Creative Education

Vol.08 No.04(2017), Article ID:75901,9 pages

10.4236/ce.2017.84050

Sign Language Interpreters: Perception Analysis about Working with Deaf Students in a Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology in the Northern Region of Brazil

Cesar Gomes de Freitas1, Cristina Maria Delou2, Gildete da Silva Amorim3, Edilene de Melo Teixeira3, Helena Carla Castro1,3

1PGEBS, Fiocruz, RJ e Instituto Federal do Acre, IFAC, Niterói, Brazil

2CMPDI, Universidade Federal Fluminense, UFF, Niterói, Brazil

3PPBI, LABiEMol, GCM, Universidade Federal Fluminense, UFF, Niterói, Brazil

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: March 21, 2017; Accepted: April 27, 2017; Published: April 30, 2017

ABSTRACT

The interpreters of Sign Language have an essential role in the education of deaf students in all countries including Brazil. They mediate the whole teaching and learning process as they are responsible for the communication between teachers and students. Due to their important role, their performance has direct implications in the student’s academic success as well as in the process of their inclusion in the society, which begins at early age at school. In the present study we investigated the perception of Brazilian interpreters that work in a Federal Institute of education, science and technology in the northern region of Brazil. Thus we analyzed their opinion about different aspects involving their work with students with hearing disabilities in this institution. On that purpose we employed a quali-quantitative approach by using a questionnaire with structured and non-structured questions. According to the interpreters’ point of view, some actions still have to be done to achieve the effective inclusion of students with hearing impairment in the educational institution evaluated. On that matter the work of interpreters should be more recognized as important for the teaching and learning process of deaf students leading to the improvement of their work conditions for attending them. These professionals also reported the importance of teachers learning sign language for improving the psychological aspects of these students and their perception of the institution acceptance.

Keywords:

Deafness, Sign Language, LIBRAS, Special Education

1. Introduction

The hearing is an important sense with an essential role on teaching-learning process. It uses the ears as channels for receiving information from the outside world. Deafness is the partial or total loss of the hearing sense (WHO, 2017) . It can be congenital or acquired and may significantly compromise the teaching process currently based on orality worldwide (Lima, 2010) .

According to Soares and Carvalho (2012) , the first specialized school for deaf people, the Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris, was created in 1760 by Charles-Michel de l’Épée at France. In Brazil, the inclusion of people with hearing disabilities in the educational system is much more recent and characterized as a slow process (Dias et al., 2014) .

The Brazilian Guidelines and Bases Law (LDB) regulates the educational access and the specialized services to include students with disabilities and linguistics special needs such as deaf students in the current educational system. Importantly, the presence of these students in this system brought several challenges that range from the lack of specialized support services to meet their linguistic needs (e.g. interpreters), to the presence of unprepared teachers to attend in a inclusive perspective and deal with classes that present hearing and deaf people at same time (Dias et al., 2014, Flores & Rumjanek, 2015) .

The issue of deaf education in Brazil is still a problem with no easy solution. Bilingual classes or schools that deal with deaf and hearing-impaired students are rare or even non-existent in most regions of Brazil and are only accessible to a minority in this and other several countries (Dias et al., 2014) .

Based on this context it is important to consider that the success to reach an effective inclusion of deaf students does not rely only on the teachers work but also on many elements necessary to achieve it. According to Smith (2008, p. 41) : “The special education also includes a wide range of related services, which are combined to form multidisciplinary teams assigned to handle the specific needs of each student with disabilities”. On this aspect, the Sign language interpreters are very important as they are part of this educational scenario with an important role in it.

The Sign Language interpreters should pursue quality in their work to ensure the inclusion of deaf students at schools. They should be part of a multidisciplinary teaching team and engage collaboratively with teachers to guarantee for the deaf students the education access so they can have a proper understanding of the whole scholar curriculum, including complex disciplines such as science and biotechnology (Smith, 2008, Rumjanek et al., 2012, Flores & Rumjanek, 2015) .

In Brazil, since the creation of the graduation course in the area of Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) named Letras-Libras, translators and Interpreters are more recognized as part of the educational system, which strength this important linguistic area and help to ensure the deaf people language right. At same time their unsuccessful experiences have been informally reported, revealing the necessity of specialization and further continued training.

Due to the Brazilian inclusion law, the Sign Language Interpreter is even more necessary in the educational system as deaf people are now accessing it. According to Lima (2010, p. 143) “the formation and the training of people for acting in an inclusive society involves critical thinking”, thus it is comprehensive the growing demand for this professional as, with the law enforcement, the numbers of deaf students are increasing in the initial and higher educational levels. In a classroom with a mono-oral-language educational system, it is impossible to these students to advance in their studies and acquire knowledge with quality without an interpreter (Lacerda, 2010) .

However, it is important to note that the insertion of these professionals in the educational spaces needs to be previously and carefully approached. The inclusive practice observed to date revealed the lack of recognition of the richness of the deaf culture and language at these spaces and the lack of preparation as well as opportunities for discussions about this public in these institutions, which may compromise the performance of these professionals.

The challenges are plenty and include the relationship between teachers and interpreters. Trustiness between these two professionals is crucial (Lacerda, 2002) , but it only occurs after a negotiation and discussions about their role and their teaching practice to make it suitable for both of them besides the student. In order to avoid problems and guarantee the quality of the education offered to the deaf public, these students should be the main focus of these professionals, whether in public or private schools, to empowered them and meet their specific demands.

Currently the challenge of including people with disabilities is real in the Brazilian Federal Network of Professional, Scientific and Technological Education. The Brazilian network involves 38 institutes with more than 400 units that offer free courses from technical to post doctorate level (Federal Network of Professional, Scientific and Technological Education, 2013) . As they form citizens technically prepared for working on the real life, the presentation of an inclusive profile is crucial for contributing with the education of people with special needs such as deaf people.

The Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology (IFECT) of Brazilian Northern Region is one of the institutes of the Brazilian Federal Network. It started in 2010 with approximately 350 students enrolled in nine courses spread across four campuses, involving natural resources, environment, health and safety, and management and business. Currently, IFECT offers different courses from mid-level Technical Courses in high school and mid-level Technical Courses EJA (adult and youth education), among others.

IFECT reserves 5% of all entrances to people with disabilities, including deaf people. According to the IFECT data, deafness is the disability with a higher frequency among the students that occupy these vacancies.

In order to analyze the inclusive educational profile of these institutions and the interpreters participation on deaf students academic, we performed a case study, investigating and analyzing the conditions of the interpreters work thro- ugh the perspective of these professionals. This analysis aims to identify issues to be solved and/or improved, serving as a guide for other Federal Institutions.

2. Materials and Methods

This work was performed in a Federal Institute located in a State of the North region of Brazil selected due to its recent creation. This work used a quali-quantitative approach and a questionnaire with closed, open and semi-open questions (Caregnate, & Mutti, 2006) .

After approval by the Ethics and Research Committee of Institu to Oswaldo Cruz, Fiocruz, number 644,846, the survey was conducted in May and June 2015 to verify the perceptions about working with deaf students in the IFECT of eleven interpreters (n = 11), aged between 22 and 31 years and that were working at the time of the survey. Thus a questionnaire containing 10 (ten) questions was applied along with the term of free informed consent.

Due to the geographic distance between IFECT units, seven interpreters received the questionnaire delivered in person, whereas four received it by e-mail, immediately answering and returning it. The quantitative analysis was presented through graphics of simple frequency, according to the proposal of Triviños (2008). In addition a qualitative analysis was performed through issues that have emerged in the context of the open questions (Patton, 1980 apud Cohen et al., 2001 ).

3. Results and Discussion

As reported by the literature, the challenges in the educational area involving students with disabilities are still huge. Thus, it has been necessary for them to struggle to ensure their full citizenship and rights (Dias et al, 2014, Flores & Rumjanek, 2015) .

The National Special Education Policy reports the inclusion actions and movements as a worldwide phenomenon triggered in the defense of all students rights on learning together, without discrimination of any kind, including political, cultural, social, and/or educational (Brazil, 2008) . The data found in our research showed that IFECT is connected with this inclusive world perspective, confirmed by the creation of services (e.g. NAPNES) for attending individuals with special needs in all campuses. The Nucleus of Support for Students with Special Needs (NAPNES) contributes to the institution connection with these global concerns regarding inclusion as concentrate several inclusive actions to assure these students rights and accessibility.

The interpreters of IFECT are subordinated to NAPNES coordination. According to our analysis about NAPNES organization, the interpreters have a vital role on the teaching-learning process of IFECT deaf students. Mostly all teaching-learning process that involves deaf students on IFECT depend on the interpreter as no professor knows LIBRAS fluently enough to assure teaching this public. Thus the interpreters end up having a holistic view of all teaching and learning process of the deaf student and can contribute significantly to it, doing more than only interpreter disciplines (Martins, 2006) .

The analysis of conceptions/perceptions of interpreters in relation to the service offered to deaf students may assist in the understanding of the current work conditions of these professionals as well as to improve education for this audience in the IFECT.

In this paper we applied a questionnaire to 11 (eleven) interpreters that work at two IFECT campuses at the time of the survey. Four of them were from IFECT and nine were hired as temporary servers to work with the deaf students.

According to the eleven interpreters when asked if there is inclusion of deaf students at IFECT, all participants answered positively (100%). This result is consistent with the fact that IFECT had 20 (twenty) deaf students enrolled in three of its four campuses in the time of this research. It is important to notice that this answer can be evaluated as regarding mainly to the physical inclusion of the students not assuring the educational/academic inclusion of them with access to all academic/educational disciplines contents.

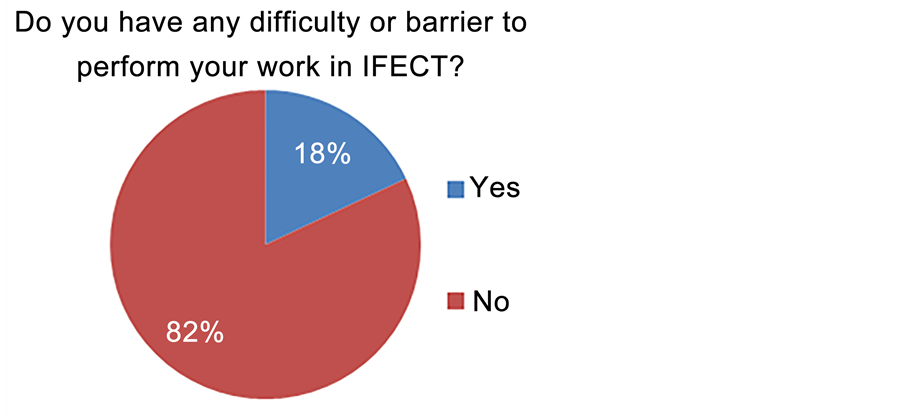

Interestingly, 82% of the interpreters answered negatively when asked about the existence of difficulties or barriers to their professional work (Figure 1).

Among the answers of the interpreters that reported difficulties, the most cited issues were regarding professors performance including lack of didactical methodology, planning, and interaction with interpreters and deaf students. Another important issue cited was the lack of specific signs to interpreter, which according to one of the interpreters: “the great difficulty is the lack of signs, as there are some disciplines that have no signs for teaching several topics”.

Three legal events were important in the history of the Brazilian deaf communities including: 1) the regulation of Law 10,436 on 24 April 2002 that recognized the Brazilian Sign Language not only as one of the official Brazilian languages but also as the first language of deaf people. 2) The Decree 5626 in 2005 that approached the deaf social inclusion, highlighting ACE guidelines of bilingual education, and 3) the Law 12,319 /2010 that recognized the interpreters as educational professionals. These laws represented significant victories compared to the history of linguistic oppression that has restricted the use of Sign Language in the last century, with schools full of clinical spaces for rehabilitation of hearing and speech.

The Decree 5626/2005 regulated the Brazilian Sign language (LIBRAS) Law with significant impacts on the recognition of bilingualism right for Brazilian deaf people. Among these impacts, we may cite 1) LIBRAS as an obligatory discipline of teacher training courses 2) the formation of LIBRAS teachers at graduation level, 3) training and hiring interpreter/translator of LIBRAS/Portuguese, 4) offering inclusive classes and schools in the educational system, and finally the Law 2015/13,146 Chapter IV, art. 28.30 about right of education.

Deaf people are currently strengthening their citizenship. However, as a minority class, the conquer of these spaces at the so called “inclusive” context of the 21st century is not easy. Thus, there is still a long road to be pursued to achieve their full constitutional rights.

At the linguistic perspective, the absence of signs for teaching complex disciplines forces the interpreters to: 1) use the manual alphabet to replace the unknown signal or 2) encode temporarily new signals with and/or in agreement to the deaf people and used it as “official” in that particular situation. Despite this strategy has been of great value, it leads to learning with different signs at different places without sign consistency. Thus this situation regarding scarcity of signs reinforces the need for studies and researches regarding the production of sign language glossaries and scientific dictionaries.

In relation to teachers and classroom methodologies, if they meet the expectations and needs of deaf students, 63% of the responses were negative whereas only 18% were positive. Two of the participants answered that it depends on the teacher, since some are more sensitive to deaf students (not shown). In this question, the biggest complaint of the interpreters was, despite the image importance on deaf student comprehension, the lack of images in the presentation strategies used by these teachers in their classes is huge. Campello (2008) in her doctoral thesis presented the visual pedagogy that can be understood as the education stood on visual strategies. Therefore the teachers that extensively use visual material as their greatest ally on the teaching process are the most successful professionals on teaching deaf students. Thus, the widely use of images by the teachers in the classroom would be an excellent strategy for improving the academic development of the IFECT deaf students.

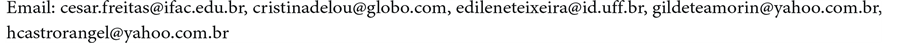

From the eleven interpreters evaluated, 73% answered negatively when asked if they consider teachers properly trained to teach deaf students. Two participants reported once more that it depends on the teacher (Figure 2). According to the interpreters, in order to improve the teaching and learning process of deaf students, for example teachers could receive practical guidance on strategies to be used with this public, with the increase of visual materials, approaches and strategies.

The Brazilian Law No. 13,146 , 6 July 2015, in chapter IV discusses the right to education of people with disabilities. Among several topics, the article 28 regulates the obligation of the Government to “ensure, create, develop, implement,

Figure 1. Answers of interpreters about the existence of barriers or difficulties in carrying out their work with deaf students of IFECT.

Figure 2. Answers of the interpreters about the proper training of teachers to teach the deaf students of IFECT.

promote, monitor and evaluate” several actions to ensure this right. The item X brings the need for “pedagogical inclusive practices for teachers training and offer continuing training for specialized educational service”, which reinforced the view of interpreters about offering a continued training for these professionals in the search for a more in-depth knowledge regarding this specialized area.

About the material and support offered by the Institution to perform a good professional work, 82% of the interpreters responded positively. In this topic, we detected a problem in one campus as all negative answers were from the same campus. The dissatisfaction involved the lack of equipment and specific materials not offered to deaf students. However, despite this dissatisfaction, when asked to evaluate the work performed by NAPNE, 90% of participants considered suitable the work carried out by this nucleus.

When asked about what was missing for IFECT be an inclusive Institution, 55% of participants of the survey cited the lack of training of staff and teachers. Some commented about the lack of basic knowledge of LIBRAS among the staff and teachers that would be essential and helpful with deaf students. Even those who considered IFECT as an inclusive institution pointed out the need to fix some issues such as the improvement of the communication and the need for basic courses of LIBRAS to servers, staff and teachers. One of the interpreters stated that “we need to break some attitudinal barriers”.

Most answers pointed out that IFECT is on the right path in relation to the permanence of deaf students. One of the interpreters commented: “I have had cases of students dropout. I think they need more incentive to study from the family, the institution and teachers”. The testimony of another interpreter were similar: “years ago it didn’t have such permanence of deaf due to the absence of interpreters, but now, the deaf have linguistic support to stay.

In the space offered for making suggestions or comments on topics not approached in the questionnaire, some interest observations were pointed out: “The Federal Institute is still growing in the perspective of inclusion, but in the short time that I'm at service as interpreter, there have been great development and I believe that it will improve continuously”. Another interpreter commented: “I wish that all in the Federal Institute search for the understanding about inclusion, so that they can change their attitudes and teaching methodologies. I also whish that this public get into the Federal Institute and feel the difference from other institutions. Because inclusion is not just a detail here or there, but as a whole, from the entrance door to the classroom. We have to understand that we are all at risk of being disabled someday, thus we have to modify ourselves and then complement the others”.

4. Conclusions

In the present work we analyzed the perception of all IFECT interpreters in relation to their service with deaf students, professors performance and institution conditions. It is important to reinforce the limitations of this study due to the small number of interpreters evaluated, but at same time we should recognize the role of this work on stimulating more researches involving this important professional class, the sign language interpreters and the creation and/or organization of scientific signs including glossaries and dictionaries.

The current analysis pointed how important is the preparation of teachers to receive and meet these deaf students needs. At several times this research revealed the importance of planning and organizing the teaching methods to properly teach deaf students.

A very important point based on the perception of interpreters was the need for teachers to obtain the basic skills of Brazilian Sign Language to improve the teacher/student communication. In addition, they should be better trained to attend deaf students, needing greater investment in continued training and qualification as well as to the interpreters that need to learn more signs to work.

However, despite the identification of issues to be solved, the opinion of interpreters was positive as a whole as they reported that IFECT is following the right path to achieve the inclusion of this public. Clearly, the union of all professional efforts with their experiences with deaf people in the educational environment, including the sign language interpreters, may improve the teaching quality on attending this public.

The work with students with disabilities is neither simple nor easy. It requires knowledge, commitment and dedication and in the case of deaf students, all the institutional support, materials and methods are essential to guarantee the good work of interpreters. Thus, new researches involving not only interpreters but also teachers and deaf students are in need for a more detailed analysis and to improve teaching this audience. These data can be important to guide future academic and administrative actions not only on IFECT but also on the Brazilian Federal Network of Professional Education and other IFECT-like institutions worldwide.

Cite this paper

de Freitas, C. G., Delou, C. M., Amorim, G. S., Teixeira, E. M., & Castro, H. C. (2017). Sign Language Interpreters: Perception Analysis about Working with Deaf Students in a Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology in the Northern Region of Brazil. Creative Education, 8, 657-665. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.84050

References

- 1. Brazil (2008). National Policy on Special Education in the Perspective of Inclusive Education. Brasília: MEC/SEESP.

http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/politica.pdf [Paper reference 1] - 2. Brazil Law No. 10,436, of 24 April 2002 (2002). It Disposes on the Brazilian Sign Language and Gives Other Provisions.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2002/L10436.htm [Paper reference 1] - 3. Brazil Law No. 12,319, of 1 September 2010 (2010). Regulating the Profession of Translator and Interpreter of the Brazilian Sign Language. LIBRAS.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2007-2010/2010/Lei/L12319.htm [Paper reference 1] - 4. Brazil Law No. 13,146, of 6 July 2015 (2015). Institutes the Brazilian Law on the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (Statute of Persons with Disabilities). Brasília.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2015/Lei/L13146.htm [Paper reference 1] - 5. Campello, A. R. (2008). Visual Pedagogy in the Education of the Deaf and Dumb (166 p.). Thesis, Florianópolis: Federal University of Santa Catarina.

http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/download/texto/cp070893.pdf [Paper reference 4] - 6. Caregnate, R. C. A., & Mutti, R. (2006). Qualitative Research: Discourse Analysis versus Content Analysis. Text & Context—Nursing, 15, 679-684. [Paper reference 3]

- 7. Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2001). Research Methods in Education (5th ed.). Oxford: Routledge Falmer Publisher. [Paper reference null]

- 8. Dias, L., Mariani, R., Delou, C. M., Winagraski, E., Carvalho, H. S., & Castro, H. C. (2014). Deafness and the Educational Rights: A Brief Review through a Brazilian Perspective. Creative Education, 5, 491-500.

https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.57058 [Paper reference 1] - 9. Federal Network of Professional, Scientific and Technological Education (2013). History of the Federal Network of Vocational, Scientific and Technological Education. Brasília: MEC.

http://www.redefederal.mec.gov.br [Paper reference 3] - 10. Flores, A. C. F., & Rumjanek, V. M. (2015). Teaching Science to Elementary School Deaf Children in Brazil. Creative Education, 6, 2127-2135.

https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2015.620216 [Paper reference 1] - 11. Lacerda, C. B. F. (2002). The Sign Language Educational Interpreter in Elementary School: Reflecting on Limits and Possibilities. In: A. C. B. Lodi, S. R. de Campos, & O. Teske (Eds.), Literature and Minorities/Organizers. Porto Alegre: Mediation. [Paper reference 1]

- 12. Lacerda, C. B. F. (2010). Translators and Interpreters of Brazilian Sign Language: Training and Acting in Inclusive Educational Spaces. Cadernos Educacionais, 36, 133-153. [Paper reference 1]

- 13. Lima, P. A. (2010). Inclusive Education: Inquiries and Actions in the Areas of Education and Health. São Paulo: Avercamp. [Paper reference 2]

- 14. Martins, V. R. de O. (2006). Implications and Achievements of the Performance of Sign Language Interpreters in Higher Education. Thematic Education Digital, 7, 158-167. [Paper reference 1]

- 15. Rumjanek, V. M., Barral, J., Schiaffino, R. S., Almeida, D., & Pinto-Silva, F. E. (2012). Teaching Science to the Deaf—A Brazilian Experience. In INTED Proceedings (pp. 361-366). [Paper reference 1]

- 16. Smith, D. D. (2008). Introduction to Special Education: Teaching in Times of Inclusion (5th ed.). Porto Alegre: Artmed. [Paper reference 1]

- 17. Soares, M. A. L., & Carvalho, M. de F. (2012). The Teacher and the Student with a Disability. São Paulo: Cortez. [Paper reference 1]

- 18. World Health Organization (2017). Deafness and Hearing Loss.

http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/politica.pdf [Paper reference 2]