1 we particularize the results and concepts of these two previous sections to a Gaussian beam; we study some its main characteristics, and sketch how to calculate its refraction, to finally display and analyze the corresponding results of the numerical simulations. Section 6 is devoted to our conclusions.

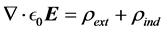

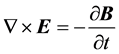

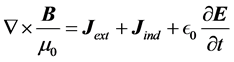

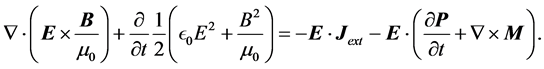

2. Poynting’s Theorem

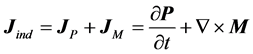

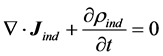

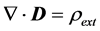

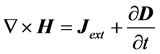

In this section we present briefly the energy-balance equations for the two energy-flux proposals to establish the differences in interpretation of the terms appearing in them. We start with the macroscopic Maxwell’s equations and regard the presence of the material as given by the charge and current densities induced by an external electromagnetic field produced by external sources. Maxwell’s equations, in SI units, can be then written as

where

where 1)

By substituting Equation (5) into Ampère-Maxwell’s law (4) and using the induced charge conservation (6), one can write Equations (1) and (4) as

which together with Equations (2) and (3) form the complete set of the four macroscopic Maxwell’s equations. Here

is called the displacement field, while

is called the magnetic intensity or simply the H field.

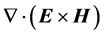

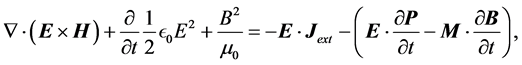

If one now calculates

that takes the mathematical form of a conservation law for the energy, and one can interpret

Following the same procedure as above, one can also write the following equation:

In this expression one identifies

We will not discuss further the physical interpretation of the terms that appear in the energy-conservation laws given in Equations (11) and (12); we now rather construct the conceptual and mathematical framework to analyze the energy transport in the refraction of a beam of light at the interface between vacuum and an anisotropic metamaterial. The advantage of dealing with anisotropic metamaterials rather than with crystals, is that in crystals the anisotropy of the electromagnetic response is fixed by the crystalline structure and cannot be changed, while in metamaterials this degree of anisotropy, as well as the signs of the response, can be tailored through the fabrication process.

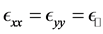

3. Uniaxial Metamaterials

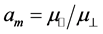

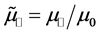

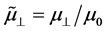

As discussed above, we will be dealing with anisotropic uniaxial metamaterials. These are characterized by electric and magnetic response tensors

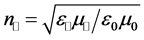

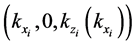

We will now introduce notation and summarize some of the properties that we will use in this paper; their derivation can be found, for example, in [42] . First we recall that an uniaxial metamaterial sustains two elec- tromagnetic plane-wave modes, which we will call e and m, and refer to them generically as

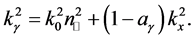

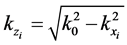

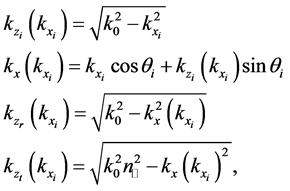

The dispersion relations of these modes can be put in terms of

Note that

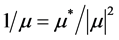

Finally, it is important to say that, in this medium, the field

so both vectors will only be parallel when there is no anisotropy of the corresponding mode (

Refraction of Plane Waves

Let us consider a plane interface between vacuum and the uniaxial metamaterial, set this interface perpendicular to the optical axis of the metamaterial and fix the z-axis along this direction. Then assume that a plane wave, with its wavevector in the xz plane, impinges from vacuum into the metamaterial. One can immediately see that if the incident wave is p-polarized (

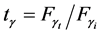

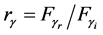

Now we look at the reflection and transmission of plane waves in the presence of uniaxial metamaterials, defined as

where

In terms of these definitions and basic concepts, we now summarize some interesting features of the refraction of plane waves on uniaxial metamaterials. A derivation of all these results can be found in [42]

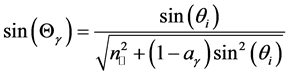

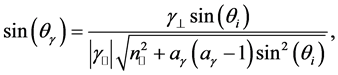

1) The angle

2) The angle

and we call this the refraction angle.

3) The refraction of

of

4) The sign of refraction is determined by the sign of

5) The refraction angle, as a function of the incidence angle, is an increasing function if

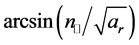

6) Whenever

7) The critical angle has an inverse behavior in the case

8) There exist critical angles for both polarizations.

9) There is low variation of the refraction angle for

10) In the particular case when

Note especially, on relation with negative refraction, some less restrictive features of these materials due to their anisotropy, for example, the sign of the projection of

With respect to point 3, it is important to note that this refraction problem has a mathematical ambiguity arising from the fact that the dispersion relation (13) is quadratic, and thus two possibilities for

4. 2D Monochromatic Fields

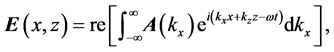

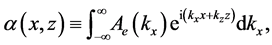

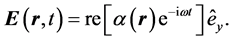

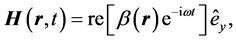

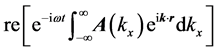

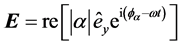

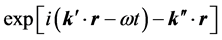

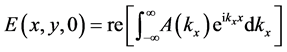

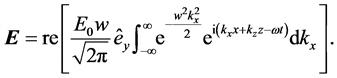

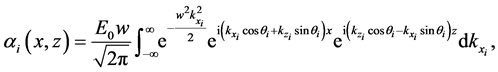

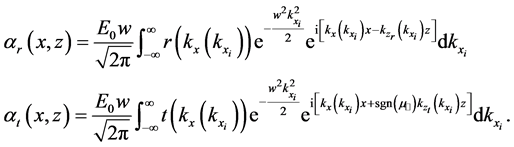

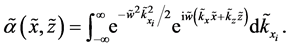

In this work we will be dealing, for simplicity, with the refraction of monochromatic two-dimensional beams, that nevertheless keep most of the physics behind the phenomenon of refraction of actual three-dimensional beams. We consider first an arbitrary two-dimensional monochromatic electric field, defined as a superposition of plane waves in the xz plane,

where re denotes real part. In a given medium, this will be a solution to Maxwell's equations if

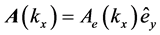

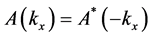

We can view this superposition as a series of plane waves traveling along different directions and with different amplitudes, these determined by the function

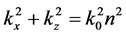

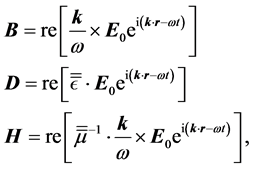

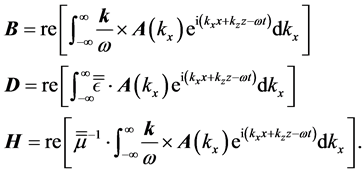

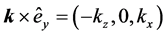

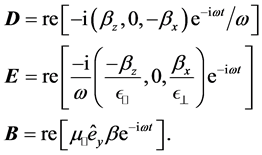

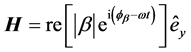

Recalling now that the magnetic, displacement, and

of a plane wave of wavevector

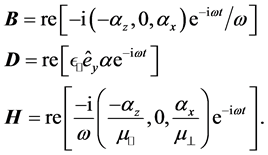

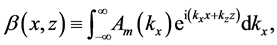

it is immediate to write the corresponding monochromatic fields associated to the electric field given in Equation (18), as

For s-polarization, the amplitudes

thus in terms of

Note that if we denote

and the same is valid for

For p polarization, one can write an expression for the

where

with the following corresponding expressions for the displacement, electric and magnetic fields,

It is important to note that the linear superposition of plane waves, as the one given in Equation (18) can be

also written as

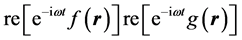

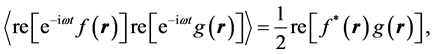

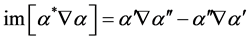

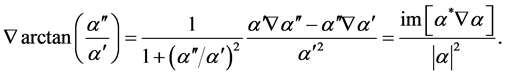

a factor that is a function only of position. Since in the calculation of the energy densities and energy flux we will be dealing with bilinear products of the form

where we have used

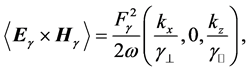

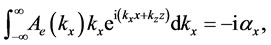

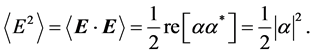

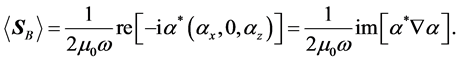

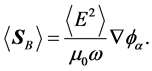

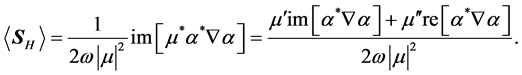

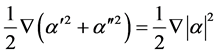

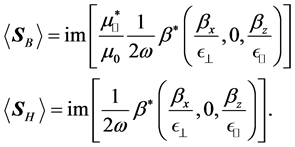

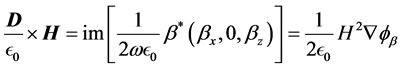

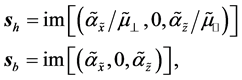

For example, using Equations (22) and (28), the time average of

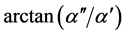

Also, from Equations (22) and (24) one can easily calculate

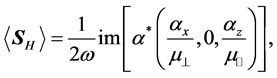

Note that this result is general and does not depend on the constitutive relations. On the other hand, for

which clearly differs in direction from

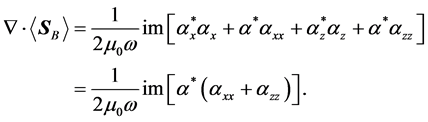

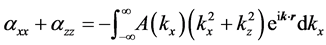

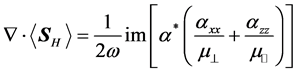

Finally, regarding to the energetic consequences of the choice of energy flux, note that, taking the divergence of

Since

has the value

which, in view of the dispersion relation (13), and following the same reasoning as before with

5. Geometrical Optics and Light Beams

As we already mentioned in the introduction and in the section concerning the refraction of plane waves, the energy-flux vector (Poynting’s vector) is used, besides the calculation of electromagnetic-energy transport, in determining the “detectable” direction of refraction of plane waves, over the direction given by the angle of refraction of the wavevector. Although in many cases they do coincide, their difference in direction is specially critical in the phenomenon of negative refraction. In our pragmatic approach we will look at the refraction of rays―defined as narrow beams―and then calculate the two expressions for the energy flux:

The first question is how to define the location of the beam in order to visualize it. The first idea could be perhaps to identify it with the transmitted energy flux and visualize it by plotting the transmittance, which is what one usually associates as the measurable quantity in optics experiments. The problem with such definition is that the value of the transmittance depends on the definition of the energy flux, which would lead us to a circular argument. Also, let us recall that the transmittance is proportional to the energy flux perpendicular to the interface, as if the detection of the transmitted power would be accomplished only along the perpendicular direction and not along the direction of the beam. Thus, we choose to look instead at the energy density, which in the absence of dissipation is proportional to

In the search of a criterion to determine how a monochromatic field refracts, one may require to define the direction of propagation of the field. At this respect, we derived the following result which we find interesting, and, to our knowledge, unnoticed yet. Let us start considering the simplest case of an isotropic, homogeneous, non-magnetic medium in which

We recognize in

Since the electric field in Equation (22) can be also written as

homogeneous, isotropic, non-magnetic medium, the time average of the field

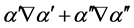

Going a little bit further, note that the dependence on the material in the expressions for the electric field

This same result does not hold for all materials while regarding the energy flux as given by

The real part of

can write

One can see that the first term in the right hand side points along the direction of the gradient of phase of the electric field as in the case of a homogeneous nonmagnetic material, but now, due to absorption, the field

Nevertheless, the very general result that for any monochromatic electromagnetic field and for any material the direction of

The analogous result for p polarized light might not be as obvious, but is also quite interesting. Using the expressions for the fields given in Equations (25) and (27) one can write,

Without magnetic absorption, both fields are parallel, even in anisotropic media. Moreover, none of them has the property of pointing in the direction of maximum change of the phase of

where we have written

be mathematically clarified by the fact that Maxwell's equations in regions free of external sources together with the constitutive relations are invariant under the interchange of

Gaussian Beam

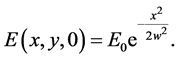

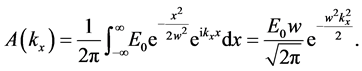

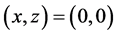

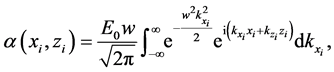

We now use the results for 2D monochromatic fields to construct a localized beam. We start by regarding an s-polarized beam localized along the z-axis, and impose a boundary condition over the magnitude E of the electric field at

From Equation (22) we get that

tified as the spatial Fourier transform of

Thus, the electric field in any point at any time is given by

This is a 2D Gaussian beam, confined in the x direction and extended along the z direction. Regarding its composition as a superposition of plane waves, note that the plane wave corresponding to wavevector

We will be plotting

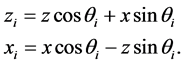

We are interested in the refraction of an incident beam from vacuum to an anisotropic metamaterial, but with an arbitrary angle of incidence

and the relationship between these two coordinate systems is given by

Replacing these rotated variables in Equation (43) we get the following expression for the incident beam on the

where the axis of the beam lies along the line

are related through the dispersion relation―and amplitudes given by

Note that the center of the beam remains in the same position.

Given the incident field in Equation (45) and setting the location of the uniaxial metamaterial in

To this purpose, we follow the next steps to refract and reflect a given mode of the incident beam:

1) For a given mode-characterized in the integral by

2) From the resultant wave vector

rotating it as required in Equation (44).

3) Calculate the z-component of this mode by using the dispersion relation in the corresponding medium (vacuum or metamaterial), and assigning

a) a negative sign for the reflected mode.

b) the sign of

4) Multiply the amplitude of this mode by the transmission or reflection coefficient in Equation (15), as a function of the parallel (x-component) of the wavevector.

To summarize this, we have, in terms of

the expressions for the reflected and transmitted fields:

It is worth to note that the reflected and transmitted beams are―due to the presence of the transmission and reflection amplitudes inside these integrals―not Gaussian beams any more. This makes them no longer have the symmetries of the incident beam. Thus, we need a criterion to define the direction of propagation of the transmitted and reflected beams. It seems plausible to define this direction tracing a circle of radius r from the center of the beam, and, for each r, look for the local maximum of

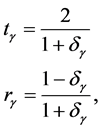

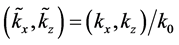

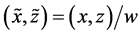

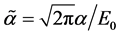

It is convenient for both, calculations and analysis, to express the above relations regarding the composition of the beam in terms of dimensionless quantities. For this, we define

In terms of these quantities, Equation (43) can be expressed equivalently as,

Naturally, there are analogous dimensionless quantities for the reflected and transmitted beams (47). In terms of

which are dimensionless measures of the averages of

We will now take a look at the results of numerical simulations of the refraction of the Gaussian beam. These computations were obtained through a custom c program and plotted in gnuplot with a little help of bash. The source code can be freely downloaded from our page1. For the plotting, we present here some numerical results with effective-medium anisotropic parameters from actual metamaterial experimental reports [43] and [44] .

The first material is a laminate metamaterial (LM) made up of a succession of sheets of silver and silica. We took the effective properties at 400 nm of the seven-layered version. This material does not respond mag- netically but has an electrical anisotropic permittivity. Its parallel component for this wavelength is

The second metamaterial is a split ring resonator (SRR). SRR’s were the first constructed metamaterials in which negative refraction was observed. In order to obtain an isotropic response they were built by placing equal resonators on the cells of a cubic lattice. This SSR omitted the isotropization process, placing the resonators in parallel sheets, thus obtaining an uniaxal anisotropic metamaterial. At a microwave frequency of 1.8 GHz the effective properties (again, ignoring the imaginary part) are

Some points to take into account when looking at the results of the simulations are:

1) Due to the dimensionless representation we are using, the units of length in the plots are the width of the beam. Therefore, a same plot with larger larger units of length is equivalent to a thinner beam and vice-versa. In all the figures presented here, we use a parameter

2) The fields

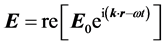

First of all and in order to clarify the idea we have been discussing about the refraction of a light beam, we show in Figure 1 the plot of a beam seen from “far away”. This is the picture of a beam impinging from vacuum at an angle

The symmetry of the beam described in the preceding section makes us expect that in some approximation the propagation of the beam is represented by the propagation of the main mode. Thus, we also indicate the direction of

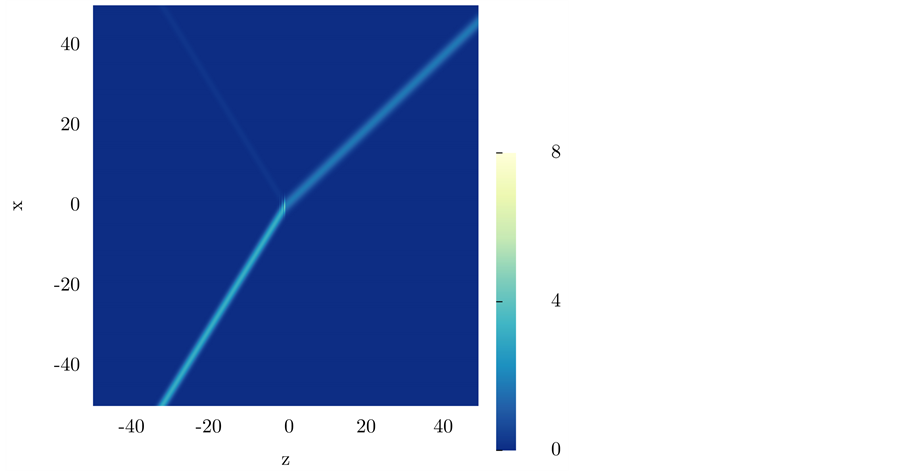

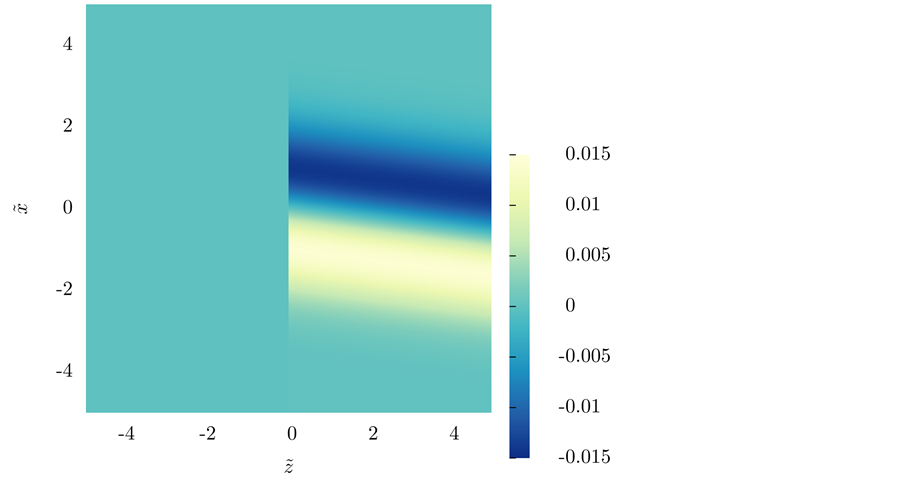

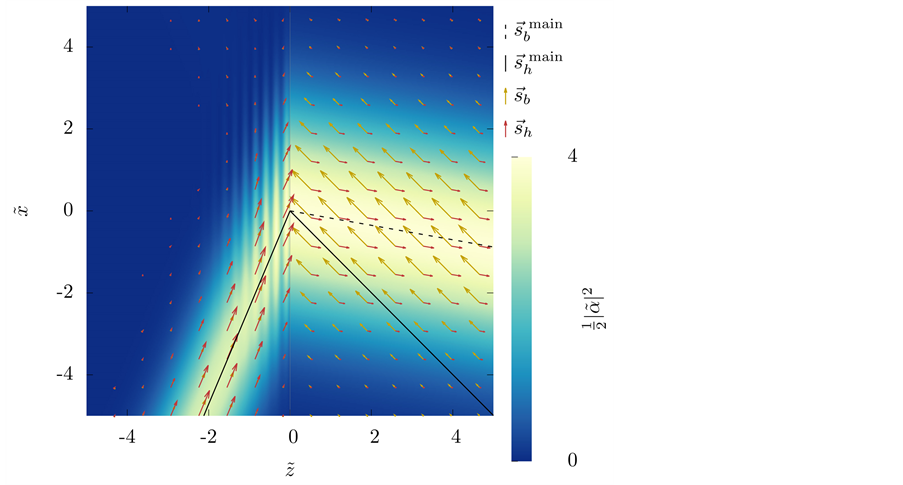

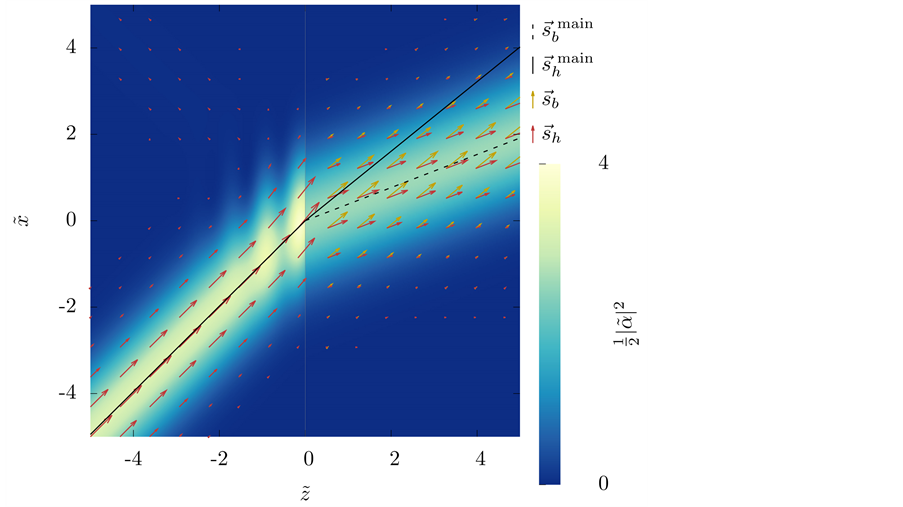

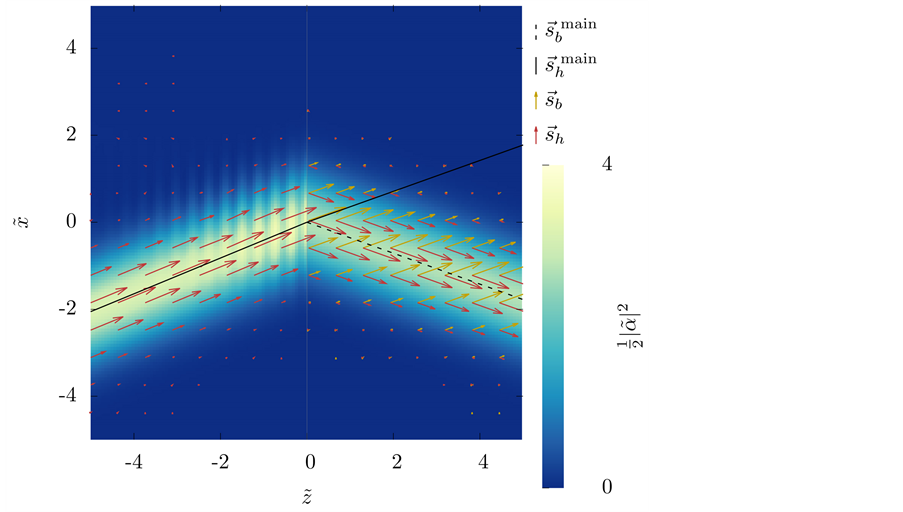

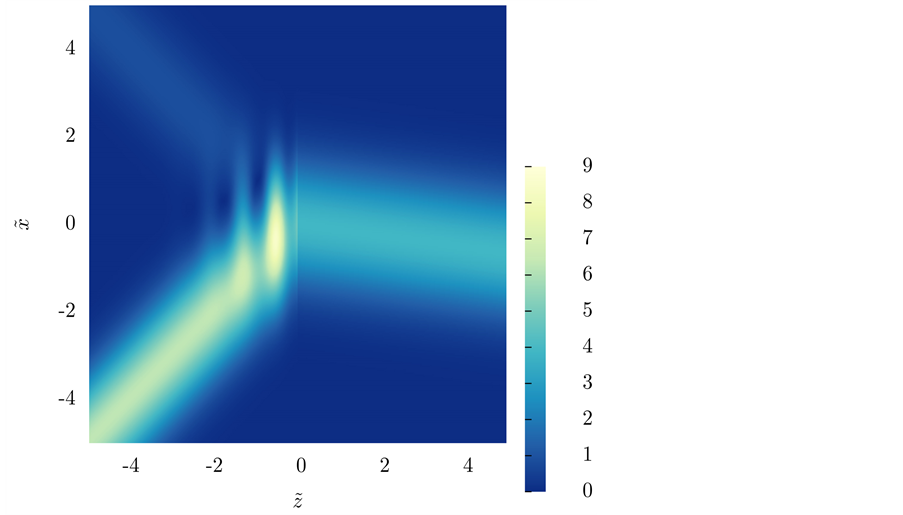

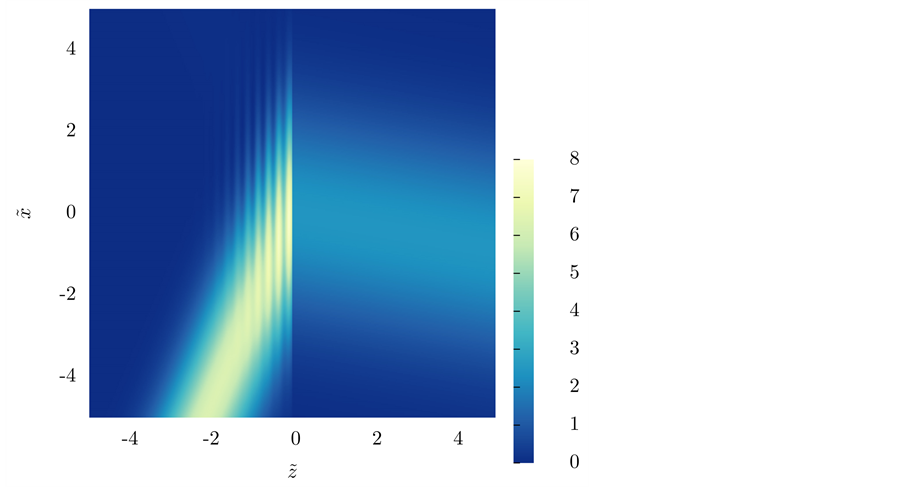

We present the results for the refraction of the beam at a vacuum-LM interface in Figure 2 and Figure 4; and at a vacuum-SRR interface in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The plots include the energy-density patterns, the field lines of

There are some features of these results that we would like to remark:

1) Unlike Figure 1, all the figures show an interference pattern between the incident and the reflected beam.

Figure 1. Gaussian beam refraction and reflection from vacuum into diamond, when viewed from far away.

Figure 2. Refraction of the Gaussian beam from vacuum towards the LM for

A stationary field is established by this interference, just as it happens in the interference between incident and reflected plane waves on an interface, case in which the interference term is a function exclusively of z. This characteristic is somewhat preserved in the beam although it is highly localized (these plots are just windows of

2) Away from the interference zone, the direction of both

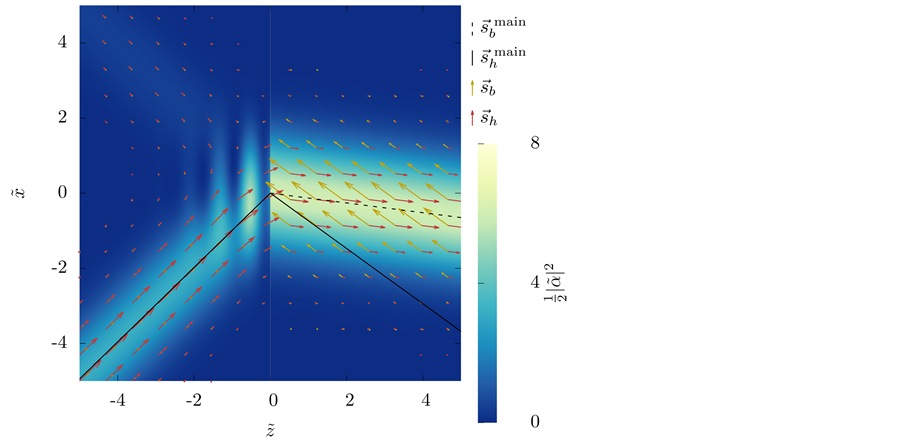

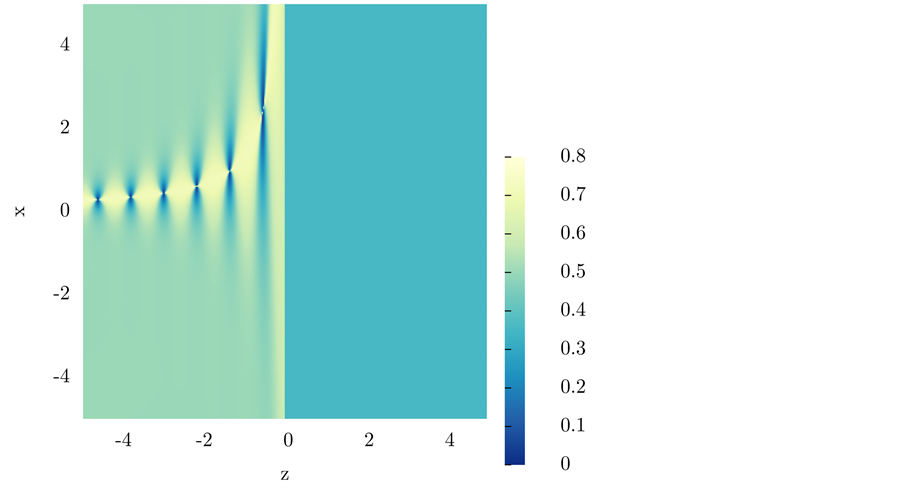

Figure 3. Divergence of

Figure 4. Refraction of the Gaussian beam from vacuum towards the LM for

viewed from far away, we would only notice an abrupt change in direction from the incidence to the refraction angle.

3) As expected, both

4) The “rays” of

5) In all the simulations that we displayed, the line traced by the local maxima of

6) The magnitude of both

7) In Figure 2 and Figure 4 the transmitted beam seems more intense than the incident beam.

And last, perhaps the most important observations:

8) For all cases,

9) Some of the basic refraction properties of the propagation of plane waves in uniaxial metamaterials re- ferred in Section 3 are preserved in the case of the beam: a) Negative refraction is obtained when

10) In the metamaterial, the field

This results reveal that for this beam the main wave represents an astonishingly good approximation to the beam in geometrical terms. In general, it is important to remark that such agreement is by no means obvious, since the energy and energy flux are not linear quantities; in fact, it does not happen in other less symmetrical beams, which we do not treat here for the sake of brevity.

The point labeled 6 about

Figure 5. Refraction of the Gaussian beam from vacuum towards the SRR for

Figure 6. Refraction of the Gaussian beam from vacuum towards the SRR for

direction of

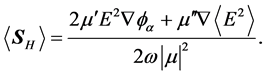

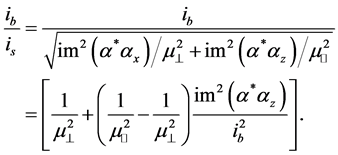

Let us define

Written in this way, we can recognize the term

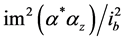

On the other hand, note, from Equation (35) that the essential difference between

The numerical analysis of these two quantities

Figure 7. Proportion between

Figure 8. Magnitude of

Figure 9. Magnitude of

The discussion of the intensity predictions of the two choices of the Poynting vector also leads to an intere- sting question: Since we define intensity as proportional to the energy density, one could ask if there exists a device capable of responding to this quantity. Consider an idealized “intensity detector” consisting of a small plane screen, whose detection result is the integration of the intensity over such surface. Center this detector in a point along the axis of the Gaussian beam. First, put the screen aligned with the axis and take a measure with this device. Afterwards, put the screen in the orthogonal position (remember this is a 2D beam) and take a second measure. Since in the first case the axis coincides with the line of maxima of intensity, the measure is necessarily greater than in the second. But our experience with detectors tells us this is not the case; in fact, it is exactly opposite. This is important because, since

It is also important to stress that the results we show here make evident that in general the ray directions in the formalism of geometrical optics and the notion of a ray as an idealized narrow beam (characterized by its intensity) are not equivalent.

6. Conclusions

We discussed the choice between two possible expressions for the Poynting vector: 1)

1) For any monochromatic 2D field and in any medium (even absorbing ones) there is a “ray” formalism which extends the eikonal formalism. The directions of those “rays” are given, in s polarization, by

2) The directions of the rays, defined in this work as idealized narrow beams, coincide within the simulations presented here with the Poynting vector if we define it as

a) The “ray” formalism described in conclusion 1 (and therefore the eikonal formalism) is not equivalent to the “intuitive” notion of light ray given by idealized narrow beams.

b) Following the geometrical criterion proposed here, the field

c) The definition of light ray as an idealized narrow beam and the results obtained here allow us to associate the light rays with the field lines of the

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Vadim A. Markel for stimulating discussion at the early stages of this project; Augusto García-Valenzuela and Roberto Alexander-Katz for their comments and the full review of the paper; and to Víctor Romero-Rochín for very interesting discussions related to topics about energy conservation. One of us (CP-L) must acknowledge that the work presented here was supported by a graduate scholarship granted by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (México).

Cite this paper

Carlos Prieto-López,Rubén G. Barrera, (2016) Electromagnetic-Energy Flow in Anisotropic Metamaterials: The Proper Choice of Poynting’s Vector. Journal of Modern Physics,07,1519-1539. doi: 10.4236/jmp.2016.712139

References

- 1. Chen, H., Zhang, J., Bai, Y., Luo, Y., Ran, L. and Jiang, Q. (2006) Optics Express, 14, 12944-12949.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.14.012944 - 2. Papadakis, G.T., Yeh, P. and Atwater, H.A. (2014) Physical Review B, 91, Article ID: 155406.

- 3. Prieto-López, C. and Barrera, R.G. (2012) Physica Status Solidi (b), 249, 1110-1118.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201100747 - 4. Malacara-Hernández, D. and Malacara-Hernández, Z. (2003) Handbook of Optical Design. 2nd Edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1201/9780203912942 - 5. Kline, M. and Kay, I.W. (1965) Electromagnetic Theory and Geometrical Optics. Interscience Publishers, Hoboken.

- 6. Alonso, M.A. (2010) Phase-Space Optics: Fundamentals and Applications. McGraw-Hill Professional, New York.

- 7. Costa, J.T., Silveirinha, M.G. and Alù, A. (2011) Physical Review B, 83, Article ID: 165120.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.83.165120 - 8. Boardman, A.D. and Marinov, K. (2006) Physical Review B, 73, Article ID: 165110.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.73.165110 - 9. Ruppin, R. (2002) Physics Letters A, 299, 309-312.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9601(01)00838-6 - 10. Cui, T.J. and Kong, J.A. (2004) Physical Review B, 70, Article ID: 205106.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.70.205106 - 11. Ziolowski, R.W. and Heyman, E. (2001) Physical Review E, 64, Article ID: 056625.

- 12. Tretyakov, S.A. (2005) Physics Letters A, 343, 231-237.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2005.06.023 - 13. Simovski, C.R. and Tretyakov, S.A. (2007) Physical Review B, 75, Article ID: 195111.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.75.195111 - 14. Richter, F., Henneberger, K. and Florian, M. (2010) Physical Review B, 82, Article ID: 037103.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.82.037103 - 15. Kinsler, P., Favaro, A. and McCall, M.W. (2009) European Journal of Physics, 30, 983-993.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/30/5/007 - 16. Obukhov, Y.N. and Hehl, F.W. (2003) Physics Letters A, 311, 277-284.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9601(03)00503-6 - 17. Richter, F., Florian, M. and Henneberger, K. (2008) Europhysics Letters, 81, 67005-67009.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/81/67005 - 18. Silveirinha, M.G. (2010) Physical Review B, 82, Article ID: 037104.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.82.037104 - 19. Silveirinha, M.G. (2009) Physical Review B, 80, Article ID: 235120.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physrevb.80.235120 - 20. Mansuripur, M. (2011) Optics Communications, 284, 594-602.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2010.08.079 - 21. Markel, V.A. (2009) Optics Express, 17, 7325-7327.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.17.007325 - 22. Marqués, R. (2009) Optics Express, 17, 7322-7324.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.17.007322 - 23. Markel, V.A. (2008) Optics Express, 16, 19152-19168.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.019152 - 24. Mischenko, M.I. (2014) Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy & Radiative Transfe, 146, 4-33.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2014.02.033 - 25. Pfeifer, R.N.C. and Nieminen, N.R. (2007) Reviews of Modern Physics, 79, 1197-1216.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.79.1197 - 26. Minkowsky, H. (1910) Mathematische Annalen, 68, 472-525.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01455871 - 27. Abraham, M. (1909) Annalen der Physik, 322, 891-921.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/bf03018208 - 28. Ginzburg, V.L. (1973) Soviet Physics Uspekhi, 16, 434.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1070/PU1973v016n03ABEH005193 - 29. Roche, J.J. (2000) American Journal of Physics, 68, 438-449.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.19459 - 30. Nelson, D.F. (1996) Physical Review Letters, 76, 4713-4716.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.4713 - 31. Campos, I. and Jiménez, J.L. (1992) European Journal of Physics, 13, 117-121.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/13/3/003 - 32. Furry, W.H. (1969) American Journal of Physics, 37, 621-636.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.1975729 - 33. Mansuripur, M. and Zakharian, A.R. (2009) Physical Review E, 79, Article ID: 026608.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/physreve.79.026608 - 34. Feynman, R.P., Leighton, R.B. and Sands, M. (1964) The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Volume 2, Addison-Wesley, Upper Saddle River.

- 35. Barrera, R.G., Mochán, W.L., García-Valenzuela, A. and Gutiérrez-Reyes, E. (2010) Physica B Condensed Matter, 405, 2920-2924.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2010.01.004 - 36. Henrotte, F. and Hameyer, K. (2006) IEEE Transactions on Magnetics, 42, 903-906.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2006.871441 - 37. Gough, W. (1982) European Journal of Physics, 3, 83-87.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/3/2/005 - 38. Romer, R.H. (1982) American Journal of Physics, 50, 1166-1168.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.12903 - 39. Peters, P.C. (1982) American Journal of Physics, 50, 1165.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.13024 - 40. Lai, C.S. (1981) American Journal of Physics, 49, 841-843.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1119/1.12719 - 41. Slepian, J. (1942) Journal of Applied Physics, 13, 512-518.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.1714903 - 42. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1984) Electrodynamics of Continuous Media. Pergamon Press, Oxford.

- 43. Jackson, J.D. (1998) Classical Electrodynamics. 3rd Edition, John Wiley & Sons Inc., Hoboken.

- 44. Brillouin, L. (1960) Wave Propagation and Group Velocity. Academic Press, New York.

NOTES

1http://www.fisica.unam.mx/personales/rbarrera/gaussian-beam.