Creative Education

Vol.06 No.17(2015), Article ID:60657,15 pages

10.4236/ce.2015.617198

Assessment of the Environment with DREEM at a Medical School Using Active Methodologies and an Integrated Curriculum

Joaquim Edson Vieira1, José Lucio Martins Machado2, Sandra Maria Alessandri Ribeiro3*

1Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sao Paulo (FMUSP) Researcher at the Health Education Development Center “Prof. Eduardo Marcondes”―CEDEM (USP), São Paulo, Brazil

2Professor at the Masters and Doctorate Program at the Hospital for State Civil Servants (IAMSPE), São Paulo, Brazil

3Graduate Student of the Master’s in Health Sciences at the Hospital for State Civil Servants (IAMSPE), São Paulo, Brazil

Email: *sandramalessandri@ig.com.br

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 18 June 2015; accepted 25 October 2015; published 28 October 2015

ABSTRACT

This research presents an analysis of the University City of São Paulo (UNICID) medical school teaching and learning environment, a school in Brazyl which employs active methodologies. A total of three hundred and ninety one students participated voluntarily in the research, being one hundred and fifty five students on its first phase, in the year of 2006, and two hundred and thirty six students in 2009. The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) has been employed for accessing an evaluation of UNICID medical school academic environment. The DREEM questionnaire consists on 50 items assessing the school’s educational environment in five di- mensions, to which scores have been attributed. A maximum of 200 points have been ascribed according to each dimension: Perception of Learning (with 12 items and maximum score of 48 points), Perception of Teaching (with 11 items and maximum score of 44 points), Academic Self- perception (with 8 items and maximum score of 32 points), Perception of the Environment (with 12 items and maximum score of 48 points) and Social Self-perception (with 7 items and maximum score of 28 points). The higher the score reaches, the more positively can be regarded the results. As the results show, the score increases in the second phase of the research. Each dimension will be analyzed separately and the differences in scores between them will be explained.

Keywords:

Education, Medical, Undergraduate, Social Environment, Program Evaluation, Problem-Based Learning

1. Introduction

The analysis of the learning environment from the perspective of the students is deemed as an effective indicator of the quality of both learning and teaching processes in undergraduate studies in the field of health studies (Vieira, 2003; Oliveira, 2005; Genn, 1986; Roff, 2005) . Environment, more than geographical space in which students develop their academic activities, includes the state of mind and the motivation to learn (Roff, 2001; Flexner, 1910) . How the student feels, perceives or experiences the educational environment can be termed “climate”. Each of us has a unique view of what’s happening around us, so that in the same environment the “climate” can be perceived differently for each student (Roff, 2001) .

Undergraduate courses in medicine differ in terms of the adopted curriculum. There can either be traditionally structured, with disciplines and its cycles (basic and professional) grounded in the Flexner (Flexner, 1910) report, or an innovative type of curriculum, using active problem-based methodologies for problem building, questioning and learning (Problem-Based Learning―PBL). The present research sheds light on a course that is structured over the PBL active method (Almeida, 2013; Gomes, 2011) .

Changes felt in recent years by the health care system model implemented in Brazil created a demand for professional skills that soon were found to be scarce (Gomes, 2011) . This conclusion led to the creation, in 2001, of the Program of Incentives for Curricular Changes in Medical Courses (PROMED), aimed at reorienting medical schools teaching in order to meet the need to fulfill the specific skill demanded by the transformed system. This program advised for the use of active learning methodologies in the promotion of training to health professionals. This increasing attention to methodological aspects has been further strengthened by the launching, in 2005, of the National Reorientation of Vocational Training Program (PROMED) by the Ministries of Health and Education. Although there are no Brazilian studies comparing medical graduates in the traditional curriculum with graduates in innovative curriculum, there exists evidence to suggest the adequacy of the use of problem-based learning methodologies as a means to matching the above mentioned guidance in the provision of education in medicine in Brazil (Almeida, 2013; Gomes, 2011) .

The medical courses under the traditional curriculum had to adapt to new demands in order to comply with those guidelines. In this sense, the importance of the present study is to provide an account of the implementation of a curriculum structure under the new set of orientation according to the new methodologies prescribed. It is important to specify, however, that the course evaluated in this study has been designed from its origin under the realm of the active methodology called problem-based learning. In that sense, the course of medicine at UNICID meets the guidelines of the National Curriculum Guidelines for Medical Graduation Course for fully preparing future professionals in their psycho-motor, cognitive and emotional skills and by further emphasizing ethical aspects concerning the medical profession as well as by promoting their commitment to broader sense of responsibility and citizenship (Brasil, 2001) .

The innovative curriculum of this course encourages the student to develop professional autonomy, capacity for comprehensive analysis and critical thinking, without overestimating biological aspects implied in the medical career (Genn, 2001) . UNICID medical course prioritizes that the students develop the skill of learning how to learn, and that they may acquire significant learning by practicing. By doing so the construction of knowledge and the development of the necessary competences and skills may come along their formation as students so that they become able to effectively solve real situations in their future professional practice (Komatsu, 2003) . The problem-based learning, structural axis of this course, promotes the building of new knowledge by retrieving student’s prior knowledge and directing it towards new learning goals set for the solution of each and new problem established. Throughout the course, the students are faced with new information in each week. Under this active method, the students ought to muster their personal needs and gather a variety of educational resources to fulfill their educational experience (Roff, 2001; Dent, 2009; Knowles, 1997; Genn, 2001) .

In light of the conceptual elements of contemporary medical education (Machado, 2011) the course environment here analyzed satisfies the principle that curriculum frameworks may integrate theoretical knowledge proper of basic cycles and applied knowledge acquired in practical activities developed throughout the student life within the course. The ongoing acquisition of medical practical expertise is developed both in laboratories of specific skills and in Basic Health Units (Unidades Básicas de Saúde). The laboratory course activities occur in small groups. Further to these indoor activities, the students are tutored out to the field and exposed to real-life demands. By doing so, they are demanded to deal with changing scenarios and requested to exercise the search for appropriate solutions to each emergent condition. This is a continued experience taking place gradually at the ambulatory and Basic Health Units settings, since the first weeks of the undergraduate life experience, up to proper hospital environment in the latter cycles of the course. Active teaching and learning methodologies are the basis of this innovative course curriculum. But are these principles capable of ensuring an appropriate teaching- learning environment? That has been the guiding questioning for the realization of the research in place.

The worldwide interest in medical education has been expressed in the development of instruments for evaluating the educational environment. This research gives special emphasis on the instrument for capturing student’s perception over that environment, the Dundee Ready Education Environmental Measure (DREEM) (Genn, 1986; Roff, 1997) . The DREEM has been used worldwide for evaluating higher education teaching environment in the realm of health (Genn, 1986; Roff, 1997; Mayya, 2004; McAleer, 2002; Roff, 2001; Jiffry, 2005; Jamaiah, 2008; Till, 2002; Al Hazimi, 2004; Pimparyon, 2000) .

Evaluating a teach-and-learn environment from the angle of the students’ perception is helpful to provide important elements for eventual guidance and corrections in the management level (McAleer, 2002; Till, 2005) . The DREEM instrument has been employed in Portuguese language and validated for the identification of strengths and weaknesses within the environment of the medicine course at UNICID and to access whether there is significant differences registered in the perception exposed by the participant students in the two phases of the study (in 2006 and in 2009).

2. Method

This study has been granted the approval by the Committee of Research Ethics from the University in vogue. The study was done with voluntary participation of students. Participants were students enrolled in the first five semesters of medical school. The student population for research in 2006 was composed of all students enrolled in the medical school from first to fifth semesters, who agreed to participate. For comparison purposes, it was decided that in 2009 the population of students who respond to the inventory would be enrolled in the first to fifth semesters as the first application in 2006. The questionnaire was applied by the researcher personally to all students who agreed to participate. The application was made to all students of a same semester in only moment, in the place of the university where gather for activities. Since it was advocated participation of all students of the first five semesters of the course on both occasions, it was not calculated the power of the sample.

The perceptions registered have been grouped within five dimensions: Perception of Learning, Perception of Teaching, Academic Self-perception, Perception of the Environment and Social Self-perception.

The DREEM consists of 50 items that cover relevant aspects circumventing the educational environment. Each item has been ascribed a scored ranging from zero to four, being 4 to “completely agree”, 3 to “agree”, 2 “neither agree nor disagree”, 1 for “strongly disagree” and 0 for “completely disagree” (Appendix). Nine items pose negative statements and for these nine statements the scores have been reversed in order to ensure that the highest value indicates the most favorable perception (Table 1)

The DREEM’s dimensions and the maximum scores are as follows:

• Perception of Learning, with 12 items and maximum score of 48 points (Table 2);

• Perception of Teaching, with 11 items and maximum score of 44 points (Table 3);

• Academic Self-perception, with 8 items and maximum score of 32 points (Table 4);

• Environmental Perception, with 12 items and maximum score of 48 points (Table 5):

• Social Self-perception, with 7 items and maximum score of 28 points (Table 6);

Table 1. Score allocation for items of DREEM.

Table 2. DREEM―perception of learning items.

Table 3. DREEM―perception of teaching items.

Table 4. DREEM―academic self-perception items.

Table 5. DREEM―perception of environment items.

Table 6. DREEM―Social Self-perception items.

The maximum total score of the DREEM instrument is 200 points and the interpretation of the results is made by measuring the teaching-learning environment according to the score range achieved. The interpretation of the values follows the prescription (Table 7).

The participation has been voluntary, and the DREEM instrument has been applied in two different occasions to students of the first five semesters, being 159 students in the year of 2006 and 236 students in the year of 2009. The DREEM have been applied in print format. A 100% response rate was achieved. The questionnaires were returned to the researcher and the results have been analyzed through descriptive statistics and considered significant at p < 0.05. The Cronbach alpha coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency of the DREEM instrument as a whole and of each domain to the study population.

3. Results and Discussion

The age range of the population participating in the two phases of the research did not differ, being the average equal to 22 years old. The gender distribution has changed, however, amongst the two moments: there was a predominance of the female gender (55%) in 2006, and a predominance of male gender in 2009 (53%).

The DREEM average total score was 130.9 ± 21.8 in 2006 and 135.1 ± 22.87 in 2009. The difference was significant (t = 3.986, df = 393, p < 0.001) with little effect on the sample size (Cohen’s d = 0.307, r = 0.201) (Table 8).

The interpretation of the results is performed for both total score and the score for each of the five domains assessed (Table 9).

Table 7. Interpretation of scores of DREEM.

Table 8. DREEM―score of each item in 2006 and 2009.

The results below show the distribution of questionnaires by score range achieved in two stages of the study (Table 10).

The environment has been rated as excellent (score > 151) by 13.8% of students in 2006 and 23.7% of students in 2009. The results show the students’ perception of the teaching and learning environment as full of good points or even excellent for 95.6% of students in 2006, and 93.7% of students in 2009. The adherence to the study grew from 63.4% in 2006 to 94.4% in 2009, indicating an increase of 48.5% in voluntary participation. There can be seen an increase of 3.8% in scores from 130.9 to 135.1 in the interval considered, which surmounts the augmentation in the number of participants, which was 0.4% higher in 2009 than in 2006. This indicates an improved perception of the education environment.

As the DREEM questionnaire classifies the educational environment from the perspective of five areas (perception of earning, teaching and environment as well as academic and Social Self-perception), it’s possible to detect strengths and weaknesses of the course that may be impacting on the student’s physical, psychological and motivational aspects ( Genn, 1986; Roff, 1997 ; Ferguson, 2003). By pondering the relative values to each domain staged according to directions suggested by the authors of DREEM we come to establish comparisons

Table 9. Interpretation of results of DREEM.

Table 10. Distribution of questionnaires according to scores obtained.

amongst them without incurring in bias resulting from the different number of items ascribed of each of those areas. The appropriateness of percentage values for each domain, nonetheless, doesn’t hide the fact that “there will always be room for improvement toward the ideal environment” (Gen, 1986).

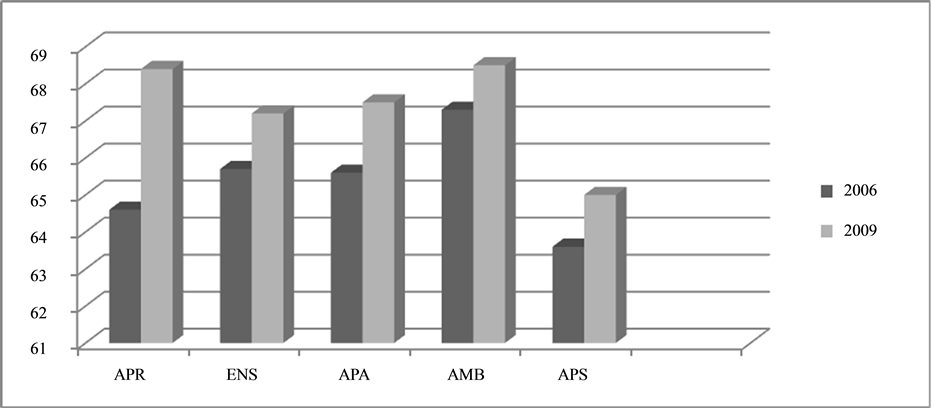

The results make evident a growth in the scores of the five areas from 2006 to 2009: in the Learning Perception, from 31.3 (65.2% of the maximum score 48) in 2006 to 32.9 (68.5%) in 2009; in Education Perception, from 28.8 (65.4% of the maximum score 44) in 2006 to 29.7 (67.5%) in 2009; the Academic Self-perception, from 21.1 (65.9% of the maximum score 32) in 2006 to 21.4 (66.9%) in 2009; in Environmental Perception, from 32.4 (67.5% of the maximum score 48) in 2006 to 32.9 (68.5%) in 2009, and the Social Self-perception, from 17.9 (63.9% of the maximum score 28) in 2006 to 18.2 (65%) in 2009. These results can be read as a considerable manifestation of improvement in the teaching-learning environment according to the student’s perceptions (Figure 1).

The survey allows for identification of both positive and negative aspects related to the medicine course environment evaluated in this study (Table 11).

In the domain of Perception of Learning, throughout the answers to the questionnaire applied in the year 2006, only one item (item 16―teaching activities takes into consideration the development of my competences) registered a pronouncedly positive point of the course as perceived by the students inquired, while in 2009 five items (1―I am encouraged to participate in class; 13―Teaching is student-centered; 16―Teaching is concerned with developing my competences; 44―Teaching encourages me to pursue my own learning needs and 47―The importance of continued education is emphasized) register high scores indicating elements of strengths of the course according to the student’s perception. The low scores registered in the item 25 (“Teaching overemphasizes learning through memorizing”) indicates a weakness of course suggesting discomfort of the students with the observed condition.

As for aspect Perception of Teaching, the item number 2 (“It is possible to understand teachers in classrooms”) registered high scores in both phases of the study, which allows for the understanding of being this strength of the course. The remaining ten items that make up this area obtained scores between 2 and 3 which allow the conclusion that this area is perceived by students as having the most positive aspects than negative ones.

As for Academic Self-perception, in the questionnaire in 2006 only item 31 (“I have learned a lot about interpersonal relationships in this profession”), indicates a strong point, while in 2009 two more items reached high scores, indicating strengths: item 10 (“I am confident that I will pass exams this year”) and item 45 (“Much of what I’ve seen is important for medicine”), indicating an improvement in this area compared to 2006.

In the dimension Perception of the Environment, in 2006, only item 12 (“This faculty is quite exact in its course”) presents score indicating a strong point. In 2009, however, three other items were added as strengths in the dimension Perception in Environment, being these the items 30 (“I have the opportunity to develop interpersonal relationship”), item 35 (“I have found my experience disappointing”, in inverted sings) and 42 (“Satisfaction

Figure 1. Scores percentage of DREEM domains in medical school in 2006 and 2009.

Table 11. Items DREEM indicating strengths (3 or >) and weaknesses (2 or <).

is greater than the stress of studying medicine”), reinforcing the perception of quality of the course as suggested by student’s responses.

As for the Social Self-perception, both in 2006 and in 2009, the strengths are indicated by items 15 (“I’ve made good friends in college”), 19 (“I treasure my social life”) and 46 (“Live in a comfortable place”). One of the weaknesses of the course is found in this area, corresponding to the item 3 (“There is support for students who find themselves under stress”) to which DREEM results referenced registered low scores.

We note then that there was an increase from 2006 to 2009 in the frequency of items that represent strengths of the course evaluated. The classification from the perspective of each domain indicates a changing perception to learning and teaching activities towards a more positive one. Academic Self-perception also reflected tendencies of improvements from 2006 to 2009. Students registered a more positive attitude towards their perception of the environment and their social perception, conclusions drawn according to the criterion of interpretation of the results of DREEM (Table 7).

The internal consistency of DREEM in each dimension (Cronbach alpha coefficient > 0.9) showed the suitability of the questionnaire to the population evaluated, confirming the findings of many other studies that used the DREEM in its original form (Genn, 1986; Roff, 1997; Mayya, 2004; McAleer, 2002; Roff, 2001; Jiffry, 2005; Jamaiah, 2008; Till, 2002; Al Hazimi, 2004; Pimparyon, 2000) or in its version in Portuguese language.

Although the DREEM is an instrument that has been employed since 1997, we shall not forget that there may be other aspects of teaching in medical schools that are not taken into account in this survey format. The environment may include dimensions not measured by DREEM as student’s expectations, motivation and individual learning strategies, one’s own personality, and may set important aspects of the context of the environment apart (Fergunson, 2003) .

The results of this study in each of its phases might have been influenced by aspects that simply couldn’t be measured or quantified. At the time of the first application of DREEM in 2006 the medicine course at UNICID had recently been initiated: its activities had begun two years prior to that year, in 2004. Therefore, the curriculum to each academic semester hadn’t been tested for long. As for the extreme example, the fifth semester by then was being offered for the very first time. On the other hand, by the time the second application, in 2009, the courses to each academic semester had already been offered repeatedly, with the above mentioned example (the fifth semester) being offered for the seventh time. Increased experience acquired by the teaching staff in preparing the content of each module may conceivably have played a role as an intervening variable, but that remained as an uncontrolled factor to the present analysis to the teaching and learning environment according student’s perception.

The voluntary adherence of 94.4% of the students in 2009 contrasts with the 63.6% of adherence in 2006. This improvement reflects positively to the diffusion of a culture of evaluation in the educational environment over the years among the students proper, and attaches greater attention to the recognition, by the students themselves, of opportunities in emergent issues of teaching and learning.

The DREEM does not provide information about how would it be the ideal environment from the student’s point of view. There are global studies that propose, in a single moment, to submit two DREEM questionnaires for each survey participant at a time, being one for the record of student’s answers about how would the ideal environment is, and another for condensing their perception of the actual environment. The resulting analysis would be achieved by means of correlating both (Till, 2005) . Further investigation would also benefit from the correlation of DREEM results in terms of one’s own perception with data relative to student performance in academic life.

As the results restricted to the purposes of this study indicate, there is a predominance of positive aspects in the teaching and learning environment of the course in medicine in the two periods evaluated. The total average DREEM score of 130.9 in 2006 and 135.1 in 2009 are comparable to the best results for the global studies with the same instrument (Table 12).

Table 12. DREEM application results in the world.

In comparing our results with other fifteen world works application of DREEM to access teaching and learning environment, the total score in 2009 stands for the highest values registered And the lowest value registered in 2006 is only lower than that obtained in the Scottish Medical School (134/200) (Al Hazimi, 2004) and Dundee University Medical School (132.3) (McAleer, 2002) . UNICID’s results are higher than those of other assess- ments in six courses with innovative curriculum in India (110/200, 107/200) (Mayya, 2004) , Turkey (117/200), Canada (113/200; 98/200), Nepal (130/200) (Roff, 2001) , and even higher than the results obtained in six other DREEM applications in courses with traditional curriculum in Malaysia (118/200, 125/200) (Jamaiah, 2008) , in Saudi Arabia (102/200, 107/200) (Al Hazimi, 2004) , University of Brasilia (123.1/200) (Vieira, 2003) and Yemen (100/200).

By observing the average score of each item it is possible to note that, in 2009, students feel more encouraged to participate in class activities than they seemed to be in 2006. They also allegedly feel more encouraged to behave as active learners and perceive the school as impelling, centered on them as student and focused in helping to develop their confidence and competence. Students express their perception of importance attached to the focus of teaching and learning activities on the long-term and consider positive that it is prioritized over the short-term perspective. They consider that teaching is less focused on the teacher than it is on the students themselves and feel encouraged to seek their own learning, which is essential for success in active methodologies (Almeida, 2013) . Students perceive their teachers as well prepared, with good communication skills towards their patients, apt to give appropriate feedbacks to the students, to make constructive criticism statements and to provide clear examples, resuming the Perception of Teaching as an overall positive dimension in the two phases of the study.

Students picture themselves as receiving adequate preparation for the profession, learning a lot about interpersonal relationship. They realize that the work of the previous period’s cycles in the course translated into suitable preparation for current assignments. Consider also that the tools for problem solving are being well developed, and are important for the qualification of their future actions as professionals in medicine. They agree that much of what has been seen is important for medicine, and that this perception of theirs increases the motivation to learn, according to the principles of Andragogia (Knowles, 1997; Knowles, 1975) . Students feel the atmosphere in the course of seminars and tutoring activities as being unperturbed, that people’s attitudes are friendly during classes, that this allow for the creation of opportunities to develop interpersonal social skills comfortably. Students also perceive themselves as having good concentration.

They disagree with the assertion that the experience in the course is disappointing and mostly feel that satisfaction with that they do relieves eventual tension in studying medicine. They find the surrounding atmosphere to motivate them to be active learners, a characteristic that attest for the environment to be said Positive, which may contribute to increase students motivation (Knowles, 1997; Knowles, 1975) . The low average score of item 27 which refers to the student’s ability to memorize every content needed, both in 2006 and in 2009, resonates with that of other studies handled worldwide (Mayya, 2004; Roff, 2001; Al Hazimi, 2004) . This may be a reflex of the perception of students to item 25 (“Teaching overemphasizes learning through memorizing”), which indicates student’s feeling to be somehow overwhelmed by the demand for memorizing disciplinary contents. Items that claim that tutors are well prepared and that the school encourages students to pursue their own learning were highly rated, fact relevant to a course with active methods where the student interest in the pursuit of knowledge is a key factor. The results also point to the perception of students own social status as positive, reflecting somehow the favored economic background of most students engaged in this course of medicine.

The results obtained in this study point out to four strong points of the teaching-learning environment of the course in 2006, reaching up to fourteen strong points distributed along five areas (Table 11) in 2009. This improvement indicates an overall strengthening of the teaching-learning environment at UNICID medicine course.

The identified weaknesses refer to the lack of support for students who might find themselves under stress and overwhelmed by demands for learning and memorization. UNICID results for item 3, on the lack of such support to students, are not as low as those of other global studies. This resonates with the perception that the satisfaction with medicine course at UNICID outweighs the overall perceived stress resulting from demands in studying medicine, evidence obtained through the high score achieved in the item 42.

The low average score obtained in the two phases for the item which states that the teaching activities overemphasizes learning through memorizing reflects the discomfort of the students with the matter. This sheds lights on an issue that deserves special attention as active learning methodologies advocate skils development and integrated knowledge rather than excessively memorizing contents.

Table 13. Items with statistically significant differences between genders score for all students (n = 395).

Analysis of the overall results considering the total number of participating students in the study (N = 395) through the prism of gender showed statistically significant differences throughout the score achieved by fifteen items (Table 13), with lower scores being attributed to women. This might be positively referenced as indicating their higher levels of criticism, opinion so registered in DREEM studies worldwide as well (Roff, 2005) .

The results of this study help sustaining the use of DREEM as a useful and appropriate tool for evaluation of the teaching-learning environment.

4. Conclusion

The results obtained in this study attest the predominance of positive aspects in the teaching and learning environment of the undergraduate course in medicine at UNICID in both phases considered, but with significant increase of positive aspects on the second phase, in 2009. According to UNICID student’s perception registered, their satisfaction with medicine course outweighs eventual tension produced by great demands in medical school. The students perceive themselves at the center of the processes of teaching and learning, fact of highly relevant to achieving in a course based on active methodologies.

The identified weaknesses deserving to be mentioned are the excessive demand for learning through memorizing facts and the lack of support for those who might find themselves under stress by overwhelming demands. Both weaknesses point to the need to provide special attention to those aspects that can make a difference in student performance. The DREEM proved to be a useful tool to identify strengths and weaknesses of the educational environment in the perception of students and guide intervention in the educational environment Performing a comparison of the results registered by DREEM in the evaluation of environment of teaching and learning in reference to other studies with the same questionnary held worldwide, this medicine course is positioned amongst the highest ranks. This study with DREEM can be used as useful basis for a future longitudinal study that monitors the changes implemented and its effects on the perception of students. A measure of how much a favorable or unfavorable perception of the environment can influence academic performance in a course with active methodologies was not made. It will aim for a future study to establish a relationship between the perception of the environment and student performance.

Cite this paper

Joaquim EdsonVieira,José Lucio MartinsMachado,Sandra Maria AlessandriRibeiro, (2015) Assessment of the Environment with DREEM at a Medical School Using Active Methodologies and an Integrated Curriculum. Creative Education,06,1920-1935. doi: 10.4236/ce.2015.617198

References

- 1. Almeida, E. G., & Batista, N. A. (2013). Desempenho docente no contexto PBL: Essência para aprendizagem e formação médica. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 37, 192-2-1.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0100-55022013000200006 - 2. Al Hazimi, A., Zaini, R., Al-Hyiani, A., Hassan, N., Gunaid, A., Ponnamperuma, G. et al. (2004). Environment in Traditional and Innovative Medical Schools: A Study in Four Undergraduate Medical Schools. Education for Health, 17, 192-203.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13576280410001711003 - 3. Al Hazimi, A., Al Hyiani, A., & Roff, S. (2004). Perceptions of the Educational Environment of the Medical School in King Abdul Aziz University, Saudi Arabia. Medical Teacher, 26, 570-573.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590410001711625 - 4. Brasil (2001). Conselho Nacional de Educação, Camara de Educação Superior. Resolução CNE/CES No. 4 de 7 de novembro de 2001. Institui Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais do Curso de Graduação em Medicina. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União. 9 nov. Seção 1, 38.

- 5. Dent, J. A., & Harden, R. M. (2009). A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. In S. McAleer, D. Soemantri, & S. Roff (Eds.), Education Environment (3rd ed., pp. 64-70). Berlin: Elsevier, Chapter 9.

- 6. Fergunson, E., James, D., O’hehir, F., Sanders, A., & McManus, I. C. (2003). Pilot Study of the Roles of Personality, References, and Personal Statements in Relation to Performances over the Five Years of a Medical Degree. British Medical Journal, 326, 429-432.

- 7. Flexner, A. (1910). Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, (Bulletin, 4).

- 8. Genn, J. M. (2001). AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 23 (Part 1): Curriculum, Environment, Climate, Quality and Change in Medical Education—A Unifying Perspective. Medical Teacher, 23, 337-344.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590120063330 - 9. Genn, J. M., & Harden, R. M. (1986). What Is Medical Education here really like? Suggestions for Action Research Studies of Climates of Medical Environments. Medical Teacher, 8, 111-124.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/01421598609010737 - 10. Gomes, A. P., & Rego, S. (2011). Transformação da educação médica: &EACUTE; possível formar um novo médico a partir de mudanças no método de ensino-aprendizagem? Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 35, 557-566.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/s0100-55022011000400016 - 11. Jamaiah, I. (2008). Review of Research in Learning Environment. Journal of University of Malaysia Medical Center, 11, 7- 11.

- 12. Jiffry et al. (2005). Student’s Perception of the Educational Environment in a Medical Faculty with an Innovative Curriculum in Sri Lanka. South-East Asian Journal of Medical Education, 4, 9-16.

- 13. Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E.F., & Swanson, R. A. (1997). Aprendizagem de resultados: Uma abordagem prática para au- mentar a efetividade da educação corporativa. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier.

- 14. Knowles, M. (1975). Self-Directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers. New York: Cambridge Book Co.

- 15. Komatsu, R. S. et al. (2003). Guia do Processo de Ensino-Aprendizagem “Aprender a Aprender” (4th ed.). Marília: Faculdade de Medicina de Marília.

- 16. Machado, J. L. M., Machado, V. M., & Vieira, J. E. (2011). Formação e seleção de docentes para currículos inovadores na graduação em Saúde. Revista Brasileira de Educação Médica, 35, 326-333.

- 17. Mayya, S. S., & Roff, S. (2004). Student’s Perceptions of Educational Environment: A Comparison of Academic Achievers and Under-Achievers of Kasturba Medical College, India. Education for Health, 17, 280-291.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13576280400002445 - 18. McAleer, S., & Roff, S. (2002). Part 3: A Practical Guide to Using the Dundee Ready Education Measure (DREEM). In J. M. Genn (Ed.), AMEE Medical Education Guide No.23 Curriculum, Climate, Quality and Change in Medical Education: A Unifying Perspective. Dundee: Association of Medical Education in Europe.

- 19. Oliveira, F. G. R., Vieira, J. E., & Schonhorst, L. (2005). Psychometric Properties of the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) Applied to Medical Residents. Medical Teacher, 27, 343-347.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590500046387 - 20. Pimparyon, P., Roff, S., McAleer, S., Poonchai, B., & Pemba, S. (2000). Educational Environment, Student Approaches to Learning and Academic Achievement in a Thai Nursing School. Medical Teacher, 22, 359-365.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/014215900409456 - 21. Roff, S. (2005). The Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM)—A Generic Instrument for Measuring Students’ Perceptions of Undergraduate Health Professions Curricula. Medical Teacher, 27, 322-325.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590500151054 - 22. Roff, S., & McAleer, S. (2001). What Is Educational Climate? Medical Teacher, 23, 333-334.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421590120063312 - 23. Roff, S., McAleer, S., Ifere, O. S., & Bhattacharya, S. (2001). A Global Diagnostic Tool for Measuring Educational Environment: Comparing Nigeria and Nepal. Medical Teacher, 23, 378-382.

- 24. Roff, S., McAleer, S., Harden, R. M. et al. (1997). Development and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure. Medical Teacher, 19, 295-299.

- 25. Till, H. (2005). Climate Studies: Can Students Perceptions of the Ideal Educational Environment Be of Use for Institutional Planning Add Resource Utilization? Medical Teacher, 27, 332-337.

- 26. Till, H., Roff, S., & McAleer, S. (2002). Identifying the Strengths and Weaknesses of a New Curriculum by Means of the DREEM Inventory. AMEE Poster 2002.

- 27. Vieira, J. E., Do Patrocínio, T. N. M., & Martins, M. A. (2003). Directing Student Response to Early Patient Contact by Questionnaire. Medical Education, 37, 88-89.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01431.x

Appendix.DREEM―(Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure).

NOTES

*Corresponding author.