Health

Vol.5 No.12(2013), Article ID:40895,10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.512274

Pregnancy decisions of married women living with HIV during wide access to antiretroviral therapy in southern Malawi

![]()

1Kamuzu College of Nursing, University of Malawi, Blantyre, Malawi; *Corresponding Author: belindagombachika@kcn.unima.mw

2Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Copyright © 2013 Belinda Thandizo Gombachika, Johanne Sundby. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 17 September 2013; revised 19 October 2013; accepted 29 October 2013

Keywords: Contraceptives; Decisions; HIV/AIDS; Malawi; Pregnancy

ABSTRACT

Availability of antiretroviral therapy and prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV programmes have increased childbearing decisions in people living with HIV. However, pregnancy decisions of married women living with HIV have not been adequately reported in Malawi. In order to provide information to inform the development of antiretroviral and family planning services targeted to the unique needs of women living with HIV, this study explored pregnancy decisions of women living with HIV in rural southern Malawi. Twenty in-depth interviews on married women living with HIV selected purposively were conducted in two antiretroviral clinics of patrilineal Chikhwawa and matrilineal Chiradzulu districts in 2010. With their pregnancy and child rearing experiences, the women who got pregnant after a positive HIV diagnosis decided to never get pregnant again. Their lived experiences of motherhood when living with HIV play a major role in their pregnancy decisions despite free access to antiretroviral therapy, which has improved the quality of their life’s and survival. Societies in Malawi must accept this behavioural change by married women living with HIV and their needs for family planning. Health care workers must be knowledgeable and sensitive about it and assist women living with HIV who are willing to adapt their pregnant decisions based on living experiences.

1. INTRODUCTION

In Malawi just as in most other sub-Saharan African countries, a woman’s social status is directly linked to her ability to produce children. This is reflected by the high fertility rate of 5.7 children, which is compounded by low contraceptive use and high-unmet need for contraception, in a situation where the HIV prevalence rate is also high, 11% [1]. The country has an estimated 675 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, which is one of the highest maternal mortality ratios globally [1,2]. Studies in Malawi also show that HIV and AIDS related maternal deaths have increased considerably and AIDS has overtaken some of the direct obstetric causes as the lead of maternal mortality [3,4].

Previous studies in Malawi indicate that children epitomise meaning of a woman’s life. Even in the era of HIV and AIDS, a woman without children looks upon herself as incomplete, as useless [5,6]. Whether in a patrilineal or matrilineal social system, child bearing and nurturing are regarded as a woman’s prime responsibilities. In the matrilineal, marriage is followed by uxorilocal (matrilocal) residence where men leave their natal household to live in those of their wives after marriage. A woman in a matrilineal social system produces children for her own matrilineage. The children born in a marriage or even outside it belong to the mothers’ matrilineage. While in the patrilineal social system, women leave their natal household to live in their husbands’ compound after marriage (virilocal). Transfer of cattle, traditionally, legitimizes marriage, but nowadays it is money, lobola to the bride’s family. Lobola symbolically transfers a woman’s reproductive capacities from her own patrilineage to that of her husband’s [5,7-9].

The ways in which marriages are socially constructed have implications for decisions as well as the outcomes of the decisions. For instance, they give greater decision making to men and the extended family system on issues of fertility. Furthermore, differences in lineage type, matrilineal versus patrilineal, also facilitate varying sexual practices and influence women’s sexual decisionmaking [10].

Worldwide health improvements have occurred with the advent of antiretroviral therapy (ART/ARV) over the last decades resulting in dramatic reductions in HIV related morbidity and mortality and improvements in quality of life [11,12]. HIV infection may now be considered a chronic illness because the ARVs suppress HIV replication, which results in increase in CD4 cell count, delayed clinical progression of AIDS and prolonged survival [13]. Considering the potential risks of transmitting HIV to an infant and/or to uninfected partner combined with concerns about the possibility of leaving a living child after a mother’s death, one might expect women living with HIV (WLWH) to either delay or completely avoid childbearing. However, research has found that many WLWH desire to become pregnant [14]. Similarly, the number of people living with HIV (PLWH), which is inclusive of WLWH in Malawi, is increasing because of decreased mortality due to ART [15]. Similar pictures have been noted in earlier studies in developed countries of France, Brazil and the United States of America [12, 16,17].

The use of ART is also associated with increased sexual activity in WLWH, as such increasing the likelihood of pregnancies [18]. Antiretroviral therapy has played an important role in decreasing perinatal HIV transmission to less than 2%, thereby reducing the women’s concern regarding HIV transmission to their infants [19,20]. Studies from Africa suggest that HIV might modify, but does not eliminate broader desires to have children [11] and ART use may be associated with increased fertility desire among WLWH possibly though increased hopes for the future. Though longitudinal studies conducted before the wide access to ART in Malawi display a contrary picture that fertility decisions are diminished by an HIV diagnosis and rural Malawian women adjust their fertility preferences in response to an HIV positive status [21,22].

However, the pregnancy decisions of married WLWH in Malawi have received little attention. Recognizing this gap in public health, a qualitative exploratory research was conducted in two districts, matrilineal and patrilineal rural societies, in the southern part of Malawi. The purpose of the paper, which is part of a larger study on reproductive decisions of couples living with HIV, is to show the pregnancy decisions of married WLWH, in the light of available ARVs, PMTCT programmes with new technologies/procedures and in contexts where childbearing is highly valued. Two specific areas will be highlighted; the experiences of the women who did and those who did not get pregnant following a positive HIV diagnosis and their current practices to prevent pregnancy. Our study is based on the Social Ecological Model (SEM), which recognizes the intertwined relationship existing between an individual and their environment. The model recognises that whereas individuals are responsible for instituting and maintaining lifestyle changes necessary to reduce risk and improve health, individual behavior is influenced by factors at different levels [23].

2. METHODS

A qualitative approach was deemed optimal because their ability to explore an area with little existing research based knowledge, with sensitive and personal topics that could be captured fully through careful probing which lies at the core of the qualitative in-depth interview (IDI). The research questions required a greater depth of response capturing not only their married WLWH experiences about pregnancy but also the meaning attached to such experiences in rural context.

2.1. Study Setting

The informants were recruited from ART Clinics involved in the treatment and care of PLWH at two HIV and AIDS centres in southern Malawi, ChikwawaNgabu Rural Hospital and Chiradzulu-Ndunde Health Centre districts. These sites were opted for because they received patients from more remote villages, away from trading centres and main roads that attracts people whose origins is elsewhere. The two centres offer inpatient and outpatient HIV and AIDS treatment using multidisciplinary teams, and serve primarily low-income individuals from diverse backgrounds. The informants came from catchment areas surrounding these health facilities and the average time to and from their villages to the hospital ranged from one hour to three hours on foot. Both districts face challenges ranging from food insecurity, low accessibility to safe water, low household income levels and poor communication infrastructure coupled with high prevalence of HIV and AIDS [1].

2.2. Data Collection

Informants were recruited upon receipt of permission to conduct the study following ethical approval from Ethical Review Boards in Malawi and Norway. Twenty WLWH were recruited in the study using Purposive Sampling. In order to achieve maximum variation, the inclusion criteria were; married, a positive HIV-positive status, living in keeping with the traditions of their societies, had informed about each other’s HIV status as a couple and were in the reproductive age group of 18 to 49 years [1] were recruited for the study. The sample size of 20 informants was determined in keeping with Kuzel, [24] and Green & Thorogood, [25] assertions.

Data were collected from July-December 2010 in the two different districts and three months was spent in each study setting. This immersion enabled the researcher to internalize, rather than superficially observe patterns of beliefs, fears, expectations, dominant ideas, values and behaviours of the informants. The researcher gained the practical access to the ART clinics through collaboration with the ART clinic co-ordinators. In both sites, the ART clinic co-ordinators identified a contact person with whom the present study was discussed thoroughly. Considerable time was spent with the contact person to ensure that thorough comprehension was gained about the focus and the background for carrying out the study, as well as the objectives and methodological approach of the study. The contact person oriented the researcher for a period of four days on each site about the research sites. During the orientation period, the researcher was briefed about the ART clinics’ objectives, strategies in place to achieve their objectives, and the activities.

The potential informants were approached while waiting for their monthly consultations at the two study sites. The information about the research was given to the ART Clinic in two phases. First as part of the general briefing (Health talk) that all clients received in an open area before the consultations begins and secondly, as a private conversation in a private room with the contact person. In order to maintain confidentiality, those who wished further information about the study or were interested in participating in the study informed the contact person who was the last person every client met for booking their date of next appointment. Informants, who indicated willingness to take part in the study, met the researcher who asked them a few questions to determine eligibility. Those eligible were accorded an appointment (morning or afternoon). To those who were ready for the interview, oral consent was obtained, recorded on the consent form and tape recorder. Oral consent was opted for because asking them to give a written consent would have been unethical in terms of confidentiality. When the informants had consented to take part in the study, they were assured of confidentiality. The researcher informed the informants that they were free to quit if they so wished.

In-depth interviews were employed by the researcher in Chichewa (Malawi’s national local language). The decisions to have children were evoked by asking; “Can you please tell me your experiences related to decisions to get/not get pregnant following your HIV positive diagnosis?” IDIs were opted because they allow room to explore issues deeper, are interactive in nature, thereby enabling clarification of issues during the interview. In addition, they allowed further probing and modification of interview guides in the course of the study [26]. The interviews lasted between 50 minutes to 2 1/2 hours.

The IDIs were carried out at the area within the ART Clinic in offices or outside under trees where each informant felt comfortable and that their privacy would be maintained in order to promote confidentiality and a relatively relaxed atmosphere.

During the research activity, all the informants were given transport reimbursements of $2 and snacks were provided.

2.3. Data Analysis

General principles and procedures for qualitative data content analysis as summarized by Graneheim & Lundman, [27] were used. The interviews were read through several times to obtain a sense of the whole. Then the text about the experiences related to decisions to get/not get pregnant following your HIV positive diagnosis was extracted and brought together as one text, which constituted the unit of analysis. The text was divided into meaning units that were condensed. The condensed meaning units were labelled with a code. Tentative categories of the codes were discussed between the two researchers who initially did the coding independently and finally an underlying meaning of the categories was formulated into sub themes and the main theme. Examples of meaning units, condensed meaning units, codes, sub theme and theme are shown in Figure 1. All the data from digitally-recorded IDIs that were transcribed verbatim were typed. NVIVO version 9 was used to organize the data.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of Informants

Thirteen informants, five from the matrilineal and eight from the patrilineally organised marriage societies had been living with HIV for less than five years. Seven of them, five from matrilineal and two from patrilineal had been living with HIV for more than five years. All the 20 women indicated that they were in a monogamous relationship and on a family planning method. They were living in their or their husbands’ natal compounds depending on kinship organizational. Five informants, two and three from the matrilineal and patrilineal society respectively, had no formal education at all. They explained that during their childhood days, their parents only sent boys to school as girls were asked to help their mothers in household chores. Fifteen had some schooling; 13, seven from matrilineal and six from patrilineal society had completed primary education, while two, one from each society had completed secondary school education (Form 4). All of the informants were local farmers

| Meaning unit | Condensed meaning | Code | Sub theme | Theme | |

| “My immunity was low, I was sick and was not able to do household activities it was my husband who used to do them. So I was telling myself that I had not made the right decision to get pregnant while on medications (ARVs).” Patrilineal woman | I was very sick throughout the time that I was pregnant | Ill health | Women living with HIV who decided not to get pregnant | PREGNANCY DECISIONS | |

| Financial constraints | |||||

| “I was in danger and was always afraid asking myself if the child will not have AIDS or have HIV; ‘I am I not going to die with the pregnancy?’ I used to have swollen feet, was generally unwell my husband was always telling me not to worry and would take me to the hospital where I would get medicine. He also used to buy me ‘SOBO’ orange squash manufactured by Southern Bottlers of Malawi.” Matrilineal woman | |||||

| Daily psychological stress | |||||

| “I was very sick... I would have been at the grave yard by now ‘paduwa sasewera’, once beaten, twice shy, if God saw you through during your first illness, do not do it again” Matrilineal woman | I was afraid that I might be sick once I became pregnant | Fear of deteorating health | Women living with HIV who decided not to get pregnant | ||

| Fear of leaving children as orphans | |||||

| “Getting pregnant when you are HIV positive means you are testing GOD. You have survived AIDS, now that you are on free medications you decide to get pregnant, what else do you now want from God?”... Patrilineal woman | Fear of transmitting the virus | ||||

| Financial worries |

Figure 1. Coding process from meaning unit to theme.

and they were Christians.

3.2. Pregnancy Decisions of Women Living with HIV

The issue of pregnancy decisions in the married WLWH make up two different scenarios. First, we have those women who immediately decided not to get pregnant after an HIV diagnosis. Secondly, we have those women who decided to get pregnant after an HIV diagnosis but with their pregnancy and child rearing experiences, they decided never to get pregnant again. Although they are deeply intertwined, they are presented separately for analytical purposes. The informants indicated that their decision making process was long and hard and some had to quit their marriages.

“I could have been dead due to his behaviour I was married before with a certain man from Blantyre and I was staying with him at my home village but he was abusing me very much and wanted more children even though we all had the virus [HIV]. Because I was not willing to sleep with him [sexual relations], one day he got very angry, shouted at me and just left without saying bye. That was in 2005 and I have never seen him since that day. I could have been dead by now if I had accepted his decisions.” Matrilineal woman.

“... However, it reached a point where he was refusing to use condoms and he wanted to have more children, I just decided to quit the marriage in order to save my life.” Patrilineal woman.

While some had to talk the situation repeatedly with their husbands as narrated below by a matrilineal woman in her second marriage;

“We made the decision together for a permanent sterilization. But it was not easy every time I had to remind him that; ‘You wanted ‘your face’ a child, not so, now that we have one that is enough; if I die nobody is going to assist you in taking care of the child.’ So he finally accepted.”

3.2.1. Decision Not to Get Pregnant

The long dialogues with informants who never got pregnant after knowledge of their HIV-positive status indicate a complexity of fears arising from the HIV-positive diagnosis.

Fear of deteorating health

The accounts of the informants indicate continuous worries related to their own health. They were afraid that a new pregnancy might threaten their health by accelerating the progression of the disease and hastened to express that they never desired to get pregnant again. Some informants who had regained their health after a serious opportunistic infection indicated that:

“I was very sick at one point and I would have been at the grave yard by now, nobody can force me to get pregnant while I have the virus, no.” Matrilineal woman.

Some of the informants also used their belief in God’s intervention during their previous illness as a strong motivating factor on their decision not to get pregnant.

“Getting pregnant when you are HIV positive means you are testing GOD. You have survived AIDS, now that you are on free medications you decide to get pregnant, what else do you now want from God?”... Patrilineal woman.

Fear of leaving children orphans

The informants were greatly concerned for their children’s future. The worries mainly centred on the lack of care for them once they, as parents, become critically ill and eventually die. For most of these informants, planning meant consideration of guardianship, another complex and difficult issue they expressed.

Fear of transmitting the virus

Some women indicated the fear of transmitting the virus to their child made them not to get pregnant after a HIV-positive result. They all indicated that to live with HIV was already a painful experience, which was somehow bearable compared to the possibility of having a child with HIV. One informant indicated that she could not imagine “sitting with the child dying in my eyes”…

Financial worries

Almost all the informants indicated the issue of finances as a concern underpinning the decision to get pregnant while they were living with HIV. They were worried about the everyday expenditures for school fees for their child/children as well as for food and other household upkeep when their husbands, who in all cases were the main breadwinners, were living with HIV and could not make ends meet as before they were diagnosed with HIV.

“I will not have any more children, food is a problem here. I do not even desire to have any the four are enough. Taking care of the four children is a problem. We are actually struggling with these four children, going for piece work for money, for food is not easy.” Patrilineal woman.

Hence, the informants were wondering where they would get money for infant formulae, medication and for regular hospital visits when they get pregnant and have a child in context of already relatively grave poverty.

3.2.2. Lived Experience on Decisions to Get Pregnant

Some of the informants who had once been pregnant indicated that they do share their experiences with other WLWH in their various support groups as captured in the following quote;

“I tell them [PLWH] that ‘paduwa sasewera’, once beaten twice shy, if it just happened accidentally [the pregnancy] and God saw you through, do not do it again. When they say children are a gift it does not mean that they have to fill a basket, even filling a plate it is okay, so if you have one child, just hold on to that child do not have another one, provided you take good care of the child.” Matrilineal woman.

They further indicated that they inform other WLWH that if they had to do it they had to face the challenges of financial constraints, ill health and day-to-day psychological stress.

Experience of financial constraints

Although all the informants shared common financial concerns associated with caring for a child living with HIV in their day-to-day life, their experiences were diverse. For instance, informants from Chikhwawa narrated how difficult it was for them to have food and could hardly afford one full meal a day since the district is prone to droughts unlike their counterparts in Chiradzulu who though also poor, but could afford two full meals a day.

“We try working for piece work for food or money; however, with the medications we are on it is even difficult for us to work for long hours. It is even to have enough food from our gardens in this part of the country because of the excessive heat and the frequent dry spells.” Patrilineal woman.

“In fact we do not buy some of the food because we get it from our garden. Vegetables we have, pigeon peas we have, eggs we have, a hen can lay 16 eggs so we decide to have some of them and leave the rest for hatching. At least we have the food.” Matrilineal woman.

The thought of feeding options for their children was a cause of great worry because they most of the informants could neither afford baby formulae nor manage to exclusively breastfeed their babies for six months as advised by the health care workers. One informant expressed with sadness her experience with infant feeding options;

“I started weaning him at six months old and I would leave him for some time at home with his sisters and come here at Makande [Main market at Ngabu in Chikwawa] to sell some local farm produce. That is where the problem began; people started saying all sorts of things about my child’s weaning but I would lie to them that he was still breastfeeding. Occasionally his father would buy tinned milk for him. When we run out of the tinned milk; he would take porridge or whatever was available. Unfortunately, he started getting sick frequently and I was also sick, I did not have enough blood in my body [anaemic]. We were admitted here for two weeks and the child was given food supplements. Now here he is fine, with no HIV and running all over. So because of this experience, [struggling to prevent the child from getting HIV] I have decided not to have any more children, never.” Patrilineal woman.

For the three informants from the matrilineal society who had children living with HIV, the pressure of living with a child who had HIV also drained their resources in order for the child to survive, which was complicated by poverty and resulted to stress in a stressful situation.

Experience of ill health

Some women indicated their experiences of ill health during pregnancy as a deterrent to their future pregnancy decisions.

“My immunity was low, I was sick and was not able to do household activities it was my husband who used to do them. So I was telling myself that I had not made the right decision to get pregnant while on medications [ARVs].” Patrilineal woman.

“I was in danger and was always afraid asking myself if the child will not have AIDS or have HIV; ‘I am I not going to die with the pregnancy?’ I used to have swollen feet, was generally unwell but my husband was always telling me not to worry and would take me to the hospital where I would get medicine. He also used to buy me ‘SOBO’ [Orange squash manufactured by Southern Bottlers of Malawi].” Matrilineal woman.

Experience of day to day psychological stress

The long dialogues with these informants indicate a complex of severe stress arising from their considerations around another possible pregnancy, which were complicate with poverty. They were worried about their children;

“I felt so bad for the coming child, bringing it to this world infected. Thinking about it gave me sleepless nights. That is why we have decided not to have any more children.” Patrilineal woman.

Some of the informants indicated that although they may be happy that they had a child who was HIV negative, however, they were also aware of the potential emotional losses to come in the future for the child who may lose a mother, father and potentially other siblings. Therefore, this stress was enough to influence their decisions not to get pregnant again.

3.3. Prevention of Future Pregnancies

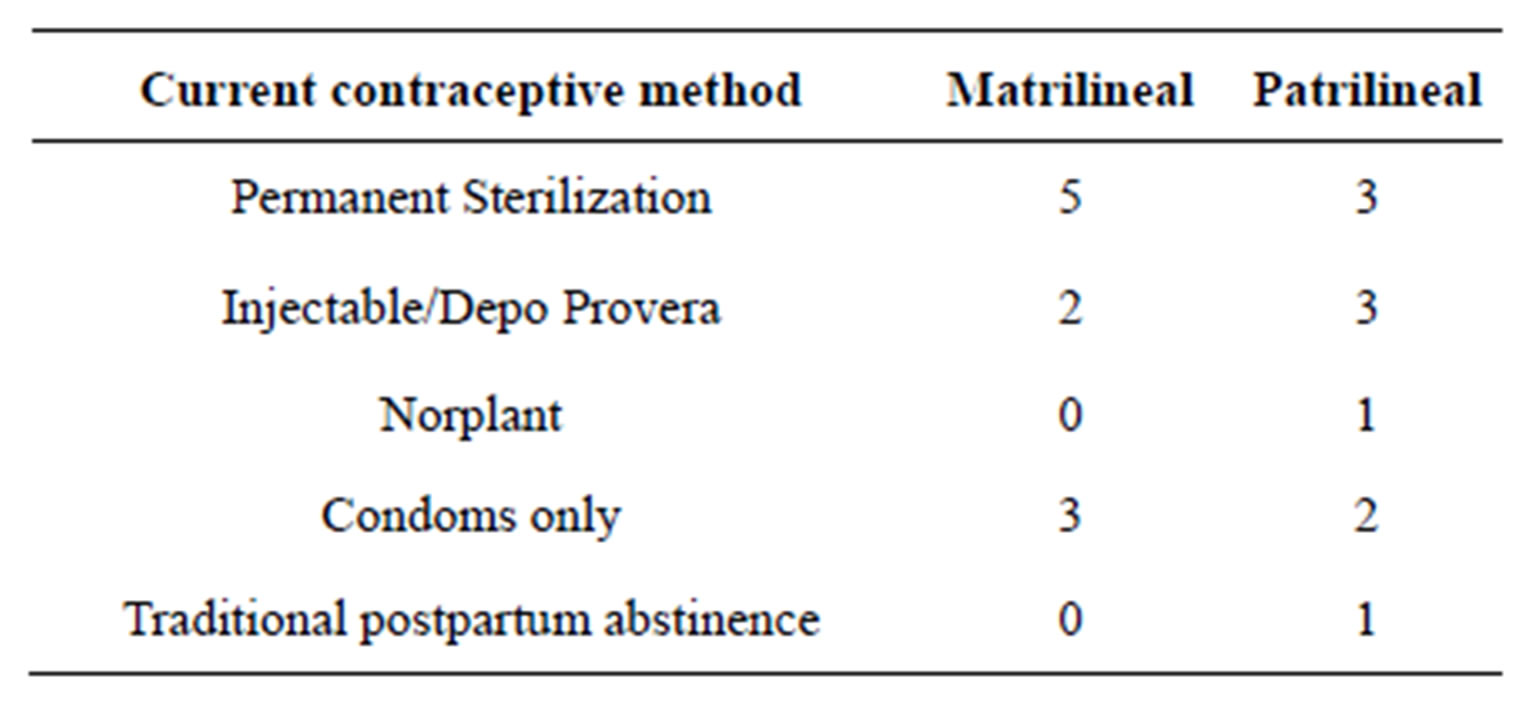

With all these experiences about pregnancy decisions following an HIV-positive diagnosis, their very strong determination to their decisions is evidenced from use of contraceptives. Their statements indicate that knowledge and actual use of contraceptives was very high. Apart from using condoms as a means of reducing the HIV viral load in their body, Table 1 shows that eight of the informants had permanent sterilization (tubal ligation), five were on injectable contraceptive (Depo Provera). One informant had a five-year Norplant, five said they were using the male condoms and one was on traditional nine months postnatal sexual abstinence, but plans to go for tubal ligation once her child is one year. When asked about the reasons for their choice of contraceptive method, they all indicated that the method were accessi-

Table 1. Information on method of contraception adopted.

ble and convenient, while for those who were using the male condoms, it was based on recommendation by the health care workers. They all indicated having discussed with their spouses about use of these methods. Unfortunately, none of their spouses offered to go for a permanent sterilization themselves.

4. DISCUSSION

The findings show that with wide access to ART, WLWH’s pregnancy decisions are diminishing because of a positive HIV diagnosis contradicting with Cooper et al., [11]; Heard et al., [16]; Peltzer, [18]; Kakaire, Osinde & Kaye, [28]; MacCarthy et al., [29], but concurring with two longitudinal studies conducted in Malawi by Hoffman et al., [21] and Taulo et al., [22]. Extrapolating that rural Malawian women, adjust their pregnancy decisions; in response to receiving information about their HIV serostatus [30].

In this study, society organization, patrilineal or matrilineal, did not influence the women’s subsequent pregnancy decisions rather their lived experiences as WLWH. Women who did not get pregnant following an HIV-positive diagnosis based their decisions on their general lived experiences as WLWH. While women who decided to get pregnant following an HIV positive diagnosis, were basing their decisions on their lived experiences of being pregnant while living with HIV. In Asia, Chi, Rasch, Hanh & Gammeltoft, [31]; Gipson & Hindin, [32]; Rabindranathan, [33], found that many women who were under pressure from both in-laws and natal kin to have a child made “their own” decisions either not to have a child or terminate a pregnancy, even in situations where their decisions went against their husband’s desire. Though our findings are similar to these, it is worthy noting that these studies have been conducted in Asia, a region with cultures that are different from sub-Saharan Africa’s, especially regarding kinship structures [34]. Despite the limitation, the study has highlighted an important area for further investigation in the sub-Saharan region. However, the findings are contrary to previous work that depicts women’s actions and decisions in childbearing as highly constrained. For example in Zimbabwe, WLWH who had a husband who had paid bride price, lobola, chose to become pregnant despite knowledge of their HIV-positive status [35].

There are a number of explanations to these WLWH change in their pregnancy decisions. On an individual level, it suggests that knowledge about the risks involved in getting pregnant and their lived experiences contributed to their decisions. The results show that even though ARV’s are available, WLWH are still concerned about their child and themselves particularly the potential risks of vertical transmission and deteorating health while pregnant and after delivery [36]. They also contemplate about the possibility of not surviving long enough to raise the children, or of giving birth to children with HIV who will require significant care. Negative messages about HIV and pregnancy [1] and an already fulfilled role of motherhood in the absence of HIV to those who already had children could have influenced their decisions [28,37]. In addition to being over burdened by the role of household care providers, which included taking care of their biological or step children, in the case of women from the patrilineal society, and sick spouses and children [12].

In terms of financial explanations, we have seen that all the women in the study were housewives in a monogamous marriage relationship with small gardens where they worked as local farmers and were without a source of their own income. Female poverty at community and at societal levels is widespread in Malawi. In general, the women encounter a burden of poverty, which makes them more vulnerable to several things than men [38]. We also concur with Bentley et al. [39], that at an individual level, knowledge and lived experience affects behaviour. The married WLWH in the study understand the effects of their financial constraints and lack of access to resources on their health and children’s particularly in light of their HIV diagnosis as such they would like to protect it. Our study therefore, supplements to this already existing knowledge but in married WLWH.

Linked with the issue of poverty was the experience of breastfeeding and replacement feeding. The experience was of substantial concern particularly by women from Chikhwawa due lack of money and inadequate food for replacement feeds. Apart from its worst health indicators, climatic and geographical features are also a contributing factor because almost every year the area is faced with dry spells and floods from a nearby big river, Shire, and some small rivers that feed into it. All these lead to a reduction in the overall agriculture production [40,41]. The complexity of the issue suggest having nationally sustainable programmes such as provision of supplementary food to all under five children born to WLWH instead of simply talking unproblematically about child feeding options “informed choices” policies.

Consistent with the Social Ecological Model [23] that individual factors influence an individual’s behaviour, the study findings indicate that knowledge and actual use of contraceptives is very high. Kaida et al., [42]; Ezeanolue, et al., [43], have also reported similar findings. In Malawi as part of routine follow up at the ART clinic, PLWH are educated about HIV transmission and prevention of unintended pregnancies [44].To some extent, the change in their pregnancy decisions may be due to the knowledge of HIV infection and transmission, which is readily available to them and their lived experiences as WLWH. Therefore, hospitals, at an organisational level, have affected the WLWH’s pregnancy decisions. Until recently, in Malawi, access to ARVs was highly limited. Policies established in the scaling up of ARVs have made the WLWH to recognize the value of the medications and more likely to focus on their health and wellbeing, thus opting for contraceptives [37]. Confirming that, health education efforts influence reproductive decision making of PLWH [45].

This new deviation from motherhood and societal expectation by the married WLWH indicates that it is extremely difficult for them to access and fully take in the complex information about contraceptive options and make a fully informed choice at once. It therefore needs to be born in mind by the health care workers that in such situations, counselling is interpreted within a highly emotional scenario with potential serious consequences resulting from misunderstandings and poor comprehension. The provision of contraceptives services at the ART clinic to prevent pregnancy is critical, but largely a neglected strategy to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and unintended pregnancy [46]. Suggesting that, health care workers must accept that these women are still sexually active. As such, they must provide integrated family planning services as part of the ART clinic routine activities. Free access of all forms of contraceptives including emergency contraceptives is available and not just focussing on ARV adherence and their side effects must be available. We further suggest that, family planning counselling and methods should be offered to both men and women systematically and regularly throughout their follow-up visits. This is in view that as they get better emotionally, it will be most likely for them to comprehend and opt for contraceptives earlier and easier. Issues of sterilization regret, a situation where WLWH make a decision to proceed with sterilization primarily because of their HIV diagnosis and later regret because of the improvement in their health [46], can be minimal if health care workers adopt the suggested approach.

The shift from relying on the traditional twelve-month postpartum abstinence evidenced from only one out of seven WLWH with children of less than one year is welcome because of the high failure rates of this method. The protective effect of the traditional postnatal abstinence is also offset by increased probability that husbands will seek extra marital sexual partners (EMSPs) without using condoms [47]. In addition, in the KassenaNankana setting, the advent of HIV and/AIDS, coupled with improved access to information on sexual and reproductive health and modern contraception, has eroded the significance of postpartum abstinence. Breastfeeding mothers are defying the sexual norm and combining innovative strategies with shorter periods of sexual abstinence to guard against HIV infection [48].

By integrating family planning services at the ART clinic, the reliance on the traditional method of postnatal abstinence will slowly change. We acknowledge and concur with earlier studies that indicate that behavioural change on a large scale tends to take time as it is preceded by a period in which unfamiliar messages become assimilated into local social networks [48]. Therefore health workers at the ART clinics should continue emphasizing the recommended postpartum sexual abstinence of six weeks as followed by Malawi Ministry of Health [49], and thereafter use of suitable and reliable methods of contraception. With time, the new behaviour will be fully adopted in these societies.

From these findings, we suggest that the Social Ecological Model and the Theory of Planned Behaviour developed by Ajzen in 1985 [50], offer plausible explanation for the observed behaviour change among married WLWH although there is need for more methodological research between these two theories and pregnancy decisions of WLWH. According to these theories, individuals are more likely to change a given behaviour if they are knowledgeable and believe that such behaviour increases their risk. Moreover, if they believe that the behaviour will form a serious threat to their health and well-being. They are also more likely to make behavioural adjustments if they believe that behaviour change will reduce susceptibility to the condition or its severity and that the perceived benefits of changing the behaviour outweigh the potential negative effects.

5. METHODOLOGICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The paper is not unanimous suggesting that the pregnancy decisions among the informants are representative of all WLWH in Malawi. First, the use of purposive sampling procedure could have resulted to selection bias. Women who self-selected to enrol in the study may differ from other women in a number of ways. For instance, they may be more disclosive, more comfortable with their HIV status or more connected to HIV related services. Secondly, all the 20 informants were sampled from two rural ART clinics in southern Malawi. Being enrolled in ART programmes gave the informants the opportunity to receive information on HIV and prevention strategies. They might have been more knowledgeable and empowered to make the decisions against future pregnancy. Thirdly, our findings pertain to a group of women who had been living with HIV for a longer period. Such women may be inclined to have negative decisions about pregnancy than newly diagnosed women. Nevertheless, we have shown that the pregnancy intention trend for WLWH is on the decline, at least in this group of women. A further close examination of these complex decisions is necessary because it will inform further those engaged in HIV and AIDS prevention and treatment efforts and sexual and reproductive health, such as health care workers and policy makers.

6. CONCLUSION

The paper offers new insights and perspectives on the experiences of married WLWH and their pregnancy decisions, which can assist in the establishment of a research agenda on priority issues regarding reproductive issues for married WLWH. Their decisions not to get pregnant again were influenced by their living experiences as either married WLWH who decided to get pregnant following a positive HIV diagnosis or married WLWH who decided not to get pregnant following a positive HIV diagnosis. The reasons include a complex mixture of factors as indicated in the SEM. The wider access of ARVs in rural Malawi has made the married WLWH to recognize the value of the medications as such to focus on their reproductive health and well-being. However, the social cultural expectations of motherhood in either their matrilineal or patrilineal societies they were coming from were not amongst the cited reasons. Their very strong determination to their decisions is evidenced from use of contraceptives. As a tool to reduce maternal mortality in WLWH in Malawi, we recommend that the ART clinic should not only focus on drug adherence and side effects, but also rather integrate their services with reproductive and sexual health services including the provision of contraceptives. They should be offered to both men and women systematically and regularly throughout their follow-up visits. Health care workers must know that; WLWH adapt their pregnant decisions based on their lived experiences and understand their urgent need for family planning services. The study findings therefore may imply that if the shifts in pregnancy decisions by married WLWH in Malawi, a country with high HIV prevalence rate, 12%, and high fertility rate, 5.7 children per reproductive age group [1] continue, it will have a very large impact on reducing the maternal and child mortality rates related to HIV and AIDS.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors express their gratitude to; the women living with HIV who shared their views and experiences. It is our hope that their contributions will bring change to their lives someday. The University of Oslo, Department of Health and Society and University of Malawi, Kamuzu College of Nursing for their support.

REFERENCES

- National Statistical Office (2010) Malawi demographic and health survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi.

- Ministry of Economic Planning and Development (2008) Millennium Development Goals Report. Lilongwe, Malawi.

- McIntyre, J. (2005) More features. Maternal health and HIV. Reproductive Health Matters, 13, 129-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(05)25184-4

- Ratsma, Y., Lungu, K., Hoffman, J. and White, A. (2005) Why more mothers die: Confidential enquiries into institutional maternal deaths in the southern region of Malawi, 2001. Malawi Medical Journal, 17, 75-80.

- Chimbiri, A.M. (2007) The condom is an “intruder” in marriage: Evidence from rural Malawi. Social Science & Medicine, 64, 1102-1115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.012

- Zulu, E. (1997) The role of men and women in decision making about reproductive issues in Malawi. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington DC, 27-29 March 1997.

- Grieser, M., Gittelsohn, J., Shankar, A.V., Koppenhaver, T., Legrand, T.K., Marindo, R., Mavhu, W.M. and Hill, K. (2001) Reproductive decision making and the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Zimbabwe. Journal of Southern African Studies, 27, 225-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057070120049949

- Kishindo, P. (1995) Family planning and the Malawian male. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 4, 26-34.

- Lawson, A. (2002) Women and AIDS in Africa: Sociocultural dimensions of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. International Social Science Journal, 51, 391-400.

- Dadoo, F. and Frost, A. (2008) Gender in African population research: The fertility/reproductive health example. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 431-452. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134552

- Cooper, D., Harries, J., Myer, L., Omer, P. and Bracken, H. (2007) Life is still going on: Reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 65, 274-283. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019

- Paiva, A., Santos, N., Junior-Franca, I., Filipe, E., Ayers, J. and Segurado, A. (2007) Desire to have children: Gender and reproductive rights of men and women living with HIV: A challenge to health care in Brazil. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21, 268-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/apc.2006.0129

- Volberding, P. and Deeks, S. (2010) Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. The Lancet, 376, 49- 62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9

- Hebling, E. and Hardy, E. (2007) Feelings related to motherhood among women living with HIV in Brazil: A qualitative study. AIDS Care, 19, 1095-1100. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120701294294

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) (2010) Global report: Report on the global AIDS epidemic, 2010. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Heard, I., Sitta, R., Lert, F. and the VESPA Study Group (2007) Reproductive choice in men and women living with HIV: Evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12- VESPA Study). AIDS, 21, S77-S82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000255089.44297.6f

- Sowell, R., Murdaugh, C., Addy, C., Moneyham, L. and Tayokoli, A. (2002) Factors influencing intent to get pregnant in HIV-infected women living in the southern USA. AIDS Care, 14, 181-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120220104695

- Peltzer, K., Chao, L. and Dana, P. (2009) Family planning among HIV positive and negative prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) clients in a resource poor setting in South Africa. AIDS and Behaviour, 13, 973- 979. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9365-5

- Chasela, C., Hudgens, M., Jamieson, D., Kayira, D., Hosseinipour, M., Kourtis, A., et al. (2010) Maternal or infant antiretroviral drugs to reduce HIV-1 transmission. The New England Journal of Medicine, 362, 2271-2281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0911486

- Kanniappan, S., Jeyapaul, M. and Kalyanwala, S. (2008) Desire for motherhood: Exploring HIV-positive women’s desire, intentions and decision making in attaining motherhood. AIDS Care, 20, 625-630. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120701660361

- Hoffman, I., Martinson, F., Powers, F., Chilongozi, D., Msiska, E., Kachipapa, E., et al. (2008) The year-long effect of HIV-positive test results on pregnancy intentions, contraceptive use and pregnancy incidence among Malawian women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47, 477-483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318165dc52

- Taulo, F., Berry, M., Tsui, A., Makanani, B., Kafulafula, G., Li, Q., et al. (2009) Fertility intentions of HIV-infected and uninfected women in Malawi: A longitudinal study. AIDS Behaviour, 13, S20-S27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9547-9

- Sallis, J. and Owen, N. (2002) Ecological models of health behaviour. In: Glanz, K., Rimer, B. and Lewis, F. Eds., Health Behaviour and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 3rd Edition, Calif, San Francisco, 462-484.

- Kuzel, A. (1992) Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree, B. and Miller, W., Eds., Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, Sage.

- Green, J. and Thorogood, N. (2006) Qualitative methods for health research. 2nd Edition, Sage, Thousand Oaks, 120.

- Morse, J. and Richards, L. (2007) Readme first for a user’s guide to qualitative methods. 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, London.

- Graneheim, U. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Kakaire, O., Osinde, M. and Kaye, D. (2010) Factors that predict fertility desires for people living with HIV infection at a support treatment centre in Kabale, Uganda. Reproductive Health, 7, 27. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-7-27

- MacCarthy, S., Rasanathan, J., Ferguson, L. and Gruskin, S. (2012) The pregnancy decisions of HIV-positive women: The state of knowledge and way forward. Reproductive Health Matters, 20, 119-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39641-9

- Yeatman, S. (2009) HIV infection and fertility preferences in rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning, 40, 261-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00210.x

- Chi, B., Rasch, V., Hanh, N. and Gammeltoft, T. (2011) Pregnancy decision-making among HIV positive women in Northern Vietnam: Reconsidering reproductive choice. Anthropology & Medicine, 18, 315-326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2011.615909

- Gipson, J. and Hindin, M. (2007) Marriage means having children and forming your family so what is the need of discussion? Communication and negotiation of childbearing preferences among Bangladeshi couples. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9, 185-198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691050601065933

- Rabindranathan, S. (2003) Women’s decision to undergo abortion. A study based on Delhi clinics. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 10, 457-473. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/097152150301000304

- Fotso, J.C., Ezeh, A. and Essendi, H. (2009) Maternal health in resource-poor urban settings: How does women’s autonomy influence the utilization of obstetric care services? Reproductive Health, 6.

- Feldman, R., Manchester, J. and Maposhere, C. (2002) Positive women: Voices and choices-zimbabwe report. International Community of Women living with HIV/ AIDS, Harare, Zimbabwe.

- Elul, B., Delvaux, T., Munyana, E., Lahuerta, M., Horowitz, D., Ndagije, F., Roberfroid, D., Mugisha, V., Nash, D. and Asiimwe A. (2009) Pregnancy desires, and contraceptive knowledge and use among prevention of mother-to-child transmission clients in Rwanda. AIDS, 23, S19-S26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000363774.91376.dc

- Maier, M., Andia, I., Emenyonu, N., Guzman, D., Kaida, A. and Pepper, L. (2009) Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live birth, among HIV positive women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behaviour, 13, 28-37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9371-7

- Rankin, S., Lindgren, T., Rankin, W. and Ngoma, J. (2005) Donkey work: Women, religion and HIV/AIDS in Malawi. Health Care for Women International, 26, 4-16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07399330590885803

- Bentley, M., Corneli, A., Piwoz, E., Moses, A., Nkhoma, J. and Tohil, B. (2005) Perceptions of the role of maternal nutrition in HIV-positive breast-feeding women in Malawi. Journal of Nutrition, 135, 945-949.

- Chunga, P., Jabu, G., Taulo, S. and Grimason, A. (2004) “Sanitary Capitaos”: Problems and challenges facing Environmental Health Officers and Environmental Health Assistants in Chikwawa, Malawi. The Magazine of the International Federation of Environmental Health, 6, 14- 24.

- Malawi Government (2010) The Malawi vulnerability Assessment committee. Ministry of Agriculture, Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Kaida, A., Gray, G., Bastos, F., Andia, I., Maier, M. and McIntyre, J. (2008) The relationship between HAART use and sexual activity among HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Brazil, South Africa and Uganda. AIDS Care, 20, 21-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120701426540

- Ezeanolue, E., Stumpf, P., Soliman, E., George, F. and Jacka, I. (2011) Contraception choices in a cohort of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Contraception, 84, 94-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.012

- Ministry of Health (2009) Guidelines for HIV testing and counseling. 3rd Edition. Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Feldman, R. and Maposhere, C. (2003) Safer sex and reproductive choice: Findings from “positive women: voices and choices” in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters, 11, 162-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(03)02284-5

- Kaida, A., Laher, F., Strathdee, S., Money, D. and Janssen, P. (2010) Contraceptive use and method preference among women in Soweto, South Africa. The influence of expanding access to HIV care and treatment services. PLos One, 5, e13868. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013868

- Cleland, J., Ali, M. and Capo-Chichi, V. (1999) Postpartum sexual abstinence in West Africa: Implications for AIDS-control and family planning programmes. AIDS, 13, 125-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002030-199901140-00017

- Achana, F., Debpurr, C., Akweongo, P. and Cleland J. (2010) Postpartum abstinence and risk of HIV among young mothers in the Kassena-Nankana district of northern Ghana. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12, 569-581. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691051003783339

- Ministry of Health (2007) Malawi National Reproductive Health Service Delivery Guidelines. Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Ajzen, I. (2011) Behavioral interventions: Design and evaluation guided by theory of planned behaviour. In: Mark, M.M., Donaldson, S.I. and Campbell, B.C., Eds., Social Psychology Program and Policy Evaluation. Guildford, New York, 74-100.