International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.2 No.5(2011), Article ID:8780,9 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2011.25100

Urological Affections after Laparoscopic Hernia Repair in Long-Term Follow up

![]()

1Helios St. Elisabeth Klinik Oberhausen, Department of Surgery II, University of Witten/Herdecke, Oberhausen, Germany; 2Institute for Research in Operative Medicine (IFOM), University of Witten/Herdecke, Cologne, Germany; 3Helios Klinikum Wuppertal, Department of Urology, University of Witten/Herdecke, Wuppertal, Germany; 4Helios Klinikum Wuppertal, Department of Surgery II, University of Witten/Herdecke, Wuppertal, Germany.

Email: mike-ralf.langenbach@helios-kliniken.de

Received July 27th, 2011; revised September 25th, 2011; accepted October 20th, 2011.

Keywords: Inguinal Hernia, Urological Affections, Mesh, Laparoscopic Hernia Repair, Pain

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Chronic pain is a severe complication of mesh-based inguinal hernia repair. Pain upon ejaculation, testicular touch sensitivity and dysuria are apparent. Regarding the large amount of patients undergoing laparoscopic hernia repair, the problem seems quite evident. In this prospective, clinical, randomized, double-blind study we intended to investigate the biocompatibility of three different meshes and their influence on urological affections after operative procedure. Methods: 180 male patients with primary inguinal hernia undergoing TAPP were randomized for using a heavyweight (108 g/m2), double-filament PP mesh (Prolene, 10 9 15 cm, group A, n = 60), a multifilament, heavyweight variant (116 g/m2) of PP mesh (Serapren, 10 9 15 cm, group B, n = 60), or a composite mesh (polyglactin and PP) (Vypro II, 10 9 15 cm, group C, n = 60). We compared in terms of complications (seromas, recurrence rate), urological affections and life quality (SF-36 Health Survey). The follow-up period was 60 months. Results: Convalescence in group A was slower than in groups B and C: mean-term values of the visual scales for pain development were significantly (p < 0.05) higher, incapacity for work was 8.2 days longer, and urological adverse effects were stronger. The mean-term development of life quality was significantly lower in group A up to 12th week postoperatively. There were no significant differences between groups B and C. Beyond the 12th post-interventional week the differences diminished. Conclusions: Independent which kind of mesh was implanted still 5% of patients suffered from urological affections 60 month later.

1. Introduction

Management with alloplastic materials has become the standard procedure in inguinal hernia surgery [1-4]. Hernia surgery is one of the most common visceral operations and thus of great medical and economic importance. Many publications have shown that there are advantages in the early postoperative outcome and lower recurrence rate when using techniques with mesh implantation compared with mesh-free inguinal hernia repair. Therefore, inguinal hernia repair with mesh has become the standard in the last 20 years. Open surgery according to Lichtenstein was used most often initially, whereas minimally invasive techniques have been increasingly applied in the last decade [1-4]. Chronic pain is the most frequent long-term complication after inguinal hernia repair. Its perceived risk varies widely in the international literature. There are actual studies describing a higher rate of chronic pain after laparoscopic hernia repair in comparison to the open approach and there are studies describing it the other way round. Nevertheless, mesh associated chronic pain after hernia repair is an often described phenomenon [5-7].

Meshes cause rigidity, shrinking, chronic pain, adhesion formation as well as inflammatory process concerning epididimis and vas deferens [8-11]. Permanent relief of pain or discomfort and low incidence of periand postoperative complications and recurrence rates are the goals of successful hernia repair. In laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair the inguinal region is approached and hernia repair is performed from the interior side. Exploration and placement of staplers in the internal inguinal region during laparoscopic hernia repair may induce specific complications such as nerve entrapment, neuralgia, hematomas [12-14]. In laparoscopic procedures mainly polypropylene meshes are used thanks to its strength and incorporation characteristics [13,15,16]. They provoke a strong stimulus for chronic inflammatory response [16- 18]. This problem has led to the development of different meshes characterized by a reduction of the polypropylene volume, an increase of the pore size, different web structures [19,20]. Also meshes with absorbable and nonabsorbable components have been produced and used (filaments of polypropylene and polyglactin) to minimize the amount of non-absorbable foreign material. Although the complications are relatively low considering the large number of meshes being implanted, common complications are observed, including local wound complications, seromas, wound discomfort and stiffness of the abdominal wall [9,13,21-23]. The impact of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair on open radical retropubic prostatectomy is discussed and it is described that pelvic lympadenectomy could be compromised [24]. How ever, urological affections or disorders do play a leading role in the postoperative disorders like dysuria, touchsensitiveness of the testicle or pain with ejaculation [14].

The designed prospective comparative clinical trial, investigated the compatibility of three different meshes in patients undergoing TAPP for primary inguinal hernia in long-term follow-up. In every case we used the same surgical technique, inserting three different meshes with different polypropylene amount or different structure. We investigated the consequences of reducing the quantity of non-absorbable polypropylene (two pure heavyweight polypropylene meshes, or a polypropylene-polyglactin tangle) and of different structure (doubleand multifilament heavy-weight polypropylene mesh) by means of urological affections and life quality.

2. Methods

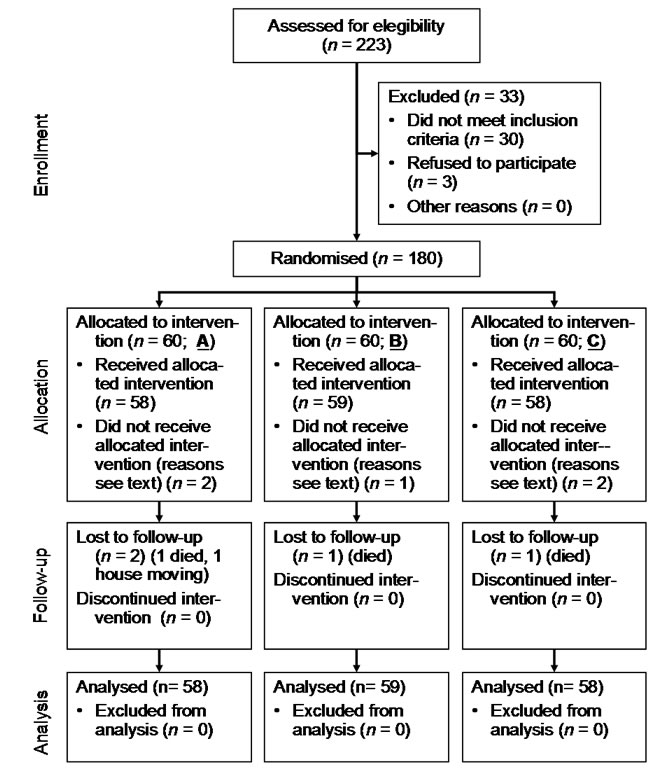

180 male patients undergoing an endoscopic hernia repair for primary inguinal hernia with mesh were included (see Figure 1).

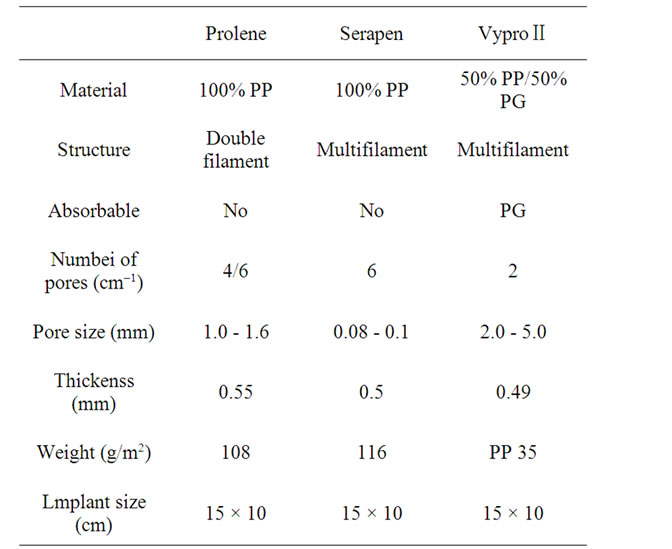

After the process of randomisation we had three groups: A: 60 (average age 61.5 years) of these were treated with a monofile, heavy-weight (108 g/m2), double-filament polypropylene mesh. B: 60 (average age 62.3 years) got a multifilament, heavy-weight variant (116 g/m2) of polypropylene mesh being composed by multifile material implanted. C: 60 patients (average age 63.2 years) were treated with a composite-mesh made of polyglactin (PG) and polypropylene (PP) (PP 35 g/m2) (see Table 1).

On the day prior to the operation a detailed physical investigation with determination of the blood routineparameters and a doppler-ultrasound investigation of the testicular vessels (arteria testicularis, plexus pampinifor-

Figure 1. Recruited patients (intention to treat).

Table 1. Mesh data used for TAPP.

mis) took place. The testicle volume and the blood circulation of the testicle were likewise documented at the 1st and 3rd postoperative day by means of ultrasound. At the 1st and 3rd postoperative day as well as after the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 8th and 12th postoperative week and the 12th, 24th and 60th postoperative month on the basis of questionnaires the pain development (visual scales), impairment of the sexual life and duration of incapacity for work were documented. The physical conditions were checked in the 4th, 8th and 12th postoperative week and the 12th, 24th and 60th postoperative month by using the German SF-36 Health Survey Test. This test is an instrument to evaluate the influence on quality of life of different forms of therapies by measuring four components: general physical conditions, social relations, psychological conditions and functional competence. Furthermore postoperative complications were documented.

2.1. Randomisation

The coincidence distribution was done with prepared envelops. The day before the operations every patient has to tear an envelope with a card inside. The name of the mesh was typed on the card. Every surgeon (two fixed teams) received a list with the name of the patient and the sort of mesh that had to be implanted. The surgeons who implanted the mesh were not included in the follow-up. Neither the patients nor the investigating doctor were informed about the type of mesh used (see Table 1).

2.2 Statistical Analysis

Based on our previous experience (Surg. Endosc. 2003; 17:1105-9), our sample size calculation aimed at detecting a difference of 10 points in the SF-36 subscale on bodily pain at the 12-week follow-up. With a power of 80%, a type I error of 5%, and a standard deviation of 18, a sample size of 52 patients per groups was required. Thus, the study recruited a total of 180 patients. Data analysis has been done on an intention to treat basis.

All results are given as mean ±SEM. Differences for parameters obtained at each point of time were evaluated by a 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures using SPSS software. At a level of p < 0.05 differences were considered significant.

The scales of SF-36 have been transformed in values of numbers between 0 and 100 to enable a comparability in each group and the different groups of patients.

2.3. Patients

In the years 1999 - 2001 180 male patients undergoing an endoscopic hernia repair (TAPP) for primary inguinal hernia and fulfilling the criteria were included into the study. After the process of randomisation 60 patients were treated with mesh A, 60 got mesh B and 60 mesh C implanted.

In every group 60 patients were allocated to intervention. In group A only 58 patients received the intervention. In two cases the Lichtenstein procedure had to be done because of massif peritoneal adhesions. Also one person in group B had an operation of Lichtenstein. In group C two patients received open hernia repair because of peritoneal adhesions, like in group A.

Inclusion criteria were: male patient, one-sided inguinal hernia, age between 35 and 75 years, BMI less than 30. The exclusion criteria were: peripheral arterial disease worse than clinical stage II b, recurrent inguinal and scrotal hernia, neurological affections or paresthesia of the genital region or the lateral region of the proximal lower extremity, polyneuropathy, disturbance of the testicular blood circulation with testicular atrophy, therapy with anticoagulative drugs, chronic back pain, intraoperative conversion to open procedures, hydrocele, epididymitis, funiculitis, femoral hernia or incarceration.

Concerning the follow-up we lost two patients in group A after two years: one died and one did house moving. In group B one patient died after one year of follow-up and in group C we lost a patient after two years.

Overall we analysed 58 patients of group A, 59 patients of group B and 58 of group C.

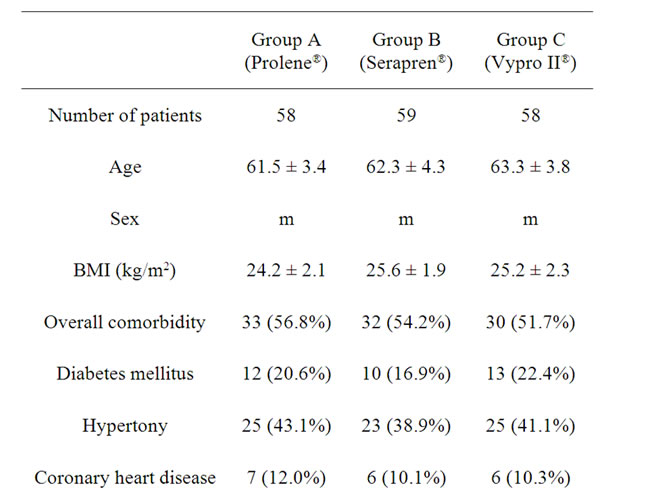

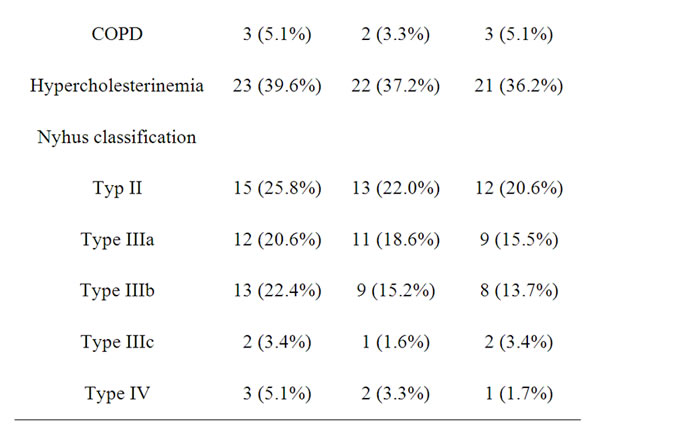

In each group we found COPD, hypercholesterinemia and lipidemia, arterial hypertony and coronary heart disease at comparable percentage (see Table 2). In the

Table 2. Presentation of the three groups undergoing TAPP.

patient group with mesh A we found in 43% a left-sided lateral hernia inguinalis, in 43% a right-sided hernia inguinalis lateralis and in 14% a right-sided hernia inguinalis medialis. In the group with mesh B there were 40% patients with a left-sided hernia inguinalis lateralis, 40% with a right-sided hernia inguinalis lateralis, 10% with a left-sided hernia inguinalis medialis and 10% with a right-sided hernia inguinalis medialis. In group C there were 35% with left-sided hernia inguinalis lateralis, 47% with right-sided hernia inguinalis medialis and 18% with right-sided hernia inguinalis lateralis. The size of the hernia was measured during the operation and the surface was calculated. In all group the surface was determined between 3 and 16 cm2.

2.4. Endoscopic Surgical Procedure

All patients were operated under general anesthesia. At the starting point the pneumoperitoneum was built up with CO2 at 15 mm Hg. A 10 mm trocar was placed within the umbilicus and two 10 mm trocars were placed laterally. The hernia was identified and the peritoneum was dissected. We regularly separated the peritoneum far upwards into the abdominal cavity from the structures of the spermatic cord. In this way we ensured that at final closure of the peritoneum the mesh could not be raised up from its position, lying flat at the inguinal region. Special attention we gave to retrovesical dissection, so that the mesh covered the entire medical compartment without any folds, since this region is predisposed towards recurrences. Depending on the randomisation either mesh A, B or C was positioned. All the meshes had the same size (15 × 10 cm). We did not cut any slits in the meshes. We tried to use a minimum number of clips (Cooper’s ligament, medial and lateral to the epigastric vessels; straight Endostapler, Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany). Any application of clips between the ductus deferens and testicular vessels (the so called “triangle of domm” with underlying external iliac vessels) and lateral to the structures of the spermatic cord and below the ileopubic tract (the so called “square of doom” with the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve) was strictly avoided. In the case of medial hernias we drew the thinned-out transversalis fascia into the abdomen and fixed it with at least two clips to the ligament of Cooper, to avoid any seroma formation. The hernial sac was always completely dissected out of the hernial canal and separated from the spermatic cord structures. The peritoneum was also closed with an absorbable suture (Ethicon, Vycryl 3/0).

The two surgeons, who carried out the operative procedure, had a training status of laparoscopic hernia repair of more than three hundred.

3. Results

The three groups were comparable in terms of group size and age structure, body mass index and comorbidities as well as the local findings (see Table 2). The overall follow-up rate was 97.2% after 60 months.

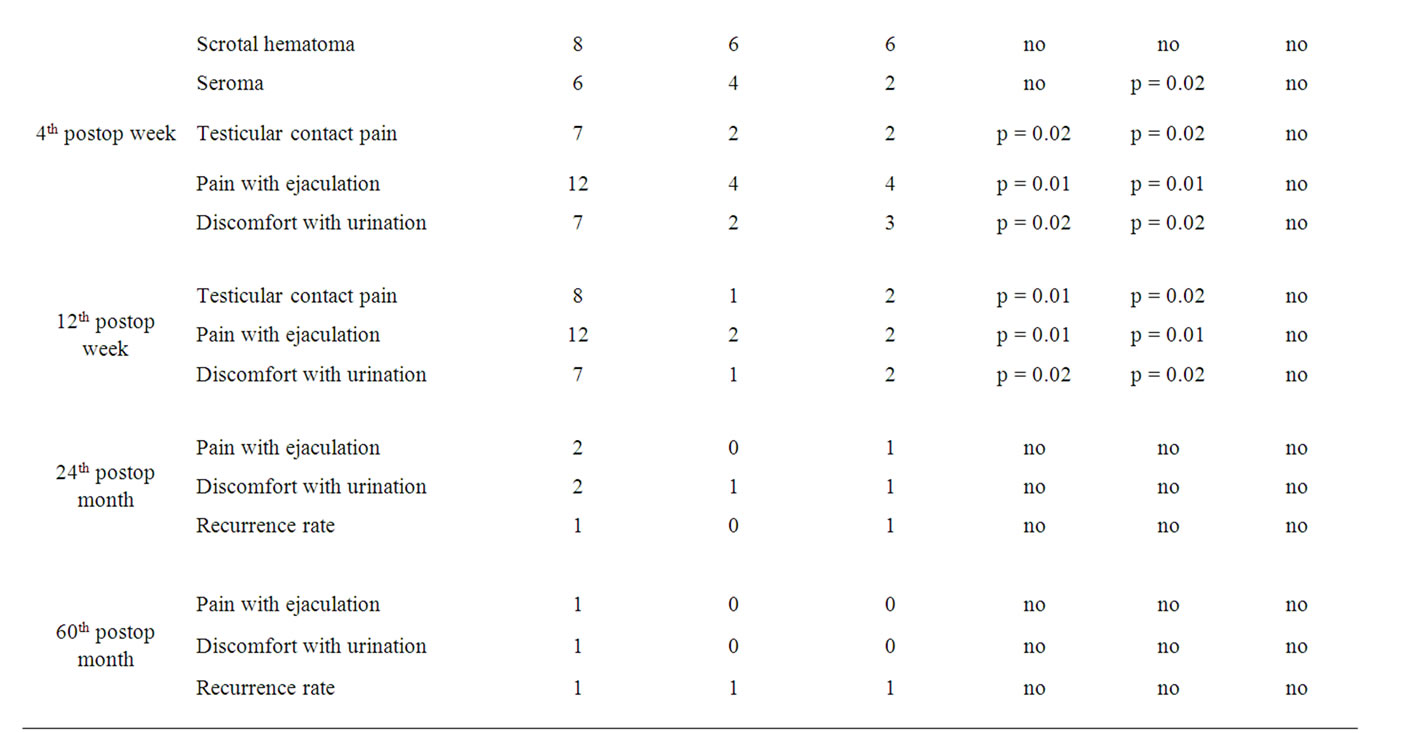

The patients spent nearly the same time in hospital (group A: 3.7 days, group B: 3.9 days, group C: 3.8 days). Average operation time was 63.9 minutes in group A, 72.6 minutes in group B and 65.3 minutes in group C. A reduction of the doppler signals in the testicular vessels at the hernia site at preoperative check was found in 8 cases. After surgical therapy the flow was improved. There were no postoperative atrophies of the testicles found. In 10 cases the pampiniform plexus was congested at the site of the hernia. This congestion was relieved in all cases after surgery. In all the groups nearly the same number of complications occurred in the form of scrotal and abdominal wall hematomas, testicular contact pain at the operated site and seroma formation on the 1st and 2nd postoperative days (see Table 3).

We had an overall recurrence rate of 2.3% (two in group A, one in group B and one in group C). In all these cases we found medial recurrences caused by partial mesh migration. There were no significant differences between the individual groups as regards the frequency of recurrence.

From the first postoperative week in all groups an increase of touch-sensitiveness of the testicle at the operated side, pain with ejaculation and discomfort with urination could be documented (see Table 3). These symptoms became significant (p < 0.05) different in the 4th and 12th postoperative week (see Table 3) in group A compared to groups B and C.

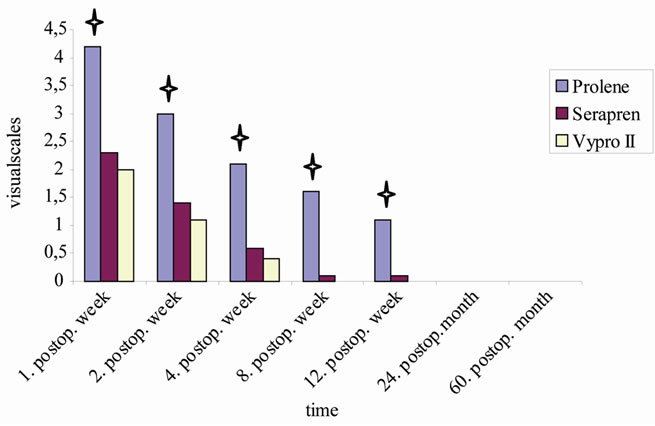

Regarding the pain development measured with visual scales one could find significant (p < 0.05) more pain from the 1st day after the operation up to the 12th postoperative week (see Figure 2) in group A.

Figure 2. Pain development after TAPP  (p < 0.05).

(p < 0.05).

postop = postoperative.

Table 3. Postoperative complications after TAPP in 180 patients (meshes A, B, C).

In the other groups there was no significant difference in pain development. Nearly the same situation could be found concerning the impairment of sexual life after TAPP through pain. The impairment of sexual life was significantly bigger in group A from the 1st week after the operation up to the 12th postoperative week compared to groups B and C (see Figure 3).

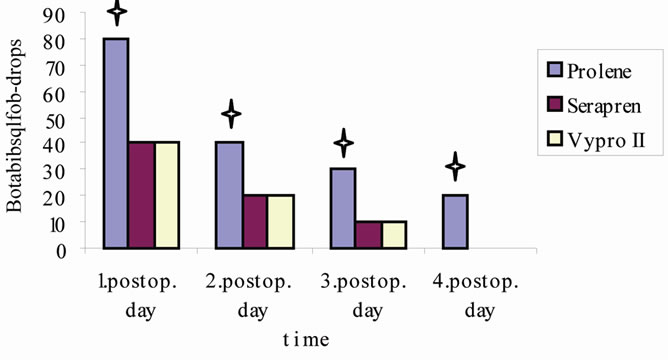

Also the therapy with analgesics (novamine-sulfon drops) reflected the presence of higher pain in group A after the operations. The consummation of the analgesic was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in group A than in groups B and C up to the 4th day after TAPP (see Figure 4).

In group A the average duration of incapacity for work was significantly (p = 0.02) longer (39.1 days) than the one registered in group B (32.4 days) and group C (33.3 days).

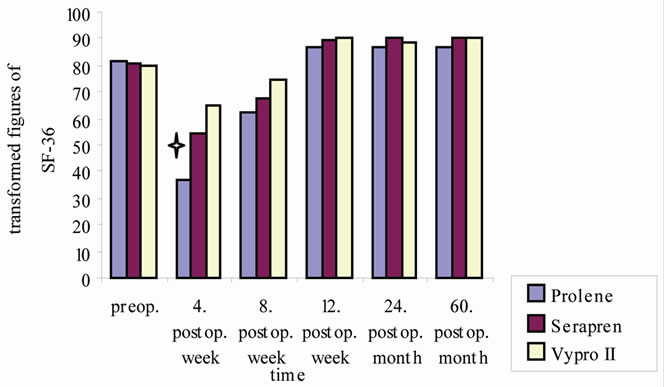

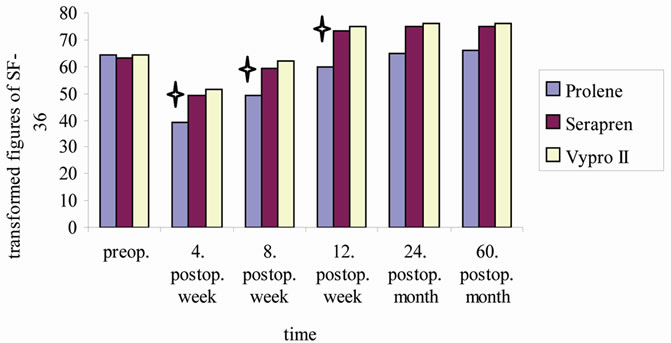

Before surgery, the generic quality of life was prospectively measured using the Medical Outcome Study SF-36 Health Survey. In Figure 5 the development of physical function from preoperative upto the 60th postoperative month is shown. At the starting point the average physical function was nearly the same in the three groups. In the 4th postoperative week it was significantly (p < 0.02) lower than in the two other groups.

Figure 6 shows the development of pain measured with the SF-36: One day before the operation pain was nearly the same in all the groups. After the operative procedure up to the 12th postoperative week a significantly stronger pain development was again described in group A than in groups B and C.

4. Discussion

Nowadays the introduction of biomaterials for inguinal hernia repair has become an integral component of surgery. Mesh implants are often regarded as a standard treatment for this anatomic defect, and their routine use in surgical practice is rapidly increasing. The high number

Figure 3. Impairment of sexual life after TAPP (p < 0.05).

(p < 0.05).

Figure 4. Analgetica consumption after TAPP  (p < 0.05).

(p < 0.05).

Figure 5. Physical function after TAPP  (p < 0.05).

(p < 0.05).

Figure 6. Development of pain (SF-36) after TAPP  (p < 0.05).

(p < 0.05).

of patients getting an inguinal hernia repair (for example 770.000 patients in 2003 in the US) makes it necessary to talk about the long-term results, especially the development of chronic pain [6]. Not only surgeons, but also many other medical specialists and generalists are confronted with this chronic problems. On the one hand surgeons should prevent causing chronic pain by using biocompatible materials and on the other hand it seems important to define a way how to handle the chronic pain symptoms Kehlet et al. describe a compromising effect on daily life for 5% - 10% of the patients. Pain-related sexual dysfunction, including dysejaculation, occurring in about 2% of young men. Sensory disturbances are described in many patients after inguinal hernia repair without chronic pain [14]. Kehlet sees the main consideration for future research on the pathogenesis and treatment of chronic postherniorrhaphy pain in the role of patient-related factors versus surgery [14]. Nienhuijs et al. draw the conclusion that 11% of patients suffer chronic pain after mesh based inguinal hernia repair. In this study more than a quarter of patients have moderate to severe pain, mostly with a neuropathic origin. Almost one third of these patients describe limitations in daily leisure activities [2,3]. Both author come to the conclusion that laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia should be done with light meshes that have a reduced amount of material.

For about a century, surgical treatment of the hernial gap was based on suture repair. Now days the introduction of biomaterials for inguinal hernia repair has become the standard. This study was designed to investigate whether life quality is influenced by properties of the implanted mesh. Corresponding to the results of previous studies comparing pure polypropylene meshes and Vypro II meshes we found no differences in the recurrence rates up to 60 months after the operative procedure [17,23].

Horstmann et al. [23] examined the impact of polypropylene amount on functional outcome and quality of life after TAPP procedure using three different meshes (Prolene, Vypro II, T-mesh) in an observational setting. He draws the conclusion that comparable functional results, lower postoperative complications, and improved quality of life can be achieved by reducing the polypropylene amount in meshes used for laparoscopic hernia repair. In our randomised trial we could not find a significant difference between the heavy-weight, smallpored, smooth, multifilament polypropylene mesh and the composite mesh in postoperative complications or life quality. In terms of incidence of discomfort, chronic groin pain and sensations of numbness after prosthetic inguinal hernia repair we could only find a significant (p < 0.05) difference concerning the pure, heavy-weight, rigid, double-filament polypropylene mesh from the 4th up to the 12th post-interventional week. Beyond this point of time there were no significant differences in our three groups. In the long-term follow up (60 month) no significant difference was documented. The difference was just significant in the shortand the mean-term follow up.

Schmidtbauer et al. showed that large pore-sized, low-weight polypropylene meshes composed of multifilaments (e.g., Vypro II), had better abdominal wall compliance and caused less chronic pain than large poresized, monofilament heavy-weight polypropylene mesh (e.g., Prolene) [25].

After all we can say, that we did not find an advantage of the composite mesh concerning the development of functional competence and the pain development after TAPP in comparison to the heavy-weight, smooth polypropylene mesh, but there was an significant advantage in pain development and functional competence from the 4th upto the 12th postoperative week in comparison to the heavy-weight, rigid polypropylene mesh. And we could also observe an advantage of the heavy-weight, smooth polypropylene mesh in comparison to the heavy-weight, rigid mesh concerning pain development and functional competence from the 4th up to the 12th post-interventional week in our trial.

Khan et al. [24] found no difference between a lightweight and a heavy-weight polypropylene mesh in patients with laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (TEP) concerning pain or discomfort at mean 3-month follow up. He described a significant inverse correlation between the length of time since operation and severity of pain or discomfort in the light-weight group, suggesting a faster speed of recovery with light-weight mesh.

It is quite interesting, that the differences seem to diminish in the long-term follow up. After 60 month we could not find any significant differences between the three groups. The process of incorporation of the materials seems to provoke different reactions reflecting in pain development, life quality and discomfort. But after the 12th week of operative therapy these differences are not evident anymore in our groups. Nevertheless, we found still 5% of patients suffering from chronic pain and discomfort in the long-term follow-up independent which mesh was implanted.

There is a need for evidence-based treatment strategies for established chronic pain. Few prospective long-term follow-ups of large cohorts suggest a burn-out rate of about 50% within 5 years. Some positive results have been reported using neurectomy. But the literature on surgical treatment of chronic pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair does not allow any firm recommendations. Pharmacological treatment of chronic pain after hernia repair has not been established, gabapentanoids and tricyclics may play a role. Local anaesthetics may prove useful concerning the relatively limited anatomical pain area [14].

In conclusion, independent which mesh was implanted still 5% of the patients are suffering from discomfort after five years. Chronic pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is an interdisciplinary global problem. Urological affections like dysejaculation, dysuria and touchsensitiveness are the most described chronic symptoms. It is still unclear which kind of mesh is ideal for the patient but it is clear that life quality is influenced by properties of the implanted mesh. Laparoscopic hernia approach with a light-weight mesh seems to provoke less chronic discomfort. Evidence-based strategies for established chronic pain are still missing.

REFERENCES

- J. E. Keller, D. Stefanidis, C. J. Dolce, D. A. Iannitti, K. W. Kercher and B. T. Heniford, “Combined Open and Laparoscopic Approach to Chronic Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair,” American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 74, No. 8, 2008, pp. 695-700.

- S. Nienhuijs, E. Staal, L. Strobbe, C. Rosman, H. Groenewoud and R. Bleichrodt, “Chronic Pain after Mesh Repair of Inguinal Hernia: A Systematic Review,” American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 194, No. 3, 2007, pp. 394-400. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.02.012

- S. W. Nienhuijs, C. Rosman, L. J. Strobbe, A. Wolff and R. P. Bleichrodt, “An Overview of the Features Influencing Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair,” International Journal of Surgery, Vol. 6, No. 4, 2008, pp. 351-356. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.02.005

- J. C. Lauscher, K. Yafaei, H. J. Buhr and J.-P.Ritz, “Laparoscopic and Open Inguinal Hernia Repair with Alloplastic Material: Do the Subjective and Objective Parameters Differ in the Long-Term Course?” Surgical Laparosc, Endosc & Perct Techniques, Vol. 18, No. 5, 2008, pp. 457-463. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e31817f4d70

- V. Thill, C. Simoens, D. Smets, C. Ngongang and P. M. da Costa, “Long-Term Results of a Non Randomized Prospective Mono-Centre Study of 1000 Laparoscopic Totally Extraperitoneal Hernia Repairs,” Acta Chirurgica Belgica, Vol. 108, No. 4, 2008, pp. 405-408.

- E. Bright, V. M. Reddy, D. Wallace, G. Garcea and A. R. Dennison, “The Incidence and Success of Treatment for Severe Chronic Groin Pain after Open, Transabdominal Preperitoneal, and Totally Extraperitoneal Hernia Repair,” World Journal of Surgery, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2010, pp. 692-696. doi:10.1007/s00268-010-0410-y

- A. Eklund, A. Montgomery, L. Bergkvist and C. Rudberg, “Chronic Pain 5 Years after Randomized Comparison of Laparoscopic and Lichtenstein Inguinal Hernia Repair,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 97, No. 4, 2010, pp. 600-608. doi:10.1002/bjs.6904

- B. J. Leibl, C. G. Schmedt, M. Ulrich, K. Kraft and R. Bittner, “Laparoscopic Hernia Repair—The Facts, but No Fashion,” Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery, Vol. 384, No. 3, 1999, pp. 302-311. doi:10.1007/s004230050208

- S. Kumar, R. G. Wilson and S. J. Nixon, “Chronic Pain after Laparoscopic and Open Mesh Repair of Groin Hernia,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 89, No. 11, 2002, pp. 1476-1479. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02260.x

- P. J. O’Dwyer, A. N. Kingsnorth, R. G. Molloy, P. K. Small, B. Lammers and G. Horeyseck, “Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing Impact of a Lightweight or Heavyweight Mesh on Chronic Pain after Inguinal Hernia Repair,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 92, No. 5, 2005, pp. 166-170. doi:10.1002/bjs.4833

- B. Klosterhalfen, U. Klinge, B. Hermanns and V. Schumpelick, “Pathology of Traditional Surgical Nets for Hernia Repair after Longterm Implantation in Humans,” Chirurg, Vol. 71, No. 1, 2000, pp. 43-51. doi:10.1007/s001040051011

- R. Bittner, K. Kraft, C. G. Schmedt, J. Schwarz and B. Leibl, “Risks and Benefits of Laparoscopic Hernioplasty (TAPP)—5 Years of Experience in 3400 Hernia Repairs,” Chirurg, Vol. 69, No. 8, 1998, pp. 854-858. doi:10.1007/s001040050500

- EU Hernia Trialists Collaboration, “Repair of Groin Hernia with Synthetic Mesh: Metaanalysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Annals of Surgery, Vol. 235, No. 3, 2002, pp. 322-332. doi:10.1097/00000658-200203000-00003

- H. Kehlet, “Chronic Pain after Groin Hernia Repair,” British Journal of Surgery, Vol. 95, No. 2, 2008, pp. 135- 136. doi:10.1002/bjs.6111

- D. Weyhe, O. Belyaev, C. Müller, K. Meurer, K. H. Bauer, G. Papapostolou and W. Uhl, “Improving Outcomes in Hernia Repair by the Use of Light Meshes—A Comparison of Different Implant Constructions Based on a Critical Appraisal of the Literature,” World Journal of Surgery, Vol. 31, No. 1, 2007, pp. 234-244. doi:10.1007/s00268-006-0123-4

- K. Junge, U. Klinge, R. Rosch, B. Klosterhalfen and V. Schumpelick, “Functional and Morphologic Properties of a Modified Mesh for Inguinal Hernia Repair,” World Journal of Surgery, Vol. 26, No. 12, 2002, pp. 1472-1480. doi:10.1007/s00268-002-6444-z

- D. Weyhe, I. Schmitz, O. Belyaev, R. Grabs, K. M. Müller, W. Uhl and V. Zumtobel, “Experimental Comparison of Monofile Light and Heavy Polypropylene Meshes: Less Weight Does Not Mean Less Biological Response,” World Journal of Surgery, Vol. 30, No. 8, 2006, pp. 1586-1589. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0601-0

- H. Scheidbach, C. Tamme and A. Tannapfel, “In Vivo Studies Comparing the Biocompatibility of Various Polypropylene Meshes and Their Handling Properties during Endoscopic Total Extraperitoneal (TEP) Patchplasty: An Experimental Study in Pigs,” Surgical Endoscopy, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2004, pp. 211-220. doi:10.1007/s00464-003-8113-1

- F. H. Greca, J. B. de Paula, M. L. Biondo-Simoes, F. D. da Costa, A. P. da Silva, S. Time and A. Mansur, “The Influence of Different Pore Size on the Biocompatibility of Two Polypropylene Meshes in the Repair of Abdominal Defects,” Hernia, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2001, pp. 59-64. doi:10.1007/s100290100001

- B. Klosterhallfen, U. Klinge, B. Hermanns and V. Schumpelick, “Pathology of Traditional Surgical Nets for Hernia Repair after Long-Term Implantation in Humans,” Chirurg, Vol. 71, 2000, pp. 43-51. doi:10.1007/s001040051011

- K. McCormack, B. L. Wake, C. Fraser, L. Vale, J. Perez and A. Grant, “Transabdominal Pre-Peritoneal (TAPP) versus Totally Extraperitoneal (TEP) Laparoscopic Techniques for Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Systematic Review,” Hernia, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005, pp. 1-7. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0309-3

- D. T. Saint-Elie and F. F. Marshall, “Impact of Lapariscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair Mesh on Open Radical Retropubic Prostatectomy,” Journal of Urology, Vol. 76, No. 5, 2010, pp. 1078-1082.

- R. Horstmann, M. Hellwig, C. Classen, S. Röttgermann and D. Palmes, “Impact of Polypropylene Amount on Functional Outcome and Quality of Life after Inguinal Hernia Repair by the TAPP Procedure Using Pure, Mixed and Titanium-Coated Meshes,” World Journal of Surgery, Vol. 30, No. 9, 2006, pp. 1742-1749. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0242-3

- L. R. Khan, S. Kumar and S. J. Nixon, “Early Results for New Lightweight Mesh in Laparoscopic Totally Extra-Peritoneal Inguinal Hernia Repair,” Hernia, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2006, pp. 303-308. doi:10.1007/s10029-006-0093-3

- T. Schmidtbauer, R. Ladurner, K. K. Hallfeldt and T. Mussack, “Heavy-Weight versus Low-Weight Polypropylene Meshes for Open Sublay Mesh Repair of Incisional Hernia,” European Journal of Medical Research, Vol. 10, 2005, pp. 247-253.